Significance

Arctic sea ice is an important component of the Earth’s climate system, but prior to its recent reduction, its long-term natural instabilities need to be better documented. In this study, information on past sea-ice conditions across the Arctic Ocean demonstrates that whereas its western and central parts remained occupied by perennial sea ice throughout the present interglacial, its southeastern sector close to the Russian margin experienced, at least, sporadic seasonal sea-ice-free conditions during the warmer part of the present interglacial until ∼4,000 y ago. Sea-ice-free conditions during summer in the southeastern Arctic Ocean seem, therefore, to be a recurrent feature linked to its natural variability during warm episodes of the past.

Keywords: Arctic, sea ice, Holocene, climate, ocean

Abstract

The impact of the ongoing anthropogenic warming on the Arctic Ocean sea ice is ascertained and closely monitored. However, its long-term fate remains an open question as its natural variability on centennial to millennial timescales is not well documented. Here, we use marine sedimentary records to reconstruct Arctic sea-ice fluctuations. Cores collected along the Lomonosov Ridge that extends across the Arctic Ocean from northern Greenland to the Laptev Sea were radiocarbon dated and analyzed for their micropaleontological and palynological contents, both bearing information on the past sea-ice cover. Results demonstrate that multiyear pack ice remained a robust feature of the western and central Lomonosov Ridge and that perennial sea ice remained present throughout the present interglacial, even during the climate optimum of the middle Holocene that globally peaked ∼6,500 y ago. In contradistinction, the southeastern Lomonosov Ridge area experienced seasonally sea-ice-free conditions, at least, sporadically, until about 4,000 y ago. They were marked by relatively high phytoplanktonic productivity and organic carbon fluxes at the seafloor resulting in low biogenic carbonate preservation. These results point to contrasted west–east surface ocean conditions in the Arctic Ocean, not unlike those of the Arctic dipole linked to the recent loss of Arctic sea ice. Hence, our data suggest that seasonally ice-free conditions in the southeastern Arctic Ocean with a dominant Arctic dipolar pattern, may be a recurrent feature under “warm world” climate.

The Arctic Ocean is often considered the last frontier of the Earth, mostly due to its difficult access for observation and monitoring. Fortunately, recent satellite data provide critical information on its high-frequency sensitivity allowing to document its role in the climate system through the so-called “Arctic amplification” (1) and on extreme weather conditions at midlatitudes through teleconnection linkages (2–4). This current knowledge of the Arctic sea-ice dynamics and decline is based on about 40 y of satellite observation, an interval insufficient to document the full range of its natural variability and to fully assess feedbacks on the global ocean, climate, and ecosystems. The documenting of Arctic sea-ice variability, especially with respect to low-frequency secular to millennial scale forcings and feedbacks, is still required to fully assess the effective role of anthropogenic versus natural forcing in its near future fate (5). Here, the examination of long-term paleoclimate archives is essential. The compilation of annually resolved climate data, such as tree-ring and ice core records from the circumArctic led to suggest that the decline in the sea-ice cover over the past decades is unprecedented, at least, for the past 1,400 y (6). Adding the recent observational records, it is tempting to hypothesize an exclusive relationship between the sea-ice decline and the ongoing global warming and to predict a fast and complete disappearance of perennial sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. However, linkages among climate, ocean, and sea ice are too complex for such an extrapolation. Moreover, the past 1,400 y only encompass a small fraction of the climate variations that occurred during the Cenozoic (7, 8), even during the present interglacial, i.e., the Holocene (9), which began ∼11,700 y ago. To assess Arctic sea-ice instabilities further back in time, the analyses of sedimentary archives is required but represents a challenge (10, 11). Suitable sedimentary sequences with a reliable chronology and biogenic content allowing oceanographical reconstructions can be recovered from Arctic Ocean shelves, but they rarely encompass more than the past 10,000 y because they remained emerged and subject to glacial erosion during most of the past ice age. Sedimentary records can be obtained from deeper settings in the central Arctic Ocean, but their chronology is equivocal due to: i) highly variable but overly low accumulation rates, ii) the rarity of biogenic remains that can be dated, ensuing from low primary productivity, and iii) the blurred foraminifera 18O records preventing the setting of an oxygen isotope stratigraphy (12–14). Consequently, most studies of the central Arctic sedimentary records only led to very speculative conclusions.

Data sets from sediment cores documenting the sea-ice cover in the circum-Arctic and spanning, at least, the middle-to-late Holocene, are available for the Beaufort, Chukchi, East Siberian, Laptev, and Kara seas (15–21). They indicate an overall dense sea-ice cover with temporal changes in concentration or seasonal extent. Data from cores collected in the surrounding subarctic seas of the North Atlantic, in particular, the Greenland, Norwegian, and Barents seas, as well as the Baffin Bay also show relatively large amplitude variations in their winter and spring sea-ice cover but mostly illustrate an increasing trend from the thermal optimum of the early–middle Holocene characterized by low sea-ice cover, toward the neoglacial high sea-ice cover of the very late Holocene (16, 22–28). Hence, the information available for the present interglacial relates mostly to the Arctic shelves and subarctic seas. It illustrates changes in the position of the sea-ice edge with asynchronous minima around the Arctic. Close to the Arctic gateways, regional discrepancies with respect to the sea-ice distribution point to an important role of exchanges through the Fram Strait as well as through the Barents Sea and Bering Strait, following their early-to-middle Holocene submergences, respectively. Nonetheless, uncertainties in the reconstruction of the sea-ice cover from proxy data as well as the low spatial coverage of the existing records prevent the setting of a comprehensive picture of Holocene sea-ice cover variability. Moreover, the lack of information from the central Arctic Ocean area where dramatic low sea-ice cover was recorded in 2007, 2012, and 2019 (e.g., refs. 29 and 30), constitutes an important and critical unknown about the long-term low-frequency Arctic pack-ice dynamics.

Results from the Lomonosov Ridge

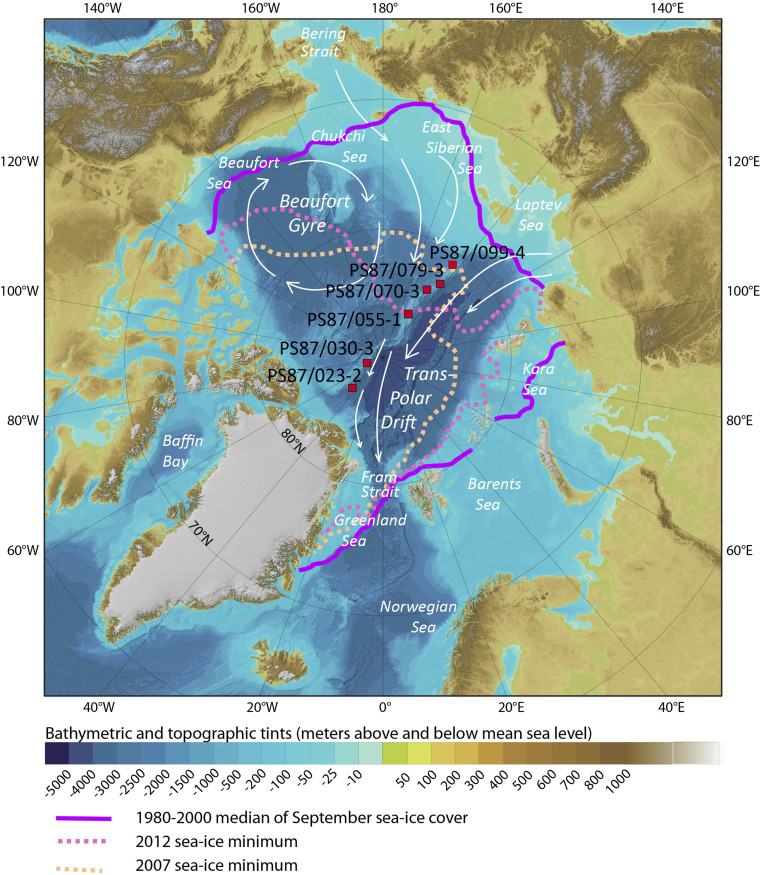

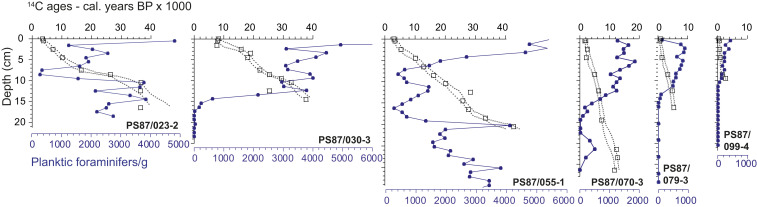

Here, we used sediment cores from the Lomonosov Ridge below the modern Trans-Polar Drift pathway to investigate the sedimentary fluxes in relation with the sea-ice cover of the central Arctic Ocean (Fig. 1). The study cores were collected by means of a giant box corer and a multicorer during the R/V Polarstern Expedition PS87 in 2014 (31). They were sampled at 1-cm intervals for isotopic, sedimentological, geochemical, microfaunal, and palynological analyses. Radiocarbon dating was performed in most samples containing enough calcareous foraminifer shells for measurements by accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS). Results show distinct sedimentary regimes and biogenic contents in the western and central versus southeastern sectors of the ridge (Fig. 2 and Datasets S1–S4). In the western and central sectors (cores PS87/023–2, PS87/030–3, and PS87/055–1) including the North Pole area, which remained under perennial sea-ice cover even during the recent years of extreme sea-ice decline, data show several distinctive features: i) the upper 10 cm of sediments at the sea floor, which consist of a mixture of clay, silt, and sand particles of minerogenic and biogenic origin (31), encompass more than 20,000 y of sedimentation, thus, indicating extremely low sedimentation rates on the order of 5 mm per thousands of years or less; ii) the surface sediment shows a spectacular diversity of calcareous biogenic remains, which include pteropod shells, echinoderm plates, fish otoliths, bivalve shells, ostracods in addition to benthic and planktic foraminifers [see inventories from the expedition report ref. 31]; iii) an excellent preservation of the calcareous microfauna is observed at the surface and below (Dataset S3); iv) the micropaleontological content exclusively relates to heterotrophic production with no remains from phototrophic taxa; v) bioerosional features of rocks and macrofossils including otoliths as well as their iron manganese coating suggest very long exposure time at the water sediment interface (32), compatible with extremely low burial rates. Hence, in the western and central sectors of the Lomonosov Ridge, the data records point to extremely low sedimentary fluxes in an overall “sediment starved” environment, mostly linked to interglacial/interstadial sea-ice rafting deposition or glacial/stadial glacier-ice rafting (14, 33, 34).

Fig. 1.

Map of the Arctic Ocean showing the limits of September sea ice (1980–2001 median, 2007 and 2012; cf. Snow and Ice Data Center https://nsidc.org/data/seaice_index/bist) and location of study sites PS87/023–2 (86°37.86'N and 44°52.45'W, 2439 m), PS87/030–3 (88°39.39'N and 61°25.55'W, 1277 m), PS87/055-1 (85°41.47'N and 148°49.47'E, 731 m). PS87/070-3 (83°48.18'N and 146°7.04'E, 1340 m), PS87/079–3 (83°12.09'N and 141°22.54'E, 1359 m), and PS87/099–4 (81°25.50'N and 142°14.33'E, 741 m). Background map from The International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean (67). White arrows indicate major surface currents and sea-ice rafting routes.

Fig. 2.

Downcore 14C stratigraphies of the study cores (Dataset S1) and planktic foraminifer concentration per gram of sediment (Dataset S3).

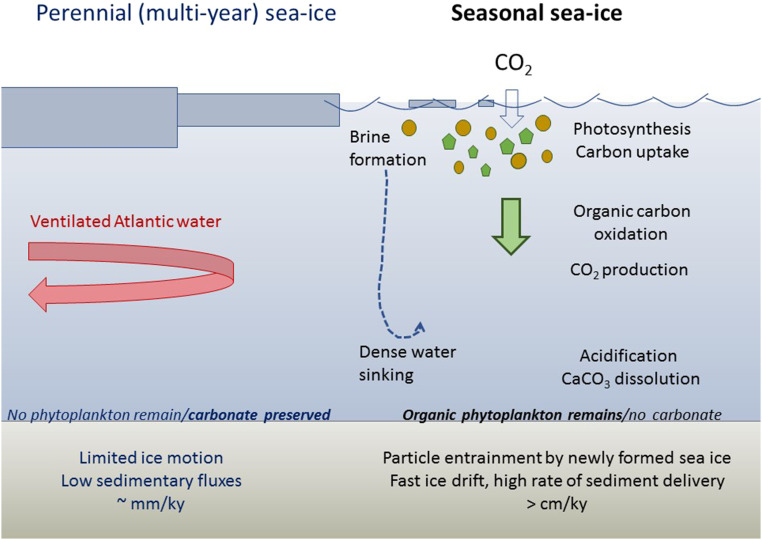

In the southeastern sector of the Lomonosov Ridge, (sites PS87/070–3, PS87/079–3, and PS87/099–4), which experienced an exceptional sea-ice decline in 2007 and 2012 (Fig. 1), core data show significantly different features. First, the preservation of calcareous microfauna is moderate at the surface of the sediment and decreases rapidly a few centimeters below the surface layer, resulting in a fast decrease in foraminifer concentrations downcore (Figs. 2 and 3A). This unfortunately hampers the setting of 14C chronologies from their dating. Second, the few 14C ages, obtained in the upper part of the cores, suggest relatively high sedimentation rates, at least, during the middle-to-late Holocene interval (>3 cm per thousands of years). Third, organic-walled microfossils which relate to phototrophic productivity are present (Fig. 3 A and B) with assemblages largely dominated by Operculodinium centrocarpum (Dataset S4), which is the cyst of a phototrophic dinoflagellate species (35). Hence, in the southeastern sector of the Lomonosov Ridge, close to the Laptev Sea, the biological content and relatively high accumulation rate of sedimentary sequences attest to a significant primary productivity with seasonal sea-ice openings and regrowths. Together, these features point to the occurrence of a first-year ice environment, which is favorable to: i) high fluxes of particles uploaded by sea ice, delivered later on during its seasonal melt (34, 36), ii) primary production at the sea-ice edge with ice-free environments in summer (37), and iii) enhanced atmospheric CO2 uptake rate in the upper ocean and further entrainment from surface to deep ocean with brines during the annual sea-ice regrowth (38). These features also affect alkalinity of the water column and, in conjunction with the oxidation of organic matter at the sea floor, they impact the preservation of biogenic carbonate remains (Fig. 4).

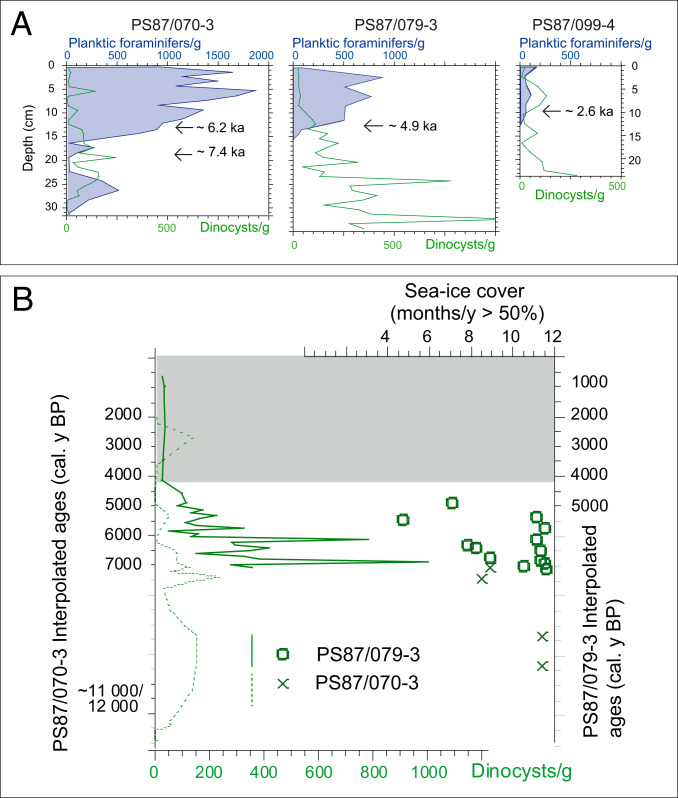

Fig. 3.

(A) Microfossil concentrations (calcareous shells of planktic foraminifers and dinocysts) versus depth in cores PS87/070–3, PS87/079–3, and PS87/099–4 (Datasets S3 and S4). The arrows point to the median age in cal. kyr BP (Dataset S1) at the depths of the transitions toward high biogenic macrofaunal content. (B) Dinocyst concentrations and sea-ice cover reconstructions based on the application of the modern analog technique ref. 40 in cores PS87/070–3 and PS87/079–3 (Dataset S5) reported versus ages estimated from interpolations.

Fig. 4.

Sketch illustrating the contrasted sedimentary environments under perennial versus seasonal sea ice. Perennial sea ice is defined as “the ice that survives the summer and represents the thick component of the sea-ice cover that may include ridged first-year ice” (68) but that may, nevertheless, include some open water representing <10% of ice-covered areas as leads between large ice floes (69).

In cores PS87/070–3 and PS87/079–3 from the southeastern sector of the Lomonosov Ridge, near the Laptev Sea shelf, the vertical distribution of microfossils shows opposite trends upcore with increasing concentration of foraminifers and decreasing concentration of organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts (Fig. 3A). This suggests a major shift in properties of the southeastern Arctic surface water layer between ∼7,000 and 4,000 y ago. The application of the modern analog technique to dinoflagellate cyst assemblages (39, 40) suggests summer sea-ice openings for several months per year until, at least, 5,000 y ago with minimum sea-ice cover recorded between ∼8,000 and 7,000 y ago (Fig. 3 A and B and Dataset S5). Hence, records from the Lomonosov Ridge illustrate a transition from a pattern of, at least, occasional first-year ice, fostering biogenic fluxes ensuing from high phototrophic production, to that of a dominant perennial sea-ice state from the middle Holocene and henceforth (see sketch of Fig. 4). The temporal resolution of the records and the uncertainty of the 14C chronology, however, do not permit us precise assessment on timing of the transition and on the frequency of sea-ice-free conditions. Nevertheless, the microfossil data from sites PS87/070–3, PS87/079–3, and PS87/099–4 illustrate a time-transgressive transition toward perennial sea ice from the pole to the shelf edge that took place from middle-to-late Holocene.

Discussion

All above data illustrate highly contrasted sedimentary regimes in the western and central versus southeastern Lomonosov Ridge areas with distinct conditions of productivity and ambient water mass properties. The spatial boundary that we may draw from the study sites is east of the North Pole; it probably migrated south toward the Laptev Sea shelf edge during the middle-to-late Holocene. A spatial boundary of the sea-ice edge across the central Arctic Ocean can be associated with the dipole pattern, which has accompanied the reduction of the multiyear pack ice in the Arctic Ocean during the past decades (41, 42).

Coupled model experiments exploring the role of oceanic-heat transport from the Atlantic and the Pacific and that of the Arctic dipole on low-frequency variations in the Arctic sea-ice dynamics, have shown that the positive phase of the Arctic dipole results in warming with a summer decline in sea ice on the Pacific side versus opposite changes on the Atlantic side (43). Such an opposition between the Pacific and the Atlantic sectors of the Arctic Ocean was a characteristic of some episodes of the past and may account for the documented regional discrepancies. In particular, the interval between ∼6 and 3 ky ago was marked by generally reduced sea-ice cover in the Chukchi Sea and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (17, 21, 44, 45), whereas the middle-to-late Holocene corresponds to a time of increased sea ice in the eastern Arctic including the northeast Greenland margins (46, 47), the Fram Strait area (22, 26, 48), the north of Svalbard (49) and the coastal Laptev Sea, from the shelf (19) to offshore locations as illustrated in the present study.

Our new data show positive evidence for some sea-ice opening in the southeastern part of the central Arctic Ocean, during the early and middle Holocene, at least, sporadically. They also show that sea-ice cover variations through time may differ significantly in the southeastern versus western and central Arctic Ocean and in the circum-Arctic marginal seas. Whereas these data illustrate a regional behavior of the Arctic sea ice on a decadal to the millennial timescale, they also lead to discard any scenario of its uniform response to climate and paleogeographic variations in the recent geological past. Our findings can be used for tests of confronting reconstructions of the behavior from coupled models, such as those used in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) applied for simulating, in particular, the climate of the middle Holocene (6 ka) as well for future climate scenarios (50, 51). In an, at least, partial contradiction with the proxy-based reconstructions illustrated above, the Arctic sea ice at 6 ka as simulated with CMIP5 models shows an extent similar to the present one with generally a slightly less extended sea-ice cover over Arctic shelves due to radiative forcing from the prescribed summer insolation, which was still higher than at present (52). In addition, all models show perennial sea ice in the central Arctic, north of 80°N, during the middle Holocene, and all show a rather symmetrical distribution around the pole in summer. Although some models succeed to simulate thicker sea ice in the western portion of the Arctic, most failed to reproduce sea-ice reduction in the southeastern sector of the central Arctic Ocean as documented by proxy data. In a sensitivity experiment testing the transient effect of insolation variations over millennia, a coupled atmosphere-sea and ice-ocean column model showed reduction of the Arctic summer sea ice during the early Holocene but without any regional disparity as the forcing was spatially averaged for the simulation (53). Hence, the proxy results point to some aspects to improve in current coupled models, notably to reproduce spatial heterogeneity either linked to gateway properties or to the Arctic dipolar pattern, which has been recognized as an important component in the modern sea-ice behavior (43). The Arctic dipole deserves attention from data-based or proxy-data reconstructed hydrographic conditions as well as from process models and predictive climate models as it corresponds to a synoptic scenario that likely occurred during the early and middle Holocene and could well characterize the Arctic sea-ice dynamics under warm climate conditions.

The warm climate conditions of early-to-middle Holocene recorded in the North Atlantic regions are usually associated with the insolation forcing (e.g., refs. 9 and 54). In addition to insolation, the paleogeography of the Arctic Ocean and the relative sea level have to be taken into consideration not only because the water depth controls fluxes from the Pacific to the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait as well as that of the Atlantic waters through the Barents Sea, but also because the immerged Russian shelves are a main locus for Arctic sea-ice production (55). Hence, the flooding of the Russian Arctic shelves related to sea-level rise, and some regional glacioisostatic adjustments during early postglacial times may have played an important role, notably in the eastern Siberian and Laptev seas where the modern coastline established between 7.5 and 5 ka (56, 57), likely synchronously with the 6-ka optimum and later states of the global sea level within 20 cm of the present level (58). Therefore, it is very likely that the increase in sea-ice cover over the southeastern Arctic after 7 ka was fostered by a higher sea-ice production, in its turn, fostered by the flooding of the Arctic shelves. Coupled atmosphere–ocean–sea–ice model experiments (59) support this interpretation. This leads us to suggest that the submerged Arctic shelf extent controlled by sea level acts as a primary forcing for Arctic sea-ice dynamics, which, in turn, plays a critical role on climate, notably because of the Arctic amplification. From this point of view, the global cooling trend from the early-to-late Holocene, that is largely associated with temperature decrease in the North Atlantic (54), could have been amplified by enhanced rates of Arctic sea-ice formation resulting from the submergence of the Laptev and East Siberian sea shelves, leading to increased length of the Arctic coastline and total size of the sea-ice producing polynya. The boundary condition set by the sea-level control of the Arctic sea-ice dynamics could be hypothesized as one mechanism not yet integrated in coupled models that might partly explain the Holocene temperature conundrum (60).

Highly resilient perennial sea ice on long timescales characterizes the Arctic Ocean (61–65). However, seasonal sea-ice cover in the eastern Arctic may have been a recurrent feature during warm episodes of the past, notably during the early–middle Holocene which was also a time of transition with respect to global sea level and insolation at high latitudes. The recent minima in Arctic sea-ice cover are likely driven by anthropogenic forcing (66), but nearly similar changes responding to other forcings occurred over hundreds to thousands of years in the past, i.e., with a similar geographic pattern marked by thinner–younger ice in the southeastern sector of the Arctic Ocean. Hence, the episodic sea-ice-free condition in summer over the Russian Arctic could be part of the natural variability under warm climate conditions and could possibly become a dominant mode in the future due to global warming and its Arctic amplification.

Methods

AMS-14C Chronology.

The 14C dating was made from planktic foraminifer shells populations of Neogloboquadrina pachyderma (Np) collected in the 150–250-μm fraction after sieving of 1-cm slices of sediment. Processing and measurements were performed at the AMS facility of the A.E. Lalonde Laboratory at the University of Ottawa. Measurements were made on subsamples containing >10 mg of biogenic carbonate. Following standardized procedures, the ages were calculated using the Libby 14C half-life of 5,568 y. A δ R (∆R) of 440 ± 138 y was applied using reference data from the Canadian Arctic as reported in the marine13 reservoir database (70). This ∆R is consistent with data from measurements of recent shells collected in the Canadian Arctic (71), but it is lower than what was proposed based on correlations in Arctic cores (72). The calibration to calendar ages was performed using the OxCal v4.2.4 software (73). The calibrated ages are reported according to a 95% confidence interval (Dataset S1).

Beyond the intrinsic error with 14C measurements, the main sources of uncertainty to set an absolute chronology include the biological mixing that may smooth the records and changes in the 14C marine reservoir ages (74) in addition to sea-floor diagenesis (75). Here, mixing depths were estimated based on the penetration of lead 210 excesses above parent radium 226 (76). They range from 0 to 3.5 cm from North to South (Dataset S2). When several 14C measurements were performed within the mixed layer estimates from 210Pb, they yielded identical radiocarbon ages (e.g., PS87/030–2), thus, supporting the 210Pb estimates.

Foraminiferal and Microfossil Counts.

Micropaleontological preparation was performed at 1-cm intervals from subsamples of about 10 cm3. The treatments included wet sieving at 106 µm, the fine fraction being used for palynological preparation and the coarse fraction for microfossil counts under binocular. In the coarse fraction, the main categories of microfossils counted include planktic and benthic foraminifers, ostracods, echinoderm spines and plates, and sponge spicules (Dataset S3). Other microfossils, such as radiolarians, pteropods, and small size bivalve shells occur in rare numbers. A list of microfossil taxa in the sand fraction of surface sediments collected on the Lomonosov Ridge during the PS87 expedition is available from the cruise report (31) and another data report (77); downcore foraminiferal and ostracod data from core PS87-30 were reported by Zwick (78). Among microfossils counted for this and reported here, planktic foraminifers dominate with assemblages mostly composed of Np. Benthic foraminifers are common and dominated by calcareous forms with rare agglutinated taxa.

Palynology and Dinocyst Counts and Tentative Sea-Ice Cover Estimates.

Subsampling of about 10 cm3 of wet sediment was performed at 1-cm intervals for micropaleontology and palynology (see above). Palynological preparation was performed following the standardized protocol (79). The subsamples were weighted and sieved at 106 and 10 μm after adding Lycopodium clavatum spore tablets for further estimation of palynomorph concentrations. The dried >106-μm fraction was used for micropaleontological analyses as described above and for picking foraminifers for 14C measurements. The 10–106-μm fraction was treated with HCl (10%) and HF (49%) to dissolve carbonate and silica particles. The residue was concentrated on a 10-µm nylon mesh and mounted on microscope slides with gelatin. Because of low concentrations, at least, one slide was scanned for each sample. The number of palynomorphs recovered is very low, and many samples are barren. The counts of dinocyst specimens is reported in Dataset S4. In some samples from cores located southeast of the Lomonosov Ridge (PS87/070–3, PS87/079–3, and PS87/099–4), however, dinocysts occur in relatively high numbers with concentrations on the order of 102–103 cysts/g. In the samples with concentrations >102 cysts/g, we tentatively reconstructed sea-ice cover with the modern analog technique (40, 80) applied to the n = 1,968 dinocyst database, which includes a large number of reference data points from Arctic and subarctic sea-ice environments (81). The “modern” sea-ice data consist in monthly averages from 1955 to 2012 as compiled from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (82). The leave-one-out technique indicates errors of ±12% for annual sea-ice concentrations and ±1.5 ms/y for seasonal duration of sea ice. Beyond such metrics of statistic error, uncertainties include possible lateral transport and poor preservation of some dinocyst taxa sensitive to oxidation (83, 84). Regardless, uncertainties related to taphonomical processes, the sea-ice cover estimates from dinocyst assemblages yield values corresponding to close modern analogs (Dataset S5). Dinocyst assemblages indicate productivity in the dense sea-ice cover environment with short-lived seasonal opening of sea ice, whereas samples with very low dinocyst concentrations likely relate to extremely low pelagic productivity and perennial sea ice (40, 81).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the team of the A.L. Lalonde AMS Laboratory of the University of Ottawa for helping with 14C measurements. We gratefully thank Captain Schwarze and his crew of RV Polarstern for the excellent support and cooperation during the entire cruise. We thank the PS87 Geoscience Party for support in getting geological shipboard data and sediments during the expedition. The study used samples and data provided by Alfred Wegener Institute (Grant AWI-PS8701). This study was supported by several awards from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Nature et Technologie. All other analyses were performed in the Geotop Laboratories at the Université du Québec à Montréal.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. T.M.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2008996117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and in Datasets S1–S5.

References

- 1.Serreze M. C., Barry R. G., Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: A research synthesis. Global Planet. Change 77, 85–96 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis J. A., Vavrus S. J., Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L06801 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen J. et al., Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deser C., Sun L., Tomas R. A., Screen J., Does ocean coupling matter for the northern extratropical response to projected Arctic sea ice loss? Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2149–2157 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swart N., Natural causes of Arctic sea-ice loss. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 239–241 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinnard C. et al., Reconstructed ice cover changes in the Arctic during the past millennium. Nature 479, 509–512 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zachos J., Pagani M., Sloan L., Thomas E., Billups K., Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–693 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zachos J. C., Dickens G. R., Zeebe R. E., An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 451, 279–283 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renssen H., Seppä H., Crosta X., Goosse H., Roche D. M., Global characterization of the Holocene thermal maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 48, 7–19 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vernal A., Gersonde R., Goosse H., Seidenkrantz M.-S., Wolff E. W., Sea ice in the paleoclimate system: The challenge of reconstructing sea ice from proxies–An introduction. Quat. Sci. Rev. 79, 1–8 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein R., The late Mesozoic‐Cenozoic Arctic Ocean climate and sea ice history: A challenge for past and future scientific ocean drilling. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 1851–1894 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nørgaard-Pedersen N. et al., Arctic Ocean during the last glacial maximum: Atlantic and polar domains of surface water mass distribution and ice cover. Paleoceanography 18, 1063 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillaire-Marcel C., de Vernal A., Polyak L., Darby D., Size-dependent isotopic composition of planktic foraminifers from Chukchi Sea vs. NW Atlantic sediments–Implications for the Holocene paleoceanography of the western Arctic. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 245–260 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillaire-Marcel C. et al., A new chronology of late Quaternary sequences from the central Arctic Ocean based on “extinction ages” of their excesses in 231Pa and 230Th. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 18, 4573–4585 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vernal A., Hillaire-Marcel C., Darby D., Variability of sea ice cover in the Chukchi Sea (western Arctic Ocean) during the Holocene. Paleoceanography 20, PA4018 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vernal A. et al., Dinocyst-based reconstructions of sea ice cover concentration during the Holocene in the Arctic Ocean, the northern North Atlantic Ocean and its adjacent seas. Quat. Sci. Rev. 79, 111–121 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer J. R. et al., Western Arctic Ocean temperature variability during the last 8000 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L24602 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bringué M., Rochon A., Late Holocene paleoceanography and climate variability over the Mackenzie slope (Beaufort Sea, Canadian Arctic). Mar. Geol. 291–294, 83–96 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hörner T., Stein R., Fahl K., Birgel D., Post-glacial variability of sea ice cover, river run-off and biological production in the western Laptev Sea (Arctic Ocean)–A high-resolution biomarker study. Quat. Sci. Rev. 143, 133–149 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hörner T., Stein R., Fahl K., Paleo-sea ice distribution and polynya variability on the Kara Sea shelf during the last 12 ka. Arktos 4, 6 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein R. et al., Holocene variability in sea ice cover, primary production, and Pacific-Water inflow and climate change in the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas (Arctic Ocean). J. Quaternary Sci. 32, 362–379 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller J. et al., Holocene cooling culminates in sea ice oscillations in Fram Strait. Quat. Sci. Rev. 47, 1–14 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belt S. T. et al., Identification of paleo Arctic winter sea ice limits and the marginal ice zone: Optimised biomarker- based reconstructions of late Quaternary Arctic sea ice. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 431, 127–139 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibb O. T., Steinhauer S., Fréchette B., de Vernal A., Hillaire-Marcel C., Diachronous evolution of sea surface conditions in the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay since the last deglaciation. Holocene 25, 1882–1897 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berben S. M. P., Husum K., Navarro-Rodriguez A., Belt S. T., Aagaard-Sørensen S., Semi-quantitative reconstruction of early to late Holocene spring and summer sea ice conditions in the northern Barents Sea. J. Quaternary Sci. 32, 587–603 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falardeau J., de Vernal A., Spielhagen R. F., Paleoceanography of northeastern Fram Strait since the last glacial maximum: Palynological evidence of large amplitude change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 195, 133–152 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allan E. et al., Late Holocene sea-surface instabilities in the Disko Bugt area, west Greenland, in phase with 18O-oscillations at Camp Century. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 227–238 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saini J. et al., Holocene Variability in Sea Ice and Primary Productivity in the Northeastern Baffin Bay, (Arktos, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serreze M. C., Stroeve J., Arctic sea ice trends, variability and implications for seasonal ice forecasting. Philos. Trans. R Soc. A 373, 20140159 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fetterer F., Knowles K., Meier W. N., Savoie M., Windnagel A. K., updated daily. Sea Ice Index, (Version 3, NSIDC: National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, Colorado USA, 2017). https://nsidc.org/data/G02135/versions/3. Accessed 1 November 2018.

- 31.R. Stein and onboard participants, The Expedition PS87 of the Research Vessel Polarstern to the Arctic Ocean in 2014. 10.2312/BzPM_0688_2015. Accessed 23 May 2016. [DOI]

- 32.Roberge P., “Les otolithes des sédiments de surface de la ride de Lomonosov” (BSc research report, University du Québec à Montréal, 2017), p. 19.

- 33.Clark D. L., Whitman R. R., Morgan K. A., Mackey S. D., “Stratigraphy and glacial-marine sediments of the Amerasian Basin, central Arctic Ocean” in Stratigraphy and glacial-marine sediments of the Amerasian Basin, central Arctic Ocean, (Geological Society of America, 1980), Vol. 181, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darby D. A. et al., The role of currents and sea ice in both slowly deposited central Arctic and rapidly deposited Chukchi-Alaskan margin sediments. Global Planet. Change 68, 58–72 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthiessen J. et al., Modern organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts in Arctic marine environments and their (paleo-) environmental significance. Palaontol. Z. 79, 3–51 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polyak L. et al., History of sea ice in the Arctic. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1757–1778 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vancoppenolle M. et al., Role of sea ice in global biogeochemical cycles: Emerging views and challenges. Quat. Sci. Rev. 79, 207–230 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates N. R., Moran S. B., Hansell D. A., Mathis J. T., An increasing CO2 sink in the Arctic Ocean due to sea-ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23609 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vernal A. et al., Dinoflagellate cyst assemblages as tracers of sea-surface conditions in the northern North Atlantic, Arctic and sub-Arctic seas: The new “n = 677” database and application for quantitative paleoceanographical reconstruction. J. Quaternary Sci. 16, 681–699 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Vernal A. et al., Reconstructing past sea ice cover of the Northern hemisphere from dinocyst assemblages: Status of the approach. Quat. Sci. Rev. 79, 122–134 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe E., Wang J., Sumi A., Hasumi H., Arctic dipole anomaly and its contribution to sea ice export from the Arctic Ocean in the 20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23703 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Overland J. E., Wang M., Large-scale atmospheric circulation changes are associated with the recent loss of Arctic sea ice, Tellus A. Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 62, 1–9 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li D., Zhang R., Knutson T., Comparison of mechanisms for low-frequency variability of summer Arctic sea ice in three coupled models. J. Clim. 31, 1205–1226 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dyke A. S., Hooper J., Savelle J. M., A history of sea ice in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago based on postglacial remains of the Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus). Arctic 49, 235–255 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Vernal A., Variability of Arctic sea-ice cover at decadal to millennial scales: The proxy records. PAGES Newslett. 25, 143–145 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Funder S. et al., A 10,000-year record of Arctic Ocean sea-ice variability–View from the beach. Science 333, 747–750 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kolling H., Stein R., Fahl K., Perner K., Moros M., Short-term variability in late Holocene sea-ice cover on the East Greenland Shelf and its driving mechanisms. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 485, 336–350 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Syring N. et al., Holocene changes in sea-ice cover and polynya formation along the northern NE-Greenland shelf: New insights from biomarker records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 231, 106173 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brice C., de Vernal A., Ivanova E., van Bellen S., van Nieuwenhove N., Palynological evidence of sea-surface conditions in the Barents Sea, off northeast Svalbard during the postglacial. Quat. Res. (2020) in press. [Google Scholar]

- 50.IPCC , “Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change”, Stocker T. F., Ed. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge, UK, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kageyama M. et al., The PMIP4 contribution to CMIP6–Part 1: Overview and over-arching analysis plan. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 1033–1057 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goosse H., Roche D. M., Mairesse A., Berger M., Modelling past sea ice changes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 79, 191–206 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stranne C., Jakobsson M., Björk G., Arctic Ocean perennial sea ice breakdown during the early Holocene insolation maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 92, 123–132 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcott S. A., Shakun J. D., Clark P. U., Mix A. C., A reconstruction of regional and global temperature for the past 11,300 years. Science 339, 1198–1201 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura T., Ohshima K. I., Mapping of sea ice production in the Arctic coastal polynyas. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C07030 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bauch H. et al., Chronology of the Holocene transgression at the North Siberian margin. Global Planet. Change 31, 125–139 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taldenkova E. et al., History of ice-rafting and water mass evolution at the northern Siberian continental margin (Laptev Sea) during late glacial and Holocene times. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 3919–3935 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambeck K., Rouby H., Purcell A., Sun Y., Sambridge M., Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 15296–15303 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blaschek M., Renssen H., The impact of early Holocene Arctic shelf flooding on climate in an atmosphere–ocean–sea–ice model. Clim. Past 9, 2651–2667 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu Z. et al., The Holocene temperature conundrum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E3501–E3505 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Polyak L., Best K. M., Crawford K. A., Council E. A., St-Onge G., Quaternary history of sea ice in the western Arctic Ocean based on foraminifera. Quat. Sci. Rev. 79, 145–156 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knies J. et al., The emergence of modern sea ice cover in the Arctic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 5, 5608 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein R. et al., Evidence for ice-free summers in the late Miocene central Arctic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 7, 11148 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein R., Fahl K., Gierz P., Niessen F., Lohmann G., Arctic Ocean sea ice cover during the penultimate glacial and the last interglacial. Nat. Commun. 8, 373 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clotten C. et al., On the causes of Arctic sea ice in the warm Early Pliocene. Sci. Rep. 9, 989 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Notz D., Stroeve J., Observed Arctic sea-ice loss directly follows anthropogenic CO2 emission. Science 354, 747–750 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jakobsson M. et al., The international bathymetric chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO) version 3.0. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L12609 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Comiso J. C., Large decadal decline of the Arctic multiyear ice cover. J. Clim. 25, 1176–1193 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spielhagen R. F. et al., Arctic Ocean deep-sea record of northern Eurasian ice sheet history. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 1455–1483 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reimer P. J. et al., IntCal13 and MARINE13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0-50000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coulthard R. D. et al., New marine ΔR values for Arctic Canada. Quat. Geochronol. 5, 419–434 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hanslik D. et al., Quaternary Arctic Ocean sea-ice variations and radiocarbon reservoir age corrections. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 3430–3441 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramsey C. B., Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hughen K. A., “Radiocarbon dating of deep-sea sediments” in Proxies in Late Cenozoic Paleoceanography, Hillaire-Marcel C., de Vernal A., Eds. (Elsevier, 2007), pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wycech J., Kelly D. C., Marcott S., Effects of seafloor diagenesis on planktic foraminiferal radiocarbon ages. Geology 44, 551–554 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Le Duc C., “Flux sédimentaires le long de la ride de Lomonosov, Océan Arctique” (Memoir MSc, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2018).

- 77.Zwick M. M., “Reconstruction of water mass characteristics on the western Lomonosov Ridge (Central Arctic Ocean),” MSc Memoir, (Bremen Universität, Bremen, 2016), p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zwick M. M., Matthiessen J., Wollenburg J., ARK-XXVIII/4 shipboard scientific party, Quantitative micropaleontological and sedimentary facies analysis of surface samples from the Lomonosov Ridge. Poster for PAST Gateways 2015. 10.13140/RG.2.1.2244.9682 (2015).

- 79.de Vernal A., Bilodeau G., Henry M., “Micropaleontological preparation techniques and analyses” (Cahier du Geotop n 3, Geotop, Montréal, 2010).

- 80.Guiot J., de Vernal A., “Transfer functions: Methods for quantitative paleoceanography based on microfossils” in Proxies in Late Cenozoic Paleoceanography, Hillaire-Marcel C., de Vernal A., Eds. (Developments in Marine Geology, Elsevier, 2007), Vol. vol. 1, pp. 523–563. [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Vernal A. et al., Distribution of common modern dinocyst taxa in surface sediments of the Northern Hemisphere in relation to environmental parameters: The new n = 1968 database. Mar. Micropaleontol. 159, 101796 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walsh J. E., Chapman W. L., Fetterer F., Updated 2016. Gridded Monthly Sea Ice Extent and Concentration, 1850 Onward, (Version 1, NSIDC National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, Colorado, 2015), 10.7265/N5833PZ5. Accessed 1 November 2018. [DOI]

- 83.Zonneveld K. A. F., Versteegh G. J. M., Kodrans-Nsiah M., Preservation and organic chemistry of late Cenozoic organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts: A review. Mar. Micropaleontol. 86, 179–197 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zonneveld K. A. F., Ebersbach F., Maeke M., Versteegh G. J. M., Transport of organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts in nepheloid layers off Cape Blanc (N-W Africa). Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 139, 55–67 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and in Datasets S1–S5.