Abstract

Cerebrovascular adaptation to pregnancy is poorly understood. We sought to assess cerebrovascular regulation in response to visual stimulation, hypercapnia and exercise across the three trimesters of pregnancy. Using transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound, middle and posterior cerebral artery mean blood velocities (MCAvmean and PCAvmean) were measured continuously at rest and in response to (1) visual stimulation to assess neurovascular coupling (NVC); (2) a modified Duffin hyperoxic CO2 rebreathe test, and (3) an incremental cycling exercise test to volitional fatigue in non-pregnant (n = 26; NP) and pregnant women (first trimester [n = 13; TM1], second trimester [n = 21; TM2], and third trimester [n = 20; TM3]) in total 47 women. At rest, MCAvmean and PETCO2 were lower in TM2 compared to NP. PCAvmean was lower in TM2 but not TM1 or TM3 compared to NP. Cerebrovascular reactivity in MCAvmean and PCAvmean during the hypercapnic rebreathing test was not different between pregnant and non-pregnant women. MCAvmean continued to increase over the second half of the exercise test in TM2 and TM3, while it decreased in NP due to differences in ΔPETCO2 between groups. Pregnant women experienced a delayed decrease in MCAvmean in response to maximal exercise compared to non-pregnant controls which was explained by CO2 reactivity and PETCO2 level.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, cerebral blood flow, exercise, physiology, pregnancy

Introduction

Pregnancy is associated with profound cardiovascular adaptations in order to support the needs of the growing fetus. Maternal blood volume expands by 50% throughout gestation1 which is accompanied by an increase in heart rate and stroke volume, and a significant drop in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) which reaches a nadir in the second trimester.2 In non-pregnant populations, cerebral blood flow (CBF) is exquisitely regulated to maintain adequate perfusion to the brain.3 The increased cardiovascular load and circulating factors that rise over the course of pregnancy pose a unique challenge for the brain, which requires a constant and carefully regulated blood supply. Based on rigorous work conducted in animals, we know that high levels of circulating growth factors and cytokines that promote substantial hemodynamic changes in other vascular beds during pregnancy exhibit a limited influence on cerebral circulation.4 Remodeling of arteries, which is highly important for vascular function and structure in other organs during pregnancy, is prevented and even reversed in cerebral arteries.5 Remarkably, blood–brain barrier function is unperturbed in healthy pregnancy, despite a significant increase in circulating vasoactive permeability factors.6

Recent statistics indicate a stroke risk between 4 and 40 per 100,000 in women of childbearing age.7 Although the risk of stroke remains relatively low during pregnancy (the overall prevalence in the antenatal and postpartum period is estimated at 30 per 100,000),8 this is higher than the non-pregnant population. In addition, the risk of stroke is four to six times higher in women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and in the peripartum period.9 These findings strongly suggest that the pregnant brain may be vulnerable to physiological stress. Yet the impact of pregnancy on cerebrovascular function in humans remains poorly understood.10,11

To date, there have been a handful of investigations examining the cerebrovascular regulation in healthy human pregnancy. While, we recently demonstrated progressively augmented cerebrovascular responsiveness to changes in CO2 over the course of pregnancy in a longitudinal case report,27 other data suggest that cerebrovascular PETCO2 reactivity may be similar between pregnant women in the third trimester compared to non-pregnant controls.12 Additional data suggest similar cerebral neurovascular coupling responses in third trimester women compared to non-pregnant controls.13 To date, our case study remains the only data related to cerebrovascular regulation in early and mid-pregnancy and no data exist to our knowledge on the functional cerebral responses to exercise.

Regular physical activity during pregnancy is associated with a 40% decrease in the risk of developing serious pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia which are known to impact cerebral circulation.14 In non-pregnant populations, exercise intensity up to 60% of maximal oxygen uptake results in a continuous increase in CBF.15 However, higher intensity exercise leads to a decline in CBF towards baseline values due to the influence of hyperventilation-induced cerebral vasoconstriction.15 To date, the cerebrovascular response to acute exercise during pregnancy is unknown. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to examine the impact of pregnancy on resting CBF and reactivity to (1) visual stimulation (NVC); (2) hypercapnic rebreathe (humoral stimulation); and (3) progressive exercise to volitional fatigue. We hypothesized that resting CBF would be similar or slightly decreased over the three trimesters of pregnancy compared to non-pregnant women. We further hypothesized that the reactivity of the middle and posterior cerebral arteries (MCA and PCA, respectively) to visual stimulation, CO2 rebreathe, and exercise would be increased from the first to the third trimester compared to non-pregnant controls.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

This test protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Approval No. Pro00040722) and conformed to the standards set by the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Participants (n = 47) who were >18, non-smokers (minimum one year), were having a singleton pregnancy, were not pregnant in the last six months (non-pregnant women) and free from known neurological, respiratory, or cardiovascular diseases completed testing at one or more time points. The experimental breakdown included assessments grouped by: nonpregnant assessments [n = 26; NP], first trimester assessments [n = 13; TM1], second trimester assessments [n = 21; TM2], or third trimester assessments [n = 20; TM3]. A complete breakdown of participant assessments (NP, TM1, TM2, and TM3) is shown in Supplemental Table 1. All participants provided both verbal and written informed consent prior to participation in this study. Gestational age was calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period and confirmed by ultrasound. None of the participants reported a history of gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, or preeclampsia. Nonpregnant women were tested during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, with the exception of those who were taking hormonal contraceptives where cycling had ceased (Nuva Ring, n =1; Min-Ovral, n = 1; Yasmin, n = 1; Yaz, n = 1); these women were tested at their convenience. Pregnant women received medical clearance from their health care provider prior to exercise testing (PARMed-X 2013).16 Nonpregnant women completed the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) to pre-screen for potential contraindications to exercise (Par-Q and You 2002).17

Instrumentation

Participants were instrumented with transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD; Multigon Industries, TOC 2MD Yonkers, NJ, USA) of the middle and posterior cerebral arteries (MCA and PCA) to measure the cerebral blood velocity (CBV; cm/s), an approximation of CBF (mL/min).18,19 Mean MCA and PCA flow velocities (MCAvmean and PCAvmean, respectively) were calculated on a beat-by-beat basis as the area under the peak velocity waveform. Probe placement and craniofacial landmarks were traced onto transparencies at participant’s initial visit in order to standardize probe placement for subsequent visits.

Participants were instrumented with a respiratory apparatus consisting of a nose clip, a mouthpiece, a disposable bacteriological filter, and a heated (37 °C) respiratory flow head (MLT1000L, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, Colo., USA). Respiratory flow was measured by the pneumotachometer (MLT3819H-V, Hans Rudolph Inc., Shawnee, Ky., USA) and spirometer amplifier (FE141, ADInstruments). The respiratory flow head was calibrated daily using a 3-L calibration syringe (Hans Rudolph Inc.).

Continuous electrocardiogram (ECG; lead II) was measured throughout testing. Blood pressure was measured continuously using photoplethysmography (Finometer; Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and was calibrated post-test to baseline blood pressure values obtained using manual mercury sphygmomanometry. Calibrated pressure waveforms were analyzed to determine beat-by-beat mean (MAP), systolic (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Signals were recorded at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz.

Experimental protocol

Participants arrived at the laboratory following a 12-h fast and having abstained from caffeine, alcohol, and strenuous exercise for 12 h. On arrival, participants were fed a standardized meal. Participant body weight was measured with a standard calibrated scale, and height was measured with a stadiometer. Participants were seated on a recumbent cycle ergometer (45°; Cardio Comfort 837E, Monark, Sweden) in a laboratory maintained at 20 °C, and they rested for a minimum of 20 min before beginning the protocol which consisted of:

Visual stimulus.20 Following a 2-min eyes-closed baseline in a dark room, participants opened their eyes for five trials of 30 s of flashing light (0.10 s light/dark cycles) separated by four periods of 30 s with eyes-closed in a dark room. For the visual stimulus test, seconds −18 to 0 were combined to represent time 0 (baseline). Seconds 2 to 20 of the stimulus portion of the test were presented as an average value of the five stimulus exposure trials.

Modified Duffin hyperoxic CO2 rebreathing test.21–23 Following 5 min of baseline, participants voluntarily hyperventilated until PETCO2 was reduced to ∼25 Torr for 1 min. After a full inspiration and expiration, participants were switched using a three-way valve to a bag containing 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and instructed to inspire one deep breath. Participants then resumed natural breathing until: (1) their PETCO2 reached 55 Torr; (2) the bag deflated; or (3) they used previously agreed upon hand signals to indicate they wished to terminate the test.

Incremental exercise to volitional fatigue. Following a 5-min inactive baseline, participants cycled for 5 min at 25 W, maintaining a pedal rate of 50 r/min. Following the 5-min warm-up, the pedal rate was maintained at 50 r/min, and the work rate was increased by 25 W/min until volitional fatigue. Perceived exertion was recorded every second increment during exercise, using a Borg scale.24 On reaching volitional fatigue, participants underwent a 5-min active recovery period at 25 W.

Data and statistical analyses

One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test and Fischer’s exact test were used to determine whether descriptive characteristics of the participants varied between groups. Multilevel mixed-effects models were employed to examine the impact of TM1, TM2, and TM3 of pregnancy compared to NP (reference group) on physiological outcomes over (1) seconds during the visual stimulus test and (2) watts during the exercise test until volitional fatigue due to the unbalanced nature of measurements per participant. Consecutively, linear, quadratic, cubic, quartic, and quintic time, and the interaction between phase of pregnancy and these time components were considered and all lower order variables were included in the model when higher order variables were significant. Analyses of the hypercapnic rebreathe test were conducted using multilevel modelling of the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular responses to CO2 Torr during the initial response component of the test (see Online Supplement Figure 1). The cerebral blood flow response to exercise has been shown to be bimodal, with a plateau or drop above anaerobic threshold due to a concomitant reduction in PETCO2.15 MCA and PCA resistances were calculated as , while MCA and PCA conductances were calculated as . For the incremental exercise test, corrected MCAvmean and PCAvmean values were adjusted for participants’ CO2 reactivity to the CO2 rebreathe test and the change in PETCO2 from baseline during the exercise test (MCAvmean and PCAvmean corrected).

Models were conducted with clustering at the participant and the (nested) participant-by-phase level. Unstructured variance/covariance structure was employed in all mixed-effects models unless covariance was non-significant at an alpha level of 0.05, in which case independent variance/covariance structure was more appropriate. First, second, and third level residuals were graphed to test the assumptions of normality and homogeneity. All statistical analyses were carried out in consultation with a statistician with formal training in advanced multilevel modelling. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata MP 13.

Results

Anthropometric and baseline characteristics

In our analysis of 213 assessments from 47 participants (see Supplemental Table 1), gestation (wk) and weight (kg) were significantly different between groups (as expected), while height (cm), non/prepregnant BMI (kg/m2), parity, and pregnant BMI (kg/m2) between the three pregnant groups were not different (Table 1). As expected, baseline mean arterial pressure (MAP) was lower, while heart rate was higher across pregnancy compared to NP. PETCO2 was lower in TM2 and TM3 compared to NP. Tidal volume was significantly higher in TM2 and TM3, while VE was significantly increased in TM3 only. Respiratory rate was not significantly different in pregnancy. MCAvmean was progressively lower in TM2 and TM3 compared to NP (TM2 β: −5.87, 95% CI: −11.18, −0.55; TM3 β: −6.39, 95% CI: −11.83, −0.95; NP constant term: 63.93). PCAvmean reached a nadir that was lower in TM2 but not TM1 or TM3 compared to NP (β: −8.17, 95% CI: −13.51, −2.84; NP Constant term: 42.28). Taking into account concurrent changes in blood pressure, MCA and PCA resistance and conductance were not different in TM1, TM2, or TM3 compared to NP at rest.

Table 1.

Descriptive and baseline characteristics of the participants.

| NP (n = 26) | TM1 (n = 13) | TM2 (n = 21) | TM3 (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 28±6 | 31±4 | 31±4 | 31±4 |

| Gestation (wk)* | N/A | 11±1 | 24±1 | 33±2 |

| Height (cm) | 167±6 | 167±6 | 167±7 | 168±7 |

| Weight (kg)* | 65±11 | 71±20 | 73±12 | 76±11 † |

| Non/prepregnant BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1±3.4 | 23.2±1.9 | 23.1±2.6 | 23.1±2.7 |

| Pregnant BMI (kg/m2) | N/A | 25.5±7.4 | 25.8±4.2 | 26.6±2.3 |

| Parity (count 1/0; % with parity=1) | 7/19 (26%) | 5/8 (38%) | 7/14 (33%) | 5/15 (25%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 22 (85%) | 12 (92%) | 19 (90%) | 17 (85%) |

| Asian | 2 (8%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

| Other | 2 (8%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| MAP (mmHg)* | 90.99 | −4.60 † | −10.31 § | −7.54 § |

| (88.37, 93.62) | (−9.11, −0.08) | (−14.16, −6.47) | (−11.44, −3.64) | |

| Heart rate (bpm)* | 71.59 | +8.24 § | +9.34 § | +13.89 § |

| (68.03, 75.15) | (3.88, 12.60) | (5.49, 13.19) | (10.01, 17.78) | |

| PET CO2 (Torr)* | 39.54 | −2.27 | −2.45 † | −3.87 ‡ |

| (37.79, 41.28) | (−4.90, 0.36) | (−4.72, −0.18) | (−6.18, −1.56) | |

| Tidal volume* | 0.75 | +0.03 | +0.14 † | +0.18 ‡ |

| (0.65, 0.85) | (−0.10, 0.15) | (0.03, 0.25) | (0.08, 0.29) | |

| Respiratory rate | 19.13 | −1.10 | −1.36 | −0.82 |

| (17.83, 20.43) | (−3.13, 0.94) | (−3.14, 0.41) | (−2.61, 0.97) | |

| VE* | 14.07 | +0.09 | +2.49 | +3.97 † |

| (10.34, 17.79) | (−3.75, 3.94) | (−0.95, 5.92) | (0.63, 7.31) | |

| MCAvmean* | 63.93 | −2.63 | −5.87 † | −6.39 † |

| (60.11, 67.74) | (−8.88, 3.62) | (−11.18, −0.55) | (−11.83, −0.95) | |

| PCAvmean* | 42.28 | −3.00 | −8.17 ‡ | −4.62 |

| (38.38, 46.18) | (−9.21, 3.22) | (−13.51, −2.84) | (−10.15, 0.91) | |

| MCA resistance | 1.48 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| (1.37, 1.59) | (−0.29, 0.11) | (−0.20, 0.13) | (−0.20, 0.14) | |

| PCA resistance | 2.39 | −0.07 | +0.16 | −0.05 |

| (2.05, 2.73) | (−0.63, 0.49) | (−0.32, 0.64) | (−0.55, 0.44) | |

| MCA conductance | 0.69 | −0.02 | +0.0006 | −0.008 |

| (0.63, 0.76) | (−0.13, 0.10) | (−0.09, 0.10) | (−0.10, 0.09) | |

| PCA conductance | 0.49 | +0.05 | −0.04 | −0.02 |

| (0.44, 0.54) | (−0.04, 0.14) | (−0.12, 0.04) | (−0.10, 0.06) |

Note: Data are presented as means ± SD or constant term (95% CI) and β coef (95% CI). Significant values are in bold.

*Significant difference between groups (p < 0.05).

†Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.05).

‡Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.01).

§Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.001).

p-values adjusted for clustering by individual.

BMI: body mass index; NP: nonpregnant; TM1: first trimester; TM2: second trimester; TM3: third trimester.

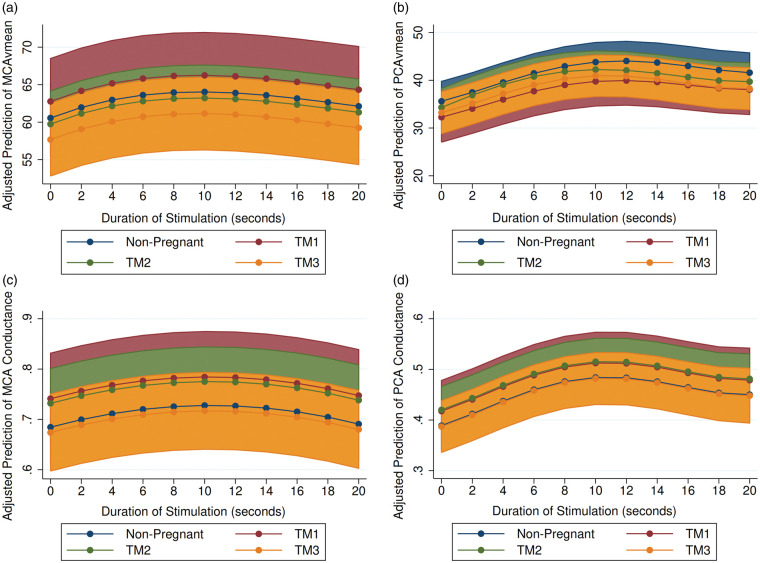

Neurovascular coupling

In response to visual stimulation (increased local metabolism), maximum absolute and relative values of PCAvmean were not different between pregnant and non-pregnant groups (Figure 1). However, the rate of response to stimulation was faster in TM2, (shorter time to peak velocity) compared to NP (β: −2.10 s, 95% CI: −4.37, 0.17; p = 0.069). MCAvmean and MCA/PCA conductance responses were not different between groups (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

The predicted response to NVC challenge in: (a) MCAvmean; (b) PCAvmean; (c) MCA conductance; and (d) PCA conductance over light stimulation duration in seconds. Light stimulation began at time 1 s and ceased at time 30 s. All models adjusted for within-participant variability. Shaded area represents 95% Confidence Interval. Blue – nonpregnant; red – TM1; green – TM2; yellow – TM3. BL: baseline; MCA: middle cerebral artery; PCA: posterior cerebral artery; TM1: trimester 1; TM2: trimester 2; TM3: trimester 3.

Table 2.

CBF and hemodynamic results from mixed-effects MLM across time (seconds) during the NVC light stimulus test.

| Variable | NP constant term (95% CI) | TM1 β Coef. (95% CI) | TM2 β Coef. (95% CI) | TM3 β Coef. (95% CI) | Significant interaction with time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP(mm Hg) | 88.64 | −6.65† | −7.46 † | −2.52 | |

| (84.60, 92.69) | (−12.52, −0.78) | (−12.60, −2.31) | (−7.92, 2.89) | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 67.85 | +8.93 † | +11.15 ‡ | +15.86 ‡ | |

| (63.83, 71.88) | (3.02, 14.84) | (5.99, 16.31) | (10.44, 21.29) | ||

| MCAvmean (cm/s) | 60.56 | +2.21 | −0.81 | −2.88 | |

| (55.92, 65.19) | (−5.06, 9.48) | (−7.05, 5.43) | (−9.47, 3.71) | ||

| PCAvmean (cm/s) | 35.58 | −3.39 | −1.23 | −2.35 | TM2 |

| (31.87, 39.30) | (−9.30, 2.51) | (−6.29, 3.83) | (−7.69, 3.00) | ||

| Time to peak PCAvmean | 12.00 | +0.33 | −2.10‡ | −0.24 | |

| (10.35, 13.65) | (−2.27, 2.94) | (−4.37, 0.17) | (−2.60, 2.13) | ||

| MCA conductance | 0.68 | +0.06 | +0.05 | −0.01 | |

| (0.61, 0.76) | (−0.06, 0.17) | (−0.05, 0.15) | (−0.11, 0.09) | ||

| PCA conductance | 0.389 | +0.029 | +0.031 | −0.002 | |

| (0.34, 0.44) | (−0.05, 0.11) | (−0.03, 0.10) | (−0.07, 0.07) |

Note: Data are presented as adjusted means (for reference term), β coefficients, and 95% Confidence Intervals. Analyses were adjusted for clustering by participant and participant × phase.

Significant values in bold. †Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.05).

Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.01).

BP: blood pressure; MCA: middle cerebral artery; NP: nonpregnant; TM1: first trimester; TM2: second trimester; TM3: third trimester; PCA: posterior cerebral artery.

Modified Duffin hyperoxic rebreathing test

There was no difference in response to CO2 between the NP and TM1, TM2, or TM3 groups during the CO2 rebreathe test in MAP, heart rate, MCAvmean, PCAvmean, MCA resistance, PCA resistance, tidal volume, or frequency of breathing (Table 3). While the hypercapnic ventilatory response (HCVR) was significantly predicted by phase of pregnancy, no one phase on its own was significantly different from NP.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory responses during the initial response phase of the modified Duffin CO2 rebreathe test.

| NP | TM1 | TM2 | TM3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant term | β Coef. | β Coef. | β Coef. | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |

| MAP (mmHg) | 0.69 | +0.06 | −0.08 | −0.14 |

| (0.21, 1.16) | (−0.57, 0.69) | (−0.87, 0.72) | (−0.68, 0.40) | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | −0.90 | −0.53 | +0.22 | +0.37 |

| (−1.47, −0.32) | (−1.49, 0.42) | (−0.66, 1.11) | (−0.42, 1.16) | |

| MCAvmean | 2.86 | +0.79 | +0.42 | +0.35 |

| (2.28, 3.45) | (−0.26, 1.84) | (−0.32, 1.17) | (−0.42, 1.12) | |

| PCAvmean | 1.61 | +0.42 | +0.30 | +0.25 |

| (1.19, 2.03) | (−0.36, 1.20) | (−0.31, 0.92) | (−0.32, 0.82) | |

| MCA resistance | −0.067 | −0.002 | −0.012 | +0.003 |

| (−0.09, −0.05) | (−0.03, 0.03) | (−0.05, 0.03) | (−0.02, 0.03) | |

| PCA resistance | −0.09 | −0.031 | −0.040 | −0.004 |

| (−0.12, −0.06) | (−0.09, 0.03) | (−0.10, 0.02) | (−0.05, 0.04) | |

| Tidal volume | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | +0.03 |

| (−0.04, 0.08) | (−0.11, 0.07) | (−0.09, 0.06) | (−0.04, 0.10) | |

| Frequency of breathing | 0.03 | −0.45 | +0.09 | +0.06 |

| (−0.22, 0.28) | (−1.05, 0.15) | (−0.33, 0.50) | (−0.50, 0.63) | |

| VE* | 0.21 | −0.46 | −0.07 | +0.62 |

| (−0.37, 0.80) | (−1.40, 0.47) | (−0.86, 0.73) | (−0.24, 1.48) |

Note: Data are presented as adjusted means (for reference term), β coefficients, and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were adjusted for clustering by participant.

*Pregnancy phase significantly predicted values according to linear regression adjusted for clustering by participant (p < 0.05).

BP: blood pressure; MCA: middle cerebral artery; NP: nonpregnant; TM1: first trimester; TM2: second trimester; TM3: third trimester; PCA: posterior cerebral artery.

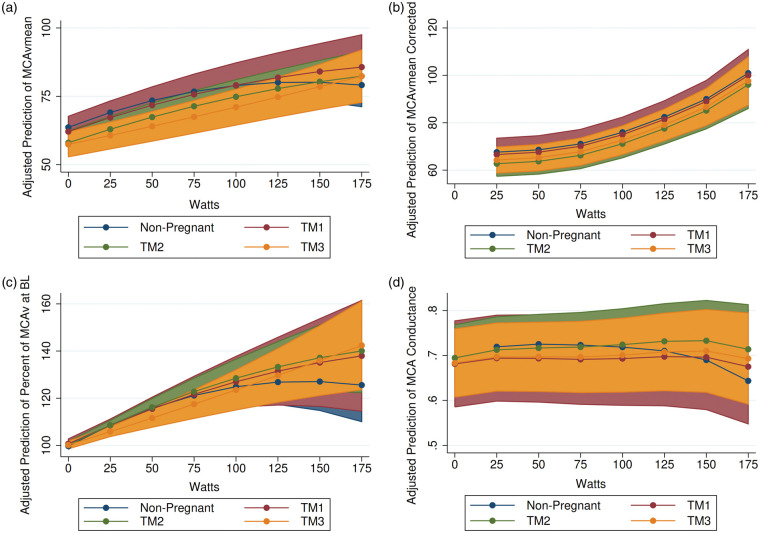

Incremental exercise test to volitional fatigue

A similar proportion of participants in each group completed the maximal stage of the exercise test (W = 175): NP – 48%; TM1 – 50%; TM2 – 22%; TM3 – 37%; Fischer’s exact test p-value = 0.296. HR increased during the test in all four groups, with HR starting at a lower point and ending at a higher point in NP compared to TM1, TM2, and TM3. MAP increased linearly and equivalently in all four groups during the course of the test but remained lower in TM2 and TM3 compared to NP. Prior to exercise, MCAvmean was significantly lower in TM2 and TM3 compared to NP, and progressively decreased over gestation as pregnancy progressed (see Table 4). As expected, MCAvmean decreased from 100 to 175 W (test end) in NP (Figure 2). However, this drop in MCAvmean did not occur in TM2, and MCAvmean actually continued to rise until volitional fatigue in TM3. Following correction for individual CO2 reactivity from the Duffin hypercapnic rebreathe test and change in PETCO2 during the exercise test (MCAvmean Corrected), estimated change in MCAvmean in response to exercise was no longer different in TM2 and TM3 compared to NP. The response in PCAvmean during the exercise test was similar between pregnant and non-pregnant participants (see Online Supplement Figure 2). Correction for individual CO2 reactivity from the Duffin hypercapnic rebreathe test and change in PETCO2 during the exercise test (PCAvmean Corrected) did not explain the response in PCAvmean to exercise in pregnancy. The response in MCA conductance during exercise was also different between pregnant and non-pregnant participants. MCA conductance decreased from 50 to 175 W (test end) in NP but did not decrease in TM1, TM2, or TM3 until 150 to 175 W. As a result, predicted MCA conductance appeared to be lower at 175 W in NP compared to TM1, TM2, and TM3. Similarly, the response of PCA conductance was significantly different in TM2. PCA conductance slowly decreased from 50 to 175 W in NP, but not TM2. Changes in O2 and CO2 in response to exercise can be seen in Online Supplement Figure 3.

Table 4.

CBF results from mixed-effects MLM across watts (0(25)200) during incremental exercise to volitional fatigue.

| Variable | NP (ref)Constant term(95% CI) | TM1β Coef.(95% CI) | TM2β Coef.(95% CI) | TM3β Coef.(95% CI) | Significant interaction with time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCAvmean | 63.64 | −1.54 | −5.64 * | −6.23 * | TM2 TM3 |

| (59.73, 67.54) | (−8.05, 4.96) | (−11.15, −0.12) | (−11.88, −0.57) | ||

| MCAvmean corrected | 63.37 | −1.00 | −4.86 | −3.33 | |

| (58.60, 68.14) | (−9.25, 7.24) | (−11.86, 2.15) | (−10.45, 3.79) | ||

| PCAvmean | 42.30 | −2.17 | −8.59† | −4.82 | |

| (38.29, 46.32) | (−8.54, 4.20) | (−14.05, −3.12) | (−10.49, 0.85) | ||

| PCAvmean corrected | 42.17 | +1.23 | −2.35 | −1.37 | TM1 TM3 |

| (36.00, 48.33) | (−9.21, 11.67) | (−11.27, 6.57) | (−10.45, 7.71) | ||

| MCA conductance | 0.69 | −0.012 | +0.001 | −0.010 | TM1 TM2 TM3 |

| (0.63, 0.76) | (−0.13, 0.10) | (−0.10, 0.10) | (−0.11, 0.09) | ||

| PCA conductance | 0.49 | +0.06 | −0.04 | −0.02 | TM2 |

| (0.44, 0.54) | (−0.03, 0.15) | (−0.12, 0.04) | (−0.10, 0.06) |

Note: Multilevel model adjusted for random intercept at the participant and (nested) participant x phase of pregnancy levels. Data are presented as adjusted means (for reference term), β coefficients, and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were adjusted for clustering by participant.

Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.05).

Significant difference vs. NP (p < 0.01).

BP: blood pressure; MCA: middle cerebral artery; NP: nonpregnant; TM1: first trimester; TM2: second trimester; TM3: third trimester; PCA: posterior cerebral artery.

Figure 2.

The predicted response to incremental exercise to volitional fatigue in (a) MCAvmean; (b) MCAvmean corrected for CO2 reactivity; (c) MCAv at baseline (BL); and (d) MCA conductance adjusted for within-participant variability. Exercise was conducted on a recumbent ergometer. Following a 5-min warm-up, the pedal rate was maintained at 50 r/min, and the work rate was increased by 25 W/min until volitional fatigue. Shaded area represents 95% Confidence Interval. Blue – nonpregnant; red – TM1; green – TM2; yellow – TM3. MCA: middle cerebral artery; TM1: trimester 1; TM2: trimester 2; TM3: trimester 3.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates several novel observations of cerebral blood flow regulation in pregnancy. Foremost, MCAvmean was progressively lower at rest in TM2 and TM3. PCAvmean, on the other hand, was significantly lower at rest in TM2, but returned to non-pregnant values in TM3. Second, the time to peak PCAvmean value during the neurovascular coupling (NVC) test occurred earlier in TM2 than NP (p = 0.07). Third, the change in CBF in response to progressive hypercapnic exposure (modified Duffin rebreathe test) was not different during pregnancy. Finally, MCAvmean did not decrease during maximal exercise in TM2 and TM3 like it did in NP.

Influence of pregnancy on resting MCAvmean and PCAvmean

Our findings suggest that MCAvmean and PCAvmean are decreased during mid-pregnancy at rest. However, while MCAvmean decreased further in late pregnancy, PCAvmean returned to non-pregnant values in the third trimester, which suggests that blood flow in these two arteries is controlled by divergent processes.

Cerebrovascular function response to stimuli

Neurovascular coupling

Neural activation elicits local increases in CBF to support neural metabolism.25 Functional hyperemia in response to stimulation maintains blood flow to maintain the supply of oxygen and nutrients to active areas of the brain.25 One published study examining NVC during late pregnancy demonstrated similar responses to visual stimulation between third trimester pregnant versus non-pregnant women.13 However, latency of visually evoked potentials have also been found to be shorter in pregnancy compared to the postpartum period.26 Our data confirm a similar NVC response in late pregnancy but extend the findings to demonstrate that time to peak response may be reached sooner for PCAvmean in TM2 compared to NP. Reduced pH buffering capacity in response to increased CO2 may explain this association.27 As pregnancy is associated with a dynamic changes in cardiovascular function (e.g. curvilinear response to BP across gestation), longitudinal assessments of cerebrovascular function are needed to fully understand the dynamics of adaptation of the pregnant brain. In comparison to normotensive pregnancy, severe preeclampsia has been associated with a prolonged latency of visually evoked potentials.26 Interestingly, this delay in response resolved in the postpartum period.26

Hypercapnia

Vasoactive factors act directly on downstream arterioles leading to altered cerebrovascular resistance which ultimately influences CBF.28 Increasing PaCO2 is commonly used to assess cerebral vascular smooth muscle relaxation via NO-mediated endothelial vasodilation.29–31 During pregnancy, MCAvmean reactivity to hypercapnia between pregnant and non-pregnant women has been reported to be similar between groups.13 The Duffin hyperoxic rebreathe method, which involves increasing CO2 by rebreathing exhaled gases, allows the examination of cerebrovascular changes to dynamic changes in CO2 while maintaining elevated O2 levels. Our previous case study observed an apparent progressive increase in cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2 across pregnancy., 27 This occurred in the presence of a progressive reduction in basal PETCO2 (associated with mild alkalosis) and reduced bicarbonate.27 Therefore, we hypothesized that this previously observed augmentation in reactivity was due to a steeper gain in the hypocapnic range and a reduced capacity to buffer changes in pH owing to a reduced bicarbonate. The present study showed that in response to increasing hypercapnia, cerebrovascular reactivity across pregnancy was not changed, despite lower basal PETCO2 and CBF values in the second and third trimester. We were unable to collect blood samples in the current study to determine the influence these factors may have had on our current results. Nonetheless, the confidence intervals associated with our measurement of cerebral reactivity to CO2 do suggest some individuals with augmented reactivity in later pregnancy (see Table 3). It is likely that normal variation in reactivity is dependent on prevailing arterial blood gases and the ability to buffer changes in pH during subsequent alterations in CO2. This is yet to be confirmed.

Exercise

In non-pregnant populations, CBF rises with increasing exercise intensity until ∼60% of maximal oxygen uptake, after which there is a decline in CBF towards baseline values due to the influence of hyperventilation-induced cerebral vasoconstriction.15 We also found that CBF increased and then began to decline around 100–125 W of output in healthy non-pregnant women. However, we found that women in TM2 and TM3 demonstrate significantly different CBF responses during moderate to high intensity exercise. While MCAvmean was significantly lower at baseline in TM2 and TM3 participants, MCAvmean remained constant in TM2 participants and increased in TM3 participants during the second half of the exercise test, respectively. In non-pregnant individuals, decreasing CO2 due to hyperventilation drives down CBF. We found that incorporating individual cerebral responsiveness to changes in CO2 observed in the rebreathing protocol explained this difference. As a result, brain blood flow appeared to be protected during the second and third trimester of pregnancy during moderate to vigorous intensity exercise. Additionally, these results suggest that pregnant women may be protected against syncope during vigorous exercise due to a lesser drop in PETCO2 values, rather than changes in cerebrovascular reactivity to changes in CO2 per se.

The impact of chronic exercise on cerebrovascular blood flow and reactivity in pregnancy is unknown. Compared to sedentary individuals, non-pregnant subjects with elevated cardiorespiratory fitness have higher resting intracranial blood velocity in the MCA32,33 and PCA.34 However, these increases in resting CBF are accompanied by a reduced reactivity in response to changes in CO2 in physically fit individuals.34 Conversely, long-term aerobic exercise training can increase cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity in previously sedentary non-pregnant populations,35 and may have a similar influence on pregnant individuals; this has yet to be examined. Additional work is also required to determine whether cerebrovascular reactivity during exercise is altered by pregnancy-related diseases such as pre-eclampsia and whether measures of autoregulation (e.g. transfer function analysis) correlate to clinical outcomes in healthy and complex pregnancy.

Limitations

Despite its usefulness as a measurement technique, the limitations of TCD must be highlighted. Foremost, TCD results in a measure of global, rather than local perfusion.36 The use of TCD to measure cerebrovascular blood flow makes a key assumption that vessel diameter remains constant throughout testing. Previous studies have demonstrated a decrease in MCA diameter during rhythmic handgrip exercise in humans and during changes in CO2.37,38 However, this was not measured in the current study. Nonetheless, our modelling determined that cerebrovascular reactivity to changes in PETCO2 explained the differences in MCAvmean in pregnant and non-pregnant individuals in response to exercise. Thus, we believe that changes in vessel diameter in response to exercise are likely to be similar in healthy pregnant and non-pregnant populations.

Conclusions

Pregnant women exhibit cerebrovascular adaptations over the course of pregnancy compared to non-pregnant women due to changes in cerebrovascular reactivity. We provide the first evidence that this may decrease the time to peak in PCA blood velocity in response to NVC in the second trimester. Although the change in CBF in response to progressive hypercapnia is similar in pregnant and non-pregnant populations, we have shown that CO2 level and cerebrovascular reactivity explain the altered response of MCA velocity during moderate to vigorous exercise in the second and third trimester.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JCB889089 Supplemetal Material for Longitudinal study of cerebral blood flow regulation during exercise in pregnancy by Brittany A Matenchuk, Marina James, Rachel J Skow, Paige Wakefield, Christina MacKay, Craig D Steinback and Margie H Davenport in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this project is made possible by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant, the Advancing Women’s Heart Health Initiative supported by Health Canada and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. This research was also funded by generous supporters of the Lois Hole Hospital for Women through the Women and Children's Health Research Institute. MHD is funded by a Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC)/Health Canada Improving Heart Health for Women Award, National and Alberta HSFC New Investigator Award.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

MHD, CDS and CM created the study concept and design. RJS, MJ, BAM and PW collected and analyzed the data. BAM conducted the statistical analyses and interpretation. BAM, MHD and CDS prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.

ORCID iD

Margie H Davenport https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5627-5773

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.de Haas S, Ghossein-Doha C, van Kuijk SMJ, et al. Physiological adaptation of maternal plasma volume during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017; 49: 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melchiorre K Sharma R and Thilaganathan B.. Cardiac structure and function in normal pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012; 24: 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstead WM.Cerebral blood flow autoregulation and dysautoregulation. Anesthesiol Clin 2016; 34: 465–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreurs MPH, Houston EM, May V, et al. The adaptation of the blood-brain barrier to vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor during pregnancy. FASEB J 2012; 26: 355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SL, Chapman AC, Sweet JG, et al. Effect of PPARγ inhibition during pregnancy on posterior cerebral artery function and structure. Front Physiol 2010; 1: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdes G, Erices R, Chacon C, et al. Angiogenic, hyperpermeability and vasodilator network in utero-placental units along pregnancy in the guinea-pig (Cavia porcellus). Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2008; 6: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Agency of Canada. Stroke in Canada: highlights from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System. Ottawa (Ontario): Public Health Agency of Canada, www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/stroke-canada-fact-sheet.html (accessed 25 June 2019).

- 8.Swartz RH, Cayley ML, Foley N, et al. The incidence of pregnancy-related stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke 2017; 12: 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James AH, Bushnell CD, Jamison MG, et al. Incidence and risk factors for stroke in pregnancy and the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106: 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bisson M Marc I and Brassard P.. Cerebral blood flow regulation, exercise and pregnancy: why should we care? Clin Sci 2016; 130: 651–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cipolla MJ.The adaptation of the cerebral circulation to pregnancy: mechanisms and consequences. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 465–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman RW, Bowie RA, Henfrey MME, et al. Cerebral haemodynamics in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia as assessed by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. Br J Anaesth 2002; 89: 687–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosengarten B, Gruessner S, Aldinger C, et al. Abnormal regulation of maternal cerebral blood flow under conditions of gestational diabetes mellitus. Ultraschall Med 2004; 25: 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mottola MF, Davenport MH, Ruchat S-M, et al. 2019 Canadian guideline for physical activity throughout pregnancy. Br J Sports Med 2018; 52: 1339–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogoh S and Ainslie PN.. Cerebral blood flow during exercise: mechanisms of regulation. J Appl Physiol 2009; 107: 1370–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe L and Mottola M. Physical activity readiness medical examination for pregnancy: PARmed-X for pregnancy. Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology & Health Canada, http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/publications/parq/parmed-xpreg.pdf (2002, accessed 3 June 2019).

- 17.Expert Advisory Committee of the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology chaired by Dr. N. Gledhill. Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire – PAR-Q. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, http://uwfitness.uwaterloo.ca/PDF/par-q.pdf (2002, accessed 24 June 2019).

- 18.Zeeman GG Hatab M and Twickler DM.. Maternal cerebral blood flow changes in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189: 968–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willie CK, Colino FL, Bailey DM, et al. Utility of transcranial Doppler ultrasound for the integrative assessment of cerebrovascular function. J Neurosci Methods 2011; 196: 221–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaslid R.Visually evoked dynamic blood flow response of the human cerebral circulation. Stroke 1987; 18: 771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duffin BYJ and Mcavoy G V.. The peripheral-chemoreceptor threshold to carbon dioxide in man. J Physiol 1988; 406: 15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casey K Duffin J and McAvoy G V.. The effect of exercise on the central-chemoreceptor threshold in man. J Physiol 1987; 383: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffin J.Measuring the respiratory chemoreflexes in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2011; 177: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borg GA V.Perceived exertion scale. Scand J Rehabil Med 1970; 2: 92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iadecola C.The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron 2017; 96: 17–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brusse IA, van den Berg CB, Duvekot JJ, et al. Visual evoked potentials in women with and without preeclampsia during pregnancy and postpartum. J Hypertens 2018; 36: 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinback CD King EC and Davenport MH.. Longitudinal cerebrovascular reactivity during pregnancy: a case study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2015; 40: 636–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willie CK, Ainslie PN, Taylor CE, et al. Neuromechanical features of the cardiac baroreflex after exercise. Hypertension 2011; 57: 927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davenport MH, Hogan DB, Eskes GA, et al. Cerebrovascular reserve: the link between fitness and cognitive function? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2012; 40: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bor-Seng-Shu E, Kita WS, Figueiredo EG, et al. Cerebral hemodynamics: concepts of clinical importance. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012; 70: 357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ainslie PN and Duffin J.. Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol 2009; 296: R1473–R1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ainslie PN and Burgess KR.. Cardiorespiratory and cerebrovascular responses to hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing: effects of acclimatization to high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2008; 161: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey DM, Marley CJ, Brugniaux J V., et al. Elevated aerobic fitness sustained throughout the adult lifespan is associated with improved cerebral hemodynamics. Stroke 2013; 44: 3235–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas BP, Yezhuvath US, Tseng BY, et al. Life-long aerobic exercise preserved baseline cerebral blood flow but reduced vascular reactivity to CO2. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 38: 1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murrell CJ, Cotter JD, Thomas KN, et al. Cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity at rest and during sub-maximal exercise: effect of age and 12-week exercise training. Age 2013; 35: 905–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purkayastha S and Sorond F.. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound: technique and application. Semin Neurol 2012; 32: 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verbree J, Bronzwaer A, van Buchem MA, et al. Middle cerebral artery diameter changes during rhythmic handgrip exercise in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 2921–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coverdale NS Badrov MB and Kevin Shoemaker J.. Impact of age on cerebrovascular dilation versus reactivity to hypercapnia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 344–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JCB889089 Supplemetal Material for Longitudinal study of cerebral blood flow regulation during exercise in pregnancy by Brittany A Matenchuk, Marina James, Rachel J Skow, Paige Wakefield, Christina MacKay, Craig D Steinback and Margie H Davenport in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism