Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) are a popular tool for detecting association between genetic variants or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and complex traits. Family data introduce complexity due to the non-independence of the family members. Methods for non-independent data are well established, but when the GWAS contains distinct family types, explicit modeling of between-family-type differences in the dependence structure comes at the cost of significantly increased computational burden. The situation is exacerbated with binary traits. In this paper, we perform several simulation studies to compare multiple candidate methods to perform single SNP association analysis with binary traits. We consider generalized estimating equations (GEE), generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs), or generalized least square (GLS) approaches. We study the influence of different working correlation structures for GEE on the GWAS findings and also the performance of different analysis method(s) to conduct a GWAS with binary trait data in families. We discuss the merits of each approach with attention to their applicability in a GWAS. We also compare the performances of the methods on the alcoholism data from the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research (MCTFR) study.

Keywords: family data, population-based association analysis, genome-wide scan, generalized estimating equation, generalized linear mixed effect model, generalized least squares

1. Introduction

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) seek to detect associations between genetic variants and observed disease phenotypes. Many such GWASs involve analyzing family data (Duerr et al., 2006; Graham et al., 2008; Benyamin et al., 2009), but explicit modeling of the dependencies among the family members introduces additional complexities. The observations within a family are correlated due to both shared environment and shared genes, which complicates the statistical modeling. Methods for analyzing quantitative traits with family data have been well developed; methods for conducting a genome-wide association study with binary traits have received less attention. One class of methods for analyzing binary family data, generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs), introduces random effects into the statistical models to account for the within-family dependencies. Other methods, such as generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Liang and Zeger, 1986) estimate the marginal, population-averaged effect of a genetic variant on the phenotype.

Another class of approach (EMMAX, RFGLS) (Zhou and Stephens, 2012; Li et al., 2011) treats the binary trait as quantitative and uses generalized least square (GLS) approach to perform the single SNP association analysis. The GLS approach provides a computationally faster way of analyzing this complex correlated binary data. In a GWAS, where the main purpose is to detect the potential associations, we aim to investigate which of these three alternative approaches provide computational optimality without sacrificing much power while maintaining correct type I error.

Our work is primarily motivated by the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research (MCTFR) dataset, where we have 4-member nuclear families with 3 different ‘family types’ such as monozygotic-twin offspring (‘MZ’ families), dizygotic-twin offspring and non-twin full siblings (‘DZ’ families), and adoptive offspring (‘Adopted’ families). Statistical modeling of phenotypes from these families present substantial challenges since the correlation structure varies between family types. MZ twins share all their genetic material and thus tend to be more alike than the DZ twins or full siblings. The adopted siblings do not share any genetic component, but share familal environment. In a GWAS, where SNP-phenotype association detection is the primary goal, explicit modeling of these differences between family types can be computationally demanding, but ignoring the dependency may result in an increased number of false positives. For quantitative traits, one can typically address the problem with linear mixed effect models; for binary traits the issue is more problematic due to computational complexity and because we lack well-defined multivariate distributions for characterizing correlated binary outcomes. These alternative approaches could produce dissimilar association results. However, there are few independent evaluations of these methods (Chen et al., 2011; Eu-Ahsunthornwattana et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2018). It is important to understand the behavior of these popular GWAS programs, and their sensitivity to sample size and the study design.

In this paper, we conducted several simulation studies using three alternative approaches mentioned above to analyze binary data, with special attention to differences between family types. We discuss the relative merits of the different approaches, describing how these methods can model the familial dependency structures. We also show that differences between family types can be accounted for with the existing R packages for GEE using only slight additions to its existing functionality. These methods are not unique to a GWAS and can be adapted to other situations with correlated binary data among different clusters. Based on our findings, we give recommendations for a GWAS with binary outcomes in families. Finally, we use the methods to analyze alcoholism data in MCTFR cohort (Miller et al., 2012) and discuss the performance of the methods.

2. Methods

For all models, let yij be the observed binary phenotype for individual j in family i, j = 1, …, ni (ni = 4 for our data), . Let xij (1 × p) denote the individual’s vector of covariates, and Gij denotes the additive genetic score of a SNP, taking values 0,1, or 2 depending on the number of minor alleles for individual j. For parents and adoptive offspring, we simulate data on a single SNP from a Binomial (2,m) distribution, where m is the minor allele frequency (MAF) of the SNP. The genotype data on an biological offspring are simulated in accordance with Mendel’s Law of Segregation.

2.1. Analysis Models

As candidate models for analyzing binary traits in a GWAS, we consider GLMMs, GEE, and GLS methods.

2.1.1. GLMMs

For a single-variant test, we consider the following logistic mixed model (Chen, 2019):

| (1) |

where pij = P(yij = 1|xij,Gij, uij) is the probability of a binary phenotype (e.g., disease status) for subject j in family i, conditional on their covariates, genotype, and random effects, β is a p × 1 column vector of fixed covariate effects including an intercept, and γ is the genotype effect. Let uij represent the random effect corresponding to i-th family and j-th individual. It is assumed that the n × 1 column vector of the random effects, , where τr’s are the variance component parameters and Cr’s are known n × n relationship matrices. In family data, usually two variance components namely, additive genetic (τ1) and shared environmental (τ2) are considered with C1 being the known familial genetic relationship matrix and C2 being a block-diagonal matrix with matrices of all ones corresponding to each family on its diagonals (Rabe-Hesketh et al., 2008). We would refer to this modeling framework as general GLMM throughout this paper. In case of distantly related individuals with unknown familial relationships, only the additive genetic component is considered with C1 being the genetic relationship matrix (Yang et al., 2011) estimated from a large number of genetic variants.

The general GLMM framework above easily gets computationally intensive as the number of families increases. For our simulation study, we considered a simple random intercept model where it is assumed that uij’s are same over the individuals of family i, i.e, uij = ui ~ N(0, τ). It represents the random effect corresponding to i-th family, i = 1,2, …, K. This random intercept model captures the effect of familial clustering, i.e. the fact that individuals within a family tend to be alike phenotypically. But the model does not explicitly model the within-family correlation structure, nor does it differentiate between family types, such as MZ twin families, DZ twin families, etc. This simple model can be thought of as a special case of the general GLMM with τ1 = 0, and τ2 = τ with C2 as described before.

We also propose a generation-effects model for our MCTFR families, which is a further generalization of the above GLMM. Here the random effect uij’s are considered to be,

where ui and bi are random effects capturing different shared environment for each generation. The model allows for varying levels of heterogeneity between parent-pairs and offspring-pairs with offspring variance var(ui) = τ, and parental variance . The covariance between a parent and an offspring is τ.

2.1.2. GEE

Here we consider a marginal model to estimate the population averaged effect of a genetic variant on a binary trait using generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Hardin and Hilbe, 2012). A very convenient feature of GEE is that we need not fully specify a multivariate distribution for the outcome variable nor make any assumptions on distributions of family-specific random effects. The GEE approach requires a model for the mean response (as a function of covariates), the variance (often specified as a function of the mean) and a working correlation assumption. For example, with binary data, we would consider

| (2) |

where g is the logit link to describe the relationship between the mean and the covariates. The mean-variance relationship is ν(μij) = μij(1 − μij). Let Ai be a ni × ni diagonal matrix with ν(μij) on its j-th diagonal. GEE considers the family specific covariance structure to be, where Ri is a user specified working correlation matrix describing the correlation among the outcome variables yij within family i. For the working correlation matrix the user can specify, for example, Independence, where observations within a family are assumed to be uncorrelated; or Exchangeable, where all observations within a family are correlated, and all pairwise correlations are equal. This model is called a marginal model since the dependency between the individuals are being captured marginally without considering any subject specific random effect unlike the GLMMs. We shall note that the mean model in equation (2) is the same as that in equation (1) without the the random effect term.

Finding out a consistent estimator of the variance structure Vi, call it , the mean parameter estimates are obtained as the solutions of

where the vector is the solution to the equations. The parameter estimates have the same interpretation as in traditional binary regression with logit or probit link. But in contrast to the mixed effect models, the fixed effects are averaged over the population, so the interpretation is for the population as a whole and is not conditional on the random effects. In mixed-effect models the interpretation of the fixed effects are family-or subject-specific; that is, they are conditional on the random effects. The GEE model allows flexibility in estimating the correlation structure, and is computationally more tractable than GLMM. But because GEE is not a traditional likelihood-based method, GLMM provides more effcient estimates if the model assumptions are true.

GEE offers multiple options for estimating the covariance of parameter estimates (Liang and Zeger, 1986; Halekoh et al., 2006). The covariance matrix of the vector is generally estimated with the robust ‘sandwich’ covariance estimator

where cov(yi) is the empirical covariance matrix of yi. The estimator sandwiches the empirical covariance by the working covariance to consistently estimate cov(β*). As an alternative one can use the jackknife covariance estimator, defined as

where K is the number of clusters or families, p is the number of regression parameters, and are the estimates of β* found excluding the ith cluster. The jackknife estimator tends to perform better than the sandwich estimator for relatively small sample sizes, e.g. roughly ≤ 30 clusters (Paik, 1988). It is available as an estimator through the full iterations of Fisher scoring, the algorithm used to solve for parameter estimates in GEE, or as a one-step jackknife, which is somewhat less accurate than the fully-iterated jackknife but generally giving close agreement. The fully-iterated jackknife estimator is asymptotically equivalent to the sandwich covariance estimator (Lipsitz et al., 1994).

2.1.3. Generalized least squares (GLS)

Finally, we consider GLS methods. Although model assumptions are violated when the trait is binary, the models may nevertheless perform well for large sample sizes, and in general they are much less computationally burdensome than GLMMs, making these methods attractive for a large-scale GWAS. For quantitative traits with correlated data, the generalized least squares (GLS) method generally assumes a linear model of the form

Although assumption of multivariate normality is not required for the least squares methods, it is nevertheless quite common. With family data, V is usually modelled in a similar way as the GLMMs (Rabe-Hesketh et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011),

| (3) |

τ1, τ2, respectively correspond to the additive genetic, shared environmental and non-shared environmental variance components and is an identity matrix of dimension n × n. One can estimate these variance parameters first to get an estimate of . Next, calculate , with and perform a standard linear regression of the form,

since under the model assumptions,

where ϵt are the residuals from the model of the rotated data. Rapid Feasible Generalized Least Squares (RFGLS) is a method designed for SNP association studies with quantitative traits in family studies (Li et al., 2011) that follows the above algorithm. The method uses a computationally-efficient approach by estimating the variance parameters mentioned in equation (3) and thus, the residual covariance matrix (V) without the SNP effect, then performing GLS in the GWAS using this estimate. Provided that the SNP effect is small, accounting for less than 1% of the phenotypic variance, the method provides considerable computational advantage over similar GWAS methods. Furthermore, the method offers flexibility in allowing estimation of distinct covariance matrices for different family types while keeping the model parameters to a minimum. GLS methods are generally not suitable for binary phenotypes, because most GLMMs use a non-linear link function and because GLS model assumptions are violated with binary data. Nevertheless we include the model due to its ease in modeling the familial dependency structure and due to its computational efficiency.

Efficient-Mixed-Model Association eXpedited (EMMAX) (Kang et al., 2010) is a statistical test commonly used for association studies with distantly related individuals. The method accounts for population stratification and distant relatedness using a variance components approach similar to equation (3). Unlike RFGLS that can only handle family data and uses a known familial genetic relationship matrix (C1), EMMAX can handle more general relationships and uses a genetic relationship matrix (C1) that is estimated using genome wide marker data of the available individuals. Similar to RFGLS, the method improves computational efficiency by estimating a polygenic covariance matrix and subsequently using the estimate in all single-SNP analyses. Like RFGLS, the method was designed for quantitative traits but has been successfully applied to case-control studies (Allen-Brady et al., 2011; Teerlink et al., 2012).

2.2. Simulation 1: selection of working correlation matrix for GEE

To find the optimal working correlation matrix with GEE, we simulated data under a marginal model for 3 family types (‘MZ’, ‘DZ’, ‘Adopted’) under 4 different conditions: independence (IND), in which phenotypes within families are uncorrelated; exchangeable (EX), in which phenotypes within families are correlated, all within-family pairwise correlations are equal, and the correlations are equal across family types; unstructured (UN), in which all pairwise correlations within families are unequal, but the correlations are equal across family types; or totally unstructured (TU), in which all within-family pairwise correlations are unequal, and each of the 3 family types has a unique correlation structure. Total sample sizes were 3600 (300 families of each type), 7200 (600 families of each type), and 7200 (900 of family type 1, 800 of family type 2, and 100 of family type 3). This last case will be referred to as ‘7200 (unbalanced)’. The last case was included as a more realistic representation of GWAS family data. For each combination of sample size and correlation structure we generated 10,000 datasets for analysis. Genotype data (Gij) was simulated first for all the individuals with MAF of 0.2. The mean model from equation (2) was then considered to simulate μij’s with no covariates and α such that the trait prevalence remains 0.10 under the null model, H0 : γ = 0. Two setups were considered, the null model with γ = 0 and an alternative model with γ = 0.22. Next, We used Gaussian copula (the details can be found in the section (3.3) of the paper: Madsen and Birkes (2013)) to simulate the binary phenotype capturing the familial correlation. Type I error is reported as the proportion of models with p < 0.05 under the data with γ = 0. Power reported is empirical power, i.e., the proportion of test statistics under the model with γ ≠ 0 that exceeded the 0.95 quantile of the test statistics from the null data sets.

We analyzed each dataset using R package geepack (Halekoh et al., 2006), using the same 4 correlation structures the were used in the simulation: each dataset was analyzed 4 separate times under the assumptions of IND, EX, UN, or TU dependency regardless of the true dependency structure; that is, we specified a working correlation structure of independence (IND), where individuals in a family are assumed to be uncorrelated, or exchangeable (EX), where individuals within a family are assumed to be correlated, and all pairwise correlations are equal, etc. For all analyses, we used the sandwich covariance estimator. Currently geepack does not directly allow estimation of separate correlation matrices for different family (or more generally, distinct cluster) types with a built-in function. We used custom code to implement this feature for the TU analysis.

2.3. Simulation 2: comparison of GLMMs, GEE, and GLS

Simulation 2 was designed to compare the analysis methods on datasets generated under either a mixed model (setup of general GLMM) or a marginal model (setup of GEE). For convenience, we refer to data generated under marginal models and mixed models as ‘marginal data’ and ‘mixed data’, respectively. For mixed data, we simulated genotypic data (Gij) on 400 4-member families, 200 MZ families and 200 DZ families. pij’s were simulated using equation (1). Two setups were considered. In the first case, ‘Case 1’, uij’s were simulated from the multivariate normal distribution with both the additive genetic variance (τ1) and the environmental variance (τ2) (i.e, u ~ N(0,τ1C1 + τ2C2)). The second case differed from the first one only in that the parents’ covariance term was set to 0, i.e., parents’ phenotypes were uncorrelated. Binary phenotype yij for each i,j, was simulated from a Bernoulli distribution with probability pij.

Marginal data were simulated as in simulation 1 above with a few differences. Regression coefficients used in simulation 2 were estimated from the mixed datasets for the marginal models (see (Agresti and Kateri, 2011) on marginal vs. conditional models). With the estimated SNP effect and given MAF, the intercept term was solved numerically to arrive at the desired trait prevalence. For simulation 2, marginal data were simulated with exchangeable correlation matrix only.

Across these conditions, we used 4 combinations of MAF and trait prevalence: MAF = 0.20, prevalence = 0.20; MAF = 0.05, prevalence = 0.20; MAF = 0.20, prevalence = 0.10; MAF = 0.05, prevalence = 0.10. For each combination of MAF, prevalence, we generated 10,000 datasets for analysis. For each dataset under these scenarios and each marginal dataset, we analyzed the data using, two types of GLMM namely, the random intercept model and the generation-effects model; RFGLS; EMMAX; GEE with an unstructured working correlation matrix and the sandwich covariance estimator, ‘GEE(UN)’; GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and the fully-iterated jackknife variance estimator, ‘GEE(FIJ)’ and GEE with independence working correlation matrix and the sandwich covariance estimator, ‘GEE(IND)’. The random intercept model, generation-effects model, all the GEE models, and RFGLS were fit respectively with the R packages lme4 (Bates, 2010), geepack (Halekoh et al., 2006) and RFGLS (Li et al., 2011). EMMAX estimates genetic relatedness on all genetic markers within a dataset. Thus for each dataset, we generated 1000 SNPs independently of the trait. These SNPs were used strictly by EMMAX for estimating genetic relatedness. EMMAX analyses with the standalone EMMAX software.

2.4. Simulation 3: comparison of GLMMs, GEE, and GLS using MCTFR data

To replicate more realistic scenarios, we used the real genetic data from the MCTFR study (Miller et al., 2012) to perform a bunch of simulation exercises. Included in the analysis were 5,352 white individuals with 2214 families representing independent observations and families of size 2–4. There were 527,829 many single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers.

From each of the first twenty chromosomes, we randomly selected 2 SNPs in low LD (r2 LD less than 0.2) giving us a set of 40 SNPs. We used R package SNPRelate (Zheng, 2013) for LD calculation and pruning. Next, we considered two scenarios: Case (1): all 40 SNPs are causal i.e the number of causal SNPs is: mc = 40 and Case (2): out of the selected 40 SNPs, only 20 (one from each chromosome) are causal i.e the number of causal SNPs is: mc = 20. For each of these cases, a number of sub-cases were considered which would be described next. We simulated the binary trait using the very popular liability threshold model (Harville and Mee, 1984; Lee et al., 2011). First, a continuous liability vector (l) was simulated as,

where and G is the mean and variance centered causal genotype matrix. So, the variance of an individual liability is,

h2 is the heritability of the liability vector, a denotes the fraction of heritability that is taken into account as SNP effect and (1−a) is the fraction of heritability that is taken into account as the additive genetic variance component τ1. b is the fraction of the remaining variance (1 − h2) that is considered to be shared environmental variance component and (1 − b) is the fraction that is the non-shared environmental variance component. Under each case, we considered a few combinations of the parameter values,

Sub-case (1): h2 = 0.95, a = 1/40, b = 1/2.

Sub-case (2): h2 = 0.95, a = 2/40, b = 1/2.

Sub-case (3): h2 = 0.4, a = 1/40, b = 1/2.

Sub-case (4): h2 = 0.4, a = 5/40, b = 1/2.

Using the liability vector l and a prevalence cut-off of 0.1, we generated the binary trait Y as, yij = 0 if lij is less than the 0.9th quantile of lij values and yij = 1 otherwise. For analysis, we considered the general GLMM, GEE(UN) and RFGLS. The results are discussed in Section (3.3).

2.5. The MCTFR GWAS study

As a complement to the simulation studies presented above, we analyzed the alcoholism trait from the MCTFR data. Included in the analysis were 5,352 white individuals with 2214 families representing independent observations and families of size 2–4. Alcoholism prevalence was 0.27. We included participant age, sex, and the 10 principal components for ethnicity as covariates. For analysis of this dataset, we considered the general GLMM, GEE(UN) and RFGLS.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation 1: selection of working correlation matrix for GEE

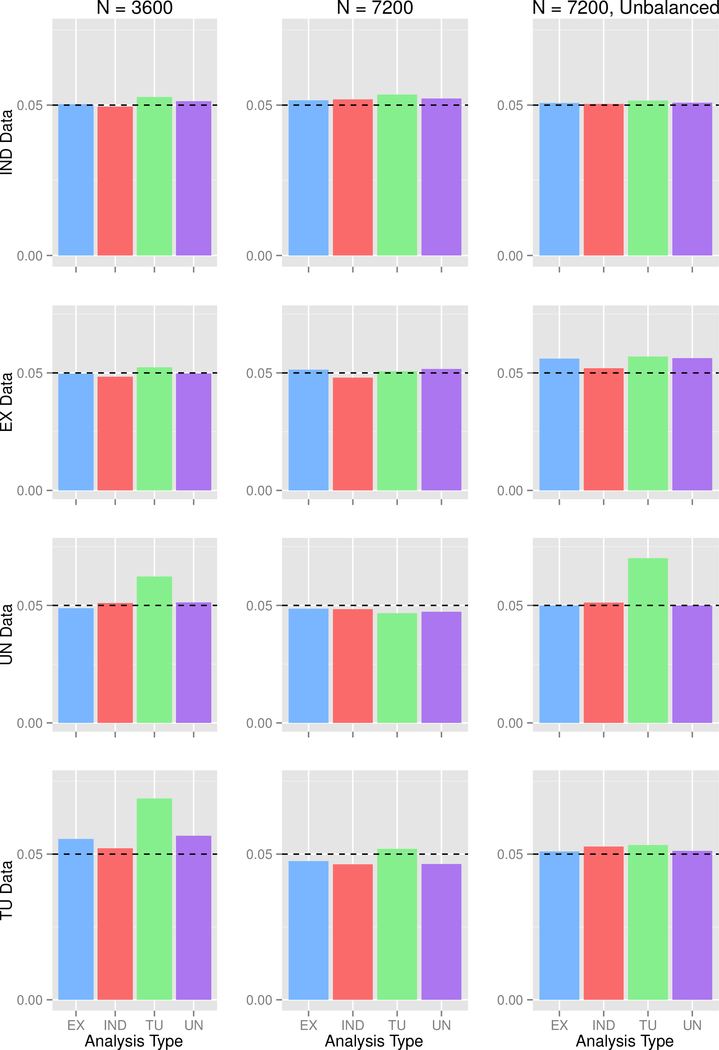

Type I error is shown in Figure 1. For most combinations of sample size and data types there was little distinction between the analysis methods. A notable exception was the TU analysis, which had inflated type I error. Recall that this analysis method allows for the most flexibility in estimation of the correlation structure, but the flexibility comes at the cost of increased numbers of parameters. For 4 member families, there are possible correlation parameters per family; with three family types, the TU analysis requires estimation of 18 pairwise correlations. We also point out that, although a TU working correlation may be desirable from the standpoint of accounting for differences between family types, such as in family studies with MZ and DZ twins, we do not recommend use of this structure due to estimation problems. In a pilot simulation (results not shown), we simulated data sets with 3600 participants total under both null and alternative models with prevalence = 0.05 and MAF = 0.10. We screened results, dropping analyses for which was greater than 5 or was greater than 2. We analyzed all datasets with the IND, EX, UN, and TU working correlation assumptions. Out of 2,000 analyses, 1,221 with the TU analysis failed to meet the inclusion criteria, whereas no other working correlation matrix had estimation problems. So in some situations, particularly with low case prevalence, use of the TU working correlation structure is a poor choice given the instability of the computations. In addition, the results show no indication that a TU offers any advantage over EX or UN working correlation matrices.

Figure 1: Simulation 1 Type I error at α =0.05.

IND = independence, EX = exchangeable, UN = unstructured, TU = totally unstructured. Each row is for the stated data type, while each column is for the stated sample size.

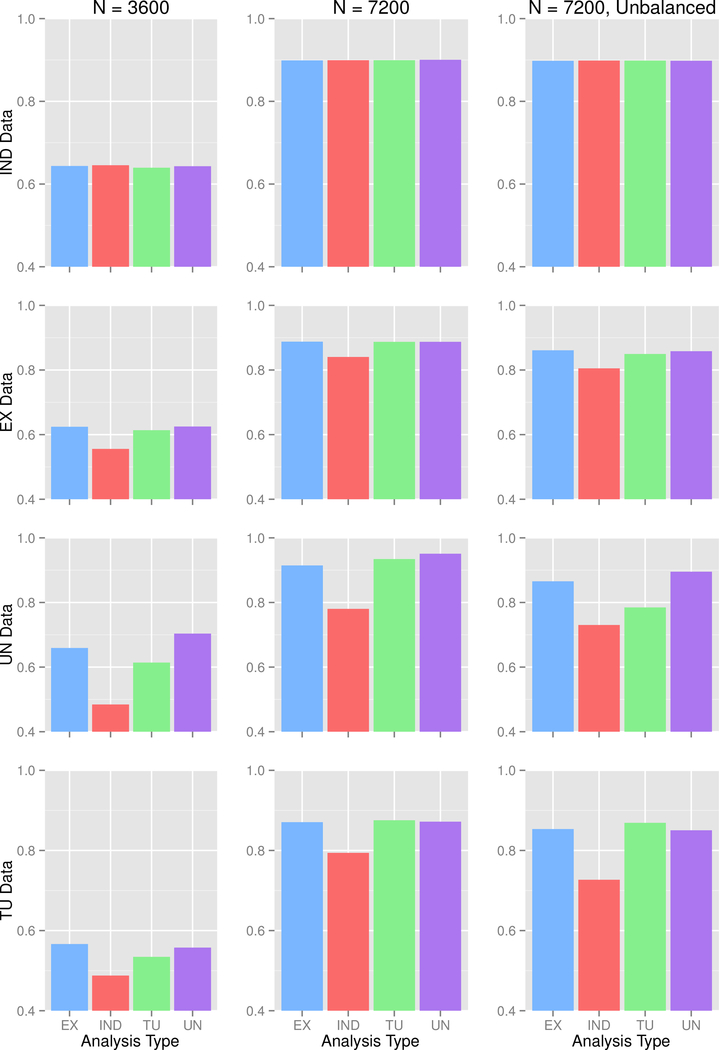

Empirical Power is shown in Figure 2. The most striking finding here is that the IND analysis gives lower power than all other analysis methods, unless the data were generated under an Independence model. Independence working correlation has been recommended for use in GWAS with family data (Chen et al., 2011), and GWAF (Chen and Yang, 2009), a popular GWAS package in R for family data, uses independence as its default analysis method for binary traits. But based on our findings, we cannot recommend the use of an independence working correlation matrix due to its low power. The results of simulation 1 suggest that the use of an exchangeable or unstructured working correlation matrix will perform best regardless of whether the data include different familial structures. The totally unstructured analysis can lead to increased type I error due to the large number of parameters that need to be estimated.

Figure 2: Simulation 1 Empirical Power.

IND = independence, EX = exchangeable, UN = unstructured, TU = totally unstructured. Each row is for the stated data type, while each column is for the stated sample size.

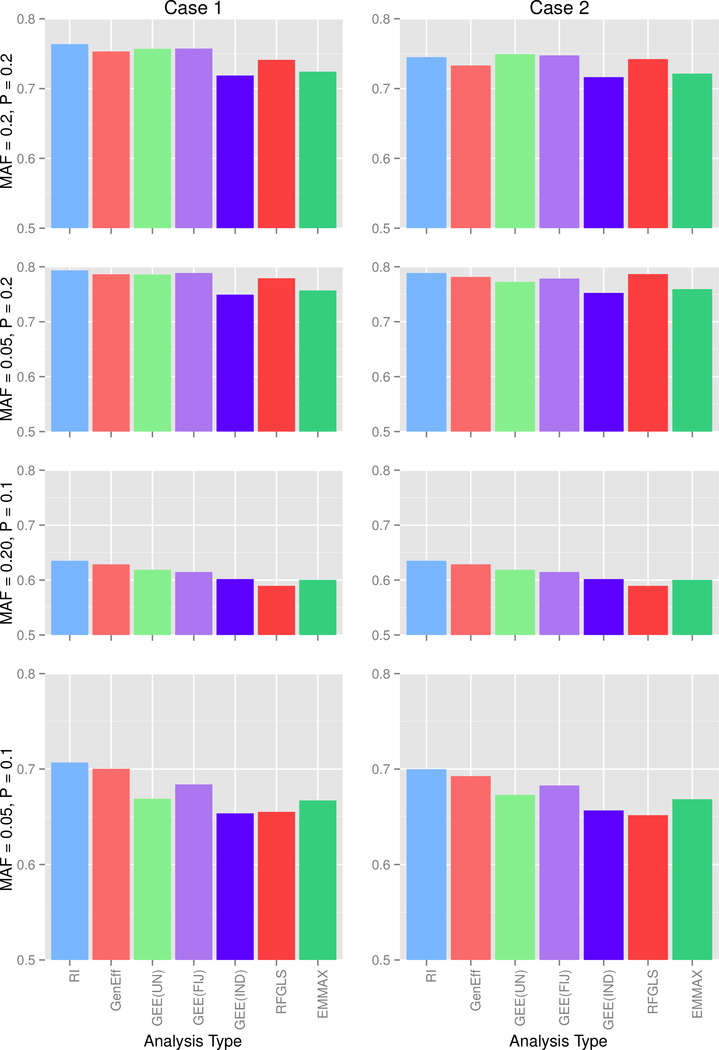

3.2. Simulation 2: comparison of candidate GLMMs, GEE, and GLS

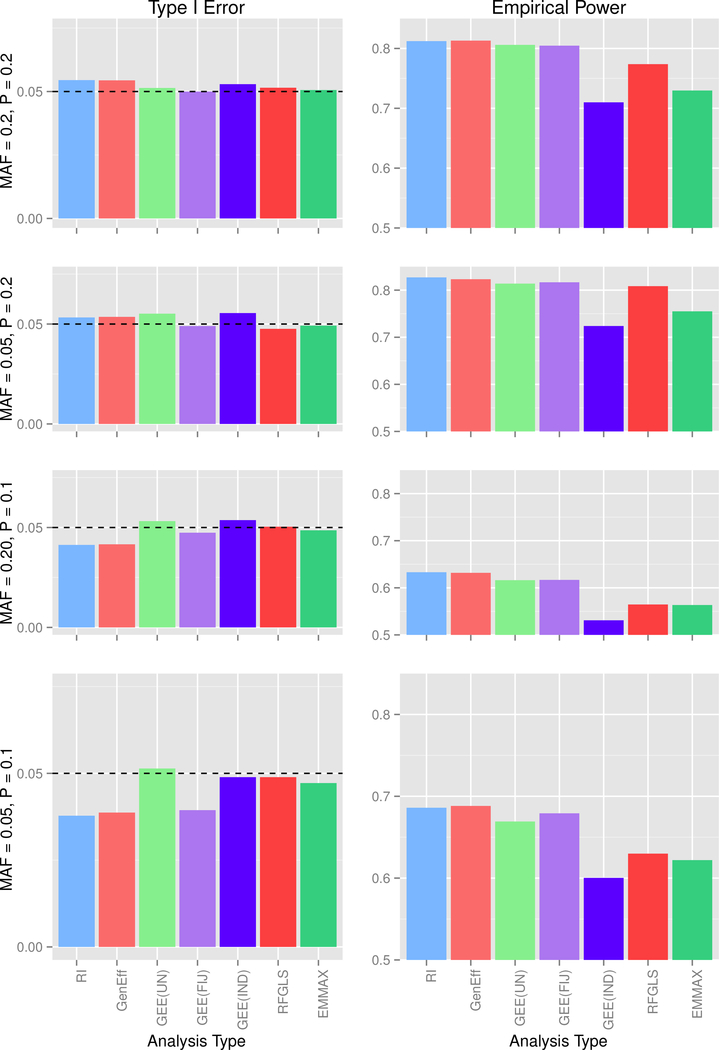

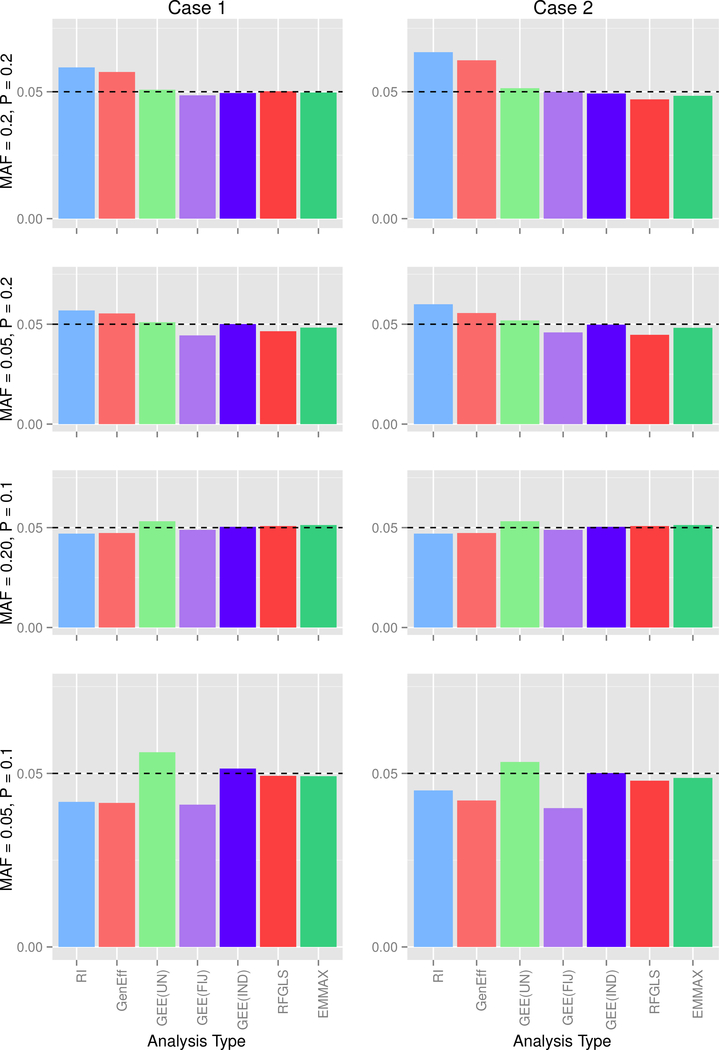

For simulation 2, marginal data were not varied across the three possible covariance scenarios, so for ease presentation, type 1 error and power for data generated from the marginal model are presented in Figure 3. For data generated under the mixed models, type 1 error is presented in Figure 4, and empirical power is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 3: Simulation 2, Marginal Data Type I Error at α = 0.05 and Empirical Power.

Each row corresponds to a MAF-Prevalence combination, while the columns correspond to the 2 covariance conditions. MAF = minor allele frequency, P = trait prevalence; RI = random intercept, GenEff = generation-effects, GEE(UN) = GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and sandwich covariance estimator, GEE(FIJ) = GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and fully-iterated jackknife estimator, GEE(IND) = GEE with independence working correlation matrix.

Figure 4: Simulation 2, Mixed Data Type I Error at α =0.05.

Each row corresponds to a MAF-Prevalence combination, while the columns correspond to the 2 covariance conditions. MAF = minor allele frequency, P = trait prevalence; RI = random intercept, GenEff = generation-effects, GEE(UN) = GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and sandwich covariance estimator, GEE(FIJ) = GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and fully-iterated jackknife estimator, GEE(IND) = GEE with independence working correlation matrix.

Figure 5: Simulation 2, Mixed Data Empirical Power.

Each row corresponds to a MAF-Prevalence combination, while the columns correspond to the 2 covariance conditions. MAF = minor allele frequency, P = trait prevalence; RI = random intercept, GenEff = generation-effects, GEE(UN) = GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and sandwich covariance estimator, GEE(FIJ) = GEE with unstructured working correlation matrix and fully-iterated jackknife estimator, GEE(IND) = GEE with independence working correlation matrix.

The random intercept model showed conservative type 1 error except in the case of high prevalence and high MAF. Results differed little across the two covariance conditions, indicating that, although the analysis does not explicitly model the environmental vs. additive genetic covariance, the model nevertheless is satisfactory in accounting for the dependency structure. Power for the random intercept model was similar to other methods. The generation-effects model performed quite similarly to the random intercept model; this finding is unsurprising given the similarity of the models and because we did not generate any data that would specifically favor this model.

GEE(UN) showed fairly accurate type I error, except in the case of low MAF and low prevalence for mixed data, GEE(FIJ) returned good type 1 error rates for high MAF irrespective of prevalence, but the error rated tended to be conservative for low MAF; for the combination of low MAF and low prevalence, GEE(FIJ) gave type 1 error far below the 0.05 level. In contrast to other simulation findings (Chen et al., 2011), we do not recommend the FIJ for rare genetic variants. Power for GEE methods was comparable to other methods.

As expected in Simulation 1, GEE(IND) maintained acceptable type 1 error but gave significantly lower power than other methods; thus the independence working correlation matrix cannot be recommended for binary traits with family data.

RFGLS and EMMAX actually showed somewhat conservative type I error despite the assumptions of linearity and normally distributed residuals. The most surprising result is that these methods performed quite well, giving somewhat conservative type I error and power comparable to the other methods. We caution that the good performance is likely attributed to the relatively large sample size of 1600 participants total, which makes the model assumption violations less problematic that in a smaller data set. Thus these methods cannot be recommended for small datasets without further investigation.

With the exception of the generation-effects model, all methods are suitable for GWAS in terms of computation time. Mean analysis times are shown in Table I.

Table I:

Mean single-snp analysis time in seconds for all analysis types.

| Analysis | Mean Analysis Time (sec) |

|---|---|

| Random Intercept | 0.639 |

| Generation-Effects | 20.20 |

| GEE (UN) | 0.078 |

| GEE(UN-FIJ) | 1.618 |

| GEE(IND) | 0.066 |

| RFGLS | 0.082 |

| EMMAX | 3.015 |

Values reported were averaged across all simulation conditions. Note that for EMMAX, the value reported represents mean analysis time for 1001 SNPs.

The longer computation times seen with EMMAX is due to the fact that this method was designed to estimate a covariance matrix once, and then use that covariance matrix in the remaining genome-wide scan. But due to constraints of our simulation method, EMMAX needed to estimate the covariance matrix for each simulated data set. Thus in an actual GWAS, the computation time for EMMAX would be significantly reduced. Also note that due to our simulation method, the time reported for EMMAX is for analysis of 1001 SNPs instead of a single SNP. The longer analysis time seen with the generation-effects model is due to the requirement for this methods to fit complicated models with multiple random effects; this method was not designed for GWAS and was included simply as an alternative to models that do not specify a certain structure for random effects to appropriately model the familial dependency. The random intercept model can be fitted using a more recently developed computationally efficient R package named GENESIS (Gogarten et al., 2019) instead of lme4 (Bates, 2010) which would potentially reduce the computational time further.

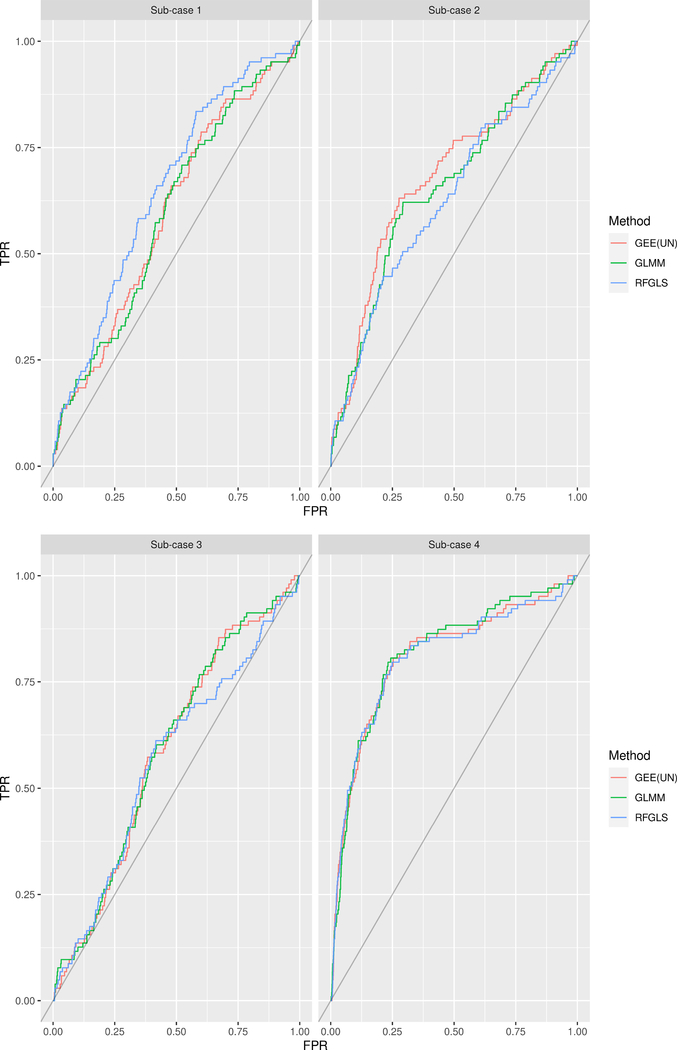

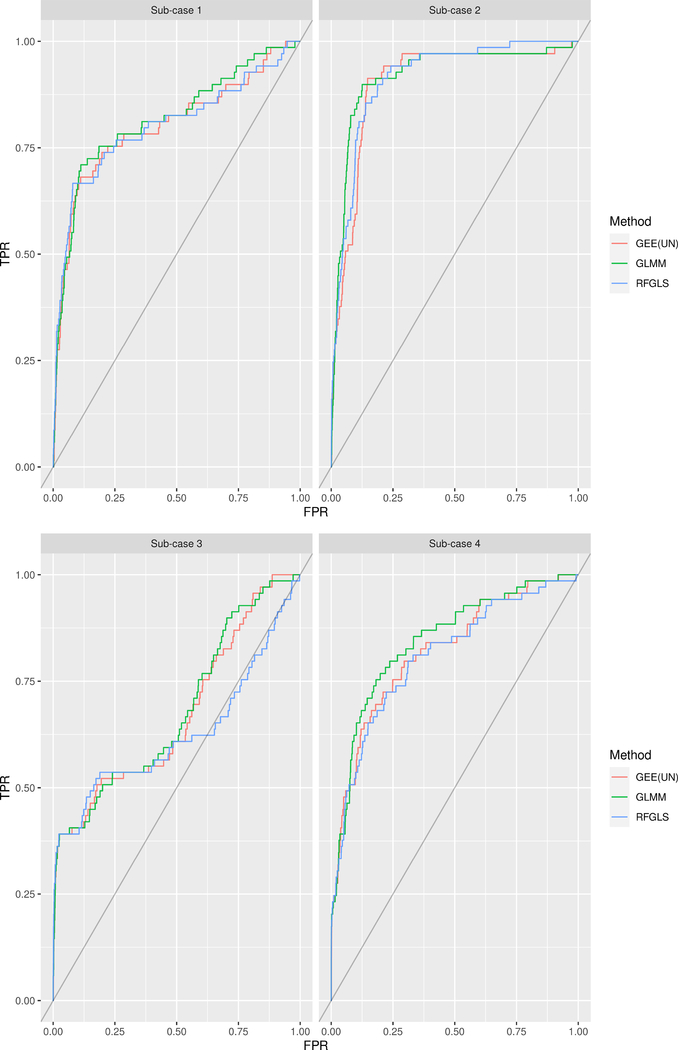

3.3. Simulation 3: comparison of GLMMs, GEE, and GLS using MCTFR data

For all the methods, we display the respective empirical Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves in Figure 6 and 7 and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) values in Table II. We followed the work of Gage et al. (2018) to generate the ROC curves and AUC values. The roc() function in the R package pROC (Robin et al., 2011) was used to construct ROC curves from GWAS results by considering each SNP as an ‘individual’ and coding the randomly selected causative SNPs and the SNPs in high LD with them (r2 LD more than 0.85) as cases in the response, while all the other SNPs were considered controls. −log10(p-value) of each SNP was used as the predictor variable.

Figure 6:

ROC curves of the different methods under Case 1 and different sub-cases from Section (2.4).

Figure 7:

ROC curves of the different methods under Case 2 and different sub-cases from Section (2.4).

Table II:

Minimum of the p – values given by each of the three methods on the alcoholism trait from the MCTFR data

| Case | Sub-case | GEE(UN) | GLMM | RFGLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 59.65 | 59.65 | 65.33 |

| 2 | 68.04 | 65.57 | 62.66 | |

| 3 | 58.74 | 59.08 | 56.71 | |

| 4 | 80.98 | 81.58 | 80.6 | |

| 2 | 1 | 80.11 | 81.58 | 80.08 |

| 2 | 90.16 | 91.79 | 91.34 | |

| 3 | 67.28 | 68.1 | 62.57 | |

| 4 | 82.02 | 84.47 | 80.83 | |

From Figure 6 and 7, we see that most of the times the general GLMM has slightly better ROC curve than the other two methods (with an exception of Sub-case (1) of Case 1). In Case 1, all the 40 selected SNPs were causal and thus individual SNP effect was less than that of Case 2 where only 20 of the selected 40 SNPs were causal. It is the reason why, all the methods have overall better ROC curves in Case (2). From Sub-case 1 to Sub-case 2 and from Sub-case (3) to Sub-case (4), only the individual SNP effect increases by some degree (the value of the parameter a increases) which is why in the top and bottom panel of both Figure Figure 6 and 7, the ROC curves on the right (corresponding to Sub-case (2) and (4)) are much better overall than those on the left (corresponding to Sub-case (1) and (3)). GEE (UN) performs very similar to the GLMM producing very close ROC curves. However, it should be mentioned that we had to exclude the SNPs with MAF < 0.01 since GEE (UN) was not converging for some particular SNPs with low MAF values. The main probable cause of this problem is that there are instances where individuals with the binary trait also possess rare variants. Intuitively, calculating an odds ratio and associated standard error for a contingency table with nearly empty cells leads to unstable parameter estimates and thus, induces problem in algorithm convergence.

RFGLS was expected to perform drastically bad since it makes an oversimplifying assumption by treating the binary trait as continuous. Interestingly enough, it performs quite competently with the other methods. From Table II, we notice that the AUC values are pretty close for GEE (UN) and GLMM with the later having a slight edge in all the cases. RFGLS has less AUC values than GLMM except Sub-case (1) under Case (1). To summarize, in this simualtion exercise involving the real genetic data from the MCTFR study, overall the GLMM performs the best but not by a huge margin.

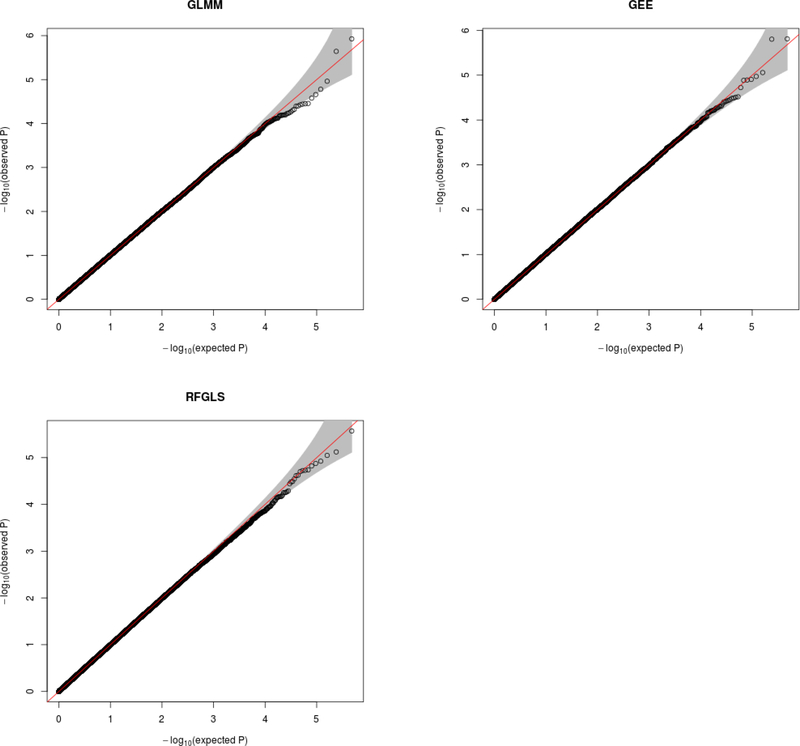

3.4. The MCTFR GWAS of Alcoholism

We analyzed the binary alcoholism trait from MCTFR study (Miller et al., 2012) with three methods: general GLMM, GEE(UN) and RFGLS. This trait was a lifetime diagnosis of Alcohol Dependence (i.e., meeting diagnostic criteria any time in the participant’s lifetime), which was assessed using structured interviews [the Substance Abuse Module (Robins et al., 1987) a supplement to the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins et al., 1988). Diagnoses were made according to DSM-III-R criteria because it was the diagnostic system in use when data collection began. Both definite (meeting all DSM-III-R criteria) and probable (missing one symptom) diagnoses were used in order to account for the fact that some people may forget symptoms when reporting on symptoms that may have occurred a number of years before. One thing that is important to note is that this is a clinical diagnosis of alcoholism. It does not deal with how many drinks a person has but rather whether their drinking is causing them problems in their daily life (e.g., loss of employment).

The data consisted of 5,352 white subjects. In total there were 2214 families that included either 2, 3, or 4 members, or independent observations. There were 5 family types analyzed: MZ twin families, DZ twin families, adoptive offspring families, non-twin biological-offspring families, and mixed families with one biological offspring and one adopted offspring. There were 527,829 many single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers genotyped using Illumina’s Human660W-Quad array (Miller et al., 2012). The prevalence of the alcoholism trait was 27.2%. We only considered the SNPs with Minor MAF more than 0.01. Table III lists the SNPs with the minimum p − values (bold ones) given by each of the three methods. For each SNP, all the three p−values are displayed.

Table III:

Minimum of the p–values given by each of the three methods on the alcoholism trait from the MCTFR data

| CHR | SNP | MAF | GLMM | GEE(UN) | RFGLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. p – value by GLMM | 2 | rs11686968 | 0.1536 | 2.426551e-06 | 1.5767496e-06 | 2.5554828e-04 |

| Min. p – value by GEE(UN) | 2 | rs2081364 | 0.2266 | 3.01181e-06 | 1.5494263e-06 | 3.30237e-05 |

| Min. p – value by RFGLS | 6 | rs1491074 | 0.3132 | 7.080792e-05 | 3.531382e-05 | 2.69656e-06 |

The normal quantile-quantile plots in Figure 8 show that the smallest p-values are within the interval of values expected under the null distribution. Thus we cannot claim genome-wide significance. However, the most surprising result is that RFGLS appears to be a reasonable choice for GWAS of a binary trait. It shows good adherence to the expected null distribution and good genomic control value, defined as the median observed test statistic divided by the median expected test statistic under the null χ2 distribution. The median genomic control values of general GLMM, GEE(UN) and RFGLS were respectively 0.968,1.01 and 1.001 which makes us conclude that GLMM is slightly conservative whereas, GEE(UN) is slightly inflated. Spearman’s correlation between the p − values from all the three methods are listed in Table IV.

Figure 8:

Normal Quantile-Quantile Plots for the general GLMM, GEE(UN) and RFGLS Alcoholism GWAS.

Table IV:

Spearman’s correlation between the p – values obtained using the methods: general GLMM, GEE(UN) and RFGLS on the alcoholism trait from the MCTFR data

| GLMM | GEE(UN) | RFGLS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLMM | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.67 |

| GEE(UN) | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.66 |

| RFGLS | 0.67 | 0.66 | 1.00 |

It is interesting to see that GLMM and GEE(UN) performed almost equivalently. It suggests that taking into account different familial relationships, as done in GLMM, had little to no effect on the genome-wide association inference compared to the case of considering a same unstructured correlation in different families regardless of their types, as done in GEE(UN). Also, the correlation between RFGLS p − values and those of the rest were around 0.66 which indicates good agreement between the methods.

For GEE(UN) and RFGLS we respectively used the R packages geepack (Halekoh et al., 2006) and RFGLS (Li et al., 2011). For general GLMM we used two R packages, GMMAT (Chen, 2019) and GENESIS (Gogarten et al., 2019). We noticed that the parameter τ1 in general GLMM which corresponds to the additive genetic variance came out to be almost 0, an observation similar to that of Park et al. (2018). It means that the general GLMM in this case is equivalent to the simple random intercept model. One may get tempted to claim that alcohol dependence is majorly due to the shared environmental effect but it would be far-fetched given that alcohol use disorder is known to be quite heritable (Verhulst et al., 2015) and also, a few recent GWASs on alcohol consumption like (Sun et al., 2019; Kranzler et al., 2019) have detected several significant loci. We strongly believe that this is due to confounding (Lee et al., 2010) which means that the parameters τ1 and τ2 are not separately estimable. It should also be kept in mind that PQL estimates for variance components, as used in GMMAT and GENESIS, are biased, especially for correlated binary data (Breslow and Clayton, 1993). Using corrected PQL or second-order Laplace methods as discussed by (Breslow and Lin, 1995) and (Lin and Breslow, 1996), though neither is yet available in GMMAT or GENESIS. Therefore, there can be estimation errors while fitting the general GLMM for binary data using these standard R packages. From a computational perspective, GENESIS uses the same algorithm as GMMAT but is much faster. But in our simulation studies and in a different analysis with the popular UKBiobank data (Allen et al., 2014), we have noticed (not reported in this paper) that with a substantially large number of individuals (around 35000), GENESIS too struggles with fitting the general GLMM.

4. Discussion

We conducted simulation studies comparing candidate GLMM methods, RFGLS, EMMAX and different GEE methods. GLMM methods showed slightly conservative type 1 error in most of the cases but maintained power similar to the other methods. We examined selection of the working correlation matrix in GEE methods and found that, despite differences in the true underlying structure, an EX (exchangeable) or UN (unstructured) analysis is satisfactory, and there is no benefit to be gained from a TU (totally unstructured) working correlation matrix. We found that an IND (independent) analysis maintains correct type 1 error but has low power compared to other methods. We recommend use of an exchangeable or unstructured correlation matrix regardless of the suspected true underlying dependency. Overall, the GEE methods tend to give somewhat inflated type 1 error with the sandwich covariance estimator and conservative type 1 error with the jackknife estimator. RFGLS and EMMAX showed good type 1 error despite the fact that the model assumptions are violated by binary data. Both methods showed good power. Note that we included both age and sex effects under both null and alternative models; our data thus had a wide range of fitted probabilities, ensuring violation of the assumption of homoscedasticity. Thus the good performance of RFGLS and EMMAX cannot be explained as occurring due to lack of non-constant variance.

In our simulation exercises with real genetic data from the MCTFR study, we found out that the general GLMM performed the best. But GEE (UN) also showed pretty close ROC curves and similar AUC values in most of the cases. Once again, RFGLS which was expected to perform very poorly since it treats the binary trait as continuous, performed respectably. It shall be noted that as an algorithm, RFGLS is the fastest among the three methods. So, it may make sense to use it instead of GLMM or GEE (UN) when the study size is much larger. Also, we had to exclude the SNPs with MAF < 0.01 since GEE (UN) was not converging for some particular SNPs with low MAF values. The main probable cause of this problem is that there are instances where individuals with the binary trait also possess rare variants. Intuitively, calculating an odds ratio and associated standard error for a contingency table with nearly empty cells leads to unstable parameter estimates, and this issue is not present with GLS methods and can serve as one more reason to prefer RFGLS over GEE (UN).

In the MCTFR alcoholism GWAS, we saw that general GLMM (that turned out to be equivalent to a simple random intercept model) and GEE(UN) performed very similarly (Spearman’s correlation between the p−values was 0.96). However, GLMM was slightly conservative (with median genomic control value 0.968) and GEE(UN) demonstrated slight inflation in type 1 error (with median genomic control value 1.01). RFGLS again showed good performance and acceptable median genomic control values, indicating that this indeed may be a strong method for both quantitative traits and binary traits. RFGLS and EMMAX are similar methods. Both assume an identity link and were designed primary for use with quantitative traits. Although we know of no studies using RFGLS for GWAS with binary traits, EMMAX has been used successfully in GWAS (Kang et al., 2010; Allen-Brady et al., 2011; Teerlink et al., 2012), and the method performs well under simulated case-control data (Wu et al., 2011; Price et al., 2010). And as noted, RFGLS and EMMAX use somewhat similar methodology, so our finding that RFGLS is suitable for GWAS with binary data is not entirely unprecedented.

For GWAS with binary traits, we conclude that a simple random intercept model can safely be used in most of the cases. Fitting the general GLMM takes the most mount of time and can be computationally infeasible on a large scale study. Also, the variance parameter estimates under the general GLMM may turn out to be biased in some cases as pointed out by few other researchers (Breslow and Clayton, 1993; Park et al., 2018). Thus, our recommendation is to use GEE(UN) for common variants when the prevalence is not low. When the prevalence is low or when the GWAS contains many rare variants or the data-set is huge, RFGLS and EMMAX can be considered as viable alternatives.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grant R01-DA033958 and R21-DA046188 (PI: Saonli Basu).The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- Agresti A and Kateri M (2011). Categorical data analysis. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Allen NE, Sudlow C, Peakman T, Collins R, et al. (2014). Uk biobank data: come and get it. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Allen-Brady K, Cannon-Albright L, Farnham JM, Teerlink C, Vierhout ME, van Kempen LC, Kluivers KB, and Norton PA (2011). Identification of six loci associated with pelvic organ prolapse using genome-wide association analysis. Obstetrics and gynecology 118, 1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DM (2010). lme4: Mixed-effects modeling with r.

- Benyamin B, Visscher PM, and McRae AF (2009). Family-based genome-wide association studies. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Breslow NE and Clayton DG (1993). Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. Journal of the American statistical Association 88, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow NE and Lin X (1995). Bias correction in generalised linear mixed models with a single component of dispersion. Biometrika 82, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H (2019). Gmmat: Generalized linear mixed model association tests version 1.1. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen M-H, Liu X, Wei F, Larson MG, Fox CS, Vasan RS, and Yang Q (2011). A comparison of strategies for analyzing dichotomous outcomes in genome-wide association studies with general pedigrees. Genetic epidemiology 35, 650–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M-H and Yang Q (2009). Gwaf: an r package for genome-wide association analyses with family data. Bioinformatics 26, 580–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, Steinhart AH, Abraham C, Regueiro M, Griffiths A, et al. (2006). A genome-wide association study identifies il23r as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. science 314, 1461–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eu-Ahsunthornwattana J, Miller EN, Fakiola M, Jeronimo SM, Blackwell JM, Cordell HJ, 2, W. T. C. C. C., et al. (2014). Comparison of methods to account for relatedness in genome-wide association studies with family-based data. PLoS genetics 10, e1004445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage JL, De Leon N, and Clayton MK (2018). Comparing genome-wide association study results from different measurements of an underlying phenotype. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 8, 3715–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogarten SM, Sofer T, Chen H, Yu C, Brody JA, Thornton TA, Rice KM, and Conomos MP (2019). Genetic association testing using the genesis r/bioconductor package. Bioinformatics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Hackett R, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Parkin M, Gates C, et al. (2008). Genetic variants near tnfaip3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics 40, 1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J, et al. (2006). The r package geepack for generalized estimating equations. Journal of Statistical Software 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin JW and Hilbe JM (2012). Generalized estimating equations. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Harville DA and Mee RW (1984). A mixed-model procedure for analyzing ordered categorical data. Biometrics pages 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kang HM, Sul JH, Service SK, Zaitlen NA, Kong S. y., Freimer NB, Sabatti C, Eskin E, et al. (2010). Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nature genetics 42, 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Zhou H, Kember RL, Smith RV, Justice AC, Damrauer S, Tsao PS, Klarin D, Baras A, Reid J, et al. (2019). Genome-wide association study of alcohol consumption and use disorder in 274,424 individuals from multiple populations. Nature communications 10, 1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, and van der Werf JH (2010). Using the realized relationship matrix to disentangle confounding factors for the estimation of genetic variance components of complex traits. Genetics Selection Evolution 42, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Wray NR, Goddard ME, and Visscher PM (2011). Estimating missing heritability for disease from genome-wide association studies. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88, 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Basu S, Miller MB, Iacono WG, and McGue M (2011). A rapid generalized least squares model for a genome-wide quantitative trait association analysis in families. Human heredity 71, 67–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K-Y and Zeger SL (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lin X and Breslow NE (1996). Bias correction in generalized linear mixed models with multiple components of dispersion. Journal of the American Statistical Association 91, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz SR, Dear KB, and Zhao L (1994). Jackknife estimators of variance for parameter estimates from estimating equations with applications to clustered survival data. Biometrics pages 842–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L and Birkes D (2013). Simulating dependent discrete data. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 83, 677–691. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Basu S, Cunningham J, Eskin E, Malone SM, Oetting WS, Schork N, Sul JH, Iacono WG, and McGue M (2012). The minnesota center for twin and family research genome-wide association study. Twin research and human genetics 15, 767–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik MC (1988). Repeated measurement analysis for nonnormal data in small samples. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 17, 1155–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Park JY, Wu C, Basu S, McGue M, and Pan W (2018). Adaptive snp-set association testing in generalized linear mixed models with application to family studies. Behavior genetics 48, 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Zaitlen NA, Reich D, and Patterson N (2010). New approaches to population stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics 11, 459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, and Gjessing HK (2008). Biometrical modeling of twin and family data using standard mixed model software. Biometrics 64, 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez J-C, and Müller M (2011). proc: an open-source package for r and s+ to analyze and compare roc curves. BMC bioinformatics 12, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Babor T, and Cottler L (1987). Composite international diagnostic interview: expanded substance abuse module. St. Louis: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, et al. (1988). The composite international diagnostic interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of general psychiatry 45, 1069–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Chang S, Wang F, Sun H, Ni Z, Yue W, Zhou H, Gelernter J, Malison RT, Kalayasiri R, et al. (2019). Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence in male han chinese and cross-ethnic polygenic risk score comparison. Translational psychiatry 9, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teerlink C, Farnham J, Allen-Brady K, Camp NJ, Thomas A, Leachman S, and Cannon-Albright L (2012). A unique genome-wide association analysis in extended utah high-risk pedigrees identifies a novel melanoma risk variant on chromosome arm 10q. Human genetics 131, 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst B, Neale MC, and Kendler KS (2015). The heritability of alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological medicine 45, 1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, DeWan A, Hoh J, and Wang Z (2011). A comparison of association methods correcting for population stratification in case–control studies. Annals of human genetics 75, 418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Burbridge C, Shi J, Liu J, and Kusalik A (2018). Comparing four genome-wide association study (gwas) programs with varied input data quantity. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), pages 1802–1809. IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, and Visscher PM (2011). Gcta: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 88, 76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X (2013). A tutorial for the r package snprelate. University of Washington, Washington, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X and Stephens M (2012). Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nature genetics 44, 821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]