Abstract

Earth-abundant metal pincer complexes have played an important role in homogeneous catalysis during the last ten years. Yet, despite intense research efforts, the synthesis of iron PCcarbeneP pincer complexes has so far remained elusive. Here we report the synthesis of the first PCNHCP functionalized iron complex [(PCNHCP)FeCl2] (1) and the reactivity of the corresponding trans-dihydride iron(II) dinitrogen complex [(PCNHCP)Fe(H)2N2)] (2). Complex 2 is stable under an atmosphere of N2 and is highly active for hydrogen isotope exchange at (hetero)aromatic hydrocarbons under mild conditions (50 °C, N2). With benzene-d6 as the deuterium source, easily reducible functional groups such as esters and amides are well tolerated, contributing to the overall wide substrate scope (e.g., halides, ethers, and amines). DFT studies suggest a complex assisted σ-bond metathesis pathway for C(sp2)–H bond activation, which is further discussed in this study.

Introduction

Driven by their pre-eminent two-electron chemistry, the predictable reactivity and selectivity of precious metals have made them the premier choice as catalysts in many synthetic processes.1 The growing environmental, economic, and geopolitical concerns associated with using precious metals, in conjunction with their limited availability, are strong incentives to rethink current strategies and establish more environmentally friendly alternatives.2 One such methodology relies on using earth-abundant metals such as cobalt,3 manganese4 and in particular iron,5 as catalyst for a variety of organic transformations.6 Indeed, during the past decade we have seen a resurgence of using earth-abundant metals in homogeneous catalysis. One of the main reasons behind this resurgence is our ability to utilize the unique properties of earth-abundant metals (e.g., spin-state reactivity) via elaborate ligand designs.7

From the wide variety of available ligand architectures, pincer-type ligands have contributed tremendously to the development of earth-abundant metal catalysis.8 The most commonly encountered structural motifs within this set of ligands are those featuring an XNX (X = NR, PR2, P(OR)2) pincer type geometry with a central amino or pyridine donor.8 In contrast, earth-abundant metal pincer complexes presenting a carbene as central donor are virtually absent from the literature,9 in particular those containing a PCNHCP type geometry (Figure 1).10 Their absence is quite surprising as carbenes often impart distinct electronic and steric properties to the metal center.11 For instance, when comparing PCP versus PNP pincer complexes of the second and third row transition metals, the PCP complexes featuring a central N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) typically bind stronger to the metal center,12 while simultaneously increasing its electron density,13 which benefits catalyst stability and reactivity.12a

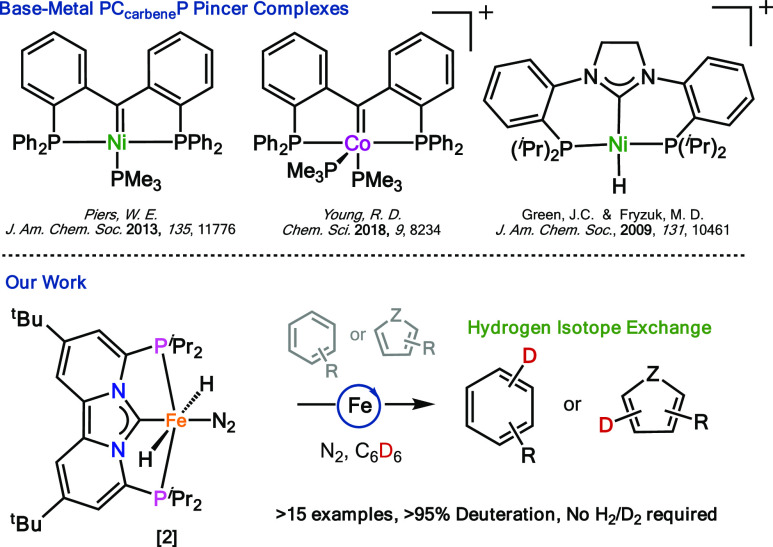

Figure 1.

Selected examples of first-row transition-metal PCcarbeneP pincer complexes and the herein reported reactivity of [(PCNHCP)Fe(H)2N2)] (2).

Yet, despite these advantages no catalytic activity of iron, cobalt, or manganese PCNHCP pincer complexes have been reported,14 while synthetic methodologies to access these complexes for iron are currently lacking.10b Considering these limitations, developing NHC-centered phosphine-functionalized pincer complexes could hold great benefits for iron-based catalysis, especially when containing metal-hydrides.15

Here we report the synthesis and characterization of novel PCNHCP pincer complex [(PCNHCP)FeCl2)] (1) that upon exposure to 2.2 equiv of NaBHEt3 generates the first example of a stable trans-dihydride iron(II) dinitrogen complex [(PCNHCP)Fe(H)2N2)] (Scheme 1; 2). Iron complex 2 is highly stable at room temperature and does not readily reductively eliminate H2 upon exposure to N2, which is a commonly observed deactivation pathway for other trans-dihydride iron(II) complexes lacking π-acidic CO ligands.15b,16 The equatorial N2 ligand in 2 is readily displaced under catalytic conditions enabling hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange at (hetero)aromatic hydrocarbons with benzene-d6 as deuterium source. Generally, the reaction occurs under mild conditions (N2, 50 °C), and is tolerant of a variety of functional groups including, ethers, esters, amides, halides, and heterocycles. To the best of our knowledge, complex 2 is one of the very few iron-based catalysts capable of catalytic H/D exchange at heteroaromatics using a readily available deuterium source.

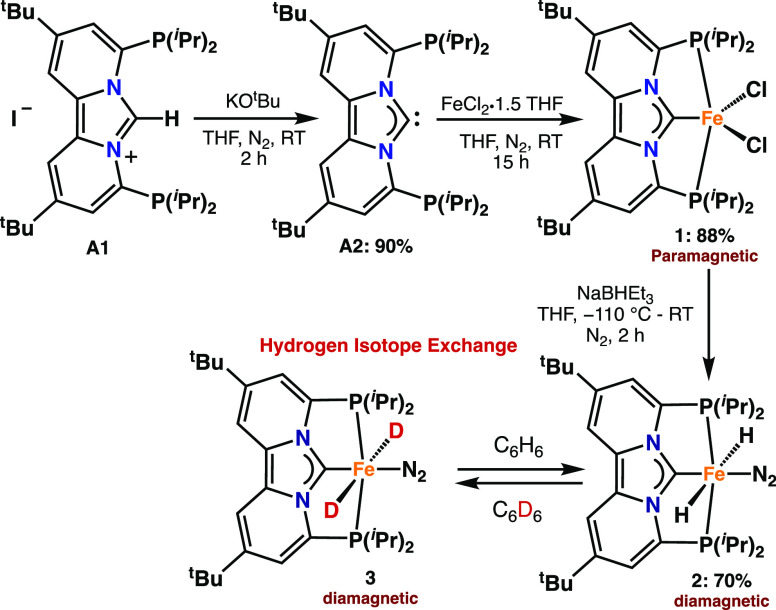

Scheme 1. Synthesis of PCNHCP Iron Complexes 1 and 2 and the Observed H/D Exchange in Benzene-d6.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Iron PCNHCP Pincer Complexes

Realizing the lack of current synthetic methodologies for preparing earth-abundant metal PCNHCP pincer complexes, we became interested in a ligand platform known as dipyrido[1,2-c;2′,1′-e]imidazolin-6-ylidenes,17 whose rigid framework might allow for strong binding of earth-abundant metals. We commenced our studies by synthesizing azolium salt A1 via a modification of a known literature procedure.17a Subsequent deprotonation of A1 with potassium tert-butoxide (KOtBu) in THF resulted in the formation of free carbene A2 (Scheme 1).

Addition of FeCl2·1.5THF (1.1 equiv) to a stirred solution of A2 in THF (15 mL) resulted in the formation of a new paramagnetic species (1) as judged by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure S12). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is consistent with the assignment of 1 as [(PCNHCP)FeCl2)] (Figure S13), which was also confirmed by X-ray crystallography.

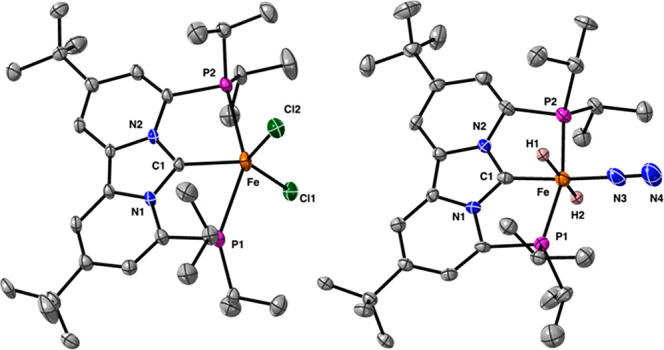

The solid-state structure of 1 is shown in Figure 2, and features an iron metal center in a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry. The axial phosphine donors are only weakly bound to the iron metal center, which is evident from the long iron phosphine distances of 2.782(2) Å (Fe–P1) and 2.765(2) Å (Fe–P2). The iron carbene (Fe–C1) distance of 2.062(6) and the NCN angle of 102.3(5)° are typical for other iron NHC complexes that are reported in the literature.18

Figure 2.

Solid state structures of [(PCNHCP)FeCl2] (1, left) and [(PCNHCP)Fe(H)2N2] (2, right). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 30% probability level. Hydrogen atoms (except H1 and H2) and cocrystallized solvent molecules are omitted for clarity.

With iron PCNHCP pincer complex 1 in hand, we investigated its reactivity toward a variety of hydride donors, because of the wide applicability of transition-metal hydrides in catalysis.8b,19 Addition, of two equiv of NaBHEt3 to a THF solution of complex 1 at −110 °C afforded a new diamagnetic species (2) that is stable for several days in solution at room temperature (Scheme 1). The 1H NMR spectrum of complex 2 exhibits a single characteristic triplet at −8.79 ppm (2H), whose 2JP–H values of 43.0 Hz are consistent with a tentative assignment of 2 as the trans-dihydride iron complex [(PCNHCP)Fe(H2)N2)]. Additional T1 measurements (at 298 K) support such a trans-dihydride assignment where the decay time of 420 ms is similar to those reported for other transition-metal trans-dihydride complexes.15b,16 Definite structural assignment of 2 was provided by X-ray crystallography (Figure 2). Although the crystals were not of sufficient quality to allow comparison of the bond metrics, it does allow for identification of complex 2 as [(PCNHCP)Fe(H)2N2)] with the coordinated N2 opposite to the PCNHCP carbene, forcing the two hydrides in a trans geometry. As a result, the combined spectroscopic (NMR) and crystallographic data confirm the formation of a stable classical iron(II) trans-dihydride, which is unprecedented.20

Hydrogen Isotope Exchange (HIE) at (Hetero)Aromatics

The ability to selectively exchange hydrogen for either deuterium or tritium is important for understanding many fundamental processes in organometallic,21 medicinal,22 and biological chemistry.23 Classically, HIE is catalyzed by noble metals such as ruthenium,24 rhodium,25 and iridium.26 In contrast, only a few studies report on the HIE with earth-abundant metals.27 Given the importance of earth-abundant metal-hydride species in hydrogen isotope exchange (HIE) reactions,28 we reasoned that iron complex 2 could be a straightforward entry toward facile H/D exchange at aromatic hydrocarbons.

Our studies into H/D exchange started with the observation that the hydride resonance at–8.79 ppm (t, 2JP–H = 43.0 Hz) in complex 2 slowly disappeared after dissolving 2 in benzene-d6. No other changes in the 1H NMR spectrum of 2 were observed. Analysis of the solution by 2H and 31P NMR spectroscopy revealed the appearance of a triplet (2H) at −8.68 ppm (2JP-D = 6.6 Hz) and a quintet (31P) at 133.27 ppm (2JD-P = 6.2 Hz), which is consistent with the formation of the dideuteride iron(II) complex 3 (Figure S3) Similarly, dissolving 3 in benzene results to the reformation of complex 2 in quantitative yields.

The reversible H/D exchange between the solvent and complex 2 indicates reversible C(sp2)–H activation, which is promising for allowing catalytic HIE with other hydrocarbons.25b,29 As evident from Table 1, complex 2 indeed efficiently catalyzes the H/D exchange between the solvent (benzene-d6) and a variety of (hetero)aromatic hydrocarbons. The reaction occurs under mild conditions (N2, 50–80 °C) and typically requires less than 3 h for high levels of deuterium incorporation. For example, toluene is exclusively deuterated at the meta and para positions (>95%), which are the sterically most accessible positions. (Table 1; [d3]-4). Likewise, for m-xylene, the meta-position was preferentially deuterated (98%). In both substrates, deuteration of the ortho position was not observed. These data suggest that for toluene and m-xylene, the observed regioselectivity is primarily dictated by steric factors. Computational studies (vide infra) corroborated these findings and showed that for toluene C–H bond activation at the meta and para positions is energetically more favorable than at the ortho position (Table 2). Note, however, that by using elevated temperatures and longer reaction times different regioselectivities can be observed (Figure S20 and S21). Notwithstanding, these results are akin to those obtained by Chirik27f and Leitner,24a whose iron and ruthenium pincer complexes; [H4-iPrCNC)Fe(N2)2] and [(PNP)Ru(H)2(H2)] showed comparable regioselectivity.

Table 1. Substrate Scope for Hydrogen Isotope Exchange at (Hetero)Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Catalyzed by 2a,b.

See the Supporting Information for experimental details.

Yields were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy in the presence of an internal standard (tetraethylsilane).

Table 2. Relative Energies (ΔG) in kcal mol–1 of the Transition State (TS1-R) for C–H Exchange at the ortho, meta, and para Positions of Toluene, Fluorobenzene, Anisole, and Dimethylanilinea,b.

| position |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| substituent | ortho | meta | para |

| R = H | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.2 |

| R = Me | 30.4 | 25.9 | 25.2 |

| R = NMe2 | 31.3 | 25.2 | 27.5 |

| R = OMe | 25.6 | 24.5 | 25.7 |

| R = F | 23.9 | 23.6 | 25.1 |

See the Supporting Information for computational details.

Encouraged by these initial results, we sought to increase the substrate scope to include a variety of electronically and sterically differentiated substrates (Table 1). For example, fluorobenzene was completely deuterated within 3 h (Table 1, [d5]-6). Monitoring the reaction by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopy revealed that the ortho and meta position are preferentially deuterated (Figure S71 and S72). Only after 30 min deuteration of the para position is observed, while complete deuteration of the para positions takes nearly 3 h. These results reflect the level of deuteration in the order of ortho (98%) > meta (95%) > para (90%) as shown in Table 1. Interestingly, for the related chlorobenzene deuterium incorporation was only observed at the para position, whereas for 4-fluoroanisole incorporation was observed at the ortho position (Table 1; [d1]-7 and [d2]-9). Clearly, besides the established steric effects, electronic effects are important contributors to the observed regioselectivity (vide infra). More detailed computational studies regarding the observed regioselectivity and mechanism for H/D exchange are presented in Figure 3 and Table 2, and are further discussed in the computational section of this manuscript. Nonetheless, the ability of 2 to efficiently deuterate chlorobenzene demonstrates that the complex 2 is stable toward reductive elimination of H2 and subsequent oxidative addition of the aryl halide.

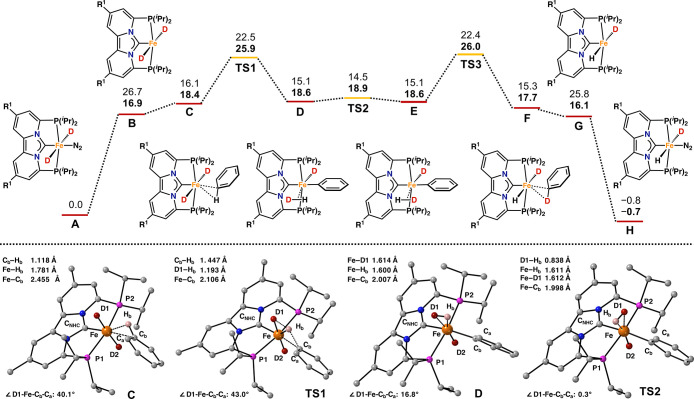

Figure 3.

Calculated free energy profiles (ΔH/ΔG) in kcal mol–1 and plausible mechanistic pathways for hydrogen isotope exchange (HIE) of 3 with benzene. Hydrogen atoms (except Hb) are omitted for clarity. For computational details, see the Supporting Information.

Besides aryl halides, arenes bearing other electron withdrawing substituents were efficiently deuterated as well, albeit primarily at sterically accessible C(sp2)–H bonds (Table 1; [d5]-10). In a similar manner, electron rich arenes were also efficiently deuterated. Dimethylaniline showed near quantitative incorporation of deuterium (>98%) at the meta and para positions, whereas for anisole complete deuteration was observed to yield anisole-d8 within the course of 3 h (Table 1).

Substrates containing reducible substituents such as esters ([d2]-12) and amides ([d3]-13) are tolerated as well. For instance, ethyl 4-fluorobenzoate is selectively deuterated at the ortho position (60%), while N,N-dimethylbenzamide is selectively deuterated at the meta and para positions (Table 1). The difference in regioselectivity between [d2]-12 and [d3]-13 is due to different steric requirements of the directing group, although electronic effects from the fluorine atom cannot be excluded. Unfortunately, substrates containing ketones (e.g., acetophenone, benzophenone, and/or cyclohexyl phenyl ketone) are not susceptible for catalytic H/D exchange. It is known that iron-dihydride complexes are good ketone hydrogenation catalysts.30 In the absence of a suitable proton donor, the iron-hydride is nucleophilic enough to attack the ketone to generate an alkoxide intermediate,31 that is incapable of performing HIE. However, catalyst decomposition to form inactive Fe(I) or Fe(0) species cannot be excluded.32 Nonetheless, these results do not negate the fact that complex 2, tolerates several functional groups (e.g., halides, ethers, esters, amides, and/or heterocycles).

In addition to the various substituted aromatic hydrocarbons, heteroaromatic compounds are also good substrates for HIE.. For instance, in 5-membered heterocyclic compounds, such as N-methyl-pyrrole, 1-methylimidazole, 2-methylfuran, and 2,5-dimethylfuran, most aromatic protons were deuterated with incorporation levels ranging from 80 to 98% (Table 1, [d2]-16–[d2]-19). In addition, for 2-methylfuran deuteration of the methyl substituent was also observed to a large extent (50%). Because of the vastly different physicochemical and electronic properties of pyrroles, imidazoles, and furans, it is difficult to rationalize the regioselectivity for each substrate individually. In general, H/D exchange of hydrogen atoms ortho to a heteroatom is highly favorable and is most-likely directed by precoordination of the heteroatom to the metal center. Precoordination also explains the deuteration of the C(sp3)–H bonds in 2-methyl furan (Table 1; [d3]-18). However, for 2,5-dimethylfuran ([d2]-19) and 2,6-dimethylpyridine ([d1]-15) coordination to the metal center is hampered due to steric crowding and deuteration of the C(sp3)–H bonds is not observed. Furthermore, for 5-membered heterocycles, deuteration of C–H bonds adjacent to methyl substituents is more feasible because they are sterically more accessible compared to their 6-membered counterparts (e.g., compare [d2]-16–[d2]-19 with [d1]-15). The exception appears to be N-methylpyrrole (Table 1, [d2]-16), whose lack of ortho reactivity we are not able to explain. For 6-membered aromatic heterocycles such as 2,6-lutidine deuteration was regioselective for the sterically most accessible para proton (Table 1, [d1]-15). For quinoline all aromatic C–H bonds were deuterated to yield quinoline-d7 (Table 1, [d7]-21). The different degree of deuteration in quinolinereflects the different bond dissociation energies of the various C(sp2)–H bonds.33

Comparing these results to the state-of-the-art, it was realized that despite the tremendous progress in homogeneous catalysis, earth-abundant metal catalyzed HIE at aromatic C(sp2)-H bonds remains extremely rare.27 For example, the cobalt catalyzed H/D exchange reported by Zou and co-workers is only applicable to indoles,27b while the cobalt catalysts developed by Chirik and co-workers primarily catalyze H/D exchange at (benzylic) C(sp3)-H bonds.27e For iron related studies, the seminal work of Chirik and co-workers is important as it describes the first example of the iron catalyzed HIE at aromatic C(sp2)-H bonds including those of pharmaceuticals.27f However, due to the instability of the in situ formed dihydride, hydrogen or deuterium gas is always required to ensure catalyst stability and efficiency as shown in a recent study.27a The herein reported results, however, demonstrate for the first time that such trans-dihydrides can be stable, ultimately leading to the deuteration of wide variety of aromatic hydrocarbons at lower temperatures with shorter reaction times and greater efficiencies,27f even when compared to PNP ruthenium dihydride complexes reported by Milstein and Leitner.24a However, it must be mentioned that comparison to the state-of-the-art is challenging due to the different nature of (i) the used solvents (e.g., benzene vs THF), (ii) the deuterium source (D2, D2O, or C6D6), and (iii) the used catalyst loadings.

Computational Mechanistic Investigations

To further understand the regioselectivity and to gain more insight into the mechanism of the H/D exchange between benzene-d6 and (hetero)aromatic hydrocarbons, we used density functional theory (DFT) to obtain more detailed information about the relevant intermediates and transition states (Figures 3). To reduce the computational load, calculations were performed on a model system with R1 = Me (Figure 3). Additional computational details are reported in the Supporting Information.

Before going into the details of the herein reported H/D exchange and C–H bond activation, there are several mechanisms by which C–H bonds can be activated that include (i) oxidative addition, (ii) σ-bond metathesis, and other types of mechanisms.34 Low valent (late) transition metals generally activate C(sp2)–H bonds via oxidative addition. High valent (early) transition metals, on the other hand, prefer a σ-bond metathesis pathway, because of their general lack of available d-electrons. A variant of σ-bond metathesis, σ-complex-assisted metathesis or σ-CAM, has also been developed for late transition metals in order to to explain the facile hydrogen exchange at bound E–H (E = B, C, or Si) σ -complexes.35 For example, Leitner,24a Lau,24b and others,36 have used σ-CAM to explain precious metal-catalyzed H/D exchange at aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons.

For iron, oxidative addition of C(sp2)–H bonds is well-known and has been established for nearly half a century.37 On the other hand, Eisenstein and co-workers have shown that, for iron, σ-CAM is another plausible mechanistic pathway for H/D exchange at aromatic hydrocarbons.38 Our computational studies indeed indicate that H/D exchange with benzene-d6 most likely occurs via a σ-CAM based mechanism (Figure 3). Starting from 3, labeled A in Figure 3, formation of the σ-complex C is a two-step process and energetically uphill by 18.4 kcal mol–1. The structure of intermediate C is shown in Figure 3 and features in an η2C–H interaction of benzene with the iron metal center resulting in elongation of the C–H bond by 0.032 Å. Such intermediates have also been implied for aromatic C(sp2)–H activation with ruthenium and iridium.39 The C(sp2)-carbon atom engaged in the η2C–H interaction is located 0.125 Å above the plane of the PCNHCP pincer ligand, while the Cb–Hb bond is rotated upward by 27.0° and located 0.420 Å above the PCNHCP plane. The slight upward rotation, might indicate an attractive interaction between the axial deuteride (D1) and Hb as their calculated distance of 2.098 Å is slightly shorter than the sum of their van der Waals radii (2.200 Å).38 The attractive interaction between D1 and the Cb–Hb bond is somewhat reminiscent of the hydride “cis effect” proposed by Eisenstein and Caulton,40 which describes the interaction between a metal-hydride and a coordinated dihydrogen molecule en-route toward dynamic hydrogen atom exchange. As such the “cis-effect” demonstrates important concepts that are also observed in the herein described σ-CAM (vide infra).35

The critical C–H activation step occurs via a σ-complex-assisted metathesis pathway and leads to the formation of the nonclassical hydride isotopologue (D) with an overall energy barrier (ΔG) of 25.9 kcal mol–1. The transition state structure (TS1) is shown in Figure 3 (bottom) and features an iron complex with a distorted pentagonal bipyramidal geometry. Obviously, starting from C, further distortion of the Fe···C axis is necessary to access the planar four-center transition state in TS1 that is typically observed for σ-CAM based mechanisms. In TS1, the calculated D1···Hb and Fe···Cb distances of 1.193 and 2.106 Å are significantly shorter than those found by Leitner and Milstein,24a and are indicative of a σ-CAM based mechanism with a late transition-state structure exhibiting very little oxidative addition character as shown by Eisenstein and co-workers.41 Overall, the barrier going from C to D is 7.5 kcal mol–1, indicating that H/D exchange occurs quite readily once the σ-complex is formed and that the slightly elevated temperatures (50 °C) are necessary to facilitate dissociation of the N2 ligand (Figure 3).

The formation of nonclassical hydride isotopologue D is also supported by NMR studies. Monitoring a solution of 2 in benzene-d6 shows the formation of a triplet at −8.79 ppm (1JH-D = 21.1 Hz) in the 1H{31P} NMR spectrum after 15 min (Figures S1–S4). The large value of the H–D coupling constant is indicative for the formation of a nonclassical hydride intermediate, as cis/trans HD couplings are general small or negligible.42 In this process, oxidative addition from an Fe(0)/Fe(II) complex was not observed experimentally and computationally.

Rotation around the iron H–D bond (Figure 3, D → E) is essentially barrierless and the transition state structure TS2 is shown in Figure 3 (bottom). The calculated bond lengths in TS2 do not differ significantly from those calculated for D and the complex remains essentially octahedral. After rotation, the first stage of the H/D exchange is complete (Figure 3, A → E). Hereafter, a nearly identical, but reverse, pathway follows that start with σ-CAM to yield the σ-bonded deuterated benzene adduct (F). Final two-step ligand exchange between the substrate and N2 regenerates an isotopologue of the starting catalyst (H). In general, the herein presented mechanism is similar to that proposed by Leitner and Milstein, whose ruthenium PNP complex also catalyzes H/D exchange between aromatic hydrocarbons and benzene-d6.24a Besides the mechanism outlined in Figure 3, a modified version is also energetically accessible (Figure S76; path B). In this mechanism, instead from the trans-dideuteride, σ-CAM is initiated from the iron(II) cis-dideuteride with a very similar transition state that is only 5.2 kcal mol–1 higher in energy.

We also used computational studies to gain more insight into the observed regioselectivity. For a series of substituted benzenes, we calculated the energy barriers of TS1-R (Table 2; R = H, Me, NMe2, OMe, and F). For benzene (R = H) the calculated barrier is 25.2 kcal mol–1 which is slightly lower than for TS1, due to isotope effects.43 Overall, as our calculations will show, the observed regioselectivity is combination of steric and electronic effects. As expected strong steric effects are observed for toluene (R = Me; Table 2). The energy barrier for ortho C–H bond activation (30.4 kcal mol–1) is significantly higher than for activation at the meta and para positions (ΔG = 25.9/25.2 kcal mol–1). Similar effects are observed for dimethylaniline, where C–H bond activation at the ortho position has an energy barrier of 31.3 kcal mol–1 (Table 2). These results are in-line with our experimental results (Table 1)

Because for anisole no strong steric effects are expected and precoordination of the heteroatom is commonly invoked in C–H bond activation strategies, there are no clear differences in the energies for ortho, meta, or para C–H bond activation. As a result, complete deuteration of all C–H bonds is observed, including those present in the −OMe substituent (Tables 1 and 2).

Besides the obvious steric effects, electronic effects are also important. This is particularly evident in fluorinated substrates [d5]-6 and [d2]-9. We begin by noting that the overall transition barriers TS1-F for C(sp2)–H activation in fluorinated substrates are lower than those calculated for their nonfluorinated counterparts (Table 2). Despite having the strongest C–H bond, the more facile activation of fluoroarenes is well-known and is due to the larger increase of the M–CAr bond strength relative to that of the CAr–H bond.44,45 This is particularly true when fluorine substituents are introduced at the ortho position as demonstrated by Jones and Perutz.46 This pronounced ortho-fluorine effect is clearly seen in [d2]-9, which shown nearly exclusive deuteration (∼85%) at ortho-position. Similarly, for fluorobenzene ([d5]-6), the highest level of deuteration is observed at ortho position (98%). In contrast, the para position shows a lower level of deuteration (∼90%), consistent with a transition state barrier that is 1.2 kcal mol–1 higher than that calculated for the ortho position (Table 2). Besides the electronic of fluorine, other electronic effects are observed as well. To illustrate, we calculated the natural charges on the aromatic carbons and hydrogen atom Hb (Figure S79). As expected upon C–H bond activation, additional negative charges develop on aromatic carbon atoms (incl. Cb), while a positive charge develops on Hb. Consequently, π-donation of the coplanar NMe2 substituent effectively destabilizes this negative charge, resulting in an overall higher activation energy for C–H bond activation (Table 2).

Overall, these computational studies show that for the majority of substrates the observed regioselectivity can be explained by a combination of steric and electronic factors (Table 2) and that a σ-CAM based mechanism is able to explain the observed HIE (Figure 3).

Conclusions

In summary, we have reported the synthesis and characterization of a rare trans-dihydride iron(II) dinitrogen complex (2) that is based on a novel PCNHCP pincer type motif. This compound is stable under N2 for several days and can be used for selective H/D exchange at (hetero)aromatic hydrocarbons with benzene-d6 as deuterium source. Deuterium incorporation typically exceeds 90% and is generally regioselective for sterically accessible C(sp2)–H bonds unless overriding electronic effects are present. Computational studies indicate that a σ-bond metathesis pathway is probably responsible for the observed hydrogen isotope exchange (HIE), which is accessible under mild conditions (N2, 50 °C). Overall, the herein reported results convey a convenient and straightforward method for H/D exchange that displays a wide functional group tolerance (e.g., esters, amides, halides, ethers, etc.). Furthermore, the robustness and stability of the herein reported catalyst holds great potential for other organic transformations that rely on hydride transfer or those that focus on small molecule activation. Current efforts are directed toward synthesizing the corresponding manganese, cobalt, and nickel complexes and exploring their reactivity in a variety of organic transformations.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by the Azrieli Foundation (Israel), and the Technion EVPR Fund – Mallat Family Research Fund. G.d.R. is an Azrieli young faculty fellow and a Horev Fellow supported by the Taub Foundation. G.de.R. kindly acknowledges the Israel Science Foundation for a personal research Grant (574/20) and and equipment grant (579/20).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c07689.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Cornils B.; Herrmann W. A.; Beller M.; Paciello R.. Applied Homogeneous Catalysis with Organometallic Compounds: A Comprehensive Handbook in Four Vol., 3rd ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]; b Hartwig J. F.Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- a Ludwig J. R.; Schindler C. S. Catalyst: Sustainable Catalysis. Chem. 2017, 2, 313–316. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Nakamura E.; Sato K. Managing the Scarcity of Chemical Elements. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 158–161. 10.1038/nmat2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapke M.; Hilt G.. Cobalt Catalysis in Organic Synthesis: Methods and Reactions; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- a Carney J. R.; Dillon B. R.; Thomas S. P. Recent Advances of Manganese Catalysis for Organic Synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 3912–3929. 10.1002/ejoc.201600018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Liu W.; Ackermann L. Manganese-Catalyzed C-H Activation. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3743–3752. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Fürstner A. Iron Catalysis in Organic Synthesis: A Critical Assessment of What It Takes To Make This Base Metal a Multitasking Champion. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 778–789. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bauer I.; Knölker H.-J. Iron Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3170–3387. 10.1021/cr500425u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbink R. J. M. K.; Moret M. E.. Non-Noble Metal Catalysis: Molecular Approaches and Reactions; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- a Fritz M.; Schneider S.. The Renaissance of Base Metal Catalysis Enabled by Functional Ligands. In The Periodic Table II: Catalytic, Materials, Biological and Medical Applications; Mingos D. M. P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp 1–36. [Google Scholar]; b Holland P. L. Reaction: Opportunities for Sustainable Catalysts. Chem. 2017, 2, 443–444. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Junge K.; Papa V.; Beller M. Cobalt-Pincer Complexes in Catalysis. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 122–143. 10.1002/chem.201803016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Alig L.; Fritz M.; Schneider S. First-Row Transition Metal (De)Hydrogenation Catalysis Based On Functional Pincer Ligands. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2681–2751. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wen H.; Liu G.; Huang Z. Recent Advances in Tridentate Iron and Cobalt Complexes gor Alkene and Alkyne Hydrofunctionalizations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 386, 138–153. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Mukherjee A.; Milstein D. Homogeneous Catalysis by Cobalt and Manganese Pincer Complexes. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 11435–11469. 10.1021/acscatal.8b02869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Gorgas N.; Kirchner K. Isoelectronic Manganese and Iron Hydrogenation/Dehydrogenation Catalysts: Similarities and Divergences. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1558–1569. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Bauer G.; Hu X. Recent Developments Of Iron Pincer Complexes For Catalytic Applications. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 741–765. 10.1039/C5QI00262A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Farrell K.; Albrecht M.. Late Transition Metal Complexes with Pincer Ligands that Comprise N-Heterocyclic Carbene Donor Sites. In The Privileged Pincer-Metal Platform: Coordination Chemistry & Applications; van Koten G., Gossage R. A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp 45–91. [Google Scholar]

- a Jiang Y.; Gendy C.; Roesler R. Nickel, Ruthenium, and Rhodium NCN-Pincer Complexes Featuring a Six-Membered N-Heterocyclic Carbene Central Moiety and Pyridyl Pendant Arms. Organometallics 2018, 37, 1123–1132. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Harris C. F.; Bayless M. B.; van Leest N. P.; Bruch Q. J.; Livesay B. N.; Bacsa J.; Hardcastle K. I.; Shores M. P.; de Bruin B.; Soper J. D. Redox-Active Bis(phenolate) N-Heterocyclic Carbene [OCO] Pincer Ligands Support Cobalt Electron Transfer Series Spanning Four Oxidation States. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 12421–12435. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Brown R. M.; Borau Garcia J.; Valjus J.; Roberts C. J.; Tuononen H. M.; Parvez M.; Roesler R. Ammonia Activation by a Nickel NCN-Pincer Complex featuring a Non-Innocent N-Heterocyclic Carbene: Ammine and Amido Complexes in Equilibrium. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6274–6277. 10.1002/anie.201500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kaplan H. Z.; Li B.; Byers J. A. Synthesis and Characterization of a Bis(imino)-N-heterocyclic Carbene Analogue to Bis(imino)pyridine Iron Complexes. Organometallics 2012, 31, 7343–7350. 10.1021/om300885d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Subramaniyan V.; Dutta B.; Govindaraj A.; Mani G. Facile Synthesis of Pd(II) and Ni(II) Pincer Carbene Complexes by the Double C-H Bond Activation of a New Hexahydropyrimidine-Based Bis(Phosphine): Catalysis of C-N Couplings. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 7203–7210. 10.1039/C8DT03413C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sung S.; Wang Q.; Krämer T.; Young R. D. Synthesis and Reactivity of a PCcarbeneP Cobalt(I) Complex: The Missing Link in the Cobalt PXP Pincer Series (X = B, C, N). Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 8234–8241. 10.1039/C8SC02782J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gutsulyak D. V.; Piers W. E.; Borau-Garcia J.; Parvez M. Activation of Water, Ammonia, and Other Small Molecules by PCcarbeneP Nickel Pincer Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11776–11779. 10.1021/ja406742n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Steinke T.; Shaw B. K.; Jong H.; Patrick B. O.; Fryzuk M. D.; Green J. C. Noninnocent Behavior of Ancillary Ligands: Apparent Trans Coupling of a Saturated N-Heterocyclic Carbene Unit with an Ethyl Ligand Mediated by Nickel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10461–10466. 10.1021/ja901346g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dröge T.; Glorius F. The Measure of All Rings—N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6940–6952. 10.1002/anie.201001865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Eizawa A.; Arashiba K.; Tanaka H.; Kuriyama S.; Matsuo Y.; Nakajima K.; Yoshizawa K.; Nishibayashi Y. Remarkable Catalytic Activity of Dinitrogen-Bridged Dimolybdenum Complexes Bearing NHC-Based PCP-Pincer Ligands Toward Nitrogen Fixation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14874. 10.1038/ncomms14874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Plikhta A.; Pöthig A.; Herdtweck E.; Rieger B. Toward New Organometallic Architectures: Synthesis of Carbene-Centered Rhodium and Palladium Bisphosphine Complexes. Stability and Reactivity of [PCBImPRh(L)][PF6] Pincers. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 9517–9528. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. M.; Mako T. L.; Vasilopoulos A.; Li B.; Byers J. A.; Neidig M. L. Magnetic Circular Dichroism and Density Functional Theory Studies of Iron(II)-Pincer Complexes: Insight into Electronic Structure and Bonding Effects of Pincer N-Heterocyclic Carbene Moieties. Organometallics 2016, 35, 3692–3700. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For earth-abundant metal catalysis with other types of carbene pincer complexes see:; a Harris C. F.; Kuehner C. S.; Bacsa J.; Soper J. D. Photoinduced Cobalt(III)-Trifluoromethyl Bond Activation Enables Arene C-H Trifluoromethylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1311–1315. 10.1002/anie.201711693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Manna C. M.; Kaplan H. Z.; Li B.; Byers J. A. High Molecular Weight Poly(Lactic Acid) Produced by an Efficient Iron Catalyst Bearing a Bis(Amidinato)-N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligand. Polyhedron 2014, 84, 160–167. 10.1016/j.poly.2014.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Morris R. H. Mechanisms of the H2- and Transfer Hydrogenation of Polar Bonds Catalyzed by Iron Group Hydrides. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 10809–10826. 10.1039/C8DT01804A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yu R. P.; Darmon J. M.; Semproni S. P.; Turner Z. R.; Chirik P. J. Synthesis of Iron Hydride Complexes Relevant to Hydrogen Isotope Exchange in Pharmaceuticals. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4341–4343. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gorgas N.; Alves L. G.; Stöger B.; Martins A. M.; Veiros L. F.; Kirchner K. Stable, Yet Highly Reactive Nonclassical Iron(II) Polyhydride Pincer Complexes: Z-Selective Dimerization and Hydroboration of Terminal Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8130–8133. 10.1021/jacs.7b05051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gorgas N.; Stöger B.; Veiros L. F.; Kirchner K. Highly Efficient and Selective Hydrogenation of Aldehydes: A Well-Defined Fe(II) Catalyst Exhibits Noble-Metal Activity. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2664–2672. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Langer R.; Diskin-Posner Y.; Leitus G.; Shimon L. J. W.; Ben-David Y.; Milstein D. Low-Pressure Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide Catalyzed by an Iron Pincer Complex Exhibiting Noble Metal Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9948–9952. 10.1002/anie.201104542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Langer R.; Leitus G.; Ben-David Y.; Milstein D. Efficient Hydrogenation of Ketones Catalyzed by an Iron Pincer Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2120–2124. 10.1002/anie.201007406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Yu Y.; Sadique A. R.; Smith J. M.; Dugan T. R.; Cowley R. E.; Brennessel W. W.; Flaschenriem C. J.; Bill E.; Cundari T. R.; Holland P. L. The Reactivity Patterns of Low-Coordinate Iron-Hydride Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6624–6638. 10.1021/ja710669w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovitch R. J.; Lobkovsky E.; Chirik P. J. Bis(diisopropylphosphino)pyridine Iron Dicarbonyl, Dihydride, and Silyl Hydride Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 7252–7260. 10.1021/ic0608647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fuku-En S.-i.; Yamamoto J.; Kojima S.; Yamamoto Y. Synthesis and Application of New Dipyrido-Annulated N-heterocyclic Carbene with Phosphorus Substituents. Chem. Lett. 2014, 43, 468–470. 10.1246/cl.131074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fuku-En S.-i.; Yamamoto J.; Minoura M.; Kojima S.; Yamamoto Y. Synthesis of New Dipyrido-Annulated N-Heterocyclic Carbenes with Ortho Substituents. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 11700–11702. 10.1021/ic402301u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gierz V.; Seyboldt A.; Maichle-Moessmer C.; Froehlich R.; Rominger F.; Kunz D. Straightforward Synthesis of Dipyrido-Annelated NHC-palladium(II) Complexes by Oxidative Addition. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 1423–1429. 10.1002/ejic.201100905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Nonnenmacher M.; Kunz D.; Rominger F. Synthesis and Catalytic Properties Of Rhodium(I) and Copper(I) Complexes Bearing Dipyrido-Annulated N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Organometallics 2008, 27, 1561–1568. 10.1021/om701196c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Nonnenmacher M.; Kunz D.; Rominger F.; Oeser T. X-Ray Crystal Structures of 10π- and 14π-Electron Pyrido-Annelated N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Chem. Commun. 2006, 1378–1380. 10.1039/b517816a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Nonnenmacher M.; Kunz D.; Rominger F.; Oeser T. First Examples of Dipyrido[1,2-C:2′,1′-E]Imidazolin-7-Ylidenes Serving as NHC-Ligands: Synthesis, Properties and Structural Features of their Chromium and Tungsten Pentacarbonyl Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 5647–5653. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Schremmer C.; Cordes C.; Klawitter I.; Bergner M.; Schiewer C. E.; Dechert S.; Demeshko S.; John M.; Meyer F. Spin-State Variations of Iron(III) Complexes with Tetracarbene Macrocycles. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 3918–3929. 10.1002/chem.201805855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schneider H.; Schmidt D.; Eichhöfer A.; Radius M.; Weigend F.; Radius U. Synthesis and Reactivity of NHC-Stabilized Iron(II)-Mesityl Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017, 2600–2616. 10.1002/ejic.201700143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liang Q.; Janes T.; Gjergji X.; Song D. Iron Complexes of a Bidentate Picolyl-NHC Ligand: Synthesis, Structure and Reactivity. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13872–13880. 10.1039/C6DT02792J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ouyang Z.; Du J.; Wang L.; Kneebone J. L.; Neidig M. L.; Deng L. Linear and T-Shaped Iron(I) Complexes Supported by N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands: Synthesis and Structure Characterization. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 8808–8816. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zlatogorsky S.; Muryn C. A.; Tuna F.; Evans D. J.; Ingleson M. J. Synthesis, Structures, and Reactivity of Chelating Bis-N-Heterocyclic-Carbene Complexes of Iron(II). Organometallics 2011, 30, 4974–4982. 10.1021/om200605b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wiedner E. S.; Chambers M. B.; Pitman C. L.; Bullock R. M.; Miller A. J. M.; Appel A. M. Thermodynamic Hydricity of Transition Metal Hydrides. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8655–8692. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang D.; Astruc D. The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6621–6686. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Larionov E.; Li H.; Mazet C. Well-Defined Transition Metal Hydrides in Catalytic Isomerizations. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 9816–9826. 10.1039/C4CC02399D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Pospech J.; Fleischer I.; Franke R.; Buchholz S.; Beller M. Alternative Metals for Homogeneous Catalyzed Hydroformylation Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2852–2872. 10.1002/anie.201208330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Recent Advances in Hydride Chemistry; Peruzzini M., Poli R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2001; pp 1–578. [Google Scholar]

- trans-Dihydride iron complexes lacking stabilizing carbonyl ligands, readily reductively eliminate H2 when exposed to an atmosphere N2. The resulting Fe(0) complexes are either (I) inactive for HIE, see for example:; Yu R. P.; Darmon J. M.; Semproni S. P.; Turner Z. R.; Chirik P. J. Synthesis of Iron Hydride Complexes Relevant to Hydrogen Isotope Exchange in Pharmaceuticals. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4341–4343. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; or (ii) they are very sluggish catalysts for HIE exchange see:Corpas J.; Viereck P.; Chirik P. J. C(sp2)-H Activation with Pyridine Dicarbene Iron Dialkyl Complexes: Hydrogen Isotope Exchange of Arenes Using Benzene-d6 as a Deuterium Source. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8640–8647. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Parkin G. Applications of Deuterium Isotope Effects for Probing Aspects of Reactions Involving Oxidative Addition and Reductive Elimination of H-H and C-H Bonds. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2007, 50, 1088–1114. 10.1002/jlcr.1435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Jones W. D. Isotope Effects in C-H Bond Activation Reactions by Transition Metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 140–146. 10.1021/ar020148i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Katsnelson A. Heavy Drugs Draw Heavy Interest From Pharma Backers. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 656–656. 10.1038/nm0613-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Elmore C. S.The Use of Isotopically Labeled Compounds in Drug Discovery. In Annu. Rep. Med. Chem.; Macor J. E., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 2009; Vol. 44, pp 515–534.

- Atzrodt J.; Derdau V.; Kerr W. J.; Reid M. Deuterium- and Tritium-Labelled Compounds: Applications in the Life Sciences. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1758–1784. 10.1002/anie.201704146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Prechtl M. H. G.; Hölscher M.; Ben-David Y.; Theyssen N.; Loschen R.; Milstein D.; Leitner W. H/D Exchange at Aromatic and Heteroaromatic Hydrocarbons Using D2O as the Deuterium Source and Ruthenium Dihydrogen Complexes as the Catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2269–2272. 10.1002/anie.200603677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ng S. M.; Lam W. H.; Mak C. C.; Tsang C. W.; Jia G.; Lin Z.; Lau C. P. C-H Bond Activation by a Hydrotris(pyrazolyl)borato Ruthenium Hydride Complex. Organometallics 2003, 22, 641–651. 10.1021/om0209024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Di Giuseppe A.; Castarlenas R.; Pérez-Torrente J. J.; Lahoz F. J.; Oro L. A. Hydride-Rhodium(III)-N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysts for Vinyl-Selective H/D Exchange: A Structure-Activity Study. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 8391–8403. 10.1002/chem.201402499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lenges C. P.; White P. S.; Brookhart M. Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Reactions and Transfer Hydrogenations Catalyzed by [C5Me5Rh(olefin)2] Complexes: Conversion of Alkoxysilanes to Silyl Enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 4385–4396. 10.1021/ja984409o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Blake M. R.; Garnett J. L.; Gregor I. K.; Hannan W.; Hoa K.; Long M. A. Rhodium Trichloride as a Homogeneous Catalyst for Isotopic Hydrogen Exchange. Comparison with Heterogeneous Rhodium in the Deuteriation of Aromatic Compounds and Alkanes. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1975, 930–932. 10.1039/c39750000930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Nilsson G. N.; Kerr W. J. The Development and use of Novel Iridium Complexes as Catalysts for Ortho-Directed Hydrogen Isotope Exchange Reactions. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2010, 53, 662–667. 10.1002/jlcr.1817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Corberán R.; Sanaú M.; Peris E. Highly Stable Cp*-Ir(III) Complexes with N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands as C-H Activation Catalysts for the Deuteration of Organic Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3974–3979. 10.1021/ja058253l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yung C. M.; Skaddan M. B.; Bergman R. G. Stoichiometric and Catalytic H/D Incorporation by Cationic Iridium Complexes: A Common Monohydrido-Iridium Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13033–13043. 10.1021/ja046825g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Klei S. R.; Golden J. T.; Tilley T. D.; Bergman R. G. Iridium-Catalyzed H/D Exchange into Organic Compounds in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2092–2093. 10.1021/ja017219d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Ellames G. J.; Gibson J. S.; Herbert J. M.; McNeill A. H. The Scope and Limitations of Deuteration Mediated by Crabtree’s Catalyst. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 9487–9497. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00945-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Heys R. Investigation of [IrH2(Me2CO)2(PPh3)2]BF4 as a Catalyst of Hydrogen Isotope Exchange of Substrates in Solution. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 680–681. 10.1039/c39920000680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Corpas J.; Viereck P.; Chirik P. J. C(sp2)-H Activation with Pyridine Dicarbene Iron Dialkyl Complexes: Hydrogen Isotope Exchange of Arenes Using Benzene-d6 as a Deuterium Source. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8640–8647. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang J.; Zhang S.; Gogula T.; Zou H. Versatile Regioselective Deuteration of Indoles via Transition-Metal-Catalyzed H/D Exchange. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 7486–7494. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zarate C.; Yang H.; Bezdek M. J.; Hesk D.; Chirik P. J. Ni(I)-X Complexes Bearing a Bulky α-Diimine Ligand: Synthesis, Structure, and Superior Catalytic Performance in the Hydrogen Isotope Exchange in Pharmaceuticals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5034–5044. 10.1021/jacs.9b00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yang H.; Zarate C.; Palmer W. N.; Rivera N.; Hesk D.; Chirik P. J. Site-Selective Nickel-Catalyzed Hydrogen Isotope Exchange in N-Heterocycles and Its Application to the Tritiation of Pharmaceuticals. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10210–10218. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Palmer W. N.; Chirik P. J. Cobalt-Catalyzed Stereoretentive Hydrogen Isotope Exchange of C(sp3)-H Bonds. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5674–5678. 10.1021/acscatal.7b02051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Pony Yu R.; Hesk D.; Rivera N.; Pelczer I.; Chirik P. J. Iron-Catalysed Tritiation of Pharmaceuticals. Nature 2016, 529, 195–199. 10.1038/nature16464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Lenges C. P.; White P. S.; Marshall W. J.; Brookhart M. Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of [C5Me5CoLL‘] Complexes with L = Pyridine and L’ = Olefin or L-L’ = Bipyridine. Organometallics 2000, 19, 1247–1254. 10.1021/om990860s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Yang H.; Hesk D. Base Metal-Catalyzed Hydrogen Isotope Exchange. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2020, 63, 296–307. 10.1002/jlcr.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Atzrodt J.; Derdau V.; Fey T.; Zimmermann J. The Renaissance of H/D Exchange. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7744–7765. 10.1002/anie.200700039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou J.; Hartwig J. F. Iridium-Catalyzed H/D Exchange at Vinyl Groups without Olefin Isomerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5783–5787. 10.1002/anie.200801992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Feng Y.; Lail M.; Foley N. A.; Gunnoe T. B.; Barakat K. A.; Cundari T. R.; Petersen J. L. Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange between TpRu(PMe3)(L)X (L = PMe3 and X = OH, OPh, Me, Ph, or NHPh; L = NCMe and X = Ph) and Deuterated Arene Solvents: Evidence for Metal-Mediated Processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 7982–7994. 10.1021/ja0615775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Giunta D.; Hölscher M.; Lehmann C. W.; Mynott R.; Wirtz C.; Leitner W. Room Temperature Activation of Aromatic C-H Bonds by Non-Classical Ruthenium Hydride Complexes Containing Carbene Ligands. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003, 345, 1139–1145. 10.1002/adsc.200303091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Golden J. T.; Andersen R. A.; Bergman R. G. Exceptionally Low-Temperature Carbon-Hydrogen/Carbon-Deuterium Exchange Reactions of Organic and Organometallic Compounds Catalyzed by the Cp*(PMe3)IrH(ClCH2Cl)+ Cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 5837–5838. 10.1021/ja0155480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Smith S. A. M.; Lagaditis P. O.; Lüpke A.; Lough A. J.; Morris R. H. Unsymmetrical Iron P-NH-P’ Catalysts for the Asymmetric Pressure Hydrogenation of Aryl Ketones. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 7212–7216. 10.1002/chem.201701254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sonnenberg J. F.; Wan K. Y.; Sues P. E.; Morris R. H. Ketone Asymmetric Hydrogenation Catalyzed by P-NH-P’ Pincer Iron Catalysts: An Experimental and Computational Study. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 316–326. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Yang X. Unexpected Direct Reduction Mechanism for Hydrogenation of Ketones Catalyzed by Iron PNP Pincer Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 12836–12843. 10.1021/ic2020176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello G. R.; Hopmann K. H. A Dihydride Mechanism Can Explain the Intriguing Substrate Selectivity of Iron-PNP-Mediated Hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5847–5855. 10.1021/acscatal.7b00764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- After addition of the ketone, the reaction mixture turns from yellow/brown to dark green, which might indicate formation of an iron(0) species. Other iron(0) species have been isolated by us, which are all green. However, formation of a metal-enolate species, or stoichiometric reduction of the ketone cannot be exclusively excluded.

- a Wren S. W.; Vogelhuber K. M.; Garver J. M.; Kato S.; Sheps L.; Bierbaum V. M.; Lineberger W. C. C-H Bond Strengths and Acidities in Aromatic Systems: Effects of Nitrogen Incorporation in Mono-, Di-, and Triazines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6584–6595. 10.1021/ja209566q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Luo Y. R.Handbook of Bond Dissociation Energies in Organic Compounds; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- a Gandeepan P.; Müller T.; Zell D.; Cera G.; Warratz S.; Ackermann L. 3d Transition Metals for C-H Activation. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2192–2452. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Balcells D.; Clot E.; Eisenstein O. C—H Bond Activation in Transition Metal Species from a Computational Perspective. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 749–823. 10.1021/cr900315k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Labinger J. A.; Bercaw J. E. Understanding and Exploiting C-H Bond Activation. Nature 2002, 417, 507–514. 10.1038/417507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Shilov A. E.; Shul’pin G. B. Activation of C-H Bonds by Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2879–2932. 10.1021/cr9411886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz R. N.; Sabo-Etienne S. The σ-CAM Mechanism: σ Complexes as the Basis of σ-Bond Metathesis at Late-Transition-Metal Centers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2578–2592. 10.1002/anie.200603224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe A.; Castarlenas R.; Oro L. A. Mechanistic Considerations on Catalytic H/D Exchange Mediated by Organometallic Transition Tetal Complexes. C. R. Chim. 2015, 18, 713–741. 10.1016/j.crci.2015.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Dombray T.; Werncke C. G.; Jiang S.; Grellier M.; Vendier L.; Bontemps S.; Sortais J.-B.; Sabo-Etienne S.; Darcel C. Iron-Catalyzed C-H Borylation of Arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4062–4065. 10.1021/jacs.5b00895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Azizian H.; Morris R. H. Photochemical Synthesis and Reactions of FeH(C6H4PPhCH2CH2PPh2)(PPh2PCH2CH2PPh2). Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 6–9. 10.1021/ic00143a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Tolman C. A.; Ittel S. D.; English A. D.; Jesson J. P. Chemistry of 2-Naphthyl Bis[bis(dimethylphosphino)ethane] Hydride Complexes of Iron, Ruthenium, and Osmium. 3. Cleavage of sp2 Carbon-Hydrogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 1742–1751. 10.1021/ja00501a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Hata G.; Kondo H.; Miyake A. Ethylenebis(Diphenylphosphine) Complexes of Iron And Cobalt. Hydrogen Transfer between the Ligand and Iron Atom. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2278–2281. 10.1021/ja01011a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mantina M.; Chamberlin A. C.; Valero R.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Consistent van der Waals Radii for the Whole Main Group. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 5806–5812. 10.1021/jp8111556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari E.; Cohen R.; Gandelman M.; Shimon L. J. W.; Martin J. M. L.; Milstein D. Ortho C-H Activation of Haloarenes and Anisole by an Electron-Rich Iridium(I) Complex: Mechanism and Origin of Regio- and Chemoselectivity. AnExperimental and TheoreticalStudy. Organometallics 2006, 25, 3190–3210. 10.1021/om060078+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sluys L. S.; Eckert J.; Eisenstein O.; Hall J. H.; Huffman J. C.; Jackson S. A.; Koetzle T. F.; Kubas G. J.; Vergamini P. J.; Caulton K. G. An Attractive cis-Effect of Hydride on Neighbor Ligands: Experimental and Theoretical Studies on the Structure and Intramolecular Rearrangements of Fe(H)2(η2-H2)(PEtPh2)3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4831–4841. 10.1021/ja00168a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam W. H.; Jia G.; Lin Z.; Lau C. P.; Eisenstein O. Theoretical Studies on the Metathesis Processes, [Tp(PH3)MR(η2-H-CH3)]-[Tp(PH3)M(CH3)(η2-H-R)] (M = Fe, Ru, and Os; R = H and CH3). Chem. - Eur. J. 2003, 9, 2775–2782. 10.1002/chem.200204570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Crabtree R. H. Dihydrogen Complexation. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8750–8769. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Morris R. H. Dihydrogen, Dihydride and in Between: NMR and Structural Properties of Iron Group Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 2381–2394. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Jessop P. G.; Morris R. H. Reactions of Transition Metal Dihydrogen Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1992, 121, 155–284. 10.1016/0010-8545(92)80067-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Computationally, the only difference between hydrogen and deuterium atoms are in the vibrational modes, as a result the respective potential energy surfaces (PESs) will be nearly identical except for their relative energies. Typically, PESs that include deuterium are slightly higher in energy (ca. 0.4 kcal/mol). For more information see the Supporting Information for additional computational details.

- a Clot E.; Mégret C.; Eisenstein O.; Perutz R. N. Exceptional Sensitivity of Metal-Aryl Bond Energies to ortho-Fluorine Substituents: Influence of the Metal, the Coordination Sphere, and the Spectator Ligands on M-C/H-C Bond Energy Correlations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7817–7827. 10.1021/ja901640m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Evans M. E.; Burke C. L.; Yaibuathes S.; Clot E.; Eisenstein O.; Jones W. D. Energetics of C-H Bond Activation of Fluorinated Aromatic Hydrocarbons Using a [Tp’Rh(CNneopentyl)] Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13464–13473. 10.1021/ja905057w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Clot E.; Besora M.; Maseras F.; Mégret C.; Eisenstein O.; Oelckers B.; Perutz R. N. Bond Energy M-C/H-C Correlations: Dual Theoretical and Experimental Approach to the Sensitivity of M-C Bond Strength to Substituents. Chem. Commun. 2003, 490–491. 10.1039/b210036n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For M-C/H-C bond energy correlations in nonfluorinated systems see:; a Clot E.; Mégret C.; Eisenstein O.; Perutz R. N. Validation of the M-C/H-C Bond Enthalpy Relationship through Application of Density Functional Theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8350–8357. 10.1021/ja061803a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jones W. D.; Hessell E. T. Photolysis of Tp’Rh(Cn-Neopentyl)(η2-PhN:C:N-Neopentyl) in Alkanes and Arenes: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Selectivity ff [Tp’Rh(Cn-Neopentyl)] for Various Types of Carbon-Hydrogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 554–562. 10.1021/ja00055a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selmeczy A. D.; Jones W. D.; Partridge M. G.; Perutz R. N. Selectivity in the Activation of Fluorinated Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Rhodium Complexes [(C5H5)Rh(PMe3)] and [(C5Me5)Rh(PMe3)]. Organometallics 1994, 13, 522–532. 10.1021/om00014a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.