Abstract

Vascular networks have an important role to play in transporting nutrients, oxygen, metabolic wastes and maintenance of homeostasis. Bioprinting is a promising technology as it is able to fabricate complex, specific multi-cellular constructs with precision. In addition, current technology allows precise depositions of individual cells, growth factors and biochemical signals to enhance vascular growth. Fabrication of vascularized constructs has remained as a main challenge till date but it is deemed as an important stepping stone to bring organ engineering to a higher level. However, with the ever advancing bioprinting technology and knowledge of biomaterials, it is expected that bioprinting can be a viable solution for this problem. This article presents an overview of the biofabrication of vascular and vascularized constructs, the different techniques used in vascular engineering such as extrusion-based, droplet-based and laser-based bioprinting techniques, and the future prospects of bioprinting of artificial blood vessels.

Keywords: 3D bioprinting, vascularized constructs, vascular tissue engineering, extrusion-based bioprinting, droplet-based bioprinting, laser-based bioprinting

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering has evolved tremendously in the past decades and is set to revolutionize future medical practices and research[1]. One of the recent focus of tissue engineering is on developing artificial biological organs substitutes either for transplantations or as models for drug screening. In such cases, one of the fundamental challenge is to fabricate or create viable and functional vasculatures to support cell growth within the engineered scaffold[2]. Vascularization of implanted grafts or drug models is essential to ensure long-term survival. Cellular viability and activities are found to be severely compromised if there are no capillary networks within ~200 μm of cells[3]. Another urgent need for fabrication of blood vessels is to overcome the problems related to the use of vascular grafts for reconstruction of smaller blood vessels that are <6 mm. Vascular grafts are most commonly used for severe cardiovascular diseases or trauma that resulted in loss of vessels. Even though autologous vessels is considered as the golden standard for vascular grafts, the main challenge lies in availability of viable and functional autologous vessels, especially in elderly patients[4]. Alternative options such as synthetic vessels are currently available in the market, but most are only suitable for large diameter vascular replacements that are >8 mm in diameter. For vessels that are smaller in diameter (<6 mm), synthetic vessels are found to have poor patency rates due to their thrombogenicity[5]. Thus, current strategies are focused on developing effective autonomous vascular grafts which possess similar biomechanical properties as native vessels for implantations and also on recreating the complex vascular networks required in tissues engineering to allow for biofabrication of larger tissues. Since the last decades, there had been much improvements and changes to the various approaches of vascular engineering. This can be attributed to advancing three-dimensional (3D) printing technologies and increasing knowledge on materials and roles of micro-environment factors. Zhao X, et al. harnessed the strong structural properties of synthetic polymers and used it to act as a support scaffold for hydrogels. The concept of wound healing in human was evidently applied into their study. This novel study encapsulates adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) into fibrin/ collagen hydrogels and deposited onto synthetic poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) 3D printed scaffolds. Subsequently, vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) were used to induce ADSCs differentiation to endothelial cells. Interestingly, during the initial induction phase, the hydrogels started to degrade and only ADSCs on the external surface began to differentiate into endothelial cells and began connection with one another. Following which, the ADSCs were then exposed to human plateletderived growth factor, transforming growth factor β1 and b-FGF. This second induction process saw the differentiation of deeper located ADSCs into smooth muscle cells[6]. This study clearly depicts the importance of 3D printing and the need for novel incorporation of other specialties to fabricate vascularized channels. In the past, with traditional manufacturing technology, it was almost impossible to design and manufacture biocompatible branched vascular systems. A recent study by Liu L, et al. showed that it was possible to incorporate the Constrained Constructive Optimization (CCO) mathematical algorithm into designing of various vascular tree models with computer-aided design (CAD) platforms[7]. In this study, they used a self-developed low-temperature deposition manufacturing technology to process and print the various biomaterials under a temperature of -20°c. Both abovementioned studies showed the potential promises of 3D printing in vascular engineering and the need for novelty for future progress of vascular engineering.

In addition to providing essential nutrients to vascularized tissues, studies have shown that sufficient vascularization plays a part in maintaining proper tissue formation and improve clinical outcomes by allowing chemical cross-talks amongst different cells[8]. In vivo vascular networks are formed by two different mechanisms termed as vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Vasculogenesis refers to the generation of new vessels from progenitor cells whilst angiogenesis refers to the formation of new vessels from existing capillaries. Currently, there are various possible approaches to induce or fabricate vascular networks for organ engineering. This article provides a review on the different approaches available for bioprinting of blood vessels. In this review, the term scaffold refers to the 3D material prior to cell culture. The term construct is used to identify scaffolds which have undergone cell culture or are encapsulated with cells.

1.1 Function and Anatomy of Vessels

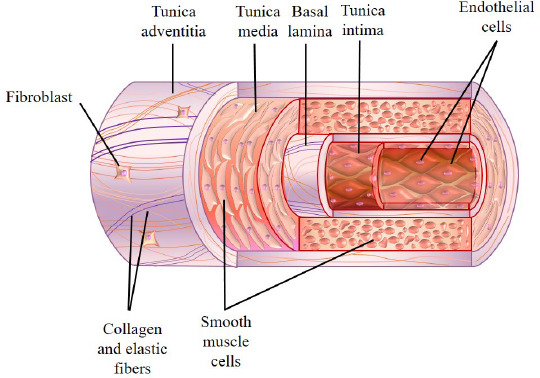

The walls of blood vessels are generally comprised of three layers. The innermost layer is referred to as the tunica intima, followed by the middle layer, tunica media and the outermost layer, tunica adventitia or some refers to it as the tunica externa (Figure 1). Three major constituents are found in the tunica intima: the endothelium, which is formed by a single layer of simple squamous epithelium, the basal lamina, consisting of mainly type IV collagen and laminin, and lastly the subendothelial layer which consists mainly of loose connective tissue. The endothelium, albeit being the thinnest layer of all, has a huge role to play as part of the vessel. Its main function is to form a tight nonthrombogenic barrier that serves a protective role to avoid infections and inflammation of the surrounding tissues. In some cases, smooth muscle cells are present in the loose connective tissue[9]. A fenestrated acellular elastic lamella called the internal elastic membrane is found in the subendothelial layer of tunica intima in arteries and arterioles and plays a role in facilitating the diffusion of substances across the layers. There are also reports stating that tunic intima has a role to play in maintaining the overall structural integrity of the blood vessels by secreting signaling factors to smooth muscles cells or fibroblasts.

Figure 1.

General structural features of a blood vessel.

Surrounding the tunica intima is the tunica media, a muscular layer predominantly comprising of layers of smooth muscle cells arranged circumferentially around the vessel with type I and III collagen[10]. This layer is relatively thicker in arteries than in veins and it spans the whole space between the internal and external elastic membrane. External elastic membrane is an elastic layer that separates tunica media from tunica adventitia. Other constituents of the tunica media include reticular fibers, elastin and proteoglycans which are intercalated between layers of smooth muscle cells. Variable amounts of circularly arranged elastic lamellae with fenestrations are also found in this layer. Unlike tunica adventitia, all extracellular components of the tunica intima and media such as elastin, collagen and ground substances are synthesized by the smooth muscle cells[11]. The outermost layer of the blood vessels is the tunica adventitia, a layer of loose connective tissue with embedded fibroblasts composed mainly of longitudinal collagenous tissue and some elastic fibers. This layer plays a role in anchoring the blood vessel to the surrounding tissue and provision of additional mechanical support[12]. In addition, this layer is found to be relatively thinner in arteries and arterioles and is much thicker in venules and veins as it is the major constituent of their vessel wall. A vascular network called vasa vasorum and an autonomic nervous network called nervi vasorum (vascularis) are present in the tunica adventitia of large arteries and veins. These networks work by supplying nutrients and oxygen to the walls of the blood vessels and regulating vasoconstriction as well as vasodilation by sending signals to the smooth muscles directly from the nervous system, respectively.

The anatomies of arteries and veins are generally quite similar but can be distinguished by the thickness of tunica and their cellular and protein compositions of the layers. Arteries generally have a thicker tunica media and a thinner tunica adventitia. They are traditionally divided into three types based on the size and characteristics of their tunica media, namely the large (or elastic arteries), the medium (or muscular arteries), small arteries and arterioles. Some examples of the large arteries include the aorta, pulmonary arteries and the brachiocephalic trunk. This type of arteries consists of large amount of elastic lamellae in their vascular walls. These elastic lamellae possess the elastic recoil characteristics that can maintain the continuous and uniform blood flow along the vascular tube as well as the arterial blood pressure. In contrast to the tunica media of the large arteries, medium arteries are composed almost entirely of smooth muscle but with little amount of elastin and they contain a prominent internal elastic membrane. Some examples of muscular arteries are femoral artery, radial artery and popliteal artery. Small arteries and arterioles can be distinguished from each other by the thickness of their smooth muscle layers in tunica media. The smooth muscle layers in arterioles are only one or two cells thick whereas those in small arteries may be as many as eight to ten cells thick. Capillaries have the smallest diameter amongst all types of blood vessels, each of them consists of only a single layer of endothelium and their basal lamina. The diameter of their lumen is only large enough to allow one erythrocyte to pass through at a time. Unlike other vessels, tunica media and adventitia are absent in the capillaries.

For veins, they usually have thicker tunica adventitia as compared to the arteries. They are often being classified into four types based on their size, namely the venules (postcapillary and muscular), small veins, medium veins as well as the large veins. The venules can be further subdivided into postcapillary venules and muscular venules based on the presence of tunica media as the former lacks a tunica media in their vascular wall. Postcapillary venules receive blood directly from the capillaries and are characterized by the presence of pericytes. Small veins are continuous with the venules. Medium veins usually represent the named veins in our bodies and are often accompanied by arteries. Some of the examples of medium veins include the radial vein, tibial vein and the popliteal vein. Large veins are veins with a diameter larger than 10 mm and they include the superior and inferior vena cava. A summary of the characteristics of different types of blood vessels are shown in Table 1 and Table 2

Table 1.

Characteristics of various types of arteries.

| Arteries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel | Large artery (elastic artery) | Medium artery (muscular artery) | Small artery | Arteriole | capillary |

| Diameter | > 10 mm | 2 – 10 mm | 0.1 – 2 mm | 10 – 100 μm | 4 – 10 μm |

| Tunica Intima (innermost) | Endothelium Connective tissue Smooth muscle |

Same as large artery except with prominent internal elastic membrane | Same as large artery except with less prominent internal elastic membrane | Same as large artery | Endothelium only |

| Tunica Media (middle) | Smooth muscle Elastic lamellae | Smooth muscle Collagen fibers Lesser elastic tissue |

Smooth muscle (8–10 cells thick) Collagen fibers |

Smooth muscle (1–2 cells thick) | None |

| Tunica Adventitia (outermost) | Thinner than tunica media Connective tissue Elastic fibers |

Same as large artery except with fewer elastic fibers | Same as medium artery | Thin, indistinct connective tissue | None |

Table 2.

Characteristics of various types of veins.

| Veins | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel | Postcapillary venule | Muscular venule | Small vein | Medium vein | Large vein |

| Diameter | 10–50 μm | 50–100 μm | 0.1–1 mm | 1–10 mm | >10 mm |

| Tunica Intima (innermost) | Endothelium Pericytes | Endothelium only | Endothelium Connective tissue Smooth muscle |

Same as small vein except Same as small vein with internal elastic membrane (present in some cases) | |

| Tunica Media (middle) | None | Smooth muscle (1–2 cells thick) | Smooth muscle (continuous with tunica intima; 2–3 layers) | Smooth muscle Collagen fibers | Smooth muscle (2–15 layers) Collagen fibers |

| Tunica Adventitia (outermost) | None | Thicker than tunica media | Same as muscular venule | Same as muscular venule | Much thicker than tunica media |

| Connective tissue | Connective tissue | ||||

| Few elastic fibers | Longitudinal smooth muscle bundles | ||||

| Myocardial sleeves (present in superior and inferior vena cava, pulmonary trunk) | |||||

2. Potential of Bioprinting

Bioprinting can be defined as the fabrication of bioengineered scaffolds or structures by addictive manufacturing of biomaterials and other biologics by using a computer aided layer with layer deposition approach. Introduction of bioprinting in medical research has greatly revolutionize tissue engineering research and created endless possibilities awaiting to be explored. Bioprinting allows rapid fabrication of scaffolds with precise control over porosity, internal architectures and external structures, all of which can allow us to better mimic native in vivo micro-environments[13]. There are currently many commercialized bioprinters, of which bioprinting techniques can be categorized into the following categories: extrusion-based, droplet-based and laser-based bioprinting techniques.

The main principle of extrusion-based technique lies mainly on its ability to deposit continuous strands of materials via a pressurized nozzle. Synthetic or biocompatible materials can be used for this method and can be used for fabricating structures with resolutions of up to several hundred microns[11]. A recent novel extrusion-based technique involves encapsulating cells in biocompatible hydrogels and exploit the shear thinning properties of hydrogels for bioprinting. For such cases, the bioink should be able to remain stable in the syringe and only changes viscosity when being pressurized through a nozzle. After which, the bioprinted scaffold would have to go through certain physical or chemical crosslinking processes to ensure gelation of hydrogel and retention of geometrical structure. Solgel property of bioinks is a critical factor in ensuring printability, therefore restricting the availability of many biomaterials[14]. Nevertheless, extrusion-based technique has been shown to be versatile in depositing a wide range of bioinks such as hydrogels, micro-carriers, tissue strands and decellularized matrix components[15–18]. A recent review article by Ozbolat and Hospodiuk articulated the characteristics of bioprintable bioinks and their applicability and performance in extrusionbased technique[19]. In addition, readers can refer to several other review articles regarding hydrogels in tissue engineering[20,21]. Extrusion-based technique has gradually improved over time and can now be classified into direct and indirect extrusion techniques. Direct extrusion involves bioprinting of cell-laden hydrogels directly into desired structures and cross linked to allow complete retention of structures. Indirect extrusion involves having an additional sacrificial material that usually has certain contrasting physical or chemical properties as the intended hydrogel. The sacrificial material is usually a stable biomaterial mainly used for supportive purposes during bioprinting, after which it is removed, leaving behind the desired scaffold with intended structural networks. Indirect extrusion is largely based on the basis that highly biocompatible bioinks generally have low printability and low mechanical strength before and during printing. Various crosslinking techniques such as chemical cross-linking exists to strengthen scaffolds, but such techniques are usually applied post printing. Therefore, it is difficult to extrude bioinks into desired shapes and structures without adequate support. At this current stage of extrusion-based technique, single bioink printing is insufficient to provide desired mechanical properties. A recent demonstrated using multiple bioinks to fabricate hollow channels, in which these bioinks usually have different cross-linking properties[2]. The bioinks involved in creating hollow channels are usually UV cross-linked while bioinks that are used as the sacrificial material are usually thermo-responsive. Suntornnond R, et al. explained the importance of support material in today’s bioprinting in fabricating complex structures and the need to integrate materials science and chemistry to understand the nature of materials and reaction mechanism[22].

Droplet-based technique typically includes thermal, micro-valve and piezo-electric inkjet printing methods. The bioinks, which can be living cells in culture medium, are deposited as small droplets at any specific pre-determined position[23]. With technological advancement, we are now able to control the size of each droplet with resolutions ranging from ~25 to 300 μ^ Gudapati H, et al. provided a comprehensive review on the application of droplet-based technique on various fields of tissue engineerings such as lung tissues, cardiac tissues, skin tissues and vascular tissues etc. [24]. Dai, et al. recently fabricated endothelialized fluidic channels with a lumen size of approximately 1mm with subsequent generation of capillary networks between channels. The fluidic channels were fabricated by dispensing gelatin using droplet-based technique. Two parallel gelatin tubes was dispensed within a collagen scaffold and human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVECs) with green fluorescent, fibrinogen, thrombin and normal human lung fibroblasts were deposited between the gelatin tubes. Following which, gelatin was sacrificed using thermal reversal to form fluidic channels and perfused with HUVECs with red fluorescent. The concept of angiogenic sprouting, self-assembly and droplet-based technique were applied in this study to induce angiogenesis and vasculogenesis between channels. Sprouting was observed from day 3 at the edge of fluidic channels, and by 14 days post culture, obvious capillary networks were present in collagen networks[25]. Self-assembly of vascular networks is an approach in vascular engineering which would be further discussed in depth below. Thermal inkjet printing method applies small current to a heating element, thus producing a bubble which ruptures to provide pressure pulses for extrusion of droplets via a nozzle[26]. Therefore, droplet size is dependent on frequency of pressure pulses, viscosity of bioink and temperature of heating element. Thermal inkjet is the earliest method in droplet-based technique and most works involve modification of the normal printers that we see at home. Micro-valve inkjet printing is similar to thermal in which instead of using pressure pulses, micro-valve makes use of a magnetic field created by an in-built solenoid coil to open up the valve, thereby producing droplets. A recent review article by Ng WL, et al. provided an in-depth review into the operational considerations for micro-valve inkjet printing such as opening times of valves, printing pressure, nozzle size and bioinks considerations[27]. In addition, they provided an interesting insight into future outlook for micro-valve printing such as the need for improving cell homogeneity in bioinks, post-printing cellular damage and the prospects for hybrid bioprinting. Piezo-electric inkjet printing is the most common used method today whereby a small current is now applied to a piezo-electric device which is typically made up of polycrystalline ceramic. The piezo crystal vibrates when receiving the current, thus creating an internal pressure which allows for the extrusion of droplets via a nozzle[28]. Similarly, droplet-based techniques can be classified into direct and indirect extrusion techniques.

Laser-based technique can be classified into two main categories: cell transfer technology and photopolymerization technology. Cell transfer technology is mainly based on the laser-induced forward transfer effect (LIFT) which consists of a pulsed laser source, a target and a base to collect the printed material. In brief, the target is composed of a base (such as quartz or glass) which is non-absorbing to the laser coated with a thin layer of metal which is absorptive of the laser (such as titanium). After which, cells in culture medium are deposited onto the surface of the metal coated target. The laser pulse then induces vaporization of the metal film, thus causing droplets to form and deposited on the base itself[29]. On the other hand, photo-polymerization technology harness digital micro-mirror devices to polymerize, target and solidify the biomaterial at the irradiated region. The irradiated region and path can be pre-programmed using a simple computer-aided design model. This method is usually a top down bioprinting, in which after completion of each layer, the platform moves down for irradiating and bioprinting of the subsequent levels[30]. Kim, et al. designed a low cost, simple but high resolution printing system that uses visible light cross-linkable bioinks[31]. In this study, the team created a hydrogel using polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA), gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) and eosin Y photo-initiator with NIH 3T3 fibroblasts encapsulation. A commercial projector was used as visible light projection device with a thick water filter to block harmful infrared radiation emitted by the projected. The construct was bioprinted, light treated and subsequently assessed. It was reported that such printing methods brought about higher cellular viability as compared with other extrusion systems, probably due to the absence of nozzle-based extrusion. As compared to UV crosslinking techniques, there was a slight decrease in viability. This might be due to the fact that UV crosslinking requires only about 8 s per layer but visible light crosslinking system takes about 4 min per layer. However, this novel technique was proposed to be safer for maintaining long-term cell functionality due to the absence of UV. A recent extensive parametric study done by Koch L, et al. investigated the effects and inter-connectivity of laser wavelength, pulse duration, pulse energy, focal spot size and laser intensity on different parameters such as droplet volumes and cell viability[32]. It was reported that with shorter wavelengths, less energy was required to print a certain droplet volume. However, this effect can be compensated by increasing laser pulse energy. In short, there was no optimal and best parameters for laser-based technique and that other parameters such as long-term stability or inexpensiveness can be used on case-to-case basis consideration for each study. Although various techniques can be used in fabrication of vascular grafts or vascularized constructs, each technique varies considerably in generating different types of desired constructs. Table 3 provides a general overview of the advantages and disadvantages of the above mentioned methods in vascular engineering.

Table 3.

Advantages and disadvantages of extrusion-based, droplet-based and laser-based technique in bioprinting of blood vessels

| Techniques | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion-based | Direct extrusion-based bioprinting allows fabrication of large scaffolds with high aspect ratios high aspect ratio. Indirect extrusion-based bioprinting allows fabrication of highly complex patterns with sacrificial ink which can be removed to generate lumens for perfusion. | Direct extrusion-based: challenging to bioprint bifurcated vessels. | [33–35] |

| Indirect extrusion-based: fixed height for each layer thus limiting height of sacrificial ink or lumen. Increasing height of sacrificial ink alone might cause occlusion of lumen when removed. | |||

| Current studies have only managed to line lumen with single layers of endothelial cells and is unable to mimic the various layers in native vessels. | |||

| Most studies use hydrogels as their main material which tend to degrade over time thus causing collapse of lumen. | |||

| Studies have shown that cells need to be deposited in certain patterns for efficient vascularization which is something unachievable with extrusion-based technique due to its lack of specificity in cells seeding. | |||

| Droplet-based | It allows for fabrication of high-resolution constructs with co-culture of multiple cell types. | Unable to fabricate large constructs. | [36–38] |

| It allows on-demand ejection of very small droplets of bioink. | Hydrogels with high viscosity of above 0.1 Pa.s-1 easily clogs up nozzle causing low reproducibility, high shear stress and unwanted cellular aggregation. This greatly limits the choice of hydrogels for droplet-based bioprinting. | ||

| Laser-based | It allows for fabrication of constructs with well- defined structures with bifurcated branches. | Unable to achieve sufficient cell density as compared to native composition. | [39–41] |

| Almost zero shear stress related damages to cells as cells are not ejected via nozzles. Thus cell viability is significantly higher when compared to other available techniques. | Requirement of photo-curable bioink limits the choice of available bioink. Photo-initiators are toxic in general which can cause unwanted cellular damage. | ||

| It can be used to print hydrogels with high viscosity. | Effects of constant and prolonged laser irradiation on cells are not yet established. | ||

The ability of bioprinting to generate constructs with well-defined architectures and precise cell deposition has made it a popular choice for fabrication of both vascular graft and vascularized tissue constructs. There are currently three major approaches for fabrication of blood vessels: perfusable scaffolds, self-assembly of vessels and scaffold free biofabrication of autonomous vascular structures.

2.1 Perfusable Scaffolds

During the last decade, a lot of emphasis has been placed on developing 3D models to attempt to mimic invivo native tissue micro-environment. In general, 3D culture systems are an assembly of different cell lines and primary cells into a 3D model with either scaffolds or cell culture plates[42]. There are several existing 3D models currently available and there are some models being developed to model our human organs. Even though each 3D model has its own advantages and disadvantages, generally all 3D models are found to have more similarity to native organs compared to 2D cultures[43]. Therefore, 3D models are deemed as the way ahead for personalized medicine, drug screening and physiological studies of diseases. However, even though such 3D models and arrangements enable cell-cell interactions similar to a native-like micro-environment, there remains a need for vascularization within the organ for general metabolic and physiological functions. With respect to organs like liver whereby it is one of the most perfused organs in the human body, vascularization became an important aspect of liver tissue engineering. In addition, it is reported that blood flow in liver exerts a certain level of shear stress on hepatocytes which causes expression of several genes[44].

The most straightforward approach to perfusable scaffolds is to use extrusion-based technique to biofabricate a network of interconnected channels within the scaffold itself. Early works for extrusion-based technique include using a homemade 3D bioprinter to print bovine aortic endothelial cells in Type I collagen and human fibroblast in Pluronic-F127[45]. In this study, the researchers managed to generate spatially organized constructs with customizable designs such as mimicking the structure of the left anterior descending artery of a pig. A five layered bovine aortic endothelial cells in Type I collagen bioink was biofabricated with the same pattern as found in the angiogram, with maintenance of structural integrity after 35 days of culture. In general, it is reported that extrusion-based technique has the ability to generate viable constructs by depositing various cell types during one extrusion session, of which deposition of endothelial cells or micro-vessels fragments as one of the bioink has the potential of promoting vascular network formations with high viability[46].

With advancement of technology and discovery of novel biomaterials, extrusion-based bioprinting gradually branches out into direct and indirect extrusion. As mentioned, the difference between both techniques is mainly on the usage of another sacrificial biomaterial as additional support. Early works for direct extrusion include using a bottom-up layer-by-layer dual-nozzle bioprinting approach with hepatocytes in gelatin/ alginate/chitosan (GAC) hydrogel and ADSCsin gelatin/ alginate/fibrinogen (GAF) hydrogel. In this study, it is clearly demonstrated that precise control of external parameters such as temperature and pressure is required to maintain printability of hydrogel based largely on the visco-elasticity behavior of the hydrogels. Therefore, with the above knowledge, this team used a digital model to construct a circular biomimetic liver construct with seven vascular channels within the construct. Hepatocytes/GAC was used to construct the main liver component surround the ADSC/GAF vascular channels. After which, the constructs undergo postmodifications with cross-linking agents such as thrombin and calcium chloride solution to allow sol-gel transition for preservation of structural integrity. This pioneering direct extrusion study demonstrated that complex hybrid constructs with distinct spatial organizations are possible and that with proper bioprinting, crosslinking methods and differentiation induction, structural integrity can be maintained for more than two weeks with cellular growth, proliferation and differentiation[47]. A more recent novel direct extrusion bioprinting strategy include using coaxial nozzle concurrently print hollow channel vessel-like cellular micro-fluidic channels[48]. In this study, a triple tube coaxial nozzle was set up with sodium alginate in the outer tube and calcium chloride in the inner tube. At the same time, the scaffold was bioprinted directly into a platform in a container filled with calcium chloride cross linking solution. By controlling the concentration and rate of extrusion, this team was able to allow partial cross-linking in the inner walls of both alginates before allowing the whole extrusion to be immersed into the solution for complete gelation. With this technique, they were able to biofabricate scaffolds with hollow channels and subsequently demonstrated the potential of coaxial nozzles in biofabricating large scale tissue constructs.

However, it is not easy to maintain reproducibility as visco-elasticity of hydrogels tend to vary over time and between batches. Thus there is a need to fine tune printing parameters after every session. A recent strategy for biofabrication of perfusable scaffolds has been largely based on indirect extrusion such as using sacrificial inks[34]. Although indirect extrusion has its own advantages in biofabricating well defined microchannels, it is found that these sacrificial inks tend be associated with cytotoxic by-products after post dissolution treatment of sacrificial inks. For instance, high concentrations of Pluronic-F127 is found to have significant cytotoxic effects on cells[49]. Regardless, we can see increasing novel reports of indirect extrusion techniques with naturally derived or artificial sacrificial inks. There are several criterions that the sacrificial ink must meet before it can be used with the main bioink[2]. Firstly, the inks must be compatible with one another during printing under ambient condition. Secondly, the cells in the bioink and its structural integrity must not be altered or change during printing or removal of sacrificial ink. Inks that require harsh printing parameters or require harsh removal techniques are not suitable. A recent study exploited the unique physical and shear-thinning properties of Pluronic-F127 and different concentrations of cell laden GelMAto biofabricate 3D perfusable scaffolds. A final four layered scaffold was produced in a layer-by-layer wise manner by co-printing different inks through 200μm nozzles, followed by photo-crosslinking of GelMA and removal of sacrificial Pluronic-F127. It was reported that high fidelity vascular channels with customizable designs can be fabricated with such a method and these channels can be easily endothelized and perfused with cell culture media. Even though the various cells encapsulated in the GelMA hydrogel had an initial decrease in viability (60–70% cell viability), it was also reported that the printed cells proliferated over a course of one week and were comparable to cell viability of the control groups (~82% cell viability). The authors suggested that the initial decrease in cell viability could be attributed to shear stress exerted on the cells during the printing process, which is also in consistence with reports and observations made by other studies[50]. Another recent study that uses similar technique biofabricated a thrombosis-on-a-chip model with cell laden GelMA and Pluronic-F127 as the sacrificial ink[51]. Similarly, this study demonstrated that vascular channels can be biofabricated and endothelized using this method. Further studies had also demonstrated that a thrombosis and thrombolytic situation can be simulated in this model and initial results showed that fibroblasts encapsulated in the GelMA hydrogels migrated to the area of the clots and deposited collagen I locally, which is a similar phenomenon seen in humans.

A similar study by Suntornnond R, et al. combined Pluronic-F127 with GelMA to form Plu-GelMA for bioprinting of constructs[52]. NMR results showed the presence of methacrylate groups, thus making Plu- GelMA both thermo-responsive and photo-crosslinkable. In this study, it was reported that simple hollow cylindrical structures of 50 layers and mluti-layered structures can be printed with 2:1 Plu-GelMA without any external structural support. However, structural support and dual-nozzle system were required for more complex structures. In addition, Plu-GelMA were nontoxic to L292 cells with 2:1 Plu-GelMA having the highest cell viability and proliferation as compared to others. It might be due to the higher concentration of Pluronic-F127 which causes higher swelling rate and well defined pores which allowed better diffusion of nutrients and provided more surface area for cellular attachment. In addition, 2:1 Plu-GelMA were shown to be a good platform for cellular differentiation. HUVECs cultured in 2:1 Plu-GelMA showed signs of differentiation with expression of CD31 and VWF, both markers of endothelium cells. Also, HUVECs were shown to attach and spread on the construct surface 1 day after culturing and by day 7, HUVECs had fused and covered the construct with extracellular matrix.

In a related procedure but using a naturally derived polysaccharide agarose as the sacrificial ink and GelMA as the main biomaterial. In this study, the authors first printed the vascular channels with agarose gel before casting GelMA to fully cover the agarose fibers, followed by exposing the whole scaffoldto UV light for photo-crosslinking. GelMA undergo cross-linking via free-radical photo-polymerization of acrylate groups, thus were unable to form covalent bonds with the agarose fibers. Because of this, agarose fibers could be easily removed by pulling them out of the scaffolds, thus forming perfusable micro-channels without the need for any additional dissolution process[53]. It was further reported that such a method prevents unnecessary osmotic damage to encapsulated cells and further prevents interactions of dissolved sacrificial material that could potentially modify the structural properties of the main scaffoldsas reported by others[54]. Interestingly, this study studied on the feasibility of endothelization within the micro-channels and that seeding of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) and formation of endothelial mono-layers were found to be significantly faster in larger channels of 1000 μm and 500 μm as compared to narrower channels of 250 μm. In addition, it was reported that 250 μm has the lowest perfusion capability as compared to the rest of the larger channels. Most critically, it was reported that mouse calvarial pre-osteoblasts cells (MC3T3) that were encapsulated in constructs with micro-channels had significantly higher cellular viability at days 1 and 7, as well as significantly higher differentiation as determined by alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) levels on day 14. On the other hand, MC3T3 encapsulated in constructs with no micro-channels only showed 60% cell viability at the same time points. This result is consistent with other similar vascularization studies fabricated via selfassembly of endothelial cells which also demonstrated enhanced tissue functionality which would be further discussed below.Droplet-based indirect extrusion was also used in biofabricating perfusable scaffolds. Using the micro-valve bioprinting technique, this team successfully bioprinted gelatin (sacrificial ink) into a cylindrical shape structure before depositing cell laden hydrogels over it. Post modification involves removal of gelatin via thermal de-crosslinking, leaving behind a tubular channel which was subsequently endothelized and perfused[55]. It was demonstrated that the vascular channels were covered a monolayer of confluent endothelial cells and this structure was stable for a period of two weeks with constant perfusion. In addition, the vascular channels were able to support and maintain the viability of adjacent cells with barrier effect against plasma proteins and high molecular weight molecules.

2.2 Self-assembly Approach

An alternative approach to generating vascular constructs lies in endothelial cells’ abilities to selforganize into blood vessels. The main difference between self-assembly approach and tissue engineering approach is that for self-assembly approach, cells are often left and cultivated to form tubular channels whilst for tissue engineering approach, tubular channels are instantaneously available after bioprinting and modification. Therefore, the main problem in selfassembly approach is the direct control over distribution and growth of vascular channels. For instance, oxygen as we know is vital for cellular survival, regulation, differentiation and metabolism etc.[56]. In response to in-vivo hypoxia, our bodies activate and produce hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) that accumulates and subsequently activate expression of various genes and cascades. A key function of HIFs is the regulation in expression of angiogenic genes that promote vasculogenesis. An interesting published study applied the vast knowledge of hypoxia and fabricated a hypoxiainducible gelatin-ferulic acid hydrogel. It is reported that the authors were able to specifically control the oxygen levels within the hydrogels, thus was able to promote invitro tubulogenesis of endothelial-colony-forming- cells by activating HIFs with subsequent in-vivo promotion of blood vessels recruitment and infiltration[57].

With the emergence of bioprinting, it is expected that pre-placement or directed cell deposition can aid in directing and controlling distribution and direction of vascular channels. Droplet-based direct extrusion was also used to biofabricate construct with micro-channels by the self-assembly method. Early works include modification of a home-based thermal inkjet printer (Hewlett Packard HP500). Droplets volume of 130 picoliter (pL) of human micro-vascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) and fibrin were simultaneously deposited via 50 nozzles on the printer head. At the same time, fibrinogen, thrombin and calcium ions were used for rapid gelation of constructs after printing[35]. Even though there were no clear structural integrity after 14 days of culture, results demonstrated that the printed endothelial cells were able to proliferate and form a confluent lining along the fibrin scaffold after 21 days of culture with distinct tubular integrity.

A novel self-assembly method to biofabricate autonomous vascular structures was reported using a single-step process approach. A sheet of tissue was produced by culturing smooth muscle cells along with fibroblasts on a gelatin-coated tissue culture plate. After which, the sheet was rolled onto a tubular support thus forming a vascular tubular construct with an internal smooth muscle layer and an external fibroblast layer which attempts to mimic the structure of tunica media and tunica adventitia. In this study, it was reported that such a self-assembly approach was able to generate vascular constructs with significant mechanical properties based on the types of fibroblasts used. Selfassembly approach allowed the smooth muscles cells and fibroblasts to produce extra-cellular matrix which helps in determining mechanical properties of assembled vascular construct. For instance, constructs with dermal fibroblast were shown to have denser and more compact extra-cellular matrix, thus resulting in higher mechanical strength and burst pressure[58]. The authors mentioned that even though tunica intima was not fabricated in this study, it is of importance to note that endothelial cells do play a role in regulating final mechanical property of construct as endothelial cells are known to secrete transforming growth factors that promotes tissue homeostasis and regulates extra-cellular matrix degradation and production[59].

Laser-based techniques are also a common technique used in self-assembly method as it allows specific deposition of individual cells. Early work had demonstrated that such technique allowed cells to be printed individually suspended in 108 cells/ml viscous hydrogel consisting of glycerol and sodium alginate. In addition, laser-based techniques have the fastest printing speed amongst all the other techniques, thus minimizing unnecessary damage to the cells[60]. In this study, the authors demonstrated the ability of laser-based technique to bioprint two distinct concentric circles of human endothelial cells and showed that different cell types can be printed in close proximity to one another with high cell concentration and according to desired pattern. Another study exploited the advantages of laserbased techniques and fabricated branch-stem structures of HUVEC and human umbilical vein smooth muscle cells (HUVSMC)[61]. By depositing cells in a branchstem structure, initial results showed that HUVSMC tend to cluster together when deposited individually whilst HUVEC can be directed and guided to form lumen networks within a day. However, pure HUVEC lumens have limited stability which could be augmented by depositing HUVSMC alongside the HUVEC layer. Therefore, this study demonstrated that a certain level of artificial guidance, coupled with self-assembly of cells, could be the way ahead for fabrication of vascular constructs.

In-vivo studies of implanted cardiac patches into rats that underwent myocardial infarction showed enhanced angiogenesis in the borders of infarction as well as formation of functional vascular networks in the patch[62]. Previously, it was found to be challenging to fabricate viable vascular constructs for implantation as newly formed vessels tend to be immature and unstable. In addition, it was reported that co-culturing of HUVEC and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) could enhance stability of newly formed vessels. With laserbased technique, HUVECs and MSCs could now be printed in close proximity to each other in an intended design. The construct was then cultured for eight days to allow production of extra-cellular matrix and selfassembly of cells before implantation. Post-implantation results showed that angiogenesis and functional neovascularization were enhanced significantly in the infarction area.

A recent study by Kim BS, et al. demonstrated the effects of micro-environment on neovascularization. Bioprinted large skin constructs with ADSCs and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in decellularized extracellular matrix of skin showed faster and enhanced vasculogenesis via the self-assembly technique[63]. This group of constructs showed significantly higher number CD31+ vessels as compared to cell-free scaffolds and ADSCs with EPCs without scaffolds. In addition, such 3D printed constructs were found to have subsequently higher level of blood perfusion on laser Doppler perfusion imaging technique. This study showed the importance of micro-environment. Sole reliance on cell based therapy is insufficient in promoting vasculogenesis. Therefore, micro-environment plays a huge role in inducing self-assembly of vessels.

2.3 Autonomous Vascular Structures

Since the emergence of tissue engineering, most strategies had generally revolved around scaffold based engineering whereby cells are usually encapsulated in bio-inks. In the initial years, scaffolds were thought to be only providing cells with temporary support for cell growth. However, scaffolds have since evolved to be a critical factor in tissue engineering. Scaffolds are thought to resemble the “extra-cellular matrix” of native micro-environment and certain structural properties of scaffolds are reported to be able to influence cellular differentiation into certain cell lines by providing biological, chemical and mechanical cues[64]. Even though there are certain level of clinical translation of scaffold based vascular engineering, there are still some unsolved challenges limiting complete clinical implementation. Firstly, there are currently no known biomaterial that have these following characteristics: no or low induced inflammatory response in host, degradation rates that are synchronous with tissue or vascular formations, degraded by-products that are nontoxic and similar mechanical properties as native tissues. Secondly, even after much research, we are still not able to create the ideal structural properties of scaffolds that are able to mimic the native extra-cellular matrix which plays a huge role in determining cellular activities. These challenges have led to increasing interest into fabrication of autonomous vascular structures without scaffolds. On the other hand, such studies have revealed some potential into small diameter blood vessel graft as we are now able to biofabricate models with distinct tunica layers and high mimicry[65].

A multi-nozzle extrusion-based technique was used to biofabricate a concentric alginate based tubular construct. In this study, a nozzle of alginate-xanthum gum hydrogel was used to bioprint a 6 mm concentric scaffold with another nozzle dispensing calcium chloride into the internal surface of the alginate-xanthum gum scaffold. As discussed by the authors, the challenge of bioprinting autonomous vascular scaffolds lie in finding the proper concentration and viscosity of hydrogels that has sufficient mechanical strength to support the weight of the entire structure[66]. Other than properties of biomaterials, this study explored the effects of printing parameters such as extrusion speed, nozzle diameter, pressure, thickness of wall and number of layers so as to optimize future bioprinting processes.

Droplet-based direct extrusion was also used in biofabricating autonomous vascular structures. Early works include using of a modified thermal ink-jet printer to eject 30 to 50 μm droplets of smooth muscle cells encapsulated in sodium alginate into calcium chloride solutions. Alginate tubes with encapsulated smooth cells were biofabricated with maintenance of cell phenotype, even distribution of cells, cell growth with 80% viability after 18 days of culture. Interestingly, to evaluate the functionality of their bioprinted constructs, the authors conducted a vasomotor reactivity test by exposing the constructs to the vaso-constricting agonist Endothelin-1. Their results showed that the constructs contracted in a dose-dependent manner with complete closure of lumen after 43 hours of exposure to 50 nM of Endothelin-1[67]. In addition, the constructs showed dilation of lumen after removal of agonists. Even though it is difficult to make a direct comparison between these results and native vessels or other vascular engineered constructs, it paved the way ahead for vascular tissue engineering and demonstrated that the challenge lies in design of functional tissues and that droplet-based direct extrusion technique might be a possible solution to solving these problems. Working on similar principles, a team used a static-electricity actuated ink jet system with modified ink jet heads to dispense downsized micro alginate beads of approximately 25 μm in size. This method allowed superior control in fabricating 35-40 μm wall thickness and 30-200 μm internal diameter fine tubular constructs. In this study, the authors demonstrated that droplet-based direct extrusion of scaffold free vascular constructs is a promising alternative to overcoming limitations faced by scaffold-based engineering and such a method has the potential to biofabricate fine vascular structures with precise internal architectures[68].

A recent novel study developed a triple tunica layered perfusable vascular-like structure using a self-made microfluidic platform, two concentric stainless steel needles and cell laden GelMA. Fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells were suspended in GelMA hydrogel. Fibroblasts-GelMA were pipetted into the outer concentric ring (between larger needle and wall of platform) and cross-linked with UV light before removal of the larger needle. This led to the formation of tunica adventitia-like vascular structure. Tunica media was formed using the same method before having HUVEC endothelized the internal lumen of tunica media to form the tunica intima[69]. Cell viability and adherence were consistent with other related GelMA studies. Even though 4 to 16% concentrations of GelMA displayed varying compressive modulus ranging from 3.1 kPa to 138 kPa with failure stress ranging from 43 kPa to 175 kPa, these values are far from the values from native vessels, which typically have their values in the MPa range.

3. Future Perspectives

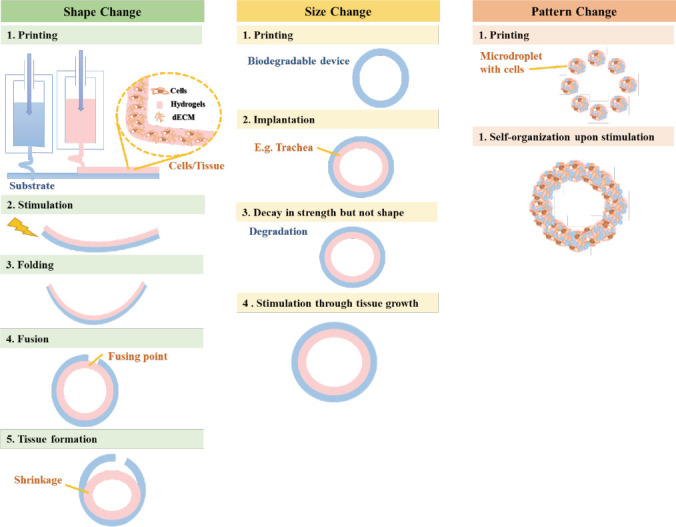

The fact that metabolizing cells require continuous supply of nutrients and oxygen in order to remain viable has inspired many researchers to incorporate an artificial vascular system in a bioengineered tissue construct. However, generation of a stable and viable vascular network still remains a huge challenge in the tissue engineering field due the complexity of vascular architecture. 3D bioprinting has certainly emerged as a potential candidate for vascular tissue engineering. Even though numerous studies have reported biofabricating biomimetic vascularized tissue constructs using 3D bioprinting technology, we are still far from clinical applications of biofabricated vessels. Most constructs do not have the mechanical and physical properties to fully replace native blood vessels. Even though we are able to replicate the general concentric triple tunica structure with their respective cellular constituents, our current pool of natural biomaterials is not able to meet the mechanical and physical requirements of native vessels. There remains a need to balance modification of biomaterials, toxicity and degradability of biomaterials. On the other hand, we have to note that native vasculature is multi-scalar in nature from the large arteries to the sub-micron capillaries and to the venous systems. However, with our current bioprinting technologies, it is very challenging to print sub-micron capillaries. In addition, vascular networks in our body do not function independently. Nerve supply networks are intimately connected to our vascular systems and has a role to play in physiological control of vessels. With the emergence of 4D bioprinting, future focus would certainly be shifted to creating implantable organs with complete vascular networks or implantable vascular grafts. This may be possible by using a technology that has emerged recently, 4D bioprinting, where “time” is integrated with 3D bioprinting as the fourth dimension. In 4D bioprinting, the printed constructs are able to evolve over time after being printed, alter their shapes and functionalities in response to external stimuli[70]. As bioprinting of vascularized tissue advances, the preservation and culture of tissues would be a focus in the future for accurate pre-operation conditioning and the transplanted bioprinted constructs would be expected to remain integrated with the vascular system of the recipient post-operation, without collapsing or obstruction. However, 4D bioprinting is still more of a hypothesis and is waiting to be validated. Figure 2 provides a simple overview on the three methods employed in 4D bioprinting[71].

Figure 2.

Methods employed in 4D bioprinting[71].

Currently, there might be more potential for vascularized constructs to be used for in vitro disease model studies or drug screening studies. However, despite all these facts, currently there is no definite evaluation criteria for tissue-engineered blood vessels and hence it is hard to compare between different bioengineered models and designs. Therefore, there is a need to develop standard evaluation criteria in order to improve our common understanding and to work towards a common standard. There are numerous novel approaches in overcoming some of the problems that we are facing currently. One approach would be bottomup fabrication, which includes the manufacture of minitissue constructs as building blocks and joining them together, forming a tissue construct with clinicallyrelevant volumes. A new kind of scalable bioink, “tissue strands”, for scaffold-free bioprinting was introduced recently. These tissue strands are bioprintable and can facilitates rapid fusion and maturation through selfassembly without the need of a support moulding structure nor a liquid delivery medium during extrusion. These unique characteristics enable scale-up constructs and may one day enable the integration of macro-scale vascular networks in bottom-up fabrication which would be a promising tool in obtaining vascularized tissue with clinically-relevant size in the future[72]. Another popular approach is the utilization of decellularized matrix as bioink for the fabrication of biomimetic tissue constructs. Since decellularized matrix is derived from native tissue’s own scaffold, it is believed to be closer in relation to native tissue and thus is able better mimic the anatomical and functional features of the native microenvironment, providing tissue-specific cellular cues that are required to enhance overall cell viability and organization as well as functionality[65]. Advances in vascular and tissue engineering could provide a potential source for grafts and solve the problems in autologous and homologous transplants. As we are able to fabricate larger and larger vascular constructs and autonomous vascular structures, there is also a need to consider the need for anastomosis between bioprinted vessels and existing vessels. Vascularized constructs need to have these two components for successful host-implant anastomosis: (1) hierarchy of vessels with different lumen sizes that are approximately within 200 μm of one another to provide sufficient diffusion to surrounding cells and (2) well defined vascular geometry such as branching pattern and angle to match the metabolic profile of native tissues[73]. For autonomous vascular structures of certain sizes, it is possible for surgical anatomosis and suturing of fabricated vessels with host. Zhang B, et al. successfully fabricated vascular construct and connected them to femoral vessels on the hind limbs of adult rats with surgical cuffs. Perfusion was established immediately after surgery and it was reported that the vessels remained clot-free up till one week after surgery. In addition, native angiogenesis was also reported to be observed around the implant with endothelial cells subsequently coating the lumen in the implants[74]. Such surgeries might be more invasive than traditional treatment methods. In addition, surgical anastomosis is only available for vascular structures that are of a certain size with equivalent mechanical properties to withstand pulsatile nature of blood flow and stretch. Vascular constructs with micro-vessels often has to rely on natural anastomosis induced by host or construct. These vessels are often too small and numerous to be directly sutured. Song, et al. recently published an in depth review on the natural anastomosis mechanisms that were currently proposed: (1) effects of cellular and biomolecular compositions, (2) effects of vascular architectures, (3) establishment of cell-cell contact via adherin and tight junctions, (4) polarization of fused tip cells and (5) blood pressure driven invagination of apical membranes[75]. In short, even though there were reported articles on the positive effects of high density fibroblasts or fibroblast on anastomosis, most of these studies were stand-alone studies with unclear understanding of the exact mechanisms[76,77]. Further investigations from different professionals are required to piece the missing information and provide future potential strategies for host-implant anastomosis.

4. Conclusion

Since the last decade, significant advances have been made in respect to bioprinting of artificial blood vessels. Despite having several positive results in the generation of functional vascular tissue, there are still obstacles to be solved if we want to biofabricate clinically-relevant constructs. There is increasing needs for vascular grafts and vascular engineering is deemed as the potential way ahead for replacing autologous and homologous grafting. Continued innovation and advancements in vascular engineering, vascular biology, nanotechnology, material science and bioprinting are required to motivate interests in vascular engineering to push for future clinical translation of fabricated constructs or vascular structures. Production time of a vascular graft used to take 6 to 9 months due to the need of culturing fibroblast sheets. But with the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells and its enhanced proliferation, production of a vascular graft now only requires 6 to 8 weeks of culture time and eliminates the need for harvesting of stem cells from patients[78]. Bioprinting has come a long way with the development of newer technology and development of novel hydrogel for different technologies and applications. However, to take bioprinting further into the future, there is a need to create common evaluation criteria for vascular engineering. There are currently no standards to conduct comparisons between different models and designs. Therefore, there is a need for creation of a standard criteria for common basic understanding and testing of products to promote improvement. In addition, development of a computational model for predicting of bioinks characteristics would be highly advantageous in the long run. Hölzl K, et al. presented a simple model to estimate the mechanical properties of hydrogels containing different cell densities and distributions[79]. Such a model can be extended to incorporate complex 3D architectures to generate hydrogels with appropriate mechanical properties and micro-environment. As mentioned in the above section, micro-environment alone has a major impact in inducing cellular differentiation. Application of mathematical algorithm could also be applied into vascular engineering. One such study applied an algorithm of computational geometry for construction of smooth junctions for bioprinting[80]. Computational fluid dynamics was used to compare shear wall stress and blood velocity field for junctions of different designs and this applied knowledge was used to form a design method for vascular engineering.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive review into the different 3D printing techniques and the various approaches commonly used in vascular engineering to supply useful strategies for blood vessel engineering development and innovation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge receipt of a grant from China Medical University Hospital grants (DMR-107-070) and the National Science Council grants MOST (106-2632- E-468-001) of Taiwan.

Author contributions

Yu-Fang Shen conceived the ideas and organized the main content; Hooi Yee Ng and Kai-Xing Alvin Lee wrote the content; Che-Nan Kuo contributed some detailed techniques.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Marro A, Bandukwala T, Mak W. Three-dimensional printing and medical imaging:A review of the methods and applications. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2016;45(1):2–9. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.07.009. https:// doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolesky D B, Truby R L, Gladman A S, et al. 3D bioprinting of vascularized, heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Adv Mater. 2014;26(19):3124–3130. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305506. https://doi. org/10.1002/adma.201305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller J S, Stevens K R, Yang T, et al. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat Mater. 2012;11(9):768–774. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pashneh-Tala S, MacNeil S, Claeyssens F. The tissueengineered vascular graft—past, present, and future. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2015;22(1):68–100. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2015.0100. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten. teb.2015.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dall'Olmo L, Zanusso I, DiLiddo R, et al. Blood vessel-derived acellular matrix for vascular graft application. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:6–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/685426. https://doi. org/10.1155/2014/6⅞6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Wang X. Creation of a vascular system for organ manufacturing. Int J Bioprinting. 2015;1(1):77–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.18063/IJB.2015.01.009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao X, Liu L, Wang J, et al. In vitro vascularization of a combined system based on a 3D printing technique. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;10(10):833–842. doi: 10.1002/term.1863. https://doi. org/10.1002/term.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criswell T L, Corona B T, Wang Z, et al. The role of endothelial cells in myofiber differentiation and the vascularization and innervation of bioengineered muscle tissue in vivo. Biomaterials. 2013;34(1):140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.045. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W J, Liu W, Cui L, et al. Tissue engineering of blood vessel. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11(5):945–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00099.x. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berillis P. The role of collagen in the aorta's structure. Open Circ Vasc J. 2013;6:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoch E, Tovar G E M, Borchers K. Bioprinting of artificial blood vessels:Current approaches towards a demanding goal. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2014;46(5):767778. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu242. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezu242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stegemann J P, Kaszuba S N, Rowe S L. Review:Advances in vascular tissue engineering using protein-based biomaterials. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(11):2601–2613. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0196. https://doi. org/10.1089/ten.2007.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozbolat I T, Moncal K K, Gudapati H. Evaluation of bioprinter technologies. Addit Manuf. 2017;13:179–200. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jungst T, Smolan W, Schacht K, et al. Strategies and molecular design criteria for 3D printable hydrogels. Chem Rev. 2016;116(3):1496–1539. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00303. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs. chemrev.5b00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalil S, Sun W. Bioprinting endothelial cells with alginate for 3D tissue constructs. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131(11):111002. doi: 10.1115/1.3128729. https://doi.org/10.1115/L3128729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levato R, Visser J, Planell J A, et al. Biofabrication of tissue constructs by 3D bioprinting of cell-laden microcarriers. Biofabrication. 2014;6(3):035020. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/3/035020. https://doi. org/10.1088/1758-5082/6/3/035020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens C M, Marga F, Forgacs G, et al. Biofabrication and testing of a fully cellular nerve graft. Biofabrication. 2013;5(4):045007. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/4/045007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1758-5082/5/4/045007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Y, Ozbolat I T. Tissue strands as “bioink”for scaleup organ printing. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014;2014:1428–1431. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2014.6943868. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2014.6943868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozbolat I T, Hospodiuk M. Current advances and future perspectives in extrusion-based bioprinting. Biomaterials. 2016;76:321–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.076. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.biomaterials.2015.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drury J L, Mooney D J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering:Scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4337–4351. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed E M. Hydrogel:Preparation, characterization, and applications:A review. J Adv Res. 2015;6(2):105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suntornnond R, An J, Chua C K. Roles of support materials in 3D bioprinting. Int J Bioprinting. 2017;3(1):83–86. doi: 10.18063/IJB.2017.01.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.18063/IJB.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendriks J, Willem Visser C, Henke S, et al. Optimizing cell viability in droplet-based cell deposition. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep11304. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gudapati H, Dey M, Ozbolat I. A comprehensive review on droplet-based bioprinting:Past, present and future. Biomaterials. 2016;102:20–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.biomaterials.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee V K, Lanzi A M, Ngo H, et al. Generation of multi-scale vascular network system within 3D hydrogel using 3D bio-printing technology. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2014;7(3):460–472. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0340-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12195-014-0340-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui X, Boland T, D'Lima D D, et al. Thermal inkjet printing in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2012;6(2):149–155. doi: 10.2174/187221112800672949. https://doi. org/10.2174/1−1112800672949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng W L, Lee J M, Yeong W Y, et al. Microvalvebased bioprinting process, bio-inks and applications. Biomater Sci. 2017;5(4):632–647. doi: 10.1039/c6bm00861e. https://doi.org/10.1039/ c6bm00861e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.deJong J, deBruin G, Reinten H, et al. Air entrapment in piezo-driven inkjet printheads. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;120(3):1257–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keriquel V, Oliveira H, Rémy M, et al. In situ printing of mesenchymal stromal cells, by laser-assisted bioprinting, for in vivo bone regeneration applications. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1778. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01914-x. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01914-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selimis A, Mironov V, Farsari M. Direct laser writing:Principles and materials for scaffold 3D printing. Microelectron Eng. 2014;132:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, Abdulla R, Parker B, et al. A simple and high-resolution stereolithography-based 3D bioprinting system using visible light crosslinkable bioinks. Biofabrication. 2015;7(4):045009. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/7/4/045009. https://doi.org/10.1088/17585090/7/4/045009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch L, Brandt O, Deiwick A, et al. Laser-assisted bioprinting at different wavelengths and pulse durations with a metal dynamic release layer:A parametric study. Int J Bioprinting. 2017;3(1):42–53. doi: 10.18063/IJB.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y. 3D bioprinting of vasculature network for tissue engineering thesis, Iowa Research Online. University of Iowa. 2014:1–135. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu W, Deconinck A, Lewis J A. Omnidirectional printing of 3D microvascular networks. Adv Mater. 2011;23(24):H178–183. doi: 10.1002/adma.201004625. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201004625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui X, Boland T. Human microvasculature fabrication using thermal inkjet printing technology. Biomaterials. 2009;30(31):6221–6227. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.056. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.biomaterials.2009.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blaeser A, Duarte Campos D F, Weber M, et al. Biofabrication under fluorocarbon:A novel freeform fabrication technique to generate high aspect ratio tissueengineered constructs. Biores Open Access. 2013;2(5):374–384. doi: 10.1089/biores.2013.0031. https://doi.org/10.1089/biores.2013.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang J, Yi H-G, Cho D-W. 3D printed tissue models:Present and future. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;2(10):17221731. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tasoglu S, Demirci U. Bioprinting for stem cell research. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.10.005. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillemot F, Souquet A, Catros S, et al. Laser-assisted cell printing:Principle, physical parameters versus cell fate and perspectives in tissue engineering. Nanomedicine. 2010;5(3):507–515. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams C G, Malik A N, Kim T K, et al. Variable cytocompatibility of six cell lines with photoinitiators used for polymerizing hydrogels and cell encapsulation. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2005;26(11):1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.024. https://doi. org/10.2217/nnm.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandrycky C, Wang Z, Kim K, et al. 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(4):422–434. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bovard D, Iskandar A, Luettich K, et al. Organs-on-achip. Toxicol Res Appl. 2017;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pampaloni F, Reynaud E G, Stelzer E H K. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(10):839–845. doi: 10.1038/nrm2236. https://doi. org/10.1038/nrm2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torii T, Miyazawa M, Koyama I. Effect of continuous application of shear stress on liver tissue:Continuous application of appropriate shear stress has advantage in protection of liver tissue. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(10):45754578. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.10.118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.10.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith C M, Stone A L, Parkhill R L, et al. Threedimensional bioassembly tool for generating viable tissueengineered constructs. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(9-10):1566–1576. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1566. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.2004.10.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koike N, Fukumura D, Gralla O, et al. Creation of long-lasting blood vessels. Nature. 2004;428(6979):138–139. doi: 10.1038/428138a. https://doi.org/10.1038/428138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li S, Xiong Z, Wang X, et al. Direct fabrication of a hybrid cell/hydrogel construct by a double-nozzle assembling technology. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2009;24(3):249265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883911509104094. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao Q, He Y, Fu J, zhong, et al. Coaxial nozzleassisted 3D bioprinting with built-in microchannels for nutrients delivery. Biomaterials. 2015;61:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.031. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khattak S F, Bhatia S R, Roberts S C. Pluronic F127 as a cell encapsulation material:Utilization of membranestabilizing agents. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(5-6):974–983. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.974. https://doi. org/10.1089/ten.2005.11.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith C M, Christian J J, Warren W L, et al. Characterizing environmental factors that impact the viability of tissue-engineered constructs fabricated by a direct-write bioassembly tool. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(2):373–383. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0101. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.2006.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y S, Davoudi F, Walch P, et al. Bioprinted thrombosis-on-a-chip. Lab Chip. 2016;16(21):4097–4105. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00380j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suntornnond R, Tan E Y S, An J, et al. A highly printable and biocompatible hydrogel composite for direct printing of soft and perfusable vasculature-like structures. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16902. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17198-0. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-01717198-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bertassoni L E, Cecconi M, Manoharan V, et al. Hydrogel bioprinted microchannel networks for vascularization of tissue engineering constructs. Lab Chip. 2014;14(13):2202–2211. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00030g. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4lc00030g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skaat H, Ziv-Polat O, Shahar A, et al. Magnetic scaffolds enriched with bioactive nanoparticles for tissue engineering. Adv Healthc Mater. 2012;1(2):168–171. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201100056. https://doi. org/10.1002/adhm.201100056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee V K, Kim D Y, Ngo H, et al. Creating perfused functional vascular channels using 3D bio-printing technology. Biomaterials. 2014;35(28):8092–8102. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.083. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Covello K L, Simon M C. HIFs, hypoxia, and vascular development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;62:37–54. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)62002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park K M, Gerecht S. Hypoxia-inducible hydrogels. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4075. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5075. https://doi.org/10.1016/S00702153(04)62002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gauvin R, Ahsan T, Larouche D, et al. A novel singlestep self-assembly approach for the fabrication of tissueengineered vascular constructs. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(5):1737–1747. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0313. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sales V L, Engelmayr G C, Mettler B A, et al. Transforming growth factor-βΐmodulates extracellular matrix production, proliferation, and apoptosis of endothelial progenitor cells in tissue-engineering scaffolds. Circulation. 2006;114(1):I193–I199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001628. https://doi.org/10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guillotin B, Souquet A, Catros S, et al. Laser assisted bioprinting of engineered tissue with high cell density and microscale organization. Biomaterials. 2010;31(28):7250–7256. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu P K, Ringeisen B R. Development of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) and human umbilical vein smooth muscle cell (HUVSMC) branch/ stem structures on hydrogel layers via biological laser printing (BioLP) Biofabrication. 2010;2(1):014111. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/1/014111. https://doi. org/10.1088/1758-5082/2/1/014111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaebel R, Ma N, Liu J, et al. Patterning human stem cells and endothelial cells with laser printing for cardiac regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011;32(35):9218–9230. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.071. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim B S, Kwon Y W, Kong J-S, et al. 3D cell printing of in vitro stabilized skin model and in vivo pre-vascularized skin patch using tissue-specific extracellular matrix bioink:A step towards advanced skin tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2018;168:38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.03.040. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.biomaterials.2018.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]