Abstract

Background and Aims:

Antenatal oral care has been given least priority on a global scale. The study assesses self-perception of oral health knowledge and related behaviors among antenatal mothers.

Method:

A cross-sectional study was done among 400 pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic of a tertiary care center in Kerala, India. Details regarding knowledge, attitude, and practice were obtained, after getting an informed consent. The dental caries experience and gingival status were measured. To test the significance (p ≤ 0.05) between variables, Chi-square test was used.

Results:

Poor oral health knowledge was observed among 75.5% of the pregnant mothers. Oral health problems were reported by 63.2% of them. Low priority for oral health (59.4%) and fear for fetal safety (17.5%) were the reasons for delaying dental services. Oral examination showed that more than half of the study subjects had a high prevalence of dental caries (67.5%) and low gingival bleeding status (26.2%). The study highlights that more than half of the study population (60.8%) were influenced by the elderly in the family to avoid certain food items. A better oral health knowledge was observed among the upper middle class (OR - 2.8) who had visited dentists within the last six months (OR - 3.6) and child bearing mothers (OR- 0.46) (p ≤ 0.05).

Keywords: Antenatal, barriers, behavior, dental caries, knowledge, oral health, self-perception, utilization

Background

Pregnancy is a unique time in a woman's life where she is motivated to care for her own health as well as for her baby. Every mother has a responsible role as a care giver during the early years of her child. The prevalence of dental problems is reported to be high among the antenatal mothers than the general population where the mother's oral health has an impact on their children's health.[1] The oral health of pregnant mothers is greatly influenced by hormonal variation and dietary changes. Poor oral hygiene along with hormonal changes can aggravate the risk of periodontal disease and its adverse pregnancy outcomes such as premature birth and low birth weight babies.[2] Dental caries can be transmitted from mothers directly through their infected saliva while sharing the same spoon and kissing her baby.[3]

Craving for certain foods like sweets, pickles and sour food items are common during pregnancy. However, such habits may lead to systemic diseases like hypertension and diabetes mellitus which have direct link to dental caries and gingivitis.[4,5]

Globally, the use of dental service utilization during pregnancy is low as a result of poor attitude and lack of oral health knowledge.[6] The low utilization and delay in dental services has been linked to various barriers such as financial burden, time constraints, unawareness, concerns related to mother and fetal safety, along with lack of emphasis from antenatal care providers.[7]

India is a young, low middle income and the second most populous country in the world, with a diverse geography, society and tradition. To provide safe motherhood and accessible quality care, national public health programs like Janani Suraksha Yojna (JSY) and Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Jojana (PMSMJ) have been implemented by the Govt. of India. The geographical vastness and enormous sociocultural diversity indicate these antenatal programs varies across the country especially in the maternal health care utilization. Hence, uniform health sector reforms are a real challenge to implement in the country. The effectiveness of these program envisages several instrumental changes in the health sector but does not quantify oral health. The present study assesses the self-perception on oral health knowledge and related behaviors among pregnant women receiving antenatal care.

Relevance to practice of primary care physician

During pregnancy, women are at a greater risk of experiencing poor oral health and this can affect pregnancy outcome.[8] Misconceptions on oral health and delay in utilizing dental care can have consequences on maternal and fetal health.[9] With increasing links between oral and general health problems it is essential for the physician to know the impact of dental caries and periodontal diseases and its associated risk factors on women's overall health.[10]

This can help the physician to make appropriate decisions regarding timely and effective oral health intervention. Thus the combined and coordinated preventive oral health care approaches by the dentists and the physicians are important for a healthy motherhood.

Methods

A cross sectional study was conducted at the antenatal clinic of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of a tertiary care center after getting informed consent among expectant mothers who were willing to participate. The Institutional Ethics and Review Board at the Government Dental College, Kottayam, approved the study (date of approval 15-11-2017). A pilot study was carried out and the sample size was estimated to be 400.

Data collection

Information on socio demographic factors like age, type of family, gestational period, parity status and self-perception on oral health and related behaviors were recorded. Kuppuswamy Scale (2016) was used to assess the socio economic status.[11] Each correct response on knowledge was marked as “one” and the incorrect as “zero” and the overall knowledge was assessed by adding the scores. Questions were translated to local language (Malayalam) with the help of two language experts proficient in both English and Malayalam. An independent evaluator compared both the versions and finalized a Malayalam version which was then back translated. The dental caries experience and gingival status were also assessed using WHO criteria; DMFT Index and gingival bleeding on probing.[12]

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for windows (version 16; SPSS Inc; Chicago IL, USA). Descriptive statistics and Chi square test were done. Associations and differences were considered significant when the P value was less than 0.05.

Result

Demographic details of antenatal mothers are provided in Table 1, where the majority of participants belonged to the age group 25-30 years (mean age-27 years). More than half of the participants were in the third trimester, nulliparous and belonged to the lower socio-economic class.

Table 1.

Demographic Details of antenatal mothers

| Demographic variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ≤24 | 137 (34.2%) |

| 25-30 | 160 (40%) | |

| ≥31 | 103 (25.8%) | |

| Gestational Period | First Trimester | 64 (16%) |

| Second trimester | 115 (28.7%) | |

| Third trimester | 221 (55.2%) | |

| Parity Nulliparous* | 229 (57.2%) | |

| Primi/Multiparous** | 171 (42.8%) | |

| Family Nuclear Family | 198 (49.5%) | |

| Joint Family | 202 (50.55%) | |

| Socio Economic Status | Upper Middle class | 58 (14.5%) |

| Lower middle class | 90 (22.5%) | |

| Lower class | 252 (63%) |

* First child, ** One or more child

Three fourth of the antenatal mothers had poor oral health knowledge as shown in Table 2, whereby questions related to time of eruption of baby's first tooth, time to commence dental care and the importance to care for milk tooth was reported by less than 40% of the study population. According to 20% of the participants, the second trimester was considered safe for dental treatment. More than half (56%) of the participants were of the opinion that oral health has an influence on overall health.

Table 2.

Oral health knowledge and attitude of antenatal mothers

| A. Oral Health Knowledge of antenatal mothers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Questions | Response n (%) | |

| Influence of oral health on overall Health | Yes | 224 (56%) |

| No | 111 (27.8%) | |

| Not aware | 65 (16.3%) | |

| Ideal time to start dental care of the baby | Before tooth erupts | 150 (37.5%) |

| After tooth erupts | 164 (41%) | |

| Not aware | 86 (21.5%) | |

| Time of eruption of baby’s first tooth | Before 6 months | 33 (8.2%) |

| 6 - 10 months | 141 (35.3%) | |

| After 10 months | 64 (16%) | |

| Not aware | 162 (40.5%) | |

| Need of treatment for the milk teeth | Not needed | 147 (36.8%) |

| Needed | 146 (36.5%) | |

| Not aware | 107 (26.8%) | |

| Safe period for dental treatment during pregnancy | 1-3 months | 47 (11.8%) |

| 3-6 months | 79 (19.8%) | |

| 6-9 months | 16 (4%) | |

| Not aware | 258 (64.5%) | |

| B. Attitude towards oral health among ante natal mothers | ||

| Self-Reported perception of | Good | 258 (64.5%) |

| Oral Health | Bad | 142 (35.5%) |

| Willingness for dental | Yes | 182 (45.5%) |

| treatment during Pregnancy | No | 218 (54.5%) |

| Willingness to seek dietary | Yes | 343 (85.8%) |

| pattern during pregnancy | No | 57 (14.2%) |

| Reasons for refusing treatment | Fear of dental | 32 (14.7%) |

| for the dental problems during | treatment | |

| pregnancy | No need to seek dental treatment now | 129 (59.4%) |

| Financial problem | 6 (2.8%) | |

| Influence from | 12 (5.5%) | |

| family | ||

| Fear that the foetus | 38 (17.5%) | |

| will be affected | ||

| Willingness to accept free | Yes | 301 (75.2%) |

| dental treatment | No | 44 (11%) |

| Not sure | 55 (13.8%) | |

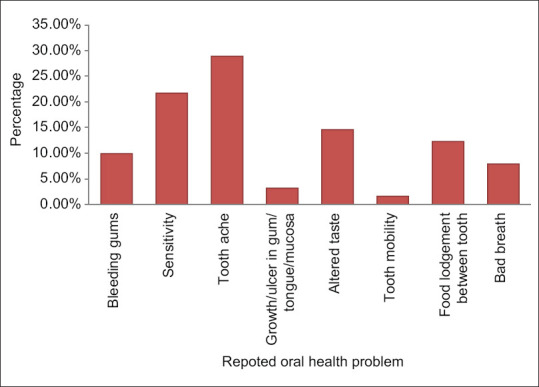

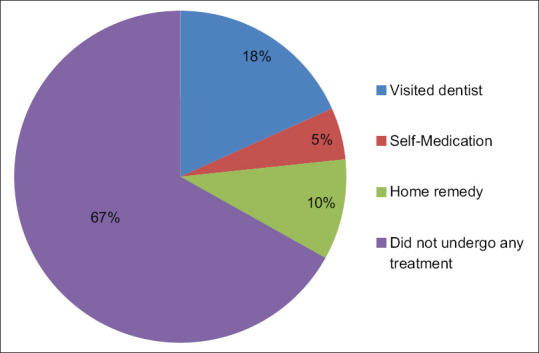

Self-perception of good oral health was reported by 64.5% of the antenatal mothers. The self-perceived oral health problems were tooth ache, altered taste, sensitivity, food lodgment and gingival bleeding [Figure 1]. Among those who reported (63.2%) oral health problems, only 18% had visited the dentist [Figure 2]. The response to the reasons indicated for delay in treatment were low oral health priority and the safety of their fetus (17.5%) [Table 2]. Oral examination showed that more than half of the study subjects had a high prevalence of dental caries (67.5%) and low gingival bleeding status (26.2%), Fluoridated toothpaste (90%) and toothbrush (95.7%) were used twice daily (75.2%) by most of the subjects, whereas 24.2% expressed difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene, especially while using toothbrush. More than half of them (60.2%) regularly changed their toothbrush within a span of 3 months [Table 3a].

Figure 1.

The self perceived oral health problems among the antenatal mothers

Figure 2.

Remedy for the reported oral health problems

Table 3.

Oral Hygiene and Dietary Practices

| Oral Hygiene Practices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty for cleaning the teeth | Yes | 54 (13.4%) |

| No | 303 (75.8%) | |

| At times | 43 (10.8%) | |

| Method of cleaning | Tooth brush | 383 (95.7%) |

| Finger | 11 (2.7%) | |

| Others | 6 (1.6%) | |

| Frequency of changing tooth brush | Within 3 months | 241 (60.2%) |

| Within 6 months | 118 (29.5%) | |

| More than 6 months | 41 (10.3%) | |

| Material used for cleaning your teeth | Tooth paste | 360 (90%) |

| Tooth powder | 22 (5.5%) | |

| Charcoal | 5 (1.3%) | |

| Combination | 13 (3.3%) | |

| Frequency of tooth brushing | Once daily | 99 (24.8%) |

| Twice daily | 301 (75.2%) | |

| Use of mouth wash | Yes | 48 (12%) |

| No | 352 (88%) | |

| Previous dental Visit | Less than 6 months | 53 (13.2%) |

| More than 6 months | 228 (57%) | |

| Never | 119 (29.8%) | |

| Dietary Practices | ||

| Dietary Pattern | Vegetarian | 47 (11.8%) |

| Non Vegetarian | 355 (88.2%) | |

| Diet preference during pregnancy | Sweet | 68 (17%) |

| Fizzy drink | 23 (5.8%) | |

| Spicy | 84 (21%) | |

| Sour | 70 (17.5%) | |

| None | 155 (38.8%) | |

| Advised to avoid any food | Yes | 243 (60.8%) |

| No | 157 (39.2%) | |

| Total | 400 (100%) | |

Majority of study subjects had no diet preferences, whereas 85.8% of them were willing to change to a healthy diet. Craving for spicy, sour and sweet diet were reported by 61.2% of them while 60.8% of the participants were advised by the elderly in the family to avoid certain food items [Table 3b]. Participants from the upper middle class (OR - 2.8) who had visited dentists within the last 6 months (OR - 3.6) and child bearing mothers (OR- 0.46) had better awareness on oral health (p ≤ 0. 05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparing knowledge with gravida status, SES, Previous dental visit, Willingness for dental treatment during pregnancy

| knowledge | p | Adjusted Odds Ratio | |||

| poor knowledge | good knowledge | ||||

| Socio Economic status | Upper Middle class (n=58) | 36 (62.1%) | 22 (37.9%) | 0.025* | 2.8* |

| Lower Middle class (n=90) | 67 (74.4%) | 23 (25.6%) | 1.4 | ||

| Lower class (n=252) | 199 (79%) | 53 (21%) | 1 | ||

| Parity | Nulliparous (n=229) | 186 (81.2%) | 43 (18.8%) | 0.002* | 0.46* |

| Primi/multiparous (n=171) | 116 (67.8%) | 55 (32.2%) | 1 | ||

| Previous dental visit | Less than 6 months (n=53) | 35 (66%) | 18 (34%) | 0.001* | 4.1* |

| More than 6 months (n=228) | 161 (70.6%) | 67 (29.4%) | 3.6* | ||

| Never (n=119) | 106 (89%) | 13 (10.9%) | 1 | ||

| Willingness for dental treatment | Yes (n=182) | 133 (73.1%) | 49 (26.9%) | 0.015* | 2.1* |

| during pregnancy | No (n=122) | 86 (70.5%) | 36 (29.5%) | 2.4* | |

| Not sure (n=96) | 83 (86.5%) | 13 (13.5%) | 1 | ||

| TOTAL | 302 (75.5%) | 98 (24.5%) | |||

Discussion

Kerala, the southernmost Indian state with the highest human development index, has acquired good overall health indicators well ahead of other states in the country.[13] Being the most literate state with high female literacy rate, the present study shows more than three-fourth of the study population had poor oral health knowledge similar to the studies done by Leelavathi et al. and Sedky N A.[14,15]

According to Barbieri W et al., socioeconomic status is known to influence health awareness, wherein greater social deprivation tend to have lower responsiveness and higher magnitude of inequalities.[16] A good oral health knowledge was seen among the upper middle-class mothers (OR - 2.8), however oral health awareness did not show any improvement irrespective of the level of education. Proportion of those who had utilized the dental services within six months and child bearing mothers showed a better oral health knowledge in our study (OR– 0.46). The nurturing/parenting experiences could have made them competent to perceive good oral health knowledge. Antenatal mothers reported poor knowledge about deciduous teeth as they believed that caring for the primary teeth is unimportant, as it will eventually shed off.[14,15]

Al-Swuailem AS et al. conducted a study in Saudi Arabia where they found that pregnant mothers had greater dental need than common populace of the same age group, whereby 72% of the sampled antenatal mothers experienced at least one dental problem which might need a dental intervention.[17] Furthermore, a similar experience was noted in the present study among 63.2% of the participants, suggesting a greater treatment need.

The most common self-reported problem was tooth ache whereas oral clinical examination recorded a high prevalence of dental caries, similar to the findings concluded by Norkhafizah Sedki in Malaysia.[15] Frequent snacking of refined carbohydrates and delay in dental treatment could be the reason for high prevalence of untreated dental caries.

The prevalence of gingival bleeding was low and was contrary to an Australian study by A George et al. with high gingival problems.[18] This could be because of proper oral hygiene measures as observed in our study. However some antenatal mothers experienced nausea and vomiting which are normal physiological changes.[19] Nausea and vomiting aggravated while using toothbrush and they were unaware of any appropriate measures to maintain their oral hygiene.

Traditional beliefs and cultural practices are common in India.[20] The elderly in the family normally influence the decision making with regard to health care and household activities.[21] The antenatal mothers were often advised by the elderly to restrict certain food items like dates, papaya, pineapple and coffee to ensure safe motherhood. Anecdotal evidence shows that common dental problems did not affect the routine activities and strong cultural and family influences might be the reason why some of the antenatal mothers were reluctant to utilize the dental services. Other reasons for the low utilization could be lack of emphasis from their antenatal care providers, fear that the treatment can be harmful to the fetus and financial burden.[22]

Conclusion

Antenatal mothers are a special group that need specialized oral care and monitoring. There is a need to bring out oral health awareness among the antenatal care givers and encourage their patients for regular oral health services. Early prevention and prompt intervention can be achieved by integrating oral health programs in the existing national antenatal care programs. This can ensure a desirable healthy motherhood.

Key points

Poor oral health knowledge was observed among 75.5% of the pregnant mothers

Low priority for oral health (59.4%) and fear for foetal safety (17.5%) were the reasons for delaying dental services.

Combined and coordinated preventive antenatal oral health care approaches by the dentists and the physicians are important for a healthy motherhood.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support from Dr C.P Vijayan, Professor & Head, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Government Medical College, Kottayam.

References

- 1.Olak J, Nguyen MS, Nguyen TT, Nguyen BBT, Saag M. The influence of mothers' oral health behaviour and perception thereof on the dental health of their children. EPMA J. 2018;9:187–93. doi: 10.1007/s13167-018-0134-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong X, Buekens P, Fraser WD, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review. BJOG. 2006;113:135–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virtanen JI, Vehkalahti KI, Vehkalahti MM. Oral health behaviors and bacterial transmission from mother to child: An explorative study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:75. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olatona FA, Onabanjo OO, Ugbaja RN, Nnoaham KE, Adelekan DA. Dietary habits and metabolic risk factors for non-communicable diseases in a university undergraduate population. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37:21. doi: 10.1186/s41043-018-0152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moynihan P, Petersen PE. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:201–26. doi: 10.1079/phn2003589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oral health care during pregnancy and through the life span. Committee opinion number 569. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):417–22. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000433007.16843.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocha JS, Arima L, Chibinski AC, Werneck RI, Moysés SJ, Baldani MH. Barriers and facilitators to dental care during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Cadernos de Saúe Pública. 2018;34:e00130817. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00130817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal A, Chaturvedi J, Seth J, Mehta R. Cognizance & oral health status among pregnant females- A cross sectional survey. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020;10:393–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Aga Khan University and SZABIST. Sattar FA, Khan AH. Prenatal Oral health care and dental service utilization by pregnant women: A survey in four maternity centers of Gulshan Town, District East, Karachi. J Pak Dent Assoc. 2020;29:60–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakhshi M, Tofangchiha M, Bakhtiari S, Ahadiyan T. Oral and dental care during pregnancy: A survey of knowledge and practice in 380 Iranian gynaecologists. J Int Oral Health. 2019;11:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikh Z, Pathak R. Revised Kuppuswamy and B G Prasad socio-economic scales for 2016. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4:997–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHP 2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leelavathi L, Merlin TH, Ramani V, Suja RA, Chandran CR. Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to the oral health among the pregnant women attending a government hospital, Chennai. Int J Community Dent. 2018;6:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedky NA. Pereira R, editor. Assessment of knowledge, perception, attitude, and practices of expectant and lactating mothers regarding their own as well as their infants' oral health in Qassim Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Contemp Dent. 2016;6:24–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbieri W, Peres SV, Pereira C de B, Peres Neto J, Sousa M da LR de, Cortellazzi KL. Sociodemographic factors associated with pregnant women's level of knowledge about oral health. Einstein (Sã Paulo) 2018;16:eAO4079. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082018AO4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Swuailem AS, Al-Jamal FS, Helmi MF. Treatment perception and utilization of dental services during pregnancy among sampled women in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Dent Res. 2014;5:123–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.George A, Johnson M, Blinkhorn A, Ajwani S, Bhole S, Yeo AE, et al. The oral health status, practices and knowledge of pregnant women in south-western Sydney. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:26–33. doi: 10.1111/adj.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinlan JD, Hill DA. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar M, Kumar A. Elderly decision making autonomy at household level: An empirical study in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. Int J Dev Res. 2017;7:5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upadhyay P, Liabsuetrakul T, Shrestha AB, Pradhan N. Influence of family members on utilization of maternal health care services among teen and adult pregnant women in Kathmandu, Nepal: A cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2014;11:92. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalaf SA, Osman SR, Abbas AM, Ismail TA-AM. Knowledge, attitude and practice of oral healthcare among pregnant women in Assiut. Egypt Int J Community Med Publ Health. 2018;5:890. [Google Scholar]