Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence is a serious and widespread problem worldwide. It is a domestic violence by a spouse or partner in an intimate relationship against the other spouse or partner. Even though Ethiopia is also one of the countries where the condition has been seriously happening, there is a dearth of information in the study area.

Objective

To assess the prevalence of intimate partner violence and its sociocultural practice, and its associated factors among married women in Oromia, Central Ethiopia.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted on 671 women of Ambo district who were in marriage from March 1 to 30, 2018. Multistage sampling method was employed to select study participants. Data were collected using interviewer-administered WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire. Descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analyses were done using SPSS version 20.0.

Results

Out of 671 married women expected to participate, 657 of them participated in the study making a response rate of 98%. Overall, 77% (95% CI 73.7–80.1%), and 62.4% (95% CI, 58.6–66.1%) of the respondents reported that they have experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetime and in the last one year, respectively. Lack of formal education by husband (AOR 2.30, 95% CI 1.28–4.15), housewife occupation of respondents (AOR 2.04, 95% CI 1.02–4.06), number of children (AOR 4.37, 95% CI 1.40–13.66), perceived husband dominance (AOR 1.74, 95% CI 1.15–2.63), grow up in domestic violence (AOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.00–2.35) and partner’s alcohol intake (AOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.12–2.79) were independently associated with intimate partner violence.

Conclusion

Intimate partner violence against women remains an important public health problem. This needs urgent attention at all levels of societal hierarchy including policymakers, stakeholders, and professionals to alleviate the situation.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, women, prevalence, associated factors

Background

Violence against women particularly, intimate partner violence is a major public health problem and a violation of women’s human rights worldwide. It is a phenomenon that persists all over the world which occurs in all settings and among all socioeconomic, religious, and cultural groups.1 Violence against women and girls continues to be a major challenge and a threat to women’s empowerment. Specifically Intimate Partner Violence results in exorbitant physical, emotional, and economic costs, and death is not an uncommon result.2 According to a literature review by National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, physical and numerous mental health consequences of Intimate partner violence include injury or death, chronic pain, gastrointestinal and gynecological problems, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and low self-esteem.3 Many women also suffer rape and violence during pregnancy, causing harm to both mothers and children.4

World Health Organization multicountry study on violence against women in ten different countries confirmed that the lifetime and current (past 12 months) prevalence of physical or sexual violence ranges between 15 and 71% and 4 to 54% respectively. According to the findings of the study, the lowest rates have been found in Japan and the highest in Ethiopia, Peru, and Bangladesh.5 More women in Africa are subject to lifetime partner violence (45.6%) than women anywhere in the world.6 In Kenya, the 2008/2009 demographic health survey report estimated that almost fifty percent of the women (47%) suffers from IPV in their lifetime.7 Thirty-four percent of ever-married women in Ethiopia has ever experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence by their current husband/partner and also twenty-seven percent of ever-married women experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the past 12 months, which is highest in Oromia followed by Harari region, Ethiopia.8

In the Ethiopian context, women represent 49.8% of the population and highly contribute to socioeconomic development, they occupy a lower status than men, they experience longer working days, low levels of education, and lack of adequate assignments in leadership and decision-making positions.9 However, studies from Ethiopia on intimate partner violence against women are fewer irrespective of different lifestyles, customs, and culture of the people and level of violence against women in these countries, there are no documented data about intimate partner violence including the study area. Further studies on associated factors of intimate violence are necessary to preview the challenges and to increase the performance of women in all activities. Thus, this study was conducted to determine the prevalence of intimate partner violence and its sociocultural practice among women and its associated factors in Ambo district, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted in Ambo district, West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Central Ethiopia from March, 1 to 30 2018. Ambo was found at 114 km far away from the capital city of Ethiopia - Addis Ababa in the west direction. Ambo district has thirty-three sub-districts having a total population of 137,806 (children <5 years are 22,642, and women of childbearing age 15–49 are 30,455).10

Study Design, Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

A community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted on married women. A household that had women who were in marriage during the study period was the sampling unit of the study. The sample size was calculated using unmatched case control of OpenEpi, with assumptions of power (chance of detecting) = 90%; confidence level = 95%; control to case ratio = 2:1; variable associated with IPV “Financial problem” was used to calculate sample size. Besides, percent of controls exposed (47.4%), percent of cases with exposure (52.6%)9 and adjusted odds ratio (AOR= 2.203) were considered and it gave a sample of 305. Since multistage sampling (the first sampling unit was, sub-district, the second sampling unit is the household with eligible target) was applied during the procedure, design effect of two was considered. Finally, a 10% non-response rate was taken and 671 samples were generated.

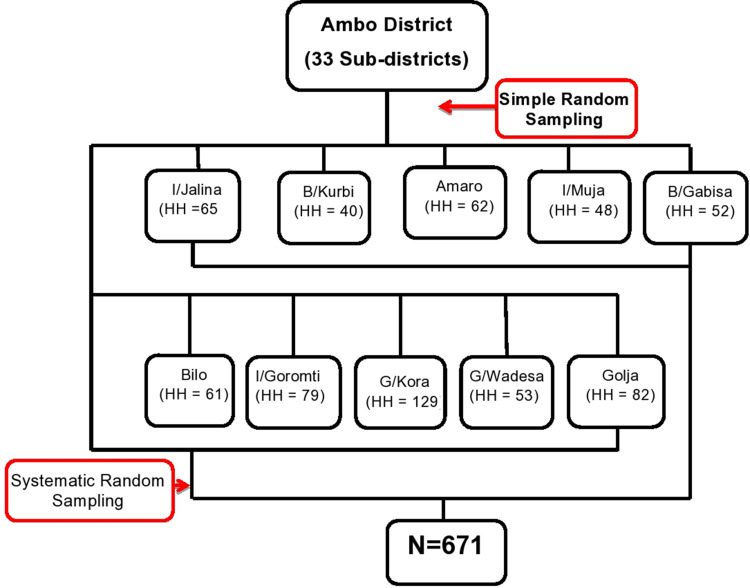

A multistage sampling technique was employed in the selection of study subjects. First, ten sub-districts were selected from the total thirty-three sub-districts of Ambo district through by a simple random sampling technique. Then study unit (household with eligible target) in each sub-district was selected using a systematic random sampling technique at an interval of twelve households. Proportional to population size allocation was used to allocate the sample size to each sub-district (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of sampling procedure for intimate partner violence and its associated factors among women in Ambo district, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, March, 2018.

Data Collection Tool

The data collection instrument was a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire that was adapted from the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire.11 The questionnaire consists of the sociodemographic data of the respondents and their husbands, factors influencing IPV and various types of IPV variables. The questionnaire was translated into the local language (Afan Oromo) by language experts and translated back to English by another person to ensure consistency.

Data Management and Analysis

Data quality was assured through pre-test on 5% of the total sample size in different sub-districts of the study area. Five female diploma nurses for data collection and two public health professionals were recruited for supervision. Data collectors and the supervisors were trained for one day by the investigator on the study instrument, consent form, how to interview, and data collection procedure. The investigator and the supervisors have checked the collected data for their completeness and corrective measures were made. The data collection process was closely supervised by supervisors and investigators.

For analysis, questionnaires were checked for completeness and entered into Epi data version 3.1 and SPSS version 20.0 was used for analysis. Descriptive analysis like frequency and percentage was carried out to describe sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents and their intimate partner violence and results were presented in texts, tables, and graphs. The bivariate and multivariate analyses were done using binary logistic regression to identify factors associated with IPV. Candidate variables for the final model (multivariate binary logistic regression) were identified using binary logistic regression model at p-value less than 0.25 and the final model multiple logistic regression was done to see the independent effect of each explanatory variable on the study variable at p-value of 0.05.

Terms and Operational Definitions

Physical violence: is the intentional use of physical force (shoving, choking, shaking, slapping, punching, burning, or use of a weapon) by an intimate partner in their lifetime; Sexual violence: when the intimate partner uses physical force to compel his wife to engage in a sexual act unwillingly, whether or not the act is completed, an attempted or completed sexual act and abusive sexual contact; Psychological/emotional violence: when the intimate partner traumatizes his wife by acts, threats of acts, or coercive tactics (humiliating his wife, controlling what his wife can and cannot do, withholding information, isolating his wife from friends and family, denying access to money or other basic resources); Intimate partner: is defined as current husband relation made by legal or based on the community cultural agreement; Intimate partner violence: when a woman experienced any of physical violence and/or sexual violence and/or psychological violence or in combination of all the forms of violence within the last 12 months or in her lifetime.

Result

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Mothers and Their Partners

Out of 671 expected study participants, 657 of them participated in the study making a response rate of 98%. The mean age of the respondents was 35.64 (± 9.848 SD) years. The majority of the study participants, 650 (98.9%) were Oromo by ethnicity and 406 (62%) of them were orthodox Christian followers. Nearly fifty percent of the respondents, 339 (51.6%) had no formal education and 235 (35.8%) of the respondents have attended primary education. Regarding their occupation, 389 (59.2%) of the respondents were housewives and 212 (32.3%) were farmers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Married Women in Ambo District, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia, March 2018 (n=657)

| Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents (n=657) | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Age of respondents=35.64 (±9.848) | ||

| 15–24 | 37 | 5.6 |

| 25–34 | 327 | 49.8 |

| >34 | 293 | 44.6 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 406 | 61.8 |

| Protestants | 184 | 28.0 |

| Other* | 67 | 10.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Oromo | 650 | 98.9 |

| Amahara | 7 | 1.1 |

| Educational level | ||

| No formal education | 339 | 51.6 |

| Primary | 235 | 35.8 |

| Secondary and above | 83 | 12.6 |

| Occupation of respondents | ||

| Housewife | 389 | 59.2 |

| Farmer | 212 | 32.3 |

| Other** | 56 | 8.5 |

Notes: Field survey 2018; *Wakefata, Muslim; **Daily labor, merchant.

Concerning the respondents’ husband, the mean age of their current husbands/partners was calculated to be 42.9 (± 11.72 SD) years. The majority of the current partners, 652 (99.5%) were Oromo in ethnicity and 433 (66%) were orthodox Christians. Almost fifty percent of the 316 (48%) of husbands/partners had attended primary education and 196 (29%) of the husband had no formal education. The majority 567 (86%) of the husbands occupation were farmers. One-third 197 (30%) of respondents’ monthly income was less than five hundred Ethiopian Birr (1$ = 27.6677 ETB) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondent’s Husbands/Partners in Ambo District, Oromia Region, State, Ethiopia, March 2018 (n=657)

| Sociodemographic Characteristics (n=657) | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Age husband=42.9(±11.72SD) | ||

| >30 | 172 | 26.2 |

| 30–45 | 173 | 26.3 |

| >45 | 312 | 47.5 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 433 | 65.9 |

| Protestants | 157 | 23.9 |

| Other* | 67 | 10.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Oromo | 654 | 99.5 |

| Amahara | 3 | 0.5 |

| Educational level | ||

| No formal education | 196 | 29.8 |

| Primary | 316 | 48.1 |

| Secondary and above | 145 | 22.1 |

| Occupation of husband | ||

| Farmer | 566 | 86.1 |

| Merchant | 35 | 5.3 |

| Other** | 55 | 8.4 |

| Average monthly income | ||

| <500 ETB*** | 197 | 30.0 |

| 501–2000 ETB | 326 | 49.6 |

| >2001 ETB | 134 | 20.4 |

Notes: *Wakefata, Muslim; **Daily labor, employer; ***Ethiopian Birr (1$USD = 27.6677 ETB).

Sociocultural Practice

Nearly sixty percent 411 (62.6%) of the respondents has engaged in marriage at an age interval of 14–19 years. The mean age of at first marriage for the respondents was 18.45 years (± 2.66 SD). Around 418 (70%) of the respondents had got marriage by family support and while 52 (7.9%) had a marriage by abduction (action of forcibly taking someone away against their will). Most 649 (98.8%) of respondents' marriage was formal and more than seventy 476 (72.5%) of them use customary marriage ceremony to formalize their union. Around 561 (85.2%) of the respondents were in marriage for more than five years. Only 88 (13.4%) percent of the respondents had a history of the previous marriage. Seventy-seven percent 505 (76.9%) of respondents had more than three children and less than three percent of them had no children. More than ninety 506 (92.5%) percent of respondents claims that they have a financial problem. Ninety-nine (15.1%) of the husbands/partners of respondents had more than one wife.

Sixty percent, 393 (59.8%) of the respondents believed that husband dominance in all aspects as appropriate. Fifty percent, 323 (49.2%) of the respondents grew while observed partner violence in their families. Two-third 434 (66%) of the respondents were grown up observing domestic violence in their family and environment. Nearly sixty percent 383 (58%) of respondents had a history of alcohol drinking while 274 (41.1%) of them never drank alcohol. One hundred nine (16.6%) of respondents’ husbands used tobacco; Twenty percent 126 (19.2%) of respondent’s husbands always drank alcohol, while fifty percent 327 (49.8%) of them was drinking alcohol sometimes and one-third 204 (31%) of them never drinks alcohol. Forty-five percent 298 (45.4%) of respondents’ partners have ever experienced alcohol intoxication. Only 14 (2%) of respondent partners chew khat. Less than three percent 15 (2.3%) of partners has a history of mental health problems and around 135 (20.5%) of partners had a history of fighting habit.

Intimate Partner Violence

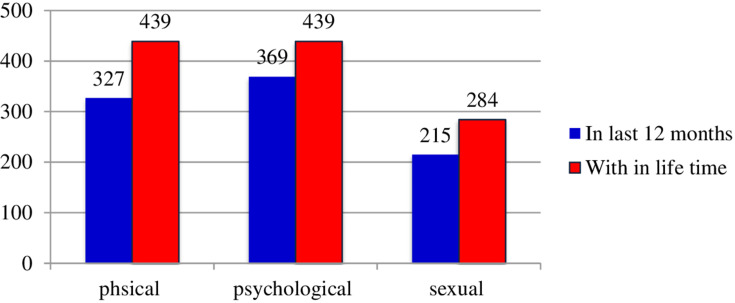

Among the total respondents, 506 (77%) and 410 (62.4%) of them reported that they have experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetime and the last year, respectively. Regarding the type of violence among the victims: 439 (66.8%), 439 (66.8%), and 284 (43.2%) experienced physical, psychological, and sexual violence, respectively, in their lifetime while 327 (49.8%), 369 (56.2%), and 215 (32.7%) experienced physical, psychological, and sexual violence in the last 12 months, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of forms of intimate partner violence among married women in Ambo district, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, March, 2018.

Physical Violence

Respondents were asked to signify the experience they had with intimate partners and different forms of the violence. Regarding the type of physical violence, more than fifty percent 377 (57.4%) and more than one-third 255 (38.8%) of respondents have ever experienced being slapped by their husbands in their lifetime and the last 12 months, respectively. Around fifty percent 321 (48.8%) and 216 (32.8%) of respondents reported having been pushed, gripped, and shoved by their husband in a lifetime and last 12 months, respectively. More than forty percent 274 (41.7%) and more than one-fourth of respondents hit by husbands in a lifetime and last 12 months, respectively. Similarly, forty percent 271 (41.2%), 78 (11.8%), 40 (6%), and 101 (15.3%) of respondents reported kicked/dragged/beaten, choked (preventing from breathing by constricting), burned, threatened for beating by the instrument by her husband in their lifetime, respectively. Around twenty-five percent 177 (26.9%), 35 (5.3%), 21 (3.1%), and 66 (10%) of them kicked/dragged/beaten, choked, burned, threatened to beat by the instrument by her husband, respectively.

Psychological Violence

Regarding types of psychological violence about 400 (60.9%) and 337 (51.2%), of the respondents were disrespected and made feel immoral about themselves in their lifetime and last 12 months, respectively. Besides, one-third 213 (32.8%) of the respondents were made to feel ashamed in front of other persons in their lifetime and the last 12 months. In lifetime and one year prior to the survey, thirty-two and twenty-seven percent of the respondents was frightened by their partner.

Sexual Violence

In case of sexual violence, 210 (40%) of the respondents reported that their partners had forced them to have sexual intercourse while they are not ready to do so and one-fourth 159 (24%) of the situation happened in the last 12 months. Besides, 226 (34.3%) and 159 (24%) of respondents experienced sexual intercourse during their lifetime and in their current relationship due to fear of their husbands/partners. More than twenty-five percent 185 (28%) and 154 (23%) of respondents were forced and frightened for sexual acts in their lifetime and in the last 12 months, respectively.

Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence

The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents, cultural factors and behavioral factors were analyzed with bivariate binary logistic regression to see factors associated with intimate partner violence. Bivariate binary logistic regression analysis showed that age of respondents, education status, occupation of respondents, education of husband, history of previous marriage, years of marriage, marriage arrangement, number of children, believe in husband dominance, respondent’s witness of partner violence, being grown up in domestic violence, respondents and respondents’ husbands' alcohol intake and partner fighting habit were factors associated with intimate partner violence.

Variables that were associated with intimate partner violence at a P-value <0.25 in the bivariate binary logistic regression analysis were included in multivariate binary logistic regression analysis to identify the independent predictors of intimate partner violence. Education of husband, occupation of respondents, number of children, believes on husband dominance, being grown up in domestic violence, alcohol intake of the partners, and partner fighting habit were significantly associated with intimate partner violence at p-value less than or equal to 0.05.

Husbands with no formal education were two times more likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence than those educated secondary and above (AOR=2.306, 95% C.I. 1.28–4.15). Women who have three or more children were four times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those who have no children (AOR=4.376, 95% C.I. 1.40–13.66). Housewife Respondents were two times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than farmer one (AOR = 2.041 (1.02–4.06)). Respondents who believed in husband dominance were two times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those who did not (AOR=1.747, 95% C.I. 1.15–2.63). Respondents who had grown up with domestic violence were two times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those who did not (AOR =1.537, 100–2.35). Partners who drink alcohol sometimes were two times more likely to perpetrate his wife than those who did not drink alcohol (AOR =1.773, 95% C.I. 1.12 −2.79). Husbands/partners who had a history of fighting habit were two times more likely to commit intimate partner violence than those who did not (AOR=2.287, 95% C.I., 1.20–4.34) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence Against Married Women in Ambo District, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia, March 2018 (n=657)

| Variables | Intimate Partner Violence in Lifetime | Crude OR (95% C.I) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Occupation of respondents | ||||

| Farmer | 148 | 64 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Housewife | 310 | 79 | 1.697(1.156 −2.490)* | 2.041(1.026 −4.063)** |

| Others | 48 | 8 | 2.595(1.161–5.957)* | 0.878(0.559 −1.381) |

| Education of husband | ||||

| No formal education | 166 | 30 | 3.094(1.847–5.184)* | 2.306(1.280 −4.152)** |

| Primary | 247 | 69 | 2.002(1.300–3.082)* | 1.516 (0.923 −2.491) |

| Secondary and Above | 93 | 52 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of children | ||||

| 0 | 7 | 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–2 | 89 | 46 | 2.764(0.987–7.737) | 2.324(0.733 −7.375) |

| >3 | 410 | 95 | 6.165(2.288–16.615)* | 4.376(1.402–13.664)** |

| Believe on Husband dominance | ||||

| Yes | 329 | 177 | 2.527(1.744–3.661)* | 1.747(1.159–2.634)** |

| No | 64 | 87 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Grow up in domestic violence | ||||

| Yes | 350 | 84 | 1.790(1.233–2.597)* | 1.537(1.004–2.354)** |

| No | 156 | 67 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Partner alcohol intake | ||||

| Never | 139 | 65 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes | 271 | 56 | 2.263(1.499–3.416)* | 1.773(1.124 −2.798)** |

| Always | 96 | 30 | 1.496(0.903–2.479)* | 1.166(0.666 −2.042) |

| Partner fighting habit | ||||

| Yes | 122 | 384 | 3.373(1.844–6.170)* | 2.287(1.205–4.344)** |

| No | 13 | 138 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Notes: *p-value <0.05 for COR; ** p-value <0.05 for AOR.

Discussion

The results of this study revealed a high prevalence of intimate partner violence with physical and psychological violence contributing to the majority. The finding of this study revealed that 77% and 62.4% of respondents reported that they had experienced intimate partner violence by their husbands in their lifetime (some point in their lives) and within the last 12 months, respectively. The lifetime IPV in this study was higher compared to studies conducted in Nigeria and Butajira revealing 50% and 71% in all three forms, respectively,12,13 whereas it was consistent with studies conducted in East Wollega Zone 76.5% (9) and lower than the study conducted in Bangladesh which was 87%.14 The last 12 months experience of intimate partner violence was higher than study conducted in Iraq, and Nigeria (45.3%,14%) respectively.13,15 This difference might be because of sociocultural and socioeconomic differences between the countries. In contrast to this study finding, studies conducted in Bangladesh 77% and East Wollega 72.5% were lower.9,14 This difference might be due to study design, sample size and socioeconomic status variation. In this study, about 66.8% of the victims had experienced the lifetime physical violence which was higher than studies conducted by WHO in Butajira, southwest Ethiopia, and Gozman district (49%,41%, and 43.7%) respectively.12,16,17 The last 12-month physical violence experience in this study was (49.8%) which is higher than studies conducted in eastern Uganda, Nepal, Nigeria, Butajira, and Gozman district (14%), (12.3%), (28.3%), (29%), and (28%) respectively.9,12,13,15,18,19 But a study in East Wollega (62.6%) indicated a higher prevalence of 12 months of physical violence.9 This difference might be due to socioeconomic, cultural differences and the study setting could also be the factors. Regarding the psychological violence the prevalence is the same with lifetime physical violence which is 66.8% that is lower than the study conducted in Northern Tanzania 82%.20 Whereas higher than the study conducted in Nigeria 28%13 and the last 12-month experience of psychological violence in the East Wollega (63.9%) is higher than this study, which is (56%) but consistent with study in Nigeria 55%.9,13

Concerning sexual violence, this study indicated high prevalence (43.2%) of lifetime sexual violence which is higher than study conducted in Iraq, Nepal, and Rwanda (38.9%, 14%, and 17.4%) respectively,19–21 whereas the last 12-month experience was found to be (32.7%) Which is lower than study conducted in Butajira (44%) and East Wollega (55%) but higher than study in Iraq (12.1%) and Nigeria (23.8%).13,15 This might be due to sociocultural differences.

Husbands with no formal education were two times more likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence than educated ones (AOR=2.14, 95% C.I. 1.22, 3.75). This result was similar to the study finding in southwest Nigeria and Rwanda.13,21 Women who have three or more children were four times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those who have less than three children (AOR=4.06, 95% C.I. 1.4, 11.7). This result was similar to study conducted in Rwanda.21 This might be having many children results in social and economic problems for both parents. Women who believe in husband dominance were two times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those who did not (AOR=1.97, 95% C.I., 1.34, 2.92). This result was similar to the study conducted in the Gozman district.17 This might be due to culturally accepting wife’s beating as it is the appropriate way to correct the women. Husbands/partners who have a history of fighting habit were three times more likely to commit intimate partner violence than those who did not (AOR=2.8, 95% C.I., 1.52, 5.23). This result was similar to the study conducted in china.22 Respondents who grow with domestic violence were two times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than those who did not (AOR =1.54, 1.004–2.35). This result was similar to the study conducted in Sweden.23 This might be those women who grow in domestic violence might consider it as the norm and influence the others too. Partners who drink alcohol sometimes were two times more likely to perpetrate his wife than those who did not drink alcohol (AOR =1.773, 95% C.I. 1.12 −2.79). This result was similar to a study conducted in Nigeria and western Ethiopia.13,16

Since the study was cross-sectional in design so the temporal relationship between the factors and IPV cannot be established. Recall bias may significantly underestimate the prevalence of violence, particularly for lifetime violence.

Conclusion

Intimate partner violence against women remains an important public health problem among married women in this study area. Specifically, the physical and psychological violence against married women by their male partners was found to be high. Husband’s educational status, occupation respondent, number of children, believes on husband dominance, grow up in domestic violence, partner’s alcohol intake, and husband fighting habit were significantly associated with intimate partner violence against married women.

Ambo District Women, Child and Youth Affaires should strengthen work on women empowerment considering the identified factors; promote gender equality to reduce intimate partner violence against women. Ambo District Justice & Court Office should ensure their structure to the grass-root level of the community for fair justice and public awareness creation on intimate partner violence. Ambo District Health Office Health Extension Workers should strengthen health education on intimate partner violence. NGOs that are working in the study area should pay attention to the issue of intimate partner violence and should participate in the way of increasing public awareness. The local communities should involve in collaborating effort to reduce the traditional notions that male dominance and beating wife are justifiable and acceptable. Ambo District Education Office and District Health Office should strengthen non-formal adult education to increase awareness and come up with a behavioral change on intimate partner violence. Lastly, the recommendation goes to other researchers to carry out further analysis to identify the circumstance of intimate partner violence such as consequence and its impact.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants and all other peoples who had formally or informally involved in the accomplishment of this research.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this study.

Abbreviations

CI, confidence interval; ETB, Ethiopian Birr; HH, household; IPV, intimate partner violence; NGOs, non-governmental organizations; SD, standard deviation; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; USD, United States Dollar; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

Data will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The ethical issue was approved by the Research and Ethical Review Committee of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University with Ref. No.: CMHS-ERC: 31/2010 and project number: CMHS: 007/18. Hierarchically all administrative bodies were communicated and permission was secured. Verbal informed consent was obtained from the study subjects who aged eighteen years and above, and the verbal informed consent process was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of College of Medical and Health Sciences, Ambo University. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent/legal guardian for study subjects whose age was below eighteen years after explaining objectives and procedures of the study and their right to participate or to withdraw at any time in of the interview. The Research and Ethical Review Committee also approved its ethical issues as there was no procedure that affects the study subject and the data is used only for research purpose. For this purpose, a one-page consent letter was attached to the cover page of each questionnaire stating about the general purpose of the study and issues of confidentiality which was discussed by data collectors before proceeding to the interview. Lastly, we confirm that this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Popul Rep. 1999;27(4):1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States. Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States. CDC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, Rivara FP, Carrell D, Thompson RS. Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1692–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcıa-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stö Ckl H, Watts C, Abrahams N. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence Geneva, Switzerland. World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macro I, Statistics KNBo. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.CSA I. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa, Rockville: CSA and ICF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abeya SG, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Intimate partner violence against women in western Ethiopia: prevalence, patterns, and associated factors. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):913. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambo District Health Office. Annual plan and report. 2018.

- 11.World Health Organization. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Life Experiences. Core Questionnaire, Version. 2003:10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Moreno C, Jansen H, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women. Vol. 204 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onigbogi MO, Odeyemi KA, Onigbogi OO. Prevalence and factors associated with intimate partner violence among married women in an urban community in Lagos State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2015;19(1):91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossen MA. Measuring Gender-Based Violence: Results of the Violence Against Women (VAW) Survey in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Ministry of Planning; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Atrushi HH, Al-Tawil NG, Shabila NP, Al-Hadithi TS. Intimate partner violence against women in the Erbil city of the Kurdistan region, Iraq. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deribe K, Beyene BK, Tolla A, Memiah P, Biadgilign S, Amberbir A. Magnitude and correlates of intimate partner violence against women and its outcome in Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andualem M, Tiruneh G, Gizachew A, Jara D. The prevalence of intimate partner physical violence against women and associated factors in Gozaman Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia 2013. Global J Sex Educ. 2014;2:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wandera SO, Kwagala B, Ndugga P, Kabagenyi A. Partners’ controlling behaviors and intimate partner sexual violence among married women in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):214. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1564-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrestha R, Copenhaver MM. Association between intimate partner violence against women and HIV-risk behaviors: findings from the Nepal demographic health survey. Violence Against Women. 2016;22(13):1621–1641. doi: 10.1177/1077801216628690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapiga S, Harvey S, Muhammad AK, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and abuse and associated factors among women enrolled into a cluster randomised trial in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umubyeyi A, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. Women are considerably more exposed to intimate partner violence than men in Rwanda: results from a population-based, cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu X, Zhu F, O’Campo P, Koenig MA, Mock V, Campbell J. Prevalence of and risk factors for intimate partner violence in China. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):78–85. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.023978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nybergh L, Taft C, Enander V, Krantz G. Self-reported exposure to intimate partner violence among women and men in Sweden: results from a population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]