Abstract

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) stands as the second most common malignant tumor in the liver with poor patient prognosis. Increasing evidences have shown that inflammation plays a significant role in tumor progression, angiogenesis, and metastasis. However, the prognosis significance of inflammatory biomarkers on recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in ICC patients is poorly recognized.

Methods

ICC patients who underwent curative hepatectomy and diagnosed pathologically were retrospectively analyzed. Inflammatory biomarkers, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), were investigated.

Results

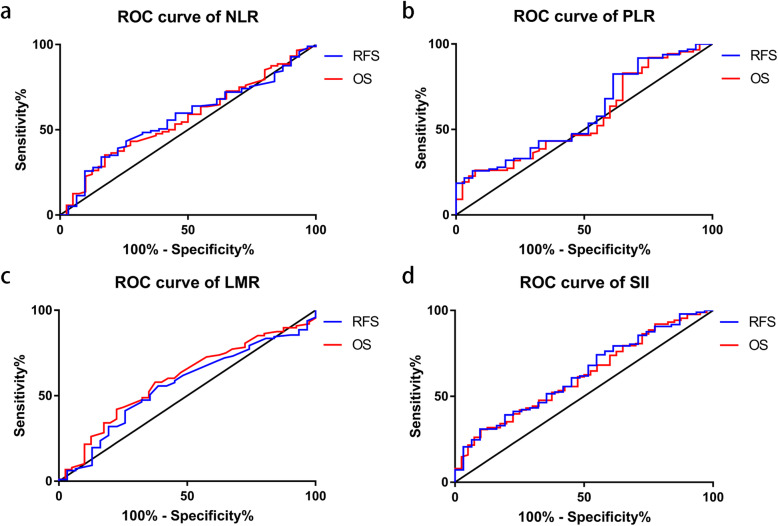

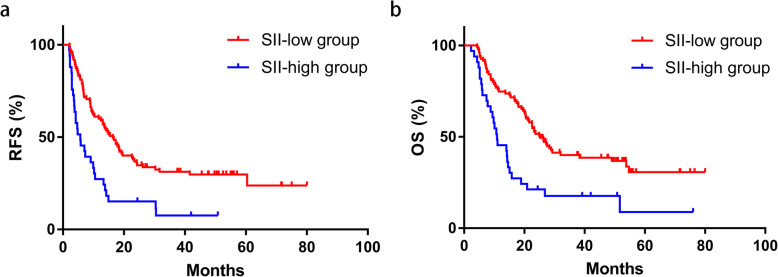

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showed no significance in NLR, PLR, and LMR in RFS and OS, while significant results were shown on SII in both RFS (P = 0.035) and OS (P = 0.034) with areas under ROC curve as 0.63 (95%CI 0.52–0.74) and 0.62 (95%CI 0.51–0.72), respectively. Kaplan-Meier curves revealed a statistically significant better survival data in SII-low groups on both RFS (P < 0.001) and OS (P < 0.001). The univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that higher level of SII was independently associated with both poorer RFS time and OS time. However, no significant result was shown on NLR, PLR, or LMR.

Conclusion

SII is an effective prognostic factor for predicting the prognosis of ICC patient undergone curative hepatectomy, while NLR, PLR, and LMR are not associated with clinical outcomes of these patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12957-020-02053-w.

Keywords: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Inflammatory biomarker, Systemic immune-inflammation index

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) stands as the second common malignant hepatic neoplasms; however, the incidence of ICC grows worldwide during past decades [1, 2]. Up to now, the best choice of curative treatments is surgical resection, while the treatments for unresectable ICC are very limited [3]. ICC usually grows aggressively without symptom in early stage, resulting in a small proportion of ICC patients who can receive surgery. Furthermore, the prognosis of resectable ICC patient still remains poor and half of them will suffer from recurrence after surgery [4]. Many researches were performed and found various significant risk factors in ICC, helping the management of ICC patients [5, 6].

Meantime, increasing evidences have shown that inflammation and inflammatory biomarkers are significant factors in tumor microenvironment, thus promoting proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis by various inflammatory cells and cytokines [7]. In recent years, multiple inflammatory biomarkers were investigated for predicting the prognosis of patients with various cancer, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII). Significant results were reported in various types of cancer such as neck soft tissue sarcoma, lung cancer, renal cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [8–10].

However, the significance of these inflammatory biomarkers on prognosis of ICC patients underwent curative resection has not been fully understood. Therefore, the present study was performed for investigating the significance of various inflammatory biomarkers, including NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII on patient prognosis in ICC after curative surgery.

Methods

Study cohort

ICC patients underwent curative hepatectomy between January 2013 and December 2017 in Xiangya hospital, Central South University, were retrospectively analyzed. Exclusion criteria were as followed: (1) pathology did not support the diagnosis of ICC, (2) recurrence of ICC, (3) received an anti-tumor therapy before resection, (4) suffering from infectious diseases before resection, (5) suffering from autoimmune diseases or immunodeficiency diseases, (6) patients who died of postoperative complications or reasons other than ICC, (7) R1 or R2 resection, (8) hilar type of ICC, and (9) incomplete clinical data. The ethics committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University approved this study.

Definitions and follow-up

The TNM stage of ICC was determined by the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual. NLR was calculated as neutrophil count (109/L)/lymphocyte count (109/L). PLR was calculated as platelet (109/L)/lymphocyte count (109/L), while LMR as lymphocyte count (109/L)/monocyte count (109/L). And the SII was defined as platelet (109/L) × neutrophil/ lymphocyte counts. All patients were received porta hepatis lymphadenectomy during the surgery to determine status of lymph node. Vascular invasion was defined as major vascular invasion.

Patients were followed up every 3 month after surgery. Blood tests including the liver function and tumor biomarkers, and imaging examination was also performed during follow-up. Our primary end points were recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS). RFS was calculated from the first day after hepatectomy to the recurrence of ICC- or ICC-related death, while OS was calculated from the first day after hepatectomy to the ICC-related death.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Company, Chicago, IL) for Windows and Prism software (GraphPad Prism Software, La Jolla, CA) were used to analyze data and realize visualization. Independent-sample t test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the quantitative data expressed as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). And chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used as appropriate to analyze the categorical data expressed as frequency (percentage). The cutoff values were calculated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to illustrate RFS and OS, while the log-rank test was used to detect the differences between groups. Meanwhile, the Cox’s proportional hazard regression was used to identify associated factors of RFS and OS. P < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

128 ICC patients, including 70 males and 58 females, were finally included. The basic patient and tumor characteristics were shown in Table 1. 28.1% of patients presented multiple tumors and 34.4% patients suffered from lymph node metastasis. Proportions of patients with AJCC tumor stages I, II, and III were 26.6%, 14.8%, and 58.6%, respectively. 39.8% patients presented vascular invasion, while 13.3% of patients had undermined the liver function. The averages of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and albumin were 49.58 ± 57.93 U/L, 42.51 ± 31.27 U/L, and 40.33 ± 4.45 g/L. The mean values of CEA, CA19-9, and CA242 were 6.96 ± 15.93 ng/ml, 272.69 ± 318.33 U/ml, and 75.56 ± 104.66 U/ml, respectively. The mean values of neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, and platelet counts were (4.70 ± 1.91)109/L, (1.59 ± 0.49)109/L, (0.66 ± 0.87)109/L, and (232.39 ± 97.68)109/L, respectively. Furthermore, the mean values of calculated NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII were 3.30 ± 2.16, 156.79 ± 77.66, 3.20 ± 2.46, and 793.67 ± 695.14, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic variables of included ICC patients

| Variables | Values (n = 128) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.19 ± 9.63 |

| Male | 70 (54.7) |

| Tumor size (cm) | 5.83 ± 2.85 |

| Number of tumors | |

| Single | 92 (71.9) |

| Multiple | 36 (28.1) |

| AJCC tumor stage | |

| I | 34 (26.6) |

| II | 19 (14.8) |

| III | 75 (58.6) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| No | 84 (65.6) |

| Yes | 44 (34.4) |

| Vascular invasion | |

| No | 77 (60.2) |

| Yes | 51 (39.8) |

| Tumor differentiation | |

| Well to moderate | 44 (34.4) |

| Poor to undifferentiated | 84 (65.6) |

| ALT (U/L) | 49.58 ± 57.93 |

| AST (U/L) | 42.51 ± 31.27 |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 6.96 ± 15.93 |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 272.69 ± 318.33 |

| CA242 (U/ml) | 75.56 ± 104.66 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 4.70 ± 1.91 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 1.59 ± 0.49 |

| Monocyte (109/L) | 0.66 ± 0.87 |

| PLT (109/L) | 232.39 ± 97.68 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.33 ± 4.45 |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| A | 111 (86.7) |

| B | 17 (13.3) |

| NLR | 3.30 ± 2.16 |

| PLR | 156.79 ± 77.66 |

| LMR | 3.20 ± 2.46 |

| SII | 793.67 ± 695.14 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or n (%)

ICC intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, PLT blood platelet, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, LMR lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, SII systemic immune-inflammation index

Cutoff values of inflammatory biomarkers

ROC curves were performed to determine appropriate cutoff values of NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII, and the results were shown in Fig. 1. However, according to the ROC curves of RFS and OS, the results showed no significance in NLR, PLR, or LMR, while significant results were shown on SII in both RFS (P = 0.035) and OS (P = 0.034) with areas under ROC curve as 0.63 (95%CI 0.52–0.74) and 0.62 (95%CI 0.51–0.72), respectively. Thus, the subsequent analyses were focused on SII with an ideal cutoff value as 1027 according to ROC curves and Youden index.

Fig. 1.

ROC curves of NLR (a), PLR (b), LMR (c), and SII (d) on RFS and OS. a The AUC for RFS and OS were 0.569 (95%CI = 0.459–0.679, P = 0.250) and 0.565 (95%CI = 0.461–0.669, P = 0.239). b The AUC for RFS and OS were 0.592 (95%CI = 0.477–0.707, P = 0.125) and 0.568 (95%CI = 0.460–0.675, P = 0.222). c The AUC for RFS and OS were 0.561 (95%CI = 0.447–0.674, P = 0.310) and 0.597 (95%CI = 0.493–0.701, P = 0.079). d The AUC for RFS and OS were 0.626 (95%CI = 0.517–0.736, P = 0.035) and 0.617 (95%CI = 0.515–0.719, P = 0.034). ROC receiver operating characteristic, AUC area under curve, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, LMR lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, SII systemic immune-inflammation index, RFS recurrence free survival, OS overall survival

Survival analyses based on SII

Survival analyses were performed between SII-low group and SII-high group according to cutoff value of SII, and the results were shown in Fig. 2. The median RFS times in the SII-low group and SII-high group were 16.4 months and 5.7 months, and the median OS times were 25.2 months and 10.9 months, respectively. Statistically significant differences between the two groups were revealed by Kaplan-Meier curves on both RFS (P < 0.001) and OS (P < 0.001), indicating a potential prognostic value of SII. Only one patient suffered from recurrence after 5 years (60.4 months). Another surgery was performed since the recurrence was intrahepatic, and no new recurrence was found in the last follow-up.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons between SII-low group and SII-high group using Kaplan-Miere curves on RFS (a) and OS (b). Better survival data were showed in SII-low group on both RFS (P < 0.001) and OS (P < 0.001). SII systemic immune-inflammation index, RFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

Univariate and multivariate analyses

For further investigating risk factors affecting RFS and OS of ICC patients, the univariate and multivariate analyses were subsequently performed among available factors, with the results shown in Table 2. The analyses revealed that multiple tumors, higher AJCC tumor stage, poorer tumor differentiation, higher level of CEA and CA19-9, and higher level of SII were independently associated with both poorer RFS time and OS time. However, no significant result was shown on NLR, PLR, or LMR.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors with RFS and OS in ICC patients

| Variables | RFS | OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Univariate analyses | ||||

| Age (years) (> 60 vs. ≤ 60) | 0.670 (0.440, 1.018) | 0.061 | 0.794 (0.514, 1.226) | 0.298 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.899 (0.603, 1.341) | 0.603 | 0.763 (0.502, 1.161) | 0.207 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.126 (1.053, 1.204) | 0.001 | 1.107 (1.035, 1.186) | 0.003 |

| Number of tumors (multiple vs. single) | 1.797 (1.168, 2.763) | 0.008 | 1.936 (1.246, 3.008) | 0.003 |

| AJCC tumor stage (III vs. I and II) | 1.726 (1.135, 2.624) | 0.011 | 1.960 (1.250, 3.074) | 0.003 |

| Lymph node metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.881 (1.243, 2.848) | 0.003 | 2.197 (1.430, 3.376) | < 0.001 |

| Vascular invasion (yes vs. no) | 1.558 (1.041, 2.332) | 0.031 | 1.478 (0.972, 2.248) | 0.068 |

| Tumor differentiation (poor to undifferentiated vs. well to moderate) | 2.173 (1.389, 3.401) | 0.001 | 1.971 (1.222, 3.179) | 0.005 |

| ALT (U/L) | 0.998 (0.994, 1.001) | 0.195 | 0.999 (0.995, 1.003) | 0.570 |

| AST (U/L) | 0.996 (0.990, 1.003) | 0.273 | 0.999 (0.993, 1.005) | 0.815 |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 1.020 (1.008, 1.032) | 0.001 | 1.027 (1.015, 1.040) | < 0.001 |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 1.002 (1.001, 1.002) | < 0.001 | 1.002 (1.001, 1.003) | < 0.001 |

| CA242 (U/ml) | 1.005 (1.003, 1.007) | < 0.001 | 1.005 (1.003, 1.007) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 1.018 (0.947, 1.096) | 0.625 | 1.033 (0.960, 1.112) | 0.387 |

| PLR | 1.003 (1.000, 1.005) | 0.021 | 1.003 (1.001, 1.006) | 0.011 |

| LMR | 1.039 (0.943, 1.146) | 0.435 | 1.019 (0.903, 1.151) | 0.757 |

| SII (SII-low group vs. SII-high group) | 2.352 (1.519, 3.641) | < 0.001 | 2.340 (1.484, 3.689) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.979 (0.936, 1.023) | 0.347 | 0.969 (0.924, 1.017) | 0.203 |

| Child-Pugh score (B vs. A) | 0.996 (0.564, 1.757) | 0.988 | 1.286 (0.725, 2.279) | 0.389 |

| Multivariate analyses | ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.030 (0.953, 1.113) | 0.456 | 0.976 (0.899, 1.060) | 0.563 |

| Number of tumors (multiple vs. single) | 1.849 (1.168, 2.928) | 0.009 | 2.017 (1.274, 3.192) | 0.003 |

| AJCC tumor stage (III vs. I and II) | 1.599 (1.018, 2.511) | 0.042 | 1.982 (1.207, 3.255) | 0.007 |

| Tumor differentiation (poor to undifferentiated vs. well to moderate) | 2.355 (1.444, 3.840) | 0.001 | 1.865 (1.093, 3.182) | 0.022 |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 1.022 (1.008, 1.037) | 0.003 | 1.033 (1.017, 1.049) | < 0.001 |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 1.001 (1.000, 1.002) | 0.034 | 1.002 (1.001, 1.003) | 0.001 |

| CA242 (U/ml) | 1.001 (0.998, 1.004) | 0.552 | 0.999 (0.996, 1.003) | 0.712 |

| PLR | 0.998 (0.995, 1.002) | 0.327 | 0.998 (0.995, 1.002) | 0.316 |

| SII (SII-high group vs. SII-low group) | 2.368 (1.279, 4.386) | 0.006 | 2.454 (1.278, 4.712) | 0.007 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, ICC intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, RFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, LMR lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, SII systemic immune-inflammation index

Discussion

It is widely recognized that the systemic inflammation involves in pathogenesis and progression of cancer by various mechanisms including cell proliferation, tissue infiltration, and angiogenesis [11, 12]. Multiple inflammatory biomarkers could effectively present the extent of inflammatory and immune response with high availability, therefore, were recommend as factors for predicting the prognosis of cancer patients. In the present study, we investigated the prognostic significance of inflammatory biomarkers in curative resected ICC patients. Our results suggested that SII could effectively predict the prognosis of ICC patients after curative hepatectomy, while NLR, PLR, and LMR were not related with outcomes of these patients. This finding could help classifying ICC patients with a highly feasible indicator. Additional treatments, such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, should be considered to improve the prognosis among patients with poorer prognosis predicted by SII. Furthermore, SII could serve as an indicator for planning therapies, especially immunotherapy, among ICC patients in the future.

Extensive non-specific inflammatory responses were usually led by allogeneic phenotype of cancer cell, followed by increasing of neutrophils and platelets, and deceasing of lymphocytes [13]. Neutrophils could secrete TNF-alpha, VEGF, and interleukin, thus to promote tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis [14]. Meanwhile, TGF-beta, VEGF, and platelet-derived factors could be secreted by platelets, accelerating differentiation and proliferation of cancer cells, and playing a significant role in adhesion and angiogenesis of tumor tissues. On the other hand, lymphocytes could mediate cytotoxicity and release cytokines, thus presenting antitumor effects as inhibiting growth, proliferation, and metastasis of tumor cell [15]. The decrease of lymphoctyes could lead to lower immune function, progression of tumor, and eventually poor prognosis of patients with tumor. Furthermore, studies showed that activity of lymphocytes could be suppressed by neutrophils [16]. In addition, monocytes in tumor tissues can differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages, which place promoting effects on tumor growth, tumor cell infiltration, and angiogenesis [17]. Thus, the NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII would theoretically be valuable biomarkers for predicting prognosis of cancer, considering all of them could be easily obtained from routine preoperative examinations.

In ICC, this study showed SII as the only independent risk factor on RFS and OS of patients. Two previous studies have also investigated the role of SII in OS among ICC patients [18, 19]. Their results both indicated higher SII was associated with poorer patient survival in ICC, which was consistent with our results. However, one of them also showed that NLR had a better significance as a biomarker on ICC patient. The inconsistent results on NLR might be caused by different cohorts because they did not focus on the patients underwent a curative therapy but the whole ICC cohort.

The present study did contain a few limitations. Firstly, this was a retrospective study with not large sample size. Further prospective, multicenter clinical studies with large cohorts should be performed to validate the values of these inflammatory biomarkers in ICC. Secondly, these inflammatory biomarkers were assessed by single measurements during admission, which might cause uncontrolled bias. Thirdly, some factors which could make an impact on these inflammatory biomarkers, such as smoking and alcoholic, were not fully under control.

Conclusion

In summary, our study shows SII can effectively predict the prognosis of ICC patient undergone curative hepatectomy, while NLR, PLR, and LMR are not related with clinical outcomes of these patients.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ICC

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- PLR

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- LMR

Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

- SII

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- RFS

Recurrence-free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- SD

Standard deviation

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

Authors’ contributions

All authors made substantive intellectual contributions to this study to qualify as authors. YH conceived of the design of the study. ZYZ modified the design of the study. ZYZ, YFZ, and KH performed the study, collected the data, and contributed to the design of the study. ZYZ and YFZ analyzed the data. ZYZ drafted the Result, Discussion, and Conclusion sections. YFZ and drafted the Methods sections. ZYZ, KH, and YH edited the manuscript. All authors have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No.202009504). Patient consent was not required to review their medical records by the ethics committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University because of its retrospective design, and exemption from informed consent did not adversely affect the health and rights of subjects. This study kept confidentiality of patient data and strictly complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zeyu Zhang, Email: zeyu_zhang1994@foxmail.com.

Yufan Zhou, Email: 12345ray@sohu.com.

Kuan Hu, Email: kuan.hu@csu.edu.cn.

Yun Huang, Email: huangyun-1002@163.com.

References

- 1.Chang K, Chang J, Yen Y. Increasing incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and its relationship to chronic viral hepatitis. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2009;7(4):423–427. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amini N, Ejaz A, Spolverato G, Kim Y, Herman JM, Pawlik TM. Temporal trends in liver-directed therapy of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population-based analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(2):163–170. doi: 10.1002/jso.23605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyder O, Marques H, Pulitano C, et al. A nomogram to predict long-term survival after resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an Eastern and Western experience. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(5):432–438. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Beal EW, Bagante F, et al. Early versus late recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after resection with curative intent. Br J Surg. 2018;105(7):848–856. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Zhou Y, Hu K, Wang D, Wang Z, Huang Y. Perineural invasion as a prognostic factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection and a potential indication for postoperative chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):270. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06781-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oneda E, Abu Hilal M, Zaniboni A. Biliary tract cancer: current medical treatment strategies. Cancers. 2020;12(5):1237. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi E, Kim H, Han I. Elevated preoperative systemic inflammatory markers predict poor outcome in localized soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(3):778–785. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3418-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russo A, Russano M, Franchina T, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and outcomes with nivolumab in pretreated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): a large retrospective multicenter study. Adv Ther. 2020;37(3):1145–1155. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D, Bai N, Hu X, et al. Preoperative inflammatory markers of NLR and PLR as indicators of poor prognosis in resectable HCC. Peerj. 2019;7:e7132. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanford DE, Belt BA, Panni RZ, et al. Inflammatory monocyte mobilization decreases patient survival in pancreatic cancer: a role for targeting the CCL2/CCR2 axis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(13):3404–3415. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(11):759–771. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia W, Liu Z, Shen D, Lin Q, Su J, Mao W. Prognostic performance of pre-treatment NLR and PLR in patients suffering from osteosarcoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:127. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0889-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabłońska E, Kiluk M, Markiewicz W, Piotrowski L, Grabowska Z, Jabłoński J. TNF-alpha, IL-6 and their soluble receptor serum levels and secretion by neutrophils in cancer patients. Arch Immunol Ther Ex. 2001;49(1):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantovani A. Cancer: inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457(7225):36–37. doi: 10.1038/457036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szebeni GJ, Vizler C, Kitajka K, Puskas LG. Inflammation and cancer: extra- and intracellular determinants of tumor-associated macrophages as tumor promoters. Mediat Inflamm. 2017;2017:9294018. doi: 10.1155/2017/9294018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sellers CM, Uhlig J, Ludwig JM, Stein SM, Kim HS. Inflammatory markers in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: effects of advanced liver disease. Cancer Med-Us. 2019;8(13):5916–5929. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsilimigras DI, Moris D, Mehta R, et al. The systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis. HPB. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.