Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effectiveness of moxibustion at different times of the menstrual cycle for patients with primary dysmenorrhea (PD).

Patients and Methods

Participants were 208 patients allocated to three controlled groups: one pre-menstrual treatment group (Group A), one menstrual-onset treatment group (Group B), and one waiting-list group (Group C). Groups A and B received the same intervention of moxibustion on points SP6 and RN4 but at different times. Group C, the waiting-list group, received no treatment throughout the study. Cox Menstrual Symptom Scale (CMSS) score was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were visual analog scale (VAS) score of pain intensity, self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) score, and self-rating depression scale (SDS) score. CMSS and VAS scores were obtained at the baseline stage (three cycles), treatment stage (three cycles), and follow-up stage (three cycles), a total of seven evaluations. SAS and SDS scores were obtained on the day of group allocation and the first day of the follow-up stage, a total of two evaluations.

Results

Baseline characteristics were comparable across the three groups. Pain duration (CMSS score) was significantly higher in Group C than in the other two groups at each evaluation (P<0.001). There was also a significant difference in the improvement in pain duration between Group B and Group C (P<0.001) throughout the trial. There were no significant changes in pain severity (CMSS score) after the 3-month treatment in Group A and Group B (P>0.05). Secondary outcomes showed that pre-menstrual moxibustion (Group A) was as effective as menstrual-onset moxibustion (Group B) in relieving pain intensity (VAS score) and negative mood (SDS and SAS scores).

Conclusion

Moxibustion appears as an effective treatment for PD. Pre-menstrual application is more effective than menstrual-onset application.

Trial Registration Chictr.org.cn Identifier

ChiCTR-TRC-14004627.

Keywords: primary dysmenorrhea, moxibustion, intervention time, randomized controlled trial, pain relief

Introduction

Primary dysmenorrhea (PD) is one of the most common gynecological diseases.1–3 It is defined as pain that occurs with menstruation in the absence of pelvic pathology4 and that is often accompanied by headache, nausea, tiredness, vomiting, irritability, diarrhea, and a general feeling of discomfort.5 Between 43% and 91% of adolescent females (younger than 20 years) report PD; however, prevalence declines with age.6 PD morbidity ranges from 45% to 97% across different ages and nationalities.7–9 Despite its high incidence rate and wide geographic distribution, the causes and mechanisms of PD remain unclear. The most widely accepted theory suggests that PD is associated with increased synthesis of prostaglandins (PGs), resulting in dysrhythmic uterine contractions and decreased blood flow.10–12

Drug therapies play an important role in relieving pain from dysmenorrhea. The first-line medication is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).13 NSAIDs are used as a PG inhibitor for pain relief. Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) are regarded as the second-line drug for patients who do not respond or are intolerant to NSAIDs. Both medications have rapid and reliable effects on pain. However, long-term use of NSAIDs or OCPs is associated with various side effects.1,14,15

The limitations of drug treatments have made non-pharmacological pain relief necessary for PD patients. Of all complementary and alternative therapies, moxibustion may be the most appropriate option. In Chinese gynecology, PD is induced by qi stagnation and blood stasis. Moxibustion involves the application of heat to the body surface, usually on selected acupoints, to promote blood circulation and remove blood stasis. Our previous study showed that moxibustion was more effective than drugs for PD pain relief.16

Although many researchers choose to apply moxibustion before menstruation,17 one meta-analysis demonstrated no difference in the effect of moxibustion on PD at different intervention times.18 However, the quantity and quality of the included studies were low, so more high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with large samples are needed to investigate the effectiveness of moxibustion at different intervention times in PD management.

In light of the existing clinical evidence, the study aim was to investigate the differential effect of moxibustion before and during the menstrual cycle on dysmenorrhea symptoms in PD patients.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Population

The study was conducted as a single-centered, single-blinded, and parallel-grouped trial (Supplement 1). Participants with PD were recruited from a few local universities and enrolled in the study from July 2014 to September 2016. The inclusion criteria were based on the Primary Dysmenorrhea Consensus Guidelines.4 Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (CDUTCM) was responsible for this clinical trial. All treatments were conducted at the third teaching hospital of CDUTCM, Chengdu, Sichuan, China.

All participants were required to provide written informed consent and to keep a PD diary throughout the study. Participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: aged 18 to 30 years; no birth history; regular menstrual cycles; TCM diagnosis of qi and blood stagnation and cold-damp coagulation (Table S1);19 rated pain intensity not less than 4 on a visual analog scale (VAS).

Participants who met one or more of the following criteria were excluded: secondary dysmenorrhea; serious contraindications (eg a life-threatening condition or progressive central nervous disorder); mental illness; preparing for pregnancy; use of pain killers for PD treatment within the last 2 weeks prior to enrollment; use of any other PD treatments within the previous 3 months prior to enrollment.

Sample Size

The sample size calculation was based on a previous pilot study20 that found a Cox Menstrual Symptom Scale (CMSS) mean value of 1.62 for PD patients after moxibustion. We expected to obtain mean CMSS values of 1.7, 1.9, and 2.5 for the pre-menstrual treatment group (Group A), menstrual-onset treatment group (Group B), and waiting-list group (Group C). With the statistical power at 0.90 and the total significance level at 0.05, the sample size of each group needed to be 64 (192 in total) (NCSS-PASS, 11th edition, USA; Statistical Solutions). Estimating a dropout rate of 15%, 222 patients were registered. Each group contained 74 subjects.

Randomization and Blinding

Eligible participants were randomly allocated to Group A, Group B, and Group C. Patient serial numbers were generated using SAS software (Version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and sealed in light-proof craft envelopes by an independent observer. Only participants in Group C were informed of their allocation; the other two groups were not informed of their allocation. The therapists, outcome assessors, data managers, and statisticians worked independently and had little contact.

Interventions

The points Sanyinjiao (SP6) and Guanyuan (RN4) were selected for mild moxibustion (Supplementary Figure 1). 21 One end of the moxa stick was lit (herbal preparation of Artemisia vulgaris, Z32021062, Oriental Moxa Co., Suzhou, China) and then held 2–3 cm above each point for 10 minutes by an operator to create a local thermal sensation. The moxa was retained until the skin turned red, without any burning pain. The creation of a “Deqi” sensation (a warm and soothing sensation) was essential during and after the operation. Moxibustion was performed once a day for a total of 30 minutes. Three continuous courses of moxibustion of 5–7 days each were conducted at three continuous stage cycles.

All patients allocated to Groups A and B received the same intervention but at different time points. Patients in Group A received one course of treatment that lasted for 5–7 days before the onset of menstruation. Patients in Group B received the same type and course of treatment from the beginning to the end of each menstrual period. Group C was a waiting-list group and did not receive moxibustion or any other heat-related intervention (eg heat packs) during the trial (Supplementary Figure 2).

All participants were allowed to take prescribed NSAIDs in case of severe pain (measured by the VAS pain intensity score). No other forms of therapy were permitted.

All procedures were carried out by acupuncturists who were Chinese medicine practitioners and who had completed pre-training in using a standard operating procedure. The chief acupuncturist regularly observed their techniques to ensure consistency among practitioners.

Measurement

All patients were asked to complete a PD diary to record all details of their dysmenorrhea.

The primary outcomes were pain severity and pain duration, measured by the CMSS.22 This scale comprises 17 items assessing dysmenorrhea symptoms. Pain duration and severity are scored separately for each item. For the duration evaluation, each symptom is scored on a five-point scale: 0 = the symptom did not occur; 1 = the symptom lasted less than 3 hours; 2 = the symptom lasted 3–7 hours; 3 = the symptom lasted an entire day; and 4 = the symptom lasted several days. CMSS scores were recorded at the end of each menstrual cycle in the baseline stage, treatment stage, and follow-up stage, for a total of nine times. The average of the values for the three baseline stage cycles constituted the baseline data.

The secondary outcomes were VAS pain intensity score,23 self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) score,24 and self-rating depression scale (SDS) score.25 Participants were required to note their VAS scores at each menstrual cycle during baseline, treatment, and follow-up stages (a total of seven values). SAS and SDS scores were recorded only on the day of allocation and the first menstrual cycle in the follow-up stage (a total of two sets of values).

All scales used in this study were self-rating scales, which allowed patients to record their symptoms according to their subjective feelings and experiences.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were described on the intention-to-treat principle (n = 208). All continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data, and median (Q1–Q3) for skewed distributions. Categorical variables were presented as count (percentage). All statistical tests were double-sided, with P≤0.05 indicating statistical significance. The chi-squared test and non-parametric test were used to compare the within-group demographic characteristics at baseline. Furthermore, for every interesting indicator, the between-group difference was tested at each menstrual cycle stage time point from the first month to the sixth month after baseline; the changes from baseline were also estimated. The intragroup difference was also tested using least squares estimation in a general linear model. Within each model, indicators that were not balanced at baseline were adjusted. In addition, the Bonferroni adjustment was applied to the results of pairwise comparisons of intragroup differences. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS statistical software, Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participant Flow and Recruitment

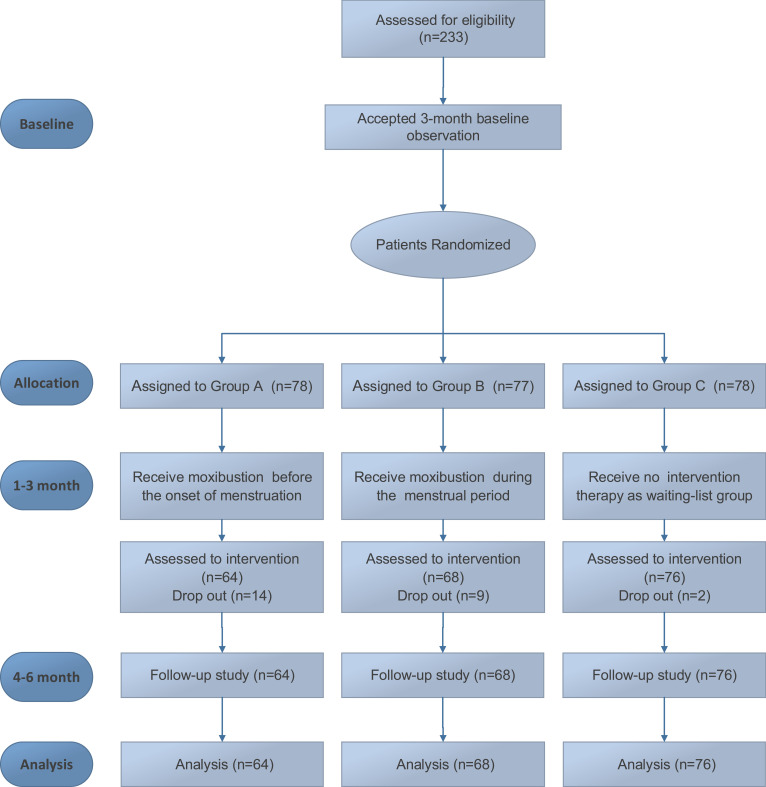

At baseline, 233 participants were randomly assigned to Group A (n = 78), Group B (n = 77), and Group C (n = 78). During the treatment stage, 14 participants in Group A (14 of 64), 9 in Group B (9 of 68), and 2 in Group C (2 of 76) withdrew. Of these, 18 people did not have enough time to receive treatment owing to work, and 7 could not get used to the smell of the moxa. Even though the dropout rate in group A was 21.9%, there was no significant difference in demographic characteristics between the dropped out and included subjects. A total of 208 participants (89.3%) with no further dropouts completed the 3-month treatment and were retained until the end of the follow-up stage. No participants took painkillers. Figure 1 shows the participant flow diagram. Table 1 shows patient characteristics at baseline for the three groups.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants in Three Groups

| Characteristics | Group A (N=64) |

Group B (N=68) |

Group C (N=76) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1-Q3), y | 20.00 (19.00, 22.00) | 20.00 (19.00, 21.00) | 20.00 (19.00, 22.00) |

| Course of PD, median (Q1-Q3), y | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | 4.50 (3.00, 6.00) | 4.50 (3.00, 5.00) |

| Dysmenorrhea days, median (Q1-Q3), y | 2.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 2.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 1.50 (1.00, 2.00) |

| Height, mean±SD, cm | 160.33 ± 4.36 | 160.74 ± 4.17 | 160.08 ± 4.22 |

| Weight, median (Q1-Q3), kg | 50.00 (47.00, 52.50) | 50.00 (47.00, 51.50) | 50.00 (48.00, 52.00) |

| BMI, median (Q1-Q3), kg/m2 | 19.53 (18.74, 20.82) | 19.26 (18.37, 20.12) | 19.53 (18.81, 20.31) |

| Temperature, median (Q1-Q3), °C | 36.40 (36.30, 36.50) | 36.40 (36.30, 36.50) | 36.45 (36.30, 36.50) |

| Pulse, mean±SD, bpm | 76.41 ± 3.23 | 76.41 ± 3.51 | 75.80 ± 3.78 |

| Breathe, median (Q1-Q3), bpm | 19.50 (19.00, 20.00) | 19.00 (18.00, 20.00) | 19.00 (18.00, 20.00) |

| Blood pressure, median (Q1-Q3), mmHg | |||

| Systolic pressure | 108.50 (106.00, 110.00) | 108.00 (106.00, 110.00) | 108.00 (105.00, 110.00) |

| Diastolic pressure | 70.00 (68.00, 75.00) | 72.00 (70.00, 75.00) | 70.00 (69.00, 75.00) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Primary Outcome

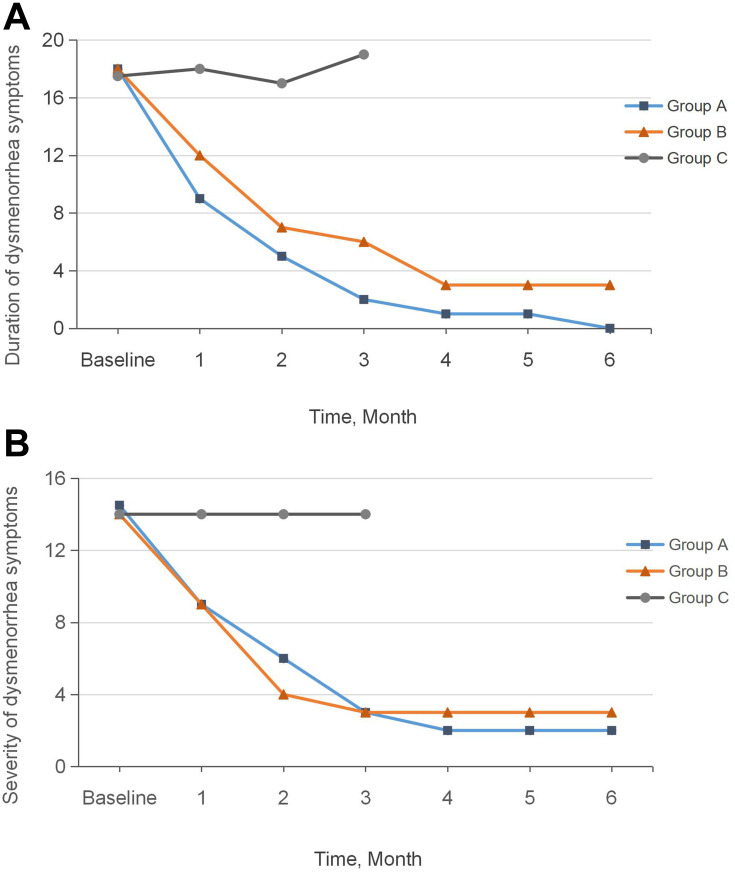

The CMSS score consisted of two scores: period pain severity and duration. Statistical analysis indicated no significant difference in CMSS score between the three groups at baseline (P>0.05) (Table 2). Figure 2 shows a downward trend in pain duration (Figure 2A) and severity (Figure 2B) in Group A and Group B over the six menstrual cycles after group allocation.

Table 2.

Primary Outcome Characteristics and Changes from Baseline Between and Within Groups

| Outcomes | Group A | Group B | Group C | Value of Pairwise Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=64) | (N=68) | (N=76) | Group A vs Group B | Group A vs Group C | Group B vs Group C | ||||

| Difference (95% Cl)a | Pb | Difference (95% Cl)a | Pb | Difference (95% Cl)a | Pb | ||||

| Duration rating of CMSS, meridian (Q1-Q3) | |||||||||

| 0 month | 18.00 (15.00, 20.00) | 18.00 (15.00, 20.00) | 17.50 (12.00, 23.00) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 month | 9.00 (6.50, 11.00) | 12.00 (9.00, 16.00) | 18.00 (13.00, 22.00) | −3.17 (−4.39, −1.96) | <0.001 | −8.28 (−9.52, −7.03) | <0.001 | −5.11 (−6.25, −3.96) | <0.001 |

| 2 month | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | 7.00 (5.00, 10.00) | 17.00 (13.00, 21.00) | −2.64 (−4.30, −0.97) | <0.001 | −11.29 (−12.99, − 9.58) | <0.001 | −8.65 (−10.21, −7.08) | <0.001 |

| 3 month | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00) | 6.00 (3.00, 9.00) | 19.00 (12.00, 21.50) | −3.44 (−5.31, −1.57) | <0.001 | −13.80 (−15.71,−11.88) | <0.001 | −10.36 (−12.11, −8.60) | <0.001 |

| 4 month | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 6.00) | – | −2.43 (−4.28, −0.59) | 0.010 | – | – | – | – |

| 5 month | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 6.00) | – | −2.43 (−4.31, −0.55) | 0.012 | – | – | – | – |

| 6 month | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 5.00) | – | −2.36 (−4.19, −0.52) | 0.012 | – | – | – | – |

| Severity rating of CMSS, meridian (Q1-Q3) | |||||||||

| 0 month | 14.50 (12.00, 17.00) | 14.00 (12.00, 17.00) | 14.00 (10.00, 18.50) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 month | 9.00 (8.00, 11.00) | 9.00 (7.00, 11.00) | 14.00 (11.00, 17.50) | 0.22 (−0.92, 1.35) | 1.000 | −5.02 (−6.17, −3.87) | <0.001 | −5.24 (−6.27, −4.20) | <0.001 |

| 2 month | 6.00 (4.00, 7.50) | 4.00 (3.00, 6.50) | 14.00 (11.00, 17.50) | 1.16 (−0.36, 2.67) | 0.203 | −7.80 (−9.35, −6.26) | <0.001 | −8.96 (−10.35, −7.57) | <0.001 |

| 3 month | 3.00 (2.50, 4.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 6.00) | 14.00 (11.50, 18.00) | −0.40 (−2.13, 1.33) | 1.000 | −10.72 (−12.47, −8.96) | <0.001 | −10.31 (−11.89, −8.73) | <0.001 |

| 4 month | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 5.00) | – | −0.82 (−2.34, 0.70) | 0.287 | – | – | – | – |

| 5 month | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 5.50) | – | −1.10 (−2.68, 0.47) | 0.168 | – | – | – | – |

| 6 month | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00) | 3.00 (1.50, 5.50) | – | −1.40 (−2.94, 0.14) | 0.074 | – | – | – | – |

Notes: aLeast squared mean adjusted for duration of dysmenorrhea symptoms and severity of dysmenorrhea symptoms at baseline between and within groups (Bonferroni adjusted). bMultiple comparison results adjusted using the Bonferroni correction.

Figure 2.

Pain Duration and Severity (CMSS Score) Over Time. (A) Change in duration at intervention time points; (B) Change of severity at intervention time points.

Pain duration in the 3-month treatment stage differed significantly between the three groups (P<0.001); the scores were significantly higher in Group C than in Groups A and B (P<0.001). Group A achieved a more significant reduction in pain duration than Group B (P<0.001). There were no significant differences in pain severity between Groups A and B (P>0.05) during the treatment stage; however, these groups achieved significant reductions compared with Group C (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Secondary Outcomes

Changes in VAS Score

The intragroup comparison showed that the post-treatment VAS score of pain intensity significantly decreased from baseline in Groups A and B (P<0.001); however, there were no changes in Group C throughout the trial (P>0.05). Interestingly, only one significant difference was observed between Group A and Group B at the third menstrual cycle of the treatment stage (P<0.001), but no significant difference was observed in the other two treatment stage menstrual cycles (P>0.05). The lack of an intergroup difference between A and B was also observed during the follow-up stage. Both Groups A and B differed significantly from Group C in all VAS score changes (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics and Changes in Secondary Outcomes from Baseline and Multiple Comparisons

| Outcomes | (N=64) | (N=68) | (N=76) | Value of Pairwise Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group A vs Group B | Group A vs Group C | Group B vs Group C | ||||

| Difference (95% Cl)a | Pb | Difference (95% Cl)a | Pb | Difference (95% Cl)a | Pb | ||||

| Pain intensity rating of VAS, meridian (Q1-Q3) | |||||||||

| 0 month | 6.00 (5.00, 7.00) | 6.00 (5.00, 7.00) | 5.00 (4.00, 7.00) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 month | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 4.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 5.00 (4.00, 6.50) | 0.06 (−0.32, 0.44) | 1.000 | −1.63 (−2.01, −1.24) | <0.001 | −1.69 (−2.04, −1.33) | <0.001 |

| 2 month | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 5.50 (4.00, 7.00) | −0.07 (−0.60, 0.46) | 1.000 | −3.01 (−3.54, −2.48) | <0.001 | −2.94 (−3.43, −2.45) | <0.001 |

| 3 month | 0.50 (0.00, 1.00) | 2.00 (0.00, 3.00) | 6.00 (4.00, 7.00) | −1.01 (−1.68, −0.34) | 0.001 | −4.75 (−5.43, −4.08) | <0.001 | −3.75 (−4.37, −3.12) | <0.001 |

| 4 month | 0.50 (0.00, 1.00) | 2.00 (0.00, 3.00) | – | −0.85 (−1.49, −0.21) | 0.010 | – | – | – | – |

| 5 month | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 3.00) | – | −0.85 (−1.51, −0.20) | 0.011 | – | – | – | – |

| 6 month | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 3.00) | – | −0.96 (−1.64, −0.27) | 0.007 | – | – | – | – |

| Anxiety measured by SAS, meridian (Q1-Q3) | |||||||||

| 0 month | 50.00 (40.00, 52.50) | 50.00 (39.38, 53.75) | 41.25 (33.75, 52.50) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 month | 37.50 (32.50, 40.00) | 38.75 (35.00, 41.25) | 43.75 (36.88, 52.50) | −0.05 (−2.27, 2.16) | 1.000 | −9.88 (−12.08, −7.67) | <0.001 | −9.82 (−11.87, −7.77) | <0.001 |

| Depression measured by SDS, meridian (Q1-Q3) | |||||||||

| 0 month | 50.00 (41.38, 55.63) | 50.00 (42.50, 54.38) | 50.00 (41.38, 55.63) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 month | 38.75 (33.75, 41.25) | 39.38 (35.00, 43.75) | 38.75 (33.75, 41.25) | −0.98 (−3.26, 1.30) | 0.908 | −8.86 (−11.12, −6.59) | <0.001 | −7.88 (−9.99, −5.77) | <0.001 |

Notes: aLeast squared mean adjusted for VAS score, depression score, anxiety score at baseline between and within groups (Bonferroni adjusted). bMultiple comparisons adjusted using the Bonferroni correction.

Changes in SAS and SDS Scores

Intragroup comparisons for Groups A and B showed significant improvements from baseline in the anxiety and depression data (P<0.001), and the effect was greater than in Group C (P<0.001). Conversely, there was no difference between Groups A and B throughout the study period in either SAS scores (−0.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] −2.27 to 2.16, P = 1.000) or SDS scores (−0.98, 95% [CI] −3.26 to 1.30, P = 0.908) (Table 3).

Safety

Only one moxibustion-related adverse reaction was reported, for one participant in Group A. The reaction was a result of overly long moxibustion on both acupoints. The patient recovered completely in 2 days and continued the trial.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the effect of moxibustion on PD patients at different intervention times in a 9-month time frame. The results indicated that pre-menstrual moxibustion is superior to moxibustion during menstruation for all aspects of PD-related symptoms. Compared with no treatment, both groups that received moxibustion showed improvements in pain relief and emotional disorders. These benefits were retained for a reasonable length of time until the end of the follow-up stage, despite the termination of the moxibustion at the end of the treatment stage. Moxibustion seems to have a favorable safety profile, no severe adverse reactions, and a good follow-up effect.

PD is a common gynecologic disease closely related to changes in hormonal secretions during the menstrual cycle. The increase in PGs with menstruation is regarded as the main pathogenesis of PD; the peak stage of PD is 48 hours prior to menstruation.1 The PG upsurge close to the onset of endometrial expulsion triggers increased uterine tone, which causes the contractions that lead to period pain.26–28 Many clinical trials have examined the effect of acupuncture and moxibustion intervention time.29–31 In accordance with the pathological changes of PD, moxibustion interventions are usually applied in the pre-menstrual stage and at the onset of menstruation.

Previous studies indicate that pre-menstrual acupuncture treatment has a substantially greater effect on PD than treatment at menstruation onset.20,32,33 The strong effect of temporal influences on therapeutic outcomes of PD has also been extensively recorded in many ancient traditional Chinese medicine classical texts. The basis of this effect is the concept of “preventive treatment before disease,” which was first mentioned in The Inner Canon of Huangdi. Although acupuncture and moxibustion are different therapeutic mechanisms (mechanical stimulation vs thermal effect), there is evidence from animal experiments and clinical trials of the effect of moxibustion. Pre-menstrual moxibustion has shown better results for reducing uterine tone and contractions than menstrual-onset moxibustion in terms of its analgesic effect.34,35 One study on PD patients reported uterine microcirculation enhancement by increasing blood velocity and reducing vascular resistance through mild moxibustion.36

Our findings are congruent with such previous results. CMSS scores for the duration and severity of PD sharply decreased, and the effect was more prolonged in the pre-menstrual group. This indicates that pre-menstrual moxibustion provides stronger, faster, and more reliable long-lasting pain relief than moxibustion at the onset of menstruation (Figure 2).

VAS scores for both interventional groups improved significantly from baseline; however, the only between-group difference was at the third menstrual cycle in the treatment stage. This is likely because VAS score is a subjective measure. From a pathologic perspective, VAS scores provide a less objective measure of pain relief compared with conventional indicators such as blood tests and biological imaging examinations. Compared with the no-treatment group, both moxibustion intervention groups showed significant improvements in all PD parameters, particularly in the psychological measures of SAS and SDS. These findings suggest that moxibustion is a reliable and safe treatment option with high patient compliance, and that it is psychologically soothing for women experiencing PD.

Limitations

The limitations of the trial are as follows. First, we used only subjective scales for pain evaluations, and did not include objective indicators such as hormone and neuroimaging tests. Additional studies are needed using such indicators to identify pathological changes at different intervention times. Second, the use of a standardized moxibustion prescription instead of a personalized treatment protocol may have led to performance bias. Third, all participants were university students, who show a high incidence of PD.37,38 The limited sample diversity may have resulted in selection bias, as the education level of participants and their parents may have influenced the results.39 Finally, although no participants took painkillers, the results may still be biased. Further subgroup analyses are needed.

Conclusion

Moxibustion for PD populations is safe, effective, has long-term effects, and has no serious side effects. Moxibustion prior to menstruation is superior to moxibustion during menstruation in its overall effects, and particularly on the duration of PD symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to all colleagues who joining and assisting in our study, acupuncture operators, and supporters of this study. Clinical data administration was performed by New Zealand Massey University Mathematics Institute Statistic Center. We thank Diane Williams, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Editing China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This trial was supported by grant 2012SZ0170 from the Sichuan Science and Technology Support Project.

Abbreviations

PD, primary dysmenorrhea; PGs, prostaglandins; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OCPs, oral contraceptive pills; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; CDUTCM, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; VAS, visual analog scale; CMSS, Cox Menstrual Symptom Scale; SAS, self-rating anxiety scale; SDS, self-rating depression scale.

Data Sharing Statement

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article. No further data will be shared.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Teaching Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in February 2014 (approval number: 2013KL-034) and published. Written informed consent was obtained for each participant in this trial. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(6):762–778. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haidari F, Akrami A, Sarhadi M, Shahi MM. Prevalence and severity of primary dysmenorrhea and its relation to anthropometric parameters. Hayat. 2011;17(1):70–77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagua T, Tkeshelashvili B, Gagua D. Primary dysmenorrhea: prevalence in adolescent population of Tbilisi, Georgia and risk factors. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2012;13(3):162–168. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2012.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett M, Lemyre M. No. 345-primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(7):585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hailemeskel S, Demissie A, Assefa N. Primary dysmenorrhea magnitude, associated risk factors, and its effect on academic performance: evidence from female university students in Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health. 2016;8:489–496. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S112768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Sanctis V, Soliman A, Bernasconi S, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents: prevalence, impact and recent knowledge. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2015;13(2):512–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KI, Nam HJ, Kim M, Lee J, Kim K. Effects of herbal medicine for dysmenorrhea treatment on accompanied acne vulgaris: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):318. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1813-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Choi TY, Myung CS, Lee MS. Herbal medicine Shaofu Zhuyu decoction for primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2016;5:9. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0185-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith CA, Armour M, Zhu X, Li X, Lu ZY, Song J. Acupuncture for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:Cd007854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghafourian M, Band N, Pour A, Kooti W, Foroutan-rad M, Badiee M. The role of CD16+, CD56+, NK (CD16+/CD56+) and B CD20+ cells in the outcome of pregnancy in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2015;3:61–66. doi: 10.15296/ijwhr.2015.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):428–441. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahradnik HP, Hanjalic-Beck A, Groth K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives for pain relief from dysmenorrhea: a review. Contraception. 2010;81(3):185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan O, Naziroglu M, Guney M, Aykur M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug modulates oxidative stress and calcium ion levels in the neutrophils of patients with primary dysmenorrhea. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;100(2):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manzoli L, De Vito C, Marzuillo C, Boccia A, Villari P. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2012;35(3):191–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiegratz I, Kuhl H. Long-cycle treatment with oral contraceptives. Drugs. 2004;64(21):2447–2462. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464210-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M, Chen X, Bo L, et al. Moxibustion for pain relief in patients with primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bo LN, Yang YK, Wu B, et al. [Moxibustion treatment of primary dysmenorrhea about involvement occasion research situation of domestic and foreign literature]. J Chengdu Univ TCM. 2013;36(4):115–121. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gou CQ, Gao J, Wu CX, et al. Moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea at different interventional times: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/6706901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu X, Bensoussan A, Zhu L, et al. Primary dysmenorrhoea: a comparative study on Australian and Chinese women. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma YX, Ye XN, Liu CZ, et al. A clinical trial of acupuncture about time-varying treatment and points selection in primary dysmenorrhea. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(2):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YN. [Discussion on acupoint selection of primary dysmenorrhea by moxibustion based on literature research]. J Liaoning Univ Trad Chin Med. 2011;13(7):141–142. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox DJ, Meyer RG. Behavioral treatment parameters with primary dysmenorrhea. J Behav Med. 1978;1(3):297–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00846681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. 1988;18:1007–1019. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700009934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zung WW, Richards CB, Short MJ. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic: further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13(6):508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060026004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fajrin I, Alam G, Usman AN. Prostaglandin level of primary dysmenorrhea pain sufferers. Enferm Clin. 2020;30(Suppl 2):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.07.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haidari F, Homayouni F, Helli B, Haghighizadeh MH, Farahmandpour F. Effect of chlorella supplementation on systematic symptoms and serum levels of prostaglandins, inflammatory and oxidative markers in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;229:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.08.578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD001751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen SZ, Cong Q, Zhang BF. [Preliminary comparison on the time-effect rule of pain-relieving in the treatment of moderate dysmenorrhea between acupuncture on single-point and acupuncture on multi-point]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2011;31(4):305–308. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin X, Lü X, Wei YH, Zhu SP, Chen H. [Effect of moxibustion pretreatment at different time on ovarian function in rats with dimini-shed ovarian reserve]. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2019;44(11):817–821. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, Zhu SS, Ruan JG, Wang YJ, Xu TS. [Clinical observation on time-effect of electroacupuncture for idiopathic facial paralysis]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2019;39(10):1059–1062. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao SH, Liu ZS. [A literature analysis of the timing, frequency and course of treatment of dysmenorrhea by acupuncture and moxibustion]. Hebei J TCM. 2012;34(1):115–117. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bu YQ. [Observation on therapeutic effect of acupuncture at Shiqizhui (Extra) for primary dysmenorrhea at different time]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2011;31(2):110–112. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang M. Effects of moxibustion at different intervention timing on dysmenorrhea intensity of uterine contraction and related mechanisms [Dissertation]. China: Beijing University of TCM; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu QQ. Effect of early moxibustion intervention on uterine microcirculation and PG receptor ratio in dysmenorrhea rats [dissertation]. China: Beijing University of TCM; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Q, Li X, Ren K, Yang S. [Effects of mild moxibustion on the uterine microcirculation in patients of primary dysmenorrhea]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2018;38(7):717–720.Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azagew AW, Kassie DG, Walle TA. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea, its intensity, impact and associated factors among female students’ at Gondar town preparatory school, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0873-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abu Helwa HA, Mitaeb AA, Al-Hamshri S, Sweileh WM. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and predictors of its pain intensity among Palestinian female university students. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0516-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parra-Fernandez ML, Onieva-Zafra MD, Abreu-Sanchez A, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Iglesias-Lopez MT, Fernandez-Martinez E. Management of primary dysmenorrhea among university students in the South of Spain and family influence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5570. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]