Abstract

Introduction

In the last two decades, the introduction of tandem mass spectrometry in clinical laboratories has enabled simultaneous testing of numerous acylcarnitines and amino acids from dried blood spots for detecting many aminoacidopathies, organic acidurias and fatty acid oxidation disorders. The expanded newborn screening was introduced in Slovenia in September 2018. Seventeen metabolic diseases have been added to the pre-existing screening panel for congenital hypothyroidism and phenylketonuria, and the newborn screening program was substantially reorganized and upgraded.

Methods

Tandem mass spectrometry was used for the screening of dried blood spot samples. Next-generation sequencing was introduced for confirmatory testing. Existing heterogeneous hospital information systems were connected to the same laboratory information system to allow barcode identification of samples, creating reports, and providing information necessary for interpreting the results.

Results

In t he first y ear of t he expanded newborn screening a total of 15,064 samples w ere screened. Four patients were confirmed positive with additional testing.

Conclusions

An expanded newborn screening program was successfully implemented with the first patients diagnosed before severe clinical consequences.

Keywords: newborn screening, NBS, tandem mass spectrometry, MS/ MS, next-generation sequencing, NGS, inborn errors of metabolism, IEM

Izvleček

Uvod

Uporaba tandemske masne spektrometrije je v zadnjih dvajsetih letih močno vplivala na diagnostiko vrojenih bolezni presnove, saj omogoča sočasno merjenje številnih acilkarnitinov in aminokislin iz posušenega madeža krvi in s tem prepoznavo različnih aminoacidopatij, organskih acidurij in motenj v metabolizmu maščobnih kislin. Program razširjenega presejanja novorojencev je bil v Sloveniji uveden septembra 2018. Obstoječemu programu presejanja kongenitalne hipotiroze in fenilketonurije je bilo dodanih 17 novih bolezni presnove, ob tem so bile vpeljane določene organizacijske spremembe.

Metode

Analiza vzorca posušenega madeža krvi poteka s tandemsko masno spektrometrijo. Za potrditveno testiranje je bila vpeljana metoda sekvenciranja naslednje generacije. Obstoječi heterogeni bolnišnični informacijski sistemi so bili povezani v enotni laboratorijski informacijski sistem, kar omogoča kodno identifikacijo vzorca, oblikovanje izvidov in dostop do vseh podatkov, potrebnih za interpretacijo izvida.

Rezultati

V prvem letu razširjenega presejanja novorojencev je bilo pregledanih 15.064 vzorcev. Z dodatnimi potrditvenimi testi je bila bolezen potrjena pri štirih bolnikih.

Zaključki

Razširjeno presejanje novorojencev je bilo uspešno vzpostavljeno. Prvi bolniki so bili prepoznani, diagnoza jim je bila postavljena pred pojavom kliničnih znakov.

Ključne besede: presejanje novorojencev, tandemska masna spektrometrija, sekvenciranje nove generacije, vrojene bolezni presnove, IEM, NBS, MS/MS, NGS

1. Introduction

A newborn screening (NBS) program is essential for the detection of inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) and other such disorders in infants. IEMs are inherited metabolic disorders in which genetic variants cause inactivity or lack of enzymes that are important in various chemical reactions in the body (1). The incidence of most IEMs is less than 1/10,000, which makes them rare (2). Nevertheless, early detection is crucial for the patient’s clinical outcome. Patients with late diagnosis present with severe consequences, ranging from minor disabilities to lethal outcomes (3). Therefore, it is crucial to start the treatment (which often involves a specialized dietary intervention) as soon as possible to prevent unfavourable outcomes (4). In addition, genetic testing and counselling are offered to parents (3).

Expanded NBS is possible with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), a method used for simultaneous testing of many different metabolites, including numerous acylcarnitines and amino acids on dried blood spots (DBS), which enable detection of many aminoacidopathies, organic acidurias and fatty acid oxidation disorders. Moreover, it is time-and cost-effective, with good sensitivity and specificity (5, 6, 7, 8, 9). There is also a lot of interest in implementing next-generation sequencing (NGS) into NBS programs, as it has been proven to be a valuable tool in confirming diseases, raising the possibility of family counselling, and influencing therapeutic decisions (10).

We aimed to describe the extended NBS program in Slovenia and to present the results of the first year of the program (11).

1.1. National Population-Based Newborn Screening Program in Slovenia

1.1.1. History of the Newborn Screening Program in Slovenia

The NBS program was first introduced in Slovenia in 1979 with screening for phenylketonuria (PKU) (12). Two years later, screening for congenital hypothyroidism (CH) was added (13). From 1993 to 2012, 358,831 newborns were screened for PKU, and 57 were diagnosed with the disease. A total of 427,396 newborns were screened for CH between the years 1991 and 2012,and the disease was confirmed in 184 cases (14). The incidence of PKU in the stated period was, therefore, 1:6769 for PKU and 1:2323 for CH, which meets the estimated incidence of those diseases in Europe (1:3000 – 1:30,000 for PKU and 1:1300 – 1:13,000 for CH) (14, 15).

In 2000, selective screening for IEMs was initiated, starting with analyses of amino acids and organic acids in symptomatic patients with suspected IEMs or patients with a positive family history for IEMs. Different chromatographic methods were used for the detection of metabolites, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for organic acid determination and ion exchange chromatography-post-column derivatization or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for amino acid measurement. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was also used for acylcarnitine analysis. As of April 2014, a total of 168 patients with organic acid disorders and amino acid disorders (of them 140 with PKU diagnosed on NBS) and five with fatty acid oxidation disorders were in the Slovenian Register of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (16). Comparing these results with the data from those countries with expanded NBS screening programs showed that we should expect more identified cases (16). Therefore, a pilot study to estimate the incidences of IEMs and support the expansion of the NBS program in Slovenia was performed in 2014–2016 (10, 11).

1.1.2. Pilot Study of the Expanded Newborn Screening Program in Slovenia

To prepare an optimal strategy for the organization of the expanded NBS for IEMs in Slovenia, a pilot study was performed analysing 10,048 Slovenian newborns (10). In the initial stage, each IEM that was included in the study was identified by acylcarnitine and amino acid analysis with the MS/MS method for screening and confirmed with confirmatory testing. NGS was included for confirmatory testing in combination with other established tests for IEM detection, such as organic acid determination, amino acid analysis and enzyme activity testing. NGS allows the simultaneous analysis of all genes associated with IEMs included in the screening, and thus represents the method of choice for the confirmation of the diseases identified in the NBS. Out of 10,048 results, 113 follow-ups (newborns with the ten highest concentrations of metabolites included in the pilot study) were evaluated at an outpatient clinic, where additional confirmatory analyses were performed. With confirmatory tests, four new patients with IEMs were detected, namely a patient with glutaric aciduria type 1, a patient with very long-chain-acyl-CoA-dehydrogenase deficiency, and two patients with 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA-carboxylase deficiency. In all cases, the NGS approach identified causative genetic variants, such as those that have not yet been described in the literature (10, 11). Based on our results and comparisons with other European countries, the cut-off values and ratios of individual metabolites were determined.

2. Methods

2.1. Expanded Newborn Screening in Slovenia

2.1.1. Protocol of Expanded Newborn Screening in Slovenia

The process begins with informing parents about the goals and the course of the NBS program. Parents are informed about the NBS procedure and its advantages by a neonatologist at the first medical examination of the newborn. At the same time, an online information leaflet is available (18). The collection of the samples and input of patient data into an electronic medical record (EMR) are performed next, with the generation of a barcode and QR code, followed by the transport of samples to the laboratory, where they are automatically processed, tested, analysed, and confirmed. In cases of a positive screening result, the family is informed by one of the paediatricians subspecialized in paediatric endocrinology and inborn errors of metabolism at the University Medical Centre (UMC) – University Children’s Hospital Ljubljana (UCHL), who also provide family counselling, treatment and further management (9, 17).

Written informed permission is not required to perform the NBS in Slovenia, because the program is a mandatory nationwide population program, which is required by national legislation. If the parents refuse to take part in the program, the neonatologist performs additional counselling before the discharge of the newborn from the hospital. A written refusal statement must be signed on a blank sample card, and the child’s paediatrician is informed. A blank card with maternal data is sent to the laboratory and archived (9).

A custom DBS card with space for barcode and QR code with the information of the newborn and the mother is used for blood sampling. Blood samples are taken 48 to 72 hours after birth from the newborn’s heel or by venepuncture, according to the technical requirements (9).

Sample information and newborn identification data are entered into the hospital EMR, and an order for the NBS testing is created. The sample must be sent from the nursery within 24 hours by mail or courier service to the Department of Nuclear Medicine (DNM), UMC Ljubljana, where all the samples are accepted. Half of the sample card is used at DNM, where the fluorometric method is used for PKU screening and dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluorescence immunoassay is used for CH screening, as described earlier (14). The other half is sent to the Clinical Institute for Special Laboratory Diagnostics, UMC – University Children’s Hospital Ljubljana (CISLD), where the expanded NBS is performed. In the DNM and CISLD laboratory, sample barcodes are scanned, and the orders made by the hospitals are accepted and automatically transferred into the laboratory information system. Inadequate samples are declined, the nursery is informed, and a new sample is requested (9)

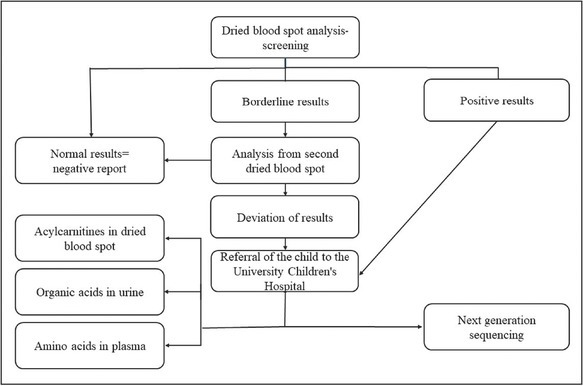

The algorithm for reporting and confirming results of the expanded NBS has been prepared, depending on the level of disease suspicion, mainly based on the degree of metabolite elevation and profiles of their combinations (Fig 1). The nursery is informed about the results of the screening automatically through the information system as soon as the laboratory specialist or/and clinician confirms the results. In the case of borderline or positive results, a new additional sample must be tested. For newborns with borderline results the nursery collects a second sample on the screening card and sample goes through the same initial screening procedure again. When the second testing is indicative of a disease, a newborn is referred to the UCHL for further diagnostics. Newborns with a positive result on initial screening are referred directly to the UCHL. Depending on the disease in question, a sample of urine, plasma or blood may also be requested. All positive results are tested using NGS and/or other confirmatory methods. Additionally, enzymatic activity is determined when indicated (performed at the Amsterdam Medical Center laboratory). The newly detected patients are treated and followed up at the UCHL (9).

Figure 1.

Screening algorithm for expanded NBS results.

Confirmatory testing for borderline and positive CH results is done at DNM, while PKU borderline results are retested at DNM, final confirmation of positive result is done at CISLD (14).

Samples are stored in the laboratory for an indefinite period and can be reused for the selective diagnostics if permitted by official state regulations. Quality indicators for the NBS program are evaluated once per year (9). CISLD is participating in different external quality control schemes, the Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Program (NSQAP) at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.cdc.gov/labstandards/nsqap.html) and European Research Network for evaluation and improvement of screening, Diagnosis and treatment of Inherited disorders of Metabolism (ERNDIM) (https://www.erndimqa.nl/)

When the diagnosis is confirmed, the patient is included in the Slovenian Register of Rare Diseases, and the registration needs to be initiated by the physician who confirmed the diagnosis (9).

A MS/MS (Waters Xevo TQD LC-MS/MS) is used for expanded screening (9). It quantifies the tested metabolites with stable-isotope-labelled internal standards, and allows the detection of many metabolites simultaneously in a single run (19). It can accommodate a high throughput of samples (2–3 min per sample) and has low reagent cost at the same time as being sensitive and specific (20).

For NGS confirmatory testing, an in-house panel of 72 genes has been developed by the newborn screening team, which includes a geneticist (Table 1). The NGS panel includes causative genes for the 18 diseases included in the NBS program (Table 2), with the addition of genes for the conditions that present with the increase of the same metabolites as the targeted disease and are therefore invaluable for differential diagnostics. Variants detected with NGS are confirmed by Sanger sequencing and reported to the NBS clinical team, which includes paediatricians subspecialized in the paediatric endocrinology and inborn errors of metabolism.

Table 1.

Panel of 72 genes for the NGS confirmatory testing in expanded NBS program.

| ABCD1 | ABCD4 | ACAD8 | ACAD9 | ACADL | ACADM | ACADS | ACADVL |

| ACAT1 | ADA | ALDH18A1 | ARG1 | ASL | ASS | AUH | BCAT2 |

| BCKDHA | BCKDHB | BTD | CD320 | CPS1 | CPT1A | CPT2 | DBT |

| DLD | ETFA | ETFB | ETFDH | ETHE1 | FAH | GCDH | GCH1 |

| GLUL | HADH | HADHA | HADHB | HLCS | HMGCL | HMGCS2 | HPD |

| HSD17B10 | IVD | LMBRD1 | MCCC1 | MCCC2 | MLYCD | MMAA | MMAB |

| MMACHC | MMADHC | MTR | MTRR | MMUT | NAGS | OTC | PAH |

Table 2.

List of diseases included in expanded NBS program. * – already running newborn screening program for phenylketonuria; in agreement, the program is running in parallel for two years on both systems, and the reported results are from the existing program for PKU screening.

| Tyrosinemia type 1 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase deficiency type 2 |

| Maple syrup urine disease | 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency |

| Isovaleric acidemia | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric aciduria |

| Glutaric aciduria type 1 | Holocarboxylase synthethase deficiency |

| Glutaric aciduria type 2 | β-ketothiolase deficiency |

| Propionic aciduria | Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| Methylmalonic aciduria | Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| Carnitine uptake deficiency | Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency |

| Carnitine palmitoyltransferase deficiency type 1 | Phenylketonuria* |

If one of the diseases not included in expanded screening is detected, the full NBS team (which includes both laboratory and clinical NBS teams) could make a case-by-case decision to proceed with diagnostics and reporting if that would be in the presumed clinical benefit of the newborn (21).

During the first year of the expanded NBS program, all 14 nurseries were gradually connected in the same laboratory information system.

3. Results

3.1. First Year of Experience

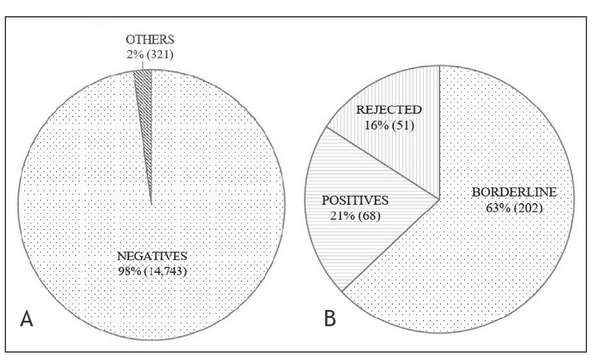

Altogether, 15,064 samples were screened: 14,743 were reported with negative results, 202 with borderline findings, and 68 with positive results, while 51 samples were rejected (Figure 2). Among the positive results, four patients were confirmed with additional diagnostic testing (Table 3). Additional diagnostic testing was done with the measurement of organic acids in urine, amino acids in plasma, enzyme activity determination, and genetic analysis, depending on screening results.

Figure 2.

A – all samples (15,064); percentage of negative results compared to others (positive and borderline positive results and rejected samples). B – others – positive and borderline positive results and rejected samples (321); percentage among others (positive and borderline positive results and rejected samples).

Table 3.

Values of acylcarnitines and amino acids at newborn screening and follow-up for confirmed patients. CoA – coenzyme A, DBS – dried blood spot, NBS – newborn screening, ref. – reference.

| Module name | NBS results (from DBS) μmol/L | Follow-up (from DBS) μmol/L | Confirmation tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | C14:1: 3.41 (˂0.32) C14: 1.41 (˂0.42) C14:2: 0.44 (0–0.05) C14:1/C2: 0.200 (˂0.014) C14:1/C16: 0.84 (˂0.08) | C14:1: 0.84 (˂0.32) C14: 0.41 (˂0.42)C14:2: 0.18 (˂0.05) C14:1/C2: 0.090 (˂0.014) C14:1/C16: 0.31 (˂0.08) | One known heterozygous pathogenic variant and one likely pathogenic variant |

| Isovaleric acidemia | C5: 2.47 (˂0.28) C5/C0: 0.132 (˂0.018) C5/C2: 0.164 (˂0.017) C5/C3: 1.91 (˂0.21) | C5: 5.77 (˂0.28) C5/C0: 0.222 (˂0.018) C5/C2: 0.499 (˂0.017) C5/C3: 5.84 (˂0.21) | Elevated isovalerylglycine in urine Reduced enzyme activity: 0.1 nmol/(min mg prot) (ref. value: 0.94–1.94) |

| Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | C8: 0.27 (˂0.16) C6: 0.27 (˂0.12) C10: 0.11 (˂0.26) C10:1: 0.13 (˂0.09) C8/C10: 2.45 (˂1.50) C8/C2: 0.07 (0.01) | C8: 0.96 (˂0.27) C6: 0.477 (˂0.15) C10: 0.14 (˂0.32) C10:1: 0.285 (˂0.25) C8/C10: 6.8 (˂2.3) C8/C2: 0.07 (0.02) | One known heterozygous pathogenic variant and one variant of unknown significance Reduced enzyme activity: 0.20 nmol/(min mg prot) (ref. value: 0.43–1.63) |

| Hyperprolinemia | Proline: 623 (˂261) | Proline: 794 (˂441) | Two pathogenic variants. Elevated proline in plasma: 748 (110–417) μmol/L |

Positive predictive value was 5.8% (confirmed positives/ all positives).

The percentage of altered profiles that lead to borderline and false positive samples is distributed among all three groups of screened diseases as follows: 43.3% in the group of fatty acid oxidation disorders; 32.6% in the group of organic acid disorders; 17.4% in the group of amino acid disorders; and 6.8% results with profile of multiple elevated metabolites, that does not fit only one group.

4. Discussion

The NBS was first introduced in 1963 in the USA with the Guthrie test for detecting PKU (22). Most developed countries already have an NBS program and screen for more diseases (9, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39). On the other hand, most of the countries worldwide do not have an expanded NBS (40, 41). In contrast with many other European countries, the Slovenian NBS until recently consisted only of testing for PKU and CH, which had put us in the same group as other countries in southeastern Europe (14, 40). Slovenia now has a spectrum of screened diseases comparable to those in most developed countries, with a total of 19 screened conditions (11, 20).

A study that assessed the NBS characteristics in 11 countries from southeastern Europe in 2014 showed that in most of only screening for PKU and CH were implemented, while four of the countries did not screen for PKU, and three of them did not screen for CH. A lack of financial resources was the main reason given for not introducing the expanded NBS, although the costs of the screening test per newborn varied from 1–12 euros in different EU countries, an average being 4 euros. In Slovenia the price of a screening test was calculated at 9.24 euros. The cost of confirmatory testing depends on tests needed for a certain condition. Other reasons given for not introducing the expanded NBS were the lack of staff and expertise. At that time, none of the countries from the region used MS/ MS for the NBS. Slovenia was one of the three countries (together with Romania and Croatia) that reported plans to implement tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in its NBS due to the expected expansion of screened diseases (40). In Croatia, the expanded NBS program was implemented in 2018 (42).

In the last few years, NBS with tandem mass spectrometry has become more available due to technological advances and has been proved to operate to a high standard. Therefore, it is already implemented in the NBS programs of many European countries as well as in the USA. MS/ MS allows simultaneous screening for more IEMs from one dried blood spot on a filter test paper. It detects inborn errors of amino acid metabolism and urea cycle defects, most fatty acid oxidation disorders, and numerous organic acidurias (7). Due to high throughput, it is possible to test great numbers of samples in a timely fashion, which supports screening samples of dried blood spots from the whole population. Moreover, the reagent costs are low, the method has high sensitivity (90–100%) and is highly specific (99–100%) (6, 7, 20, 43, 44, 45).

In Slovenia, confirmational tests are performed using NGS, detecting gene sequences responsible for IEMs (9). In the future, it would be possible to use it for screening for a larger spectrum of genetic diseases and further expanding the NBS program panel. NGS can be used for parental and sibling testing, genetic counselling, and family planning (10, 46, 47, 48). The NGS result is unaffected by environmental factors, such as dietary intake and treatment, stress, which all influence metabolites levels, and could thus affect the first tier NBS results (49). The first pilot NBS programs are now reported to use genetic testing as a first-line diagnostics, and are expected to gradually become fully clinically implemented (50).

The newly screened diseases meet the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for population-based screening (20, 51). Laboratory participates in external quality assurance schemes, organized by CDC and ERNDIM. The CDC scheme is organized as a quantitative analysis from DBS for newborn screening acylcarnitines and amino acids, and the interpretation of results is based on cut-offs. The ERNDIM scheme covers both quantitative analysis from DBS for selected metabolites and qualitative acylcarnitine measurement from DBS, where interpretation of the results is needed. The incidence of a specific IEM is essential when deciding on the inclusion of the disease in an NBS program. A pilot study was done to estimate the incidences for the Slovenian population, and the results of the study were also used for cut-off determination. CH will be tested as before, with testing of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) values (9). All hospital information systems were connected to the same laboratory information system for more efficient and safer sample identification and data control. Approximately 20,000 newborns from Slovenia are screened per year. The cumulative incidence of the IEMs in Slovenia was established at 1:2762, including PKU with incidence 1:6769 (10).

The strength of this study is that we introduced NGS as a conformational test, which helps to get the final diagnosis as soon as possible. It is also important to get more information and knowledge if genetic testing will be used in the future for NBS. During the first year we were still optimizing our NGS procedure, DNA isolation, and protocols. With this information we could improve screening and conformational tests. The major downside of NGS for use for NBS is the turnaround time. One limitation of this study is the gradual inclusion of maternity wards during the first year of introduction of the expanded NBS program, so the total nationwide population of newborns was not included. In addition, due to the novelty of the program some planned features (such as reporting the parent refusals) were not yet implemented.

The first year of experience with the expanded NBS program gives us important feedback information and provides us with initial experiences that inform us about possible future improvements of the program. One goal is regularly informing and educating nurseries about importance of sample quality, to reduce rejected samples. Cut-off values will be re-evaluated according to external control samples, and modified if necessary to reduce false positives. Second tier testing is planned for detection of propionic/methylmalonic acidemia, as it is known that the primary metabolite gives high number of false positive results. Isolation of DNA from DBS is another possibility, to reduce the need for additional sampling of blood.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the expanded NBS program with NGS as a confirmatory method was successfully implemented in Slovenia, and the first patients were appropriately detected through the program. Soon, we expect to expand the program further to also include relevant disorders which are not diagnosed with MS/MS. In the longer term, we expect that genomic testing will be gradually implemented as a first-line NBS test.

Funding Statement

The study was partly founded by the Slovenian Research Agency project V3-1505 and program P3-0343 and University Medical Centre Ljubljana’s research project 20150138.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Ethical approval

The nationwide project to expand the NBS program in Slovenia with the tandem mass spectrometry and with confirmatory genetic testing was approved by the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (#56/01/14). In 2018, the formal legislative framework was adopted as a basis of expanded NBS program in Slovenia, also requiring a yearly performance and quality analyses.

References

- 1.Lanpher B, Brunetti-Pierri N, Lee B. Inborn errors of metabolism: the flux from Mendelian to complex diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(6):449–59. doi: 10.1038/nrg1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcken B, Wiley V, Hammond J, Carpenter K. Screening newborns for inborn errors of metabolism by tandem mass spectrometry. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(23):2304–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell RR, Terry S, Tait VF, Olney R, Hinton CF, Grosse S. CDC grand rounds: newborn screening and improved outcomes. MMWR. 2012;61(21):390–3. et al. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harms E, Olgemöller B. Neonatal screening for metabolic and endocrine disorders. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(1-2):11–21. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Šmon A, Lampret Repič B, Žerjav Tanšek M. XXXVI. Derčevi dnevi. Ljubljana: Katedra za pediatrijo, Medicinska fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani; 2018. 2018. Razširjeno presejanje novorojencev v Sloveniji. et al. Jun 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chace DH. Mass spectrometry in newborn and metabolic screening: historical perspective and future directions. J Mass Spectrom. 2009;44(2):163–70. doi: 10.1002/jms.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chace DH, Kalas TA, Naylor EW. Use of tandem mass spectrometry for multianalyte screening of dried blood specimens from newborns. Clin Chem. 2003;49(11):1797–817. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Šmon A. Opredelitev kriterijev za razširjeno presejanje novorojencev za vrojene bolezni presnove: doctoral thesis. Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navodilo za izvajanje razširjenega presejanja novorojencev v Sloveniji. Pediatrična klinika, Univerzitetni klinični center Ljubljana. 2020. https://www.redkebolezni.si/ustanova/laboratoriji/ljubljana/sluzba-za-specialno-laboratorijsko-diagnostiko/ Accessed April 3rd.

- 10.Šmon A, Repič Lampret B, Grošelj U. Next generation sequencing as a follow-up test in an expanded newborn screening program. Clin Biochem. 2018;52:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.10.016. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grošelj U, Šmon A, Žerjav Tanšek M. 6th Slovenian Congress of Endocrinology. Bled: ZES; 2018. Expanded newborn screening (NBS) program in Slovenia. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battelino T, Kržišnik C, Pavlin K. Early detection and follow-up of children with phenylketonuria in Slovenia. Zdrav Vestn. 1994;63(Suppl 1):25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kržišnik C, Battelino T, Bratanič N. Results of screening for congenital hypothyroidism during the ten-year period (1981–1991) in Slovenia. Zdrav Vestn. 1994;63(Suppl 1):29–31. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Šmon A, Grošelj U, Žerjav Tanšek M. Newborn screening in Slovenia. Zdr Varst. 2015;54(2):86–90. doi: 10.1515/sjph-2015-0013. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loeber JG. Neonatal screening in Europe: the situation in 2004. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:430–8. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Repič Lampret B, Murko S, Žerjav Tanšek M. Selective screening for metabolic disorders in the Slovenian pediatric population. J Med Biochem. 2015;34:58–63. doi: 10.2478/jomb-2014-0056. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding C, LaFranchi SL, Thomas G. The northwest regional newborn screening program; Oregon practicioner’s manual. 9th ed. Oregon: Oregon Health and Science University; 2010. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obvestilo za starše in skrbnike. Nacionalni program presejanja novorojencev za izbrane prirojene bolezni. 2020. https://www.redkebolezni.si/assets1191/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Redke-bolezni_Obvestilo-za-starse-o-presejalnihtestih-novorojencev.pdf?x85004 Accessed April 3rd.

- 19.Repič Lampret B, Šmon A, Čuk V. XXXVI. Derčevi dnevi. Ljubljana: Katedra za pediatrijo, Medicinska fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani; 2018. 2018. Laboratorijska diagnostika vrojenih bolezni presnove. Jun 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rousseau F, Giguere Y, Berthier MT. Prasain JK. Tandem mass spectrometry – applications and principles. London: IntechOpen; 2012. Newborn screening by tandem mass spectrometry: impacts, implications and perspectives; pp. 751–76. et al. –. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pravilnik o spremembi Pravilnika za izvajanje preventivnega zdravstvenega varstva na primarni ravni. Uradni list RS. 47/2018.

- 22.MacReady RA, Hussey MG. Newborn phenylketonuria detection program in Massachussets. Am J Public Heal Nations Heal. 1964;54(12):2075¬–81. doi: 10.2105/ajph.54.12.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgard P, Cornel M, Filippo F. Report on the practices of newborn screening for rare disorders implemented in member states of the European Union, candidate, potential candidate and EFTA countries. Accessed April 11th. 2019. http://old.iss.it/binary/cnmr/cont/Report_NBS_Current_Practices_20120108_FINAL.pdf et al.

- 24.Padilla CD, Therell BL. Newborn screening in the Asia Pacific region. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(4):490–506. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therell BL, Adams J. Newborn screening in North America. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(4):447–65. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0690-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osterreichisches Neugeborenen-Screening. Eine Einrichtung an der Universtitatsklinik für Kinder- und Jugendheilkunde zur Früherfassung von angeborenen Erkrankungen. Medizinische Universität Wien. 2019. https://www.meduniwien.ac.at/hp/fileadmin/neugeborenenscreening/pdf/Folder_Neugeborenen_Screening_06.2018.pdf Accessed April 11th.

- 27.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neugeborenenscreening e. V. Zielerkrankungen im Neugeborenenscreening. 2019. http://www.screening-dgns.de/krankheiten.php Accessed April 11th.

- 28.Neugeborenen Screening Schweiz. Kinderspital Zurich. 2018. http://www.neoscreening.ch/display.cfm/id/100552/disp_type/dmssimple/pageID/79190 Accessed April 11th, 2019 at.

- 29.Program national de depistage neonatal. Ministere des Solidarites et de la Sante. 2019. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/prises-en-charge-specialisees/maladies-rares/DNN Accessed April 11th.

- 30.Depistage neonatal des maladies metaboliques et endocriniennes. Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc Bruxelles. 2019. https://www.saintluc.be/laboratoires/activites/biologie-clinique/biochimie/depistage-neonatal.php Accessed April 11th.

- 31.Ohlsson A. Neonatal screening in Sweden and disease-causing variants in phenylketonuria, galatosemia and biotinidase deficiency. Karolinska Instituet, Stockholm. 2016. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/08c9/51078a0bf299a3d689599ed6ac25c1a0ee20.pdf Accessed April 11th, 2019 at.

- 32.Statens Serum Institut. Screening for medfødte sygdomme. 2019. https://www.ssi.dk/sygdomme-beredskab-ogforskning/screening-for-medfodte-sygdomme Accessed April 11th.

- 33.Health Service Executive. A practical guide to newborn bloodspot screening in Ireland. 7th edition. Dublin: 2018. https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/child/newbornscreening/newbornbloodspotscreening/information-for-professionals/a-practical-guide-to-newborn-bloodspot-screening-in-ireland.pdf Accessed April 11th, 2019 at. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Public health England. Screening tests for you and your baby. 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/696849/Screening_tests_for_you_and_your_baby.pdf Accessed April 11th, 2019 at.

- 35.The Newborn Metabolic Screening Program. Your newborn baby’s blood test. New Zealand Government. 2017. https://www.nsu.govt.nz/system/files/resources/your-newborn-babys-blood-text-oct17.pdf Accessed April 11th, 2019 at.

- 36.The Sydney children’s hospital network. NSW Newborn Screening. 2019. https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/find-a-service/laboratory-services/nsw-newborn-screening/disorders Accessed April 11th.

- 37.Newborn screening in Canada status report. Canadian PKU and Allied Disorders Inc. 2015. https://www.raredisorders.ca/content/uploads/Canada-NBS-status-updated-Sept.-3-2015.pdf Accessed April 11th, 2019 at.

- 38.Newborn screening for your baby’s health. New York State Department of Health. 2019. https://www.wadsworth.org/sites/default/files/WebDoc/1666822457/FYBH_English.pdf Accessed April 11th.

- 39.Therell BL, Padilla CD, Loeber JG. Current status of newborn screening worldwide: 2015. Semin Perinatology. 2015;39:171–87. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grošelj U, Tanšek MZ, Šmon A. Newborn screening in Southeastern Europe. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;113:42–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.07.020. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grošelj U, Tanšek MZ, Battelino T. Fifty years of phenylketonuria newborn screening - a great success for many, but what about the rest? Mol Genet Metab. 2014;113(1-2):8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bilandžija I, Barić I, Škaričić A. Program proširenog novorodenačkog probira u Republici Hrvatskoj – zahtjevi i izazovi pravilnog uzimanja suhe kapi krvi. Peadiatr Croat. 2018;62(Suppl 1):10–4. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using tandem mass spectrometry for metabolic disease screening among newborns. MMWR. 2001;50:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.American College of Medical Genetics/American Society of Human Genetics Test and Technology Transfer Committee Working Group. Tandem mass spectrometry in newborn screening. Genet Med. 2000;2:267–9. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naylor EW. Automated tandem mass spectrometry for mass newborn screening for disorders in fatty acid, organic acid, and amino acid metabolism. J Child Neurol. 1999;14(Suppl 1):S4–8. doi: 10.1177/0883073899014001021. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Žerjav Tanšek M, Grošelj U, Murko S. Assessment of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)-responsiveness and spontaneous phenylalanine reduction in a phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency population. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107(1/2):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.010. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staudigl M, Gersting SW, Danecka DD. The interplay between genotype, metabolic state and cofactor treatment governs phenylalanine hydroxylase function and drug response. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2628–41. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr165. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karacic I, Meili D, Sarnavka V. Genotype-predicted tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)-responsiveness and molecular genetics in Croatian patients with phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97:165. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matern D. Acylcarnitines. Physician’s guide to diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of inherited metabolic diseases. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2014. pp. 775–84. –. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holm IA, Agrawal PB, Ceyhan-Birsoy O. The BabySeq project: implementing genomic sequencing in newborns. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1200-1. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson JM, Jungner YG. Principles and practice of mass screening for disease. Bol Oficina Sanit. 1968;65(4):281–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]