Abstract

Atg7 is an indispensable factor that plays a role in canonical nonselective autophagy. Here we show that genetic ablation of Atg7 in outer hair cells (OHCs) in mice caused stereocilium damage, somatic electromotility disturbances, and presynaptic ribbon degeneration over time, which led to the gradual wholesale loss of OHCs and subsequent early-onset profound hearing loss. Impaired autophagy disrupted OHC mitochondrial function and triggered the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria that would otherwise be eliminated in a timely manner. Atg7-independent autophagy/mitophagy processes could not compensate for Atg7 deficiency and failed to rescue the terminally differentiated, non-proliferating OHCs. Our results show that OHCs orchestrate intricate nonselective and selective autophagic/mitophagy pathways working in concert to maintain cellular homeostasis. Overall, our results demonstrate that Atg7-dependent autophagy plays a pivotal cytoprotective role in preserving OHCs and maintaining hearing function.

Subject terms: Macroautophagy, Cochlea

Introduction

Macroautophagy (henceforth referred as autophagy) is conserved in all eukaryotes that degrades damaged proteins, nucleic acids, and cellular organelles. Autophagy can be induced in response to physiological/pathological stimuli and helps to maintain cytosolic homeostasis1. To date, >30 autophagy-related genes (Atgs) have been identified2. Mammalian Atgs can be subdivided into six functional clusters, including the Atg5/Atg12 system and Atg8/light chain 3 (LC3) system, and within both these systems Atg7 plays a fundamental role. Atg7 adenylates Atg12 and Atg8/LC3 and forms a thioester intermediate with both and ultimately transfers them to Atg3 and Atg103,4.

In contrast to the embryonic lethality observed in Ambra1−/−, FIP200−/−, and beclin 1−/− mouse phenotypes, Atg7−/− mice, similar to Atg5−/−, Atg3−/−, Atg9−/−, and Atg16L1−/− knockouts, die within the neonatal period5. To investigate the roles of autophagy in mammals, Atg7 and Atg5 conditional knockout mice were created by the Cre-Loxp method6,7. A line of transgenic mice expressing the Cre recombinase were bred with Atg7flox/flox or Atg5flox/flox mice, and most of the homozygous mice exhibited pathological phenotypes5,8.

Cochlear hair cells (HCs) are postmitotic cells that rely on cellular homeostasis to maintain cell survival, but the role of autophagy in keeping cellular homeostasis in the mammalian inner ear is still poorly understood. Initial work on cochlear autophagy dates back 40 years to when Hinojosa observed autophagic vacuoles containing cell organelles in maturing cochlear cells during postnatal development and remodeling9. It was not until 2007, however, that this field sparked more intense research interest. Taylor et al. described the pattern of cochlear HC lesions in postnatal day (P) 18–P21 mice induced by coadmininstration of kanamycin and bumetanide10. Large numbers of outer hair cells (OHCs) died via an apoptotic pathway, but different modes of subsequent inner hair cell (IHC) death were indicated, including autophagy. In 2015, de Iriarte Rodríguez et al. analyzed the cochlear transcriptome of the mice11. At P270, as compared to embryonic day 18.5, LC3-II was increased while p62 was decreased, which indicated that the expression of autophagy-related genes is regulated throughout cochlear maturation and aging. Also in 2015, Yuan et al. studied autophagy in P90 adult mice subjected to a 2–20 kHz broadband 96/106 dB noise model and observed a temporary threshold shift at 96 dB and a permanent threshold shift at 106 dB. The LC3B level was elevated after 96 dB (but not 106 dB) noise exposure and promoted OHC survival12. The landmark study involving inner ear HC-specific autophagic gene conditional knockout mice was reported by Fujimoto et al. in 201713. In their work, Pou4f3CreAtg5flox/flox mice were generated by deletion of Atg5 specifically in HCs. The mutant mice had profound hearing loss. At P14, many stereocilia were destroyed in OHCs and IHCs, and the cell bodies of some OHCs were damaged, and at P60 nearly all OHCs were missing. However, the reason why OHCs were more vulnerable to deficient autophagy was not determined in their work.

In this study, we targeted OHC autophagy by taking advantage of OHC-specific Atg7 conditional knockout mice. We found that disruption of Atg7-dependent autophagy in OHCs resulted in stereocilium damage, somatic electromotility disturbances, and presynaptic ribbon degeneration, which eventually led to OHC loss and hearing impairment in mice. These results suggest that Atg7-dependent autophagy protects the health of OHCs, thus maintaining hearing function.

Materials and methods

Animals

Atg7flox/+ mice (Stock #D000534) and PrestinCre/+ mice (Stock #D000023) of both sexes were bought from Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University and used in the experiments. Atg7flox/+ mice were bred with Atg7flox/+ mice to get Atg7flox/flox mice, and Atg7flox/+ mice were bred with PrestinCre/+mice to get PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/+ mice. Atg7flox/flox mice were then crossed with PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/+ mice to produce PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice (with Atg7flox/flox mice as controls). Most of the experiments were done using mice at P30, P60, and P90. Mice were housed in pathogen-free facilities with controlled day–night cycles. All animal protocols were approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nanjing University and were in accordance with the National Institute of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Genotyping PCR

Genomic DNA from toes or tail tips were genotyped by adding 50 mM NaOH, incubating at 98 °C, and neutralizing with 1 M Tris-HCl (Solarbio, T1130). Primers were as follows: Atg7: (F) 5’-TGG CTG CTA CTT CTG CAA TGA TGC-3’; (R) 5’-CAG GAC AGA GAC CAT CAG CTC CAC-3’; wild type: (F) 5’-ATT GTG GCT CCT GCC CCA GT-3’; (R) 5’-CAG GAC AGA GAC CAT CAG CTC CAC-3’; Prestin: (F) 5’-ATT TGC CTG CAT TAC CGG TC-3’; (R) 5’-ATC AAC GTT TTC TTT TCG G-3’. PCR cycles were an initial denaturing step of 3 min at 94 °C, 38 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 58 °C, 30 s extension at 72 °C, and cooling at 4 °C.

Histological examination

Isolated cochleae were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then decalcified with 0.5 M EDTA (Solarbio, E1170). For cryosectioning, cochleae were immersed in increasing concentrations of 10–30% (w/v) sucrose (Biosharp, Amresco 0335) and then with serial mixtures of OCT (Sakura, Tissue-Tek 4583) and sucrose. The sections and whole mounts were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline blocking solution containing 5% donkey serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.02% sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich, S8032), and 0.5% Triton; incubated with diluted primary antibodies; and further with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488/555/647, Invitrogen). The primary antibodies were Atg7 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher, PA5-35203, 1:300); Myosin VIIa mouse polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher, PA1-936, 1:500); Prestin goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-22694, 1:200); CtBP2 mouse monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, 612044, 1:200); and P62 Guinea Pig polyclonal antibody (Progen, GP62-C, 1:200). The anti-fade Fluoromount-G mounting medium (SouthernBiotech, 0100-01) was used for mounting. The fluorescence images were obtained by a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. For hematoxylin staining, the whole mounts were stained with diluted hematoxylin (Solarbio, G1080) for 5 min.

Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

RNA of the cochlea and other organs was extracted using the Total RNA Extractor (Sangon Biotech, B511311) with a pellet pestle motor (DGS, G55500), transcribed by the ReverseAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher, K1622), and underwent RT-PCR. The concentration and purity were identified by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher, 2000). The primers were: Atg7: (F) 5’- ATG CCA GGA CAC CCT GTG AAC TTC-3’; (R) 5’- ACA TCA TTG CAG AAG TAG CAG CCA-3’; β-actin: (F) 5’- ACG GCC AGG TCA TCA CTA TTG-3’; (R) 5’-AGG GGC CGG ACT CAT CGT A-3’.

Western blot

Cochleae and other organs were dissected and transferred to the homogenizer tubes and mixed with RIPA lysis buffer (Fudebio, FD008) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11697498001). The supernatant from centrifuged homogenates was mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer (Beyotime, P0015L), boiled, electrophoresed, and blotted onto a 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Immobilon ISEQ00010). The primary antibodies were: Atg7 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher, PA5-35203, 1:500), Prestin goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-22694, 1:400), GAPDH mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam, ab9484, 1:1000), β-Actin rabbit IgG antibody (Abmart, P30002, 1:1000), LC3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (CST, 4108, 1:1000), and P62 Guinea Pig polyclonal antibody C-terminal specific (Progen, GP62-C, 1:500). The ECL Kit and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were used for detection. Images were obtained by GE ImageQuant LAS4000.

Auditory brainstem response (ABR) and distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs)

Mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized by 0.01 g/ml pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg). A TDT workstation (Tucker-Davis Technologies, System3) running SigGen32 software was used for ABR and DPOAE tests in a soundproof room. Broadband clicks and 4, 8, 16, 24, and 32 kHz tone pips were generated. The open-field ABR waveforms were recorded with needle electrodes at the vertex (active), the posterior bulla region of the ear (reference), and the nasal tip (ground). Auditory thresholds were identified by decreasing the sound intensity and distinguishing the ABR wave I. DPOAE testing was equipped with an ER-10B (Etymotic Research) and a probe. DPOAE was evoked by two simultaneously applied long-lasting constant-level pure tones (L1 = 65 dB SPL and L2 = 75 dB SPL) with a frequency ratio (F2/F1) of 1.2 given through earphones. DPOAE was recorded at 2F1 − F2 frequency and plotted as a function of the F2 frequency within the range of 1–32 kHz. DPOAE was considered present when at least it was 3 dB above the average noise floor.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Isolated cochleae were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Alfa Aesar, A17876). Cochlear whole mounts were fixed in 1% OsO4, dehydrated through graded ethanol, and desiccated by a CO2 critical-point dryer (Leica, EM CPD300). For SEM, samples were sputter-coated with gold (Cressington, 108) on stubs. A field-emission scanning electron microscope (FEI, Quanta250) was used to obtain images. For TEM, samples were further infiltrated in a graded series of propylene oxide (Macklin Biochemical, P816084) and gradually polymerized in araldite. Ultrathin sections were made by a Leica EM UC6 powertone, sequentially post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined by a Hitachi H-7650 transmission electron microscope.

Electrophysiology

Under a dissection microscope, the bony otic capsule of the isolated cochleae was removed using fine forceps in a 35-mm Petri dish with 3 ml Leibovitz L-15 medium (Thermo Fisher, 11415064) buffered with 10 mM HEPES to an osmolality of 300 mOsm (Gonotec, Osmomat 3000). After removing the stria vascularis, the whole mount was released from the modiolus, cut into three pieces, and transferred to 100 μl L-15 medium with diluted collagenase IV (Sigma, C5138) for 5 min. The enzymatic digestion solution was then replaced by enzyme-free L-15 medium. The OHCs of the middle turn were gently swept out using a superfine eyelash with a handle (Ted Pella, 113) and isolated. Borosilicate glass filaments (Sutter instruments, B150-86-10) were pulled by a Sutter P-2000 and then polished with a microforger (Narishige, MF380) to make 2–3 μm patch electrodes with an initial resistance around 3 MΩ. The OHC cell membrane nonlinear capacitance (NLC) was measured using a continuous two sine wave stimulus protocol superimposed onto a voltage ramp from −120 to +100 mV. The low-pass filtered currents were amplified by an Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments). The pClamp 10 software on a computer connected to a Digidata 1440A A/D converter (Axon Instruments) was used to acquire whole-cell currents and evoked responses. The data were obtained using the jClamp 32 software.

Statistical analysis

At least three independent experiments were performed for each experimental condition. Data were shown as mean ± S.E.M. Data were analyzed by the GraphPad Prism 6.02 software and two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t tests were used. Statistical results were labeled with */**/*** for p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively. Sample sizes were pre-determined by calculations derived from our experience. Animals were not randomly assigned during collection, but the data analysis was single masked. No sample was excluded from the analyses. The number of replicates was indicated in each figure legend.

Results

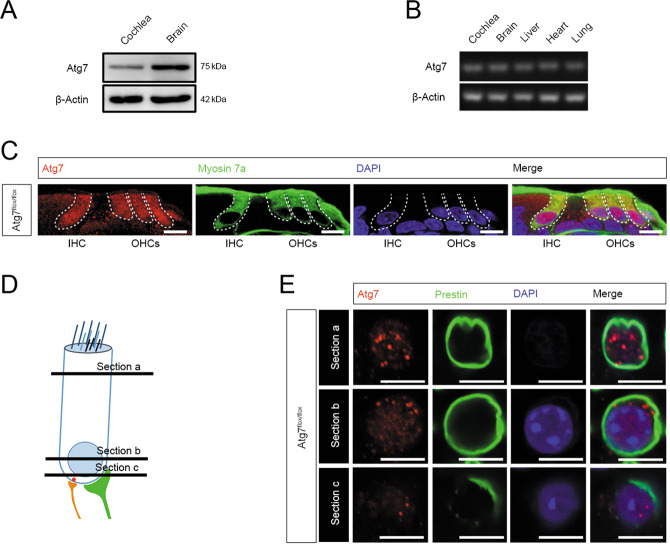

Atg7 is expressed in OHCs and IHCs

Western blot demonstrated that Atg7 was expressed in the cochlea and brain (Fig. 1A), and RT-PCR confirmed Atg7 mRNA expression in the cochlea (Fig. 1B). Immunostaining of cryosections showed that HCs had the highest expression level of Atg7 compared with supporting cells and other surrounding cells in the organ of Corti (Fig. 1C), and whole-mount immunostaining showed Atg7 puncta in the cell bodies of OHCs and IHCs (Fig. 1D, E, 2A).

Fig. 1. OHCs and IHCs expressed the highest levels of Atg7 in the cochlea.

A Representative immunoblot of Atg7 protein in the cochlea. B Expression of the Atg7 gene was analyzed by RT-PCR. C Atg7 was evident in OHCs and IHCs in the cochlear cryosections. D, E Atg7 puncta were distributed throughout the OHC cell bodies as indicated in the infracuticular, nuclear, and basal pool sections. N = 6 for each group (western blot: N = 3). Scale bar: A–C: 5 μm; D, E: 10 μm.

Generation of OHC-specific Atg7 conditional knockout mice

Atg7 was inactivated in OHCs by crossbreeding the Atg7flox/flox mice with PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/+ mice to obtain the PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mouse strain, and the Atg7flox/flox mice without Cre were used as controls. PCR amplification of fragments derived from wild-type and mutant alleles showed bands of 460 and 550 bp for Atg7 and 350 bp for PrestinCre/+. OHC-specific Atg7-deficient mice were born at Mendelian frequency, healthy and fertile, and did not show any overt phenotype compared to their Atg7flox/flox siblings.

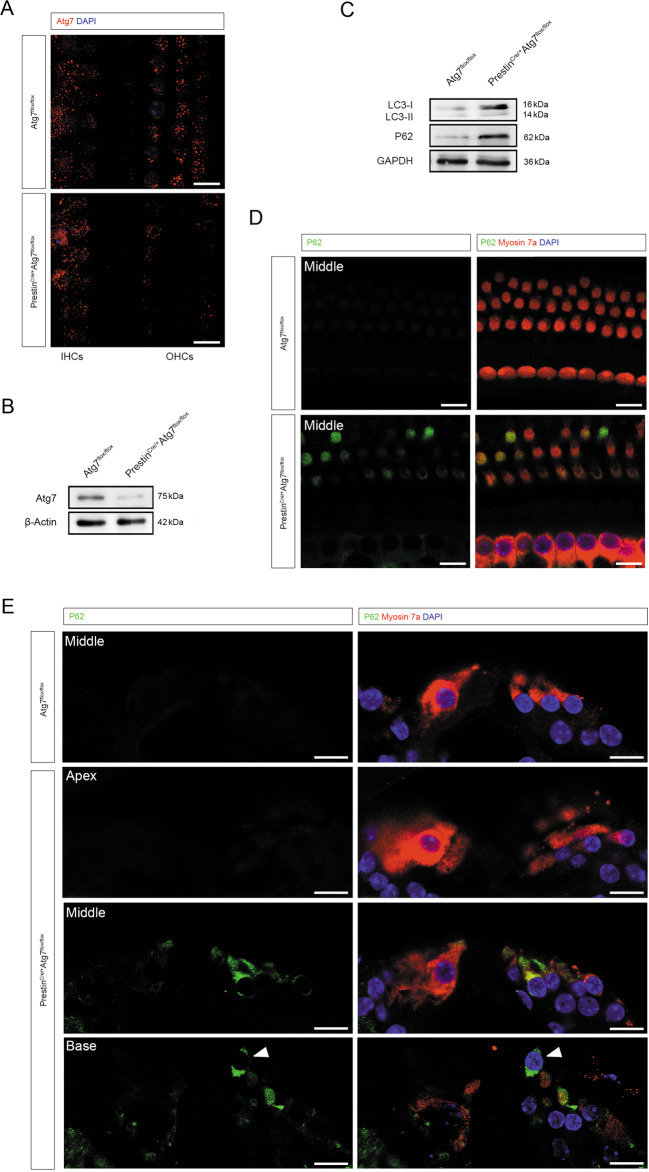

Aberrant autophagy in OHCs upon Atg7 deficiency

The Atg7 knockout efficiency was determined by immunostaining and western blotting and compared with the control OHCs from Atg7flox/flox mice at P30. Atg7 was largely suppressed in the OHCs of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice (Fig. 2A). Atg7 protein expression level in the cochlear whole mount (without spiral ganglion neurons) was dramatically reduced (Fig. 2B). Immunoblots of LC3 and P62 (SQSTM1) showed increased LC3-I, decreased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, and elevated P62, supporting autophagy deficiency in our model (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, immunostaining of the cochlear whole mount revealed that P62 accumulated in Atg7-deficient OHCs as early as P30 (Fig. 2D). In the cryosectioned samples at P30, we demonstrated that P62 aggregated in the cell bodies of the mutant OHCs, especially at middle and basal turns (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. Abnormal autophagy in Atg7-deficient OHCs.

A Representative immunostaining images showing efficient knockout of Atg7 in the OHCs and not in the IHCs. B Western blot showed that Atg7 was largely suppressed in the cochlear whole mount of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice. C Representative immunoblots showing elevated P62, increased LC3-I, and decreased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. D P62 accumulated in Atg7-deficient OHCs, showing a colorful mosaic pattern when co-stained with myosin 7a. E P62 aggregated in the mutant OHCs, especially at middle and basal turns. An OHC in the basal turn was extruded from the sensory epithelium (white arrowhead). N = 6 for each group (western blot: N = 3). Scale bar: 10 μm.

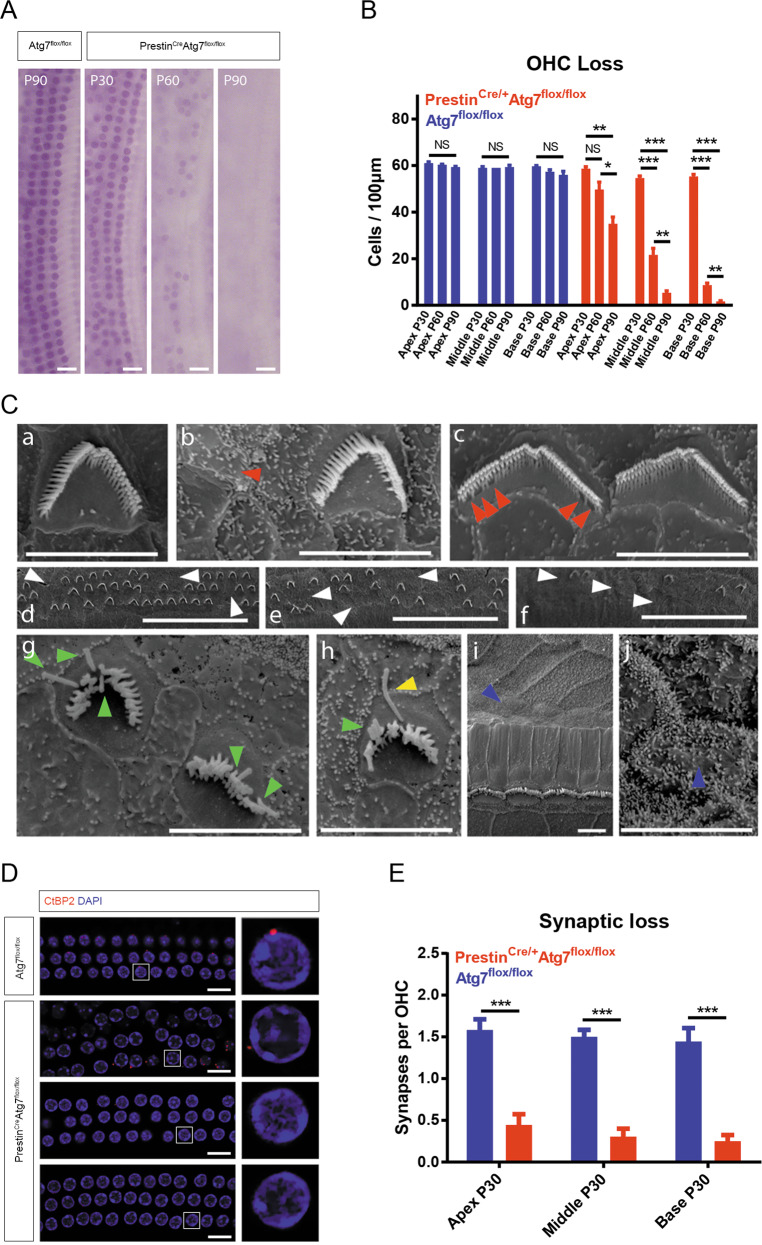

PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice have an abnormal morphological phenotype

Hematoxylin staining of cochlear whole mounts showed that PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice had occasional OHC loss at P30. OHCs were lost at an accelerated rate thereafter, with a gradient from the basal turn toward apical. At P60, the basal-turn OHCs were largely lost, while over half of the middle-turn OHCs also disappeared. At P90, all OHCs in the basal and middle turns were lost and just a few apical OHCs remained. However, in stark comparison, Atg7flox/flox mice had almost no OHC loss even at P90 (Fig. 3A, B). SEM showed a similar trend of base-to-apex OHC stereocilium loss in PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice (Fig. 3C). The stereocilium of the OHCs was progressively degenerated from P30 to P60. At P30, except for a few rare cells, Atg7-knockout OHCs presented a regular “V” or “W”-shaped staircase structure. At P60, however, the stereocilia became splayed or fused and portions of the hair bundles were lost (Fig. 3Cg). Some OHCs had completely pinched off their damaged hair bundles along with a bit of apical cytoplasm, resulting in a bundleless HC. Surprisingly, several surviving OHCs still possessed a single kinocilium (Fig. 3Ch). At P90, the OHCs exhibited extensive extrusion from the epithelium. In contrast, the stereocilium of OHCs from the control groups remained normal. There was also a significant loss of presynaptic ribbons in Atg7-deficient OHCs throughout the cochlea at P30. OHC afferent synapses were rendered visible by immunostaining for a component of the presynaptic CtBP2 protein. The average numbers of CtBP2 puncta per mutant OHC in the apical/middle/basal turns were 0.44 ± 0.13/0.31 ± 0.10/0.25 ± 0.07 versus 1.58 ± 0.13/1.50 ± 0.08/1.44 ± 0.16 in control OHCs, respectively, with all p values <0.001. Furthermore, OHC synaptic ribbons in the apical turn seemed more resistant to Atg7 deficiency than OHCs in the middle and basal turns (Fig. 3D, E). All of these forms of damage to the delicate OHC structures resulted in permanent loss of function.

Fig. 3. Morphological changes in PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice and controls.

A Representative hematoxylin staining images of the cochlear middle turn depicting the gradual loss of OHCs over time. B The average number of OHCs per 100 μm dropped by P30 and dramatically decreased at P60 and P90, especially in the basal turns. C SEM images from control mice (a) and Atg7-knockout mice (h–j). (b) A bundleless OHC (red arrowhead). (c) Stereocilia were missing from the inner row (red arrowheads), while the regular V/W-shaped staircase structure was maintained. (d–f) Three consecutive fields of an apical turn, within which part c was closer to the middle turn and part a was more apical. OHCs of all three rows randomly lost their hair bundles (white arrowheads). (g, h) At P60, the stereocilia were degenerated. Splayed stereocilia and persistent kinocilia were identified (green and yellow arrowheads, respectively). (i, j) The dead OHCs were replaced by supporting cells with microvilli (blue arrowheads). D, E Immunolabeling of CtBP2 (red channel) showed the loss of presynaptic ribbons of OHCs. Insets to the right represent typical OHCs with or without ribbons. Z-stack quantification of CtBP2 puncta per OHC showed significant differences between Atg7 knockouts and controls. N = 6 for each group. Scale bar: A: 20 μm; C(a–c, g–j): 5 μm; C(d–f): 50 μm; D: 10 μm.

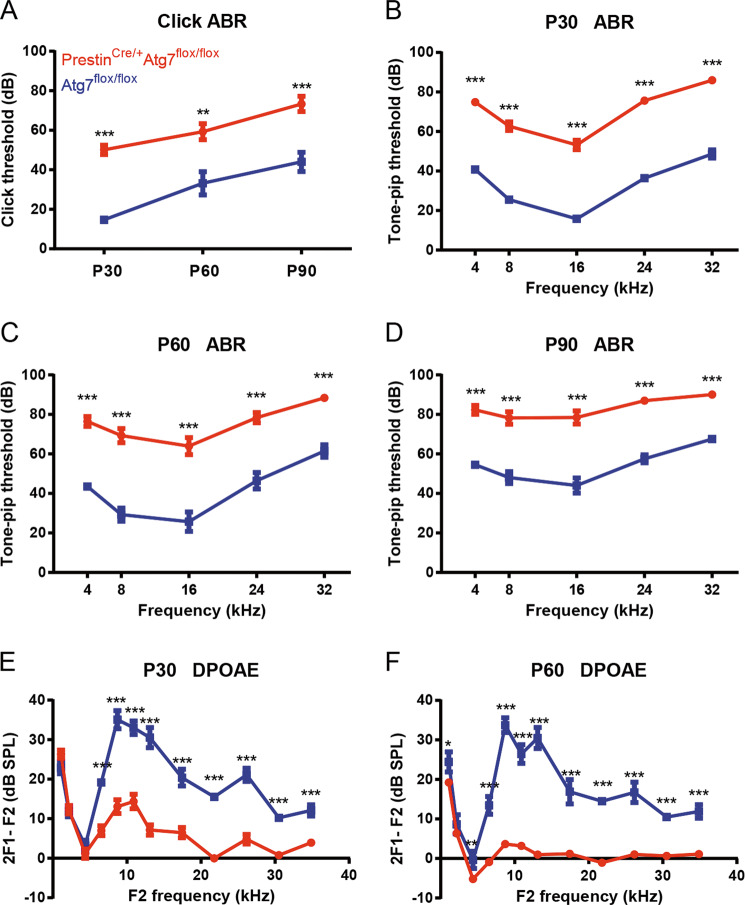

PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice have impaired hearing function

ABR click thresholds at P30, P60, and P90 showed that PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice suffered from accelerated hearing loss, and the control group had better hearing by >40 dB as early as P30 (Fig. 4A). ABR tone pip thresholds were measured at 4, 8, 16, 24, and 32 kHz. At P30, PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice lost their Preyer’s reflex, and their hearing thresholds across all frequencies were elevated by about 37 dB on average compared to the control group (Fig. 4B). At P60, the response thresholds of the PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice continued to increase, especially at 8 and 16 kHz, and the gap was about 34 dB on average (Fig. 4C). By P90, the PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice had developed severe hearing loss (Fig. 4D), and the hearing impairment seemed to propagate from high frequencies to low frequencies. DPOAE outputs were also assessed. At P30, DPOAEs were attenuated with closely packed peaks and troughs, and there was a significant difference from 6 to 32 kHz (Fig. 4E). At P60, PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice lacked detectable emissions at nearly all frequencies. Emissions at lower frequencies such as 4 kHz also showed statistically significant divergence compared with controls, which implied more apical involvement (Fig. 4F). Together, the ABR and DPOAE results suggested that all Atg7-deficient OHCs along the tonotopic map were affected; that mutant OHCs of higher frequencies were more vulnerable than those of middle and low frequencies; that at P30, despite generally normal morphology, many mutant OHCs had already lost most of their function; and that by P90 the majority of OHCs were degenerated and dead. These stark differences strongly suggest that Atg7 is required for OHC function and survival.

Fig. 4. Severe hearing loss in PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice.

A ABR click thresholds showed a 40-dB gap between two mice groups. B At P30, the hearing thresholds of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice were >70 dB on average. C At P60, the average ABR hearing thresholds of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice were elevated to >75 dB. D At P90, the ABR hearing thresholds were around 83 dB for the knockout mice. E, F DPOAE traces with 2F1 − F2 measured as a function of frequency F2. The strongest response was around 10 kHz at the F2 frequency for PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice. At P30, the DPOAE of the Atg7-deficient mice was suppressed at frequencies >6 kHz, with an overall average shift of >11 dB. At P60, the difference between the two groups approached 15 dB on average. DPOAE was almost absent at around ≥12 kHz. N = 12 for each group.

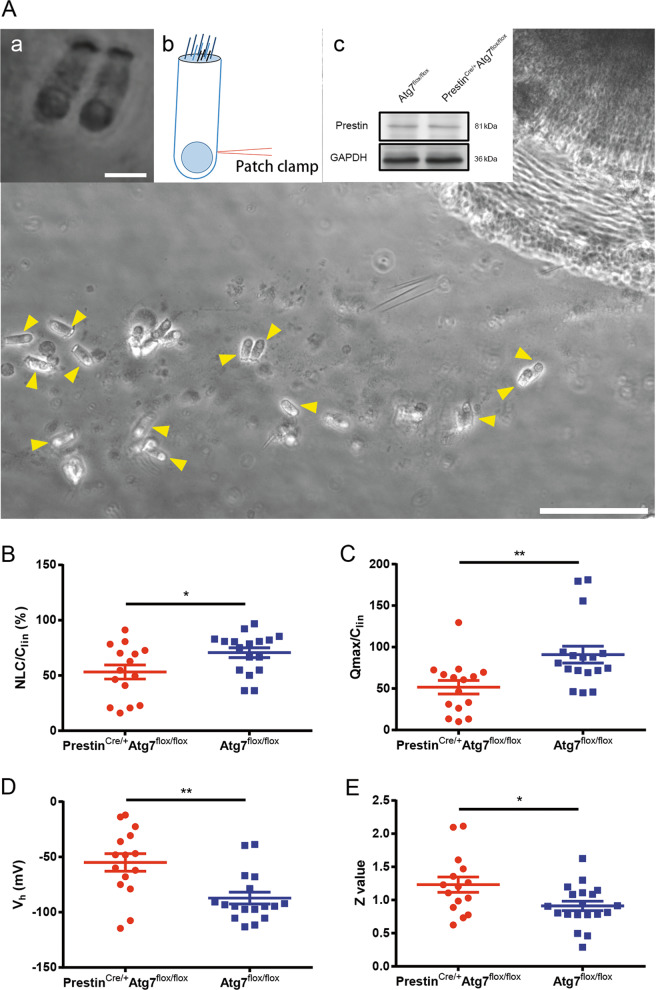

Atg7 deficiency disrupts OHC electromotility

OHCs are slender cylindrical cells with a cuticular surface, a rounded base, and a nucleus close to the lower end. We patched onto the OHC basolateral wall under the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration (Fig. 5A(a, b)) and recorded the voltage-dependent NLC, which is routinely used as a surrogate for electromotility. NLC traces of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox and Atg7flox/flox mice were recorded. The NLC capacitance data were fit to the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function as Cm = Qmaxɑ/{exp[ɑ(m – h)](1 + exp[−ɑ(m – h)])2} + Clin, where Cm is the NLC, Clin is the linear capacitance representing the membrane surface area, Qmax is the maximum voltage sensor charge moving through the membrane electric field and reflects the number of voltage-sensing proteins, Vh is the voltage at peak capacitance where the charge is distributed equally across the membrane, and ɑ is the slope factor describing the steepness of the voltage dependence (ɑ = ze/kT, where z is the apparent unitary charge movement or valence, e is the electron charge, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature). Vh and z define the voltage-operating range of the motor14.

Fig. 5. OHC electromotility was disturbed in PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice.

A OHCs were dissected from the whole-mount cochleae, and HCs were indicated by yellow arrowheads. OHCs were differentiated from IHCs based on their characteristic morphology and unique electromotility, and two of them are shown in a. b shows the position where the electrode was patched onto the OHC body. Western blot showed the prestin expression in PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice at P30 (c). B–E NLCs recorded were pooled and normalized to the corresponding Clin. Qmax, Clin, Vh, and z were obtained from a curve fit of the NLC response for each OHC, as shown by scatter plots of individual data and normalized mean values with standard errors. Significant differences for these parameters were seen between the two groups. Atg7-mutant OHCs: N = 15; the control OHCs: N = 17 (western blot: N = 3 for each group). Scale bar: A: 100 μm; a: 10 μm.

NLC and Qmax were normalized to Clin so as to be proportional to the varying plasma membrane area of OHCs. Four parameters (NLC/Clin, Vh, Qmax/Clin, and z) were analyzed. NLC/Clin showed statistically significant differences (53.15 ± 6.35% versus 70.67 ± 4.72%, p = 0.0283) between the two groups. Also, we found that the NLC/Clin of the Atg7-deficient OHCs exhibited a greater dynamic range than the control OHCs. Seven out of the 15 isolated Atg7-deficient OHCs had below average NLC/Clin values, with the lowest being only 16.10%, while 10 out of the 17 control OHCs had NLC/Clin values above the average and 12 of them had values close to the average (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that during voltage stimulation fewer prestin-associated gating charges were translocated. The Vh of the Atg7-deficient OHCs shifted toward more positive potentials compared to controls (−54.94 ± 7.93 versus −87.15 ± 5.72, p = 0.0018; Fig. 5C). A significant difference was found for Qmax/Clin between the two groups (51.61 ± 8.17 versus 90.97 ± 10.84, p = 0.0059; Fig. 5D). Interestingly, six OHCs had surprisingly low Qmax/Clin values (10.11 was the lowest), and a statistically significant divergence in the z-value of the two groups was seen (1.23 ± 0.12 versus 0.95 ± 0.07, p = 0.0194; Fig. 5E). Ten out of 15 Atg7-deficient OHCs had a z-value >1, including two OHCs whose value shifted to >2, which indicated the abnormally high voltage sensitivity of prestin. Although prestin expression was not changed in the knockout OHCs (Fig. 5Ac), the function of prestin was possibly changed due to autophagy ablation, which contributed to hearing impairment at P30.

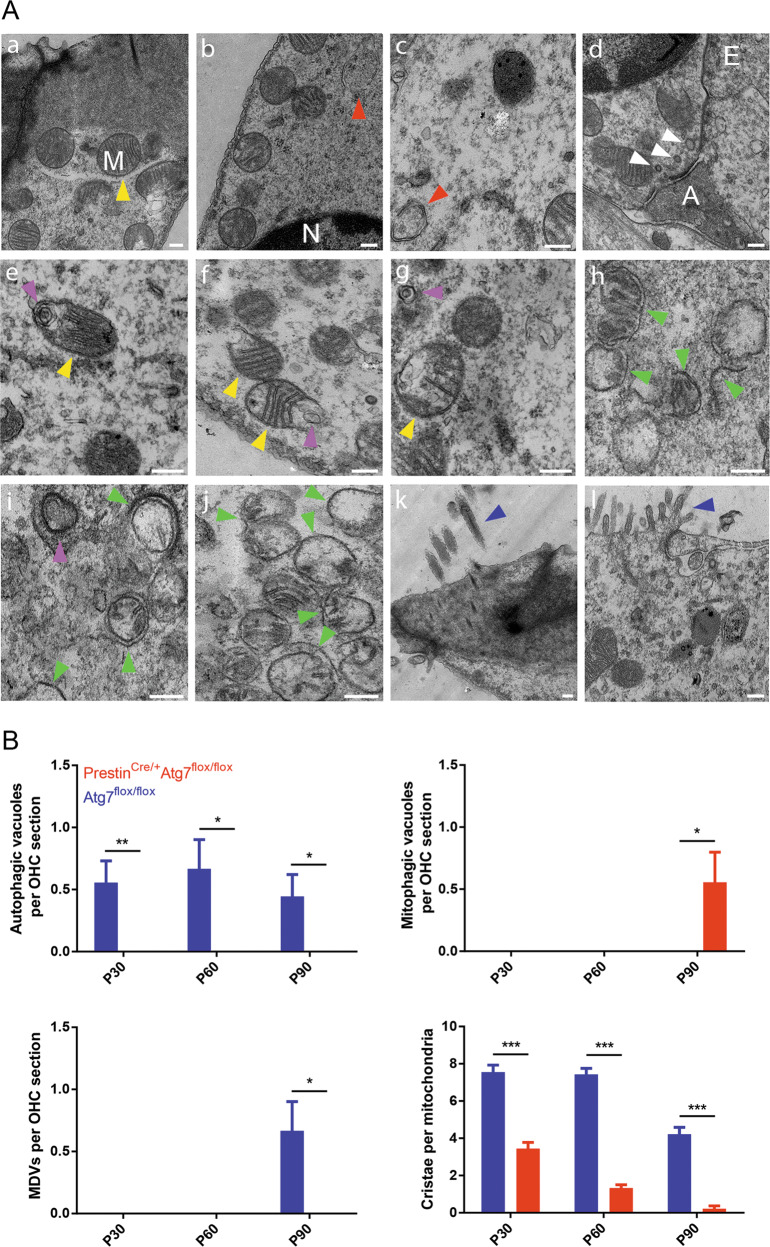

Loss of Atg7 in OHCs results in the accumulation of damaged mitochondria

OHC mitochondria are located in anatomically different regions, including the infracuticular and infranuclear regions and along the subsurface cisterns parallel to the lateral membrane where the metabolic demands require adequate energy turnover. The inner mitochondrial membrane locates the respiratory chain and ATP synthase complex15. We used TEM, the gold standard for gauging autophagy/mitophagy involvement, to corroborate OHC functional status. A bulk nonselective autophagic vacuole containing cytoplasm (but not organelles) was seen in the control OHCs but not in the knockout OHCs (Fig. 6A(b, c)), possibly due to the basal levels of autophagy. Control OHCs were richly endowed with mitochondria, and the architecture of the cristae could easily be deciphered. Mitochondria at various stages demonstrated their dynamic nature, necessitating a constant flux between degradation and replenishment (Fig. 6Aa). We were surprised to find mitochondria-derived vesicle (MDV) pathway involvement in control OHCs at P90 (Fig. 6A(e–g)), which had never been reported before. Strikingly, in OHCs of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice, the dismantling and degradation process seemed to start from the inner membrane instead of the outer membrane of defective mitochondria. From as early as P30, protruding mitochondrial cristae of mutant OHCs started to shorten, swell, deform, collapse, or disappear (Fig. 6A(h–j)), which indicated reduced inner membrane surface area together with low-density mitochondrial mass, thus suggesting mitochondrial malfunction16. OHC destruction proceeded more quickly at the high-frequency end, and the accumulation of these damaged mitochondria triggered self-repair via mitophagy in order to remove them. During mitophagy, entire mitochondria are sequestered and engulfed in mitophagosomes and delivered to lysosomes for degradation17. We found degenerated mitochondria enclosed within mitophagosomes (Fig. 6Ah) but no elongated subtypes that could be spared from autophagy/mitophagy. Also, intrinsic mitochondrial fusion and fission were not observed. Furthermore, the vast majority of the mitochondria were only partially enwrapped by the limiting membranes, which implied that the Atg7-dependent autophagy/mitophagy machinery was disrupted during the membrane elongation process and thus was inadequate for selectively eliminating damaged mitochondria. Statistically significant differences in autophagic/mitophagic vacuoles, MDVs, and cristae per OHC section were seen (Fig. 6B). This degeneration process was different from OHC apoptosis, which is characterized by cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, karyorrhexis, and apoptosome formation18. Massive mitochondria degeneration led to OHC degeneration, and the OHC corpses decomposed within the epithelium and the cellular debris was cleared (Fig. 6Al). Without coordinated mitochondrial biogenesis, a healthy respiring mitochondrial population inside the OHCs could no longer be maintained, resulting in the degeneration and ultimate demise of the OHCs.

Fig. 6. TEM micrographs of Atg7-deficient and control OHCs.

A (a) A control OHC at P30. An infracuticular mitochondrion with lamellar cristae (yellow arrowhead). The outer and inner membrane could not be distinguished under low magnification. (b, c) A control OHC at P60 and another at P90, respectively, showing a double-membrane bulk nonselective autophagic vacuole containing cytoplasm (red arrowhead). (d) A control OHC at P30. Three ribbons of different sizes (white arrowheads) were located against the afferent synapse. A afferent synapse, E efferent synapse. (e–g) A control OHC at P90. (e) An MDV formed inside an OHC (pink arrowhead); (f) two “membrane-broken” mitochondria (yellow arrowheads). (g) An expelled MDV (pink arrowhead) and a nearby “membrane-recovered” mitochondrion (yellow arrowhead). (h–j) A representative Atg7-knockout OHC with abnormal mitochondria. (h) Sequestering membranes partially encapsulated degenerated mitochondria. Note that there was a sequestering membrane with atypical reverse-bending ends (green arrowheads). The outer membrane of the mitochondria became shriveled and blurred. (i) A mitophagosome indicated the existence of Atg7-independent mitophagy. (j) Cristae largely disappeared, and the remaining cristae became disorganized. The aberrant mitochondria were no longer constrained to their preferred locations. (k) A control OHC at P90 with normal stereocilia (blue arrowhead). (l) A degenerated mutant OHC was replaced by adjacent supporting cells with microvilli (blue arrowhead). B Number of autophagic vacuoles/mitophagic vacuoles/MDVs per OHC section and cristae per mitochondria between the two groups had statistical differences. N = 5 for each group. Scale bar: A: 200 nm.

Discussion

Atg7 is essential for the physiological function of OHCs

Properly functioning OHCs, together with IHCs, assure high sensitivity, sufficient dynamic range, and fine-grained frequency tuning19,20. OHCs are especially endowed with three major transduction systems: (1) mechanoelectrical transduction in the hair bundles, (2) electromechanical transduction in the lateral wall, and (3) electrochemical transduction at the synapses in the cell base.

OHC hair bundles are coordinated arrays of stereocilia containing mechanoelectrical transducer (MET) channels. Around P7, the MET current in cochlear HCs reaches its maximum amplitude, with rapid activation kinetics and current adaptation along the entire cochlea. In a previous study, uptake of the fluorescent dye FM1-43 into autophagy-deficient OHCs was not affected at P5, suggesting that Atg5-knockout OHCs have functioning MET channels at least until P513. In the present study, Atg7-knockout OHCs occasionally lost some of their stereocilia at P30 as revealed by SEM, but considerable numbers of tip links and MET channels were still functional because DPOAE was not fully inhibited. This was consistent with a previous report that, at high SPL levels, the otherwise vulnerable DPOAE might be maintained due to the mechanical nonlinearity associated with stereociliary transduction (but not electromotility)21. However, at P60 the OHC stereocilia were aberrantly arranged or degenerated, with almost fully depressed DPOAE. The V/W-shaped staircase structure and planar cell polarization of the stereociliary bundles on top of each OHC depend on the oriented migration of the kinocilium. The kinocilium then regresses postnatally prior to the onset of hearing function at P1222. We found several surviving OHCs in the middle turn still bearing a single kinocilium at P60, which should be absent in adult mice. Taken together, our results in Atg7-deficienct OHCs suggest that autophagy is required to sustain regular stereocilium architecture and function and that autophagy is pivotal in kinocilium degeneration.

OHC somatic electromotility emerges at P7 in basal-turn OHCs, and at P12 almost all OHCs show motile responses. The response amplitude continues to increase until P13–P14, when mature amplitudes are reached, and this occurs prior to the development of fine tuning23,24. The reversible contraction (depolarization)/elongation (hyperpolarization) conformational change in response to the lateral membrane potential takes place thousands of times per second and is mediated by prestin (Slc26a5), and this forms the basis of mammalian cochlear amplification25–27. Because OHC somatic motility, but not hair bundle motility, is the basis of the cochlear amplifier, and because somatic motility is another major source contributing to DPOAE, we further sought to determine the OHC electromechanical transduction status upon Atg7 conditional knockout28. We evaluated the voltage-dependent charge movement by NLC as a suitable surrogate29. As early as P30, typical Atg7-deficient OHCs exhibited reduced NLC/Clin and Qmax/Clin, a Vh shifted toward a more positive potential, and an increased z-value. There was an obvious selection bias of the recordings because (1) the high dynamic range covered up the differences, (2) NLC was recorded in isolated OHCs instead of in situ, and (3) some OHCs failed to be patched and recorded due to dysfunctional membrane status, and thus many of them could have been knockouts. Thus it is possible that there was higher divergence between the two groups than what we have reported.

Another intriguing question was whether Atg7 ablation interfered with OHC synapses because autophagy has been reported to interact with synaptic plasticity, including structural changes in the synapse number, shape, size, and composition30,31. After P6, OHCs possess consolidated afferent synapses32. Synaptic ribbons of OHCs, although not at every afferent contact, release glutamate in order to weakly and sparsely depolarize unmyelinated type II afferents to convey input33. Summation of the excitatory postsynaptic potential from at least six OHCs is required to reach the threshold in type II afferents responding to high-intensity sounds34. Our imaging experiments showed that genetic ablation of Atg7 in OHCs provoked rapidly progressing synaptopathy. At P30, the average CtBP2 puncta per OHC was dramatically reduced, especially within the middle/basal turns. Irreversible loss of presynaptic ribbons preceded the loss of OHC cell bodies, and the lack of synaptic input could have contributed to the overall permanent ABR threshold elevation across frequencies. Type II afferents have been demonstrated to be strongly activated by exogenous ATP released from the supporting cells surrounding noise-damaged OHCs35–37; however, these afferents were hardly identified in the TEM sections of the knockouts. Together our data suggest that autophagy is indispensable for OHC synaptic signaling.

Atg7-dependent autophagy/mitophagy is required for OHC mitochondrial homeostasis and cannot be compensated for by other machineries

Bulk autophagy is a non-selective process of degradation of cellular constituents, while mitophagy specifically selects and removes mitochondria38,39. Mitochondria provide OHCs with energy production and metabolite synthesis and maintain Ca2+ homeostasis. Mitochondria produce cellular ATP via oxidative phosphorylation, supporting the high-energy demands of the cells. However, in the process of producing energy they produce toxic reactive oxygen species40. OHCs have evolved a repertoire of intricate quantity and quality control mechanisms to repair or repurpose damaged mitochondria, and selective quarantining and elimination of primed mitochondria through autophagy reduces the release of pro-apoptotic factors into the cytosol that might otherwise activate detrimental downstream pathways41. Alterations in mitochondrial function and dynamics can have a negative effect on OHC fitness.

Both in vitro and in vivo evidence supports an active role for autophagy in maintaining the proper action of cochlear HCs and the selective mitochondria clearance process of mitophagy functions in mitochondrial quality and quantity control, thus maintaining a healthy and contextually appropriate mitochondrial population in cochlear HCs42. Deficient autophagy/mitophagy can lead to imbalanced Ca2+ levels, reduced ATP supply, and subsequent bioenergetics failure43. Normal OHC function relies heavily on normal Ca2+ and ATP physiology44, and the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration regulates several fast events in OHCs, including the adaptation of MET channels and the release of neurotransmitters at the synapse. Massive numbers of damaged mitochondria inevitably disrupt Ca2+ balance and deprive the OHC of its ATP supply45–49. Although OHC electromotility does not rely on cellular stores of ATP or Ca2+ influx, the proteins involved in the maintenance of transmembrane ion gradients—such as Ca-ATPase, ATP-gated P2X channels, and many others—require an efficient ATP supply43,50–52.

The mitophagic machinery has been reported to execute in at least three distinct but interconnected signaling cascades: (1) the ubiquitin-dependent pathway, including foremost the Pink1-dependent Parkin-(in)dependent mitophagy pathway; (2) the receptor-mediated ubiquitin-independent pathway, including Nix, Bnip3, BCL2L13, Fundc1, FKBP8, and others; and (3) the MDV pathway53–56. The MDV pathway was specifically involved in aging OHCs, but in the OHCs of PrestinCre/+Atg7flox/flox mice nonselective autophagic vacuoles or MDVs were not found in the Atg7-deficient OHCs at P30, P60, or P90. Robust mitochondria no longer had regularly arranged mitochondrial cristae nor did they have abundant mitochondrial mass. They had moved from their original locations and accumulated, and some of them were partially enwrapped by the limiting membranes. An explanation for these sequestered membranous structures is that because Atg7 plays a fundamental role in the phagophore elongation process the autophagic/mitophagic vacuoles failed to form. Strikingly, there were infrequent mitophagic vacuoles in the degenerating Atg7-deficient OHCs, and these might represent alternative mitochondria digestion pathways (such as Rab9-dependent autophagy) that were induced to counteract mitochondrial deterioration in the absence of Atg7-dependent conventional autophagy/mitophagy machinery, or more likely, these occasional mitophagic vacuoles originated from canonical macroautophagy bypass, thus conferring mechanistic richness57–59. However, this compensatory effect was extraordinarily weak and was unable to rescue the OHCs.

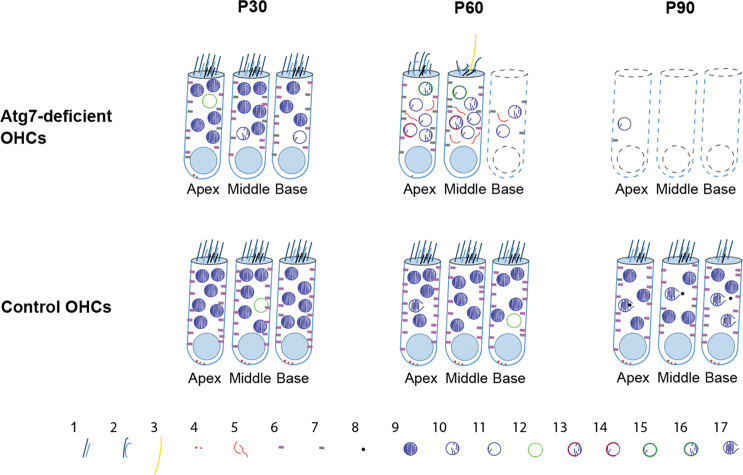

In summary, in the present study we show that disrupted autophagy/mitophagy hampered mitochondrial quality surveillance in OHCs leading to a profound hearing loss phenotype. A significant proportion of the defective mitochondria were only partially engulfed. The activation of Atg7-independent autophagy/mitophagy pathways was insufficient to prevent OHCs from physical deterioration, and susceptible OHCs were finally forced off the stage and ultimately undergo degradation. A schematic view of the phenotype of Atg7-knockout OHCs and the underlying mechanism is proposed in Fig. 7. Collectively, our observations strongly suggest the absolute requirement of Atg7-dependent autophagy/mitophagy for a fully functional mature OHC.

Fig. 7. Schematic view of the degeneration of Atg7-knockout OHCs.

The upper panel shows the accelerated degeneration of Atg7-deficient OHCs. The lower panel shows control OHCs. Symbols are numbered as follows: (1) stereocilia; (2) disarrayed stereocilia; (3) kinocilium; (4) presynaptic ribbons; (5) sequestering membranes; (6) functional prestin; (7) malfunctional prestin; (8) MDV; (9) mitochondria; (10 and 11) abnormal mitochondria; (12) autophagic vacuoles; (13 and 14) partially enwrapped mitochondria; (15 and 16) fully enwrapped mitochondria; (17) aging mitochondria.

Conclusion

The malfunction and degeneration of Atg7-deficient OHCs suggested a pronounced sensitivity to autophagy/mitophagy deficiency. Autophagy and mitophagy are highly active processes during inner ear development and maintenance, and these processes quickly dispose of damaged mitochondria. Our results show that the Atg7-dependent autophagy machinery plays a critical role in preserving OHC function and maintaining hearing ability. To what extent autophagy and mitophagy converge and coordinate the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and disposal to ensure OHC survival has yet to be fully elucidated in a broader context. Advanced fluorescent reporter systems, such as mito-Timer, mito-QC, mt-Keima, and, most recently, mito-SARI, will hopefully lead to a better understanding of mitophagy both in vitro and in vivo in future studies. In addition, future molecular and genetic studies should be fruitful in unraveling the mystery of the reciprocal interplay between the autophagy and mitophagy pathways in degenerating or injured OHCs and in exploiting for state-of-the-art OHC protection, telling stories of hope.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Minsheng Zhu (Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University) for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970884, 81771019, 81970885, 81970882, 82030029, 81700913), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (XDA16010303), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0103903), the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (BE2019711, BK20190121), the Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent of the Project of Invigorating Health Care through Science, Technology, and Education (QNRC2016002), and the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2018B030331001).

Author contributions

H.Z., X.Q., and X.G. conceived the study. J.T., R.C., and X.G. supervised the experimental design. H.Z., X.Q., N.X., S.Z., G.Z., Y.Z., D.L., C.C., X.Z., Y.L., and L.L. conducted the experiments. H.Z. and N.X. performed the statistical analysis. J.T., R.C., and X.G. supervised the interpretation of the data. H.Z. and X.Q. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript and approved for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by M. Hamasaki

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Han Zhou, Xiaoyun Qian

Contributor Information

Jie Tang, Email: jietang@smu.edu.cn.

Renjie Chai, Email: renjiec@seu.edu.cn.

Xia Gao, Email: xiagaogao@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Eskelinen EL. Autophagy: supporting cellular and organismal homeostasis by self-eating. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2019;111:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wesselborg S, Stork B. Autophagy signal transduction by ATG proteins: from hierarchies to networks. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:4721–4757. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2034-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KH, Lee MS. Autophagy-a key player in cellular and body metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014;10:322–337. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noda NN, Inagaki F. Mechanisms of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2015;44:101–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-034248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian development and differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:823–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komatsu M, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hara T, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong J. Atg7 in development and disease: panacea or Pandora’s Box? Protein Cell. 2015;6:722–734. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinojosa R. A note on development of Corti’s organ. Acta Otolaryngol. 1977;84:238–251. doi: 10.3109/00016487709123963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor RR, Nevill G, Forge A. Rapid hair cell loss: a mouse model for cochlear lesions. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2008;9:44–64. doi: 10.1007/s10162-007-0105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Iriarte Rodríguez R, Pulido S, Rodríguez-de la Rosa L, Magariños M, Varela-Nieto I. Age-regulated function of autophagy in the mouse inner ear. Hear Res. 2015;330:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan H, et al. Autophagy attenuates noise-induced hearing loss by reducing oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015;22:1308–1324. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto C, et al. Autophagy is essential for hearing in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2780. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos-Sacchi J. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:3096–3110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorn GW., 2nd Evolving concepts of mitochondrial dynamics. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019;81:1–17. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes LC, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial morphology in mitophagy and macroautophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitley BN, Engelhart EA, Hoppins S. Mitochondrial dynamics and their potential as a therapeutic target. Mitochondrion. 2019;49:269–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrashkin KA, et al. The fate of outer hair cells after acoustic or ototoxic insults. Hear Res. 2006;218:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcotti W. Functional assembly of mammalian cochlear hair cells. Exp. Physiol. 2012;97:438–451. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.059303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwander M, Kachar B, Müller U. The cell biology of hearing. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:9–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberman MC, Zuo J, Guinan JJ., Jr. Otoacoustic emissions without somatic motility: can stereocilia mechanics drive the mammalian cochlea? J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;116:1649–1655. doi: 10.1121/1.1775275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montcouquiol M, Kelley MW. Development and patterning of the cochlea: from convergent extension to planar polarity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020;10:a033266. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goutman JD, Elgoyhen AB, Gómez-Casati ME. Cochlear hair cells: the sound-sensing machines. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:3354–3361. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fettiplace R. Hair cell transduction, tuning, and synaptic transmission in the mammalian cochlea. Compr. Physiol. 2017;7:1197–1227. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashmore J, et al. The remarkable cochlear amplifier. Hear Res. 2010;266:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman MC, et al. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng J, et al. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 2000;405:149–155. doi: 10.1038/35012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellado Lagarde MM, Drexl M, Lukashkina VA, Lukashkin AN, Russell IJ. Outer hair cell somatic, not hair bundle, motility is the basis of the cochlear amplifier. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:746–748. doi: 10.1038/nn.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song L, Santos-Sacchi J. A walkthrough of nonlinear capacitance measurement of outer hair cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1427:501–512. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3615-1_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shehata M, Inokuchi K. Does autophagy work in synaptic plasticity and memory? Rev. Neurosci. 2014;25:543–557. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2014-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen W, Ganetzky B. Nibbling away at synaptic development. Autophagy. 2010;6:168–169. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiers FA, Nadol JB, Jr., Liberman MC. Reciprocal synapses between outer hair cells and their afferent terminals: evidence for a local neural network in the mammalian cochlea. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2008;9:477–489. doi: 10.1007/s10162-008-0135-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weisz CJ, Lehar M, Hiel H, Glowatzki E, Fuchs PA. Synaptic transfer from outer hair cells to type II afferent fibers in the rat cochlea. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:9528–9536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6194-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Monedero R, et al. GluA2-containing AMPA receptors distinguish ribbon-associated from ribbonless afferent contacts on rat cochlear hair cells. eNeuro. 2016;3:ENEURO.0078-16. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0078-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weisz C, Glowatzki E, Fuchs P. The postsynaptic function of type II cochlear afferents. Nature. 2009;461:1126–1129. doi: 10.1038/nature08487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Glowatzki E, Fuchs PA. Unmyelinated type II afferent neurons report cochlear damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:14723–14727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515228112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gale JE, Piazza V, Ciubotaru CD, Mammano F. A mechanism for sensing noise damage in the inner ear. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K, Klionsky DJ. Mitochondria removal by autophagy. Autophagy. 2011;7:297–300. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu S, Honda S, Arakawa S, Yamaguchi H. Alternative macroautophagy and mitophagy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;50:64–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R551–R560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Trojel-Hansen C, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and death. Circ. Res. 2012;111:1198–1207. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gustafsson ÅB, Dorn GW., 2nd Evolving and expanding the roles of mitophagy as a homeostatic and pathogenic process. Physiol. Rev. 2019;99:853–892. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.East DA, Campanella M. Ca2+ in quality control: an unresolved riddle critical to autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2013;9:1710–1719. doi: 10.4161/auto.25367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fettiplace R, Nam JH. Tonotopy in calcium homeostasis and vulnerability of cochlear hair cells. Hear Res. 2019;376:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceriani F, et al. Coordinated calcium signalling in cochlear sensory and non-sensory cells refines afferent innervation of outer hair cells. EMBO J. 2019;38:e99839. doi: 10.15252/embj.201899839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zenisek D, Matthews G. The role of mitochondria in presynaptic calcium handling at a ribbon synapse. Neuron. 2000;25:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80885-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dumont RA, et al. Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2a is the PMCA of hair bundles. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5066–5078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05066.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glowatzki E, Ruppersberg JP, Zenner HP, Rüsch A. Mechanically and ATP-induced currents of mouse outer hair cells are independent and differentially blocked by d-tubocurarine. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crouch JJ, Schulte BA. Expression of plasma membrane Ca-ATPase in the adult and developing gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 1995;92:112–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganitkevich VY. The role of mitochondria in cytoplasmic Ca2+ cycling. Exp. Physiol. 2003;88:91–97. doi: 10.1113/eph8802504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi A, Pizzo P, Filadi R. Calcium, mitochondria and cell metabolism: A functional triangle in bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019;1866:1068–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Housley GD, et al. Expression of the P2X(2) receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channel in the cochlea: implications for sound transduction and auditory neurotransmission. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:8377–8388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08377.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khaminets A, Behl C, Dikic I. Ubiquitin-dependent and independent signals in selective autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmermann M, Reichert AS. How to get rid of mitochondria: crosstalk and regulation of multiple mitophagy pathways. Biol. Chem. 2017;399:29–45. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2017-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemasters JJ. Variants of mitochondrial autophagy: Types 1 and 2 mitophagy and micromitophagy (Type 3) Redox Biol. 2014;2:749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugiura A, McLelland GL, Fon EA, McBride HM. A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control: mitochondrial-derived vesicles. EMBO J. 2014;33:2142–2156. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang CY, et al. Rab9-dependent autophagy is required for the IGF-IIR triggering mitophagy to eliminate damaged mitochondria. J. Cell Physiol. 2018;233:7080–7091. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen TN, et al. Atg8 family LC3/GABARAP proteins are crucial for autophagosome-lysosome fusion but not autophagosome formation during PINK1/Parkin mitophagy and starvation. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:857–874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuboyama K, et al. The ATG conjugation systems are important for degradation of the inner autophagosomal membrane. Science. 2016;354:1036–1041. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]