Abstract

Background:

In April 2018, the Government of India launched 'Nikshay Poshan Yojana' (NPY), a cash assistance scheme (500 Indian rupees [~8 USD] per month) intended to provide nutritional support and improve treatment outcomes among tuberculosis (TB) patients.

Objective:

To compare the treatment outcomes of HIV-infected TB patients initiated on first-line anti-TB treatment in five selected districts of Karnataka, India before (April–September 2017) and after (April–September 2018) implementation of NPY.

Methods:

This was a cohort study using secondary data routinely collected by the national TB and HIV programmes.

Results:

A total of 630 patients were initiated on ATT before NPY and 591 patients after NPY implementation. Of the latter, 464 (78.5%, 95% CI: 75.0%–81.8%) received at least one installment of cash incentive. Among those received, the median (inter-quartile range) duration between treatment initiation and receipt of first installment was 74 days (41–165) and only 16% received within the first month of treatment. In 117 (25.2%) patients, the first installment was received after declaration of their treatment outcome. Treatment success (cured and treatment completed) in 'before NPY' cohort was 69.2% (95% CI: 65.6%–72.8%), while it was 65.0% (95% CI: 61.2%–68.8%) in 'after NPY' cohort. On adjusted analysis using modified Poisson regression we did not find a statistically significant association between NPY and unsuccessful treatment outcomes (adjusted relative risk-1.1, 95% CI: 0.9–1.3).

Conclusion:

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous evidence from systematic reviews, we did not find an association between NPY and improved treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Cash incentives, conditional cash transfer, Direct Benefit Transfer, monetary incentives, Operational Research, SORT IT

Background

Globally, tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, ranking above HIV/AIDS. Though there has been a global decline in the TB burden over the last two decades, the disease remains a major public health problem of concern, disproportionately affecting the poor people in the LMICs.[1] India with an estimated 2.7 million new TB patients in 2017, accounted for about one-fourth of the global TB incidence.[1,2]

The World Health Organization's (WHO) End TB strategy and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have set a goal of ending TB epidemic by 2030.[3,4] One of the three targets of End TB Strategy is to achieve 'zero catastrophic costs for tuberculosis-affected families' by 2020.[3] Achieving this target is crucial in the context of ending TB as the catastrophic expenditures during the TB treatment can further push the families into poverty and thus make them prone for TB again.

A systematic review in 2015 reported that, patients and affected families spend more than half of their yearly income towards TB care in LMICs.[5] The mere provision of free treatment in majority of these countries doesn't guarantee the financial protection as economic burden during disease is largely contributed by wage loss (60%) and non-medical expenses (20%).[5,6,7] So, the End TB strategy recommends countries to improve access to quality TB care services and 'social protection' schemes to cover the expenditures beyond direct medical costs. The social protection includes sickness insurance, disability grants, conditional or unconditional cash transfer, and food assistance during the period of disease. Systematic reviews show that cash incentives are beneficial in improving the treatment adherence and treatment success rate.[8,9,10]

In line with the End TB strategy, the National Strategic Plan (NSP) for TB elimination in India (2017–2025) proposed providing monetary support to TB patients.[11] In March 2018, the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) of India launched 'Nikshay Poshan Yojana' (NPY), a cash assistance scheme to support TB patients during treatment.[12] Under NPY, all notified TB patients are eligible to receive a cash incentive of 500 Indian rupees (~8 USD) per month. This money is transferred directly into the bank account of patients to avoid pilferage and delays in fund disbursement. Thus, having a bank account and getting notified in 'Nikshay' (an online TB notification portal) are pre-requisites for TB patients to avail NPY benefits.

Along with social protection and nutritional support, the main focus of the NPY is to help the TB patients to complete their treatment. While the overall global evidence in research settings is in favor of cash transfers to improve TB treatment outcomes, this is the first time a cash transfer scheme is being implemented at such a large scale in programmatic settings. As of date, there are no systematic assessments yet of the effect of NPY on the treatment outcomes. If NPY is beneficial, the treatment success rates should improve in the TB patient cohorts post NPY implementation compared to previous cohorts.

HIV-infected TB patients are a vulnerable group of patients with relatively lower treatment success rate compared to HIV-negative patients.[13,14] Under the NPY, HIV-infected TB patients are expected to be preferentially covered.

Hence, we aimed to describe and compare the programmatic TB treatment outcomes of HIV-infected TB patients initiated on first-line anti-TB treatment (ATT) in the selected districts of Karnataka, India before (April–September 2017) and after (April–September 2018) implementation of NPY.

Methods

Study design

This is a cohort study using secondary data collected by the National AIDS Control Programme, Public Financial Management System and the National TB programme in India.

Study setting

General setting

Karnataka is a southern state of India with a population of 66.8 million.[15] In 2016, it was estimated that the state had 0.1 million TB patients.[16] The state is one of the high TB/HIV burden states in the country with about 11% of the TB patients co-infected with HIV during 2015.[17] The care and support services for PLHIV are provided through 64 anti-retroviral therapy (ART) centers spread across the state.

Specific setting

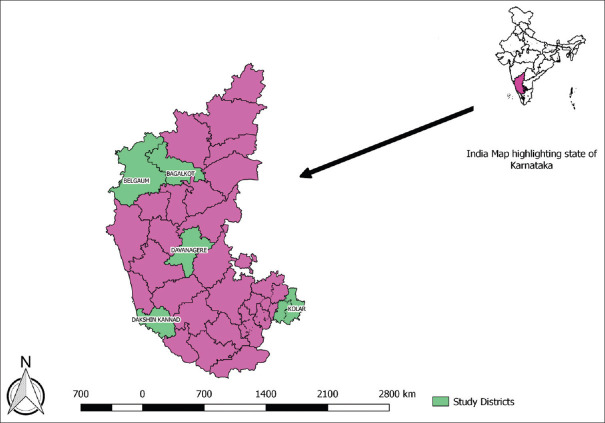

This study was carried out in five selected districts of Karnataka State, India. The Belgaum and Bagalkot represent Mumbai-Karnataka, Davanagere represents central-Karnataka, Dakshina Kannada represents coastal-Karnataka and Kolar represents south-Karnataka. The map of Karnataka State with selected districts is shown in [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Map of study districts in the state of Karnataka, India

Treatment of TB among PLHIV

PLHIV diagnosed with drug-sensitive TB are registered and initiated on ATT at ART centers. The fixed dose combination (FDC) drugs are dispensed once a month and the patients are advised to consume drugs daily. During the study period, the newly diagnosed TB patients received two months of intensive phase (2HRZE: H = Isoniazid, R = Rifampicin, P = Pyrazinamide, E = Ethambutol) and four months of continuation phase (4HRE), whereas previously treated patients received three months of intensive phase (2HRZES + 1HRZE; S = Streptomycin) and five months of continuation phase (5HRE).

Under single window system, patients are given both ATT and ART drugs at the ART centers during their monthly visits. The various adherence support mechanisms like 99DOTS, directly observed treatment (DOT) and family DOT are offered to patient based on availability of mobile phone and family support. The 99DOTS is an information communication technology (ICT) enabled adherence support mechanism which uses mobile phones to monitor and improve adherence to TB drugs. In DOT and family DOT, the drugs are consumed directly under the supervision of community health workers/volunteers and family member, respectively. Some patients opt for self-administered treatment (SAT) and in such cases the ART staff assesses the adherence to ATT through monthly pill count during the follow-up visit. The treatment outcomes of the HIV-infected TB patients are ascertained by the ART Medical Officer as per RNTCP guidelines [Supplementary Table 1].

Supplementary Table 1.

Programmatic Outcomes of Tuberculosis treatment among TB-HIV co-infected patients treated under Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP).

| Programmatic Outcomes | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cured | ATB patient who was microbiologically confirmed for TB at the beginning of treatment but who is smear or culture negative at the end of complete treatment |

| Treatment completed | A TB patient who completed treatment without evidence of failure or clinical deterioration BUT with no record to show that the smear or culture results of biological specimen in the last month of treatment was negative, either because the test was not done or because the result is unavailable |

| Treatment success | TB patients either cured or treatment completed are accounted in treatment success |

| Failure | A TB patient whose biological specimen is positive by smear or culture at the end of treatment |

| Failure to Respond: A child of paediatric TB who fails to have bacteriological conversion to negative status or fails to respond clinically/or deteriorates after 12 weeks of completion of intensive phase shall be deemed to have failed response, provided alternative diagnoses/reasons for non-response have been ruled out | |

| Lost to follow up (LFU) | ATB patient whose treatment was interrupted for one consecutive month or more |

| Not evaluated | A TB patient for whom no treatment outcome is assigned; this includes former ‘transfer-out’ patients |

| Treatment regimen changed | ATB patient who is on first line regimen and has been diagnosed as having DR-TB and switched to drug resistant TB regimen prior to being declared as failed |

| Died | A patient who has died during the course of anti-TB treatment |

Cash incentives through NPY scheme

All the HIV-infected TB patients receiving ATT as on 1 April 2018 or after are eligible for cash incentive through NPY. The bank details of the patients are collected by the ART staff nurse or TB health visitor (TB-HV) and entered in an online TB notification portal called 'Nikshay'. In case the patient does not have a bank account, one of the family member's account is considered, while the patients are encouraged to open a bank account.

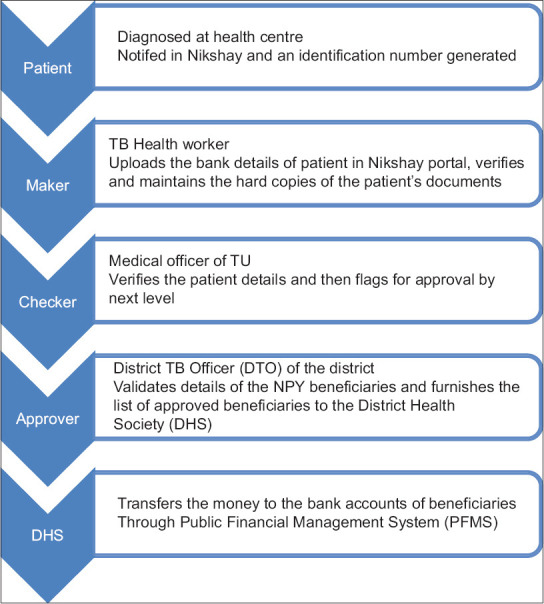

The bank account details are checked and verified at three levels viz. maker, checker and the approver. Maker is the data entry operator at the peripheral health institution or the tuberculosis unit (TU) who will upload all the details of patient in Nikshay portal, verify, and maintain the hard copies of the patient's documents. Checker is the medical officer of the TU, who verifies the patient details and flags for approval by the next level. District TB Officer (DTO) of the district is the approver who further validates all the details of the NPY beneficiary in Nikshay portal and forwards the approved list of beneficiaries to the District Health Society (DHS). Then, DHS transfers the money into the bank accounts of beneficiaries through Public Financial Management System (PFMS). The first installment of 1000 INR for first two months is expected to be disbursed immediately after starting treatment. The subsequent installments (@ 1000 INR for every two months) are disbursed only if the patient has completed the two months of treatment. In case of delays in disbursement, patients received the total money they were eligible to receive till that time. For example, if the first disbursement was after 4 months of treatment, then the patients received a total of INR 2000 at once [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Process of approval and disbursement of funds to TB patients under ‘Nikshay Poshan Yojana’ in India, 2018

Registers and reporting:

The TB-HIV register containing details of both TB and HIV treatment of all HIV-infected TB patients is maintained in the ART center. The electronic format of the TB-HIV register is available at the respective TUs. This is shared between the TB and HIV programme personnel and is regularly updated.

Study population

All HIV-infected TB patients initiated on first-line ATT and notified in Nikshay before (April to September, 2017) and after (April to September, 2018) implementation of NPY in five selected districts of Karnataka were included in the study.

Data variables, sources of data, and data collection

Data on socio-demographic and morbidity related factors like Nikshay identification number, age, gender, name of the tuberculosis unit (TU, a sub-district level management unit), history of TB treatment, date of initiation of TB treatment, ART regimen used, adherence support, ART status, latest CD4 cell count, date of TB treatment outcome, TB treatment outcomes were extracted from electronic TB/HIV treatment register.

For all study participants initiated on TB treatment after implementation of NPY, the receipt of NPY, date of disbursement of first installment of NPY, number of installments of NPY received during treatment and the total amount of money received were extracted from the PFMS web database censored on 31 May 2019. Nikshay identification number was used as unique identifier to extract the required details from PFMS web database.

Data entry and analysis

The electronic TB/HIV databases obtained from each district was compiled using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using Stata (version 12.0, Statacorp, Texas, USA). Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized as percentages and compared between two study groups using Chi-square test.

Among the NPY cohort, the proportion who received at least one installment of cash incentive was summarized as percentages with 95% confidence interval (CI). The duration between treatment initiation and disbursement of first installment of cash incentives, and total amount disbursed to each patient was summarized using median and inter-quartile range.

TB treatment outcomes were categorized into successful (cured, treatment completed and on treatment) and unsuccessful (failure, lost to follow up, died, switched to second-line treatment, not evaluated) outcomes. The proportion of successful treatment outcomes were summarized as percentages and compared across the two groups using Chi-square test.

To assess the independent effect of NPY on TB treatment outcomes, a modified Poisson regression model adjusted for clustering at TU level and known confounders (age, sex, site, history of TB treatment, adherence support type, CD4 cell count, ART status) was used. The magnitude of association was expressed using adjusted relative risk (aRR) with 95% CI.

Ethics

Permission to access data was obtained from the State tuberculosis programme office. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France and IEC, JJM Medical College, Davanagere.

Results

Of the 1221 participants included in this study, 630 were initiated on ATT before NPY and 591 after NPY implementation. The comparison of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics is shown in [Table 1]. There was no difference in the distribution of age, gender, category of TB treatment, and CD4 count between the study groups. Those in the after NPY group had higher proportion of extra pulmonary TB (54.7% vs 47.8%, P < 0.001) and were more likely to receive daily ATT regimen (93.3% vs 90.5%, P < 0.001) compared to before NPY group. The ART initiation rate (90.5% vs 94.8%, P < 0.001) was lower in after NPY group.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of HIV-infected TB patients initiated on TB treatment before (April-September, 2017) and after (April-September, 2018) after roll out of NPY in selected districts of Karnataka

| Characteristics | Before NPY, n (%) | After NPY, n (%) | p† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 630 (100) | 591 (100) | |

| Age in years | |||

| <15 | 14 (2.2) | 14 (2.4) | 0.116 |

| 15-24 | 38 (6.0) | 45 (7.6) | |

| 25-34 | 116 (18.4) | 129 (21.8) | |

| 35-44 | 265 (42.1) | 240 (40.6) | |

| 45-54 | 142 (22.5) | 107 (18.1) | |

| 55-64 | 36 (5.7) | 46 (7.8) | |

| 65 and above | 19 (3.0) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 398 (63.2) | 366 (61.9) | 0.653 |

| Female | 232 (36.8) | 225 (38.1) | |

| District | |||

| Belgaum | 313 (49.7) | 240 (40.6) | 0.028 |

| Bagalkot | 218 (34.6) | 232 (39.3) | |

| Davanagere | 32 (5.1) | 37 (6.3) | |

| Kolar | 43 (6.8) | 27 (4.6) | |

| Dakshina Kannada | 24 (3.8) | 55 (9.3) | |

| Site of TB | |||

| Pulmonary TB | 329 (52.2) | 268 (45.4) | 0.016 |

| Extra Pulmonary TB | 301 (47.8) | 323 (54.7) | |

| Category of TB Treatment | |||

| New | 526 (83.5) | 503 (85.1) | 0.729 |

| Previously treated | 93 (14.8) | 78 (13.2) | |

| Not recorded | 11 (1.7) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Adherence support | |||

| 99 DOTS | 591 (93.8) | 329 (55.7) | <0.001 |

| DOTS | 25 (4.0) | 235 (39.8) | |

| Family DOT | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.7) | |

| SAT | 14 (2.2) | 23 (3.9) | |

| ART status | |||

| On ART | 597 (94.8) | 534 (90.5) | 0.004 |

| Not on ART | 33 (5.2) | 56 (9.5) | |

| CD4 categories (cells/mm3) | |||

| <50 | 37 (5.9) | 23 (3.9) | 0.095 |

| 50-200 | 154 (24.4) | 144 (24.4) | |

| 200-350 | 97 (15.4) | 79 (13.4) | |

| 350-500 | 54 (8.6) | 40 (6.8) | |

| More than 500 | 44 (7.0) | 33 (5.6) | |

| Not available | 244 (38.7) | 272 (46.0) | |

| CD4 count (Median (IQR))# | 201 (92-351) | 192 (105-332) | 0.923 |

*Column Percentage, † Chi-square test, # Mann Whitney Test. HIV- Human Immunodeficiency Virus; TB- Tuberculosis; NPY- Nikshay PoshanYojana; ART- Antiretroviral Therapy; CD4- Cluster of Differentiation 4/ CD4+ T helper cells; DOT- Direct observation of treatment; SAT-Self-administered treatment; IQR-Inter quartile range

Of the 591 patients in after NPY group, 464 (78.5%, 95% CI- 75.0%–81.8%) received at least one installment of cash incentive. Among those received, the median (IQR) duration between treatment initiation and receipt of first installment was 74 days (41–165). In 117 (25.2%) patients, the first installment was received after ascertainment of their treatment outcome. The median (IQR) total amount received by the patient was INR 3000 (2500–3000). The details of cash incentives received are shown in [Table 2].

Table 2.

Details of direct cash incentive under NPY among HIV -infected TB patients initiated on TB treatment during April to September, 2018 in selected districts of Karnataka, India, n=591

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| First installment of cash incentive | |

| Received | 464 (78.5) |

| Not received | 127 (21.5) |

| Duration between treatment initiation and receipt of 1st installment, Median (IQR)* | 74 (41-165) |

| Month of receipt after treatment initiation* | |

| 1st | 75 (16.1) |

| 2nd | 112 (24.1) |

| 3rd | 76 (16.4) |

| 4th | 33 (7.1) |

| 5th | 26 (5.6) |

| 6th | 27 (5.8) |

| >6th | 95 (20.5) |

| Missing | 20 (4.3) |

| Receipt of 1st installment after outcome of treatment* | |

| No | 327 (70.5) |

| Yes | 117 (25.2) |

| Missing | 20 (4.3) |

| Total amount received in INR, Median (IQR)* | 3000 (2500-3000) |

* Applicable only to 464 patients those who received at least one installment of cash incentive. HIV- Human Immunodeficiency Virus; TB- Tuberculosis; NPY- Nikshay PoshanYojana; IQR-Inter quartile range

The TB treatment outcomes are summarized in [Table 3]. Treatment success in 'before NPY' cohort was 69.2% (95% CI - 65.6%-72.8%), while it was 65.0% (95% CI - 61.2%–68.8%) in 'after NPY' cohort. There was no statistically significant difference between two groups in terms of successful treatment outcomes (69.2% vs 65.0%, P = 0.116), loss to follow-up (5.4% vs 4.6%, P = 0.522) and death (20.8% vs 19.8%, P = 0.664). We performed post-hoc power calculations assuming 5% improvement in treatment success among NPY group and 70% treatment success in the 'before NPY' group. This showed that our study had a power of 50%.

Table 3.

Comparison of TB treatment outcomes among HIV-infected TB patients initiated on TB treatment before (April-September, 2017) and after (April- September, 2018) after roll out of NPY in selected districts of Karnataka

| TB treatment Outcome | Before NPY, n=630, n (%)* | After start of NPY, n=591, n (%)* | p# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful | 436 (69.2) | 384 (65.0) | 0.116 |

| Cured | 88 (14.0) | 129 (21.8) | <0.001 |

| Treatment Completed | 348 (58.4) | 248 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| On treatment | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.9) | - |

| Unsuccessful | 194 (30.8) | 207 (35.0) | 0.116 |

| Failure | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | 0.579 |

| Lost to follow up | 34 (5.4) | 27 (4.6) | 0.522 |

| Died | 131 (20.8) | 117 (19.8) | 0.664 |

| Shift to second-line treatment | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0.727 |

| Not evaluated | 25 (4.0) | 59 (10.0) | <0.001 |

* Percentage calculated with total number of individuals in each group as denominator. # Chi-square test. Abbreviation: HIV- Human Immunodeficiency Virus; TB- Tuberculosis; NPY- Nikshay PoshanYojana

On adjusted analysis, we did not find a statistically significant association between NPY and unsuccessful treatment outcomes (aRR-1.1, 95% CI-0.9-1.3) [Supplementary Table 2].

Supplementary Table 2.

Association of demographic, clinical and NPY implementation with unsuccessful outcomes among HIV-infected TB patients initiated on TB treatment before (April- September, 2017) and after (April-September, 2018) after roll out of NPY in selected districts of Karnataka

| Characteristic | Total | Unsuccessful outcome, n (%)* | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)# | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1221 | 401 (32.8) | |||

| Age (in years) | |||||

| 1-14 | 28 | 7 (25) | 1 | 1 | |

| 15-24 | 83 | 22 (26.5) | 1.1 (0.5-2.2) | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.717 |

| 25-34 | 245 | 81 (33.1) | 1.3 (0.7-2.6) | 1.2 (0.6-2.1) | 0.593 |

| 35-44 | 505 | 156 (30.9) | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 0.857 |

| 45-54 | 249 | 85 (34.1) | 1.4 (0.7-2.7) | 1.2 (0.6-2.0) | 0.631 |

| 55-64 | 82 | 34 (41.4) | 1.7 (0.8-3.3) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 0.276 |

| 65 and above | 29 | 16 (4) | 2.2 (1.1-4.5) | 1.7 (0.8-3.6) | 0.131 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 764 | 265 (34.7) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 0.244 |

| Female | 457 | 136 (29.8) | 1 | ||

| Site of TB | |||||

| Pulmonary TB | 597 | 193 (32.3) | 1 | ||

| Extra Pulmonary TB | 624 | 208 (33.3) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 0.009 |

| Category of Treatment | |||||

| Cat 1 | 1029 | 323 (31.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| Cat 2 | 121 | 63 (36.8) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 0.123 |

| Not recorded | 21 | 15 (71.4) | 2.3 (1.7-3.0) | 2.2 (1.6-3.1) | <0.001 |

| Treatment type | |||||

| Intermittent | 43 | 12 (28) | 1 | ||

| Daily | 1178 | 389 (33) | 1.2 (1-1.3) | 0.9 (0.4-2.2) | 0.840 |

| Adherence support | |||||

| 99 DOTS | 920 | 279 (30.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| DOTS | 264 | 105 (39.8) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.1 (0.8-1.7) | 0.489 |

| SAT | 37 | 17 (46.0) | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.550 |

| District | |||||

| Davanagere | 69 | 35 (50.7) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | 0.386 |

| Belgaum | 553 | 157 (28.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| Bagalkot | 450 | 169 (37.6) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 0.847 |

| Kolar | 98 | 28 (28.6) | 1.0 (0.7- 1.4) | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | 0.635 |

| Dakshina Kannada | 51 | 12 (23.5) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 0.669 |

| ART status | |||||

| On ART | 1131 | 350 (31.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Not on ART | 89 | 50 (56.2) | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) | 0.103 |

| CD4 categories | |||||

| Less than 50 | 60 | 32 (53.3) | 3.4 (1.9-6.1) | 3.1 (2.1-4.5) | <0.001 |

| 50-200 | 298 | 92 (30.9) | 2.0 (1.1- 3.4) | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) | 0.002 |

| 200-350 | 176 | 36 (20.5) | 1.3 (0.7-3.4) | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | 0.508 |

| 350-500 | 94 | 27 (28.7) | 1.8 (1.0- 3.4) | 1.8 (0.9-3.6) | 0.107 |

| More than 500 | 77 | 12 (15.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| Not available | 51 | 20 (39.1) | 2.5 (1.5-4.3) | 1.9 (1.0-3.7) | 0.058 |

| NPY roll out | |||||

| After (April-September,2018) | 591 | 207 (35.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Before (April-September,2017) | 630 | 194 (30.8) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 0.552 |

*Row percentage. #Model adjusted for clustering at 45 Tuberculosis Units included in the study. HIV- Human Immunodeficiency Virus; TB- Tuberculosis; NPY- Nikshay Poshan Yojana; RR- Relative Risk; CI- Confidence Interval; ART- Antiretroviral Therapy; CD4- Cluster of Differentiation 4/ CD4+ T helper cells; DOT- Direct observation of treatment; SAT-Self-administered treatment

Discussion

Several cash transfer schemes have been implemented in India in the past outside of health field for education, pension, nutrition, providing fuel subsidies, and so on.[18] In the health field, this has been implemented to promote maternal and child health and improve institutional deliveries and mostly moderated by the primary care physicians.[19] This is the first time a TB-specific approach is being implemented in India and it is the largest cash assistance programme ever-implemented among TB patients under programmatic conditions. Our study is the first effort to evaluate the impact of NPY on treatment outcomes. We discuss the key findings below.

The NPY coverage was relatively high at 80%, compared to a previous study from Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka State, where only 29% of the patients received the money.[20] This may be due to the differences in study population. While our study included only HIV-infected TB patients, the previous study included all TB patients. While NPY guidelines do not make any special provisions for HIV-infected TB patients, they might have been accorded a greater priority by the health system, given that they are sick patients and at a high risk of death.

Nevertheless it is a concern that about one in five patients failed to receive NPY and this might be due to reasons such as lack of bank account or lack of awareness about the scheme. A previous study from Peru reported several challenges which included unwillingness of TB patients to reveal their bank account details, displeasure about insufficient incentives and dislike for home visits by health workers.[21] We do not know if these factors played a role in our setting and needs further study.

There were gross delays in disbursing the money with nearly 25% of the patients receiving the money after treatment outcomes have occurred. While we did not study the exact reasons in our study, we speculate that may be due to the complexities of the process requiring multiple levels of checks and approvals. Previous studies have also alluded to technology related challenges like poor phone and internet connectivity, which are essential for smooth functioning of web-based applications such as Nikshay and PFMS.[20]

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous evidence from systematic reviews, we failed to demonstrate an association between NPY and improved treatment outcomes.[10] This may be due to many reasons including suboptimal implementation of NPY. As discussed above, many patients did not receive NPY and there were long delays among those who received. This meant that the money could not be used by the patients during the course of TB treatment, when it would have mattered. One of the pathways through which NPY is expected to make an impact on treatment outcomes is by improving the nutritional status of TB patients. We are not sure if the money received was indeed used by the patients for the purpose intended and needs to be studied further. Finally, we were statistically underpowered (owing to low sample size) to demonstrate an improvement of 5% treatment success, if it existed. This was an important limitation.

Our study had some strengths. We included patients from five districts of Karnataka State representing the different administrative regions of the state. Thus, we feel the findings are representative of the situation in the state. We used routine programme data for this analysis and hence the findings are reflective of the ground realities. We adhered to STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for reporting the study.[22]

We had some limitations too. One was related to sample size as mentioned above. We recommend that the study be repeated with larger sample size, once NPY processes are streamlined and the delays in cash transfers are reduced. This may help us assess if NPY is able to improve treatment outcomes. We did not try to systematically understand the reasons for non-receipt and delay in cash transfers in this study. This requires future study using qualitative research methods. Although not statistically significant, the treatment success in 'after NPY' cohort seems lower compared to 'pre NPY' cohort. This is due to higher proportion of 'not evaluated' in the 'after NPY' group, which may have underestimated the treatment success. Re-analyzing after exclusion of 'not evaluated' from the both the cohorts, we find similar treatment success rates (~71% in each group).

In conclusion, we did not find any association between NPY and improved treatment outcomes among HIV-infected TB patients in Karnataka State, India. This might be due to gaps and delays in cash transfers and low sample size. The TB and HIV programmes must take measures to address these gaps and reduce the delays. One simple measure could be to begin documenting the reasons for non-receipt of money and delays in Nikshay. Another measure could be to intensify monitoring and review of NPY on priority at district, state and national level review meetings. These will enable real-time monitoring and instituting course corrective measures. We also recommend that the research be repeated with a larger sample once NPY processes become more efficient.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any competing interest

Ethics and Consent

Permission to access data was obtained from the State tuberculosis programme office. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France (EAG number: 91/18 dated 10-10-2018) and IEC, JJM Medical College, Davanagere (JJMC/IEC-43-2018 dated 18-12-2018).

Financial support and sponsorship

The training program, within which this article was developed, and the open access publication costs were funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), UK, and La Fondation Veuve Emile Metz-Tesch (Luxembourg). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) and Medécins sans Frontières (MSF/Doctors Without Borders). The specific SORT IT programme which resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by: The Union South-East Asia Office, New Delhi, India; the Centre for Operational Research, The Union, Paris, France; Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India; Deartment of Community Medicine and School of Public Health, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India; Department of Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur, India; Dr. Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India; Department of Community Medicine, Pondicherry Institute of Medical Science, Puducherry, India; Department of Community Medicine, Kalpana Chawla Medical College, Karnal, India; National Centre of Excellence and Advance Research on Anemia Control, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India; Department of Community Medicine, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, Puducherry, India; Department of Community Medicine, Velammal Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, Madurai, India; Department of Community Medicine, Yenepoya Medical College, Mangalore, India; Karuna Trust, Bangalore, India and National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Chennai, India.

We are grateful to the District Tuberculosis Officers, District Program Coordinators, District Program Supervisors, Data entry operators and ART staff of study districts in state of Karnataka.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017 [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/tb/publications/global_report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Central TB Division. India TB Report 2017 Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme-Annual Status Report [Internet] New Delhi: 2017. Available from: https://tbcindiagovin/showfilephplid=3314 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/tb/End_TB_brochurepdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development [Internet] United Nations; 2015. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopmentunorg/content/documents/7891Transforming Our World pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurence YV, Griffiths UK, Vassall A. Costs to health services and the patient of treating tuberculosis: A systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:939–55. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lönnroth K, Glaziou P, Weil D, Floyd K, Uplekar M, Raviglione M. Beyond UHC: Monitoring health and social protection coverage in the context of tuberculosis care and prevention. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanimura T, Jaramillo E, Weil D, Raviglione M, Lönnroth K. Financial burden for tuberculosis patients in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Eur Resp J. 2014;43:1763–75. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00193413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alipanah N, Jarlsberg L, Miller C, Linh NN, Falzon D, Jaramillo E, et al. Adherence interventions and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials and observational studies. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutge EE, Wiysonge CS, Knight SE, Sinclair D, Volmink J. Incentives and enablers to improve adherence in tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD007952. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007952.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richterman A, Steer-Massaro J, Jarolimova J, Luong Nguyen LB, Werdenberg J, Ivers LC. Cash interventions to improve clinical outcomes for pulmonary tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:471–83. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.208959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Central TB Division. National Strategic plan for tuberculosis elimination 2017-2025 [Internet] New Delhi: 2017. Available from: https://tbcindiagovin/WriteReadData/NSP%20Draft%2020022017%201pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Nikshay Poshan Yojana :: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [Internet] New Delhi: Government of India; 2018. Available from: https://tbcindiagovin/showfilephplid=3317 . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waitt CJ, Squire SB. A systematic review of risk factors for death in adults during and after tuberculosis treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:871–85. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straetemans M, Glaziou P, Bierrenbach AL, Sismanidis C, van der Werf MJ. Assessing tuberculosis case fatality ratio: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. Provisional Population Totals Paper 1 of 2011 : Karnataka [Internet] Ministry of Home Affairs Government Of India. 2011. Available from: http://wwwcensusindiagovin/2011-prov-results/prov_data_products_karnatkahtml .

- 16.Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program. Tuberculosis in Karnataka [Internet] Health and Family Welfare, Government of Karnataka 2017 [cited 2020 May 4] Available from: http://wwwkarnatakagovin/hfw/nhm/pages/ndcp_cd_rntcpaspx .

- 17.National AIDS Control Organisation. Antiretroviral Therapy Guidelines for HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents [Internet] New Delhi: 2013. Available from: http://nacogovin/sites/default/files/Antiretroviral%20Therapy%20Guidelines%20for%20HIV-Infected%20Adults%20and%20Adolescents%20May%202013%281%29_0pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapra R, Divya Khatter D. Cash transfer schemes in India. ELK ASIA PACIFIC JOURNAL OF FINANCE AND RISK MANAGEMENT [Internet] 2014;5:1–6. cited 2020 May 4. Available from: https://wwwelkjournalscom/MasterAdmin/UploadFolder/6 CASH TRANSFER SCHEMES IN INDIA/6 CASH TRANSFER SCHEMES IN INDIApdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Janani Suraksha Yojana. [Internet] 2018. cited 2020 May 4. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=3&sublinkid=841&lid=309 .

- 20.Nirgude AS, Kumar AMV, Collins T, Naik PR, Parmar M, Tao L, et al. 'I am on treatment since 5 months but I have not received any money': Coverage, delays and implementation challenges of 'Direct Benefit Transfer' for tuberculosis patients-a mixed-methods study from South India. Glob Health Action. 2019;12:1633725. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1633725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wingfield T, Boccia D, Tovar MA, Huff D, Montoya R, Lewis JJ, et al. Designing and implementing a socioeconomic intervention to enhance TB control: Operational evidence from the CRESIPT project in Peru. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:810. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]