Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to identify factors predicting laboratory-positive coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in pediatric patients with acute respiratory symptoms.

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort study.

Methods

Data from 1849 individuals were analyzed. COVID-19 was confirmed (reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction) in 15.9% of patients, and factors predicting a positive test result were evaluated through prevalence odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Increasing age, personal history of obesity, and household contact with a case were found to be associated, in the multiple regression model, with increased odds of a positive test result. Young patients residing in areas with higher population sizes, as well as those with severe respiratory symptoms, were less likely to be laboratory confirmed.

Conclusions

Early identification and isolation of children and teenagers with suggestive symptoms of COVID-19 is important to limit viral spread. We identified several factors predicting the laboratory test result. Our findings are relevant from a public health policy perspective, particularly after the restart of in-person academic activities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Child, Adolescent, Real-time polymerase chain reaction, Odds ratio

Highlights

-

•

Children and teenagers play an important role in the spread of viral pathogens, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

-

•

We identified factors associated with the odds of positive coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) test results among children and teenagers with acute respiratory symptoms.

-

•

Early identification and isolation of underaged individuals with COVID-19 may reduce the related disease burden.

-

•

Our findings may be highly relevant after the restart of in-person academic activities all around the globe.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has evolved quickly around the globe, and the related socio-economic burden is high.1 Less than 2% of COVID-19 cases are reported in pediatric patients, and they commonly show milder symptoms and a better prognosis than adults.2

Currently, it is unclear if this low rate among children and teenagers results from a diminished susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection or from a higher prevalence of asymptomatic cases.3 Nevertheless, there is a general consensus regarding the role of young individuals in the spread of viral respiratory pathogens.4 , 5 This highlights the relevance of preventive interventions including early case identification and quarantining and limitating crowded physical activities.6

We aimed to evaluate predictors of laboratory-positive SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and teenagers with symptoms of acute viral respiratory infection.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of a nationwide cohort study. Suspected COVID-19 cases (disease onset: February–August 2020) from any age were enrolled in an ambispective cohort study that served as the source for the study sample. Individuals were followed up until disease classification and clinical outcomes. Participants were identified from the nominal records of the National System of Epidemiological Surveillance of Mexico, which operates as per normative standards.7

Potentially eligible children (aged younger than 12 years) and teenagers (12–15 years old) were those with conclusive results (confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, no/yes) of reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and symptom onset from February to April 2020. Asymptomatic patients (without fever, rhinorrhea, or cough; n = 3) at the collection of clinical specimens and those without complete data of interest were excluded (n = 11). All young individuals fulfilling the eligibility criteria were included in our analysis. Enrolled subjects sought for medical attention at any of more than 1400 healthcare settings (all three levels of care) belonging to the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS, the Spanish acronym) located all across the country.

Data collection

Clinical and epidemiological data of interest were obtained from the audited surveillance system and included sociodemographic characteristics (gender, address), date of symptom onset, self-reported household contact with a COVID-19 suspected case (within 14 days, no/yes), personal history of chronic illnesses (no/yes; obesity, asthma, pulmonary obstructive disease, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, immunosuppression, or human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection), disease severity (severe illness defined as dyspnea requiring hospital admission, no/yes), and history of non-communicable diseases. Immunosuppression referred to any identified cause (e.g., malnutrition) of the related deficiency except for that previously cited (personal history of diabetes mellitus, HIV, chronic kidney disease, or asthma). The medical files from the patients are the primary data source of the surveillance system.

The National Urban System database of Mexico,8 which includes data from 401 cities, was used to classify the place of residence of the enrolled subjects as rural or urban.

Laboratory methods

Clinical specimens (nasopharyngeal or deep nasal swabs) were used, and nucleic acids were extracted from 200 μL of the sample using the MagNa Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit automated system (catalog: 03038505001; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), as previously described in the study by Fernandes-Matano et al.9 SARS-CoV-2 detection was performed by using the primers and probes proposed by Corman et al10 using the SuperScript III Platinum One-step qRT-PCR System (catalog: 12574035; Invitrogen Carlsbad, California, USA) in the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, EUA).11

The analytical procedure was performed in the network of laboratories for epidemiological surveillance of the IMSS.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were computed. Prevalence odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate factors predicting a positive qRT-PCR result. Bivariate unconditional logistic regression models were used, and a multiple model was fitted.

Ethical considerations

The written informed consent was provided by any parent or legal guardian from the enrolled pediatric patients. This study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee (601) of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (approval R-2020-601-015; April 30, 2020).

Results

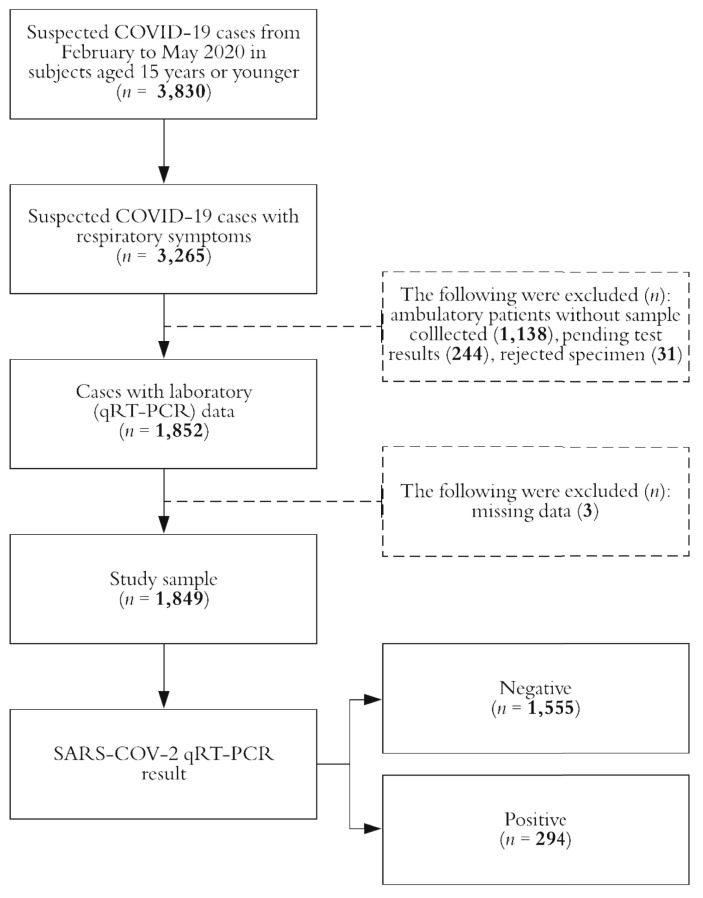

Data from 1849 individuals were analyzed, and COVID-19 was confirmed in 15.9% (n = 294) of them. The study profile is shown in Fig. 1 . Most of participants were males (53.3%) and were aged younger than 3 years (43.6%) at time of acute symptom onset (Table 1 ). Forty-two percent of the analyzed children and teenagers were ambulatory cases, and severe illness was documented in nearly 38% of the subjects.

Fig. 1.

Study profile, Mexico 2020. COVID-19; coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; qRT-PCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample, Mexico 2020.

| Characteristic | Overall |

SARS-CoV-2 test result |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative |

Positive |

|||

| n = 1, 849 | n = 1, 555 | n = 294 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Girl | 863 (46.7) | 728 (46.8) | 135 (45.9) | 0.777 |

| Boy | 986 (53.3) | 827 (53.2) | 159 (54.1) | |

| Age (years)a | 5.3 ± 5.2 | 5.1 ± 5.0 | 6.5 ± 5.7 | <0.001 |

| Age-group (years) | ||||

| <3 | 806 (43.6) | 701 (45.1) | 105 (35.7) | <0.01 |

| 3–5 | 291 (15.7) | 248 (16.0) | 43 (14.6) | |

| 6–12 | 479 (25.9) | 404 (26.0) | 75 (25.5) | |

| 13–15 | 273 (14.8) | 202 (12.9) | 71 (14.2) | |

| Population by place of residence (×1000) | ||||

| <15 | 735 (39.8) | 594 (38.2) | 141 (48.0) | <0.001 |

| 15–49.9 | 296 (16.0) | 274 (17.6) | 22 (7.5) | |

| 50–99.9 | 94 (5.1) | 87 (5.6) | 7 (2.4) | |

| ≥100 | 724 (39.1) | 600 (38.6) | 124 (42.2) | |

| Flu vaccinatedb | ||||

| No | 1552 (83.9) | 1305 (83.9) | 247 (84.0) | 0.969 |

| Yes | 297 (16.1) | 250 (16.1) | 47 (16.0) | |

| Household contact with a casec | ||||

| No | 1542 (83.4) | 1335 (85.9) | 207 (70.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 307 (16.6) | 220 (14.1) | 87 (29.6) | |

| Sudden symptom onset | ||||

| No | 1211 (65.5) | 998 (64.2) | 213 (72.5) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 638 (34.5) | 557 (35.8) | 81 (27.5) | |

| Disease severityd | ||||

| Mild to moderate | 1148 (62.1) | 932 (59.9) | 216 (73.5) | <0.01 |

| Severe | 701 (37.9) | 623 (40.1) | 78 (26.5) | |

| Personal history of | ||||

| Chronic illness (any, yes) | 315 (17.0) | 264 (17.0) | 51 (17.4) | 0.877 |

| Obesity (yes) | 57 (3.1) | 40 (2.6) | 17 (5.8) | 0.003 |

| Asthma (yes) | 104 (5.6) | 93 (6.0) | 11 (3.7) | 0.126 |

| COPD (yes) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0.538 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes) | 13 (0.7) | 10 (0.6) | 3 (1.0) | 0.478 |

| CKD (yes) | 27 (1.5) | 21 (1.4) | 6 (2.0) | 0.366 |

| Immunosuppression (yes)e | 159 (8.6) | 132 (8.5) | 27 (9.2) | 0.697 |

| HIV (yes) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.451 |

SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; COPD; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

The absolute and relative (%) frequencies are presented, except if other is specified; P-value from chi-squared or t-tests as corresponding.

The arithmetic mean ± standard deviation is presented.

During the flu season 2019––20.

Self-reported; within 14 days before the symptoms onset.

Severe illness was defined by dyspnea requiring hospital admission.

Immunosuppression was referred to any identified cause of the related deficiency except for the personal history of diabetes mellitus, HIV, CKD, or asthma.

When compared with participants who tested negative (Table 1), patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 were older (6.5 ± 5.7 vs. 5.3 ± 5.2 years old, P < 0.001), were more likely to reside in localities with a population size lower than 15,000 inhabitants (48.0% vs. 38.2%, P < 0.001), and showed a higher obesity prevalence (5.8% vs. 2.6%, P = 0.003). Discarded cases of COVID-19 were also more likely to require hospital entry (59.7% vs. 48.3%, P < 0.001).

Confirmed cases also showed a higher prevalence of self-reported household contact with a case (29.6% vs. 14.1%, P < 0.002) within 14 days before acute illness. Sudden disease onset (P = 0.006) and milder symptoms (P < 0.001) were more frequent among discarded SARS-CoV-2 cases (Table 2 ). No gender-related differences were observed.

Table 2.

Predictors of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result, Mexico 2020.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI), p |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| Gender (Ref: girl) | ||||||

| Boy | 1.04 | (0.81–1.33) | 0.777 | 1.08 | (0.83–1.40 | 0.560 |

| Age-group (Ref: <3 years) | ||||||

| 3–5 | 1.16 | (0.79–1.70) | 0.458 | 1.04 | (0.70–1.55) | 0.841 |

| 6–12 | 1.24 | (0.90–1.71) | 0.184 | 1.10 | (0.78–1.53) | 0.592 |

| 13–15 | 2.35 | (1.68–3.30) | <0.001 | 2.08 | (1.46–2.96) | <0.001 |

| Population by place of residence (× 1000; Ref: <15) | ||||||

| 15–49.9 | 0.34 | (0.21–0.54) | <0.001 | 0.34 | (0.21–0.55) | <0.001 |

| 50–99.9 | 0.34 | (0.15–0.75) | 0.007 | 0.34 | (0.15–0.76) | 0.008 |

| 100 | 0.87 | (0.67–1.14) | 0.309 | 0.82 | (0.62–1.08) | 0.154 |

| Household contact with a case (Ref: no) | ||||||

| Yes | 2.55 | (1.91–3.40) | <0.001 | 2.27 | (1.68–3.08) | <0.001 |

| Sudden symptom onset (Ref: no) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.68 | (0.52–0.90) | 0.006 | 0.80 | (0.60–1.06) | 0.122 |

| Disease severity (Ref: mild to moderate) | ||||||

| Severe | 0.54 | (0.41–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.69 | (0.51–0.92) | 0.012 |

| Obesity (Ref: no) | ||||||

| Yes | 2.33 | (1.30–4.16) | 0.004 | 2.05 | (1.11–3.79) | 0.022 |

| Asthma (Ref: no) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.61 | (0.32–1.16) | 0.130 | 0.55 | (0.29–1.06) | 0.075 |

| Immunosuppression (Ref: no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.09 | (0.71–1.68) | 0.697 | 1.22 | (0.79–1.91) | 0.387 |

SARS-CoV-2; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; Ref, reference; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate OR and 95% CI. The listed variables were used to obtain the adjusted estimates. Severe illness was defined by dyspnea requiring hospital admission. Immunosuppression was referred to any identified cause of the related deficiency except for the personal history of diabetes mellitus, human virus immunodeficiency infection, chronic kidney disease, or asthma.

In the multiple regression model (Table 2), a 2-fold increase in the odds of testing positive for COVID-19 was observed among older (13–15 years old) participants (reference: < 3 years old; OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.46–2.96), among those with obesity (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.11–3.79), and among children and adolescents with self-reported household contact with a case (OR = 2.27, 95% CI = 1.68–3.08). When compared with localities with low population sizes (lower than 15,000 inhabitants), individuals residing in more crowded locations were less likely to obtain a positive result. Non-severe respiratory symptoms also reduced the odds of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in infants and teenagers.

Discussion

Our study characterized factors associated with the odds of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric patients with acute upper or lower respiratory symptoms of infection. The presented results may be useful to identify children and teenagers at increased risk of COVID-19 in whom timely quarantining may reduce viral spread, particularly after the restart of in-person education activities.

Given that the COVID-19 pandemic has been distinguished by a low incidence among children, the strengths of this study include a large number of infants and teenagers enrolled and their national representativeness because the participants were obtained from a nationwide prospective cohort. The use of qRT-PCR, the gold standard of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, for clinical specimens from all analyzed subjects is another strength of this study.

As observed in older subjects, we documented an association between increasing age and the odds of a positive test result (ORper year = 1.06; 95% CI = 1.03–1.08). In the age-stratified analysis, this association seemed to be determined by teenagers because (when compared with infants younger than 3 years) a 2-fold increase in the odds of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was documented among them (OR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.36–3.05). Differences in the severity of COVID-19 symptoms among older patients result from angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression, lymphocyte count, and trained immunity might plan an important role in the observed scenario.12 Changes in ACE2 activity during puberty have been documented.13

No gender-related differences in the outcome of interest were observed in the study sample. In male adults, higher disease severity and mortality risk have been documented.14 The protective role of estrogen among postpubertal women seems to be determining the observed scenario.15

After adjustment by age, gender, and other clinical characteristics, participants with obesity were more likely to have a positive qRT-PCR result (OR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.29–4.71). Obesity has been consistently associated with more severe COVID-19 manifestations,16 possibly through inflammatory and metabolic pathways.17 Childhood obesity is also characterized by a low-grade inflammation status,18 which makes it plausible that children infected by SARS-CoV-2 and with high adiposity levels were more likely to develop respiratory symptoms and to be studied as suspected COVID-19 cases. Globally, Mexico has one of the highest prevalence for children who are overweight or obese, and increasing trends have been documented.19 The COVID-19 lockdown may worsen the childhood obesity pandemic.20 However, further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism of obesity-related susceptibility to coronavirus infections.

Nearly 11% of confirmed cases were reported among newborns (mean age = 12.3 ± 8.9 days); however, current data suggest that viral transmission may be secondary to household contact with other cases rather than vertical (intrauterine) or peripartum transmission or through breastfeeding.21 Moreover, in our research, self-reported household contact with a case was associated with the highest increase in the odds of laboratory-positive COVID-19 (OR = 2.27, 95% CI = 1.68–3.08). Even if controversial, the current consensus regarding the average number of new infections caused by each patient (reproduction number [R]) is about 3.22

As per our findings, pediatric patients residing in larger localities were less likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19. The documented association deviates from the World Health Organization COVID-19 preparedness guidance, which states a higher transmission risk in more crowded areas.23 The research group suggests that this may be secondary, at least partially, to socio-economic gaps between rural and urban areas of Mexico24 and to lower physical restrictions during the pandemic in less urbanized areas. If later replicated, further research is needed to identify factors determining these findings.

The inclusion of only patients who sought healthcare attention is a limitation of the study and may be implied, among others, in the high documented frequency of severe illness (26.5% and 40.1% in confirmed and discarded COVID-19 cases, respectively). However, and since no mass SARS-CoV-2 screening has been performed in Mexico,7 we consider that our results are still useful to detect pediatric patients with acute respiratory symptoms who are at increased risk of being positive cases of COVID-19.

Conclusion

Children and teenagers seem to account for a relatively small proportion of COVID-19 cases. However, they may play a role in the spread of respiratory viruses, and their timely identification and isolation may be useful to reduce the related disease burden. We identified factors associated with the odds of laboratory-confirmed disease in a large sample of subjects, and our findings may be useful from a public health perspective, mainly after in-personal scholar activities are reinitialized.

Author statements

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee (601) of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (approval R-2020-601-015; April 30, 2020).

Funding

None to declare.

Competing interests

None to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.10.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kickbusch I., Leung G.M., Bhutta Z.A., Matsoso M.P., Ihekweazu C., Abbasi K. 2020. Covid- 19: how a virus is turning the world upside down. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallapaty S. How do children spread the coronavirus? the science still isn't clear. Nature. 2020;581(7807):127–128. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi Q., Wu Y., Mei S., Ye C., Zou X., Zhang Z. Epidemiology and transmission of covid-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan J.F.-W., Yuan S., Kok K.-H., To K.K.-W., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Z.-M., Fu J.-F., Shu Q., Chen Y.-H., Hua C.-Z., Li F.-B. Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus. World journal of pediatrics. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castagnoli R., Votto M., Licari A., Brambilla I., Bruno R., Perlini S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (sars-cov-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secretar´ıa de Salud del Gobierno de Me´xico Lineamiento estandarizado para la vigilancia epidemiolo'gica y por laboratorio de la enfermedad respiratoria viral. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/552972/Lineamiento_VE_y_Lab_Enf_Viral_20.05.20.pdf URL.

- 8.Secretar´ıa General del Consejo Nacional de Poblacio´n . 2018. Sistema urbano nacional de Me'xico.http://www.conapo.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/Marginacion/Datos_Abiertos/SUN/Base_SUN_2018.csv URL. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes-Matano L., Monroy-Muñoz I., de Leo´n M.B., Leal-Herrera Y., Palomec- Nava I., Ru´ız-Pacheco J. Analysis of influenza data generated by four epidemiological surveillance laboratories in Mexico, 2010–2016. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147 doi: 10.1017/S0950268819000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019- ncov) by real-time rt-pcr. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social Plan de preparacio'n y respuesta institucional ante una epidemia por 2019-nCoV. https://www.uv.mx/personal/aherrera/files/2020/03/COVID-2019nCoV-IMSS.pdf URL.

- 12.Cristiani L., Mancino E., Matera L., Nenna R., Pierangeli A., Scagnolari C., Midulla F. 2020. Will children reveal their secret? the coronavirus dilemma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J., Ji H., Zheng W., Wu X., Zhu J.J., Arnold A.P. Sex differences in renal angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ace2) activity are 17β-oestradiol-dependent and sex chromosome-independent. Biol Sex Differ. 2010;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin J.-M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.-F., Han D.-M. Gender dif- ferences in patients with covid-19: focus on severity and mortality. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Channappanavar R., Fett C., Mack M., Ten Eyck P.P., Meyerholz D.K., Perlman S. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Immunol. 2017;198(10):4046–4053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argenziano M.G., Bruce S.L., Slater C.L., Tiao J.R., Baldwin M.R., Barr R.G. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. Br Med J. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michalakis K., Ilias I. Sars-cov-2 infection and obesity: common inflammatory and metabolic aspects, Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. Clin Res Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magrone T., Jirillo E. Childhood obesity: immune response and nutritional approaches. Front Immunol. 2015;6:76. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herna´ndez-Cordero S., Cuevas-Nasu L., Morales-Rua´n M.d.C., Humara´n I.M.-G., Vila-Arcos M.A., Rivera-Dommarco J. Overweight and obesity in mexican children and adolescents during the last 25 years. Nutr Diabetes. 2017;7(3) doi: 10.1038/nutd.2017.29. e247–e247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pietrobelli A., Pecoraro L., Ferruzzi A., Heo M., Faith M., Zoller T. Effects of covid-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in verona, Italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dashraath P., Jeslyn W.J.L., Karen L.M.X., Min L.L., Sarah L., Biswas A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) pandemic and preg- nancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupferschmidt K. Why do some covid-19 patients infect many others, whereas most don't spread the virus at all. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abc8931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization Strengthening preparedness for COVID-19 in cities and urban settings. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1275991/retrieve URL.

- 24.National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy Rural poverty in Mexico: prevalence and challenges. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2019/03/RURAL-POVERTY-IN-MEXICO-CONEVAL.-Expert-Meeting.-15022019.pdf URL.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.