Conspectus

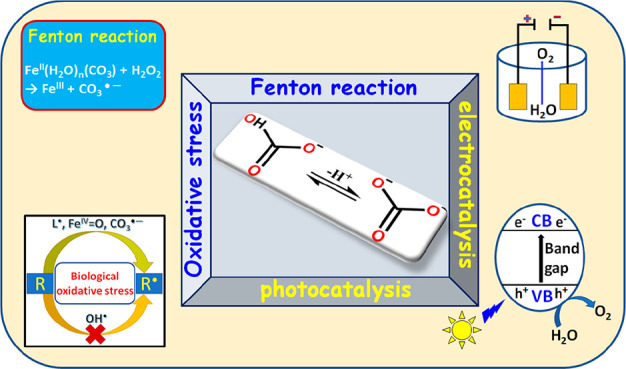

CO2, HCO3–, and CO32– are present in all aqueous media at pH > 4 if no major effort is made to remove them. Usually the presence of CO2/HCO3–/CO32– is either forgotten or considered only as a buffer or proton transfer catalyst. Results obtained in the last decades point out that carbonates are key participants in a variety of oxidation processes. This was first attributed to the formation of carbonate anion radicals via the reaction OH• + CO32– → CO3•– + OH–. However, recent studies point out that the involvement of carbonates in oxidation processes is more fundamental. Thus, the presence of HCO3–/CO32– changes the mechanisms of Fenton and Fenton-like reactions to yield CO3•– directly even at very low HCO3–/CO32– concentrations. CO3•– is a considerably weaker oxidizing agent than the hydroxyl radical and therefore a considerably more selective oxidizing agent. This requires reconsideration of the sources of oxidative stress in biological systems and might explain the selective damage induced during oxidative stress. The lower oxidation potential of CO3•– probably also explains why not all pollutants are eliminated in many advanced oxidation technologies and requires rethinking of the optimal choice of the technologies applied. The role of percarbonate in Fenton-like processes and in advanced oxidation processes is discussed and has to be re-evaluated. Carbonate as a ligand stabilizes transition metal complexes in uncommon high oxidation states. These high-valent complexes are intermediates in electrochemical water oxidation processes that are of importance in the development of new water splitting technologies. HCO3– and CO32– are also very good hole scavengers in photochemical processes of semiconductors and may thus become key participants in the development of new processes for solar energy conversion. In this Account, an attempt to correlate these observations with the properties of carbonates is made. Clearly, further studies are essential to fully uncover the potential of HCO3–/CO32– in desired oxidation processes.

Key References

Burg A.; Shamir D.; Shusterman I.; Kornweitz H.; Meyerstein D.. The Role of Carbonate as a Catalyst of Fenton-like Reactions in AOP Processes: CO3•– as the Active Intermediate. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13096–13099.1This study was the first one to point out that carbonate plays a key role in advanced oxidation processes.

Illés E.; Mizrahi A.; Marks V.; Meyerstein D.. Carbonate-Radical-Anions, and Not Hydroxyl Radicals, Are the Products of the Fenton Reaction in Neutral Solutions Containing Bicarbonate. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 131, 1–6.2This study points out that OH• radicals are not formed in the Fenton reaction under physiological conditions and therefore calls for a revision of our understanding of oxidative stress.

Patra S. G.; Illés E.; Mizrahi A.; Meyerstein D.. Cobalt Carbonate as an Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26, 711–720.3This study is the most detailed study of the role of carbonate in electrocatalytic water oxidation.

Mizrahi A.; Maimon E.; Cohen H.; Kornweitz H.; Zilbermann I.; Meyerstein D.. Mechanistic Studies on the Role of [CuII(CO3)n]2–2n as a Water Oxidation Catalyst: Carbonate as a Non-Innocent Ligand. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1088–1096.4This study describes the use of pulse radiolysis in the study of the mechanisms of oxidations by CO3•– anion radicals.

1. Introduction

All aerated solutions contain a mixture of CO2/HCO3–/CO32–, and their speciation depends on the CO2 solubility under the partial pressure of CO2 in the air and on the following equilibria:5

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Therefore, one commonly considers the role of CO2/HCO3–/CO32– present in solution as a buffer and/or as a proton transfer agent. However, results in recent years have pointed out that the role of CO2/HCO3–/CO32– in redox processes is often of major importance. This is due to three different reasons:

(a) CO2 reacts with peroxides via6

| 4 |

This reaction is clearly slow in neutral solutions and requires relatively high concentrations of H2O2 in order to contribute to redox processes. However, the equilibrium in reaction 4 might shift to the right in the presence of metal cations because of reaction 5:

| 5 |

This reaction was shown to be of importance in catalytic oxidations for M = Mn.7,8 Furthermore, reaction 6 was shown to be exothermic and fast, at least for M = CoII:1

| 6 |

(b) The redox potential of the CO3•–/CO32– couple is 1.57 V vs NHE,9,10 and that for the (CO3•– + H+)/HCO3– couple is clearly somewhat higher because of reaction 3. These potentials are considerably lower than those of the OH•/OH– and (OH• + H+)/H2O couples. Thus, at all pH values CO3•– has the potential to oxidize water, i.e., it is expected to be involved in oxygen evolution reactions (OERs). Therefore, it is thermodynamically easier to oxidize bicarbonate/carbonate than to oxidize water. Not surprisingly, adsorbed carbonates on semiconductors facilitate photocatalytic water oxidation.11−14 Therefore, it is also not surprising that HCO3– and CO32– catalyze the Fenton reaction, forming CO3•– and not OH•.2,15 HCO3– and CO32– also act as electrocatalysts for the OER process.3,4,16−19In the absence of other substrates, CO3•– decomposes via6,20,21

| 7 |

| 8 |

The CO3•– anion radical is considerably less reactive than the OH• radical, and its reactions are more selective.21 The CO3•– anion radical reacts in most systems via the inner-sphere mechanism.9,22

The carbonate anion radical is also formed via the following reactions:23,24

| 9 |

| 10 |

In biological systems it is formed via the following reactions:25

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

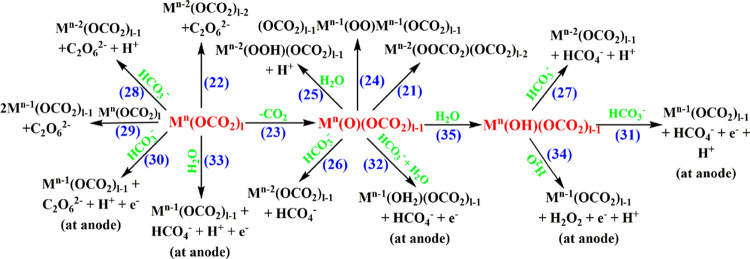

The CO3•– thus formed is believed to be one of the sources of oxidative stress induced by superoxide.26−28 CO3•– is also formed in several enzymatic processes, e.g., in superoxide dismutase.29 The above-mentioned processes are shown graphically in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Mechanisms for the Formation of CO3•– and HCO4– in the Absence of Transition Metal Complexes.

(c) As a strong hard base, carbonate is a very good ligand for high-valent transition metal cations and therefore stabilizes transition metal complexes with higher valence, e.g., MnIII,30 FeIV,III,19,31 CoV/IV/III,3 NiIV/III,32 CuIV/III,4 RuIV,32 etc. In these complexes, the carbonate is a noninnocent ligand and is therefore involved in electrocatalytic OER processes and photoelectrocatalytic processes.

In the next sections these processes are discussed separately.

2. Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation by Metal Carbonate Complexes

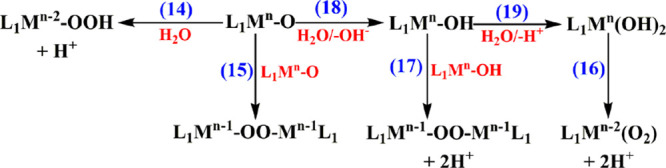

Water oxidation3 is of major importance in understanding the fundamental mechanism of photosynthesis33 and in addressing modern-day energy challenges by means of water electrolysis34,35 and solar energy conversion via photochemical water splitting.36−39 As water oxidation involves the loss of 4e–/4H+ and the formation of the O–O bond, it has a high activation energy. Thus, the use of a catalyst is indispensable. All catalysts reported contain a transition metal, M. It is commonly accepted that water oxidation proceeds via reactions 14–17 in Scheme 2.4

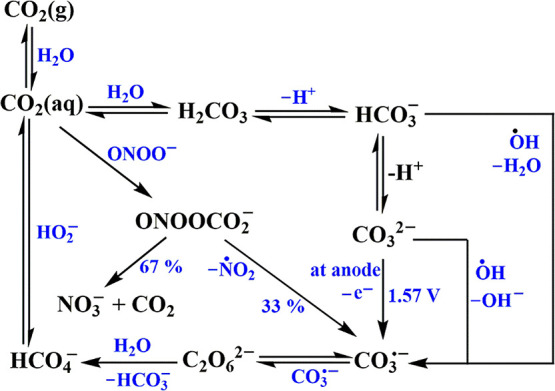

Scheme 2. Outline of Water Oxidation Mechanisms; M Is the Metal, and n Represents the Highest Oxidation State.

The formation of a percarbonate complex in the presence of carbonate has been reported (reaction 20):40

| 20 |

It is evident that in reactions 15–17 in Scheme 2, O2– and OH– behave as noninnocent ligands, where the reactions proceed via radical pathways to form the O–O bond. A similar radical pathway can be expected when other noninnocent ligands are used.

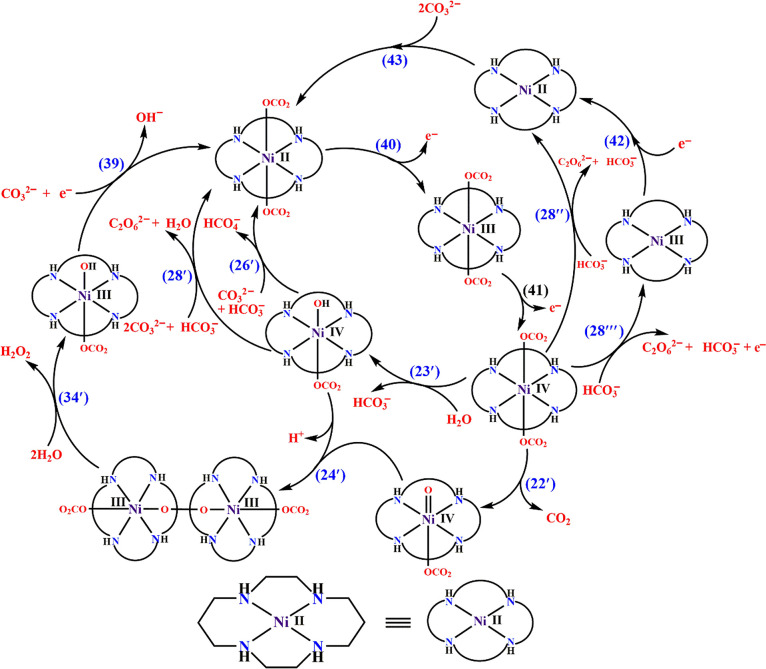

Carbonate can act as a catalyst/cocatalyst in electrocatalytic water oxidation on the basis of the arguments raised in the Introduction. On the basis of the redox properties of carbonate, the reactions shown in Scheme 3, where Mn is formed electrochemically, have to be taken into account to describe the participation of bicarbonate/carbonate in electrocatalytic water oxidation processes. In all of these reactions, the formed peroxide is easily further oxidized to form molecular oxygen at lower potentials. The involvement of bicarbonate/carbonate in homogeneous and heterogeneous electrocatalytic water oxidation, including mechanisms involving specific metal ions (e.g., Cu, Co, Ni), are discussed in the following sections.

Scheme 3. Various Plausible Processes Involved during Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation by Metal Carbonates in Aqueous Bicarbonate/Carbonate Solutions.

2.1. Homogeneous Electrocatalysis

The first study reporting homogeneous electrocatalytic water oxidation in the presence of CO2/HCO3–/CO32– was by Chen and Meyer.17 They showed that CuII(aq) with CO2/HCO3–/CO32– in the medium acts as an efficient water oxidation catalyst on a variety of working electrodes. The catalytic current increases with [CuII] with a cathodic shift of the onset potential. The catalytic current depends linearly on [CuII] in neutral media, while under alkaline conditions it depends on [CuII]2. Therefore, at pH 10.8 a bimolecular mechanism involving the active intermediate was proposed, while at pH 6.7 a single copper site was suggested to be the active species. The redox potential of CuIII/II(H2O)n is >2.3 V vs NHE,41 which is obviously shifted cathodically by the strong carbonate ligand. However, the authors did not clarify the involvement of either CuIII or CuIV as the active species in the catalytic cycle. Later, a density functional theory (DFT) study at pH 8.3 suggested the possibility of a CuIV complex as the active intermediate.4,40

Pulse radiolysis is a useful tool to study the chemical properties of complexes in unstable oxidation states.42,43 This technique was used to study the properties of [CuIII(CO3)n]3–2n formed by the oxidation of [CuII(CO3)n]2–2n by CO3•–. The results suggested the following oxidation mechanism:4

| 36 |

| 37 |

DFT calculations of the NBO charges suggested that significant charge transfer from the CO32– to the central metal ion in CuIII(CO3)n3–2n takes place. The CuIII(CO3)n3–2n thus formed decomposes in a process that obeys second-order kinetics irrespective of the pH of the medium:4

| 38 |

The discrepancy with the electrochemical results in neutral solutions is probably due to the fact that in neutral media the electrocatalytic process proceeds via reactions 30–34 in Scheme 3. This hypothesis cannot be tested by the pulse radiolysis technique.23

The analogous systems containing other divalent first-row transition metal cations in the presence of HCO3–/CO32– pointed out that CoII in the presence of >1 × 10–3 M HCO3–/CO32– is an excellent catalyst for electrocatalytic water oxidation.3 During chronoamperometry, a precipitate is formed that serves as a heterogeneous catalyst for the same (vide infra). Electrochemically, three homogeneous processes are observed:

-

(i)

A relatively small wave is observed at Ep,a ≈ 0.71 V vs Ag/AgCl that is due to the CoIII/II redox couple, i.e., the carbonate ligands shift the redox potential of the CoIII/II couple cathodically by ca. 0.9 V.

-

(ii)

A second wave is observed at Ep,a ≈ 1.10 V vs Ag/AgCl that has a considerably larger current (by a factor of >20) than the first peak. This process is attributed to the CoIV/III(CO3)32–/3– redox couple. The observed potential is in good agreement with the results of DFT calculations. The large current is attributed to catalytic oxidation of bicarbonate/carbonate by the CoIV complex to form HCO4– via reactions analogous to reactions 26–28 and 31 in Scheme 3.

-

(iii)

A process with very large currents, with a current density of 10.50 mA·cm–2 at [CoII] = 0.50 mM at a peak plateau that starts at >1.2 V vs Ag/AgCl, is due to the formation of CoV(CO3)3–, and the observed redox potential is in accord with that calculated using DFT for the CoV/IV(CO3)3–/2– couple. The CoV/IV(CO3)3–/2– complex oxidizes both water and bicarbonate/carbonate. The results suggest that the oxidation proceeds via reaction 20 and reactions 25–28 and 30–33 in Scheme 3. If one assumes, as these equations indicate, that the rate-determining step in this catalytic process involves a two-electron oxidation process, then kcat = 350 s–1. During long-time electrolysis at these potentials, a precipitate forms that is a heterogeneous OER catalyst (vide infra).

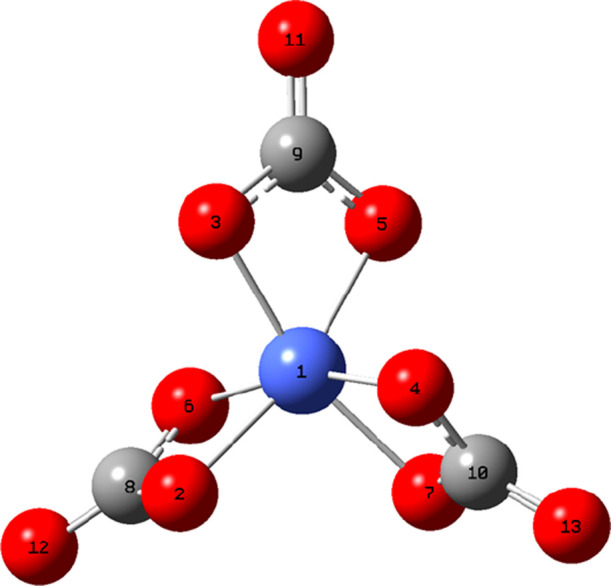

It should be noted that in order to calculate the redox potential, the simplest structures, [CoIII/IV/V(CO3)3]3–/2–/– with octahedral geometries (Figure 1), were considered.

Figure 1.

Structure of [CoV(CO3)3]− obtained at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) level. Reprinted with permission from ref (3). Copyright 2020 Wiley-VCH.

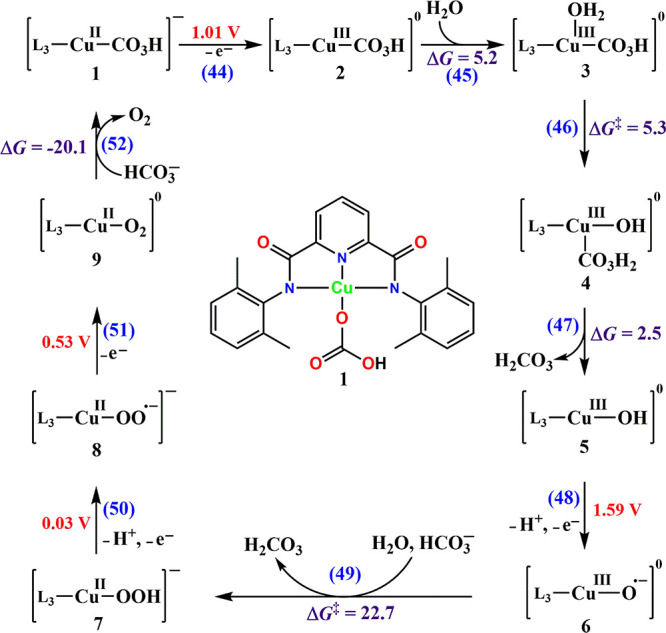

In the examples given above, carbonate was the only ligand lowering the redox potential of the central transition metal cation. However, carbonate can also be a second ligand, where it is the ligand getting oxidized. The following are such systems: NiII(1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane)2+, NiIIL22+,16 CuII(N,N′-bis(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-2,6-pyridinedicarboxamidate), CuIIL3,44 and AlIII(TMPyP) (TMPyP = 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(1-methylpyridin-1-ium-4-yl porphyrinate)).45 In the latter, the central cation is clearly not oxidized, and they act as homogeneous water oxidation catalysts in the presence of bicarbonate/carbonate.

In the system containing the NiL22+ complex, the role of carbonate is due to the lowering of the redox potentials of the NiIII/II and NiIV/III couples and to the reactions shown in Scheme 4. Recently the process of water oxidation by NiIIL22+ was reinvestigated, and it was shown that the formation of nickel oxide on the electrode surface is mainly responsible for the catalysis. However, the large catalytic wave in the cyclic voltammogram and the isomerization of the complex were not addressed. Under long-term chronoamperometry, the oxidation of the organic ligand and the formation of nickel oxide and/or nickel carbonate as nanocomposites cannot be ruled out.

Scheme 4. Electrocatalytic Processes Occurring during Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation Using the NiIIL22+ Complex in HCO3–/CO32–

CuL3 also acts as an active catalyst for water oxidation in the presence of carbonate at pH 9.0–11.0. The proposed mechanism is a “proton shuttle” mechanism, as shown in Scheme 5.44 However, the possible oxidation of carbonate to HCO4– and C2O62– was not considered44 and cannot be ruled out. Carbonate was also shown to act as a cocatalyst in electrocatalytic water oxidation by an aluminum porphyrin (Al(TMPyP)).45 This catalytic system forms H2O2 as the major product. The suggested mechanism involves the formation of an AlIII–percarbonate complex as the key intermediate.45

Scheme 5. Structure of the Complex CuII(N,N′-bis(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-2,6-pyridinedicarboxamidate) (CuIIL3) and its Electrocatalytic Role in Water Oxidation in the Presence of Bicarbonate.

Reprinted from ref (44). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

2.2. Heterogeneous Catalysis

Bicarbonate and carbonate are involved also in heterogeneous electrocatalytic water oxidation processes via precipitates on the anode. Reactions analogous to reactions 20–34 are expected on the electrodes. Here the role of the carbonate is also dual: it lowers the redox potential of the central cation, and it has a lower oxidation potential than OH–/H2O. Processes analogous to reactions 22, 23, 29, and 33 in Scheme 3 require carbonate in the homogeneous medium only to replace the carbonate loss from the precipitate. Processes analogous to reactions 21, 24–27, 31, 32, and 34 in Scheme 3 can also proceed without any carbonate in the precipitate on the electrode:

| 26′ |

| 27′ |

| 31′ |

| 32′ |

An example of the latter type of catalysis is the report that NiII(aq) adsorbed on a SiO2 sol–gel matrix and mixed with graphite acts as an OER electrocatalyst in solutions containing HCO3–/CO32– with a current proportional to [HCO3–/CO32–].46,47 Clearly one cannot rule out that ligand exchange in the sol–gel matrix transforms the NiII(aq) into carbonate complexes. In this study it was proposed that the catalytic process involves the formation of CO3•– radical anions.46

In the study of homogeneous electrocatalysis of the OER in solutions containing CoII and HCO3–/CO32–, it was noted that during chronoamperometry a green precipitate of Na3[Co(CO3)3] is formed.3 This precipitate on the anode surface serves as an excellent heterogeneous catalyst in the presence of bicarbonate/carbonate. This catalytic process was shown to be in agreement with reactions analogous to reactions 22 and 26–34 in Scheme 3. DFT calculations suggest that the active species in these process is the CoV(CO3)3– complex.3

In an analogous study,18 a precipitate was formed on an anode by electrolysis of a CO2-saturated solution containing FeII(aq) and HCO3–. The thin film thus formed contained FeIII, O2–, OH–, and CO32–. This film was shown to be a good OER electrocatalyst for which the current increased with [HCO3–/CO32–].18 The detailed mechanism causing the electrocatalytic process was not discussed. Clearly reactions analogous to reactions 22 and 26–34 are probably responsible for the electrocatalytic properties of this precipitate. The observation that the film is stable during electrolysis in carbonate solutions that do not contain FeII ions proves that the mechanism does not involve reduction of the Fe ions in the precipitate to FeII and dissolution to the aqueous phase.

An analogous study involving nickel carbonate solutions48 resulted in the formation of an analogous NiIII(HCO3–)n3–n/NiIII(CO32–)n3–2n precipitate on the anode that is a good electrocatalyst for water oxidation in solutions containing NiII and HCO3–/CO32–. However, the precipitate dissolves during electrolysis when no NiII ions are present in solution. This proves that the catalytic step involves the reduction of a NiIV complex into a NiII complex that is soluble, i.e. via reactions analogous to reactions 21, 22, 25, and 26–28 in Scheme 3. In another study,49 an amorphic nickel carbonate nanowire array on a nickel foam (NiCO3/NF) anode was prepared. This modified electrode is a very good electrocatalyst for water oxidation in solutions containing only HCO3–/CO32–.49 The source of the discrepancy between these two studies might be that the nickel foam supplies the needed nickel to preserve the precipitate. The use of a mixture of salts of iron and nickel in carbonate solutions was also reported to form an oxide precipitate that acts as an efficient catalyst in carbonate media to oxidize water.19

To sum up this section, the results suggest that precipitates of transition metal oxides and/or carbonates, where the central cation can be oxidized to a high oxidation state, on anodes serve as good electrocatalysts for water oxidation in solutions containing HCO3–/CO32–. The detailed mechanisms of these catalytic processes depend on the properties of the central cation. The advantage of these catalytic processes is that all of the components are stable inorganic species that are not consumed during the catalytic process.

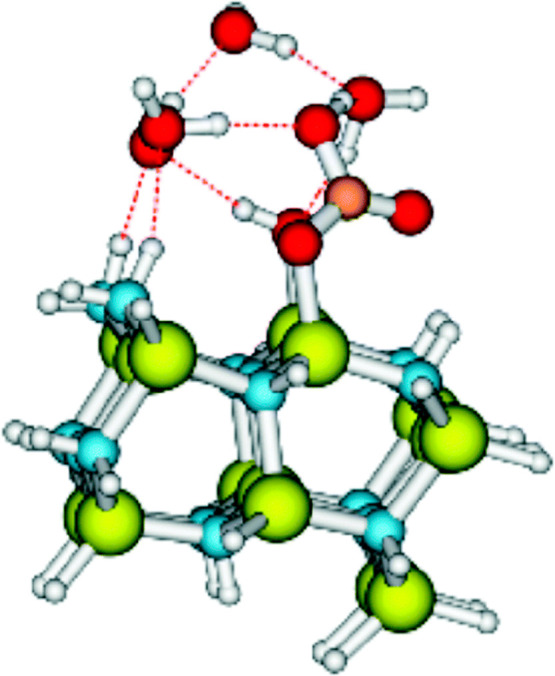

3. Photocatalysis

The difference in the oxidation potentials of the CO3•–/CO32– and OH•/OH–(aq) or (OH• + H3O+)/2H2O couples suggests that the holes formed photochemically in semiconductors will oxidize HCO3–/CO32– faster and in higher yields than the oxidation of water. This was verified computationally in a DFT study of the photocatalysis by GaN (Figure 2).13 The condition for this is that adsorption of HCO3–/CO32– on the surface of the semiconductor, i.e., a relatively high point of zero charge (the pH at which the net charge of the adsorbent’s surface is zero or positive), is favorable. The products of these oxidations are either CO3•– or C2O62–. Indeed, several studies have pointed out that the presence of HCO3–/CO32– in the system catalyzes photochemical water oxidation.14,50,51 Furthermore, it has been shown that photochemical oxidation of SO2 in aqueous media is enhanced by the presence of carbonate.11 It was proposed that the formation of CO3•– is involved.

Figure 2.

Structure of carbonated GaN. Ga, yellow; C, brown; H, white; O, red; N, blue. Reprinted with permission from ref (13). Copyright 2016 The PCCP Owner Societies.

In the previous section, the role of metal carbonate precipitates as efficient heterogeneous electrocatalysts for water oxidation was reviewed. It seemed to be of interest to check whether these precipitates are photoactive, and indeed, preliminary results32 point out that precipitates of cobalt and nickel carbonate act as photoelectrocatalysts for water and methanol oxidations.

4. Percarbonate as an Oxidation Agent

In principle, percarbonates are involved in two types of processes:

-

1.

An inorganic percarbonate salt, e.g., sodium percarbonate (Na2CO4·1.5H2O2), is used as the oxidizing agent. These percarbonates are used mainly in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) (vide infra). Their mechanisms of oxidation are suggested to proceed via formation of H2O2 upon dissolution followed by Fenton-like and/or photolytic processes and/or reaction with O3, often involving CO3•– anion radicals.52−55

-

2.

The percarbonate is formed in situ via the reaction of H2O2 with a transition metal carbonate complex, analogous to reaction 4 followed by 5, or via reactions analogous to reaction 6 or reaction 69 below.

The first peroxocarbonate complex of a transition metal was reported by Hashimoto et al.56 It was formed via the reaction of a bis(μ-hydroxo)diiron(III) complex with H2O2 and CO2. Oxidative degradation of an organic dye, Orange II, by MnIII(TPPS) (TPPS = 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)-21H,23H-porphyrin) in carbonate buffer was proposed to involve the formation of a percarbonate–metal complex that undergoes decomposition to form a MnIV=O species and degrades Orange II via reactions 53–56:8

| 53 |

| 54 |

| 55 |

| 56 |

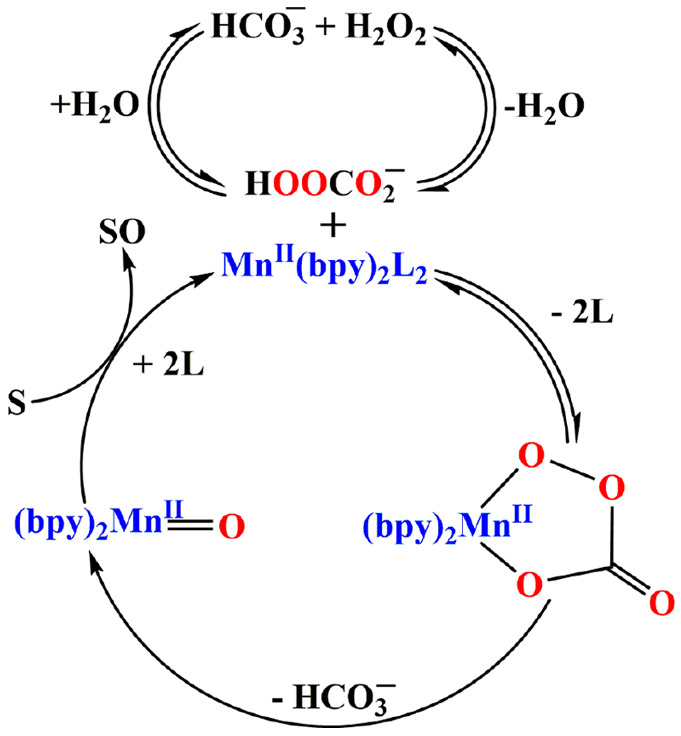

Catalytic oxidation of azo dyes by [MnII(bpy)2Cl2] and [Mn2III/IV(μ-O)2(bpy)4](ClO4)3 also involves a similar mechanism.57 As reactions 53–55 probably do not involve an oxygen atom transfer, it is reasonable to propose that intermediates in which the percarbonate is ligated to the central MnIII are formed (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Proposed Mechanism for the Degradation of Substrate (S) by the Complex Mn(bpy)2L2 (L = Water or Carbonate) Formed from Mn(bpy)2Cl2 or [Mn2III/IV(μ-O)2(bpy)4](ClO4)3.

Reprinted with permission from ref (57). Copyright 2010 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Oxidation of calmagite (H3CAL) dye in aqueous solution using H2O2 at pH 7.5–9.0 is accelerated considerably in the presence of HCO3–.58 The proposed mechanism involves the following steps:

| 57 |

| 58 |

| 59 |

| 60 |

| 61 |

| 62 |

It should be pointed out that [MnIII(CAL)(HCO4)]− might also decompose to form a MnIV complex and CO3•– anion radical. The degradation of various dyes using Mn/H2O2/HCO3– has been reported.7 It was shown that under visible light percarbonate catalyzes the degradation of rhodamine B in the presence of FeOCl.59 Oxidations of primary alcohols to carbonyl compounds using catalytic amounts of percarbonate and dichromate were also reported.60

5. Role of Bicarbonate in Fenton and Fenton-like Reactions

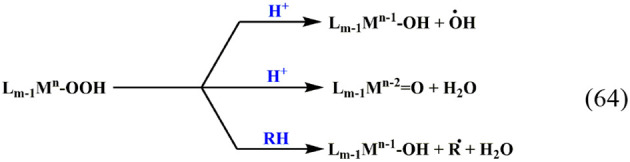

The Fenton reaction, Fe(H2O)62+ + H2O2, is of major importance. Thus, a search in SciFinder for “Fenton” limited to articles in English for 2019 yielded 2371 results. The major source of this importance is in its role in inducing oxidative stress61−66 and its role in AOPs.67−70 The Fenton reaction and Fenton-like reactions, in which another low-valent metal ion replaces Fe and/or another ligand L replaces H2O and/or another peroxide replaces H2O2, were shown to proceed via a variety of mechanisms:71

| 63 |

|

64 |

where RH is a substrate. The reactions always proceed via the inner-sphere mechanism.

Still, nearly all of the recent articles cite the Fenton reaction as proceeding via the formation of OH•. Furthermore, recent results point out that in systems where it is difficult to oxidize the central cation, the central cation is not oxidized in the process, and the reaction proceeds via the following mechanism:72,73

| 65 |

| 66 |

Reaction 66 indicates that H2O2 ligated to a central cation can oxidize another ligand that has no bond with it. DFT calculations verified this for other ligands, including carbonate.74

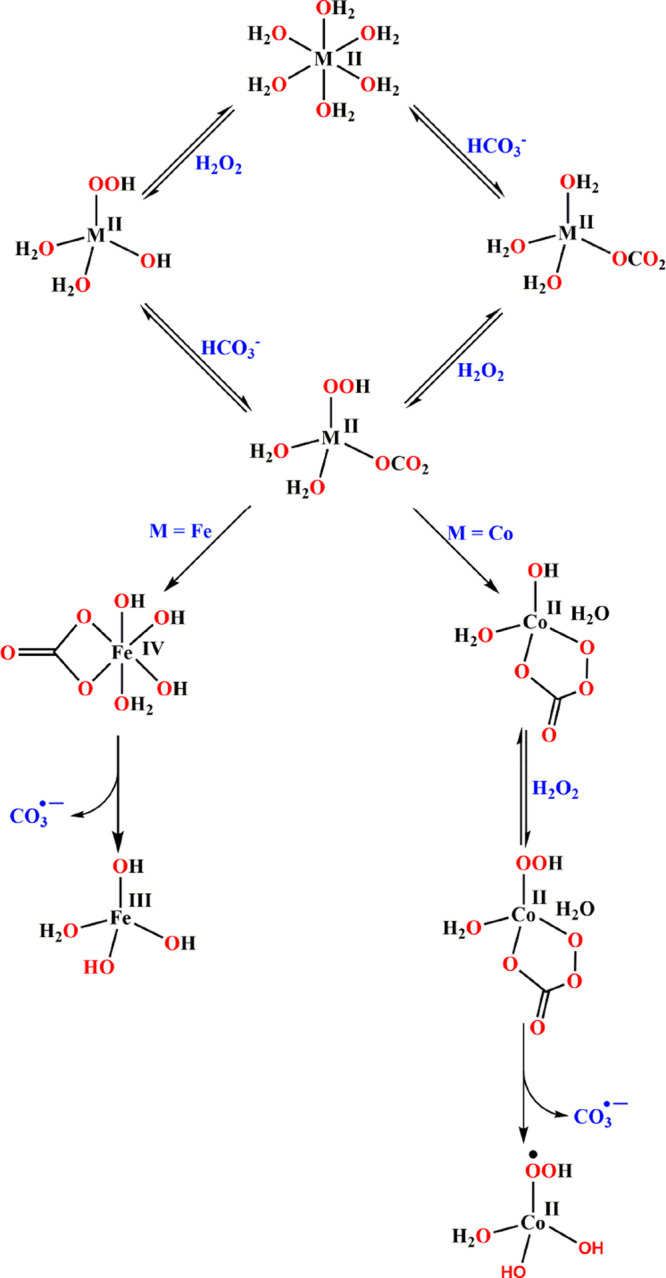

For the carbonate-containing systems, three cases were studied in detail:

(I) The reaction of H2O2 with Co(H2O)62+ (10–25.0 mM) in the presence of 0–0.6 mM HCO3– was studied. Under these conditions, [CoII(H2O)62+] > [CoII(H2O)5(HCO3)+]. The following reactions were observed:1

| 67 |

| 68 |

| 69 |

| 70 |

| 71 |

These results point out the following: (a) No OH• radicals are formed. Though a percarbonate ligand is formed as an intermediate in the process, the active oxidizing agent formed is the CO3•– anion radical. (b) The central CoII cation is not oxidized during the process. The process is analogous to reactions 65 and 66 with k = 2. Thus, in AOPs with CoII(H2O)62+ and H2O2, the active species is CO3•– and not OH• as usually assumed.75 The mechanism is outlined in Scheme 7.

Scheme 7. Proposed Mechanisms of the Fenton Reaction for M(H2O)62+ (M = Fe, Co) in H2O.

(II) The Fenton reaction at pH 7.4 in solutions containing 2.0 × 10–5 M FeII(H2O)62+, 0–3.0 mM HCO3–, and 0–0.8 mM H2O2 was studied. Under these conditions, [FeII(H2O)3(HCO3–)]+ constitutes less than 3% of the FeII(H2O)62+. However, the observed rate constants increase dramatically with [HCO3–]. The following reactions were observed:

| 72 |

| 73 |

This reaction sequence is the major one for [HCO3–] < 1.0 mM. For [HCO3–] > 1.0 mM, reactions 74 and 75 lead to the formation of (CO32–)FeII(OOH–)(H2O)2–, i.e., the same intermediate formed in reaction 73:

| 74 |

| 75 |

The mechanism is shown in Scheme 7. In the Fe Fenton reaction, metal ion oxidation occurs, whereas in the Co Fenton-like reaction, the metal oxidation state does not change. One more difference is that for Co a cyclic percarbonate complex is formed, but this does not occur in the case of Fe. The (CO32–)FeII(OOH–)(H2O)2– thus formed decomposes via the following reactions:

| 76 |

| 77 |

Thus, also in this system, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) formed under physiological conditions (i.e., in the presence of ∼1.0 mM HCO3–) is not the OH• radical as commonly assumed.

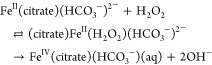

(III) The results concerning the Fenton reaction in the presence of HCO3– suggest that under physiological conditions, the Fenton reaction yields CO3•– and not OH• radicals as commonly assumed, and this is of major importance. However, since in biological media FeII ions are not present as FeII(H2O)62+ but appear in the mobile pool mainly as FeII(citrate), the Fenton reaction was studied15 in solutions containing 2.0 × 10–5 M FeII(H2O)62+, 0–2.0 mM sodium citrate, 0–8.0 mM NaHCO3, and 0–0.39 mM H2O2. It was shown that the kinetics of the process and the composition of the final products in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide depend dramatically on the concentration of HCO3–. The following mechanism was proposed:15

|

78 |

The mechanism of decomposition of FeIV(citrate)(HCO3–)aq was not clarified. It can decompose via the formation of CO3•– or via oxidation of the citrate ligand. Alternatively, the mechanism might involve reactions 79 and 80,

| 79 |

| 80 |

where (citrate)FeII(H2O2)(HCO3–)2– is formed in a reaction analogous to reaction 76. It was suggested that this mechanism fits the results better.

The results of these three studies of the mechanisms of Fenton and Fenton-like reactions point out that the role of bicarbonate present in biological systems and in wastewater cannot be overlooked. This conclusion was recently verified.28

6. Other Biological Sources of CO3•–

As stated in the Introduction, CO3•– is formed biologically via the reaction of peroxonitrite with CO2 (reactions 11–13).76 The formation of NO2• and CO3•– is believed to be the main mechanism via which O2•– causes oxidative stress.77,78 CO3•– is also formed enzymatically by the enzymes superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD, SOD-1)79 and xanthine oxidase.80

The CO3•– anion radicals formed in biological systems can oxidize nucleobases26−28,77,81,82 and proteins83,84 and peroxidize low-density lipoprotein.85

7. Advanced Oxidation Processes/Technologies

The treatment of polluted water and soil is of major importance. Many organic pollutants are treated by advanced oxidation processes/technologies.86 There is still no optimal treatment for pollutants, and a variety of technologies have been studied. These include chemical oxidation by peroxides, Fenton and Fenton-like processes (including photo-Fenton and electrochemical Fenton), ozone, photochemical processes (including solar light using TiO2 as a photocatalyst), electrochemical processes, microwave processes, ultrasonic processes, ionizing radiation, hydrodynamic cavitation, and various combinations of these techniques.86 Carbonate is involved in these processes via the addition of percarbonate as an oxidizing agent,52,55,87−91 the involvement of the HCO3–/CO32– that is always present in water,75,92−96 and sometimes by the addition of HCO3–/CO32– to the system.97

The role of the added percarbonate is clear. However, the role of the bicarbonate/carbonate present in the solution is more complicated. For many systems it has been proposed that bicarbonate/carbonate reacts with the OH• radical initially formed, thus decreasing the reactivity of the oxidizing species formed but increasing its lifetime and its selectivity in the choice of substrates.52,94,95 On the other hand, for some systems involving Fenton and photochemical reactions, at least the carbonate is involved in the ROS formation and therefore increases the pollutant decomposition yield.75 It should be pointed out that the Fenton reaction in neutral solutions in the absence of bicarbonate/carbonate forms FeIV(aq) and not OH• radicals.98 This is commonly not addressed in publications on the Fenton reaction discussed in AOPs. Thus, in these systems the presence of bicarbonate/carbonate exchanges FeIV(aq) with CO3•– as discussed above.

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

CO2, HCO3–, and CO32– are present in all aquatic media at pH > 4 if no effort to remove them is made. Usually one considers their role only as buffers and/or proton transfer agents. The recent results discussed in this Account point out the important role of HCO3–/CO32– in a variety of catalytic oxidation processes in aqueous media. This role is due to the following properties of carbonates:

-

1.

Carbonate is a strong hard ligand that stabilizes transition metal complexes in high oxidation states. These complexes are key intermediates in electrochemical water oxidation processes.

-

2.

The redox potential of the CO3•–/CO32– and (CO3•– + H+)/HCO3– couples is considerably lower than that of the OH•/OH– and (OH• + H+)/H2O couples. Therefore, HCO3– and CO32– act as cocatalysts in water oxidation and are involved in Fenton-like processes.

-

3.

Percarbonate, as a bidentate ligand, is easily formed in the presence of transition metal cations with fast ligand exchange properties, HCO3–/CO32–, and peroxides.

The results obtained thus far point out that the presence of HCO3–/CO32– dramatically changes the mechanisms of the Fenton and Fenton-like reactions. These findings require reassessment of the major sources of oxidative stress in biological systems and of the role of carbonate anion radicals in oxidative stress. Furthermore, the results point out the activity of HCO3–/CO32– as catalysts/cocatalysts for water oxidation electrochemically and photochemically. This is of importance in developing technologies for efficient water splitting processes.

Extremely little has been done to date on the application of HCO3–/CO32– in catalytic oxidations of specific substrates performed electrochemically, photochemically, and photoelectrochemically. Also, the role of HCO3–/CO32– in Fenton-like processes using other peroxides (e.g., S2O82–, HSO5–, and ROOH, where R is an aliphatic residue) has not been studied. These studies might be of importance in the development of new advanced oxidation technologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Pazy Foundation for Grant RA 1700000337, which enabled this project. S.G.P. thanks Ariel University for a postdoctoral fellowship.

Biographies

Shanti Gopal Patra received his B.Sc. from Burdwan University in India in 2010 and his M.Sc. from the Chemistry Department at IIT Kanpur in India in 2012. He received his Ph.D. in chemistry from the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science and Jadavpur University in 2018 under the supervision of Prof. Dipankar Datta and Prof. Abhishek Dey. Since June 2018 he has worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Chemical Sciences Department of Ariel University under the supervision of Prof. Dan Meyerstein. His research interests include inorganic chemistry, catalysis, electrochemistry, nanomaterials, and computational chemistry.

Amir Mizrahi received his Ph.D. in chemistry from Ben-Gurion University under the supervision of Prof. Dan Meyerstein and Prof. Israel Zilbermann. Since 2013 he has been employed by NRCN as a senior research scientist in the Inorganic Chemistry Department. His main field of interest is the redox chemistry of transition metals in aqueous/organic solutions, with an emphasis on full characterization of their reaction mechanisms and various reaction intermediates studied by spectroscopic, kinetic, and electrochemical techniques.

Dan Meyerstein studied chemistry at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, earning his M.Sc. in 1961 and his Ph.D. in 1965. After a postdotoral fellowship at Argonne National Laboratory in the USA, he joined Ben-Gurion University in 1968 and was promoted to Professor in 1978. He has served as the President of the Israel Chemical Society in 1988–1991, deputy rector of Ben-Gurion University in 1990–1994, and President of Ariel University in 1995–2012. He is now Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at Ariel University and Professor Emeritus at Ben-Gurion University. His research interests include reaction mechanisms, catalysis, radical processes, radiation chemistry, electrochemistry, and nanochemistry.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Burg A.; Shamir D.; Shusterman I.; Kornweitz H.; Meyerstein D. The Role of Carbonate as a Catalyst of Fenton-like Reactions in AOP Processes: CO3•– as the Active Intermediate. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 13096–13099. 10.1039/C4CC05852F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illés E.; Mizrahi A.; Marks V.; Meyerstein D. Carbonate-Radical-Anions, and Not Hydroxyl Radicals, Are the Products of the Fenton Reaction in Neutral Solutions Containing Bicarbonate. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 131, 1–6. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra S. G.; Illés E.; Mizrahi A.; Meyerstein D. Cobalt Carbonate as an Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26, 711–720. 10.1002/chem.201904051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi A.; Maimon E.; Cohen H.; Kornweitz H.; Zilbermann I.; Meyerstein D. Mechanistic Studies on the Role of [CuII(CO3)n]2–2n as a Water Oxidation Catalyst: Carbonate as a Non-Innocent Ligand. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1088–1096. 10.1002/chem.201703742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daschakraborty S.; Kiefer P. M.; Miller Y.; Motro Y.; Pines D.; Pines E.; Hynes J. T. Reaction Mechanism for Direct Proton Transfer from Carbonic Acid to a Strong Base in Aqueous Solution I: Acid and Base Coordinate and Charge Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 2271–2280. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhmutova-Albert E. V.; Yao H.; Denevan D. E.; Richardson D. E. Kinetics and Mechanism of Peroxymonocarbonate Formation. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 11287–11296. 10.1021/ic1007389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart S.; van Eldik R. Manganese Compounds as Versatile Catalysts for the Oxidative Degradation of Organic Dyes. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 65, 165–215. 10.1016/B978-0-12-404582-8.00005-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Procner M.; Orzeł Ł.; Stochel G.; van Eldik R. Catalytic Degradation of Orange II by MnIII(TPPS) in Basic Hydrogen Peroxide Medium: A Detailed Kinetic Analysis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 3462–3471. 10.1002/ejic.201800485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberg S.; Mizrahi A.; Meyerstein D.; Kornweitz H. Carbonate and Carbonate Anion Radicals in Aqueous Solutions Exist as CO3(H2O)62– and CO3(H2O)6– Respectively: The Crucial Role of the Inner Hydration Sphere of Anions in Explaining Their Properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 9429–9435. 10.1039/C7CP08240A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D. A.; Huie R. E.; Koppenol W. H.; Lymar S. V.; Merényi G.; Neta P.; Ruscic B.; Stanbury D. M.; Steenken S.; Wardman P. Standard Electrode Potentials Involving Radicals in Aqueous Solution: Inorganic Radicals (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1139–1150. 10.1515/pac-2014-0502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; You C.; Tan Z. Enhanced Photocatalytic Oxidation of SO2 on TiO2 Surface by Na2CO3 Modification. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 350, 89–99. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.05.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuku K.; Miyase Y.; Miseki Y.; Funaki T.; Gunji T.; Sayama K. Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Peroxide Production from Water on a WO3/BiVO4 Photoanode and from O2 on an Au Cathode Without External Bias. Chem. - Asian J. 2017, 12, 1111–1119. 10.1002/asia.201700292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornweitz H.; Meyerstein D. The Plausible Role of Carbonate in Photo-catalytic Water Oxidation Processes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 11069–11072. 10.1039/C5CP07389H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miseki Y.; Sayama K. Photocatalytic Water Splitting for Solar Hydrogen Production Using the Carbonate Effect and the Z-Scheme Reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1801294. 10.1002/aenm.201801294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Illés E.; Patra S. G.; Marks V.; Mizrahi A.; Meyerstein D. The FeII(Citrate) Fenton Reaction under Physiological Conditions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 206, 111018. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2020.111018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg A.; Wolfer Y.; Shamir D.; Kornweitz H.; Albo Y.; Maimon E.; Meyerstein D. The Role of Carbonate in Electro-Catalytic Water Oxidation by Using Ni(1,4,8,11-Tetraazacyclotetradecane)2+. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 10774–10779. 10.1039/C7DT02223A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Meyer T. J. Copper(II) Catalysis of Water Oxidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 700–703. 10.1002/anie.201207215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Bai L.; Li H.; Wang Y.; Yu F.; Sun L. An Iron-Based Thin Film as a Highly Efficient Catalyst for Electrochemical Water Oxidation in a Carbonate Electrolyte. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 5753–5756. 10.1039/C6CC00766J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Ji L.; Chen Z. In Situ Rapid Formation of a Nickel–Iron-Based Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6987–6992. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto O.; Bonini M. G.; Amanso A. M.; Linares E.; Santos C. C. X.; De Menezes S. L. Nitrogen Dioxide and Carbonate Radical Anion: Two Emerging Radicals in Biology. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 841–859. 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NDRL/NIST Solution Kinetics Database on the Web. National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2002. https://kinetics.nist.gov/solution/.

- Mizrahi A.; Zilbermann I.; Maimon E.; Cohen H.; Meyerstein D. Different Oxidation Mechanisms of MnII(Polyphosphate)n by the Radicals And. J. Coord. Chem. 2016, 69, 1709–1721. 10.1080/00958972.2016.1190451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson M. S.; Dorfman L.. Pulse Radiolysis; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton G. V.; Elliot A. J. Rate Constant for Reaction of Hydroxyl Radicals with Bicarbonate Ions. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum., Part C. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1986, 27, 241–243. 10.1016/1359-0197(86)90059-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S.; Czapski G. Formation of Peroxynitrate from the Reaction of Peroxynitrite with CO2: Evidence for Carbonate Radical Production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 3458–3463. 10.1021/ja9733043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crean C.; Geacintov N. E.; Shafirovich V. Oxidation of Guanine and 8-Oxo-7,8-Dihydroguanine by Carbonate Radical Anions: Insight from Oxygen-18 Labeling Experiments. Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 5185–5188. 10.1002/ange.200500991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A. M.; Burrows C. J. G-Quadruplex Folds of the Human Telomere Sequence Alter the Site Reactivity and Reaction Pathway of Guanine Oxidation Compared to Duplex DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 593–607. 10.1021/tx400028y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A. M.; Burrows C. J. Iron Fenton Oxidation of 2′-Deoxyguanosine in Physiological Bicarbonate Buffer Yields Products Consistent with the Reactive Oxygen Species Carbonate Radical Anion Not Hydroxyl Radical. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 9779–9782. 10.1039/D0CC04138F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medinas D. B.; Cerchiaro G.; Trindade D. F.; Augusto O. The Carbonate Radical and Related Oxidants Derived from Bicarbonate Buffer. IUBMB Life 2007, 59, 255–262. 10.1080/15216540701230511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorobrykh A.; Dasgupta J.; Kolling D. R. J.; Terentyev V.; Klimov V. V.; Dismukes G. C. Evolutionary Origins of the Photosynthetic Water Oxidation Cluster: Bicarbonate Permits Mn2+ Photo-Oxidation by Anoxygenic Bacterial Reaction Centers. ChemBioChem 2013, 14, 1725–1731. 10.1002/cbic.201300355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielski B. H. J. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 108–113. 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86096-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerstein D. Unpulished work.

- Koroidov S.; Shevela D.; Shutova T.; Samuelsson G.; Messinger J. Mobile Hydrogen Carbonate Acts as Proton Acceptor in Photosynthetic Water Oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 6299–6304. 10.1073/pnas.1323277111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.; Wu Y.; Lai W.; Cao R. Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation by a Water-Soluble Nickel Porphyrin Complex at Neutral PH with Low Overpotential. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 5604–5613. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasylenko D. J.; Ganesamoorthy C.; Borau-Garcia J.; Berlinguette C. P. Electrochemical Evidence for Catalytic Water Oxidation Mediated by a High-Valent Cobalt Complex. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 4249. 10.1039/c0cc05522k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstrum-Acevedo J. H.; Brennaman M. K.; Meyer T. J. Chemical Approaches to Artificial Photosynthesis. 2. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 6802–6827. 10.1021/ic050904r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy J. P.; Brudvig G. W. Water-Splitting Chemistry of Photosystem II. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4455–4483. 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust D.; Moore T. A.; Moore A. L. Solar Fuels via Artificial Photosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1890–1898. 10.1021/ar900209b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L.; Hammarström L.; Åkermark B.; Styring S. Towards Artificial Photosynthesis: Ruthenium-Manganese Chemistry for Energy Production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001, 30, 36–49. 10.1039/a801490f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winikoff S. G.; Cramer C. J. Mechanistic Analysis of Water Oxidation Catalyzed by Mononuclear Copper in Aqueous Bicarbonate Solutions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 2484–2489. 10.1039/C4CY00500G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerstein D. Trivalent Copper. II. Pulse Radiolytic Study of the Formation and Decomposition of Amino Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1971, 10, 2244–2249. 10.1021/ic50104a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerstein D. Complexes of Cations in Unstable Oxidation States in Aqueous Solutions as Studied by Pulse Radiolysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1978, 11, 43–48. 10.1021/ar50121a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polyansky D. E.; Hurst J. K.; Lymar S. V. Application of Pulse Radiolysis to Mechanistic Investigations of Water Oxidation Catalysis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 2014, 619–634. 10.1002/ejic.201300753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.; Wang N.; Lei H.; Guo D.; Liu H.; Zhang Z.; Zhang W.; Lai W.; Cao R. Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation by a Water-Soluble Copper(II) Complex with a Copper-Bound Carbonate Group Acting as a Potential Proton Shuttle. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 13368–13375. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttassery F.; Sebastian A.; Mathew S.; Tachibana H.; Inoue H. Promotive Effect of Bicarbonate Ion on Two-Electron Water Oxidation to Form H2O2 Catalyzed by Aluminum Porphyrins. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1939–1948. 10.1002/cssc.201900560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfer Y. Ph.D. Thesis, Ben-Gurion University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi A.; Meyerstein D. Plausible Roles of Carbonate in Catalytic Water Oxidation. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 74, 343–360. 10.1016/bs.adioch.2019.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef O. M.Sc. Thesis, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y.; Ma M.; Ji X.; Xiong X.; Sun X. Nickel-Carbonate Nanowire Array: An Efficient and Durable Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation under Nearly Neutral Conditions. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2018, 12, 467–472. 10.1007/s11705-018-1717-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Wang X.; Jia Y.; Chen X.; Han H.; Li C. Titanium Dioxide-Based Nanomaterials for Photocatalytic Fuel Generations. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9987. 10.1021/cr500008u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa H.; Shiraishi C.; Tatemoto M.; Kishida H.; Usui D.; Suma A.; Takamisawa A.; Yamaguchi T. Solar Hydrogen Production by Tandem Cell System Composed of Metal Oxide Semiconductor Film Photoelectrode and Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell. Proc. SPIE 2007, 6650, 665003. 10.1117/12.773366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.; Duan X.; O’Shea K.; Dionysiou D. D. Degradation and Transformation of Bisphenol A in UV/Sodium Percarbonate: Dual Role of Carbonate Radical Anion. Water Res. 2020, 171, 115394. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froger C.; Quantin C.; Gasperi J.; Caupos E.; Monvoisin G.; Evrard O.; Ayrault S. Impact of Urban Pressure on the Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of PAH Fluxes in an Urban Tributary of the Seine River (France). Chemosphere 2019, 219, 1002–1013. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq U.; Danish M.; Lu S.; Naqvi M.; Gu X.; Fu X.; Zhang X.; Nasir M. Synthesis of NZVI@reduced Graphene Oxide: An Efficient Catalyst for Degradation of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane (TCA) in Percarbonate System. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 3219–3236. 10.1007/s11164-016-2821-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Tang P.; Lu S.; Xue Y.; Zhang X.; Qiu Z.; Sui Q. Comparative Studies of H2O2/Fe(II)/Formic Acid, Sodium Percarbonate/Fe(II)/Formic Acid and Calcium Peroxide/Fe(II)/Formic Acid Processes for Degradation Performance of Carbon Tetrachloride. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 344, 453–461. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.03.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K.; Nagatomo S.; Fujinami S.; Furutachi H.; Ogo S.; Suzuki M.; Uehara A.; Maeda Y.; Watanabe Y.; Kitagawa T. A New Mononuclear Iron(III) Complex Containing a Peroxocarbonate Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1202–1205. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart S.; Ember E.; Van Eldik R. Comparative Study of the Catalytic Activity of [MnII(Bpy)2Cl2] and [Mn2III/IV(μ-O)2(Bpy)4](ClO4)3 in the H2O2 Induced Oxidation of Organic Dyes in Carbonate Buffered Aqueous Solution. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 3264. 10.1039/b925160j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J.; Miah Y. A.; Varsani D. S.; Salvadori E.; Sheriff T. S. Selective Oxidative Degradation of Azo Dyes by Hydrogen Peroxide Catalysed by Manganese(II) Ions. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 103372–103381. 10.1039/C6RA23067A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Xu H.; Wang Q.; Li D.; Xia D. Activation Mechanism of Sodium Percarbonate by FeOCl under Visible-Light-Enhanced Catalytic Oxidation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 706, 415–420. 10.1016/j.cplett.2018.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohand S. A.; Muzart J. Oxidation of Alcohols by Sodium Percarbonate Catalyzed by the Association of Potassium Dichromate and a Phase Transfer Agent. Synth. Commun. 1995, 25, 2373–2377. 10.1080/00397919508015440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simunkova M.; Alwasel S. H.; Alhazza I. M.; Jomova K.; Kollar V.; Rusko M.; Valko M. Management of Oxidative Stress and Other Pathologies in Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 2491–2513. 10.1007/s00204-019-02538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X.; Zhang Y.; Guo H.; Hai Y.; Luo Y.; Yue T. Mechanism and Intervention Measures of Iron Side Effects on the Intestine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2113–2125. 10.1080/10408398.2019.1630599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranji-Burachaloo H.; Gurr P. A.; Dunstan D. E.; Qiao G. G. Cancer Treatment through Nanoparticle-Facilitated Fenton Reaction. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 11819–11837. 10.1021/acsnano.8b07635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H.; Shang P. The Significance, Trafficking and Determination of Labile Iron in Cytosol, Mitochondria and Lysosomes. Metallomics 2018, 10, 899–916. 10.1039/C8MT00048D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino K.; Nishina S.; Sasaki K.; Hara Y. Mitochondrial Damage and Iron Metabolic Dysregulation in Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 193–199. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badu-Boateng C.; Naftalin R. J. Ascorbate and Ferritin Interactions: Consequences for Iron Release in Vitro and in Vivo and Implications for Inflammation. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 75–87. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faheem; Du J.; Kim S. H.; Hassan M. A.; Irshad S.; Bao J. Application of Biochar in Advanced Oxidation Processes: Supportive, Adsorptive, and Catalytic Role. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 37286–37312. 10.1007/s11356-020-07612-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo O. M.; Murrieta M. F.; Castañeda L. F.; Nava J. L. Characterization of the Reaction Environment in Flow Reactors Fitted with BDD Electrodes for Use in Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Critical Review. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135373. 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei F.; Vione D. Effect of PH on Zero Valent Iron Performance in Heterogeneous Fenton and Fenton-Like Processes: A Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 3127. 10.3390/molecules23123127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laghrib F.; Bakasse M.; Lahrich S.; El Mhammedi M. A. Advanced Oxidation Processes: Photo-Electro-Fenton Remediation Process for Wastewater Contaminated by Organic Azo Dyes. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020, 10.1080/03067319.2020.1711892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S.; Meyerstein D.; Czapski G. The Fenton Reagents. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1993, 15, 435–445. 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90043-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg A.; Shusterman I.; Kornweitz H.; Meyerstein D. Three H2O2 Molecules Are Involved in the “Fenton-like” Reaction between Co(H2O)62+ and H2O2. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 9111. 10.1039/c4dt00401a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikov A. S.; Kuznetsov M. L.; Pombeiro A. J. L.; Bokach N. A.; Shul’pin G. B. Generation of HO· Radical from Hydrogen Peroxide Catalyzed by Aqua Complexes of the Group III Metals [M(H2O)n]3+ (M = Ga, In, Sc, Y, or La): A Theoretical Study. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1195–1208. 10.1021/cs400155q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kornweitz H.; Burg A.; Meyerstein D. Plausible Mechanisms of the Fenton-Like Reactions, M = Fe(II) and Co(II), in the Presence of RCO2– Substrates: Are OH• Radicals Formed in the Process?. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 4200–4206. 10.1021/jp512826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Xiong Z.; Ruan X.; Xia D.; Zeng Q.; Xu A. Kinetics and Mechanism of Organic Pollutants Degradation with Cobalt–Bicarbonate–Hydrogen Peroxide System: Investigation of the Role of Substrates. Appl. Catal., A 2012, 411–412, 24–30. 10.1016/j.apcata.2011.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S.; Lind J.; Merényi G. Chemistry of Peroxynitrites as Compared to Peroxynitrates. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2457–2470. 10.1021/cr0307087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luc R.; Vergely C. Forgotten Radicals in Biology. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008, 4, 255–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M.-R.; Han J.-H.; Lee H.-J.; Park Y. K.; Kang M.-H. Type 2 Diabetes Model TSOD Mouse Is Exposed to Oxidative Stress at Young Age. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2015, 56, 49–56. 10.3164/jcbn.14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa J. D.; Fuentes-Lemus E.; Dorta E.; Melin V.; Cortés-Ríos J.; Faúndez M.; Contreras D.; Denicola A.; Álvarez B.; Davies M. J.; López-Alarcón C. Quantification of Carbonate Radical Formation by the Bicarbonate-Dependent Peroxidase Activity of Superoxide Dismutase 1 Using Pyrogallol Red Bleaching. Redox Biol. 2019, 24, 101207. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini M. G.; Miyamoto S.; Di Mascio P.; Augusto O. Production of the Carbonate Radical Anion during Xanthine Oxidase Turnover in the Presence of Bicarbonate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 51836–51843. 10.1074/jbc.M406929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A. M.; Zhu J.; Jara-Espejo M.; Burrows C. J. Cruciform DNA Sequences in Gene Promoters Can Impact Transcription upon Oxidative Modification of 2′-Deoxyguanosine. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2616–2626. 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa B.; Munk B. H.; Burrows C. J.; Schlegel H. B. Computational Study of the Radical Mediated Mechanism of the Formation of C8, C5, and C4 Guanine:Lysine Adducts in the Presence of the Benzophenone Photosensitizer. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 1396–1409. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachi A.; Dalle-Donne I.; Scaloni A. Redox Proteomics: Chemical Principles, Methodological Approaches and Biological/Biomedical Promises. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 596–698. 10.1021/cr300073p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. M.; Rempel D. L.; Gross M. L. A Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins (FPOP) Platform for Free-Radical Reactions: The Carbonate Radical Anion with Peptides and Proteins. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 131, 126–132. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapenna D.; Ciofani G.; Cuccurullo C.; Neri M.; Giamberardino M. A.; Cuccurullo F. Bicarbonate-Dependent, Carbonate Radical Anion-Driven Tocopherol-Mediated Human LDL Peroxidation: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Free Radical Res. 2012, 46, 1387–1392. 10.3109/10715762.2012.719613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Cardenas J. A.; Esteban-García B.; Agüera A.; Sánchez-Pérez J. A.; Manzano-Agugliaro F. Wastewater Treatment by Advanced Oxidation Process and Their Worldwide Research Trends. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 170. 10.3390/ijerph17010170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walawska B.; Gluzińska J.; Miksch K.; Turek-Szytow J. Solid Inorganic Peroxy Compounds in Environmental Protection. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2007, 9, 68–72. 10.2478/v10026-007-0057-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muszyńska J.; Gawdzik J.; Sikorski M. The Effect of Sodium Percarbonate Dose on the Reduction of Organic Compounds in Landfill Leachate. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 86, 00002. 10.1051/e3sconf/20198600002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C.; Xu Q.; Zhang H.; Liu Z.; Ren S.; Li H. Enhanced Removal of Coumarin by a Novel O3/SPC System: Kinetic and Mechanism. Chemosphere 2019, 219, 100–108. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo S.; Li D.; Xu H.; Xia D. An Integrated Microwave-Ultraviolet Catalysis Process of Four Peroxides for Wastewater Treatment: Free Radical Generation Rate and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122434. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geng T.; Yi C.; Yi R.; Yang L.; Nawaz M. I. Mechanism and Degradation Pathways of Bisphenol A in Aqueous Solution by Strong Ionization Discharge. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 185. 10.1007/s11270-020-04563-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnárovits L.; Takács E. Radiation Induced Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Waters and Wastewaters. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 50. 10.1007/s41061-016-0050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.; Liu Y.; Lian L.; Li R.; Ma J.; Zhou H.; Song W. Photochemical Formation of Carbonate Radical and Its Reaction with Dissolved Organic Matters. Water Res. 2019, 161, 288–296. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; von Gunten U.; Kim J.-H. Persulfate-Based Advanced Oxidation: Critical Assessment of Opportunities and Roadblocks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3064–3081. 10.1021/acs.est.9b07082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado Ribeiro A. R.; Moreira N. F. F.; Li Puma G.; Silva A. M. T. Impact of Water Matrix on the Removal of Micropollutants by Advanced Oxidation Technologies. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 363, 155–173. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P.; Meng T.; Wang Z.; Zhang R.; Yao H.; Yang Y.; Zhao L. Degradation of Organic Micropollutants in UV/NH2Cl Advanced Oxidation Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 9024–9033. 10.1021/acs.est.9b00749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.; Liu T.; Zhang D.; Yin K.; Wang D.; Zhang W.; Liu C.; Yang C.; Wei Y.; Wang L.; Luo S.; Crittenden J. C. The Individual and Co-Exposure Degradation of Benzophenone Derivatives by UV/H2O2 and UV/PDS in Different Water Matrices. Water Res. 2019, 159, 102–110. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataineh H.; Pestovsky O.; Bakac A. pH-Induced Mechanistic Changeover from Hydroxyl Radicals to Iron(IV) in the Fenton Reaction. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 1594. 10.1039/c2sc20099f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]