Abstract

The commensal microbiota is a recognized enhancer of arterial thrombus growth. While several studies have demonstrated the prothrombotic role of the gut microbiota, the molecular mechanisms promoting arterial thrombus growth are still under debate. Here, we demonstrate that germ-free (GF) mice, which from birth lack colonization with a gut microbiota, show diminished static deposition of washed platelets to type I collagen compared with their conventionally raised (CONV-R) counterparts. Flow cytometry experiments revealed that platelets from GF mice show diminished activation of the integrin αIIbβ3 (glycoprotein IIbIIIa) when activated by the platelet agonist adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Furthermore, washed platelets from Toll-like receptor-2 (Tlr2)-deficient mice likewise showed impaired static deposition to the subendothelial matrix component type I collagen compared with wild-type (WT) controls, a process that was unaffected by GPIbα-blockade but influenced by von Willebrand factor (VWF) plasma levels. Collectively, our results indicate that microbiota-triggered steady-state activation of innate immune pathways via TLR2 enhances platelet deposition to subendothelial matrix molecules. Our results link host colonization status with the ADP-triggered activation of integrin αIIbβ3, a pathway promoting platelet deposition to the growing thrombus.

Keywords: microbiota, germ-free, von Willebrand factor, Toll-like receptor-2, platelets, αIIbβ3

1. Introduction

While genetic predisposition to arterial thrombosis is increasingly understood [1], the knowledge of environmental modifiers contributing to cardiovascular disease (CVD) progression and arterial thrombosis remains elusive [2]. One of the environmental factors affecting arterial thrombus growth is the commensal microbiota. The microbiota, a highly diverse ecosystem consisting of trillions of microbes colonizing our body surfaces, is established at birth [3,4]. These microbial communities interact dynamically with their host, forming a metaorganism, thus influencing host physiology [5,6,7]. In recent years, microbial sequencing studies on patient cohorts, as well as experimental work on gnotobiotic mouse models has linked the gut microbiota to the development of CVD and arterial thrombosis [8,9,10].

Numerous metabolic pathways are influenced by the microbiota, dependent on nutrition [11,12]. However, in addition to signaling-active microbiota-derived metabolites that are largely determined by the availability of nutrients, the microbiota provides a broad variety of microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) that steadily trigger the basal activation of pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [13,14]. These pro-inflammatory signals are not restricted to the surface of the intestinal epithelium, but remain active and can be detected at varying levels in the bloodstream, dependent on gut barrier function [15,16,17]. Remarkably, MAMPs derived from the gut microbiota can signal to distant vascular beds, influencing both endothelial cell function and platelet responses [18,19,20]. In the vasculature, remote signaling of microbial patterns is mediated by TLRs and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors [15,21], impacting on hematopoiesis but also affecting the development of vascular disease states such as atherosclerosis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and arterial thrombosis [22,23,24].

Recent research on the vascular physiology of germ-free (GF) mouse models has linked colonization with commensal microbiota to CVD development and its most severe complication, arterial thrombosis [2,9,25,26,27,28]. In spite of the recognized role of the microbiota in enhancing platelet adhesion to subendothelial matrix components and arterial thrombus formation [9,29], so far little is known on the precise molecular mechanisms that are influenced by the presence of gut microbiota and that support arterial thrombus growth. Primary adhesion of platelets to subendothelial collagen is mediated via the interaction of the GPIb-V-IX receptor complex with exposed von Willebrand factor (VWF). Integrin α2β1 and subsequent GPVI signaling stabilizes the interaction of platelets with collagen type I at static conditions [30,31]. Thereafter, thrombus growth is predominantly supported by the abundantly expressed platelet integrin αIIbβ3 (the GPIIbIIIa receptor) after its activation [32]. In addition to the recognized role in the formation of inter-platelet fibrinogen-bridges, the platelet integrin αIIbβ3 can also interact with VWF to mediate stable adhesion to the subendothelium through binding to the VWF RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp)-motif in a Ca2+-dependent manner [33]. This Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) binding motif is situated in the C-terminal region of VWF, mediating its binding to the activated platelet integrin αIIbβ3 [34]. In static adhesion experiments, it was demonstrated that platelets bind to immobilized VWF and fibrinogen [35]. While inhibition of the platelet-activating pathways with prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and forskolin prevented static platelet deposition to VWF, it did not block deposition to fibrinogen. Therefore, it is clear that pre-activation is an essential requirement for the integrin αIIbβ3-mediated VWF-platelet interaction under static conditions.

Our recent investigations on germ-free (GF) mouse models have revealed a microbiota-triggered Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR2)-mediated pathway that promotes hepatic VWF synthesis, thus supporting integrin αIIbβ3-dependent platelet deposition onto laminin matrices [19]. Furthermore, we demonstrated in the hyperlipidemic low-density lipoprotein-receptor (Ldlr)-deficient mouse model that the platelets of GF Ldlr-deficient mice, which were kept on an autoclaved standard laboratory diet, had reduced activation of the integrin αIIbβ3 when adhering to a collagen type III matrix relative to conventionally raised (CONV-R) Ldlr-deficient controls. These results, obtained ex vivo in a standardized flow chamber model, suggest a diminished adhesion-dependent activation of GF mouse platelets [27]. This observation is in line with previous work indicating that GF mice have increased bleeding times associated with a reduced collagen-stimulated platelet activation [29]. However, it is unresolved whether the commensal microbiota affects the amplifying pathway triggered upon tethering of platelets to subendothelial matrix, e.g., via the ADP-stimulated platelet activation.

To gain mechanistic insights on the microbiota’s role in promoting platelet deposition to subendothelial matrix components, we here studied GF and Tlr2-global-knockout mouse models. Comparing GF with CONV-R mice as well as WT with Tlr2-deficient mice, we analyzed static platelet deposition to type I collagen coatings and ADP-induced activation of αIIbβ3. We found that the platelets from GF mice show reduced deposition to type I collagen coatings, paralleled by impaired ADP-stimulated activation of the integrin αIIbβ3. Similar to the adhesion of GF mouse platelets, platelets from Tlr2-deficient mice that lack innate immune signaling via TLR2 also showed reduced deposition to type I collagen. The observed platelet deposition phenotype was strongly dependent on the plasma source as pre-incubation with WT plasma rescued diminished platelet deposition to type I collagen.

2. Results

2.1. Platelets from Germ-Free Mice Show Reduced Deposition to Type I Collagen and Diminished ADP-Induced αIIbβ3 Integrin Activation

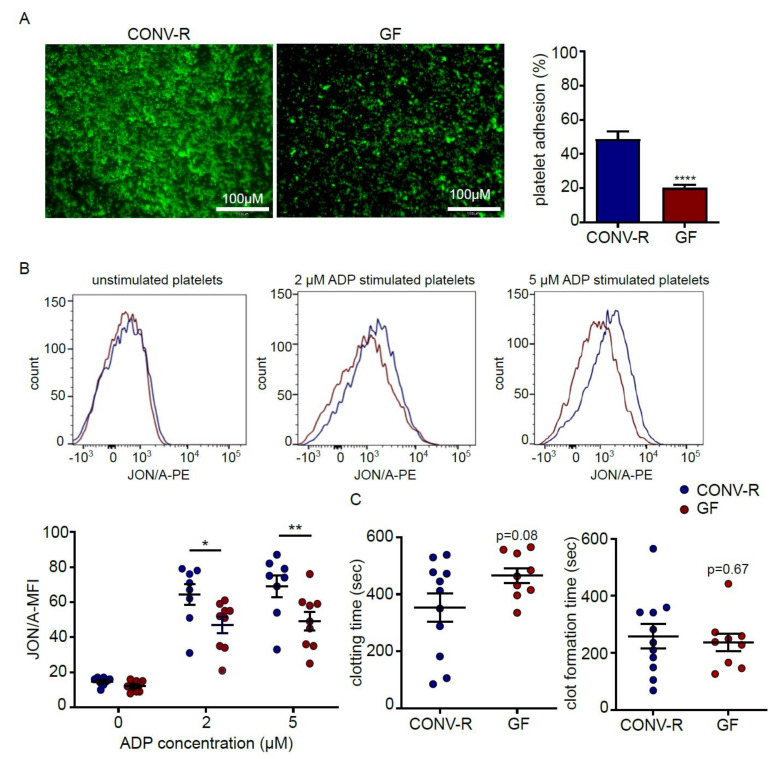

Type I collagen is a major component of the subendothelial matrix that is exposed after vascular injury (e.g., during atherosclerotic plaque rupture). Here we analyzed the deposition of isolated washed platelets from CONV-R and GF mice onto type I collagen coatings ex vivo. In line with our previous work, demonstrating reduced platelet deposition to the subendothelial matrix constituent laminin [19], washed platelets from GF mice showed an approximate 50% reduction in platelet deposition onto type I collagen matrices (Figure 1A). Hence, platelets from GF mice are characterized by an impaired deposition to subendothelial matrix components [19,29].

Figure 1.

Reduced deposition of germ-free (GF) mouse platelets to type I collagen coatings is paralleled by diminished ADP-triggered integrin αIIbβ3 activation. (A) Representative images and bar graph of platelet deposition from GF (red) and conventionally raised (CONV-R) (blue) mice on type I collagen-coated slides (n = 13) (B) Flow cytometry analysis of platelets from GF (red) vs CONV-R (blue) mice stimulated with 0, 2 or 5 μM ADP and stained with the phytoerythrin (PE)-conjugated JON/A antibody, recognizing activated integrin αIIbβ3; representative histograms and MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) quantifications (n = 9, 8). (C) Comparative analysis of clotting time (CT) and clot formation time (CFT) in collagen-stimulated whole blood (8 µg/mL) from GF and CONV-R mice (n = 9, 11). All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Student’s t-test and two-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

Because thrombus growth is primarily dependent on intact integrin αIIbβ3 function [32], we hypothesized that the observed reduced deposition of GF mouse platelets to type I collagen coatings could be due to impaired adhesion-induced integrin αIIbβ3 activation that, in addition to other agonists, is efficiently promoted by the platelet agonist ADP, secreted from platelet-dense granules. Therefore, we stimulated isolated platelets from GF and CONV-R mice with different ADP concentrations. Flow cytometry analyses revealed that upon ADP stimulation, platelets isolated from GF mice were less reactive in terms of integrin αIIbβ3 activation (Figure 1B).

To test whether differences in the collagen-induced activation of the clotting system in whole blood could be involved in the diminished deposition of GF mouse platelets, we analyzed citrate-anticoagulated whole blood that was stimulated with type I collagen by thrombelastometry. With this method, we found a trend towards a prolonged clotting time (CT) in GF type I collagen-stimulated whole blood, indicating an impaired coagulation response (Figure 1C, left panel). In contrast, clot formation time (CFT) was similar in GF and CONV-R citrate-anticoagulated mouse blood (Figure 1C, right panel), indicating that platelet function between GF and CONV-R mice was comparable in this ex-vivo assay.

Collectively, our results identified a diminished ADP-induced activation of the platelet integrin αIIbβ3 at GF housing conditions, a major platelet signaling loop that could explain the reduced static platelet deposition to type I collagen, observed with GF mouse platelets.

2.2. Deficiency in TLR2 Results in Impaired VWF-Mediated Platelet Deposition to Type I Collagen

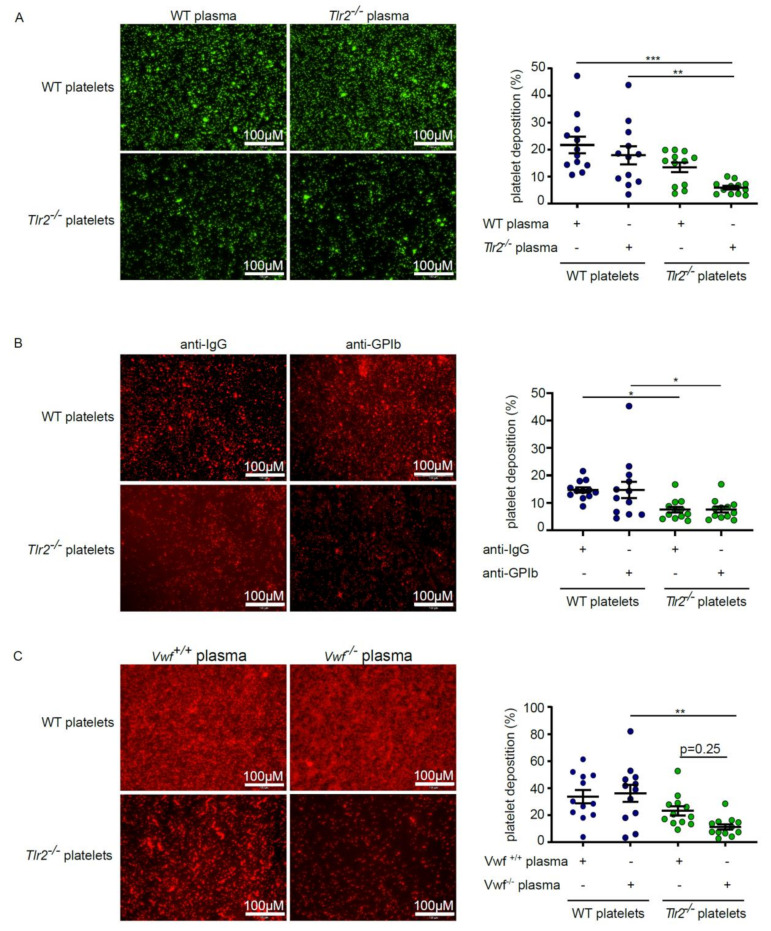

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern-recognition receptors involved in innate immunity that, after recognition of highly conserved molecular determinants, promote vascular thrombosis [36]. In previous work, we showed that microbiota-stimulated TLR2 signaling on the hepatic endothelium supports VWF-mediated platelet deposition to laminin, dependent on platelet integrin αIIbβ3 binding [19]. To test whether plasma from Tlr2-deficient mice likewise suppresses platelet deposition to type I collagen, we incubated platelets from Tlr2-deficient mice and wild type (WT) controls, resuspended in either WT or Tlr2-deficient plasma on type I collagen coatings. Similar to platelet deposition to laminin coatings [19], WT platelets showed a robust deposition, no matter if they were pre-incubated with WT plasma or plasma from Tlr2-deficient mice (Figure 2A). In contrast, Tlr2-deficient platelets displayed defective platelet deposition to type I collagen, which was partially rescued when pre-incubated with the plasma from WT mice (Figure 2A). Our results confirm that integrin αIIbβ3 activation is a major factor in static platelet deposition [19], but they also imply a plasma-dependent role for TLR2 signaling in modulating pro-adhesive platelet function.

Figure 2.

Washed platelets from Tlr2-deficient mice (Tlr2-/-) show a reduced von Willebrand factor (VWF)-dependent deposition onto type I collagen matrix. (A) Representative images and dot plot of platelet deposition (DCF-stained) from wild-type (WT) platelets incubated with plasma isolated from WT (blue) or Tlr2−/− (green) mice, and similarly Tlr2−/− platelets incubated with either plasma isolated from WT or Tlr2−/− mice on collagen coated slides (n = 12) (B) Blockade of GPIb-function in the static deposition model of isolated WT (blue) and Tlr2−/− (green) platelets (rhodamin B-stained) to type I collagen coatings (n = 12) and isotype control. (C) Representative images and dot plot of platelet deposition (rhodamin B-steined) from WT platelets (blue) incubated with plasma isolated from WT (Vwf+/+) or Vwf−/− mice and similarly Tlr2−/− platelets (green) incubated with either plasma isolated from WT (Vwf+/+) or Vwf−/− mice on collagen coated slides (n = 12). All data were expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To exclude a possible role of GPIbα in this model of static platelet deposition to type I collagen coatings, we blocked GPIbα in the washed platelet preparations with a functional inhibitory antibody (Figure 2B). Importantly, Tlr2-deficient platelets treated with isotype control antibody consistently showed a reduced percentage of platelet-covered area relative to WT controls, confirming the platelet deposition defect of the Tlr2-deficient mouse line. Interestingly, pre-incubation with functional inhibitory anti-GPIbα did neither reduce platelet deposition of WT platelets nor did it further diminish the platelet-covered area in the Tlr2-deficient group (Figure 2B). In addition, we performed flow cytometry on the platelet surface expression of other collagen receptors, such as GPVI, the integrin αIIb-subunit, GPIX, and the integrin α2-subunit, but did not note changes (Figure S1). Therefore, similar to deposition to laminin [19], the defective deposition of Tlr2-deficient platelets to type I collagen can likely be attributed to diminished integrin αIIbβ3 function.

As we have previously demonstrated that the presence of microbiota regulates murine plasma VWF levels, leading to increased integrin αIIbβ3-mediated platelet adhesion and thrombus growth in the carotid artery ligation model [19], we next studied the influence of plasma from Vwf-deficient (Vwf−/−) mice on platelet deposition to collagen coatings. Surprisingly, pre-incubation of washed WT platelets with either Vwf-deficient mouse plasma or plasma from WT controls did not lead to changed platelet deposition to type I collagen (Figure 2C). However, incubation of washed Tlr2-deficient platelets with plasma from Vwf-deficient mice resulted in vastly impaired platelet deposition onto type I collagen coatings, which was partially reduced by incubating the washed Tlr2-deficient platelets with WT-plasma (Vwf+/+) (Figure 2B). In essence, this experiment stresses that plasma VWF levels are a critical determinant of static platelet deposition to a type I collagen matrix in Tlr2−/− mice but not in WT controls.

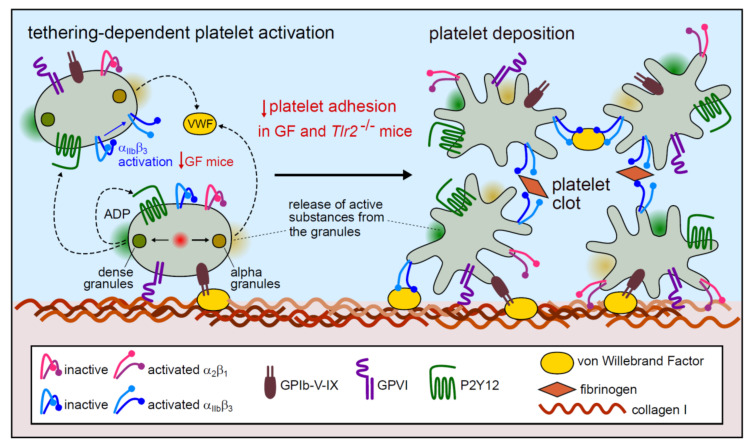

Altogether, our results support the conclusion that adhesion-dependent platelet activation on a type I collagen matrix results in the pre-activation of tethering platelets and to the local exposure of ADP from platelet dense granules and VWF from platelet α-granules (Figure 3). Released ADP locally promotes the activation of integrin αIIbβ3, a process that is impaired in the platelets of GF mice lacking a commensal microbiota. Diminished integrin αIIbβ3 activation on the surface of GF platelets results in impaired binding to the VWF RGD-motif, which in contrast to fibrinogen binding depends on the activated form of the αIIbβ3 integrin [35]. This functional difference could explain the reduced deposition of isolated GF platelets relative to CONV-R controls at static conditions.

Figure 3.

Model of the microbiota-modulation of static platelet deposition to type I collagen matrix. Primary platelet tethering to collagen is mediated by the GPIb-V-IX complex and the platelet GPVI receptor (purple). Subsequent platelet activation leads to α and dense granule secretion, the latter coupled with ADP release, resulting in integrin activation and firm platelet adhesion to collagen through the α2β1 integrin (pink) and to binding of VWF via the integrin αIIbβ3 (blue). The integrin αIIbβ3 also contributes to platelet aggregation by the formation of fibrinogen bridges, in both the inactive and the activated form.

3. Discussion

Our results identified the gut microbiota as an actuating variable of integrin αIIbβ3 activation, which in our experimental conditions was triggered by ADP. This might at least in part explain the observed impairment in static platelet deposition of GF mouse platelets to type I collagen, a platelet deposition defect that is comparable to what we observed with platelets from Tlr2-deficient mice and that is determined by the exposure to varying VWF plasma levels [19]. Thus, impaired platelet integrin αIIbβ3 activation in the absence of microbiota in the GF mouse model could further elucidate how commensals promote VWF-mediated platelet deposition to exposed subendothelial matrix (i.e., to collagen and laminin) [19,27].

Our results are in support of a previous study that demonstrated a tendency of prolonged tail bleeding times in GF mice, a VWF-dependent process, which the authors linked to a decreased activation of GF platelets in response to type I collagen stimulation, as indicated by reduced release of granulophysin and reduced surface exposure of P-selectin and activated integrin αIIbβ3 [29]. Since this early study did not test the role of commensals in ADP-induced platelet activation but rather addressed how activated integrin αIIbβ3 is critically involved in static platelet deposition [35], our data explain the observed impairment of integrin αIIbβ3-mediated platelet deposition in the GF mouse model, which is a critical step in the platelet activation process [19]. Furthermore, in line with our previous study with whole blood from hyperlipidemic mice, demonstrating reduced adhesion-dependent activation of GF mouse platelets [27], and in accordance with diminished collagen-triggered platelet activation, we noted a tendency towards a prolonged clotting time in thrombelastometry experiments on the whole blood of GF mice relative to CONV-R counterparts. Hence, our results for the first time demonstrate that the ADP-triggered activation of integrin αIIbβ3, an important functional signaling loop of platelets that synergizes with other platelet adhesion receptors and contributes to deposition to type I collagen matrix under various conditions, is regulated by commensal microbiota.

Thrombus growth is a concerted process that not only relies on efficient integrin αIIbβ3 activation, but it critically depends on the quantity of bridging ligands in plasma that may interact with the activated integrin. In previous work, we discovered that the extent of platelet deposition to laminin matrices is related to plasmatic VWF levels [19]. Indeed, the collagen–VWF interaction is functionally important as it determines the platelet-release reaction, i.e., the secretion of granula and the exposure and activation of adhesion receptors such as integrin αIIbβ3 [37,38]. Furthermore, our previous work on GF mouse models showed that plasmatic VWF levels are regulated by the presence of commensal microbiota through the sensing of microbiota-derived TLR2 agonists by the hepatic endothelium [19,21]. Here, we propose that, similar to the diminished laminin deposition of Tlr2-deficient platelets, the deposition of Tlr2-deficient platelets to type I collagen coatings is likewise reduced and can be partially rescued by pre-incubation in WT plasma containing higher levels of VWF. As expected, we found platelet deposition to type I collagen to be related to VWF plasma levels. The relevance of TLR2 in arterial thrombosis is complemented by a clinical study in systemic lupus erythematosus patients, which has identified single nucleotide polymorphisms in the Tlr2 gene that were linked to arterial thrombosis [39].

In conclusion, our study provides new evidence for the involvement of TLR2 signaling in the regulation of pro-thrombotic platelet function and the role of the gut microbiota in tuning the sensitivity of integrin αIIbβ3-activating pathways contributing to platelet deposition. Future work should address the role of the commensal microbiota in relation to other vascular TLRs and platelet receptors to define how steady-state microbiota-derived innate immune activation contributes to arterial thrombus formation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

C57BL/6J WT and Tlr2−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Vwf−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background were provided by Bernhard Nieswandt. All experimental animals were 8–14 weeks old male or female mice (at least 20 g body weight) housed in the Translational Animal Research Center (TARC) of the University Medical Center Mainz under specific pathogen free (SPF) or GF conditions in EU type II cages with 2–5 cage companions with standard autoclaved lab diet and water ad libitum, 22 ± 2 °C room temperature and a 12 h light/dark cycle. All groups of mice were sex, age, and weight matched and were free of clinical symptoms. All procedures performed on mice were approved by the local committee on legislation on protection of animals (Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz, Koblenz, Germany; 23177-07/A12-1-006).

4.2. Blood Collection and Platelet Adhesion Under Static Conditions

Blood collection was performed as previously described [19]. Briefly, citrated whole blood was collected by intracardial puncture and centrifuged at 100× g for 10 min without break at room temperature. Platelet-rich plasma was supplemented with 3 mL of modified Tyrode’s buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.3 mM NaH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 5 mM Hepes, 15 μΜ BSA, pH 6.5) [40] and labeled with 5-carboxyflourescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (DCF) (12.5 µg/mL; Invitrogen Life Technologies GmbH, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or rhodamin B (20 µg/mL) for 5 min in the dark. It was then centrifuged at 1200× g for 10 min at room temperature. Where specified, the platelets were incubated with 50 µg/mL antibodies (e.g., anti-IgG and anti GPIbα) for 30 min and washed (see Table 1). The labeled platelets were suspended in either platelet-poor plasma or modified Tyrode’s buffer (pH 7.4) according to the experimental setup to a final concentration of 150 × 103 platelets/µL, and 200 µL were incubated on collagen-coated coverslips purchased from Neuvitro Corporation (El Monte, CA, USA) for 30 min. The coverslips were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and the adherent platelets were visualized with the epifluorescence microscope Olympus BX51WI. A total of 4 images were chosen at random per experiment and the percentage of adherent platelet area was calculated on one field of view per image (100 µm × 150 µm).

Table 1.

List of antibodies.

| Antibody | Clone | Target Molecule | Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse Integrin αIIbβ3 | JON/A | activated mouse integrin alpha IIb beta 3 | Emfret Analytics, Eibelstad, Germany |

| Rat anti-mouse GPIbα | 5A7 | GPIbα | MERU Vasimmune |

| FITC-labeled Rat-antimouse GPIbβ | Xia.C3 | GPIbβ | Emfret Analytics, Eibelstad, Germany |

| FITC-rat anti-mouse GPVI | JAQ1 Rat IgG2A | GPVI | Emfret Analytics, Eibelstad, Germany |

| PE-Anti-Mo CD49c | PE-Anti-Mo CD49c | Integrin α2 | eBioscience, San Diego, California |

| FITC-Rat Anti-Mouse CD41 | MWReg30 | Integrin αIIb | BD Pharmigen San Jose, California |

| Anti-Rat IgG -FITC | - | - | Emfret Analytics, Eibelstad, Germany |

| Rat IgG 2aκ | eBR2a | - | eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA |

4.3. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Platelet Surface Receptors

Studies were conducted using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer with BD FACSDiva software (v6.1.3, BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and FlowJo-Software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). Diluted platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (1:5 with Tyrode’s buffer pH 7.4) was incubated with either 2 or 5 µM ADP (HART Biologicals, Hartlepool, England) for 10 min at room temperature. Activated platelets were stained with PE (phytoerythrin)-labeled JON/A (activated integrin αIIbβ3, Emfret Analytics, Eibelstadt, Germany) for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were supplemented with 400 µL Tyrode’s buffer and analyzed immediately on the flow cytometer, with at least 10,000 events collected per sample. Antibody reactivity is reported as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). For the analysis of surface receptors, washed platelets were incubated with 3 µg/mL of antibody (Table 1) for 30 min at room temperature or according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were supplemented with 400 µL PBS and analyzed immediately on the flow cytometer, with at least 10,000 collected events per sample.

4.4. Thromboelastometry

Citrated (3.8%) whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture. A total of 8 µg/mL of bovine type I collagen (Life Technologies Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added to each sample. Blood was recalcified with 20 mM Ca2+ directly prior to measurement (50 μL of Ca2+-Hepes solution; 100 mM CaCl2 + 1 mM Hepes). Clotting time (CT) and clot formation time (CFT) were measured by a whole blood hemostasis analyzer (ROTEM delta, Tem GmbH, Munich, Germany).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Klaus-Peter Derreth for expert technical assistance. We thank Bernhard Nieswandt for providing the Vwf-deficient mouse line and Wolfram Ruf for providing anti-mouse GPIbα mAb 5A7. Christoph Reinhardt is a Fellow of the Gutenberg Research College at the Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz.

Abbreviations

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| CONV-R | Conventionally raised |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| GF | Germ-free |

| GP | Glycoprotein |

| Ldlr | Low-density lipoprotein-receptor gene |

| MAMPs | Microbial-associated molecular patterns |

| MFI | Mean Fluorescence Intensity |

| NOD | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| Tlr2 | Toll-like receptor 2 gene |

| VWF | Von Willebrand factor |

| WT | Wild-type |

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/19/7171/s1, Figure S1: Platelet surface receptors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.; methodology, K.K., S.J., K.J.; validation, K.K., and S.J.; formal analysis, K.K. and K.G.; investigation, C.K., K.K., S.J., E.W., J.W., and K.G; resources, K.J. and C.R.; data curation, K.K. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K., G.P., and C.R.; writing—review and editing, K.K., G.P., K.J., C.R.; visualization, K.K., G.P.; supervision, K.J. and C.R.; project administration, C.R.; funding acquisition, K.J. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grant support from the Inneruniversitäre Forschungsförderung (Stufe 1) to C.R., the CTH Junior Group Translational Research in Thrombosis and Hemostasis (BMBF 01EO1003 and 01EO1503), DFG Individual Grants (RE 3450/3-1, RE 3450/5-1, RE 3450/5-2), by a project grant of the Naturwissenschaftlich-Medizinisches Forschungszentrum at the Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz (NMFZ) to C.R., and a project grant from the Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation (“Novel and neglected cardiovascular risk factors”) to C.R. K.J. and C.R. are DZHK Scientists. The authors are responsible for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mannhalter C. Biomarkers for arterial and venous thrombotic disorders. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:115–120, 122–126, 128–130, passim. doi: 10.5482/HAMO-13-08-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascher S., Reinhardt C. The gut microbiota: An emerging risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018;48:564–575. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäckhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., Li Y., Xia Y., Xie H., Zhong H., et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:852. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhardt C., Reigstad C.S., Backhed F. Intestinal microbiota during infancy and its implications for obesity. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2009;48:249–256. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318183187c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer F., Ståhlman M., Ilkayeva O., Arnemo J.M., Kindberg J., Josefsson J., Newgard C.B., Fröbert O., Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota modulates energy metabolism in the hibernating brown bear ursus arctos. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1655–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esser D., Lange J., Marinos G., Sieber M., Best L., Prasse D., Bathia J., Rühlemann M.C., Boersch K., Jaspers C., et al. Functions of the microbiota for the physiology of animal metaorganisms. J. Innate. Immun. 2019;11:393–404. doi: 10.1159/000495115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommer F., Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota—Masters of host development and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson F.H., Fåk F., Nookaew I., Tremaroli V., Fagerberg B., Petranovic D., Bäckhed F., Nielsen J. Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1245. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu W., Gregory J.C., Org E., Buffa J.A., Gupta N., Wang Z., Li L., Fu X., Wu Y., Mehrabian M., et al. Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell. 2016;165:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiouptsi K., Reinhardt C. Contribution of the commensal microbiota to atherosclerosis and arterial thrombosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018;175:4439–4449. doi: 10.1111/bph.14483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinross J.M., Alkhamesi N., Barton R.H., Silk D.B., Yap I.K., Darzi A.W., Holmes E., Nicholson J.K. Global metabolic phenotyping in an experimental laparotomy model of surgical trauma. J. Proteome. Res. 2011;10:277–287. doi: 10.1021/pr1003278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilmanski T., Rappaport N., Earls J.C., Magis A.T., Manor O., Lovejoy J., Omenn G.S., Hood L., Gibbons S.M., Price N.D. Blood metabolome predicts gut microbiome alpha-diversity in humans. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:1217–1228. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgueño J.F., Abreu M.T. Epithelial Toll-like receptors and their role in gut homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:263–278. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hörmann N., Brandao I., Jäckel S., Ens N., Lillich M., Walter U., Reinhardt C. Gut microbial colonization orchestrates TLR2 expression, signaling and epithelial proliferation in the small intestinal mucosa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e113080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke T.B., Davis K.M., Lysenko E.S., Zhou A.Y., Yu Y., Weiser J.N. Recognition of peptidoglycan from the microbiota by Nod1 enhances systemic innate immunity. Nat. Med. 2010;16:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cani P.D., Amar J., Iglesias M.A., Poggi M., Knauf C., Bastelica D., Neyrinck A.M., Fava F., Tuohy K.M., Chabo C., et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balmer M.L., Slack E., de Gottardi A., Lawson M.A., Hapfelmeier S., Miele L., Grieco A., Van Vlierberghe H., Fahrner R., Patuto N., et al. The liver may act as a firewall mediating mutualism between the host and its gut commensal microbiota. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:237ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinhardt C., Bergentall M., Greiner T.U., Schaffner F., Ostergren-Lundén G., Petersen L.C., Ruf W., Bäckhed F. Tissue factor and PAR1 promote microbiota-induced intestinal vascular remodelling. Nature. 2012;483:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jäckel S., Kiouptsi K., Lillich M., Hendrikx T., Khandagale A., Kollar B., Hörmann N., Reiss C., Subramaniam S., Wilms E., et al. Gut microbiota regulate hepatic von Willebrand factor synthesis and arterial thrombus formation via Toll-like receptor-2. Blood. 2017;130:542–553. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-754416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’ Atri L.P., Schattner M. Platelet toll-like receptors in thromboinflammation. Front. Biosci. 2017;22:1867–1883. doi: 10.2741/4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinhardt C. The involvement of Toll-like receptor-2 in arterial thrombus formation. Hamostaseologie. 2018;38:223–228. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobias P., Curtiss L.K. Thematic review series: The immune system and atherogenesis. Paying the price for pathogen protection: Toll receptors in atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:404–411. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R400015-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ascher S., Wilms E., Pontarollo G., Formes H., Bayer F., Müller M., Malinarich F., Grill A., Bosmann M., Saffarzadeh M., et al. Gut microbiota restricts NETosis in acute mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020;40:2279–2292. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S., Zhang S., Hu L., Zhai L., Xue R., Ye J., Chen L., Cheng G., Mruk J., Kunapuli S.P., et al. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 receptor is expressed in platelets and enhances platelet activation and thrombosis. Circulation. 2015;131:1160–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stepankova R., Tonar Z., Bartova J., Nedorost L., Rossman P., Poledne R., Schwarzer M., Tlaskalova-Hogenova H. Absence of microbiota (germ-free conditions) accelerates the atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice fed standard low cholesterol diet. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2010;17:796–804. doi: 10.5551/jat.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindskog Jonsson A., Caesar R., Akrami R., Reinhardt C., Fåk Hållenius F., Borén J., Bäckhed F. Impact of gut microbiota and diet on the development of atherosclerosis in Apoe −/− mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:2318–2326. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiouptsi K., Jäckel S., Pontarollo G., Grill A., Kuijpers M.J.E., Wilms E., Weber C., Sommer F., Nagy M., Neideck C., et al. The microbiota promotes arterial thrombosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. mBio. 2019;10:e02298-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02298-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiouptsi K., Pontarollo G., Todorov H., Braun J., Jäckel S., Koeck T., Bayer F., Karwot C., Karpi A., Gerber S., et al. Germ-free housing conditions do not affect aortic root and aortic arch lesion size of late atherosclerotic low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Gut Microbes. 2020;11:1809–1823. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1767463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yano J.M., Yu K., Donaldson G.P., Shastri G.G., Ann P., Ma L., Nagler C.R., Ismagilov R.F., Mazmanian S.K., Hsiao E.Y. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuijpers M.J.E., Schulte V., Bergmeier W., Lindhout T., Brakebusch C., Offermanns S., Fässler R., Heemskerk J.W.M., Nieswandt B. Complementary roles of glycoprotein VI and alpha2beta1 integrin in collagen-induced thrombus formation in flowing whole blood ex vivo. FASEB J. 2003;17:685–687. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0381fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lecut C., Schoolmeester A., Kuijpers M.J.E., Broers J.L.V., van Zandvoort M.A.M.J., Vanhoorelbeke K., Deckmyn H., Jandrot-Perrus M., Heemskerk J.W.M. Principal role of glycoprotein VI in alpha2beta1 and alphaIIbbeta3 activation during collagen-induced thrombus formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1727–1733. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000137974.85068.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruggeri Z.M., Mendolicchio G.L. Adhesion mechanisms in platelet function. Circ. Res. 2007;100:1673–1685. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267878.97021.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savage B., Almus-Jacobs F., Ruggeri Z.M. Specific synergy of multiple substrate-receptor interactions in platelet thrombus formation under flow. Cell. 1998;94:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piétu G., Ribba A.S., Chérel G., Meyer D. Epitope mapping by cDNA expression of a monoclonal antibody which inhibits the binding of von Willebrand factor to platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa. Biochem. J. 1992;284:711–715. doi: 10.1042/bj2840711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage B., Shattil S.J., Ruggeri Z.M. Modulation of platelet function through adhesion receptors. A dual role for glycoprotein IIb-IIIa (integrin alpha IIb beta 3) mediated by fibrinogen and glycoprotein Ib-von Willebrand factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:11300–11306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stark K., Philippi V., Stockhausen S., Busse J., Antonelli A., Miller M., Schubert I., Hoseinpour P., Chandraratne S., von Brühl M.L., et al. Disulfide HMGB1 derived from platelets coordinates venous thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2016;128:2435–2449. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-710632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kainoh M., Ikeda Y., Nishio S., Nakadate T. Glycoprotein Ia/IIa-mediated activation-dependent platelet adhesion to collagen. Thromb. Res. 1992;65:165–176. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laduca F.M., Bell W.R., Bettigole R.E. Platelet-collagen adhesion enhances platelet aggregation induced by binding of VWF to platelets. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253:H1208–H1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser R., Tang L.F., Taylor K.E., Sterba K., Nititham J., Brown E.E., Edberg J.C., McGwin G., Jr., Alarcon G.S., Ramsey-Goldman R., et al. A polymorphism in TLR2 is associated with arterial thrombosis in a multiethnic population of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1882–1887. doi: 10.1002/art.38520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grüner S., Prostredna M., Aktas B., Moers A., Schulte V., Krieg T., Offermanns S., Eckes B., Nieswandt B. Anti–glycoprotein VI treatment severely compromises hemostasis in mice with reduced α2β1 levels or concomitant aspirin therapy. Circulation. 2004;110:2946–2951. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146341.63677.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.