BACKGROUND

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic presents a threat to health care systems worldwide. Trauma centers may be uniquely impacted, given the need for rapid invasive interventions in severely injured and the growing incidence of community infection. We discuss the impact that SARS-CoV-2 has had in our trauma center and our steps to limit the potential exposures.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective evaluation of the trauma service, from March 16 to 30, following the appearance of SARS-CoV-2 in our state. We recorded the daily number of trauma patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the presence of clinical symptoms or radiological signs of COVID-19, and the results of verbal symptom screen (for new admissions). The number of trauma activations, admissions, and census, as well as staff exposures and infections, was recorded daily.

RESULTS

Over the 14-day evaluation period, we tested 85 trauma patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and 21 (25%) were found to be positive. Sixty percent of the patients in the trauma/burn intensive care unit were infected with SARS-CoV-2. Positive verbal screen results, presence of ground glass opacities on admission chest CT, and presence of clinical symptoms were not significantly different in patients with or without SARS-CoV-2 infection (p > 0.05). Many infected patients were without clinical symptoms (9/21, 43%) or radiological signs on admission (18/21, 86%) of COVID-19.

CONCLUSION

Forty-five percent of trauma patients are asymptomatic at the time of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Respiratory symptoms, as well as verbal screening (recent fevers, shortness of breath, cough, international travel, and close contact with known SARS-CoV-2 carriers), are inaccurate in the trauma population. These findings demonstrate the need for comprehensive rapid testing of all trauma patients upon presentation to the trauma bay.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Diagnostic tests or criteria, level III, Therapeutic/care management, level IV.

KEY WORDS: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, coronavirus, nosocomial infection, trauma centers

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is disrupting health systems and presenting extreme challenges to hospitals worldwide. Hospitals now must serve critical roles in testing, isolating, and treating patients with the disease while preventing further spread through nosocomial transmission.1 Health care workers (HCW) are increasingly contracting the illness, coronavirus disease (COVID-19), thereby decreasing the human resources available to care for a population in crisis.1–3 Previous viral epidemics of the 21st century, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, have demonstrated similar effects on HCW, comprising up to 40% of those infected.4–6 While many elective surgical procedures can be postponed during this time of need, injuries still occur, and trauma, burn and emergency general surgery services must remain operational.7,8 Hospitals with trauma centers are having to balance the critical resources for treating patients with severe illness from COVID-19 with the need to maintain their acute care mission to serve the ongoing needs of the community.

Over 80% of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have been reported with either minimal or no symptoms.9 As the prevalence of disease increases in any given locality, so too will the proportion of trauma patients who present with incidental SARS-CoV-2 infection, increasing the risk of exposure and nosocomial HCW infection. Emergency rooms, intensive care units (ICUs), and operating rooms are high-risk areas for transmission of respiratory infections given the urgency in management and the need for high transmission-risk aerosolizing procedures, such as intubations, cricothyroidotomies, tracheostomies, bronchoscopies, airway suctioning, and thoracostomy tubes.10 Trauma patients also require direct patient contact from a large number of health care providers including the primary trauma team (nurses and physicians), specialty consultants, and multiple therapy specialists, such as respiratory, physical, and occupational therapy. With a reported transmission rate of 2.3 to 2.79 newly infected persons per patient (making it more infectious than the 1918 influenza that killed 50 million worldwide), a single trauma patient with occult SARS-CoV-2 infection has the potential to infect a large number of critical health care providers.11–13 Over 3,300 HCW are reported infected so far in China, with 15% critically ill.2,9 Similarly, Italian HCW comprise almost 10% of all those infected.3 Many hospitals are able to deal with occasional high-risk cases, but the additional strain presented by a high prevalence of disease, limited PPE resources, and staff under pressure, greatly increases the risks of transmission and the burden on our health care systems during this pandemic.1

Multiple academic societies have reported on the preventative measures needed in the management of patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection.14–16 While the position is becoming well defined for those patients with known, established disease, there is little available data to guide trauma centers that may be required to treat significant numbers of asymptomatic infected new patients during this ongoing crisis. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the early impact of COVID-19 on the operation of our trauma center, with particular emphasis on the prevalence of COVID-19 on our current inpatient population and the potential risks posed by asymptomatic COVID-19–positive patients to HCW and other uninfected patients.

METHODS

Design and Setting

We performed an observational evaluation of the trauma service at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital (UABH), beginning with the spread of COVID-19 to our state. The University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board reviewed the project and allowed us to proceed with a determination of nonhuman subjects research. Approval from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board was obtained for this project. Located in downtown Birmingham, UABH serves as a tertiary referral center for the state of Alabama and is an American College of Surgeons–verified Level I trauma center. The trauma service evaluated 4,844 and admitted 3,665 trauma and burn patients in 2019.

Alabama was one of the last states with a confirmed COVID-19 patient, with the first case reported on March 13, 2020. Despite a small number of reported cases in the community, our Acute Care Surgery Division moved to implement screening of new trauma patients on March 18 given our concerns for asymptomatic, undiagnosed COVID-19 patients entering the trauma system. A strategy was implemented early to maximize health care force protection by limiting potential exposures. Prior to March 18, the trauma team for severely injured patients consisted of the attending trauma surgeon, emergency department (ED) attending, three residents (trauma surgery senior and junior, ED senior), two bedside nurses, a pharmacist, and a patient care technician.

Interventions

Allied health, nursing, and medical students were eliminated from participation in trauma activations, minimizing the personnel allowed in the resuscitation room. To reduce cross contamination of COVID-19 from the main ED care area, ED faculty halted participation in trauma patient evaluation. Emergent intubations in the trauma bay were restricted to the senior anesthesia provider.

Verbal Screening

Where possible, trauma patients underwent prehospital verbal symptom screening for COVID-19 symptoms by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel. This information was then relayed to the trauma team as part of the prearrival notification page. Repeat verbal symptom screening was then performed upon arrival.

Definition of Symptom Screening

Patients were asked the following yes/no questions, with any positive question signifying a positive screen: any recent fevers, shortness of breath, cough, international travel, contact with known SARS-CoV-2 carriers.17 Patients were categorized as COVID-19 verbal symptom screen negative, positive, or unknown (in the event the patient was unable to provide history for any reason).

Team Response to Symptom Screening

All verbal symptom screen positive and unknown patients were treated as persons under investigation (PUI) and all trauma team members used the maximum personal protective equipment (PPE) strategy, consisting of surgical masks, gowns, eye protection, and gloves. For trauma PUI requiring potential aerosolizing interventions, providers were instructed to don enhanced PPE, including N95 masks, face shields, impermeable gowns, and double gloves. One of the trauma resuscitation rooms was equipped with a portable high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter to increase air changes and potential viral clearance and all screen positive or unknown patients were placed in this room.

Laboratory and Radiographic Testing

UABH-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) SARS-CoV-2 testing became available on March 19. After this date, all new trauma patients that were screen positive or unknown for COVID-19 were tested upon arrival. Patients would remain as PUI status with enhanced precautions until results returned.

In addition, on March 20th, we reviewed the admission chest computed tomography (CT) imaging of all trauma inpatients for patchy opacities, based on previous literature of the radiographic findings of COVID-19 patients. Those patients with radiological findings were also tested for COVID-19.

Data Collection and Analysis

We collected trauma service level data regarding the overall census, occupied critical care beds, the number of trauma activations, and trauma admissions. In addition, we documented the overall number of new patients who had undergone COVID-19 verbal symptom screening, laboratory testing, and the number of positive tests. Those undergoing laboratory testing were classified as symptomatic or asymptomatic, with regard to potential COVID-19 infection. Symptomatic was defined as fever higher than 100.4°F, cough, shortness of breath, or acute change in oxygen requirement (increase of >2 l/min O2 in spontaneously breathing patients, or increase of >10% FiO2 in ventilated patients, over the past 24 hours). Admission CT scans of the chest were considered as positive for signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection if ground glass opacities were identified in the final interpretation from the attending radiologist. The number of physician staff who were exposed to high-risk procedures, tested positive, and were restricted from work due to quarantine was also documented.

The data are presented on a day-by-day timeline with key events and measures included. Data are presented as proportions and absolute values. Categorical data comparisons between patients with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection were performed with either Fisher exact or χ2 testing, as appropriate. All data analyses were performed using SPSS v. 26 (International Business Machines, New York, NY).

RESULTS

Temporal Course

Between March 16 and March 30, there were 170 trauma activations with 54 (31.8%) patients admitted to the ICU and 59 (34.7%) patients admitted to the floor (Table 1). The remainder were discharged from the ED. At the beginning of the study period, 100% of the trauma service beds were occupied, with 36 ICU beds and 48 floor beds. By the end of the study period, there were only 17 (47%) occupied trauma ICU beds and 19 (40%) occupied trauma floor beds.

TABLE 1.

Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on Trauma Service From March 16 to March 30, 2020

| Total | |

|---|---|

| Trauma activations, n | 170 |

| Trauma admissions | 113/170 (66) |

| ICU | 54/113 (48) |

| Floor | 59/113 (52) |

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests performed | 85/170 (50) |

| New trauma activations | 21/85 (25) |

| Positive COVID | 4/21 (19) |

| Floor patients | 40/85 (47) |

| Positive COVID | 4/40 (10) |

| ICU patients | 24/85 (28) |

| Positive COVID | 13/24 (54) |

| Admitted prior to verbal screening | 45/85 (53) |

| Received verbal screening | 40/85 (47) |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | 21/85 (25) |

*Results shown as n of total (%), unless otherwise noted.

**Verbal screen positive if yes to any of the following: Have you had any recent fever, cough, shortness of breath, contact with known coronavirus patient, or international travel?17

†Chest CT positive, ground glass opacities on admission chest CT.

Our initial review of 54 inpatient CT scans revealed 9 patients with radiological findings consistent with possible COVID-19 infection. These patients were reviewed with the infectious disease (ID) Medical Quality Officer and eight of the nine were tested for SARS-CoV-2. This resulted in our first trauma burn ICU (TBICU) patient with a positive test. The patient had been an inpatient in the TBICU for 6 days and was admitted on March 13, the same date as the first reported COVID-19 case in the State of Alabama. One additional patient tested positive, and after further discussion with the infectious disease medical quality officer and infection control practitioners, the decision was made to test all TBICU patients on March 23. At the time of comprehensive TBICU testing, 20 trauma patients were in the ICU and 12 (60%) were infected with SARS-CoV-2. Given these findings, we expanded testing to the trauma floors where 4 (11%) of the 36 patients were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

We continued to evolve our trauma bay management during this time. A second trauma bay was outfitted with a HEPA filter. All aerosolizing procedures (Table 2) were performed in a HEPA filter bay with minimal staffing in maximum PPE as outlined in the attached protocol that was implemented on March 21.

TABLE 2.

Trauma Bay PPE Requirements for HCWs for Patients With Positive or Unknown Verbal Screening for SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| Setting | Patients undergoing aerosolizing procedure* | Patients not undergoing aerosolizing procedure but HCW within 6 ft of patient | Patients not undergoing aerosolizing procedure, HCW not closer than 6 ft |

| Personnel allowed within room | Senior resident or attending, bedside nursing, ± respiratory therapist | Senior and junior resident, attending surgeon, bedside nursing, respiratory therapist | Senior and junior resident, attending surgeon, bedside nursing, respiratory therapist, pharmacist, patient care technician |

| PPE requirement | Faceshield or goggles N95 mask Impermeable gown (Level 4) Bouffant cap Double gloves |

Procedural mask with visor OR Procedural mask and goggles Yellow gown Single gloves |

Procedural mask Gloves |

*Procedures considered high risk for aerosolization: intubation, cricothyroidotomy, CPR, bronchoscopy, tube thoracostomy, resuscitative thoracotomy.

The screening and testing procedure in the trauma bay subsequently identified four additional SARS-CoV-2–infected patients. None had positive verbal symptom screens. One patient, whose COVID-19 status could not be determined, had suffered a gunshot wound, was in shock and required emergent surgical intervention. One patient was screen negative and asymptomatic but nevertheless tested SARS-CoV-2 positive after undergoing testing prior to planned semielective operation with oral and maxillofacial surgery. The other two patients were screen result unknown and subsequently tested positive.

The initial six ICU trauma patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 were transferred to the medical ICU to cohort infected patients as part of the institutional COVID-19 response plan. As additional cases were identified, all patients in the TBICU were moved to the Neurosurgical ICU which was repurposed to care for COVID-19 positive trauma patients. The TBICU then underwent terminal cleaning before being designated as a unit for COVID-19 negative patients. The number of new diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 in trauma patients has since reduced, at least until the time of completion of this manuscript.

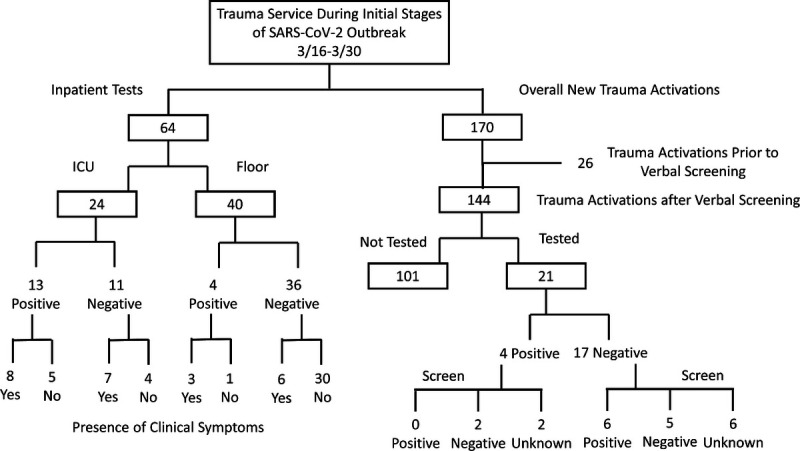

Characteristics and Outcome of SARS-CoV-2–Positive Trauma Patients

In less than 2 weeks after initiating testing for COVID-19 at UABH, we identified 21 trauma patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection of 85 tested (Table 3). Sixty percent of patients in the trauma ICU were found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of those patients with COVID-19, nearly half (9/21) were asymptomatic (Fig. 1). Verbal symptom screening for COVID-19 failed to identify any of the new trauma patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ground glass opacities on CT were also poorly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in trauma patients, present in only 3 of 21 patients with confirmed COVID-19. Neither positive verbal screen results (0% vs. 17%, p = 0.57), presence of ground glass opacities on admission chest CT (14% vs. 24%, p = 0.34), nor presence of clinical symptoms (52% vs. 33%, p = 0.08) were different in patients with or without SARS-CoV-2 infection. Two of the 21 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have died at the time of submitting this article.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Patients With and Without SARS-CoV-2 on Trauma Service From March 16 to 30, 2020

| SARS-CoV-2 Infection (n = 21) | No SARS-CoV-2 Infection (n = 64) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal screen status | 33 (7/21) | 56 (36/64) | |

| Positive | 0 (0/7) | 17 (6/36) | 0.57 |

| Negative | 57 (4/7) | 58 (21/36) | 1.00 |

| Unknown | 43 (3/7) | 25 (9/36) | 0.38 |

| Chest CT | 100 (21/21) | 97 (62/64) | |

| Positive | 14 (3/21) | 24 (15/62) | 0.34 |

| Negative | 86 (18/21) | 76 (47/62) | |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| Symptomatic | 52 (11/21) | 33 (21/64) | 0.08 |

| Asymptomatic | 43 (9/21) | 67 (43/64) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1/21) | 0 |

*Results shown as % (n of total).

**Verbal screen positive if yes to any of the following: Have you had any recent fever, cough, shortness of breath, contact with known coronavirus patient, or international travel?

†Chest CT-positive, ground glass opacities on admission chest CT.

Figure 1.

Diagram of trauma service activity, testing, and infection status.

Staff Exposure and Testing

The acute care surgery service is staffed by nine attending surgeons at normal baseline to support the different missions of the division. During the study period, the attending work force was reduced to limit potential exposures. Following the first confirmed infection on the trauma service on March 22, we identified six attending surgeons who had been exposed within the first week of operations. Two attendings developed fevers and were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection, but were not found to be infected. Overall, 67 attending work days were lost during the study period due to quarantine and staff reduction.

DISCUSSION

The UAB Trauma experience demonstrates the need for early and aggressive testing of trauma patients given the high likelihood of asymptomatic COVID-19 disease. Testing current inpatients in addition to universal testing of all new trauma patients may be helpful in protecting trauma systems during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Maintaining a posture of extreme vigilance, assuming that all patients are positive until infection status is confirmed by accurate and potentially repeated testing will protect HCW from exposure and may limit nosocomial infection.

Testing of our inpatient trauma population identified a significant proportion of COVID-19 patients already present in our hospital. In retrospect, these patients were not under appropriate isolation and staff were not aware of the need for enhanced PPE precautions for COVID-19. Subsequent early identification of the infection status of our inpatient cohort once COVID-19 testing became available allowed us to enhance our isolation measures, control spread within our system, and help decrease the nosocomial spread among HCW and patients. Likely, earlier initiation of universal testing may have prevented the widespread nosocomial infection that we subsequently identified in our ICU.

Our experience also demonstrates that current screening mechanisms for SARS-CoV-2 infection are inadequate in a population with a growing prevalence of occult disease. Verbal symptom screening for COVID-19, without confirmatory testing, proved to be an inadequate means of identifying infected patients, and thus limiting nosocomial transmission, within a trauma system. Further, the use of CT to identify ground glass opacities among the severely injured may be complicated by findings such as aspiration or pulmonary contusion, which are common in the trauma population. Clinical symptoms experienced by patients with COVID-19 often mirror those of trauma patients in the postinjury, proinflammatory state.

Complicating matters, asymptomatic patients with occult SARS-CoV-2 infection demonstrate similar viral loads compared with patients with symptomatic disease,18 and viral transmission from asymptomatic patients has been documented.19 Trauma patients routinely require aerosolizing procedures, such as intubation, bronchoscopy, thoracostomy, and tracheostomy, placing members of the trauma team at increased risk of infection. For this reason, we strongly advocate for testing all new trauma patients for COVID-19 on arrival to the hospital. In the event of exposure to patients with COVID-19, we recommend staff and faculty to monitor for fever and symptom development and to quarantine in the event of symptoms pending testing. Like many institutions, we still face testing capacity limitations and just started universal testing of all trauma patient on April 3rd.

CONCLUSION

Our early experience of COVID-19 demonstrates the need to test all trauma patients for COVID-19, to understand prevalence of the disease, and implement appropriate control measures. All new trauma patients should be regarded as SARS-CoV-2 positive until testing can be completed to minimize exposures to staff and limit nosocomial spread of disease. Given the large volume of aerosolizing procedures performed on trauma patients, it is important that trauma centers protect providers, and other patients, by widely testing for SARS-CoV-2. The more rapidly a center can identify SARS-CoV-2 infection and instigate appropriate control measures, the better it will be able to minimize exposure to and transmission of the disease.

AUTHORSHIP

PH, JJ, JK, JBH, RL, and DC were responsible for the study design.

PH, RU, VP, JH, DN, and DC were responsible for data collection.

PH was responsible for data analysis.

PH was responsible for figure creation.

All authors were responsible for data interpretation, manuscript creation, and critical review.

The UAB Acute Care Surgery COVID-19 Consortium consisted of all coauthors, in addition to the following: Karen N. Brown, MSHA, Kimberly Hendershot, MD, Lauren Tanner, MD, Jacob Anderson, DO, Jon Winkler, MD, PhD, Michael A. Beckwith, MD, Ross Vander Noot, MD, Shannon Carroll, MD, Donald Reiff, MD, and Samuel Windham, MD.

DISCLOSURE

Our work has no outside sources of support or funding to report. It has not been presented at any meeting.

Dr. John B. Holcomb is a co-founder and on the Board of Directors of Decisio Health, on the Board of Directors of QinFlow and Zibrio, a Co-inventor of the Junctional Emergency Tourniquet Tool, an adviser to Arsenal Medical, Cellphire, Spetrum, PotentiaMetrics, Thermal Logistics and Wake Forest Institute of Regenerative Medicine. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published online: June 29, 2020.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brindle M, Gawande A. Managing COVID-19 in surgical systems. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e1–e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oddone E. Thousands of medical staff infected with coronavirus in Italy aljazeera.com. AlJazeera; 2020. [updated 03/18/2020; cited 2020 March 24]. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/rising-number-medical-staff-infected-coronavirus-italy-200318183939314.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varia M Wilson S Sarwal S McGeer A Gournis E Galanis E Henry B, Hospital Outbreak Investigation T . Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada. CMAJ. 2003;169(4):285–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goh KT, Cutter J, Heng BH, Ma S, Koh BK, Kwok C, Toh CM, Chew SK. Epidemiology and control of SARS in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(5):301–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S, Chan TC, Chu YT, Wu JT, Geng X, Zhao N, Cheng W, Chen E, King CC. Comparative epidemiology of human infections with Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses among healthcare personnel. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller J. Sages recommendations regarding surgical response to COVID-19 crisis 2020. 03/19/2020:[Available from: https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/.

- 8.Surgeons ACo COVID-19: recommendations for Management of Elective Surgical Procedures. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2020. [updated 03/13/2020; cited 2020 03/27]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judson SD, Munster VJ. Nosocomial transmission of emerging viruses via aerosol-generating medical procedures. Viruses. 2019;11(10):940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long Y, Hu T, Liu L, Chen R, Guo Q, Yang L, Cheng Y, Huang J, Du L. Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks against influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Med. 2020;13:93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuite AR, Fisman DN. Reporting, epidemic growth, and reproduction numbers for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) epidemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(8):567–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklov J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz J, King CC, Yen MY. Protecting health care workers during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak -lessons from Taiwan's SARS response. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewster D Chrimes N Do NT, et al. Consensus statement: safe airway society principles of airway management and tracheal intubation specific to the COVID-19 adult patient group. Med J Aust. 2020;212:472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Update and interim guidance on outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [website]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 [updated 02/25/2020; cited 2020 05/25/2020]. Available from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/HAN00428.asp.

- 18.Zou L Ruan F Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothe C Schunk M Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]