Abstract

With advancement, prompt use, and increasing accessibility of antiretroviral therapy, people with HIV are living longer and have comparable lifespans to those negative for HIV. However, people living with HIV experience tradeoffs with quality of life often developing age-associated co-morbid conditions such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, or neurodegeneration due to chronic immune activation and inflammation. This creates a discrepancy in chronological and physiological age, with HIV-infected individuals appearing older than they are, and in some contexts ART-associated toxicity exacerbates this gap. The complexity of the accelerated aging process in the context of HIV-infection highlights the need for greater understanding of biomarkers involved. In this review, we discuss markers identified in different anatomical sites of the body including periphery, brain, and gut, as well as markers related to DNA that may serve as reliable predictors of accelerated aging in HIV infected individuals as it relates to inflammatory state and immune activation.

Keywords: HIV, immune aging, inflammatory markers, activation markers, combined antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Aging is a natural process involving decline in physiological integrity and reduced organ function (1). These features can be manifested in the form of chronic degenerative diseases, cancers, inflammation, and cellular senescence. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection shares common factors associated with conditions observed in older, uninfected people. Chronic HIV infection in the setting of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) is commonly associated with inflammaging, low-grade inflammation, a primary contributor to age-related conditions such as increased vulnerability to infections, and development of age associated co-morbid conditions including cancers, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and neurodegenerative diseases (2, 3). During aging, inflammation is largely driven by cellular senescence, an increase in cellular debris, and microbial translocation (4). These same factors contribute to inflammation in HIV infection. Additionally, HIV viral proteins including gp120, Tat, Vpr, and Nef are able to induce inflammatory signaling independent of these processes in both lymphocytes and myeloid cells (5, 6).

People with HIV (PLWH) are living longer due to widespread use and advancement of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART); the life expectancy of cART-treated HIV-infected individuals was merely 55 years in 1996 and now it mirrors that of the general population (7–9). The advancement of cART dramatically decreases systemic inflammation in HIV-infected people which results in a delay in progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (10). However, while PLWH are reaching older ages, they are not aging normally. Despite cART, PLWH still experience comorbidities, chronic inflammation, and symptoms of premature aging. For example, senescent T cells, characterized by a curbed proliferative state often triggered by stresses such as DNA damage, telomere shortening, or presence of inflammatory cytokines, can accumulate in tissues as they age. PLWH are susceptible to developing other conditions indicative of premature aging, including decline in integrity of neurological function, or HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Even HIV-infected individuals receiving cART are likely to exhibit mild forms of neurological impairment related to HAND (11). Aging is a complex process that involves and affects a multitude of organs creating a need for greater understanding of the biomarkers involved, specifically within the context of HIV. The purpose of this review is to highlight similarities between HIV-associated premature aging and chronological aging by examining biomarkers that define inflammatory state in PLWH, a phenotype for accelerated aging. These biomarkers originate from diverse pathways making it difficult to propose a single mechanism for treatment, however, they offer a holistic understanding of inflammation in PLWH on cART and may present new avenues for therapeutics.

Immunosenescence and Genetic Aging

Lymphocytes

In PLWH, systemic activation of the immune system and virus-induced cell death drive CD4+ T-cell depletion and CD8+ T-cell expansion. Irrespective of active cART, chronic immune activation and inflammation persist which can lead to non-AIDS related conditions (12). Elevated levels of CD38 and HLA-DR co-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells reflect increased immune activation (13, 14). Comparing parameters for immune activation and aging, similarities include an increase in CD28- T cells, greater levels of activation markers such as CD38/HLA-DR, and a transition of naïve T-cells to memory cells (15). These features contribute to immunosenescence: the reduced and imbalanced effectiveness of the adaptive and innate immune response induced by the aging process (16). In elderly individuals, there is a smaller ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells due to decreased naïve T-cell levels, greater T-cell activation, and higher levels of inflammatory markers (17). During HIV infection, adipose tissue becomes a site for accumulation of latently-infected CD4+ T cells and activation of CD8+ T cells (18). A low CD4/CD8 ratio is associated with chronic inflammation and can also serve as a predictor of decreased subcutaneous fat loss in the cART-treated HIV-infected population; similarly, with chronological aging, there is increased inflammation and body fat redistribution which have been associated with metabolic complications (19). Another marker, IP-10, is associated with aging in HIV. Upon HIV-infection, plasma levels of pro-inflammatory chemokine IP-10 are upregulated and inversely related to CD4+ T cell counts ( Figure 1 ) (20). Elevated levels of IP-10 have been shown to suppress T cell and NK cell function, while simultaneously promoting HIV replication (21–23). Furthermore, elevated levels of IP-10 are associated with aging such that after viral suppression with cART, older individuals are more likely to maintain higher IP-10 plasma levels (24). These findings are consistent with the claim that chronic immune activation induces premature aging.

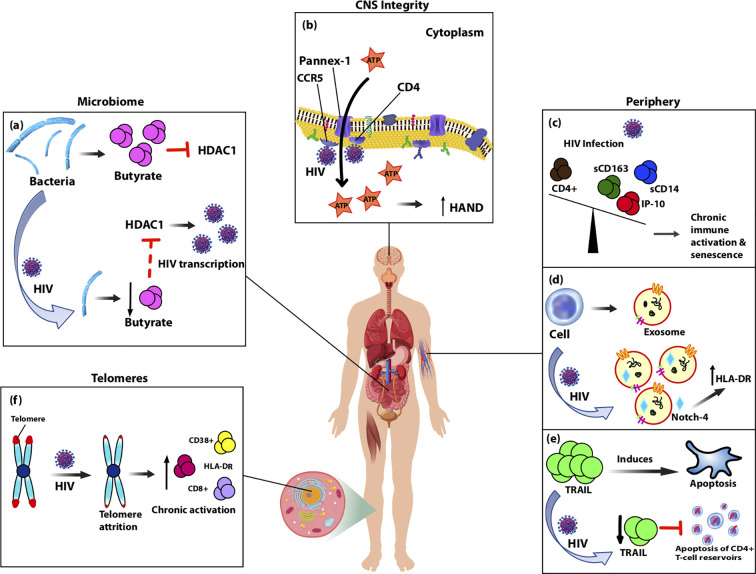

Figure 1.

Diagram showing biomarkers isolated from various anatomical sites of the body that are altered by HIV-infection and likely contribute to accelerated aging observed in people living with HIV (PLWH) on cART through chronic immune activation and inflammation. (A) Typically, gut-associated bacteria, Firmicutes, produces butyrate which inhibits HDAC1. With normal aging or HIV-infection, Firmicutes is replaced causing reduced production of butyrate and consequently increased expression of HDAC1, which acts to increase HIV transcription. (B) Pannex-1 channels, usually closed, open upon binding of HIV to receptors CD4 and co-receptor CCR5, which causes release of ATP, an inflammatory signal. Increased levels of ATP in circulation were correlated with cognitive impairment and thus predictive of CNS compromise. (C) During HIV-infection plasma levels of monocyte activation markers sCD163 and sCD14, as well as pro-inflammatory marker IP-10 are elevated and inversely related with CD4+ T-cell depletion. Over-expression of these markers in the periphery leads to accelerated aging of T cells and senescence. (D) Upon HIV-infection, secretion of exosomes increases along with oxidative stress markers, and HIV-induced chronic activation alters the contents of exosomes. Notch-4 exosomal levels are elevated and correlated with other activation markers, HLA-DR. (E) HIV-infection reduces expression of circulating TRAIL, an apoptosis-inducing protein, which theoretically in turn limits apoptosis of CD4+ T-cell reservoirs allowing for persistent immune activation and inflammation. (F) Telomeres undergo attrition after HIV-infection due to reduced T-cell proliferation and this is associated with cellular senescence markers CD8+, HLA-DR, and CD38+.

Telomeres and Senescence

Age-associated decline in function is characterized by telomere shortening, increased level of NK cells, high percentage of activated CD45RO+CD95+ T cells, greater levels of CD8+CD28-CD57+ senescent T cells, and increase in PD-1+ functionally exhaustive cells (25–28). These levels are reliable predictors of aging phenotypes, including immunosenescence. Utilizing animal models can strengthen our understanding of immunosenescence in HIV infection. In a study using Chinese rhesus macaques, SIV infection caused pathogenesis and immunosenescence, but aged-macaques showed accelerated SIV disease progression including more rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells leading to increased levels of lymphocyte exhaustion relative to younger SIV-infected macaques (29). In another study, SIV-infected macaques had higher expression levels of markers for senescence like p53 and p16 in their subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue ( Table 1 ). CD4+ T cells in the human immune system are long-lived and subject to genomic mutations, damage, and replicative pressures, making them susceptible to age-associated irregularities (95). With aging, there is a slow decline in T cell capacity to proliferate which is correlated with telomere attrition, a phenotype of cellular senescence (96). Telomere shortening is an indicator of inflammaging. In managing HIV-infection, ART restores CD4+ T cell counts, though HIV-infected individuals maintain increased levels of immune activation, shown by higher frequencies of CD38+HLA-DR+CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, and these markers are associated with shorter telomeres and transitively, immunosenescence ( Figure 1 ) (97). One mechanism of telomere damage may be attributed to an inefficient DNA repair mechanism that compromises telomere integrity driven by excessive proliferative turnover rate in these long-lived cells. However, HIV-infected individuals on cART exhibit telomeric DNA damage that is not addressed because of an Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated gene deficiency which leads to age-associated phenotypes such as telomere shortening, CD4+ T cell senescence, and apoptosis (98). Shorter telomeres have also been associated with inflammatory markers including CXCL1, TGF-α, and IL10RA (42). HIV-infection leads to establishment of viral reservoirs in various anatomical sites of the body, primarily in long-lived CD4+ T cells which persist even in the presence of ART. HIV appears to stimulate telomere elongation in latently infected memory CD4+ T cells which are vulnerable to BRAC019, a telomere-targeting drug that causes uncapping and apoptosis (99).

Table 1.

Effects of natural versus HIV-induced aging on soluble biomarkers and known age-associated diseases*.

| Biomarker | Function | System | Effect of HIV infection | Effect of Aging | Age-associated diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sCD14 | Myeloid differentiation marker on monocytes/macrophages; Marker of monocyte activation in HIV |

Periphery | Increased | Increased | Cardiovascular Disease | (30–32) |

| sCD163 | Shed by CD163 scavenger receptor specific to monocytes/macrophages; Marker of monocyte activation in HIV |

Periphery | Increased | Increased | Cardiovascular Disease, Liver Disease | (33–35) |

| IP-10 | Pro-inflammatory chemokine involved in T-cell generation and trafficking | Periphery | Increased | Increased | Rheumatoid Arthritis | (36, 37) |

| NDE | Delivers signaling molecules between cells and reflects host cell proteins and nucleic acids | Brain – isolated from blood | Increased | ? | Alzheimer’s Disease | (38, 39) |

| Notch-4 | Regulates cell-fate determination, differentiation, proliferation, apoptotic programs | Plasma exosome contents | Increased | Decreased | Alzheimer’s Disease | (40, 41) |

| SLAMF1 | Glycoprotein that delivers downstream signals directing innate and adaptive immune response; Phagocytic properties | Periphery | Increased | Increased | Rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s Disease | (42–45) |

| CCL23 | Hematopoiesis inhibitor that directs migration of monocytes, macrophages, activated T-lymphocytes | Periphery | Increased | ? | Rheumatoid arthritis, human brain injury, Myeloid leukemia | (42, 46–49) |

| NT3 | Supports differentiation of neurons to promote growth | Periphery | Decreased | Decreased | Colorectal Cancer; Neurocognitive decline | (42, 50–52) |

| TRAIL | Induces apoptosis of tumor/infected cells; promotes CD4+ T-cell death in HIV | Periphery | Decreased | Increased | Alzheimer’s Disease | (42, 53–55) |

| p53 | Tumor suppressor, DNA repair, cell cycle regulation | Periphery | Increased | Increased | Cancer | (56, 57) |

| p16 | Tumor suppressor, cell cycle regulation, neurogenesis regulation | Periphery, CNS | Increased | Increased | Cancer, neurodegeneration | (56–58) |

| Neopterin | Pteridine metabolite produced primarily during Th1-type | CNS, periphery | Increased | Increased | Chronic inflammation, neurocognitive decline | (59–61) |

| NFL | Maintains neuronal shape, including axonal diameter | CNS | Increased | Increased | Neurodegeneration (Specifically axon injury) | (62–64) |

| sCD30 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor | CNS, Periphery | Increased | Increased | Cancer, Inflammation, neurodegeneration | (65, 66) |

| Serum ATP | Energy transfer, signaling, neurotransmitter | From CNS to periphery | Case-dependent increase | Case-dependent increase | Neurodegeneration | (67, 68) |

| S100B | Cell cycle regulation, neuron survival, inflammatory response | CNS, gut, periphery | Increased | Variable (“Dose dependent”) | Neurodegeneration, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease | (69–71) |

| Grey/White Matter Volume | Processing, integrating, and coordinating information | CNS | Decreased | Decreased | Neurodegeneration | (72–75) |

| Ventricle Volume | Storage and transport CSF | CNS | Increased | Increased | Neurodegeneration | (73, 74) |

| Choline | Cell membrane degradation and inflammation | CNS | Increased | Increased | Neurodegeneration | (76–80) |

| Myo-Inositol | Gliosis and neuroinflammation | CNS | Increased | Increased | Neurodegeneration | (76, 78, 80, 81) |

| N-acetyl Aspartate | Neuron viability and integrity | CNS | Decreased | Decreased | Neurodegeneration | (76–81) |

| Mean Diffusivity | Measure of water flow and loss of myelin | CNS | Increased | Increased | Neurodegeneration | (82–88) |

| Fractional Anisotropy | Measure of myelin structure and axon integrity | CNS | Decreased | Decreased | Neurodegeneration | (83, 84, 88, 89) |

| Ratio of Firmicutes to Bacterioidetes | Butyrate production | Micro-biome | Decreased | Decreased | Inflammation, Neurodegeneration, | (90–94) |

*Many of these biomarkers may be used to track HIV pathogenesis as well as changes in inflammatory state with chronological aging,

Epigenetic

Epigenetics refers to mechanisms regulating chromatin structure which has implications in gene expression and genome stability. Epigenetic alterations are indicative of the aging process due to chromatin remodeling and accumulation of DNA mutations. These changes stimulate protective actions such as DNA methylation (100). PLWH exhibited accelerated epigenetic aging of 7.4 years in brain tissue, 5.2 years in periphery, and virally-suppressed PLWH had a 19% increased risk of mortality compared to healthy controls (101, 102). It has been suggested that HIV-mediated chronic inflammation may be an underlying mechanism contributing to epigenetic aging (103–105). Another study suggested inflammation-related SNPs of these pro-inflammatory cytokines are risk factors for accelerated aging in PLWH. While the TNF-α (TNF-α-308G>A) genotype was not associated with epigenetic aging, IL-6 (IL-6-174G>C) C allele carriers and IL-10 (IL-10-592C>A) CC homozygotes showed significantly greater epigenetic aging compared to other genotypes in PLWH (106). Thus, these SNPs may offer unique insights into HIV aging and the accompanying pathophysiological changes.

Cytokines, Chemokines, and Inflammaging

While cART effectively establishes viral suppression, there is still a heightened pro-inflammatory state in treated individuals, which induces chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation promoting pathophysiological age-associated changes. There are well-documented markers of inflammation associated with HIV-infection such as cytokines including IP-10, interferon-α, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-15 (107). A recent study investigated a large panel of inflammatory soluble biomarkers in plasma to understand the risk of age-associated diseases in PLWH ( Table 1 ). Reportedly, compared to healthy controls, PLWH on long-term cART had higher levels of CST5, 4E-BP1, SLAMF1, CCL23, MMP1, ADA, and CD8A and lower levels of NT3, TRAIL, and sCD5 in plasma (42). Additionally, peripheral inflammatory cytokines (d-dimer, IL-6, MCP-1/CCL2, sCD14, and TNF-α) in HIV-infection have been correlated with impaired complex motor performance, though not a HAND-specific biomarker (108). Furthermore, it has been suggested that these proteins are associated with early stages of age-related diseases ( Table 1 ). For example, TNF-related-apoptosis-inducing-ligand (TRAIL) selectively induces apoptosis of tumor cells or infected cells. During HIV-infection, TRAIL could promote CD4+ T-cell death, which fuels interest in its use as a unique method of targeting latent HIV-1 CD4+ T-cells (53–55). Decreased levels of TRAIL observed in PLWH on long-term ART may impede eradication of the latent HIV-1 reservoir ( Figure 1 ).

Monocytes and Myeloid Soluble Markers

Monocyte activation is of increasing interest as a mediator of non-AIDS related morbidity and mortality, and circulating biomarkers in plasma including well-characterized sCD14 and sCD163 are used to study monocyte activation ( Table 1 ). CD14 is a co-receptor for LPS found predominantly on the monocytic-macrophage cell lineage, which upon stimulation, releases sCD14, a sign of monocyte activation. While LPS can generate this response, other TLR ligands such as flagellin or CpG oligodeoxynucleotides or inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 could generate the same, suggesting that sCD14 is a nonspecific marker of monocyte activation (30). Similarly, CD163 has restricted expression to monocytes and macrophages (33). LPS acts as a down-regulator of CD163, while IL-6 acts as a potent stimulator, resulting in shedding of sCD163 (109). PLWH have higher plasma levels of sCD14 and sCD163 and these markers are independent predictors of mortality in HIV ( Figure 1 ) (110, 111). Measurement of immune activation markers in HIV-infected individuals on long-term cART showed sCD14 and sCD163 levels were persistently elevated in treated HIV-infected patients compared to healthy controls; however, cART showed no effect in lowering sCD14 levels in HIV-infected individuals before or after initiation of treatment, even after 8 years in some cases (42). cART is more effective at limiting plasma sCD163 levels, though relative to uninfected individuals, there is discrepancy on whether levels are comparable or higher (42, 112, 113). Further, CD14+ monocytes were shown to exhibit increased p90RSK activity, which is a reactive oxygen species-sensitive kinase, in the presence of cART which suppresses NRF2-ARE transcriptional activity eliciting a senescent phenotype along with pro-inflammatory responses (114). In another study, HIV cell-associated DNA (in CSF and blood) and sCD163 (in CSF) were significantly correlated with cognitive impairment, particularly executive function, in older adults, but not in young adults (115). Further, it has been suggested that, plasma sCD163 (but not CSF sCD163) is associated with the severity of symptoms related to cognitive impairment (116). Upon HIV-infection, CD14 and CD163 appear to be the primary drivers of accelerated aging of T cells and immunosenescence, which likely occurs due to chronic immune activation, even in the presence of cART.

CSF and CNS-Specific Markers

HAND is a complex of neurological disorders characterized by severity and development of cognitive impairments such as mental slowness and memory loss, and motor symptoms including poor balance and tremors. HAND is associated with activation of pathways involved in inflammation and aging (117). Despite cART improvements, HAND still affects between 18 to 55% of HIV+ individuals receiving treatment (11, 118–120). Biomarkers would aid in developing therapeutics prior to manifestation of severe pathologies. One specific marker proposed for CNS dysfunction is neopterin ( Table 1 ), a pteridine-metabolite produced primarily during Th1-type responses to inflammatory stimuli such as IFN-γ (121). Although serum levels of neopterin are more closely correlated with overall clinical severity, neopterin in the CSF is a marker for innate cell activation specifically in the CNS. Such immune activation can disrupt CNS homeostasis, thereby leading to HAND development. Neopterin has been correlated with neurocognitive decline (59, 60).

Several other CSF biomarkers have been proposed as detailed in Table 1 . For example, NT3 is a neurotrophic factor that aids in the survival and differentiation of neurons to stimulate growth and has been robustly linked to neurocognitive impairment in PLWH. Lower levels of NT3 were detected in cART-treated HIV-infected individuals (42). Further, higher sCD14 levels have been correlated with impaired neurocognitive function, specifically attention and learning of HIV-infected individuals (31). Recently, sCD30 was shown to co-localize with HIV-1 RNA and DNA in lymphoid tissues. Plasma levels of sCD30 were lower in individuals with cART-suppressed viremia compared to viremic patients. However, sCD30 was elevated in CSF during CNS infection, regardless of peripheral viral load, potentially indicating continued CNS replication and subsequent resultant damage (65). Further, a pannexin-1 (Panx-1)-specific pathway was associated with compromised CNS. Upon HIV binding to CD4 and co-receptors CXCR4 and/or CCR5, Panx-1 channels open to release local intracellular secondary messengers such as ATP and PGE2 from circulating PBMCs ( Figure 1 ). Serum ATP levels were positively correlated with HAND severity (67). Finally, a common CSF marker S100B has been correlated with AIDS dementia complex (ADC) severity and predictive of ADC progression (69). However, use of S100B as a biomarker remains controversial (122).

Neuroimaging

Less invasive methods of assessing CNS changes, including those leading to HAND, have also been studied using advanced neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) ( Table 1 ). In the absence of other diagnostic markers at the time of HAND diagnosis, an MRI is frequently performed to confirm there are no other CNS pathologies that could be contributing to cognitive changes, including those that occur naturally with aging. Characteristic volumetric changes that occur in HAND include loss of white and grey matter and enlarged ventricle size resulting from the lost parenchymal mass (72–74). Multiple studies have confirmed that HIV and aging are independently associated with grey and white matter loss with the latter more impacted by aging than by HIV status. Such atrophy was associated with lower scores on neuropsychological tests (75, 123). Another MRI application is magnetic resonance spectroscopy. By suppressing the signal of water molecules during analysis, various CNS metabolites can be distinguished by their unique chemical shift peaks. Typical metabolites used specifically to study HAND include choline (cho), myo-inositol (MI), and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA). Cho, a marker of cell membrane degradation and inflammation, is increased in HIV+ individuals (76, 77), particularly among HAND patients (78, 79). This trend is especially pronounced in the basal ganglia (77, 80). These changes were even more pronounced in older individuals (78). MI, a marker of gliosis and neuroinflammation, is also increased in HAND, specifically in the basal ganglia (78, 80). The opposite trend has been noted for NAA, a marker of neuron viability and integrity, with greatest decreases in the basal ganglia and white matter (76–79, 81, 93).

Microbiome

During HIV pathogenesis, chronic inflammation is driven partially by continued low-level viral replication; however, increased microbe and microbial byproduct translocation across the damaged intestinal epithelial barrier increase inflammation, especially lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (124). LPS is able to induce pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in myeloid cells after binding to the CD14/TLR4/MD2 receptor complex. Because LPS can drive much of the pathogenesis, serum levels can be monitored to better understand the source of inflammation during HIV pathogenesis. Additional markers associated with gut damage like intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (I-FABP) and other proteins upregulated in the presences of LPS, including LPS-binding protein and sCD14, can also be used as markers of microbiome changes (110, 125, 126). Similarly, (1→3)-β-D-Glucan (βDG), a major component of fungal cell walls can also be used as a marker of microbial translocation (127, 128). As humans age, there is progressive replacement of butyrate-producing Firmicutes with Bacteroidetes, particularly Prevotella (90, 91) and the same pattern has been observed in HIV-infected individuals (92–94). Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid metabolite of dietary fiber fermentation used as the primary energy source for colonocytes and the promotion of Treg differentiation, thereby protecting the intestinal epithelial barrier from damage (129, 130). Butyrate may also as an HDAC1 inhibitor (HDI) serving as a latency-reversing agent for T cell viral reservoirs ( Figure 1 ) (131, 132). Butyrate produced in the gut can also alter CNS health increasing neurogenesis protecting against neurodegeneration (133, 134).

Studies documenting changes that occur after pro-biotic supplementation further highlight the role of the microbiome in inflammation, HIV pathogenesis, and associated aging. In one study, patients who received probiotic cocktails had a reduction in CD4+ T cell activation markers, including HLA-DR and CD38. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and LBP were also reduced to levels comparable to uninfected controls (135). In another study, HIV-infected patients given Lactobacillus casei Shirota supplements had increased T cell counts. This was accompanied by reduced mRNA levels of TGFβ, IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-12, as well as an increase in IL-23 (136). Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that a probiotic cocktail increased serum serotonin levels and decreased tryptophan, as well as decreased surface markers CD38 and HLA-DR on CD4+ T-cells and mRNA expression of IDO and IFN-γ in PBMCs (137). Finally, another study correlated indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) with levels of neopterin in CSF, both of which were significantly decreased with probiotic supplementation (138). These examples demonstrate that changes to the microbiome during HIV pathogenesis may not only serve as biomarkers of inflammation, but may ultimately be a source of the inflammaging processes and a target for therapeutic interventions.

Exosomes

Exosomes may be another potential biomarker for HIV pathogenesis. Exosomes are ~30–150 nm extracellular vesicles released from various cell types into plasma, urine, CSF, and inflammatory tissues. The content of exosome cargoes can be changed depending on pathological state or health of the secreting cell, particularly by immune activation (139). Exosomes of different origins can be obtained from the periphery. A recent study investigated proteins associated with neuronal damage in plasma neuron-derived exosomes (NDE) within the context of HIV-infection to differentiate age-associated from HIV-associated neurocognitive decline. NDE counts were positively correlated with age only in HIV-infected subjects, not in their seronegative controls (38). An earlier investigation reported premature cellular senescence caused an increase in the secretion of exosomes (140). Further, another study characterized plasma exosomes isolated from virally suppressed PLWH on cART with respect to immune responses and oxidative stress. They observed higher levels of exosomes in PLWH on cART compared to seronegative controls and found a positive correlation with oxidative stress markers such as CD14, CRP, HLA-A, and HLA-B and a potentially novel one, Notch4 among the exosome contents (141). Notch-4 is involved in regulating cell-fate determination and influencing the differentiation, proliferation, and apoptotic programs of myeloid and dendritic cells (40). Remarkably, exosomal Notch-4 presence was correlated with HLA-DR and decreased CD4/CD8 ratio, which are reliable predictors of immune activation, thus identifying Notch-4 as a promising new biomarker of immune activation in HIV-infection ( Figure 1 ) (141). Further, exosomes originating from HIV-1 infected T cells are reportedly involved in several processes of infection such as production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages, CD4+ T-cell apoptosis, and neurotoxicity (142–144). These studies collectively suggest that exosomes may serve as a novel avenue for examining mechanisms of premature aging and senescence during HIV-infection ( Table 1 ).

Conclusion

Complications observed in PLWH today are CVD, liver disease, neurological decline, non-AIDS related cancers, and metabolic disorders. These are features of normal aging occurring at an earlier chronological age in the HIV-infected population due to persistent chronic immune activation and inflammation. While cART has successfully extended the lives of PLWH, some of these premature aging comorbidities are exacerbated by cART. Therefore, it is important to continue investigating biomarkers of the premature aging process with the aim of developing new treatment avenues and improving quality of life for PLWH. The markers reported throughout this review arise from divergent pathways, and many of them are associated with specific pathology, such as CNS-specific markers. Clinicians should be aware of these diverse mechanisms and potential sources of inflammation, at which point interventions may be necessary. Regardless of current clinical implications, understanding biomarkers of inflammation and aging that are associated with HIV will allow for development of better therapeutics. Additionally, non-human primate model studies offer an ideal avenue for experimentally investigating these biomarkers as they relate to inflammation and thus the pathology of accelerated aging in HIV.

Author Contributions

MT and SJ convinced the ideas and prepared draft. AA, SP, and MM edited and contributed to the draft. SB convinced the ideas, design, and edited the draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH grants, R01AI129745, P30MH062261, R01DA052845, and R01AI113883.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors SB.

References

- 1. Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, Campisi J, Cuervo AM, Epel ES, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell (2014) 159(4):709–13. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell (2013) 153(6):1194–217. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. DNA damage, metabolism and aging in pro-inflammatory T cells: Rheumatoid arthritis as a model system. Exp Gerontol (2018) 105:118–27. 10.1016/j.exger.2017.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanada F, Taniyama Y, Muratsu J, Otsu R, Shimizu H, Rakugi H, et al. Source of Chronic Inflammation in Aging. Front Cardiovasc Med (2018) 5:12:12. 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herbein G, Gras G, Khan KA, Abbas W. Macrophage signaling in HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology (2010) 7:34. 10.1186/1742-4690-7-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abbas W. Herbein G. T-Cell Signaling in HIV-1 Infection. Open Virol J (2013) 7:57–71. 10.2174/1874357920130621001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet (Lond Engl) (2008) 372(9635):293–9. 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61113-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harris TG, Rabkin M, El-Sadr WM. Achieving the fourth 90: healthy aging for people living with HIV. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2018) 32(12):1563–9. 10.1097/qad.0000000000001870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Autenrieth CS, Beck EJ, Stelzle D, Mallouris C, Mahy M, Ghys P. Global and regional trends of people living with HIV aged 50 and over: Estimates and projections for 2000-2020. PloS One (2018) 13(11):e0207005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0207005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hileman CO, Funderburg NT. Inflammation, Immune Activation, and Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep (2017) 14(3):93–100. 10.1007/s11904-017-0356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr., Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology (2010) 75(23):2087–96. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Younas M, Psomas C, Reynes J, Corbeau P. Immune activation in the course of HIV-1 infection: Causes, phenotypes and persistence under therapy. HIV Med (2016) 17(2):89–105. 10.1111/hiv.12310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kestens L, Vanham G, Vereecken C, Vandenbruaene M, Vercauteren G, Colebunders RL, et al. Selective increase of activation antigens HLA-DR and CD38 on CD4+ CD45RO+ T lymphocytes during HIV-1 infection. Clin Exp Immunol (1994) 95(3):436–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb07015.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sachdeva M, Fischl MA, Pahwa R, Sachdeva N, Pahwa S. Immune exhaustion occurs concomitantly with immune activation and decrease in regulatory T cells in viremic chronically HIV-1-infected patients. J acquired Immune deficiency syndromes (1999) (2010) 54(5):447–54. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e0c7d0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Appay V, Fastenackels S, Katlama C, Ait-Mohand H, Schneider L, Guihot A, et al. Old age and anti-cytomegalovirus immunity are associated with altered T-cell reconstitution in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2011) 25(15):1813–22. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834640e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med (2011) 62:141–55. 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Müller L, Di Benedetto S, Pawelec G. The Immune System and Its Dysregulation with Aging. Sub-cellular Biochem (2019) 91:21–43. 10.1007/978-981-13-3681-2_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Couturier J, Suliburk JW, Brown JM, Luke DJ, Agarwal N, Yu X, et al. Human adipose tissue as a reservoir for memory CD4+ T cells and HIV. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2015) 29(6):667–74. 10.1097/qad.0000000000000599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riangwiwat T, Kohorn LB, Chow DC, Souza SA, Ndhlovu LC, Wong JW, et al. CD4/CD8 Ratio Predicts Peripheral Fat in HIV-Infected Population. J acquired Immune deficiency syndromes (1999) (2016) 72(1):e17–9. 10.1097/qai.0000000000000955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mhandire K, Mlambo T, Zijenah LS, Duri K, Mateveke K, Tshabalala M, et al. Plasma IP-10 Concentrations Correlate Positively with Viraemia and Inversely with CD4 Counts in Untreated HIV Infection. Open AIDS J (2017) 11:24–31. 10.2174/1874613601711010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramirez LA, Arango TA, Thompson E, Naji M, Tebas P, Boyer JD. High IP-10 levels decrease T cell function in HIV-1-infected individuals on ART. J Leukocyte Biol (2014) 96(6):1055–63. 10.1189/jlb.3A0414-232RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Z, Wu T, Ma M, Zhang Z, Fu Y, Liu J, et al. Elevated interferon-γ-induced protein 10 and its receptor CXCR3 impair NK cell function during HIV infection. J Leukocyte Biol (2017) 102(1):163–70. 10.1189/jlb.5A1016-444R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cameron PU, Saleh S, Sallmann G, Solomon A, Wightman F, Evans VA, et al. Establishment of HIV-1 latency in resting CD4+ T cells depends on chemokine-induced changes in the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U States America (2010) 107(39):16934–9. 10.1073/pnas.1002894107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hattab S, Guiguet M, Carcelain G, Fourati S, Guihot A, Autran B, et al. Soluble biomarkers of immune activation and inflammation in HIV infection: impact of 2 years of effective first-line combination antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med (2015) 16(9):553–62. 10.1111/hiv.12257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viganò A, Pinti M, Nasi M, Moretti L, Balli F, Mussini C, et al. Markers of cell death-activation in lymphocytes of vertically HIV-infected children naive to highly active antiretroviral therapy: the role of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2001) 108(3):439–45. 10.1067/mai.2001.117791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sainz T, Serrano-Villar S, Díaz L, González Tomé MI, Gurbindo MD, de José MI, et al. The CD4/CD8 ratio as a marker T-cell activation, senescence and activation/exhaustion in treated HIV-infected children and young adults. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2013) 27(9):1513–6. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835faa72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gianesin K, Noguera-Julian A, Zanchetta M, Del Bianco P, Petrara MR, Freguja R, et al. Premature aging and immune senescence in HIV-infected children. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2016) 30(9):1363–73. 10.1097/qad.0000000000001093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marks MA, Rabkin CS, Engels EA, Busch E, Kopp W, Rager H, et al. Markers of microbial translocation and risk of AIDS-related lymphoma. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2013) 27(3):469–74. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835c1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zheng HY, Zhang MX, Chen M, Jiang J, Song JH, Lian XD, et al. Accelerated disease progression and robust innate host response in aged SIVmac239-infected Chinese rhesus macaques is associated with enhanced immunosenescence. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):37. 10.1038/s41598-017-00084-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shive CL, Jiang W, Anthony DD, Lederman MM. Soluble CD14 is a nonspecific marker of monocyte activation. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2015) 29(10):1263–5. 10.1097/qad.0000000000000735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lyons JL, Uno H, Ancuta P, Kamat A, Moore DJ, Singer EJ, et al. Plasma sCD14 is a biomarker associated with impaired neurocognitive test performance in attention and learning domains in HIV infection. J acquired Immune deficiency syndromes (1999) (2011) 57(5):371–9. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182237e54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Poesen R, Ramezani A, Claes K, Augustijns P, Kuypers D, Barrows IR, et al. Associations of Soluble CD14 and Endotoxin with Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Progression of Kidney Disease among Patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN (2015) 10(9):1525–33. 10.2215/cjn.03100315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kristiansen M, Graversen JH, Jacobsen C, Sonne O, Hoffman HJ, Law SK, et al. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature (2001) 409(6817):198–201. 10.1038/35051594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Castley A, Williams L, James I, Guelfi G, Berry C, Nolan D. Plasma CXCL10, sCD163 and sCD14 Levels Have Distinct Associations with Antiretroviral Treatment and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. PloS One (2016) 11(6):e0158169. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, Cheng WJ, Maisa A, Landay AL, et al. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell (2012) 11(5):867–75. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dufour JH, Dziejman M, Liu MT, Leung JH, Lane TE, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2002) 168(7):3195–204. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Hooij A, Boeters DM, Tjon Kon Fat EM, van den Eeden SJF, Corstjens P, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, et al. Longitudinal IP-10 Serum Levels Are Associated with the Course of Disease Activity and Remission in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin vaccine Immunol CVI (2017) 24(8):1563–73. 10.1128/cvi.00060-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sun B, Dalvi P, Abadjian L, Tang N, Pulliam L. Blood neuron-derived exosomes as biomarkers of cognitive impairment in HIV. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2017) 31(14):F9–f17. 10.1097/qad.0000000000001595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goetzl EJ, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Kapogiannis D. High complement levels in astrocyte-derived exosomes of Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol (2018) 83(3):544–52. 10.1002/ana.25172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Uyttendaele H, Ho J, Rossant J, Kitajewski J. Vascular patterning defects associated with expression of activated Notch4 in embryonic endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U States America (2001) 98(10):5643–8. 10.1073/pnas.091584598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shibata N, Ohnuma T, Higashi S, Higashi M, Usui C, Ohkubo T, et al. Genetic association between Notch4 polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s disease in the Japanese population. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci (2007) 62(4):350–1. 10.1093/gerona/62.4.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Babu H, Ambikan AT, Gabriel EE, Svensson Akusjärvi S, Palaniappan AN, Sundaraj V, et al. Systemic Inflammation and the Increased Risk of Inflamm-Aging and Age-Associated Diseases in People Living With HIV on Long Term Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1965. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A, Ojala J, Haapasalo A, Soininen H, et al. Impaired autophagy and APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease: The potential role of Beclin 1 interactome. Prog Neurobiol (2013) 106-107:33–54. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Castro AG, Hauser TM, Cocks BG, Abrams J, Zurawski S, Churakova T, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of mouse signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM): differential expression and responsiveness in Th1 and Th2 cells. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (1999) 163(11):5860–70. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Panezai J, Ali A, Ghaffar A, Benchimol D, Altamash M, Klinge B, et al. Upregulation of circulating inflammatory biomarkers under the influence of periodontal disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Cytokine (2020) 131:155117. 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim J, Kim YS, Ko J. CK beta 8/CCL23 induces cell migration via the Gi/Go protein/PLC/PKC delta/NF-kappa B and is involved in inflammatory responses. Life Sci (2010) 86(9-10):300–8. 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rioja I, Hughes FJ, Sharp CH, Warnock LC, Montgomery DS, Akil M, et al. Potential novel biomarkers of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients: CXCL13, CCL23, transforming growth factor alpha, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Arthritis Rheum (2008) 58(8):2257–67. 10.1002/art.23667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Simats A, García-Berrocoso T, Penalba A, Giralt D, Llovera G, Jiang Y, et al. CCL23: a new CC chemokine involved in human brain damage. J Internal Med (2018) 283(5):461–75. 10.1111/joim.12738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Çelik H, Lindblad KE, Popescu B, Gui G, Goswami M, Valdez J, et al. Highly multiplexed proteomic assessment of human bone marrow in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv (2020) 4(2):367–79. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luther JA, Birren SJ. Neurotrophins and target interactions in the development and regulation of sympathetic neuron electrical and synaptic properties. Autonomic Neurosci Basic Clin (2009) 151(1):46–60. 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meeker RB, Poulton W, Markovic-Plese S, Hall C, Robertson K. Protein changes in CSF of HIV-infected patients: evidence for loss of neuroprotection. J Neurovirol (2011) 17(3):258–73. 10.1007/s13365-011-0034-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Luo Y, Kaz AM, Kanngurn S, Welsch P, Morris SM, Wang J, et al. NTRK3 is a potential tumor suppressor gene commonly inactivated by epigenetic mechanisms in colorectal cancer. PloS Genet (2013) 9(7):e1003552. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yuan X, Gajan A, Chu Q, Xiong H, Wu K, Wu GS. Developing TRAIL/TRAIL death receptor-based cancer therapies. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2018) 37(4):733–48. 10.1007/s10555-018-9728-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu YY, Hsu JL, Wang HC, Wu SJ, Hong CJ, Cheng IH. Alterations of the Neuroinflammatory Markers IL-6 and TRAIL in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dementia Geriatric Cogn Disord extra (2015) 5(3):424–34. 10.1159/000439214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lum JJ, Pilon AA, Sanchez-Dardon J, Phenix BN, Kim JE, Mihowich J, et al. Induction of cell death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected macrophages and resting memory CD4 T cells by TRAIL/Apo2l. J Virol (2001) 75(22):11128–36. 10.1128/jvi.75.22.11128-11136.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin AW, Barradas M, Stone JC, van Aelst L, Serrano M, Lowe SW. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev (1998) 12(19):3008–19. 10.1101/gad.12.19.3008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gorwood J, Ejlalmanesh T, Bourgeois C, Mantecon M, Rose C, Atlan M, et al. SIV Infection and the HIV Proteins Tat and Nef Induce Senescence in Adipose Tissue and Human Adipose Stem Cells, Resulting in Adipocyte Dysfunction. Cells (2020) 9(4):1387–95. 10.3390/cells9040854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Molofsky AV, Slutsky SG, Joseph NM, He S, Pardal R, Krishnamurthy J, et al. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature (2006) 443(7110):448–52. 10.1038/nature05091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hagberg L, Cinque P, Gisslen M, Brew BJ, Spudich S, Bestetti A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neopterin: an informative biomarker of central nervous system immune activation in HIV-1 infection. AIDS Res Ther (2010) 7:15. 10.1186/1742-6405-7-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fuchs D, Chiodi F, Albert J, Asjö B, Hagberg L, Hausen A, et al. Neopterin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of individuals infected with HIV-1. AIDS (Lond Engl) (1989) 3(5):285–8. 10.1097/00002030-198905000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Spencer ME, Jain A, Matteini A, Beamer BA, Wang NY, Leng SX, et al. Serum levels of the immune activation marker neopterin change with age and gender and are modified by race, BMI, and percentage of body fat. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci (2010) 65(8):858–65. 10.1093/gerona/glq066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Edén A, Marcotte TD, Heaton RK, Nilsson S, Zetterberg H, Fuchs D, et al. Increased Intrathecal Immune Activation in Virally Suppressed HIV-1 Infected Patients with Neurocognitive Impairment. PloS One (2016) 11(6):e0157160. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Forgrave LM, Ma M, Best JR, DeMarco ML. The diagnostic performance of neurofilament light chain in CSF and blood for Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s dementia (Amsterdam Netherlands) (2019) 11:730–43. 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gaiottino J, Norgren N, Dobson R, Topping J, Nissim A, Malaspina A, et al. Increased neurofilament light chain blood levels in neurodegenerative neurological diseases. PloS One (2013) 8(9):e75091. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peluso MJ, Thanh C, Prator CA, Hogan LE, Arechiga VM, Stephenson S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble CD30 elevation despite suppressive antiretroviral therapy in individuals living with HIV-1. J Virus Eradication (2020) 6(1):19–26. 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30006-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gerli R, Monti D, Bistoni O, Mazzone AM, Peri G, Cossarizza A, et al. Chemokines, sTNF-Rs and sCD30 serum levels in healthy aged people and centenarians. Mech Ageing Dev (2000) 121(1-3):37–46. 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00195-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Velasquez S, Prevedel L, Valdebenito S, Gorska AM, Golovko M, Khan N, et al. Circulating levels of ATP is a biomarker of HIV cognitive impairment. EBioMedicine (2020) 51:102503. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Volonté C, Amadio S, Cavaliere F, D’Ambrosi N, Vacca F, Bernardi G. Extracellular ATP and neurodegeneration. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord (2003) 2(6):403–12. 10.2174/1568007033482643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pemberton LA, Brew BJ. Cerebrospinal fluid S-100beta and its relationship with AIDS dementia complex. J Clin Virol Off Publ Pan Am Soc Clin Virol (2001) 22(3):249–53. 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00196-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cirillo C, Sarnelli G, Esposito G, Turco F, Steardo L, Cuomo R. S100B protein in the gut: the evidence for enteroglial-sustained intestinal inflammation. World J Gastroenterol (2011) 17(10):1261–6. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rothermundt M, Peters M, Prehn JH, Arolt V. S100B in brain damage and neurodegeneration. Microscopy Res Technique (2003) 60(6):614–32. 10.1002/jemt.10303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bonnet F, Amieva H, Marquant F, Bernard C, Bruyand M, Dauchy FA, et al. Cognitive disorders in HIV-infected patients: are they HIV-related? AIDS (Lond Engl) (2013) 27(3):391–400. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nichols MJ, Gates TM, Soares JR, Moffat KJ, Rae CD, Brew BJ, et al. Atrophic brain signatures of mild forms of neurocognitive impairment in virally suppressed HIV infection. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2019) 33(1):55–66. 10.1097/qad.0000000000002042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kallianpur KJ, Shikuma C, Kirk GR, Shiramizu B, Valcour V, Chow D, et al. Peripheral blood HIV DNA is associated with atrophy of cerebellar and subcortical gray matter. Neurology (2013) 80(19):1792–9. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318291903f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Becker JT, Maruca V, Kingsley LA, Sanders JM, Alger JR, Barker PB, et al. Factors affecting brain structure in men with HIV disease in the post-HAART era. Neuroradiology (2012) 54(2):113–21. 10.1007/s00234-011-0854-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Harezlak J, Buchthal S, Taylor M, Schifitto G, Zhong J, Daar E, et al. Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2011) 25(5):625–33. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283427da7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Paul RH, Ernst T, Brickman AM, Yiannoutsos CT, Tate DF, Cohen RA, et al. Relative sensitivity of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging to cognitive function among nondemented individuals infected with HIV. J Int Neuropsychol Soc JINS (2008) 14(5):725–33. 10.1017/s1355617708080910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Saloner R, Heaton RK, Campbell LM, Chen A, Franklin D, Jr., Ellis RJ, et al. Effects of comorbidity burden and age on brain integrity in HIV. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2019) 33(7):1175–85. 10.1097/qad.0000000000002192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Alakkas A, Ellis RJ, Watson CW, Umlauf A, Heaton RK, Letendre S, et al. White matter damage, neuroinflammation, and neuronal integrity in HAND. J Neurovirol (2019) 25(1):32–41. 10.1007/s13365-018-0682-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yiannoutsos CT, Nakas CT, Navia BA. Assessing multiple-group diagnostic problems with multi-dimensional receiver operating characteristic surfaces: application to proton MR Spectroscopy (MRS) in HIV-related neurological injury. NeuroImage (2008) 40(1):248–55. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mohamed MA, Barker PB, Skolasky RL, Selnes OA, Moxley RT, Pomper MG, et al. Brain metabolism and cognitive impairment in HIV infection: a 3-T magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (2010) 28(9):1251–7. 10.1016/j.mri.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chang K, Premeaux TA, Cobigo Y, Milanini B, Hellmuth J, Rubin LH, et al. Plasma inflammatory biomarkers link to diffusion tensor imaging metrics in virally suppressed HIV-infected individuals. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2020) 34(2):203–13. 10.1097/qad.0000000000002404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cysique LA, Soares JR, Geng G, Scarpetta M, Moffat K, Green M, et al. White matter measures are near normal in controlled HIV infection except in those with cognitive impairment and longer HIV duration. J Neurovirol (2017) 23(4):539–47. 10.1007/s13365-017-0524-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Oh SW, Shin NY, Choi JY, Lee SK, Bang MR. Altered White Matter Integrity in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder: A Tract-Based Spatial Statistics Study. Korean J Radiol (2018) 19(3):431–42. 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.3.431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zhu T, Zhong J, Hu R, Tivarus M, Ekholm S, Harezlak J, et al. Patterns of white matter injury in HIV infection after partial immune reconstitution: a DTI tract-based spatial statistics study. J Neurovirol (2013) 19(1):10–23. 10.1007/s13365-012-0135-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chen Y, An H, Zhu H, Stone T, Smith JK, Hall C, et al. White matter abnormalities revealed by diffusion tensor imaging in non-demented and demented HIV+ patients. NeuroImage (2009) 47(4):1154–62. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pfefferbaum A, Rosenbloom MJ, Rohlfing T, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, Sullivan EV. Frontostriatal fiber bundle compromise in HIV infection without dementia. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2009) 23(15):1977–85. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e77fe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Du H, Wu Y, Ochs R, Edelman RR, Epstein LG, McArthur J, et al. A comparative evaluation of quantitative neuroimaging measurements of brain status in HIV infection. Psychiatry Res (2012) 203(1):95–9. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hoare J, Westgarth-Taylor J, Fouche JP, Spottiswoode B, Paul R, Thomas K, et al. A diffusion tensor imaging and neuropsychological study of prospective memory impairment in South African HIV positive individuals. Metab Brain Dis (2012) 27(3):289–97. 10.1007/s11011-012-9311-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Desai SN, Landay AL. HIV and aging: role of the microbiome. Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2018) 13(1):22–7. 10.1097/coh.0000000000000433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nagpal R, Mainali R, Ahmadi S, Wang S, Singh R, Kavanagh K, et al. Gut microbiome and aging: Physiological and mechanistic insights. Nutr Healthy Aging (2018) 4(4):267–85. 10.3233/nha-170030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Dillon SM, Kibbie J, Lee EJ, Guo K, Santiago ML, Austin GL, et al. Low abundance of colonic butyrate-producing bacteria in HIV infection is associated with microbial translocation and immune activation. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2017) 31(4):511–21. 10.1097/qad.0000000000001366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gootenberg DB, Paer JM, Luevano J-M, Kwon DS. HIV-associated changes in the enteric microbial community: potential role in loss of homeostasis and development of systemic inflammation. Curr Opin Infect Dis (2017) 30(1):31–43. 10.1097/qco.0000000000000341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Armstrong AJS, Shaffer M, Nusbacher NM, Griesmer C, Fiorillo S, Schneider JM, et al. An exploration of Prevotella-rich microbiomes in HIV and men who have sex with men. Microbiome (2018) 6(1):198. 10.1186/s40168-018-0580-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pallikkuth S, de Armas L, Rinaldi S. Pahwa S. T Follicular Helper Cells and B Cell Dysfunction in Aging and HIV-1 Infection. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1380:1380. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Jose SS, Bendickova K, Kepak T, Krenova Z, Fric J. Chronic Inflammation in Immune Aging: Role of Pattern Recognition Receptor Crosstalk with the Telomere Complex? Front Immunol (2017) 8:1078:1078. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cobos Jiménez V, Wit FW, Joerink M, Maurer I, Harskamp AM, Schouten J, et al. T-Cell Activation Independently Associates With Immune Senescence in HIV-Infected Recipients of Long-term Antiretroviral Treatment. J Infect Dis (2016) 214(2):216–25. 10.1093/infdis/jiw146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhao J, Nguyen LNT, Nguyen LN, Dang X, Cao D, Khanal S, et al. ATM Deficiency Accelerates DNA Damage, Telomere Erosion, and Premature T Cell Aging in HIV-Infected Individuals on Antiretroviral Therapy. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2531:2531. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Piekna-Przybylska D, Maggirwar SB. CD4+ memory T cells infected with latent HIV-1 are susceptible to drugs targeting telomeres. Cell Cycle (Georgetown Tex) (2018) 17(17):2187–203. 10.1080/15384101.2018.1520568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lagathu C, Cossarizza A, Béréziat V, Nasi M, Capeau J, Pinti M. Basic science and pathogenesis of ageing with HIV: potential mechanisms and biomarkers. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2017) 31 Suppl 2:S105–s19. 10.1097/qad.0000000000001441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Horvath S, Levine AJ. HIV-1 Infection Accelerates Age According to the Epigenetic Clock. J Infect Dis (2015) 212(10):1563–73. 10.1093/infdis/jiv277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Gross AM, Jaeger PA, Kreisberg JF, Licon K, Jepsen KL, Khosroheidari M, et al. Methylome-wide Analysis of Chronic HIV Infection Reveals Five-Year Increase in Biological Age and Epigenetic Targeting of HLA. Mol Cell (2016) 62(2):157–68. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Tsukahara H, Shibata R, Ohshima Y, Todoroki Y, Sato S, Ohta N, et al. Oxidative stress and altered antioxidant defenses in children with acute exacerbation of atopic dermatitis. Life Sci (2003) 72(22):2509–16. 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00145-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Höhn A, König J, Grune T. Protein oxidation in aging and the removal of oxidized proteins. J Proteomics (2013) 92:132–59. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Krisko A, Radman M. Protein damage, ageing and age-related diseases. Open Biol (2019) 9(3):180249. 10.1098/rsob.180249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sundermann EE, Hussain MA, Moore DJ, Horvath S, Lin DTS, Kobor MS, et al. Inflammation-related genes are associated with epigenetic aging in HIV. J Neurovirol (2019) 25(6):853–65. 10.1007/s13365-019-00777-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Stacey AR, Norris PJ, Qin L, Haygreen EA, Taylor E, Heitman J, et al. Induction of a striking systemic cytokine cascade prior to peak viremia in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, in contrast to more modest and delayed responses in acute hepatitis B and C virus infections. J Virol (2009) 83(8):3719–33. 10.1128/jvi.01844-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Montoya JL, Campbell LM, Paolillo EW, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Jeste DV, et al. Inflammation Relates to Poorer Complex Motor Performance Among Adults Living With HIV on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. J acquired Immune deficiency syndromes (1999) (2019) 80(1):15–23. 10.1097/qai.0000000000001881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Etzerodt A, Moestrup SK. CD163 and inflammation: biological, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects. Antioxid Redox Signaling (2013) 18(17):2352–63. 10.1089/ars.2012.4834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sandler NG, Wand H, Roque A, Law M, Nason MC, Nixon DE, et al. Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection. J Infect Dis (2011) 203(6):780–90. 10.1093/infdis/jiq118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Knudsen TB, Ertner G, Petersen J, Møller HJ, Moestrup SK, Eugen-Olsen J, et al. Plasma Soluble CD163 Level Independently Predicts All-Cause Mortality in HIV-1-Infected Individuals. J Infect Dis (2016) 214(8):1198–204. 10.1093/infdis/jiw263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. D’Antoni ML, Byron MM, Chan P, Sailasuta N, Sacdalan C, Sithinamsuwan P, et al. Normalization of Soluble CD163 Levels After Institution of Antiretroviral Therapy During Acute HIV Infection Tracks with Fewer Neurological Abnormalities. J Infect Dis (2018) 218(9):1453–63. 10.1093/infdis/jiy337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Castley A, Berry C, French M, Fernandez S, Krueger R, Nolan D. Elevated plasma soluble CD14 and skewed CD16+ monocyte distribution persist despite normalisation of soluble CD163 and CXCL10 by effective HIV therapy: a changing paradigm for routine HIV laboratory monitoring? PloS One (2014) 9(12):e115226. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Singh MV, Kotla S, Le NT, Ae Ko K, Heo KS, Wang Y, et al. Senescent Phenotype Induced by p90RSK-NRF2 Signaling Sensitizes Monocytes and Macrophages to Oxidative Stress in HIV-Positive Individuals. Circulation (2019) 139(9):1199–216. 10.1161/circulationaha.118.036232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. de Oliveira MF, Murrell B, Pérez-Santiago J, Vargas M, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, et al. Circulating HIV DNA Correlates With Neurocognitive Impairment in Older HIV-infected Adults on Suppressive ART. Sci Rep (2015) 5:17094. 10.1038/srep17094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Burdo TH, Weiffenbach A, Woods SP, Letendre S, Ellis RJ, Williams KC. Elevated sCD163 in plasma but not cerebrospinal fluid is a marker of neurocognitive impairment in HIV infection. AIDS (Lond Engl) (2013) 27(9):1387–95. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32836010bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Smith JA, Das A, Ray SK, Banik NL. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Bull (2012) 87(1):10–20. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. McArthur JC, Brew BJ. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: is there a hidden epidemic? AIDS (Lond Engl) (2010) 24(9):1367–70. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283391d56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zayyad Z, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis of HIV: from initial neuroinvasion to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). Curr HIV/AIDS Rep (2015) 12(1):16–24. 10.1007/s11904-014-0255-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Robertson K, Landay A, Miyahara S, Vecchio A, Masters MC, Brown TT, et al. Limited correlation between systemic biomarkers and neurocognitive performance before and during HIV treatment. J Neurovirol (2020) 26(1):107–13. 10.1007/s13365-019-00795-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Fuchs D, Spira TJ, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Felmayer GW, et al. Neopterin as a predictive marker for disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin Chem (1989) 35(8):1746–9. 10.1093/clinchem/35.8.1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Limpruttidham N, Mitchell BI, Kallianpur KJ, Nakamoto BK, Souza SA, Shiramizu B, et al. S100B and its association with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurovirol (2019) 25(6):899–900. 10.1007/s13365-019-00773-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Ances BM, Ortega M, Vaida F, Heaps J, Paul R. Independent effects of HIV, aging, and HAART on brain volumetric measures. J acquired Immune deficiency syndromes (1999) (2012) 59(5):469–77. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249db17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Sandler NG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol (2012) 10(9):655–66. 10.1038/nrmicro2848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Hunt PW, Sinclair E, Rodriguez B, Shive C, Clagett B, Funderburg N, et al. Gut epithelial barrier dysfunction and innate immune activation predict mortality in treated HIV infection. J Infect Dis (2014) 210(8):1228–38. 10.1093/infdis/jiu238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Funderburg NT, Boucher M, Sattar A, Kulkarni M, Labbato D, Kinley BI, et al. Rosuvastatin Decreases Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein (I-FABP), but Does Not Alter Zonulin or Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (LBP) Levels, in HIV-Infected Subjects on Antiretroviral Therapy. Pathog Immun (2016) 1(1):118–28. 10.20411/pai.v1i1.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Mehraj V, Ramendra R, Isnard S, Dupuy FP, Ponte R, Chen J, et al. Circulating (1→3)-β-D-glucan Is Associated With Immune Activation During Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc America (2020) 70(2):232–41. 10.1093/cid/ciz212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ramendra R, Isnard S, Mehraj V, Chen J, Zhang Y, Finkelman M, et al. Circulating LPS and (1→3)-β-D-Glucan: A Folie à Deux Contributing to HIV-Associated Immune Activation. Front Immunol (2019) 10(465):448–52. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature (2013) 504(7480):446–50. 10.1038/nature12721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature (2013) 504(7480):451–5. 10.1038/nature12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Margolis DM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and HIV latency. Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2011) 6(1):25–9. 10.1097/COH.0b013e328341242d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Rasmussen TA, Lewin SR. Shocking HIV out of hiding: where are we with clinical trials of latency reversing agents? Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2016) 11(4):394–401. 10.1097/coh.0000000000000279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Kundu P, Lee HU, Garcia-Perez I, Tay EXY, Kim H, Faylon LE, et al. Neurogenesis and prolongevity signaling in young germ-free mice transplanted with the gut microbiota of old mice. Sci Trans Med (2019) 11(518):37–46. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau4760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, Mailing LJ, Woods JA, Johnson RW. Butyrate and Dietary Soluble Fiber Improve Neuroinflammation Associated With Aging in Mice. Front Immunol (2018) 9:1832:1832. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. d’Ettorre G, Ceccarelli G, Giustini N, Serafino S, Calantone N, De Girolamo G, et al. Probiotics Reduce Inflammation in Antiretroviral Treated, HIV-Infected Individuals: Results of the “Probio-HIV” Clinical Trial. PloS One (2015) 10(9):e0137200. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Falasca K, Vecchiet J, Ucciferri C, Di Nicola M, D’Angelo C, Reale M. Effect of Probiotic Supplement on Cytokine Levels in HIV-Infected Individuals: A Preliminary Study. Nutrients (2015) 7(10):8335–47. 10.3390/nu7105396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Scheri GC, Fard SN, Schietroma I, Mastrangelo A, Pinacchio C, Giustini N, et al. Modulation of Tryptophan/Serotonin Pathway by Probiotic Supplementation in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Patients: Preliminary Results of a New Study Approach. Int J Tryptophan Res IJTR (2017) 10:1178646917710668. 10.1177/1178646917710668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Scagnolari C, Corano Scheri G, Selvaggi C, Schietroma I, Najafi Fard S, Mastrangelo A, et al. Probiotics Differently Affect Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Indolamine-2,3-Dioxygenase mRNA and Cerebrospinal Fluid Neopterin Levels in Antiretroviral-Treated HIV-1 Infected Patients: A Pilot Study. Int J Mol Sci (2016) 17(10):539–47. 10.3390/ijms17101639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Pulliam L, Gupta A. Modulation of cellular function through immune-activated exosomes. DNA Cell Biol (2015) 34(7):459–63. 10.1089/dna.2015.2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Lehmann BD, Paine MS, Brooks AM, McCubrey JA, Renegar RH, Wang R, et al. Senescence-associated exosome release from human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res (2008) 68(19):7864–71. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-07-6538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Chettimada S, Lorenz DR, Misra V, Dillon ST, Reeves RK, Manickam C, et al. Exosome markers associated with immune activation and oxidative stress in HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):7227. 10.1038/s41598-018-25515-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Sampey GC, Saifuddin M, Schwab A, Barclay R, Punya S, Chung MC, et al. Exosomes from HIV-1-infected Cells Stimulate Production of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines through Trans-activating Response (TAR) RNA. J Biol Chem (2016) 291(3):1251–66. 10.1074/jbc.M115.662171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Lenassi M, Cagney G, Liao M, Vaupotic T, Bartholomeeusen K, Cheng Y, et al. HIV Nef is secreted in exosomes and triggers apoptosis in bystander CD4+ T cells. Traffic (Copenhagen Denmark) (2010) 11(1):110–22. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01006.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Malik S, Eugenin EA. Mechanisms of HIV Neuropathogenesis: Role of Cellular Communication Systems. Curr HIV Res (2016) 14(5):400–11. 10.2174/1570162x14666160324124558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]