Abstract

Home support for patients receiving in-home palliative and end-of-life care (PELC) is greatly dependent on the daily presence of caregivers and their involvement in care delivery. However, the needs of caregivers throughout the care trajectory of a loved one receiving in-home PELC are still relatively unknown.

Objectives and methodology

This descriptive qualitative study focuses on the role of caregivers who have cared for a person receiving in-home PELC with the goal of describing their needs throughout the care trajectory. As part of this process, 20 caregivers took part in semi-directed interviews.

Results and discussion

This study sheds light on the multiple needs of caregivers of loved ones receiving in-home PELC. These informational, emotional, and psychosocial needs show that caregivers experience changes in their relationship with their loved one. Spiritual needs were expressed through the meaning ascribed to the home support experience. And the practical needs expressed by participants highlight the importance of round-the-clock access to PELC services and the essential importance of nursing support.

Conclusion

The needs of caregivers of loved ones receiving in-home PELC are not being met to a satisfactory degree. It is important to consider these needs in the care trajectory, alongside the needs of the patients themselves, in order to improve the support experience leading up to the bereavement period.

Keywords: transition, needs, caregivers, palliative and end-of-life care, nursing role

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (OMS/WHO, 2018) defines palliative care as an “approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” The aim of palliative care is to prevent and relieve suffering through the prompt assessment and prompt treatment of pain and its symptoms. In Quebec, the Act respecting end-of-life care ensures access to quality care that is appropriate to the needs of end-of-life patients, throughout the care trajectory, including prevention and relief of suffering (Légis Québec, 2018). The majority of people at the end of life indicate that they would prefer to die in the comfort of their home (SCC/CCS, 2013), circumstances permitting. However, as it currently stands, nearly 80% of deaths occur in a hospital environment (Statistics Canada, 2019b). In its 2015–2020 development plan concerning PELC, the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec (2015) prioritizes home support if this is what patients and their loved ones want.

However, home support is greatly dependent on the involvement of caregivers, i.e., those who assist a loved one with a significant and persistent disability that is likely to compromise their ability to continue living at home (L’Appui pour les proches aidants d’aînés, 2012). Many people report that they would have liked to provide in-home palliative and end-of-life care (PELC), but that constraints—particularly the lack of support and resources and the need to take time off work—prevented them from doing so (L’Appui pour les proches aidants d’aînés, 2012). The literature review shows that, to prepare for their role, caregivers need more information concerning their loved one’s illness, specifically as it pertains to the management of symptoms, the care to be provided (Funk et al., 2015) and the management and administration of medication (Wilson et al., 2018). To do this, caregivers need to be guided and informed by healthcare professionals (especially nurses) to reduce the anxiety related to the performance of these tasks (Sheehy-Skeffington et al., 2014). Many caregivers are present 24/7 to assume care responsibilities and perform the tasks of daily living (Robinson et al., 2017). This level of support generates a profound feeling of isolation and is a source of anxiety (Totman et al., 2015). In addition, caregivers report difficulty in adapting to changes in the relationship when the caregiver role becomes predominant, thus redefining the very nature of the relationship (Totman et al., 2015). Finally, caregivers express fears regarding the end-of-life process (Soroka et al., 2018) and recognize a lack of preparedness with respect to bereavement (Mason & Hodgkin, 2019).

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF THE STUDY

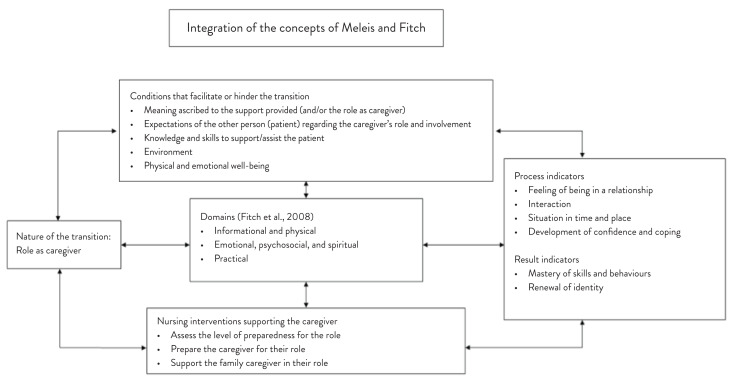

The conceptual framework that has been used to describe the needs associated with the experience of transitioning to the caregiver role is based primarily on the middle-range theory of transitions (Meleis, 2010) and the supportive care framework for cancer care (Fitch et al., 2008). Adapted to the concepts of the study, this framework provides a better understanding of the factors that facilitate or hinder the transition to the caregiver role and the identification of the resulting needs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Integration of the models of Meleis (2010) and Fitch et al. (2008)

For the purposes of this study, the transition is characterized by the shift from one role to another. The transition to the role of caregiver indicates a change in the relationship, the expectations related to the role, or the ability to assume the responsibilities related to the role (Meleis, 2010). This situational transition generally begins with the announcement of a serious illness and the appearance of symptoms, disrupting caregivers’ feeling of normality and balance (Penrod et al., 2012). Taking care of a person receiving in-home PELC gives rise to many challenges to which caregivers must adapt at the physical, informational, emotional, and psychological level, and well as socially and spiritually (Carlander et al., 2011).

PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

This descriptive qualitative study focuses on the role of caregivers who have provided support to a person receiving in-home palliative and end-of-life care (PELC). The objective is to describe the needs of caregivers caring for a dying loved one.

METHODOLOGY

This study is part of a broader research project entitled “Conditions favorisant et limitant le maintien à domicile en SPFV” [Conditions facilitating and hindering home support for PELC patients] (Hébert et al., 2017). It aims to outline the needs of people who have experienced the transition to the role of caregiver as a result of providing home support to a person receiving in-home PELC. The study takes a descriptive qualitative approach. To ensure transferability of the data, the sample was constituted of caregivers from two different backgrounds to represent rural and urban environments. The credibility and reliability of the study were ensured by triangulating the scientific and grey literature concerning in-home PELC with caregivers’ needs, as reported in the study. Moreover, the results could be compared with those of the main study for validation purposes. Finally, a validation exercise made it possible to ensure the confirmability of the results. During the initial step of the study, a student coded all the interview data. Then a table compiling all the coded transcripts and a separate table containing all the interview codes were created. A research professional and the research director then proceeded to code excerpts from the transcripts to check the codes and, thus, ensure the objectivity of data interpretation.

Participants and Procedure

A purposive sample was constructed. To be eligible, caregivers had to meet the following criteria: 1) be 18 years of age or older; and 2) have provided support to a loved one receiving in-home PELC services within the past two years. Semidirected interviews were conducted using an interview guide based on the conceptual framework of the main study (Fillion, Veillette, Wilson, Dumont, & Lavoie, 2009; Gomes & Higginson, 2006; Stewart, Teno, Patrick, & Lynn, 1999) and addressing the following themes: 1) the knowledge and perceptions associated with PELC; 2) the needs of people at the end of their life and the loved ones providing home support to them; and 3) the main challenges to be met to improve in-home PELC. Each of these themes included sub-questions that made it possible to explore the in-home PELC experience in more depth. An audio recording was made of the interviews, with the written agreement of the participants. The interviews were conducted at the participants’ homes so that they felt comfortable sharing their experience. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of an integrated health and social services centre (CISSS).

Data Analysis

In an effort to describe the needs of caregivers, as they transition to a support role for a loved one receiving in-home PELC, the data were organized according to the domains of needs outlined in the supportive care framework for cancer care (Fitch et al., 2008). The interview data were analyzed according to the approach of Miles and Huberman (2003), who recommend a three-step method: 1) data condensation (organization of the data); 2) data display (structured assembly of the information derived from the data); and 3) conclusion drawing/verification (final findings of all the data). Once a full transcription of the interviews had been prepared and analyzed in-depth, the themes that emerged were organized according to units of meaning and coded using NVivo 10 software.

RESULTS

Caregivers’ needs for support

In terms of informational needs, many caregivers stated that they were afraid of not having the necessary knowledge to take care of their loved one at home. The support of healthcare professionals was, therefore, identified as essential. Caregivers indicated they needed information on pain management, such as the procedures to follow for drug injections with the aim of ensuring optimal pain relief. “We gave the drug injections ourselves. Even my granddaughter did it. The nurse gave us a really clear explanation. It was easy” (Participant 15). Poor management or a lack of knowledge of symptoms can generate anxiety and prompt caregivers to resort to emergency services. It seems essential that they be able to turn to a resource person to obtain the necessary information and support: “[…] when there are episodes in the middle of the night, pain, side effects of the drugs […] we have questions when we don’t know what to do […] it’s important to have support, someone we can direct our questions to.” (Participant 15). Nurses and social workers were the professionals mentioned most often by caregivers.

From the prospective of physical needs, providing round-the-clock support to a dying loved one (medication management, hygiene, meal preparation) results in a lack of sleep. Some participants pointed out that exhaustion and the constantly increasing responsibilities are what led them to transfer their loved one to a facility: “Ultimately, we would have needed someone full-time to help us, because we were all exhausted. We went to (the deceased person)’s home. We never slept because he never slept. We were worried and we still went to work during the day […]. We went on for three weeks like this before we ended up finding him a bed in a palliative care home” (Participant 18). The need for support during the night, in order to be able to rest and provide better care during the day, was a frequently reported factor. In addition, caregivers said they were still feeling the consequences of their experience months after the death of their loved one.

A number of emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual needs were also pointed out. Uncertainty regarding the future was identified by caregivers as a source of anxiety. “Knowing she was getting worse and seeing her go downhill […] when I realized that things weren’t getting any better, the last six months were difficult; not knowing what to expect means you have to make things up as you go along” (Participant 14).

As their loved one’s condition worsens, caregivers find it even more difficult to leave and take a break. Although the need for respite is very real, caregivers paradoxically feel they should spend as much time as possible with their loved one, knowing that it is limited: “[…] it’s strange, because sometimes you think that having someone for the night to let you relax will do you a world of good, but at the same time, you’re so involved that you don’t want to miss anything. You feel like you’re the only one who can do it […] nobody can do this better than I can” (Participant 11). In addition, the existing trust and close relationship between caregivers and their loved one make it difficult to turn over their care to anyone else.

The whole experience turns a spousal or parent–child relationship into a caregiver–care recipient relationship, during which caregivers put their life on hold to take care of their loved one. “When you’ve lived with the same person for 35 years and you don’t recognize her anymore, it’s hard. I used to be her husband. But I turned into her nurse, her orderly, her handyman and her housekeeper” (Participant 17). However, the ability to share responsibilities with other family members and the presence of friends were both identified as ways to reduce the feelings of being burdened and isolated.

Caregivers of a loved one with an illness other than cancer reported that they had limited access to resources, often due to healthcare professionals’ lack of knowledge of the illness in question: “We applied to one place, but they didn’t seem to take people who didn’t have cancer […] because when I brought up the condition, uh-oh, I saw they were kind of lost” (Participant 14).

Finally, spiritual needs were voiced through the meaning caregivers ascribed to the home support experience. Most caregivers reported they had re-examined their priorities and realized the importance of living in the moment and appreciating the simple things in life. Some even looked on the experience as a privilege: “[…] it was a privilege to be so close to my father and help him do what he wanted to do: die at home. It was the best gift anyone could have given him: letting him die with dignity. It was something I really wanted to do for him” (Participant 11). They also maintained that dying at home made the experience more comfortable for everyone—something the turbulent atmosphere of a hospital could not have afforded them. Others mentioned they had been afraid that a home death would leave memories that would be difficult to erase, which is why they chose to go somewhere else. The presence of a nurse after the death helped make the experience a more positive one for many caregivers. “What touched me the most was that, after he died, we decided when to call the duty nurse. When the nurse came […] she was incredibly respectful. What she did was so beautiful. She took her time and then contacted the doctor to take care of the death certificate” (Participant 11).

Finally, caregivers reported a feeling of emptiness after the death of their loved one: “It took a long time to move on. Our life had been put on hold […] and when we came out of all this, it took a while to get back to normal” (Participant 18). They noted that they would have appreciated receiving support from healthcare professionals after their loved one’s death.

In terms of practical needs, caregivers indicated that the stability of the care team made it possible to develop a sense of trust with healthcare professionals and better monitor the status of their loved one’s health. “The nurse came here regularly. He trusted her […] she made suggestions as his condition got worse because she knew he wouldn’t accept the support immediately […] and when the time came, he said yes right away” (Participant 10). Round-the-clock access to services was also identified as essential to the quality of follow-up care. Conversely, the lack of timely access to services made caregivers feel like they were isolated and left to their own devices: “Ultimately, I needed more support, but I couldn’t get it […] there was nobody available because I don’t live near a city […] that’s when you really feel alone” (Participant 7). The nurse’s presence was invaluable in helping them shoulder their daily care responsibilities: “For a while, the nurses came twice a day to change dressings or simply to make sure that everything was OK. Other times, they called to check in. It was reassuring” (Participant 19). In addition, a social worker served as a central contact for the various people involved and helped introduce new services to facilitate home support.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the needs of caregivers of a loved one receiving in-home PELC and to describe the supporting role of nurses in this context. The middle-range theory of transitions (Meleis, 2010) made it possible to give careful consideration to the conditions that facilitate or hinder the transition to the caregiver role during the care trajectory. Adapting to this role is an ongoing process, during which many needs emerge.

The supportive care framework for cancer care (Fitch et al., 2008) helped specify the needs for which caregivers required support and to explore the efforts undertaken to try to respond to them. The informational needs focus on the importance of access to information to be able to manage the various aspects of the loved one’s condition, particularly as it pertains to symptoms of the illness and medication. Nursing support is essential in this regard. Funk et al. (2015) report that timely access to relevant information helps in understanding and accepting the diagnosis of a terminal disease. Furthermore, caring for a dying loved one has an impact on a caregiver’s physical needs. Their constant presence results in fewer hours of sleep and increased fatigue. Harding et al. (2012) also recognize that some health problems such as heart disease limit a caregiver’s ability to take charge of their loved one’s care, although the caregivers interviewed for this study didn’t really raise this issue.

An analysis of emotional and psychosocial needs made it possible to outline the changes that occur in the relationship between a caregiver and a loved one, particularly as it concerns the transition to the caregiver role. The caregivers in this study repeatedly brought up that they put their own lives on hold to be able to take care of their loved one. Horseman et al. (2019) confirm that caregivers disregard their personal needs and that this prevents them from admitting they require support. The caregivers reported that the relationship with their loved one was transformed from one of a spouse or a child to that of a caregiver. Holm et al. (2015) specify that adapting to this new role is an ongoing process throughout the care trajectory.

Finally, an examination of caregivers’ spiritual needs shows that taking care of a patient receiving in-home PELC prompts them to re-examine their life priorities. The caregiving experience was described by some as a privilege, and the home environment was identified as a more compassionate and peaceful solution. Similar to what was found by Hasson et al. (2010), caregivers report a profound feeling of emptiness following the death of their loved one and mention the need for the support of healthcare professionals during the grieving period. This support seems to be lacking. Johnson (2015) puts forward that it is part of the nursing role to support caregivers during the bereavement process, in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team.

A review of the practical needs reveals that it is essential for caregivers to have access to 24/7 support from healthcare professionals. This continuity of care allows caregivers to build trust with nurses and facilitates the monitoring of changes in a loved one’s condition. Although some studies have found that the healthcare professionals assigned to a patient change frequently (Seamark et al., 2014), the caregivers interviewed for this study said changes were infrequent, which was reassuring. The presence of a nurse allows caregivers to become more familiar with the care being provided to their loved one and to validate their actions. Wahid et al. (2018) report that the lack of support from healthcare professionals undermines caregivers’ self-confidence and favours reliance on emergency services. The caregivers in this study also emphasized the need to receive assistance for domestic tasks such as housekeeping and meal preparation, given the perpetual nature of managing their loved one’s care. Ewing and Grande (2012) found that the performance of these tasks adds to caregivers’ anxiety, particularly when they also have a job. Sharing responsibilities with fellow family members and friends is, therefore, essential and helps reduce the feeling of isolation (Totman et al., 2015). Although they acknowledged the essential need for respite when taking care of their loved one, caregivers said they wanted to spend as much time as possible with them.

This study found that in-home PELC for a loved one suffering from an illness other than cancer did not have the same level of access to care. Participants indicated that access to some services (such as admission to a palliative care home) was refused and that healthcare professionals lacked knowledge of their loved one’s illness and the available services. Other studies maintain that this inequality is due in part to the perception that PELC is intended for cancer patients (Hasson et al., 2010) and to healthcare professionals’ lack of knowledge (Aoun et al., 2017). This can result in a delay in the referral to the appropriate services. An early integrated palliative care approach would allow a better response to the needs of individuals and their families throughout the illness trajectory and would contribute to improving overall quality of life (ASCP/CHPCA & Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada, 2015).

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study has certain limitations. First, the sample size does not allow the results concerning the support needs of caregivers of a loved one receiving in-home PELC to be generalized to all caregivers. Moreover, only one participant was a caregiver for a loved one suffering from an illness other than cancer. It is, therefore, impossible to confirm whether the needs encountered during this illness trajectory are similar to the others. Finally, the majority of caregivers encountered in this study were in mourning, which may have influenced their perceptions of the experience.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study shed light on the multiple needs of caregivers and the necessity of addressing these needs to facilitate home support and dying at home when this option is chosen by a patient and their caregivers. It is essential to develop a trajectory of care and services that meet these needs and continue during the bereavement period. Nursing support through education about care, medication, management of symptoms, and emotional support helps meet caregivers’ needs in a timely manner, establish a trusting relationship and make home support and dying at home feasible. Future studies should focus on the necessity of an early integrated palliative care approach that includes caregivers in order to facilitate timely access to appropriate care and services throughout the illness trajectory.

REFERENCES

- Aoun S, Deas K, Kristjanson LJ, Kissane DW. Identifying and addressing the support needs of family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease using the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2017;15(1):32–43. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASCP/CHPCA. Association canadienne de soins palliatifs/Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association & La Coalition pour des soins de fin de vie de qualité au Canada. Cadre national « Aller de l’avant » : feuille de route pour l’intégration de l’approche palliative, Initiative Aller de l’avant : des soins qui intègrent l’approche palliative. Gouvernement du Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carlander I, Sahlberg-Blom E, Hellström I, Ternestedt B-M. The modified self: Family caregivers’ experiences of caring for a dying family member at home. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(7–8):1097–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing G, Grande G. Development of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for end-of-life care practice at home: A qualitative study. Palliative Medicine. 2012;27(3):244–256. doi: 10.1177/0269216312440607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Veillette A, Wilson D, Dumont S, Lavoie S. Les racines de la « Belle Mort » : Une étude ethnographique en milieu rural au Québec. Les Cahiers francophones de soins palliatifs. 2009;9:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch MI, Porter HB, Page BD. Supportive care framework: A foundation for person-centred care. Pappin Communications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Funk LM, Stajduhar KI, Outcalt L. What family caregivers learn when providing care at the end of life: A qualitative secondary analysis of multiple datasets. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2015;13(3):425–433. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513001168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. British Medical Journal (International Edition) 2006;332(7540):515–521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Hamilton D, Bridger S, Robinson V, George R, Higginson I. What are the perceived needs and challenges of informal caregivers in home cancer palliative care? Qualitative data to construct a feasible psycho-educational intervention. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20(9):1975–1982. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson F, Kernohan WG, McLaughlin M, Waldron M, McLaughlin D, Chambers H, Cochrane B. An exploration into the palliative and end-of-life experiences of carers of people with Parkinson’s disease. Palliative Medicine. 2010;24(7):731–736. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert J, Ouellet N, Lessard L, Babineau L, Veillette A-M, Coutu M. Rapport de recherche : Conditions favorisant et limitant le maintien à domicile en soins palliatifs et de fin de vie sur le territoire du CISSS de Chaudière-Appalaches. Québec: Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux de Chaudière-Appalaches; 2017. https://www.cisss-ca.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/documents/Services_offerts/Soins_palliatifs_et_de_fin_de_vie/Projet_SPFV-I_Rapport_final_CISSS-CA_H%C3%A9bert_et_al_2017-11-08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Holm M, Henriksson A, Carlander I, Wengström Y, Öhlen J. Preparing for family caregiving in specialized palliative home care: An ongoing process. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2015;13(3):767–775. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horseman Z, Milton L, Finucane A. Barriers and facilitators to implementing the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool in a community palliative care setting. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2019;24(6):284–290. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2019.24.6.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. Role of district and community nurses in bereavement care: A qualitative study. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2015;20(10):494–501. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2015.20.10.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Soins palliatifs et de fin de vie: Plan de développement 2015–2020. 2015. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2015/15-828-01W.pdf.

- L’Appui pour les proches aidants d’aînés. Portrait statistique des proches aidants de personnes de 65 ans et plus au Québec, 2012. Montréal, Québec: 2012. https://www.lappui.org/content/download/10915/file/2016_Portrait%20statistique.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Légis Québec. Loi concernant les soins de fin de vie. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec; 2018. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/ShowDoc/cs/S-32.0001. [Google Scholar]

- Mason N, Hodgkin S. Preparedness for caregiving: A phenomenological study of the experiences of rural Australian family palliative carers. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2019 doi: 10.1111/hsc.12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis AI. Transitions theory: Middle range and situation specific theories in nursing research and practice. Springer Publishing Company; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Analyse des données qualitatives. De Boeck Supérieur; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- OMS/WHO Organisation mondiale de la Santé/World Health Organization. Soins palliatifs. 2018. http://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

- Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Shipley PZ, Loeb SJ, Baney B. A model of caregiving through the end of life: Seeking normal. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2012;34(2):174–193. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CA, Bottorff JL, McFee E, Bissell LJ, Fyles G. Caring at home until death: Enabled determination. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017;25(4):1229–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamark D, Blake S, Brearley SG, Milligan C, Thomas C, Turner M, Payne S. Dying at home: A qualitative study of family carers’ views of support provided by GPs community staff. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2014;64(629):796–803. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X682885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy-Skeffington B, McLean S, Bramwell M, O’Leary N, O’Gorman A. Caregivers experiences of managing medications for palliative care patients at the end of life: a qualitative study. The American Journal Of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2014;31(2):148–154. doi: 10.1177/1049909113482514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCC/CCS. Société canadienne du cancer/Canadian Cancer Society. Soins de fin de vie au Québec. Priorité aux soins palliatifs : accès, temps, lieu (Mémoire) Société canadienne du cancer – division Québec, Québec; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soroka JT, Froggatt K, Morris S. Family caregivers’ confidence caring for relatives in hospice care at home: An exploratory qualitative study. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2018;35(12):1540–1546. doi: 10.1177/1049909118787779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistique Canada. Tableau 13-10-0715-01 Décès, selon le lieu de décès (en milieu hospitalier ou ailleurs qu’en milieu hospitalier) Gouvernement du Canada; 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/fr/tv.action?pid=1310071501&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.6. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Teno J, Patrick DL, Lynn J. The concept of quality of life of dying persons in the context of health care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1999;17(2):93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totman J, Pistrang N, Smith S, Hennessey S, Martin J. ‘You only have one chance to get it right’: A qualitative study of relatives’ experiences of caring at home for a family member with terminal cancer. Palliative Medicine. 2015;29(6):496–507. doi: 10.1177/0269216314566840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid AS, Sayma M, Jamshaid S, Kerwat DA, Oyewole F, Saleh D, Payne S. Barriers and facilitators influencing death at home: A meta-ethnography. Palliative Medicine. 2018;32(2):314–328. doi: 10.1177/0269216317713427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E, Caswell G, Turner N, Pollock K. Managing medicines for patients dying at home: A review of family caregivers’ experiences. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2018;56(6):962–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]