Abstract

The ability to retain an action plan to execute another is necessary for most complex, goal-directed behavior. Research shows that executing an action plan to an interrupting event can be delayed when it partly overlaps (vs. does not overlap) with the retained action plan. This phenomenon is known as partial repetition costs (PRCs). PRCs reflect proactive interference, which may be resolved by inhibitory, executive control processes. We investigated whether these inhibitory processes are compromised due to one night of sleep deprivation. Participants were randomized to a sleep-deprived group or a well-rested control group. All participants performed an action planning task at baseline after a full night of sleep, and again either after a night of sleep deprivation (sleep-deprived group) or a full night of sleep (control group). In this task, two visual events occurred in a sequence. Participants retained an action plan to the first event in working memory while executing a speeded action to the second (interrupting) event; afterwards, they executed the action to the first event. The two action plans either partly overlapped (required the same hand) or did not (required different hands). Results showed slower responses to the interrupting event during sleep deprivation compared to baseline and the control group. However, the magnitude of the PRCs was no different during sleep deprivation compared to baseline and the control group. Thus, one night of sleep deprivation slowed global responses to the interruption, but inhibitory processes involved in reducing proactive interference while responding to an interrupting event were not compromised. These findings are consistent with other studies that show sleep deprivation degrades global task performance, but does not necessarily degrade performance on isolated, executive control components of cognition. The possibility that our findings involve local as opposed to central inhibition is also discussed.

Introduction

The ability to interrupt and retain an action plan to execute another is critical in most complex, goal-directed behavior. For example, an airplane pilot may prepare an action in response to “low cabin pressure” but before executing this action, a response to a new signal indicating an “engine malfunction” may need to take precedence. Many goal-directed behaviors, such as piloting an airplane, driving, and performing surgery, are performed while the operator is sleep deprived. Thus, it is important to understand how sleep deprivation affects the ability to temporarily suspend one action plan to effectively execute another, as this ability has implications for safety (e.g., Fournier, Gallimore, Feiszli, & Logan, 2014; Logan, 2007).

Research shows that executing an action plan to an interrupting event can be delayed if it partly overlaps (vs. does not overlap) with the action plan temporarily put on hold (e.g., Hommel, Müsseler, Aschersleben, & Prinz, 2001; Hommel, 2005; Mattson & Fournier, 2008; Stoet & Hommel, 1999). However, it is not known whether these delays in responding to an interrupting event are exacerbated by sleep deprivation. If sleep deprivation causes larger delays in responding to interrupting events when the interrupting action plan overlaps with the action plan temporarily put on hold, this would suggest that inhibitory processes required in coordinating the order of action plan execution are compromised during sleep deprivation. The present study investigates this issue.

The delay in executing an action plan to an interrupting event when it partly overlaps with an action plan maintained in short-term or working memory is referred to as partial repetition costs. Partial repetition costs are assumed to occur when a feature from the action plan corresponding to the interrupting event (e.g., “left”) shares a feature with the action plan retained in working memory (e.g., “left” in the action plan “left hand move up”) and reactivates (primes) the action plan retained in working memory. This leads to proactive interference, which creates a temporary confusion as to which action plan is relevant for the current task: the action plan activated by the interruption or the action plan recently reactivated in working memory (Hommel, 2004, 2005; Mattson & Fournier, 2008; Mattson, Fournier, & Behmer, 2012). As a result, the recently reactivated plan in working memory must be inhibited to execute the action plan relevant to the interruption. This inhibition process takes time, and delays selection of the action plan relevant to the interrupting task (see also Fournier, Behmer, & Stubblefield, 2014; Fournier, Gallimore, et al., 2014; Meyer & Gordon, 1985; Sevald & Dell, 1994; Yaniv, Meyer, Gordon, Huff, & Sevald, 1990). On the other hand, if there is no feature overlap between action plans, then the action plan for the interrupting event will not reactivate the action plan retained in working memory. Hence no additional inhibition will be required to respond to the interrupting event, and there will be no partial repetition costs causing a delay.

Research shows that resolution of proactive interference within working memory may require cognitive or executive control processes associated with the prefrontal cortex (e.g., Badre & Wagner, 2005; Jonides & Nee, 2006). Research also indicates that larger partial repetition costs occur for individuals with low vs. high working memory spans (Fournier, Behmer, & Stubblefield, 2014) when working memory span was assessed using the Operation Span Task (Unsworth & Engle, 2007), assumed to measure cognitive control aspects of working memory with low working memory span individuals often showing poorer cognitive control. The larger partial repetition costs for individuals with low vs. high working memory spans were found when participants executed an action plan to a stimulus event (interruption) while retaining an action plan to a previous stimulus event in working memory. This suggests that the ability to inhibit inappropriate responses within working memory to coordinate the execution of a current action plan, particularly when the action plans partly overlap, may be related to cognitive control aspects of working memory (e.g., Conway & Engle, 1994; Engle, Conway, Tuholski, & Shisler, 1995; Engle, Kane, & Tuholski, 1999; Kane, Conway, Hambrick, & Engle, 2007; Redick et al., 2012; Roberts, Hager, & Heron, 1994; Rosen & Engle, 1998; Unsworth, Heitz, Schrock, & Engle, 2005)—although there is also evidence suggesting that event inhibition may occur at a local level in a different response paradigm that did not require retaining one action plan while executing another (Kühn, Keizer, Colzato, Rombouts, & Hommel, 2011; Hommel, Proctor, & Vu, 2004).

Our working memory span findings described above (Fournier, Behmer, & Stubblefied, 2014), which showed larger partial repetition costs for participants with low vs. high working memory spans when they executed an action plan to a stimulus event (interruption) while retaining an action plan to a previous stimulus event in working memory, suggest that partial repetition costs may be increased by poorer cognitive control when executing an action plan while retaining another in working memory. Most cognitive control models assume that there is a central conflict monitoring and/or inhibition system that exists in the lateral and/or medial frontal cortex or anterior cingulated cortex (e.g., Banich & Depue, 2015; Braver, Gray, & Burgess, 2007; Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001; Botvinick, Cohen, & Carter, 2004; Ridderinkhof, Ullsperger, Crone, & Nieuwenhuis, 2004). However, what is typically viewed to be a central inhibitory system may instead be a top–down system that maintains goals and then modulates activities in other brain regions—including biasing competition or inhibition at more local levels to meet task goals (see review by Friedman & Miyake, 2017). As such, cognitive control may be defined as either a central conflict monitoring system, a central inhibition system, or a top—down goal-maintenance system that biases local inhibition processes in alignment with task goals. Thus, if sleep deprivation functionally impairs cognitive control processes relevant to coordinating and selecting a current action plan while maintaining a future action plan for goal-directed behavior in working memory, then partial repetition costs should be larger when one is sleep-deprived compared to when one is well-rested.

Many sleep deprivation studies utilizing tasks assumed to assess deficits in executive functioning suggest that sleep deprivation leads to wide-ranging impairment of executive control processes (as reviewed in Lim & Dinges, 2010; Pilcher & Huffcutt, 1996). However, the literature is confounded with regard to whether sleep deprivation impairs specific, isolated components of executive functioning (Jackson et al., 2013), yielding mixed results (e.g., Jones & Harrison, 2001; Lo et al., 2012; Tucker, Stern, Basner, & Rakitin, 2011; Tucker, Whitney, Belenky, Hinson, & Van Dongen, 2010) including those related to response inhibition (Cain, Silva, Chang, Ronda, & Duffy, 2011; Sagaspe et al., 2006; see also Bratzke, Steinborn, Rolke, & Ulrich, 2012). These inconsistencies have been attributed to the task impurity problem, which posits that the decline in performance found for some executive functioning tasks during sleep deprivation may be due to degradation of non-executive processes (Whitney & Hinson, 2010). For example, performance on a modified Sternberg working memory task was shown to be globally impaired during sleep deprivation, but specific working memory processes involved in the task, such as working memory scanning efficiency, were found to be preserved (Tucker et al., 2010). Additionally, performance on a Stroop attention task showed global response impairment during sleep deprivation, but sleep-deprived and well-rested individuals showed a similar degree of response competition suggesting that the ability to inhibit competing responses was preserved for sleep-deprived individuals (Cain et al., 2011; Sagaspe et al., 2006; see also Bratzke et al., 2012). These findings suggest that sleep deprivation may not necessarily impact specific processes of executive function which are assumed to include interference resolution relevant to prepotent response inhibition or resistance to distractor interference.

Furthermore, there is uncertainty in the extent to which sleep deprivation impacts inhibition processes relevant to resisting (or resolving) proactive interference within working memory, which may be a different form of inhibition than that applied to prepotent responses or distractor interference (e.g., see Friedman & Miyake, 2004, 2017; Noël et al., 2013; Oberauer, 2009). In particular, the resistance to interference from memory, as in the case where an action plan is retained while executing another (i.e., resistance to proactive interference), may be different than resistance to interference from the environment (e.g., Stroop or flanker interference effects). In the former case, one must keep a goal in mind while giving priority to another. In the latter case, one must keep a goal in mind in the face of distracting perceptual information from the environment that conflicts with execution of that goal. It has been found that the ability to resist proactive interference from a prepotent response associated with the current stimulus based on a previous trial is preserved during sleep deprivation (Tucker et al., 2010), but whether that finding extends to interference from competing goals is unknown. There are multiple forms of inhibition that could possibly be involved during action selection (e.g., Friedman & Miyake, 2004) and, as such, it is not clear what the effects of sleep deprivation might be on tasks that have an inhibition component.

Thus, the question of whether sleep deprivation increases functional impairments in processes required to select action plans relevant to goal directed behavior is unresolved. Moreover, little is known in terms of how sleep deprivation affects planning and coordination of multi-step behaviors. Specifically, whether or not sleep deprivation affects executive control processes that may be involved in coordinating the execution of multiple action plans in which one action must be temporarily withheld to give priority to another has not been examined. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether sleep deprivation compromises inhibition processes within working memory that may be required to resolve proactive interference when coordinating the execution of multiple action plans to effectively respond to an interrupting event. We used a partial repetition paradigm (e.g., Stoet & Hommel, 1999) to examine whether partial repetition costs are different for individuals when they are sleep-deprived compared to when they are not. Importantly, the partial repetition paradigm allows for the dissociation of response measures relevant to inhibitory processes vs. global response performance, and hence circumvents the task impurity problem.

Participants were randomly assigned to a sleep-deprived group or a well-rested (control) group. They learned to execute different left- and right-hand actions in response to two different stimuli, presented in a serial order. They planned a response to the first stimulus event and retained this action plan in working memory, while waiting for the presentation of a second stimulus event (interruption) which required an immediate, speeded response. After executing a response to the second event, they executed the action plan retained in working memory corresponding to the first event. The actions for the first event and second event required either the same action hand (feature overlap) or a different action hand (no feature overlap). Participants performed this task in two sessions. In session 1 (baseline), both groups performed the task under normal sleep conditions. In session 2, the sleep-deprived group performed the task while 27.5 h into the sleep deprivation period, and the control group performed the task after a full night of sleep (at the same time of day).

As in our earlier work (Fournier, Behmer, & Stubblefield, 2014), we required participants to hold the first action plan active in working memory while executing an action plan to an interrupting event. We assumed that a central conflict monitoring and/or inhibition system would play a role in resolving partial repetition costs resulting from code confusion that must be resolved before a response can be executed to the interrupting event while maintaining a future action plan for goal-directed behavior in working memory. As such, if sleep deprivation compromises inhibition processes within working memory that are required to resolve proactive interference to coordinate the order of action plan execution and effectively respond to interruptions, then larger partial repetition costs should occur during sleep deprivation compared to baseline and compared to the control group. In contrast, if sleep deprivation leads to global response selection impairment, we should find an overall slowing of responses to the interrupting action during sleep deprivation regardless of feature overlap.

Method

Participants

As part of a larger study, 60 healthy adults were recruited from the community—40 were randomized to a sleep deprivation group and 20 to a control group. This 2:1 randomization ratio was determined prior to recruitment to allow for a separate investigation of individual differences in attentional control during sleep deprivation (reported in Whitney et al., 2017). Participants were healthy and free of drugs as assessed by questionnaires, interview, and physical examination. They had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing, were proficient English speakers, and had no history of a learning disability. Female participants were not pregnant. Participants reported good habitual sleep (between 6 and 10 h daily); regular bedtimes, waking between 06:00 and 09:00; no shift work within 3 months of entering the study; and no travel across time zones within 1 month of entering the study. Screening results and baseline polysomnography (Iber, Ancoli-Israel, Chesson, & Quan, 2007) during the first night in the laboratory revealed no sleep disorders.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington State University. All participants gave written, informed consent and were financially compensated for their time. Participants who failed to complete the action planning task (n = 4) or showed less than 70% accuracy at baseline (n = 7) were excluded from analysis.1 Thus, the sample considered here consisted of 49 participants (ages 22–37, M = 26.8, SD = 4.4; 26 men, 23 women): 34 in the sleep-deprived group and 15 in the control group.

Procedure

Participants were not to use caffeine, alcohol, tobacco products, or drugs in the 7 days prior to and during the study. Additionally, in the 7 days prior to the study, participants kept their regular bedtimes and refrained from daytime napping. Sleep instruction compliance was assessed by wrist actigraphy (Ancoli-Israel, 2005), sleep diary, and a time-stamped voice mail box that participants called at bedtime and upon awakening each day.

The study was conducted at the Washington State University’s Sleep and Performance Research Center. The laboratory was temperature controlled (21 ± 1 °C) and had fixed light levels (< 100 lux) during scheduled wakefulness and lights off during scheduled sleep periods. Participants were in the laboratory for 4 days and 3 nights consecutively. Up to 4 participants were in the laboratory at a time. Each participant had his/her own isolated room for sleep and performance testing. Meals were provided every 4 waking hours. Between test bouts and meals, participants were permitted only non-vigorous activities. No visitors, live radio or television, phone calls, text messages, e-mail or internet access was allowed. Participants were monitored continuously throughout the study by trained research personnel.

The first day and night in the laboratory served as a baseline period, with 10 h time in bed (TIB; 22:00–08:00) for polysomnographically recorded sleep. This was followed by 38 h of continuous wakefulness (for the sleep-deprived group) or another night with 10 h TIB (22:00–08:00) for polysomnographically recorded sleep (for the control group). The last night and subsequent day served as a recovery period, with 10 h TIB (22:00–08:00) for polysomnographically recorded sleep.

Psychomotor Vigilance Test

To ensure that our manipulation of sleep deprivation was successful, participants performed the Psychomotor Vigilance Test (Dinges & Powell, 1985). In this task, a number counter appears and begins counting up at random intervals, and the participant must press a button as quickly as possible to stop the counter. Response time on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test has been shown to reliably increase and become more variable with reduced sleep (e.g., Doran, Van Dongen, & Dinges, 2001; Lim & Dinges, 2008; Van Dongen, Maislin, Mullington, & Dinges, 2003), which is assumed to reflect increasing lapses of attention.

Participants performed the Psychomotor Vigilance Test at 09:00, 13:00, 17:00 and 21:00 during baseline (session 1), and 24 h later at the same times of day (session 2) while well-rested (control group) or sleep-deprived (sleep-deprived group), while seated at a desk in their respective laboratory room. Stimuli appeared against a black background on a 15-inch LCD screen, approximately 21 inches from the participant. Participants responded to the onset of a yellow, millisecond (ms) number counter that appeared within a red rectangle, centered on the screen. The fore-period prior to onset of the counter was randomized between 2 and 10 s in 1 s increments. Participants were instructed to press a button on a response box placed directly in front of them on the desk (using their dominant hand) as quickly as possible when the counter appeared (and not before). Following each response, the counter stopped and displayed the participant’s response time (RT) in ms for 1 s. The task duration was 10 min, and the number of times the counter appeared was dependent on how quickly the participants responded (with a typical range of 80–100 counter presentations). Performance was quantified as the number of lapses (RTs > 500 ms) per test bout, averaged over the four test bouts within each session.

Action planning task

Participants performed the action planning task in two different sessions, 24 h apart at 11:45 a.m., at a desk in their respective, laboratory room. Stimuli appeared against a black background on a 15-inch LCD screen, approximately 21 inches from the participant. Two keypads were secured to a board placed on the desk directly in front of the participant, with one keypad 4.76 cm to the left and the other 4.76 cm to the right of the participant’s body midline. The keypads recorded responses made with the index fingers; left-hand responses were executed on the left keypad and right-hand responses were executed on the right keypad. Each keypad had three vertically oriented keys (each 1 cm × 1 cm in size, separated by 0.2 cm). Participants rested their index fingers on the center keys before and during each trial. E-prime software 2.1 [Psychology Software Tools (2012), Sharpsburg, PA] presented stimuli and collected data. The stimuli and responses for the two visual events, the first event (Event A) and the second, interrupting event (Event B) were as follows.

Event A (first event, action plan retained in working memory)

Event A was an arrowhead (0.63° visual angle) pointing to the left or right and an asterisk (0.53° visual angle) located above or below the arrowhead (0.74° of visual angle). The arrowhead was centered above (2° visual angle) the central fixation cross (cross). The arrowhead direction (left or right) indicated the response hand (left or right, respectively). The asterisk (above or below the arrowhead) indicated the initial movement direction of the index finger relative to the center key on the keypad (upper key press, toward the LCD screen, or lower key press, toward the participant’s body, respectively). Thus, there were four different action plans (left hand-move up, left hand-move down, right hand-move up, and right hand-move down) mapped to the four different arrowhead-asterisk stimuli combinations. All Action A responses began and ended by pressing the appropriate left or right center key (home key) with the index finger.

Event B (interrupting event, action plan executed immediately)

Event B was a red or green number symbol (#, 0.67° visual angle) centered below the central fixation cross (2° visual angle). Action B required a speeded key press dependent on color. Half the participants pressed the left center key twice with their left hand in response to the green number symbol and pressed the right center key twice with their right-hand in response to the red number symbol; the other half had the opposite stimulus–response mapping. Multiple key presses were used so that both action B and action A required planning and preparation of multiple responses, consistent with previous research from our group using this paradigm.

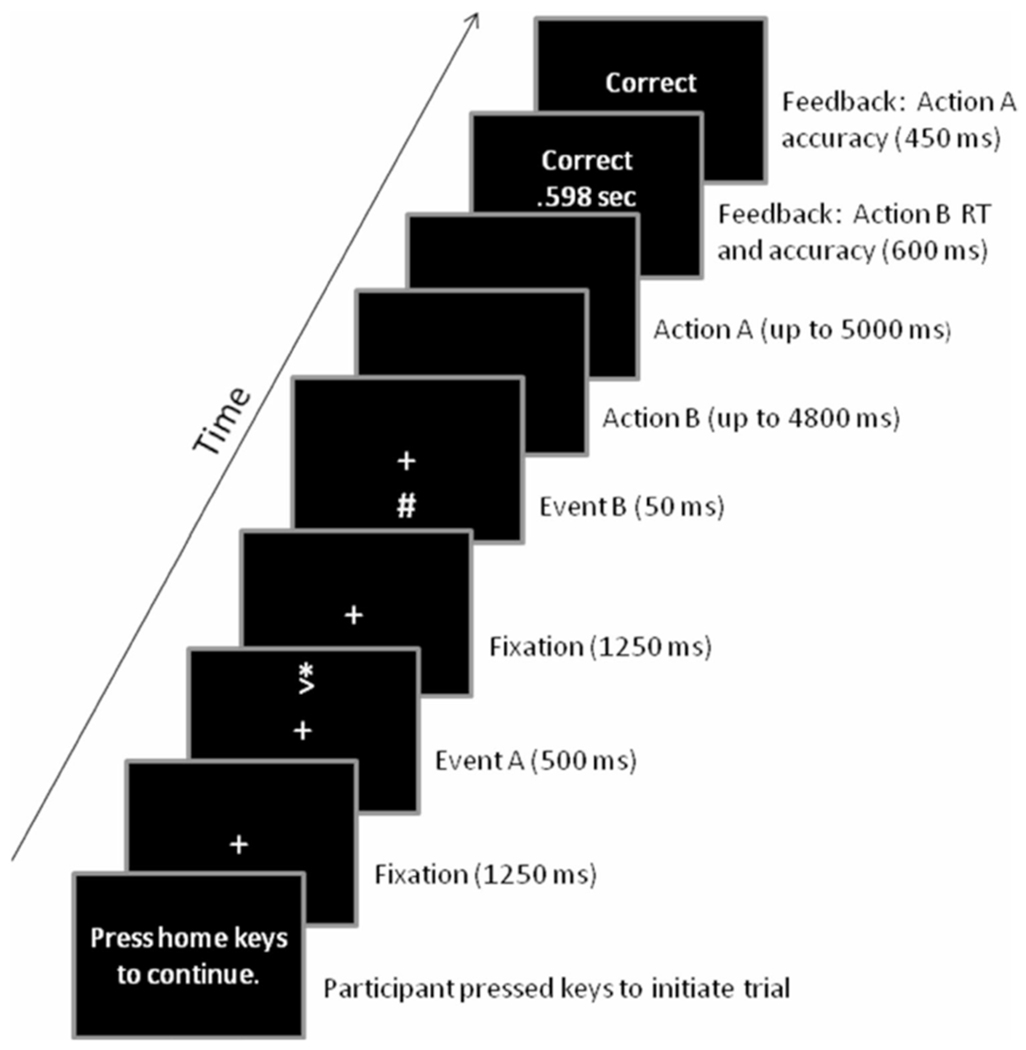

Figure 1 shows the trial events. Each trial began with an initiation screen with a message that read “press the home (center) keys to continue”. When the center keys were pressed simultaneously, the trial started, and a cross appeared in the center of the screen for 1250 ms. Subsequently, Event A appeared above the cross for 500 ms, followed by the cross alone for 1250 ms. During this time, participants planned Action A. Then, Event B (interruption) appeared below the cross for 50 ms, followed by a blank screen for 4800 ms or until Action B was detected. Participants were instructed to execute Action B as quickly and accurately as possible. After executing Action B, participants had 5000 ms to execute Action A retained in memory. Participants were instructed to execute Action A as accurately as possible. Action B reaction time (RT) and Action B accuracy feedback were then displayed for 600 ms, followed by Action A accuracy feedback for 450 ms. Afterwards, the initiation screen re-appeared, and participants initiated the next trial when ready.

Fig. 1.

The sequence and duration of events for each trial. The # symbol in the fifth panel was shown on the screen either in red or in green

Each test session contained 10 blocks of 24 trials and required approximately 45 min to complete. The first block of trials in each session was considered practice and was not analyzed. Mandatory 30-s breaks were imposed every three blocks. Participants were instructed not to execute any part of the planned response to Event A until after responding to Event B (the interruption). Additionally, they were not to move fingers or use external cues to help them remember the planned response to Event A—they were told to maintain the action to Event A (Action A) in memory. Participants were excluded from data analyses if they did not recall Action A with at least 70% accuracy in the feature overlap conditions in session 1. This occurred for two participants assigned to the sleep-deprived group and five participants assigned to the control group.

Design

Three factors were manipulated. First, the factor of Group was manipulated between participants. Participants were randomly assigned to either the sleep-deprived group or the well-rested (control) group in a 2:1 ratio. Second, the factor of session was manipulated within participants. The first test session took place at 11:45 a.m. after participants were awake for 3.75 h following the baseline night of sleep (baseline). The second test session was administered 24 h later, after participants were awake for 27.75 h (in the sleep-deprived group) or 3.75 h (in the control group). Third, the factor of Feature Overlap was manipulated within participants: Action B and Action A either required the same hand (overlap) or different hands (no overlap). All possible Event A and Event B stimuli were paired together equally often, in random order, within each block of trials.

Dependent variables

Mean correct RT and error rates for Action B (contingent on Action A accuracy) were measured to assess partial repetition costs. RT for Action B was calculated from the onset of Event B to the first key press required for Action B. Accuracy for Action A was measured to restrict performance evaluation of Action B to trials in which Action A was accurately maintained in working memory.2

Results

Psychomotor Vigilance Test

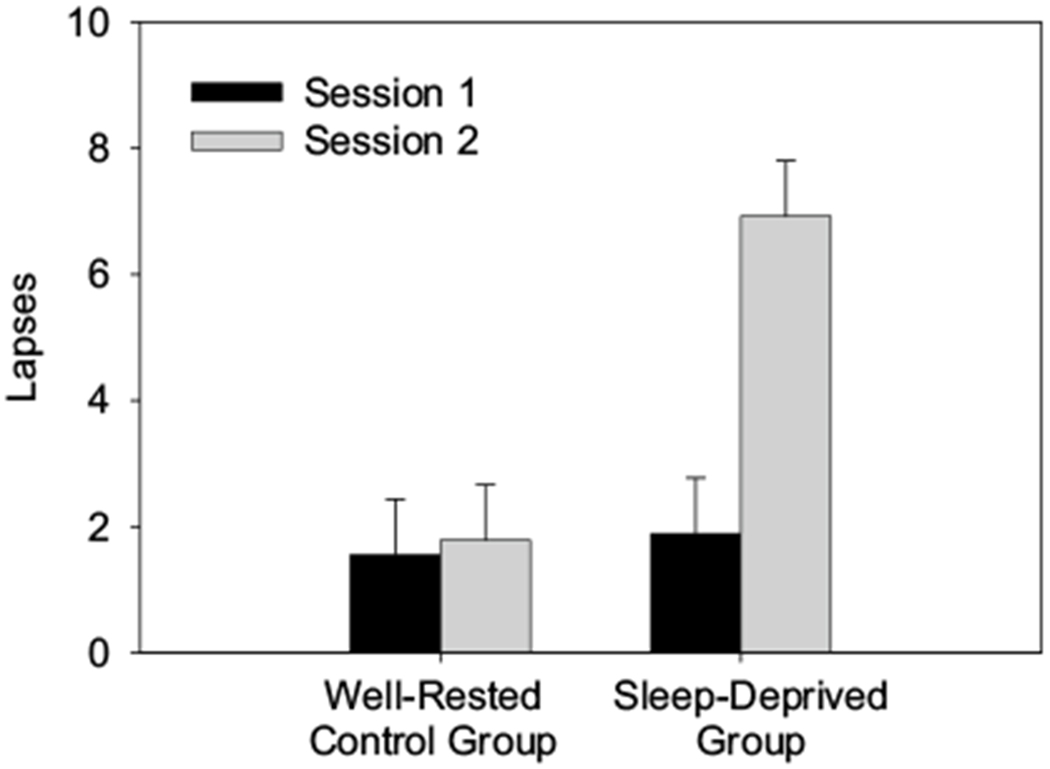

A 2 × 2 mixed design Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a between-subjects factor of Group (control, sleep-deprived) and a within-subjects factor of Session (session 1: baseline, session 2: control/deprivation) was conducted on Psychomotor Vigilance Test performance (mean number of lapses: RTs > 500 ms). Standard errors of the mean on this and other measures were calculated using the method by Masson and Loftus (2003). Figure 2 shows the mean number of lapses on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test for the control and sleep-deprived groups by session. There was a significant main effect of Group [F(1,47) = 8.14, p < .01, ], a significant main effect of Session [F(1,47) = 15.26, p < .001, ], and a significant interaction between Group and Session [F(1,47) = 12.67, p < .001, ]. These results show that the number of lapses on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test was similar for the control and sleep-deprived groups during session 1 (baseline; planned comparison, p > .51), but the number of lapses significantly increased for the sleep deprived group in session 2 (during sleep deprivation) compared to baseline (planned comparison, p < .001) and compared to the control group in session 2 (planned comparison, p < .01). Additionally, the number of lapses on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test did not significantly differ between sessions for the control group (planned comparison, p > .83). This suggests that our sleep deprivation manipulation was successful as performance on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test declined (i.e., the number of lapses increased) only for participants who were currently sleep deprived.

Fig. 2.

The mean number of lapses (RTs > 500 ms) in the Psychomotor Vigilance Test for the control group and the sleep-deprived group during session 1 (baseline) and session 2 (well-rested/sleep-deprived). Higher scores reflect greater attentional impairment. Error bars represent the within-subject, standard errors of the mean

Action planning task

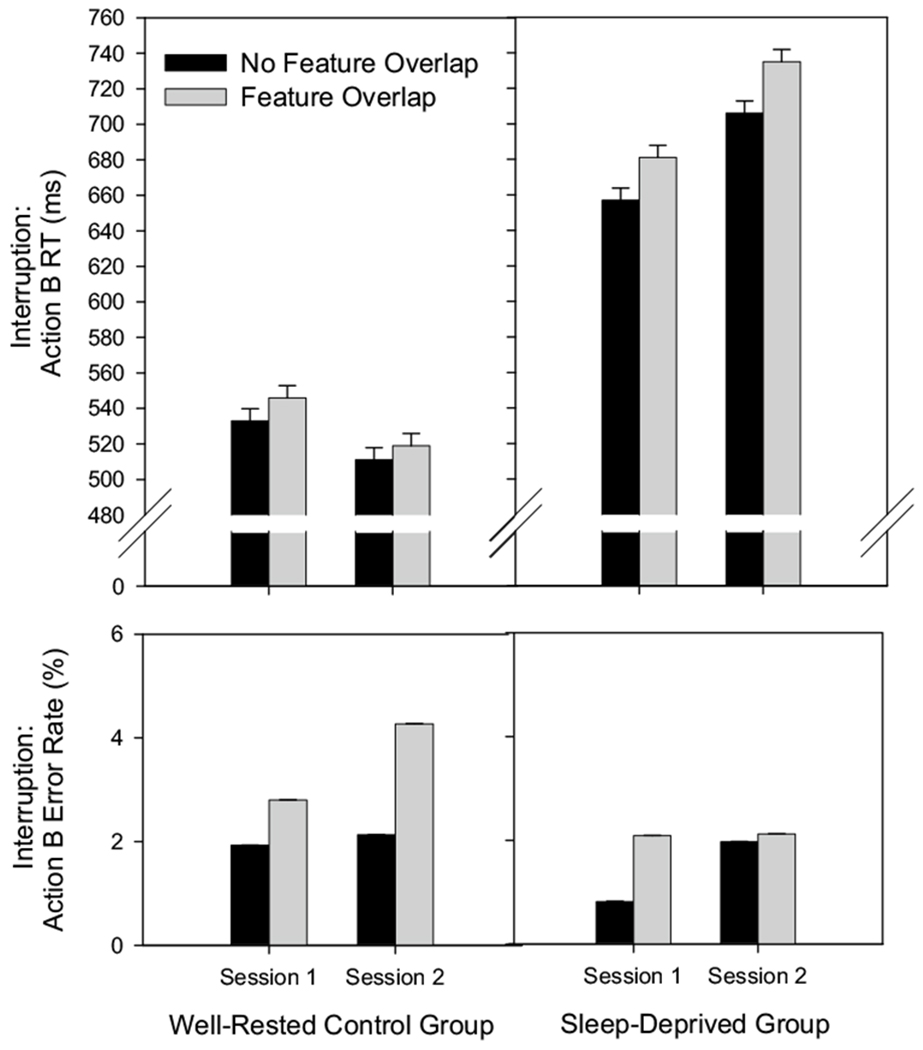

A 2 × 2 × 2 mixed design ANOVA with a between-subjects factor of Group (control, sleep-deprived) and within-subjects factors of Session (session 1: baseline, session 2: control/deprivation) and Feature Overlap (no overlap, overlap) was conducted separately on correct mean RT for Action B, mean error rate for Action B, and mean error rate for Action A. The correct RT and error analyses for Action B were restricted to trials in which Action A responses were correct. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni Pairwise Comparisons. Figure 3 shows the mean correct RT and error rates for Action B (response to the interruption) for the control and sleep-deprived groups by feature overlap and session. Table 1 shows the mean error rates for Action A (action plan retained in working memory) for the control and sleep-deprived groups by feature overlap and session.

Fig. 3.

RT and error rates to the interrupting event (Action B) for the control group (left panels) and the sleep-deprived group (right panels) by feature overlap condition (no overlap, overlap) during session 1 (baseline) and session 2 (well rested/sleep deprivation). Error bars represent the within-subject, standard errors of the mean

Table 1.

Mean error rates for the action plan retained in working memory (Action A)

| Session 1 (baseline) |

Session 2 (well-rested/sleep-deprived) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No feature overlap (%) | Feature overlap (%) | No feature overlap (%) | Feature overlap (%) | |

| Control group | 10.1 | 12.3 | 10.5 | 11.7 |

| Sleep-deprived group | 11.6 | 12.9 | 15.7 | 16.1 |

Within-subject, standard errors of the mean are 1.0%

Action B (action to the interrupting event)

As is evident in Fig. 3, RT was longer for the sleep-deprived group compared to the control group in session 1 (baseline). This outcome was unexpected. To determine whether the task was significantly more difficult for the sleep-deprived compared to the control group at baseline, a separate mixed design ANOVA with the between-subjects factors of Group and Feature Overlap during baseline only was conducted on action B RTs and error rates. For RTs, results showed a main effect of Group [F(1,47) = 10.51, p = .002, ] and a main effect of Feature Overlap [F(1,47) = 9.65, p = .003, ]; the interaction was not significant, F < 1. For error rates, results showed no significant effects (main effect of Feature Overlap, p > .08; main effect of Group and Group × Feature Overlap interaction, Fs < 1). Thus, our sleep-deprived group performed the task overall more slowly than our control group at baseline, prior to our main manipulation of sleep deprivation. Importantly, however, the group RT performance differences found during baseline did not interact with our primary factor of interest, feature overlap. Those assigned to the sleep-deprived group simply performed the task overall more slowly than those assigned to the control group. This group performance difference found at baseline will be addressed further in the discussion. However, it should not compromise our measures and interpretations of partial repetition costs, discussed below.

The 2 × 2 × 2 mixed design ANOVA conducted on RT showed that overall RT was significantly longer for the sleep-deprived group compared to the control group in both test sessions [main effect of Group: F(1,47) = 14.63, p < .001, ]. This implies that the task was overall more difficult for the participants assigned to the sleep-deprived group, both before and during sleep deprivation, compared to the control group. Additionally, overall performance RT for the sleep-deprived group was longer in session 2 (during sleep deprivation) compared to session 1 (baseline), while the RT for the control group did not significantly differ across sessions [Group × Session interaction: F(1,47) = 10.10, p < .01, ]. More specifically, overall RT increased for the sleep-deprived group across sessions (by M = 52 ms, p < . 01) due to sleep deprivation, but remained consistent for the control group across sessions with a trend toward improvement (by M = 25 ms, p = .06) due to practice. Moreover, RT was longer in the feature overlap condition compared to the no overlap condition for both the sleep-deprived and control groups in both sessions [main effect of Feature Overlap: F(1,47) = 9.7, p < .01, ], indicating partial repetition costs. However, the size of partial repetition costs did not differ between the sleep-deprived and control groups [Group × Feature Overlap interaction: F(1,47) = 1.85, p > .18], and the size of the partial repetition costs for the sleep-deprived group did not increase during sleep deprivation (session 2) compared to baseline or compared to the control group within or across sessions [Group × Session × Feature Overlap interaction: F < 1]. This indicates that the sizes of the partial repetition costs obtained for the sleep deprived group were similar during baseline (session 1) and during sleep deprivation (session 2). Additionally, the partial repetition costs obtained for the sleep deprived group were similar in size to those obtained for the control group within and across sessions. All remaining effects were not significant for RT (all ps > .26).

Consistent with the partial repetition costs found for RT, error rate for Action B was slightly, but significantly greater for the feature overlap (M=2.8%) compared to the no overlap (M = 1.7%) condition [main effect of Feature Overlap: F(1,47) = 14.25, p < .001, ]. In addition, error rate was slightly, but significantly greater in session 2 (M=2.6%) compared to session 1 (M = 1.9%) [main effect of Session: F(1,47) = 4.61, p < .05, ]. See Fig. 3. Further, the Group × Session × Feature Overlap interaction approached significance [F(1,47) = 3.88, p = .055, ], which shows that for the control group only, there was a trend toward increased error rate for the feature overlap, but not the no overlap condition, in session 2 relative to session 1. Thus, in contrast to predictions, the control group showed a trend toward a small increase in error-related partial repetition costs (approximately 1 %) with practice. No other significant effects were found (all ps > .18). Importantly, there was no evidence of a speed-accuracy tradeoff compromising the interpretations of the RT data reported above.

To further verify that the size of the PRC was not increased by sleep deprivation, we performed the same analyses above with the sleep deprived group alone. Repeated measures ANOVAs with the factor of feature overlap (overlap, no overlap) and session (baseline, sleep deprivation) were conducted on Action B correct mean RT and mean error rate. For RT, there was a significant main effect of Session [F(1,33) = 11.89, p < .002, ] and Feature Overlap [F(1,33) = 11.89, p < .001, ], but no significant Session × Feature Overlap interaction [F(1,33) = 0.17, p = .68]. For error rate, there was only a significant main effect of Feature Overlap [F(1,33) = 4.51, p < .05, ]. The main effect of Session [F(1,33) = 2.75, p > .10] and Session × Feature Overlap interaction [F(1,33) = 2.51, p > .12] were not significant. The results confirm, in contrast to our predictions, that the size of the PRC remained unchanged from well-rested baseline to sleep deprivation.

In sum, when considering the RT and error rate data together, there was no evidence that partial repetition costs increased for the sleep deprivation group during sleep deprivation (session 2) relative to baseline (session 1) or relative to the control group (sessions 1 and 2). However, there was an overall increase in RT for the sleep-deprived group during sleep deprivation (session 2) compared to baseline (session 1) —consistent with previous research on a variety of other performance tasks (e.g., Habeck et al., 2004; Honn et al., 2018; Tucker et al., 2010). This suggests that sleep deprivation slowed overall performance in the action planning task, but did not increase partial repetition costs.

Action A (action retained in working memory during the interrupting event)

The overall mean error rate in recalling Action A was 12.6%. Table 1 shows the Action A mean error rate for the control and sleep-deprived groups by feature overlap condition and session. There was a trend toward higher error rates for the feature overlap compared to the no overlap condition [Main effect: Feature Overlap, F(1,47) = 3.38, p = .072], and a trend toward increased error rates in recall for the sleep-deprived group during sleep deprivation (session 2) compared to baseline and the control group [Group by Session interaction, F(1,47) = 3.04, p = .088], but these trends were not significant. Additionally, no other main effects and interactions were significant (ps > .11 and ps > .47, respectively). These results indicate that errors in recalling the action plan retained in working memory (during the interrupting event) did not differ for the sleep-deprived group during sleep deprivation (session 2) compared to baseline (session 1) or compared to the control group (sessions 1 and 2) , and did not differ between the feature overlap conditions. The latter finding is consistent with past research, which has shown either no increase or a small increase in error rate for the feature overlap relative to the no overlap condition (e.g., Mattson, Fournier, & Behmer, 2012; Wiediger & Fournier, 2008). Thus, the interpretation of the RT findings for Action B (interruptions) was not compromised by differences in the ability to recall Action A (retained in working memory).

Discussion

This study showed that 27.5 h of total sleep deprivation (i.e., missing an entire night of sleep) slowed immediate responses to an interrupting stimulus event while retaining an action plan to another stimulus event in working memory. However, while RT to an interrupting visual event (Action B) was overall slower during sleep deprivation, the size of the partial repetition costs (the increase in RT when the interrupting action plan, Action B, and the action plan retained in working memory, Action A, overlapped vs. did not overlap) was no different during sleep deprivation compared to baseline or compared to a well-rested control group. We hypothesized that partial repetition costs should be larger due to 27.5 h of sleep deprivation, if sleep deprivation functionally impairs inhibition processes involved in reducing proactive interference between action plans within working memory. This hypothesis was not confirmed. Instead, our findings imply that sleep deprivation did not degrade executive control components that may be involved in reducing proactive interference while responding to an interrupting event. Our findings are consistent with other studies that show sleep deprivation degrades global task performance, but does not necessarily degrade performance on isolated, executive control components of cognition (Bratzke et al., 2012; Cain et al., 2011; Habeck et al., 2004; Honn et al., 2018; Jennings, Monk, & van der Molen, 2003; Tucker et al., 2010).

The finding that the size of partial repetition costs was unchanged during one night of sleep deprivation cannot be attributed to a failure in producing the experimental manipulation of sleep deprivation. Consistent with previous research (Doran et al., 2001; Van Dongen et al., 2003; Whitney et al., 2017), we found that performance on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test declined significantly (i.e., there was a considerably increased number of lapses, RTs > 500 ms) during sleep deprivation compared to baseline and compared to the well-rested control group. As previously mentioned, the Psychomotor Vigilance Test is a reliable measure of the effects of sleep deprivation on response performance, and it is often used as the “gold standard” measure of sleep deprivation (e.g., Lim & Dinges, 2008).

Previous researchers have argued that sleep deprivation impairs executive functioning (as reviewed in Harrison & Horne, 2000). However, claims that executive functioning is sensitive to impairment due to sleep loss are primarily based on observations of overall degradation of task performance during sleep deprivation (see Lim & Dinges, 2010; Pilcher & Huffcutt, 1996), as well as ancillary evidence from changes in EEG spectral power and brain activation patterns (see Durmer & Dinges, 2005; Harrison & Horne, 2000). Such findings can be misleading when the executive control processes and/or their neuronal substrates are not dissociated from other processes involved in task performance (Jackson et al., 2013; Whitney & Hinson, 2010). Our study showed that inhibition processes involved in reducing proactive interference between action plans (measured by partial repetition costs), when dissociated from overall task performance, are not compromised during sleep deprivation—but overall RT is compromised. Our study contributes novel evidence that some executive control processes, such as those assumed to be involved in the coordination of multiple action plans, may in fact be relatively well preserved even after a full night of total sleep deprivation.

We assumed that resolving proactive interference due to an interrupting event should involve cognitive or executive control. This assumption was based on research suggesting that conflict monitoring and/or inhibition requires cognitive control (e.g., Badre & Wagner, 2005; Banich & Depue, 2015; Braver et al., 2007; Botvinick et al., 2001, 2004; Friedman & Miyake, 2017; Kane et al., 2007; Ridderinkhof et al., 2004), continuous flow models of information processing (e.g., Coles, Gratton, Bashore, Eriksen, & Donchin, 1985), and in particular on the findings by Fournier, Behmer and Stubblefield (2014) who used the same dual-task paradigm and showed that partial repetition costs were greater for participants associated with low vs. high working memory span (assessed using the Operation Span Task by Unsworth & Engle, 2007). This latter result, in addition to the finding that low-span individuals often show poorer cognitive control (e.g., Conway & Engle, 1994; Engle, et al., 1995; 1999; Kane et al., 2007; Kane & Engle, 2003; Redick et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 1994; Unsworth et al., 2005) suggested that the size of partial repetition costs is likely influenced by cognitive control.

However, Kühn et al. (2011) showed that resolution of proactive interference due to partial feature overlap between events may occur at a local as opposed to a central level of processing. In their study, responses were executed immediately after stimulus presentation on each trial, and partial repetition (vs. no repetition) of the features from trial one on trial two led to delayed responding on trial two (a partial repetition cost), but fMRI results showed no evidence of suppression in the frontal lobe areas associated with cognitive control for partial repetition trials—suppression was found in local areas associated with feature processing relevant to the competing feature (e.g., left or right motor cortex). Thus, it could be argued that resolution of proactive interference in the current study may also be due to local inhibition processes as opposed to a central, cognitive control mechanism (see also Hommel, Proctor, & Vu, 2004), and that this is why we did not find greater partial repetition costs when participants were sleep-deprived vs. well-rested.

Although we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that resolving proactive interference in our study required only local processes as opposed to a central cognitive control mechanism, we believe this is unlikely for several reasons. First, trial contingencies based on separate trial events segmented in time (as in the study of Kühn et al., 2011) does not require one to temporarily retain a relevant action plan to an event in memory for future execution while executing a different action plan to an interrupting event (as in our study). Hence in our study, the action plan currently retained within working memory may more strongly compete with the new action event and hence require more cognitive control (i.e., central conflict monitoring or central inhibition). Second, inhibiting an action to a level just below response threshold would be desirable when one must retain an action plan in working memory (as in our study) so it can be executed in the immediate future, whereas more complete inhibition or blocking would be desirable for an action plan recently executed and no longer relevant (as in Kühn et al., 2011). Inhibiting a response just below threshold may require more of a balancing act between the current goal and the subsequent goal and may, therefore, rely more on cognitive control to resolve any current conflicts, whereas blocking could be a byproduct of higher activation of the correct response (e.g., Bjork, 1980). Third, the lack of evidence of a frontal lobe inhibition mechanism in the study of Kühn et al. (2011) could be due to the temporal insensitivity of the fMRI measure which may have hindered detection of brief changes in frontal lobe processing. Fourth, evidence of local vs. central inhibition in the Kühn et al. (2011) study does not rule out a mechanism of cognitive control, as some models assume that cognitive control provides a top-down mechanism that biases activation of correct responses that compete with incorrect responses through local lateral inhibition (see review by Friedman & Miyake, 2017). Fifth, other tasks (e.g., Stroop and Eriksen flanker tasks) shown to activate frontal lobe mechanisms associated with cognitive control have shown overall slower responding during sleep deprivation, but no significant increases in RT localized to response competition have been reliably found (e.g., Cain et al., 2011; Sagaspe et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2010)—consistent with our findings. Thus, it may be that sleep deprivation simply does not affect inhibition processes associated with highly learned and repetitive stimulus–response tasks.

Our finding that overall RT (regardless of action feature overlap) was slower during sleep deprivation compared to baseline, while inhibition processes relevant to proactive interference were preserved, raises the question of what aspects of task performance were degraded by sleep deprivation. It is possible that the dual-task aspect of our action planning paradigm, requiring a temporary shift from one action event to another, was responsible for overall performance impairment during sleep deprivation. However, the evidence on the effect of sleep deprivation on dual-task performance is mixed (Bratzke, Rolke, Steinborn, & Ulrich, 2009; Couyoumdjian et al., 2010; Drummond et al., 2001; Jennings, Monk, & Van der Molen, 2003). It is also possible that lapses of attention associated with increased RT instability due to sleep deprivation compromised overall task performance (see Lim & Dinges, 2010). However, this possibility leaves unexplained why executive control processes (e.g., inhibition processes) may have been preserved. Yet another possibility is that sleep deprivation reduces the ability to use preparatory bias to speed overall responses to the interrupting event. Consistent with this idea, a study examining sleep deprivation effects on distinct components of supervisory attention, including response inhibition, found that sleep-deprived individuals were unable to use strategic, preparatory bias to speed performance (Jennings et al., 2003). A failure to optimize preparatory strategies may explain why overall performance to the interrupting event was delayed while the cognitive component of inhibition was preserved.

A limitation of the present study is that performance between the sleep-deprived and control groups differed at baseline; the sleep-deprived group was overall slower to respond to the task interruption (regardless of feature overlap or no overlap) compared to the control group. Given the highly controlled laboratory setting of the study, it is unclear why this was the case—it may be attributable to random variation among our sample of individuals and their random assignment to condition or it may be due to participants’ a priori assumptions of group assignment, even though assignment to condition was not announced until after the baseline (first session) for both groups. Restricting data analysis inclusion to participants who could recall Action A (the retained action in working memory) with at least 70% accuracy in the baseline session, may also have contributed to baseline group difference, as we excluded five participants from the control group and only two from the sleep-deprived group. However, this criterion was necessary to ensure that participants, prior to the treatment (sleep deprivation/control), could perform the task (see footnote 2). Regardless, the baseline difference between groups did not compromise the interpretation of our results, because participants in each group served as their own baseline control when evaluating response performance to the interrupting event and when evaluating the size of partial repetition costs. Notably, the absence of a significant difference in the size of partial repetition costs within each group, as well as between the two groups, cannot be explained by the baseline difference.

Conclusion

Our results show that despite the overall degradation of performance to the interrupting event, resolution of proactive interference due to shared features between action plans was not compromised after nearly 28 h of total sleep deprivation. Our action planning paradigm and many other paradigms used to assess executive functioning (e.g., Stroop, Sternberg working memory, and task-switching) are convergent cognitive tasks, where the same standard information processing strategy can be used repeatedly. Some researchers have suggested that sleep loss may be more impactful in divergent cognitive tasks that are less routine and are more novel or require creative thinking (e.g., Harrison & Horne, 2000; Wimmer, Hoffmann, Bonato, & Moffitt, 1992). However, it can be argued that this is an attribution more so than an explanation of the phenomenon. Recent sleep deprivation studies employing a reversal learning paradigm (Satterfield et al., 2018; Whitney, Hinson, Jackson, & Van Dongen, 2015) and an AX continuous performance task with switching (Whitney et al., 2017) provide evidence that sleep deprivation affects the ability to properly process information that signals deviation from expectation—which would provide an explanation for why divergent cognitive tasks may be especially susceptible to performance impairment due to sleep loss. Further research is needed to examine whether and how executive control processes in divergent tasks may be specifically affected by sleep deprivation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Human Sleep and Cognition Laboratory in the Sleep and Performance Research Center at Washington State University for their help conducting the study. This research was supported by Office of Naval Research Grant N00014-13-1-0302.

Funding This research was supported by Office of Naval Research Grant N00014-13-1-0302 awarded to co-author, Hans Van Dongen.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

This criterion was less conservative than the criterion of 80% used in past studies with college students; applying the typical criterion of 80% would have led to a much larger exclusion (n = 17 participants). Importantly, the outcome of the study did not change when using a criterion of 70% or 80%; we chose to use 70% to include more participant data.

Assessing accuracy of Action A was necessary to ensure participants retained the action plan to the first event in memory while executing their response to the interruption (Action B). The accuracy results for Action A have to be interpreted with caution as participant inclusion required that they achieve 70% accuracy in the baseline session (session 1). However, there was no evidence that Action A accuracy was affected by any of the manipulations, which suggests that retaining and recalling action A was not significantly compromised by sleep deprivation in this study. Note also that RT for Action A was not analyzed as it was confounded with responses executed to Action B. That is, when there is feature overlap (i.e., Actions A and B share the same response hand), the motor response for Action A has to wait for Action B to finish before it can start, but when there is no feature overlap, the motor response for Action A does not necessarily have to wait for Action B to finish before it can start.

References

- Ancoli-Israel S (2005). Actigraphy In Kryger MH, Roth T & Dement WC (Eds.), Principles and practice of sleep medicine (fourth edn., pp. 1459–1467). Philadelphia: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Badre D, & Wagner AD (2005). Frontal lobe mechanisms that resolve proactive interference. Cerebral Cortex, 15(12), 2003–2012. 10.1093/cercor/bhi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT, & Depue BE (2015). Recent advances in understanding neural systems that support inhibitory control. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 1, 17–22. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA (1980). Retrieval inhibition as an adaptive mechanism in human memory In Roediger HI III & Craik FIM (Eds.), Varieties of memory and consciousness (pp. 309–330). Hillsdale: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, & Cohen JD (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, & Carter CS (2004). Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 539–546. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratzke D, Rolke B, Steinborn MB, & Ulrich R (2009). The effect of 40 h constant wakefulness on task-switching efficiency. Journal of Sleep Research, 18(2), 167–172. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratzke D, Steinborn MB, Rolke B, & Ulrich R (2012). Effects of sleep loss and circadian rhythm on executive inhibitory control in the Stroop and Simon tasks. Chronobiology International, 29(1), 55–61. 10.3109/07420528.2011.635235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Gray JR, & Burgess GC (2007). Explaining the many varieties of variation in working memory In Conway ARA, Jarrold C, Kane MJ, Miyake A & Towse JN (Eds.), Variation in working memory (pp. 76–108). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cain SW, Silva EJ, Chang A-M, Ronda JM, & Duffy JF (2011). One night of sleep deprivation affects reaction time, but not interference or facilitation in a Stroop task. Brain and Cognition, 76(1), 37–42. 10.1016/j.bandc.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles MGH, Gratton G, Bashore TR, Eriksen CW, & Donchin E (1985). A psychophysiological investigation of the continuous flow model of human information processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 11(5), 529–553. 10.1037/0096-1523.11.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway ARA, & Engle RW (1994). Working memory and retrieval: A resource-dependent inhibition model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 123(4), 354–373. 10.1037/0096-3445.123.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couyoumdjian A, Sdoia S, Tempesta D, Curcio G, Rastellini E, De Gennaro L, & Ferrara M (2010). The effects of sleep and sleep deprivation on task-switching performance. Journal of Sleep Research, 19, 64–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF, & Powell JW (1985). Microcomputer analyses of performance on a portable, simple visual RT task during sustained operations. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 17, 652–655. 10.3758/BF03200977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doran SM, Van Dongen HPA, & Dinges DF (2001). Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation: Evidence of state instability. Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 139, 253–267. 10.4449/aib.v139i3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond SP, Gillin JC, & Brown GG (2001). Increased cerebral response during a divided attention task following sleep deprivation. Journal of Sleep Research, 10(2), 85–92. 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmer JS, & Dinges DF (2005). Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Seminars in Neurology, 25(1), 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW, Conway ARA, Tuholski SW, & Shisler RJ (1995). A resource account of inhibition. Psychological Science, 6, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW, Kane MJ, & Tuholski SW (1999). Individual differences in working memory capacity and what they tell us about controlled attention, general fluid intelligence, and functions of the prefrontal cortex In Miyake A & Shah P (Eds.), Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. (pp. 102–134). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 10.1037/a0021324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier LR, Behmer LP Jr., & Stubblefield AM (2014). Interference due to shared features between action plans is influenced by working memory span. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 6, 1524–1529. 10.3758/s13423-014-0627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier LR, & Gallimore JM (2013). What makes an event: Temporal integration of stimuli or actions? Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 75(6), 1293–1305. 10.3758/s13414-013-0461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier LR, Gallimore JM, Feiszli KR, & Logan GD (2014). On the importance of being first: Serial order effects in the interaction between action plans and ongoing actions. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21(1), 163–169. 10.3758/s13423-013-0486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, & Miyake A (2004). The relations among inhibition and interference control functions: A latent-variable analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(1), 101–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, & Miyake A (2017). Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex, 86, 186–204. 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habeck C, Rakitin BC, Moeller J, Scarmeas N, Zarahn E, Brown T, & Stern Y (2004). An event-related fMRI study of the neurobehavioral impact of sleep deprivation on performance of a delayed-match-to-sample task. Cognitive Brain Research, 18(3), 306–321. 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Y, & Horne JA (2000). The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making: A review. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 6(3), 236–249. 10.1037/1076-898X.6.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B (2004). Event files: Feature binding in and across perception and action. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(11), 494–500. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B (2005). How much attention does an event file need? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 31(5), 1067–1082. 10.1037/0096-1523.31.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B, Musseler J, Aschersleben G, & Prinz W (2001). The theory of event coding (TEC): A framework for perception and action planning. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(5), 849–878. 10.1017/S0140525X01000103 (discussion 878–937). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B, Proctor RW, & Vu K-PL (2004). A feature-integration account of sequential effects in the Simon task. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 68, 1–17. 10.1007/s00426-003-0132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honn KA, Grant DA, Hinson JM, Whitney P, & Van Dongen HPA (2018). Total sleep deprivation does not significantly degrade semantic encoding. Chronobiology International. 10.1080/07420528.2017.1411361 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, & Quan SF (2007). The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events Rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson ML, Gunzelmann G, Whitney P, Hinson JM, Belenky G, Rabat A, & Van Dongen HPA (2013). Deconstructing and reconstructing cognitive performance in sleep deprivation. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 17(3), 215–225. 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JR, Monk TH, & Van der Molen MW (2003). Sleep deprivation influences some but not all processes of supervisory attention. Psychological Science, 14(5), 473–479. 10.1111/1467-9280.02456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, & Harrison Y (2001). Frontal lobe function, sleep loss and fragmented sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 5(6), 463–475. 10.1053/smrv.2001.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, & Nee DE (2006). Brain mechanisms of proactive interference in working memory. Neuroscience, 139(1), 181–193. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Conway ARA, Hambrick DZ, & Engle RW (2007). Variation in working memory capacity as variation in executive attention and control In Conway ARA, Jarrold MJC, Kane A, Miyake & Towse JN (Eds.), Variation in working memory (pp. 21–48). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, & Engle RW (2003). Working-memory capacity and the control of attention: The contributions of goal neglect, response competition, and task set to Stroop interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 132, 47–70. 10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn S, Keizer AW, Colzato LS, Rombouts SB, & Hommel B (2011). The neural underpinnings of event-file management: Evidence for stimulus-induced activation of and competition among stimulus-response bindings. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 896–904. 10.1162/jocn.2010.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, & Dinges DF (2008). Sleep deprivation and vigilant attention. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1129, 305–322. 10.1196/annals.1417.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, & Dinges DF (2010). A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychological Bulletin. 10.1037/a0018883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo JC, Groeger JA, Santhi N, Arbon EL, Lazar AS, Hasan S, Von Schantz M, Archer SN, & Dijk DJ (2012). Effects of partial and acute total sleep deprivation on performance across cognitive domains, individuals and circadian phase. PLoS One, 7(9), e45987 10.1371/journal.pone.0045987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD (2007). What it costs to implement a plan: Plan-level and task-level contributions to switch costs. Memory & Cognition, 35(4), 591–602. 10.3758/BF03193297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson MEJ, & Loftus GR (2003). Using confidence intervals for graphically based data interpretation. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57(3), 203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson PS, & Fournier LR (2008). An action sequence held in memory can interfere with response selection of a target stimulus, but does not interfere with response activation of noise stimuli. Memory & Cognition, 36(7), 1236–1247. 10.3758/MC.36.7.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson PS, Fournier LR, & Behmer LP (2012). Frequency of the first feature in action sequences influences feature binding. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74(7), 1446–1460. 10.3758/s13414-012-0335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DE, & Gordon PC (1985). Speech production: Motor programming of phonetic features. Journal of Memory and Language, 24(1), 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Noel X, Van der Linden M, Brevers D, Campanella S, Verbanck P, Hanak C, Kornreich C, & Verbruggen F (2013). Separating intentional inhibition of prepotent responses and resistance to proactive interference in alcohol-dependent individuals. Drub and Alcohol Dependency, 128(3), 200–205. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K (2009). Design for a working memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 51, 45–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher JJ, & Huffcutt AI (1996). Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: A meta-analysis. Sleep, 19(4), 318–326. 10.2466/pr0.1975.37.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychology Software Tools, Inc. [E-Prime 2.0]. (2012). http://www.pstnet.com.

- Redick TS, Broadway JM, Meier ME, Kuriakose PS, Unsworth N, Kane MJ, & Engle RW (2012). Measuring working memory capacity with automated complex span tasks. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(3), 164–171. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, Ullsperger M, Crone EA, & Nieuwenhuis S (2004). The role of the medial frontal cortex in cognitive control. Science, 306, 443–447. 10.1126/science.1100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ, Hager LD, & Heron C (1994). Prefrontal cognitive processes: Working memory and inhibition in the antisaccade task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 123(4), 374–393. 10.1037/0096-3445.123.4.374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen VM, & Engle RW (1998). Working memory capacity and suppression. Journal of Memory and Language, 39(3), 418–436. 10.1006/jmla.1998.2590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sagaspe P, Sanchez-Ortuno M, Charles A, Taillard J, Valtat C, Bioulac B, & Philip P (2006). Effects of sleep deprivation on color-word, emotional, and specific Stroop interference and on self-reported anxiety. Brain and Cognition, 60(1), 76–87. 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield BC, Hinson JM, Whitney P, Schmidt MA, Wisor JP, & Van Dongen HPA (2018). Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genotype affects cognitive control during total sleep deprivation. Cortex, 99, 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevald CA, & Dell GS (1994). The sequential cuing effect in speech production. Cognition, 53(2), 91–127. 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoet G, & Hommel B (1999). Action planning and the temporal binding of response codes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 25(6), 1625–1640. 10.1037/0096-1523.25.6.1625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AM, Stern Y, Basner RC, & Rakitin BC (2011). The prefrontal model revisited: Double dissociations between young sleep deprived and elderly subjects on cognitive components of performance. Sleep, 34(8), 1039–1050. 10.5665/sleep.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AM, Whitney P, Belenky G, Hinson JM, & Van Dongen HPA (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on dissociated components of executive functioning. Sleep, 33(1), 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth N, & Engle RW (2007). On the division of short-term and working memory: An examination of simple and complex spans and their relation to higher-order abilities. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 1038–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth N, Heitz RP, Schrock JC, & Engle RW (2005). An automated version of the operation span task. Behavior Research Methods, 37, 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen HPA, Maislin G, Mullington JM, & Dinges DF (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep, 26(2), 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P, & Hinson JM (2010). Measurement of cognition in studies of sleep deprivation. Progress in Brain Research, 185, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P, Hinson JM, Jackson ML, & Van Dongen HPA (2015). Feedback blunting: Total sleep deprivation impairs decision making that requires updating based on feedback. Sleep, 18(5), 745 10.5665/sleep.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P, Hinson JM, Satterfield BC, Grant DA, Honn KA, & Van Dongen HPA (2017). Sleep deprivation diminishes attentional control effectivenss and impairs flexible adaptation to changing conditions. Scientific Reports, 7, 1–9. 10.1038/s41598-017-16165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiediger MD, & Fournier LR (2008). An action sequence withheld in memory can delay execution of visually guided actions: The generalization of response compatibility interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 34(5), 1136–1149. 10.1037/0096-1523.34.5.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer F, Hoffmann RF, Bonato RA, & Moffitt AR (1992). The effects of sleep deprivation on divergent thinking and attention processes. Journal of Sleep Research, 1(4), 223–230. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv I, Meyer DE, Gordon PC, Huff CA, & Sevald CA (1990). Vowel similarity, connectionist models, and syllable structure in motor programming of speech. Journal of Memory and Language, 29(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar]