Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate outcomes by sex in older adults with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction (AMI-CS).

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective cohort of older (≥75 years) AMI-CS admissions during January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2014, was identified using the National Inpatient Sample. Interhospital transfers were excluded. Use of angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), mechanical circulatory support (MCS), and noncardiac interventions was identified. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality stratified by sex, and secondary outcomes included temporal trends of prevalence, in-hospital mortality, use of cardiac and noncardiac interventions, hospitalization costs, and length of stay.

Results:

In this 15-year period, there were 134,501 AMI-CS admissions 75 years or older, of whom 51.5% (n=69,220) were women. Women were on average older, were more often Hispanic or nonwhite race, and had lower comorbidity, acute organ failure, and concomitant cardiac arrest. Compared with older men (n=65,281), older women (n=69,220) had lower use of coronary angiography (55.4% [n=35,905] vs 49.2% [n=33,918]), PCI (36.3% [n=23,501] vs 34.4% [n=23,535]), MCS (34.3% [n=22,391] vs 27.2% [n=18,689]), mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis (all P<.001). Female sex was an independent predictor of higher in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02–1.08; P<.001) and more frequent discharges to a skilled nursing facility. In subgroup analyses of ethnicity, presence of cardiac arrest, and those receiving PCI and MCS, female sex remained an independent predictor of increased mortality.

Conclusion:

Female sex is an independent predictor of worse in-hospital outcomes in older adults with AMI-CS in the United States.

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) continues to be a leading cardiovascular emergency and continues to be associated with high mortality in older adults in the United States.1–6 Compared with an overall prevalence of less than 5% in all-comers with AMI, cardiogenic shock (CS) is more frequent in the older adult population.2,7–10 Despite the widespread use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and improvements in the delivery of acute cardiovascular care, AMI-CS in older adults is associated with in-hospital mortality in excess of 50% in the contemporary era.3 Older adults have been infrequently studied in AMI-CS studies, perhaps due to the perceived lack of benefit from revascularization in the seminal SHOCK (Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock) trial.11 Older adults constitute a vulnerable population due to a combination of comorbid conditions, polypharmacy, and bleeding risks resulting in poor overall outcomes.12

In addition to age-associated health care disparities, older patients frequently face challenges due to other demographic factors, such as race/ethnicity, sex, and gender, which is seen across all age groups.13–15 Prior research in the field of health care delivery has shown pervasive sex and gender disparities in acute cardiovascular care.16,17 It is conceivable that similar disparities exist in older adults presenting with AMI-CS; however, there is a paucity of data in this field.18 Older women frequently present at an older age, with atypical symptoms and more high-risk presentations than men.19 This study sought to assess the disparities by sex in the clinical outcomes of older patients (aged ≥75 years) admitted with AMI-CS. We hypothesized that female sex would be associated with lower use of evidence-based therapies and worse in-hospital outcomes. Furthermore, we hypothesized that these differences would be associated with worse outcomes across subgroups stratified by race/ethnicity, type of AMI, and illness severity.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Population, Variables, and Outcomes

The National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) is the largest all-payer database of hospitalized inpatients in the United States. The NIS contains discharge data from a 20% stratified sample of nonfederal hospitals and is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.20 For each admission to the hospital, the NIS database includes demographic characteristics, primary payer, hospital characteristics, principal diagnosis, up to 24 secondary diagnoses, and procedural diagnoses. The details of this database and methodology used by our group have been described previously.2,4–9,21–29

Using HCUP-NIS data from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2014, a retrospective cohort study of admissions with AMI-CS 75 years and older were identified. AMI in the primary procedure field was identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI; ICD-9-CM codes 410.1x-410.6x, 410.8x, and 410.9x) and non-STEMI (ICD-9-CM codes 410.70–410.79).30 Cardiogenic shock was identified using ICD-9-CM code 785.51 and was defined as shock resulting from diminution of cardiac output in heart disease; shock resulting from primary failure of the heart in its pumping function, as in myocardial infarction, severe cardiomyopathy, or mechanical obstruction or compression of the heart; or shock resulting from the failure of the heart to maintain adequate output.31 Validation studies have shown specificity of 99.3%, sensitivity of 59.8%, positive predictive value of 78.8%, and negative predictive value of 98.1% for ICD-9-CM code 785.51 to identify CS.31 Admissions with CS due to non-AMI cause, younger than 75 years, interhospital transfers, and those without documented sex or in-hospital mortality were excluded.

Using previously validated methods, demographic details, hospital characteristics, use of coronary angiography, PCI, mechanical circulatory support (MCS), invasive hemodynamic monitoring (pulmonary artery catheterization or right heart catheterization), acute noncardiac organ failure, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis associated with each discharge were identified from the HCUP-NIS database (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org).2,7–9,21–24,29 The modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index by Deyo et al32 was used to identify the burden of comorbid diseases. Percutaneous MCS in this study refers to either the use of an Impella (AbioMed, Danvers, MA) or a TandemHeart (Cardiac Assist Inc, Pittsburgh, PA) device.21,22,26,27

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included temporal trends in the prevalence of CS in all AMI admissions; in-hospital mortality; use of MCS, PCI, and invasive hemodynamic monitoring; hospitalization costs; length of hospital stay; and discharge disposition in older AMI-CS admissions.

Statistical Analyses

As recommended by HCUP-NIS, survey procedures using weighted discharges provided with the HCUP-NIS database were used to generate national estimates. Using the weighted trends provided by HCUP-NIS, samples from 2000 to 2011 were re-weighted to adjust for the 2012 HCUP-NIS redesign.33 The new sampling strategy is expected to result in more precise estimates than the previous HCUP-NIS design by reducing sampling error.20 Chi-square and t tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The inherent restrictions of the HCUP-NIS database related to research design, data interpretation, and data analysis were reviewed and addressed.34 Pertinent considerations included not assessing individual hospital-level volumes (due to the changes to sampling design detailed), treating each entry as an “admission” as opposed to individual patients, restricting study details to inpatient factors because HCUP-NIS does not include outpatient data, and limiting administrative codes to those previously validated and used for similar studies.

Logistic regression was used to examine the odds of CS prevalence by year of presentation in admissions with AMI using 2000 as the referent. Models were adjusted for race/ethnicity, comorbid conditions, primary payer, socioeconomic status, and hospital characteristics. Logistic regression was used to examine the odds of in-hospital mortality by year of presentation in admissions with AMI-CS using 2000 as the referent. Models were adjusted for race/ethnicity, admission year, primary payer status, socioeconomic stratum, hospital characteristics, comorbid conditions, AMI type, acute organ failure, cardiac arrest, and cardiac and noncardiac procedures. Results were presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. For multivariate modeling, purposeful selection of statistically (P<.20) and a priori selected clinically relevant variables was conducted. A priori subgroup analyses were performed for race, presence of cardiac arrest, type of AMI, and use of PCI and MCS. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 25.0 (IBM Corp).

RESULTS

From January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2014, a total of 9,747,034 admissions with a primary diagnosis of AMI were identified, of which 444,253 (4.6%) developed CS. After excluding admissions younger than 75 years, interhospital transfers, and those without available sex data, a final study population of 134,501 (30.3%) admissions was included. Women comprised 69,220 (51.5%) of the included admissions, and baseline characteristics of the 2 cohorts are presented in Table 1. Compared with men, women were more likely to be older, be of Hispanic or nonwhite race, and have lower comorbidity. Older women had a lower frequency of noncardiac organ failure and concomitant cardiac arrest (Table 1). Coronary angiography, PCI, surgical revascularization, MCS and mechanical ventilation, and acute hemodialysis were used less frequently in older adult women compared with men (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults With AMI-CS Stratified by Sexa

| Characteristic | Older Men (n=65,281) | Older Women (n=69,220) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 82.0±5.0 | 83.4±5.5 | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 82.4% | 81.8% | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 4.3% | 6.3% | |

| Othersb | 13.2% | 11.9% | |

| Weekend admission | 27.0% | 26.8% | .21 |

| Primary payer | |||

| Medicare | 90.1% | 91.9% | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 1.2% | 1.4% | |

| Othersc | 8.6% | 6.7% | |

| Quartile of median household income for zip code | |||

| 0–25th | 20.4% | 20.4% | .04 |

| 26th–50th | 25.4% | 26.1% | |

| 51st–75th | 25.7% | 25.5% | |

| 75th–100th | 28.4% | 28.0% | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | |||

| 0–3 | — | — | <.001 |

| 4–6 | 58.2% | 65.3% | |

| ≥7 | 41.8% | 34.7% | |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Heart failure | 62.2% | 59.9% | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20.7% | 13.7% | <.001 |

| Cancer | 11.6% | 8.2% | <.001 |

| Hospital teaching status and location | |||

| Rural | 9.0% | 11.3% | <.001 |

| Urban nonteaching | 46.1% | 45.7% | |

| Urban teaching | 44.9% | 43.0% | |

| Hospital bed-size | |||

| Small | 8.7% | 9.9% | <.001 |

| Medium | 23.5% | 24.0% | |

| Large | 67.8% | 66.1% | |

| Hospital region | |||

| Northeast | 19.1% | 21.0% | <.001 |

| Midwest | 22.1% | 24.0% | |

| South | 36.3% | 35.2% | |

| West | 22.4% | 19.8% | |

| Acute organ failure | |||

| Respiratory | 44.1% | 39.1% | <.001 |

| Renal | 44.9% | 35.5% | <.001 |

| Hepatic | 7.1% | 5.8% | <.001 |

| Hematologic | 10.8% | 8.4% | <.001 |

| Neurologic | 12.5% | 9.1% | <.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 22.3% | 18.5% | <.001 |

| Coronary angiography | 55.4% | 49.2% | <.001 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 36.3% | 34.4% | <.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 12.0% | 8.1% | <.001 |

| Invasive hemodynamic assessmentd | 16.8% | 14.7% | <.001 |

| MCS | |||

| Total | 34.3% | 27.2% | <.001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 33.6% | 26.8% | <.001 |

| Percutaneous MCSe | 0.7% | 0.5% | <.001 |

| ECMO | 0.1% | 0.0% | <.001 |

| Noncardiac procedures | |||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 42.2% | 36.6% | <.001 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 4.1% | 4.0% | .09 |

| Hemodialysis | 3.6% | 2.3% | <.001 |

AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CS = cardiogenic shock; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MCS = mechanical circulatory support.

Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and others.

Private, self-pay, no charge, and others.

Right heart catheterization or pulmonary artery catheterization.

Impella or TandemHeart.

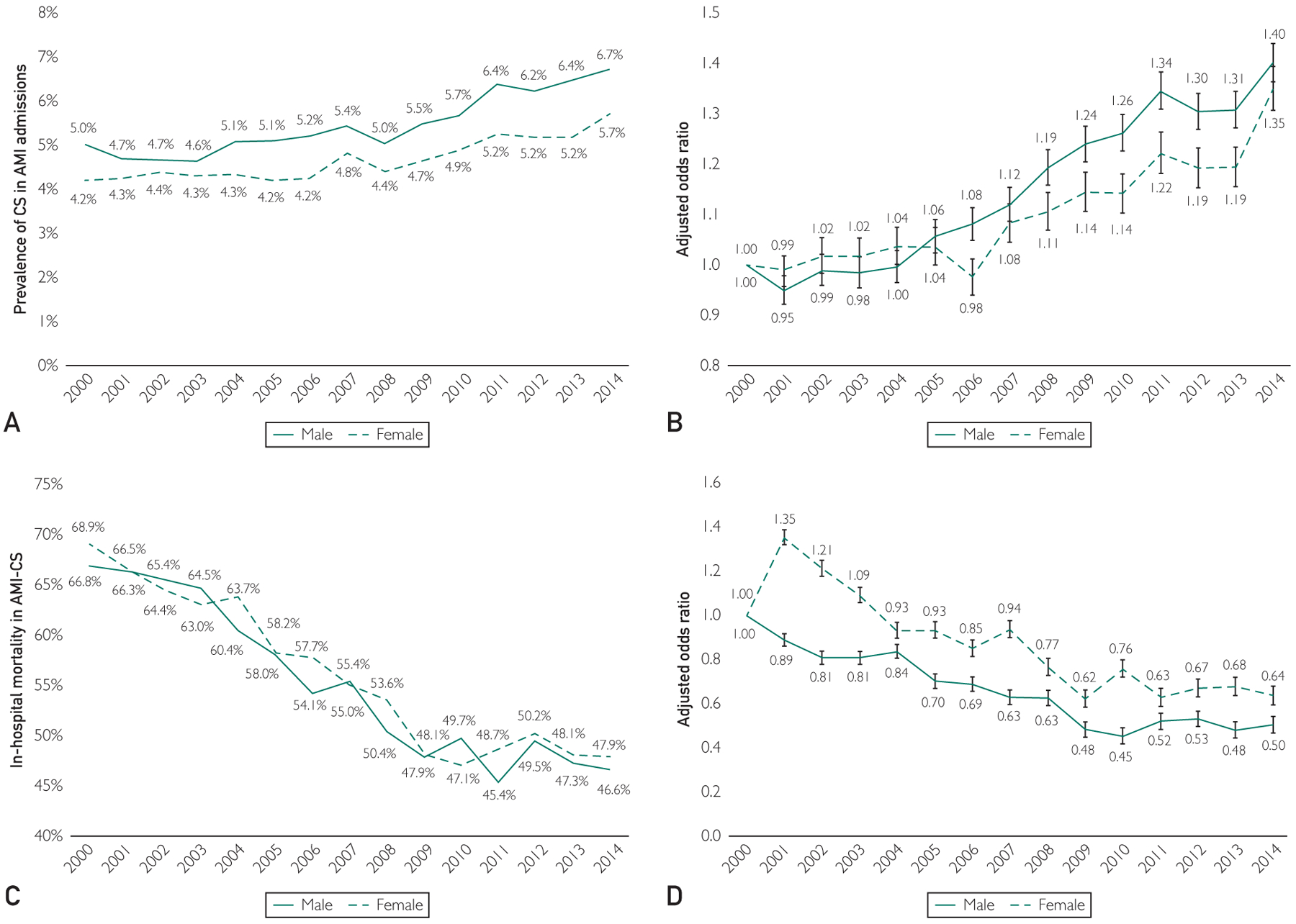

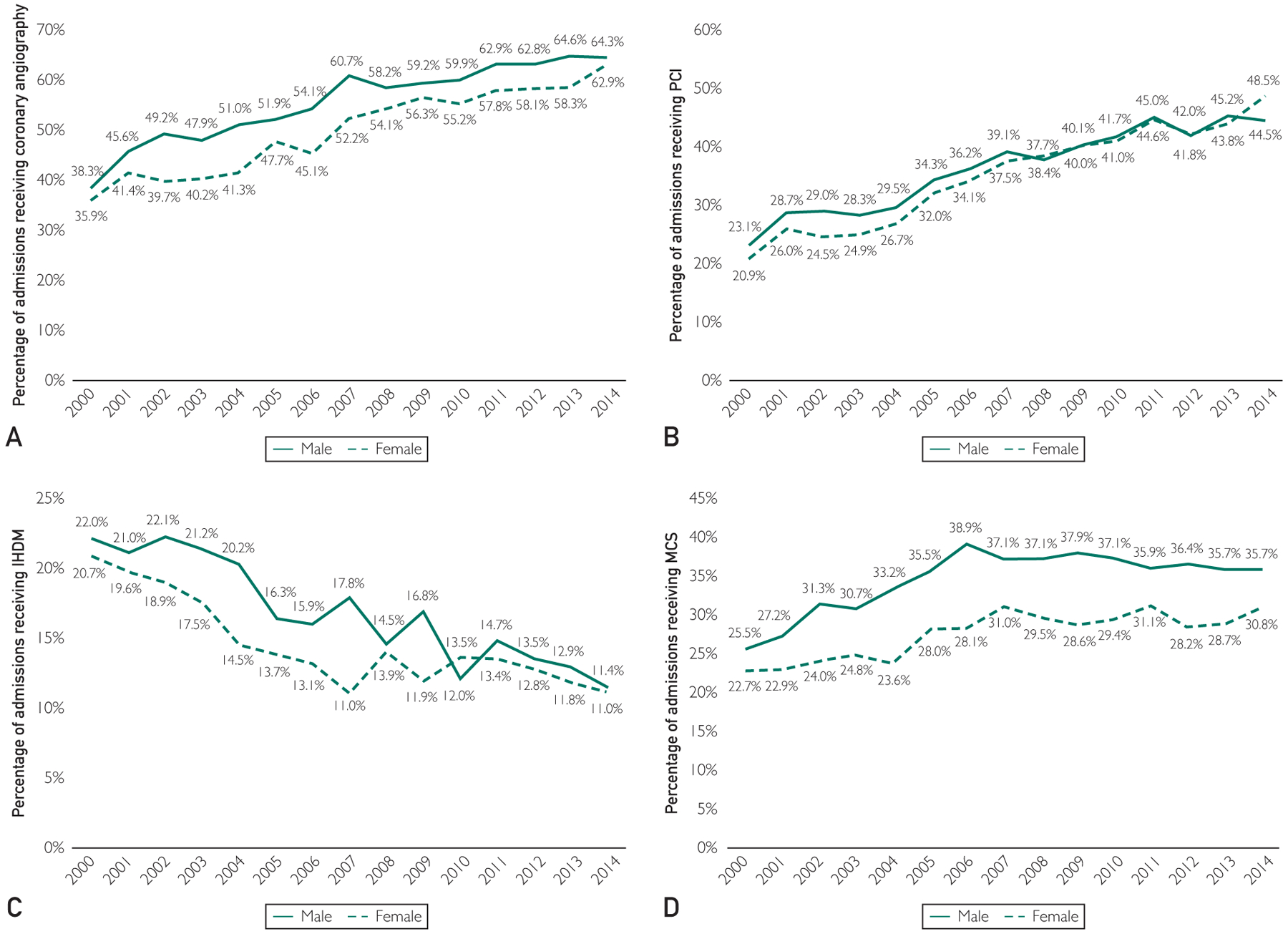

The 15-year unadjusted and adjusted temporal trends of the proportion of AMI admissions complicated by CS are presented in Figure 1A and 1B. There was a steady increase in the proportion of AMI admissions with CS during the 15-year study period. Older women were more likely to be admitted to rural and small hospitals as compared with older men. The 15-year temporal trends of hospital-level variation in older men and women are presented in the Supplemental Figure (available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). The distribution of admissions by hospital type, size, and location over time were similar in men and women. ST-segment-elevation AMI-CS was the predominant cause, with higher frequency in women compared with men (66% [45,685 of 69,220] vs 60.5% [39,495 of 65,281]; P<.001). Compared with older men, women were less likely to have coronary angiography, PCI, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, and MCS performed over the 15-year study period (Table 1; Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Trends in the prevalence and in-hospital mortality in older acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock (AMI-CS) admissions stratified by sex. A, Unadjusted temporal trends of the proportion of AMI admissions with CS stratified by sex (P<.001 for trend over time). B, Adjusted odds ratio for admission with AMI-CS by year with 2000 as the referent; adjusted for race/ethnicity, comorbid conditions, primary payer, socioeconomic status, and hospital characteristics (P<.001 for trend over time). C, Unadjusted in-hospital mortality in AMI-CS by year of admission, stratified by sex (P<.001 for trend over time). D, Adjusted multivariate logistic regression for in-hospital mortality temporal trends with 2000 as referent year; adjusted for race/ethnicity, admission year, primary payer status, socioeconomic stratum, hospital characteristics, comorbid conditions, AMI type, acute organ failure, cardiac arrest, and cardiac and noncardiac procedures (P<.001 for trend over time).

FIGURE 2.

Fifteen-year trends in the use of (A) coronary angiography, (B) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), (C) invasive hemodynamic monitoring (IHDM), and (D) mechanical circulatory support (MCS) in older acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock (AMI-CS) admissions stratified by sex. All P<.001 for trend over time.

Compared with older men, older women had higher unadjusted in-hospital mortality (56.6% [39,179 of 69,220] vs 55.1% [35,970 of 65,281]; unadjusted OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04–1.09; P<.001). The 15-year unadjusted and adjusted temporal trends of in-hospital mortality in AMI-CS stratified by sex are presented in Figure 1C and D. Despite significant decreases in in-hospital mortality over time in both men and women, after adjustment for potential confounders, women had significantly higher in-hospital mortality than men throughout the study period. In a multivariable logistic regression for in-hospital mortality in older AMI-CS admissions, female sex was an independent predictor of higher in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02–1.08; P<.001; Supplemental Table 3, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). Older women had shorter hospital lengths of stay, had lower hospitalization costs, and were discharged less frequently to home and more frequently to a skilled nursing facility (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical Outcomes of Older Adults With AMI-CS Stratified by Sexa

| Characteristic | Older Men (n=65,281) | Older Women (n=69,220) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 55.1% | 56.6% | <.001 |

| Median length of stay (d), mean ± SD | 8.9±9.8 | 8.1±8.9 | <.001 |

| Median hospitalization costs (US $), mean ± SD | 103,944±132,184 | 82,966±110,499 | <.001 |

| Discharge disposition | |||

| Home | 28.4% | 22.4% | <.001 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 51.4% | 57.9% | |

| Home with home health care | 20.0% | 19.6% | |

| Against medical advice | 0.2% | 0.1% |

AMI = acute myocardial infarction; CS = cardiogenic shock.

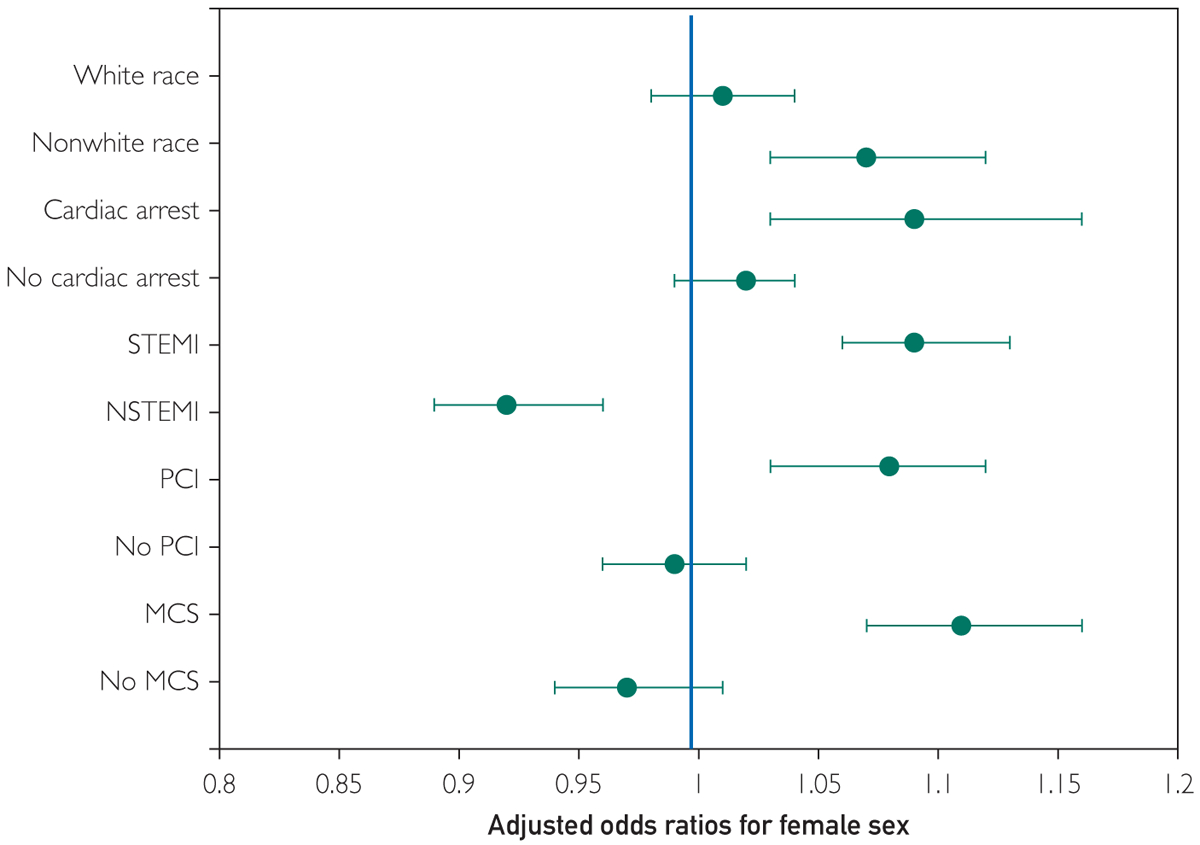

The adjusted in-hospital mortality for older women compared with older adult men in prespecified subgroups stratified by race/ethnicity, presence of cardiac arrest, type of AMI, and use of PCI and MCS is presented in Figure 3. Female sex was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in admissions among Hispanics and nonwhite race (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03–1.12; P<.001), those with cardiac arrest (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.03–1.16; P<.001) and STEMI-CS (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.06–1.13; P<.001), and in cohorts receiving PCI (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03–1.12; P<.001) and MCS (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.07–1.16; P<.001).

FIGURE 3.

Multivariate predictors of in-hospital mortality in older women with acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock (AMI-CS) compared with older men. Multivariable adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs)* for in-hospital mortality in women stratified by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white/all other races/ethnicities), timing of cardiac arrest, type of AMI, performance of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and mechanical circulatory support (MCS) use; all P<.001. *Adjusted for race/ethnicity, year of admission, primary payer, socioeconomic status, hospital location/teaching status, hospital bed size, hospital region, comorbid conditions, type of AMI, acute organ failure, cardiac arrest, coronary angiography, PCI, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, MCS, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis. NSTEMI = non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

DISCUSSION

In this 15-year national study of older AMI-CS admissions, we observed that women were more likely to be older, be Hispanic or nonwhite race, have lower comorbidity, and have lower frequency of noncardiac organ failure and cardiac arrest compared with men. Despite this and the fact that female sex was an independent predictor of in-hospital hospital mortality and posthospitalization resource utilization in older AMI-CS admissions, older women consistently underwent less frequent coronary angiography, PCI, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, and use of MCS during this 15-year period. Despite a steady decrease in the in-hospital mortality during the study period, adjusted trends showed consistently higher in-hospital mortality in women compared with men.

Though the overall mortality from AMI-CS has decreased during the last few decades, there remain significant challenges and opportunities for improvement in this population.2 As noted previously, patient and hospital-specific demographic factors continue to be associated with differences in clinical outcomes in this population.7,9,29 Our data are consistent with prior studies that demonstrate high mortality and morbidity in older patients with AMI-CS.3,12,18,35–37 Though older patients are known to benefit from early angiography in AMI with or without CS, the uptake of angiography and PCI in this population is significantly lower due to concerns for higher rates of bleeding and other complications.38,39

Additionally, patient preference and perceived benefit by the patient, family, and practitioners, as well as unmeasured factors such as frailty and other comorbid conditions, may contribute to the decreased use of invasive interventions. Using the HCUP-NIS database from 1999 to 2013, Damluji et al3 showed that use of PCI was associated with higher survival to hospital discharge and more discharges to home in older admissions with AMI-CS. These results were also confirmed in the SHOCK Registry data despite the stated lack of benefit from revascularization (PCI or surgical) noted in the SHOCK trial.40

Though not the focus in this study, our study is consistent with improved survival associated with PCI in this population of older AMI-CS admissions (adjusted OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62–0.67; P<.001). In addition to PCI, older patients frequently receive delayed revascularization and lower rates of guideline-directed medical therapy during and after the acute care hospitalization.41

However, because this study was focused on older patients, we did not compare this cohort with the population younger than 75 years. It is conceivable that older patients have more frequent treatment-limiting decisions and higher rates of adverse effects and lower cognitive support that might further contribute to these disparities and lead to worse clinical outcomes. These patients frequently need careful decision making with the involvement of multidisciplinary care teams, including specialists from palliative care, to develop individualized care plans involving the use of cardiac, respiratory, and renal support therapies.2,9,21,22,24,42–45

In addition to these challenges associated with advanced age, our study provides further information on the concomitant sex- and gender-based differences in these older patients. Prior work in the field of AMI have noted women to have lower use of revascularization, lower use of guideline-directed medical therapy, and worse in-hospital outcomes.46–50 In comparison to AMI, there are limited data on the AMI-CS population. In a population database from Ontario, Abdel-Qadir et al13 noted that women with AMI-CS frequently presented to non-PCI-capable centers and were less likely to be transferred to PCI-capable centers. In all-comers with AMI-CS, the French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation or Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction registry did not show differences in clinical outcomes stratified by sex.51 However, the use of PCI was associated with a survival benefit in women as compared with men.

Given the retrospective nature of this registry, further dedicated trials are needed to understand this phenomenon in a prospective manner. Using the Catheter-Based Ventricular Assist Device registry, Joseph et al52 showed women with AMI-CS to benefit from early initiation of percutaneous MCS. Consistent with these data, we note that older women were more likely to be admitted to rural and smaller hospitals, which have worse associated in-hospital outcomes in AMI-CS.7 Furthermore, our study confirms lower use of coronary angiography and PCI in older women as compared with men, both of which have been noted to be independently associated with higher in-hospital survival in this study. Though the temporal trends show a significant increase in the use of these therapies, there remain persistent sex-based disparities.

Furthermore, our study provides incremental insights into the use of percutaneous MCS and invasive hemodynamic monitoring devices.21,22,26,27,42–45,53 Despite the lack of survival benefit with these technologies, there is higher adoption of these devices in men compared with women.54 This may partly be explained by the higher severity of illness and greater rates of organ failure noted in older men compared with women.55 Alternately, it is possible that men experienced greater hemodynamic instability during and after the index PCI, resulting in a greater need for these hemodynamic adjuncts.52 Given the higher average age at admission in women, it is possible that they had greater treatment-limiting decisions resulting in the reduced use of organ support therapies.9

Last, women had higher use of posthospitalization nursing facilities, suggestive of continued higher use of health care resources after the index hospitalization.56 Furthermore, this posthospitalization use of health care facilities is potentially associated with loss of independence and affects quality of life after admission.57 This may suggest that more aggressive early therapy in women may result in lower need for subsequent care. Though we have achieved significant success in decreasing the in-hospital mortality in AMI-CS, it is crucial that we continue to seek incremental gains by addressing easily identifiable risk factors (such as sex) and use the information in guiding treatment strategies.

In an exploratory subgroup analysis, we identified multiple subgroups in which female sex was associated with worse in-hospital mortality. Consistent with similar literature from other AMI studies, Hispanic and nonwhite women had higher in-hospital mortality.47 It appears that age, sex, and race/ethnicity are all independent correlates of worse in-hospital mortality and are worthy of further evaluation in dedicated studies in AMI-CS populations. Women not receiving PCI or MCS support had similar outcomes compared with older men, which might allude to predetermined life-limiting decisions. Last, women with higher acuity of illness as noted by the use of MCS and concomitant cardiac arrest had worse outcomes compared with men. These individual subgroups are hypothesis generating and will likely aid in identification of vulnerable populations to better evaluate disparities in health care delivery.

This study has several limitations despite the HCUP-NIS database’s attempts to mitigate potential errors by using internal and external quality control measures. The ICD-9-CM codes for AMI and CS have been previously validated, which reduces the inherent errors in the study.30,31 The HCUP-NIS registry does not distinguish sex from gender and gender identity, which remains an important limitation of this analysis.58 Important factors such as the delay in presentation from time of onset of AMI symptoms, timing of CS, reasons for not receiving aggressive medical care, timing of multiorgan failure, and treatment-limiting decisions of organ support could not be reliably identified in this database. It is possible that despite best attempts at controlling for confounders by a multivariate analysis, female sex was a marker of greater illness severity due to residual confounding. Echocardiographic data, angiographic variables, and hemodynamic parameters were unavailable in this database, which limits physiologic assessments of disease severity. Despite these limitations, this study addresses an important knowledge gap highlighting the differences in outcomes in older women compared with men in a 15-year AMI-CS population.

CONCLUSION

In older adults (aged ≥75 years) with AMI-CS, this study noted female sex to be a predictor of worse in-hospital outcomes. There remain significant sex and gender disparities in the management and outcomes. Older women had lower acuity of illness, lower use of angiography and PCI, and higher in-hospital mortality. Further quantitative and qualitative research is needed in these vulnerable populations to aid in the delivery of equitable service in acute cardiovascular care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Dr Saraschandra Vallabhajosyula is supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- CS

cardiogenic shock

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- IHDM

invasive hemodynamic monitoring

- MCS

mechanical circulatory support

- NIS

National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample

- NSTEMI

non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- OR

odds ratio

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- SHOCK

Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock

- STEMI

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL ONLINE MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Potential Competing Interests: Dr Jaffe has been a consultant for Beckman, Abbott, Siemens, ET Healthcare, Sphing6-toec, Quidel, Brava, and Novartis. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kochar A, Al-Khalidi HR, Hansen SM, et al. Delays in primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients presenting with cardiogenic shock. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(18):1824–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallabhajosyula S, Dunlay SM, Prasad A, et al. Acute noncardiac organ failure in acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(14):1781–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damluji AA, Bandeen-Roche K, Berkower C, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in older patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(15):1890–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallabhajosyula S, Dunlay SM, Barsness GW, et al. Temporal trends, predictors, and outcomes of acute kidney injury and hemodialysis use in acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallabhajosyula S, Kashani K, Dunlay SM, et al. Acute respiratory failure and mechanical ventilation in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction in the USA, 2000–2014. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vallabhajosyula S, Prasad A, Gulati R, Barsness GW. Contemporary prevalence, trends, and outcomes of coronary chronic total occlusions in acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;24:100414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallabhajosyula S, Dunlay SM, Barsness GW, Rihal CS, Holmes DR Jr, Prasad A. Hospital-level disparities in the outcomes of acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(4):491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallabhajosyula S, Dunlay SM, Murphree DH Jr, et al. Cardiogenic shock in takotsubo cardiomyopathy versus acute myocardial infarction: an 8-year national perspective on clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(6):469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallabhajosyula S, Prasad A, Dunlay SM, et al. Utilization of palliative care for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a 15-year national perspective on trends, disparities, predictors, and outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(15): e011954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon V, Webb JG, Hillis LD, et al. Outcome and profile of ventricular septal rupture with cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3 suppl A):1110–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(9):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(19): 2570–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Qadir HM, Ivanov J, Austin PC, Tu JV, Dzavik V. Sex differences in the management and outcomes of Ontario patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(6):691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donataccio MP, Puymirat E, Parapid B, et al. In-hospital outcomes and long-term mortality according to sex and management strategy in acute myocardial infarction. Insights from the French ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) 2005 Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du X, Spatz ES, Dreyer RP, et al. China PEACE Collaborative Group. Sex differences in clinical profiles and quality of care among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction from 2001 to 2011: insights from the China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE)-retrospective study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nehme Z, Andrew E, Bernard S, Smith K. Sex differences in the quality-of-life and functional outcome of cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation. 2019;137:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liakos M, Parikh PB. Gender disparities in presentation, management, and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(8):64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Rihal CS, Berger PB, Holmes DR Jr. Outcomes of elderly patients with cardiogenic shock treated with early percutaneous revascularization. Am Heart J. 2004;147(6): 1066–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al. American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.HCUP. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2009. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_2009_INTRODUCTION.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2015.

- 21.Vallabhajosyula S, Arora S, Lahewala S, et al. Temporary mechanical circulatory support for refractory cardiogenic shock before left ventricular assist device surgery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(22):e010193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vallabhajosyula S, Arora S, Sakhuja A, et al. Trends, predictors, and outcomes of temporary mechanical circulatory support for postcardiac surgery cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2019; 123(3):489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallabhajosyula S, Deshmukh AJ, Kashani K, Prasad A, Sakhuja A. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy in severe sepsis: nationwide trends, predictors, and outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7(18):e009160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vallabhajosyula S, Dunlay SM, Kashani K, et al. Temporal trends and outcomes of prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy use in acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock in the United States. Int J Cardiol. 2019;285:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vallabhajosyula S, El Hajj SC, Bell MR, et al. Intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography, and fractional flow reserve use in acute myocardial infarction [published online ahead of print November 14, 2019]. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 10.1002/ccd.28543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallabhajosyula S, Prasad A, Bell MR, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use in acute myocardial infarction in the United States, 2000 to 2014. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(12): e005929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallabhajosyula S, Prasad A, Sandhu GS, et al. Mechanical circulatory support-assisted early percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock: 10-year national temporal trends, predictors and outcomes [published online ahead of print November 20, 2019]. EuroIntervention, 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallabhajosyula S, Vallabhajosyula S, Bell MR, et al. Early vs. delayed in-hospital cardiac arrest complicating ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Resuscitation. 2020;148:242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallabhajosyula S, Ya’Qoub L, Dunlay SM, et al. Sex disparities in acute kidney injury complicating acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6(4):874–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coloma PM, Valkhoff VE, Mazzaglia G, et al. EU-ADR Consortium. Identification of acute myocardial infarction from electronic healthcare records using different disease coding systems: a validation study in three European countries. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert L, Blais C, Hamel D, et al. Evaluation of care and surveillance of cardiovascular disease: can we trust medico-administrative hospital data? Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(2):162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khera R, Krumholz HM. With great power comes great responsibility: big data research from the National Inpatient Sample. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khera R, Angraal S, Couch T, et al. Adherence to methodological standards in research using the National Inpatient Sample. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2011–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CP, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(19): 2549–2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pilgrim T, Heg D, Tal K, et al. Age- and gender-related disparities in primary percutaneous coronary interventions for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2015; 10(9):e0137047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeymer U, Vogt A, Zahn R, et al. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte (ALKK). Predictors of in-hospital mortality in 1333 patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); results of the primary PCI registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK). Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(4):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boersma E, Harrington RA, Moliterno DJ, et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of all major randomised clinical trials [Erratum in Lancet. 2002;359(9323):2120]. Lancet. 2002;359(9302):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damman P, Clayton T, Wallentin L, et al. Effects of age on long-term outcomes after a routine invasive or selective invasive strategy in patients presenting with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a collaborative analysis of individual data from the FRISC II - ICTUS - RITA-3 (FIR) trials. Heart. 2012;98(3):207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dzavik V, Sleeper LA, Cocke TP, et al. ; SHOCK Investigators. Early revascularization is associated with improved survival in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(9):828–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medina HM, Cannon CP, Zhao X, et al. Quality of acute myocardial infarction care and outcomes in 33,997 patients aged 80 years or older: findings from Get With The Guidelines-Coronary Artery Disease (GWTG-CAD). Am Heart J. 2011;162(2):283–290.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallabhajosyula S, Barsness GW, Vallabhajosyula S. Multidisciplinary teams for cardiogenic shock. Aging (Albany NY). 2019; 11(14):4774–4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vallabhajosyula S, O’Horo JC, Antharam P, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with concomitant impella versus venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock [published online ahead of print July 19, 2019]. ASAIO J, 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vallabhajosyula S, O’Horo JC, Antharam P, et al. Concomitant intra-aortic balloon pump use in cardiogenic shock requiring veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(9):e006930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallabhajosyula S, Patlolla SH, Sandhyavenu H, et al. Periprocedural cardiopulmonary bypass or venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation during transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7: e009608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hess CN, McCoy LA, Duggirala HJ, et al. Sex-based differences in outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: a report from TRANSLATE-ACS. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1):e000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hinohara TT, Al-Khalidi HR, Fordyce CB, et al. Impact of regional systems of care on disparities in care among female and black patients presenting with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radovanovic D, Nallamothu BK, Seifert B, et al. ; AMIS Plus Investigators. Temporal trends in treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction among men and women in Switzerland between 1997 and 2011. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1(3):183–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero T, Greenwood KL, Glaser D. Sex differences in acute myocardial infarction hospital management and outcomes: update from facilities with comparable standards of quality care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33(6):568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu J, Mehran R, Grinfeld L, et al. Sex-based differences in bleeding and long term adverse events after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: three year results from the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85(3):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isorni MA, Aissaoui N, Angoulvant D, et al. FAST-MI investigators. Temporal trends in clinical characteristics and management according to sex in patients with cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction: the FAST-MI programme. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111(10):555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joseph SM, Brisco MA, Colvin M, Grady KL, Walsh MN, Cook JL; genVAD Working Group. Women with cardiogenic shock derive greater benefit from early mechanical circulatory support: an update from the cVAD registry. J Interv Cardiol. 2016;29(3):248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Subramaniam AV, Barsness GW, Vallabhajosyula S, Vallabhajosyula S. Complications of temporary percutaneous mechanical circulatory support for cardiogenic shock: an appraisal of contemporary literature. Cardiol Ther. 2019;8(2): 211–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, et al. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Mission: Lifeline. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(16):e232–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen MG, Kelly RV, Kong DF, et al. Pulmonary artery catheterization in acute coronary syndromes: insights from the GUSTO IIb and GUSTO III trials. Am J Med. 2005;118(5): 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sleeper LA, Ramanathan K, Picard MH, et al. ; SHOCK Investigators. Functional status and quality of life after emergency revascularization for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(2):266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenbaum AN, Naksuk N, Gharacholou SM, Brenes-Salazar JA. Outcomes of nonagenarians admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit by the elders risk assessment score for long-term mortality risk stratification. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(8): 1421–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson JL, Greaves L, Repta R. Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.