Abstract

Although men’s health promotion efforts have attracted programmatic and evaluative research, conspicuously absent are gendered insights to men’s health literacy. The current scoping review article shares the findings drawn from 12 published articles addressing men’s health literacy in a range of health and illness contexts. Evident was consensus that approaches tailored to men’s everyday language and delivered in familiar community-based spaces were central to advancing men’s health literacy, and, by extension, the effectiveness of men’s health promotion programs. However, most men’s health literacy studies focussed on medical knowledge of disease contexts including prostate and colon cancers, while diversity was evident regards conceptual frameworks and/or methods and measures for evaluating men’s health literacy. Despite evidence that low levels of health literacy fuel stigma and men’s reticence for health help-seeking, and that tailoring programs to health literacy levels is requisite to effective men’s health promotion efforts, the field of men’s health literacy remains underdeveloped. Based on the scoping review findings, recommendations for future research include integrating men’s health literacy research as a needs analysis to more effectively design and evaluate targeted men’s health promotion programs.

Keywords: health literacy, gender, masculinity, men

INTRODUCTION

Longstanding patterns indicate that many males are challenged to effectively manage their health and/or illness (Courtenay, 2000; O’Brien et al., 2005). There is consensus that low health literacy levels fuel men’s reticence for health help-seeking, and that this problem can be remedied, at least in part, by understanding as well as advancing men’s health literacy with targeted health promotion approaches and programs (Oliffe et al., 2016). Integrating health literacy into health promotion efforts aimed at men is important, but empirical insights to the specificities of men’s health literacy are conspicuously absent, as is the aforementioned health literacy-health promotion supposition. An introduction to men’s health literacy is offered as context for the current scoping review findings. Recommendations for future men’s health literacy research are provided to advance targeted men’s health promotion programs.

Men’s health literacy

Almost 20 years ago, men’s health researchers began integrating Connell’s (Connell, 1995) social constructionist gender framework to explain connections between masculinities and men’s health behaviors (Courtenay, 2000). Much of the early empirical work spoke to men’s avoidance of health promotion and professional health care services as the by-product of men aligning to masculine ideals of self-reliance, stoicism and competitiveness (Lee and Owens, 2002; O’Brien et al., 2005). Around the same time, Nutbeam’s (Nutbeam, 2000) work in health literacy, defined as comprising health-related knowledge, attitudes, motivations, behavioral intensions, personal skills and self-efficacy, emerged as requisite considerations to designing effective health promotion programs. While the men’s health and health literacy fields both strongly connected to health promotion in the years that followed (Nutbeam, 2008; Oliffe et al., 2012), somewhat ironically, explicit connections between men’s health literacy and health promotion failed to materialize (Robertson et al., 2008; Peerson and Saunders, 2011).

Research that did delineate male health literacy tended to combine numerous social determinants of health in focussing on clinical risk, wherein screening for poor health literacy was used to predict potential risk factors that needed to be managed in providing clinical care (Nutbeam, 2008). For example, adapting a subsection of health-related items from the 2003 International Adult Literacy and Skills Survey (Canadian Council on Learning, 2008), Canadian researchers identified seniors (age 66 years and older), immigrant groups, and unemployed persons as groups with the lowest health literacy. The report further indicated that being male was a moderate factor for low health literacy (Canadian Council on Learning, 2008). In the USA, reports measuring health literacy, based on respondent’s ability to navigate the health care system and understand instructions on medication labels and age-specific screening guidelines, indicated that those with low health literacy were more likely to be male, poor, Hispanic, black, 65 years and older and self-assess their health as fair or poor (White et al., 2008). Similarly, in the UK, being male, older, and of low socioeconomic status (SES) and low education levels were associated with low health literacy scores (von Wagner et al., 2007). In these examples, despite consistently reporting linkages between being male and low health literacy levels, the researchers did not fully discuss sex differences or offer gender-sensitized recommendations for addressing the disparity or the male health inequities.

These trends continued within the rapidly growing base of health literacy knowledge boasting over 1000 published articles (Canadian Council on Learning, 2007) to the extent that sex and/or gender were never fully conceptualized as analytic categories within the field. In parallel, men’s health promotion research offered an array of interventions, but the role of health literacy as a program design consideration or outcome measure were rarely integrated or discussed (Oliffe et al., 2010). As a result, there is a lack of empirical evidence linking health literacy to men’s health promotion programs or practices. Instead, health literacy experts have focussed on education materials, usually booklets, in traditional didactic delivery modes to educate-specific sub-populations with medical information as a means to addressing low health literacy among males (Rootman and Ronson, 2005). These approaches trade on assumptions that once men are armed with information, improved health literacy will translate into health promoting behaviors; however, the processes by which these transitions might occur are poorly understood (Peerson and Saunders, 2011). Contrasting these approaches, Nutbeam’s (Nutbeam, 2008) conceptualization of health literacy as a personal asset linked to public health and health promotion efforts for enabling individuals to manage their health and the range of personal, social and environmental health determinants, has offered important avenues for men’s health promotion research. Aligning to contemporary strength-based approaches to men’s health promotion (Robinson and Robertson, 2010) health literacy, as a personal asset, has the potential to move beyond functional health literacy levels (reflected in the attainment of medical knowledge) toward critical health literacy skills to leverage social and political action as well as individual action (Nutbeam, 2015).

The purpose of the current scoping review is to provide an overview of empirical studies that explicitly take up men’s health literacy, and identify the current approaches and gaps in the field as a means to making recommendations for future men’s health literacy research to advance targeted men’s health promotion programs.

MATERIALS

We employed a scoping review methodology to assess the extent of the literature in men’s health literacy as a means to providing a snapshot of this nascent field and making recommendations (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005) including guidance for how health literacy might be used to advance and/or evaluate men’s health promotion programs (Levac et al., 2010; Rumrill et al., 2010; Armstrong et al., 2011). Contrasting the focus of systematic reviews on study evaluations and evidence strength in specific fields, scoping reviews offer interpretive analyses of published research findings in emergent and oftentimes neglected topic areas (Levac et al., 2010). Following Arksey and O'Malley's (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005) framework for scoping reviews, the current review was guided by five incremental stages: (i) identify the research question, (ii) search and retrieve studies, (iii) select studies, (iv) extract and table the study data and (v) collate and summarize the results. These steps were followed to inductively derive broad categories, mapping the most common approaches and contexts for investigating men’s health literacy.

Search strategy

Published articles addressing men’s health literacy were searched in three databases CINAHL, Web of Science and PsycINFO using the keywords (in title, abstract or indexing) health literacy and gender, masculinity or men’s health (Levac et al., 2010; Rumrill et al., 2010). Search limiters included English language studies and reviews published from 2006 to 2017 inclusive. Inclusion criteria comprised empirical and review articles published in English between 2006 and 2017 inclusive that had an explicit focus on men’s health literacy and connected health literacy with gender, culture or male learning/knowledge preferences. The current scoping was also purposefully inclusive of diverse disease contexts, research designs and descriptive, intervention and evaluation studies that explicitly focussed on men’s health literacy. As such, articles without the aforementioned foci including mixed sex patient samples and studies addressing the generic measurement of health literacy, the evaluation or validity of a health literacy instrument, the investigation of health literacy scales with other measures or medical decision-making in conjunction with health literacy were excluded. Many of the excluded articles aggregated health literacy findings for mixed sex samples including older adults, ethnic minorities and adults in rural locales, and/or reported on the use and validity of various health literacy measures for specific disease categories. Articles that focussed solely on health promotion efforts for men were also excluded if they lacked an explicit connection to health literacy.

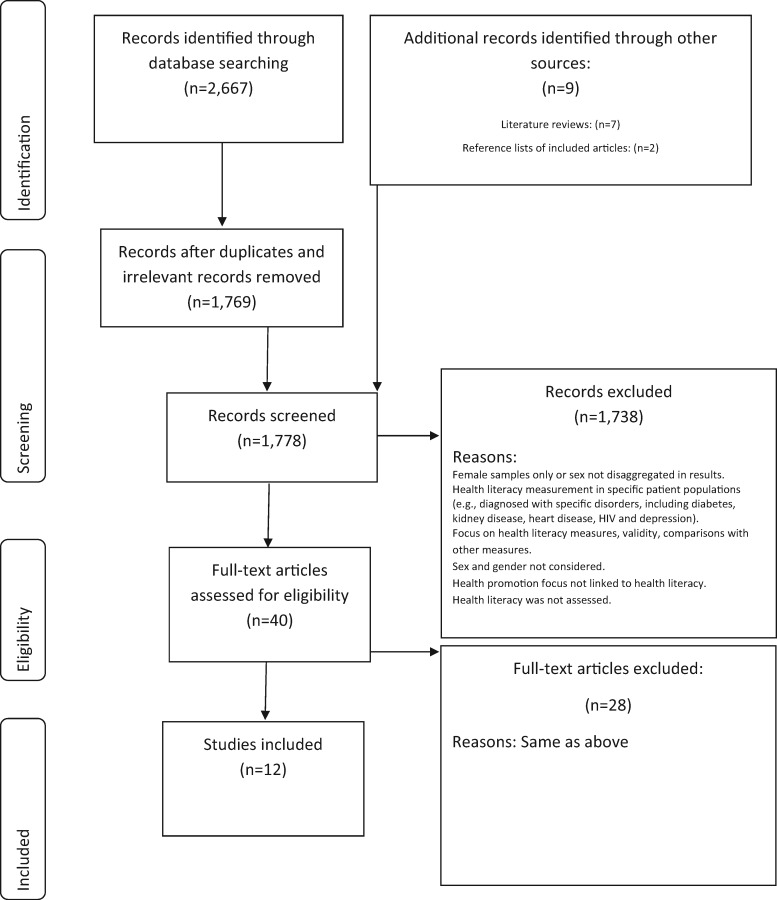

The initial search retrieved a total of 2667 articles. A title and abstract review was conducted to exclude articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria, and to remove duplicates by hand. In total, 1785 articles were allocated for further review. After excluding articles that did not report or focus on men’s health literacy, 10 articles were identified that met the review inclusion criteria. The references cited in these 10 articles were examined, in addition to the references of key discussion articles about men’s health literacy by Peerson and Saunders (Peerson and Saunders, 2009, 2011). This resulted in nine additional articles being retrieved and reviewed, two of which met the inclusion criteria. Of the 12 articles included in the current scoping review, 10 reported empirical studies, and 2 were literature reviews (see Figure 1 for a diagram summarizing article inclusion/exclusion).

Fig. 1:

Pathway of articles identified and excluded.

Analyses

Guided by the research question, ‘what are the similarities and differences in men’s health literacy research?,’ the following data were extracted from each of the 12 articles: methodology, sample characteristics, factors and findings relevant to men’s health literacy, and the authors’ recommendations for strategies or interventions to improve men’s health literacy. The reviewed articles were then compared and contrasted with regards to their focus on men’s health literacy in the findings, and the use of sex and gender lens’ to collect the data and interpret the results and the research methods. The scoping review findings are shared across these three categories, inclusive of descriptive thematic labels.

RESULTS

The 12 articles included in the current scoping review comprised six qualitative studies, three quantitative studies, one mixed methods study and two reviews. Four studies focussed on prostate cancer (Allen et al., 2007; Zanchetta et al., 2007; Friedman et al., 2009; Oliffe et al., 2010), three investigated colorectal cancer (CRC) (Molina-Barceló et al., 2011; Agho et al., 2012; Brittain et al., 2016), one described physical activity and nutrition awareness among school age boys (Drummond and Drummond, 2010), one examined food vulnerability in older bereaved men (Thompson et al., 2017) and one adopted a life course approach to investigating men’s health literacy (Clouston et al., 2016). The descriptive review article examined men’s melanoma (Geller et al., 2006), and the systematic review focussed on male heart disease and type 2 diabetes (Davey et al., 2015). The current scoping review did not duplicate studies included in Davey et al.’s (Davey et al., 2015) systematic review. Of the 12 articles, five studies were conducted in the USA, two in Canada, one in Australia, one in Spain, and one in the UK, while the reviews synthesized studies drawn from many countries. Overall, the studies reviewed for the current scope were conducted in higher income countries. Cancers were the primary disease in which men’s health literacy was addressed. Four articles (33% of the studies) focussed on prostate cancer. Four articles investigated the health literacy of African American men within the context of prostate or CRC, and two of the quantitative studies focussed on health literacy CRC screening and knowledge among African American men (see Table 1 for an annotated bibliography of included articles).

Table 1:

Annotated bibliography—men’s health literacy

| Author/year | Methods | Findings | Sex and gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Empirical studies | |||

|

|

|

No explicit discussion of sex or gender. The authors recommended future work involve female spouses in CRC education for men. Highlighted limits of written health promotion materials in the context of effectively targeting older men |

| Allen et al.(Allen et al., 2007)African American men’s perceptions about prostate cancer: implications for designing educational interventions Social Science & Medicine, 64, 11 | Methods: Qualitative Sample: Focus group interviews with 37 US-based healthy African American men and 14 prostate cancer survivors. Fourteen key community informants were also interviewed Procedure: The three subgroups were compared to evaluate their knowledge about the prostate, elevated prostate cancer risk among African American men, and controversies about screening | Participants who were prostate cancer survivors had greater knowledge about prostate cancer than healthy men. Barriers highlighted by key informants and the healthy men cohort cited inadequate access to services, mistrust of the health system, poor relationships with providers and threats to male sexuality as the underpinnings of African American men’s low levels of knowledge | Findings were discussed in terms of gender and prostate cancer perceived as a threat to male identityImplicit was the need to level hierarchies to waylay top down approaches to HL. Instead, shared decision-making interventions were argued for, inclusive of African American providers while acknowledging the role of prostate cancer survivors in educating peers |

|

|

Statistically significant differences in men’s lower HL and CRC scores were found compared to women. In contrast advancing age and being male were predictors of FOBT intention, and men were 1.7 times more likely than women to respond that they intended to have a colonoscopy in the next 6 months |

|

|

|

Almost half of male participants (47.5%) had poor health literacy. Findings indicated that women and men differed in risk for low health literacy in old age, with predictors unique to each sex. Men’s health literacy pathway was complex and includes cognitive decline in later life, which was not found with women |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HL-specific findings indicated that biomedical risk discourses and diagnostic measures including Gleason scores and PSA numbers were used to make treatment decisions. Understood also by participants was that these biomarkers were complex and their own experience may not reflect population-based statistics. The contextual use of health literacy and numeracy in this regard was mobilized by the men’s interactions at the PCSGs | The findings that men could increase HL within community-based PCSGs through other men as well as health care professionals presenting materials at the groups was linked to gendered understandings of men’s health. Specifically, the learnings at PCSGs ran counter to assertions that men are estranged from self-health and subordinate and marginalized in patient–provider interactions |

|

|

Formal comparison by sex, SES and participation in a CRC program. Findings indicated that CRC screening knowledge and beliefs about the disease were increased by program participation. However low SES was linked to HL issues and those factors along with being male were barriers to program participation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Partnerships within social and information networks were reported as crucial to men in understanding prostate cancer. They suggested the existence of affective and spiritual aspects of prostate cancer information shape how older men receive, live and deal with their health and illness. Highlighted the need to overcome two major barriers; professional medical language and the silence among men, in refuting linkages between men's formal education and health literacy levels | Rich description of men’s strategies for obtaining information to deal with prostate cancer. While challenges to traditional HL definitions were made and assertions that family and community organizations were key resources for men’s HL no explicit linkages to gender of sex analyses were made |

CRC, colorectal cancer; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; HL, health literacy; PCSG, prostate cancer support group.

A predominance for evaluating men’s medical knowledge

A majority of studies focussed on a narrow, medicalized understanding of men's health literacy rather than a broad, experiential and empowered state of health-related decision-making and help-seeking. The included studies drew insights from diverse groups of men. Though few conclusive empirical findings could be drawn, collectively they offered an important beginning to unraveling factors influencing men’s health literacy. To support these conclusions, a summary of the findings of these studies follows.

Men’s health literacy in the context of prostate cancer included Allen et al.’s (Allen et al., 2007) qualitative study highlighting the disproportionate burden of prostate cancer amongst African American men in pointing to knowledge deficits among healthy men compared to men with prostate cancer. Barriers highlighted by key informants (health care providers) and the healthy male cohort cited inadequate access to services, mistrust of the health system, poor relationships with providers and threats to male sexuality as the underpinnings of African American men’s low health literacy regards prostate cancer. Friedman et al. (Friedman et al., 2009) also examined African American men’s prostate cancer-related health literacy in a mixed methods study. Although the men’s health literacy scores were adequate based on analyses of survey questionnaire data, participant discussions revealed misperceptions about the risk factors for and causes of prostate cancer, as well as a lack of understanding about screening practices (Friedman et al., 2009). Friedman et al. (Friedman et al., 2009) argued for the effectiveness of verbal communication, suggesting church spaces were a valuable social setting in which African American men’s prostate cancer literacy could be advanced. The other two prostate cancer studies were qualitative and conducted in Canada with prostate cancer support groups (PCSGs) attendees. Zanchetta et al. (Zanchetta et al., 2007) evaluated men’s functional health literacy, reporting that education and health literacy levels were independent, amid asserting that social and cultural networks offered an important environment for men to learn from one another about prostate cancer. Oliffe et al. (Oliffe et al., 2010) described how PCSGs advanced men’s health literacy and numeracy skills by facilitating participants’ social interactions—and by extension their efforts toward health consumerism. For instance, PCSG attendees learned that prostate cancer biomarkers [i.e. prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and Gleason scores] were complex, and their own health experiences may not be reflected in population-based statistics (Oliffe et al., 2010).

Two of the three studies addressing CRC and men’s health literacy also focussed on African American males. Agho et al. (Agho et al., 2012) reported that while 72% of respondents correctly answered questions about CRC, 70% had never been screened for CRC. These findings were explained by the challenges participants reported in understanding hospital signs, medical instructions and their lack of confidence in completing medical forms (Agho et al., 2012). Brittain et al. (Brittain et al., 2016) pointed to African American men’s lower health literacy and CRC knowledge compared to women in contrasting men’s higher intention to be screened with fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and colonoscopy within 6 months. A qualitative study by Molina-Barceló et al. (Molina-Barceló et al., 2011) also reported sex differences for men’s and women’s participation and non-participation in CRC programs despite having similar programs and CRC knowledge levels. Specifically, men were motivated to participate in CRC programs by their partners while non-participant males were characterized as careless in lacking medical knowledge and concern for their health. Although cancer was the focus of the majority of articles in this scoping review, men’s health literacy was also explored in the area of nutrition and more broadly, perceptions of public health messages.

Food advertising and health literacy was described in a UK study by Thompson et al. (Thompson et al., 2017) which examined food vulnerability in older, British bereaved men. The study findings indicated that participants, all of whom were white and retired from managerial roles, had high health literacy levels, leading Thompson et al. (Thompson et al., 2017) to suggest community classes be provided to improve health literacy amongst less resourced men. Food advertising was also examined in the qualitative study by Drummond and Drummond (Drummond and Drummond, 2010) addressing boys’ physical activity and nutrition health literacy. Amid findings that boys’ health literacy skills were disadvantaged by marketing strategies positioning healthy foods as feminine, Drummond and Drummond (Drummond and Drummond, 2010) asserted that much confusion reigned about operationalizing or evaluating health literacy in boys’ and men’s health promotion programs.

Geller et al. (Geller et al., 2006) argued that better understanding men’s health literacy and their perceptions of public health awareness campaigns was central to advancing efforts to reduce the high prevalence of melanoma among males. In a systematic review of men’s health literacy related to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, Davey et al. (Davey et al., 2015) confirmed the complexities of researching men’s health literacy having identified 20 correlates for men’s health literacy and the predominance of studies focussing entirely on evaluating medical knowledge levels. Clouston et al. (Clouston et al., 2016), clarified a variety of indicators across the life-course that influenced health literacy later in life, including adolescent cognition and non-cognitive skills, lifetime cognitive function, adult cognition factors and parental SES. Emphasizing future research should examine men and women separately, the authors claimed that some factors including cognitive decline were more significant in men (Clouston et al., 2016).

Overall, the empirical findings revealed a predominance for evaluating men’s medical knowledge, and the limitations of that focus drew some important researcher recommendations. Consistent across the articles reviewed were calls to cease focussing entirely on printed educational materials, written medical information and the evaluation of men’s medical knowledge as the sole measure of health literacy. Instead, galvanizing men’s experiential and everyday understandings of and applications for health literacy was recommended to optimize future work. For example, Agho et al. (Agho et al., 2012) contended that written materials were a barrier to reaching African American men, a viewpoint shared by Friedman et al. (Friedman et al., 2009). Zanchetta et al. (Zanchetta et al., 2007) asserted that encounters with health professionals should not be viewed as the primary means by which men acquired prostate cancer literacy and Oliffe et al. (Oliffe et al., 2010) observed the power of discussions at PCSGs for advancing older men’s health literacy. In summary, the empirical evidence highlighted the predominance and limitations of didactic pedagogy and evaluating men’s medical knowledge, amid suggesting that men-friendly mechanisms and environments for delivering information were key considerations to advancing men’s health literacy research.

The role of sex and gender

The reviewed articles diversely attended to sex and/or gender in exploring and explaining men’s health literacy. Agho et al.’s (Agho et al., 2012) discussion of their findings were linked to CRC screening recommendations that future work should target female spouses as strong motivators to influence their men to have CRC screening. Highlighting sex differences in men’s lower CRC health literacy (amid higher intentions to undergo FOBT and colonoscopy), Brittain et al. (Brittain et al., 2016) suggested the influence of male gender norms in explaining this seemingly discordant relationship. Zanchetta et al. (Zanchetta et al., 2007) richly described men’s strategies for obtaining information about prostate cancer within social and community networks; however, the findings were not explicitly connected to a gender analysis. Davey et al. (Davey et al., 2015), in their review of men’s cardiovascular and diabetes health literacy, concluded, in general, there was a lack of explicit attention to gender. Thompson et al. (Thompson et al., 2017) linked gender, food vulnerability and health literacy in the background to their study, ahead of briefly citing participants’ alignment to traditional gender roles (i.e. women cook, men go to work and therefore men do not learn about food management) to explain their findings.

Within the context of sex-specific cancers, masculine ideals of competitiveness and self-reliance were listed as potential barriers for advancing men’s health literacy and participation in health promotion programs. Allen et al. (Allen et al., 2007) suggested that men preferred a leveling of hierarchies and peer-based education for prostate cancer because African American males had an inherent mistrust of the health system, poor relationships with health providers, and feelings of threatened sexual identity in association with prostate cancer. Friedman et al. (Friedman et al., 2009) highlighted how men talked about the embarrassment and fear of being seen as weak if they sought information about prostate cancer. Molina-Barceló et al. (Molina-Barceló et al., 2011) explained sex differences among CRC program participants and non-participants through men’s and women’s alignments to feminine and masculine ideals and heterosexual gender norms. They also argued that CRC messaging needed to be gender-sensitive and tailored, not only due to the higher incidence of CRC among men, but also because men’s and women’s program participation were motivated by different issues (Molina-Barceló et al., 2011). Masculine ideals were discussed by Drummond and Drummond (Drummond and Drummond, 2010) to explain boys’ beliefs about specific manly food practices and sports activities ahead of lobbying policy makers and researchers to delink future health education programs from such gender stereotypes. Oliffe et al. (Oliffe et al., 2010) argued against assertions that men are estranged from self-health, highlighting the value of PCSGs for affording ‘new’ masculine ideals and norms to advance men’s health literacy—and by extension their patient–provider interactions. Geller et al. (Geller et al., 2006) highlighted how 25% of male melanomas were found by female partners in recommending future gender research to canvas men and extract how best to message males directly with melanoma information. Clouston et al.’s (Clouston et al., 2016) sex comparison prompted their call for future gender-specific research to guide targeted approaches for working with males to improve health literacy over the life course.

In summary, sex comparisons were used by some researchers to highlight health literacy differences between males and females, and lobby gender-sensitized research to explain and tailor men’s health promotion programs. The gender analyses were somewhat limited wherein masculinities were most often offered as one of many potential explanatory mechanisms for men’s health literacy levels. Intriguingly however, many recommendations for gender-sensitive approaches to examining men’s health literacy were made to guide future health promotion work.

Cross-sectional study designs affording descriptive and evaluative findings

The methods in the reviewed empirical articles comprised six qualitative studies (Allen et al., 2007; Zanchetta et al., 2007; Drummond and Drummond, 2010; Oliffe et al., 2010; Molina-Barceló et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2017); three quantitative studies (Agho et al., 2012; Brittain et al., 2016; Clouston et al., 2016) and one mixed methods study (Friedman et al., 2009). The qualitative studies used individual and/or focus group interviews with sample sizes ranging from 15 to 90 male participants (Mean = 53). The mixed methods study included 25 male participants (Friedman et al., 2009). The quantitative studies, two of which evaluated CRC interventions among African Americans, drew on samples of 142 males (Agho et al., 2012) and a mixed sex sample [N = 817, including 384 (47%) males] (Brittain et al., 2016), while the life course quantitative study utilized a data set comprising a 2212 mixed sex sample with 1058 (48%) males (Clouston et al., 2016). The systematic review by Davey et al. (Davey et al., 2015) included nine studies, which were all cross-sectional designs, and ranged from 97 to more than 19 000 participants.

The ways in which health literacy was conceptualized varied considerably across the included studies with researchers using inductively derived understandings and/or soliciting responses to pre-determined health literacy measures. The studies that employed survey questionnaires to measure men’s health literacy used diverse tools. For example, Agho et al. (Agho et al., 2012) examined correlations between health literacy and self-reported awareness of CRC using a validated 16 item survey questionnaire (Chew et al., 2004). Brittain et al. (Brittain et al., 2016) evaluated a range of independent variables including health literacy using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (Arozullah et al., 2007), an in-person administered test of respondents’ recognition and pronunciation of common medical terms, the aggregate score of which was used to assign a literacy grade level. Friedman et al. (Friedman et al., 2009) assessed prostate cancer prevention literacy using the Shortened Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA), and the Cloze procedure, both of which tested comprehension of print materials. Clouston et al. (Clouston et al., 2016) differentiated life time predictors of health literacy by sex, using the validated Newest Vital Sign (NVS) questionnaire wherein respondents were shown a nutrition label and asked a series of six questions by an interviewer. Most of the quantitative studies examined men’s health literacy in the context of assessing the effectiveness of specific programs or interventions.

Among the qualitative studies, Molina-Barceló et al. (Molina-Barceló et al., 2011) conducted eight focus groups structurally designed to compare participants’ perceptions about screening across three dimensions: sex, SES and participation/non-participation in a CRC program. Zanchetta et al. (Zanchetta et al., 2007) individually interviewed men with prostate cancer to understand their social and cultural learning experiences and contextualize participants self-assessed functional health literacy survey data. To ensure rigor and representativeness in the researcher’s interpretations of the data, this study also employed member checking by sharing the findings with 6 of the 15 participants to solicit their feedback. Oliffe et al.’s (Oliffe et al., 2010) ethnographic study of 54 Canadian-based male PCSGs attendees, triangulated leaders and long- and short-term attendees perspectives along with participant observations of meetings at 16 PCSGs to describe men’s health literacy and numeracy, and how this knowledge was used to make sense of, and/or manage their prostate cancer. Allen et al.’s (Allen et al., 2007) qualitative study comprising focus group interviews with 37 US-based healthy African American men, 14 prostate cancer survivors and 14 key community informants (health care providers) focussed on health literacy in the specific context of prostate cancer risk and screening. Thompson et al. (Thompson et al., 2017) undertook unstructured narrative-based interviews with 20 older, bereaved men to better understand the influences on their food and diet behaviors, practices and knowledge from the perspective of Nutbeam’s (Nutbeam, 2000) health literacy framework.

In summary, the diverse methods used to explore men’s health literacy tended toward evaluating medical knowledge. The predominance of cross-sectional study designs also limited what could be claimed as prevailing patterns or program-related health literacy benefits. The lack of pre–post, longitudinal and/or randomized controlled studies along with eclectic methodologies and measures reflects an emergent area of research; however, these characteristics also reproduce, to some extent, longstanding debates about how best to define and operationalize men’s health literacy.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The current scoping review identified some key tensions, barriers and gaps in the emergent research addressing men’s health literacy. There continues to be a reliance on evaluating medical knowledge to gauge men’s health literacy with a focus on sampling by disease category. In parallel, poorly understood is how socially constructed masculine identities, roles and relations connect with men’s health literacy and inequities, and practices including disease screening. The findings also confirm the absence of an overarching conceptualization of, and application for men’s health literacy, and this is reflected in the lack of connectedness with men’s health promotion programs. At the same time, this small body of research asserted the profound limits of educational materials and print-based medical information as the primary means to improving men’s health literacy and health outcomes. These findings confirm earlier commentaries by Peerson and Saunders (Peerson and Saunders, 2009, 2011) that the lack of empirical understandings about men’s health literacy obscures strategies to guide the design, implementation and formal evaluation of emergent and existing men’s health promotion programs. In terms of addressing these issues, community-based settings where men ordinarily reside surface as important avenues to both effectively advance men’s health literacy and their collective health promotion practices.

The lack of consistency in the measurement of men’s health literacy, and the tendency to focus on medical knowledge acquisition, delinked from gender, challenges efforts to synthesize and advance the field. It also supports the need for gender-sensitive measures of men’s health literacy. In line with Peerson and Saunders (Peerson and Saunders, 2009, 2011) we suggest that these measures should be purposefully designed to understand and build an empirical base for men’s health literacy. The findings from the current scoping review confirm that knowledge alone does not inform or make predictable men’s health literacy or their practices. Yet, recognizing men’s health practices (as distinct from medical knowledge) as underpinned by resources in which health literacy is central, are key to contextualizing men’s engagement with professional health care services and/or self-management of their health and/or illness. For instance, beyond knowledge levels, the use of health literacy measures among men diagnosed with prostate cancer can highlight the assistance needed with specific concerns including psychological distress (Song et al., 2012). Adapting existing health literacy tools to focus on specific men’s health issues including depression and suicidality may also contribute important insights across a range of health promotion and illness contexts (Oliffe et al., 2016).

In terms of frameworks, Nutbeam’s (Nutbeam, 2000) public health perspective continues to resonate as critically important to fully unpacking and applying men’s health literacy research. As Raphael (Raphael, 2017) has reinforced, structural health inequities demand attention, as these are vital to effectively working with resource poor male subgroups (i.e. Indigenous and low SES). Akin to critiques of health promotion for being too focussed on the individual, health literacy, as Nutbeam (Nutbeam, 2000) asserted, must focus on ‘personal and community empowerment’ (p. 266). Bearing this in mind, multiple intersecting social determinants of health need to be appraised, addressed, and regularly evaluated to advance men’s health literacy and the well-being of men and their families. Reflected in the current scoping review findings, herein perhaps resides the two largest knowledge gaps (and challenges). First, there is an absence of work focussed on the interconnections between men’s health literacy and structural health inequities. As Stormacq et al.’s (Stormacq et al., 2018) review asserted, health literacy mediates social conditions and health outcomes to such an extent that health literacy should be framed as a modifiable risk factor for health inequities. There may be benefit to employing mixed methods with sequential study designs to inductively derive health literacy survey items through qualitative methods, which could be further pilot tested among discrete subgroups of men (i.e. by age, disease, ethnicity, SES and sexual orientation) (Oliffe et al., 2019). Inversely, surveys evaluating men’s health literacy could inform qualitative interview questions to collect end user information to inform the design and evaluation of targeted men’s health promotion programs.

Second, global health movements have increasingly highlighted the flow on benefits to families and partners made possible through effective men’s health promotion efforts (Oliffe, 2015; Gaiha and Gillander Gådin, 2018). For example, work targeting smoking cessation among fathers within the pregnancy and postpartum period highlighted noteworthy health benefits for men and their children and partners (Oliffe et al., 2010). Research focussed on couples, gender relations and contraceptive practices in India highlighted the importance of addressing positive masculinities in health promotion programs (Gaiha and Gillander Gådin, 2018). Moving forward, men’s health literacy research might contribute empirical evidence about the full range of health gains through effectively educating and intervening with men within the context of their interpersonal and social interactions.

Related to these aforementioned challenges, there is consensus that men’s health promotion programs that are offered in accessible men-friendly spaces and built on lay language and information applicable to men’s everyday lives will best muster their collective self-health (Ogrodniczuk et al., 2016). While these principles directly relate to men’s health literacy as a personal asset (Nutbeam, 2015), capturing the specificities of key literacy constructs to optimize men’s health promotion programs is critical. There is great potential for extending understandings of men’s health literacy within the context of novel community-based men’s health promotion programs including those that are offered online (Duncan et al., 2014; Ogrodniczuk et al., 2018). Premised on meeting men in places they frequent with accessible language, rather than reinforcing reliance on biomedical services, health literacy research could provide much needed empirical evidence upon which to design, sustain and scale effective community-based men’s health promotion programs. Much could also be learned about men’s health literacy by examining existing and emergent health promotion programs. For example, military men returning to civilian life were recruited to group-based counseling, but the service was not framed as ‘counseling’; men were invited to attend as a means to helping other returned soldiers—rather than needing help themselves (Kivari et al., 2018). Appealing to military men’s comrade values, the program leads used colloquial language to engage men in the work of ‘dropping their baggage.’ Similarly, the US-based black barbershop programs screened men for high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease (Releford et al., 2010; Victor et al., 2011) wherein the focus was on knowing if there was a ‘problem’ that should be addressed to reduce the risk of illness. These two health promotion program examples offer key insights to what counts as men’s health literacy among specific vulnerable male subgroups. The language used in, and to market these aforementioned programs might be articulated as health literacy principles to guide some targeted men’s health promotion programs.

In conclusion, we suggest important gains can be made by both inductively deriving insights to what constitutes and counts as men’s health literacy as well as working deductively to measure and report patterns and diversity within and across subgroups of men. Within these contexts men’s health literacy and health promotion programs should be intricately tied making available empirical insights to formally evaluate efforts for advancing the health of men and their families. While working with subgroups of men it is also ever clear that structural health inequities demand government and policy attention to effectively tailor and target efforts for advancing men’s health literacy—and by extension their meaningful engagement with health promotion programs and practices.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant [grant number 11R06913].

REFERENCES

- Agho A. O., Parker S., Rivers P. A., Mush-Brunt C., Verdun D., Kozak M. A. (2012) Health literacy and colorectal cancer knowledge and awareness among African American males. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 50, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. D., Kennedy M., Wilson-Glover A., Gilligan T. D. (2007) African American men’s perceptions about prostate cancer: implications for designing educational interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 2189–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R., Hall B. J., Doyle J., Waters E. (2011) ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. Journal of Public Health, 33, 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arozullah A. M., Yarnold P. R., Bennett C. L., Soltysik R. C., Wolf M. S., Ferreira R. M.. et al. (2007) Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Medical Care, 45, 1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K., Christy S. M., Rawl S. M. (2016) African American patients’ intent to screen for colorectal cancer: do cultural factors, health literacy, knowledge, age and gender matter? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27, 51–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council on Learning. (2007) Health Literacy in Canada: Initial Results from the International Adult Literacy and Skills Survey 2007. Canadian Council on Learning, Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council on Learning. (2008) Health Literacy in Canada: A Healthy Understanding 2008. Canadian Council on Learning, Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Chew L. D., Bradley K. A., Boyko E. J. (2004) Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Family Medicine, 36, 588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouston S. A., Manganello J. A., Richards M. (2016) A life course approach to health literacy: the role of gender, educational attainment and lifetime cognitive capability. Age and Ageing, 46, 493–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. (1995) Masculinities. Polity Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000) Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey J., Holden C. A., Smith B. J. (2015) The correlates of chronic disease-related health literacy and its components among men: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 15, 589.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M., Drummond C. (2010) Interviews with boys on physical activity, nutrition and health: implications for health literacy. Health Sociology Review, 19, 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan M., Vandelanotte C., Kolt G. S., Rosenkranz R. R., Caperchione C. M., George E. S.. et al. (2014) Effectiveness of a web- and mobile phone-based intervention to promote physical activity and healthy eating in middle-aged males: randomized controlled trial of the ManUp study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16, e136.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Corwin S. J., Dominick G. M., Rose I. D. (2009) African American men’s understanding and perceptions about prostate cancer: why multiple dimensions of health literacy are important in cancer communication. Journal of Community Health, 34, 449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiha S. M., Gillander Gådin K. (2018) ‘No time for health’: exploring couples’ health promotion in Indian slums. Health Promotion International, doi: 10.1093/heapro/day101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller J., Swetter S. M., Leyson J., Miller D. R., Brooks K., Geller A. C. (2006) Crafting a melanoma educational campaign to reach middle-aged and older men. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, 10, 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivari C. A., Oliffe J. L., Borgen W. A., Westwood M. J. (2018) No man left behind: effectively engaging male military veterans in counseling. American Journal of Men's Health, 12, 241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Owens R. (2002) The Psychology of Men’s Health Series. Open University Press, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K. K. (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Barceló A., Trejo D. S., Peiró-Pérez R., López A. M. (2011) To participate or not? Giving voice to gender and socio-economic differences in CRC screening programmes. European Journal of Cancer Care, 20, 669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (2000) Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (2008) The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 67, 2072–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (2015) Defining, measuring and improving health literacy. Health Evaluation and Promotion, 42, 450–456. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R., Hunt K., Hart G. (2005) ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk J. S., Oliffe J. L., Beharry J. (2018) HeadsUpGuys: a Canadian online resource for men with depression. Canadian Family Physician, 64, 93–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk J. S., Oliffe J. L., Kuhl D., Gross P. A. (2016) Men’s mental health—spaces and places that work for men. Canadian Family Physician, 62, 463–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L. (2015) Three key notes from my address at the men, health and wellbeing conference. International Journal of Men’s Health, 14, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L., Johnson J. L., Kelly M. T., LeBeau K. (2010) Fathers: locating smoking and masculinity in the postpartum. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L., McKenzie M. M., Hislop T. G., Gerbrandt J. S., Oglov V. (2011) Prostate cancer support groups, health literacy and consumerism: are community-based volunteers re-defining older men’s health? Health, 15, 555–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Bottorff J. L., Sarbit G. (2012) Supporting fathers’ efforts to be smoke-free: program principles. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44, 64–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Hannan-Leith M. N., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Black N., Mackenzie C. S., Lohan M.. et al. (2016) Men’s depression and suicide literacy: a nationally representative Canadian survey. Journal of Mental Health, 25, 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Rice S., Kelly M. T., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Broom A., Robertson S.. et al. (2019) A mixed methods study of the health-related masculine values among young Canadian men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 20, 310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Robertson S., Frank B., McCreary D. R., Tremblay G., Goldenberg L. (2010) Men’s health in Canada: a 2010 update. Journal of Men's Health, 7, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Peerson A., Saunders M. (2009) Health literacy revisited: what do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promotion International, 24, 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peerson A., Saunders M. (2011) Men’s health literacy in Australia: in search of a gender lens. International Journal of Men's Health, 10, 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael D. (2017) Implications of inequities in health for health promotion practice In Rootman I., Pederson A., Frohlich K., Dupéré S. (eds), Health Promotion in Canada, 4th edition, Chapter 8. Canadian Scholars Press, Toronto, ON, pp. 146–166. [Google Scholar]

- Releford B. J., Frencher S. K., Yancey A. K., Norris K. (2010) Cardiovascular disease control through barbershops: design of a nationwide outreach program. Journal of the National Medical Association, 102, 336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L. M., Douglas F., Ludbrook A., Reid G., van Teijlingen E. (2008) What works with men? A systematic review of health promoting interventions targeting men. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 141.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M., Robertson S. (2010) Young men’s health promotion and new information communication technologies: illuminating the issues and research agendas. Health Promotion International, 25, 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rootman I., Ronson B. (2005) Literacy and health research in Canada: where have we been and where should we go? Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96, S62–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumrill P. D., Fitzgerald S. M., Merchant W. R. (2010) Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work, 35, 399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L., Mishel M., Bensen J. T., Chen R. C., Knafl G. J., Blackard B.. et al. (2012) How does health literacy affect quality of life among men with newly diagnosed clinically localized prostate cancer? Cancer, 118, 3842–3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormacq C., Van den Broucke S., Wosinski J. (2018) Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promotion International, doi: 10.1093/heapro/day062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J., Tod A., Bissell P., Bond M. (2017) Understanding food vulnerability and health literacy in older bereaved men: a qualitative study. Health Expectations, 20, 1342–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor R. G., Ravenell J. E., Freeman A., Leonard D., Bhat D. G., Shafiq M.. et al. (2011) Effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for improving hypertension control in Black men: the BARBER-1 study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wagner C., Knight K., Steptoe A., Wardle J. (2007) Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 6, 1086–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S., Chen J., Atchison R. (2008) Relationship of preventive health practices and health literacy: a national study. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32, 227–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanchetta M. S., Cognet M., Xenocosta S., Aoki D., Talbot Y. (2007) Prostate cancer among Canadian men: a transcultural representation. International Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 224–258. [Google Scholar]