Abstract

Owing to the energetic cost associated with CO2 release in carbon capture (CC), the combination of carbon capture and recycling (CCR) is an emerging area of research. In this approach, “captured CO2,” typically generated by addition of amines, serves as a substrate for subsequent reduction. Herein, we report that the reduction of CO2 in the presence of morpholine (generating mixtures of the corresponding carbamate and carbamic acid) with a well-established Mn electrocatalyst changes the product selectivity from CO to H2 and formate. The change in selectivity is attributed to in situ generation of the morpholinium carbamic acid, which is sufficiently acidic to protonate the reduced Mn species and generate an intermediate Mn hydride. Thermodynamic studies indicate that the hydride is not sufficiently hydritic to reduce CO2 to formate, unless the apparent hydricity, which encompasses formate binding to the Mn, is considered. Increasing steric bulk around the Mn shuts down rapid homolytic H2 evolution rendering the intermediate Mn hydride more stable; subsequent CO2 insertion appears to be faster than heterolytic H2 production. A comprehensive mechanistic scheme is proposed that illustrates how thermodynamic analysis can provide further insight. Relevant to a range of hydrogenations and reductions is the modulation of the hydricity with substrate binding that makes the reaction favorable. Significantly, this work illustrates a new role for amines in CO2 reduction: changing the product selectivity; this is pertinent more broadly to advancing CCR.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The catalytic reduction of CO2 to fuels and fuel precursors such as CO, formic acid (FA), and MeOH represent recycling efforts pertinent to future energy schemes.1,2 The coupling of this to carbon capture (CC) in a carbon capture and recycling (CCR) scheme offers a promising approach for mitigation of global warming and development of carbon-neutral fuels.3,4 Presently, CC relies on the reaction of CO2 with amines to give equilibrium mixtures of carbamic acid, carbamate, and bicarbonate (if water is present). The captured CO2 is then released to serve as a substrate for recycling efforts. This process is not without challenges, including the cost associated with the release of CO2; using alkanolamines, it is estimated that to capture and release all the CO2 from a powerplant, one would consume 25–40% of the energy output.3,5 As such, there is much interest in developing more robust and energy-efficient CC technologies.6–9 An alternative approach is to circumvent CO2 release in CCR efforts,10 hence using the captured CO2 (carbamate/carbamic acid) as a substrate for reduction.

The idea of using captured CO2 as a substrate is gaining traction, though studies remain limited. Sanford,11 we,12 and others10,13–16 have shown that a carbamate can be hydrogenated to MeOH, likely via release of CO2 under the reaction conditions. With regards to CO2 reduction, Ishitani established that in the presence of triethanolamine (TEOA),17 both photo-18 and electrocatalytic19 reduction of CO2 to CO is accelerated at a Re catalyst. TEOA coordinates to the Re and CO2 inserts into the alkoxide to generate a Re-carbonate species; how subsequent reduction from this species occurs is not known. Fujita also found that TEOA enhances photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to formate with a Ru catalyst;20 it is proposed that a zwitterionic alkylcarbonate lowers the kinetic barriers of several key steps. In contrast to Ishitani’s system, coordination of the carbonate is not thought to be relevant to the reduction. These examples make use of the direct interaction of amines or the alcohol functionality of alkanolamines with CO2 and hence are pertinent to a combined CCR approach.

Amines can also facilitate the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 without directly interacting with CO2. Costentin and Nocera have shown that the binding of an amine to an Fe porphyrin catalyst allows more facile protonation of a bound CO2 to give formate.21 Marinescu has shown that pendent amines can hydrogen bond and stabilize a Co-COOH intermediate.22 Finally, Baik, Skrydstrup, and Daasbjerg have shown that pendent amines on a Mn electrocatalyst enhance formation of an intermediate Mn–H, allowing for reduction to give formate over CO.23 These studies illustrate how amines, present in CC, may enhance electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 indirectly.

Herein, we investigate the role of added amine on the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. This study makes use of two Mn catalysts of the type (N^N)Mn(CO)3X whereby N^N is a bipyridine ligand (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine; mesbpy = 6,6′-dimesityl-2,2′-bipyridine) and X is an X-type ligand.24–26 These complexes are chosen because they show excellent Faradaic efficiency (FE) for electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO, and numerous studies provide a detailed understanding of the mechanisms for this transformation.24,25,27–36 We find that in the presence of an amine, the product selectivity shifts from CO to mixtures of H2 and FA. Mechanistic and thermochemical studies indicate that the amine generates a more acidic environment, allowing for a Mn–H to be a kinetically competitive intermediate (relative to the hydroxycarbonyl, Mn-COOH, formed en route to CO production). Investigation of the two complexes that differ in the steric bulk of the ligands shows that when bimetallic H2 production is feasible, this reactivity supersedes that with CO2, and H2 is the dominant product. When a bimetallic pathway for H2 evolution is not possible, CO2 insertion into the Mn–H bond to give a formate species, Mn-OCHO, is faster than protonation of Mn–H to give H2 and a Mn(I) species. This work provides the first thermochemical analysis of a Mn electrocatalyst, which aids in understanding how the product selectivity can be tuned. We find that the free energy associated with binding of formate to the catalyst must be considered. Moreover, this work establishes a new role for amines in combined CCR which is that of controlling the selectivity of the reaction.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Synthesis and Characterization of Mn Complexes.

The formally Mn(I) species (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN,37 [(bpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)][OTf],38 (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br,26 and [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)][OTf]26 were all prepared following literature procedures. The 2-electron reduced congeners that are formally Mn(-I), [(bpy)Mn(CO)3][Na], and [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3][Na] were prepared by slight modification of literature procedures;26,38 we found that using Na/Hg as a reductant as opposed to KC8 gave identical results and allowed us to use a safer reductant (see SI).

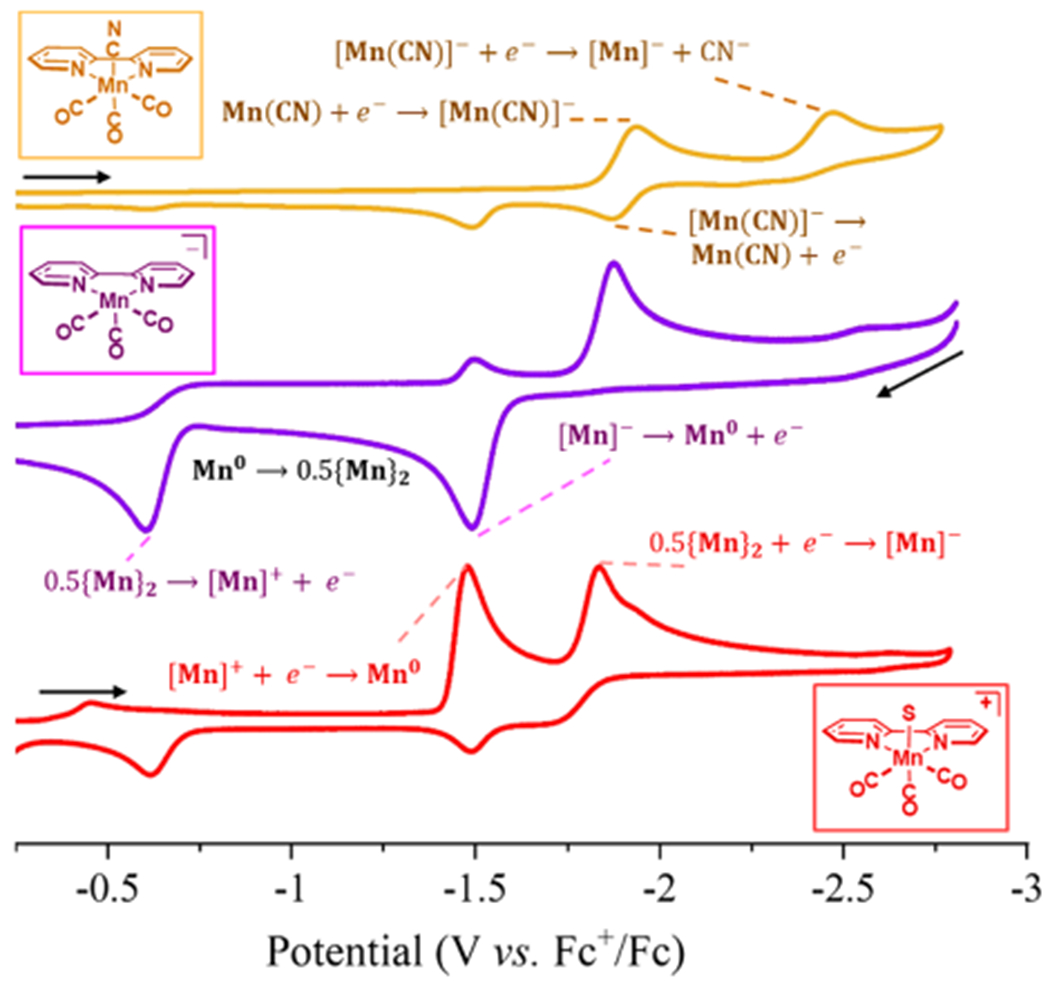

To gain insight into the electrochemical reactions, the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of the two anionic Mn(-I) species were collected in MeCN with 0.1 M TBAPF6 electrolyte and referenced versus Fc+/0.

The CV of anionic [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3][Na] shows a single 2-electron oxidation centered at −1.57 (±0.01) V (See SI). The electrochemical response is consistent with the Mn(0) species not undergoing any chemical reaction such as dimerization at the electrode and is similar to the reported 2-electron reduction of cationic [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)][OTf] (reported at −1.55 V).35

By contrast, the CV of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3][Na] shows two irreversible oxidations at −1.47 (±0.01) V and −0.61 V and two ireversible reductions at −1.49 (±0.01) V and −1.87 V (Figure 1, purple). The oxidation at −1.47 V is assigned to the one-electron oxidation of Mn(-I) to Mn(0). The Mn(0) species is known to dimerize very rapidly,27,39 which occurs before the Mn(0) can be fully oxidized to the Mn(I). Evidence for the dimerization is in the second oxidation at −0.61 V, which corresponds to the oxidation of {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2 to [(bpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+.25

Figure 1.

CVs of 1 mM (top orange): (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN; (middle purple): [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]−; and (bottom red): [(bpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+ in 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN solvent, with a scanrate of 0.1 V/s. S designates a coordinated solvent molecule. Scan directions and starting potentials are indicated by the black arrows. The electrochemical reactions that are occurring are shown; unless labeled, the reactions that occur at the same potentials correspond to the same reaction. The Mn(0) is unstable in solution and dimerizes once it is formed.

On the return reductive scan, the reduction at −1.49 V corresponds to the one electron reduction of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+ to give (bpy)Mn(CO)3, which dimerizes in solution to give {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2. This interpretation is confirmed by examining the first cathodic scan of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+ which also features a reduction at −1.49 V (Figure 1, red) to give (bpy)Mn(CO)3. The Mn(0) complex dimerizes to {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2 before the second reduction can occur, and hence the reduction at −1.87 V corresponds to the reduction of the dimer to [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]−. Additionally, if the switching potential in the CV of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3][Na] is set to −1.0 V, therefore precluding oxidation of the dimer to the cation, then the only reductive peak observed is that at −1.87 V, corresponding to the reduction of the dimer. From the above analysis, the 2-electron reduction of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+ is taken to be −1.48 V.

The CVs are similar to that of (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN, in that, redox events associated with the dimer are present (Figure 1, top), and monomer redox events are shifted due to coordination of cyanide.25 It is prudent to point out that the reduction of {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2 to give anionic [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]− occurs at a very similar potential to the reduction of (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN to the neutral Mn(0) (vide infra).

B. Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2.

Given that (bpy)Mn(CO)3X (X = Br, CN)24,25 and [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)][OTf]26 are electrocatalysts that reduce CO2 to CO in the presence of weak acids, we sought to determine if addition of an amine would have a positive effect on the catalysis. Under an atmosphere of CO2, morpholine gives an equilibrium mixture of the corresponding carbamic acid and carbamate (Scheme 1); reduction at a carbon electrode occurs with minimal electrode fouling.40 Given that the pKa of morpholinium (morph-H+) is 16.6 in MeCN,41 the pKa of morph-COOH is estimated to be ~ 17. Thus, morpholine was chosen as an additive to the electrocatalytic conditions to see if the resulting carbamic acid or carbamate may serve as a substrate (see SI for studies with TEOA and DEA).

Scheme 1.

Equilibrium between morpholine and CO2

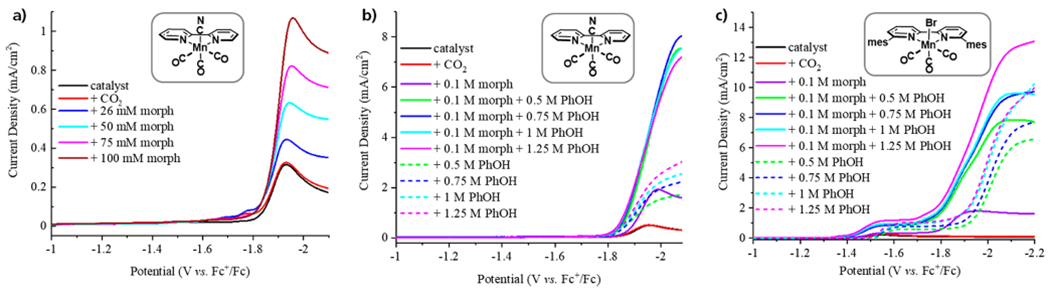

As reported by Kubiak, (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN electrocatalytically reduces CO2 to CO at −1.94 V in the presence of PhOH.25 We have replicated these results, obtaining very similar current densities (Figure 2b, dashed). Subsequently, we investigated the effect of morpholine on this electrocatalyst. The CV of 1 mM (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN under CO2 in the presence of 0.1 M morpholine and CO2 shows a catalytic current at −1.96 V (Figure 2b, purple). The subsequent addition of PhOH (0.5 M – 1.25 M final concentration) shows a 16-fold enhancement of the current, indicating a synergistic effect on the catalytic current (Figure 2b). The resulting morph-COOH and morph-H+ are more acidic than PhOH (pKa = 29.1 in MeCN)42 which suggests that it may serve as the proton source.

Figure 2.

CVs (100 mV/s) of the catalysts (1 mM) in the presence of CO2 and the additives noted in the legends. For clarity, the return oxidation current is not shown. (a) Effect of increasing morpholine on the catalysis of (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN. (b) Effect of increasing PhOH on the catalysis of (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN in the presence and absence of morpholine. (c) Effect of increasing PhOH on the catalysis of (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br in the presence and absence of morpholine.

Indeed, the CVs of 1 mM (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN in the presence of various equiv of morpholine under a CO2 atmosphere show a catalytic current at the same onset potential as when PhOH is present. The addition of morpholine is limited by the poor solubility of the morpholinium carbamate species beyond 0.1 M in MeCN.40 With the addition of 0.1 M morpholine, the catalyst shows a 3.5-fold current enhancement (Figure 2a).

In all instances, catalysis occurs at the same onset potential. This suggests that the limiting reduction is the same in the presence and absence of morpholine. Kubiak suggests that catalysis with (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN ensues from a rate-limiting disproportionation of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3CN]− which after CN loss generates the active [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]−.25 However, our CV studies indicate that the reduction of the dimer occurs at a very similar potential (Figure 1) and coupled to the low concentration of cyanide in solution suggests that reduction of the dimer to the anion may be limiting, as proposed for (R-bpy)Mn(CO)3Br.24,34 This latter scenario may be more likely in controlled potential electrolysis experiments, whereby the solution is stirred.

The CVs in the presence of CO2, PhOH, and morpholine were repeated with (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br which does not undergo dimerization. In the presence of PhOH (and no morpholine), the resulting CVs (Figure 2c) are similar to those obtained when MeOH is used as the proton source.26 Upon addition of morpholine, several changes are observed. First, the initial plateau current shifts ~100 mV more positive. This initial plateau represents slow catalysis. In the presence of CO2 and MeOH26 (or PhOH), the plateau is anodically shifted relative to the reduction of [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+ because of binding and protonation of CO2. The shift is noticeably more pronounced in the presence of morpholine which may suggest that a different electrophilic species such as morph-COOH is binding to the reduced Mn (EC mechanism). Alternatively, the shift may be due to reduction of a species such as (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OOC-morph) that would form if morph-COO− first binds the oxidized Mn (CE mechanism). Next, the catalytic current density at ~ −2 V is enhanced with the addition of morpholine, and the onset of this catalytic wave is shifted ~100 mV more positive.

To establish the product distribution from CO2 reduction, controlled potential electrolysis (CPE) was carried out under CO2 with the conditions given in Table 1. Consistent with literature precedence, in the presence of only the weak acid PhOH, (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN and (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br produce CO exclusively from CO2 (entries 2 and 6).25,26,43 When both morpholine and PhOH are present, (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN primarily makes H2 with very little CO (entry 3), and in the presence of only morpholine (entry 1), H2 and FA are produced. Using (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br as a catalyst gives twice as much FA as H2 (entries 5, 7) when morpholine is present.

Table 1.

Product Distribution from Controlled Potential Electrolysis under the Conditions Specifiedd

| Entry | Catalysta | Additivea | (H2+FA):COb | H2:FAb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN | 0.1 M morph | 90.5:9.5 | 66:34 |

| 2 | (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN | 0.5 M PhOH | 4:96 | 1:0 |

| 3 | (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN | 0.1 M morph 0.5 M PhOH | 97:3 | 1:0 |

| 4 | (bpy)Mn(CO)3CN | 0.1 M [morph-H] [BF4]c | 1:0 | 1:0 |

| 5 | (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br | 0.1 M morph | 44:56 | 31:69 |

| 6 | (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br | 0.5 M PhOH | 0:1 | |

| 7 | (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br | 0.1 M morph 0.5 M PhOH | 96:4 | 34:66 |

| 8 | (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br | 0.1 M [morph-H] [BF4]c | 1:0 | 1:0 |

| 9 | (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br | 0.1 M TEOA | 0:1 | -- |

While it is not known whether CO2 or carbamic acid is the substrate, the addition of morpholine changes the product selectivity from CO to H2 and FA, representing a new role of amines in a combined CCR scheme. Related Mn catalysts that feature pendent amines show a similar shift in the product selectivity.23 However, the approach here, whereby added amines change the product selectivity, also has the potential to concentrate the CO2, yielding higher current densities;44 this is particularly attractive for developing catalysts that function in water.45

Catalysts of the type (bpy)Mn(CO)3X (X = Br, CN) have been shown to photochemically reduce CO2 to mixtures of FA, CO, and H2 with a Ru photosensitizer and TEOA.46,47 However, the Ru photosensitizer employed itself can reduce CO2 to formic acid in the presence of TEOA, albeit with reduced turnover numbers.47 When TEOA is used as a CO2-capturing agent and proton source for electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 with (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br, only CO is produced (Table 1, entry 9).

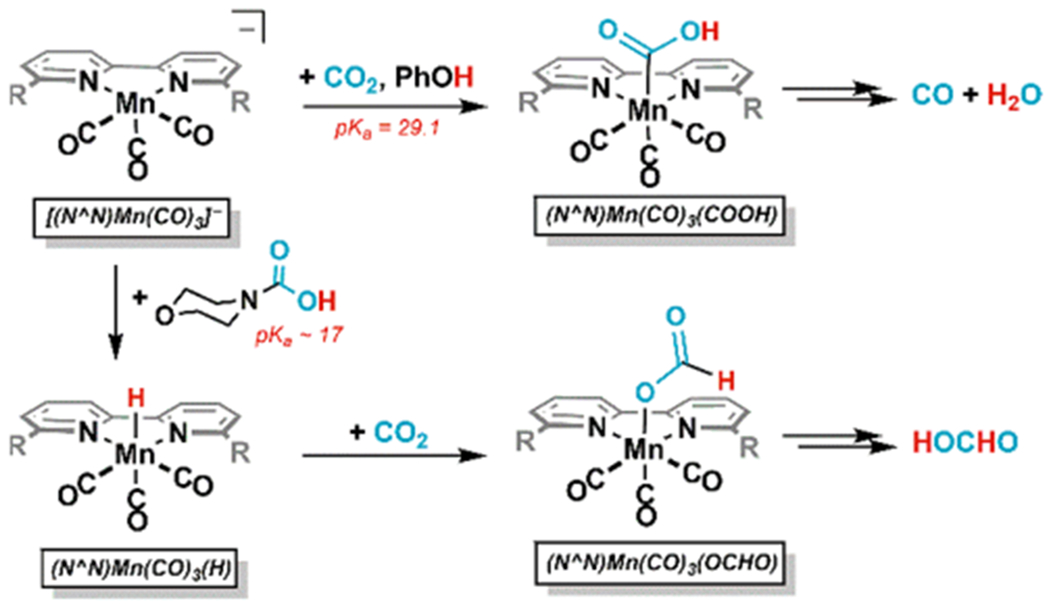

H2 evolution from [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(MeCN)]+ is known to occur with stronger acids.48 Given that all experiments with morpholine and CO2 give some H2, it is likely that the morpholine aids in the production of a Mn–H intermediate (Scheme 2). Indeed, CPE under N2 and morpholinium solely gives H2 (Table 1, entries 4, 8). As morph-COOH is estimated to have a similar pKa to morpholinium, the morph-COOH, generated in situ likely protonates [(N^N)Mn(CO)3]− to give the intermediate (N^N)Mn(CO)3H. The morpholinium may then protonate the formate to generate free FA. It should be emphasized that either morph-H+ or morph-COOH may serve as the acid in these reactions.

Scheme 2.

Effect of Acid on the Product Distribution of CO2 Reduction

In the absence of morpholine, the only acid present is PhOH, which is not sufficiently acidic to generate the hydride. Rather, the anionic Mn binds CO2 in the presence of PhOH to give a hydroxycarbonyl intermediate en route to CO production (Scheme 2). The higher current densities observed with both morpholine and PhOH may be due to facilitation of proton-transfer to the bound CO2 or different products being formed.22,49

C. Characterization and Reactivity of (N^N)Mn(CO)3H.

To corroborate that H2 is produced from (N^N)Mn(CO)3H, the preparation of the hydrides via protonation of the corresponding anions was undertaken.

Treatment of [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]− with 5 equiv of PhOH in CD3CN results in rapid precipitation and a color change to dark red. After 4 min, the major Mn species in solution is the dimer, {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2 (Scheme 3). A small resonance at −3.02 ppm is consistent with formation of (bpy)Mn(CO)3H,50 and H2 is observed at 4.57 ppm. As described in the literature, the hydride is not stable and fully converts to the dimer50 upon losing H2. IR analysis of the precipitate indicates that it is comprised of {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2. Attempts to intercept the hydride by addition of CO2 to a thawing solution of in situ generated (bpy)Mn(CO)3H to give a Mn-OCHO species were unsuccessful; the only product obtained was {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2 (see SI).

Scheme 3.

Observed Reactivity of (N^N)Mn(CO)3(H)

Taken together, this suggests that a homolytic pathway for H2 formation is operative, whereby two (bpy)Mn(CO)3H react to lose H2 (Scheme 3, top). To determine if a heterolytic pathway is also present, whereby the intermediate (bpy)Mn(CO)3H is protonated by PhOH in solution, [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]− was treated with 20 equiv of PhOH. If a heterolytic pathway occurred at a competitive rate, then a Mn(I) species should result. The NMR spectrum of this reaction instead showed only resonances of the dimer, indicating that the heterolytic pathway is not competitive.

Given that the mechanism for H2 production from [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]− is homolytic, it was anticipated that the corresponding (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H may be more stable, as the steric bulk precludes dimerization. NMR analysis of the reaction of [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3]− with 5 equiv of PhOH shows a new set of resonances consistent with (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H that persist over several hours. Indeed, addition of CO2 results in a reaction that gives (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO). This was confirmed by independent synthesis of (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) (see SI). A related (N^N)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) complex has recently been reported in the literature.51

Over time, the hydride resonance at −2.83 ppm disappears as H2 is produced, and a new set of resonances consistent with a Mn(I) species assigned as (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OPh) emerges (Scheme 3). This assignment was corroborated by independent synthesis of the phenolate species. If NaBr is present in solution, then (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br is also observed. The formation of Mn(I) species suggests that heterolytic H2 production is occurring.

The observation that PhOH can protonate the anionic species suggests that formate and/or H2 could be produced in experiments whereby only PhOH and CO2 are added. Only CO is produced under those conditions which suggests that the kinetics associated with initial CO2 binding are more favorable than those of protonation, as has been observed on an analogous Re system.52

D. Thermodynamic Analysis.

As the Mn catalysts can produce both FA and H2, it is of interest to determine the hydricity of the resulting hydrides. As shown in Scheme 4, the hydricity can be obtained from knowledge of the pKa of (N^N)Mn(CO)3H and the reduction potentials.53

Scheme 4.

Thermochemical cycle for determination of the hydricity of (N^N)Mn(CO)3H. For simplicity, (N^N)Mn(CO)3 is abbreviated as Mn

The free energy change associated with hydride formation in MeCN (eq 4) is known,53 and those associated with eqs 1–3 for the two complexes have been measured and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the Thermochemical Properties for the Two Catalysts

| Thermochemical parameter | (bpy)Mn(CO)3H | (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H |

|---|---|---|

| pKa (experimental) | 28.8 (±0.8) | 28.5 ± 0.9 |

| apKa (extrapolated) | 26.4 (±0.1) | 28.0 (±0.2) |

| a | −1.48 (±0.01) V | −1.57 (±0.01) V |

| b | −1.48 (±0.01) V | −1.57 (±0.01) V |

| 50.7 (±1.1) kcal·mol−1 | 46.1 (±1.3) kcal·mol−1 | |

| d | 47.5 (±0.4) kcal·mol−1 | 45.4 (±0.4) kcal·mol−1 |

The pKas of both Mn–H species were obtained from titrations of [(N^N)Mn(CO)3]− with various equivalents of PhOH (see SI). From this equilibrium and the known pKa of PhOH (29.1 in MeCN),42 pKa values of 28.8 ± 0.8 and 28.5 ± 0.9 are obtained for (bpy)Mn(CO)3H and (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H, respectively. It should be noted that the measured pKas are consistent with the observed reactivity described in the previous section of the anions toward PhOH. The titrations are done at early time points before the subsequent reactions can shift the equilibrium. Due to the instability of (bpy)Mn(CO)3H toward dimerization and H2 loss, the pKa was also estimated from a plot of pKa versus reduction potential (see SI),54 which gives a linear fit across several transition metal hydride species. The analysis provides a pKa value of 26.4 ± 0.1 for (bpy)Mn(CO)3H, indicating that the instability of (bpy)Mn(CO)3H increases the apparent pKa. Repeating the analysis with (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H provides a pKa value that is within error of the experimental value (Table 2), validating the approach to extrapolate the pKa for this system.

A combination of the 2-electron reduction potential of [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3]+ with the measured pKa of (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H gives a hydricity value of 46.1 ± 1.3 kcal·mol−1, in agreement with the value obtained using the extrapolated pKa. The hydricity of formate in MeCN is 44 kcal·mol−1 (Scheme 5 and caption),55 and hence the hydride transfer reaction is endergonic by ~2.1 kcal·mol−1 (eq 7 of Scheme 5). However, the reaction of eq 7 is not the reaction that is observed, as it gives [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3]+ and OCHO−. Instead, the CO2 inserts to give (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO), and hence the free energy change of the observed reaction (eq 9) must be considered. This analysis encompasses the free energy change associated with hydride transfer (eq 7) and binding of the formate to the cationic Mn (eq 8) to give the apparent hydricity. Because eq 9 is favorable, the free energy of binding formate to the Mn must be < −2.1 kcal·mol−1 (eq 8). This value was compared favorably to the value we measured of −3.7 kcal·mol−1 for formate binding to a cationic Ru species.12 The modulation of hydricity by the binding of a ligand after hydride has been observed in both water and THF solvent.12,56

Scheme 5. Thermochemical Equations Pertinent to Formate Productiona.

aFor simplicity, (N^N)Mn(CO)3 is abbreviated as Mn. Except for eq 6, free energy values are provided for N^N = mesbpy (bpy). The hydricity of formate under the conditions presented may differ slightly, given that we are not operating at 1 atm of CO2, and that the high concentrations of morpholine and PhOH may alter the CO2 solubility.

Given that morph-H is more acidic than FA (pKa = 20.7),57 the end product of reduction is FA and not formate. The FA could be directly protonated off from (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) (Scheme 6), or formate release may ensue upon reduction, which is then protonated by morph-H (Scheme 7). Given the differences in pKas of FA and morph-H (eqs 10–11) for direct protonation of the formate, the free energy associated with formate binding to the Mn must be greater than −5.6 kcal·mol−1 (eq 12). As the upper-limit for this value is −2.1 kcal·mol−1 (eq 8), direct protonation of bound formate in (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) may be feasible.

Scheme 6. Thermochemical Equations Pertinent to Direct Protonation of the Bound FormateA.

AFor simplicity, (N^N)Mn(CO)3 is abbreviated as Mn. Free energies are in units of kcal·mol−1.

Scheme 7. Proposed Mechanisms for the Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to Give CO (Top) or FA (Bottom)a.

aH2 production is indicated by gray arrows, and the stoichiometry shown is for the heterolytic pathway. Direct protonation of Mn(OCHO) is indicated by light purple arrows, and reduction followed by formate loss is indicated by dark purple arrows.

Following Scheme 4, the hydricity of (bpy)Mn(CO)3H is found to be 47.5 ± 0.4 kcal·mol−1. Because of the error in the experimentally measured pKa, this analysis uses the extrapolated pKa (Table 2). Comparison of the hydricity values indicates that (bpy)Mn(CO)3H is ~ 2 kcal·mol−1 less hydridic than (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H (in comparing the hydricities obtained from the extrapolated pKa).

Formate production from (bpy)Mn(CO)3H is unfavorable by 3.5 kcal·mol−1. For the reaction that gives (bpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) to be favorable, the binding of formate must be < −3.5 kcal/mol (eq 8). Though we have not been able to prepare this complex via CO2 insertion into (bpy)Mn(CO)3H, we attribute the lack of observed insertion to kinetics (insufficient gas-mixing), not thermodynamics, as (bpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) can be prepared by alternative means (see SI). The limit for formate binding does not allow to distinguish between formate loss from (bpy)Mn(CO)3(OCHO) occurring from direct protonation or reduction.

The product distributions of the CPE can be understood in terms of the kinetics and thermodynamics associated with the intermediate Mn–H (Scheme 7). In the absence of morpholine, the only acid capable of protonating [(N^N)Mn(CO)3]− is PhOH. From the difference in pKas, this reactivity is unfavorable by ~3.7 and 0.8 kcal·mol−1 for [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]− and [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3]−, respectively. Hence, the CO2 coordinates, and the resulting CO2 is protonated to give the hydroxycarbonyl species that ultimately provides CO (Scheme 7, top).

In the presence of morpholine, morph-COOH forms and can serve as an acid with a pKa of ~ 17. Now this acid can protonate both [(N^N)Mn(CO)3]− species to (N^N)Mn(CO)3H. The hydride can then insert CO2 to give formate, be protonated to give H2 and (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3X, or dimerize to give H2 and {(bpy)Mn(CO)3}2. In all instances, reduction back to the anion closes the catalytic cycle.

As shown in Figure 3, the binding of formate can modulate the apparent hydricity, allowing FA to be produced with catalysts that otherwise would not be expected to reduce CO2 to FA. H2 and FA are always observed due to thermodynamics. The plot of hydricity versus pKa indicates that the minimum pKa of added acid to exclusively produce formate (and not H2) is ~24.55 Given that the pKas of the hydrides are ~ 26-28, for selective formate production, a carbamic acid with a pKa between 24 and 26-28 would need to be employed. The analysis assumes that the apparent hydricity of the hydrides is 44 kcal·mol−1; the range is likely smaller because the apparent hydricity and pKa combination must remain above the pink line. Acids with pKas larger than those of the hydrides are not sufficient to generate the hydrides. Hence, addition of PhOH or TEOA (pKa = 34.9)20 instead results in exclusive reduction of CO2 to CO. Figure 3 clearly shows the boundaries for generation of CO, formate, FA, and H2.

Figure 3.

Plot of hydricity versus pKa in MeCN. Solid lines represent boundaries for the speciation (boxed). Location of (N^N)Mn(CO)3H are shown, with the downward arrow indicating how the hydricity is modulated by formate binding. Formate is only obtained in the gray triangle. Product distributions are shown along the x-axis as a function of pKa. For FA, formate, and H2, the hydricity or apparent hydricity must be sufficient enough to obtain the products.

CONCLUSIONS

A thorough thermochemical and mechanistic study that describes the catalytic reactivity of [(NAN)Mn(CO)3]− toward CO2 in the presence of morpholine was presented. It was found that inclusion of morpholine to the catalytic system changes the product selectivity from CO to H2 and FA. The change is due to increasing the acidity of the solution, allowing an intermediate hydride to form. This conclusion was corroborated by taking into account the pKas of (N^N)Mn(CO)3H and reactivity studies of the hydrides. Despite numerous reports on catalysts of the type [(N^N)Mn(CO)3]−, this is the first study to measure the thermodynamic parameters, which allows for additional insight to be gleaned. Of significance is that both (NAN)Mn(CO)3H are not sufficiently hydridic to reduce CO2 despite the production of FA. This finding underscores the importance of formate binding to the catalyst, which serves to increase the apparent hydricity of the catalyst.

It was found that H2 is favored over FA with [(bpy)Mn(CO)3]−, which is attributed to fast kinetics associated with homolytic H2 production. When only heterolytic H2 production is feasible, FA is favored over H2, as exemplified with [(mesbpy)Mn(CO)3]−. The different reactivity is despite (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3H being more hydridic than (bpy)Mn(CO)3H. This emphasizes how different mechanisms can have different kinetics: the importance of tuning the catalyst for modulating the product selectivity.

A mechanistic scheme that is consistent with all observations is presented. In this system, the added amine changes the product selectivity and hence highlights a new role for amines in combined CCR systems. The hydricity of the Mn–H species is not sufficient to reduce CO2 to formate which underscores the importance of instead considering the apparent hydricity, which takes into account the binding of the product to the metal. This finding is broadly applicable to hydrogenation and reduction reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge start-up funding from the University of Utah & USTAR, ACS PRF 57058-DNI3, and NSF CAREER (1945646). NMR results included in this report were recorded at the David M. Grant NMR Center, a University of Utah Core Facility. Funds for construction of the Center and the helium recovery system were obtained from the University of Utah and the National Institutes of Health awards 1C06RR017539–01A1 and 3R01GM063540–17W1, respectively. NMR instruments were purchased with support of the University of Utah and the National Institutes of Health award 1S10OD25241–01. We acknowledge Dr. Stacey J. Smith and BYU for the use of their single crystal X-ray instrumentation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c07763.

All experimental details, including syntheses, spectroscopic data, equilibrium plots, and electrochemical data (PDF)

Crystallographic data (CIF)

Crystallographic data (CIF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.0c07763

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Moumita Bhattacharya, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, United States.

Sepehr Sebghati, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, United States.

Ryan T. VanderLinden, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, United States.

Caroline T. Saouma, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Wang W-H; Himeda Y; Muckerman JT; Manbeck GF; Fujita E CO2 Hydrogenation to Formate and Methanol as an Alternative to Photo- and Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 12936–12973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Appel AM; Bercaw JE; Bocarsly AB; Dobbek H; DuBois DL; Dupuis M; Ferry JG; Fujita E; Hille R; Kenis PJA; Kerfeld CA; Morris RH; Peden CHF; Portis AR; Ragsdale SW; Rauchfuss TB; Reek JNH; Seefeldt LC; Thauer RK; Waldrop GL Frontiers, Opportunities, and Challenges in Biochemical and Chemical Catalysis of CO2 Fixation. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 6621–6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Olah GA; Prakash GKS; Goeppert A Anthropogenic Chemical Carbon Cycle for a Sustainable Future. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 12881–12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gasser T; Guivarch C; Tachiiri K; Jones CD; Ciais P Negative emissions physically needed to keep global warming below 2 °C. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 7958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Haszeldine RS Carbon Capture and Storage: How Green Can Black Be? Science 2009, 325, 1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Vitillo JG Introduction: Carbon Capture and Separation. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 9521–9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sumida K; Rogow DL; Mason JA; McDonald TM; Bloch ED; Herm ZR; Bae T-H; Long JR Carbon Dioxide Capture in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 724–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zeng S; Zhang X; Bai L; Zhang X; Wang H; Wang J; Bao D; Li M; Liu X; Zhang S Ionic-Liquid-Based CO2 Capture Systems: Structure, Interaction and Process. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 9625–9673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Heldebrant DJ; Koech PK; Glezakou V-A; Rousseau R; Malhotra D; Cantu DC Water-Lean Solvents for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture: Fundamentals, Uncertainties, Opportunities, and Outlook. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 9594–9624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kothandaraman J; Goeppert A; Czaun M; Olah GA; Prakash GKS Conversion of CO2 from Air into Methanol Using a Polyamine and a Homogeneous Ruthenium Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 778–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rezayee NM; Huff CA; Sanford MS Tandem Amine and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1028–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mathis CL; Geary J; Ardon Y; Reese MS; Philliber MA; VanderLinden RT; Saouma CT Thermodynamic Analysis of Metal–Ligand Cooperativity of PNP Ru Complexes: Implications for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol and Catalyst Inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 14317–14328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Khusnutdinova JR; Garg JA; Milstein D Combining Low-Pressure CO2 Capture and Hydrogenation To Form Methanol. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 2416–2422. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kar S; Sen R; Kothandaraman J; Goeppert A; Chowdhury R ; Munoz SB; Haiges R; Prakash GKS Mechanistic Insights into Ruthenium-Pincer-Catalyzed Amine-Assisted Homogeneous Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 3160–3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Everett M; Wass DF Highly productive CO2 hydrogenation to methanol – a tandem catalytic approach via amide intermediates. Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 9502–9504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kar S; Sen R; Goeppert A; Prakash GKS Integrative CO2 Capture and Hydrogenation to Methanol with Reusable Catalyst and Amine: Toward a Carbon Neutral Methanol Economy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 1580–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Morimoto T; Nakajima T; Sawa S; Nakanishi R; Imori D; Ishitani O CO2 Capture by a Rhenium(I) Complex with the Aid of Triethanolamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16825–16828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Nakajima T; Tamaki Y; Ueno K; Kato E; Nishikawa T; Ohkubo K; Yamazaki Y; Morimoto T; Ishitani O Photocatalytic Reduction of Low Concentration of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13818–13821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kumagai H; Nishikawa T; Koizumi H; Yatsu T; Sahara G; Yamazaki Y; Tamaki Y; Ishitani O Electrocatalytic reduction of low concentration CO2. Chemical Science 2019, 10, 1597–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Sampaio RN; Grills DC; Polyansky DE; Szalda DJ; Fujita E Unexpected Roles of Triethanolamine in the Photochemical Reduction of CO2 to Formate by Ruthenium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 2413–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Margarit CG; Asimow NG; Costentin C; Nocera DG Tertiary Amine-Assisted Electroreduction of Carbon Dioxide to Formate Catalyzed by Iron Tetraphenylporphyrin. ACS Energy Letters 2020, 5, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chapovetsky A; Welborn M; Luna JM; Haiges R; Miller TF; Marinescu SC Pendant Hydrogen-Bond Donors in Cobalt Catalysts Independently Enhance CO2 Reduction. ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4, 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rønne MH; Cho D; Madsen MR; Jakobsen JB; Eom S ; Escoudé É; Hammershøj HCD; Nielsen DU; Pedersen SU ; Baik M-H; Skrydstrup T; Daasbjerg K Ligand-Controlled Product Selectivity in Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Reduction Using Manganese Bipyridine Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 4265–4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bourrez M; Molton F; Chardon-Noblat S; Deronzier A [Mn(bipyridyl)(CO)3Br]: An Abundant Metal Carbonyl Complex as Efficient Electrocatalyst for CO2 Reduction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 9903–9906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Machan CW; Stanton CJ; Vandezande JE; Majetich GF; Schaefer HF; Kubiak CP; Agarwal J Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide by Mn(CN)(2,2′-bipyridine)(CO)3: CN Coordination Alters Mechanism. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 8849–8856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sampson MD; Nguyen AD; Grice KA; Moore CE; Rheingold AL; Kubiak CP Manganese Catalysts with Bulky Bipyridine Ligands for the Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide: Eliminating Dimerization and Altering Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 5460–5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Riplinger C; Sampson MD; Ritzmann AM; Kubiak CP; Carter EA Mechanistic Contrasts between Manganese and Rhenium Bipyridine Electrocatalysts for the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 16285–16298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).McKinnon M; Belkina V; Ngo KT; Ertem MZ; Grills DC ; Rochford J An Investigation of Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction Using a Manganese Tricarbonyl Biquinoline Complex. Front. Chem 2019, 7, 628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Agarwal J; Shaw TW; Schaefer HF; Bocarsly AB Design of a Catalytic Active Site for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction with Mn(I)-Tricarbonyl Species. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 5285–5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Singh KK; Siegler MA; Thoi VS Unusual Reactivity of a Thiazole-Based Mn Tricarbonyl Complex for CO2 Activation. Organometallics 2020, 39, 988–994. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Rao GK; Pell W; Korobkov I; Richeson D Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 using Mn complexes with unconventional coordination environments. Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 8010–8013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Franco F; Pinto MF; Royo B; Lloret-Fillol J A Highly Active N-Heterocyclic Carbene Manganese(I) Complex for Selective Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction to CO. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 4603–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ngo KT; McKinnon M; Mahanti B; Narayanan R; Grills DC; Ertem MZ; Rochford J Turning on the Protonation-First Pathway for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Manganese Bipyridyl Tricarbonyl Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2604–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Smieja JM; Sampson MD; Grice KA; Benson EE; Froehlich JD; Kubiak CP Manganese as a Substitute for Rhenium in CO2 Reduction Catalysts: The Importance of Acids. Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 2484–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sampson MD; Kubiak CP Manganese Electrocatalysts with Bulky Bipyridine Ligands: Utilizing Lewis Acids To Promote Carbon Dioxide Reduction at Low Overpotentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 1386–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sung S; Li X; Wolf LM; Meeder JR; Bhuvanesh NS; Grice KA; Panetier JA; Nippe M Synergistic Effects of Imidazolium-Functionalization on fac-Mn(CO)3 Bipyridine Catalyst Platforms for Electrocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 6569–6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Agarwal J; Stanton Iii CJ; Shaw TW; Vandezande JE; Majetich GF; Bocarsly AB; Schaefer Iii HF Exploring the effect of axial ligand substitution (X = Br, NCS, CN) on the photodecomposition and electrochemical activity of [MnX(N–C)(CO)3] complexes. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2122–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Matson BD; McLoughlin EA; Armstrong KC; Waymouth RM; Sarangi R Effect of Redox Active Ligands on the Electrochemical Properties of Manganese Tricarbonyl Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 7453–7465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Grills DC; Farrington JA; Layne BH; Lymar SV; Mello BA; Preses JM; Wishart JF Mechanism of the Formation of a Mn-Based CO2 Reduction Catalyst Revealed by Pulse Radiolysis with Time-Resolved Infrared Detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 5563–5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bhattacharya M; Sebghati S; Vercella YM; Saouma CT Electrochemical Reduction of Carbamates and Carbamic Acids: Implications for Combined Carbon Capture and Electrochemical CO2 Recycling. J. Electrochem. Soc 2020, 167, No 086507. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Coetzee JF; Padmanabhan GR Properties of Bases in Acetonitrile as Solvent. IV. Proton Acceptor Power and Homoconjugation of Mono- and Diamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1965, 87, 5005–5010. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Raamat E; Kaupmees K; Ovsjannikov G; Trummal A; Kütt A ; Saame J; Koppel I; Kaljurand I; Lipping L; Rodima T; Pihl V ; Koppel IA; Leito I Acidities of strong neutral Brønsted acids in different media. J. Phys. Org. Chem 2013, 26, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- (43).The catalytic reduction of CO2 with (mesbpy)Mn(CO)3Br is reported to give CO with weak acids such as MeOH, water, and trifluoroethanol.

- (44).Rakowski Dubois M; Dubois DL Development of Molecular Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction and H2 Production/Oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42, 1974–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhanaidarova A; Jones SC; Despagnet-Ayoub E; Pimentel BR; Kubiak CP Re(tBu-bpy)(CO)3Cl Supported on Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Selectively Reduces CO2 in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 17270–17277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Cheung PL; Machan CW; Malkhasian AYS; Agarwal J; Kubiak CP Photocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to CO and HCO2H Using fac-Mn(CN)(bpy)(CO)3. Inorg. Chem 2016, 55, 3192–3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Takeda H; Koizumi H; Okamoto K; Ishitani O Photocatalytic CO2 reduction using a Mn complex as a catalyst. Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 1491–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Sampson MD; Kubiak CP Electrocatalytic Dihydrogen Production by an Earth-Abundant Manganese Bipyridine Catalyst. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 6674–6676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Loewen ND; Thompson EJ; Kagan M; Banales CL; Myers TW; Fettinger JC; Berben LA A pendant proton shuttle on [Fe4N(CO)12]− alters product selectivity in formate vs. H2 production via the hydride [H–Fe4N(CO)12]−. Chemical Science 2016, 7, 2728–2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Garcia Alonso FJ; Llamazares A; Riera V; Vivanco M; Garcia Granda S; Diaz MR Effect of an nitrogen-nitrogen chelate ligand on the insertion reactions of carbon monoxide into a manganese-alkyl bond. Organometallics 1992, 11, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Léval A; Agapova A; Steinlechner C; Alberico E; Junge H; Beller M Hydrogen production from formic acid catalyzed by a phosphine free manganese complex: investigation and mechanistic insights. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 913–920. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Smieja JM; Benson EE; Kumar B; Grice KA; Seu CS; Miller AJM; Mayer JM; Kubiak CP Kinetic and structural studies, origins of selectivity, and interfacial charge transfer in the artificial photosynthesis of CO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 15646–15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Wiedner ES; Chambers MB; Pitman CL; Bullock RM; Miller AJM; Appel AM. Thermodynamic Hydricity of Transition Metal Hydrides. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8655–8692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Waldie KM; Ostericher AL; Reineke MH; Sasayama AF; Kubiak CP Hydricity of Transition-Metal Hydrides: Thermodynamic Considerations for CO2 Reduction. ACS Catal 2018, 8, 1313–1324. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Ceballos BM; Yang JY Directing the reactivity of metal hydrides for selective CO2 reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 12686–12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Pitman CL; Brereton KR; Miller AJM Aqueous Hydricity of Late Metal Catalysts as a Continuum Tuned by Ligands and the Medium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 2252–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Matsubara Y; Grills DC; Koide Y Thermodynamic Cycles Relevant to Hydrogenation of CO2 to Formic Acid in Water and Acetonitrile. Chem. Lett 2019, 48, 627–629. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.