Abstract

Background

Folates, including folic acid, may play a dual role in colorectal cancer development. Folate is suggested to be protective in early carcinogenesis but could accelerate growth of premalignant lesions or micrometastases. Whether circulating concentrations of folate and folic acid, measured around time of diagnosis, are associated with recurrence and survival in colorectal cancer patients is largely unknown.

Methods

Circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, and folate catabolites p-aminobenzoylglutamate and p-acetamidobenzoylglutamate were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry at diagnosis in 2024 stage I-III colorectal cancer patients from European and US patient cohort studies. Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess associations between folate, folic acid, and folate catabolites concentrations with recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival.

Results

No statistically significant associations were observed between folate, p-aminobenzoylglutamate, and p-acetamidobenzoylglutamate concentrations and recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival, with hazard ratios ranging from 0.92 to 1.16. The detection of folic acid in the circulation (yes or no) was not associated with any outcome. However, among patients with detectable folic acid concentrations (n = 296), a higher risk of recurrence was observed for each twofold increase in folic acid (hazard ratio = 1.31, 95% confidence interval = 1.02 to 1.58). No statistically significant associations were found between folic acid concentrations and overall and disease-free survival.

Conclusions

Circulating folate and folate catabolite concentrations at colorectal cancer diagnosis were not associated with recurrence and survival. However, caution is warranted for high blood concentrations of folic acid because they may increase the risk of colorectal cancer recurrence.

Folates have been hypothesized to play a dual role in relation to colorectal cancer risk (1‐3). Epidemiologic evidence suggests that sufficient folate may protect against colorectal cancer development (1,4), which is supported by in vitro and animal studies (2,5‐7). However, high circulating concentrations of folate, including folic acid, may facilitate the growth of premalignant lesions or micrometastases once they have been established (2,8‐11).

Circulating concentrations of folates originate from dietary folate naturally occurring in, for example, green leafy vegetables, legumes, or liver products (12); are formed by microbiota present in the gut (13); or originate from the ingestion of the synthetic form of folate (ie, folic acid) present in dietary supplements and fortified foods (6,14). Dietary supplements are regularly consumed by cancer patients (15), and fortification is mandatory in countries such as the United States (16). Folic acid is converted to the active form of folate by the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (6). Whenever folic acid cannot be converted to folate by DHFR - this conversion is the rate-limiting step in folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism (FOCM) (17) as a result of low DHFR activity or excessive intake of folic acid - unmetabolized folic acid may be detected in the circulation (6).

Some folate is degraded, mainly in the liver, to the catabolite p-aminobenzoylglutamate (pABG) (18), and approximately 80% is converted to p-acetamidobenzoylglutamate (apABG) in the kidneys (19,20). Both catabolites are thought to reflect folate turnover (21,22) and provide useful insights into the role of folate in health (20). Folate is crucial in FOCM for nucleotide synthesis as well as DNA repair and, indirectly, for the formation of the methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine involved in DNA methylation (23‐25). Low concentrations of folate may result in aberrant DNA methylation patterns and impaired DNA stability and synthesis, which are defects that may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis (26,27).

Although the role of folate in colorectal cancer etiology has been studied extensively, research investigating the association between different folates and colorectal cancer prognosis is scarce. Folic acid not only has different bioavailability but also may possess different biochemical effects compared with natural folates. Folic acid and natural folates differ with respect to affinity for the folate receptors and, therefore, transport and utilization in FOCM (28). We hypothesize that specifically unmetabolized folic acid may foster growth of remaining cancerous cells after treatment, and therefore higher concentrations of folic acid could lead to more recurrences.

Initial studies among colorectal cancer survivors observed no statistically significant associations between serum folate concentrations and recurrence or survival (29‐31). A study among 78 stage II-IV colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy showed nonstatistically significantly fewer colorectal cancer recurrences and deaths with high compared with low serum folate concentrations at diagnosis (29). Serum folate concentrations at colorectal cancer diagnosis in 93 patients with stage IV disease yielded no association with overall survival (30). These studies were, however, limited by a modest sample size (29‐31) and the relatively small number of events (29,30). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted investigating the association between the different forms of circulating folate and folate catabolites and colorectal cancer recurrence or survival.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the association of circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, and folate catabolites at diagnosis, with recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival in 2024 stage I-III colorectal cancer patients originating from 6 European and US patient cohorts.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

A total of 2024 stage I-III colorectal cancer patients from 6 patient cohorts were included in the current study as part of the international, prospective FOCUS consortium. The FOCUS consortium comprises patients from the COLON study (n = 1094, Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03191110) (32), the EnCoRe study (n = 297, Maastricht University, the Netherlands) (33) (Netherlands Trial Register: 7099), the CORSA study (n = 209, Medical University of Vienna, Austria), and 3 sites of the ColoCare study (n = 260, University of Heidelberg and the German Cancer Research Center and National Center for Tumor Diseases, Germany; n = 46, Huntsman Cancer Institute, United States; and n = 118, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, United States) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02328677) (34). Clinical, demographic, and lifestyle-related characteristics were collected for all participants and harmonized across all cohorts within the FOCUS consortium. All studies were approved by local medical ethics committees, and the current study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants had histologically confirmed stage I-III colorectal cancer and provided written informed consent. Brief details on cohorts and data collection can be found in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Biochemical Analysis

Plasma or serum samples were collected at colorectal cancer diagnosis and shipped on dry ice for analysis at the laboratory of BEVITAL AS (Bergen, Norway; www.bevital.no). Plasma samples were used for COLON (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA]), EnCoRe (EDTA), and CORSA (EDTA and heparin), and serum samples were used for the ColoCare sites. Folate concentrations were measured as the sum of the folate species 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (5-mTHF) and 4-alpha-hydroxy-5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (hmTHF) (35). In addition, we assessed the concentration of unmetabolized folic acid and folate catabolites pABG and apABG (36). Concentrations of 5-mTHF, hmTHF, folic acid, pABG, and apABG were quantified by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (36). Details on sample preparation are provided in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Study Endpoints

Study endpoints included recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival. Recurrence was defined as locoregional or distant recurrence after complete tumor resection. Overall survival events were investigated by using death from any cause in the analysis. Disease-free survival was investigated by using a recurrence or death from any cause as events in the analysis. For all outcomes, follow-up time was calculated starting from the date of blood collection. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were used to investigate the associations of circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, and folate catabolites with recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival. The proportional hazard assumption for Cox proportional hazard models was assessed by using Schoenfeld residuals with no evidence of nonproportionality being detected. Folate concentrations were analyzed continuously (log2 transformed) as well as in tertiles in which the lowest tertile was used as the reference. Tertiles were defined based on the total study population. Ptrend values were computed for folate concentration tertiles using the medians of the corresponding tertiles. Folic acid, pABG, and apABG were investigated in 2 ways. First, concentrations were categorized into a dichotomous variable to compare patients with a detectable concentration with patients with concentration equal to or below the level of detection. Second, for patients with detectable concentrations, we also performed analyses similar to those for folate. The associations of tertiles of circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, pABG, and apABG with recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival were also investigated using cohort-specific tertiles. The tertile values of the cohort-specific tertiles were used continuously to compute the P value for linear trend.

Crude hazard ratios (HRs) and hazard ratios adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, cohort, and chemotherapy status (receiving no chemotherapy, only neoadjuvant chemotherapy, only adjuvant chemotherapy, or both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy) were calculated for folates. Log2-transformed creatinine concentrations were additionally added as a covariate for pABG and apABG analyses because these have high renal clearance, and it is thus important to take kidney function into account (37). Adjustment for other known potential confounding factors, that is, disease stage, body mass index (38), alcohol intake (39), smoking (40), analytical plate, and batch, did not markedly influence the estimates (<10%) and were therefore not included in the final model.

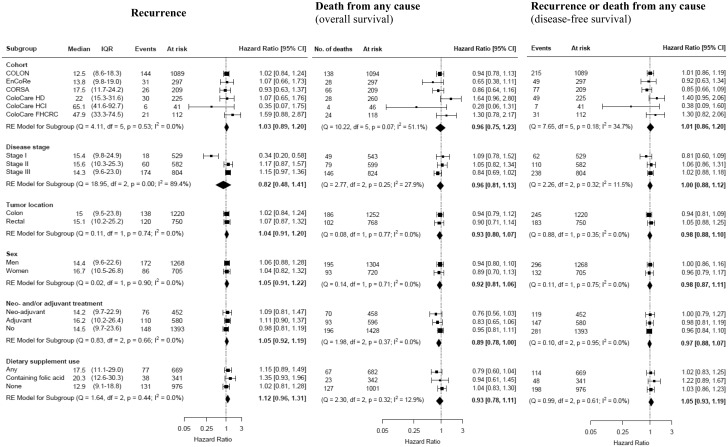

Subgroup analyses were conducted and presented by forest plots to assess potential effect measure modification by cohort, disease stage, tumor location, sex, neo- and/or adjuvant treatment, and dietary supplement use.

Cox proportional hazard models were computed in SAS version 9.4 software (Cary, NC) using 2-sided tests. Forest plots, including heterogeneity tests using the package metafor (41), were prepared in R, version 3.3.6. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses and further details concerning statistical methods are described in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Results

Study Population

Baseline characteristics of the total study population (n = 2024) and by cohort are displayed in Table 1. The majority of the participants were men (64%), overweight (43%), and former or never smokers (53% and 34%). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 66 (60-73) years, and 27%, 30%, and 41% of the participants presented with stage I, II, and III, respectively. Colon cancer was diagnosed among 62% of participants and 38% had rectal cancer. Dietary supplement use was reported by 41% of the total study population, and 20% of the participants reported to use dietary supplements containing folic acid.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total study population and stratified by cohort

| Cohorts |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total population (n = 2024) | COLON (n = 1094) | EnCoRe (n = 297) | CORSA (n = 209) | ColoCare HD (n = 260) | ColoCare HCI (n = 46) | ColoCare FHCRC (n = 118) |

| Men, No. (%) | 1304 (64.4) | 698 (63.8) | 200 (67.3) | 139 (66.5) | 173 (66.5) | 31 (67.4) | 63 (53.4) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 66.0 (60.0-72.7) | 66.5 (61.4-72.1) | 67.0 (61.0-73.0) | 69.1 (60.0-75.6) | 65.5 (56.5-73.0) | 59.5 (52.0-68.0) | 59.0 (49.0-68.0) |

| Body mass index (2), median (IQR), kg/m | 26.5 (24.1-29.4) | 26.0 (23.9-28.7) | 27.6 (24.9-30.7) | 27.2 (24.7-30.1) | 26.3 (23.8-29.1) | 28.4 (25.1-32.3) | 28.2 (23.7-33.1) |

| Underweight, <18.5, No. (%) | 17 (0.9) | 10 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.5) |

| Normal weight, 18.5-24.9, No. (%) | 684 (34.3) | 419 (38.5) | 75 (25.4) | 52 (26.7) | 90 (34.8) | 10 (23.8) | 38 (32.2) |

| Overweight, 25-29.9, No. (%) | 863 (43.2) | 471 (43.3) | 127 (43.1) | 93 (47.7) | 121 (46.7) | 16 (38.1) | 35 (29.7) |

| Obese, ≥30, No. (%) | 433 (21.7) | 188 (17.3) | 92 (31.2) | 49 (25.1) | 46 (17.8) | 16 (38.1) | 42 (35.6) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 27 | 6 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | |||||||

| Current | 251 (13.0) | 121 (11.4) | 39 (13.4) | 35 (17.3) | 45 (18.8) | 4 (9.5) | 7 (7.7) |

| Former | 1028 (53.4) | 630 (59.5) | 160 (55.0) | 74 (36.6) | 114 (47.5) | 10 (23.8) | 40 (44.0) |

| Never | 646 (33.6) | 308 (29.1) | 92 (31.6) | 93 (46.0) | 81 (33.8) | 28 (66.7) | 44 (48.4) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 99 | 35 | 6 | 7 | 20 | 4 | 27 |

| Stage of disease, No. (%) | |||||||

| I | 543 (26.8) | 280 (25.6) | 86 (29.0) | 78 (37.3) | 64 (24.6) | 7 (15.2) | 28 (23.7) |

| II | 599 (29.6) | 330 (30.2) | 59 (19.9) | 52 (24.9) | 104 (40.0) | 13 (28.3) | 41 (34.8) |

| III | 824 (40.7) | 463 (42.3) | 142 (47.8) | 52 (24.9) | 92 (35.4) | 26 (56.5) | 49 (41.5) |

| Unspecified or unknown, No. (%) | 58 (2.9) | 21 (1.9) | 10 (3.4) | 27 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Tumor locationa, No. (%) | |||||||

| Colon | 1252 (62.0) | 720 (65.8) | 179 (60.3) | 127 (61.7) | 136 (52.3) | 26 (57.8) | 64 (54.2) |

| Rectal | 768 (38.0) | 374 (34.2) | 118 (39.7) | 79 (38.3) | 124 (47.7) | 19 (42.2) | 54 (45.8) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment, No. (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 458 (22.6) | 253 (23.1) | 81 (27.3) | 17 (8.1) | 63 (24.2) | 15 (32.6) | 29 (24.8) |

| No | 1564 (77.4) | 840 (76.9) | 216 (72.7) | 192 (91.9) | 197 (75.8) | 31 (67.4) | 88 (75.2) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Surgery, No. (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 1963 (97.2) | 1084 (99.3) | 269 (90.9) | 187 (89.9) | 260 (100) | 46 (100) | 117 (99.1) |

| No | 57 (2.8) | 8 (0.7) | 27 (9.1) | 21 (10.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adjuvant treatment, No. (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 596 (29.8) | 254 (23.6) | 97 (32.8) | 59 (28.4) | 95 (36.5) | 29 (65.9) | 62 (53.0) |

| No | 1406 (70.2) | 823 (76.4) | 199 (67.2) | 149 (71.6) | 165 (63.5) | 15 (34.1) | 55 (47.0) |

| Unknown/missing, No. | 22 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Adherence to physical activity guidelinesb, No. (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 1115 (65.7) | 778 (73.7) | 217 (74.6) | — | 77 (33.3) | 14 (33.3) | 29 (38.2) |

| No | 581 (34.3) | 278 (26.3) | 74 (25.5) | — | 154 (66.7) | 28 (66.7) | 47 (61.8) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 328 | 38 | 6 | 209 | 29 | 4 | 42 |

| Dietary supplement usec, No. (%) | |||||||

| Any | 682 (40.5) | 451 (42.6) | 109 (36.7) | — | 58 (24.5) | 22 (52.4) | 42 (89.4) |

| Containing folic acid | 342 (20.3) | 269 (25.4) | 60 (20.1) | — | 4 (1.7) | 1 (2.4) | 8 (17.0) |

| Unknown supplement use, No. | 341 | 34 | 0 | 209 | 23 | 4 | 71 |

| Total folate concentration (nmol/L), median (IQR) | 15.0 (9.8-24.5) | 12.5 (8.6-18.3) | 13.8 (9.8-19.0) | 17.5 (11.7-24.2) | 22.0 (15.3-31.6) | 65.1 (41.6-92.7) | 47.9 (33.3-74.5) |

| Participants with detectable folic acid concentrationsd, No. (%) | 301 (14.9) | 154 (14.1) | 47 (15.8) | 35 (16.7) | 14 (5.3) | 12 (26.1) | 39 (33.1) |

| Detectable folic acid concentrations (nmol/L), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7-1.9) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.7 (0.6-1.2) | 0.9 (0.7-3.6) | 1.4 (1.3-1.7) | 2.1 (1.4-6.8) | 2.0 (1.3-4.0) |

| Participants with detectable pABG concentrationse, No. (%) | 1946 (96.2) | 1087 (99.4) | 297 (100) | 194 (92.8) | 213 (81.9) | 41 (89.1) | 114 (96.6) |

| Detectable pABG concentrations (nmol/L), median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.0-5.4) | 4.2 (2.0-8.3) | 2.3 (1.3-3.9) | 0.7 (0.4-1.5) | 0.9 (0.6-1.6) | 0.9 (0.6-1.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) |

| Participants with detectable apABG concentrationsf, No. (%) | 1801 (89.0) | 950 (86.8) | 271 (91.2) | 195 (93.3) | 229 (88.1) | 45 (97.8) | 111 (94.1) |

| Detectable apABG concentrations (nmol/L), median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 1.1 (0.7-1.5) |

| Total energy intakeg, median (IQR), kcal/d | 1880 (1550-2278) | 1807 (1501-2160) | 2158 (1777-2639) | — | — | — | — |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 545 | 48 | 12 | 209 | 180 | 32 | 64 |

| Alcohol intakeg, median (IQR), g/d | 8.1 (0.9-20.9) | 8.5 (1.0-20.7) | 7.0 (0.6-20.6) | — | 10.4 (3.1-27.6) | — | — |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 393 | 48 | 12 | 209 | 28 | 32 | 64 |

| Follow-up timeh, median (range) | 3.7 y (4 d-15.4 y) | 4.1 y (25 d-8.4 y) | 2.9 y (23 d-5.8 y) | 5.7 y (23 d-15.4 y) | 2.1 y (4 d-5.5 y) | 2.2 y (37 d-3.7 y) | 5.1 y (0.3 y-10.1 y) |

| Deceasedi, No. (%) | 288 (14.2) | 138 (12.6) | 28 (9.4) | 66 (31.6) | 28 (10.8) | 4 (8.7) | 24 (20.3) |

| Recurrencej, No. (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 258 (13.0) | 144 (13.2) | 31 (10.4) | 26 (12.4) | 30 (13.3) | 6 (14.6) | 21 (18.1) |

| Unknown or missing, No. | 46 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 5 | 2 |

| Location of the recurrence, No. (%) | |||||||

| Locoregional | 66 (3.3) | 41 (3.8) | 7 (2.4) | 7 (3.4) | 8 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) |

| Distant | 214 (10.6) | 128 (11.7) | 26 (8.8) | 21 (10.1) | 18 (8.0) | 5 (12.2) | 16 (13.8) |

| Unknown location | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (1.7) |

| Disease-free survivalk, No. (%) | |||||||

| Participants with at least 1 event | 428 (21.7) | 215 (19.7) | 49 (16.5) | 77 (36.8) | 49 (21.8) | 7 (17.1) | 31 (26.7) |

Tumor location is defined as colon (cecum, appendix and ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon) and rectal (rectosigmoid junction and rectum) cancer. apABG = p-acetamidobenzoylglutamate; IQR = interquartile range; pABG = p-aminobenzoylglutamate.

At least 150 min/wk of moderate to vigorous physical activity.

Dietary supplement use is defined as the use of single micronutrients and/or the use of multivitamins in the last year for COLON and EnCoRe and in the last month for the ColoCare sites. Dietary supplement use was not collected in the CORSA study.

Detectable folic acid concentrations greater than 0.52 nmol/L.

Detectable pABG concentrations greater than 0.08 nmol/L.

Detectable apABG concentrations greater than 0.13 nmol/L.

Total energy and alcohol intake at diagnosis; data not shown for cohorts in which more than 50% of participants had missing FFQ data.

Follow-up time calculated using overall survival.

Overall survival events were investigated by using death from any cause in the analysis.

Recurrence is defined as colorectal cancer recurrence (event) after complete tumor resection; n = 29 have a locoregional and distant recurrence simultaneously, n = 46 with missing or incomplete recurrence data.

Disease-free survival was investigated by using a recurrence or death from any cause as events in the analysis, n = 112 of the 288 deceased patients experienced a recurrence before death.

The median (IQR) circulating concentration of folate (ie, the sum of 5-mTHF and hmTHF) was 15.0 (9.8-24.5) nmol/L. Among participants with a detectable folic acid (n = 301), pABG (n = 1946), and apABG (n = 1801) concentration, median (IQR) concentrations were 1.0 (0.7-1.9) nmol/L, 2.5 (1.0-5.4) nmol/L, and 0.7 (0.5-1.0) nmol/L, respectively. There was a substantial difference in folate and folic acid concentrations between cohorts; the US cohorts (ie, ColoCare HCI and ColoCare FHCRC) showed higher concentrations compared with the European cohorts (ie, COLON, EnCoRe, CORSA, and ColoCare HD), which is consistent with folic acid fortification being present in the United States (16). Concentrations of pABG were higher in COLON and EnCoRe compared with CORSA and the ColoCare cohorts, and ApABG showed comparable concentrations for all cohorts.

The median follow-up time for the study population was 3.7 years. During follow-up, 288 participants died from any cause and 258 participants experienced a recurrence. Recurrence cases consisted of locoregional (n = 66) and distant recurrences (n = 217); 21 participants had both a locoregional and distant recurrence. Recurrence before death was experienced by 113 of the 288 participants who died during the study.

Baseline characteristics by tertiles of folate and comparing participants with (n = 301) and without (n = 1723) detectable folic acid concentrations and by tertiles of folic acid concentrations are described in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 (available online), respectively. As expected, the most dietary supplement use was reported in the highest folate and folic acid tertile. Baseline characteristics by tertiles of pABG and apABG concentrations can be found in Supplementary Table 3 (available online), respectively.

Folates and Study Endpoints

Associations between circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, pABG, and apABG with recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival are described in Table 2. No statistically significant associations were observed for folate, pABG, and apABG, with hazard ratios ranging from 0.92 to 1.16. A moderate nonstatistically significant linear trend (P = .11) for improved overall survival, but not for recurrence and disease-free survival, was observed with increasing tertiles of folate concentrations. Similar findings for recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival were observed when using cohort-specific tertiles of folate concentrations (Supplementary Table 4, available online). Increasing tertiles of apABG concentrations showed a nonstatistically significant linear trend toward a greater risk of death (HRT2vsT1 = 1.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.91 to 1.70; and HRT3vsT1 = 1.31, 95% CI = 0.93 to 1.83; Ptrend= .15) but not for recurrence and disease-free survival. Using cohort-specific tertiles of apABG concentrations, similar trends and effect estimates were observed, but the P value for linear trend for overall survival became statistically significant (Ptrend = .03; Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Table 2.

Associations between circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, pABG, and apABG and recurrence and survival

| Folate species | Recurrencea |

Death from any cause (overall survival)b |

Recurrence or death from any cause (disease-free survival)c |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | No. of events/at risk | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adj. HR (95% CI)d | No. of deaths/at risk | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adj. HR (95% CI)d | No. of events/at risk | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adj. HR (95% CI)d | ||

| Folate (nmol/L) | |||||||||||

| Continuouse | 15.0 (9.8 to 24.5) | 258/1973 | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.21) | 288/2024 | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.11) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.05) | 428/1973 | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.11) | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | |

| T1f | 8.5 (6.3 to 9.8) | 84/672 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 98/675 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 138/672 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| T2f | 15.0 (13.2 to 17.4) | 83/659 | 1.02 (0.75 to 1.38) | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.37) | 100/675 | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.34) | 0.94 (0.70 to 1.24) | 150/659 | 1.09 (0.86 to 1.37) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.30) | |

| T3f | 30.9 (24.5 to 45.3) | 91/642 | 1.14 (0.85 to 1.54) | 1.14 (0.81 to 1.60) | 90/674 | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.21) | 0.77 (0.56 to 1.07) | 140/642 | 1.02 (0.80 to 1.29) | 0.94 (0.72 to 1.23) | |

| P trend | .35 | .40 | .45 | .11 | .98 | .58 | |||||

| Folic acid (nmol/L) | |||||||||||

| Undetectable | <0.52 (LOD) | 216/1677 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 237/1723 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 354/1677 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Detectableg | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.9) | 42/296 | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.54) | 1.18 (0.84 to 1.66) | 51/301 | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.57) | 1.14 (0.83 to 1.56) | 74/296 | 1.15 (0.89 to 1.47) | 1.19 (0.92 to 1.54) | |

| Continuoush | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.9) | 42/296 | 1.23 (1.05 to 1.44) | 1.31 (1.02 to 1.58) | 51/301 | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.42) | 1.12 (0.94 to 1.34) | 74/296 | 1.16 (1.01 to 1.33) | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | |

| T1i | 0.6 (0.6 to 0.7) | 8/98 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 10/100 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 15/98 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| T2i | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 14/99 | 1.78 (0.75 to 4.24) | 1.86 (0.76 to 4.56) | 18/101 | 1.67 (0.77 to 3.61) | 1.26 (0.56 to 2.84) | 27/99 | 1.69 (0.90 to 3.18) | 1.58 (0.82 to 3.04) | |

| T3i | 2.7 (1.9 to 5.5) | 20/99 | 2.59 (1.14 to 5.89) | 3.12 (1.22 to 8.00) | 23/100 | 2.20 (1.05 to 4.63) | 1.57 (0.70 to 3.55) | 32/99 | 2.15 (1.16 to 3.98) | 2.01 (1.01 to 3.97) | |

| P trend | .03 | .03 | .06 | .29 | .03 | .09 | |||||

| pABG (nmol/L) | |||||||||||

| Undetectable | <0.08 (LOD) | 9/69 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 13/78 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 18/69 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Detectableg | 2.5 (1.0 to 5.4) | 249/1904 | 0.99 (0.51 to 1.92) | 1.06 (0.63 to 2.14) | 275/1946 | 0.69 (0.40 to 1.21) | 0.90 (0.50 to 1.63) | 410/1904 | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.26) | 0.98 (0.60 to 1.62) | |

| Continuoush | 2.5 (1.0 to 5.4) | 249/1904 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) | 275/1946 | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.99) | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.11) | 410/1904 | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.01) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | |

| T1i | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 86/634 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 104/647 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 159/634 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| T2i | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.2) | 74/635 | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.21) | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.33) | 86/649 | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.21) | 1.16 (0.84 to 1.59) | 122/635 | 0.85 (0.67 to 1.08) | 0.95 (0.74 to 1.24) | |

| T3i | 7.7 (5.4 to 11.7) | 89/635 | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.34) | 1.03 (0.72 to 1.47) | 85/650 | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.98) | 1.08 (0.76 to 1.53) | 129/635 | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.01) | 0.94 (0.71 to 1.25) | |

| P trend | .83 | .73 | .04 | .90 | .09 | .71 | |||||

| apABG (nmol/L) | |||||||||||

| Undetectable | <0.13 (LOD) | 26/215 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 27/223 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 41/215 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| Detectableg | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 232/1758 | 1.19 (0.79 to 1.78) | 1.24 (0.82 to 1.88) | 261/1801 | 1.33 (0.90 to 1.98) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.31) | 387/1758 | 1.26 (0.92 to 1.75) | 1.20 (0.87 to 1.67) | |

| Continuoush | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 232/1758 | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.22) | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.22) | 261/1801 | 1.28 (1.11 to 1.47) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.36) | 387/1758 | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.30) | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.20) | |

| T1i | 0.4 (0.4 to 0.5) | 73/587 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 79/600 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 120/587 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| T2i | 0.7 (0.7 to 0.8) | 86/585 | 1.25 (0.91 to 1.71) | 1.23 (0.90 to 1.70) | 89/600 | 1.35 (1.00 to 1.83) | 1.25 (0.91 to 1.70) | 135/585 | 1.27 (0.99 to 1.62) | 1.21 (0.94 to 1.56) | |

| T3i | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 73/586 | 1.12 (0.81 to 1.55) | 1.08 (0.76 to 1.55) | 93/601 | 1.61 (1.19 to 2.19) | 1.31 (0.93 to 1.83) | 132/586 | 1.39 (1.08 to 1.78) | 1.21 (0.92 to 1.59) | |

| P trend | .60 | .80 | .002 | .15 | .01 | .23 | |||||

Recurrence is defined as colorectal cancer recurrence (event) after complete tumor resection. A hazard ratio greater than 1.00 should be interpreted as an increased risk of recurrence. Adj. = Adjusted; apABG = p-acetamidobenzoylglutamate; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; IQR = interquartile range; LOD = level of detection; pABG = p-aminobenzoylglutamate.

Overall survival events were investigated by using death from any cause in the analysis. A hazard ratio greater than 1.00 should be interpreted as a reduced overall survival (more deaths).

Disease-free survival was investigated by using a recurrence or death from any cause as events in the analysis. A hazard ratio greater than 1.00 should be interpreted as a reduced disease-free survival (more deaths and/or recurrences).

Adjusted for age, sex, chemotherapy status, and cohort for folate and folic acid. pABG and apABG were additionally adjusted for log2-transformed creatinine concentrations. Stage was tested as potential confounder in all models, but it did not influence the effect estimates.

Analysis performed using log2-transformed concentrations. Thus, hazard ratios represents a doubling in folate concentrations.

Tertile cut-off values for folate were 11.5 nmol/L and 20.1 nmol/L; analysis performed using non-log2-transformed concentrations.

Detectable concentrations greater than 0.52 nmol/L for folic acid, greater than 0.08 nmol/L for pABG, and greater than 0.13 nmol/L for apABG; analysis performed using log2-transformed concentrations.

Analysis performed only in the participants with a detectable value; analysis performed using log2-transformed concentrations. HRs thus represents a doubling in concentrations.

Analysis performed only for participants with detectable folic acid, pABG, or apABG. Tertile cutoff values were 0.75 nmol/L and 1.46 nmol/L for folic acid, 1.39 nmol/L and 4.18 nmol/L for pABG, and 0.59 nmol/L and 0.89 nmol/L for apABG; analysis performed using non-log2-transformed concentrations.

Comparing patients with detectable folic acid concentrations with patients without detectable folic acid for any outcome showed no statistically significant associations (Table 2). However, among patients with detectable folic acid concentrations, more recurrences were observed (HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.58) for each 2-fold increase in folic acid concentration. A statistically significant linear trend (P = .03) was observed across folic acid tertiles. Tertile 2 and 3 showed a nonstatistically significant increased risk of death compared with the lowest tertile of folic acid concentrations (HRT2vsT1 = 1.26, 95% CI = 0.56 to 3.61; and HRT3vsT1 = 1.57, 95% CI = 0.70 to 3.55). A borderline, nonstatistically significant linear trend (P = .09) was observed across folic acid tertiles for disease-free survival (HRT2vsT1 = 1.58, 95% CI = 0.82 to 3.04; and HRT3vsT1 = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.01 to 3.97) (Table 2). Analyses using cohort-specific tertiles of folic acid concentrations showed similar effect estimates and linear trends for recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival (Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Sensitivity analyses excluding participants who died or experienced a recurrence within the first 100 days after diagnosis or excluding patients who did not receive surgery or with unknown surgery status and limiting analysis to recurrence events within the first 2 years after diagnosis showed similar trends to the overall analysis (data not shown). Sensitivity analyses excluding participants from whom blood was collected during or after any type of treatment (n = 275, 14%) showed comparable linear trends with the main analyses (Supplementary Table 5, available online).

Subgroup Analyses by Clinical and Lifestyle-Related Factors

Subgroup analyses for folate concentrations are shown in Figure 1. No statistically significant associations were observed for any outcome when evaluated within individual cohorts, likely attributable to small sample sizes. Stage I patients had a statistically significantly lower risk of recurrence with higher folate concentrations (HR = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.20 to 0.58), whereas this association was not observed in stage II-III patients (I2 = 89.4%; P = .0003).

Figure 1.

Forest plots of subgroup analyses reporting hazard ratios and corresponding 95% CIs for a doubling in folate concentrations and recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival. Weights of the effect estimates are from random effects meta-analysis; square dots represent the hazard ratio of each subgroup and diamonds represent the hazard ratio of all subgroups combined. Heterogeneity among subgroups was evaluated using the I2 index. CI = confidence interval; IQR = interquartile range; Q = heterogeneity Cochran’s Q test; df = degrees of freedom; I2 = heterogeneity I2 statistic.

Supplementary Figure 1 (available online) illustrates cohort-specific tertiles of folate concentrations in relation to recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival by individual cohort. Overall, there was no sign of a dose–response relationship within cohorts for recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival.

Subgroup analyses for folic acid concentrations are shown in Figure 2. Patients with detectable folic acid concentrations who received neoadjuvant treatment (n = 63) had statistically significantly higher risk of recurrence with higher folic acid concentrations (HR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.41 to 2.92), which was not observed in patients who did not receive neoadjuvant treatment (I2 = 61.1%; P = .08).

Subgroup analyses for pABG and apABG are reported in Supplementary Figures 2 and 3 (available online), respectively.

Discussion

We investigated circulating concentrations of folate, folic acid, and folate catabolites pABG and apABG in relation to recurrence and survival among patients diagnosed with stage I-III colorectal cancer within the FOCUS international consortium. No statistically significant associations were observed for folate, pABG, and apABG concentrations. In contrast, more colorectal cancer recurrences were observed among patients with higher compared with lower circulating folic acid concentrations.

Ranges of folate concentration observed in our study population were comparable with prior studies with colorectal cancer patients measuring folate at diagnosis despite the different analytical methods used to quantify folate (29,30). Our results, showing no association between folate concentrations and recurrence and survival, are consistent with the only other smaller study in stage I-III CRC patients (29). However, when we investigated subgroups in our large consortium, a statistically significant lower risk of recurrence was observed with higher compared with lower folate concentrations in stage I patients, and not in stage II-III patients. This intriguing result has not been reported before and requires further investigation.

Unmetabolized folic acid was detected in the circulation of only 15% of included participants, which could be explained by the fact that folic acid is only detectable in case of recent and excessive intakes (28) or due to low DHFR activity. As was hypothesized, higher concentrations of folic acid were associated with increased colorectal cancer recurrence in our study population. This suggests that folic acid may facilitate growth of potentially remaining tumor cells in the body, similar as what is hypothesized concerning premalignant lesions during colorectal cancer development (2,27). Furthermore, higher concentrations of folic acid were associated with reduced disease-free survival, and higher concentrations of folic acid may also be associated with a higher risk of death. However, the association with overall survival was not statistically significant, which could potentially be explained by low sample size. Therefore, this study highlights the need for more research regarding excessive intakes through high-dose folic acid supplement use or consumption of fortified foods in relation to cancer prognosis.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, investigating the association between folate catabolites and colorectal cancer recurrence and survival. No associations between folate catabolites and colorectal cancer recurrence and survival were observed. However, a moderate trend toward more deaths with increasing apABG concentrations, the main folate catabolite, was observed, which warrants replication. Folate catabolism plays a role in regulating folate homeostasis, and catabolites are suggested to be potential functional markers of folate status (21). Increased folate catabolism has been reported earlier in colon tumor cells (20), and recently increased circulating concentrations of folate catabolites are hypothesized to be a result of increased inflammation (42). The role of folate catabolites in colorectal cancer recurrence and survival remains to be elucidated.

To our knowledge, this is the first large multicohort consortium investigating concentrations of folate, folic acid, and folate catabolites in relation to colorectal cancer recurrence and survival including over 2000 stage I-III colorectal cancer patients. Quantifying folate using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry allowed us to discern separate folate species, including folate catabolites, and is therefore considered a more powerful method to measure folate status (28,36) compared with the microbiological assay used in previous studies (29,30). Patients in this study population diagnosed with stage I-III colorectal cancer were included from several European and US cohort studies, which enabled us to explore a wide range of folate, folic acid, and catabolite concentrations. Because of the large sample size, we were also able to conduct subgroup analyses. Although our sample size was large, we acknowledge that a relatively small proportion of participants originated from US cohorts (n = 188), which did not allow us to comprehensively compare European and US cohorts. Median follow-up time was relatively short at 3.7 years, although it should be noted that most recurrences tend to occur in the first 2-3 years after colorectal cancer diagnosis (43‐45) and we had a broad range with a maximum follow-up time of 15.4 years. In addition, concentrations of folate species were assessed in only a single sample, which is a further limitation. A single sample may not capture past exposures and exposures after cancer diagnosis related to lifestyle factors or daily variability in metabolites (44). Last, colorectal cancer–specific survival could not be investigated because cause of death was not available for all cohorts.

Future research investigating colorectal cancer prognosis should include unmetabolized folic acid and folate catabolites. The folate catabolites pABG and apABG have not been extensively studied in the context of colorectal cancer, and they might provide a broader understanding of folate kinetics in colorectal cancer patients. Furthermore, the importance of unmetabolized folic acid, and the potential different biochemical effect compared with natural folate, in relation to human health is still unclear (28,46) while dietary supplement use is common among cancer patients and food fortification is applied in 81 countries (47). Our current findings provide relevant leads for future studies on the underlying mechanisms. A potentially interesting mechanism might by through immune function, because increased unmetabolized folic acid concentrations have also been linked to reduced immune function in the past (48). Furthermore, it might be worthwhile to consider variations in genes related to FOCM, such as MTHFR and DHFR (49), as well as potential genetic predisposition for colorectal cancer recurrence and survival (45,50,51) when investigating whether associations with recurrence and survival potentially vary between persons with a different genetic background.

We reported that folate and folate catabolite concentrations in our international prospective cohort study population were not associated with colorectal cancer recurrence and survival. We observed that higher folic acid concentrations are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer recurrence in stage I-III colorectal cancer patients. A better understanding of the potential harmful effects of unmetabolized folic acid in the circulation, specifically among colorectal cancer patients, is warranted. Although dietary intake of folic acid through fortified foods or dietary supplements was not assessed in the current study, awareness may be required concerning the potential risk of excessive intakes, particularly among patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer.

Funding

This work was supported by Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds (WKOF) and World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF International); the World Cancer Research Fund International Regular Grant Programme (WKOF/WCRF, the Netherlands, project no. 2014/1179); Alpe d’Huzes/Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding, the Netherlands, project no. UM 2010-4867, UM 2012-5653, UW 2013-5927, UW 2015-7946); ERA-NET on Translational Cancer Research (TRANSCAN/Dutch Cancer Society, the Netherlands, project no. UW 2013-6397, UM 2014-6877); the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, the Netherlands); the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, Austria; project no. I 2104-B26); the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Germany; project no. 01KT1503); The Research Council of Norway (RCN, Norway; project no. 246402/H10); the National Cancer Institute (NCI, United States; project no. R01 CA189184, U01 CA206110, R01 CA207371); the Huntsman Cancer Foundation (HCI, U.S.); the National Institutes of Health (NIH, United States; grant no. P30 CA015704, P30 CA042014, U01 CA152756, R01 CA194663, and R01 CA220004) coordinated by the ERA-NET, JTC 2013 call on Translational Cancer Research (TRANSCAN). In addition, D. E. Kok is supported by a Veni grant (grant no. 016.Veni.188.082) of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. W. M. Grady is funded by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the Seattle Translational Tumor Research Program, and the Cottrell Family. A. N. Holowatyj was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the National Human Genome Research Institute (grant no. T32 HG008962). E. H. van Roekel was financially supported by Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds (WKOF) as part of the World Cancer Research Fund International grant program (grant no. 2016/1620). J. L. Koole and M. J. L. Bours were financially supported by Kankeronderzoekfonds Limburg as part of Health Foundation Limburg (grant no. 00005739).

Notes

Role of the funder: The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: Michael M. Bergmann is founder of the biotechnology company Vacthera BioTech GmbH (Vienna, Austria) and received a consultant fee (<2000€) from Dr Falk GmbH (Vienna, Austria). Cornelia M. Ulrich (Director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, U.S.) oversees research funded by several pharmaceutical companies but has not received funding directly herself that could constitute a conflict to the current work.

Role of the authors: BG, DEK, FJBD, MJLB, ABU, PMU, MPW, AG, CMU, and EK: Conceptualization. AG, BG, and GK: Data curation. AJMRG: Formal analysis. BG, NH, ABU, PMU, MPW, AG, CMU, and EK: Funding acquisition. AJMRG, BG, DEK, FJBD, AnH, SB, EvR, MJLB, TG, JLK, and JO: Investigation. AJMRG, AB, and GK: Methodology. BG, DEK, FJBD, ABU, PMU, MPW, AG, CMU, and EK: Project Administration. AJMRG, AU, BG, DEK, FJBD, AnH, SB, EvR, MMB, JB, MJLB, HB, SOB, MPB, ThGr, TG, EH, MH, LCH, JDJ, ETPK, RK, TK, JLK, KK, EAK, FMK, GK, CIL, TL, JO, TBP, CLS, PS, MAS, PSK, MCS, ERS, PD, HKH, MZ, KV, FJV, EW, and NH: Resources. AJMRG and AU: Software. DEK, FJBD, ABU, PMU, MPW, AG, CMU, and EK: Supervision. AU: Validation. AJMR: Visualization. AJMR: Writing-original draft. All co-authors: Writing-review and editing.

Data availability statement

Because the data consist of identifying cohort information, some access restrictions apply, and therefore they cannot be made publicly available. Data will be shared with permission, from the acting committee of the corresponding cohorts. Requests for data can be sent to Prof. Ellen Kampman, Division of Human Nutrition and Health, Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands (e-mail: ellen.kampman@wur.nl).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of all COLON, EnCoRe, ColoCare and CORSA study participants. COLON The authors would like to thank the COLON investigators at Wageningen University & Research and the involved clinicians in the participating hospitals. EnCoRe We would like to thank all participants of the EnCoRe study and the health professionals in the 3 hospitals involved in the recruitment of participants of the study: Maastricht University Medical Center+, VieCuri Medical Center, and Zuyderland Medical Center. We would also like to thank the MEMIC center for data and information management for facilitating the logistic processes and data management of our study. Finally, we would like to thank the research dieticians and research assistant who are responsible for patient inclusion and follow-up, performing home visits, as well as data collection and processing. CORSA We thanks all those who agreed to participate in the CORSA study, including the patients, as well as all the physicians and students. ColoCare The authors thank all ColoCare Study participants and the ColoCare Study teams at multiple locations worldwide. In addition ColoCare HD acknowledges the liquid biobank of the National Center for Tumor Diseases for storage of the blood samples according to the SOPs of the Biomaterialbank Heidelberg (BMBH) and ColoCare HCI acknowledges the clinical teams, the Biospecimen and Molecular Pathology Shared Resource, the Data Management Team, the Research Informatics Shared Resource and the Biostatistics Shared Resource.

References

- 1. Chen J, Xu X, Liu A, et al. Folate and cancer: epidemiological perspective In: Lynn B, ed. Folate in Health and Disease. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2009:215–243. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mason JB. Unraveling the complex relationship between folate and cancer risk. Biofactors. 2011;37(4):253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim YI. Folate: a magic bullet or a double edged sword for colorectal cancer prevention? Gut. 2006;55(10):1387–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith AD, Kim Y-I, Refsum H. Is folic acid good for everyone? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(3):517–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi SW, Mason JB. Folate status: effects on pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis. J Nutr. 2002;132(8):2413s–2418s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly P, McPartlin J, Goggins M, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid in serum: acute studies in subjects consuming fortified food and supplements. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(6):1790–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim YI. Folate, colorectal carcinogenesis, and DNA methylation: lessons from animal studies. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44(1):10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams EA. Folate, colorectal cancer and the involvement of DNA methylation. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(4):592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bailey LB. Folate in Health and Disease. 2nd ed Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis LLC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ulrich CM, Potter JD. Folate supplementation: too much of a good thing? Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2006;15(2):189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller JW, Ulrich CM. Folic acid and cancer: where are we today? Lancet. 2013;381(9871):974–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suitor CW, Bailey LB. Dietary folate equivalents: interpretation and application. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(1):88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Said HM, Mohammed ZM. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins: an update. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22(2):140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pfeiffer CM, Fazili Z, McCoy L, et al. Determination of folate vitamers in human serum by stable-isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry and comparison with radioassay and microbiologic assay. Clin Chem. 2004;50(2):423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, et al. Changes in diet, physical activity, and supplement use among adults diagnosed with cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(3):323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. FDA. Food standards: amendment of standards of identity for enriched grain products to require addition of folic acid; final rule (21 CFR Parts 136, 137, and 139). Fed Reg. 1996;61:8781–8797. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bailey SW, Ayling JE. The extremely slow and variable activity of dihydrofolate reductase in human liver and its implications for high folic acid intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(36):15424–15429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McPartlin J, Weir DG, Halligan A, et al. Accelerated folate breakdown in pregnancy. Lancet. 1993;341(8838):148–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niesser M, Demmelmair H, Weith T, et al. Folate catabolites in spot urine as non-invasive biomarkers of folate status during habitual intake and folic acid supplementation. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suh JR, Herbig AK, Stover PJ. New perspectives on folate catabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21(1):255–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolfe JM, Bailey LB, Herrlinger-Garcia K, et al. Folate catabolite excretion is responsive to changes in dietary folate intake in elderly women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(4):919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Álvarez-Sánchez B, Priego-Capote F, Mata-Granados JM, et al. Automated determination of folate catabolites in human biofluids (urine, breast milk and serum) by on-line SPE–HILIC–MS/MS. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217(28):4688–4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fox JT, Stover PJ. Chapter 1 folate‐mediated one‐carbon metabolism In: Litwack G, ed. Vitamins & Hormones. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2008:1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim YI. Folate and colorectal cancer: an evidence-based critical review. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(3):267–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newman AC, Maddocks O. One-carbon metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(12):1499–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryan BM, Weir DG. Relevance of folate metabolism in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;138(3):164–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bailey LB, Stover PJ, McNulty H, et al. Biomarkers of nutrition for development—folate review. J Nutr. 2015;145(7):1636S–1680S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yan M, Ho C, Winquist E, et al. Pretreatment serum folate levels and toxicity/efficacy in colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid. Clin Colorectal Canc. 2016;15(4):369–376.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Björkegren K, Larsson A, Johansson L, et al. Serum vitamin B12 and folate status among patients with chemotherapy treatment for advanced colorectal cancer AU-Byström, Per. Upsala J Med Sci. 2009;114(3):160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wolpin BM, Wei EK, Ng K, et al. Prediagnostic plasma folate and the risk of death in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3222–3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winkels RM, Heine-Bröring RC, Van Zutphen M, et al. The COLON study: colorectal cancer: longitudinal, observational study on nutritional and lifestyle factors that may influence colorectal tumour recurrence, survival and quality of life. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Roekel EH, Bours MJ, de Brouwer CP, et al. The applicability of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health to study lifestyle and quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2014: Cebp. 1144.2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. Ulrich CM, Gigic B, Bohm J, et al. The ColoCare study—a paradigm of transdisciplinary science in colorectal cancer outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2018; doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-18-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hannisdal R, Ueland PM, Eussen SJ, et al. Analytical recovery of folate degradation products formed in human serum and plasma at room temperature. J Nutr. 2009;139(7):1415–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hannisdal R, Ueland PM, Svardal A. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of folate and folate catabolites in human serum. Clin Chem. 2009;55(6):1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bird JK, Ronnenberg AG, Choi S-W, et al. Obesity is associated with increased red blood cell folate despite lower dietary intakes and serum concentrations. J Nutr. 2015;145(1):79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mason JB, Choi S-W. Effects of alcohol on folate metabolism: implications for carcinogenesis. Alcohol. 2005;35(3):235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pfeiffer CM, Sternberg MR, Fazili Z, et al. Folate status and concentrations of serum folate forms in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(12):1965–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kiblawi R, Holowatyj AN, Gigic B, et al. One-carbon metabolites, B-vitamins and associations with systemic inflammation and angiogenesis biomarkers among colorectal cancer patients: results from the ColoCare Study. Br J Nutr. 2020;123(10):1132–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ringland C, Arkenau H-T, O'Connell D, et al. Second primary colorectal cancers (SPCRCs): experiences from a large Australian Cancer Registry. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(1):92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sampson JN, Boca SM, Shu XO, et al. Metabolomics in epidemiology: sources of variability in metabolite measurements and implications. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2013;22(4):631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Thibodeau SN, et al. DNA mismatch repair status and colon cancer recurrence and survival in clinical trials of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(11):863–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ulrich CM. Folate and cancer prevention: a closer look at a complex picture. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(2):271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wald NJ, Morris JK, Blakemore C. Public health failure in the prevention of neural tube defects: time to abandon the tolerable upper intake level of folate. Public Health Rev. 2018;39(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Troen AM, Mitchell B, Sorensen B, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid in plasma is associated with reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity among postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2006;136(1):189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Askari BS, Krajinovic M. Dihydrofolate reductase gene variations in susceptibility to disease and treatment outcomes. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(8):578–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, et al. Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1261–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ose J, Botma A, Balavarca Y, et al. Pathway analysis of genetic variants in folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism-related genes and survival in a prospectively followed cohort of colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2018;7(7):2797–2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Because the data consist of identifying cohort information, some access restrictions apply, and therefore they cannot be made publicly available. Data will be shared with permission, from the acting committee of the corresponding cohorts. Requests for data can be sent to Prof. Ellen Kampman, Division of Human Nutrition and Health, Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands (e-mail: ellen.kampman@wur.nl).