Abstract

Conventional agricultural practices demand application of pesticides for better yield, yet their uncontrolled use for longer duration exhibit deleterious effects on the soil health and subsequent plant productivity. These circumstances have displayed alarming effects on food security in the modern world. Therefore, biological solutions to the crisis can be practiced in consideration to their environmental benefits. Bacterial endophytes are ubiquitous in the phytosystem and beneficial for the plant growth and productivity. The present study aimed to obtain endophytic bacterial strains that can be developed as effective plant growth promoters. For this purpose twelve strains of bacterial endophytes were isolated from different plant sources and their putative plant growth promoting attributes were analyzed by morphological and biochemical studies. Subsequently these isolates were inoculated in the Solanum lycopersicum (Tomato) and the factors like germination percentage, seedling length, biomass production, and leaf variables were analyzed. However, the vigour index was considered as the prime parameter for determining plant growth. In essence, RR2 and RR4 strains were observed as effective growth promoter, hence in future they can be utilized as effective biofertilizers.

Keywords: Endophytic bacteria, Solanum lycopersicum, Biofertilizers, PGPR traits, Vigour index, Food science, Agricultural science, Environmental science, Biological sciences, Health sciences

Endophytic bacteria; Solanum lycopersicum; Biofertilizers; PGPR traits; Vigour index; Food science; Agricultural science; Environmental science; Biological sciences; Health sciences

1. Introduction

The rise in global population has increased constrains on the food reserves to a large extent. The demand for quality food and its requisite supply has turned out to be the biggest challenge in the last few decades. The gradual reduction of potential crop lands and yield loss due to plant diseases has also added significantly to the problem. An ideal method to implement the ideas of higher yield per unit area by introducing genetically engineered crops or pathogen resistant plant varieties is still debatable. Initially the utilization of chemical fertilizers and pesticides had shown some positive results but with the turn of decades, the side effects like poor soil quality, high irrigation requirements, reinfection of plants by resistant pathogens became evident (Bhattacharjee et al., 2008). Considering this, an array of sustainable agricultural practices involving soil microbiota and endophytes are being suggested for a stable enhancement in plant health and productivity (Lucy et al., 2004; Arcand and Schneider, 2006).

Among all the classes of microbes which have beneficial interactions with plant, the endophytes have gained special interest (Kobayashi and Palumbo, 2000; Dudeja et al., 2012; Panigrahi et al., 2018) as these microorganisms are not only critical for promoting plant growth and productivity (Kloepper and Schroth, 1981), but having a specialized niche within the plant tissues, they act as biocontrol agents (Mercado-Blanco and Bakker, 2007; Ryan et al., 2008). The colonizing capabilities and persistency of these microbes determines their resilience and diversity within the plant and in nature respectively (Rosenblueth and Martínez-Romero, 2006).

Despite occupying different functional niches, the rhizobacteria and endophytes utilize identical mechanism in enhancing plant productivity (Compant et al., 2005). Some of the common pathways displayed by these microbial communities are production of phyto-hormones like indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and cytokinins, synthesis of ACC deaminase (Long et al., 2008; Ryan et al., 2008), nitrogen fixation (Baldani et al., 1998), antibiotic production (Bangera and Thomashow, 1996) and so on. The endophytic community has been proved highly beneficial to the host plants, but the degree of advantages conferred to the host is a function of specific potential strains residing within the particular host. Hence, a strategy to infect crop plants with potential endophytes isolated from different hosts to obtain requisite crop yield has gained significant attentions.

The bacterial endophytes are widely reported to enhance the growth of plants significantly under normal as well as stressed conditions including heavy metal exposure, salinity and drought (Gagne-Bourque et al., 2015; Yaish et al., 2015; Choudhary et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2016). Besides, it also raises the host plant's ability of nutrient uptake by producing extracellular enzymes (Latif Khan et al., 2016), solubilizing minerals (Kang et al., 2009) and nitrogen fixation (Gothwal et al., 2008). On the other hand, the host plant produces growth regulators and secondary metabolites which in turn benefits the endophytes (Schulz and Boyle, 2006). Akhtar et al. (2015) studied the interactive effect of biochar and consortia of Burkholderia phytofirmans (PsJN) and Enterobacter sp. (FD17) containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase and exopolysaccharide activity to mitigate salt stress by reducing the sodium content in xylem and maintaining nutrient balance. It was also reported that under salinity stress Bacillus subtilis enhance the production of IAA and GA but reduce ABA synthesis in Raphanus sativus (Mohamed and Gomaa, 2012). Recently a study reported that the inoculation of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Klebsiella oxytoca into Dendrobium nobile Lindl. raised the germination percentage, adaptive and growth capacity of the orchid (Pavlova et al., 2017). Additionally inoculation of both Pseudomonas stutzeri E25 and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia CR71 into the rhizosphere of tomato seedlings (Lycopersicon esculentum cv Saladette), showed a better plant growth-promoting effect, suggesting that two endophytic strains showed additive effect on the growth of the plant compared to single inoculation (Rojas-Solís et al., 2018). The endophyte, Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN colonizing the rhizosphere is reported to induce biotic stress resistance (Su et al., 2017) and improve the physiological and biochemical functioning of plants by altering the agronomic parameters like chlorophyll content, shoot and root biomass, photochemical efficiency and gas exchange under abiotic stress (Naveed et al., 2014a,b). Shi et al. (2010) reported that Bacillus pumilus significantly increased the carbohydrate synthesis in sugar beet by enhancing the photosynthetic capacity and total chlorophyll content.

Solanum lycopersicum (Tomato) has been used as a model plant in this study. According to FAO 2017, the worldwide production of tomato is around 177 million tonnes per year that is about three times more than potato and six times more than paddy production around the world. Every year about 40 million tonnes of tomatoes are utilized in the processing industry that belongs to the global food industry (Tomato news, 2017). Approximately 7.3 million tonnes of tomatoes undergoes global export. Tomato, being one of the most consumable crops worldwide has always been a priority for agricultural scientists (Villareal, 2019).

In the present study a cumulative comparison has been compassed to recognize the most potential endophyte for tomato cultivation. The objective was to identify growth promoting activity of the endophytes isolated from various terrestrial plants growing in similar conditions and evaluating their growth promoting attributes like phosphate solubilization and production of IAA, ammonia, HCN, and catalase in-vitro. Further, these bacterial endophytes were inoculated in Solanum lycopersicum in a nursery experiment. The increasing growth of tomato assisted by the bacterial isolates was evaluated in terms of vegetative parameters such as root length, shoot length, biomass production and leaf variables. This study signifies the beneficial characteristics of the bacterial endophytes towards the host plant. In future the selected strains may be utilized to improve the growth and productivity of tomato for a greater yield.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Location of study

Samples were collected from various places of Chunar (25.1037° N, 82.8721° E) and Varanasi (25.3176° N, 82.9739° E) district due to considerable diversity of plant varieties observed in these areas and further lab studies were performed in the campus of Banaras Hindu University (25.2677° N, 82.9913° E), Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India. The climate is generally mild, warm and temperate. The average annual temperature is 26.1 °C (summer maximum is 46 °C and winter minimum is 5 °C) and the average rainfall is 1110 mm.

2.2. Sample collection

Healthy parts, which included twigs, leaves and roots from various terrestrial plants (listed in Table 1), were collected from locations that are mentioned above. The samples were collected in a sterile zipped polythene bag, labeled and stored in a cooling box at 4 °C during transit and further processing was done within 24 h of collection to ensure minimum chance of contamination.

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of bacterial isolates and its source.

| Bacterial isolates | Source Plants | Colony Morphology |

Gram Staining | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony shape | Colony Edge | Colony elevation | Pigmentation | |||

| RR1 | Helianthus annuus | Irregular | Undulate | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR2 | Ficus benghalensis | Irregular | Undulate | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR3 | Ficus racemosa | Round | Entire | Raised | Creamy white | -ve |

| RR4 | Mangifera indica | Round | Undulate | Raised | Creamy white | -ve |

| RR5 | Acacia auriculiformis | Round | Entire | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR6 | Solanum tuberosum | Round | Entire | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR7 | Nerium oleander | Irregular | Undulate | Flat | Creamy white | -ve |

| RR8 | Abelmoschus esculentus | Round | Undulate | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR9 | Anacyclus pyrethrum | Irregular | Entire | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR10 | Mimosa pudica | Irregular | Undulate | Flat | White | -ve |

| RR11 | Epipremnum aureum | Round | Entire | Raised | Creamy white | -ve |

| RR12 | Rosa indica | Irregular | Undulate | Raised | Yellowish white | -ve |

2.3. Sample pretreatment

Collected plant parts like stem, leaves and roots were thoroughly washed under running tap water repeatedly to remove the external soil particles, the epiphytic microorganisms and other adherents from the surface. The plant parts excision and surface sterilization were done as described by Arunachalam and Gayathri (2010).

2.4. Isolation of endophytic bacteria

The plant tissues were cut into transverse and longitudinal sections (5 × 5 mm) and placed on solid nutrient agar (peptone 5gL-1, sodium chloride 5 gL-1, beef extract 1.5 gL-1, yeast extract 1.5 gL-1) supplemented with 30 μg/ml bavistin to avoid fungal contaminations. These plates were incubated for 2–4 days at 30 °C. The bacterial colonies appeared adjacent to the plant parts. The morphologically distinguished bacterial colonies were picked and streaked on new nutrient agar plates and incubated at 30 °C. Bacterial colonies were re-streaked in series order to get pure colonies of the isolates. The pure isolates were maintained at 4 °C on nutrient agar slants and also preserved in 20% glycerol stock at -20 °C for future studies.

2.5. Morphological and biochemical characterization of bacterial isolates

The bacterial strain was characterized phenotypically on nutrient agar media plates. The colony characteristics like colony shape, colony edge, colony elevation, pigmentation and Gram nature of the isolates were also analyzed. The biochemical characterizations are described in the following sections.

2.5.1. Phosphate solubilization assay

Bacterial isolates were spot inoculated on Pikovaskaya's phosphate solubilizing agar (Nautiyal, 1999) and incubated for three days at 28 ± 2 °C. Positive colonies showed halo zone of tricalcium phosphate solubilization and solubilization index (SI) was calculated as per Edi-Premono et al. (1996).

2.5.2. Production of indole acetic acid (IAA)

Determination of IAA production was done as described by (Bric et al., 1991) with minor modifications. Culture growth conditions: The 24 h old bacterial cultures were grown in the media containing peptone (10gL-1), sodium chloride (5gL-1), yeast extract (6gL-1), modified with L-tryptophan (1 gL-1) and pH adjusted to 7.6 and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h in an orbital shaker. 1mL of visually opaque cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to separate the bacterial cells from culture medium. Colorimetric estimation: For estimation of IAA in the supernatant salkowski reagent (50ml of 35% perchloric acid and 1ml of 0.5 N FeCl3 solution) was added to the supernatant in 2:1 ratio followed by the addition of two drops of orthophosphoric acid and was incubated in dark condition at room temperature for 30 min. Development of pink or red color indicated IAA production. Optical density of the pink coloured solution was measured at 540 nm using UV-vis spectrophotometer. Standard curve of IAA obtained in μg ml−1 was used to measure the concentration of IAA produced by the bacterial isolates (Glickmann and Dessaux, 1995).

2.5.3. Ammonia production

For testing ammonia production freshly grown cultures were inoculated in peptone broth and incubated at 30 ± 2 °C for 48–72 h. 0.5ml of nessler's reagent was added to each culture tube. Development of yellow to dark brown colour indicated positive test for ammonia production (Cappuccino and Sherman, 1992).

2.5.4. HCN production

The screening of the isolates for the production of hydrogen cyanide was done using the protocol of Lock (1948) with minor modification. The isolates were spot inoculated on nutrient agar media amended with glycine (4.4 g/L). A whatmann filter paper no. 1 soaked in 2% Na2CO3 and 0.5% picric acid was placed on the top of the culture plate. The petriplates were sealed with paraffin and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 4 days. Qualitative analysis of HCN production was observed with the development of orange to red colour for each isolate.

2.5.5. Catalase enzymatic assay

The 24 h old bacterial colony was mixed with a drop of 3% hydrogen peroxide on a glass slide. The formation of oxygen bubbles was considered as positive for catalase activity (Cappuccino and Sherman, 1992).

2.6. Inoculation of bacterial endophytes

Each of the twelve endophytic bacterial isolates with promising plant growth promoting traits were inoculated on tomato seeds separately by biopriming technique. Seeds of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) were surface sterilized with 0.2% HgCl2 for 2 min followed by rinsing in sterile distilled water for 10 min. Seeds were soaked in 25 ml of Nutrient Agar having prescreened bacterial suspension in their log phase containing 109 CFU ml−1 and kept at 30 °C in rotator shaker (90 rpm) for 7–8 h. Control seeds were soaked in sterile medium. The seeds were then dried overnight aseptically and subsequently used for green house experiments. They were then sown in pots containing sterile soil and further soil drench inoculation method was performed. Subsequently these pots were placed in a temperature-controlled plant growth chamber set to 16h light/8h dark and at constant temperature of 25 °C with relative humidity of the air around 60%. Three plants per pot were maintained at 60% water holding capacity.

2.7. Plant growth parameter analysis

The treatments were arranged in a completely randomized design with three replications. During the experimental period (15 days) parameters like seed germination percentage, shoot and root length, root and shoot weight, leaf number, leaf area, relative water content were measured. For measuring the plant growth parameters nine plants were randomly uprooted from each treatment. The effect of endophytic bacterial treatment on seed germination and vigour analysis were carried out by paper towel method (Govender et al., 2008). After 7 days of sowing, the percent germination was calculated.

To assess plant vigour index (VI), root and shoot length of each individual seedling was measured after 15 days. The vigour index was calculated using the formula of Abdul-Baki and Anderson (1973) as shown in Eq. (1):

| (1) |

Biomass was dried to constant weight in oven at 80 °C for recording the dry weight. Moreover, the moisture content of foliage and twigs, also called live fine fuel moisture (LFFM) of shoots of 6mm diameter was also calculated using Eq. (2). Leaf variables including leaf relative water content (RWC), leaf dry matter content (LDMC) and leaf moisture (LM) were also analyzed using the Eqs. (3), (4), and (5) respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

2.8. Statistical analysis

The experiment was performed in completely randomized design. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done using the triplicate value. Statistical significance between the treatments was compared by least significant difference (LSD) test at P < 0.05 probability level on different plant growth promoting parameters using SAS university edition.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological characteristics of bacterial isolates

Characterizations of bacterial isolates on the basis of colony morphology depicted variabilities among different colony attributes. However, some of the isolates displayed identical properties like RR1, RR2 and RR10 had irregular shaped with undulated edged whitish flat colonies, and RR5 and RR6 were whitish flat colonies having round shaped with entire edge. The alterations in the colony properties were evident and comparable yet no characteristic identification marking any special trait were visible, except the yellowish white appearance of RR12. Further, Gram staining showed all the isolates were Gram negative strains. All the variabilities among the endophyte colonies are listed in Table 1.

3.2. Biochemical characterizations of bacterial isolates

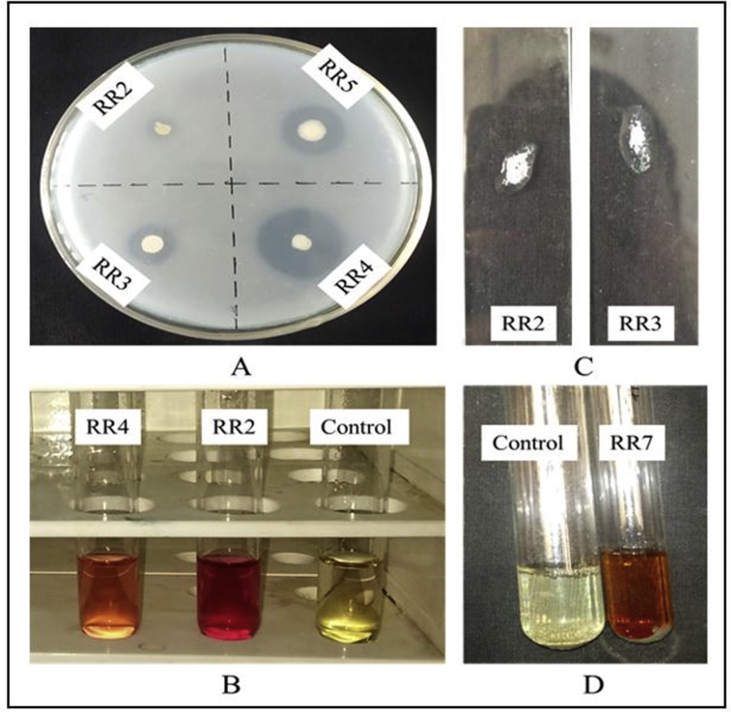

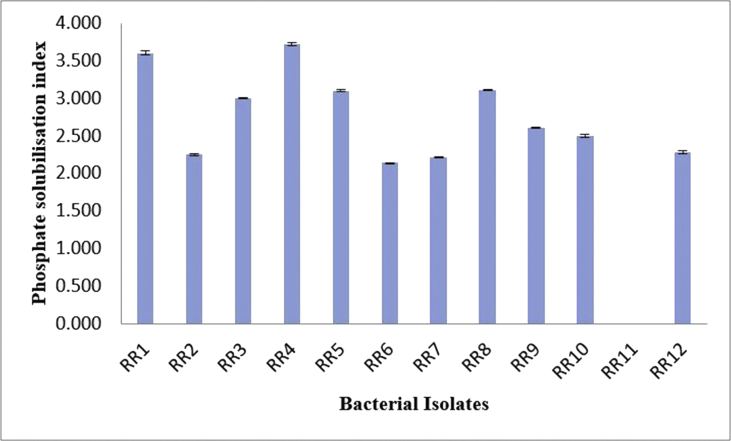

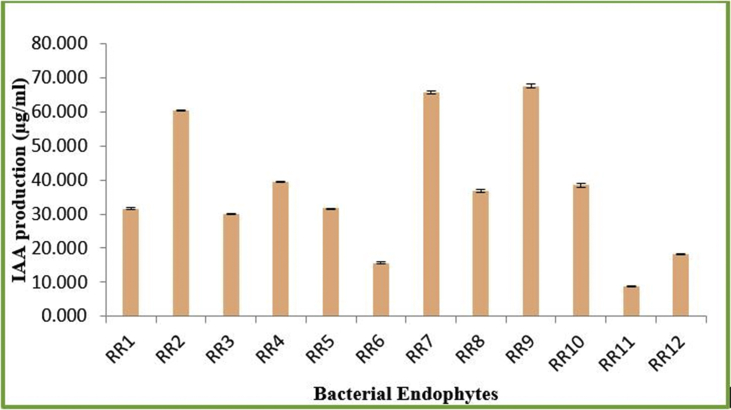

Biochemical characterization of the endophytic isolates was based on phosphate solubility index, production of indole acetic acid (IAA), ammonia and HCN as well as catalase activity (Figure 1). It was observed that almost all the strains showed considerable, yet varied, phosphate solubilizing capacity except RR11. The solubilization index of phosphate was however, more prominent in the case of RR4 (3.714) followed by RR1 (3.6) (Figure 2). Similarly, production of IAA was also evident in all the endophytic strains. While, RR9 exhibited highest production of IAA (67.636 μg/ml), strain RR11 (8.818 μg/ml) showed considerably low IAA production compared to other strains. Additionally, RR7 (65.636 μg/ml) and RR2 (60.273 μg/ml) also displayed high IAA biosynthesis as well (Figure 3). Conversely, ammonia production was only detectable in RR7 whereas, all other strains displayed negative results for HCN production. The catalase activity was also observed to be a prime trait in all the endophytes, except RR1. Qualitative assessment displayed enhanced catalase activity in RR2, RR4, RR7 and RR10, while lower activity for the enzyme was recorded in RR3, RR6 and RR12. In addition, RR5 and RR11 also showed optimum catalase activity (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Biochemical characterizations of the bacterial endophytes. A. Phosphate solubilization. B. IAA production. C. Catalase production. D. Ammonia production.

Figure 2.

Phosphate solubilizing index of the bacterial isolates.

Figure 3.

IAA production of the bacterial isolates.

Table 2.

Biochemical characterizations of bacterial isolates.

| Bacterial isolates | Ammonia production | HCN production | Catalase activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR1 | - | - | - |

| RR2 | - | - | +++ |

| RR3 | - | - | + |

| RR4 | - | - | +++ |

| RR5 | - | - | ++ |

| RR6 | ˗ | - | + |

| RR7 | +++ | - | +++ |

| RR8 | ˗ | - | +++ |

| RR9 | - | - | +++ |

| RR10 | - | - | +++ |

| RR11 | - | - | ++ |

| RR12 | - | - | + |

“-” indicates no production, “+” indicates positive production.

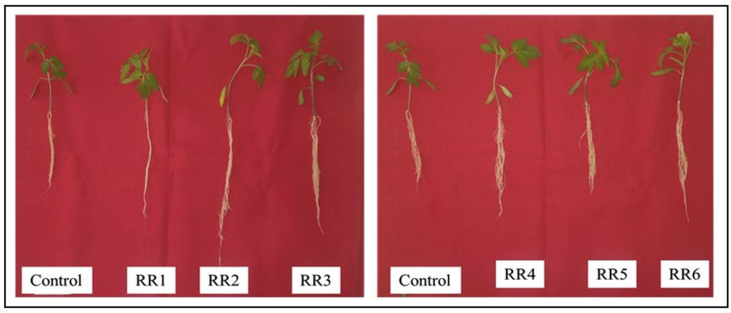

3.3. Plant growth promotion activity by endophytic bacteria

Analysis of growth promotion by endophytic bacteria depicted improvement in growth parameters compared to the control plants for most of the strains. Percent seed germination after endophyte inoculation was of 100% for strains RR2, RR3, RR4, RR6 and RR11. Similarly, the treatment with RR1 showed best increment in root length by 58.5% followed by RR4 treated plant having 54.6% increase in the root length. It was also observed that RR2 showed best shoot length increase of 86.8% followed by 50.01% increase in RR10 inoculated plant with respect to control. Also, other strains showed moderate increase in root and shoot lengths. Significant differences in vigour index were also exhibited in plants inoculated with RR2 and RR4 showing maximum increase, whereas, RR5 treated plant had low vigour index compared to control (Figure 4). Nevertheless, all plants treated with different isolates had appreciable vigour value above the control. Further, the ratios of root:shoot lengths were also obtained which displayed RR1 having best value with respect to control while, all other strains were on the lower side when compared to control (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Vigour index of endophytes inoculated plants.

Table 3.

Plant growth promotion activity by endophytic bacteria.

| Bacterial isolates | Germination (%) | Root length (cm) | Shoot length (cm) | Vigour index | Root:Shoot ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR1 | 60 | 14.900 ± 2.551b | 4.667 ± 0.812a | 1174.020ab | 3.205 ± 0.096 |

| RR2 | 100 | 13.533 ± 3.004ab | 8.467 ± 0.203b | 2200.000e | 1.597 ± 0.349 |

| RR3 | 100 | 13.333 ± 1.169ab | 6.067 ± 0.434a | 1940.033cde | 2.225 ± 0.280 |

| RR4 | 100 | 14.533 ± 0.925b | 6.133 ± 0.393a | 2066.600de | 2.406 ± 0.293 |

| RR5 | 60 | 10.633 ± 1.128ab | 4.900 ± 0.504a | 931.980a | 2.197 ± 0.290 |

| RR6 | 100 | 11.633 ± 0.690ab | 5.567 ± 0.961a | 1720.000cde | 2.191 ± 0.295 |

| RR7 | 80 | 13.333 ± 1.236ab | 5.933 ± 0.546a | 1541.280bc | 2.250 ± 0.108 |

| RR8 | 80 | 13.067 ± 0.970ab | 6.467 ± 0.376ab | 1562.720bc | 2.051 ± 0.273 |

| RR9 | 80 | 13.000 ± 0.058ab | 6.400 ± 0.173ab | 1552.000bc | 2.034 ± 0.061 |

| RR10 | 80 | 12.967 ± 0.385ab | 6.800 ± 0.834ab | 1581.360bcd | 1.971 ± 0.266 |

| RR11 | 100 | 12.367 ± 1.049ab | 6.500 ± 0.667ab | 1886.700cde | 1.911 ± 0.077 |

| RR12 | 80 | 12.967 ± 0.650ab | 5.833 ± 0.426a | 1504.000bc | 2.234 ± 0.092 |

| Control | 80 | 9.400 ± 1.519a | 4.533 ± 1.509a | 1114.640ab | 2.561 ± 0.735 |

Values are mean of three replicates ± SE. Significant of variance (p < 0.05) is analyzed by Duncan grouping. Values within the same column with different letters are significantly different.

3.4. Effect on biomass production

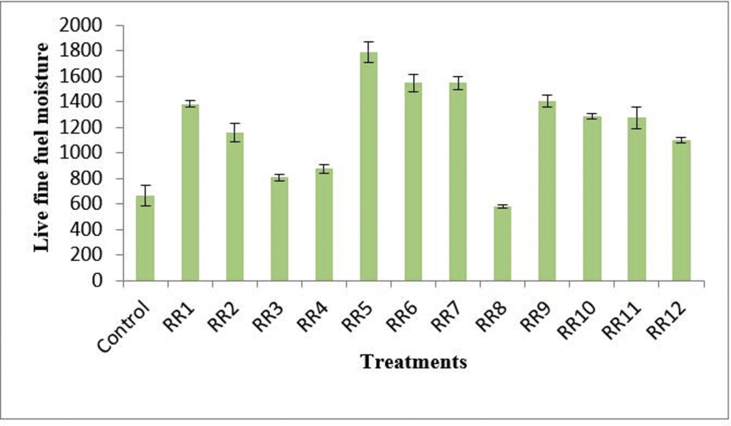

Evaluation of the effect of endophytic bacteria on the biomass of root and shoot showed insignificant alterations in the root biomass (both dry and fresh weight) compared to control. The changes in fresh and dry weight biomass of shoot was also found insignificant, however, the inoculation of RR8 showed increase of 75% in shoot dry biomass followed by RR3 having 44.2% increase than the control. Substantial rise in live fine fuel moisture content of shoot was also observed on inoculation of plants with endophytic bacterial isolates. The treatment RR5 showed the best live fine fuel moisture (LFFM) content of shoot followed by RR6 and RR7 compared to the control (Figure 5). The observations are enlisted in detail in the Table 4.

Figure 5.

LFFM content of the treatments.

Table 4.

Effect bacterial isolates on plant biomass production.

| Bacterial isolates | Root weight (g) |

Shoot weight (g) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Dry | Fresh | Dry | |

| RR1 | 0.124 ± 0.011a | 0.014 ± 0.005a | 0.626 ± 0.022a | 0.042 ± 0.002ab |

| RR2 | 0.428 ± 0.061a | 0.021 ± 0.004a | 0.824 ± 0.067a | 0.066 ± 0.003ab |

| RR3 | 0.496 ± 0.125a | 0.021 ± 0.004a | 0.670 ± 0.132a | 0.075 ± 0.017ab |

| RR4 | 0.441 ± 0.133a | 0.017 ± 0.005a | 0.586 ± 0.074a | 0.061 ± 0.011ab |

| RR5 | 0.211 ± 0.064a | 0.013 ± 0.006a | 0.608 ± 0.169a | 0.046 ± 0.013ab |

| RR6 | 0.468 ± 0.212a | 0.020 ± 0.001a | 0.552 ± 0.181a | 0.042 ± 0.017a |

| RR7 | 0.334 ± 0.213a | 0.023 ± 0.009a | 0.697 ± 0.251a | 0.061 ± 0.022ab |

| RR8 | 0.439 ± 0.113a | 0.023 ± 0.010a | 0.636 ± 0.252a | 0.091 ± 0.032b |

| RR9 | 0.260 ± 0.004a | 0.017 ± 0.001a | 0.816 ± 0.080a | 0.054 ± 0.002ab |

| RR10 | 0.346 ± 0.010a | 0.022 ± 0.003a | 0.808 ± 0.072a | 0.060 ± 0.005ab |

| RR11 | 0.471 ± 0.193a | 0.025 ± 0.007a | 0.683 ± 0.145a | 0.054 ± 0.011ab |

| RR12 | 0.251 ± 0.119a | 0.021 ± 0.004a | 0.629 ± 0.158a | 0.051 ± 0.005ab |

| Control | 0.161 ± 0.007a | 0.026 ± 0.003a | 0.386 ± 0.077a | 0.052 ± 0.009ab |

Values are mean of three replicates ± SE. Significant of variance (p < 0.05) is analyzed by Duncan grouping. Values within the same column with different letters are significantly different.

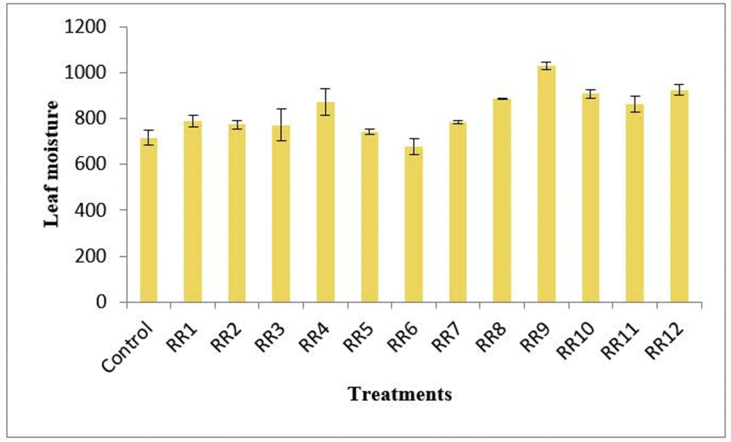

3.5. Effect on leaf variables

Evaluation of five leaf variables i.e. leaf number, leaf area, relative water content (RWC), leaf dry matter content (LDMC) and leaf moisture (LM) were also analyzed. The difference between the leaf counts was observed to be insignificant, although RR2 had the highest leaf count among all the treatments. In addition, the inoculant RR7 escalated the leaf area by maximum. The RWC in leaves had an insignificant increase after treatment. The treatment RR6 was observed to impart the highest LDMC with 29.27% increment that was followed by RR5 and RR2 with an increase of 18.29% compared to control. The treatment RR9 further, illustrated raise in leaf moisture content by 43.74% compared to the control plant (Figure 6). The detailed observations are enlisted in Table 5.

Figure 6.

Leaf moisture content of the treatments.

Table 5.

Effect of bacterial isolates on leaf variables.

| Bacterial Isolates | Leaf number | Leaf area (cm2) | Relative water content (%) | Leaf dry matter content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR1 | 9 ± 1.203a | 3.540 ± 0.467ab | 79.349 ± 2.029ab | 0.092 ± 0.004 |

| RR2 | 13 ± 1.455a | 2.680 ± 0.798ab | 82.447 ± 5.396b | 0.097 ± 0.009 |

| RR3 | 12 ± 0.883a | 1.495 ± 0.377a | 72.094 ± 8.697ab | 0.088 ± 0.008 |

| RR4 | 11 ± 0.334a | 2.730 ± 0.964ab | 77.848 ± 3.917ab | 0.084 ± 0.008 |

| RR5 | 12 ± 2.084a | 1.820 ± 0.695ab | 79.384 ± 1.045ab | 0.097 ± 0.003 |

| RR6 | 9 ± 1.203a | 2.493 ± 0.713ab | 79.190 ± 1.967ab | 0.106 ± 0.010 |

| RR7 | 11 ± 1.734a | 4.365 ± 1.705b | 79.739 ± 4.938ab | 0.092 ± 0.004 |

| RR8 | 10 ± 1.529a | 3.200 ± 0.642ab | 72.065 ± 11.436ab | 0.075 ± 0.011 |

| RR9 | 11 ± 0.883a | 2.525 ± 0.104ab | 82.913 ± 2.792b | 0.075 ± 0.004 |

| RR10 | 12 ± 0.000a | 3.378 ± 1.036ab | 84.035 ± 0.446b | 0.085 ± 0.003 |

| RR11 | 10 ± 2.002a | 3.780 ± 0.803ab | 82.535 ± 2.913b | 0.088 ± 0.007 |

| RR12 | 11 ± 1.203a | 2.088 ± 0.525ab | 84.161 ± 1.915b | 0.084 ± 0.002 |

| Control | 8 ± 2.188a | 1.743 ± 0.610ab | 63.422 ± 4.429a | 0.082 ± 0.001 |

Values are mean of three replicates ± SE. Significant of variance (p < 0.05) is analyzed by Duncan grouping. Values within the same column with different letters are significantly different.

4. Discussion

The internal tissues of plants provide a magnificent niche for the bacterial endophytes which positively induces modulations in host physiology and enhance health and productivity of the plants (Amaresan et al., 2012). The present study investigated the effect of twelve endophytic bacterial strains, isolated from different plants, on the growth of Solanum lycopersicum (tomato). Inside any eukaryotic host the endophytes (bacteria) are subjected to harsh conditions because of limited availability of space, nutrients and host mediated control on cellular propagations. In such conditions it is possible that ROS production and simultaneous oxidation bursts may occur inside the endophytic cell. In such conditions enhanced catalase activity may be crucial in relieving oxidation stress. Hence, allowing survival of endophyte within the host.

In a view to screen the most effective endophyte, various physiological and morphological parameters that confers plant growth was analyzed upon incubating plants with each of these isolates. Nevertheless, among all the parameters analyzed here, the vigour index was selected to be the primary deciding factor to screen the potential endophyte of all. The genuine reason behind selecting vigour index is its direct dependence on three vital growth attributes i.e. shoot length, root length and germination percentage (Abdul-Baki and Anderson, 1973). In our study it was observed that the vigour index of plant inoculated with endophyte RR2 and RR4 were having an increment of about 97% and 85%, respectively than control which was recorded as highest. Therefore, it was ascertained that RR2 and RR4 were the best endophytic isolates. This significantly high vigour index may correspond to the increment in total seedling length (summation of shoot and root length) and germination percentage in the plants inoculated with RR2 and RR4, which displayed 100% germination along with considerably high seedling lengths.

It was also observed that the elongation of root with respect to shoot was comparable in plant inoculated with RR2 than other plants having different endophytic strains as well as control. This suggested relative proportional growth of both below and above ground parts of the plant inoculated with RR2. The prime reason behind this may correspond to the amount of IAA produced by the endophyte inside the host plant (Shi et al., 2009). Although, highest amount of IAA was produced by RR9, yet considerable amount of IAA biosynthesis (60.273 μg/ml) was also observed by RR2. In congruence to our observation, IAA producing endophytic bacteria shows significant increase in growth in variety of plants (Sheng et al., 2008). Further, increased vigour index and seedling length was also observed in rice plants inoculated with IAA producing Rhizobium strains (Yanni et al., 2001). Recently, in tomato it was observed that biosynthesis of IAA by Sphingomonas sp. promoted plant growth (Khan et al., 2014). IAA in plants stimulates cell division, elongation and differentiation (Redman et al., 2011; Davičre and Achard, 2013). Bacteria producing IAA, therefore, exert growth-promoting effects during its interaction with the plant (Barazani and Friedman, 1999; Verma et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004). Most of the strains producing IAA are generally subsumed within the Genera like Bacillus, Microbacterium, Agromyces or Paenibacillus (Lata et al., 2006; Khan and Doty, 2009; Hussain and Hasnain, 2011; Bal et al., 2013; Naveed et al., 2013; Nagata et al., 2015; Weyens et al., 2014). However, the impact of IAA varies with the plant organ and developmental stages. The formation of adventitious root and improvement of root xylem and phloem is induced by IAA, while on the above ground parts enhancement in photosynthetic apparatus, pigment biosynthesis, flowering and fruiting are also influenced by IAA (Duca et al., 2014; Selvakumar et al., 2014; Tivendale et al., 2014). Therefore, the high amount of IAA produced by RR2 may have an array of advantages to the host, like enhanced nutrient uptake (Ahemad and Kibret, 2014) and photosynthesis, which cumulatively leads to better vigour index. Furthermore, it was observed that most of the strains were Gram negative which supports the study of Lindow et al. (1998) reporting most of the IAA producing endophytes belonging to Gram negative group.

The bacterial endophytic strain RR4 displayed high phosphate solubility index (3.714) resulting in considerable increment in vigour upon inoculation in tomato plant, than control. It can be presumed that the escalated phosphate solubilizing capacity may have led to rise in vigour index. Since phosphorus plays a vital role in quite a number of plant physiological activities like photosynthesis and cell division (Gupta et al., 2012), therefore its deficiency restricts the growth and development in plants. Hence, natural phosphate solubilization by microbial cells is highly essential for making insoluble soil phosphorus available to the plants. The major mechanism followed by the bacterial endophytes to solubilize inorganic phosphate is by producing organic acids. Pseudomonas sp., Burkholderia cepacia produce gluconic acid to solubilize inorganic phosphate and make it readily available for the host plants (Goldstein, 1994). Bacillus subtilis CB8A produce oxalic acid, gluconic acid, formic acid, 2-ketogluconic acid, citric acid, and fumaric acid which are involved in mineral solubilisation (Mehta et al., 2013). The organic acids decrease the pH and form complex with metal ions of insoluble phosphate which assists the process of solubilzation. However, a lower phosphate solubilization displayed by RR2, despite of inducing highest vigour index may suggest the involvement of various factors in array of permutations subsequently in determining plant growth. In the case of RR2 and RR4 strains, the IAA biosynthesis and phosphate solubilization seemed to have influenced plant growth, but the high IAA biosynthesis and phosphate solubilizing efficacy have greater say in the vigour index displayed upon inoculation of former and later strains respectively, in tomato. Similar plant growth induction were observed by high phosphate solubilizing and high IAA producing root endophyte Enterobacter cloacae, isolated from Kenyan basmati rice (Mbai et al., 2013). In addition, both RR2 and RR4 displayed high catalase activity, suggesting the ability of these isolates to survive adverse conditions and intracellular oxidative bursts.

Although no significant difference was detected in root dry biomass, yet, the plant inoculated with RR8 (0.091 g), RR2 (0.066 g) and RR4 (0.061 g) showed considerably higher shoot dry biomass than control, indicating possible enhancement in photosynthate assimilation, thus, biomass aggregation (Zerihun et al., 1998). Lee et al. (2020) showed that Bacillus subtilis strain L1 when inoculated in the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana, the seedlings showed notable increase in biomass. Nonetheless, environmental and technical variables significantly influence the biomass determination over the impact of endophytes (Bashan and De-Bashan, 2005).

The moisture content of shoot and foliage largely depends on the relative water uptake through roots and transpiration loss (Pinol et al., 1998). LFFM denotes the shoot water content in relation to its dry mass under field conditions (Saura-Mas et al., 2009). It is also used as an indicator of combustibility (Pinol et al., 1998; Viegas et al., 2001; Andrews and Bevins, 2003; Castro et al., 2003). The present study portrayed that inoculation of endophytic isolates can increase the shoot moisture which keeps it rehydrated and can also contribute in biomass formation. Additionally, RR2 (1159.460) and RR4 (874.671) also showed noteworthy increment in LFFM but the highest value for LFFM was observed in plant inoculated with RR5.

Analyzing the impact of the endophytes on the leaf variables displayed maximum number of leaves in RR2 inoculated plants with significant increase in leaf area. Despite, a similar increase in leaf area was also detected in RR7. Another significant feature exhibited by RR7 was the production of ammonia, which can be used as a chief nitrogen source by the host for its growth and productivity (Ahmad et al., 2008). Jang et al. (2018) suggested significant improvement in accessibility and acquisition of nitrogen in Bacillus subtilis JS inoculated plants. Although, over production of ammonia may cause ammonium toxicity by accumulation of NH4+ ion in the roots of tomato causing significant biomass reduction (Cruz et al., 2006; Setien et al., 2014). Ammonium toxicity causes imbalance in uptake of NH4+ion and its assimilation (Vega-Mas et al., 2017). Bacterial endophytes produce HCN in a suitable quantity which is a powerful biocontrol agent to protect the host plants from biotic stress and indirectly enhance plant growth (Glick and Pasternak, 2003). Ammonia production is also accountable for indirect growth promotion of plants and act as triggering factor for suppressing plant pathogens (Minaxi et al., 2012). So, these growth promoting attributes are considered significant while screening the bacterial endophytes. However, in the present study most of the endophytic strains showed negative result for HCN and ammonia production. The increase in the leaf area may broaden effective area for light harvesting and photosynthesis, leading to better plant productivity (Faria et al., 2013). Moreover, RWC, a plastic trait indicating leaf water status, suggested that the treatment plants exhibited higher and more stable water conservation strategy than the control. Plant having RR2 and RR4 endophytes exhibited 30% and 22.7% increase in RWC respectively. In this context, the results obtained in the present study, indicated that application of the bacterial strains had a prominent impact on the roots length which might have influenced the RWC in the plant. Lateral roots always help plants in short distance exploitation for nutrients and in water transport from soil to the vasculature in young and adult plants as they increase the root surface area. Literature well documents that root hairs could increase the radial zone of impact by 0.4 mm (Daly et al., 2016) and can overall account for 50% of the total uptake flux in comparison to the rest of the plant root system (Carminati et al., 2017). It was also reported that treatment with Pseudomonas putida51 and Bacillus52 strains induced soil microaggregation which led to increase in soil water content consequently escalating the water availability which was indicated by high RWC in the leaves of Eclipta prostrate (Sinha and Raghuwanshi, 2016). Steady tissue hydration enhances drought tolerance in plants. Zhu (2019) reported that bacterial endophytes improve the process of imbibition increasing RWC significantly that helps the host plant to tolerate osmotic stress. In addition, increasing LDMC in the treatment plants show that the endophyte played a greater role in increasing the dry mass of the leaf and the maximum water retained since, LDMC largely depends on these two factors (Garnier et al., 2001). A consistent increase in LDMC suggests that the proportion of dry matter in relation to saturated weight is larger. It also indicates slower production of biomass, a longer leaf lifespan and a more efficient conservation of nutrients (Grime et al., 1997). In essence, among all the endophytes RR2 and RR4 can be considered as the most suitable endophyte to be utilized for growth of tomato.

5. Conclusion

The bacterial endophytes have a great potential to contribute towards the growth and development of plants. To explore their prospective applications, it is essential to understand the bacterial interaction with the host plant. In the present study, efforts were made to isolate and characterize twelve endophytic bacteria and were screened on the basis of their growth promoting attributes and their effects on the growth of Solanum lycopersicum (tomato). Among them the isolates RR2 and RR4 were proficient in all the growth parameters and further use of these as biofertilizer can contribute towards sustainable agriculture. However this study also provides scope for future scientific investigations.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Riddha Dey: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Richa Raghuwanshi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to ICAR - Indian Institute of Vegetable Research (IIVR), Varanasi for providing us the tomato seeds.

References

- Abdul-Baki A.A., Anderson J.D. Vigor determination in soybean seed by multiple criteria 1. Crop Sci. 1973;13(6):630–633. [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M., Kibret M. Mechanisms and applications of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: current perspective. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2014;26:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F., Ahmad I., Khan M.S. Screening of free-living rhizospheric bacteria for their multiple plant growth-promoting activities. Microbiol. Res. 2008;163:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S.S., Andersen M.N., Naveed M., Zahir Z.A., Liu F. Interactive effect of biochar and plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes on ameliorating salinity stress in maize. Funct. Plant Biol. 2015;42(8):770–781. doi: 10.1071/FP15054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaresan N., Jayakumar V., Kumar K., Thajuddin N. Isolation and characterization of plant growth promoting endophytic bacteria and their effect on tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) and chilli (Capsicum annuum) seedling growth. Ann. Microbiol. 2012;62(2):805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews P.L., Bevins C.D. Proceedings of the Second International Wildland Fire Ecology and Fire Management congress. 2003. Behave plus fire modeling system version 2: overview; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Arcand M.M., Schneider K.D. Plant-and microbial-based mechanisms to improve the agronomic effectiveness of phosphate rock: a review. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2006;78(4):791–807. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652006000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam C., Gayathri P. Studies on bioprospecting of endophytic bacteria from the medicinal plant of Andrographis paniculata for their antimicrobial activity and antibiotic susceptibility pattern. Int. J. Curr. Pharmaceut. Res. 2010;2(4):63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bal H.B., Das S., Dangar T.K., Adhya T.K. ACC deaminase and IAA producing growth promoting bacteria from the rhizosphere soil of tropical rice plants. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013;53(12):972–984. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201200445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldani J.I., Olivares F.L., Hemerly A.S., Reis F.B., Oliveira A.L.M., Baldani V.L.D., Goi S.R., Reis V.M., Dobereiner J. Biological Nitrogen Fixation for the 21st century. Springer; Dordrecht: 1998. Nitrogen-fixing endophytes: recent advances in the association with graminaceous plants grown in the tropics; pp. 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bangera M.G., Thomashow L.S. Characterization of a genomic locus required for synthesis of the antibiotic 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol by the biological control agent Pseudomonas fluorescens Q2-87. Mol. Plant-microbe In. 1996;9(2):83–90. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-9-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazani O., Friedman J. Is IAA the major growth factor secreted from plant growth mediating bacteria. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999;25:2397–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Bashan Y., De-Bashan L.E. Plant growth-promoting. Encycl. Soils Environ. 2005;1:103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee R.B., Singh A., Mukhopadhyay S.N. Use of nitrogen-fixing bacteria as biofertiliser for non-legumes: prospects and challenges. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;80(2):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bric J.M., Bostock R.M., Silverstone S.E. Rapid in situ assay for indole acetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991;57(2):535–538. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.535-538.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccino J.G., Sherman N. third ed. Rockland Community College, Suffern; New York: 1992. Microbiology; A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Carminati A., Passioura J.B., Zarebanadkouki M., Ahmed M.A., Ryan P.R., Watt M., Delhaize E. Root hairs enable high transpiration rates in drying soils. New Phytol. 2017;216:771–781. doi: 10.1111/nph.14715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro F.X., Tudela A., Sebastia M.T. Modeling moisture content in shrubs to predict fire risk in Catalonia (Spain) Agric. For. Meteorol. 2003;116:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary D.K., Kasotia A., Jain S., Vaishnav A., Kumari S., Sharma K.P., Varma A. Bacterial-mediated tolerance and resistance to plants under abiotic and biotic stresses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2016;35(1):276–300. [Google Scholar]

- Compant S., Duffy B., Nowak J., Clement C., Barka E.A. Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71(9):4951–4959. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.4951-4959.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz C., Bio A.F.M., Domínguez-Valdivia M.D., Aparicio-Tejo P.M., Lamsfus C., Martins-Louçao M.A. How does glutamine synthetase activity determine plant tolerance to ammonium? Planta. 2006;223(5):1068–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly K.R., Keyes S.D., Masum S., Roose T. Image-based modelling of nutrient movement in and around the rhizosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:1059–1070. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davičre J.M., Achard P. Gibberellin signaling in plants. Development. 2013;140:1147–1151. doi: 10.1242/dev.087650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duca D., Lorv J., Patten C.L., Rose D., Glick B.R. Indole-3-acetic acid in plant–microbe interactions. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106(1):85–125. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0095-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudeja S.S., Giri R., Saini R., Suneja-Madan P., Kothe E. Interaction of endophytic microbes with legumes. J. Basic Microbiol. 2012;52(3):248–260. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edi-Premono M., Moawad M.A., Vleck P.L.G. Effect of phosphate solubilizing Pseudomonas putida on the growth of maize and its survival in the rhizosphere. Indones. J. Crop Sci. 1996;11:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2017. Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations.Tomato Production Global Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Faria D.C., Dias A.C.F., Melo I.S., de Carvalho Costa F.E. Endophytic bacteria isolated from orchid and their potential to promote plant growth. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;29(2):217–221. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne-Bourque F., Mayer B.F., Charron J.B., Vali H., Bertrand A., Jabaji S. Accelerated growth rate and increased drought stress resilience of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon colonized by Bacillus subtilis B26. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier E., Shipley B., Roumet C., Laurent G. A standardized protocol for the determination of specific leaf area and leaf dry matter content. Funct. Ecol. 2001;15(5):688–695. [Google Scholar]

- Glick B.R., Pasternak J.J. Plant growth promoting bacteria. In: Glick B.R., Pasternak J.J., editors. Molecular Biotechnology Principles and Applications of Recombinant DNA. third ed. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 436–454. [Google Scholar]

- Glickmann E., Dessaux Y. A critical examination of the specificity of the salkowski reagent for indolic compounds produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61(2):793–796. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.793-796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A.H. Involvement of the quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase in the solubilization of exogenous phosphates by gram-negative bacteria. In: Gorini A., Torrini A., Yagil E., Silver S., editors. Phosphate in Microorganisms: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press; Washington: 1994. pp. 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gothwal R.K., Nigam V.K., Mohan M.K., Sasmal D., Ghosh P. Screening of nitrogen fixers from rhizospheric bacterial isolates associated with important desert plants. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2008;6(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Govender V., Aveling T.A.S., Kritzinger Q. The effect of traditional storage methods on germination and vigour of maize (Zea mays L.) from northern Kwazulu- Natal and southern Mozambique. South Afr. J. Bot. 2008;74(2):190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Grime J.P., Thompson K., Hunt R., Hodgson J.G., Cornelissen J.H., Rorison I.H., Hendry G.A., Ashenden T.W., Askew A.P., Band S.R., Booth R.E. Integrated screening validates primary axes of specialisation in plants. Oikos. 1997;1:259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M., Kiran S., Gulati A., Singh B., Tewari R. Isolation and identification of phosphate solubilizing bacteria able to enhance the growth and aloin-A biosynthesis of Aloe barbadensis Miller. Microbiol. Res. 2012;167:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain A., Hasnain S. Interactions of bacterial cytokinins and IAA in the rhizosphere may alter phytostimulatory efficiency of rhizobacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;27:2645. [Google Scholar]

- Jang J.H., Kim S.H., Khaine I., Kwak M.J., Lee H.K., Lee T.Y., Lee W.Y., Woo S.Y. Physiological changes and growth promotion induced in poplar seedlings by the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis JS. Photosynthetica. 2018;56:1188–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.M., Joo G.J., Hamayun M., Na C.I., Shin D.H., Kim H.Y., Hong J.K., Lee I.J. Gibberellin production and phosphate solubilization by newly isolated strain of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and its effect on plant growth. Biotechnol. Lett. 2009;31(2):277–281. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9867-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z., Doty S.L. Characterization of bacterial endophytes of sweet potato plants. Plant Soil. 2009;322:197. [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.L., Waqas M., Kang S.M., Al-Harrasi A., Hussain J., Al-Rawahi A., Al-Khiziri S., Ullah I., Ali L., Jung H.Y., Lee I.J. Bacterial endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 produces gibberellins and IAA and promotes tomato plant growth. J. Microbiol. 2014;52(8):689–695. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper J.W., Schroth M.N. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and plant growth under gnotobiotic conditions. Phytopathology. 1981;71(6):642–644. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi D.Y., Palumbo J.D. Bacterial endophytes and their effects on plants and uses in agriculture. In: Bacon C.W., White J.F., editors. Microbial Endophytes. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York: 2000. pp. 199–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lata H., Li X.C., Silva B., Moraes R.M., Halda-Alija L. Identification of IAA-producing endophytic bacteria from micropropagated Echinacea plants using 16S rRNA sequencing. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2006;85:353–359. [Google Scholar]

- Latif Khan A., Ahmed Halo B., Elyassi A., Ali S., Al-Hosni K., Hussain J., Al-Harrasi A., Lee I.J. Indole acetic acid and ACC deaminase from endophytic bacteria improves the growth of Solarium lycopersicum. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2016;19(3):58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Flores-Encarnacion M., Contreras-Zentella M., Garcia F.L., Escamilla J.E., Kennedy C. Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis is deficient in Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus strains with mutations in cytochrome C biogenesis genes. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:5384–5391. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5384-5391.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Trịnh C.S., Lee W.J., Jeong C.Y., Truong H.A., Chung N., Kang C.S., Lee H. Bacillus subtilis strain L1 promotes nitrate reductase activity in Arabidopsis and elicits enhanced growth performance in Arabidopsis, lettuce, and wheat. J. Plant Res. 2020;133(2):231–244. doi: 10.1007/s10265-019-01160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindow S.E., Desurmont C., Elkins R., Mccourty G., Clark E., Maria T.B. Occurrence of indole-3-acetic Acid-producing bacteria on pear trees and their association with fruit russet. Phytopathology. 1998;88:1149–1157. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.11.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock H. Production of hydrocyanic acid by bacteria. Physiol. Plantarum. 1948;1:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Long H.H., Schmidt D.D., Baldwin I.T. Native bacterial endophytes promote host growth in a species-specific manner; phytohormone manipulations do not result in common growth responses. PloS One. 2008;3(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucy M., Reed E., Glick B.R. Applications of free living plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2004;86(1):1–25. doi: 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000024903.10757.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Rajkumar M., Zhang C., Freitas H. Beneficial role of bacterial endophytes in heavy metal phytoremediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2016;174:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbai F.N., Magiri E.N., Matiru V.N., Nganga J., Nyambati V.C.S. Isolation and characterisation of bacterial root endophytes with potential to enhance plant growth from kenyan basmati rice. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2013;3(4):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P., Walia A., Chauhan A., Kulshrestha S., Shirkot C.K. Phosphate solubilization and plant growth promoting potential by stress tolerant Bacillus sp. isolated from rhizosphere of apple orchards in trans Himalayan region of Himachal Pradesh. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013;163:430–443. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-Blanco J., Bakker P.A. Interactions between plants and beneficial Pseudomonas spp.: exploiting bacterial traits for crop protection. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2007;92(4):367–389. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minaxi N.L., Yadav R.C., Saxena J. Characterization of multifaceted Bacillus sp. RM-2 for its use as plant growth promoting bioinoculant for crops grown in semi-arid deserts. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012;59:124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed H.I., Gomaa E.Z. Effect of plant growth promoting Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens on growth and pigment composition of radish plants (Raphanus sativus) under NaCl stress. Photosynthetica. 2012;50:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S., Yamaji K., Nomura N., Ishimoto H. Root endophytes enhance stress-tolerance of Cicutavirosa L. growing in a mining pond of eastern Japan. Plant Species Biol. 2015;30(2):116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal C.S. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;170(1):265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M., Mitter B., Yousaf S., Pastar M., Afzal M., Sessitsch A. The endophyteEnterobacter sp. FD17: a maize growth enhancer selected based on rigorous testing of plant beneficial traits and colonization characteristics. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2013;50:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M., Hussain M.B., Zahir Z.A., Mitter B., Sessitsch A. Drought stress amelioration in wheat through inoculation with Burkholderia phytofirmans strain PsJN. Plant Growth Regul. 2014;73:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M., Mitter B., Reichenauer T.G., Wieczorek K., Sessitsch A. Increased drought stress resilience of maize through endophytic colonization by Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN and Enterobacter sp. FD17. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014;97:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi S., Dash D., Rath C.C. Characterization of endophytic bacteria with plant growth promoting activities isolated from six medicinal plants. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 2018;6(5):782–791. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova A.S., Leontieva M.R., Smirnova T.A., Kolomeitseva G.L., Netrusov A.I., Tsavkelova E.A. Colonization strategy of the endophytic plant growth-promoting strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Klebsiella oxytoca on the seeds, seedlings and roots of the epiphytic orchid, Dendrobiumnobile Lindl. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017;123(1):217–232. doi: 10.1111/jam.13481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinol J., Filella I., Ogaya R., Penuelas J. Ground-based spectroradiometric estimation of live fine fuel moisture of Mediterranean plants. Agr. For. Meteorol. 1998;90:173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Redman R.S., Kim Y.O., Woodward C.J.D.A., Greer C., Espino L., Doty S.L., Rodriguez R.J. Increased fitness of rice plants to abiotic stress via habitat adapted symbiosis: a strategy for mitigating impacts of climate change. PloS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Solís D., Zetter-Salmón E., Contreras-Pérez M., del Carmen Rocha-Granados M., Macías-Rodríguez L., Santoyo G. Pseudomonas stutzeri E25 and Stenotrophomonasmaltophilia CR71 endophytes produce antifungal volatile organic compounds and exhibit additive plant growth-promoting effects. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018;13:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblueth M., Martínez-Romero E. Bacterial endophytes and their interactions with hosts. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19(8):827–837. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R.P., Germaine K., Franks A., Ryan D.J., Dowling D.N. Bacterial endophytes: recent developments and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;278(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura-Mas S., Shipley B., Lloret F. Relationship between post-fire regeneration and leaf economics spectrum in Mediterranean woody species. Funct. Ecol. 2009;23(1):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz B., Boyle C. What are endophytes? In: Schulz B.J.E., Boyle C.J.C., Sieber T.N., editors. Microbial Root Endophytes. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2006. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar G., Kim K., Hu S., Sa T. Effect of salinity on plants and the role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in alleviation of salt stress. In: Ahmad P., Wani M.R., editors. Physiological Mechanisms and Adaptation Strategies in Plants under Changing Environment. Springer; New York, USApp: 2014. pp. 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Setien I., Vega-Mas I., Celestino N., Calleja-Cervantes M.E., González-Murua C., Estavillo J.M., González-Moro M.B. Root phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and NAD-malic enzymes activity increase the ammonium-assimilating capacity in tomato. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171(5):49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng X.F., Xia J.J., Jiang C.Y., He L.Y., Qian M. Characterization of heavy metal-resistant endophytic bacteria from rape (Brassica napus) roots and their potential in promoting the growth and lead accumulation of rape. Environ. Pollut. 2008;156(3):1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Lou K., Li C. Promotion of plant growth by phytohormone-producing endophytic microbes of sugar beet. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2009;45(6):645–653. [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Lou K., Li C. Growth and photosynthetic efficiency promotion of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) by endophytic bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 2010;105:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s11120-010-9547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S., Raghuwanshi R. Synergistic effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and mycorrhizal helper bacteria on physiological mechanism to tolerate drought in Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2016;10(2):1117–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Su F., Villaume S., Rabenoelina F., Crouzet J., Clément C., Vaillant-Gaveau N., Dhondt-Cordelier S. Different Arabidopsis thaliana photosynthetic and defense responses to hemibiotrophic pathogen induced by local or distal inoculation of Burkholderia phytofirmans. Photosynth. Res. 2017;134(2):201–214. doi: 10.1007/s11120-017-0435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivendale N.D., Ross J.J., Cohen J.D. The shifting paradigms of auxin biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomato news. 2017. http://www.tomatonews.com/en/background 47.html [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Mas I., Pérez-Delgado C.M., Marino D., Fuertes-Mendizábal T., González-Murua C., Márquez A.J., Betti M., Estavillo J.M., González-Moro M.B. Elevated CO2 induces root defensive mechanisms in tomato plants when dealing with ammonium toxicity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58(12):2112–2125. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A., Kukreja K., Pathak D.V., Suneja S., Narula N. In vitro production of plant growth regulators (PGRs) by Azorobacte rchroococcum. Indian J. Microbiol. 2001;41:305–307. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas D.X., Pinol J., Viegas M.T., Ogaya R. Estimating live fine fuels moisture content using meteorologically-based indices. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 2001;10:223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Villareal R. CRC Press; 2019. Tomatoes in the Tropics. [Google Scholar]

- Weyens N., Gielen M., Beckers B., Boulet J., van der Lelie D., Taghavi S., Carleer R., Vangronsveld J. Bacteria associated with yellow lupine grown on a metal-contaminated soil: in vitro screening and in vivo evaluation for their potential to enhance Cd phytoextraction. Plant Biol. 2014;16(5):988–996. doi: 10.1111/plb.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaish M.W., Antony I., Glick B.R. Isolation and characterization of endophytic plant growth-promoting bacteria from date palm tree (Phoenix dactylifera L.) and their potential role in salinity tolerance. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2015;107:1519–1532. doi: 10.1007/s10482-015-0445-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanni Y.G., Rizk R.Y., Abd El-Fattah F.K., Squartini A., Corich V., Giacomini A., de Bruijn F., Rademaker J., Maya-Flores J., Ostrom P., Vega-Hernandez M. The beneficial plant growth-promoting association of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii with rice roots. Funct. Plant Biol. 2001;28(9):845–870. [Google Scholar]

- Zerihun A., McKenzie B.A., Morton J.D. Photosynthate costs associated with the utilization of different nitrogen–forms: influence on the carbon balance of plants and shoot–root biomass partitioning. New Phytol. 1998;138(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. Isolation and identification of Ammodendron bifolium endophytic bacteria and the action mechanism of selected isolates-induced seed germination and their effects on host osmotic-stress tolerance. Arch. Microbiol. 2019;201:431–442. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]