Abstract

Background:

Evidence about sex differences in management and outcomes of critical limb ischemia (CLI) is conflicting.

Methods:

We identified Fee-For-Service Medicare patients within the 5% enhanced sample file who were diagnosed with new incident CLI between 2015 and 2017. For each beneficiary, we identified all hospital admissions, outpatient encounters and procedures, and pharmacy prescriptions. Outcomes included 90-day mortality and major amputation.

Results:

Incidence of CLI declined from 2.80 (95% CI 2.72-2.88) to 2.47 (95% CI 2.40-2.54) per 1000 person from 2015 to 2017, P<0.01. Incidence was lower in women compared to men (2.19 vs 3.11 per 1000) but declined in both groups. Women had a lower prevalence of prescription of any statin (48.4% versus 52.9%, P<0.001) or high-intensity statins (15.3% versus 19.8%, P<0.01) compared with men. Overall, 90-day revascularization rate was 52% and women were less likely to undergo revascularization 50.1% versus 53.6%, P<0.01) compared with men. Women had a similar unadjusted (9.9% versus 10.3%, P=0.5) and adjusted 90-day mortality (adjusted RR (aRR) 0.98, 95% CI 0.85-1.12, P=0.7) compared with men. Over the study period, unadjusted 90-day mortality remained unchanged for men (10.4% in 2015 to 9.9% in 2017, P for trend =0.3), and women (9.5% in 2015 to 10.6% in 2017, P for trend =0.2). Men had higher unadjusted (12.9% versus 8.9%, P<0.001) and adjusted risk of 90-day major amputation (aRR 1.30, 95% CI 1.14-1.48, P<0.001). One-third of CLI patients underwent major amputation without a diagnostic angiogram or trial of revascularization in the preceding 90 days regardless of the sex.

Conclusion:

Women with new incident CLI are less likely to receive statin or undergo revascularization at 90 days compared to men. However, the differences were small. There was no difference in risk of 90-day mortality between both sexes.

Keywords: Critical limb ischemia, sex disparities, major amputation

Subject terms: Peripheral arterial disease, amputation, female, mortality

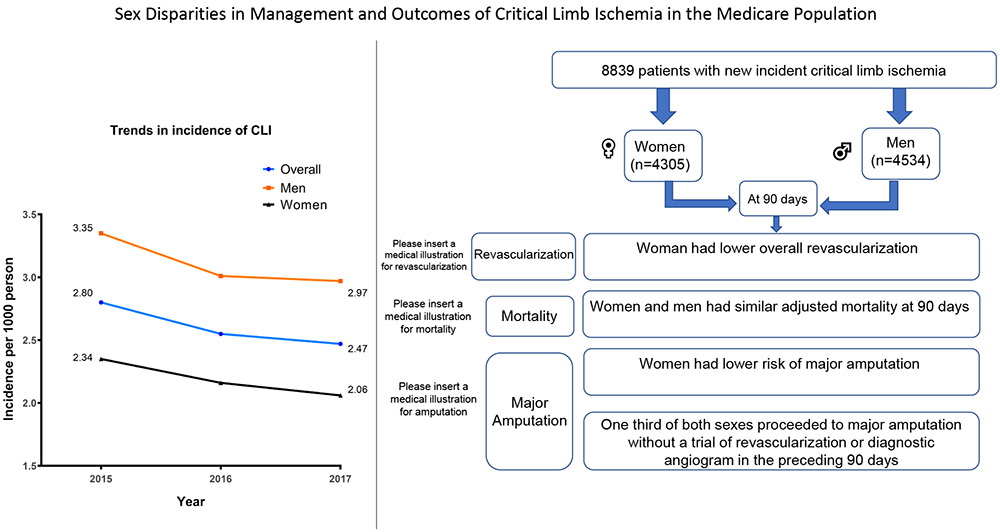

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) continues to rise in the United States, with aging of the population and the increasing prevalence for atherosclerosis risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension.1 Critical limb ischemia (CLI), represents an advanced stage of PAD that results in rest pain, ulceration, and tissue loss.2 Approximately 20-40% of CLI patients undergo amputation in 1 year and one in five patients die by six months.2 Revascularization, if feasible, is recommended in CLI patients to improve symptoms and prevent amputation.3

Sex disparities in diagnosis, management, and outcomes between men and women have been demonstrated in other cardiovascular diseases.4, 5 Although prevalence of PAD is similar between men and women, 6, 7 women with PAD present with atypical symptoms and poor health status,8 and experience worse outcomes after revascularization.9-11 Sex disparities in management and outcomes of CLI have not been well described.12, 13 The American Heart Association (AHA) has issued a “Call to Action” statement to demonstrate the need for more research on sex disparities in PAD.7

To address this gap in knowledge, we used Medicare data, which included inpatient, outpatient and medications claims from a contemporary cohort to 1) study trend of incidence of CLI in men and women in the United States in the past few years, and 2) examine differences in management and outcomes between men and women in a contemporary cohort.

Methods

Data Sources

The study cohort was derived from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administrative data. Data used for the study are covered under a data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and are not available for distribution by the authors but may be obtained from CMS with an approved data use agreement. The following files were utilized: 1) Inpatient Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) File which includes all inpatient hospital admissions for Medicare beneficiaries. 2) The Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, which includes demographic data and enrollment dates for Beneficiaries. 3) The Medicare Carrier (Part B) Standard Analytic File which includes outpatient encounters, institutional and outpatient procedures for a 5% representative rolling cohort of Medicare beneficiaries. 4) The Pharmacy Drug Event (Part D) file which includes pharmacy claims for Medicare beneficiaries in the 5% sample who are enrolled in Part D.

Study cohort

To assess CLI incidence in men and women, we used the 5% Medicare data to identify all patients age 65 and older with an outpatient or inpatient encounter from January 2015 through December 2017 for a primary diagnosis of CLI using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-codes version 9 and 10 definitions, which were used in prior studies (Supplemental Table 1).14-16 We restricted the analysis to patients with a primary diagnosis of CLI to increase specificity and to avoid including patients with a historical diagnosis of CLI. To ensure that the encounter is for new incident CLI, we utilized a look back period of one year, to ensure there was no prior diagnosis of CLI in outpatient or inpatient setting in the prior year. For patients with multiple encounters of CLI during a 12-month period, we only included the first encounter. We excluded patients enrolled in Medicare advantage during the year of CLI admission, and patients not enrolled in Medicare Part D at the year of CLI diagnosis.

Study variables

The primary exposure variable for examining CLI incidence, management, and outcomes was sex (male or female) as reported in the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File. Demographic variables included age and race. Co-morbidities were identified using the index encounter as well as all inpatient hospitalizations and outpatient visits during the one-year look-back period using algorithms based on ICD codes that have been validated in administrative databases.17 We extracted all procedures, including endovascular, surgical and hybrid revascularization, and major amputation, before and after the CLI admission dates from the inpatient and outpatient-based Files using ICD and CPT codes for procedure definitions are outlined in Supplemental Table 2 and 3. Medicare Part D Files were used to extract pharmacy claims for cardiovascular medications such as non-aspirin antiplatelets (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, and ticagrelor), anticoagulants (warfarin, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran), beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEI/ARB), cilostazol and pentoxifylline. We also extracted statins prescriptions for the study cohort. High-intensity statin was defined as atorvastatin 40-80 mg, rosuvastatin 20-40 mg, or simvastatin 80 mg.

Outcomes

The study primary outcome was 90-day all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included 90-day revascularization, 90-day major amputation, and one-year mortality. Outcomes included outpatient and inpatient procedures. We excluded patients presenting after September 2017 to ensure 90 days of follow up. Major amputation was defined as any amputation at or above the ankle level using ICD and CPT codes (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). We excluded minor amputation from outcomes. Among patients who underwent major amputation, we evaluated whether they had undergone an invasive angiogram or revascularization in the 90 days prior to amputation. Follow up for mortality was available through September 2018 and for amputation through December 2017. The Institutional board review at the University of Iowa approved the study with waiver of individual informed consent.

Statistical analysis.

The incidence of CLI in a given year was calculated by including total number of new CLI encounters in the numerator, and total number of Medicare enrollees, who were 65 years or older except those enrolled in Medicare Advantage program on that year in the denominator. We examined temporal trends in incidence using Mantel Hansel test.

A mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression with hospitals as a random-effects was utilized to compare the primary and secondary outcomes of 90-day mortality and major amputation respectively, between men and women, adjusting for differences in age, race, and comorbidities. We also examined interactions between race or ethnicity and sex in multivariable outcomes models. As rates of our study primary and secondary outcomes exceeded 10%, we utilized a Poisson distribution with log link function to directly estimate rate ratio (RR) instead of odds ratio as previously described.18 A P value of 0.05 was chosen for statistical significance. The analysis was done with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute) and R 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Incidence of CLI admissions

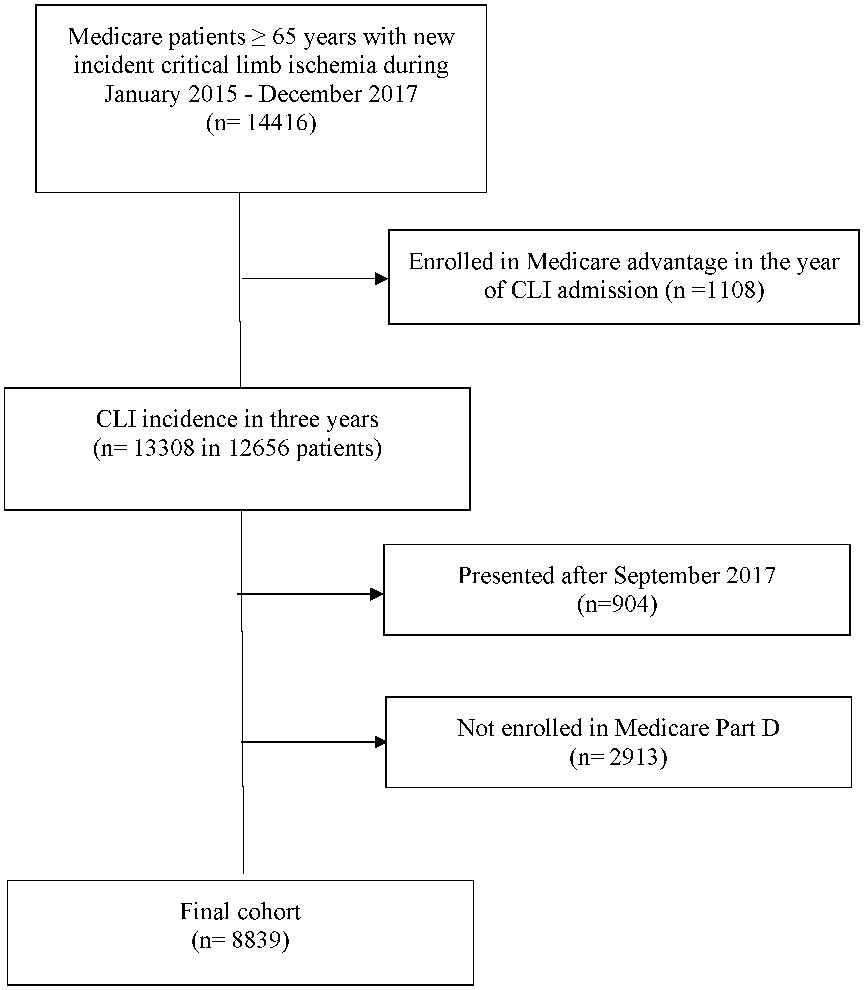

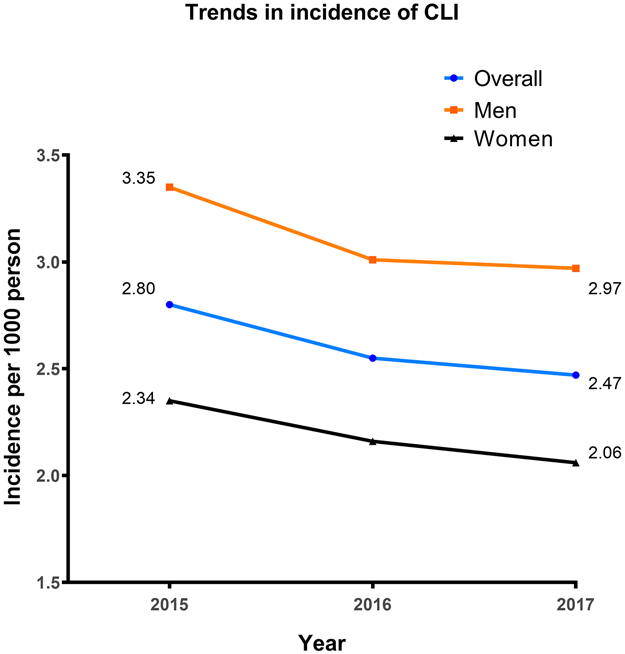

From January 2015 to September 2017, 14,416 new incident CLI encounters were identified in Medicare patients ≥65 years old from the 5% sample. We excluded 1108 patients who were enrolled in Medicare advantage during the year of CLI admission, which resulted in a total of 13,308 incidence CLI in 12,656 patients over the study period. Out of those 12,656 patients, 8,123 (64%) patients were managed in an outpatient setting without hospital admission. Figure 1 illustrates the flow chart for the study cohort creation. The overall Incidence of CLI during the study period was 2.61 (95% CI 2.53-2.68) per 1000 person and decreased from 2.80 (95% CI 2.72-2.88) to 2.47 (95% CI 2.40-2.54) per 1000 person from 2015 to 2017 respectively, P for trend <0.01. Incidence of CLI admissions was lower in women compared to men (2.19 vs 3.11 per 1000 person) and decreased by 12% in both women and men (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Flow chart of the study cohort

Figure 2:

Incidence of critical limb ischemia in men and women over the study period.

CLI management

Of the 11,752 CLI patients, who presented from January 2015-September 2017, we excluded 2913 patients who were not enrolled in Part D, leaving 8,839 eligible patients for evaluation of management and outcomes (women n=4305, men n= 4534). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Women with CLI were older (mean age 78.7±8.7 versus 75.8±7.6 years, P<0.001) and more commonly of the black race. Men had a higher prevalence of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, smoking, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and coronary artery disease compared to women. Women had a higher rate of calcium channel and beta-blockers prescription on discharge (up to 90 days post discharge) but a lower rate of any statin (48.4% versus 52.9%, P<0.01) and high-intensity statin prescriptions (15.3% versus 19.8%, P<0.01) compared to men (Table 2).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of the study population in both sexes

| Variable | Males N=4534 |

Female N=4305 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 75.8±7.6 | 78.7±8.7 | <0.0001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 77.8 | 76.4 | <0.0001 |

| Black | 14.7 | 17.4 | |

| Asian | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

| Hispanic | 3.3 | 2.9 | |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 30.4 | 28.7 | 0.09 |

| Coronary artery disease | 67.0 | 51.2 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 69.2 | 58.4 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 93.9 | 93.3 | 0.3 |

| Congestive heart failure | 43.9 | 38.9 | <0.001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 31.5 | 29.8 | 0.07 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 37.0 | 29.3 | <0.001 |

| Prior Intracardiac defibrillator | 8.0 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Prior Smoking | 30.5 | 21.8 | <0.001 |

| Prior bleeding | 25.9 | 21.3 | <0.001 |

| Prior cerebral hemorrhage | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 32.6 | 26.6 | <0.001 |

| End stage renal disease | 13.5 | 9.8 | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 8.5 | 6.0 | <0.001 |

| Prior peripheral endovascular revascularization | 21.6 | 20.4 | 0.2 |

| Prior major amputation | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.04 |

| Prior peripheral surgical revascularization | 4.9 | 3.6 | 0.3 |

| Hypothyroidism | 19.5 | 34.6 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 41.1 | 41.9 | 0.4 |

| Coagulopathy | 13.5 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Connective tissue disease | 7.2 | 14.1 | <0.0001 |

| Anemia | 50.9 | 50.5 | 0.7 |

| Depression | 21.9 | 26.5 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphoma | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.1 |

| Alcohol abuse | 6.6 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 24.3 | 21.8 | 0.005 |

| Psychosis | 8.5 | 10.7 | 0.001 |

| Sleep apnea | 16.7 | 10.2 | <0.001 |

Table 2:

Prevalence of medications prescriptions at discharge (up to 90 days after discharge)

| Variable | Males N=4534 |

Female N=4305 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulation | 19.3 | 15.8 | <0.001 |

| Non-aspirin antiplatelets | 35.2 | 33.9 | 0.2 |

| Any statin | 52.9 | 48.4 | <0.001 |

| High intensity statin | 19.8 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

| Beta Blockers | 32.3 | 35.2 | 0.003 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 23.2 | 29.3 | <0.001 |

| ACE or ARB | 41.4 | 43.7 | 0.03 |

| Cilostazol | 4.8 | 4.5 | 0.6 |

| Pentoxifylline | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

ACE=Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker

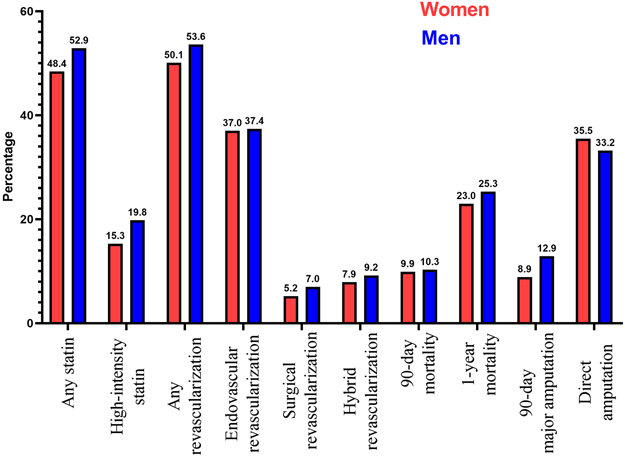

Overall, 90-day revascularization rate was 51.9% in the cohort. The most common modality at 90 days was endovascular revascularization (37.2%) followed by surgical revascularization (6.1%) and hybrid revascularization (8.6%). Overall, women had a lower rate of 90-day any revascularization (50.1% versus 53.6%, P<0.01). Women had similar rate of 90-day endovascular revascularization (37.0% versus 37.4%, P=0.7) but a lower rate of 90-day surgical revascularization (5.2% versus 7.0%, P<0.01) and 90-day hybrid revascularization (7.9% versus 9.2%, P=0.03) compared to men (Table 3).

Table 3:

In-hospital and 90-day utilization of invasive procedures, and outcomes in CLI patients

| Variable | Males N=4534 |

Female N=4305 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90-day major amputation | 12.9 | 8.9 | <0.001 |

| 90-day endovascular revascularization | 37.4 | 37.0 | 0.7 |

| 90-day surgical revascularization | 7.0 | 5.2 | <0.001 |

| 90-day hybrid revascularization | 9.2 | 7.9 | 0.03 |

| 90-day any revascularization | 53.6 | 50.1 | <0.001 |

| 90-day mortality | 10.3 | 9.9 | 0.5 |

| 1-year mortality | 25.3 | 23.0 | 0.01 |

CLI outcomes

Women had a similar unadjusted (9.9% versus 10.3%, P=0.5) and adjusted 90-day mortality (adjusted RR (aRR) 0.98, 95% CI 0.85-1.12, P=0.7) compared to men (Supplemental Table 4). Statin use and revascularization were associated with lower risk of 90-day mortality (aRR 0.45, 95% CI 0.36-0.51, P<0.001) and (aRR 0.13, 95% CI 0.04-0.42, P<0.001) respectively. Over the study period, unadjusted 90-day mortality remained unchanged for men (10.4% in 2015 to 9.9% in 2017, P for trend =0.3), and women (9.5% in 2015 to 10.6% in 2017, P for trend =0.2). There was no difference in adjusted one-year mortality between men and women (aRR 1.08, 95% CI 0.98-1.18, P=0.1).

Men had higher unadjusted risk of 90-day major amputation compared to women (12.9% versus 8.9%, P<0.001). After multivariable adjustment, male sex remained associated with a higher risk of 90-day major amputation (aRR 1.30, 95% CI 1.14-1.48, P<0.001). Revascularization was not associated with a lower risk of 90-day major amputation (aRR 1.10, 95% CI 0.96-1.25, P=0.2) (Supplemental Table 5). Among patients with CLI who underwent an amputation, nearly one-third did not have an angiogram or revascularization attempt in the 90 days prior to amputation and these differences were not significantly different between women and men (35.5% versus 33.2%, P=0.4) (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

comparison of different study outcomes between men and women.

There was no difference in risk of 90-day mortality between Black and White races (11.0% versus 9.8%, P=0.2). On logistic regression, there was no significant interaction between race and sex in the outcome of 90-day mortality (p for interaction = 0.9). Black race was associated with higher risk of 90-day amputation compared to White race (20.1% versus 9.0%, P<0.001). On interaction analysis, there was no significant interaction between sex and race on the outcome of 90-day amputation (p for interaction = 0.1).

Discussion

In this study, we report several important findings. First, incidence of CLI was high in both sexes, but declined from 2015 to 2017 equally in both men and women enrolled in Medicare in the United States. Second, overall utilization of revascularization at 90 days was 51.9% and women were less likely than men to undergo revascularization. Third, approximately 50% of patients were not prescribed statins at discharge, with lower rates of statin prescription in women compared to men. Fourth, 90-day and 1-year mortality rates were high in both sexes with 1-year mortality of 23.0%. after adjusting for age and comorbidities, there was no difference in mortality in short and midterm follow up between men and women. Last, men had higher rates of major amputation compared to women, and in both sexes, one in three proceeded to amputation without diagnostic angiogram or trial for revascularization.

The incidence of CLI in our study, 2.60 per 1000 person, is high compared to two prior studies from the Medicare population, were incidence was reported to be 2.00 per 1000 person.19, 20 This is probably due to the inclusion of patients who were managed on outpatient setting without admission in our study in addition to patients from the inpatient setting.19, 20 Our study showed that incidence of CLI is declining in both men and women over the study four years. The declining incidence of CLI was also shown recently in the Veterans population.16

The under prescription of statins and sex disparities in statin prescription in secondary prevention for cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and PAD have been reported in the past. 21-24 Our study showed lower prescription of statins in women after CLI compared to men. However, differences were small. Potential explanations proposed to explain the lower prevalence of statin prescription in women include older age, less referral to a cardiologist, and higher incidence of statin intolerance.25 A study from Medicare population in 2008 showed that prevalence of statin prescription in patients with CLI was 49%.26 Our study showed that statin prescription did not improve in 2017 compared to 2008, where the prevalence of statin prescription remained 50% despite a strong recommendation by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.3 Prevalence of high-intensity statin prescription was even lower and remained <20% in both men and women.

The ACC/AHA guidelines provide a strong recommendation for revascularization when feasible in patients with CLI to lower the risk of limb loss and to improve quality of life.3 In our study, the overall preferred modality for revascularization was endovascular revascularization. This is consistent with nationwide trends shown in a prior study from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.14 Overall, revascularization rates in our study were 52%, which is significantly higher compared to 29% in 2007 from a prior study in Medicare population.19 Furthermore, in our study, women were less likely to undergo any revascularization at 90 days compared to men, which was mainly due to lower utilization of surgical and hybrid revascularization in women. However, differences in revascularization between both sexes were small. The preferential use of endovascular modality in women could potentially be explained by the older age and lower prevalence of kidney disease compared to men. It could also be related to prior reports showing possible higher rate of graft failure, wound infection, bleeding complications, and higher mortality following surgical revascularization in women compared to men. 9-11, 27

In our study, we excluded minor amputation from outcomes, as in many instances, minor amputation is part of a vascular plan and is performed due to non-viable or non-salvageable tissue. We focused on major amputations as these are known to affect mobility of CLI patients more than minor amputations. In a prior study from Medicare in 2006, 52% of CLI patients who underwent major amputation did not receive any vascular intervention or diagnostic procedure in the preceding year.15 Our study shows that this improved to 33%, ten years later in the Medicare population. Furthermore, although men had a higher risk of 90-day major amputation, we showed that women had similar risk of proceeding directly to major amputation without any trial of revascularization compared to men.

The 90-day mortality rate in our study was significantly high in both sexes, with 10% of women admitted with CLI dying in 90 days. One-year mortality in our study was even higher, reaching 23% in women. This highlights the critical nature of CLI as a diagnosis and the need for mitigation of such high mortality rates. Although 1-year mortality was higher in men in our study, after adjustment for differences in age and comorbidities, there was no difference in adjusted mortality between both sexes.

Our study highlights that the high morbidity and mortality associated with CLI is not just confined to men; women are also at a high risk of CLI and its associated complications. Thus, it is important to refer this high-risk population to vascular centers capable of advanced management such as revascularization. Prior studies have shown that the incidence of PAD is similar among women compared to men.28 While the use of optimal medical therapy such as statins was low overall, use of statins was lower in women compared to men, highlighting missed opportunities for optimal management.

Our study also has several limitations. First, we included only patients ≥65 years old which make our results not generalizable to younger patients with CLI. However, prevalence of CLI in younger patients is significantly lower and majority of CLI burden occurs in patients older than 65 years.29 Second, we had access to data about medications, and outpatient-based institutional procedures in only 5% of the total Medicare population sample. We also utilized only three years of data in our cohort as we aimed to report sex disparities in a contemporary US population. Last, we did not have access to imaging data, such as computed tomography angiogram, and diagnostic angiograms for the study population. Thus, we lacked anatomical details about location and degree of stenosis, and severity of tissue loss.

In conclusion, CLI is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in both sexes. Incidence of CLI is higher than what was reported in the past and majority of patients are managed on outpatient basis. Use of evidence-based guideline-directed therapy, such as statins and revascularization in CLI patients remains suboptimal, and although we found lower probability of these therapies in women, the differences were small.

Supplementary Material

What is known.

Critical limb ischemia (CLI) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Peripheral artery disease and CLI are underrecognized in women compared with men.

What the study adds.

Women suffer from significant morbidity related to CLI, with one out of ten women requiring major amputation within 90 days.

Mortality in men and women with CLI can reach up to 10% within 90 days and 25% in one year.

Women are less likely to be prescribed statin therapy upon CLI diagnosis, and less likely to undergo revascularization at 90 days compared with men.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Dr. Mentias received support from NIH NRSA institutional grant (T32 HL007121) to the Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center. Dr. Sarrazin is supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging (NIA R01AG055663-01), and by the Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

List of abbreviations

- ACC

American college of cardiology

- AHA

American heart association

- CLI

Critical limb ischemia

- CMS

Center for Medicare and Medicaid services

- PAD

Peripheral arterial disease

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors have nothing to disclose.

References:

- 1.Criqui MH and Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1509–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varu VN, Hogg ME and Kibbe MR. Critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:230–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, Barshes NR, Corriere MA, Drachman DE, Fleisher LA, Fowkes FG, Hamburg NM, Kinlay S, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e686–e725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huded CP, Johnson M, Kravitz K, Menon V, Abdallah M, Gullett TC, Hantz S, Ellis SG, Podolsky SR, Meldon SW, et al. 4-Step Protocol for Disparities in STEMI Care and Outcomes in Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2122–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuntz M, Audibert C and Su Z. Persisting disparities between sexes in outcomes of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm hospitalizations. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch AT, Murphy TP, Lovell MB, Twillman G, Treat-Jacobson D, Harwood EM, Mohler ER 3rd, Creager MA, Hobson RW 2nd, Robertson RM, et al. Gaps in public knowledge of peripheral arterial disease: the first national PAD public awareness survey. Circulation. 2007;116:2086–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch AT, Allison MA, Gomes AS, Corriere MA, Duval S, Ershow AG, Hiatt WR, Karas RH, Lovell MB, McDermott MM, et al. A call to action: women and peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1449–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jelani QU, Petrov M, Martinez SC, Holmvang L, Al-Shaibi K and Alasnag M. Peripheral Arterial Disease in Women: an Overview of Risk Factor Profile, Clinical Features, and Outcomes. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2018;20:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AhChong AK, Chiu KM, Wong M and Yip AW. The influence of gender difference on the outcomes of infrainguinal bypass for critical limb ischaemia in Chinese patients. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard JL, Bergan JJ, Singh P, Yonemoto H and Killeen JD. Aortoiliac stent deployment versus surgical reconstruction: analysis of outcome and cost. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:94–101; discussion 101–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnant JG, Cronenwett JL, Walsh DB, Schneider JR, Besso SR and Zwolak RM. Surgical treatment of infrainguinal arterial occlusive disease in women. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17:67–76; discussion 76-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, He Y, Shu C, Zhao J and Dubois L. The effect of gender on outcomes after lower extremity revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65:889–906 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefebvre KM and Chevan J. The persistence of gender and racial disparities in vascular lower extremity amputation: an examination of HCUP-NIS data (2002-2011). Vasc Med. 2015;20:51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal S, Sud K and Shishehbor MH. Nationwide Trends of Hospital Admission and Outcomes Among Critical Limb Ischemia Patients: From 2003-2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1901–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodney PP, Travis LL, Nallamothu BK, Holman K, Suckow B, Henke PK, Lucas FL, Goodman DC, Birkmeyer JD and Fisher ES. Variation in the use of lower extremity vascular procedures for critical limb ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mentias A, Qazi A, McCoy K, Wallace R, Vaughan-Sarrazin M and Girotra S. Trends in Hospitalization, Management, and Clinical Outcomes Among Veterans With Critical Limb Ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:e008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR and Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baser O, Verpillat P, Gabriel S and Wang LJVDM. Prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of critical limb ischemia in the US Medicare population. Vasc Dis Manage. 2013;10:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nehler MR, Duval S, Diao L, Annex BH, Hiatt WR, Rogers K, Zakharyan A and Hirsch AT. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia in an insured national population. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:686–95 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang WT, Hellkamp A, Doll JA, Thomas L, Navar AM, Fonarow GC, Julien HM, Peterson ED and Wang TY. Lipid Testing and Statin Dosing After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e006460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albright KC, Howard VJ, Howard G, Muntner P, Bittner V, Safford MM, Boehme AK, Rhodes JD, Beasley TM, Judd SE, et al. Age and Sex Disparities in Discharge Statin Prescribing in the Stroke Belt: Evidence From the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA and Creager MA. Secondary prevention and mortality in peripheral artery disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999 to 2004. Circulation. 2011;124:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters SAE, Colantonio LD, Zhao H, Bittner V, Dai Y, Farkouh ME, Monda KL, Safford MM, Muntner P and Woodward M. Sex Differences in High-Intensity Statin Use Following Myocardial Infarction in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1729–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Shubina M and Turchin A. Drivers of the Sex Disparity in Statin Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel TR, Dombrovskiy VY, Galinanes EL and Kruse RL. Preoperative statins and limb salvage after lower extremity revascularization in the Medicare population. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schramm K and Rochon PJ. Gender Differences in Peripheral Vascular Disease. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ning H, Ballew SH, Chow EK, Grams ME, Selvin E, Allison M, Criqui M, Coresh J, et al. Lifetime Risk of Lower-Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease Defined by Ankle-Brachial Index in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duff S, Mafilios MS, Bhounsule P and Hasegawa JT. The burden of critical limb ischemia: a review of recent literature. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2019;15:187–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.