Approximately one month before the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic on March 11, 2020, we wrote an editorial regarding fear of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which we referred to as coronaphobia (Asmundson & Taylor, 2020). In that editorial, we highlighted the rapid rise of infections and related deaths, common behavioral strategies being used at the time to thwart infection (e.g., handwashing, social distancing), evidence of the emerging psychological impact, and potential strategies for action on the part of mental health professionals. The world has changed dramatically over the last eight months. Below we revisit several key issues regarding our initial coronaphobia conceptualization, provide a brief update on the current state-of-the-art, discuss the newly introduced COVID Stress Syndrome and COVID Stress Disorder, and highlight important areas for future investigation.

1. The dynamic nature of pandemic-related distress

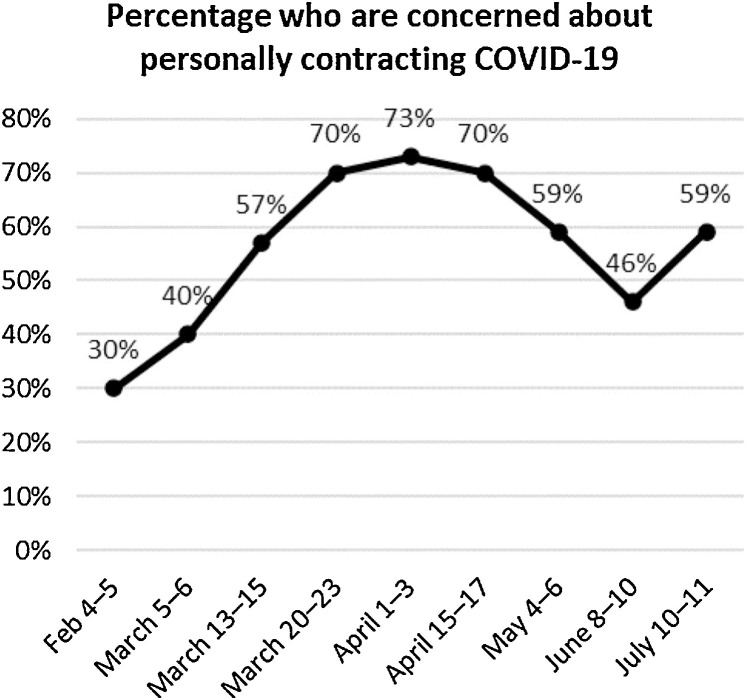

The novel coronavirus continues to spread globally. The numbers of infections and deaths are staggering, and we are in the midst of a second wave in various parts of the world. At present, the mortality rate of the virus is approximately 3%, with 44.5 million cases and 1.2 million deaths worldwide (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic, accessed October 29, 2020). Across communities, levels of distress about COVID-19 have fluctuated over the course of the pandemic, corresponding approximately to the perceived local threat of infection. This is illustrated in Fig. 1 , which summarizes the results of an opinion poll of Canadian adults (N=1,503), surveyed from February to July 2020 (Angus Reid Institute, 2020). Here it can be seen that personal concern about becoming infected steadily rose during the early phases of the pandemic (February-April), which was when cases were steadily rising across Canada, and when lockdown (i.e., self-isolation) was becoming widely implemented. Personal concern about becoming infected then diminished from April to June as health authorities began offering reassuring messages that the rates of infection were declining. As lockdown restrictions were eased in June people resumed congregating in progressively larger numbers, and so the rates of infection began to rise again in June and July. Correspondingly, personal concern about becoming infected also began to rise. These data underscore the fact that pandemics are dynamic events (Taylor, 2019). This has important implications for anxiety disorders research; specifically, findings based on a single point in time may not generalize to other periods of the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers need to consider this issue when interpreting their findings, especially when these are based on cross-sectional designs.

Fig. 1.

Fluctuations in concerns about personally contracting COVID-19. © Angus Reid Institute (2020). Reprinted by permission.

2. From coronaphobia to COVID stress syndrome

Numerous recent studies have shown global increases in the prevalence and severity of COVID-19-related depression, anxiety, and stress (Xiong et al., 2020)--all likely stemming from challenges and changes to daily life in attempts to thwart viral spread (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020)--as well as other mental health issues such as traumatic stress (see Boyraz, Legros, & Tigershtrom, 2020, in this volume) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Likewise, there have been many studies documenting global increases in COVID-19-specific fear and coronaphobia; indeed, a search of Google Scholar identified well over 100 manuscripts focusing on fear factors pertinent to the COVID-19. Yet, we now know that unidimensional mental health constructs and conventional diagnoses are oversimplified and insufficient representations of the nuanced mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Stemming from the development of the COVID Stress Scales (Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Fergus et al., 2020), we found that distress-related responses to COVID-19 comprise a multi-faceted network of interconnected symptoms, which we called the COVID Stress Syndrome (Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, McKay et al., 2020). This syndrome--anchored by COVID-19 danger and contamination fears at its core and with connections to fear of adverse socio-economic consequences, xenophobia, traumatic stress symptoms, and checking and reassurance seeking--is associated with panic buying, excessive avoidance of public places, and maladaptive attempts at coping (e.g., over-eating and increased consumption of alcohol and drugs) (Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Rachor, & Asmundson, 2020; Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, McKay et al., 2020).

3. Introducing COVID stress disorder

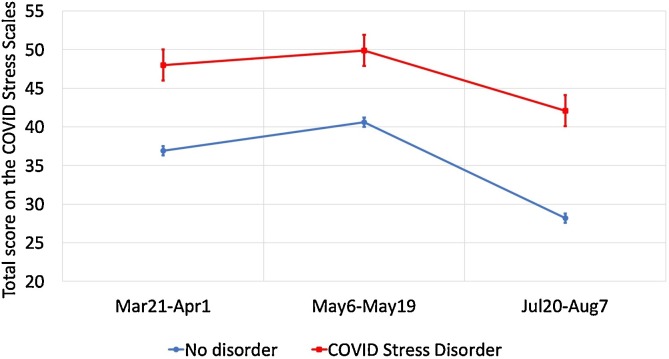

As part of our ongoing research into the COVID Stress Syndrome, we assessed participants at three points during 2020 and classified them in terms of whether or not they had severe functional impairment (social or occupational) due to COVID-19-related distress (N = 2,078 adults from Canada and the United States). Participants having severe impairment (13 % of the sample) were classified as having COVID Stress Disorder. Fig. 2 shows the COVID Stress Scales means and standard errors for the disordered and non-disorder groups at the three assessment points. Again, the findings emphasize the dynamic nature of pandemics. COVID-19-related distress is not static and may fluctuate over time. An issue currently under investigation concerns the nature of COVID Stress Disorder. Its defining features, as described above, consist of a combination of infection-related and other fears, traumatic stress symptoms, and compulsive checking. As such, the disorder cannot be simply reduced to an existing DSM-5 diagnostic category such as illness anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or PTSD. It is feasible that COVID Stress Disorder might be a type of adjustment disorder. If this is the case, then it should abate once the pandemic subsides. Alternatively, the disorder might become chronic for some individuals. This is an important area of ongoing investigation that has implications for current and post-pandemic mental health service needs.

Fig. 2.

Total scores on the COVID Stress Scales for participants meeting criteria for COVID Stress Disorder (squares) and participants who did not meet criteria (circles).

4. In search of a comprehensive model of pandemic-related mental health

As reported by Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Rachor et al. (2020) in this volume, the COVID Stress Syndrome (defined dimensionally in terms of the degree of severity) appears to be at the center of a larger network of pandemic-relevant mental health constructs, with negative connections (i.e., negative correlations) with beliefs that pandemic-related threat is exaggerated and disregard for public health recommendations, and positive connections with self-protective behaviors. The findings from studies focused on posttraumatic stress symptoms and putative PTSD in response to COVID-19, as well as studies of health-related obsessions and compulsions, may be best understood in the context of a multifaceted network of pandemic-related distress. Further research is needed to determine where vulnerability factors for emotional distress fit into the network (e.g., trait variables such as negative emotionality, intolerance of uncertainty, disgust sensitivity, boredom proneness). The question of how the network might change over time and circumstance also remains to be investigated. Growing lockdown fatigue as the pandemic drags on, and reassuring versus anxiety-evoking messages from political and other leaders, may alter elements in the network (e.g., alter levels of worry about socio-economic impacts), which may, in turn, alter other elements of the network.

Further research is also needed to determine how COVID-related fears, and the COVID Stress Syndrome and Disorder, are related to other psychopathological phenomena. Research shows that during the pandemic there have been increases in various kinds of psychological and behavioral problems, apart from those noted above, including depression and suicidal ideation, substance abuse, and lockdown-related domestic violence (Czeisler et al., 2020; Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, Allbright, & Dailey, 2020; Mahase, 2020; Sun et al., 2020).

5. Evidence-based intervention and associated challenges

The search for evidence-based and accessible mental health interventions continues and, with the increasing psychological burden of the pandemic, is becoming just as important as the search for a vaccine. While there have been some successes in adapting general online cognitive-behavioral interventions to aid those with significant COVID-19-related stress (e.g., Wahlund et al., 2020), there remains a critical need for more tailored, accessible, and scalable treatments moving forward. Much of the developmental work, testing, and implementation of these tailored interventions remains to be done. Such work may be informed by a nuanced understanding of the natural fluctuations in COVID-related distress, the reciprocal roles of the various symptoms comprising the COVID Stress Syndrome, the functional limitations associated with COVID Stress Disorder, as well as more nuanced influences of symptom presentation. For example, in this volume Cox, Jessup, Luber, and Olatunji (2020) show that disgust proneness contributes to maladaptive anxiety responses and, in doing so, may represent a target for treatment. This work may also be informed by better understanding challenges that COVID-19 creates for the treatment of anxiety-related disorders, such as illustrated in this volume by Sheu, McKay, and Storch (2020) regarding applications of exposure and response prevention for OCD during a pandemic.

6. Important research directions

It is unclear what course the pandemic will take or how long it will persist. There are some clues as to how it might end, primarily hinging on the steadfastness with which people adhere to public health measures such as social distancing and handwashing, the development of new antiviral medications, and the discovery of a vaccine. Notwithstanding, the emotional toll of the pandemic, combined with the anticipation of a COVID-19 endemic and other outbreaks of emerging infectious disease, necessitates continued research to better understand and treat pandemic-related distress. It is now well established that COVID-19 has increased the prevalence and severity of depression, anxiety, stress, as well as specific clinical conditions, including PTSD and OCD. We encourage researchers to turn their attention to better understanding how these mental health impacts are linked and, within the context of a multidimensional conceptualization, to develop evidence-based public health campaigns and interventions that will help alleviate pandemic-related distress. We also encourage researchers to expand the scope of their investigations to include attempts to understand resiliency and posttraumatic growth in the context of COVID-19. Although the pre-COVID-19 research suggests that most people are resilient to stress (Galatzer-Levy, Huang, & Bonanno, 2018), less is known about the factors that are most central for the development of pandemic-related resilience. Issues concerning posttraumatic growth are more complex. Some people might have genuine growth (e.g., demonstrably growing levels of stress resiliency), whereas for other people this growth might be illusory. This issue remains to be investigated.

7. Moving forward on the mental health frontlines

There has been a considerable amount of research on the general mental health impacts of COVID-19 and, as illustrated in the papers appearing in the COVID Content section in prior volumes of the Journal of Anxiety Disorders, on its specific effects on anxiety- and stress-related constructs and conditions. Notwithstanding this widespread empirical attention, we remain in the early stages of a comprehensive understanding of pandemic-related distress, its multidimensional conceptualization (i.e., the COVID Stress Syndrome), and linkages to pre-existing and new-onset anxiety-related disorders. As such, we conclude this year end editorial in a similar fashion to our earlier editorial in February of 2020; specifically, it is vitally important that we all focus our efforts to understand the mental health fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and to find evidence-based ways of addressing these issues. This will be important not only for the current COVID-19 pandemic but also for its possible endemic presence and for future pandemics. The Journal of Anxiety Disorders will, in addition to publishing high impact and innovative work regarding the anxiety-related disorders in general, continue to prioritize manuscripts that meaningfully advance understanding and treatment of pandemic related distress.

Acknowledgements

Some of the research mentioned herein was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#439751) and the University of Regina.

References

- Angus Reid Institute (2020, July 15). COVID-19: Canadian concern over falling ill on the rise again. http://angusreid.org/covid-concern-rising/print, retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Asmundson G.J.G., Taylor S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;70:102196. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyraz G., Legros D.N., Tigershtrom A. COVID-19 and traumatic stress: The role of perceived vulnerability, COVID-19-related worries, and social isolation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;76:102307. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R.C., Jessup S.C., Luber M.J., Olatunji B.O. Pre-pandemic disgust proneness predicts increased coronavirus anxiety and safety behaviors: Evidence for a diathesis-stress model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;76:102315. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.É., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy I.R., Huang S.H., Bonanno G.A. Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 2018;63:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D.S., Cloonan S.A., Taylor E.C., Allbright M.C., Dailey N.S. Trends in suicidal ideation over the first three months of COVID-19 lockdowns. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293:113390. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahase E. COVID-19: EU states report 60% rise in emergency calls about domestic violence. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition) 2020;369:m1872. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383:510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu J.C., McKay D., Storch E.A. COVID-19 and OCD: Potential impact of exposure and response prevention therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;76:102314. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Li Y., Bao Y., Meng S., Sun Y., Schumann G., et al. Increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. The American Journal on Addictions. 2020;29:268–270. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; Newcastle Upon Tyne: 2019. The psychology of pandemics: Preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Landry C.A., Paluszek M.M., Fergus T.A., McKay D., Asmundson G.J.G. Development and initial validation of the COVID stress scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;72:102232. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Landry C.A., Paluszek M.M., McKay D., Fergus T., Asmundson G.J.G. COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety. 2020;37:706–714. doi: 10.1002/da.23071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Landry C.A., Paluszek M.M., Rachor G.S., Asmundson G.J.G. Worry, avoidance, and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive network analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;76:102327. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund T., Mataix-Cols D., Lauri K., de Schipper E., Ljótsson B., Aspvall K., et al. July 12. Brief online cognitive behavioural intervention for dysfunctional worry related to the COVID-19 pandemic: Pre-specified interim results from a randomised trial. PsyArXiv. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/rdka2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H.…McIntyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]