Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the pathogen of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), is currently spreading around the world. The WHO declared on January 31 that the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 was a public health emergency. SARS-Cov-2 is a member of highly pathogenic coronavirus group that also consists of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Although respiratory tract lesions were regarded as main manifestation of SARS-Cov-2 infection, gastrointestinal lesions were also reported. Similarly, patients with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV were also observed. Common gastrointestinal symptoms of patients mainly included diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Gastrointestinal lesions could be used as basis for early diagnosis of patients, and at the same time, controlling gastrointestinal lesions better facilitated to cut off the route of fecal-oral transmission. Hence, this review summarizes the characteristics and mechanism of gastrointestinal lesions caused by three highly pathogenic human coronavirus infections including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, as well as SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, it is expected to gain experience from gastrointestinal lesions caused by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections in order to be able to better relieve SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Targetin gut microbiota to regulate the process of SARS-CoV-2 infection should be a concern. Especially, the application of nanotechnology may provide help for further controlling COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Gastrointestinal lesions, Gut microbiota, MERS, SARS, SARS-CoV-2

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Gastrointestinal lesions are caused by three coronaviruses, especially SARS-CoV-2.

-

•

The mechanism is similar by which three coronaviruses cause gastrointestinal lesions.

-

•

Experience could be applicated to relieve gastrointestinal symptoms in COVID-19 patients.

-

•

Gut microbiota and nanotechnology facilitate to end the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic.

1. Introduction

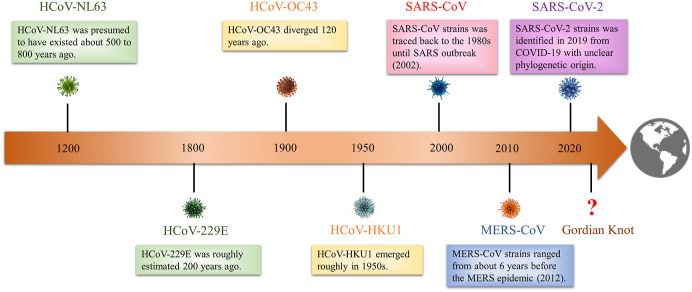

Coronavirus (CoV), with the largest genome of all known RNA viruses, is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus (Weiss and Navas-Martin, 2005). The term “coronavirus” is derived from the appearance of virus particles observed under electron microscopy. The sharp projections on viral membrane resemble king's crown (Masters, 2006). About 50 years ago, CoVs in infected animals began to attract attention. On the one hand, several CoVs caused respiratory disease in animals such as dogs and chickens (Erles et al., 2003; Cavanagh, 2007; Biswas et al., 2016). On the other hand, human CoVs have begun to form pandemics many times around the world (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The timeline of coronaviruses outbreak in human history. In human history, coronaviruses have formed seven major outbreaks worldwide. In terms of time, coronaviruses outbreak cycle is showing a shortening trend. The threat of coronavirus to humans needs to be relocated, and enough vigilance and attention should be given. This epidemic of SARS-CoV-2 has given us enough implications.

Currently, various CoVs have been identified. In generally, they are divided into four genera according to phylogeny: alpha-CoV, beta-CoV, gamma-CoV and delta-CoV. Of particular concern is that alpha-CoV and beta-CoV are known to infect only mammals. Seven strains belonging to the alpha-CoV and beta-CoV usually cause respiratory and digestive illness in humans (Kin et al., 2015). The four strains (HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HKU1) trigger only mild upper respiratory diseases in immunocompromised hosts (Forni et al., 2017). The other three highly pathogenic viruses, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), induce respiratory and digestive diseases, and may lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ failure (MOF), and even death in severe cases (Peiris et al., 2003a; Hui et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). The specific results are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

| Classification | Original location | Epidemiology | Clinical symptoms | Incubation period | Total cases (global) | Total death (global) | Mortality | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Beta-CoV | Wuhan, China | 2019–2020 in China Globally thereafter |

Fever, dry cough, dyspnea, myalgia, headache, diarrhea | 3–6 days | 18.4 million | 697 thousand | 3.8% | 31986264 |

| SARS-CoV | Beta-CoV | Guangdong, China | 2002–2003 in China Globally thereafter |

Fever, dry cough, dyspnea, myalgia, headache, diarrhea, malaise, respiratory distress | 2–11 days | 8096 | 774 | 9.6% | 12734147 |

| MERS-CoV | Beta-CoV | Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | 2012 in Middle East 2015 in South Korea |

Fever, cough, chills, sore throat, arthralgia, dyspnea, pneumonia, myalgia, diarrhea, vomiting | 2–13 days | 2519 | 866 | 34.3% | 26049252 |

MERS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; SARS-CoV, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.

Although respiratory symptoms are caused usually by CoVs, gastrointestinal symptoms are also reported. Common gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain during course of the disease. In SARS patients, patients may be more prone to diarrhea symptoms during the first week of disease (Lee et al., 2003). In addition, gastrointestinal symptoms are also likely to occur in MERS patients (Arabi et al., 2014). Meanwhile, gastrointestinal symptoms of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection seem to be more concerned. In the first patient in USA, the symptoms of nausea and vomiting (NV) appeared, and then diarrhea and abdominal discomfort also appeared (Holshue et al., 2020). NV are multifactorial and are regulated by the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ). Through vagus nerve, emetogenic chemicals in gut or cerebrospinal fluid can stimulate CTZ and activate vomiting center (VC) (Anastasi and Capili, 2011; Törnblom and Abrahamsson, 2016). Also, some COVID-19 patients exhibited impaired brain function, such as anosmia and dysgeusia. Furthermore, Moriguchi et al. (2020) confirmed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the COVID-19 patients’ cerebrospinal fluid. Hence, presumably SARS-CoV-2 can infect brain, destroying CTZ and disrupting VC. Intestinal irritation can also induce NV through the gut-brain axis. Moreover, previous studies reported that CoV RNAs were detected in anal/rectal swabs and stool specimens from infected patients (Shi et al., 2005; Kipkorir et al., 2020). It can be speculated that gastrointestinal tract may be another target of CoV attacks after respiratory tract, and it may also become a large hiding place for viruses. Therefore, this review aims to elucidate the characteristics and mechanism of gastrointestinal lesions caused by SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, and to explore new approaches for prevention and control, as well as treatment of COVID-19.

2. Overview of coronaviruses

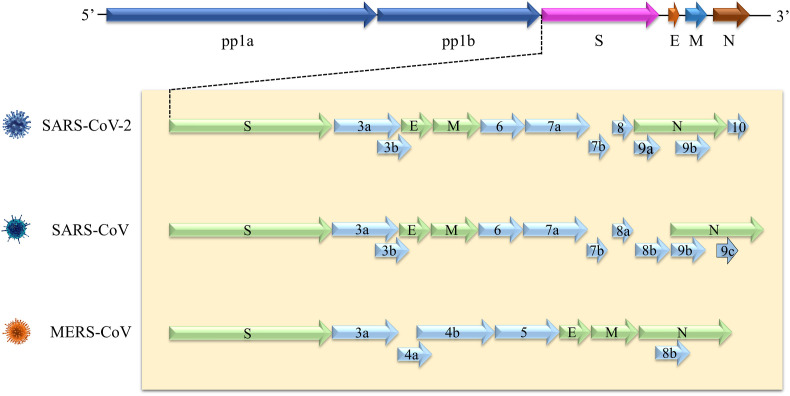

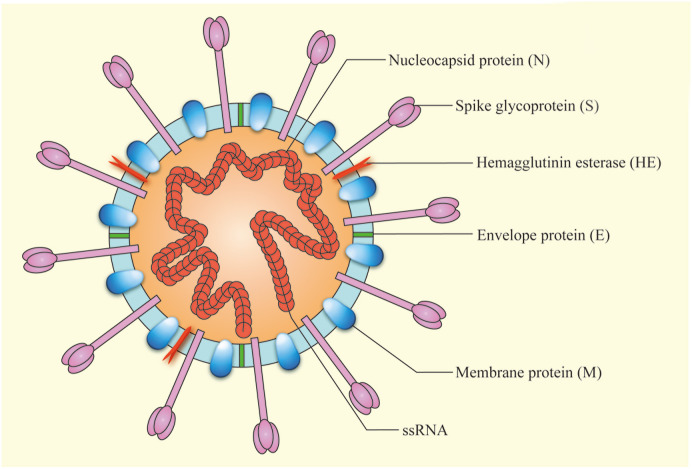

The three highly pathogenic CoVs have similar genome structures (Fig. 2 ). Approximately two thirds of genome are occupied by two overlapping open reading frames (ORF1a and ORF1b), that could be translated into pp1a and pp1b polyproteins. Meanwhile, structural proteins (including spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid) are encoded by ORFs (Marra et al., 2003). Morphologically, the virion is mostly round, with a diameter of about 80–120 nm. Cell membrane is composed of at least three proteins, including spike glycoprotein, membrane protein, and envelope protein. Some CoVs also have hemagglutinin esterase (Suzuki et al., 2020). The virion contains a helical capsid formed by combining genome RNA and basic nucleocapsid protein (Fig. 3 ) (Bond et al., 1979). The particularity of structure is key to its ability to bind to host cell receptors and enter cell (Tortorici et al., 2019).

Fig. 2.

5′ and 3′ terminal sequences of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV genomes. At the genomic level, the three coronaviruses have homology. SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV have 82% structural similarity, however, it is 50% between SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. This suggests that experience can be gained from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV outbreaks, which is very meaningful for better control of SARS-CoV-2 epidemic.

Fig. 3.

The Schematic diagram of coronavirus virion structure. The virion is mostly round. The cell membrane is composed of several proteins, including spike (S) glycoprotein, the membrane (M) protein, envelope protein (E), and hemagglutinin esterase (HE). The genetic information is wrapped in the center.

Human CoVs are zoonotic pathogens. About 70% of emerging pathogens that infect humans originate from animals. Most of them are deposited in animals and directly transmitted to humans. Specifically, almost all CoVs are thought to use bats as natural reservoir (Chan et al., 2013). Meanwhile, most of these highly pathogenic CoVs belong to RNA viruses characterized by higher mutation rates (Sola et al., 2015). These explain that CoVs could co-evolve with animal and human hosts, which may be reason why CoVs can break out in humans many times.

At present, SARS-CoV-2 infection has formed a pandemic worldwide. Recently, in term of phylogeny, clinical features and pathogenicity, SARS-CoV-2 showed partial similarities with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Table 2 ). In genome structures, it has been widely elucidated that they have high homology, especially between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, suggesting that both two might have similar pathogenesis. The mean reproductive number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to be 2.71, which is higher than SARS (1.7–1.9) and MERS (<1), indicating that SARS-CoV-2 has a stronger ability to spread (Rahman et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020b). This undoubtedly brings a huge test to global prevention and control of SARS-CoV-2. However, fortunately, the fatality rate of SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to be 3.8%, lower than SARS (9.6%) and MERS (34.3%) (Table 1). It has been confirmed that individuals with SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 may present obvious gastrointestinal lesions. Considering the similarities of the three coronaviruses, presumably measures against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV could be used to control SARS-CoV-2, facilitating God to uncover Gordian knot and to close gate of epidemic.

Table 2.

Phylogenetic, pathogenetic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

| Phylogenetic origin | Genome sequence homology to SARS-CoV-2 | Animal reservoir | Intermediate host | Receptor | Disease | Route of transmission | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Clade I, cluster IIa | – | Bats | Pangolin? | ACE2 | COVID-19 | Droplets, Contact | 32075786 |

| SARS-CoV | Clade I, cluster IIb | 82% | Bats | Palm civets | ACE2 | SARS | Droplets, Contact | 12711465 |

| MERS-CoV | Clade II | 50% | Bats | Camels | DPP4 | MERS | Contact | 29680581 |

COVID-19, 2019 novel coronavirus disease; ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; DPP4, Dipeptidyl peptidase 4; MERS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome; MERS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; SARS-CoV, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.

3. Coronaviruses and gastrointestinal lesions

3.1. SARS-CoV and gastrointestinal lesions

SARS-CoV first broke out in China in November 2002, and soon spread throughout the world (Rota et al., 2003). According to WHO, SARS-CoV eventually infected 8096 individuals, of which 774 died, with case fatality ratio of 9.6% (WHO, 2003). SARS-CoV naturally resides in bats and infects humans through intermediate hosts, such as civets (He et al., 2004). Patients infected with SARS-CoV are characterized by lower respiratory tract disease, and may be accompanied by fever, headache and other symptoms (Peiris et al., 2003b). Gastrointestinal symptoms have also been observed in patients with SARS-CoV infections. In a retrospective analysis involving 138 SARS patients, 38.4% of patients developed diarrhea symptoms (Leung et al., 2003). By using monoclonal antibodies and probes specific for SARS-CoV, Ding et al. (2004) found that in addition to lungs and trachea, SARS-CoV also existed in stomach and small intestine. Electron microscopic observation also revealed that SARS-CoV particles were present in intestinal mucosa epithelial cells (Shi et al., 2005). This suggested that gastrointestinal tract may also be target of SARS-CoV attack. This also indicated that SARS-CoV can be transited through feces. Therefore, gastrointestinal symptoms may be common presenting symptom of SARS patients, which is of great significance to control viral transmission.

Using SARS-like pseudotyped lentiviruses, Simmons et al. (2004) confirmed that spike glycoproteins were a key structure for SARS-CoV to mediate infection of their target cells. A further research in mouse models revealed that spike glycoproteins could recognize the cell surface receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (Kuba et al., 2005). It was worth noting that in addition to lungs, high expression of ACE2 was detected in gastrointestinal tract, suggesting gastrointestinal tract was a potential target for SARS-CoV (Hamming et al., 2004). After recognizing ACE2, SARS-CoV interacted with transmembrane protease serine type 2 (TMPRSS2) to activate spike glycoproteins (Shulla et al., 2011). TMPRSS2, a member of type II transmembrane serine protease family, mediated the entry of SARS-CoV into targeted cells via facilitating virus-cell membrane fusion (Iwata-Yoshikawa et al., 2019). It can be concluded that spike/ACE2/TMPRSS2 was a key part of virus invading cells and spreading. In addition, spike glycoproteins can also bind dendritic cell specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN). DC-SIGN was a C-type (calcium dependent) lectin highly expressed on dendritic cells (DCs), which can enhance virus invasion and promote virus dissemination (Yang et al., 2004; Gramberg et al., 2005). DC-SIGN was highly expressed in gastrointestinal tract (Geijtenbeek et al., 2000; Koning et al., 2015). Therefore, SARS-CoV can bind DCs, thereby promoting transfer of virus to susceptible cells. These further proved that SARS-CoV can directly attack gastrointestinal tissue and trigger gastrointestinal tract lesions.

Invading pathogens can activate cellular and humoral responses. Immune responses could lead to production of cytokines and chemokines, which in turn trigger inflammatory responses that attack pro-inflammatory cells (Perlman and Dandekar, 2005). The expression levels of cytokines and chemokines were abnormally expressed in serum of SARS-CoV-infected patients. Several studies have found that inflammatory cytokines (Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6 and IL-12), chemokines (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10)) were significantly elevated (Wong et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004). The abnormal expression of these cytokines may explain inflammation and lesions of gastrointestinal tissues in SARS-CoV-infected patients. Furthermore, ACE2 was considered as a regulator of intestinal amino acid homeostasis and expression of antimicrobial peptides. It played a key role in intestinal inflammation (Hashimoto et al., 2012). Hence, in addition to directly invading targeted cells, SARS-CoV can also cause abnormalities in body's immune system, further aggravating gastrointestinal tract lesions.

3.2. MERS-CoV and gastrointestinal lesions

MERS-CoV is a zoonotic pathogen that was first isolated in Saudi Arabia (2012) (Zaki et al., 2012). As of Jan 2020, MERS-CoV eventually caused 2519 confirmed cases, including 866 deaths, with case fatality ratio of 34.3% (WHO, 2020a). The source of MERS-CoV received widespread attention. The natural reservoir of MERS-CoV was proved to be also bats (Lau et al., 2018). Yet, intermediate host was unclear. MERS-CoV strains isolated from humans were found to be highly consistent with those isolated from camels, suggesting MERS-CoV was most likely transmitted by camels to humans (Omrani et al., 2015). MERS-CoV-infected individuals had respiratory tract infection, including dry cough and sore throat (Memish et al., 2013a, 2013b). Gastrointestinal symptoms were also described as common symptoms in patients with MERS-CoV. One study showed that 35% of diagnosed patients had gastrointestinal symptoms (Assiri et al., 2013a). In a descriptive study, similar results were obtained. Of the 47 patients with MERS-CoV, 17% of patients had abdominal pain, 21% of patients had vomiting, and 26% of patients had diarrhea (Assiri et al., 2013b). At the same time, MERS-CoV can also be detected in stool samples of patients (Zhou et al., 2017), indicating it possessed a fecal-oral transmission ability.

Unlike SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV entered host cells by recognizing cell surface receptor dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) (Raj et al., 2013). DPP4 was a serine exopeptidase, which can cut various substrates, enabling it to be engaged in multiple pathophysiological progresses (Enz et al., 2019). Mechanically, the attachment and fusion of virus and host cells were induced by the combination of MERS-CoV spike glycoproteins and β-propeller domain of DPP4 (Lu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Notably, a large amount of DPP4 expression was detected in intestinal epithelial tissue, suggesting gastrointestinal tract became a potential target of MERS-CoV (Nargis and Chakrabarti, 2018). MERS-CoV spike glycoproteins can also recognize glycotopes in sialic acid whose function as an attachment factor to assist receptor DPP4 (Li et al., 2017). Moreover, spike glycoproteins were combined with some proteases (including TMPRSS2) of host cell to allow MERS-CoV to fuse with cell membrane, so that viral RNA was injected into cell to complete infection (Shirato et al., 2013; Millet and Whittaker, 2014; Earnest et al., 2017). The virus invasion induced by TMPRSS2 indicated that SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV have same infection mechanism, which provided approaches for clinical treatment.

There was increasing evidence that MERS-CoV infection often triggered high expression levels of inflammatory cytokines throughout body (Kindler et al., 2016). Meanwhile, cytokine storm could be induced by stimulation of a large number of cytokines, generating dramatic harmful consequences of inflammation responses (Clark and Vissel, 2017; Channappanavar and Perlman, 2017). The inflammation level of patients was positively correlated with degree of gastrointestinal lesions. Compared to healthy controls, Mahallawi et al. (2018) found pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-15 and IL-17) markedly increased in MERS-CoV patients. Furthermore, MERS-CoV infection was considered to promote Th17 cytokine production, thereby inducing expression of inflammation cytokines and chemokines (McGeachy et al., 2019). However, exact mechanism that MERS-CoV participates in gastrointestinal damage by regulating the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines remains to be further studied. Predictably, alleviating gastrointestinal symptoms by blocking abnormal release of inflammatory cytokines is an ideal choice for clinical treatment of MERS patients.

3.3. SARS-CoV-2 and gastrointestinal lesions

A previously unknown coronavirus, termed SARS-CoV-2, was firstly identified in December 2019 (Zhu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a). It was known that SARS-CoV-2 was believed to be etiologic agent of atypical pneumonia (COVID-19) that caused globally nearly 18.4 million confirmed cases, including over 697,000 deaths, reported to WHO as of August 5, 2020 (WHO, 2020b). At the beginning of the outbreak, the source of SARS-CoV-2 received great attention. At whole-genome level, Zhou et al. (2020) found SARS-CoV-2 was 96% identical to a bat coronavirus, suggesting that natural reservoir was bats. Lam et al. (2020) tested pangolin samples and found that pangolin-associated coronaviruses were similar to SARS-CoV-2, indicating that pangolin may be intermediate host of SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 patients showed typically fever and respiratory symptoms, nevertheless, some patients also presented with gastrointestinal manifestations, including diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain (Huang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020). Among 95 diagnosed patients, 24.2% had diarrhea, 17.9% had anorexia, and 17.9% had nausea (Lin et al., 2020). Furthermore, in a meta-analysis of involving 4243 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 17.6% of patients had impaired gastrointestinal function, mainly in the form of anorexia, diarrhea and vomiting (Cheung et al., 2020). Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms of infected patients could appear early in disease course, indicating gastrointestinal symptoms can be first symptoms in some cases (Wang et al., 2020b; Song et al., 2020). Fascinatingly, Wan et al. (2020) indicated COVID-19 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms were susceptible to serious disease. Hence, it can provide a basis for predicting disease progression. Furthermore, gastrointestinal lesions caused by multiple drugs should also be taken seriously. Regrettably, there are no special drugs for COVID-19. However, excitingly, remdesivir and dexamethasone are confirmed to have therapeutic effects on COVID-19 to some extent (Wang et al., 2020c; News: Nature, 2020). Additionally, Gao et al. (2020) developed a purified inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine candidate (PiCoVacc). The vaccine not only induced production of specific neutralizing antibodies, but also resisted attack of SARS-CoV-2. However, it will take some time for vaccine to be used clinically.

Through next-generation sequencing, it was found that SARS-CoV-2 was more similar to SARS-CoV (about 79%) than MERS-CoV (about 50%). The overlapping genome sequences between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 can encode and express spike glycoproteins that could bind to ACE2 to enter target cells (Lu et al., 2020). Meanwhile, ACE2 was also identified as a functional receptor for SARS-CoV-2 to invade gastrointestinal cells (Zhou et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a). After virus entered cell, TMPRSS2 cleaved hemagglutinin and then activated internalization of virus (Stopsack et al., 2020). TMPRSS4 also played a similar role. Hence, TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 were considered as crucial protease in SARS-CoV-2 intrusion and replication (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Matsuyama et al., 2020; Zang et al., 2020). Besides high expression of ACE2 receptors in gastrointestinal tissues (Garg et al., 2020), viral nucleocapsid protein was also detected in cytoplasm of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelium (Xiao et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020; Lamers et al., 2020). TMPRSS2 was abundantly expressed in ileum and colon (Burgueño et al., 2020). Increasingly, studies have shown that gut and lungs were somehow connected. In respiratory diseases, intestinal dysfunction was observed. Also, alterations in gut microbes affected lung function. For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increased small intestinal permeability in patients (Sprooten et al., 2018). Moreover, when influenza struck, endogenous bifidobacterium from the gut could enhance host resistance to influenza (Zhang et al., 2020). This bi-directional communication network between the gut and the lung is called the “gut-lung axis”. Apparently, gut-lung axis existed in SARS-CoV-2 infection. After SARS-CoV-2 invaded the lung, host immune system was activated and inflammatory cytokines were released. Pulmonary permeability was increased with the release of inflammatory cytokines, which further led to viral invasion of the gut through the gut-lung axis, and vice versa (Ahlawat et al., 2020). In these processes, the intestinal flora acted as a “bridge”. Thus, regulating intestinal flora can improve intestinal lesions and even lung damage. However, another issue must be considered: whether excessive viral prophylaxis may disturb the patients’ flora balance and exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms. For example, sodium hypochlorite is commonly used for daily disinfection. Hypochlorite, when dissolved in water, can form hypochlorous acid in the mucous membranes of the mouth and intestines. It is extremely unstable and rapidly breaks down into hydrochloric acid and free oxygen radicals, which in turn destroys cellular proteins, including gut microbes. Mild gastrointestinal reactions can occur in individuals after ingestion, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (Slaughter et al., 2019). Thus, it is known that some disinfectants can disrupt intestinal microbial homeostasis and intestinal function through direct or indirect pathways. It is extremely important to use proper precautions against SARS-CoV-2.

The destruction of host immune function and formation of cytokine storm are considered to be crucial grounds for deterioration and even death of COVID-19 patients (Ye et al., 2020). Clinical observations found that in addition to typical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, some patients developed dramatical inflammatory responses. Inflammatory responses can be attributed to rapid viral replication, cellular damage and virus-induced ACE2 downregulation (Fu et al., 2020). Among them, rapid viral replication can promote cell death and activate immune cells, and then induce over-expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Cole and Ho, 2017). High expression levels of inflammatory cytokines have been detected in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Meanwhile, after infection with SARS-CoV-2, downregulation of ACE2 can facilitate expression of IL-6, which is main cytokine of cytokine storm. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) secreted by immune cells can activate inflammatory cells, thereby producing more cytokines, including IL-6 (Pedersen and Ho, 2020). When balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines was broken, cytokine storm formed, triggering MOF eventually (Mehta et al., 2020). Severe patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were observed to show cytokine storm that caused damage to organs throughout body, especially gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, blocking IL-6 signaling pathway to reduce occurrence of cytokine storm has a promising relief effect on COVID-19 patients' gastrointestinal symptoms.

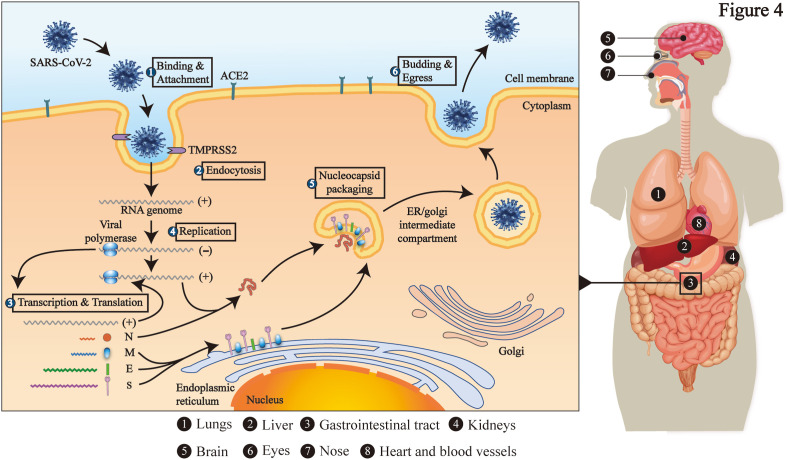

4. Apocalypse now from the past

At present, SARS-CoV-2 has posed a huge threat to the world. From brain to toes, most of body's organs are targeted by CoVs (Fig. 4 ). In the largest autopsy results currently, virus particles are present in multiple organs, especially in gastrointestinal tract (Bian, 2020). It can be concluded that they could destroy gastrointestinal tract by directly infecting host cell or triggering body's immune responses, thereby causing gastrointestinal symptoms. On the one hand, gastrointestinal symptoms can be regarded as the first symptom after SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the other hand, patients with gastrointestinal symptoms should also actively carry out symptomatic treatment in order to promote improvement of systemic symptoms and cut off fecal-oral transmission (Xie and Chen, 2020). Hence, it is necessary to gain experience in controlling gastrointestinal symptoms from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections.

Fig. 4.

The target organs attacked by SARS-CoV-2 and its infection mechanism. The whole-body organs of the human body may become the target of SARS-CoV-2 attack. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 enters the target cell with the help of the ACE2 and TMPRSS2, and completes its own replication, eventually destroying the cell.

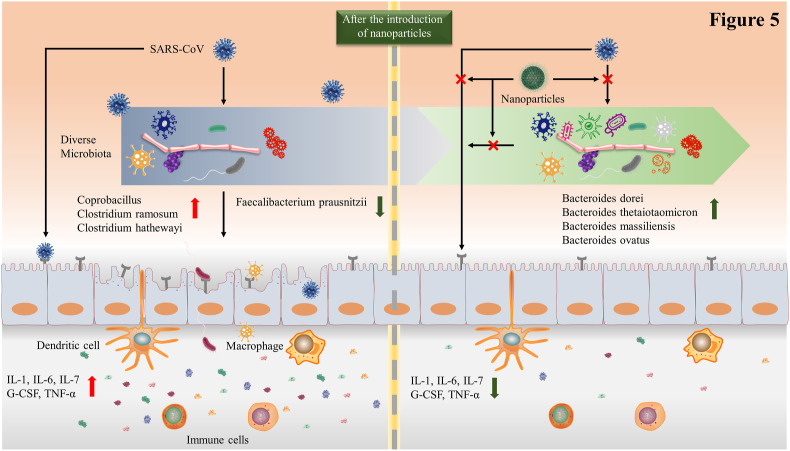

It should be noted, entire intestine should be considered as a steady state. Nevertheless, COVID-19 patients' gastrointestinal conditions are not optimistic. Compared with healthy controls, COVID-19 patients’ opportunistic pathogens increased, and beneficial commensals decreased. At genus level, decreased levels of Clostridium and Bacteroides were observed in some COVID-19 patients. It was further found that Bacteroides dorei, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides massiliensis, and Bacteroides ovatus could downregulate expression level of ACE2, and was inversely correlated with SARS-CoV-2 load in fecal samples (Zuo et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). ACE2 downregulation increased abundance of opportunistic pathogens and gut dysbiosis via decreasing secretion of antimicrobial peptides (Dupont et al., 2014), which indicated that gut microbiota may affect SARS-CoV-2 ability to invade gastrointestinal tract. It is known that gut microbiota can participate in systemic health by regulating immune homeostasis (Meng et al., 2019). Consequently, it can be conjectured that gastrointestinal symptoms and imbalance of immune homeostasis triggered by SARS-CoV-2 can be partly mediated by gut microbiota. It could be a potential treatment strategy to relieve gastrointestinal symptoms via targeted regulation of intestinal species in COVID-19 patients.

Taking into account possible interactions between gut microbiota and SARS-CoV-2, dietary strategies to restore beneficial commensals have been gradually concerned, especially joint application of nanotechnology (Kalantar-Zadeh et al., 2020). In view of the similarity between size of SARS-CoV-2 and nanoparticles, nanotechnology can be used to design intelligent drugs that target problematic bacterial strains in gastrointestinal tract. Correspondingly, gut barriers against SARS-CoV could be enhanced and gastrointestinal symptoms could be relieved (Sportelli et al., 2020). Notably, nano-vaccines, with their unique advantages, have become a new option for treating SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 5 ). Using nanotechnology to surface functionalization of nanoparticles, nano-vaccines can achieve strong immunogenicity (Nikaeen et al., 2020; Nasrollahzadeh et al., 2020). Nanomaterials are versatile and can be used in all aspects of viruses. Nanomaterials for disinfection have also been explored. Metal nanoparticles, especially silver nanoparticles, can serve as an effective broad-spectrum antiviral agent (Rai et al., 2016). However, their antiviral activity is still to be explored in COVID-19. The rapid spread of viruses requires improved detection efficiency. The high surface and volume ratios of nanomaterials improves the sensor's response, thereby increasing sensitivity. For example, specific probes functionalized with gold are able to form disulfide bonds with complementary RNA of the target virus. This can be used for rapid symptomatic and asymptomatic screening for COVID-19 (Li et al., 2020b). In addition to diagnostic screenings, nanomaterials can be used to design drugs. Virus-like particles (VLPs), a bionic nanoparticle that are commonly used for vaccine preparation, show considerable potential for application in COVID-19 (Pushko and Tretyakova, 2020). The VLP vaccine induces comprehensive humoral and cellular immunity. On the one hand, the VLP vaccine specifically recognizes B cell receptors and activates B cells. As a result, activated B cells further differentiate into plasma cells and produce antibodies, such as IgG and IgA (MacLennan et al., 2003). On the other hand, VLP vaccine promotes maturation of dendritic cells (DCs) and activates T cells subsequently, triggering cell-mediated immune response (Kwon et al., 2005). Antigen presentation and co-stimulatory molecules jointly induce DC maturation. In nano-vaccine, adjuvant acts as costimulatory molecules and viral proteins provides antigen. In another strategy, Wu et al. (2005) indicated that siRNA inhibited SARS-CoV replication in the Vero E6 cell line. Given the similarities between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, nanoparticles containing siRNA functional sequences could be hypothesized to be used for COVID-19. Thus, nanotechnology can mobilize the body's immunity in response to SARS-CoV-2 infections through multiple pathways.

Fig. 5.

Nanoparticles are used to strengthen the intestinal barrier against SARS-CoV-2 invasions. SARS-CoV-2 can interact with intestinal microbes, resulting in decreased microbial diversity. At the same time, intestinal microbes can regulate the expression level of ACE2 and affect the virus's ability to invade. Moreover, the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines also increase accordingly. However, targeted nanoparticles can block these pathways, and then restore intestinal microbial diversity, reduce inflammation levels, and improve intestinal barrier capabilities.

However, conventional and subunit vaccines do not have these advantages. Vigilantly, secondary damages caused by nanoparticles have to be considered, including oxidative stress, genotoxicity and inflammation (Sivasankarapillai et al., 2020). These problems are still keys that should be resolved in present and future. Overall, nanoparticles can directly target SARS-CoV particles via immune system in gastrointestinal tract. Meanwhile, specific nanoparticles can interact with gut microbiota to relieve viral gastrointestinal damage. These applications of nanotechnology may help us to prioritize to remodel homeostasis of gut microbes via targeting SARS-CoV-2 in order to reduce severity of gastrointestinal lesions.

5. Conclusions

The gastrointestinal lesions caused by three highly pathogenic coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2) are clarified. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 not only exhibit similar clinical manifestations, but mechanism of infection of target cells, especially in gastrointestinal tissue. Currently, the application of the vaccine still takes a long time. Treatment strategies for SARS-CoV-2 infection considering gut microbiota has received great attention (Li et al., 2020a). The effects of SARS-CoV-2 on gastrointestinal tract could be mediated by gut microbiota, hence, it has become a potential treatment strategy for COVID-19 patients, whether to relieve gastrointestinal or systemic symptoms. It is worth mentioning application of nanotechnology targeting gut microbiota. However, it should still be warned that some drugs with therapeutic effects may become toxic after being metabolized by gut microbiota (Ke et al., 2020; Javdan et al., 2020). Therefore, patients with gastrointestinal lesions should be requested to be treated with drugs that could both protect gastrointestinal functions. There are multiple important changes which need to be made so that God untie Gordian Knot and end the epidemic as soon as possible.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 81700522]; the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province [1808085MH235, 1908085QH328]; the University Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Province [KJ2018A0203]; the Grants for Scientific Research of BSKY from Anhui Medical University [XJ201706].

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

2019 novel coronavirus disease

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ACE2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- CoV

Coronavirus

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- DC-SIGN

Dendritic cell specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing non-integrin

- DPP4

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- E

Envelope protein

- HE

Hemagglutinin esterase

- IP-10

Interferon gamma-induced protein 10

- IL-1

Interleukin

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- M

Membrane protein

- MERS-CoV

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MHV

Mouse hepatitis virus

- MOF

Multiple organ failure

- N

Nucleocapsid protein

- SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SARS-Cov-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- ssRNA

Single-stranded RNA

- S

Spike glycoprotein

- TMPRSS2

Transmembrane protease serine type 2

Author statement

Meng Xiang and Lou Qiu-yue: Software, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. Yang Wen-ying and Chen Ran: Writing - Review & Editing. Meng Xiang, Yang Yang and Xu Wen-hua: Visualization, Supervision. Zhang Lei, Xu Tao and Xiang Hui-fen: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

The National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 81700522] -for the design of the study; the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province [1808085MH235, 1908085QH328] -for the collection of data; the University Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Province [KJ2018A0203] -for the analysis of data; the Grants for Scientific Research of BSKY from Anhui Medical University [XJ201706] -for the collection of data.

Author agreement

All authors have read and approved to submit it to your journal. There is no conflict of interest of any authors in relation to the submission.

References

- Ahlawat S., Asha, Sharma K.K. Immunological co-ordination between gut and lungs in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Virus Res. 2020;286:198103. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi J.K., Capili B. Nausea and vomiting in HIV/AIDS. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2011;34:15–24. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e31820b256a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi Y.M., Arifi A.A., Balkhy H.H., Najm H., Aldawood A.S., Ghabashi A., Hawa H., Alothman A., Khaldi A., Al Raiy B. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160:389–397. doi: 10.7326/M13-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A.T., Alabdullatif Z.N., Assad M., Almulhim A., Makhdoom H. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., Flemban H., Al-Nassir W.N., Balkhy H.H., Al-Hakeem R.F. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian X.W., the Covid-19 Pathology Team Autopsy of COVID-19 victims in China. National Science Review. 2020 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas K., Chatterjee D., Addya S., Khan R.S., Kenyon L.C., Choe A., Cohrs R.J., Shindler K.S., Das Sarma J. Demyelinating strain of mouse hepatitis virus infection bridging innate and adaptive immune response in the induction of demyelination. Clin. Immunol. 2016;170:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond C.W., Leibowitz J.L., Robb J.A. Pathogenic murine coronaviruses. II. Characterization of virus-specific proteins of murine coronaviruses JHMV and A59V. Virology. 1979;94:371–384. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgueño J.F., Reich A., Hazime H., Quintero M.A., Fernandez I., Fritsch J., Santander A.M., Brito N., Damas O.M., Deshpande A. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry molecules ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the gut of patients with IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020;26:797–808. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. Vet. Res. 2007;38:281–297. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.W., To K.K.W., Tse H., Jin D.Y., Yuen K.Y. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K.S., Hung I.F., Chan P.P., Lung K.C., Tso E., Liu R., Ng Y.Y., Chu M.Y., Chung T.W., Tam A.R. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong cohort: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I.A., Vissel B. The meteorology of cytokine storms, and the clinical usefulness of this knowledge. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S.L., Ho L.P. Contribution of innate immune cells to pathogenesis of severe influenza virus infection. Clin. Sci. 2017;131:269–283. doi: 10.1042/CS20160484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., He L., Zhang Q., Huang Z., Che X., Hou J., Wang H., Shen H., Qiu L., Li Z. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J. Pathol. 2004;203:622–630. doi: 10.1002/path.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont A., Heinbockel L., Brandenburg K., Hornef M.W. Antimicrobial peptides and the enteric mucus layer act in concert to protect the intestinal mucosa. Gut Microb. 2014;5:761–765. doi: 10.4161/19490976.2014.972238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnest J.T., Hantak M.P., Li K., McCray P.B., Perlman S., Gallagher T. The tetraspanin CD9 facilitates MERS-coronavirus entry by scaffolding host cell receptors and proteases. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz N., Vliegen G., De Meester I., Jungraithmayr W. CD26/DPP4 - a potential biomarker and target for cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019;198:135–159. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erles K., Toomey C., Brooks H.W., Brownlie J. Detection of a group 2 coronavirus in dogs with canine infectious respiratory disease. Virology. 2003;310:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forni D., Cagliani R., Clerici M., Sironi M. Molecular evolution of human coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Cheng Y., Wu Y. Understanding SARS-CoV-2-mediated inflammatory responses: from mechanisms to potential therapeutic tools. Virol. Sin. 2020;1–6 doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00207-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q., Bao L., Mao H., Wang L., Xu K., Yang M., Li Y., Zhu L., Wang N., Lv Z. Rapid development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020:eabc1932. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg M., Royce S.G., Lubel J.S. Intestinal inflammation, COVID-19 and gastrointestinal ACE2-exploring RAS inhibitors. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;10:1111. doi: 10.1111/apt.15814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek T.B., Torensma R., van Vliet S.J., van Duijnhoven G.C., Adema G.J., van Kooyk Y., Figdor C.G. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramberg T., Hofmann H., Möller P., Lalor P.F., Marzi A., Geier M., Krumbiegel M., Winkler T., Kirchhoff F., Adams D.H. LSECtin interacts with filovirus glycoproteins and the spike protein of SARS coronavirus. Virology. 2005;340:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L.C., Lely A.T., Navis G.J., van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T., Perlot T., Rehman A., Trichereau J., Ishiguro H., Paolino M., Sigl V., Hanada T., Hanada R., Lipinski S. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012;487:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.F., Peng G.W., Min J., Yu D.W., Liang W.J., Zhang S.Y., Xu R.H., Zheng H.Y., Wu X.W., Xu J. Molecular evolution of the SARS coronavirus during the course of the SARS epidemic in China. Science. 2004;303:1666–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1092002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D.S., Azhar E.I., Kim Y.-J., Memish Z.A., Oh M.-D., Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: risk factors and determinants of primary, household, and nosocomial transmission. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:e217–e227. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata-Yoshikawa N., Okamura T., Shimizu Y., Hasegawa H., Takeda M., Nagata N. TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 2019;93:e01815–e01818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01815-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javdan B., Lopez J.G., Chankhamjon P., Lee Y.C.J., Hull R., Wu Q., Wang X., Chatterjee S., Donia M.S. Personalized mapping of drug metabolism by the human gut microbiome. Cell. 2020;181:1661–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar-Zadeh K., Ward S.A., Kalantar-Zadeh K., El-Omar E.M. Considering the effects of microbiome and diet on SARS-CoV-2 infection: nanotechnology roles. ACS Nano. 2020;14:5179–5182. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke W., Saba J.A., Yao C.H., Hilzendeger M.A., Drangowska-Way A., Joshi C., Mony V.K., Benjamin S.B., Zhang S., Locasale J. Dietary serine-microbiota interaction enhances chemotherapeutic toxicity without altering drug conversion. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2587. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16220-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kin N., Miszczak F., Lin W., Gouilh M.A., Vabret A. Genomic analysis of 15 human coronaviruses OC43 (HCoV-OC43s) circulating in France from 2001 to 2013 reveals a high intra-specific diversity with new recombinant genotypes. Viruses. 2015;7:2358–2377. doi: 10.3390/v7052358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler E., Thiel V., Weber F. Interaction of SARS and MERS coronaviruses with the antiviral interferon response. Adv. Virus Res. 2016;96:219–243. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipkorir V., Cheruiyot I., Ngure B., Misiani M., Munguti J. Prolonged SARS-cov-2 RNA detection in anal/rectal swabs and stool specimens in COVID-19 patients after negative conversion in nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning N., Kessen S.F.M., Van Der Voorn J.P., Appelmelk B.J., Jeurink P.V., Knippels L.M.J., Garssen J., Van Kooyk Y. Human milk blocks DC-SIGN-pathogen interaction via MUC1. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:112. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y.J., James E., Shastri N., Fréchet J.M.J. In vivo targeting of dendritic cells for activation of cellular immunity using vaccine carriers based on pH-responsive microparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:18264–18268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509541102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T.T.Y., Jia N., Zhang Y.W., Shum M.H.H., Jiang J.F., Zhu H.C., Tong Y.G., Shi Y.X., Ni X.B., Liao Y.S. Identifying SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers M.M., Beumer J., van der Vaart J., Knoops K., Puschhof J., Breugem T.I., Ravelli R.B.G., Paul van Schayck J., Mykytyn A.Z., Duimel H.Q. SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abc1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K.P., Fan R.Y.Y., Luk H.K.H., Zhu L., Fung J., Li K.S.M., Wong E.Y.M., Ahmed S.S., Chan J.F.W., Kok R.K.H. Replication of MERS and SARS coronaviruses in bat cells offers insights to their ancestral origins. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2018;7:209. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0208-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N., Hui D., Wu A., Chan P., Cameron P., Joynt G.M., Ahuja A., Yung M.Y., Leung C.B., To K.F. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W.K., To K.F., Chan P.K.S., Chan H.L.Y., Wu A.K.L., Lee N., Yuen K.Y., Sung J.J.Y. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.Y., Wu W., Chen S., Gu J.W., Li X.L., Song H.J., Du F., Wang G., Zhong C.Q., Wang X.Y. Digestive system involvement of novel coronavirus infection: prevention and control infection from a gastroenterology perspective. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:199–204. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Yi Y., Luo X., Xiong N., Liu Y., Li S., Sun R., Wang Y., Hu B., Chen W. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Hulswit R.J.G., Widjaja I., Raj V.S., McBride R., Peng W., Widagdo W., Tortorici M.A., van Dieren B., Lang Y. Identification of sialic acid-binding function for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:E8508–E8517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712592114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Jiang X., Zhang Z., Huang S., Zhang Z., Fang Z., Gu Z., Gao L., Shi H., Mai L. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020;69:997–1001. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G., Hu Y., Wang Q., Qi J., Gao F., Li Y., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Yuan Y., Bao J. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature. 2013;500:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan I.C.M., Toellner K.-M., Cunningham A.F., Serre K., Sze D.M.Y., Zúñiga E., Cook M.C., Vinuesa C.G. Extrafollicular antibody responses. Immunol. Rev. 2003;194:8–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahallawi W.H., Khabour O.F., Zhang Q., Makhdoum H.M., Suliman B.A. MERS-CoV infection in humans is associated with a pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cytokine profile. Cytokine. 2018;104:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra M.A., Jones S.J.M., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S.N., Khattra J., Asano J.K., Barber S.A., Chan S.Y. The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S., Nao N., Shirato K., Kawase M., Saito S., Takayama I., Nagata N., Sekizuka T., Katoh H., Kato F. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020;117:7001–7003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002589117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy M.J., Cua D.J., Gaffen S.L. The IL-17 family of cytokines in health and disease. Immunity. 2019;50:892–906. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish Z.A., Zumla A.I., Al-Hakeem R.F., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Stephens G.M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2487–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish Z.A., Zumla A.I., Assiri A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in health care workers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:884–886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1308698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Zhou H.Y., Shen H.H., Lufumpa E., Li X.M., Guo B., Li B.Z. Microbe-metabolite-host axis, two-way action in the pathogenesis and treatment of human autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019;18:455–475. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet J.K., Whittaker G.R. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:15214–15219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407087111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T., Harii N., Goto J., Harada D., Sugawara H., Takamino J., Ueno M., Sakata H., Kondo K., Myose N. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargis T., Chakrabarti P. Significance of circulatory DPP4 activity in metabolic diseases. IUBMB Life. 2018;70:112–119. doi: 10.1002/iub.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M., Sajjadi M., Soufi G.J., Iravani S., Varma R.S. Nanomaterials and nanotechnology-associated innovations against viral infections with a focus on coronaviruses. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:E1072. doi: 10.3390/nano10061072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaeen G., Abbaszadeh S., Yousefinejad S. Application of nanomaterials in treatment, anti-infection and detection of coronaviruses. Nanomedicine. 2020 doi: 10.2217/nnm-2020-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omrani A.S., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): animal to human interaction. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2015;109:354–362. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2015.1122852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S.F., Ho Y.C. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:2202–2205. doi: 10.1172/JCI137647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris J.S.M., Lai S.T., Poon L.L.M., Guan Y., Yam L.Y.C., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K.S., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris J.S.M., Yuen K.Y., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Stöhr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman S., Dandekar A.A. Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: implications for SARS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:917–927. doi: 10.1038/nri1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushko P., Tretyakova I. Influenza virus like particles (VLPs): opportunities for H7N9 vaccine development. Viruses. 2020;12:518. doi: 10.3390/v12050518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman B., Sadraddin E., Porreca A. The basic reproduction number of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan is about to die out, how about the rest of the World? Rev. Med. Virol. 2020:e2111. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai M., Deshmukh S.D., Ingle A.P., Gupta I.R., Galdiero M., Galdiero S. Metal nanoparticles: the protective nanoshield against virus infection. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;42:46–56. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2013.879849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj V.S., Mou H., Smits S.L., Dekkers D.H.W., Müller M.A., Dijkman R., Muth D., Demmers J.A.A., Zaki A., Fouchier R.A.M. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Peñaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M.-H. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Gong E., Gao D., Zhang B., Zheng J., Gao Z., Zhong Y., Zou W., Wu B., Fang W. Severe acute respiratory syndrome associated coronavirus is detected in intestinal tissues of fatal cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato K., Kawase M., Matsuyama S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection mediated by the transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J. Virol. 2013;87:12552–12561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01890-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulla A., Heald-Sargent T., Subramanya G., Zhao J., Perlman S., Gallagher T. A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J. Virol. 2011;85:873–882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02062-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons G., Reeves J.D., Rennekamp A.J., Amberg S.M., Piefer A.J., Bates P. Characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) spike glycoprotein-mediated viral entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivasankarapillai V.S., Pillai A.M., Rahdar A., Sobha A.P., Das S.S., Mitropoulos A.C., Mokarrar M.H., Kyzas G.Z. On facing the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) with combination of nanomaterials and medicine: possible strategies and first challenges. Nanomaterials. 2020;10 doi: 10.3390/nano10050852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter R.J., Watts M., Vale J.A., Grieve J.R., Schep L.J. The clinical toxicology of sodium hypochlorite. Clin. Toxicol. 2019;57:303–311. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2018.1543889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sola I., Almazán F., Zúñiga S., Enjuanes L. Continuous and discontinuous RNA synthesis in coronaviruses. Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:265–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Liu P., Shi X.L., Chu Y.L., Zhang J., Xia J., Gao X.Z., Qu T., Wang M.Y. SARS-CoV-2 induced diarrhoea as onset symptom in patient with COVID-19. Gut. 2020;69:1143–1144. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sportelli M.C., Izzi M., Kukushkina E.A., Hossain S.I., Picca R.A., Ditaranto N., Cioffi N. Can nanotechnology and materials science help the fight against SARS-CoV-2? Nanomaterials. 2020;10 doi: 10.3390/nano10040802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprooten R.T.M., Lenaerts K., Braeken D.C.W., Grimbergen I., Rutten E.P., Wouters E.R.M., Rohde G.G.U. Increased Small Intestinal Permeability during Severe Acute Exacerbations of COPD. Respiration. 2018;95:334–342. doi: 10.1159/000485935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopsack K.H., Mucci L.A., Antonarakis E.S., Nelson P.S., Kantoff P.W. TMPRSS2 and COVID-19: serendipity or opportunity for intervention? Canc. Discov. 2020;10:779–782. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Otake Y., Uchimoto S., Hasebe A., Goto Y. Genomic characterization and phylogenetic classification of bovine coronaviruses through whole genome sequence analysis. Viruses. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/v12020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnblom H., Abrahamsson H. Chronic nausea and vomiting: insights into underlying mechanisms. Neuro Gastroenterol. Motil. 2016;28:613–619. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici M.A., Walls A.C., Lang Y., Wang C., Li Z., Koerhuis D., Boons G.J., Bosch B.J., Rey F.A., de Groot R.J. Structural basis for human coronavirus attachment to sialic acid receptors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:481–489. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0233-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y., Li J., Shen L., Zou Y., Hou L., Zhu L., Faden H.S., Tang Z., Shi M., Jiao N. Enteric involvement in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 outside Wuhan. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:534–535. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Shi X., Jiang L., Zhang S., Wang D., Tong P., Guo D., Fu L., Cui Y., Liu X. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013;23:986–993. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S.R., Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C.K., Lam C.W.K., Wu A.K.L., Ip W.K., Lee N.L.S., Chan I.H.S., Lit L.C.W., Hui D.S.C., Chan M.H.M., Chung S.S.C. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004;136:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.J., Huang H.W., Liu C.Y., Hong C.F., Chan Y.L. Inhibition of SARS-CoV replication by siRNA. Antivir. Res. 2005;65:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G., Hu Y., Tao Z.W., Tian J.H., Pei Y.Y. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395:689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X., Liu Y., Li X., Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M., Chen Q. Insight into 2019 novel coronavirus - an updated interim review and lessons from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.W., Wu X.X., Jiang X.G., Xu K.J., Ying L.J., Ma C.L., Li S.B., Wang H.Y., Zhang S., Gao H.N. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Chakraborty S., Saha P., Mell B., Cheng X., Yeo J.Y., Mei X., Zhou G., Mandal J., Golonka R. Gnotobiotic rats reveal that gut microbiota regulates colonic mRNA of Ace2, the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Hypertension. 2020;76:e1–e3. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.Y., Huang Y., Ganesh L., Leung K., Kong W.P., Schwartz O., Subbarao K., Nabel G.J. pH-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is mediated by the spike glycoprotein and enhanced by dendritic cell transfer through DC-SIGN. J. Virol. 2004;78:5642–5650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5642-5650.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Wang B., Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020;80:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Fouchier R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang R., Gomez Castro M.F., McCune B.T., Zeng Q., Rothlauf P.W., Sonnek N.M., Liu Z., Brulois K.F., Wang X., Greenberg H.B. TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 promote SARS-CoV-2 infection of human small intestinal enterocytes. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Hu J., Feng J.W., Hu X.T., Wang T., Gong W.X., Huang K., Guo Y.X., Zou Z., Lin X. Influenza infection elicits an expansion of gut population of endogenous Bifidobacterium animalis which protects mice against infection. Genome Biol. 2020;21:99. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li J., Zhan Y., Wu L., Yu X., Zhang W., Ye L., Xu S., Sun R., Wang Y. Analysis of serum cytokines in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4410–4415. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4410-4415.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D., Yao F., Wang L., Zheng L., Gao Y., Ye J., Guo F., Zhao H., Gao R. A comparative study on the clinical features of COVID-19 pneumonia to other pneumonias. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Li C., Zhao G., Chu H., Wang D., Yan H.H.N., Poon V.K.M., Wen L., Wong B.H.-Y., Zhao X. Human intestinal tract serves as an alternative infection route for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Sci Adv. 2017;3 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo T., Zhang F., Lui G.C.Y., Yeoh Y.K., Li A.Y.L., Zhan H., Wan Y., Chung A., Cheung C.P., Chen N. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020;S0016–5085:34701–34706. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11.1 Web references

- News: Nature Coronavirus breakthrough: dexamethasone is first drug shown to save lives. Nature 2020. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01824-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01824-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2003. Summary of Probable SARS Cases with Onset of Illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003 (Based on Data as of the 31 December 2003)https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/ [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. MERS Situation Update, January 2020. (Based on Data as of the January 2020)http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/mers-cov/mers-outbreaks.html [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. (Based on Data as of the 5 August 2020)https://www.who.int/redirect-pages/page/novel-coronavirus-(covid-19)-situation-dashboard [Google Scholar]