Abstract

Early-onset cardiomyopathy is a major concern for people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM). Studies examining myocardial deformation indices early in the disease process in people with have provided conflicting results. Accordingly, the objective was to examine left ventricular (LV) function in adolescents with type 1 DM using novel measures of cardiomyopathy, termed ventricular discoordination indices, including systolic stretch fraction (SSF), and our newly developed diastolic relaxation fraction (DRF). Adolescents with DM (n = 16) and healthy controls (n = 20) underwent cardiac MRI (CMR) tissue tracking analysis for standard volumetric and functional analysis. Segment-specific circumferential strain and strain rate indices were evaluated to calculate standard mechanical dyssynchrony and discoordination. SSF and DRF were calculated from strain rate data. There were no global or regional group differences between participants with DM and controls in standard LV strain mechanics. However, youth with DM had lower diastolic strain rate around the inferior septal and free wall region (all p <0.05) as well as higher SSF (p = 0.03) and DRF (p <0.001) compared with controls. None of the CMR indices correlated with HbA1c or diabetes duration. In conclusion, our results suggest that adolescents with DM have LV systolic and diastolic discoordination, providing early evidence of cardiomyopathy despite their young age. The presence of discoordination in the setting of normal LV size and function suggests that the proposed novel discoordination indices could serve as a more sensitive marker of cardiomyopathy than previously employed mechanical deformation indices.

Early-onset cardiomyopathy remains a major concern for people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM).1 Subclinical diastolic dysfunction has been recognized as a strong predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in many populations and can be noninvasively evaluated using echocardiography or cardiac MRI (CMR).2 In children and young adults, early signs of myocardial distress may manifest as diastolic dysfunction or reduced myocardial deformation, well-recognized precursors of diastolic and systolic heart failure, respectively.3,4 However, the echo-based approaches are currently limited to 2-dimensional regional quantitative evaluation of myocardial function.5 Recently, LV systolic and diastolic mechanical dyssynchrony and discoordination measures have been developed using CMR to investigate global intra- and interventricular myocardial efficiency.6−12 Additionally, ventricular discoordination and electro-mechanical dyssynchrony have been associated with clinical functional status and exercise tolerance.6,13 Accordingly, the objective of this study was to use CMR to investigate LV function in adolescents with DM using circumferential strain and strain rate, conventional strain-derived LV intraventricular mechanical dyssynchrony (M-Dys), the more recently developed systolic stretch fraction (SSF) index, along with a novel ventricular discoordination index we developed, entitled diastolic relaxation fraction (DRF).14 Specifically, we aimed to investigate whether differences in LV mechanical coordination are found in adolescents with DM compared with normal control adolescents.

Methods

As a part of the EMERALD study (Effects of MEtformin on cardiovasculaR function in AdoLescents with type 1 Diabetes),15 16 adolescents with DM underwent comprehensive baseline CMR for cardiac functional evaluation. Detailed description of the participants and study design has already been published.15 Briefly, inclusion criteria were: age 12 to 21 years, Tanner stage >1, diabetes duration ≥1 year, blood pressure (BP) <140/90 mm Hg, HbA1c < 12%, nonsmoking, weight <300 lbs, and no medications affecting BP or insulin sensitivity. Twenty control participants were recruited prospectively per institutional advertisement to investigate the normal CMR parameters in adolescents. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple-Institutional Review Board and all participants and guardians provided written assent and/or consent as appropriate for given age. All participants underwent CMR evaluation using a previously described protocol.15

LV myocardial deformation analysis including circumferential strain and strain rate analysis was performed as described previously.10,13 Briefly, cine images were imported into the tissue tracking module of CVI42 platform (Version 5.9.1, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, AB, Canada). The LV myocardium was standardly parceled into the American Heart Association 16-segment model. Semiautomatic contouring of the LV endocardial and epicardial borders generated circumferential strain (ε(t)) and strain rate (SR = dε(t)/dt) curves for each segment. Peak circumferential strain and peak systolic and diastolic SR were registered from each curve along with global circumferential strain (GCS). Lastly, conventional LV intraventricular mechanical dyssynchrony (M-Dys) was calculated as a standard deviation of all time-to-peak circumferential strain values.

We calculated novel markers of ventricular discoordination, entitled SSF. Originally described by Kirn et al7 and later modified by Janou sek et al,8 SSF utilizes myocardial segment-specific strain and strain rate curves in order to calculate the relative ratio of myocardial contraction to myocardial relaxation within a defined period of the cardiac cycle. Under ideal conditions, all of the LV myocardial segments are in the ejection phase, experiencing contraction, as represented by a negative strain rate (dε(t)/dt−). In the setting of LV myocardial discoordination, some segments are instead undergoing myocardial relaxation, whereas others are undergoing contraction, described by positive strain rate (dε(t)/dt+).

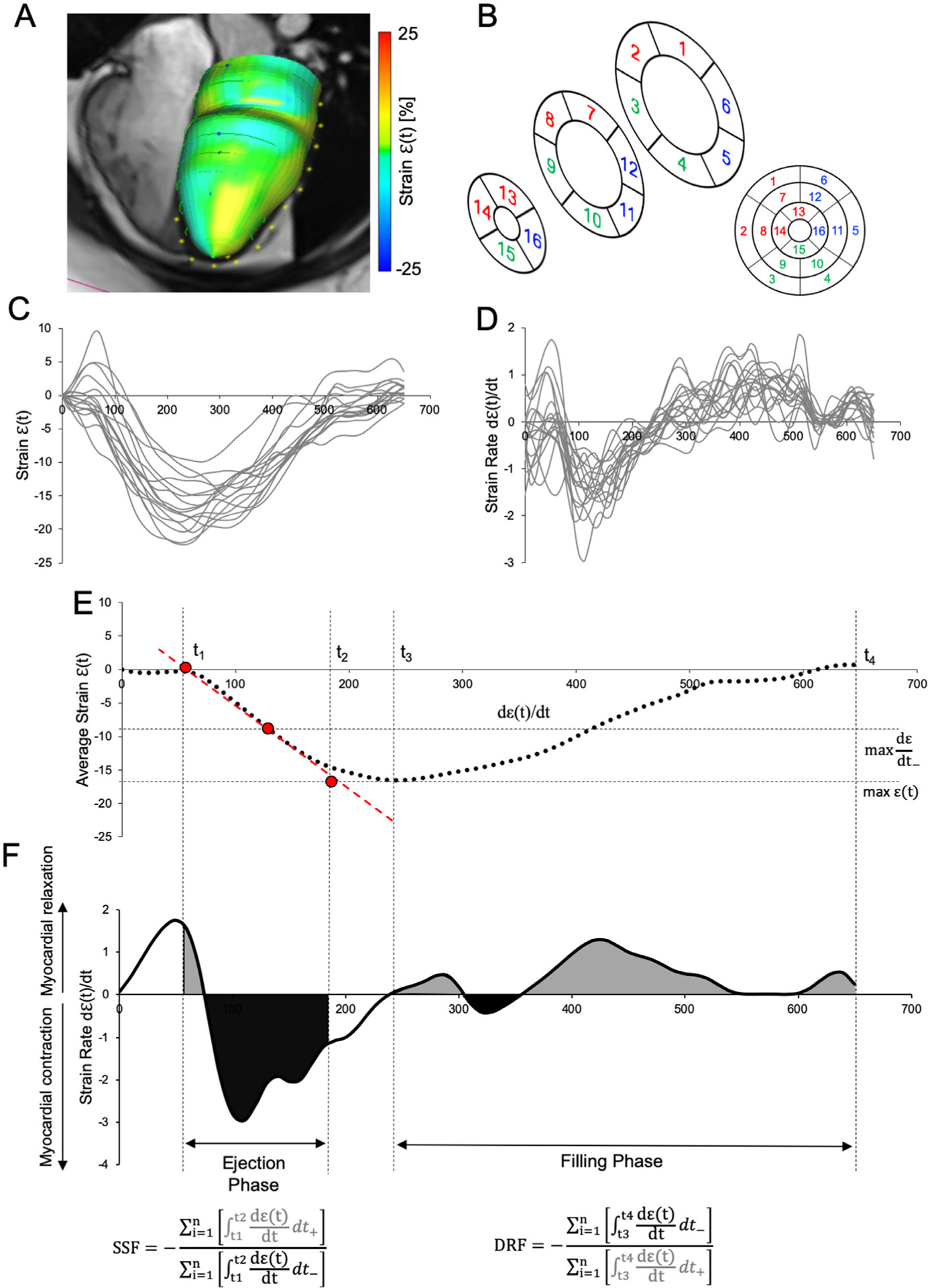

The postprocessing algorithm of ε(t) and dε(t)/dt curves yielding SSF is depicted in Figure 1. A standardization mean ε(t) curve was generated in order to identify time boundaries defining LV ejection and filling phases. This was achieved as described previously,14 by calculating the intercept of a tangent line representing the maximum negative dε(t)/dt with the minimum and maximum values on generated mean ε(t) curve yielding the beginning of ejection time and end-ejection, respectively. Filling phase was defined from the time of maximum mean ε(t) to the end of the cardiac cycle. As a next step, dε(t)/dt curves for each American Heart Association segment were separated into their negative dε(t)/dt− and positive dε(t)/dt+ components, representing myocardial contraction and relaxation, respectively. SSF was then calculated as described previously, as a ratio of summed integrated positive and negative dε(t)/dt components:

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of the postprocessing algorithm of CMR for the left ventricular (LV) discoordination indices. (A) LV endocardial and epicardial segmentation-generated 3D-circumeferential strain model which was then parceled (B) to standardized 16-American Heart Association model, and segment-specific (C) strain ε(t) and strain rate (dε(t)/dt) (D) curves were then generated. (E) Mean ε(t) was calculated to define the temporal boundary condition defining the ejection and filling phases. (F) The actual calculation of systolic stretch fraction (SSF) and diastolic relaxation fraction (DRF) required separation of the dε(t)/dt curves into positive and negative components with subsequent integration and summation to arrive at the final ratio.

In order to assess for mechanical discoordination during the LV diastole, we extended the principle behind the SSF calculation further to the filling phase. We propose to utilize a novel metric inversely titled DRF as recently described by Frank & Schäfer,14 which calculates the ratio of myocardial contraction (dε(t)/dt−) to relaxation (dε(t)/dt+) during the ventricular filling phase and is mathematically defined as:

Analyses were performed in Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Continuous variables were checked for the distributional assumption of normality using normal plots, in addition to Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro Wilks tests. Variables that were positively skewed (eg, SSF and DRF indices) were natural log-transformed for the correlative analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics among adolescents with DM and controls were compared using Student’s t test for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed variables, and chi-square for categorical variables. Simple linear regression analyses were used to examine associations between HbA1c and diabetes duration with LV discoordination measures.

Results

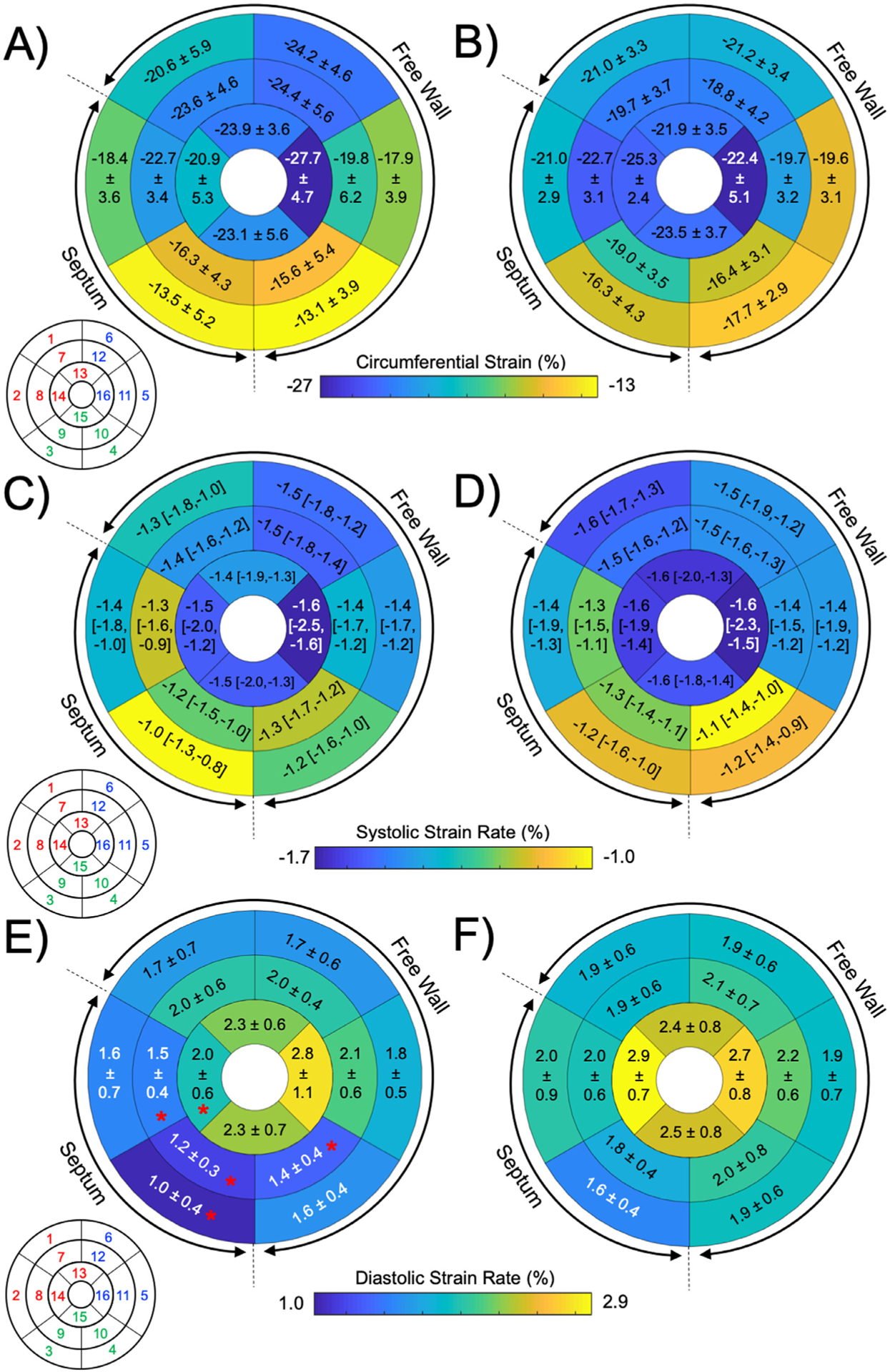

Participant characteristics and CMR hemodynamics are summarized in Table 1. There were no differences between participants with DM and controls in terms of age (p = 0.08), sex distribution (p = 0.523), or BMI z-score (p = 0.13). Furthermore, there were no group differences in LV volumes, ejection fraction, cardiac index, or mass. Analysis of global LV circumferential strain (LV GCS) is summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. There were no differences in maximal LV GCS between groups (p = 0.84). Comparative analysis of segment-specific myocardial deformation indices including maximal circumferential strain and SR is depicted in Figure 2. There were no regional differences in maximal LV circumferential strain between participants with DM and controls. Similarly, there were no differences between maximal systolic SR (dε(t)/dt) in any LV segments. On the other hand, participants with DM had a lower maximal diastolic SR (dε(t)/dt+) in segments 8 and 14, corresponding to the inferiorseptal region at the mid-papillary and apical portion of the LV (all p <0.05). Furthermore, maximal diastolic SR was also lower in the DM group in the nearby LV segments 3, 9, and 10, representing the inferior and lateral free-wall at the basal and mid-papillary levels (all p <0.05).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and MRI left ventricular hemodynamics

| Variable | DM (n = 16) | Control (n = 20) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 16.5 ± 3.1 | 14.7 ± 2.6 | 0.08 |

| Girls | 7 (44%) | 12 (60%) | 0.53 |

| BM1 z-score | 0.94 ± 1.1 | 0.44 ± 0.58 | 0.13 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 7.9 ± 4.5 | ||

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 87 ± 17 | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 68 ± 11 | 72 ± 14 | 0.33 |

| End-diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 84 ± 16 | 84 ±22 | 0.97 |

| End-systolic volume index (mL/m2) | 33 ± 9 | 31 ± 10 | 0.54 |

| Stroke volume index (mL/m2) | 51 ± 11 | 53 ± 14 | 0.63 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 61 ± 7 | 64 ± 4 | 0.17 |

| Cardiac mass (L/min/m2) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 0.45 |

| Ventricular mass (g) | 81 ± 19 | 82 ± 21 | 0.88 |

All values are reported as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range.

Table 2.

Left ventricular mechanics

| Variable | DM (n = 16) | Control (n = 20) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical dyssynchrony (ms) | 15 (12 – 22) | 15 (10–17) | 0.28 |

| Global circumferential strain (%) | −19.2 ± 2.3 | −20.1 ± 2.1 | 0.84 |

| Systolic stretch fraction (*102) | 3.6 (1.9 – 5.4) | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 0.03 |

| Diastolic relaxation fraction | 0.36 (0.33 – 0.42) | 0.30 (0.29–0.33) | <0.001 |

Values reported as median with corresponding interquartile range or mean ± SD.

Figure 2.

Comparison of regular myocardial deformation indices in participants with type 1 diabetes (DM) and controls. Maximal circumferential strain values were not different between (A) participants with DM and (B) controls. Similarly, there were no differences in maximal systolic (positive) strain rate between the (C) DM group and (D) controls. Patients with (E) DM had reduced maximal diastolic (negative) strain rate at segments 3, 8, 9, 10, and 14, compared with (F) controls.

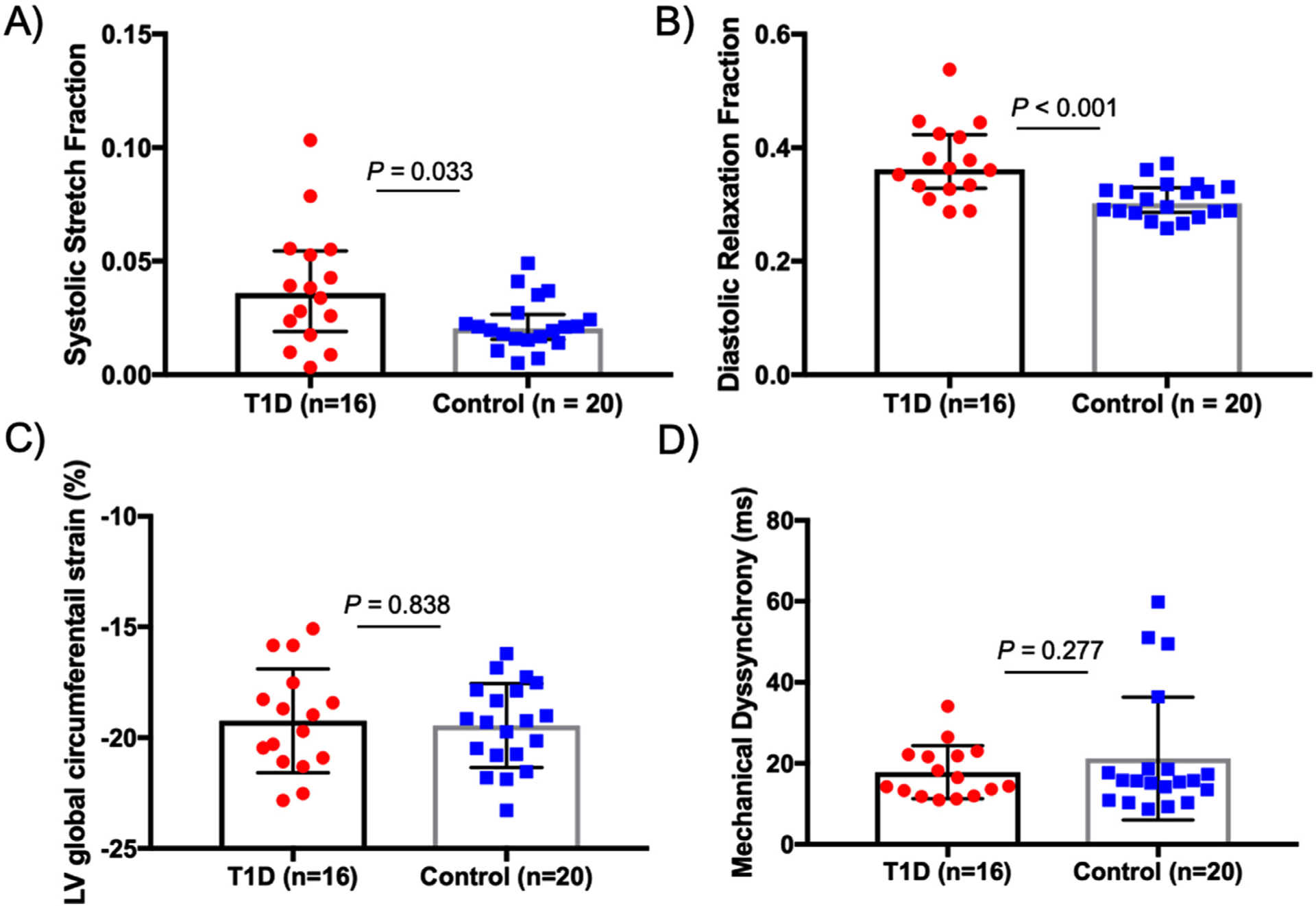

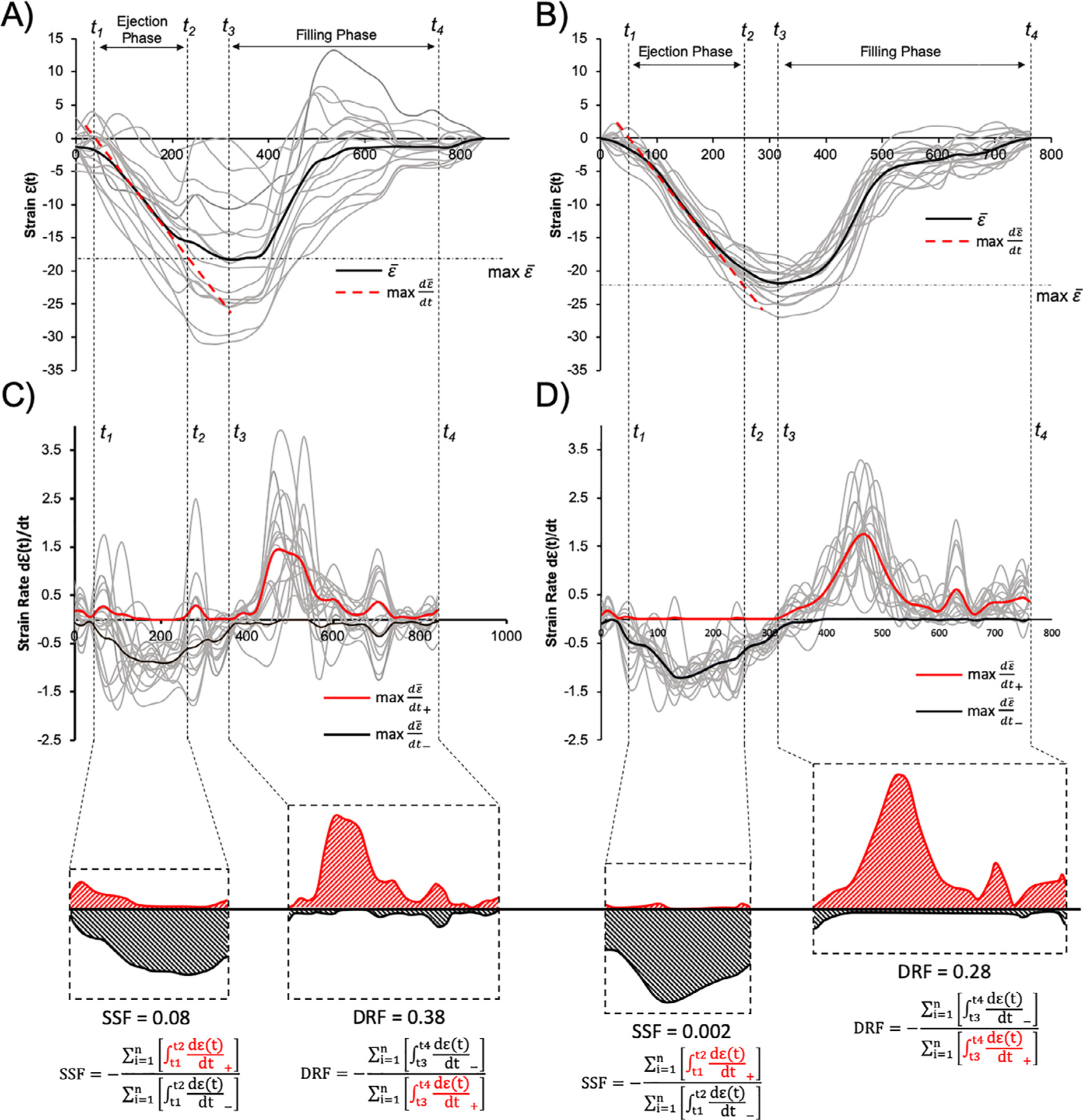

Analysis of the LV mechanical dyssynchrony and discoordination indices are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 3. There were no differences in the standard mechanical dyssynchrony measure, M-Dys, between groups (p = 0.28). However, participants with DM had both higher median (IQR) SSF (p = 0.03) and DRF (p <0.001) compared with controls, showing systolic and diastolic mechanical discoordination, respectively. A representative example comparing LV coordination between participants with DM and controls is portrayed in Figure 4. There was a higher proportion of positive SR – dε(t)/dt+ datapoints during the ejection phase in people with DM compared with the controls. Similarly, there was a higher ratio of negative SR dε(t)/dt− datapoints during the diastolic filling phase in participants with DM. Interobserver analysis for SSF analysis between 2 independent readers (M.S. and D.E.) revealed minimal bias (0.002 with 95% limits agreement from −0.031 to 0.032, with a correlation coefficient of 0.84).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of LV mechanical discoordination and dyssynchrony results. (A) Systolic stretch fraction (SSF) was elevated in participants with type 1 diabetes (DM), (B) as was diastolic relaxation fraction (DRF). (C) There were no group differences in (C) left ventricular global circumferential strain (LV GCS) or (D) conventional mechanical dyssynchrony as evaluated by time-to-peak analysis.

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of representative A) T1D and B) control strain curves. Resulting systolic stretch fraction (SSF) and diastolic relaxation fraction (DRF) calculations are depicted for respective C) T1D and D) control participants. Note that color highlighted positive and negative strain rate curves represent the global average for graphical representation purposes but were not statistically compared.

Lastly, correlative analysis between HbA1c and diabetes duration with the markers of LV dyssynchrony is summarized in Table 3. We did not observe any significant correlations between the considered metrics.

Table 3.

Associations between left ventricular mechanics, HbA1c, and diabetes duration

| Variable | HbAlc (per 1%) | Diabetes duration (per 1 year) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | p Value | β ± SE | p Value | |

| Mechanical dyssynchrony (ms) | 0.43 ± 0.99 | 0.67 | −0.01 ± 0.39 | 0.93 |

| Global circumferential strain (%) | 0.16 ± 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.14 ± 0.13 | 0.33 |

| Systolic stretch fraction | −0.02 ± 0.14 | 0.89 | −0.05 ± 0.05 | 0.35 |

| Diastolic relaxation fraction | −0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.59 |

Data reported as beta values ± SE.

Discussion

Abnormal LV myocardial deformation is a well described early component of DM-related cardiomyopathy, recognizable already in children and young adults.16,17 In this study, we found that (1) adolescents with DM have LV systolic and diastolic discoordination in the setting of normal ventricular size and systolic function, (2) early signs of diastolic dysfunction were present in adolescents with DM as evidenced by reduced diastolic SR, and (3) myocardial dyssynchrony and discoordination were not correlated with glycemic control (HbA1c) or diabetes duration. Ventricular discoordination is an increasingly recognized marker of myocardial dysfunction with considerable prognostic value in detection of adverse clinical outcomes.12 In this study, we introduce a novel marker ventricular diastolic discoordination, DRF, which evaluates the efficiency and dynamics of LV myocardial relaxation. This novel marker was able to detect differences in adolescents with DM versus control adolescents, despite their young age, and thus holds potential as a sensitive marker of cardiac dysfunction in youth.

The concept of LV mechanical discoordination was originally introduced to improve the understanding of the relation between electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony. Unlike the conventional mechanical dyssynchrony addressed by time-to-peak analysis, discoordination indices such as SSF and DRF are more reflective of myocardial contractile and relaxation efficiency with respect to the phase of cardiac cycle.7,9 Consequently, one can assess the amount of mechanically wasted active and passive myocardial energy during systole and diastole, respectively. Neither mechanical nor electrical dyssynchrony have been previously investigated in DM. Both abnormal metabolic control and autonomic dysfunction have been postulated to impact structural myocardial remodeling including the conduction system but the exact mechanism underlying remodeling is unknown.18 Unlike some reports using echocardiographic strain or Doppler indices,16,19,20 we did not observe a relation between the discoordination measures and HbA1c or diabetes duration. Poor myocardial contractile efficiency from LV mechanical discoordination may limit exercise performance21 and could contribute to the low VO2 peak we previously reported in DM adolescents.

The primary imaging modality for the assessment of LV systolic function in this population has been echocardiography with speckle tracking. However, the literature comparing various types of strain indices in youth with DM is inconsistent. The classical early sign of LV systolic dysfunction evident by noninvasive imaging is a reduction in longitudinal strain as explained by the subendocardial location of the LV longitudinal fibers, which are thought to be most susceptible to ischemic injury.22 Indeed, reduced LV global longitudinal strain and SR from echocardiographic speckle tracking have been reported in children and adolescents with DM.3,4 Furthermore, decreased longitudinal strain in DM has previously been associated with poor glycemic control.19,20 In contrast, in a recent study in youth with DM, our group reported reduced circumferential strain in a larger group of sedentary adolescents with DM versus sedentary controls from echocardiographic speckle tracking, while the longitudinal strain remained preserved.23 These results were partially confirmed in a large study by Bradley et al, describing simultaneously reduced longitudinal and circumferential strain in adolescents with DM.4 On the other hand, our CMR-based study and some other echocardiography-based studies report preserved LV circumferential strain and SR indices.19,20 These discrepancies may be partially explained by short-term metabolic changes influencing LV systolic performance, to differences in habitual physical activity, different image postprocessing techniques, or sample size limitations. Furthermore, Hensel et al reported that temporarily increased blood glucose values led to increases in LV circumferential and longitudinal strain.17

Inconsistent results also exist in studies investigating subclinical LV diastolic dysfunction. Normal LV inflow values provided by standard Doppler echocardiography have been shown in the majority of pediatric studies,4,19,23 with abnormal values demonstrated in a few studies.24,25 The most consistent marker of diastolic dysfunction throughout the literature to date is an elevated E/e’ ratio.2,5,26 However, this marker is recognized to poorly predict elevated LV pressures.27 Di Cori et al further reported an association between tissue Doppler indices and diabetes duration in young adults with DM.16 In the current study, we observed reduced LV diastolic circumferential SR, interestingly clustered around the inferior septal and free wall region. We speculate that regional diastolic SR might be a sensitive marker of early LV restrictive remodeling in youth with DM, but larger studies optimally utilizing 3D rather than 2-D-echocardiography are warranted to support our preliminary results.

We would like to acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, our small CMR sample size limited further exploration the relation between discoordination indices and other potential contributors. Second, the effect of CMR-related temporal resolution on the calculation of discoordination indices is unknown. However, CMR-based tissue/feature tracking is a well-validated technique broadly used in research imaging.28 Since the SSF calculation was previously only applied to right ventricular discoordination in smaller group of patients with tetralogy of Fallot, we lack an appropriate quantitative comparison group. Similarly, DRF calculation was applied for the first time in the present study, and its validation and accuracy are warranted in future larger studies using other CMR techniques assessing myocardial deformation. In general, we consider this initial study on LV discoordination preliminary and hypothesis generating, and encourage replication in larger sample sizes with other imaging modalities as well as longitudinal studies to determine the long-term implications of our findings.

In conclusion, our results suggest that adolescents with DM have both LV systolic and diastolic discoordination, supporting the concept of early-onset cardiomyopathy in this at-risk population. Importantly, the presence of discoordination in the setting of normal LV size and function may imply a role for discoordination indices as an early screening marker which may be more sensitive than regular mechanical deformation indices. CMR could potentially provide comprehensive noninvasive ventricular functional and volumetric evaluation in young people with DM, which could complement standard echocardiographic studies.

Funding:

This study was supported by a generous gift from the Rady Family Foundation and Jayden DeLuca Foundation. A.J.B. is supported in part by NIH K25HL119608 and R01HL133504.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2010;11:31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flachskampf FA, Biering-Sørensen T, Solomon SD, Duvernoy O, Bjerner T, Smiseth OA. Cardiac imaging to evaluate left ventricular diastolic function. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:1071–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suys BE, Katier N, Rooman RPA, Matthys D, Beeck LOL De, Caju MVL Du, Wolf D De. Female children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes have more pronounced early echocardiographic signs of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1947–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley TJ, Slorach C, Mahmud FH, Dunger DB, Deanfield J, Deda L, Elia Y, Har RLH, Hui W, Moineddin R, Reich HN, Scholey JW, Mertens L, Sochett E, Cherney DZI. Early changes in cardiovascular structure and function in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2016;15:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragulescu A, Mertens L, Friedberg MK. Interpretation of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in children with cardiomyopathy by echocardiography: problems and limitations. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumens J, Steve Fan CP, Walmsley J, Yim D, Manlhiot C, Dragulescu A, Grosse-Wortmann L, Mertens L, Prinzen FW, Delhaas T, Friedberg MK. Relative impact of right ventricular electromechanical dyssynchrony versus pulmonary regurgitation on right ventricular dysfunction and exercise intolerance in patients after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirn B, Jansen A, Bracke F, Gelder B van, Arts T, Prinzen FW. Mechanical discoordination rather than dyssynchrony predicts reverse remodeling upon cardiac resynchronization. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol 2008;295:H640–H646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janou sek J, Kovanda J, Lo zek M, Tomek V, Vojtovi c P, Gebauer R, Kubu s P, Krej c ı r M, Lumens J, Delhaas T, Prinzen F. Pulmonary right ventricular resynchronization in congenital heart disease: acute improvement in right ventricular mechanics and contraction efficiency. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell K, Eriksen M, Aaberge L, Wilhelmsen N, Skulstad H, Gjesdal O, Edvardsen T, Smiseth OA. Assessment of wasted myocardial work: a novel method to quantify energy loss due to uncoordinated left ventricular contractions. AJP Heart Circ Physiol 2013;305:H996–H1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schäfer M, Browne LP, Alvensleben JC von, Mitchell MB, Morgan GJ, Ivy DD, Jaggers J Ventricular interactions and electromechanical dyssynchrony after ross and Ross-Konno operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;158:509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang CL, Wu CT, Yeh YH, Wu LS, Chang CJ, Ho WJ, Hsu LA, Luqman N, Kuo CT. Recoordination rather than resynchronization predicts reverse remodeling after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fudim M, Liu PR, Shaw L, Hess P, James O, Borges-Neto S. The prognostic value of diastolic and systolic mechanical left ventricular dyssynchrony among patients with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schäfer M, Collins KK, Browne LP, Ivy DD, Abman S, Friesen R, Frank B, Fonseca B, DiMaria M, Hunter KS, Truong U, Alvensleben JC von. Effect of electrical dyssynchrony on left and right ventricular mechanics in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank B, Schäfer M, Douwes JM, Ivy DD, Abman SH, Davidson JA, Burzlaff S, Mitchell MB, Morgan GJ, Browne L, Barker AJ, Truong U, Alvensleben JC Von. Novel measures of left ventricular electromechanical discoordination predict clinical outcomes in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol 2019;318:401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjornstad P, Schäfer M, Truong U, Cree-Green M, Pyle L, Baumgartner A, Garcia Reyes Y, Maniatis A, Nayak S, Wadwa RP, Browne LP, Reusch JEB, Nadeau KJ. Metformin improves insulin sensitivity and vascular health in youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2018;138:2895–2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cori A Di, Bello V Di, Miccoli R, Talini E, Palagi C, Delle Donne MG, Penno G, Nardi C, Bianchi C, Mariani M, Prato S Del, Balbarini A Left ventricular function in ormotensive young adults with well-controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hensel KO, Grimmer F, Jenke AC, Wirth S, Heusch A. The influence of real-time blood glucose levels on left ventricular myocardial strain and strain rate in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus—a speckle tracking echocardiography study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2015;15:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grisanti LA. Diabetes and arrhythmias: pathophysiology, mechanisms and therapeutic outcomes. Front Physiol 2018;9:1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labombarda F, Leport M, Morello R, Ribault V, Kauffman D, Brouard J, Pellissier A, Maragnes P, Manrique A, Milliez P, Saloux E. Longitudinal left ventricular strain impairment in type 1 diabetes children and adolescents: a 2D speckle strain imaging study. Diabetes Metab 2014;40:292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altun G, Babaoğlu K, Binnetoğlu K, Özsu E, Yeşiltepe Mutlu RG, Ş Hatun. Subclinical left ventricular longitudinal and radial systolic dysfunction in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Echocardiography 2016;33:1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadeau KJ, Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA, Brown MS, Dorosz JL, Hull A, Zeitler P, Draznin B, Reusch JEB. Insulin resistance in adolescents with type 1 diabetes and its relationship to cardiovascular function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:513–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokke TM, Hasselberg NE, Smedsrud MK, Sarvari SI, Haugaa KH, Smiseth OA, Edvardsen T, Remme EW. Geometry as a confounder when assessing ventricular systolic function: comparison between ejection fraction and strain. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:942–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjornstad P, Truong U, Pyle L, Dorosz JL, Cree-Green M, Baumgartner A, Coe G, Regensteiner JG, Reusch JEB, Nadeau KJ. Youth with type 1 diabetes have worse strain and less pronounced sex differences in early echocardiographic markers of diabetic cardiomyopathy compared to their normoglycemic peers: a RESistance to inSulin in type 1 ANd type 2 diabetes (RESISTANT) study. J Diabetes Complic 2016;30:1103–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoldaş T, Örün UA, Sagsak E, Aycan Z, Kaya Ö, Özgür S, Karademir S Subclinical left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction in type 1 diabetic children and adolescents with good metabolic control. Echocardiography 2018;35:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salem M, Behery S El, Adly A, Khalil D, Hadidi E El. Early predictors of myocardial disease in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes 2009;10:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth O, Waggoner AD, Flachskampf F, Pellikka P, Evangelista A. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22: 107–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, Miller FA, Oh JK, Redfield MM, Tajik AJ. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures a comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study. Circulation 2000;102:1788–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuster A, Hor KN, Kowallick JT, Beerbaum P, Kutty S. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial feature tracking: concepts and clinical applications. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]