Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in SARS-CoV-2 patients constitutes a major challenge due to the risk of viral aerosolization and infection. Several maneuvers involve the generation of aerosols, including chest compression and airway interventions, with close and prolonged exposure of healthcare providers. Thus, the method selected to secure the airway should avoid airway leaks. Tracheal intubation provides the most secure and reliable airway.1 If a cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) is used with a High Efficiency Particle Arresting (HEPA) filter, the resulting closed-circuit carries a lower risk of aerosolization than any other method.2 Alternatively, the supraglottic airway devices (SADs) are easy to insert without interrupting chest compressions and constitute effective rescue techniques.3 Second-generation SADs present an improved oropharyngeal seal which enables positive airway pressure ventilation at a higher level.2, 4 However, these devices could not be effective in preventing the generation of aerosols. The aim of this evaluation was to compare the amount of aerosols generated by different second-generation SADs during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a high-fidelity simulation model.

The study was conducted in the Research Unit of the Anesthesiology Department of Bnai Zion Medical Center in Haifa, Israel. The trachea of an Air Man simulator (Laerdal, Norway) was charged with 2 ml of Glo Germ Powder (Glo Germ Northbrook, IL, US), an odorless powder which glows brightly when exposed to ultraviolet light. It has its rationale in the expulsion of powder from the trachea of the simulator if the seal of the SAD is lower than the reached positive pressure during chest compressions. Five cardiac massages at the usual depth and rate (5–6 cm at 2 compressions per second) were applied on the simulator with six different second-generation SADs placed. The expulsion of powder through the mouth of the simulator with each SAD was objectified by ultraviolet light and recorded with pictures taken with a Canon EOS Rebel T7 camera (Canon, USA). The tested devices were the LMA Supreme and LMA Proseal (Teleflex Medical, Illinois, USA), Ambu AuraGain (Ambu Medical, Denmark), i-gel (Intersurgical, UK), Laryngeal Tube Suction Disposable (VBM Sulz, Germany), and Combitube (Tyco-Healthcare-Kendall-Sheridan, Mansfield, MA, USA). The cuff of all them was inflated with 80 cm H2O, additional 20 cm H2O at the recommended pressure by the manufacturers in order to improve the seal as an intent to enhance the barrier to the aerosol leak during the cardiac compression. A HEPA filter was attached in the 15 mm connector of each device. After each trial, the tracheal simulator was cleaned and recharged again with the same amount of Glo Germ Powder.

A cuffed ETT with a HEPA filter is an effective barrier (Fig. 1 ). However, all tested second-generation SADs showed a considerable aerosol leakage through the mouth and nose of the simulator (Fig. 2 ). The findings are similar to those of Ott et al.5 These findings emphasize the relevance of using physical barriers around the airway and adequate personal protective equipment to ensure the safety of health care providers in situations in which the use of these devices is unavoidable.

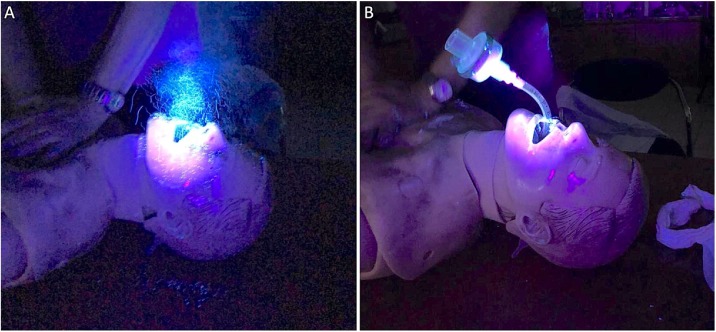

Fig. 1.

Image obtained during the application of five cardiac massages on the simulator without any airway device (Panel A) and with a cuffed 8.0-mm inside diameter Endotracheal Tube (ETT Portex, Smiths Medical, Kent, UK) inflated with 20cc of air (Panel B). Panel A shows generation of aerosol dispersion of the power, while panel B shows the effectiveness of sealing of the endotracheal tube by objectifying no leak.

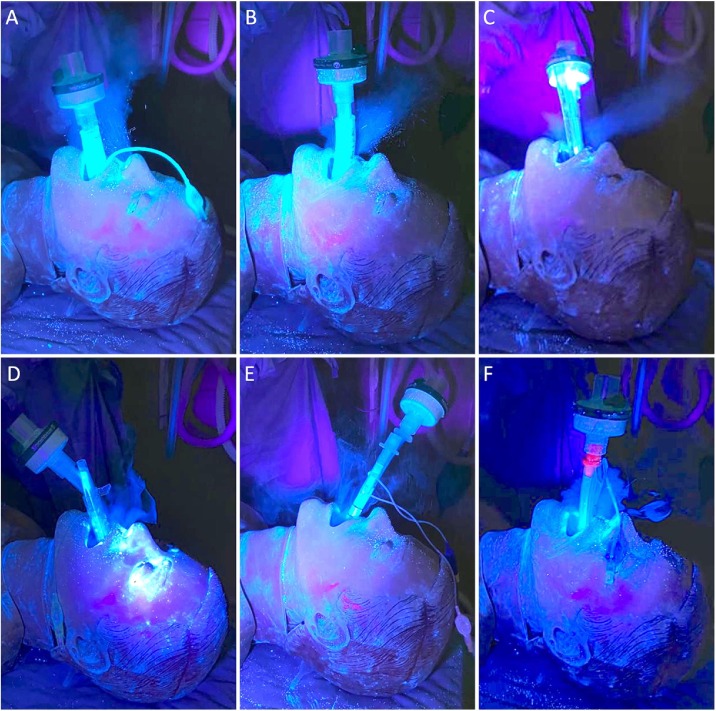

Fig. 2.

SGAs with aerosol leaks during cardiac massage. AuraGain (A), I-gel (B), LMA ProSeal (C), LMA Supreme (D), Combitube (E), LTS-D (F). All the evaluated SGAs showed similar aerosol-generating processes.

Funding

Support was provided solely from institutional and/or departmental sources.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Benoit J.L., Gerecht R.B., Steuerwald M.T., McMullan J.T. Endotracheal intubation versus supraglottic airway placement in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2015;93:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelson D.P., Sasson C., Chan P.S., et al. Interim guidance for basic and advanced life support in adults, children, and neonates with suspected or confirmed COVID-19: from the emergency cardiovascular care committee and get with the guidelines-resuscitation adult and pediatric task forces of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e933–e943. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frerk C., Mitchell V.S., McNarry A.F., et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:827–848. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook T.M., El-Boghdadly K., McGuire B., McNarry A.F., Patel A., Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: guidelines from the difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:785–799. doi: 10.1111/anae.15054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ott M., Milazzo A., Liebau S., et al. Exploration of strategies to reduce aerosol-spread during chest compressions: a simulation and cadaver model. Resuscitation. 2020;152:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]