Abstract

The ubiquitous Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin is a key regulator of pathological cardiac hypertrophy whose therapeutic targeting in heart disease has been elusive due to its role in other essential biologic processes. Calcineurin is targeted to diverse intracellular compartments by association with scaffold proteins, including by multivalent A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) that bind PKA and other important signaling enzymes determining cardiac myocyte function and phenotype. Calcineurin anchoring by AKAPs confers specificity to calcineurin function in the cardiac myocyte. Targeting of calcineurin “signalosomes” may provide a rationale for inhibiting the phosphatase in disease.

Keywords: calcineurin, heart, hypertrophy, AKAP

Since the initial discovery in 1998 by Jeffrey Molkentin and Eric Olson that calcineurin (CaN) activation contributes to the induction of pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Molkentin et al., 1998), numerous studies have confirmed the pivotal role of this phosphatase in myocyte signal transduction (Wilkins & Molkentin, 2004). Currently approved pharmacological inhibitors of CaN are immunosuppressant, as the CaN signaling pathway is required for the transcriptional activation of interleukin-2 during T cell activation, therefore precluding their use to oppose cardiac remodeling in chronic cardiovascular diseases. In addition, CaN promotes the survival of cardiac myocytes during ischemia, complicating CaN targeting in heart patients who are typically at risk for myocardial infarction (Bueno et al., 2004). Nevertheless, due to the importance of CaN signaling, the discovery of alternative approaches for CaN therapeutic targeting that might be better tolerated has been a goal of much basic cardiovascular research. In particular, it has become recognized that targeting of CaN to specific subcellular compartments provides a means to regulate its phosphatase activity, as well as provide specificity for substrate dephosphorylation (Li et al., 2011). A-kinase anchoring proteins have been shown to be key regulators of CaN activity in the heart, and the scaffolding of CaN in these signalosomes is important for the regulation of cardiac disease. Here, we will explore key elements of CaN signaling in the cardiac myocyte and highlight how AKAP complexes can regulate CaN activity, potentially informing novel, therapeutically feasible approaches.

Calcineurin Biochemistry

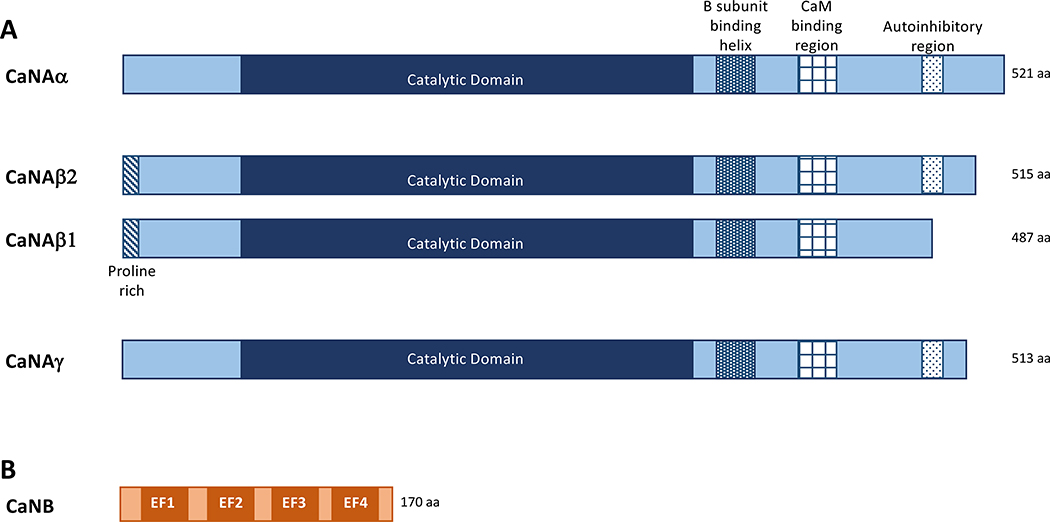

The ubiquitously expressed calcium/calmodulin- (Ca2+/CaM) dependent protein phosphatase PP2B, also known as Calcineurin (CaN) and PPP3, is a heterodimer comprised of a 60 kDa catalytic A-subunit (CaNA) and a 19 kDa regulatory B-subunit (CaNB) (Li et al., 2011; Penny & Gold, 2018). CaNA contains in sequence an N-terminal catalytic domain, a B-subunit binding helix, a CaM-binding domain, followed by a C-terminal autoinhibitory region (AID) (Li et al., 2011). A schematic of the CaN domain structure is found in Figure 1. CaNB contains 4 EF hand domains responsible for binding calcium. Sites 3 and 4 are high affinity calcium-binding domains (KD in the nanomolar range) and constitutively bind calcium in cells. Sites 1 and 2 have 1000-fold lower affinity calcium-binding domains (Kakalis et al., 1995; Gallagher et al., 2001), and act as “calcium sensors”, binding calcium upon cellular stimulation. When all four CaNB sites are occupied, a confirmation change in the holoenzyme promotes the binding of Ca2+/CaM to CaNA and the displacement of the autoinhibitory domain from the catalytic core, resulting in increased phosphatase activity (Li et al., 2011; Li et al., 2016) (See Figure 2).

Figure 1. Schematic describing Calcineurin binding domains.

A. In mammals, three genes encode CaNA (α,β,and γ). The phosphatase catalytic domain, the common B subunit binding domain, CaM binding domain and Autoinhibitory region are depicted as well as the CaNAβ specific proline rich domain. B. Domains of the CaNB subunit.

Figure 2. Activation of Calcineurin.

A. Domains for CaNA and CaNB subunits. B. Model of CaN activation. Binding of calcium to the regulatory “sensor” sites on CaNB initiates a multiple confirmation change that allows binding of a Ca2+/calmodulin complex and a change in the orientation of the AID to expose the active site.

CaN can dephosphorylate many substrates depending upon the cellular context, including diverse transcription factors and ion channels (Li et al., 2011). Perhaps the most well studied substrates are the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) transcription factor family which binds CaN directly and, upon dephosphorylation of multiple N-terminal serine-rich domains, are translocated into the nucleus (Wu et al., 2007). In the heart, this pathway is known to initiate the gene transcription that underlies the induction of cardiac disease and has therefore been the focus of many investigations into CaN function. Three genes (PPP3CA, PPP3CB, and PPP3CC) encode α, β, and γ CaN A-subunit isoforms, of which CaNAα and CaNAβ isoforms are expressed in the heart (Bueno et al., 2002; Li et al., 2011; Parra & Rothermel, 2017). Studies using mice with CaNAα and Aβ genetic deletion have revealed isoform-specific functions in different tissues. For example, CaNAβ knock-out affects cardiac hypertrophy and the function of platelets and pancreas, while CaNAα knock-out has effects upon the hippocampus and keratinocytes (Zhuo et al., 1999; Bueno et al., 2002; Pena et al., 2010; Reddy et al., 2011; Muili et al., 2012; Khatlani et al., 2014). In addition, CaNAβ and CaNAα have differential effects in skeletal muscle, kidney, and T-cells (Chan et al., 2002; Parsons et al., 2003; Gooch, 2006; Manicassamy et al., 2008; Reddy et al., 2011). Notably, although CaNAα and CaNAβ are expressed at similar levels in the normal heart (Bueno et al., 2002), in mice subjected to chronic cardiovascular stress by infusion of either angiotensin II or the α-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine, only CaNAβ mRNA and protein levels are increased, suggesting that this isoform plays a more important role in cardiac hypertrophy (Taigen et al., 2000; Oka et al., 2005). Accordingly, CaNAβ global knock-out mice, that appeared otherwise normal, displayed reduced heart size in the absence of stress and a significant resistance to pressure overload, angiotensin II and catecholamine-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Bueno et al., 2002), attributable at least in part to decreased NFAT activation (Wilkins et al., 2004). As mice globally deficient in CaNAα have significantly limited life spans, studies to determine the requirement for CaNAα in pathological cardiac hypertrophy have not been performed (Parsons et al., 2003; Gooch et al., 2004).

The underlying mechanism for how these two structurally similar isoforms display distinct phenotypes in vivo is unknown at this time, but may be due to differences in substrate recognition. In a report describing the enzymatic properties of bacterially expressed CaN holoenzymes, CaNβ was found to have the lowest KM values for all substrates tested when compared to CaNAα and CaNAγ (Kilka et al., 2009). However, due to similar differences in turnover number, CaNAα and CaNAβ had similar catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for the canonical substrates NFAT, PKA RII subunit and pNPP, with similar effects in cells on Elk-1 and NFAT-dependent gene expression (Kilka et al., 2009). As CaNAβ contains a unique proline-rich domain at its extreme N-terminus, it is thought that this domain contributed to the observed differences in substrate binding, and deletion of this domain significantly increased CaNAβ KM (and kcat) (Kilka et al., 2009). In a separate report, the bHLH transcription factor ATOH8 was shown to selectively bind CaNAβ, albeit through an unclear mechanism (Chen et al., 2016). Further studies are required to define whether there are in fact specific substrates of the different CaN isoforms in cells and how this specificity can be conferred. It is worth noting that in the original pivotal study in transgenic mice revealing the regulation of pathological hypertrophy by CaN, a truncated, constitutively active CaNAα fragment (residues 1–398) was expressed in the cardiac myocytes resulting in a severe cardiomyopathic phenotype (Molkentin et al., 1998). As CaNAβ is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Bueno et al., 2002), one might infer that the intrinsic catalytic activity of CaNAα and β-catalytic subunits is not functionally different. However, since this activated, truncated phosphatase does not exist in nature, how overexpression of activated CaNAα relates to the activation of normally compartmentalized CaNAβ must be interpreted with caution. In addition, the CaNAα transgenic likely includes dephosphorylation of some CaN-dependent substrates that may or may not be relevant to the pathophysiologic mechanisms of the common cardiovascular diseases.

CaN binding domains

CaN substrates and interacting proteins most commonly contain one of two binding motifs, PxIxIT or LxVP (Li et al., 2011; Penny & Gold, 2018), although other proteins can bind C-terminal domains of CaNA (e.g. L-type Ca2+ channels [Lca] and NCX1) and CaNB (e.g. ASK1) (Katanosaka et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Tandan et al., 2009). The PxIxIT motif was first identified in the CaN substrate NFAT1 (Aramburu et al., 1998). The PxIxIT motif binds the catalytic core of CaN on a site away from the catalytic cleft (Li et al., 2011). Several synthetic peptides have been developed to mimic this motif and have been shown to compete for CaN binding to NFAT without inhibition of phosphatase activity, thereby acting as a non-competitive CaN inhibitor (Garcia-Cozar et al., 1998; Aramburu et al., 1999). This motif displays a relatively low affinity for CaN, a feature that seems to function to prevent indiscriminate dephosphorylation of substrates. When the native NFAT PxIxIT sequence was modified to enhance CaN binding, a significant portion of dephosphorylated NFAT accumulated in the nucleus in resting cells (Aramburu et al., 1999). Conversely, a 10-fold decrease in affinity attenuated the ability of CaN to bind to and dephosphorylated NFAT (Aramburu et al., 1998).

The LxVP motif was first identified in NFAT4 and NFAT2, in which it is C-terminal to the PxIxIT motif, and has been found in other CaN-associated proteins such as the regulatory subunit alpha of PKA (Blumenthal et al., 1986; Liu et al., 2001; Martinez-Martinez et al., 2006). This motif binds to CaN at the interface of the A and B subunits, overlapping the site that can be occupied by immunophilin complexes (Grigoriu et al., 2013). As this site on CaN is only available under conditions of increase calcium, the LxVP site only interacts with activated CaN. Targeting of the CaN LxVP site in macrophages using competing peptides was recently shown to be anti-inflammatory (Escolano et al., 2014). Thus, the combinatorial use of multiple binding domains may allow for the fine tuning of substrate dephosphorylation under different physiological conditions. Alternatively, it may increase substrate specificity. Further studies on this domain are required to fully appreciate the role it plays in CaN signaling.

CaN Regulatory proteins

Several CaN regulatory proteins have been identified in cardiac tissues, including Calcineurin binding protein 1 (Cabin-1/Cain), Carabin, and Regulators of Calcineurin (RCAN1,2,3) (Sun et al., 1998; Kingsbury & Cunningham, 2000; Rothermel et al., 2000). While structurally diverse, these proteins have all been shown to bind and suppress CaN phosphatase activity. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of Cabin-1 blocked the induction of cardiac hypertrophy in mice (De Windt et al., 2001). Carabin mRNA and protein levels decline in pressure overload models of heart failure, suggesting a protective effect of this protein on decreasing CaN function (Bisserier et al., 2015). This is collaborated in mice, where cardiac overexpression of Carabin protects against cardiac hypertrophy (Bisserier et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016). Lastly, transgenic overexpression of RCAN1 in mouse cardiomyocytes is protective against many forms of cardiac disease (Rothermel et al., 2001). Taken together, these data demonstrate the importance of attenuating CaN activity as a protective mechanism against the development of heart disease.

The importance of CaN anchoring

One of the most debated questions surrounding second messenger signaling is how specific substrates can be singularly targeted. Multiple lines of evidence have found one of the key elements in defining specificity is the anchoring of phosphatases to scaffolding proteins, thereby localizing the enzyme to a discrete signaling complex. This is especially true for CaN, and many CaN scaffolds have been identified (Li et al., 2011; Parra & Rothermel, 2017). The importance of CaN anchoring in the heart for its functional activity was first investigated by overexpressing the CaN binding domain of Cain/Cabin-1 in vitro in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes, thereby displacing the phosphatase from endogenous PxIxIT domain proteins (Taigen et al., 2000; Rodriguez et al., 2005). Expression of this domain prevented both the phenylephrine- and angiotensin II-stimulated increase in myocyte size as well as gene expression, hallmarks of cardiac hypertrophy. When the anchoring disrupter and a similar peptide from AKAP5 (also known as AKAP79/150) were genetically expressed in mouse hearts, the response to catecholamine and pressure overload stimulation was significantly blunted (De Windt et al., 2001). Furthermore, the potential therapeutic benefit of using targeted CaN inhibition was suggested by adenoviral-mediated gene transfer into adult rat myocardium (De Windt et al., 2001). Hence, targeting CaN anchoring can be as efficient at attenuating cardiac hypertrophy as treatment with CaN immunophilin inhibitors, suggesting that cell-specific therapies could be effective and avoid the significant side effects of current systemic CaN-directed drugs. A listing of the anchoring proteins discussed here as well as the functional outcome of expressing the specific CaN anchoring disruptor peptide in the heart is found in Table 1.

Table 1. CaN binding motifs on scaffolds.

The defined CaN binding domains on each protein is provided as well as the type of motif, the effect on CaN activity, and the effect of the complex disrupting peptide on cardiac physiology.

| PROTEIN | CaN BINDING SEQUENCE | MOTIF | AFFECT ON CaN ACTIVITY | AFFECT OF PEPTIDE ON CARDIAC PHYSIOLOGY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cain | KFPPPEITVTPP | PxIxIT | Inhibitory | Blocks hypertrophy in RNV and transgenic mice |

| Carabin | RRKPQTRGKTFHGLLTRARGPPIEGPPRPQRGSTSFLDTRF | undefined | Inhibitory | Not performed |

| RCAN1 | HLAPPN, PSVVVH and QTRRPE | LxVP, PxIxIT and, TxxP | Inhibitory | Not performed |

| AKAP5 | LKIP, MEPIAIIITDTTE | LvXP, PxIxIT | Fine tunes, Inhibitory | Blocks hypertrophy in RNV and transgenic mice |

| Cypher/Zasp | Presently undefined | undefined | Inhibitory | Not performed |

| AKAP1 (AKAP121) | PCRRSESSGILPNTT* | undefined | unknown | Not performed |

| mAKAPβ | VYSLHNVELHEDSHTPFLKSSPKFTGTTQTVLTKSLSKDSSFSSTKSLPDLLGGSGLVR | undefined | No effect | Blocks hypertrophy in RNV |

The domain on AKAP1 is postulated based on comparison to the AKAP5 PxIXIT motif.

A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs)

A-kinase anchoring proteins are a family of scaffolds defined by their ability to bind the heterotetramer cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) (Carr et al., 1991; Kritzer et al., 2012). A conserved anchoring domain consisting of an 14–18 amino acid amphipathic helix on the scaffold binds to the NH2-terminus of the regulatory PKA dimer to confer AKAP binding to PKA (Carr et al., 1991). There are more than 50 known AKAP family members expressed in differing cell types and tissues (Kapiloff et al., 2014). These AKAPs each contain a discrete cellular distribution and act to co-localize the kinase with distinct substrate(s), providing specificity in cAMP signaling. Furthermore, AKAPs have been found to associate with additional signaling enzymes, such as phosphatases, phosphodiesterases and other kinases, thereby providing multifactorial regulation of phosphorylation events (Coghlan et al., 1995; Klauck et al., 1996; Dodge et al., 2001).

In heart, more than 30 AKAPs are expressed (Diviani et al., 2011). The importance of these scaffolds for cardiac function was first determined using peptides to globally disrupt PKA anchoring and demonstrated the diverse functions of AKAPs in the heart, including regulation of calcium dynamics, ion channels, and contractile function (Fink et al., 2001). For example, the short AKAP9 isoform Yotiao (also known as AKAP350/450) is known to localize PKA, PP1, and PDE4D3 to the α-subunit (KCNQ1) of the delayed rectifier K+ channel and mediates the enhancement of channel activity in response to β-adrenergic stimulation (Westphal et al., 1999; Marx et al., 2002; Terrenoire et al., 2009). Furthermore, many AKAPs have been implicated in the development of cardiac disease. These include mAKAPβ, AKAP-Lbc, AKAP5 and AKAP1 (also known as AKAP121) (Perez Lopez et al., 2013; Kritzer et al., 2014; Taglieri et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017; Schiattarella et al., 2018). Hence, modulation of AKAP expression, as well as disruption of AKAP scaffolding, is now being considered as an alternative to the standard pharmacological treatment of heart disease. This review will focus on the known AKAP/CaN complexes in the heart and describe the potential physiological consequences of the interaction on induction of cardiac disease (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic describing Calcineurin/AKAP interactions in the heart.

The composition of the AKAP complexes described are shown.

Regulation of PKA activity by CaN

PKA is a canonical substrate for CaN and association of CaN with AKAP complexes provides a potential mechanism for limiting PKA activity. Binding of cAMP to the regulatory subunit of PKA induces a conformational change, allowing for disassociation (or at least loose association (Smith et al., 2017)) of now active catalytic subunit and the subsequent phosphorylation of substrates. The type II regulatory subunit (RII) is a PKA substrate, and phosphorylation of Serine-96 decreases the affinity of RII for catalytic subunit, therefore prolonging catalytic activity (Rangel-Aldao et al., 1979; Granot et al., 1980). Interestingly, RII contains a LxVP CaN binding motif, and was one of the first identified CaN binding proteins (Blumenthal et al., 1986; Grigoriu et al., 2013). In fact, a peptide comprising the PKA RII Serine-96 site is used in the classical radiometric assay to measure CaN activity. Inclusion of CaN in AKAP complexes could enhance RII dephosphorylation, therefore facilitating re-formation of PKA holoenzyme and limiting PKA signaling duration. While this mechanism has not been fully tested, as phosphorylation of the RII site is decreased in human dilated cardiomyopathy, it may contribute to the diminished PKA signaling observed in the progression of this disease (Zakhary et al., 2000).

AKAP5

Historically, the relationship between AKAPs and CaN has been studied through the lens of AKAP5 (also known as AKAP 79/AKAP150). Yeast-2-hybrid analysis of the AKAP revealed it bound directly to the CaNA subunit, providing the first identification of AKAP/phosphatase interactions (Coghlan et al., 1995). In hippocampal neurons, AKAP5 anchors CaN close to the L-type calcium channel, thereby co-localizing the source of calcium stimulation with the phosphatase (Li et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2014). The sequence on AKAP5 “PIAIITD” is a putative PxIxIT motif. This domain binds CaN with a higher affinity than measured for NFAT binding. Manipulation of this binding domain impacts CaN anchoring and NFAT activation in cells, as mutation of this sequence to one that has a higher affinity for CaN prevented the movement of NFAT into the nucleus of hippocampal cells, suggesting the binding of CaN to scaffolds must be tightly controlled to prevent nondiscriminatory release and dephosphorylation of substrates (Li et al., 2012). The stochiometry of CaN/AKAP5 interactions is still in question. While fluorescent studies in hippocampal neurons as well as electron microscopy suggested a 1:1 ratio (Li et al., 2012; Nygren et al., 2017), gas phase chromatography of the complex implied that CaN binds the AKAP at a 2:1 ratio (Gold et al., 2011). An additional LxVP type CaN interaction was recently identified in AKAP5, and was shown to “fine-tune” the Ca2+ responsiveness of the bound phosphatase (Nygren et al., 2017).

In the heart, biochemical analysis has found that 0.2% of CaN is associated with AKAP5 localized to the sarcolemma of the myocyte, consistent with the concept that CaN is associated with multiple diverse “signalosomes” in individual cells (Nieves-Cintron et al., 2016). Importantly, the AKAP5/CaN signaling complex regulates NFATc3 translocation to the nucleus, and nuclear accumulation of NFATc3 is significantly decreased in myocytes expressing AKAP5 containing a deletion of its PxIxIT motif (Nieves-Cintron et al., 2016). Importantly, AKAP5-dependent NFATc3 translocation results in the reduced expression of voltage-gated potassium channels after myocardial infarction (Nieves-Cintron et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). However, NFAT translocation was not affected in AKAP5 knockout animals subjected to either pressure overload or agonist-induced hypertrophy, suggesting a specific role for AKAP5-associated CaN only in myocardial infarction (Li et al., 2017). The mechanism that underlies the disease-specific activation of this pool of CaN is unclear to date, but may be due to differences in calcium signaling in response to different pathological stimuli.

AKAP5 is also proposed to directly regulate excitation-contraction coupling due to its location in T-tubule-sarcoplasmic reticulum dyads where AKAP5 may regulate intracellular calcium stores. Immunoprecipitation studies have found the ryanodine receptor, SERCA2a and phospholamban all associate with AKAP5 (Li et al., 2017). Ablation of AKAP5 expression significantly decreased the phosphorylation of both ryanodine receptors and phospholamban by PKA, resulting in impaired calcium cycling and decreased myocyte contractility. Whether AKAP5-bound CaN contributes to the regulation of excitation-contraction coupling remains unclear.

AKAP5 has additional functions in the myocyte, including regulation of β-adrenergic signaling. AKAP5 has been shown to stimulate the trafficking of the β1-adrenergic receptor in cardiomyocytes, thereby affecting generation of cAMP and attenuating PKA activity. Co-immunoprecipitation studies have also demonstrated the association of AKAP5 with the β2-adrenergic receptor (Fraser et al., 2000). AKAP5 binding to the C-terminal tail of the receptor was found to mediate β2-adrenergic receptor PKA phosphorylation, a key step for receptor-mediated switching of G-protein activation and receptor internalization (Fraser et al., 2000; Gardner et al., 2006). Subsequent studies extended this finding to the β1-adrenergic receptor, and rat neonatal myocytes lacking AKAP5 demonstrated reduced internalization of the β1-receptor after agonist stimulation (Gardner et al., 2006). In contrast to other studies, this group found an increase in CaN activity in AKAP5 knockout mice, demonstrated by an increase in NFAT luciferase activity (Li et al., 2013b). Treatment with the β-adrenergic antagonist Carvedilol normalized the activity of the phosphatase, suggesting the mechanism may be due to enhanced receptor signaling (Li et al., 2014).

Cypher/Zasp

The AKAP Cypher/Zasp is a PDZ-LIM domain family member that is localized to the Z-line through direct protein interactions and contributes to the structural integrity of the sarcomere (Lin et al., 2013). The cypher gene can be alternatively spiced to produce the PDZ-motif protein Zasp. Mutations of Zasp are associated with cardiomyopathies in humans (Lin et al., 2013). Cypher/Zasp was found to directly bind PKA and the L-type calcium channel in cardiac myocytes, suggesting the interaction mediated the PKA phosphorylation of the channel (Lin et al., 2013). In mice lacking the expression of this protein, L-type calcium channel currents were reduced after β-adrenergic stimulation (Yu et al., 2018). Cypher/Zasp directly binds CaN, although the mechanism for binding as well as the function of this association has not been investigated (Lin et al., 2013).

AKAP1

AKAP121 and the shorter AKAP1 isoform AKAP84 are localized to the outer membrane of mitochondria in various cell types, including cardiac myocytes (Merrill & Strack, 2014). Knockdown of AKAP1 in rat neonatal ventricular myocytes displayed a pronounced increase in cellular hypertrophy in response to β-adrenergic stimulation, while AKAP121 overexpression attenuated the hypertrophic phenotype (Abrenica et al., 2009b). This was confirmed in two in vivo models of cardiac hypertrophy: in rats subjected to transverse aortic constriction after treated with peptides to displace the localization of the AKAP from the mitochondria and in AKAP1 knockout mice subjected to pressure overload (Perrino et al., 2010; Schiattarella et al., 2018). In adult cardiomyocytes, the disruption of localized AKAP1 is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and production of reactive oxygen species. It is not fully understood how AKAP1 regulates cardiac hypertrophy, but may be due to dysregulation of NFAT. Decreased expression of AKAP121 correlated with an increase in dephosphorylated and nuclear accumulation of NFATc3 (Abrenica et al., 2009b). The mechanism that underlies NFAT regulation is unknown at present, though it is hypothesized to be due to CaN association with AKAP1. The phosphatase was found in AKAP1 immunoprecipitates, although, despite sequence similarity to AKAP5, the nature of the interaction is not clear (Abrenica et al., 2009b). Importantly, AKAP1 binding to CaN is suggested to limit CaN function by sequestering the phosphatase to a discrete domain where phosphatase activity is inhibited.

The interplay between CaN and PKA may also regulate mitochondrial function. Studies have found AKAP1 orchestrates a complex consisting of PKA, CaN and the dynamin related protein 1 (DRP1). The balance of mitochondrial fusion and fission is required for proper cardiomyocyte metabolism, and DRP1, a large GTPase responsible for the final stage in mitochondrial fission, is a major target for regulation of this process (Merrill & Strack, 2014). DRP1 contains a LxVP motif and binds to active CaN, suggesting this protein may contribute to the association of the phosphatase with AKAP1 signalosomes (Slupe et al., 2013). CaN dephosphorylates DRP1 leading to its activation, and therefore fission (Cribbs & Strack, 2007). Conversely, PKA will phosphorylate DRP1 promoting fusion (Cribbs & Strack, 2007). Several reports show that mitochondrial fission is required for hypertrophy in both neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes (Givvimani et al., 2012; Pennanen et al., 2014). In neonatal cardiomyocytes, treatment with norepinephrine increases cytoplasmic calcium followed by activation of CaN and translocation of DRP1 to the mitochondria (Pennanen et al., 2014). The role of AKAP1 for this process has not been investigated to date. However, ablation of AKAP1 in mice and the resulting mitochondrial abnormalities impacted infarct size, cardiac remodeling and mortality after myocardial infarction, suggesting that the AKAP1 complex creates a locus for regulation of mitochondrial function that affects the progression of cardiac disease (Givvimani et al., 2012). While the relationship between mitochondrial dynamics and cardiac disease is still poorly understood, these emerging data provide encouraging new paths for discovery.

mAKAPβ (AKAP6)

Two decades of research have confirmed mAKAPβ to be a master organizer of pathological cardiac remodeling (Passariello et al., 2015). This AKAP was originally discovered during a cDNA library screen to identify new PKA binding proteins (McCartney et al., 1995). The larger 250kDa isoform of the scaffold, mAKAPα, is primarily found in neurons, while the alternatively-spliced mAKAPβ isoform lacking the first 244 aa residues of mAKAPα is expressed in striated mycoytes (Michel et al., 2005). mAKAP is localized to the nuclear envelope via direct binding to nesprin-1α involving heterodimerization of spectrin-like repeat moieties in the two proteins (Pare et al., 2005b). Both cellular knockdown studies of mAKAPβ and genetic ablation of mAKAPβ in mouse cardiomyocytes have demonstrated that mAKAPβ expression is required for the induction of cardiac hypertrophy (Pare et al., 2005a; Kritzer et al., 2014). Notably, mAKAPβ knockout inhibited the development of pathological remodeling and heart failure during long term pressure overload, conferring a survival benefit (Kritzer et al., 2014).

The mechanisms utilized by the mAKAP to promote pathological cardiac remodeling are currently being investigated, but include the ability of mAKAPβ to orchestrate the nuclear function of several second messenger signaling pathways, including calcium, cAMP, hypoxia, and mitogen activated protein kinase signaling (Passariello et al., 2015). mAKAPβ remains one of the best examples of how AKAPs integrate multiple signaling pathways to modulate stress-related gene expression in the cardiomyocyte. Of particular interest is the recruitment of CaNAβ to mAKAPβ signalosomes. While overexpression studies found that both CaNAα and CaNAβ could both bind mAKAPβ, only CaNAβ has been detected in mAKAPβ complexes isolated from heart tissue (Li et al., 2010). Importantly, adrenergic stimulation of rat neonatal ventricular myocytes induced the movement of CaNAβ to the mAKAPβ complex, suggesting a regulated association that is dependent on the activity status of the phosphatase (Li et al., 2010). Furthermore, mAKAPβ binding did not inhibit CaN activity in in vitro assays (Li et al., 2010). This is in contrast to AKAP5, where in vitro assays found peptides mimicking its PxIxIT motif attenuated CaN activity. Additionally, AKAP1 is also suggested to also inhibit CaN activity. (Dell’Acqua et al., 2002; Abrenica et al., 2009a; Li et al., 2010). How mAKAPβ binds CaNAβ is unclear, as no consensus motifs are evident within the minimally defined CaNAβ binding domain on mAKAP (residues 1286–1345) (Li et al., 2010).

Although the exact nature of the activation and recruitment of CaNAβ to mAKAPβ remains unknown, it may involve the associated ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2). While RyR2 is thought of only in regards to its role in excitation-contraction coupling, several investigators have found a small fraction of RyR2 is found at perinuclear dyads (Franzini-Armstrong & Protasi, 1997; Kapiloff et al., 2001; Ljubojevic et al., 2014). This nuclear pool of RyR2 can co-immunoprecipitate with mAKAPβ in both cardiac and skeletal muscle (Kapiloff et al., 2001; Ruehr et al., 2003). Importantly, mAKAPβ-bound PKA is responsible for the increased phosphorylation of RyR2 in the complex after β-adrenergic stimulation, where it presumably promotes an increase in calcium release in the vicinity of the mAKAP signalosome (Kapiloff et al., 2001). Hence, it is plausible that local pools of perinuclear calcium released by mAKAPβ-bound RyR2 provide the impetus for CaNAβ activation and recruitment.

mAKAPβ-dependent compartmentation may extend to a nuclear localized β-adrenergic receptor. Both β1-AR and β3-AR are found on the nucleus in adult cardiac myocytes and β1-AR has also be localized to Golgi membranes, which are in close proximity to the nuclear envelope (Boivin et al., 2006; Boivin et al., 2008). Previous work found that PLCε that is bound to mAKAPβ is responsible for the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PIP4) at the golgi under β-adrenergic stimulation concurrent with inhibition of PDE3 (Zhang et al., 2011; Nash et al., 2018b). Recently, the role of internal β-adrenergic receptors on this PIP4 hydrolysis was investigated. Importantly, only cell permeable beta blockers could attenuate the effects of dobutamine, while cell impermeable blockers such as Sotolol could not, suggesting mAKAPβ is complexed with an internal β-adrenergic receptor (Nash et al., 2018a). This receptor may be responsible for not only the mAKAPβ-bound PKA activation, but the norephenephrine-induced localization of CaN to the complex (Li et al., 2010). More studies are required to investigate this possibility.

Experiments in myocytes using a full-length mAKAPβ mutant incapable of binding CaNAβ as well as disrupting peptides to compete CaNAβ binding to mAKAPβ show the necessity of their association for the induction of hypertrophy in response to adrenergic signaling (Li et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013a). Importantly, mAKAPβ also recruits two relevant CaNAβ-substrates, the transcription factors NFATc3 and MEF2D. Both of these transcription factors were increased in phosphorylation in mAKAP knockout hearts following pressure overload, suggesting mAKAPβ expression is required to direct CaN activity to these substrates (Li et al., 2010; Vargas et al., 2012; Kritzer et al., 2014). In neonatal myocytes, NFAT dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation depends on mAKAPβ expression and CaN localization to the scaffold (Li et al., 2010). In a like manner, the association of CaNAβ and MEF2D is dependent upon mAKAPβ-expression (Li et al., 2013a). Accordingly, competitive disruption of CaNAβ/mAKAPβ binding in C2C12 cells successfully halted the stimulated increase in MEF2D transcription required for myogenic differentiation. These encouraging results demonstrate that targeting the mAKAPβ/CaNAβ interaction may provide an important avenue for therapeutic treatment of cardiac hypertrophy.

Perspective

The role of CaN in regulating pathological cardiac hypertrophy is now well-established. However, early enthusiasm for targeting CaN in cardiovascular disease was immediately tempered by the recognition that currently prescribed CaN inhibitors are immunosuppressant, including the immunophilins cyclosporin A and FK506 that enabled the field of tissue transplantation (Martinez-Martinez & Redondo, 2004). As the attenuation of pathological hypertrophy and the prevention of heart failure will presumably require long term treatment, any CaN-directed therapies will need to have limited immunosuppression. The basic science research described above suggests that targeting of specific CaN signaling complexes in the heart may be a pathway to success. One approach might be the use of CaN anchoring disruptor peptides to inhibit the association of CaN with signalosomes in the heart controlling remodeling. While these peptides could be synthetic chemically-modified peptides administered systemically, an alternative strategy would be to use adeno-associated virus gene transfer to express CaN-directed peptides exclusively in cardiac myocytes (Hajjar & Ishikawa, 2017). We suggest using the defined binding domain on mAKAPβ to further investigate this possibility. mAKAPβ is the only AKAP to date that apparently binds CaNAβ selectively in the heart, the CaNA isoform contributing to the induction of pathological cardiac remodeling (Bueno et al., 2002). Targeting of mAKAPβ signalosomes is apparently well-tolerated and effective, as conditional gene deletion of the scaffold attenuated the development of heart failure in response to pressure overload (Kritzer et al., 2014). Furthermore, expression of this peptide in RNV did not inhibit CaN activity, but successfully attenuated β-AR-induced hypertrophy, mimicking the effect of scaffold deletion in the mouse (Li et al., 2013a).

However, many potential problems will need to be addressed before targeting CaN complexes for therapeutic benefit can be achieved. As CaNAβ is also known to contribute to the regulation of the immune system (Manicassamy et al., 2008), cell type-specific therapies are critical to avoid immunosuppression even if CaNAβ-specific binding peptides are utilized. Another major hurdle will be that the CaNAβ knock-out impaired myocyte survival in a mouse model of ischemic heart disease (Bueno et al., 2004). As most patients with pathological hypertrophy are also at risk for myocardial infarction, adoption of a drug that might worsen outcome after infarction would be tenuous as best. However, if a signalosome can be identified that can distinguish between CaNAβ pro-survival and pro-remodeling pathways, it may be possible that to develop an acceptable calcineurin-directed cardiac therapy.

As CaNAβ binds the different aforementioned scaffold proteins through different molecular interfaces (see Table 1), it may be possible to identify small molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interaction with appropriate selectively as an alternative mechanism to disrupt CaN/AKAP interactions in vivo. This would require a detailed investigation into each structure/function relationship in order to develop specific molecules to affect individual complexes. Furthermore, it may be advantageous to focus on the downstream targets of CaN in each complex in order to provide alternative approaches to inhibiting CaN signaling other than those directed at the phosphatase itself. As CaN scaffolds tend to bind relevant CaN substrates, disruption of the substrate-scaffold interface may be an alternative approach. These ideas all reinforce the concept that a comprehensive understanding of the structure and function of intracellular signaling pathways are likely to yield not only great knowledge, but also new insights into how these pathways may be manipulated for the public good. As heart failure will continue to increase in prevalence and cost in coming years (Benjamin et al., 2018), further research into CaN signaling will remain a compelling pursuit.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded, in whole or in part, and National Institutes of Health Grants HL126825 (K.D.K. and M.S.K.), EY026766 and HL126950 (M.S.K) and American Heart Association Predoctoral Grant 18PRE34030209 to MG.

Author Profiles

Kimberly Dodge-Kafka, PhD, has been at the University of Connecticut Health Center since 2003, where she is currently and Associate Professor of Cell Biology. Her research combines, biochemical, cellular and physiological approaches to investigate the role of scaffolding proteins in modulating the signaling pathways involved in the induction of cardiac disease.

Michael S. Kapiloff, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor at Stanford University where his laboratory studies the basic molecular mechanisms underlying the response of the cardiac myocyte and retinal ganglion cell to pathological stress and how these concepts may be translated into new therapies. He is a Fellow of the American Physiological Society and American Heart Association and a member of the American Society for Clinical Investigation.

References

- Abrenica B, AlShaaban M & Czubryt MP. (2009a). The A-kinase anchor protein AKAP121 is a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46, 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrenica B, AlShaaban M & Czubryt MP. (2009b). The A-kinase anchor protein AKAP121 is a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46, 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu J, Garcia-Cozar F, Raghavan A, Okamura H, Rao A & Hogan PG. (1998). Selective inhibition of NFAT activation by a peptide spanning the calcineurin targeting site of NFAT. Mol Cell 1, 627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu J, Yaffe MB, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Cantley LC, Hogan PG & Rao A. (1999). Affinity-driven peptide selection of an NFAT inhibitor more selective than cyclosporin A. Science 285, 2129–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C & Stroke Statistics S. (2018). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 137, e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisserier M, Berthouze-Duquesnes M, Breckler M, Tortosa F, Fazal L, de Regibus A, Laurent AC, Varin A, Lucas A, Branchereau M, Marck P, Schickel JN, Delomenie C, Cazorla O, Soulas-Sprauel P, Crozatier B, Morel E, Heymes C & Lezoualc’h F. (2015). Carabin protects against cardiac hypertrophy by blocking calcineurin, Ras, and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signaling. Circulation 131, 390–400; discussion 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DK, Takio K, Hansen RS & Krebs EG. (1986). Dephosphorylation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit (type II) by calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase. Determinants of substrate specificity. J Biol Chem 261, 8140–8145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin B, Lavoie C, Vaniotis G, Baragli A, Villeneuve LR, Ethier N, Trieu P, Allen BG & Hebert TE. (2006). Functional beta-adrenergic receptor signalling on nuclear membranes in adult rat and mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 71, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin B, Vaniotis G, Allen BG & Hebert TE. (2008). G protein-coupled receptors in and on the cell nucleus: a new signaling paradigm? J Recept Signal Transduct Res 28, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno OF, Lips DJ, Kaiser RA, Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Glascock BJ, Klevitsky R, Hewett TE, Kimball TR, Aronow BJ, Doevendans PA & Molkentin JD. (2004). Calcineurin Abeta gene targeting predisposes the myocardium to acute ischemia-induced apoptosis and dysfunction. Circ Res 94, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno OF, Wilkins BJ, Tymitz KM, Glascock BJ, Kimball TF, Lorenz JN & Molkentin JD. (2002). Impaired cardiac hypertrophic response in Calcineurin Abeta -deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 4586–4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DW, Stofko-Hahn RE, Fraser ID, Bishop SM, Acott TS, Brennan RG & Scott JD. (1991). Interaction of the regulatory subunit (RII) of cAMP-dependent protein kinase with RII-anchoring proteins occurs through an amphipathic helix binding motif. J Biol Chem 266, 14188–14192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan VS, Wong C & Ohashi PS. (2002). Calcineurin Aalpha plays an exclusive role in TCR signaling in mature but not in immature T cells. Eur J Immunol 32, 1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Balakrishnan-Renuka A, Hagemann N, Theiss C, Chankiewitz V, Chen J, Pu Q, Erdmann KS & Brand-Saberi B. (2016). A novel interaction between ATOH8 and PPP3CB. Histochem Cell Biol 145, 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan VM, Perrino BA, Howard M, Langeberg LK, Hicks JB, Gallatin WM & Scott JD. (1995). Association of protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 2B with a common anchoring protein. Science 267, 108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs JT & Strack S. (2007). Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep 8, 939–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Windt LJ, Lim HW, Bueno OF, Liang Q, Delling U, Braz JC, Glascock BJ, Kimball TF, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ & Molkentin JD. (2001). Targeted inhibition of calcineurin attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 3322–3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Acqua ML, Dodge KL, Tavalin SJ & Scott JD. (2002). Mapping the protein phosphatase-2B anchoring site on AKAP79. Binding and inhibition of phosphatase activity are mediated by residues 315–360. J Biol Chem 277, 48796–48802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diviani D, Dodge-Kafka KL, Li J & Kapiloff MS. (2011). A-kinase anchoring proteins: scaffolding proteins in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301, H1742–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KL, Khouangsathiene S, Kapiloff MS, Mouton R, Hill EV, Houslay MD, Langeberg LK & Scott JD. (2001). mAKAP assembles a protein kinase A/PDE4 phosphodiesterase cAMP signaling module. EMBO J 20, 1921–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escolano A, Martinez-Martinez S, Alfranca A, Urso K, Izquierdo HM, Delgado M, Martin F, Sabio G, Sancho D, Gomez-del Arco P & Redondo JM. (2014). Specific calcineurin targeting in macrophages confers resistance to inflammation via MKP-1 and p38. EMBO J 33, 1117–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink MA, Zakhary DR, Mackey JA, Desnoyer RW, Apperson-Hansen C, Damron DS & Bond M. (2001). AKAP-mediated targeting of protein kinase a regulates contractility in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 88, 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C & Protasi F. (1997). Ryanodine receptors of striated muscles: a complex channel capable of multiple interactions. Physiol Rev 77, 699–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser ID, Cong M, Kim J, Rollins EN, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ & Scott JD. (2000). Assembly of an A kinase-anchoring protein-beta(2)-adrenergic receptor complex facilitates receptor phosphorylation and signaling. Curr Biol 10, 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher SC, Gao ZH, Li S, Dyer RB, Trewhella J & Klee CB. (2001). There is communication between all four Ca(2+)-bindings sites of calcineurin B. Biochemistry 40, 12094–12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cozar FJ, Okamura H, Aramburu JF, Shaw KT, Pelletier L, Showalter R, Villafranca E & Rao A. (1998). Two-site interaction of nuclear factor of activated T cells with activated calcineurin. J Biol Chem 273, 23877–23883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner LA, Tavalin SJ, Goehring AS, Scott JD & Bahouth SW. (2006). AKAP79-mediated targeting of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase to the beta1-adrenergic receptor promotes recycling and functional resensitization of the receptor. J Biol Chem 281, 33537–33553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givvimani S, Munjal C, Tyagi N, Sen U, Metreveli N & Tyagi SC. (2012). Mitochondrial division/mitophagy inhibitor (Mdivi) ameliorates pressure overload induced heart failure. PLoS One 7, e32388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MG, Stengel F, Nygren PJ, Weisbrod CR, Bruce JE, Robinson CV, Barford D & Scott JD. (2011). Architecture and dynamics of an A-kinase anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) signaling complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 6426–6431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooch JL. (2006). An emerging role for calcineurin Aalpha in the development and function of the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290, F769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooch JL, Toro JJ, Guler RL & Barnes JL. (2004). Calcineurin A-alpha but not A-beta is required for normal kidney development and function. Am J Pathol 165, 1755–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot J, Mildvan AS, Hiyama K, Kondo H & Kaiser ET. (1980). Magnetic resonance studies of the effect of the regulatory subunit on metal and substrate binding to the catalytic subunit of bovine heart protein kinase. J Biol Chem 255, 4569–4573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriu S, Bond R, Cossio P, Chen JA, Ly N, Hummer G, Page R, Cyert MS & Peti W. (2013). The molecular mechanism of substrate engagement and immunosuppressant inhibition of calcineurin. PLoS biology 11, e1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar RJ & Ishikawa K. (2017). Introducing Genes to the Heart: All About Delivery. Circ Res 120, 33–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakalis LT, Kennedy M, Sikkink R, Rusnak F & Armitage IM. (1995). Characterization of the calcium-binding sites of calcineurin B. FEBS Lett 362, 55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiloff MS, Jackson N & Airhart N. (2001). mAKAP and the ryanodine receptor are part of a multi-component signaling complex on the cardiomyocyte nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci 114, 3167–3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiloff MS, Rigatti M & Dodge-Kafka KL. (2014). Architectural and functional roles of A kinase-anchoring proteins in cAMP microdomains. J Gen Physiol 143, 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katanosaka Y, Iwata Y, Kobayashi Y, Shibasaki F, Wakabayashi S & Shigekawa M. (2005). Calcineurin inhibits Na+/Ca2+ exchange in phenylephrine-treated hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 280, 5764–5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatlani T, Pradhan S, Da Q, Gushiken FC, Bergeron AL, Langlois KW, Molkentin JD, Rumbaut RE & Vijayan KV. (2014). The beta isoform of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2B restrains platelet function by suppressing outside-in alphaII b beta3 integrin signaling. J Thromb Haemost 12, 2089–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilka S, Erdmann F, Migdoll A, Fischer G & Weiwad M. (2009). The proline-rich N-terminal sequence of calcineurin Abeta determines substrate binding. Biochemistry 48, 1900–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury TJ & Cunningham KW. (2000). A conserved family of calcineurin regulators. Genes Dev 14, 1595–1604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauck TM, Faux MC, Labudda K, Langeberg LK, Jaken S & Scott JD. (1996). Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science 271, 1589–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzer MD, Li J, Dodge-Kafka K & Kapiloff MS. (2012). AKAPs: the architectural underpinnings of local cAMP signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52, 351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzer MD, Li J, Passariello CL, Gayanilo M, Thakur H, Dayan J, Dodge-Kafka K & Kapiloff MS. (2014). The scaffold protein muscle A-kinase anchoring protein beta orchestrates cardiac myocyte hypertrophic signaling required for the development of heart failure. Circulation Heart failure 7, 663–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Pink MD, Murphy JG, Stein A, Dell’Acqua ML & Hogan PG. (2012). Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19, 337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rao A & Hogan PG. (2011). Interaction of calcineurin with substrates and targeting proteins. Trends Cell Biol 21, 91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Negro A, Lopez J, Bauman AL, Henson E, Dodge-Kafka K & Kapiloff MS. (2010). The mAKAPbeta scaffold regulates cardiac myocyte hypertrophy via recruitment of activated calcineurin. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48, 387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Vargas MA, Kapiloff MS & Dodge-Kafka KL. (2013a). Regulation of MEF2 transcriptional activity by calcineurin/mAKAP complexes. Exp Cell Res 319, 447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li J, Drum BM, Chen Y, Yin H, Guo X, Luckey SW, Gilbert ML, McKnight GS, Scott JD, Santana LF & Liu Q. (2017). Loss of AKAP150 promotes pathological remodelling and heart failure propensity by disrupting calcium cycling and contractile reserve. Cardiovasc Res 113, 147–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Wang J, Ma L, Lu C, Wang J, Wu JW & Wang ZX. (2016). Cooperative autoinhibition and multi-level activation mechanisms of calcineurin. Cell Res 26, 336–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Matta SM, Sullivan RD & Bahouth SW. (2014). Carvedilol reverses cardiac insufficiency in AKAP5 knockout mice by normalizing the activities of calcineurin and CaMKII. Cardiovasc Res 104, 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Nooh MM & Bahouth SW. (2013b). Role of AKAP79/150 protein in beta1-adrenergic receptor trafficking and signaling in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 288, 33797–33812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Guo X, Lange S, Liu J, Ouyang K, Yin X, Jiang L, Cai Y, Mu Y, Sheikh F, Ye S, Chen J, Ke Y & Cheng H. (2013). Cypher/ZASP is a novel A-kinase anchoring protein. J Biol Chem 288, 29403–29413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Arai K & Arai N. (2001). Inhibition of NFATx activation by an oligopeptide: disrupting the interaction of NFATx with calcineurin. J Immunol 167, 2677–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wilkins BJ, Lee YJ, Ichijo H & Molkentin JD. (2006). Direct interaction and reciprocal regulation between ASK1 and calcineurin-NFAT control cardiomyocyte death and growth. Mol Cell Biol 26, 3785–3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubojevic S, Radulovic S, Leitinger G, Sedej S, Sacherer M, Holzer M, Winkler C, Pritz E, Mittler T, Schmidt A, Sereinigg M, Wakula P, Zissimopoulos S, Bisping E, Post H, Marsche G, Bossuyt J, Bers DM, Kockskamper J & Pieske B. (2014). Early remodeling of perinuclear Ca2+ stores and nucleoplasmic Ca2+ signaling during the development of hypertrophy and heart failure. Circulation 130, 244–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicassamy S, Gupta S, Huang Z, Molkentin JD, Shang W & Sun Z. (2008). Requirement of calcineurin a beta for the survival of naive T cells. J Immunol 180, 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martinez S & Redondo JM. (2004). Inhibitors of the calcineurin/NFAT pathway. Current medicinal chemistry 11, 997–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martinez S, Rodriguez A, Lopez-Maderuelo MD, Ortega-Perez I, Vazquez J & Redondo JM. (2006). Blockade of NFAT activation by the second calcineurin binding site. J Biol Chem 281, 6227–6235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SO, Kurokawa J, Reiken S, Motoike H, D’Armiento J, Marks AR & Kass RS. (2002). Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science 295, 496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney S, Little BM, Langeberg LK & Scott JD. (1995). Cloning and characterization of A-kinase anchor protein 100 (AKAP100). A protein that targets A-kinase to the sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 270, 9327–9333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill RA & Strack S. (2014). Mitochondria: a kinase anchoring protein 1, a signaling platform for mitochondrial form and function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 48, 92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel JJ, Townley IK, Dodge-Kafka KL, Zhang F, Kapiloff MS & Scott JD. (2005). Spatial restriction of PDK1 activation cascades by anchoring to mAKAPalpha. Mol Cell 20, 661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Lu JR, Antos CL, Markham B, Richardson J, Robbins J, Grant SR & Olson EN. (1998). A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 93, 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muili KA, Ahmad M, Orabi AI, Mahmood SM, Shah AU, Molkentin JD & Husain SZ. (2012). Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of calcineurin protects against carbachol-induced pathological zymogen activation and acinar cell injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302, G898–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Sanderson JL, Gorski JA, Scott JD, Catterall WA, Sather WA & Dell’Acqua ML. (2014). AKAP-anchored PKA maintains neuronal L-type calcium channel activity and NFAT transcriptional signaling. Cell reports 7, 1577–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash C, Wenhui W & Smrcka A. (2018a). An Internal Pool of beta-Adrenergic Receptors Activates PLC-mediated PI4P Hydrolysis in Cardiac Myocytes. In Experimental Biology. San Diego, California. [Google Scholar]

- Nash CA, Brown LM, Malik S, Cheng X & Smrcka AV. (2018b). Compartmentalized cyclic nucleotides have opposing effects on regulation of hypertrophic phospholipase Cepsilon signaling in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 121, 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves-Cintron M, Hirenallur-Shanthappa D, Nygren PJ, Hinke SA, Dell’Acqua ML, Langeberg LK, Navedo M, Santana LF & Scott JD. (2016). AKAP150 participates in calcineurin/NFAT activation during the down-regulation of voltage-gated K(+) currents in ventricular myocytes following myocardial infarction. Cell Signal 28, 733–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren PJ, Mehta S, Schweppe DK, Langeberg LK, Whiting JL, Weisbrod CR, Bruce JE, Zhang J, Veesler D & Scott JD. (2017). Intrinsic disorder within AKAP79 fine-tunes anchored phosphatase activity toward substrates and drug sensitivity. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T, Dai YS & Molkentin JD. (2005). Regulation of calcineurin through transcriptional induction of the calcineurin A beta promoter in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 25, 6649–6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare GC, Bauman AL, McHenry M, Michel JJ, Dodge-Kafka KL & Kapiloff MS. (2005a). The mAKAP complex participates in the induction of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy by adrenergic receptor signaling. J Cell Sci 118, 5637–5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare GC, Easlick JL, Mislow JM, McNally EM & Kapiloff MS. (2005b). Nesprin-1alpha contributes to the targeting of mAKAP to the cardiac myocyte nuclear envelope. Exp Cell Res 303, 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra V & Rothermel BA. (2017). Calcineurin signaling in the heart: The importance of time and place. J Mol Cell Cardiol 103, 121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons SA, Wilkins BJ, Bueno OF & Molkentin JD. (2003). Altered skeletal muscle phenotypes in calcineurin Aalpha and Abeta gene-targeted mice. Mol Cell Biol 23, 4331–4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passariello CL, Li J, Dodge-Kafka K & Kapiloff MS. (2015). mAKAP-a master scaffold for cardiac remodeling. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 65, 218–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena JA, Losi-Sasaki JL & Gooch JL. (2010). Loss of calcineurin Aalpha alters keratinocyte survival and differentiation. J Invest Dermatol 130, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennanen C, Parra V, Lopez-Crisosto C, Morales PE, Del Campo A, Gutierrez T, Rivera-Mejias P, Kuzmicic J, Chiong M, Zorzano A, Rothermel BA & Lavandero S. (2014). Mitochondrial fission is required for cardiomyocyte hypertrophy mediated by a Ca2+-calcineurin signaling pathway. J Cell Sci 127, 2659–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny CJ & Gold MG. (2018). Mechanisms for localising calcineurin and CaMKII in dendritic spines. Cell Signal 49, 46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Lopez I, Cariolato L, Maric D, Gillet L, Abriel H & Diviani D. (2013). A-kinase anchoring protein Lbc coordinates a p38 activating signaling complex controlling compensatory cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biol 33, 2903–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino C, Feliciello A, Schiattarella GG, Esposito G, Guerriero R, Zaccaro L, Del Gatto A, Saviano M, Garbi C, Carangi R, Di Lorenzo E, Donato G, Indolfi C, Avvedimento VE & Chiariello M. (2010). AKAP121 downregulation impairs protective cAMP signals, promotes mitochondrial dysfunction, and increases oxidative stress. Cardiovasc Res 88, 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Aldao R, Kupiec JW & Rosen OM. (1979). Resolution of the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated cAMP-binding proteins of bovine cardiac muscle by affinity labeling and two-dimensional electrophoresis. J Biol Chem 254, 2499–2508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RN, Knotts TL, Roberts BR, Molkentin JD, Price SR & Gooch JL. (2011). Calcineurin A-beta is required for hypertrophy but not matrix expansion in the diabetic kidney. J Cell Mol Med 15, 414–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Martinez-Martinez S, Lopez-Maderuelo MD, Ortega-Perez I & Redondo JM. (2005). The linker region joining the catalytic and the regulatory domains of CnA is essential for binding to NFAT. J Biol Chem 280, 9980–9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel B, Vega RB, Yang J, Wu H, Bassel-Duby R & Williams RS. (2000). A protein encoded within the Down syndrome critical region is enriched in striated muscles and inhibits calcineurin signaling. J Biol Chem 275, 8719–8725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel BA, McKinsey TA, Vega RB, Nicol RL, Mammen P, Yang J, Antos CL, Shelton JM, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN & Williams RS. (2001). Myocyte-enriched calcineurin-interacting protein, MCIP1, inhibits cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 3328–3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehr ML, Russell MA, Ferguson DG, Bhat M, Ma J, Damron DS, Scott JD & Bond M. (2003). Targeting of protein kinase A by muscle A kinase-anchoring protein (mAKAP) regulates phosphorylation and function of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 278, 24831–24836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiattarella GG, Boccella N, Paolillo R, Cattaneo F, Trimarco V, Franzone A, D’Apice S, Giugliano G, Rinaldi L, Borzacchiello D, Gentile A, Lombardi A, Feliciello A, Esposito G & Perrino C. (2018). Loss of Akap1 Exacerbates Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. Front Physiol 9, 558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slupe AM, Merrill RA, Flippo KH, Lobas MA, Houtman JC & Strack S. (2013). A calcineurin docking motif (LXVP) in dynamin-related protein 1 contributes to mitochondrial fragmentation and ischemic neuronal injury. J Biol Chem 288, 12353–12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FD, Esseltine JL, Nygren PJ, Veesler D, Byrne DP, Vonderach M, Strashnov I, Eyers CE, Eyers PA, Langeberg LK & Scott JD. (2017). Local protein kinase A action proceeds through intact holoenzymes. Science 356, 1288–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Youn HD, Loh C, Stolow M, He W & Liu JO. (1998). Cabin 1, a negative regulator for calcineurin signaling in T lymphocytes. Immunity 8, 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglieri DM, Johnson KR, Burmeister BT, Monasky MM, Spindler MJ, DeSantiago J, Banach K, Conklin BR & Carnegie GK. (2014). The C-terminus of the long AKAP13 isoform (AKAP-Lbc) is critical for development of compensatory cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 66, 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taigen T, De Windt LJ, Lim HW & Molkentin JD. (2000). Targeted inhibition of calcineurin prevents agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 1196–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandan S, Wang Y, Wang TT, Jiang N, Hall DD, Hell JW, Luo X, Rothermel BA & Hill JA. (2009). Physical and functional interaction between calcineurin and the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. Circ Res 105, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrenoire C, Houslay MD, Baillie GS & Kass RS. (2009). The cardiac IKs potassium channel macromolecular complex includes the phosphodiesterase PDE4D3. J Biol Chem 284, 9140–9146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas MA, Tirnauer JS, Glidden N, Kapiloff MS & Dodge-Kafka KL. (2012). Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) tethering to muscle selective A-kinase anchoring protein (mAKAP) is necessary for myogenic differentiation. Cell Signal 24, 1496–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal RS, Tavalin SJ, Lin JW, Alto NM, Fraser ID, Langeberg LK, Sheng M & Scott JD. (1999). Regulation of NMDA receptors by an associated phosphatase-kinase signaling complex. Science 285, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, Jones F, Kimball TR & Molkentin JD. (2004). Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 94, 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BJ & Molkentin JD. (2004). Calcium-calcineurin signaling in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322, 1178–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Peisley A, Graef IA & Crabtree GR. (2007). NFAT signaling and the invention of vertebrates. Trends Cell Biol 17, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Yuan C, Westenbroek RE & Catterall WA. (2018). The AKAP Cypher/Zasp contributes to beta-adrenergic/PKA stimulation of cardiac CaV1.2 calcium channels. J Gen Physiol 150, 883–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakhary DR, Moravec CS & Bond M. (2000). Regulation of PKA binding to AKAPs in the heart: alterations in human heart failure. Circulation 101, 1459–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Malik S, Kelley GG, Kapiloff MS & Smrcka AV. (2011). Phospholipase C epsilon scaffolds to muscle-specific A kinase anchoring protein (mAKAPbeta) and integrates multiple hypertrophic stimuli in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 286, 23012–23021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Fang J, Gong J, Guo JH, Zhao GN, Ji YX, Liu HY, Wei X & Li H. (2016). Cardiac-Specific EPI64C Blunts Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Hypertension 67, 866–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Zhang W, Son H, Mansuy I, Sobel RA, Seidman J & Kandel ER. (1999). A selective role of calcineurin aalpha in synaptic depotentiation in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 4650–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]