Abstract

In a meta-analysis of three GWAS for susceptibility to Kawasaki disease (KD) conducted in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan and follow-up studies with a total of 11,265 subjects (3428 cases and 7837 controls), a significantly associated SNV in the immunoglobulin heavy variable gene (IGHV) cluster in 14q33.32 was identified (rs4774175; OR = 1.20, P = 6.0 × 10−9). Investigation of nonsynonymous SNVs of the IGHV cluster in 9335 Japanese subjects identified the C allele of rs6423677, located in IGHV3-66, as the most significant reproducible association (OR = 1.25, P = 6.8 × 10−10 in 3603 cases and 5731 controls). We observed highly skewed allelic usage of IGHV3-66, wherein the rs6423677 A allele was nearly abolished in the transcripts in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of both KD patients and healthy adults. Association of the high-expression allele with KD strongly indicates some active roles of B-cells or endogenous immunoglobulins in the disease pathogenesis. Considering that significant association of SNVs in the IGHV region with disease susceptibility was previously known only for rheumatic heart disease (RHD), a complication of acute rheumatic fever (ARF), these observations suggest that common B-cell related mechanisms may mediate the symptomology of KD and ARF as well as RHD.

Subject terms: Disease genetics, Inflammatory diseases

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis syndrome characterized by high fever, bilateral conjunctivitis, polymorphous skin rash, reddening of lips and oral cavity, changes in extremities and nonsuppurative cervical lymphadenopathy [1] and predominantly affects infants and children younger than 5 years [2]. In many cases, KD is self-limiting. However, it causes coronary artery complications such as dilatations and aneurysms (coronary artery lesions; CALs) in 20–25% of untreated patients [3]. Replacing acute rheumatic fever (ARF), KD is now the leading cause of acquired heart diseases of children in developed countries [4]. Most KD patients are treated with high dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion combined with oral aspirin, which was established in the 1980s and 1990s and has become a standard treatment that is effective at resolving inflammation and reducing CALs [5–7]. However, the mechanism of IVIG action on KD has not been revealed, and 10–15% of KD patients do not respond to the treatment and have a higher risk for CAL. Recently a series of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) revealed several definitive KD susceptibility loci [8–10]. However, these genetic factors can explain only a part of the etiology. Also, the reason for the high incidence among East Asian children [11], which is up to 20-fold higher than those in Western countries and is a crucial epidemiologic feature of KD, has not yet been explained. It might be attributed in part to lack of statistical power in the previous GWAS analyses that were carried out using modest sample-sizes, and therefore, many common genetic factors with relatively low penetrance may have gone undetected. In this study, to identify novel susceptibility loci for KD, we conducted a meta-analysis of GWAS from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, the three countries with the highest incidence of KD in the world.

Materials and methods

Subjects and design of association analyses in identifying novel susceptibility loci for KD

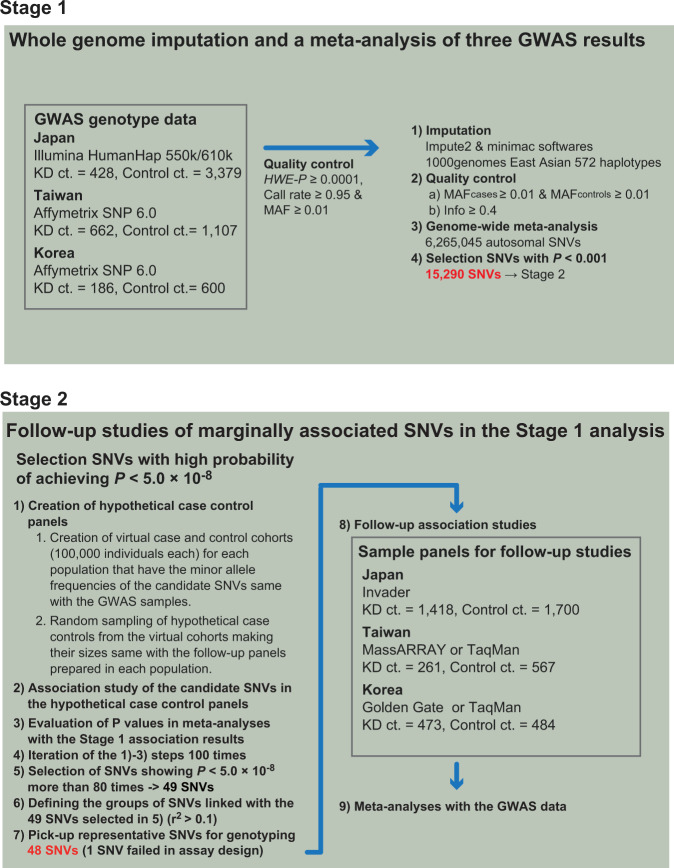

In this study, susceptibility loci for KD were screened and verified in a two-stage association analysis (Fig. 1). Stage 1 was a whole-genome meta-analysis of results from GWAS conducted in Japan [9], Taiwan [10], and Korea [12] involving 6362 individuals. We carried out follow-up association studies using three case-control panels comprised of 1418 KD patients and 1700 controls (Japanese), 473 KD patients and 484 controls (Korean) and 261 KD patients and 567 controls (Taiwanese) independent from the subjects in the GWAS and performed meta-analyses with the Stage 1 results (Stage 2). Loci for the follow-up studies were selected based on their predicted potential to achieve P values less than 5.0 × 10−8 in the meta-analyses, with the prediction made by iterative simulations of follow-up studies with virtual case and control cohorts (detailed below). To further validate the associations of rs4774175 and rs6423677 in 14q32.33, an additional 1758 KD cases and 653 controls collected in Japan were used. The number of KD cases and controls, as well as platforms in the three previous GWAS and follow-up studies in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow of the screening of the novel susceptibility loci for KD in this study

Whole-genome imputation and meta-analyses

For the Stage 1 analysis, each study center’s genotype data for the Illumina Human Hap550/610 or Affymetrix SNP 6.0 arrays (Supplementary Table 1) was oriented to the forward strand of the hg19 human reference genome. Genotype data were filtered for minimum quality-control parameter cutoffs such as HWE-P ≥ 0.0001, Call-rate ≥0.95, and minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.01. Each study center performed whole-genome imputation of autosomal variants with 572 East Asian haplotypes from the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 1 Version 3 (ref. [13]) as reference using pre-phasing with SHAPEIT v1 (ref. [14]) and imputation with IMPUTE2 and minimac softwares [15, 16].

Imputed genotype data were analyzed by each study center in a case-control logistic regression analysis, and the output was merged in the R statistics environment (URL: https://www.R-project.org/) and filtered for variants that were polymorphic in both cases and controls (MAFcases ≥0.01 and MAFcontrols ≥0.01) and had info ≥0.4 in all three studies’ dataset; there were 6,265,045 SNVs in the final filtered dataset. A fixed-effects meta-analysis of the three data sets’ beta-coefficients and standard errors was performed using the R package metafor (https://cran.r-project.org/package=metafor).

Linkage disequilibrium-based region definition

Each chromosome’s SNVs were filtered for those with a meta-analysis P < 0.01 and then labelled based on linkage disequilibrium to regional “top SNVs”. Briefly, SNVs with P < 1 × 10−4 were sorted by P value, the top SNV identified, and any SNVs within ±5 Mb that had r2 > 0.1 to that top SNV assigned to its region; data on a chromosome was processed as such until no SNVs with P < 1 × 10−4 were remaining. Each top SNV region was labelled based on chromosome and minimum and maximum positions of the linked SNVs. Based on that process, each region label would be unique, but regions could overlap with each other. Calculation of r2 was performed using the ld function in the R Bioconductor snpStats package using East Asian genotype data from the 1000 Genomes Phase 1 Version 3 release.

P value simulation

For simplicity, we will refer to the regions of nominally linked SNVs described above as “loci”. To perform the Stage 2 follow-up study efficiently, loci that had a high potential of achieving P values less than 5.0 × 10−8 in a meta-analysis of Stage 1 and 2 results were selected by P value simulation as follows. For each locus, we first selected any nominally associated SNVs (P < 0.001) identified in the Stage 1 analysis, and for each SNV created a virtual set of 100,000 case genotypes and a virtual set of 100,000 control genotypes for each of the three Stage 1 case-control panels. Each virtual set was generated based on the genotype frequencies observed in that panel’s Stage 1 cases or controls at a particular SNV, and each of those virtual sets was then re-sampled in R to randomize their order. Each virtual case and control set was then sampled 100 times to create 100 virtual case-control cohorts; the numbers of cases and controls sampled from the virtual genotype sets were the case-control counts that were expected in the three collaborators’ follow-up studies (RIKEN in Japan: ncases = 1300, ncontrols = 1300; Academia Sinica in Taiwan: ncases = 500, ncontrols = 2000; Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan in Korea: ncases = 412, ncontrols = 600). For each iteration, associations of the candidate SNVs were evaluated in a meta-analysis of the virtual cohorts and the three GWAS data sets. For each candidate SNV, the frequency of observing P values of 5.0 × 10−8 or smaller in 100 iterations of the simulated meta-analysis was scored as the simulation score. Loci with at least one SNV having simulation scores of 0.8 or higher were considered to be promising, and for de novo genotyping, a representative SNV was selected for which assays were designable across the different platforms employed in each research center (Invader in Japan, Sequenom MassARRAY or TaqMan in Taiwan and VeraCode GoldenGate Genotyping kit or TaqMan in Korea, respectively) (Supplementary Table 1).

Genotyping of SNVs in IGHV genes

Nonsynonymous SNVs in IGHV genes were genotyped basically by the Invader Assay. Primers and the probes were carefully designed in order to ensure specificity of the assay. We refrained from using multiplex PCR to avoid both expected and unexpected nonspecific amplification of DNA fragments of high sequence homology which will allow cross reaction between amplicons and probes for different loci. Sequences of the primers and probes for 18 nonsynonymous SNVs in IGHV genes and rs4774175, as well as representative genotyping results of rs6423677, are provided in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1, respectively.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of IGHV repertoires

Two milliliters of venous blood was drawn from patients who were admitted to the hospitals for KD at four time points including (1) acute phase before receiving IVIG (3–8 illness days), (2) 48 h after the patients became afebrile (8–18 illness days), (3) the first follow-up visit to the pediatric clinic after discharge (17–50 days after the disease onset), and (4) the second follow-up visit to the pediatric clinic after discharge (3–4 months after the disease onset). Blood samples were collected into Vacutainer CPT Cell Preparation Tube (BD) and mononuclear cells were separated according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Total RNA from the mononuclear cells was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). 1.0 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed with PrimeScript (TAKARA) and the mixed oligonucleotides of random hexamer and oligo-dT primers. Isotype-specific libraries for NGS were prepared as follows. Mixed forward primers covering the framework region 1 of 7 subgroups of IGHV genes (V1-V7) [17] and reverse primers specific to each IGHC gene for IgM, IgD, IgG, and IgA (including a partial Illumina adapter sequence in the 5′ ends of both primers) were designed for the 1st round PCR. Sequences of the primers are provided in Supplementary Table 4. 6-base barcode sequence and the full Illumina adapter sequence were added at 5′ and 3′ ends of the immunoglobulin amplicons in the 2nd round PCR. The barcode sequences were used to distinguish the patients and the sampling time points. The libraries were sequenced with MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle) (Illumina).

Forward and reverse sequence reads were merged by using FLASh software [18]. Sequences unmerged due to insufficient overlapping length were excluded from subsequent analyses. Merged sequence reads were classified into isotypes and subclasses based on primer sequences by using blast software (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and then quality filtering and removing the primer sequence were performed by using the FASTX-Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html).

Repertoire analyses of immunoglobulin heavy chains

Immunoglobulin repertoires were determined by migmap-1.0.2 software (https://github.com/mikessh/migmap). Sequence reads that terminated prematurely or had a complementarity determining region (CDR) 3 that was non-canonical (i.e., lacking consensus amino acids at both ends or not fully mapped) were excluded from subsequent analyses. Clonotypes were defined by combinations of IGHV, IGH diversity (IGHD), and IGH joining (IGHJ) gene alleles. Correlation trend between the proportions of the IGH clonotypes using IGHV3-66 and the C allele counts at rs6423677 was evaluated by the Jonckheere-Terpstra test using R package PMCMR (https://cran.r-project.org/package=PMCMR). Change of each clonotype proportion from baseline (the 1st sampling point) was calculated by subtracting the baseline proportion from those at 2nd, 3rd, and 4th points. The diversity of CDR3 clonotypes was evaluated by the inverse Simpson’s index using the R package vegan (https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan).

Results

Significant associations in the meta-analyses of three GWAS data sets

In the Stage 1 analysis, a meta-analysis of three GWAS data sets, genome-wide level associations were seen in known susceptibility loci such as FAM167A-BLK (rs2736340; P = 1.23 × 10−16), ITPKC (rs28493229; P = 3.07 × 10−9), CASP3 (rs2720377; P = 2.66 × 10−9) and CD40 (rs1883832; P = 1.76 × 10−8). Four top SNVs in HLA class III~ class II regions (rs2844485, rs73729123, rs7739458, and rs146650659) and rs13330932 in the 16q24.1 region also showed significant associations (Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Fig. 2). From a standard test for inflation, the genomic control inflation factor λGC = 1.0216 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Follow-up of analyses of 49 most promising loci

In a simulation of meta-analyses, a “simulation score” was calculated for each nominally associated SNV (P ≤ 0.001; see Methods). Forty-nine loci were identified with one or more SNVs expected to satisfy a P value threshold of 5.0 × 10−8 with simulation score of 0.8 or higher (Supplementary Table 6). From every locus, we selected representative SNVs for genotyping in replication sample panels and then performed a meta-analysis with data from the three GWAS. For one particular SNV locus (rs181511609) that satisfied the criteria, a genotyping assay could not be designed due to the complexity of the surrounding sequence. As a result, 12 out of 48 examined loci showed significant associations (Table 1, Supplementary Table 7). These included four previously known susceptibility gene loci such as CASP3, FAM167A-BLK, ITPKC, and CD40, seven on chromosome 6p21 (NC_000006.11: 25.5–32.78 Mb) and one in the immunoglobulin heavy variable gene (IGHV) region on chromosome 14q32.33. The trend of association for rs13330932 on chromosome 16q24.1 was not replicated in the follow-up sample panels from the three populations (Supplementary Table 7).

Table 1.

Loci achieving P values < 5.0 × 10−8 in the meta-analyses of Stage 1 and 2 data

| Association statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Meta-analysisa | |||||||

| dbSNP ID | Chr: locationb Closet genes Position within gene |

Alleles Ref/Alt |

Population | OR | P | OR | P | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| rs2720378 | 4: 185568113 | C/G | Japan | 0.64 | 2.5 × 10−8 | 0.85 | 1.7 × 10−3 | 0.83 (0.78–0.89) | 1.6 × 10−8 |

| CASP3 | Korea | 0.83 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.96 | ||||

| intron | Taiwan | 0.81 | 6.6 × 10−3 | 1.03 | 0.78 | ||||

| rs1873212 | 6: 27869631 | C/T | Japan | 1.35 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 1.20 | 1.8 × 10−3 | 1.27 (1.18–1.36) | 2.0 × 10−10 |

| TRX-CAT1-7 | Korea | 1.43 | 0.017 | 1.34 | 0.013 | ||||

| 3′ flanking | Taiwan | 1.29 | 0.012 | 1.17 | 0.27 | ||||

| rs1778477 | 6: 28248594 | A/T | Japan | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.76 | 7.1 × 10−5 | 0.77 (0.70–0.83) | 7.2 × 10−10 |

| PGBD1 | Korea | 0.66 | 7.2 × 10−3 | 0.83 | 0.094 | ||||

| 5′ flanking | Taiwan | 0.72 | 2.9 × 10−3 | 0.84 | 0.31 | ||||

| rs1264516 | 6: 30411903 | C/A | Japan | 1.31 | 5.2 × 10−4 | 1.21 | 2.8 × 10−4 | 1.24 (1.16–1.32) | 3.9 × 10−11 |

| LOC105375012 | Korea | 1.38 | 8.0 × 10−3 | 1.29 | 3.5 × 10−3 | ||||

| 3′ flanking | Taiwan | 1.20 | 0.27 | 1.11 | 0.35 | ||||

| rs2857602 | 6: 31533378 | G/A | Japan | 0.73 | 8.9 × 10−6 | 0.77 | 2.5 × 10−7 | 0.78 (0.73–0.83) | 2.8 × 10−15 |

| LTA | Korea | 0.67 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 0.81 | 0.027 | ||||

| intron | Taiwan | 0.86 | 0.059 | 0.84 | 0.13 | ||||

| rs3129960 | 6: 32300809 | A/G | Japan | 0.72 | 3.5 × 10−4 | 0.66 | 7.1 × 10−8 | 0.73 (0.67–0.80) | 6.7 × 10−13 |

| C6orf10/ LOC101929163 | Korea | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.83 | 0.22 | ||||

| intron/intron | Taiwan | 0.75 | 1.7 × 10−3 | 0.83 | 0.17 | ||||

| rs7775228 | 6: 32658079 | T/C | Japan | 1.29 | 5.4 × 10−4 | 1.36 | 3.1 × 10−9 | 1.26 (1.19–1.35) | 7.0 × 10−13 |

| HLA-DQB1 | Korea | 1.07 | 0.60 | 1.05 | 0.65 | ||||

| 5′ flanking | Taiwan | 1.35 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 1.08 | 0.54 | ||||

| rs2071473 | 6: 32782605 | C/T | Japan | 1.39 | 8.4 × 10−6 | 1.29 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 1.26 (1.18–1.34) | 6.7 × 10−13 |

| HLA-DOB | Korea | 1.32 | 0.23 | 1.30 | 6.1 × 10−3 | ||||

| intron | Taiwan | 1.09 | 0.26 | 1.15 | 0.22 | ||||

| rs2736340 | 8: 11343973 | C/T | Japan | 1.71 | 1.3 × 10−9 | 1.51 | 6.2 × 10−13 | 1.55 (1.44–1.66) | 6.6 × 10−33 |

| BLK | Korea | 1.48 | 6.1 × 10−3 | 1.48 | 3.8 × 10−4 | ||||

| 5′ flanking | Taiwan | 1.56 | 2.0 × 10−7 | 1.55 | 7.6 × 10−4 | ||||

| rs4774175 | 14: 107152027 | G/A | Japan | 1.22 | 4.9 × 10−3 | 1.22 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 1.20 (1.13–1.28) | 6.0 × 10−9 |

| IGHV1-69 | Korea | 1.40 | 7.6 × 10−3 | 1.20 | 0.059 | ||||

| 3′ flanking | Taiwan | 1.16 | 0.042 | 1.06 | 0.63 | ||||

| rs28493229 | 19: 41224204 | G/C | Japan | 1.50 | 3.4 × 10−6 | 1.38 | 1.3 × 10−6 | 1.41 (1.29–1.53) | 1.1 × 10−14 |

| ITPKC | Korea | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.25 | 0.14 | ||||

| intron | Taiwan | 1.97 | 1.9 × 10−6 | 1.24 | 0.27 | ||||

| rs1883832 | 20: 44746982 | T/C | Japan | 1.34 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 1.18 | 2.1 × 10−3 | 1.28 (1.20–1.36) | 1.5 × 10−13 |

| CD40 | Korea | 1.07 | 0.61 | 1.32 | 5.1 × 10−3 | ||||

| 5′ UTR | Taiwan | 1.41 | 4.9 × 10−6 | 1.42 | 2.3 × 10−3 | ||||

For all single nucleotide variants (SNVs), association in the logistic redression model was evaluated and odds ratios were calculated for the effects of the alternative alleles

Chr chromosomes, Ref reference allele, Alt alternative allele, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, UTR untranslated region

aCombined odds ratios and P values were calculated using fixed-effects meta-analytic model

bLocation of the SNVs are derived from NCBI human genome reference sequence Build 37.3

Association signals that newly achieved genome-wide significance after the meta-analyses of three GWAS and follow-up association studies

A significant association of rs2857151 located near HLA-DOB and HLA-DQB2 genes with KD susceptibility was reported in the earlier Japanese GWAS [9]. However, the present study revealed that the association statistics for rs2857151 were not consistent across the other East Asian populations (Supplementary Table 8). Instead, 7 out of 12 groups of SNVs in the 6p21 region examined in the Stage 2 analyses showed significant association in the meta-analyses of the data sets in the three GWAS as well as in the follow-up studies (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3A). To verify that those seven signals were associated independently from rs2857151, we calculated LD between these SNVs and rs2857151, and we also performed logistic regression analyses conditioning on rs2857151 using the Japanese Stage 2 sample set. Consistent with information from 1000 Genomes, the seven candidates were not in high LD with each other (Supplementary Fig. 3B). The association was most significant for rs2857151, and in the conditioned logistic regression analyses, the P value for rs2071473, which was located just 19 kb distal to and in marginal LD with rs2857151 (D′ = 0.99, r2 = 0.36), became nonsignificant (P > 0.05). After conditioning, P values for the other SNVs including rs2857151 itself increased but were still significant (P ≤ 0.05). (Supplementary Table 9). These included SNVs with previous information on their functional significance or association with diseases such as rs2857602, where the associated allele is linked to the A allele at rs2239704 (r2 = 1.0 in the 1000 Genomes JPT population), which has been associated with reduced expression of lymphotoxin A [19], and rs7775228, which was previously associated with asthma in a Japanese population [20]. Thus, further investigation including that in each ethnic group is needed to unravel the involvement of the variants in this region in KD susceptibility.

In the meta-analysis of the Stage 1 and 2 studies, a significant association was also obtained for an SNV within the chromosome 14q32.33 region represented by rs4774175 (P = 6.0 × 10−9) (Table 1). Five hundred and nineteen SNVs, linked with rs4774175 (r2 > 0.1), and having simulation score of 0.5 or higher were distributed across a 340 kb region (106.88–107.22 Mb) of this locus where many IGHV genes as well as their pseudogenes are clustered in tandem. Similar to the HLA region, most IGHV genes harbor common nonsynonymous SNVs within them contributing to the high level of diversity observed within the immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoire. Therefore, we proceeded to analyze the nonsynonymous SNVs in that locus. Among the 519 SNVs, 18 were nonsynonymous and the others were intergenic, intronic, in the untranslated region, or synonymous SNVs. When the Japanese sample set used in the Stage 2 analysis was genotyped for these 18 nonsynonymous SNVs, rs6423677 in the IGHV3-66 gene showed the most significant association (Table 2). As expected, some other nonsynonymous SNVs also showed a similar trend of association. However, those associations, including that of rs4774175, were considered to be explained by LD with rs6423677 because they were no longer significant after conditioning the logistic regression analyses on rs6423677 (Table 2). In contrast, rs6423677 remained significant (P < 0.05) after adjusting for any of the other SNVs (data not shown). In a Stage 3 analysis, rs4774175 and rs6423677 were further examined in an additional Japanese sample set, and rs6423677 achieved genome-wide significance in a meta-analysis of the Japanese sample panels (Table 3). Meanwhile, the association trend of rs6423677 was weaker in Korean and unreproducible in Taiwanese subjects (Supplementary Table 10).

Table 2.

Association of the 18 nonsynonymous SNVs of IGHV genes as candidates and rs4774175

| Association statistics OR (95% CI) Plogistic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNVs | Position | Alleles Ref/Alta |

Gene | r2 with rs6423677 | Distance from rs6423677 | RAF KDb/Ctrlb | PHWE | Single-SNP | Conditionalc |

| rs61999676 | 106926328 | A/C | V3-43 | 0.15 | 204836 | 0.33/0.32 | 0.60 |

1.07 (0.97–1.20) 0.19 |

0.96 (0.85–1.08) 0.50 |

| rs79008247 | 106926456 | A/C | V3-43 | 0.16 | 204708 | 0.33/0.31 | 0.21 |

1.11 (0.99–1.86) 0.063 |

1.00 (0.88–1.12) 0.95 |

| rs7141669 | 106963101 | C/T | V1-45 | 0.17 | 168063 | 0.34/0.33 | 0.98 |

1.08 (0.97–1.20 0.14) |

0.96 (0.86–1.09) 0.55 |

| rs7148607 | 106993945 | T/C | V3-48 | 0.17 | 137219 | 0.36/0.35 | 0.78 |

1.09 (0.98–1.20) 0.12 |

0.97 (0.86–1.09) 0.60 |

| rs2073674 | 107013129 | A/C | V3-49 | 0.24 | 118035 | 0.41/0.39 | 0.16 |

1.07 (0.97–1.19) 0.17 |

0.93 (0.83–1.05) 0.26 |

| rs2073673 | 107013201 | G/T | V3-49 | 0.23 | 117963 | 0.59/0.58 | 0.18 |

1.03 (0.93–1.14) 0.59 |

0.89 (0.79–1.00) 0.044 |

| rs2516904 | 107078567 | T/C | V1-58 | 0.68 | 52597 | 0.54/0.49 | 0.03 |

1.20 (1.09–1.32) 3.0 × 10−4 |

0.96 (0.80–1.15) 0.65 |

| rs72483334 | 107099262 | T/C | V3-62 | 0.74 | 31902 | 0.54/0.49 | 0.24 |

1.22 (1.10–1.34) 1.1 × 10−4 |

0.97 (0.79–1.00) 0.79 |

| rs113692972 | 107099328 | A/T | V3-62 | 0.74 | 31836 | 0.53/0/49 | 0.21 |

1.20 (1.09–1.32) 3.0 × 10−4 |

0.92 (0.76–1.13) 0.44 |

| rs2072045 | 107113851 | C/T | V3-64 | 0.76 | 17313 | 0.54/0.49 | 0.19 |

1.20 (1.08–1.32) 3.6 × 10−4 |

0.90 (0.73–1.10) 0.30 |

| rs11846079 | 107114009 | T/C | V3-64 | 0.75 | 17155 | 0.54/0.49 | 0.49 |

1.20 (1.08–1.32) 4.3 × 10−4 |

0.89 (0.72–1.10) 0.28 |

| rs2073670 | 107114193 | A/G | V3-64 | 0.76 | 16971 | 0.54/0.49 | 0.31 |

1.20 (1.09–1.32) 3.2 × 10−5 |

0.91 (0.73–1.12) 0.36 |

| rs6423677 | 107131164 | A/C | V3-66 | NA | 0 | 0.49/0.43 | 0.09 |

1.26 (1.14–1.39) 4.5 × 10−6 |

NA |

| rs149638514 | 107131290 | T/C | V3-66 | 0.90 | 126 | 0.50/0.45 | 0.23 |

1.22 (1.10–1.34) 1.0 × 10−4 |

0.74 (0.52–1.04) 0.09 |

| rs4774175 | 107152027 | G/A | Intergene | 0.85 | 20863 | 0.50/0.45 | 0.56 |

1.22 (1.10–1.35) 1.7 × 10−4 |

0.89 (0.68–1.17) 0.40 |

| rs8009570 | 107170055 | G/A | V1-69 | 0.72 | 38891 | 0.54/0.49 | 0.32 |

1.23 (1.11–1.35) 5.7 × 10−5 |

1.01 (0.82–1.23) 0.94 |

| rs55891010 | 107170062 | A/G | V1-69 | 0.67 | 38898 | 0.52/0.47 | 0.11 |

1.24 (1.12–1.37) 4.4 × 10−5 |

1.05 (0.87–1.26) 0.63 |

| rs11845244 | 107170077 | C/T | V1-69 | 0.81 | 38913 | 0.52/0.47 | 0.48 |

1.23 (1.12–1.36) 3.4 × 10−5 |

0.99 (0.77–1.26) 0.91 |

| rs2073669 | 107178965 | A/C | V2-70 | 0.84 | 47801 | 0.51/0.46 | 0.80 |

1.23 (1.11–1.36) 6.1 × 10−5 |

0.91 (0.69–1.20) 0.51 |

SNV single nucleotide variant, Ref reference allele, Alt alternative allele, RAF risk allele frequency, Ctrl control, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, PHWE p value for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the control population

aAlleles associated with KD are underlined

bJapanese KD cases (n = 1418) and controls (n = 1700) prepared as a follow-up sample panel

cConditional logistic regression analyses

Table 3.

Association of rs6423677 and KD in the Japanese case and control panels

| Association statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cohort | Meta-analysis | ||||||

| SNV | Case-control sets | KD/Control | OR (95% CI) | Plogistic | OR (95% CI) | Pmeta | QE P |

| rs4774175 | GWAS | 428/3379 | 1.22 (1.06–1.41) | 4.9 × 10−2 | 1.19 (1.11–1.28) | 3.4 × 10−6 | 0.70 |

| Follow-up panel | 1402/1652 | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | 1.7 × 10−4 | ||||

| Replication panel | 1729/651 | 1.14 (1.00–1.29) | 5.0 × 10−2 | ||||

| rs6423677 | GWAS | 428/3379 | 1.28 (1.09–1.52) | 3.3 × 10−2 | 1.25 (1.16–1.34) | 6.8 × 10−10 | 0.84 |

| Follow-up panel | 1417/1699 | 1.27 (1.15–1.40) | 4.5 × 10−6 | ||||

| Replication panel | 1758/653 | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 4.2 × 10−3 | ||||

KD Kawasaki disease, SNV single nucleotide variant, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, QE P P values for QE statistics in tests for residual heterogeneity

rs6423677 genotypes and IGHV3-66 gene usage in the immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoire

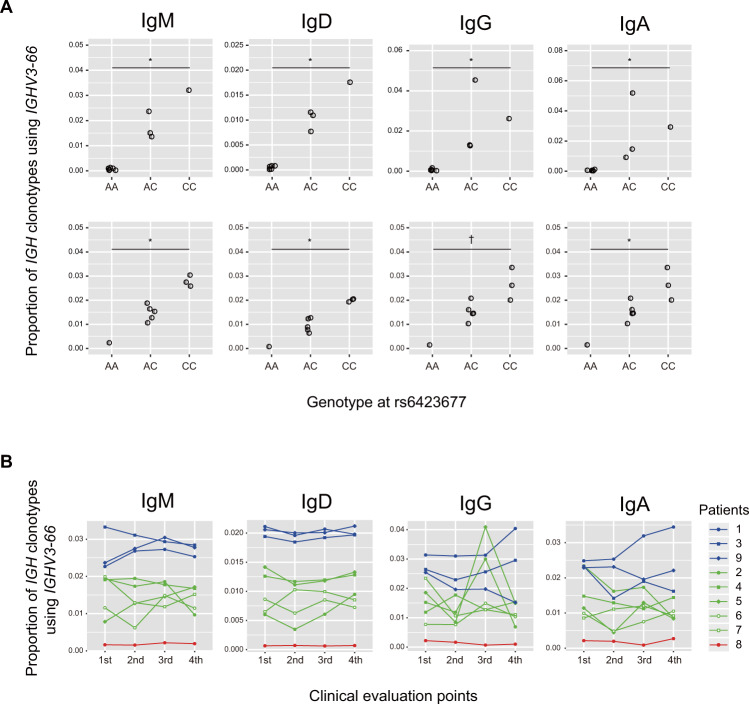

The significant association of an SNV within IGHV3-66 with KD prompted us to investigate the impact of rs6423677 on the function of immunoglobulin molecules or B cell receptors (BCRs) harboring IGHV3-66 in their heavy chain variable regions. Firstly, we examined IGHV usage in different immunoglobulin isotypes (IgM, IgD, IgG, and IgA) by analyzing the immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoire in peripheral B lymphocytes from healthy Japanese individuals (n = 10) and patients with acute KD (n = 9) by NGS. For every Ig isotype, we could identify IGHV3-66 clonotypes in each individual and found that the IGHV3-66 usage tended to be correlated with the number of C alleles each individual had (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 4). Consistent with the correlation trend, we observed significantly skewed usage of the alleles in the analyses of the five patients who were heterozygous for rs6423677, with the protective allele (A) almost completely suppressed in all immunoglobulin classes and time points examined (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similar correlation trend was also observed between rs6423677 genotypes and relative levels of IGH transcript for IGHV3-64, the closest neighboring gene to IGHV3-66. However, the correlations were more modest than that seen for IGHV3-66 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Paralogues or pseudogenes of IGHV3-66 which have the ‘A’ nucleotide at the corresponding position of rs6432677 as well as PCR amplification bias in library preparation caused by additional variants interfering with the primer annealing could lead to such results. However, the distinct separation pattern of the allele discrimination plot in the Invader Assay and the clear electropherogram data in the direct sequencing of PCR-amplified genomic DNA from heterozygous patients does not support that possibility (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, we consider these observations not to be artificial in origin. We also negated the chance of misassignment of IGHV3-66 with the A allele at rs6423677 (IGHV3-66*03) to other alleles (*01, *02, or *04) or paralogues such as IGHV3-53 by confirming that the migmap software could correctly assign an artificially created sequence with the rs6423677 A allele as IGHV3-66*03 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effect of rs6423677 genotypes on the relative expression level of immunoglobulin heavy chain transcripts with IGHV3-66. A The proportion of clonotypes with IGHV3-66 among all IGH transcripts displayed by rs6423677 genotype for each immunoglobulin isotype. Ten healthy adult volunteers (upper) and nine KD patients (lower) were analyzed. For KD patients, mean data of proportions at the four evaluation points were plotted. The increasing trend of the proportions according to the number of the C allele at rs6423677 was statistically evaluated with Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test. *P < 0.005, †P < 0.01. B Time-course change of the sequence reads proportions of immunoglobulin heavy chain transcripts with IGHV3-66 of acute KD patients. Evaluation was done on four time points including (1) acute phase before receiving IVIG (3–8 illness days), (2) 48 h after the patients became afebrile (8–18 illness days), (3) the first follow-up visit to the pediatric clinic after discharge (17–50 days after the disease onset) and (4) the second follow-up visit to the pediatric clinic after discharge (3–4 months after the disease onset).In each panel, symbols and lines of red, green, and blue colors are representing KD patients with genotypes of AA, AC, and CC at rs6423677, respectively. The analyses were carried out for four immunoglobulin classes (IgM, IgD, IgG, and IgA)

A feature of the immunoglobulin repertoire of peripheral B lymphocytes from KD patients

To obtain an insight into the role of immunoglobulins using IGHV3-66 in their heavy chain variable region in the pathogenesis of KD, we investigated how IGHV3-66 usage in the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene repertoire changed over time during the clinical courses of nine KD patients (Supplementary Table 11). Proportions of IGH clones harboring IGHV3-66 in their variable region seemed to be stable or not to have common varying patterns for IgM, IgD, and IgA, while in two patients (patients 2 and 5), transient increases were observed for IgG at the third evaluation point (Fig. 2B). Then, we investigated the increased clonotypes in the IgG heavy chain repertoire more precisely by defining them by the combinations of IGHV, IGHD, and IGHJ genes. We found that both patients 2 and 5 had single clonotypes with IGHV3-66 that increased 1.0% or more as a proportion of the total from the first to the third evaluation points. However, the gene combinations of them were not the same (Table 4), and CDR3 amino acid sequences corresponding to the V-D-J combinations also differed between the patients (data not shown). Five of the remaining seven patients also had one or more IgG heavy chain clonotypes with IGHV3-66 that increased 0.1% or more at the same follow-up time point. However, cooccurring V-D-J combinations in the increased clonotypes were only seen between patients 2 and 6.

Table 4.

IgG heavy chain clonotypes using IGHV3-66 that increased more than 0.1% as a proportion at the third evaluation point

| Clonotypes | Proportion in the repertoire at each clinical evaluation point | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Genotype at rs6423677 | IGHV-gene | IGHD-gene | IGHJ-gene | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | Increase during 1st and 3rd points |

| 1 | CC | 3-66*02 | 5-24*01 | 4*02 | 0.00016 | 0.00026 | 0.0099 | 0.002 | 0.0098 |

| 3-66*02 | 3-16*01 | 2*01 | 4.6 × 10−6 | 4.3 × 10−6 | 0.0041 | 0 | 0.0041 | ||

| 2 | AC | 3-66*01 | 6-19*01 | 4*02 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 0.00045 | 0.011 | 0.00065 | 0.011 |

| 3-66*01 | 2-21*01 | 4*02 | 0.0012 | 0.00032 | 0.0068 | 0.00014 | 0.0056 | ||

| 3-66*01 | 3-10*01 | 4*02 | 0.00097 | 0.00036 | 0.0042 | 8.1 × 10−5 | 0.0032 | ||

| 3 | CC | 3-66*02 | 1-1*01 | 6*02 | 5.1 × 10−6 | 0.00016 | 0.0053 | 0.00015 | 0.0053 |

| 3-66*02 | 3-22*01 | 6*02 | 0.00029 | 0.0012 | 0.0019 | 0.0024 | 0.0016 | ||

| 3-66*02 | 6-19*01 | 2*01 | 0.00012 | 0.00094 | 0.0017 | 0.0009 | 0.0015 | ||

| 3-66*02 | 4-17*01 | 4*02 | 1.8 × 10−5 | 0.00015 | 0.0014 | 2.2 × 10−5 | 0.0014 | ||

| 4 | AC | 3-66*01 | 5-24*01 | 4*02 | 0.00051 | 0.00015 | 0.0017 | 0.0009 | 0.0012 |

| 5 | AC | 3-66*01 | 3-3*01 | 4*02 | 3.3 × 10−5 | 0.0012 | 0.028 | 1.8 × 10−5 | 0.028 |

| 3-66*01 | 3-9*01 | 3*02 | 0 | 6.2 × 10−5 | 0.0018 | 0 | 0.0018 | ||

| 3-66*01 | 4-17*01 | 3*02 | 4.7 × 10−6 | 4.9 × 10−5 | 0.0014 | 0 | 0.0014 | ||

| 6 | AC | 3-66*01 | 3-22*01 | 4*02 | 0.00028 | 0.00073 | 0.0025 | 0.0018 | 0.0022 |

| 3-66*01 | 3-10*01 | 4*02 | 0.0007 | 0.00027 | 0.0018 | 0.00058 | 0.0011 | ||

| 3-66*01 | 6-19*01 | 4*02 | 8.6 × 10−5 | 0.00036 | 0.0012 | 5.2 × 10−5 | 0.0011 | ||

| 7 | AC | 3-66*01 | 1-1*01 | 6*02 | 0.00013 | 0.00034 | 0.0014 | 3.4 × 10−5 | 0.0012 |

| 8 | AA | none | |||||||

| 9 | CC | none | |||||||

Clonotypes increased more than 1% during 1st and 3rd evaluation points are bold faced

On the other hand, some of the CDR3 clonotypes which have recently been reported to dominate in the IgM heavy chain repertoire (>0.001%) in the acute pretreatment phase of Taiwanese KD patients [21] were also prevalent at a similar time point in the Japanese KD patients in this study (Supplementary Table 12). A distinct increase in diversity of the CDR3 clonotypes of IgM heavy chain during the convalescent phase of KD, which has also been reported in previous research of Taiwanese KD patients [21], was observed for four of the nine KD patients (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Discussion

It has generally been considered that the immune-mediated vasculitis of KD is triggered in response to infection with some type of microorganism. This assumption was made based on factors indicative of a primary infection, such as its clinical symptoms, which included fever and skin rash, epidemiologic findings such as its peak age of onset (6 months to 1 year), along with the seasonality of the occurrence of regional outbreaks and nation-wide epidemics [2, 11]. Despite tremendous efforts, no single microorganism has been conclusively proven as the pathogen of KD and lack of information about the pathogen has been a significant obstacle to causal treatment and disease prevention.

Histopathological and immunological studies have revealed activation of neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes in the acute phase of KD [22, 23], and now the leading hypothesis for the pathophysiology of KD inflammation is an attack of the dysregulated or hyperactive innate immune system against vascular walls [24]. In addition, genetic studies using a genome-wide approach have identified several robust susceptibility loci/genes for KD [8–10, 12, 25–32], and an in silico prediction of responsible variants and the types of cells where they have biological significance has highlighted the importance of B cells in the pathogenesis of KD [33]. In previous literature, polyclonal activation and increase of B cells [34, 35] and detection of auto-antibodies against components of vascular endothelial cells or neutrophils in peripheral blood of acute KD patients have been documented [36, 37]. Infiltration of oligoclonal plasma cells producing IgA into the vascular wall of KD patients was also reported [38]. These previous findings have suggested the involvement of B cells in KD inflammation. However, a recent transcriptomic study revealed downregulation of genes related to BCR signaling in acute KD patients [39]. Thus, there have been both supportive and unsupportive pieces of evidence, and there is no consensus view on the role of B cells, as well as of the adaptive immune system in KD pathogenesis. In this study, we identified genetic variants within the IGHV region significantly associated with KD in the Japanese population. The immunoglobulin heavy (IGH) locus spans 1.3 Mb (from 106.0 to 107.3 Mb on NC_000014.8) of the chromosome 14q32.33 region and encompasses serially arranged IGH constant (IGHC), IGHJ, IGHD, and IGHV clusters. Because of high sequence redundancy which obstructs designing of specific genotyping assays, there is a large blank area (~0.8 Mb) which was not covered by the SNP arrays and therefore we lack association information about the SNVs in the area (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, because SNVs within the gap are not in high LD (r2 < 0.3) with rs6423677 or rs4774175 in the 1000 genomes JPT population (Supplementary Fig. 8) and we did not observe association signals in the chromosomal region on the opposite side of the blank area, the association signals represented by rs6423677 or rs4774175 might be localized within the region where we could investigate in this study.

In contrast to the robust association of rs6423677 in the Japanese subjects, it was not consistent in the Korean and Taiwanese subjects. Although neither significant nor consistent with the results in the current study, a marginal trend of association between SNVs within the IGHV region and linked to rs4774175 (r2 = 0.45–0.66 in the 1000genomes CHB population) and KD in the Taiwanese population had already been reported [28]. Findings in the previous and the current studies are strongly indicating that variants in the IGHV region are commonly involved in KD pathogenesis at least in the Japanese and Taiwanese populations. However, the robustness of association might not be uniform among the populations. Given that multiple pathogens with regionally or seasonally differing epidemic patterns could be triggering KD, it might be possible that various susceptibility genes or alleles corresponding to different antigenicity for the pathogens exist in this locus and are related to the mixed robustness of the association.

Highly skewed expression of IGH transcripts with the risk-associated allele adds support to consider that IGHV3-66 is the functional target of the associated variants. The A to C nucleotide change at rs6423677 results in an amino acid alteration from cysteine to glycine within the CDR2 region of IGHV3-66. Thus, the modification might affect the affinity to some antigens of immunoglobulins carrying IGHV3-66. However, we consider that the mechanism of increased susceptibility to KD associated with the C allele might not be due to reduced host defense to particular agents because it is inconsistent with the observation that the A allele, which is protective against KD and expected to have a higher neutralizing ability in this scenario, seemed to be nearly silenced. IGHV3-66 has been recognized as one of the functional IGHV genes and purported to be utilized at frequencies of around 1% [40]. The average proportions of IGHV3-66 clonotypes in the 10 healthy adults in our study (0.88% for IgM, 0.50% for IgD, 1.0% for IgG, and 1.1% for IgA), were consistent with that previous information. It is currently unknown in what stage, i.e., somatic recombination, RNA transcription, and processing of the pre-mRNA, the A allele was excluded and resulted in the significantly skewed allelic usage to the C allele of rs6423677. It is suggestive that usage of IGHV3-64, the nearest functional gene to IGHV3-66, showed difference among genotypes at rs6423677 which was similar to that of IGHV3-66 (Supplementary Fig. 6). One potential reason is suggested by the predicted binding of CTCF transcription repressor in the 0.4 kb region encompassing rs6423677 (Supplementary Fig. 9). CTCF has been reported to interact with multiple sites in the IGH region and plays essential roles in somatic recombination [41] of the distal area of the IGHV gene region. The association data of rs6423677 and the increased usage of IGH transcripts with the risk-associated allele are indicative of some active role of the immunoglobulin molecules as antibodies or as components of BCRs in the development of KD. One possible role of such immunoglobulins might be activation of B cells. Established KD susceptibility gene products such as B lymphoid tyrosine kinase (BLK) [8–10] and Inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate 3-kinase C (ITPKC) [8, 9] are involved in BCR signaling. If IVIG acts through competing with such immunoglobulins for agents or antigens relevant to KD pathogenesis, the requirement of a high dose administration (1–2 g/kg) of IVIG to treat KD might be reasonable because only a fraction of the IgG would contribute to the therapeutic effect, with IGHV3-66 expected to only account for up to several percent of the IVIG preparations. B cells can be activated by nonspecific binding of microbial products such as superantigens (SAgs) to BCRs. Intriguingly, B cell SAgs restricted to IGHV3 segment of immunoglobulins have been known [42]. However, considering that the innate immune system has been thought to play a central role in the KD vasculitis and that KD can develop in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia, who lack or have small numbers of B cells [43], the activity of B cells or immunoglobulins in KD might be relevant to initiation or enhancement of the innate immune activation but may be substitutable.

Recently, a significant association of an allele of the IGHV4-61 gene (IGHV4-61*02) with susceptibility to rheumatic heart disease (RHD), which is a long-term complication of ARF, was reported [44]. IGHV4-61 is located only 36 kb downstream of IGHV3-66 (Supplementary Fig. 6). ARF develops as a sequela of Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) infection and, similar to KD, has been recognized to affect genetically susceptible individuals [45]. Among reports of GWAS for human diseases, a genome-wide significant association of variants in the IGHV gene region has been identified only for RHD. Although S. pyogenes is not recognized as the cause of KD, considering that KD shares some characteristic symptoms such as skin rash and strawberry tongue with S. pyogenes infection, it is suggestive that the previously discussed role of B cells might be related to some underlying mechanisms of the common symptoms.

In 2020, multiple series of patients with Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally Associated with SARS-CoV2 infection (PIMS-TS) or (MIS-C) having KD-like symptoms or increase of severe KD patients after the SARS-CoV2 epidemic were reported from the US and European countries [46, 47]. In the latest studies, overrepresentation of IGHV3-53 and IGHV3-66 in neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV2 spike were also reported [48, 49]. Given immunoglobulin with IGHV3-66 play a role in KD, it might be possible that KD-like symptoms seen in such patients are mediated by interaction between SARS-CoV2 and B cells expressing IGHV3-66.

We also found some commonality between the CDR3 clonotypes that were increased in the IgM heavy chains of the Taiwanese and the Japanese KD patients (Supplementary Table 12). IGHV3-66 was used only in one commonly increased CDR3 clonotype (Supplementary Table 13). However, as far as can be understood from the limited number of observations, IGHV3-66 seemed not to be important in the IgM response in the acute pretreatment phase.

Future characterization of the endogenous immunoglobulin molecules that are increased in KD patients utilizing information of the light chains that can be obtained simultaneously in single-cell analyses [50] will facilitate identification of the agent triggering KD as well as understanding the mechanism of action of IVIG treatment.

There are limitations in this study. First, in addition to the gap above where we could not examine the association of the variants, our strategy to focus only on nonsynonymous SNVs on IGHV genes left the possibility that rs6423677 is just a proxy of the genuinely responsible variant located outside IGHV3-66. Second, we did not analyze the time-course change of the immunoglobulin heavy chain repertoire in other infectious diseases. So it is uncertain whether the upregulation of IgG heavy chain transcripts with IGHV3-66 is a specific observation for KD or not. Third, our results might not directly reflect changes of the immunoglobulins at the protein level because we lack information about the correlation between the proportions of particular IGH clones in the transcripts from B cells and in the proteins expressed on the cell surface or circulating in the serum.

In conclusion, a significant association of a nonsynonymous SNV in the IGHV3-66 gene with KD was observed. Further intensified study of the association in this region and repertoire analyses of immunoglobulins in different ethnicities and subpopulations of the patients with different demographic features would give insights into both the role of B cells in the KD pathogenesis and the causal agent of the disease.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Millennium Project, from the Japan Kawasaki Disease Research Center (2015 to YM, and 2018 and 2019 to YO), and from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP18ek0410039 to TH). This study was also supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health & Welfare of the Republic of Korea (HI15C1575 to JKL). We are grateful to the KD patients and their family members as well as the medical staff taking care of the patients. We also thank Ms. Yoshie Kikuchi for her technical assistance.

Author contributions

JKL, JYW, YTC, and YO supervised the study. JKL, JYW, and YO conceived the study. JYW, TAJ, TT, JKL, and YO designed the study. TAJ, YM, JKL, JYW, and YO wrote the manuscript. AH, HS, HH, TH, and Japan Kawasaki Disease Genome Consortium collected Japanese samples. YMH, GYJ, SWY, JJY, KYL, and Korean Kawasaki Disease Genetics Consortium collected Korean samples. Taiwan Kawasaki Disease Genetics Consortium and Taiwan Pediatric ID Alliance collected Taiwanese samples. YML coordinated the multi-center collaboration in Taiwan as the project manager and collected samples and clinical information. MK performed GWAS assays for the Japanese samples. AT performed statistical analyses for the Japanese GWAS data. DY and TP performed statistical analyses for the Korean GWAS data. JJK conducted a follow-up study (Stage 2) for the Korean samples. CHC performed statistical analyses for the Taiwanese GWAS data and followed-up meta-analyses for the Taiwanese data. YCL supervised the GWAS and replication genotyping pipeline, performed the data analyses. LCC performed statistical analyses for the Taiwanese GWAS data and followed-up meta-analyses for the Taiwanese data. CPC performed genotyping and direct sequencing of Taiwanese samples. TAJ, DY, and CHC conducted the whole-genome imputation. TAJ performed P value simulation and meta-analyses. KO, TT, and KI performed genotyping and direct sequencing of the Japanese samples. YM and YO performed the NGS data analyses for the IGH repertoires.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at all involved institutes.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Footnotes

Members of the Korean Kawasaki Disease Genetics Consortium, Taiwan Kawasaki Disease Genetics Consortium, Taiwan Pediatric ID Alliance, Japan Kawasaki Disease Genome Consortium are listed in the Supplementary information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Todd A. Johnson, Yoichi Mashimo, Jer-Yuarn Wu, Dankyu Yoon

Contributor Information

Jer-Yuarn Wu, Email: jywu@ibms.sinica.edu.tw.

Jong-Keuk Lee, Email: cookie_jklee@hotmail.com.

Yuan-Tsong Chen, Email: chen0010@ibms.sinica.edu.tw.

Yoshihiro Onouchi, Email: onouchy@chiba-u.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s10038-020-00864-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children. (Japanese) Arerugi 1967; 16: 178–222. English translation by Shike H, Burns JC, Shimizu C. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;21:993–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makino N, Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Sano T, Ae R, Kosami K, et al. Epidemiological observations of Kawasaki disease in Japan, 2013-2014. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:581–7. doi: 10.1111/ped.13544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato H, Koike S, Yamamoto M, Ito Y, Yano E. Coronary aneurysms in infants and young children with acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. J Pediatr. 1975;86:892–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taubert KA, Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Nationwide survey of Kawasaki disease and acute rheumatic fever. J Pediatr. 1991;119:279–82. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furusho K, Sato K, Soeda T, Matsumoto H, Okabe T, Hirota T, et al. High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1984;2:1055–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Burns JC, Beiser AS, Chung KJ, Duffy CE, et al. The treatment of Kawasaki syndrome with intravenous gamma globulin. N. Engl J Med. 1986;315:341–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608073150601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Beiser AS, Burns JC, Bastian J, Chung KJ, et al. A single intravenous infusion of gamma globulin as compared with four infusions in the treatment of acute Kawasaki syndrome. N. Engl J Med. 1991;324:1633–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khor CC, Davila S, Breunis WB, Lee YC, Shimizu C, Wright VJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies FCGR2A as a susceptibility locus for Kawasaki disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1241–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onouchi Y, Ozaki K, Burns JC, Shimizu C, Terai M, Hamada H, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three new risk loci for Kawasaki disease. Nat Genet. 2012;44:517–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YC, Kuo HC, Chang JS, Chang LY, Huang LM, Chen MR, et al. Two new susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease identified through genome-wide association analysis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:522–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns JC, Kushner HI, Bastian JF, Shike H, Shimizu C, Matsubara T, et al. Kawasaki disease: a brief history. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E27. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JJ, Hong YM, Sohn S, Jang GY, Ha KS, Yun SW, et al. A genome-wide association analysis reveals 1p31 and 2p13.3 as susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease. Hum Genet. 2011;129:487–95.. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2012;9:179–81. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howie B, Marchini J, Stephens M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3. 2011;1:457–70. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao F, Lin E, Feng Y, Mack WJ, Shen Y, Wang K. Characterizing immunoglobulin repertoire from whole blood by a personal genome sequencer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–63. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight JC, Keating BJ, Kwiatkowski DP. Allele-specific repression of lymphotoxin-alpha by activated B cell factor-1. Nat Genet. 2004;36:394–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirota T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Tsunoda T, Tomita K, Doi S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for adult asthma in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:893–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko TM, Kiyotani K, Chang JS, Park JH, Yin YP, Chen YT, et al. Immunoglobulin profiling identifies unique signatures in patients with Kawasaki disease during intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:2671–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Oharaseki T, Naoe S, Wakayama M, Yokouchi Y. Neutrophilic involvement in the damage to coronary arteries in acute stage of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koga M, Ishihara T, Takahashi M, Umezawa Y, Furukawa S. Activation of peripheral blood monocytes and macrophages in Kawasaki disease: ultrastructural and immunocytochemical investigation. Pathol Int. 1998;48:512–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara T, Nakashima Y, Sakai Y, Nishio H, Motomura Y, Yamasaki S. Kawasaki disease: a matter of innate immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;186:134–43. doi: 10.1111/cei.12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onouchi Y, Gunji T, Burns JC, Shimizu C, Newburger JW, Yashiro M, et al. ITPKC functional polymorphism associated with Kawasaki disease susceptibility and formation of coronary artery aneurysms. Nat Genet. 2008;40:35–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onouchi Y, Ozaki K, Burns JC, Shimizu C, Hamada H, Honda T, et al. Common variants in CASP3 confer susceptibility to Kawasaki disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2898–906. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgner D, Davila S, Breunis WB, Ng SB, Li Y, Bonnard C, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel and functionally related susceptibility Loci for Kawasaki disease. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai FJ, Lee YC, Chang JS, Huang LM, Huang FY, Chiu NC, et al. Identification of novel susceptibility Loci for Kawasaki disease in a Han chinese population by a genome-wide association study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khor CC, Davila S, Shimizu C, Sheng S, Matsubara T, Suzuki Y, et al. Genome-wide linkage and association mapping identify susceptibility alleles in ABCC4 for Kawasaki disease. J Med Genet. 2011;48:467–72. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.086611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu C, Eleftherohorinou H, Wright VJ, Kim J, Alphonse MP, Perry JC, et al. Genetic variation in the SLC8A1 calcium signaling pathway is associated with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease and coronary artery abnormalities. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9:559–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J, Shimizu C, Kingsmore SF, Veeraraghavan N, Levy E, Dos Santos AMR, et al. Whole genome sequencing of an African American family highlights toll like receptor 6 variants in Kawasaki disease susceptibility. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JJ, Yun SW, Yu JJ, Yoon KL, Lee KY, Kil HR, et al. A genome-wide association analysis identifies NMNAT2 and HCP5 as susceptibility loci for Kawasaki disease. J Hum Genet. 2017;62:1023–9. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2017.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farh KK, Marson A, Zhu J, Kleinewietfeld M, Housley WJ, Beik S, et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature. 2015;518:337–43. doi: 10.1038/nature13835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leung DY, Siegel RL, Grady S, Krensky A, Meade R, Reinherz EL, et al. Immunoregulatory abnormalities in mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982;23:100–12. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(82)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furukawa S, Matsubara T, Yabuta K. Mononuclear cell subsets and coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 1982;67:706–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.6.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leung DY, Collins T, Lapierre LA, Geha RS, Pober JS. Immunoglobulin M antibodies present in the acute phase of Kawasaki syndrome lyse cultured vascular endothelial cells stimulated by gamma interferon. J Clin Investig. 1986;77:1428–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI112454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savage CO, Tizard J, Jayne D, Lockwood CM, Dillon MJ. Antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies in Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:360–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowley AH, Shulman ST, Spike BT, Mask CA, Baker SC. Oligoclonal IgA response in the vascular wall in acute Kawasaki disease. J Immunol. 2001;166:1334–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikeda K, Yamaguchi K, Tanaka T, Mizuno Y, Hijikata A, Ohara O, et al. Unique activation status of peripheral blood mononuclear cells at acute phase of Kawasaki disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:246–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lange MD, Huang L, Yu Y, Li S, Liao H, Zemlin M, et al. Accumulation of VH replacement products in IgH genes derived from autoimmune diseases and anti-viral responses in human. Front Immunol. 2014;5:345. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo C, Yoon HS, Franklin A, Jain S, Ebert A, Cheng HL, et al. CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2011;477:424–30. doi: 10.1038/nature10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silverman GJ, Sasano M, Wormsley SB. Age-associated changes in binding of human B lymphocytes to a VH3-restricted unconventional bacterial antigen. J Immunol. 1993;151:5840–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behniafard N, Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Pourjabbar S, Sabouni F, Rezaei N. Autoimmunity in X-linked agammaglobulinemia: Kawasaki disease and review in the literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:155–9. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parks T, Mirabel MM, Kado J, Auckland K, Nowak J, Rautanen A, et al. Pacific Islands rheumatic heart disease genetics network. Association between a common immunoglobulin heavy chain allele and rheumatic heart disease risk in Oceania. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14946. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carapetis JR, Currie BJ, Mathews JD. Cumulative incidence of rheumatic fever in an endemic region: a guide to the susceptibility of the population? Epidemiol Infect. 2000;124:239–44. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated With SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324:259–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao Y, Su B, Guo X, Sun W, Deng Y, Bao L, et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients’ B cells. Cell. 2020;182:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnes CO, West AP, Jr, Huey-Tubman KE, Hoffmann MAG, Sharaf NG, Hoffman PR, et al. Structures of human antibodies bound to SARS-CoV-2 spike reveal common epitopes and recurrent features of antibodies. Cell. 2020;182:828–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeKosky BJ, Ippolito GC, Deschner RP, Lavinder JJ, Wine Y, Rawlings BM, et al. High-throughput sequencing of the paired human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain repertoire. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:166–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.