Abstract

Background: Our objectives were to estimate the association of gender-based violence (GBV) experience with the risk of sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition in HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women, to compare the STI risks associated with recent and lifetime GBV exposures, and to quantify whether these associations differ by HIV status.

Methods: We conducted a multicenter, prospective cohort study in the Women's Interagency HIV Study, 1994–2018. Poisson models were fitted using generalized estimating equations to estimate the association of past 6-month GBV experience (physical, sexual, or intimate partner psychological violence) with subsequent self-reported STI diagnosis (gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, or trichomoniasis).

Results: Data from 2868 women who reported recent sexual activity comprised 12,069 person-years. Higher STI risk was observed among HIV-seropositive women (incidence rate [IR] 5.5 per 100 person-years) compared with HIV-seronegative women (IR 4.3 per 100 person-years). Recent GBV experience was associated with a 1.28-fold (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.99, 1.65) risk after adjustment for HIV status and relevant demographic, socioeconomic, and sexual risk variables. Other important risk factors for STI acquisition included unstable housing (adjusted incidence rate ratio [AIRR] 1.81, 95% CI 1.32–2.46), unemployment (AIRR 1.42, 95% CI 1.14–1.76), transactional sex (AIRR 2.06, 95% CI 1.52–2.80), and drug use (AIRR 1.44, 95% CI 1.19–1.75). Recent physical violence contributed the highest risk of STI acquisition among HIV-seronegative women (AIRR 2.27, 95% CI 1.18–4.35), whereas lifetime GBV experience contributed the highest risk among HIV-seropositive women (AIRR 1.59, 95% CI 1.20–2.10).

Conclusions: GBV prevention remains an important public health goal with direct relevance to women's sexual health.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, sexual violence, physical violence, sexually transmitted infections, HIV

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV), defined as physical, sexual, psychological, or economic abuse of girls and women,1 is a risk factor for acquisition of HIV2 and other sexually transmitted infections (STI).3–6 GBV includes abuse within an intimate relationship (intimate partner violence [IPV]) as well as non-partner violence. A systematic review and meta-analysis of IPV and HIV among women found that the experience of physical, sexual, or psychological IPV was associated with a 1.41-fold (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.73) increased odds of HIV-seropositive status in cross-sectional studies, and a 1.28-fold (95% CI 1.00–1.64) increased risk of HIV seroconversion in longitudinal studies.7

Associations between the experience of GBV and the acquisition of other STIs3,4 or the presence of STI symptoms5,6 have been also been documented.8 Since an increased risk of IPV after disclosure of HIV9,10 or other STIs11 has been observed, longitudinal study designs are valuable in elucidating associations between GBV and STI.

High rates of lifetime and recent GBV experience have been documented among women living with HIV (WLHIV),12–14 with rates of recent physical or sexual IPV victimization ranging from 20% (among 286 sexually active WLHIV in the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study, 1998)15 to 42% (among 239 WLHIV recruited from an HIV clinic in Baltimore, 2014–2015).14,16,17 Recently, Decker et al. reported that 61% of Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) participants had a lifetime history of physical or sexual violence at enrollment.14

Among WLHIV, GBV experience has been linked to less engagement in medical care,18 lower self-reported antiretroviral therapy adherence,9 lower rates of viral load suppression,9 having a CD4 count <200,16 and increased mortality.19 In addition, Ghosh et al. recently demonstrated that chronic sexual abuse and depression are associated with levels of immune biomarkers related to inflammation and wound healing in the female reproductive tract, with some differences observed by HIV status.20 Thus, damage to the genital tract and the mental health sequelae of abuse may interact with the immune system differentially by HIV status to increase susceptibility to STI. In summary, associations between GBV experience and STI acquisition may differ by HIV status.

There are several pathways by which GBV can directly and indirectly increase risk of HIV/STI acquisition. Forced sex can directly increase susceptibility to HIV infection via damage to the genital tract and resultant alterations to the local immune system.20,21 In addition, higher odds of HIV/STI diagnosis22–24 and HIV/STI risk behaviors22,25,26 have been described among male perpetrators of IPV.

Further, past GBV experience may indirectly heighten the risk of STI acquisition via psychosocial mechanisms. Past experiences of violence in response to requests for condom use can result in fear of condom negotiation and lower rates of condom use.27,28 Finally, survivors of abuse may have less economic stability14,29 and higher rates of depression,30,31 post-traumatic stress disorder,30,32 and substance use,28 all of which may increase vulnerability to sexual risk.33–35 Thus, experiences of GBV may increase both short-term and long-term risks of STI acquisition.

Considering evidence that GBV increases risk of STI and is associated with adverse health outcomes, particularly among WLHIV, there is a need to better characterize the association between GBV exposure and STI acquisition among women with and without HIV. Our primary objective was to estimate the association between recent GBV experience and subsequent risk of STI acquisition in a cohort representative of U.S. WLHIV and HIV-seronegative counterparts. In addition, we compared the risks of STI acquisition associated with different forms of recent GBV as well as lifetime GBV before study entry, and we quantified whether these associations differed by HIV status.

Methods

Study participants and design

The WIHS, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is the largest prospective cohort study of HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women in the U.S.36,37 HIV-seropositive participants are representative of U.S. WLHIV in demographics and HIV risk profile.36

WIHS recruitment and study protocols have been described elsewhere.36–38 Briefly, the initial recruitment occurred during 1994–1995 at six U.S. sites. Participants were recruited from clinical sites such as HIV primary care clinics and hospital-based programs, as well as community-based programs including women's support groups and drug rehabilitation programs.36 Frequency matching was used to achieve balance on demographic and HIV risk variables among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative participants.36 Additional participants were recruited in 2001–2002, 2011–2012, and 2013–2015, at which time four southern U.S. sites were added.37,38 Study visits occur every 6 months and include standardized face-to-face interviews, physical and gynecologic examinations, and laboratory specimen collection. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Unit of analysis

We used two consecutive study visits (referred to as a visit pair) as the unit of analysis. Individuals could contribute multiple visit pairs. Within each visit pair, GBV exposure and time-varying covariates were assessed at the first (index) visit, and STI diagnosis was assessed at the next visit. Data on recent GBV experience and time-varying covariates refer to experience since the participant's previous WIHS study visit (generally a period of 6 months and no longer than a year).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included data from participants at the Bronx, NY, Brooklyn, NY, Washington, DC, Chicago, IL, and San Francisco, CA sites (1994–2018), and the Chapel Hill, NC, Atlanta, GA, Miami, FL, and Birmingham, AL/Jackson, MS sites (2013–2018). The southern sites were grouped together in analyses due to fewer years of follow-up. Data from the Los Angeles, CA site were excluded, because GBV data were not consistently collected.

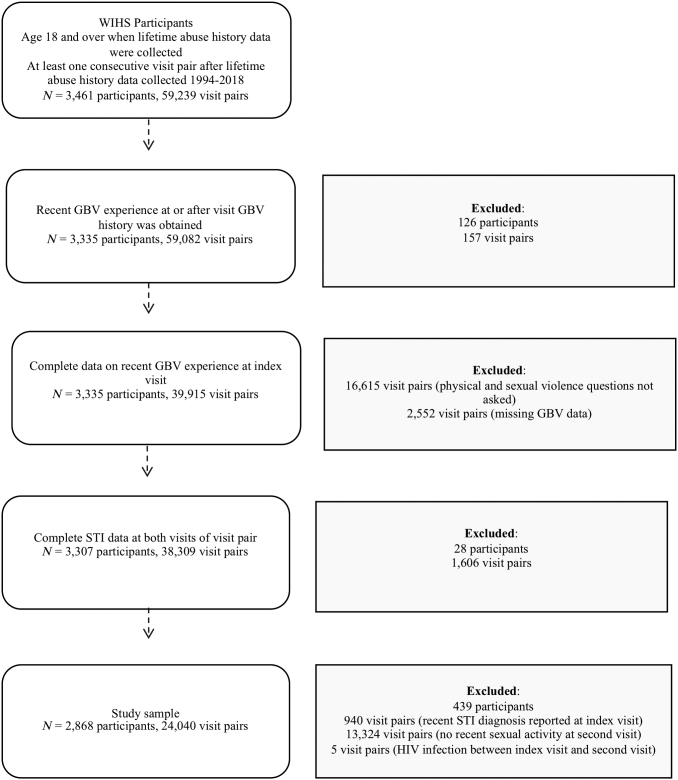

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the analysis if they were ≥18 years old when lifetime abuse history was assessed, and subsequently contributed at least one visit pair between 1994 and 2018 (N = 3461 participants, 59,239 visit pairs) (Fig. 1). Visit pairs were included if the participant provided complete data on recent (past 6-month) GBV experience at the index visit and recent STI diagnosis at the index and follow-up visits. Exclusion criteria on the visit pair level included recent STI diagnosis at the index visit (n = 940); no recent sexual activity at the second visit (n = 13,324); and HIV seroconversion over the course of a visit pair (n = 5). The final sample consisted of 24,040 visit pairs from 2868 participants.

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of participants.

Measurement of exposure, outcome, and covariates

Physical and sexual violence data were collected at all study visits during 1994–1999, at alternating visits during 2000–2013, and subsequently at every visit. Intimate partner psychological violence data were collected at every study visit. Only visits at which all three forms of violence were assessed were eligible for inclusion in this analysis.

Assessment of physical and sexual violence was based on the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale.39 Physical violence was assessed with the question “Since your [previous] study visit, have you experienced serious physical violence (physical harm by another person)? By that I mean were you ever hurt by a person using an object or were you ever slapped, hit, punched, kicked?” Sexual violence was assessed with the question “Since your [previous] study visit, has anyone pressured or forced you to have sexual contact? By sexual contact I mean them touching your sexual parts, you touching their sexual parts, or sexual intercourse.” Questions about physical and sexual violence did not specify a perpetrator relationship.

In contrast, assessment of psychological violence was specific to IPV. Intimate partner psychological violence consisted of controlling behaviors perpetrated by a current or former partner: threatening to hurt or kill the participant, or preventing the participant from entering or leaving her home, accessing medical care, having a job, or pursuing education. Participants who reported experience of any form of violence were referred to counseling services; GBV treatment data were not collected.

We defined recent GBV as experience of physical violence, sexual violence, or intimate partner psychological violence in the past 6 months. At each index visit, participants who endorsed recent experience of any form of GBV were considered exposed, whereas participants who reported not experiencing any form of GBV were considered unexposed.

The outcome was self-reported diagnosis of STI at the second visit of a visit pair. The WIHS assesses STI at all study visits with the interview question, “Since your [previous] study visit, have you been told by a health care provider that you had gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, genital herpes, genital warts, or trichomoniasis?” We did not consider genital herpes or genital warts as incident infections, as HSV and HPV cause latent infection and diagnosis likely would not reflect a recent infection. Due to the low event rate, we used a composite outcome of incident gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, or trichomoniasis.

Data for all variables except HIV status, year of study enrollment, and study site were self-reported. Variables measured at WIHS entry included race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and lifetime GBV history at baseline (physical, sexual, or intimate partner psychological violence, or no GBV). Time-varying data were available for HIV status, WIHS site, marital status, residence, employment, income, drug use, transactional sex, number of recent sex partners, and condom use.

Marital status was categorized as married, living together, never married, or other. Residence was categorized as own house/apartment, parent's residence, someone else's residence, or unstable housing (including a shelter, boarding house, street, correctional facility, or residential substance use treatment facility). Average yearly household income was dichotomized as ≤$18,000 or >$18,000.14 Drug use included injected and non-injected recreational drugs, and was categorized as any or none. Transactional sex was defined as trading sex for drugs, money, or shelter. Number of recent sex partners was collected as a continuous variable and was categorized as zero, one, two to four, or more than four, based on the data distribution.

Separate questions addressed past 6-month condom non-use for vaginal and anal intercourse. For both questions, response options included yes (did not always use condoms), no (always used condoms), and N/A (did not have vaginal or anal intercourse, respectively). Categorical variables were modeled as nominal variables.

Statistical methods

We compared the distributions of covariates by recent GBV experience, using data from each participant's first visit in the analysis. To estimate rates of STI, we fitted population-averaged Poisson models using generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation structure to account for within-subject correlation. Crude incidence rates (IRs) and incidence rate ratios of STI per 100 person-years were estimated by levels of the exposure and covariates. An offset term for time in days (log-transformed) was used to account for unequal times between visits.

Multivariable models were used to estimate the risk of STI acquisition after GBV experience. Covariates were selected using a directed acyclic graph approach.40 We did not adjust for variables likely to mediate the association between GBV and STI acquisition, i.e., condom use and number of recent sex partners.41 Specifically, we conceptualized condom use and number of sex partners as subsequent effects of recent GBV experience (the latter was previously demonstrated in this cohort),41 whereas other sexual risk-related variables were conceptualized as preceding and contributing to acute GBV risk.

The adjusted model controlled for HIV status as well as age, race/ethnicity, year of WIHS enrollment, study site, marital status, residence, employment, household income, GBV history at baseline, recent drug use, and recent transactional sex. The adjusted model used a complete case approach for missing data due to low levels of missingness (<3% per variable).

To compare the risks of STI acquisition associated with different forms of GBV, we included recent physical violence, recent sexual violence, recent intimate partner psychological violence, and lifetime GBV history as separate independent variables in a mutually adjusted model. This model included the same covariates used in the main adjusted model. We assessed whether the association of GBV with STI acquisition differed by HIV status by adding an interaction term for GBV and HIV status to the adjusted model. Finally, we assessed whether the associations of different forms of GBV with STI acquisition differed by HIV status by including interaction terms for each form of GBV and HIV status in the mutually adjusted model.

Analyses were conducted by using Stata 13.1 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX), using an alpha level of 0.05 for statistical significance.

Results

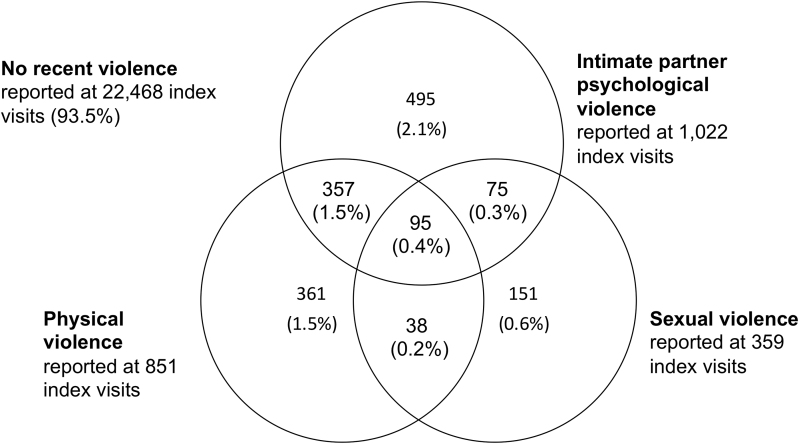

Overall, 2868 participants contributed 24,040 visit pairs to the analysis (12,069 person-years). The median number of visit pairs contributed per participant was 6 (range 1–31, interquartile range 3–12). Recent GBV experience was reported at 1572 index visits (7%) by 778 participants (Fig. 2), most commonly intimate partner psychological violence (n = 1022 index visits).

FIG. 2.

Forms of GBV reported in the WIHS, 1995–2018 (N = 24,040 visits). Percentages do not sum to 100.0 due to rounding. Questions about physical and sexual violence did not specify a perpetrator relationship, whereas psychological violence was specific to controlling behaviors perpetrated by a current or former partner. GBV, gender-based violence; WIHS, Women's Interagency HIV Study.

We assessed baseline characteristics at the first visit that each participant contributed to the analysis. Recent GBV experience was reported at 304 (11%) of 2868 participants' first index visits (Table 1). The majority (71%) of participants were HIV-seropositive at their first index visit; HIV-seronegative women reported a higher prevalence of recent GBV (13% vs. 9%). Demographic characteristics associated with recent GBV experience included study site (not shown) and younger age. GBV prevalence was highest among women enrolled in 1994–1995 (13%) and decreased subsequently (8%–9%). The majority (69%) of participants reported GBV history at baseline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants at First Index Visit, by Recent Experience of Gender-Based Violence

| Total (N = 2868) |

No recent GBVa,b (n = 2564) |

Recent GBVa,b (n = 304) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (column %) | N (row %) | ||

| HIV status at visita,b | |||

| HIV-seronegative | 822 (29) | 712 (87) | 110 (13) |

| HIV-seropositive | 2046 (71) | 1852 (91) | 194 (9) |

| Age at visit, median (IQR) | 39 (32–45) | 39 (33–45) | 37 (31–44) |

| Study enrollment yearc | |||

| 1994–1995 | 1329 (46) | 1159 (87) | 170 (13) |

| 2001–2002 | 602 (21) | 553 (92) | 49 (8) |

| 2011–2013 | 279 (10) | 253 (91) | 26 (9) |

| 2013–2015 | 658 (23) | 599 (91) | 59 (9) |

| Race/ethnicityc | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 2027 (71) | 1816 (90) | 211 (10) |

| Hispanic | 461 (16) | 418 (91) | 43 (9) |

| White non-Hispanic | 294 (10) | 258 (88) | 36 (12) |

| Other | 86 (3) | 72 (84) | 14 (16) |

| Marital statusb | |||

| Married | 579 (21) | 526 (91) | 53 (9) |

| Living with partner | 346 (13) | 293 (85) | 53 (15) |

| Never married | 1010 (37) | 910 (90) | 100 (10) |

| Other | 803 (29) | 721 (90) | 82 (10) |

| Residenceb | |||

| Own residence | 2153 (75) | 1956 (91) | 197 (9) |

| Parent's residence | 203 (7) | 186 (92) | 17 (8) |

| Someone else's residence | 319 (11) | 268 (84) | 51 (16) |

| Unstable housing | 192 (7) | 153 (80) | 39 (20) |

| Educational attainmentc | |||

| <High school | 981 (34) | 867 (88) | 114 (12) |

| ≥High school | 1885 (66) | 1696 (90) | 189 (10) |

| Employmentb | |||

| Employed | 955 (33) | 888 (93) | 67 (7) |

| Unemployed | 1911 (67) | 1674 (88) | 237 (12) |

| Household incomeb | |||

| ≤$18,000 | 1882 (66) | 1667 (89) | 215 (11) |

| >$18,000 | 812 (28) | 747 (92) | 65 (8) |

| Missing | 174 (6) | 150 (86) | 24 (14) |

| GBV history at baselinec | |||

| No | 881 (31) | 853 (97) | 28 (3) |

| Yes | 1975 (69) | 1699 (86) | 276 (14) |

| Recent drug useb | |||

| No | 2059 (72) | 1910 (93) | 149 (7) |

| Yes | 807 (28) | 652 (81) | 155 (19) |

| Recent transactional sexb | |||

| No | 2768 (97) | 2498 (90) | 270 (10) |

| Yes | 98 (3) | 64 (65) | 34 (35) |

| Number of recent sex partnersb | |||

| 0 | 584 (20) | 550 (94) | 34 (6) |

| 1 | 1733 (61) | 1571 (91) | 162 (9) |

| 2–4 | 472 (17) | 393 (83) | 79 (17) |

| >4 | 77 (3) | 48 (62) | 29 (38) |

| Condom use with vaginal intercourseb | |||

| Always used condoms | 1121 (39) | 1024 (91) | 97 (9) |

| Did not always use condoms | 1016 (36) | 866 (85) | 150 (15) |

| No vaginal intercourse | 723 (25) | 668 (92) | 55 (8) |

| Condom use with anal intercourseb | |||

| Always used condoms | 84 (3) | 75 (89) | 9 (11) |

| Did not always use condoms | 99 (4) | 75 (76) | 24 (24) |

| No anal intercourse | 2675 (94) | 2406 (90) | 269 (10) |

Physical violence, sexual violence, and/or intimate partner psychological violence.

Time-varying variables, measured with respect to the past 6 months.

Variables measured at baseline.

GBV, gender-based violence; IQR, interquartile range.

Incident STI was reported at 581 visit pairs by 444 participants (Table 2). The most commonly reported incident STI was trichomoniasis (n = 369 cases, 299 unique participants, IR 3.2 per 100 person-years), followed by chlamydia (n = 100 cases, 87 participants, IR 0.9 per 100 person-years). Fewer diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease (n = 76 cases, 63 participants, IR 0.6 per 100 person-years), gonorrhea (n = 51 cases, 48 participants, IR 0.4 per 100 person-years), and syphilis (n = 41 cases, 36 participants, IR 0.4 per 100 person-years) were reported.

Table 2.

Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the Women's Interagency HIV Study, 1995–2018

| STI | No. of incident STI cases | No. of unique participants | IR (95% CI) per 100 person-years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trichomoniasis | 369 | 299 | 3.2 (2.9–3.6) |

| Chlamydia | 100 | 87 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | 76 | 63 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) |

| Gonorrhea | 51 | 48 | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) |

| Syphilis | 41 | 36 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

| Total | 581a | 444b | 5.1 (4.6–5.6) |

N = 24,040 visit pairs contributed by 2868 participants.

Number of follow-up visits at which any STI was reported; more than one STI could be reported at a follow-up visit.

Number of participants reporting any STI at a follow-up visit.

CI, confidence interval; IR, incidence rate; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The overall IR of STI was 5.1 per 100 person-years (95% CI 4.6–5.6). Recent GBV experience was bivariately associated with 2.17-fold (95% CI 1.71–2.75) risk of STI acquisition (Table 3). The risk of STI acquisition did not significantly differ between women who had vaginal intercourse in the past 6 months and always used condoms versus those who did not always use condoms (Wald test p-value = 0.21). A similar pattern was observed with respect to condom use with anal intercourse (Wald test p-value = 0.74).

Table 3.

Incidence Rates, Crude Incidence Rate Ratios, and Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratios of Sexually Transmitted Infection Acquisition

| IR per 100 person-years (95% CI) | Crude IRR (95% CI) | AIRRa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recent GBV experienceb,c | |||

| No | 4.7 (4.2–5.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 10.3 (8.2–13.1) | 2.17 (1.71–2.75) | 1.28 (0.99–1.65) |

| HIV status at visitc | |||

| HIV-seronegative | 4.3 (3.6–5.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| HIV-seropositive | 5.5 (4.9–6.1) | 1.25 (1.01–1.55) | 1.28 (1.03–1.58) |

| Age at visit | |||

| 18–29 | 8.2 (6.3–10.8) | 2.12 (1.59–2.83) | 1.93 (1.42–2.62) |

| 30–39 | 6.5 (5.7–7.5) | 1.57 (1.30–1.90) | 1.54 (1.26–1.88) |

| 40–49 | 4.2 (3.6–4.9) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 50–81 | 3.4 (2.7–4.3) | 0.78 (0.60–1.02) | 0.75 (0.58–0.99) |

| Year of enrollment in WIHSd | |||

| 1994–1995 | 5.3 (4.7–6.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2001–2002 | 2.7 (2.1–3.6) | 0.51 (0.37–0.68) | 0.57 (0.42–0.77) |

| 2011–2012 | 3.7 (2.5–5.4) | 0.69 (0.46–1.05) | 0.62 (0.40–0.95) |

| 2013–2015 | 9.1 (7.4–11.0) | 1.68 (1.34–2.12) | 1.44 (0.15–14.08) |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6.0 (5.4–6.7) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Hispanic | 2.7 (2.0–3.7) | 0.46 (0.34–0.64) | 0.60 (0.43–0.83) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.9 (1.9–4.4) | 0.49 (0.32–0.74) | 0.46 (0.30–0.70) |

| Other | 4.9 (3.0–8.0) | 0.84 (0.49–1.45) | 0.95 (0.55–1.64) |

| Marital statusc | |||

| Married | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Living with partner | 4.6 (3.6–5.9) | 1.75 (1.25–2.44) | 1.42 (1.01–1.99) |

| Never married | 7.2 (6.3–8.3) | 2.52 (1.93–3.28) | 1.73 (1.31–2.27) |

| Other | 4.8 (4.1–5.7) | 1.63 (1.23–2.16) | 1.43 (1.08–1.91) |

| Residencec | |||

| Own residence | 4.0 (3.6–4.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Parent's residence | 8.7 (6.5–11.6) | 2.13 (1.57–2.90) | 1.28 (0.93–1.77) |

| Someone else's residence | 10.2 (8.2–12.6) | 2.43 (1.91–3.08) | 1.66 (1.29–2.13) |

| Unstable housing | 13.0 (9.9–17.0) | 2.95 (2.18–3.98) | 1.81 (1.32–2.46) |

| Educational attainmentd | |||

| <High school | 5.6 (4.9–6.5) | 1.18 (0.97–1.43) | — |

| ≥High school | 4.8 (4.3–5.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) | — |

| Employment statusc | |||

| Employed | 3.3 (2.8–3.9) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Unemployed | 6.1 (5.5–6.8) | 1.75 (1.44–2.13) | 1.42 (1.14–1.76) |

| Household incomec | |||

| ≤$18,000 | 6.0 (5.4–6.7) | 1.75 (1.43–2.14) | 1.20 (0.96–1.49) |

| >$18,000 | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Missing | 7.8 (5.4–11.2) | 2.28 (1.53–3.40) | 1.84 (1.07–3.17) |

| GBV history at baselineb,d | |||

| No | 3.7 (3.0–4.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 5.7 (5.1–6.3) | 1.51 (1.20–1.90) | 1.35 (1.07–1.71) |

| Recent drug usec | |||

| No | 3.9 (3.4–4.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 8.4 (7.3–9.7) | 2.07 (1.74–2.47) | 1.44 (1.19–1.75) |

| Recent transactional sexc | |||

| No | 4.7 (4.2–5.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 21.8 (16.7–28.3) | 4.28 (3.24–5.66) | 2.06 (1.52–2.80) |

| No. of recent sex partnersc | |||

| 0 | 3.8 (2.8–5.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) | — |

| 1 | 3.8 (3.4–4.3) | 1.08 (0.79–1.48) | — |

| 2–4 | 10.6 (8.9–12.5) | 2.81 (2.01–3.91) | — |

| >4 | 20.0 (14.4–27.6) | 5.11 (3.29–7.93) | — |

| Condom use with vaginal intercoursec | |||

| Always used condoms | 5.0 (4.4–5.8) | 1.52 (1.13–2.04) | — |

| Did not always use condoms | 5.8 (5.1–6.6) | 1.71 (1.27–2.29) | — |

| No vaginal intercourse | 3.4 (2.6–4.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) | — |

| Condom use with anal intercoursec | |||

| Always used condoms | 6.8 (4.3–10.8) | 1.33 (0.86–2.04) | — |

| Did not always use condoms | 6.2 (4.2–9.2) | 1.21 (0.81–1.79) | — |

| No anal intercourse | 5.1 (4.6–5.6) | 1.00 (Ref.) | — |

Sexually transmitted infection acquisition was defined as self-reported diagnosis by a health care provider of gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, or trichomoniasis since the participant's previous study visit (past 6 months).

N = 23,384 visit pairs contributed by 2826 participants. Model was additionally adjusted for study site (Bronx, Brooklyn, DC, San Francisco, Chicago, or Southern).

Physical violence, sexual violence, and/or intimate partner psychological violence.

Time-varying variables, measured with respect to the past 6 months.

Variables measured at baseline.

AIRR, adjusted incidence rate ratio; IRR, incidence rate ratio; WIHS, Women's Interagency HIV Study

In the adjusted model, recent GBV experience was associated with a 1.28-fold (95% CI 0.99–1.65) risk of STI acquisition (Table 3). HIV-seropositive status was associated with a 1.28-fold (95% CI 1.03–1.58) risk of STI acquisition. Other risk factors for STI acquisition in the adjusted model included unstable housing (adjusted incidence rate ratio [AIRR] 1.81, 95% CI 1.32–2.46), unemployment (AIRR 1.42, 95% CI 1.14–1.76), GBV history at baseline (AIRR 1.35, 95% CI 1.07–1.71), recent drug use (AIRR 1.44, 95% CI 1.19–1.75), and recent transactional sex (AIRR 2.06, 95% CI 1.52–2.80).

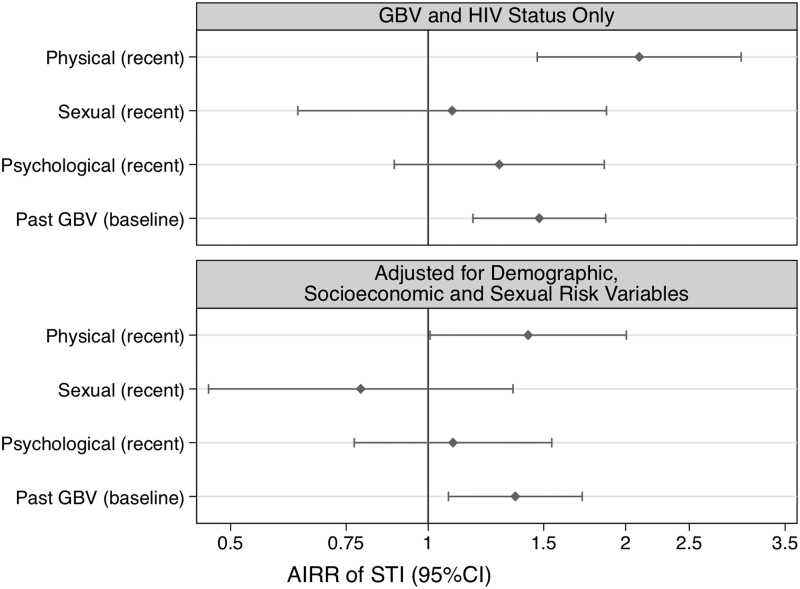

When we included recent physical violence, recent sexual violence, recent psychological violence, and GBV history at baseline as separate independent variables in a mutually adjusted model (Fig. 3), recent physical violence (AIRR 1.42, 95% CI 1.01–2.00) and GBV history at baseline (AIRR 1.36, 95% CI 1.07–1.72) were associated with an increased risk of STI acquisition. Recent sexual violence and recent intimate partner psychological violence were not associated with risk of STI acquisition in the mutually adjusted model.

FIG. 3.

Associations of forms of GBV with STI acquisition. Results are from a model adjusted for all forms of GBV included as separate variables. Physical violence, sexual violence, and intimate partner psychological violence were measured in reference to the past 6 months, whereas past GBV refers to lifetime experience of GBV before WIHS entry (measured at baseline). STI was defined as self-reported diagnosis by a health care provider of gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, or trichomoniasis since the participant's previous study visit (past 6 months). The model was additionally adjusted for HIV status, age, study site, year of WIHS enrollment, race/ethnicity, marital status, residence, employment, household income, recent drug use, and recent transactional sex. N = 23,376 visit pairs contributed by 2824 participants. STI, sexually transmitted infection.

In the interaction model for recent GBV and HIV status, there was no evidence of interaction (pinteraction = 0.42). However, different results by HIV status were observed when forms of GBV were included as separate variables. Among HIV-seronegative women, recent physical violence was strongly associated with increased risk of STI acquisition (AIRR 2.27, 95% CI 1.18–4.35) (Table 4). In contrast, among HIV-seropositive women, recent intimate partner psychological violence (AIRR 1.37, 95% CI 0.94–2.00) and GBV history at baseline (AIRR 1.59, 95% CI 1.20–2.10) were associated with increased risk of STI acquisition. The associations of intimate partner psychological violence and GBV history at baseline with increased risk of STI acquisition differed significantly by HIV status (pinteraction < 0.05).

Table 4.

Associations of Forms of Gender-Based Violence with Sexually Transmitted Infection Acquisition by HIV Status

| GBV exposures | HIV-seronegative |

HIV-seropositive |

pinteraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIRR (95% CI) | AIRR (95% CI) | ||

| Physical violence (recent) | 2.27 (1.18–4.35) | 1.25 (0.84–1.87) | 0.13 |

| Sexual violence (recent) | 0.71 (0.21–2.43) | 0.80 (0.44–1.45) | 0.86 |

| Intimate partner psychological violence (recent) | 0.50 (0.23–1.11) | 1.37 (0.94–2.00) | 0.03 |

| GBV history at baseline | 0.91 (0.60–1.38) | 1.59 (1.20–2.10) | 0.03 |

Results are from a model adjusted for all GBV exposures included as separate variables, with interaction terms for HIV status. Physical violence, sexual violence, and intimate partner psychological violence were measured in reference to the past 6 months, whereas GBV history at baseline was measured at study entry. STI was defined as self-reported diagnosis by a health care provider of gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, or trichomoniasis since the participant's previous study visit (past 6 months). The model was adjusted for age, study site, year of WIHS enrollment, race/ethnicity, marital status, residence, employment, household income, recent transactional sex, and recent drug use, as well as the main effects of forms of GBV and HIV status. N = 23,376 visit pairs contributed by 2824 participants.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study representative of U.S. WLHIV, recent GBV experience was associated with an increased risk of STI acquisition. The overall association of recent GBV experience with the risk of STI acquisition did not differ by HIV status. However, we observed significant interactions by HIV status when assessing the independent associations of different forms of GBV with the risk of STI acquisition. Recent physical violence was strongly associated with STI acquisition among HIV-seronegative women, whereas the experience of GBV before study entry and recent intimate partner psychological violence (i.e., controlling behaviors) were associated with a higher risk of STI acquisition among WLHIV. Thus, pathways linking violence and STI among women may vary by HIV status.

Higher risk of STI acquisition was consistently observed among WLHIV. This finding may be due to immune suppression42; alternatively, unmeasured social or behavioral risk factors may vary by HIV status. We observed rates of STI acquisition of 5.5 per 100 person-years among sexually active WLHIV and 4.3 per 100 person-years among sexually active HIV-seronegative women. The IRs of individual STI were low, ranging from 0.4 per 100 person-years for gonorrhea and syphilis to 3.2 per 100 person-years for trichomoniasis.

Other studies have observed low rates of STI among women engaged in HIV care. In a demographically similar cohort of WLHIV, Dionne-Odom et al. observed low prevalence of chlamydia (1.0%), syphilis (1.6%), and gonorrhea (0.5%), but higher prevalence of trichomoniasis (13.3%).43 The authors concluded that universal STI screening among WLHIV in the United States may not be warranted, as many women had few STI risk behaviors, and that improved understanding of predictors of STI risk among WLHIV is needed.43 Lucar et al. observed an IR of 1.1 per 100 person-years for a composite outcome of chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis infection among WLHIV in Washington, DC, 2011–2015, with low STI incidence observed among cisgender women aged 35–54.44 Similarly, Raifman et al. observed an average test positivity for gonorrhea and chlamydia of 1.6% among sexually active women in the HIV Research Network, 2004–2014.45 These studies did not assess the contribution of GBV experience to STI risk.

A few studies have compared forms of GBV with respect to STI risk.3,8,41,46 Early WIHS research among WLHIV identified a 2.8-fold higher odds of incident self-reported STI associated with recent physical violence, but not recent sexual violence.41 This association was mediated by the number of recent sex partners.41 In a study of 2180 married women in Goa, India, Weiss et al. observed that experience of sexual violence, but not physical or verbal abuse, was associated with a significant threefold higher odds of incident laboratory-diagnosed STI.3 In contrast, Allsworth et al. observed that past-year experience of physical violence without sexual violence was the strongest GBV risk factor for incident laboratory-diagnosed STI, associated with a 1.8-fold increased risk, in a study of 542 sexually active girls and women in Rhode Island.47 In the Togo 2013–2014 Demographic and Health Survey, Nguyen et al. observed a significant threefold higher odds of self-reported past-year STI among women reporting physical IPV, sexual IPV, or both, compared with no IPV.46

We found that recent physical violence had the strongest independent association with the risk of STI acquisition, particularly among HIV-seronegative women. Exposure to physical violence may reflect social vulnerability and reduced ability to negotiate safer sex. We adjusted for variables including residence, employment, and income; however, residual confounding is possible. Physical violence may also be a risk marker for partner- or network-level characteristics. Alternatively, previous WIHS research limited to WLHIV suggested that women who were physically abused exited violent relationships and sought out new partners, thus encountering elevated short-term risk of STI acquisition.41

We observed that GBV history at baseline was a strong independent predictor of STI acquisition, particularly among WLHIV. Lifetime experience of GBV, particularly childhood sexual abuse, is associated with subsequent experiences of GBV, substance use, and HIV/STI risk behaviors, due to trauma and other psychosocial consequences of abuse.12,13 Indeed, these pathways may play a stronger role in STI acquisition for WLHIV. We observed a stronger association of recent intimate partner psychological violence with STI acquisition among WLHIV. This finding may be due to interacting effects of HIV status and chronic psychosocial stress on immune biomarkers in the reproductive tract,20 although this line of research is in an early stage. Our findings support the relevance of a life course perspective on preventing, studying, and treating the effects of GBV, particularly among WLHIV.48

Contrary to expectation, we did not observe significant associations between recent sexual violence and incident STI acquisition. The interview question, “Has anyone pressured or forced you to have sexual contact?,” may not adequately capture women's experiences of coerced sex or unequal power dynamics that increase STI risk.35

Further, we did not observe an association between condom non-use and STI acquisition. Detailed data on condom use were not available; measures that account for frequency of unprotected sex and partner STI risk would likely be stronger predictors of incident STI. Likewise, we did not observe an interaction in the association between recent GBV experience and STI acquisition by HIV status. This may be because the null association of recent sexual violence with STI acquisition, which did not differ by HIV status, masked the significant interaction of recent intimate partner psychological violence with HIV status.

Adverse socioeconomic conditions increase vulnerability to GBV and HIV/STI acquisition. Recent research by Decker et al. in the WIHS found that low income and housing instability were associated with subsequent experience of GBV.14 Among low-income and unstably housed women, reliance on a partner for resources such as money or shelter is linked to condom non-use and vulnerability to violence due to unequal power dynamics.35 Indeed, qualitative research by Frew et al. identified financial instability as a major driver of high-risk sexual behaviors among women at risk of HIV infection.35 We found that unstable housing and unemployment were independently associated with 81% and 42% increased risk of STI acquisition, respectively, underscoring the relevance of women's socioeconomic conditions for sexual health.

Pathways linking substance use, GBV, and HIV/STI risk include reliance on a partner for drugs, transactional sex to procure drugs for oneself or a partner, reduced ability to avoid violence or negotiate condom use while under the influence, and the social vulnerability of drug-involved women.28 In this study, recent drug use and transactional sex were strongly associated with GBV experience and risk of STI acquisition. Previous work in the WIHS identified several measures of substance use as risk factors for physical violence, whereas transactional sex was more strongly associated with sexual violence.14 Our results support centering the physical and sexual safety needs of women who use drugs and women who trade sex.

Strengths of this study include generalizability, longitudinal design, and adjustment for several potential confounders. The WIHS is a well-described cohort, representative of cisgender WLHIV in several major U.S. cities.36–38 Limitations include use of a self-reported outcome, which is considered an acceptable method of data collection for STI but is likely subject to underreporting49 and requires health care utilization. Pathways from violence to STI likely vary based on relationship context, partner STI status, and presence of vaginal trauma during sexual abuse; we lacked data on these factors. In addition, our measures of GBV did not take severity or frequency into account. We adjusted for several potential confounders; however, some of these variables may instead mediate the association between GBV and STI, potentially resulting in overadjustment.50

We chose to focus on GBV exposures and STI outcomes at consecutive visits separated by 6 months; however, there are different etiologically relevant periods depending on the pathway from GBV experience to STI acquisition. Finally, the WIHS only includes individuals assigned female at birth but high rates of GBV and HIV/STI acquisition have been documented among transgender women.51 Future research and policy efforts to prevent GBV and HIV/STI should consider the unique needs of transgender women.

Conclusion

We identified recent GBV experience as an independent risk factor for STI acquisition. Our findings support recommendations for women's health clinicians to screen patients for IPV and provide appropriate resources and referrals,52 following a trauma-informed care framework.53 We observed that the experience of GBV before study entry and recent intimate partner psychological violence were associated with risk of STI acquisition among WLHIV. This finding may inform risk stratification for STI screening among WLHIV, although further study using clinical STI diagnosis is warranted. Unstable housing, unemployment, transactional sex, and drug use were also important STI risk factors. Our results support a holistic approach to improving women's socioeconomic stability to reduce vulnerability to GBV and its sexual health sequelae.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Homayoon Farzadegan and Dr. Tracey Wilson for their helpful comments. They also thank Ms. Lorie Benning for her role in data management. Data in this article were collected by the MACS/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. MWCCS (Principal Investigators): Atlanta clinical research site (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-HL146241-01; Baltimore clinical research site (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), U01-HL146201-01; Bronx clinical research site (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-HL146204-01; Brooklyn clinical research site (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-HL146202-01; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D'Souza, Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-HL146193-01; Chicago-Cook County clinical research site (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-HL146245-01; Chicago-Northwestern clinical research site (Steven Wolinsky), U01-HL146240-01; Connie Wofsy Women's HIV Study, Northern California clinical research site (Bradley Aouizerat and Phyllis Tien), U01-HL146242-01; Los Angeles clinical research site (Roger Detels and Otoniel Martinez-Maza), U01-HL146333-01; Metropolitan Washington clinical research site (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-HL146205-01; Miami clinical research site (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-HL146203-01; Pittsburgh clinical research site (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), U01-HL146208-01; University of Alabama Birmingham-University of Mississippi Medical Center clinical research site (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-HL146192-01; University of North Carolina clinical research site (Adaora Adimora), and U01-HL146194-01.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The MACS/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS) is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and National Cancer Institute (NCI). MWCCS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute), P30-AI-050409 (Atlanta Center for AIDS Research), P30-AI-050410 (University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research), P30-AI-027767 (University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for AIDS Research), and P30-AI-073961 (Miami Center for AIDS Research). S.K. was supported as a KL2 scholar by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (KL2-TR-001432). L.B.H.'s effort was supported by the National Institute of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD-K23-HD-078153). M.R.D.'s effort was supported by the NIDA (R03-DA-03569102).

References

- 1. Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M. A global overview of gender-based violence. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2002;78:S5–S14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. Lancet 2010;376:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss HA, Patel V, West B, Peeling RW, Kirkwood BR, Mabey D. Spousal sexual violence and poverty are risk factors for sexually transmitted infections in women: A longitudinal study of women in Goa, India. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson PJ, Hellerstedt WL. Current or past physical or sexual abuse as a risk marker for sexually transmitted disease in pregnant women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002;34:62–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rahman M, Nakamura K, Seino K, Kizuki M. Intimate partner violence and symptoms of sexually transmitted infections: Are the women from low socio-economic strata in Bangladesh at increased risk. Int J Behav Med 2014;21:348–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prakash R, Manthri S, Tayyaba S, et al. Effect of physical violence on sexually transmitted infections and treatment seeking behaviour among female sex workers in Thane district, Maharashtra, India. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, Nunez A, Ezeanolue EE, Ehiri JE. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:18845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007;8:149–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stockl H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2015;29:2183–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Groves AK, Reyes HLM, Moodley D, Maman S. HIV positive diagnosis during pregnancy increases risk of IPV postpartum among women with no history of IPV in their relationship. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1750–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andrade RF, Araújo MA, Vieira LJ, Reis CB, Miranda AE. Intimate partner violence after the diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases. Rev Saude Publica 2015;49:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen M, Deamant C, Barkan S, et al. Domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in HIV-infected women and women at risk for HIV. Am J Public Health 2000;90:560–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwartz RM, Weber KM, Schechter GE, et al. Psychosocial correlates of gender-based violence among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in three US cities. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:260–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Decker MR, Benning L, Weber KM, et al. Physical and sexual violence predictors: 20 Years of the Women's Interagency HIV Study cohort. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:731–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bogart LM, Collins RL, Cunningham W, et al. The association of partner abuse with risky sexual behaviors among women and men with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 2005;9:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson JC, Campbell JC, Glass NE, Decker MR, Perrin N, Farley J. Impact of intimate partner violence on clinic attendance, viral suppression and CD4 cell count of women living with HIV in an urban clinic setting. AIDS Care 2018;30:399–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O'Campo PJ. Intimate partner violence, HIV status, and sexual risk reduction. AIDS Behav 2002;6:107–116 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen MH, Cook JA, Grey D, et al. Medically eligible women who do not use HAART: The importance of abuse, drug use, and race. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1147–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weber KM, Cole SR, Burke-Miller J, et al. The effect of gender based violence (GBV) on mortality: A longitudinal study of US women with and at risk for HIV. Paper presented at International AIDS Conference, Washington, DC, July25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ghosh M, Daniels J, Pyra M, et al. Impact of chronic sexual abuse and depression on inflammation and wound healing in the female reproductive tract of HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected women. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghosh M, Rodriguez-Garcia M, Wira CR. Immunobiology of genital tract trauma: Endocrine regulation of HIV acquisition in women following sexual assault or genital tract mutilation. Am J Reprod Immunol 2013;69 Suppl 1:51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Decker MR, Seage GR, 3rd, Hemenway D, Gupta J, Raj A, Silverman JG. Intimate partner violence perpetration, standard and gendered STI/HIV risk behaviour, and STI/HIV diagnosis among a clinic-based sample of men. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raj A, Reed E, Welles SL, Santana MC, Silverman JG. Intimate partner violence perpetration, risky sexual behavior, and STI/HIV diagnosis among heterosexual African American men. Am J Mens Health 2008;2:291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Decker MR, Seage GR, 3rd, Hemenway D, et al. Intimate partner violence functions as both a risk marker and risk factor for women's HIV infection: Findings from Indian husband-wife dyads. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;51:593–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, et al. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS 2006;20:2107–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1873–1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seth P, Wingood GM, Robinson LS, Raiford JL, DiClemente RJ. Abuse impedes prevention: The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV/STI risk among younsg African American women. AIDS Behav 2015;19:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Chang M. Intimate partner violence and HIV among drug-involved women: Contexts linking these two epidemics—Challenges and implications for prevention and treatment. Subst Use Misuse 2011;46:295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loya RM. Rape as an economic crime: The impact of sexual violence on survivors' employment and economic well-being. J Interpers Violence 2015;30:2793–2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, Rahman S. Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: A review of the literature. Int J Family Med 2013;2013:313909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, Zonderman AB. Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:959–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. J Fam Violence 1999;14:99–132 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lang AJ, Rodgers CS, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Dresselhaus TR, Stein MB. Sexual trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and health behavior. Behav Med 2003;28:150–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seth P, Patel SN, Sales JM, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES. The impact of depressive symptomatology on risky sexual behavior and sexual communication among African American female adolescents. Psychol Health Med 2011;16:346–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frew PM, Parker K, Vo L, et al. Socioecological factors influencing women's HIV risk in the United States: Qualitative findings from the women's HIV SeroIncidence study (HPTN 064). BMC Public Health 2016;16:803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiology 1998;9:117–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study: An observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005;12:1013–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, et al. Cohort profile: The Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:393i–394i [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2). J Fam Issues 1996;17:283–316 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: An application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hogben M, Gange SJ, Watts DH, et al. The effect of sexual and physical violence on risky sexual behavior and STDs among a cohort of HIV seropositive women. AIDS Behav 2001;5:353–361 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Turner C. Prevalence of sexually transmitted co-infections in people living with HIV/AIDS: Systematic review with implications for using HIV treatments for prevention. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87:183–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dionne-Odom J, Westfall AO, Van Der Pol B, Fry K, Marrazzo J. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence in women with HIV: Is there a role for targeted screening? Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:762–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lucar J, Hart R, Rayeed N, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected individuals in the District of Columbia and estimated HIV transmission risk: Data from the DC Cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Raifman JR, Gebo KA, Mathews WC, et al. Gonorrhea and chlamydia case detection increased when testing increased in a multisite US HIV cohort, 2004–2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:409–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nguyen AH, Giuliano AR, Mbah AK, Sanchez-Anguiano A. HIV/sexually transmitted infections and intimate partner violence: Results from the Togo 2013–2014 Demographic and Health Survey. Int J STD AIDS 2017;28:1380–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Allsworth JE, Anand M, Redding CA, Peipert JF. Physical and sexual violence and incident sexually transmitted infections. J Womens Health 2009;18:529–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Williams LM. Understanding child abuse and violence against women. J Interpers Violence 2003;18:441–451 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Niccolai LM, Kershaw TS, Lewis JB, Cicchetti DV, Ethier KA, Ickovics JR. Data collection for sexually transmitted disease diagnoses: A comparison of self-report, medical record reviews, and state health department reports. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15:236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2009;20:488–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, et al. Gender abuse, depressive symptoms, and HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among male-to-female transgender persons: A three-year prospective study. Am J Public Health 2013;103:300–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 518: Intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119(Part 1):412–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Machtinger EL, Davis KB, Kimberg LS, et al. From treatment to healing: Inquiry and response to recent and past trauma in adult health care. Womens Health Issues 2019;29:97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]