Abstract

There are strong cultural norms for how emotions are expressed, yet little is known about cultural variations in preschoolers’ outward displays and regulation of disappointment. Chinese, Japanese, and American preschoolers’ (N=150) displays of emotion to an undesired gift were coded across both social and nonsocial contexts in a disappointing gift paradigm. Generalized estimating equations revealed that, regardless of culture, when children received a disappointing gift, they showed more positive expressions of emotion (“fake smile”) in social contexts (in the presence of unfamiliar and familiar examiners) relative to when they were alone, suggesting that preschool-aged children are able to mask their disappointment with positive displays. However, children’s emotion expressions varied across both cultures and contexts. American children were more positively and negatively expressive than Japanese children, and more negatively expressive than Chinese children. Chinese and Japanese preschoolers verbally reported more negative emotions but showed more neutral expressions than American preschoolers when receiving the disappointing gift. In addition, across different contexts of the task, there were subtle differences in how Chinese and Japanese regulated their emotional expressions, with Chinese children showing similar levels of neutral expressions (e.g., “poker face”) across different contexts in the task. Our findings thus highlight the importance of understanding cultural meanings and practices underlying emotion development in early childhood.

Keywords: Culture, Emotion Expression, Emotion Regulation, Preschoolers

Disappointment occurs universally across cultures and, in general, strong norms exist for how and when it can be expressed (Matsumoto et al., 2008). In the United States, children as young as 3 years old can control their expression of disappointment by displaying less negative and more positive affect (e.g., smiling) when they are in the presence of others (Cole, 1986). Emotion expressions are bounded by display rules, which refer to when and how one might be able to express a particular emotion or set of emotions. According to Ekman and colleagues, (1969), display rules (i.e., masking of emotions) can be seen in different forms, including intensification (e.g., exaggerated smile), minimization (e.g., reduce negative displays even when negative), neutralization (e.g., “poker face”) and/or substitution (e.g., “fake smile”) such that facial displays depend on contextual demands and social norms. Display rules often serve the purpose of preserving politeness and social harmony within a social and cultural context (Matsumoto et al., 2008). Children’s knowledge of display rules and reactions to disappointment are important indicators of social and emotional competence (Liew et al., 2004; McDowell & Parke, 2000). Nonetheless, little is known about cultural variations in preschoolers’ outward displays of disappointment, their tendencies to display disappointment in culturally normative ways, or how these might vary across social vs. non-social contexts (cf. Garrett-Peters & Fox, 2007).

To address these gaps in knowledge, we examined cross-cultural differences in preschoolers’ emotion expression and regulation (i.e., masking) of disappointment in three countries: China, Japan, and the United States (U.S.). We focus on preschoolers because they a) have had more exposure to cultural display rules than infants or younger children (Boyer, 2012; Friedlmeier et al., 2011; Tardif et al., 2009); b) are actively learning and applying such norms to manage their emotions under challenging conditions (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004); and c) have achieved significant social and cognitive developmental milestones in terms of emotion understanding (Denham et al., 2003), theory of mind (Wellman et al., 2001) and the ability to use different emotion regulation strategies (Davis, Levine, Lench, & Quas, 2010).

Emotion regulation and the disappointing gift paradigm

According to Cole and colleagues (2004, p. 320), emotion regulation refers to “changes associated with activated emotions” in response to situational challenges. Changes in children’s facial expressions have been argued to reflect both the direct expression of emotions, as well as attempts to regulate their emotions (Campos et al., 2004). Under this framework, masking of emotional expressions are strategies of emotion regulation and, given the right contexts, may be observed alongside direct expressions of emotions (Cole, 1986; Gross & John, 2003; Hwang & Matsumoto, 2012).

Developmentally, observational assessments of responses to an emotional-eliciting situation via experimental paradigms are often considered to be the “gold standard” for assessing emotion expressions, and serve as a proxy for emotion regulation because, unlike adolescents and adults, young children often lack the cognitive and verbal abilities to self-report their internal emotional experiences (Calkins & Perry, 2016). Displays of emotion have been observed in early childhood through the use of the “disappointing gift” paradigm. In this paradigm, a child is asked to select a preferred gift, waits to receive it, is given the wrong/undesired gift, and is then told there has been a mistake and is allowed to trade for the preferred gift (Cole, 1986; Saarni, 1984). Disappointment typically occurs when people encounter experiences that fail to meet their expectations. Expressions of negative affect such as sadness are often elicited during disappointment and have been observed in this paradigm with American preschoolers (Cole, 1986). However, there is little information on whether this task also elicits disappointment in other cultures and how children from different countries would respond to the situation. Our first goal was to examine whether this task elicits disappointment, expressed as negative affect, among preschoolers in different cultures.

Interestingly, this paradigm involves both social and non-social contexts and could involve either the same, or different interactional partners across various phases of the task (see below and Method for details). Thus, this task has the potential to be a unique tool for identifying culture- and context-specific emotion displays. In the context of this paradigm, to examine direct displays of emotion, children should display positive emotions when choosing the gift, and decreased positive and increased negative displays of emotion once they receive the undesirable (disappointing) gift. They should then return to baseline or display positive emotions once the desirable/preferred gift is given. There are three ways to operationalize masking of disappointment in this paradigm: 1) no change (or even increased) in neutral expressions (e.g., “poker face”) when receiving the disappointing gift compared to baseline (e.g., when they are waiting in the room before receiving the gift); 2) reduced negative facial displays (e.g., “minimize”) in front of the examiner when compared to when they are alone, waiting in the room after receiving the disappointing gift; and/or 3) increased positive displays (e.g., “fake smile”) in front of examiner when compared to when they are alone, waiting in the room after they receive the disappointing gift.

Cultural differences in emotion displays of preschoolers

Chinese and U.S. comparisons

Children from cultures that promote interdependence (i.e., Chinese, Japanese, Asian American) are generally found to be less emotionally expressive than children from cultures that promote individualism (e.g., European American, African American, German - Ahadi, Rothbart, & Ye, 1993; Camras et al., 2006; Friedlmeier & Trommsdorff, 1999; Lewis, Takai-Kawakami, Kawakami, & Sullivan, 2010; Louie et al., 2015; Wilson, Raval, Salvina, Raval, & Panchal, 2012). There is one study conducted by Wang and Barrett (2015) comparing American and Chinese preschoolers’ negative (i.e., anger and sadness) expressions that might provide a hint towards what we would expect from mainland Chinese vs. American children. In this study, an experimenter “realizes” that she had given the child a wrong toy, and then explicitly tells the child not to touch the toy while she leaves the room to exchange the toy. Indeed, the study found that Chinese children displayed fewer negative emotions than American children in this context. However, in their study, the experimenter left the room and the caregiver stayed in the room, which could may have led to a combination of emotions.

In the only cross-cultural study of the disappointment task, Garrett-Peters and Fox (2007) found that Chinese-American children showed fewer overt positive expressions (i.e., direct expressions) than their age-matched European-American counterparts, regardless of age (4-year-olds vs. 7-year-olds). Moreover, Chinese-American children also tended to show more negative emotions when receiving the disappointing gift than European-American children, but only in the older age group (7-year-olds). The authors concluded that displays of more positive (and less negative) expressions found in European-American children may reflect a unique North American phenomenon of masking disappointment with positive expressions. However, this study only examined children’s emotion displays in the social condition (receiving the disappointing gift in front of an experimenter) and did not examine how social vs. non-social (when waiting alone in the room) contexts influence children’s emotion displays. Similarly, the authors did not differentiate various phases surrounding the actual receipt of the disappointing gift (i.e., when children were waiting alone in the room before receiving the gift vs. when waiting alone in the room after receiving the undesired gift or when the experimenter comes back and apologizes to the child and he/she offers to exchange the disappointing gift with the preferred gift). It is therefore unknown whether the observed differences were consistent across contexts.

Context matters, and it matters especially when trying to understand similarities and differences across cultures in how emotions are displayed (Aldao, 2013; Zeman & Garber, 1996). To illustrate the importance of examining context, when doing a frustrating tower-building task, Chinese-American children (aged 5 – 7 years) were found to be less expressive when alone (and aware that they were being observed) but equally expressive as their European American counterparts when in the presence of their mothers (Liu, 2008).

Japanese and U.S. comparisons

Fewer studies have contrasted U.S. and Japanese preschool-age children, particularly with regard to observed emotions. While no study has yet compared U.S. and Japanese children’s reaction to disappointment, one study found that American children showed more positive (direct) displays than Japanese children (temporarily residing in the U.S.) when interacting with their mothers during free play and waiting tasks in the laboratory (Dennis et al., 2002). However, the authors did not examine the child’s behavior alone, nor with an unfamiliar person who may elicit different reactions than a parent or more familiar person. In a more recent observational study, Lewis et al. (2010) compared Japanese nationals temporarily residing in the U.S. and European- and African- American preschoolers in a timed picture-matching task. They found that Japanese children were again less expressive than either group of U.S. children, particularly for expressions of sadness and shame (Lewis et al., 2010).

Are there differences across Asian cultures?

To our knowledge, no investigators have used cross-national samples to compare preschoolers’ emotion displays across different Asian samples. Studying children of immigrants may elucidate the impact of western acculturation and assimilation on emotion expression and is useful for understanding some aspects of cultural differences in emotion expression (Camras et al., 2006). However, the very fact of immigration may involve both selection factors and changes in emotion processing, given that immigrant children may have to “adjust” their emotion expressions based on the display rules of the society to which they have immigrated (Camras et al., 2006; Garrett-Peters & Fox, 2007). One of our central goals, therefore, was to examine cross-cultural similarities and differences in emotion expressions across Asian cultures by comparing Chinese and Japanese preschoolers living in China and Japan, in addition to comparisons between children from Asian countries vs. non-Asian American children residing in the U.S..

Chinese and Japanese cultural values and socialization practices

Both Chinese and Japanese cultures value social harmony and emotional control, yet there may be subtle differences in the underlying cultural meanings and methods to achieving social harmony and emotional control in these two cultures. Even during the preschool years Chinese culture highlights “educational preparation, mastery and self-improvement” (Li, 2005; Parmar et al., 2004) and strong displays of emotion are viewed as signs of immaturity as well as psychological and physiological imbalance (Chen & Swartzman, 2001; Russell & Yik, 1996) Thus, not surprisingly, Chinese and Chinese-American mothers have been shown to actively discourage overt (direct) emotion expression across a number of situations when asked about child-rearing practices and goals (Chen, 2000; Lin & Fu, 1990). Socialization practices also shape Chinese (Taiwanese) preschoolers’ preference for more calm expressions (e.g., calm smiles), whereas European-American preschoolers prefer excited smiles and exciting activities more than their Chinese counterparts (Tsai et al., 2007).

Across development, Japanese cultural practices emphasize relatedness, symbiotic harmony and self-adaptation to accommodate others’ needs (Rothbaum et al., 2000). As with studies of Chinese parents, interviews with mothers of Japanese children have suggested that overt expressions of emotions are discouraged (Denham, Caal, Bassett, Benga, & Geangu, 2004). Japanese parents, however, do not view displays of emotion as signs of imbalance but instead value emotional contentment and feelings of relatedness (Behrens, 2004; Dennis et al., 2002). Moreover, they encourage expressions of sadness to convey the need to depend on others (“amae”; Behrens, 2004). Japanese preschoolers are encouraged to cultivate social connections, especially the development of empathy (omoiyari), as well as obligations and responsibility to others (ki ga tsuku) (Rothbaum et al., 2000; Tobin et al., 2009, p. 240). In contrast to U.S. mothers, Japanese mothers were more likely to designate social insensitivity and uncooperativeness as the most undesirable behavioral characteristics in young children (Olson et al., 2001). Correspondingly, direct observations of preschools in Japan have shown that teachers promoted social connections, the ability to change one’s behavior according to the context (kejime), social-mindedness (shudan-shugi) and empathy (omoiyari) (Hayashi et al., 2009; Tobin et al., 2009, p. 240).

US cultural values and socialization practices

In contrast, for positive emotions U.S. European American parents place greater value on high (enthusiastic and excited), rather than low (calm and peaceful) arousal (Tsai et al., 2007), and encourage children to express their individual needs directly, acknowledging that they may feel differently from others (Tobin et al., 2009, p. 196 – 198). Correspondingly, U.S. Anglo-European parents tend to focus on maintaining and expressing a higher intensity of positive and excited emotion states in their children, and place importance on “talking about” both positive and negative emotion states (Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000; Wang, 2001).

Study Goals and Hypotheses

Our first aim was to examine the validity of the disappointing gift paradigm in eliciting direct expressions of negative emotions across cultures. Specifically, we expected (H1) that most children would report feeling negative and would exhibit more negative and less positive displays when receiving an undesired gift relative to the waiting/expecting phase, indicating that this task could elicit disappointment among preschoolers across all three cultures. To test this hypothesis, we chose to examine children’s emotion displays across contexts that differed only in the receipt of the gift itself. Thus, we compared positive (i.e., Happy and Surprise) and negative (i.e., “Anger, Fear, Disgust, Confusion and Shame”) displays between two phases: when the children were alone before receiving the gift (Phase 2- Child Waiting) vs. when they were alone after receiving the undesired gift (Phase 4: Undesired Gift- alone) in each culture. Given that this task has been used to elicit disappointment among American children (Cole, 1986), we expected that among different negative emotions (e.g., sadness, angry, fear), expressions of sadness would be the most common when children receive an undesired gift, as sadness has been theorized to be an emotion that relates to appraisals of loss or failure to achieve a goal (Frijda, 1986).

Second, we examined cross-cultural differences in emotional displays. We expected (H2) U.S. children to be more expressive of both positive and negative emotions than Chinese and Japanese preschoolers during the disappointment task (Garrett-Peters & Fox, 2007; Lewis et al., 2010).

Third, we examined whether children would mask their disappointment by displaying increased positive displays (“fake smile”) in social situations by examining the change between positive and negative emotions across diffferent contexts of the task. Specifically, we expected (H3) that all children would mask their negative emotions by decreased negative expressions and increased positive expressions during social contexts (in front of both unfamiliar and familiar examiners; Phase 3: Undesired Gift-Unfamiliar Examiner and Phase 5: Undesired Gift-Familiar Examiner) relative to the solitary context (i.e., Phase 4: Undesired Gift-Alone). Nonetheless, we hypothesized (H3) that Japanese (and Chinese) children might show a stronger masking effect with positive displays (“fake smile”) in social situations (i.e., Phase 3: Undesired Gift-Unfamiliar Examiner and Phase 5: Undesired Gift-Familiar Examiner) than U.S. children (H3), such that we were expecting a larger increase in positive displays during the social situations relative to the “alone” condition for the Chinese and Japanese children, although we still expect the American children to show greater expressivity overall. This is because among those with interdependent self-construals (i.e., Chinese and Japanese cultures), positive expressions frequently serve the purpose of maintaining interpersonal harmony rather than reflecting “true” inner feelings of self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Indeed, adult studies show that Asian Americans were more likely to modify their expressions in social situations (e.g., masking with joy) than Caucasian Americans (Hwang & Matsumoto, 2012).

Our last aim was to explore whether there were differences in displays of disappointment, in particular neutral expressions (e.g., “poker face”) across contexts, among children from Chinese and Japanese cultures. Given that few studies have examined neutral expressions and heterogeneity across “Eastern” cultures, this aim is exploratory in nature and thus we did not have specific predictions for these differences.

Method

Participants

Children were recruited primarily from full-time university and community preschools in suburban communities of Beijing, China and Tokyo, Japan, as well as in suburban areas of southeastern Michigan, United States. Institutional Review Board approval as well as signed parental consent and oral child assent was obtained at each location. Children were pre-screened for major health issues and we excluded children who had a history of significant developmental or health concerns (N = 3 for U.S. only) and having Asian ethnic background (N = 7) for the U.S. sample. Table 1 presents demographic data for families from all three cultures (additional details below).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

| Variables | China | Japan | United States | Pairwise Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Child age (months) | 52.34 | 3.29 | 52.98 | 6.56 | 53.27 | 4.64 | n.s. |

| Gender (girls: boys) | 28:31 | 19:27 | 25:20 | n.s. | |||

| Mother age in years | 33.07 | 2.74 | 36.62 | 4.19 | 36.27 | 4.94 | CH < JP, U.S.*** |

| (n=55)1 | (n=44) 1 | ||||||

| Father age in years | 35.75 | 3.35 | 38.49 | 6.61 | 37.16 | 6.93 | n.s |

| (n=55)1 | (n=38) 1 | ||||||

| Mother education [1–7]2 | 5.40 | 1.12 | 5.11 | 1.02 | 6.20 | .82 | CH, JP < U.S.*** |

| (n=55)1 | (n=45) 1 | (n=44) 1 | |||||

| Father education [1–7]2 | 5.64 | 1.16 | 5.72 | .75 | 6.03 | 1.09 | n.s. |

| (n=55)1 | (n=37) 1 | ||||||

| Mother full-time employment | 83% | na | 6.5% | na | 62.8% | na | JP < CH, U.S.*** |

| (n=54)1 | (n=43) 1 | ||||||

| Father full-time employment | 96.3% | na | 100% | na | 86.5% | na | U.S. < JP, CH* |

| (n=54)1 | (n=36) 1 | (n=37) 1 | |||||

| Number of siblings | .04 | .19 | .87 | .69 | 1.05 | .70 | CH < JP < U.S.*** |

| (n=54) 1 | (n=42) 1 | ||||||

| Married (%) | 100% | na | 100% | na | 80.5% | na | U.S. < JP, CH*** |

| (n=54) 1 | (n=41) | ||||||

Note:

p <.05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Ns are different due to missing demographic data

Education 1= 0 to 3 years of schooling, 2= 4 to 6 years of schooling, 3= 7 to 9 years of schooling, 4= 10 to 12 years of schooling, 5= 2–3 year college or technical School, 6= 4 year university, 7= Post-graduate education.

China

In China, 60 children were recruited from three preschools in the Northern, Southern, and Western districts of Beijing and there was a total of 59 children with usable data. Because of China’s single child policy at the time the children were born, only two of the children (a pair of twins) were reported to have siblings. Children were, on average, 52 months old (range: 47– 61 months), mothers were an average of 33 years old (range: 28–44 years), and fathers were an average of 35 years old (range: 29–44 years). Parental education ranged from middle school to graduate-level training for both mothers and fathers.

Japan

In Japan, 55 children were recruited from two preschools in Musashino-shi and Suginami-ku, primarily residential middle-class neighborhoods in northwestern Tokyo with many single-family homes. Usable data were available for 46 children. Children were an average of 53 months old (range: 40–68 months), mothers 36 years old (range: 27–45 years), and fathers 38 years old (range: 27–57 years). Parental education ranged from middle school to graduate-level training for both mothers and fathers. Fewer of the Japanese mothers reported working full-time than in the other countries (see Table 1).

United States

In the U.S., 55 children (usable data for analysis available for 45) were recruited from 15 preschools in and around Ann Arbor, Michigan, a mid-sized urban area. Children were an average of 54 months old (range: 44–63 months); mothers 36 years old (range: 24–48 years), and fathers 37 years old (range: 24–58 years). 73.3% of the children were Caucasian, 13.3% were African American, and 11.1% were mixed race. Note that all Asian- or Asian-American children (N=7) were excluded from the sample. Parental education ranged from high school to graduate-level for both mothers and fathers. Fewer of the U.S. fathers reported working full-time than fathers in other countries, and fewer of the U.S. parents reported being married than those in other countries (see Table 1).

Procedure

Children participated in study activities for a two-hour period on three consecutive days. Activities occurred in the morning, before lunch, or in the afternoon, after naptime. Most children in the U.S. and China were tested at the child’s preschool with some tested at the child-behavior laboratory at each participating university. All of the children in Japan were tested at the child-behavior laboratory at the participating university. On each study day, children began project activities with 30 minutes of quiet play with a research assistant. The children then engaged in a series of tasks with this familiar examiner, including the emotionally challenging “disappointment” task, followed by some quiet time watching an age appropriate “calming” cartoon (e.g., Caillou) and completing individual psychological assessments (e.g., IQ testing). The entire session was videotaped. All procedures were administered in the child’s home language, and examiners were native adult speakers from each country who were trained on each part of the protocol by the study PI. No child reported difficulty understanding the protocol. The disappointment task, which is the focus of the current report, is described below.

Disappointing gift paradigm

The disappointing gift paradigm was used to assess the child’s response to an undesired gift (Cole, et al., 1994; Saarni, 1984). There were multiple task phases of interest. First, a “familiar examiner,” who had introduced the study to the child then spent at least one full two-hour session on a preceding day and at least 30 minutes on the day of the study, presented the child with five objects (e.g., toy car or bubbles, pencil, eraser, bottle cap, broken comb) and asked the child to rate them from most to least desired (Phase 1: Gift Ranking). The “familiar examiner” told the child that she had to go answer a phone call and that a second examiner would return and bring his or her first-choice gift, and then left the room while the child waited for 60 seconds (Phase 2: Child Waiting). Another examiner, who was unfamiliar to the child, then entered the room and gave the child his or her least desired choice, and remained in the room in close proximity to the child, but was instructed to simply read from a book and interact only minimally with the child (Phase 3: Undesired Gift-Unfamiliar Examiner). After 60 seconds, the second examiner left the room and the child remained in the room, alone, with the least desired gift for an additional 60 seconds (Phase 4: Undesired Gift-Alone). The original (“familiar”) examiner then returned to the room, asked the child 1) if he or she had received a gift that he or she wanted (i.e., the “favorite” toy), looked at the gift the child received, and apologized when the child said “no” or did not respond. The familiar examiner also noted that the unfamiliar examiner must have made a mistake and asked how the child felt after receiving the gift and if the unfamiliar examiner knew how he/she felt. The familiar examiner then asked the child whether he or she would like to switch the gift (Phase 5: Undesired Gift-Familiar Examiner) and, if the child agreed to switch, the child was then allowed to switch the least-desired for most-desired gift (Phase 6: Best Gift). Examiner 2 (“unfamiliar” examiner) then entered and apologized to the child as well. The entire task was videotaped for later coding.

Specifically, we are interested in children’s expression of disappointment in three contexts: 1) an unfamiliar-social context in which an unfamiliar examiner gave a child an undesired gift despite he/she had previously ranked as the least preferred gift, and the child had to react to this situation in front of the unfamiliar examiner (Phase 3: Undesired Gift-Unfamiliar Examiner); followed by 2) an alone context in which the child was left alone in the room after receiving the undesired gift (Phase 4: Undesired Gift-Alone); followed by 3) a familiar-social context involving the child’s reunion with the familiar examiner who asked the child if he/she had received his/her favorite gift and apologized when the child said “no” or did not respond (Phase 5: Undesired Gift-Familiar Examiner).

Measures and coding

Child emotion expressions were coded using The Observer behavioral coding software program (Noldus Technologies 2006). This program allowed “time locked” coding of facial expressions on a frame-by-frame basis. Task Phases were documented using start/stop time points in the protocol that were observed from the videos and standardized across all three countries. Each point was based on a discrete key word or event during the task protocol (e.g., examiner places gift on table). All emotions were coded in a mutually exclusive system (i.e., the child could not be coded as being in two different emotion states at once) and emotion states were coded continuously throughout all phases of the Disappointment Task procedure.

Emotion codes were based on Izard’s AFFEX system (Izard, 1994). We chose this coding system because it included many different emotion states, anchored with specific configurations of facial muscles, and we wished to remain open to possibilities that children from each country might express a wide range of emotions. Thus, emotion states coded included Happy/Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear/Anxiety, Disgust, Confusion, Surprise, and Shame. Times when children were not expressing an emotion were coded as Neutral (e.g., brows in resting position, drawn together but neither raised nor lowered). Facial indicators used to assess emotion expressions included mouth movement (e.g., corners of mouth drawn back in a smile vs. lip pout or drawn down in a frown) and eyebrow position (e.g., relaxed vs. inner corners raised, indicating Sadness), as well as behavioral cues such as laughing or crying.

Emotion variables were calculated to represent the proportion of time spent expressing each emotion during each Task Phase. Proportion duration was used in order to compare Task Phases of unequal time length. We also computed a variable to indicate the proportion of time children spent expressing any emotion other than Neutral (Overall Expressivity). Coding was performed by independent coders of U.S., Chinese, and Japanese descent (blind to study hypotheses). In order to ensure uniformity of coding across children and across cultures, all coding took place at the U.S. research site because we had a researcher trained in and highly experienced with the AFFEX coding system across different preschool-aged populations in the U.S. (A. Miller). This researcher (who had extensive experience in facial coding) trained and supervised all of the coders (4 primary and 3 additional coders who helped with some of the videos but whose coding overlapped with one of the primary coder; all coders coded for all emotions) who were required to reach a particular reliability criterion (ICC>.90) on 2 sample tapes from each culture that had been coded by the primary researcher in collaboration with the PI’s from each of the three cultures studied. Ongoing reliability was calculated using an intra-class correlation (ICC) to account for agreement among multiple coders. About 37% of the total sample (N=55) was used to calculate reliability, consisting of 20 Chinese, 12 Japanese, and 23 American children. Weekly coding meetings were held with all coders and confusions and disagreements on codes were discussed amongst the coders of the tape, other coders, and the primary researcher who trained them1. The agreed-upon code was then used as a final code.

Across all three countries only two emotions were expressed greater than 10% of the total time spent during the task (Table 2): Happy (Total ICC=.76) and Sad (Total ICC=.63). The frequencies (in terms of percentage of total time spent) of all other emotions were very low (=< 0.6%; see Table 2), and therefore we were unable to calculate inter-rater reliability. Nonetheless, all coding, regardless of frequency, was discussed in a weekly coders’ meeting that all coders attended so that any discrepancies in coding could be resolved through joint discussion amongst the coders. The frequencies reported and analyzed in this paper are final codes, after resolution of discrepancies.

Table 2.

Mean proportion (percentage) of time spent in emotional display across all task phases

| China | Japan | U.S. | Total | F | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Positive Emotions | ||||||

| Happiness | .126(.187) | .069 (.133) | .163 (.207) | .120 (.183) | 18.26*** | US > CH > JP |

| Surprise | .006 (.017) | .004 (.013) | .007 (.014) | .006 (.015) | 2.90 | n.s |

| Negative Emotions | ||||||

| Sadness | .069 (.154) | .100 (.213) | .194 (.270) | .116 (.213) | 28.88*** | US > CH, JP |

| Anger | .002 (.009) | .002 (.027) | .004 (.016) | .002 (.018) | 1.27 | n.s |

| Fear | .006 (.025) | .005 (.025) | .007 (.023) | .006 (.024) | .53 | n.s |

| Disgust | .001 (.005) | .001 (.009) | .004 (.010) | .002 (.008) | 7.43*** | US > CH, JP |

| Confusion | .003 (.012) | .003 (.014) | .004 (.013) | .004 (.013) | .39 | n.s |

| Shame | .000 (.003) | .000 (.000) | .000 (.003) | .000 (.002) | 1.06 | n.s |

| Neutral | .668 (.286) | .689 (.279) | .482(.294) | .618 (.300) | 42.83*** | CH, JP > US |

p <.05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Children’s verbal and behavioral responses were also coded when the “familiar” examiner returned to the room and asked 1) if the child had received a prize that he or she wanted (i.e., “Yes”, No or Others [e.g., I don’t know or no response]”); 2) how he/she felt after receiving the gift (i.e., “Positive [e.g., good, happy], Negative [e.g., sad, bad, angry], Neutral [e.g., OK, feel nothing] and Others [e.g., I don’t know or no response]”), and 3) if the unfamiliar examiner knew how he/she felt (i.e., “Yes, No, Others [e.g., I don’t know or no response]”).

Preliminary data analysis

We first examined demographic differences across the three countries using ANOVAs and follow-up t-test comparisons with Bonferroni corrections. After that, we examined the mean proportion of time spent expressing each emotion across all phases and compared children’s expression of each emotion across the three countries using ANOVAs and follow-up t-test comparisons. We then examined the relations between facial expressions and the demographic variables using Pearson correlations.

Data analysis for hypotheses

For H1 and H2 regarding differences in emotion expression across cultures and across the different task phases, we conducted Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) analyses (Liang & Zeger, 1986). GEE analyses were chosen because of the ability to draw more robust inferences regarding possible variance-covariance matrixes by choosing working correlation matrixes with better Goodness of Fit (Liang & Zeger, 1986). For the present data, two separate GEE models were performed with Country (U.S., China, Japan), Task Phase (Gift Ranking; Child Waiting; Undesired Gift-Unfamiliar Examiner; Undesired Gift-Alone; Undesired Gift-Familiar Examiner; Best Gift), Gender, and interactions of Country X Task Phase and Country X Gender were entered as predictors to estimate children’s (1) Negative Expressions (summing across Sadness, Anger, Fear, Disgust, Confusion and Shame) and (2) Positive Expressions (summing across Happiness and Surprise) respectively. Follow-up pairwise comparisons were conducted if effects of Task Phase, Country or Task Phase X Country interaction was deemed as significant. We summed across all positive and negative emotions for the GEE analyses because of the low frequency of each emotion and to increase power2. Nonetheless our results were mostly driven by Happiness and Sadness expressions. Verbal responses were compared across cultures using a Chi-square test.

For H3 regarding masking disappointment with positive displays, we conducted a GEE model of Emotion Type (Positive vs Negative) X Social/Alone Context (i.e., Undesired Gift – Alone, Undesired Gift – Unfamiliar Examiner, Undesired Gift – Familiar Examiner) X Country (U.S., China, Japan) X Gender, using maternal age and education as covariates.

In addition to positive and negative emotion displays, we explored the display of neutral expressions across cultures and task phases to better understand whether there were differences in emotional displays of disappointment among children from different “Eastern” cultures. Specifically, we conducted a GEE model to examine Country (U.S., China, Japan), Task Phase (Gift Ranking; Child Waiting; Undesired Gift-Unfamiliar Examiner; Undesired Gift-Alone; Undesired Gift-Familiar Examiner; Best Gift), Gender, and interactions of Country X Task Phase and Country X Gender and Country X Task Phase X Gender were entered as predictors (maternal age and education as covariates) to estimate children’s Neutral expressions. Goodness of fit (as indexed by QIC and QICC) was used to select working correlation matrixes for each model. Results indicated that a compound symmetry covariance structure had the best fit was used for all GEE analyses.

Results

Demographics

Although we chose the samples to be as comparable as possible, there were a number of demographic differences between samples that were reflective of cross-national differences in these countries as a whole. As shown in Table 1, Chinese mothers were younger than Japanese and U.S. mothers, U.S. mothers also had higher levels of education than Japanese and Chinese mothers. A higher percentage of Chinese and U.S. mothers were employed full-time, whereas a higher percentage of Chinese and Japanese (relative to U.S.) fathers were employed full-time. U.S. children had the highest number of siblings, followed by Japanese, and then Chinese children (who were mostly singletons, per China’s one child policy). Higher percentages of Chinese and Japanese than U.S. parents were married. Thus, where relevant, we controlled for maternal age and education, but because marital status did not correlate with any of our measures, we did not consider this in our analyses.

Mean proportion of time spent expressing each emotion across all phases

Table 2 summarizes the mean proportion of time children displayed each emotion across all phases by country. The mean length of the entire task was 6 minutes (SD = 1.5 minutes) and, overall, children spent more time not expressing their emotions than they spent expressing specific emotions, with a cross-cultural average of 61.8% of the time spent in a “neutral” state.

Overall, children displayed Happy expressions for longer durations than Surprised expressions. As shown in Table 2. U.S. displayed Happy expressions for the longest durations, followed by Chinese preschoolers and the least for Japanese preschoolers. For negative emotions, children displayed more Sadness than the other negative expressions of emotion (“Anger, Fear, Disgust, Confusion and Shame”). Chinese and Japanese children expressed less Sadness, overall, than U.S. children. Disgust was also expressed less for Chinese and Japanese children than U.S. children, although the proportion of time spent in Disgust expressions was low across all three samples.

Correlations between displayed emotions and demographic variables

Mother’s age and education were slightly positively associated with overall displays of Sadness (age: r = .09, p < .01, education: r = 15, p < .001) and inversely associated with Neutral expressions (age: r = −.10, p < .01, education: −.10, p < .01). Mother’s age and education were therefore entered as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Cross-cultural differences in direct expressions of emotion

For both Negative (NA) and Positive (PA) expressions, generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses revealed that there were significant main effects of Country (NA: W(2) = 23.03, p < .001; PA: W(2) = 18.25, p < .001), Task Phase (NA: W(5) = 127.46, p < .001; PA: W(5) = 158.32, p < .001) and 2-way interactions of Country X Task Phase (NA: W(10) =20.89, p = .02; PA: W(10) = 24.28, p = .007) after controlling for maternal age and education. No other significant interactions (e.g., gender) were found. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate children’s negative and positive expressions, respectively, across different phases (see method section) of the disappointment task by country, along with the follow-up pairwise comparison results from the GEE models.

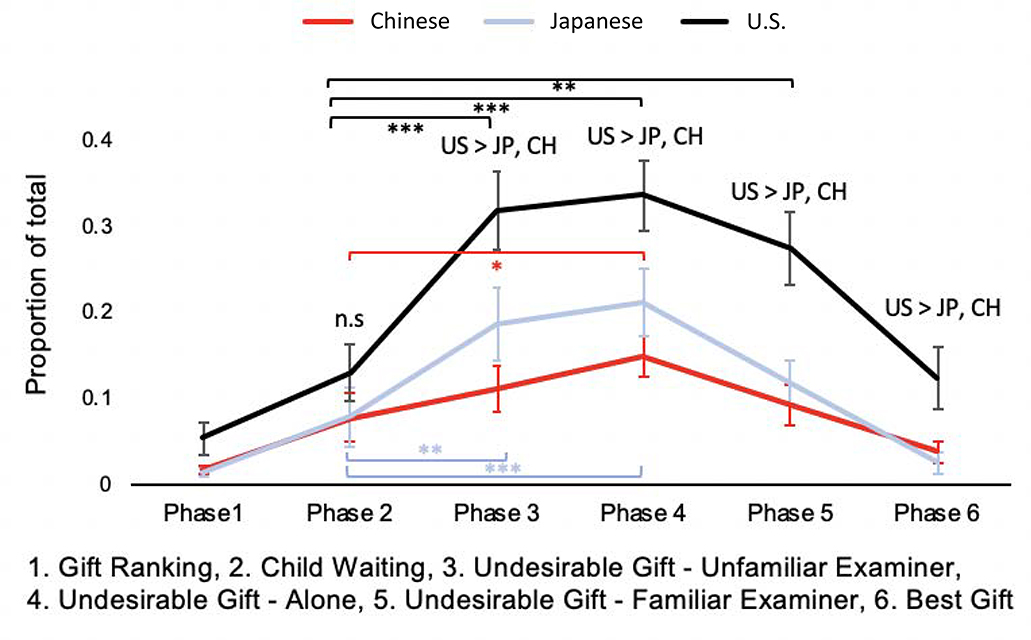

Figure 1.

Children’s negative expressions in different phases of the disappointment task by country

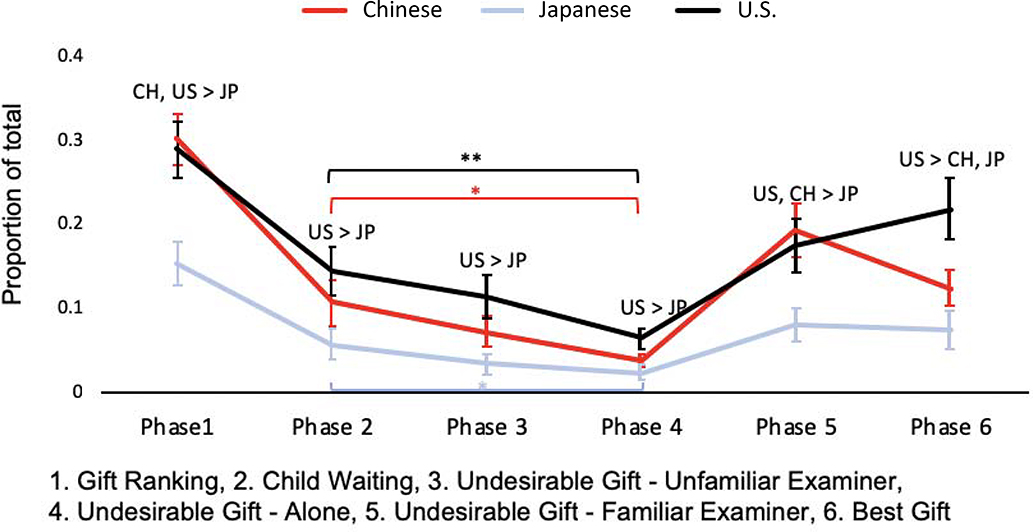

Figure 2.

Children’s positive expressions in different phases of the disappointment task by country

H1. The disappointing gift paradigm would elicit direct negative expressions (i.e., disappointment) across cultures

As shown in Figure 2, follow-up pairwise comparisons from the GEE models revealed that preschoolers from all countries also displayed longer durations of negative expressions and shorter durations of positive expressions after they received the undesired gift and were left alone (Phase 4: Undesired Gift –Alone), compared to when waiting for the gift alone (Phase 2: Child Waiting – Alone; NA of Phase 2 vs. Phase 4 for Chinese: p = .016, Japanese: p < .001 and U.S.: p < .001; PA of Phase 2 vs. Phase 4 for Chinese: p = .007; Japanese: p = .04; U.S.: p = .003), suggesting that children in all countries exhibit change of emotional experiences (i.e., feel disappointed) after receiving the undesired gift.

We also conducted additional analyses to examine the patterns of negative expressions across contexts among children who self-reported feeling negative when asked by the experimenter. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, regardless of culture, children who self-reported feeling negative had a similar pattern of negative expressions relative to the whole sample, suggesting that our overall findings of children’s facial expressions are consistent with children’s subjective reporting of disappointment across cultures.

Second, chi-square analyses of the children’s verbal responses indicated that when the “familiar” examiner returned to the room and asked the child had received his/her favorite gift, the majority (83.3%) of the children indicated that they did not receive the gift that they wanted and there were no cultural differences for this response (“No: Chinese = 83.1%, U.S. = 77.8%, Japanese = 89.1%; Yes = Chinese = 16.9%, U.S. = 17.8%, Japanese = 8.7%”, Chi-square (4) = 4.51, p = .34). Moreover, the majority of the children (66.6%) reported feeling sadness or other negative emotion states (e.g., bad) when asked directly “How do you feel?” Chinese and Japanese preschoolers were more likely to report feeling negative than US children (“Chinese = 76.8%, Japanese = 71.0%, U.S. = 49.0%”), whereas American children were more likely to report feeling neutral (“Chinese = 4.4%, Japanese = 3.5%, U.S. = 17.5%”) or produce other responses such as no response or remark on some other aspect of the study (“Chinese = 0%, Japanese = 9.3%, U.S. = 22.2%”, Chi-square (6) = 142.98, p < .001). No differences were found for positive emotions (“Chinese = 18.8%, Japanese = 16.2%, U.S. = 11.0%”). Taken together, these results suggest that, considering all groups together, most children indicated they felt disappointed/not happy when they received an undesirable toy.

H2. U.S. children would be more expressive than Chinese and Japanese children

Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated that, overall, U.S. preschoolers showed longer durations of negative expressions than Chinese (Phase 3: p < .001; Phase 4: p < .001; Phase 5: p < .001; Phase 6: p = .023) or Japanese (Phase 3, p =.034; Phase 4: p = .027; Phase 5: p < .001; Phase 6: p = .009) preschoolers (Figure 1). U.S. preschoolers also displayed more positive expressions across phases than Japanese (Phase 1: p < .001; Phase 2: p =.01; Phase 3: p =.005; Phase 4: p = .009; Phase 5: p = .015; Phase 6: p <.001; Figure 2) but not Chinese preschoolers (except during the best gift phase; p = .025; Figure 2). Thus, H2 was fully supported for Negative emotions, but only partially supported for Positive emotions.

H3. Chinese and Japanese children would show a larger increase in positive displays (“fake smile”) than American children during social contexts relative to “alone” condition

GEE analyses revealed significant main effects for Emotion type (W(1) = 35.11, p < .001), Country (W(2) = 31.28, p < .001), and significant 2-way interactions of Emotion Type X Country (W(2) = 15.60, p < .001) and Emotion Type X Task Phase (W(2) = 35.31, p < .001) after controlling for maternal age and education. No Country X Emotion Type X Task Phase interaction or other 3- or 4-way interactions were found. Given that there was no Country X Emotion Type X Task Phase interaction, follow-up comparisons of Emotion Type X Task Phase interaction was performed to examine whether considering all groups together children showed changes of positive and negative displays during social contexts with “unfamiliar” and “familiar” examiners (Phases 3 and 5) versus solitary context (Phase 4).

Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated that considering all groups together, children displayed more positive expressions during social contexts with “unfamiliar” (M = .07, SE = .01,) and “familiar” examiners (M = .15, SE = .02) relative to alone when receiving a disappointing gift (M = .04, SE = .01; Phase 3 vs. Phase 4, p = .003; Phase 5 vs. Phase 4, p < .001), indicating an effect of masking with positive affect in social contexts. They also displayed fewer negative expressions in front of the “familiar” examiner (M = .16, SE = .01) relative to alone (M = .23, SE = .02; Phase 5 vs. Phase 4, p < .001) when receiving the disappointing gift. All children also displayed more positive (p < .001) and marginally fewer negative (p = .07) expressions in social situations with the “familiar,” relative to unfamiliar examiner, which also coincided with reuniting with the familiar examiner and receiving the preferred gift. We found no gender or culture differences in change of emotion displays for positive and negative expressions.

Exploratory: Do Chinese and Japanese children show differences in patterns of neutral expression?

GEE analyses revealed significant main effects for Country (W(2) = 37.60, p < .001), Task Phase (W(5) = 31.02, p < .001), and 2-way interactions of Country X Task Phase (W(10) = 53.04, p < .001) after controlling for maternal age and education. No other interaction effect was found. Figure 3 illustrates children’s neutral expressions across different phases (see method section) of the disappointment task by country, along with the follow-up comparison results from the GEE model.

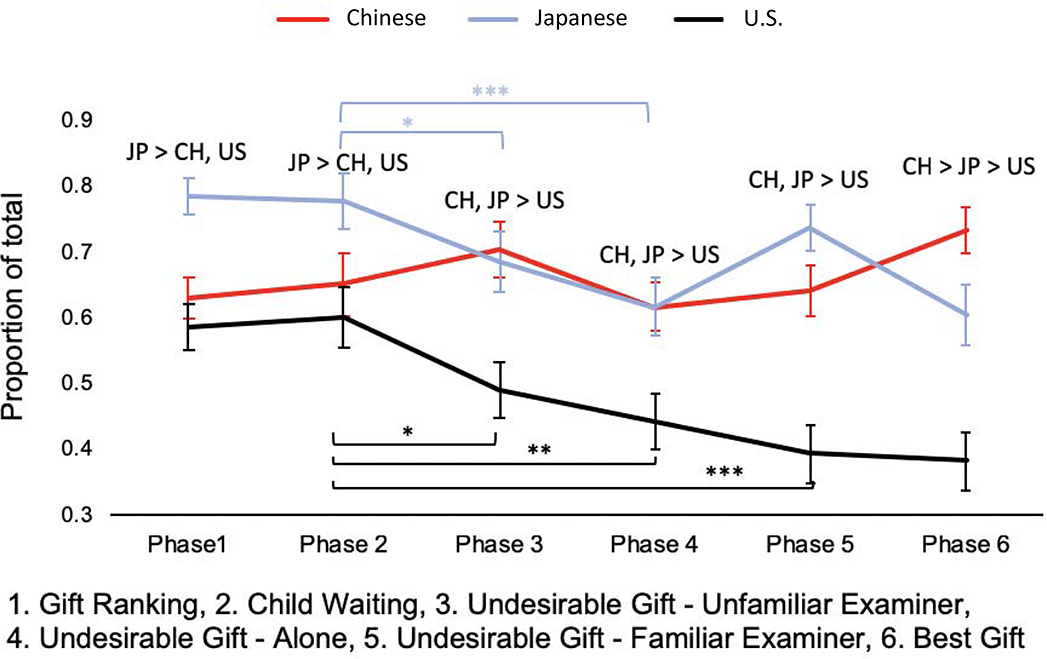

Figure 3.

Children’s neutral expressions in different phases of the disappointment task by country

Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated that across cultures, we observed similar levels of neutral expressions among Japanese and Chinese preschoolers that were significantly higher than those of American preschoolers (Japanese vs. U.S. Phase 3: p = .002; Phase 4: p = .004; Phase 5: p < .001; Phase 6: p < .001; Chinese vs U.S. Phase 3: p < .001; Phase 4: p = .002; Phase 5: p < .001; Phase 6: p < .001) once they received the disappointing gift (Figure 3). Within culture, both American and Japanese children showed a decrease in neutral expressions (Figure 3) once they received the disappointing gift (they were more negatively expressive). However, Chinese children showed no change in neutral expressions across the different phases of the task and no change once the disappointing gift was received (Figure 3). Moreover, verbal analyses indicated that Chinese preschoolers were more likely to report that the “unfamiliar” examiner did not know how they felt (76.4%), followed by U.S. (56.4%) and Japanese preschoolers (45.1%. Chi-square (4) = 72.72, p < .001), when receiving the undesirable gift. This, too, is consistent with the possibility that Chinese children may be more likely to exert emotional control across contexts than others.

Discussion

Our main goal was to compare children’s reactions to disappointment in three cultures: China, Japan, and the U.S. First, we examined the validity of the disappointing gift paradigm in eliciting negative affect among all preschoolers (H1). Second, we examined cross-cultural differences in emotional displays (H2). Third, we examined whether children would mask their negative emotions with positive displays (“fake smile”) in social situations (H3). Finally, we explored whether we might find cultural differences in more “neutral” forms of masking, particularly in the disappointment phases of the task.

Validation of task paradigm across cultures

As expected, most children reported that they received an undesirable prize and felt negative, indicating that the disappointing gift paradigm can elicit negative emotions among preschoolers living in China, Japan and the United States (U.S.). Supporting this, preschoolers across all three cultures displayed higher negative (mostly sadness) and lower positive expressions after they received the undesired gift and were left alone compared to when waiting for the gift alone (Figures 1 and 2). High cross-cultural consistency on the expressions of sadness relative to other type of negative expressions (e.g., anger) when reacting to this disappointing gift paradigm also suggests that preschoolers across cultures appraised this situation similarly as a loss or failure to achieve a goal, which in our context involved receiving an undesirable gift when they expected to receive the gift they had just ranked as their “favorite.” However, we do not know whether children’s expressions of sadness (or anger) as a signal for caregivers’ support are consistent across cultures, or whether the social functions of negative emotional displays vary across contexts (e.g., in front of strangers) and cultures in young children.

Cross-cultural comparisons of emotional displays

We had hypothesized (H2) that American children would show greater emotion expression than Chinese and Japanese children, respectively. Our findings partially supported this hypothesis, with some interesting differences across task phases and cultures. Overall, the American children were more expressive than others. However, when compared to the Chinese children, the American children displayed more negative expressions only, whereas they displayed both more negative and more positive expressions in almost every task phase than the Japanese children. Much to our surprise, the Chinese children displayed almost identical amounts of positive expressions as the American children and displayed more positive expressions than the Japanese children, except during the final phase of the task when children received their most preferred gift.

The overall differences between preschoolers from the U.S. and the two Asian countries in the display of negative emotional expressions may be attributed to differences in the socialization of emotion expression across cultures (Friedlmeier et al., 2011). In the U.S., making one’s needs known and expressing one’s true emotions, whether positive or negative, is highly valued. Dampening one’s negative emotions is considered less important in these cultures if such dampening is in conflict with the attainment of individual social and psychological goals (Triandis, 2001). In contrast, in more group-oriented (i.e., Chinese and Japanese) cultures, control of negative emotions is highly valued, because expressing strong negative emotions does not bode well for mutual support and group cohesiveness (Chen, 2000), although that may be changing as a consequence of globalization (Chen et al., 2005). Thus, it is not surprising that Chinese and Japanese preschoolers, who are actively being socialized into the social and emotional norms of their cultures, displayed significantly less sadness and other negative expressions than American children in almost every phase of the task.

Notably, American children also exhibited higher positive and less neutral emotions than both Japanese and Chinese children in the positive phase of this task (i.e., when children received their most preferred gift). This is consistent with prior adult studies suggesting that Westerners generally want to savor positive emotions, whereas Easterners tend to dampen their positive experiences (Miyamoto & Ma, 2011).

Masking of disappointment with positive displays across cultures

We had hypothesized (H3) that all children would show signs of masking their disappointment by displaying fewer negative emotions and more positive emotions during social (i.e., with familiar and unfamiliar examiners) relative to alone contexts. We also hypothesized (H3) that Japanese and Chinese children might show stronger masking effects during social situations, given their cultural norms of minimizing one’s expression of emotions as it relates to the comfort of the social other (Lebra, 1976; Shimizu & LeVine, 2001). Our findings partially supported this hypothesis. Specifically, preschoolers showed signs of masking their disappointment by displaying more positive emotions during social, relative to alone, situations across all cultures. While studies of Asian American adults found that they were more likely to mask their expressions with positive displays when compared to European Americans (Hwang & Matsumoto, 2012), we did not find this cultural difference in our preschool-age sample. It is possible that children at this age are still learning their emotion display rules, and have not fully interalized cultural norms for masking disappointment. However, there were differences in how much “neutral” expressions were displayed such that both Japanese and Chinese preschoolers displayed higher neutral expressions than American preschoolers, particularly after receiving the disappointing gift (Figure 3). This may suggest that there are indeed cross-cultural differences in masking at this age, but they are difficult to tease apart from overall differences in expressiveness. Further research is needed to identify the ways in which children develop culturally specific patterns of emotional masking.

It is noteworthy that prior studies found that compared with children in the U.S., 6-year-old Chinese children showed greater expressivity towards challenging authority (Wang & Leichtman 2000). It is possible that our “unfamiliar experimenter” context that involves the examiner presenting an undesired gift to the child would elicit higher masking of negative emotions in this context (relative to alone) for Chinese (and Japanese) preschoolers (relative to American children) simply because the experimenter is considered to be an authority figure. In this situation, the expression of negative emotions could be an indication of challenging the authority figure. However, our study did not seem to support this hypothesis given that we found no Country X Emotion Type X Task Phase interaction, and that across cultures children showed higher positive (and similar levels of negative) expressions in front of the unfamiliar examiner relative to the alone context. Moreover, Chinese children showed similar levels of neutral expressions across different (social versus solitary) contexts in this task. We also found that American children consistently showed higher negative expressions across contexts when compared to Chinese and Japanese children. Nonetheless, it remains possible that across cultures, children showed higher positive displays towards unfamiliar (and familiar) examiners because he or she was seen as an authority figure.

Emotion displays among “Eastern” cultures

Both American and Japanese children showed a decrease in neutral expressions after they received the disappointing gift, but this effect was not found in Chinese children who showed similar levels of neutral expressions across different contexts (Figure 3). This is intriguing because most Chinese children (78.6%) reported feeling sad or other negative emotions when asked. These findings may suggest that Chinese children tend to exert high levels of emotional control of negative experiences, which may reflect cultural norms and socialization (Chen, 2000; Russell & Yik, 1996; Tsai, 2007). Alternatively, the observed findings may also be attributed to Chinese preschoolers being less reactive to this situation and/or experiencing less intense negative emotions (or a combination of all these reasons). Future studies that incorporate a multi-level approach incorporating both behavioral, physiological (e.g., cortisol, heart rate etc.) and subjective measures would be better able to explain these findings.

Japanese preschoolers were more likely to report that the unfamiliar examiner knew how they felt when compared to their Chinese and American counterparts. Thus, it is possible that Japanese children thought that they did not adequately “hide” their emotions in front of the examiner, and/or that Japanese adults would be able to infer the child’s emotion from the context such that the child would not need to tell or show the adult how they feel. Further study is needed to examine these questions, but it is an intriguing mismatch that is suggestive of cultural explanations.

Our findings highlight the critical role of examining cultural meanings beyond the broad distinctions of cultural orientations (e.g., independent vs interdependent self-construals) underlying socialization, customs and practices (Super & Harkness, 1999) to understand variations of display behaviors in preschoolers.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine Japanese preschoolers’ responses to the disappointment task, and the only one to compare responses across Chinese, Japanese, and U.S. preschoolers, or to examine emotion expressions across multiple phases of this task across cultures. Yet, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, our conclusions are limited by a relatively small sample size, which allowed for comparisons across cultures, but not extensive explorations of associations between variables within and across cultures. Relatedly, there are heterogeneous values and socialization styles within cultures, and thus our findings may not be representative of sub-groups within each culture. Although it is beyond the scope of our study, examining individual and sub-group heterogeneity of emotion expression and factors underlying these variations within cultures is an important direction for future research. Second, we examined children with different experiential histories at a single point in time and were unable to make inferences about how culture shapes emotion expressions. Third, our study only includes measures of facial coding, overt behavioral expressions that indicated emotions (e.g., crying and laughing) and speech coding after children received the gift, but did not incorporate coding of specific gestures because not all of our coders were trained to differentiate unique behavioral expressions of the country they were coding and to do so would have resulted in culturally-specific coding systems, which would go beyond the scope of the current study. For example, it is possible that behavioral expressions such as body movements could provide unique insight into cultural variations of how children responded to our disappointment gift paradigm. Therefore, further studies that incorporate non-facial and culturally-specific expressions would be important not just to corroborate the findings from our study, but to also to understand how different aspects of emotion display and expression might be related to each other, within and across cultures. Fourth, our study only assesses the presence or absence of children’s emotional displays at a given moment. Although studies have demonstrated associations between spontaneous emotion expressions and self-reports of internal emotion experience (Mauss et al., 2005), it is possible that the outward displays we observe do not reflect their internal experience of emotions and/or that the internal experiences continue beyond the moments in which we measured the external displays. Fifth, due to the fact that we only examined children’s reactions to disappointment, we observed very low frequencies of basic emotions other than sadness and happiness. Developmentally, prototypical facial displays of discreet negative emotions (i.e., sadness, anger, fear) are not observed in infancy and anger and sadness displays are often difficult to differentiate even in older children (Camras, Castro, Halberstadt, & Shuster, 2017). While we found cross-cultural consistency of sadness expressions, it remains possible that other specific negative discrete expressions (shame, disgust, guilt etc.) may not be observed until later in development. In future research, paradigms designed to elicit other emotions (e.g., toy removal to elicit anger) are needed to understand the cultural and developmental influences on specific positive or negative expressions. Nonetheless, our study offers new insight that the disappointment paradigm, which is widely used in developmental research in Western cultures, can be adapted to assess children’s expressions of sadness and happiness in other cultures, but is less effective at eliciting expressions of other emotions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we assessed how likely young children are to show their emotions to an outside observer, as well as to display them in the absence of another person with unique consideration of the role of culture in this process. Our findings highlight how cultural values at the macro level can be manifested in short glimpses of behavior. Our findings also suggested unique situational as well as cultural influences on children’s ability to regulate their emotions, underscoring the need to consider culture-in-context. Finally, our study takes an important step in the direction toward incorporating cross-cultural perspectives into the study of developmental processes (Nielsen & Haun, 2016), which has strong implications for understanding cultural variations in social-emotional development (Olson et al., 2019).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

American preschoolers were more expressive than Japanese and Chinese children

Preschoolers across cultures mask their disappointment in social contexts

There are differences in emotion displays among “Eastern” cultures

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSF grant #HSD 0527475 to T.Tardif, NIH grant # K01-MH066139 to A. Miller, and JSPS KAKENHI grant #17530485, #20330139 to H. Hirabayashi.

Footnotes

The primary researcher did not impose a final decision but walked through the specifics of the potential codes that could be used for a particular expression and asked the disagreeing coders to explain why they chose their code and not the other.

Prior to combining all positive and negative emotions, we ran separate GEE models with only Happiness and Sadness without combining across other positive/negative emotions and the results were similar.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahadi SA, Rothbart MK, & Ye R (1993). Children’s temperament in the US and China: Similarities and differences. European Journal of Personality, 7(5), 359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A (2013). The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(2), 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens KY (2004). A multifaceted view of the concept of amae: Reconsidering the indigenous Japanese concept of relatedness. Human Development, 47(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer W (2012). Cultural factors influencing preschoolers’ acquisition of self-regulation and emotion regulation. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 26(2), 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, & Perry NB (2016). The development of emotion regulation: Implications for child adjustment. Developmental Psychopathology, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Frankel CB, & Camras L (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75(2), 377–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camras LA, Castro VL, Halberstadt AG, & Shuster MM (2017). Facial expressions in children are rarely prototypical. The Psychology of Facial Expressions, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Camras Linda A., Bakeman R, Chen Y., Norris K., & Cain TR (2006). Culture, ethnicity, and children’s facial expressions: A study of European American, mainland Chinese, Chinese American, and adopted Chinese girls. Emotion, 6(1), 103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X (2000). Social and emotional development in Chinese children and adolescents: A contextual cross-cultural perspective. Advances in Psychology Research, 1, 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Cen G, Li D, & He Y (2005). Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: The imprint of historical time. Child Development, 76(1), 182–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Swartzman LC (2001). Health beliefs and experiences in Asian cultures Handbook of Cultural Health Psychology, 389–410. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM (1986). Children’s spontaneous control of facial expression. Child Development, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, & Dennis TA (2004). Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development, 317–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EL, Levine LJ, Lench HC, & Quas JA (2010). Metacognitive emotion regulation: Children’s awareness that changing thoughts and goals can alleviate negative emotions. Emotion, 10(4), 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Caal S, Bassett HH, Benga O, & Geangu E (2004). Listening to parents: Cultural variations in the meaning of emotions and emotion socialization. Cogn. Brain Behav, 8, 321–350. [Google Scholar]

- Denham Susanne A., Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach–Major S, & Queenan P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74(1), 238–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis TA, Cole PM, Zahn–Waxler C, & Mizuta I (2002). Self in context: Autonomy and relatedness in Japanese and US mother–preschooler dyads. Child Development, 73(6), 1803–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Sorenson ER, & Friesen WV (1969). Pan-cultural elements in facial displays of emotion. Science, 164(3875), 86–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlmeier W, Corapci F, & Cole PM (2011). Emotion socialization in cross-cultural perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(7), 410–427. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlmeier W, & Trommsdorff G (1999). Emotion regulation in early childhood: A cross-cultural comparison between German and Japanese toddlers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(6), 684–711. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH (1986). The emotions Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Peters PT, & Fox NA (2007). Cross-cultural differences in children’s emotional reactions to a disappointing situation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(2), 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A, Karasawa M, & Tobin J (2009). The Japanese preschool’s pedagogy of feeling: Cultural strategies for supporting young children’s emotional development. Ethos, 37(1), 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HS, & Matsumoto D (2012). Ethnic differences in display rules are mediated by perceived relationship commitment. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 3(4), 254. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE (1994). Innate and universal facial expressions: Evidence from developmental and cross-cultural research. http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1994-24321-001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kitayama S, Markus HR, & Kurokawa M (2000). Culture, emotion, and well-being: Good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition & Emotion, 14(1), 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lebra TS (1976). Japanese patterns of behaviour. University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Takai-Kawakami K, Kawakami K, & Sullivan MW (2010). Cultural differences in emotional responses to success and failure. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(1), 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J (2005). Mind or virtue: Western and Chinese beliefs about learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Liang K-Y, & Zeger SL (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liew J, Eisenberg N, & Reiser M (2004). Preschoolers’ effortful control and negative emotionality, immediate reactions to disappointment, and quality of social functioning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 89(4), 298–319. 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-YC, & Fu VR (1990). A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. Child Development, 61(2), 429–433. [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH-J (2008). The emotion experience of Chinese American and European American children [PhD Thesis]. University of Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- Louie JY, Wang S, Fung J, & Lau A (2015). Children’s emotional expressivity and teacher perceptions of social competence: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(6), 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, & Nakagawa S (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Levenson RW, McCarter L, Wilhelm FH, & Gross JJ (2005). The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion, 5(2), 175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell DJ, & Parke RD (2000). Differential knowledge of display rules for positive and negative emotions: Influences from parents, influences on peers. Social Development, 9(4), 415–432. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, & Ma X (2011). Dampening or savoring positive emotions: A dialectical cultural script guides emotion regulation. Emotion, 11(6), 1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, & Haun D (2016). Why developmental psychology is incomplete without comparative and cross-cultural perspectives. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 371(1686), 20150071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Kashiwagi K, & Crystal D (2001). Concepts of adaptive and maladaptive child behavior: A comparison of US and Japanese mothers of preschool-age children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(1), 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Lansford JE, Evans EM, Blumstein KP, & Ip KI (2019). Parents’ Ethnotheories of Maladaptive Behavior in Young Children. Child Development Perspectives [Google Scholar]

- Parmar P, Harkness S, & Super C (2004). Asian and Euro-American parents’ ethnotheories of play and learning: Effects on preschool children’s home routines and school behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(2), 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz J, Pott M, Miyake K, & Morelli G (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, & Yik MSM (1996). Emotion among the Chinese In Bond MH (Ed.), The Handbook of Chinese Psychology (p. 166–188). Oxford University [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C (1984). An observational study of children’s attempts to monitor their expressive behavior. Child Development, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H, & LeVine RA (2001). Japanese frames of mind: Cultural perspectives on human development. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Super CM, & Harkness S (1999). The environment as culture in developmental research. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif T, Wang L, & Olson SL (2009). Culture and the development of regulatory competence: Chinese-US comparisons. Biopsychosocial Regulatory Processes in the Development of Childhood Behavioral Problems, 258–289. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Knutson B, & Fung HH (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(2), 288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Louie JY, Chen EE, & Uchida Y (2007). Learning what feelings to desire: Socialization of ideal affect through children’s storybooks. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(1), 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q (2001). “Did you have fun?”: American and Chinese mother–child conversations about shared emotional experiences. Cognitive Development, 16(2), 693–715. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, & Barrett KC (2015). Differences between American and Chinese preschoolers in emotional responses to resistance to temptation and mishap contexts. Motivation and Emotion, 39(3), 420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, & Leichtman MD (2000). Same beginnings, different stories: A comparison of American and Chinese children’s narratives. Child development, 71(5), 1329–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM, Cross D, & Watson J (2001). Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 655–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SL, Raval VV, Salvina J, Raval PH, & Panchal IN (2012). Emotional expression and control in school-age children in India and the United States. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly (1982-), 50–76. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.