Abstract

Background

Health interventions aimed at facilitating connectedness among seniors have recently gained traction, seeing as social connectedness is increasingly being recognized as an important determinant of health. However, research examining the association between connectedness and health across all age groups is limited, and few studies have focused on community belonging as a tangible aspect of social connectedness. Using a population-based Canadian cohort, this study aims to investigate (1) the associations between community belonging with self-rated general health and self-rated mental health, and (2) how these associations differ across life stages.

Methods

Data from six cycles of a national population health survey (Canadian Community Health Survey) from 2003 to 2014 were combined. Multinomial logistic regressions were run for both outcomes on the overall study sample, as well as within three age strata: (1) 18–39, (2) 40–59, and (3) ≥ 60 years old.

Results

Weaker community belonging exhibited an association with both poorer general and mental health, though a stronger association was observed with mental health. These associations were observed across all three age strata. In the fully adjusted model, among those reporting a very weak sense of community belonging, the odds of reporting the poorest versus best level of health were 3.21 (95% CI: 3.11, 3.31) times higher for general health, and 4.95 (95% CI: 4.75, 5.16) times higher for mental health, compared to those reporting a very strong sense of community belonging. The largest effects among those reporting very weak community belonging were observed among those aged between 40 and 59 years old.

Conclusion

This study contributed to the evidence base supporting life stage differences in the relationship between community belonging and self-perceived health. This is a starting point to identifying how age-graded differences in unmet social needs relate to population health interventions.

Keywords: Community belonging, Social connectedness, Self-rated health, Mental health, Life stages, Population health

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CCHS, Canadian Community Health Survey; CI, confidence interval

Highlights

-

•

Community belonging is associated with self-rated health at all ages.

-

•

Community belonging is more strongly associated with mental versus general health.

-

•

Weak community belonging is most strongly associated with self-rated health in middle-age.

-

•

Social connectedness interventions should be aimed at all age groups.

1. Introduction

Forming and maintaining social relationships has long been considered paramount to human motivation and well-being (Bowlby, 1969; Maslow, 1954; Sarason, 1974). Maslow (1954) places only physiological needs and safety before our need for belonging; Baumeister and Leary (1995) similarly describe belonging as a fundamental human motivation. The association between social connectednesswith both our physical and mental health has been reflected in a number of studies on social capital (Berkman, 1995, Berkman and Syme, 2017, Fisher et al., 2004, House et al., 1988, Hystad and Carpiano, 2012, Kim and Kawachi, 2017, Lochner et al., 2003, Ross, 2002, Shields, 2008). This body of evidence falls in line with a social ecological model of health, which posits that individual health is shaped by micro-, meso-, and macro-level social contexts. Under this framework, health is determined by social contexts ranging from micro-level relationships with family and peers, to meso-level neighbourhood factors, to macro economic and societal structures (Kim & Kawachi, 2017; Richard et al., 2011).

The importance of our meso-level social contexts in relation to health has been highlighted in studies on neighbourhood cohesion, which have shown associations with reduced risk for stroke, cardiovascular events, and mortality (Inoue et al., 2013, Kawachi, Subramanian, & Kim, 2008, Kim et al., 2014). Sense of community belonging describes the degree to which individuals are (or judge themselves to be) connected to their community and their place within it (Tartaglia, 2006), which has also been shown to be associated with health (Carpiano and Hystad, 2011, Kitchen et al., 2012). This 1-item question is a parsimonious measure that captures multiple dimensions of the meso-social context, encompassing both social relations and neighbourhood characteristics (Schellenberg et al., 2018). McMillan and Chavis (1986) point to two reasons a strong sense of community belonging can positively influences health outcomes: first, a greater sense of community may translate into a higher likelihood of people mobilizing participatory processes for the solution of their problems. Second, community belonging and engagement contributes to quality of life which results in a greater sense of identity and confidence, opposing anonymity and loneliness. Measuring community belonging can provide researchers and policymakers with insight into meso-level social contexts, which can be helpful for social and health interventions. Given the parsimony of this single item measure, it can be more easily incorporated into surveys in the face of length and budgetary restraints.

These ideas have recently fostered attention and support regarding social prescription for socially isolated older adults (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Iredell et al., 2004, Pescheny, Randhawa, & Pappas, 2020) . This practice in the clinical setting advantageously considers how meso-level contexts influence health but can be criticized for being reactionary. Integrating an upstream prevention framework that targets all age groups may more effectively ensure social needs continue to be met throughout life before the development of any adverse outcomes.

Given that ageing involves transitions into and out of different social roles, consideration for age-graded difference is warranted. The social roles we adopt throughout life vary according to network composition and resource constraints (i.e. amount of time we have to spend with others). For instance, young adulthood is generally characterized by instability and seeking social and behavioural approval (Buijs, Jeronimus, Lodder, Steverink, & Jonge, 2020). Mid-life is considered both a period of peak functioning and of crisis consisting of a complex interplay of differing roles amid physical and psychological changes associated with ageing. Old adulthood is associated with a loss of social networks, while other studies highlight the increased time adults have in this stage to engage with family, friends, and their community (Lachman, 2004, Ulloa et al., 2013). Given these changing contexts, the strength of our need for belonging may vary as we age. Moreover, how we most effectively fill these needs may also change.

Thus, drawing from two theoretical underpinnings that (1) community belonging is important for health, and (2) there are age-graded differences in our belonging need fulfillment, our objective was two-pronged: first, we aimed to investigate the associations between community belonging with self-rated general health and self-rated mental health. Second, we examined how these associations differed across three commonly distinguished developmental stages in adulthood: young adulthood, middle-age, and older adulthood.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

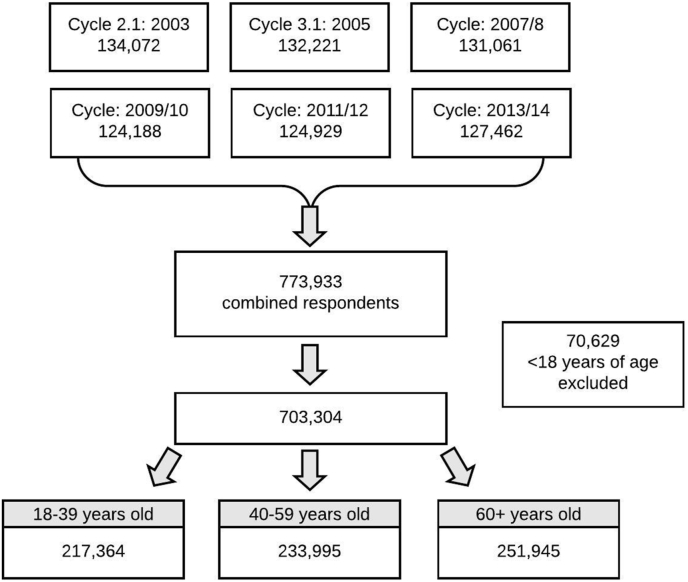

This study used data from six cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Respondents over the age of 18 from CCHS cycles for years 2003, 2005, 2007–08, 2009–10, 2011–12, 2013-14 were combined to increase sample size, cumulating to a total of 703,304 observations (N = 217,364 18 to 39 year-olds, N = 233,995 40 to 59 year-olds, N = 251,945 60 year-olds and over).

The CCHS is a cross-sectional national survey administered by Statistics Canada to Canadians over 12 years of age living in private dwellings. People living on Crown lands, residents of Indigenous communities, those living in institutions, fulltime members of the Canadian forces, and some remote communities are excluded from the survey. The CCHS uses multistage stratified cluster sampling to collect information concerning health determinants and outcomes and has a response rate ranging from 63% to 78.5%. Detailed methodology concerning sampling and survey design is available elsewhere (Beland, 2002; Statistics Canada, 2007).

Informed consent was obtained by Statistics Canada for all survey participants.

Ethics approval for the use of this data is covered by the publicly available data clause, which does not require review or approval by a research ethics board.

-

a.

Variable definitions

The focal exposure is sense of community belonging. CCHS respondents were asked, “How would you describe your sense of belonging to your local community? Would you say it is:” with response options: very strong, somewhat strong, somewhat weak, and very weak. This measure of community belonging has been shown to be positively associated with a variety of forms of social capital including having close friends in the local community, and having a larger number of neighbours one knows well enough to ask for a favour (Carpiano & Hystad, 2011). A construct validity study showed that this 1-item question describes multidimensional factors related to local social relations, neighbourhood satisfaction, and place attachment (Schellenberg et al., 2018).

Two outcomes were analyzed. The first outcome, self-rated health, prompts survey participants with “In general, would you say your health is:” with response options: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor. The second outcome, self-rated mental health, prompts survey respondents with “In general, would you say your mental health is:” with the same response options. For both outcome measures, excellent and very good responses were collapsed into one category, as were fair and poor due to perceived minimal differences between the two categories. Thus, three response categories were used for each of the two outcomes: excellent/very good health, good health, and fair/poor health. The predictive validity of self-rated measures of health has been shown to be a reliable measure of both physical and mental health (across the spectrum of health outcomes), and predictive of future adverse health events (Baćak & Ólafsdóttir, 2017; Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Schnittker & Bacak, 2014).

For the age stratified analyses, three commonly distinguished developmental stages in adulthood were defined: young adulthood (18–39 years), middle-age (40–59 years), and old adulthood (60 years of age and older).

All other covariates were captured from self-reported survey questions: sex, immigrant status, household income, height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Self-reported income measures were equivalized by dividing total household income by the square root of household size which was then categorized into quintiles. BMI was categorized into quintiles according to the World Health Organization (2006) international standards for adults. Respondents were categorized as current, former, or non-smokers based on current smoking status and whether they have cumulatively smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Alcohol consumption was categorized as no past-year, occasional if consuming an alcoholic beverage once a month or less was reported, regular if consuming an alcoholic beverage twice a month or more, and a regular plus binge if consuming more than twice a month plus having had more than 5 drinks on one occasion in the past year. Physical activity was based on the low-intensity value of the metabolic equivalents (MET) measure, and respondents were categorized by Statistics Canada as active, moderately active, or inactive.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Participants under the age of 18 were excluded from analyses. The grouped age variable for cycle 2.1 was categorized differently compared to all proceeding cycles (12–19; 20–24 years versus 12–17; 18–24 years). In order to exclude all respondents under 18, cycle 2.1 respondents in the 12–19 group were assigned a random age to determine inclusion or exclusion.

For missing observations, the median value was imputed as all measures had <6.0% missing except for the income measure, which had 10.3% of observations missing (Harrell, 2001). For income, we ran a sensitivity analysis including the missing observations by categorizing them as a separate group.

The distributions of baseline demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioural characteristics were described in the overall sample, as well as by level of community belonging.

The proportional odds assumption did not hold, and thus, multinomial logistic regression models were used. Two separate multinomial logistic regressions were run for (1) self-rated general health (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor), and (2) self-rated mental health (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor) on the overall study sample, as well as stratified by three age strata: (1) 18–39, (2) 40–59, and (3) ≥ 60 years old. Unadjusted and fully adjusted models were used to quantify the association between sense of community belonging and the odds of reporting either good or fair/poor health, compared to reporting excellent/very good health.

We study the association after adjustment for other sociodemographic and behavioural factors. We adjusted for health behaviours and BMI to show that the association between community belonging and health persists beyond conceptualizations that community belonging impacts health solely due to behavioural changes or maintenance of health norms through informal social control. We also for survey cycle in the multivariable model. As a robustness check, an additional interaction model testing for an interaction between sense of community belong and age strata was run. A sensitivity analysis running all final models on each individual survey cycles was completed to ensure consistency between survey cycles and that the large size of the pooled sample was not driving the statistical significance of the results (Supplement Table 1).

The fully adjusted model included age group, sex, survey cycle, immigrant status, household income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and BMI. We adjusted for sex in all models and also ran a sensitivity analysis to determine if our findings were different according to sex using stratified models.

Normalized survey weights were applied to the analyses to account for complex survey design and produce more generalizable population-based estimates (Thomas & Wannell, 2009). Weighted 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all estimates. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort characteristics

After merging six CCHS cycles and excluding respondents <18 years of age, the total analytic sample size was 703,304 individuals (Fig. 1). Of the weighted sample, 16.1% reported a very strong sense of community belonging, 48.8% reported a somewhat strong sense, 26.0% reported a somewhat weak sense, and 9.1% reported a very weak sense. In terms of self-rated general health, 58.7% reported excellent or very good health, 29.3% reported good health, and 12.0% reported fair or poor health. Regarding self-rated mental health, 73.4% reported excellent or very good, 21.2% reported good, and 5.4% reported fair or poor mental health.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study participants from combined CCHS cycles (2003–2014).

In general, women were slightly more likely than men to report a stronger sense of community belonging. Older age groups, immigrants, and those in lower income quintiles were more likely to report a very strong sense of community. Being a non- or former smoker also increased the likelihood of reporting a very strong sense; current smokers were most likely to report a very weak sense of belonging. In terms of alcohol consumption, non-drinkers were most likely to report either a very strong or a very weak sense of belonging; occasional drinkers were most likely to report a very weak sense. Regular drinkers were most likely to report a very strong sense, and regular plus binge drinkers a somewhat weak sense. Physical activity levels showed a positive correlation: those who were active were most likely to report a strong sense of belonging. The highest and lowest BMI groups were both more likely to report a very weak sense of belonging (Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighteda proportion (%) and mean characteristics according to sense of community belonging.

| Characteristic | Sense of community belonging |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 703,304) | Very strong (n = 134,618) | SW strong (n = 349,972) | SW weak (n = 161,499) | Very weak (n = 57,215) | |

|

SRH | |||||

| Excellent/very good | 58.7 | 63.7 | 59.9 | 56.9 | 48.2 |

| Good | 29.3 | 25.9 | 29.2 | 31.3 | 30.9 |

| Fair/poor |

12.0 |

10.4 |

10.9 |

11.8 |

20.8 |

|

SRMH | |||||

| Excellent/very good | 73.4 | 80.3 | 76.0 | 68.8 | 60.7 |

| Good | 21.2 | 16.4 | 20.2 | 24.5 | 25.9 |

| Fair/poor |

5.4 |

3.3 |

3.8 |

6.7 |

13.4 |

|

Sex | |||||

| Female | 50.9 | 51.9 | 51.0 | 50.1 | 50.7 |

| Male |

49.1 |

48.2 |

49.0 |

49.9 |

49.3 |

|

Age group | |||||

| 18–24 | 11.8 | 8.1 | 11.6 | 13.9 | 13.9 |

| 25–29 | 8.7 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 11.1 | 11.0 |

| 30–39 | 17.4 | 13.7 | 17.3 | 19.8 | 17.9 |

| 40–49 | 19.8 | 19.1 | 20.2 | 19.9 | 18.0 |

| 50–59 | 18.2 | 19.3 | 18.1 | 17.7 | 18.3 |

| 60–69 | 12.7 | 16.5 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 11.5 |

| 70–79 | 7.7 | 11.7 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 6.2 |

| 80+ |

3.8 |

5.7 |

4.1 |

2.2 |

3.3 |

|

CCHS Cycle | |||||

| 2003 | 15.4 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 16.1 |

| 2005 | 15.9 | 16.0 | 15.6 | 15.9 | 17.1 |

| 2007 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 16.3 | 16.1 | 17.9 |

| 2009 | 17.0 | 17.2 | 17.0 | 16.8 | 17.0 |

| 2011 | 17.4 | 17.3 | 17.6 | 17.5 | 16.3 |

| 2013 |

17.9 |

17.8 |

18.3 |

17.9 |

15.6 |

|

Immigrant | |||||

| No | 77.2 | 75.7 | 77.2 | 78.9 | 74.7 |

| Yes |

22.9 |

24.3 |

22.8 |

21.2 |

25.4 |

|

Household income | |||||

| 1 (Lowest) | 15.3 | 16.1 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 20.5 |

| 2 | 17.4 | 18.3 | 17.4 | 16.5 | 18.3 |

| 3 | 30.9 | 31.7 | 31.9 | 29.7 | 28.3 |

| 4 | 20.5 | 18.8 | 20.9 | 21.6 | 17.8 |

| 5 (Highest) |

15.9 |

15.1 |

15.4 |

17.6 |

15.1 |

|

Smoking Status | |||||

| Non-smoker | 54.7 | 56.4 | 56.4 | 52.9 | 47.9 |

| Former | 24.1 | 25.4 | 24.1 | 23.9 | 22.7 |

| Current |

21.2 |

18.2 |

19.5 |

23.2 |

29.3 |

|

Alcohol consumption | |||||

| No past-year | 19.2 | 22.9 | 19.2 | 15.7 | 21.9 |

| Occasional | 16.1 | 15.7 | 15.7 | 16.2 | 18.2 |

| Regular | 29.1 | 31.6 | 29.8 | 27.8 | 24.9 |

| Regular & binge |

35.7 |

29.9 |

35.3 |

40.3 |

34.9 |

|

Physical activityb | |||||

| Active | 24.9 | 28.9 | 25.8 | 22.7 | 19.2 |

| Moderate | 26.8 | 25.8 | 29.2 | 24.9 | 20.8 |

| Inactive |

48.3 |

45.3 |

45.0 |

52.5 |

60.0 |

|

BMI | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 43.5 | 41.9 | 42.8 | 45.6 | 44.1 |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 37.5 | 38.3 | 39.0 | 35.2 | 34.0 |

| Mod obese (30–34.9) | 12.0 | 13.0 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 12.4 |

| Very obese (≥35) | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 6.1 |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index; SRH self-rated general health; SRMH self-rated mental health.

Weighted using normalized weights; sampling weights were used to produce population estimates.

Physical activity was defined based on total daily energy expenditure values (=number of times a respondent engaged in an activity over a 12-month period * average duration in hours of the activity * MET value/365 days). MET values corresponded to the low intensity value of each activity.

3.2. Self-rated general versus mental health

Weaker community belonging exhibited a consistent relationship with lower levels of both general and mental health (Table 2). In the fully adjusted model, the odds of reporting the poorest level of general health (fair/poor versus excellent) was 1.45 (95% CI: 1.41, 1.48) times higher for those reporting a somewhat strong sense, 1.91 (95% CI: 1.86, 1.96) times higher for those reporting a somewhat weak sense, and 3.21 (95% CI: 3.11, 3.31) for those reporting a very weak sense of community belonging, compared to those reporting a very strong sense of community belonging. The odds of reporting the poorest versus best level of mental health was 1.32 (95% CI: 1.27, 1.37) times higher for those reporting somewhat strong community belonging, 2.56 (95% CI: 2.46, 2.66) for those reporting a somewhat weak sense, and 4.95 (95% CI: 4.75, 5.16) times higher for those reporting a very weak sense of community belonging, compared to those reporting a very strong sense (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and fully adjusteda odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervalsb for ‘good’ or ‘poor/fair’ versus ‘excellent/very good’ health according to sense of community belonging (N = 703,304).

| SRH |

Unadjusted OR |

Fully adjustedaOR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Fair/Poor | Good | Fair/Poor | |

| Very strong CB | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| SW strong CB | 1.20 (1.18, 1.22) | 1.11 (1.09, 1.14) | 1.34 (1.32, 1.36) | 1.45 (1.41, 1.48) |

| SW weak CB | 1.35 (1.33, 1.38) | 1.27 (1.23 1.30) | 1.59 (1.56, 1.62) | 1.91 (1.86, 1.96) |

|

Very weak CN |

1.58 (1.54, 1.62) |

2.64 (2.66, 2.72) |

1.67 (1.63, 1.71) |

3.21 (3.11, 3.31) |

|

SRMH |

Good |

Fair/Poor |

Good |

Fair/Poor |

| Very strong CB | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| SW strong CB | 1.30 (1.27, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.20, 1.29) | 1.36 (1.34, 1.39) | 1.32 (1.27, 1.37) |

| SW weak CB | 1.74 (1.71, 1.78) | 2.41 (2.33, 2.51) | 1.86 (1.83, 1.90) | 2.56 (2.46, 2.66) |

| Very weak CB | 2.08 (2.03, 2.13) | 5.43 (5.22, 5.66) | 2.05 (2.00, 2.10) | 4.95 (4.75, 5.16) |

Abbreviations: CB community belonging; OR odds ratio; SRH self-rated general health; SRMH self-rated mental health; SW somewhat.

Fully adjusted model includes age, sex, CCHS cycle, immigrant status, household income quintile, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and BMI.

95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

Community belonging exhibited a stronger relationship with self-rated mental health than general health (i.e., the odds ratio from the fully adjusted model for very weak community belonging comparing fair/poor to excellent was 3.21 for self-rated health and 4.95 for self-rated mental health). At all weaker levels of community belonging and poorer levels of health, the effect estimates were larger for mental health (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fully-adjusteda adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervalsb for ‘good’ or ‘poor/fair’ versus ‘excellent/very good’ health according to sense of community belonging, by age stratum (N = 703,304).

| SRH |

18-39 Stratum N = 217,364 |

40-59 Stratum N = 233,995 |

≥60 Stratum N = 251,945 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Fair/Poor | Good | Fair/Poor | Good | Fair/Poor | |

| Very Strong CB | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| SW Strong CB | 1.25 (1.22, 1.29) | 1.30 (1.22, 1.39) | 1.34 (1.30, 1.37) | 1.22 (1.18, 1.27) | 1.43 (1.39, 1.47) | 1.70 (1.64, 1.76) |

| Somewhat weak | 1.52 (1.47, 1.57) | 1.76 (1.65, 1.88) | 1.58 (1.53, 1.62) | 1.65 (1.58, 1.72) | 1.67 (1.62, 1.73) | 2.18 (2.09, 2.28) |

| Very weak CB |

1.66 (1.59, 1.72) |

3.01 (2.81, 3.23) |

1.68 (1.61, 1.74) |

3.18 (3.02, 3.34) |

1.55 (1.47, 1.62) |

2.84 (2.69, 3.00) |

|

SRMH |

Good |

Fair/Poor |

Good |

Fair/Poor |

Good |

Fair/Poor |

| Very Strong CB | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| SW Strong CB | 1.26 (1.22, 1.31) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.34) | 1.43 (1.38, 1.47) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.35) | 1.39 (1.35, 1.43) | 1.44 (1.34, 1.54) |

| Somewhat weak CB | 1.69 (1.63, 1.75) | 2.27 (2.11, 2.44) | 1.96 (1.90, 2.02) | 2.49 (2.35, 2.64) | 1.95 (1.88, 2.02) | 3.05 (2.83, 3.28) |

| Very weak CB | 1.96 (1.88, 2.04) | 4.41 (4.08, 4.76) | 2.16 (2.07, 2.25) | 5.37 (5.04, 5.72) | 1.95 (1.86, 2.05) | 4.55 (4.19, 4.93) |

Abbreviations: CB community belonging; SRH self-rated general health; SRMH self-rated mental health; SW somewhat.

Fully adjusted model includes age, sex, CCHS cycle, immigrant status, household income quintile, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and BMI.

95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

3.3. Age-stratified analysis

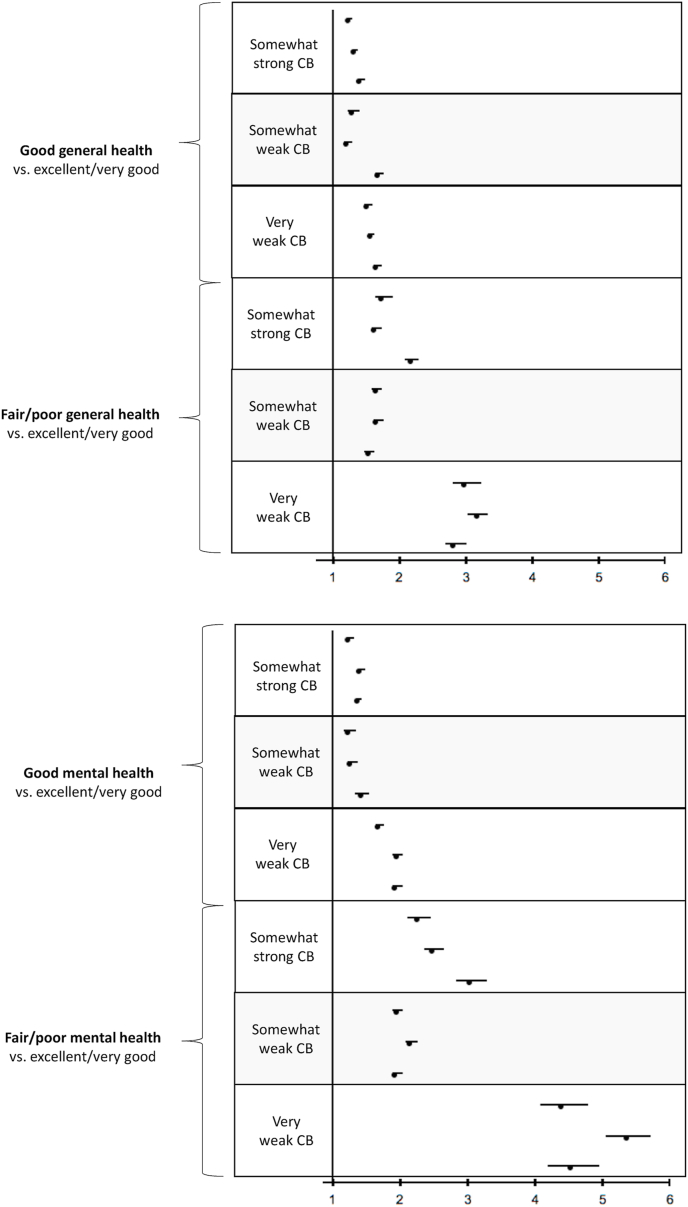

Comparing the fully adjusted age-stratified models, the largest effects estimates at the somewhat strong and somewhat weak levels of community belonging were observed in those over 60 years of age for both general and mental health (Table 3). However, among those reporting the weakest level of community belonging (very weak sense), the largest magnitude of effects were observed in the middle-aged stratum (40–59 years old) for both general and mental health. Middle-aged adults reporting a very weak versus very strong sense of community belonging exhibited 3.18 (95% CI: 3.02, 3.34) times the odds of reporting the poorest level of general health, and 5.37 (95% CI: 5.04, 5.72) times the odds of reporting the poorest level of mental health (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of age-stratified fully adjusted odds ratios for (A) general health models, and (B) mental health models. Plotted odds ratios are for those reporting ‘good’ or ‘poor/fair’ health versus ‘excellent/very good’ health, according to level of community belonging.

Fully adjusted interaction models showed a statistically significant interaction between age stratum and community belonging (p < 0.0001), further confirming that the strength of the association between community belonging and general or mental health is dependent on life stage. The interaction models were statistically significant when examined within each independent survey cycle.

Categorizing the missing income observations as a separate value resulted in no significant differences in effect estimates. Across all models, no significant differences in effect sizes were observed between males and females (Supplementary Table 2).

4. Discussion

Community belonging is increasingly being recognized as an important determinant of health, and hence is an important metric to monitor and understand for population health. This 1-item measure provides a multidimensional insight into individuals’ perception of their place in the community, their social relations within it, and overall neighbourhood satisfaction (Schellenberg et al., 2018). Our study showed that this measure was a strong and independent predictor of both self-rated general and mental health across all life stages. When comparing those reporting a middle-ground sense of belonging (somewhat strong or somewhat weak versus very strong), the magnitude of the association with poorer health was largest among older adults. However, when comparing those reporting the weakest sense of belonging (very weak versus very strong), the magnitude of the association with poorer health was largest among middle-aged adults.

The overall findings presented in this study echo that of previous research, wherein significant and consistent associations between sense of belonging and health have been observed (Almedom and Glandon, 2008, Carpiano and Hystad, 2011, Kim et al., 2014, Kim et al., 2013, Kitchen et al., 2012, Ross, 2002, Shields, 2008). The larger social networks associated with community belonging may facilitate increased diffusion of positive health information and service (Kim & Kawachi, 2017). The increased social connections also offer individuals social and psychological support (Kim & Kawachi, 2017). People with community support may benefit from feelings of mutual respect, a deeper sense of self-esteem, and reduced chronic stress. Notably, social ties may not be enough to promote collective well-being; a sense of community belonging may positively influence health through the ways it translates into an improved collective capacity of community members, such that the community more effectively advocates for resources (Kim & Kawachi, 2017).

Comparing the associations with general health to those with mental health, larger differences between odds ratios corresponding to different levels of community belonging were observed in the mental health models. The associations between social cohesion with mutual respect and self-esteem have been understood to influence psychological domains: a lack of connectedness acting as a chronic stressor is associated with poorer psychological functioning, more severe depression, and increased distress (Rugel et al., 2019, Thoits, 2011). Given that one in three Canadians meets the criteria for a mental or substance use disorder at some point in their lifetime, and that this prevalence is rising, the identification of a potentially modifiable determinant of mental health is becoming increasingly relevant and important for Canada's health system (Pearson et al., 2013).

The age-stratified analysis allowed us to examine at which life stages the association between community belonging and health was most evident. As mentioned, the magnitude of the relationship increased with respect to age at middle-ground senses of community belonging, but at the weakest level, the strongest relationship with health was observed in middle-aged adults. Given that mid-life can be considered both a period of peak functioning and of crisis, the complex interplay of differing social roles with physical and psychological changes may pose a poor sense of belonging at the meso-social level as particularly important to health during this stage.

The strong relationships found throughout all of adulthood is particularly important in light of the fact that compared to older adults, a larger proportion of young and middle-aged adults report weaker community belonging. Paired with the growing burden of mental health disorders in Canada especially prevalent among younger and middle-aged adults, interventions aimed at strengthening community belonging deserve recognition across all life stages, rather than solely in old age. An upstream approach that treats community belonging as a prophylactic to be fostered throughout life may promise more substantial improvements in population health.

This study has a number of strengths. First, a large pooled national sample was used. Not only did this improve the generalizability of the findings, but it also permitted stratified analyses by age, and sensitivity analyses further stratified by sex. Second, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that this association has been independently examined at different stages of life among Canadians.

This study also has several limitations. The main limitation of this study lies in the fact that causality cannot be established due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. The relationship between measures of social capital and health outcomes is also known to be bidirectional: physical health can limit an individual's capacity to engage with their community, and mental health could limit interest in engagement, materialize in a way that obstructs community engagement, or influence perceptions of inclusion.

The cross-sectional nature of this study also limits generalizations regarding life cycle experiences. Despite being able to pool a decade of data, the young versus old populations in this sample come from distinctively different birth cohorts. It is therefore possible that the life stage differences reflect cohort effects, rather than age effects. We control for wave of data collection in our study as well as examine survey-specific effects in order to minimize this influence. An age-period-cohort analysis may be warranted in future studies to further explore time-varying factors.

Further, this study relied on self-reported data which is subject to recall and reporting bias, the degree of which is unknown. There may exist a third unmeasured factor that makes people feel both less connected and more ill (i.e. individuals with a more positive psychological disposition may be more likely to interpret their role in the community as meaningful as well as a more positive perception of one's own health). But this cannot be a large part of the story, since these CCHS data have also shown a strong positive correlation between community belonging and life satisfaction using neighbourhood data, where individual-level psychological factors are averaged out (Helliwell et al., 2018). If these individual-level confounders were importantly the case, then there would no longer be an association once individual-level personality factors were averaged out in the community-level data.

In addition, questions regarding the focal exposure may be interpreted differently. The 1-item community belonging question did not define what is meant by local community, and as such, interpretation of this question may vary (i.e. according to urban or rural geography, which was not an available measure). As previously mentioned however, this 4-point Likert scale question has been shown to closely capture specific aspects of neighbourhood social capital (Carpiano & Hystad, 2011; Schellenberg et al., 2018). However, differences in interpretation between urban and rural communities have been shown (Carpiano & Hystad, 2011), and we were unable to account for this measure.

Lastly, our findings are not directly applicable to sub-populations not in the sampling frame for the CCHS. Unrepresented populations include Indigenous populations living on reserve, individuals in the military, and those living in institutions, who are known to be at increased risk of mental health problems (Greene-Shortridge et al., 2007, Hawthorne et al., 2012, Nelson and Wilson, 2017).

5. Conclusion

This study provides evidence that a respondent's sense of community belonging is linked to their general health status, and particularly strongly linked to their self-perceived mental health. These associations are observed throughout all of adulthood, but the largest effects are observed among middle-aged adults reporting the weakest sense of belonging.

These findings provide a strong incentive for further research exploring how community belonging affects health outcomes throughout the life course using alternate data sources and study designs. In particular, a prospective study design that accounts for baseline health status and community belonging would illuminate the effect of community belonging on subsequent health trajectories, as well as permitting closer investigation of the mechanisms driving this association.

Author statements

Camilla A Michalski: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Lori M Diemert: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing. John F Helliwell: Writing - reviewing and editing. Vivek Goel: Writing - reviewing and editing. Laura C. Rosella: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Ethical statement

Informed consent was obtained by Statistics Canada for all survey participants. Ethics approval for the use of the data is covered by the publicly available data clause, which does not require review or approval by a research ethics board.

Data statement

All public use microdata files of the Canadian Community Health Survey are available at https://search2.odesi.ca/#/

Financial disclosure statement

LR is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Population Health Analytics. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding source.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100676.

Contributor Information

Camilla A. Michalski, Email: c.michalski@mail.utoronto.ca.

Lori M. Diemert, Email: lori.diemert@utoronto.ca.

John F. Helliwell, Email: johnfhelliwell@gmail.com.

Vivek Goel, Email: vivek.goel@utoronto.ca.

Laura C. Rosella, Email: laura.rosella@utoronto.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Almedom A.M., Glandon D. Social capital and mental health: An updated interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. In: Kawachi I., Subramanian S.V., Kim D., editors. Social capital and health. Springer; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baćak V., Ólafsdóttir S. Gender and validity of self-rated health in nineteen European countries. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2017;45(6):647–653. doi: 10.1177/1403494817717405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Leary M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beland Y. Canadian community health survey—methodological overview. Health Reports. 2002;13(3):9–14. 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L.F. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995;57(3):245–254. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L.F., Syme S.L. Reprint: Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of alameda county residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2017;185(11):1070–1088. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerdike L., Booth A., Wilson P.M., Farley K., Wright K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Vol. 1. Random House; New York: 1969. (Attachment and loss v. 3). [Google Scholar]

- Buijs V., Jeronimus B., Lodder G., Steverink N., Jonge P. Social needs and happiness: A life course perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/7kz9t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano R.M., Hystad P.W. “Sense of community belonging” in health surveys: What social capital is it measuring? Health & Place. 2011;17(2):606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K.J., Li F., Michael Y., Cleveland M. Neighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity; Champaign. 2004;12(1):45–63. doi: 10.1123/japa.12.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene-Shortridge T.M., Britt T.W., Castro C.A. The stigma of mental health problems in the military. Military Medicine. 2007;172(2):157–161. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.172.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell F.E. Springer; 2001. Regression modeling strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne W.B., Folsom D.P., Sommerfeld D.H., Lanouette N.M., Lewis M., Aarons G.A., Conklin R.M., Solorzano E., Lindamer L.A., Jeste D.V. Incarceration among adults who are in the public health system: Rates, risk factors, and short-term outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(1):26–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell J.F., Huang H., Norton M.B., Wang S. Happiness at different ages: The social context matters. NBER Working Paper Series: Economics of Aging, Health Care, Labour Studies, Public Economics. 2018;1–36 [Google Scholar]

- House J.S., Landis K.R., Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hystad P., Carpiano R.M. Sense of community-belonging and health-behaviour change in Canada. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2012;66(3):277–283. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.103556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E.L., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(1):21–37. doi: 10.2307/2955359. JSTOR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S., Yorifuji T., Takao S., Doi H., Kawachi I. Social cohesion and mortality: A survival analysis of older adults in Japan. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(12):e60–e66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iredell H., Grenade L., Nedwetzky A., Collins J., Howat P. Reducing social isolation amongst older people-implications for health professionals. Geriaction. 2004;22(1):13. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Subramanian S.V., Kim D. Social capital and health. 1st. Springer; New York: 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.S., Hawes A.M., Smith J. Perceived neighbourhood social cohesion and myocardial infarction. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2014;68(11):1020–1026. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.S., Kawachi I. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and preventive healthcare use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017;53(2):e35–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.S., Park N., Peterson C. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and stroke. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;97:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen P., Williams A., Chowhan J. Sense of community belonging and health in Canada: A regional analysis. Social Indicators Research. 2012;107(1):103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M. Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner K.A., Kawachi I., Brennan R.T., Buka S.L. Social capital and neighborhood mortality rates in Chicago. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(8):1797–1805. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A. Harper and Row; New York: 1954. The five-tier hierarchy of needs. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan D.W., Chavis D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(1):6–23. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S.E., Wilson K. The mental health of indigenous peoples in Canada: A critical review of research. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;176(Complete):93–112. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C., Janz, T., & Ali, J. (n.d.). Mental and substance use disorders in Canada. Vol. 10..

- Pescheny J.V., Randhawa G., Pappas Y. The impact of social prescribing services on service users: A systematic review of the evidence. The European Journal of Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard L., Gauvin L., Raine K. Ecological models revisited: Their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32(1):307–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross N. Community belonging and health. Health Reports. 2002;13(13):33–39. http://search.proquest.com/docview/207471674?accountid=14771&pq-origsite=summon PMID: 12743959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugel E.J., Carpiano R.M., Henderson S.B., Brauer M. Exposure to natural space, sense of community belonging, and adverse mental health outcomes across an urban region. Environmental Research. 2019;171:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason S.B. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1974. The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg G., Lu C., Schimmele C., Hou F. The correlates of self-assessed community belonging in Canada: Social capital, neighbourhood characteristics, and rootedness. Social Indicators Research. 2018;140(2):597–618. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1783-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J., Bacak V. The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields M. Community belonging and self-perceived health. Health Reports. 2008;19(2):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada Canadian community health survey (CCHS) 2007. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=4995

- Tartaglia S. A preliminary study for a new model of sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34(1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(2):145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. JSTOR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Wannell B. Combining cycles of the Canadian community health survey. Health Reports. 2009;20(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa B.F.L., Møller V., Sousa-Poza A. How does subjective well-being evolve with age? A literature review. Journal of Population Ageing. 2013;6(3):227–246. doi: 10.1007/s12062-013-9085-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.