Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the medical and social vulnerability of an unprecedented number of people. Consequently, there has never been a more important time for clinicians to engage patients in advance care planning (ACP) discussions about their goals, values, and preferences in the event of critical illness. An evidence-based communication tool—the Serious Illness Conversation Guide—was adapted to address COVID-related ACP challenges using a user-centered design process: convening relevant experts to propose initial guide adaptations; soliciting feedback from key clinical stakeholders from multiple disciplines and geographic regions; and iteratively testing language with patient actors. With feedback focused on sharing risk about COVID-19–related critical illness, recommendations for treatment decisions, and use of person-centered language, the team also developed conversation guides for inpatient and outpatient use. These tools consist of open-ended questions to elicit perception of risk, goals, and care preferences in the event of critical illness, and language to convey prognostic uncertainty. To support use of these tools, publicly available implementation materials were also developed for clinicians to effectively engage high-risk patients and overcome challenges related to the changed communication context, including video demonstrations, telehealth communication tips, and step-by-step approaches to identifying high-risk patients and documenting conversation findings in the electronic health record. Well-designed communication tools and implementation strategies can equip clinicians to foster connection with patients and promote shared decision making. Although not an antidote to this crisis, such high-quality ACP may be one of the most powerful tools we have to prevent or ameliorate suffering due to COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the medical and social vulnerability of an unprecedented number of people in the United States and globally. Rapidly evolving epidemiologic and prognostic information about the coronavirus has heightened uncertainty about its potential effect on individuals, creating a need for high-quality communication between clinicians, patients, and families. A sense of urgency has emerged for clinical communication about risk or prognosis related to COVID-19 and elicitation of patients’ personal values and priorities to guide current or future medical decisions (advance care planning [ACP]).1., 2., 3., 4.

Although patients and clinicians are having ACP conversations on an unprecedented scale, doing so involves negotiating an evolving and complex care environment: patients alone in rooms without family or visitors, conversations occurring via phone or digital technologies, clinicians working tirelessly to care for patients while also fearing for their own safety, and amplification of preexisting systemic inequities and disparities. These realities lead to moral injury, collective trauma, and distress for patients, families, and clinicians.

ACP can improve patient well-being, experience, and quality of care by aligning care with what matters most to patients and avoiding burdensome and unwanted treatments at the end of life.5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11. Given the speed with which the virus is spreading, uncertainty about its short- and long-term consequences, and the disproportionate negative impact on specific populations (for example, older adults, patients with underlying medical conditions, and persons of color),12 we face an enormous volume of patients who would benefit from empathic ACP conversations with their clinical teams.

Unfortunately, health systems often struggle to reliably deliver such communication to patients who would benefit. On average, fewer than one third of patients with serious illness have these conversations or do so too late in the course of illness (for example, the last weeks of life) to make a difference.13., 14., 15., 16., 17. In addition, when discussions do occur, inconsistent and inaccessible documentation of patients’ preferences may result in medical errors characterized by patients receiving treatments that poorly reflect their known goals and wishes.18 , 19 This urgent need for high-quality, well-documented ACP conversations during the COVID-19 pandemic calls for rapid mobilization of innovative and flexible approaches to ensure that patients and families receive care aligned with their values and preferences.

Numerous interventions exist to close the quality gap, including clinician training programs and communication tools.7 , 8 , 20., 21., 22., 23. Our team has spent the last nine years designing, testing, and scaling one evidence-based program, which is centered on our Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG, or guide).1 , 24 This guide was developed with iterative input from interdisciplinary clinicians from a variety of specialties, as well as patients. Studies of program implementation demonstrate more, earlier, and better conversations; positive patient and clinician experiences; improvements in patient anxiety and depression; and lower health care expenses at the end of life.7 , 8 , 25., 26., 27., 28. We adapted the SICG to meet the unique communication needs of patients, families, and clinicians during the time of COVID-19. We employed a user-centered design approach to tool development. The process addressed the whole user experience, driven and refined by user-centered evaluation and grounded in an explicit understanding of users, tasks, and environments. This article describes the tool development strategy, the themes that emerged from stakeholder engagement, and the two communication guides that resulted from this process, which clinicians have put to immediate use in the inpatient and outpatient clinical settings.

Tool Development

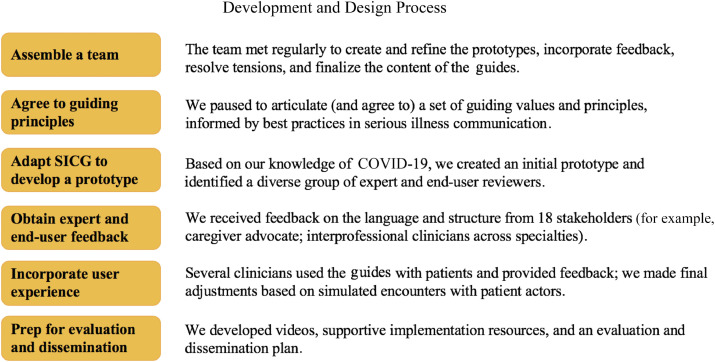

We sought to identify the unique challenges of communication for patients, families, and clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic and how they might be addressed using adaptations of existing tools. For that reason, we engaged in a user-centered design approach that balanced the need for rigor and structure with expediency. Over a three-week period in March and April 2020, we employed the following steps (Figure 1 ):

-

1.

We assembled a team of eight individuals composed of the chief medical officer of Ariadne Labs and the former vice president for Population Health and Quality for Baystate Health [E.B.]; physicians with expertise in palliative care and significant experience creating evidence-based ACP tools and clinician training programs [J.P., E.K.F., J.J.S.]; the director of Implementation of Ariadne Labs and a nurse leader and quality improvement expert [S.G.]; a health care delivery expert and hospitalist physician [N.M.]; a physician in family medicine and health care disparities expert [S.M.]; and a project manager [N.D.]. Team members are based in Boston, a COVID-19 “hotspot” during the period of tool development.

-

2.

We identified guiding principles for the development of the adapted communication tools based on best practices in ACP conversations and person-centered communication techniques.1 , 20 , 29., 30., 31.

-

3.

We elicited feedback from an external review panel (N = 18) that consisted of experts in ACP and end users of the communication tools, including caregiver and disabilities advocate and interprofessional clinicians (physicians, nurses, social workers) in primary care, family medicine, palliative care, nephrology, ethics, hospitalist medicine, emergency medicine, and psychiatry. Several of these reviewers based their feedback on use of the tool with actual patients in their clinical practices. These individuals came from health care organizations in different geographic locations, including Philadelphia; Palo Alto, California; Atlanta; and Boston.

-

4.

We incorporated input from end-user experience in which clinicians used the communication tools with patients or families. We also tested and refined the tools in simulated encounters with patient actors.

Figure 1.

Shown here is the development and design process to create the COVID-19 Conversation Guides for Outpatient and Inpatient Care.

Throughout this process, the design team held regular meetings to create and iterate the prototypes, incorporate feedback, resolve tensions, and finalize design changes.

Tool Description

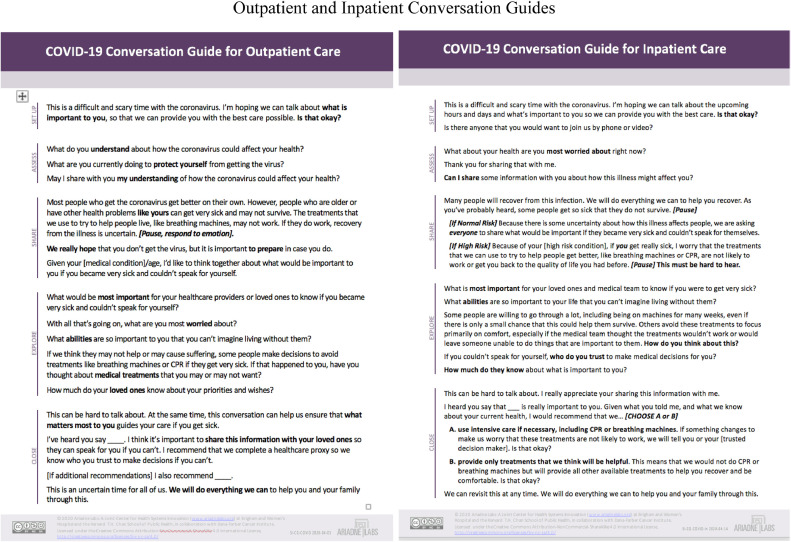

This process resulted in two conversation guides and supportive materials, accessible through the Ariadne Labs Serious Illness Care Program COVID-19 Response website (Figure 2 ). The COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Outpatient Care equips clinicians to proactively reach out to patients in the community with underlying health conditions who are at higher risk of serious complications should they contract COVID-19.32 The tool supports clinicians to ask patients about protective measures, share risk related to COVID-19, elicit what would be important to patients should they become critically ill, invite patients to identify a trusted decision maker, and create a care plan based on patient priorities and preferences. The COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Inpatient Care equips clinicians to have ACP conversations with patients admitted to the hospital with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 (or their families). The tool invites patients to identify a trusted decision maker; emphasizes patients’ values, priorities, and preferences so clinicians can honor them; and informs decision making about life-sustaining treatments.

Figure 2.

Shown here are the COVID-19 outpatient and inpatient conversation guides.

The design team agreed to adhere to guiding principles to develop the tools, including (1) conversations retain the purpose of ensuring that care plans and treatment decisions align with what matters most to patients; (2) the language and content include high-quality communication techniques and hew closely to the evidence-based structure and flow of the SICG, which is psychologically informed to create safety and build trust; and (3) the tool is concise (one page), is adaptable, and uses simple and relatable language. Based on these guiding principles, the team created prototypes of the outpatient and inpatient guides that retained the structure of the original SICG, including setting up the conversation; assessing patients’ worries and current understanding of their illness; sharing information about what may be ahead; exploring values, priorities, and preferences; and closing the conversation by making a recommendation and reaffirming commitment to care.24 , 33

Results and Lessons

We received feedback from expert reviewers on the initial protypes in response to structured questions that assessed the language of the guides for clarity and simplicity and the utility and clinical relevance of its elements, based in some cases on their use of the guides with patients. We analyzed this feedback to identify key themes.

Theme 1: Communicating Uncertainty Around COVID-19–Related Risk and Prognosis

Reviewers emphasized the importance of acknowledging uncertainty when sharing information about risks related to COVID-19 infection. Patients with underlying conditions are at higher risk of poor outcomes, but many patients recover from the infection. Yet even young and healthy people are known to get very sick quickly and die from the virus. This reality creates the need to normalize ACP conversations such that they reach a broader population of patients.

Questions also arose about how comprehensive to be with regard to sharing information. For example, several reviewers felt that high-risk patients, even those who do not have the infection, need to know that they have a higher risk of developing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) should they become critically ill from COVID-19, which carries a poor prognosis.32 , 34 , 35 For hospitalized patients with underlying conditions, several reviewers felt that specific information about the experience of being on a ventilator for COVID-ARDS should be shared, such as a potentially long ventilator and ICU course and a potentially high likelihood of dying and/or experiencing post-acute disability.

Given the themes raised, we based our adaptations on the following principles and evidence (Sidebar 1 ): (1) patients and families often want information about the future of their health, even if it is uncertain 36., 37., 38.; (2) sharing too much information (including too many medical details), too little information, or vague information may increase patient anxiety and may not be helpful in making decisions 39 , 40; and (3) sharing information with compassionate language builds trust and helps manage anxiety when receiving difficult news.41., 42., 43., 44.

Sidebar 1.

|

Sharing information about risk from COVID-19 in the outpatient setting: Most people who get the coronavirus get better on their own. However, people who are older or have other health problems like yours can get very sick and may not survive. The treatments that we use to try to help people live, like breathing machines, may not work. If they do work, recovery from the illness is uncertain. [Pause, respond to emotion]. We really hope that you don't get the virus, but it is important to prepare in case you do. Given your [medical condition]/age, I'd like to think together about what would be important to you if you became very sick and couldn't speak for yourself. Sharing information about risk from COVID-19 in the inpatient setting: Many people will recover from this infection. We will do everything we can to help you recover. As you've probably heard, some people get so sick that they do not survive. [Pause] [If NormalRisk] Because there is some uncertainty about how this illness affects people, we are asking everyone to share what would be important if they became very sick and couldn't speak for themselves. [If High Risk] Because of your [high risk condition], if you get really sick, I worry that the treatments that we can use to try to help people get better, like breathing machines or CPR, are not likely to work or get you back to the quality of life you had before. [Pause] This must be hard to hear. |

Theme 2: Recommendations About Care Planning and Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions

First, the speed with which some patients get critically ill created a sense of urgency around making decisions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or ventilation. For the outpatient guide, for example, several reviewers recommended including a prompt to complete a form with the patient (for example, Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment 45) or to document a code status. Others felt inclusion of these elements on the outpatient tool reflected a rush to life-or-death decisions for patients in the community who do not currently have the virus and may not be ready to make such decisions. Several reviewers also expressed worries that the looming threat of crisis standards of care (for example, ventilator shortages and the need for resource allocation) 46., 47., 48. would steer these conversations to overemphasize life-sustaining treatment preferences as the main focus of the discussion.

Second, important considerations arose about systemic inequities and cultural diversity as related to decision making, including disparities in end-of-life care for persons of color.49., 50., 51., 52., 53. Given understandable mistrust in the health care system experienced by marginalized communities, which affects experiences with ACP,54 language or intention that could reflect a bias toward denying life-sustaining treatments can violate trust. This is particularly important right now, given that racial and ethnic minorities are already disproportionately hospitalized and dying from the infection.12 , 55

Third, ensuring that patients were asked about involvement of their loved ones in these conversations and decisions emerged as a priority in both inpatient and outpatient conversations. Conversations that are not communicated with friends and family can trigger conflict and add additional burdens if they are caught off guard by unexpected treatment decisions.56 , 57

Given the issues raised, we based our adaptations on the following principles and best practices (Sidebar 2 ): (1) the content of the recommendation should provide opportunities for customization and should be neutral so as not to reflect bias; (2) for decision making in the context of life-sustaining treatments in the inpatient setting, clinicians should make a recommendation for or against the use of CPR or ventilation that incorporates patients’ priorities as well as the medical situation and then check in with the patient about that recommendation 58 , 59; and (3) we explicitly included language within the structure of both guides to ask patients to identify a trusted decision maker and explore how much that individual knows about their wishes.

Sidebar 2.

|

Making a recommendation in the outpatient setting: This can be hard to talk about. At the same time, this conversation can help us ensure that what matters most to you guides your care if you get sick. I've heard you say ____. I think it's important to share this information with your loved ones so they can speak for you if you can't. I recommend that we complete a healthcare proxy so we know who you trust to make decisions if you can't. [If additional recommendations] I also recommend ____. This is an uncertain time for all of us. We will do everything we can to help you and your family through this. Making a recommendation in the inpatient setting: This can be hard to talk about. I really appreciate your sharing this information with me. I heard you say that ___ is really important to you. Given what you told me, and what we know about your current health, I would recommend that we . . . [CHOOSE A or B] A. use intensive care if necessary, including CPR or breathing machines. If something changes to make us worry that these treatments are not likely to work, we will tell you or your [trusted decision maker]. Is that okay? B. provide only treatments that we think will be helpful. This means that we would not do CPR or breathing machines but will provide all other available treatments to help you recover and be comfortable. Is that okay? We can revisit this at any time. We will do everything we can to help you and your family. |

Theme 3: Using Caring, Person-Centered Language

Although specific concerns and questions arose about sharing information and making decisions, reviewers also drew attention to the importance of ensuring high-quality communication strategies throughout the flow of the discussion. These strategies build connection during difficult conversations, manage anxiety and respond to patients’ emotions, and keep the focus on what matters most to patients.1 , 42 , 58 , 60 , 61 Therefore, we maintained communication techniques from our original SICG and adapted them to fit the needs of COVID-19 (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

COVID-19 Outpatient and Inpatient Conversation Guides Incorporate High-Quality Communication Techniques

| Technique | Examples from the Conversation Guides |

|---|---|

| Asking permission: These uncertain times with coronavirus can create a sense of powerlessness and loss of control. Building rapport early in the conversation by naming this shared experience and asking patients’ permission to proceed before moving forward with the conversation enables patients to maintain control over the discussion. | This is a difficult and scary time with the coronavirus. I'm hoping we can talk about what is important to you, so that we can provide you with the best care possible. Is that okay? |

| Normalizing the conversation: Given the unpredictable nature of COVID-19, normalizing these conversations creates safety for the patient and/or family to think about hard topics. | Because there is some uncertainty about how this illness affects people, we are asking everyone to share what would be important if they became very sick and couldn't speak for themselves. |

| Sharing information with compassionate language and responding to emotion: When sharing difficult news, “hope/prepare” and/or “hope/worry” language aligns with patients and expresses compassion.44 Pausing after sharing difficult information to allow silence and respond to emotions enables patients to process their feelings. Both guides include a statement that invites patients to share their worries, as well as prompts clinicians to pause after sharing information to expect emotion and respond to it.20 | Because of your [high risk condition], if you get really sick, I worry that the treatments that we can use to try to help people get better, like breathing machines or CPR, are not likely to work or get you back to the quality of life you had before. [Pause] This must be hard to hear. |

| Maintaining open-ended questions about what's important to patients: Patients have varying priorities, different things that bring their lives meaning, and diverse views about what might be acceptable or unacceptable in terms of quality of life, all of which influence decisions about care.1,63,70., 71., 72. We maintained open-ended questions to empower patients to share their voice so that priorities remain at the forefront of care plans and decisions. | What is most important for your loved ones and medical team to know if you were to get very sick? With all that's going on, what are you most worried about? What abilities are so important to your life that you can't imagine living without them? |

| Reaffirming commitment to care: It is imperative that clinicians continue to use communication techniques to build trusting relationships with patients and families.31 Expressions that affirm nonabandonment 73 and commitment to doing everything they can to care for the patient are particularly needed during this crisis. | We will do everything we can to help you and your family. |

How to Use the COVID-19 Communication Tools

In both the outpatient and inpatient settings, several reviewers had the opportunity to use the guides with patients, after which clinicians brought up the current context of ACP in the time of COVID-19. Adapted from these clinical encounters, Table 2 provides examples of conversations with patients and families, using COVID-19 communication tools.

Table 2.

Clinical Cases

| COVID-19 Outpatient Conversation Guide |

“Alice”

|

“Derek”

|

| COVID-19 Inpatient Conversation Guide |

“Angela”

|

“Allan”

|

DNR/DNI, do not resuscitate/do not intubate; EHR, electronic health record; RR, respiratory rate; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Hospital safety policies, including the use of personal protective equipment, and social distancing measures (including quarantine), can affect ACP conversations by requiring sensitive conversations to be conducted via telemedicine.62 In-person empathic techniques to build connection and rapport, such as facial expressions or therapeutic touch, are difficult to replicate or replace. Reviewers also raised the challenges of having discussions with families by phone, at times with interpreters, particularly without an opportunity to meet the family members face-to-face beforehand.

These realities require clinicians to be both empathic and efficient in ACP communication while being even more mindful of their language. To respond to these observations, we tested the conversation tools in simulated encounters using video encounters with two patient actors. These formed the basis of the publicly available video demonstrations of both the outpatient and inpatient guides. The Web-based encounters helped to demonstrate that high-quality, compassionate communication can occur during difficult circumstances and informed changes to the guides that enhanced the empathic approaches.

Given this context, engaging a patient or family in a successful conversation about values, goals, and preferences during the time of COVID-19 requires implementation guidance and a series of workflow processes before, during, and after the discussion. Table 3 describes examples of these steps and tips for frontline clinicians to use the guides as part of a clinical workflow.

Table 3.

Implementation Guidance for Outpatient and Inpatient Conversations

| Outpatient | Inpatient |

|---|---|

|

|

Next Steps

Given the speed with which coronavirus spreads, strategies are needed to ensure access to high-quality communication about patients’ values and preferences at all clinical touchpoints. One such strategy involves proactive ACP with community-dwelling and hospitalized people at high risk of COVID-19 complications. Such communication can enhance connection and relationships with isolated patients, identify potential and addressable threats to their health and well-being, and prepare people for difficult decisions by eliciting and documenting information about what matters most in a crisis.26 , 50 , 59 , 63 , 64

Whether it occurs in the community setting or in the hospital, effective communication before an acute crisis is a way to ensure that patients receive treatments that align with their preferences. This may reduce suffering and improve experience for patients and families, reduce moral distress for clinicians (which has been linked to burnout), and guide appropriate use of health care resources.6 , 10 , 13 , 59 , 65., 66., 67., 68. The COVID-19 pandemic creates an opportunity to shift the standard of care from reactive to proactive ACP communication. In this case, the absence of conversations with patients about values and preferences over the illness trajectory is considered a medical error, with attendant negative consequences for patients, families, and clinicians.

The tools described herein can be easily disseminated and paired with virtual training options, accessible electronic health record templates,3 , 7 and technical support by experts (such as palliative care specialists) to improve implementation.48 However, use of structured communication guides is not without risk, including misinterpretation about conversation intent, such as conserving health care resources. That said, a guide may be the best way to ensure that conversations like these focus on more than just life-sustaining treatments, as is typical.

To date, we have disseminated the COVID-19 conversation guides via webinars, virtual workshops, and online educational sessions to health systems that are implementing the Serious Illness Care Program in partnership with Ariadne Labs as part of an implementation collaborative or online community of practice.69 Using surveys and key informant interviews, we plan to evaluate the COVID-19 communication tools by assessing usability, acceptability, and experience from the perspective of patients, families, and clinicians; tracking the strategies that leaders and quality improvement specialists are using to implement the tools in their settings; and identifying key drivers and facilitators of ACP communication during COVID-19 across diverse health systems. Results from this evaluation will allow us to aid health systems and clinicians in implementing high-quality communication during (and beyond) the COVID-19 pandemic by improving the tools and enhancing the development of virtual educational sessions and implementation case studies.

Limitations

A rapid design process during a crisis meant that we were unable to include as robust an array of interprofessional and patient feedback as we would have liked. Although we were able to include input from Black physicians—and although the original SICG has undergone formal testing with Black patients50—we lacked structured input from patients whose communities are most deeply affected by the pandemic. These include ethnic groups for whom the language we adapted, or the English language in which it was written, may not most sensitively account for their needs. Addressing this in part, that these tools have been translated by native speakers into at least six languages: Spanish, French, Portuguese, Haitian Creole, Cape Verdean Creole, and Vietnamese.

Conclusion

Employing a user-centered design process, with feedback from key stakeholders, we adapted an evidence-based structured communication tool, the SICG, to address COVID-related ACP challenges in ambulatory and acute care settings. We plan to follow this effort with attempts to elicit formal feedback from a more diverse set of stakeholders, including Black, Indigenous, and people of color, whose communities have been most deeply affected by the pandemic and whose communication needs and concerns may differ from those who have not been underserved and marginalized by health care systems and clinicians. Access to well-designed communication tools and supportive implementation strategies during times of high stress can better equip clinicians to innovate, adapt, and improvise in ways that foster connection with patients under difficult circumstances and create space for patients’ voices to be heard. Attentive and meaningful communication is not an antidote to this crisis, but it may be one of the most powerful tools we have to spread care, compassion, and healing during this unprecedented time.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation. The funder did not play a role in the design, execution, or writing of this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Stephen D. Brown, Director of the Institute for Professionalism and Ethical Practice at Boston Children's Hospital, for his contributions to the video simulations. The authors would also like to acknowledge all of the reviewers who contributed their time and expertise to this project.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Mitchell holds equity in See Yourself Health LLC, a digital health platform for diabetes education. She also has delivered workshops on Relationship-Centered Care sponsored by Merck & Co. for which no product promotion is permitted.

References

- 1.Bernacki R.E., Block S.D. American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2015. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life.https://download.nap.edu/cart/download.cgi?record_id=18748 Accessed Nov 3, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders J.J. Quality measurement of serious illness communication: recommendations for health systems based on findings from a symposium of national experts. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:13–21. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudore R.L. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack J.W. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Mar 1;28:1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung J.M. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142:128–133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paladino J. Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: a cluster randomized clinical trial of the Serious Illness Care Program. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jun 1;5:801–809. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernacki R. Effect of the Serious Illness Care Program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 1;179:751–759. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis J.R. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jul 1;178:930–940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detering K.M. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010 Mar 23;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright A.A. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dorn A., Cooney R.E., Sabin M.L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020 Apr 189;395:1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyland D.K. Discussing prognosis with patients and their families near the end of life: impact on satisfaction with end-of-life care. Open Med. 2009 Jun 16;3:e101–e110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack J.W. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Feb 7;156:204–210. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack J.W. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Dec 10;30:4387–4395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abarshi E. Discussing end-of-life issues in the last months of life: a nationwide study among general practitioners. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:323–330. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaudemans J.J., Moll van Charante E.P., Willems D.L. Advance care planning in primary care, only for severely ill patients? A structured review. Fam Pract. 2015;32:16–26. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker E. Advance care planning documentation practices and accessibility in the electronic health record: implications for patient safety. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamas D. Advance care planning documentation in electronic health records: current challenges and recommendations for change. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:522–528. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Childers J.W. REMAP: a framework for goals of care conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e844–e850. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.018796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Back A.L. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 12;167:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin C.A. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1213–1221. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung H.O. Educational interventions to train healthcare professionals in end-of-life communication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Apr 29;16:131. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0653-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernacki R. Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open. 2015 Oct 6;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakin J.R. A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communication in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017 Jul 1;36:1258–1264. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paladino J. Patient and clinician experience of a serious illness conversation guide in oncology: a descriptive analysis. Cancer Med. 2020;9:4550–4560. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakin J.R. A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communication in primary care: effect on expenses at the end of life. Healthc (Amst) 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamas D.J. Conversations about goals and values are feasible and acceptable in long-term acute care hospitals: a pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:710–715. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders J.J., Curtis J.R., Tulsky J.A. Achieving goal-concordant care: a conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S17–S27. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakin J.R. Improving communication about serious illness in primary care: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Sep 1;176:1380–1387. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Street R.L., Jr How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu C. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jul 1;180:934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ariadne Labs. Serious Illness Conversation Guide. 2015. Accessed Nov 3, 2020. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. https://www.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/05/SI-CG-2017-04-21_FINAL.pdf.

- 34.Arentz M. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020 Apr28;323:1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Y. Risk factors associated with disease progression in a cohort of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:428–436. doi: 10.21037/apm.2020.03.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans L.R. Surrogate decision-makers’ perspectives on discussing prognosis in the face of uncertainty. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Jan 1;179:48–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-969OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahalt C. “Knowing is better”: preferences of diverse older adults for discussing prognosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:568–575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1933-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cagle J.G. If you don't know, all of a sudden, they're gone”: caregiver perspectives about prognostic communication for disabled elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1299–1306. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Back A.L., Arnold R.M. Discussing prognosis: “How much do you want to know?” Talking to patients who are prepared for explicit information. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 1;24:4209–4213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Back A.L., Arnold R.M. Discussing prognosis: “How much do you want to know?” Talking to patients who do not want information or who are ambivalent. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 1;24:4214–4217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakin J.R., Jacobsen J. Softening our approach to discussing prognosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 1;179:5–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell T.C. Discussing prognosis: balancing hope and realism. Cancer J. 2010;16:461–466. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f30e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobsen J. When a patient is reluctant to talk about it: a dual framework to focus on living well and tolerate the possibility of dying. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:322–327. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson V.A. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:894–900. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National POLST. POLST and COVID-19. 2020. Accessed Nov 3, 2020. https://polst.org/covid/?pro=1.

- 46.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response, vol. 1: Introduction and CSC Framework.https://download.nap.edu/cart/download.cgi?record_id=13351 Accessed Nov 3, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fausto J. Creating a palliative care inpatient response plan for COVID-19—the UW Medicine experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowman B.A. Crisis symptom management and patient communication protocols are important tools for all clinicians responding to COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e98–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson R.W. Differences in level of care at the end of life according to race. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:335–343. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders J.J. From barriers to assets: rethinking factors impacting advance care planning for African Americans. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17:306–313. doi: 10.1017/S147895151800038X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mack J.W. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Sep 27;170:1533–1540. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foy K.C. DeGraffinreid CR, Paskett ED. Disparities in breast cancer tumor characteristics, treatment, time to treatment, and survival probability among African American and white women. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2018 Mar 20;4:7. doi: 10.1038/s41523-018-0059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith A.K., Earle C.C., McCarthy E.P. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanders J.J., Robinson M.T., Block S.D. Factors impacting advance care planning among African Americans: results of a systematic integrated review. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:202–227. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garg S. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Moral Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 17;69:458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e3.htm?s_cid=mm6915e3_w Accessed Nov 3, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiarchiaro J. Prior advance care planning is associated with less decisional conflict among surrogates for critically ill patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1528–1533. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-253OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sudore R.L., Fried T.R.. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Aug 17;153:256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacobsen J. I'd recommend . . .” How to incorporate your recommendation into shared decision making for patients with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1224–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Curtis J.R., Kross E.K., Stapleton R.D. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020 May 12;323:1771–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gramling R. Feeling heard and understood: a patient-reported quality measure for the inpatient palliative care setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Back A., Tulsky J.A., Arnold R.M. Communication skills in the age of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jun 2;172:759–760. doi: 10.7326/M20-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pattison N.. End-of-life decisions and care in the midst of a global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;58 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steinhauser K.E. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sudore R.L. Engaging diverse English- and Spanish-speaking older adults in advance care planning: the PREPARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Dec 1;178:1616–1625. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dzeng E. Moral distress amongst American physician trainees regarding futile treatments at the end of life: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3505-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel M.I. Effect of a lay health worker intervention on goals-of-care documentation and on health care use, costs, and satisfaction among patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;4:1359–1366. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boissy A. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:755–761. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3597-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fumis R.R.L. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:71. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ariadne Labs Ariadne Partners with Health Systems to Initiate Serious Illness Conversation Programs. Schorow S. 2019 https://www.ariadnelabs.org/resources/articles/news/ariadne-partners-with-health-systems-to-initiate-serious-illness-conversation-programs/ Accessed Nov 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fried T.R. Health outcome prioritization to elicit preferences of older persons with multiple health conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fried T.R. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Nov 14;171:1854–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Steinhauser K.E. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Epner D.E., Ravi V., Baile W.F. “When patients and families feel abandoned. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1713–1717. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]