Abstract

Objectives

Cytomegalovirus infection is thought to affect the immune system and to impact general health during ageing. Higher CMV‐specific antibody levels in the elderly are generally assumed to reflect experienced viral reactivation during life. Furthermore, high levels of terminally differentiated and CMV‐specific T cells are hallmarks of CMV infection, which are thought to expand over time, a process also referred to as memory inflation.

Methods

We studied CMV‐specific antibody levels over ~ 27 years in 268 individuals (aged 60–89 years at study endpoint), and to link duration of CMV infection to T‐cell numbers, CMV‐specific T‐cell functions, frailty and cardiovascular disease at study endpoint.

Results

In our study, 136/268 individuals were long‐term CMV seropositive and 19 seroconverted during follow‐up (seroconversion rate: 0.56%/year). CMV‐specific antibody levels increased slightly over time. However, we did not find an association between duration of CMV infection and CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint. No clear association between duration of CMV infection and the size and function of the memory T‐cell pool was observed. Elevated CMV‐specific antibody levels were associated with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease but not with frailty. Age at CMV seroconversion was positively associated with CMV‐specific antibody levels, memory CD4+ T‐cell numbers and frailty.

Conclusion

Cytomegalovirus‐specific memory T cells develop shortly after CMV seroconversion but do not seem to further increase over time. Age‐related effects other than duration of CMV infection seem to contribute to CMV‐induced changes in the immune system. Although CMV‐specific immunity is not evidently linked to frailty, it tends to associate with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: ageing, cardiovascular disease, CMV‐specific antibodies, cytomegalovirus infection, frailty, T‐cell response

We conducted a retrospective longitudinal study spanning ~27 years, which enabled us to identify cytomegalovirus (CMV) seroconverters in an ageing population and to quantify duration of CMV infection. We found that age‐related effects other than duration of CMV infection are important to CMV‐induced changes in the immune system, such as T‐cell responses and the expansion of the T‐cell memory pool. Although CMV‐specific immunity is not evidently linked to frailty, it tends to associate with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease.

Introduction

Primary infection with CMV results in life‐long latency, but only leads to severe disease and viral dissemination in severely immunocompromised individuals. In immunocompetent individuals, CMV infection usually remains asymptomatic due to responses of the humoral and cellular immune system. 1 , 2 , 3 In immunocompetent individuals, the virus is thought to reactivate and to boost the immune system regularly 1 , 2 , 3 which may explain the changes in the T‐cell compartment observed with CMV infection. 4

CMV‐specific antibody levels have frequently been positively associated with age. 5 , 6 , 7 CMV latent viral load, as measured in CMV‐infected monocytes, 7 blood/plasma 8 and urine, 2 has been related to higher age and is associated with CMV‐specific antibody levels. These antibody levels are often used as a measure for experienced CMV reactivation and to identify CMV‐seropositive elderly with poor control of the virus, who are at increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Since most studies rely on cross‐sectional data, the underlying factors influencing CMV‐specific antibody levels, and in particular the role of duration of CMV infection, in fact remain unknown.

Many parallels can be drawn between the well‐described changes in the T‐cell pool caused by CMV infection and those observed during ageing. 4 , 16 Effects of CMV on the T‐cell compartment 17 are thought to be due to the presence of large CMV‐specific T‐cell expansions, which can mount up to 30% to 90% 18 , 19 of the circulating CD8+ T‐cell pool in many elderly. 20 CMV‐specific CD8+ memory T‐cell numbers are assumed to increase over time, a process that is often referred to as ‘memory inflation’. Memory inflation is unique for CMV 21 , 22 and is believed to be most prominent for CD8+ T cells 20 , 22 , 23 but is also observed for CD4+ T cells. 21 However, how prolonged exposure to CMV enhances immune reactivity is not well understood. Further insight in CMV‐induced memory inflation is valuable in understanding the potential harmful effect of CMV upon ageing.

The accumulating changes in the immune system due to prolonged exposure to CMV infection may eventually influence general health. CMV‐infected individuals have been reported to have a higher prevalence of age‐related conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis 24 and cardiovascular diseases. 14 Also, mortality rates are higher in CMV‐infected individuals 25 , 26 and in individuals with higher CMV‐specific antibody levels. 11 , 15 , 26 The mechanisms underlying the relationships between CMV infection and general health outcomes are still unknown. Although several studies show a relation between CMV infection or CMV‐specific antibody levels and frailty, 11 , 27 , 28 others do not support this. 29 , 30 These conflicting results might be explained by differences in duration of CMV infection, which is generally unknown.

Here, we used a unique long‐term longitudinal study to investigate the effects of duration of CMV infection on the immune system and general health. We assessed how CMV‐specific antibody levels developed within a cohort of older individuals (60–89 years at study endpoint) over a follow‐up time of 25–30 years. We relate duration of CMV infection to CMV‐specific antibody levels, numbers of various T‐cell subsets, function of CMV‐specific T cells, frailty and prevalence of cardiovascular disease.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

In total, 268 people who have been participating since ~ 1987 in the ongoing Doetinchem Cohort study (DCS, Doetinchem, The Netherlands 31 , 32 ) were included in this study (n = 135 men, n = 133 women), with an average age of 70.6 (60.3–88.6) years at endpoint (Table 1). Follow‐up time was 27.7 years on average (range 25–30 years). Study design is summarised in Figure 1a. More details about the study cohort can be found in the methods section. All individuals were analysed for the presence of CMV‐specific antibodies. At study endpoint, 58% of the participants (n = 155) were CMV seropositive (CMV+) (Table 1 and Supplementary figure 1). No significant differences in age, educational level and sex were observed between CMV‐seronegative (CMV−) and CMV+ individuals (Table 1). Follow‐up time was similar for CMV− and CMV+ participants.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of the study population

| Names | Total (n = 268) | Serostatus | Duration of CMV infection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV– (n = 113) | CMV+ (n = 155) | P‐value* | ST CMV+ (n = 19) | LT CMV+ (n = 136) | P‐value* | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Age at study baseline (years) | 43.3 (6.6) | 43.9 (7.1) | 42.9 (6.2) | 0.38 | 42.2 (7.5) | 43 (6) | 0.510 |

| Age at study endpoint (years) | 70.9 (6.7) | 71.7 (7.2) | 70.6 (6.2) | 0.32 | 70.4 (7.5) | 70.6 (6.1) | 0.780 |

| Follow‐up duration | |||||||

| Total follow‐up time span (years) | 27.7 (1.2) | 27.7 (1.2) | 27.7 (1.1) | 0.61 | 28.2 (1.3) | 27.6 (1.1) | 0.030 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Women, % (n) | 49.6 (133) | 43.4 (49) | 54.2 (84) | 0.08 | 73.7 (14) | 51.5 (70) | 0.069 |

| Education | |||||||

| Low, % (n) | 44 (118) | 41.6 (47) | 45.8 (71) | 0.78 | 47.4 (9) | 45.6 (62) | 0.410 |

| Middle, % (n) | 27.6 (74) | 28.3 (32) | 27.1 (42) | 36.8 (7) | 25.7 (35) | ||

| High, % (n) | 28.4 (76) | 30.1 (34) | 27.1 (42) | 15.8 (3) | 28.7 (39) | ||

| CMV serostatus | |||||||

| CMV at study baseline, % (n) | 50.7 (136) | ||||||

| CMV at study endpoint, % (n) | 57.8 (155) | ||||||

Age and follow‐up duration are summarised by mean (SD).

Tested between serostatus groups.

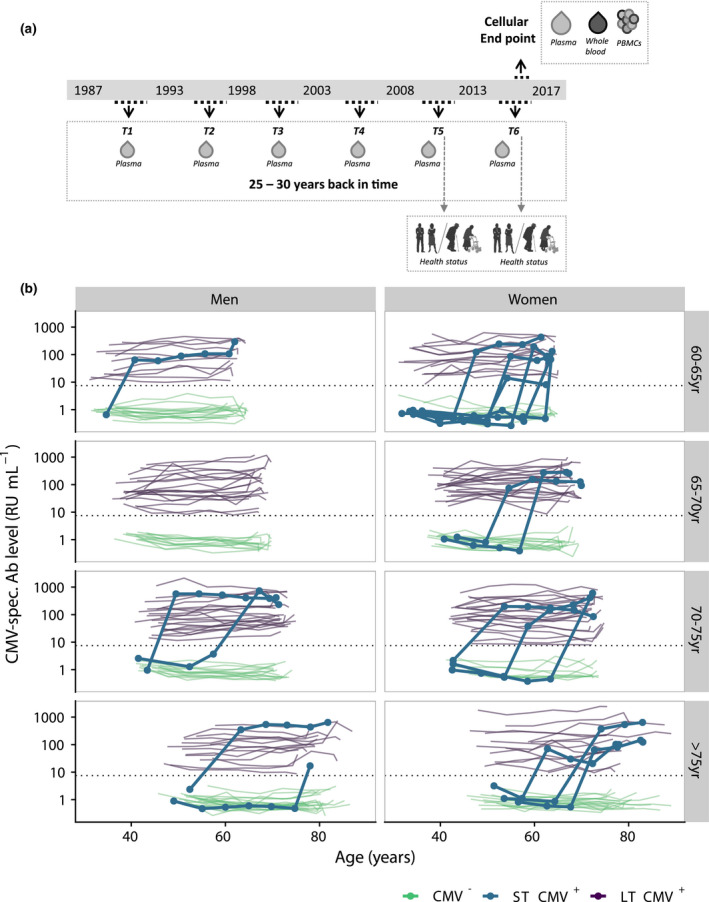

Figure 1.

Overview of the CMV antibody levels of all participants during time. (a) Study design. Participants (n = 135 men, n = 133 women) donated blood 6 times in ~ 27 years. In 2016–2017, an extra sample was taken for extensive phenotyping of leucocyte subsets. (b) CMV antibody levels were measured every 5 years and presented per age category at study endpoint separately for men and woman. Green lines show the antibody trajectories of CMV‐ participants, purple lines those of LT CMV+ participants, and the bold blue lines those of the participants that seroconverted during follow‐up (ST CMV+ participants). Dotted horizontal line shows the cut‐off value for seropositivity.

The majority of CMV+ individuals were CMV+ during entire follow‐up

The duration of CMV infection in the 155 individuals who were CMV+ at study endpoint was determined by measuring CMV‐specific antibody levels in the preceding 25 years. The vast majority (85.9%, n = 136) of these participants had been CMV+ during the entire follow‐up and are therefore referred to as long‐term CMV+ (LT CMV+). The other CMV+ participants (n = 19; 14 women and 5 men) seroconverted during follow‐up and are referred to as short‐term CMV+ (ST CMV+) (Figure 1b, Supplementary figure 2a). An overview of the CMV‐specific antibody levels over time of all CMV+ participants per 5‐year age category, for men and women separately, is shown in Figure 1b. CMV seroconverters were seen in all age categories and showed a sharp increase in antibody levels from undetectable to positive (Figure 1b). The average CMV‐seroconversion rate was 0.56% per year in this adult population and was higher for women than for men (0.88% versus 0.27% per year, P = 0.03) (Supplementary figure 2b). ST CMV+ individuals did not differ from LT CMV+ individuals in terms of age or educational level (Table 1).

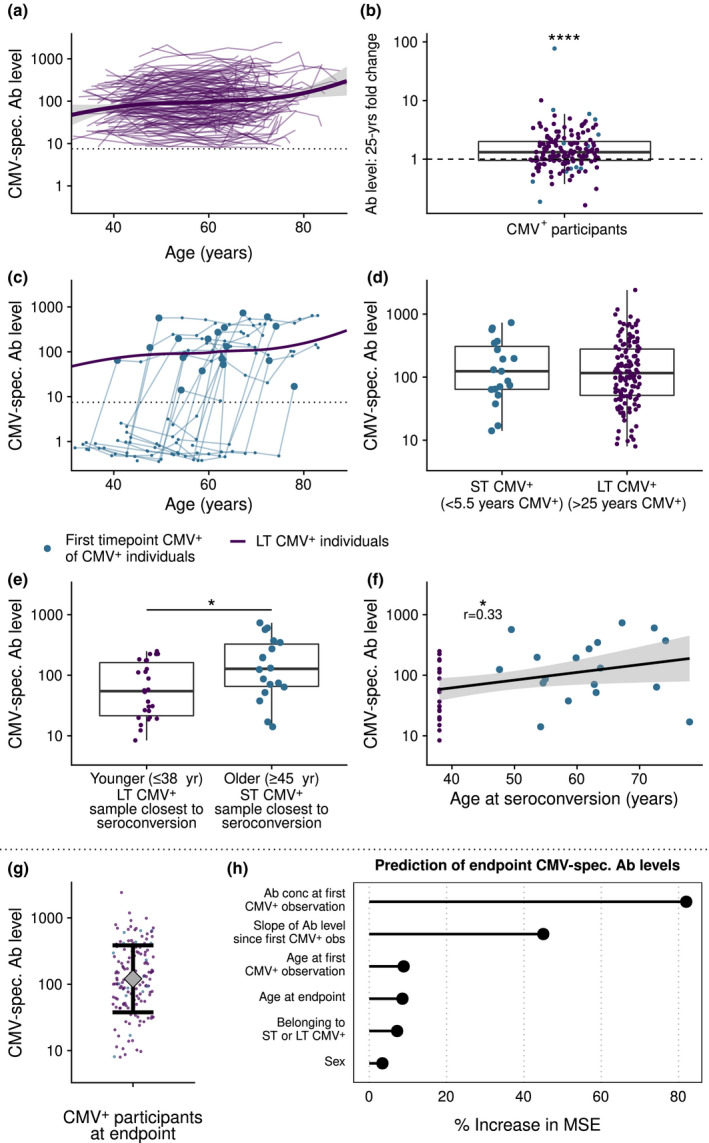

CMV‐specific antibody levels within CMV+ individuals increase over time

We investigated whether CMV‐specific antibody levels increased with age. To this end, we selected samples of all CMV+ participants at all time points. We confirmed data from previous cross‐sectional studies by showing a significant, positive correlation between geomean CMV‐specific antibody levels and age (P < 0.0001, r = 0.15) (Figure 2a, Supplementary figure 3a). We then used a median‐based linear model to estimate the fold change in CMV‐specific antibody levels over time per individual using all available time points. This showed a significant increase in antibody levels within individuals over time. On average, the increase was 1.42 (95% CI: 1.26–1.60) fold in 25 years (P < 0.001), although in some individuals CMV‐specific antibody levels decreased (Figure 2b). Together, these data demonstrate an increase in CMV‐specific antibody levels within CMV+ individuals over time.

Figure 2.

CMV‐specific antibody levels followed over time. (a) Antibody levels of all CMV+ individuals (n = 155). The trend line is based on local polynomial regression through the data of long‐term (LT) CMV+ participants (n = 136). (b) Fold increase in CMV‐specific antibody levels over 25 years for each individual. Dashed line shows no increase or decrease. (c) Individual CMV‐specific antibody levels during time of the CMV seroconverters (n = 19) (blue lines) compared to the average trend line of the long‐term CMV+ individuals. The first CMV+ time point of CMV seroconverters after CMV seroconversion (<5.5 years after CMV conversion) is highlighted by a larger blue dot. (d) Duration of CMV infection: CMV‐specific antibody levels of recently seroconverted individuals (max < 5.5 years after CMV conversion, n = 19) compared with those of long‐term CMV+ individuals (> 25 years CMV+, n = 136). (e) Age at seroconversion: Antibody levels of individuals that seroconverted at younger age (≤ 38 years of age, n = 26) or older age (≥ 45 years of age, n = 18, mean age 58.5 ± 8.1, shortly after CMV seroconversion (max < 5.5 years)). (f) Antibody levels associated with age at CMV seroconversion. For the selection of LT CMV+ individuals, CMV+ individuals of round 1 were included that were ≤ 38 years of age and age of seroconversion was set at 38 years. (g) Antibody levels of all CMV+ individuals at endpoint. Interval represents geometric mean level ± geometric standard deviation. (h) Variable importance when predicting CMV antibody levels at study endpoint with a random forest algorithm. % increase in MSE: proportion increase in mean squared error in the model when a single variable is randomly shuffled. Slope of Ab level: log‐linear variation in CMV‐specific antibody levels after first CMV+ measurement, until time point 6. Boxplots show median with interquartile range. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. The dotted line in a and c is the upper boundary of the cut‐off for CMV seropositivity.

Higher age at CMV seroconversion is positively associated with CMV‐specific antibody levels shortly after seroconversion

We next studied to what extent duration of CMV infection contributes to the correlation between CMV‐specific antibody titres and age, by comparing these in recently infected ST CMV+ individuals (< 5.5 years ago) with the trendline of LT CMV+ individuals (Figure 2c). Antibody levels shortly after seroconversion (< 5.5 years) in ST CMV+ individuals (n = 19) did not differ significantly from those of LT CMV+ individuals (n = 136) (> 25 years CMV‐infected) (Figure 2d); these results were similar in men and women (Supplementary figure 3b). This suggests that CMV‐specific antibody levels do not directly reflect duration of CMV infection. Instead, CMV‐specific antibody levels were related to age, irrespective of the duration of CMV infection. Indeed, CMV‐specific antibody levels of older individuals (> 45 years, range 47–88 years) who seroconverted recently (< 5.5 years ago, n = 18/19 ST CMV+ individuals) were significantly higher than those of younger CMV+ people who seroconverted ≤ 38 years of age, n = 26/116 of LT CMV+ individuals) (P = 0.03, Figure 2e). Similar results were found when age of first seropositive sample was analysed as a continuous variable (correlation P = 0.03, r = 0.33) (Figure 2f). It should be noted that sex was not equally distributed between the two groups (Table 1) and that when analysed per sex, this association was only significant for men (Supplementary figure 3c). Taken together, our results suggest that the positive correlation between age and CMV‐specific antibody levels is not mainly explained by CMV infection duration. Instead, CMV seroconversion at an older age also leads to higher CMV‐specific antibody levels shortly after seroconversion (Supplementary figure 3d) and suggest that age‐related effects other than duration of CMV infection particularly contribute to the observed increase of CMV‐specific antibody levels with age.

Variation in CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint is largely explained by baseline CMV‐specific antibody levels

Antibody levels at study endpoint showed considerable variation between individuals (Figure 2g). We studied which factors explained these differences using a random forest prediction algorithm. Explained variance in the algorithm to predict CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint was 66%. The most important variable to predict this turned out to be the ‘baseline’ CMV‐specific antibody level, defined as the level at the first CMV+ observation, which was on average 27 years ago in LT CMV+ individuals (Figure 2h). The increase in antibody levels over time was second in ranking of variable importance. Other factors such as age at study endpoint, age at seroconversion, duration of CMV infection, sex (Figure 2h) and educational level (data not shown) were much less predictive of CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint. In conclusion, these data show that baseline CMV‐specific antibody levels 27 years ago are more important than the changes in these levels over the last 27 years to explain the majority of the inter‐individual variation in CMV‐specific antibody levels in the elderly.

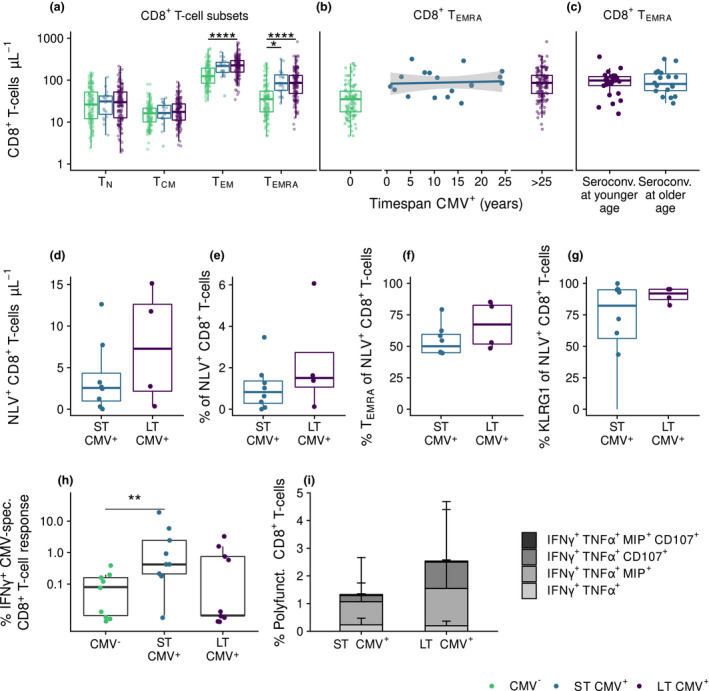

Changes in the CD8+ T‐cell pool are established early after CMV infection

In addition to antibody levels, we investigated the effect of CMV seropositivity and duration of CMV infection on the CD8+ T‐cell pool at study endpoint. Both factors did not affect the total number of naive (TN) or central memory (TCM) CD8+ T cells (Figure 3a). As expected, numbers of effector memory (TEM) and terminally differentiated effector (TEMRA) CD8+ T cells were significantly higher in CMV+ compared to CMV‐ individuals (Figure 3a). This was mainly explained by an increase in the number of late‐stage differentiated (CCR7‐CD45RA+CD27‐CD28‐) CD8+ T cells (data not shown) in CMV+ individuals. No significant association was observed between duration of CMV infection and numbers of TEMRA cells, even within ST CMV+ individuals (Figure 3b). Also, no significant difference was found in CD8+ TEMRA cell numbers at endpoint between individuals who seroconverted at a young age (≤ 38 years of age) and those who seroconverted at an older age (≥ 45 years of age, range 47–88 years) (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

CMV‐induced changes in the CD8+ T‐cell pool are established early after CMV infection. (a) Absolute numbers of CD8+ T‐cell subsets compared between CMV‐ (n = 113), ST CMV+ (n = 19), and LT CMV+ individuals (n = 136). (b) Relationship of duration of CMV infection with CD8+ TEMRA cells numbers. (c) CD8+ TEMRA cells numbers at study endpoint in individuals that seroconverted at younger age (≤ 38 years of age, n = 26) compared to those who converted recently at an older age (≥ 45 years of age, n = 18, mean age 58.5 ± 8.1). (d–g) Numbers and percentages of CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells (d, e), percentage of TEMRA cells of total CD8+ cells (f) and percentage of expression of KLRG‐1 (G) in HLA‐A2 positive individuals for pp65‐epitope NLVPMVATV compared between ST CMV+ (n = 8) and LT CMV+ (n = 4) individuals (g). (h, i) Percentages of IFNγ producing CD8+ T cells (h) and polyfunctional CD8+ T cells producing IFNγ, TNFα, Mip, CD107 and/or IL2 (i) after CMV‐specific peptide stimulation in ST CMV+ and LT CMV+ individuals (n = 27). Boxplots show median with interquartile range. * P < 0.05, **** P < 0.0001.

Next, we investigated whether CMV‐specific CD8+ T‐cell responses differed between ST CMV+ and LT CMV+ individuals (n = 27 in total, matched for age and sex). Based on tetramer staining (using HLA‐class I pp65 NLV epitope) in all HLA‐A2 positive individuals (n = 11), we found no significant differences between ST CMV+ and LT CMV+ individuals in CMV‐specific CD8+ T‐cell numbers (Figure 3d), percentages of CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T‐cell pool (Figure 3e), percentages of TEMRA cells in the CMV‐specific T‐cell pool (Figure 3f), and expression of the senescence marker KLRG‐1 of the CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells (Figure 3g). Also, after CMV‐specific stimulation using overlapping CMV peptide pools, no significant differences were observed in IFNγ production between ST CMV+ and LT CMV+ participants (Figure 3h). We also studied the polyfunctionality of the CMV‐specific T‐cell response and identified that CMV‐specific CD8+ T‐cell responses were mainly IFNγ+TNFα+MIP‐1β+CD107a+ but lacked IL‐2 (Supplementary figure 4a,b), suggestive of an end‐stage highly functional T‐cell phenotype. The percentage of polyfunctional CMV‐specific CD8+ T cells seemed somewhat higher in LT CMV+ compared to ST CMV+ individuals (Figure 3i), but this result was not statistically significant (P = 0.63). This suggests that high CD8+ TEM and TEMRA cell numbers are induced shortly after primary CMV infection and that CMV‐specific T‐cell numbers, phenotype and polyfunctionality are not affected by long‐term CMV infection.

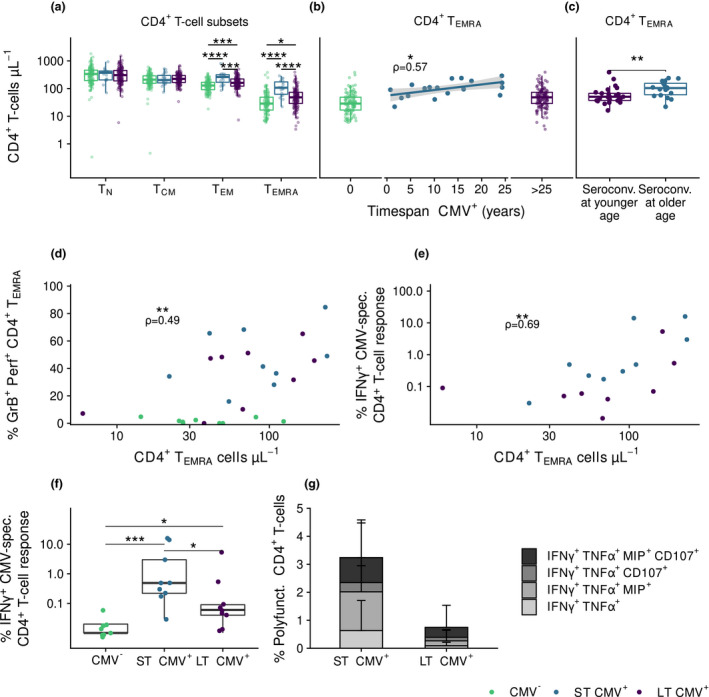

Changes in the CD4+ T‐cell pool are established early after CMV infection and are most pronounced in older CMV seroconverters

We also studied the impact of duration of CMV infection on the CD4+ T‐cell pool by comparing CD4+ T cells at endpoint between ST CMV+ individuals and LT CMV+ individuals. CMV seropositivity was associated with higher numbers of TEM and TEMRA CD4+ T cells (Figure 4a).This was mainly due to the presence of relatively high numbers of intermediate and late‐stage differentiated TEM and TEMRA cells. The higher CD4+ TEM and TEMRA numbers in ST CMV+ individuals were not related to sex or age at endpoint (data not shown). Within the group of ST CMV+ individuals, we found a positive correlation between duration of CMV infection and CD4+ TEM and TEMRA cell numbers at study endpoint (Figure 4b). Similar results were observed for the differentiation states of TEM and TEMRA cells (data not shown). Since ST CMV+ individuals were significantly older at CMV seroconversion than LT CMV+ individuals (average of 57 years and a maximum of 43 years, respectively, P < 0.0001), the higher CD4+ TEM and TEMRA numbers in ST CMV+ individuals may be driven by differences in age at seroconversion. Indeed, individuals who seroconverted at an older age (≥ 45 years old, n = 18/19) had significantly higher CD4+ TEM and TEMRA cell numbers at endpoint than individuals who seroconverted when they were younger than 38 years of age (n = 26/116 LT CMV+ individuals, P = 0.018 and P = 0.006, respectively, Figure 4c). However, within the group of ST CMV+ individuals, age of seroconversion was not significantly related to CD4+ TEM or TEMRA cell numbers (data not shown), possibly due to the smaller age range. Together, these results suggest that duration of CMV infection has only a minor effect on CMV‐induced CD4+ TEM and TEMRA cell numbers and that becoming CMV+ at an older age leads to higher CD4+ TEM and TEMRA numbers at endpoint.

Figure 4.

CMV‐induced changes in the CD4+ T‐cell pool are established early after CMV infection and are most pronounced in older CMV seroconverters. (a) Absolute numbers of CD4+ T‐cell subsets compared between CMV‐ (n = 113), ST CMV+ (n = 19), and LT CMV+ (n = 136) individuals. (b) Relationship of duration of CMV infection with CD4+ TEMRA cells numbers. Correlation in ST CMV+ individuals is indicated by ρ‐ and P‐values. (c) CD4+ TEMRA cells numbers at study endpoint between individuals that seroconverted at younger age (≤ 38 years, n = 26) or older age (≥ 45 years, n = 18, mean age 58.5 ± 8.1). (d, e) Correlation of CD4+ TEMRA cells numbers with their percentages producing granzyme B and perforin (D) and IFNy (e) after CMV peptide stimulation (n = 27). (f, g) Percentages of CD4+ T cells producing IFNγ (f) and being polyfunctional producing IFNγ, TNFα, Mip‐1β, CD107 and/or IL2 (G) after CMV‐specific peptide stimulation in CMV‐, ST CMV+ and LT CMV+ individuals. Boxplots show median with interquartile range. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001.

We further investigated the functionality of the CMV‐specific CD4+ T cells of ST CMV+ and LT CMV+ individuals. CD4+ TEMRA cell numbers at study endpoint correlated positively with the percentage of granzyme B+ and perforin+ TEMRA T cells (Figure 4d) and with the CMV‐specific IFNγ response after stimulation with overlapping CMV peptide pools (UL55, pp65 and IE‐1) (Figure 4e), suggesting that CD4+ TEMRA cells have cytotoxic potential and are responding to CMV by cytokine production. After stimulation of CD4+ T cells with overlapping CMV peptide pools, ST CMV+ individuals showed higher IFNγ‐production than LT CMV+ participants (Figure 4f). CD4+ CMV‐specific T‐cell responses were often polyfunctional, producing IFNγ, TNFα, MIP‐1β and CD107 but not IL‐2, suggestive of an end‐stage highly functional T‐cell phenotype. A trend of possible higher percentages of these cells was found in ST CMV+ compared to LT CMV+ individuals (Figure 4g, Supplementary figure 4c). This was mainly due to the fact that ST CMV+ individuals had significantly higher polyfunctional responses to peptide pool UL55 than LT CMV+ individuals (data not shown). These results suggest that many of the CD4+ TEM and TEMRA cells in CMV‐infected individuals are CMV‐specific T cells with a polyfunctional late‐stage memory phenotype and that these cells are induced early after primary CMV infection. In addition, these cells are induced in higher numbers in individuals who became CMV infected at an older age.

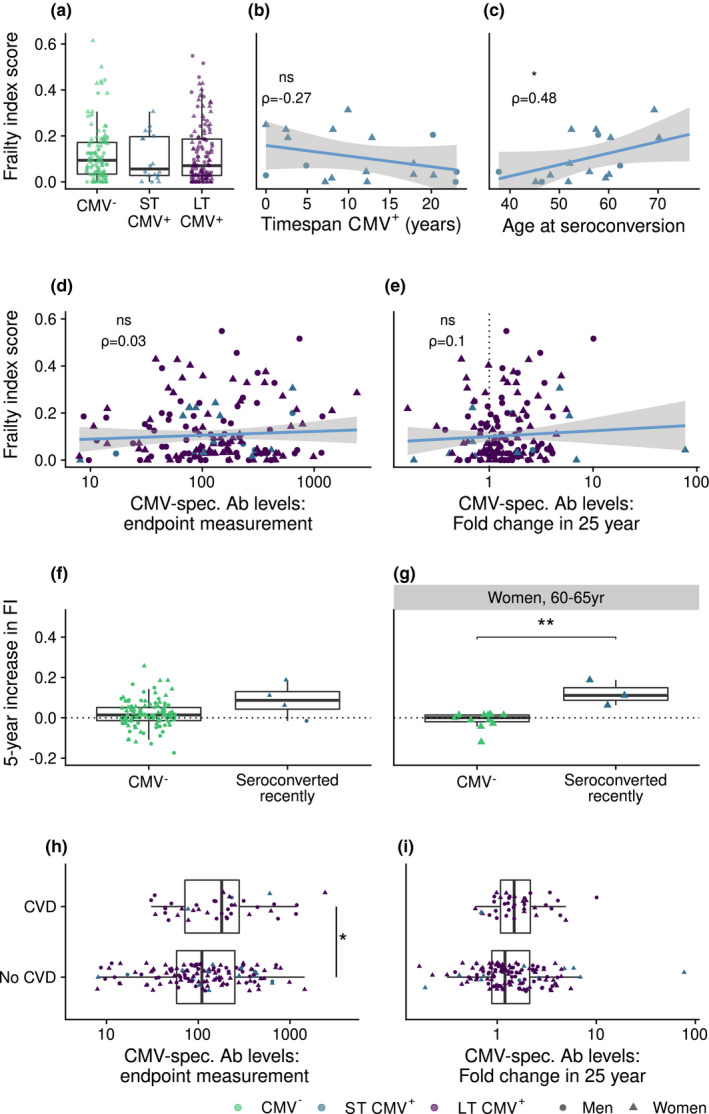

CMV seroconversion at an older age, rather than duration of CMV infection, is associated with frailty

To elucidate potential health consequences of CMV infection, we investigated whether CMV infection and specifically duration of CMV infection were related to a frailty index score. The median frailty index score of all participants was 0.069 at round 5 (Inter Quartile Range (IQR) 0.027–0.167) and 0.081 (IQR 0.029–0.186) at round 6, indicating that on average frailty increased with age (P < 0.001). Median increase in frailty index was 0.013 (IQR −0.017–0.049) (P < 0.001) (Supplementary figure 5). We found no significant differences in frailty between CMV−, ST CMV+, or LT CMV+ individuals (Figure 5a). We observed a non‐significant negative trend between frailty and duration of CMV infection within ST CMV+ participants (n = 19) (P = 0.098, ρ = −0.27 Figure 5b). Interestingly, within the group of ST CMV+ individuals, older age at CMV seroconversion was associated with a higher frailty index (P = 0.03, ρ = 0.48) (Figure 5c), although the trend was not significant after adjusting for age (P = 0.11, ρ = 0.39). We further studied whether CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint or the increase of CMV‐specific antibodies per year were associated with frailty. None of these two indicators were significantly associated with frailty (Figure 5d, e). The median increase in frailty index tended to be higher in recent CMV seroconverters (i.e. converted after DCS round 5), although the effect was not significant (P = 0.11, Figure 5f; n = 4 participants who seroconverted recently). When restricting this analysis to women aged 60–65 years, because 3 out of 4 were women in this age category, we observed that women who seroconverted recently had a higher increase in frailty index than their CMV‐ peers (P = 0.006) (Figure 5g). Although the sample size of ST CMV+ individuals was very small, these unique human data suggest a relationship between becoming infected with CMV at an older age and frailty. Together, these results suggest that, in older individuals, there is no significant association between CMV seropositivity, duration of CMV infection or CMV‐specific antibody levels and frailty, but age of seroconversion might be associated with frailty, and recent CMV seroconversion with an increase in frailty.

Figure 5.

CMV infection is not associated with frailty, but is related to prevalence of cardiovascular disease. (a) Comparison of frailty index score between CMV‐ (n = 110), short‐term (ST) CMV+ (n = 18) and long‐term (LT) CMV+ (n = 132) participants with available frailty index score data at time point T6. (b, c) The relation of frailty with (b) the duration of CMV infection (n = 18) and (c) age of seroconversion in ST CMV+ individuals (seroconverted before frailty index score assessment, n = 16). (d, e) Relationships are shown, respectively, between frailty and CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint (d) and between frailty and fold change in CMV‐specific antibody levels over 26 years (e). (f, g) Difference in increase in frailty index between CMV‐ participants (n = 110) and those who seroconverted recently after measurement point T5 (n = 4) (f) and between women aged 60–65 years that were CMV‐ (n = 11) or converted recently after T5 (n = 3) (g). Increase in frailty index: difference between frailty index as measured between T5 and T6. (h, i) Comparison of cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence with CMV‐specific antibody levels (h) and fold change in 25 years (i) in these antibody levels in individuals that were CMV+ at study endpoint (n = 165) (Prevalence of CVD is indicated in Table 2). Boxplots show median with interquartile range.

CMV‐specific antibody levels are increased in CMV+ individuals with cardiovascular disease

We focused on the relation of CMV infection with the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Of all participants, 20.9% (n = 56) had any form of CVD (Table 2), and most of them were men (n = 38, χ2 = 8.9, P = 0.003). The percentage of individuals with any form of CVD tended to be higher in CMV+ than in CMV‐ individuals (23.6% versus 14.3%, Table 2) (χ2 = 5.3, P = 0.02, analysis stratified by sex as confounder). Furthermore, the occurrence of CVD was positively associated with CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint (P = 0.04 Figure 5h). Although in the group with CVD the median increase in CMV‐specific antibodies seemed higher, no significant difference was observed (P = 0.12 Figure 5i). Within the ST CMV+ group, 3 out of 19 individuals had any form of CVD, a number too low to investigate a possible association between CVD and duration of CMV infection. In conclusion, CMV‐specific antibody levels in CMV+ individuals might be related to the occurrence of CVD.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular disease prevalence

| CMV− | CMV+ | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular intervention | 9.2% (n = 11) | 12.7% (n = 21) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.4% (n = 4) | 9.1% (n = 15) |

| Stroke | 1.7% (n = 2) | 1.8% (n = 3) |

| Total | ||

| Any cardiovascular disease | 14.3% (n = 17) | 23.6% (n = 39) |

Serostatus is serostatus at study endpoint. Cardiovascular intervention: participant undergone either bypass surgery, cardiac valve dilation surgery, cardiac catheterisation, pacemaker placement, or peripheral vascular surgery.

Discussion

We investigated how duration of CMV infection was related to CMV‐specific antibody levels, T‐cell numbers, CMV‐specific T‐cell responses, frailty and cardiovascular disease prevalence. We demonstrated that within individuals, CMV‐specific antibody levels increased over time, albeit only slightly. Nevertheless, duration of CMV infection was not the major determinant of CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint, but the baseline level of 27 years ago turned out to play an important role and the level shortly after seroconversion is influenced by age at seroconversion. Duration of CMV infection was not related to the size and function of the memory CD8+ T‐cell pool, suggesting that CD8+ T‐cell memory responses do not further inflate over time. In contrast, CD4+ T‐cell numbers, similar to CMV‐specific antibody levels, were higher in individuals who seroconverted at an older age. Furthermore, we did not find an association of frailty with CMV serostatus or with duration of CMV infection in elderly individuals, although higher CMV‐specific antibody levels were associated with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease.

We are the first showing the CMV‐seroconversion rate in an observational longitudinal cohort of healthy older adults. The average seroconversion rate that we found (0.56% per year) was similar to a previous estimate based on a large cross‐sectional study in adults (0.55% per year). 33 Thus, this provides a valuable estimate, although it is lower than that previously reported for individuals at high risk due to frequent contact with children like pregnant women, day‐care providers and parents with young children (2.3%, 8.5% and 2.1%, respectively). 34 , 35 Of note is that, although the numbers are small, more women than men seroconverted during follow‐up, possibly due to a higher exposure of women to CMV infection in our cohort. This is in line with a previous study in the general Dutch population, which showed higher seroprevalence of CMV infection in women than in men, 5 and with estimations by a transmission model showing higher CMV incidence in women. 3 Also, sex‐specific differences in immune cell numbers and immune functioning have been described previously, with CMV infection possibly playing a role 36 and women generally showing a stronger immune response. 37 , 38 These sex differences are thought to have a hormonal or genetic aetiology 39 and should be investigated more extensively in future studies.

Higher CMV‐specific antibody levels in older adults are generally thought to reflect multiple experienced CMV reactivations during life. 2 , 3 , 9 , 11 , 22 However, little is known about how CMV‐specific antibody levels are established and maintained during a lifetime in healthy individuals. We observed an increase in CMV‐specific antibody levels over a substantial period of time (~27 years). One other study reported an increase in CMV‐specific antibody levels over time 40 and another did not, 41 but these studies covered a much shorter follow‐up time (5 years and 13 years, respectively). The increase in CMV‐specific antibody levels we observed over time suggests that CMV reactivation, and probably to a lesser extent reinfection, 3 indeed occurs in CMV‐infected individuals. Antibody levels can be stable over prolonged periods of time as has been seen for other viruses. 42 The persistence of CMV antigen could play a role in maintaining CMV‐specific antibody levels. CMV antigen may contribute to activation of memory B cells and the continuous replenishment of long‐lived plasma cells and antibody production. 42 , 43 , 44 Importantly, we show that CMV‐specific antibody levels between individuals (as reflected by the baseline antibody levels) are more important than changes in the antibody levels over the preceding years to predict CMV‐specific antibody levels at endpoint. These results argue against the use of CMV‐specific antibody levels as a surrogate marker for experienced CMV reactivation. Interestingly, while CMV‐specific antibody levels were positively associated with age, they did not differ significantly between ST and LT CMV+ individuals at endpoint. Moreover, age, regardless of duration of CMV infection, was associated with increased CMV‐specific antibody levels. Thus, several age‐related effects are related to CMV‐specific antibody levels later in life.

Memory inflation, characterised by an expansion of the memory T‐cell pool over time, is a hallmark of CMV infection, especially shown in CMV mouse models. 23 , 45 , 46 Memory inflation of CMV‐specific T cells in humans was questioned recently. 47 Longitudinal studies in humans are very limited, and some report evidence for memory inflation, 40 , 48 while others do not. 49 , 50 Our study allowed us to investigate how duration of CMV infection influences the T‐cell memory pool in humans. We show that polyfunctional CMV‐specific T‐cell responses and numbers of memory/effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are already high shortly after CMV seroconversion. Thus, both the humoral immune response and the CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cell pools do not require a long duration of CMV infection to develop and expand. We found weak evidence for memory inflation in the CD4+ T‐cell pool, as duration of CMV infection correlated positively with CD4+ TEM and TEMRA numbers in ST CMV+, but not in LT CMV+ individuals. Although in mouse studies memory inflation was shown to occur only for IE1 derived epitopes, 22 in humans it was more clearly observed for pp65 epitopes. 40 Therefore, we used multiple epitopes in our study. Both functional analysis of CMV‐specific T cells targeting IE1 and/or pp65 epitopes as well as tetramer analysis of T cells specific for the immunodominant pp65 epitope showed somewhat higher values in LT CMV+ than in ST CMV+ individuals, but effect sizes were small and variation too large for these differences to be statistically significant (Figure 3d‐g, I, P > 0.2). For the tetramer analysis, it should be noted that the sample size was small (n = 11) since not every participant was of type HLA‐A2. Regardless of duration of CMV infection, we found a positive correlation between CMV seroconversion at an older age and CD4+ TEM and TEMRA cell numbers, similar to what we observed for CMV‐specific antibody levels. An explanation could be that older individuals, compared to younger ones, need more CD4+ memory T cells to control the virus because their CD4+ memory T‐cell function is impaired, or because they have a higher latent viral load due to delayed (primary) control of the virus. Taken together, our data contribute to the view that there is no evidence for a time‐dependent memory inflation during CMV infection in humans. Further longitudinal studies on T‐cell responses also including cytotoxicity and covering even longer periods of time might strengthen our results.

We also assessed whether prolonged CMV infection might impair clinically relevant health outcomes. We did not find an association between frailty and CMV seroprevalence, or between frailty and duration of CMV infection, with frailty expressed by a frailty index score. 51 This is in line with some other papers, 29 although several studies showed a relation between CMV infection or CMV‐specific antibody levels and frailty 11 , 27 , 28 or even the opposite relationship with a higher CMV seroprevalence in healthy people. 30 Not observing a relationship between frailty and CMV seroprevalence or CMV‐specific antibody levels in our study could be due to the heterogeneity between individuals with a high frailty index score, since a frailty index based on Rockwood criteria contains various conditions and deficits (n = 36). Importantly, another study that used a Rockwood‐based frailty index also did not observe an effect of CMV seropositivity on frailty. 29 Moreover, our study was performed in a younger population (60–89 years old) than the populations in the two other studies not showing a relation between CMV and frailty (> 80 years old), with the latter two studies possibly more obscured by survival bias than ours. Also, the frail population in our study was overrepresented due to the stratified selection, which generally increases the chance of finding an association with frailty, emphasising the negative relation we found. In sum, our study does not support the hypothesis that CMV causes ‘accelerated ageing’ influencing general health. However, we found a possible association between frailty and age at first seropositive time point during follow‐up within ST CMV+ individuals. In addition, a small sub‐group of women who seroconverted recently (after round 5, n = 3) had a steeper increase in frailty index than those who did not seroconvert, which might suggest that people who become frail are more susceptible to CMV infection.

As the effects of CMV might be related to specific chronic conditions and not to a general health state such as frailty, we investigated the association of CMV infection with cardiovascular disease (CVD). Indeed, in line with previous studies, 52 , 53 the prevalence of CVD was significantly higher in CMV+ individuals. Furthermore, within CMV+ individuals, prevalence of CVD was associated with higher CMV‐specific antibody levels at endpoint. One of the mechanisms that could explain this association is that the lytic viral CMV lifecycle in endothelial cells induces vascular damage and therefore contributes to CVD 54 , 55 and in particular to atherosclerosis. 56 Alternatively, progressive endothelial damage in individuals with CVD and a pro‐inflammatory environment could also initiate inflammation leading to CMV reactivation. 1

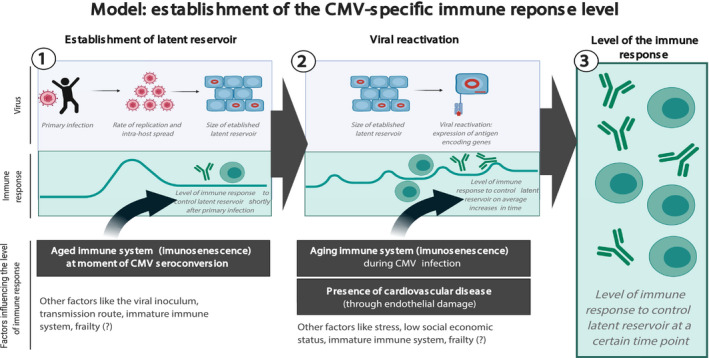

We show that age‐related effects other than duration of CMV infection seem to contribute to the variation in CMV‐specific immune responses at study endpoint between individuals. We hypothesise that this variation between individuals is due to individual differences in the balance between virus and host factors and that these immune responses may in part be determined by viral reactivation, but for the larger part by the establishment of the latent CMV reservoir after primary infection (Figure 6). Due to immunosenescence at higher age, older individuals may be less able to control primary infection and viral spread. This may lead to a larger viral reservoir in the elderly and consequently to a larger immune response to enable control of the virus in its latent phase, regardless of duration of CMV infection. Other factors that could influence this balance include the route of viral transmission, 57 the amount of viral inoculum during primary infection, 23 or the state of the immune system at primary infection. 45 , 58 A comparable model was previously proposed based on data from children, which suggested that the relatively immature state of the immune system in children leads to the establishment of a larger viral reservoir, 45 , 58 which may subsequently increase the chance of viral reactivation. The state of the immune system at primary CMV infection might thus affect the levels of life‐long immunity to CMV (Figure 6). Whether general health status, that is frailty, also enhances the establishment of the latent CMV reservoir and subsequent viral reactivation remains to be investigated.

Figure 6.

Model of establishment of the size of the immune response to control latent CMV infection. Both establishment of the viral latent reservoir after primary infection (1) and the subsequent viral reactivation in time (2) will affect the CMV‐specific immune response. Different factors may influence both phases; those based on our data are presented in black rectangles. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

In conclusion, our results indicate that age, regardless of duration of CMV infection, has a larger influence on the CMV‐specific response than previously anticipated. High CMV‐specific antibody levels should therefore not be interpreted as a measure of experienced viral reactivation or duration of CMV infection. In fact, elderly individuals with high CMV‐specific antibody levels and high numbers of CMV‐specific TEMRA cells could also be the ones who were more recently infected with CMV. While we confirmed that CMV infection is related to cardiovascular disease, we found limited evidence for a relationship with general health, that is frailty. We therefore propose an alternative hypothesis that high CMV‐specific immune responses in the elderly may not be a cause of poor health outcomes, but may instead be a sign of impaired health status.

Methods

Study design

This study was performed with a selected group of participants from the longitudinal Doetinchem Cohort Study (DCS), 31 , 32 which we refer to as the DCS subcohort (n = 289). Individuals have been followed as part of the DCS since 1987, with assessments every five years, resulting in six measurement rounds (1987–1992, 1993–1997, 1998–2002, 2003–2007, 2008–2012, and 2013–2017). Every round, blood plasma samples were taken and stored. The selection of the DCS subcohort has been described. 51 Briefly, all active DCS participants 60–89 years of age (n = 289) were randomly stratified by sex, age and a frailty index score (see below), leading to a selection of equal numbers of men and women, distributed evenly over the included age range and over three frailty groups (healthy, intermediate and frail). The participants were invited for an additional blood sample between October 2016 and March 2017, which was not only used to retrieve plasma, but also to perform immune cell phenotyping on fresh whole blood and to store PBMCs. (Figure 1a). Furthermore, at rounds 5 and 6, the participants’ frailty index was determined, as a measure of general health. For most individuals, the additional blood sample taken for the DCS subcohort was the endpoint of study, and for some (n = 55), endpoint sampling was some months later (round 6). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht. All participants gave written informed consent for every blood sample separately.

Exclusion criteria

From the original 289 participants, individuals were excluded from the longitudinal analyses if their follow‐up time was less than 25 years (n = 17) (Supplementary figure 1), or because of an inconclusive CMV serostatus (n = 4). Thus, the results are based on 268 individuals with an average follow‐up time of 27.7 years (25–30 years). For analyses with cardiovascular disease prevalence, the individuals with follow‐up time < 25 years were included.

Frailty index

The frailty index used has been validated in the DCS 51 and was based on 36 ‘health deficits’. The concept of this index was based on previous studies 29 , 59 , 60 , 61 and was adapted for and validated in the DCS. The index is a variable with values between 0 and 1, 0 representing the ‘best’ and 1 representing the ‘worst’ health status. It has been calculated for each individual based on the data collected during the DCS measurements of round 5 and round 6 (missing n = 1 for round 5 and n = 8 for round 6). The increase in frailty index was defined as the difference between the frailty indices assessed in rounds 5 and 6.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)‐specific antibodies

CMV‐specific IgG antibody levels were measured in plasma by a multiplex immunoassay developed in‐house. 62 A cut‐off of 5 arbitrary units (AU) mL−1 was shown to discriminate best between CMV‐ and CMV+ study groups. 63 To decrease the chance of false‐positive results, antibody levels close to 5 AU mL−1 (i.e. between 4 and 7.5) were considered inconclusive. To reduce intra‐assay variation, all samples from the same individual were measured on the same plate.

Cell numbers by flow cytometry

Fresh whole blood samples collected in 2016–2017 were used to quantify cell numbers of T‐cell subsets by flow cytometry, as previously described. 63 Briefly, absolute cell numbers were determined using TruCOUNT tubes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), in which whole blood was stained with CD3(UCHT1)‐BV711 (BD Biosciences). Another tube was used with the following antibodies: CD3(UCHT1)‐BV711, CD8(SK1)‐APC‐H7, CCR7(150503)‐PECF594, CD27(M‐T271)‐BV421, CD28(CD28.2)‐PerCPCy5.5 (all BD Biosciences), CD4(RPA‐T4)‐BV510, and CD45RA(HI100)‐BV650 (all BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Samples were measured on a flow cytometer (Fortessa X20, BD Biosciences). Absolute cell numbers were calculated by using the bead count of the TruCOUNT tube and the CD3+ T‐cell count of both tubes. T‐cell subsets of naive (TN), central memory (TCM), effector memory (TEM) and effector memory re‐expressing CD45RA (TEMRA) were defined based on the expression of CD45RA and CCR7, after which TEM and TEMRA cells were categorised as early, intermediate and late differentiated based on the expression of CD27 and CD28. 36 , 64

PBMC isolation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained by Lymphoprep (Progen, Wayne, PA, USA) density gradient centrifugation from heparinised blood, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were washed with PBS medium containing 0.2% FCS (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and frozen in a solution with 90% FCS and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide at −135°C until further use.

CMV‐specific functional T‐cell analysis

CMV‐specific T‐cell responses were analysed in a subpopulation (n = 30): 10 CMV+ individuals with the shortest duration of CMV infection for whom PBMCs were available, 10 CMV‐ individuals matched for age and sex only, and 10 long‐term CMV+ individuals based on matched CMV‐specific antibody levels. Cryopreserved PBMCs were rapidly thawed at 37°C and washed in AIM‐V (Gibco, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) 2% human AB serum medium (AIM‐V 2% hAB). The cells were resuspended in AIM‐V 2% hAB and rested at 37°C at 5% CO2 for 30 min before dispending in 106 PBMCs/150 µL per well in a 96‐well plate stimulated with anti‐CD107a PerCP‐Cy5.5, Monensin (1:1500) (GolgiStop, BD Biosciences) and Brefeldin A (1:1000) (GolgiPlug, BD Biosciences). Stimulation for CMV‐specific responses was done using one of the CMV overlapping peptide pools (15‐mers with 11 overlap) of UL55 (1μg mL−1), IE‐1 (1 μg mL−1) or pp65 (1 μg mL−1) (JPT peptide, Berlin, Germany). Medium was used as negative control. Following 6‐hour incubation, cells were washed and stained with the extracellular markers Fixable Viability Staining‐780 (Thermo Fisher), CD3(UCHT1)‐FITC, CD8(RPA‐T8)‐BV510, CD4(SK3)‐BUV737, CD45RO(UCHL1)‐BUV395, and CD107a(H4A3)‐PerCP‐Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences), and CD27(O323)‐BV785 (BioLegend). Next, cells were washed in FACS buffer and twice in perm/wash buffer (fix/perm kit BD, diluted 10x in MilliQ H2O). Intracellular staining was performed with IFNγ(4S.B3)‐PE‐Cy7 (Thermo Fisher), TNFα(MAb11)‐BV711 (BioLegend), IL‐2(MQ1‐17H12)‐BV650, Perforin(B‐D48)‐BV421, MIP‐1β(D21‐1351)‐AlexaFluor700, and Granzyme B(GB11)‐PE‐CF594 (BD Biosciences). Cells were subsequently washed three times and analysed by flow cytometry (Fortessa X20, BD Biosciences). Results were presented as the sum of the three CMV peptide pools minus the negative control medium.

Quantification of CMV‐specific T cells

CMV‐specific T cells were stained using HLA‐class A2 tetramers specific for the NLV epitope of the CMV protein pp65 in the HLA‐A2+ CMV+ individuals of the selected subpopulation for CMV‐specific functional T‐cell analysis (n = 30). First, HLA‐A2 staining by HLA‐A2(BB7.2)‐V450 (BD Biosciences) was performed on the PBMCs of CMV+ individuals (n = 20) to select all HLA‐A2+ individuals. For the HLA‐A2+ individuals (12/20), tetramer staining was performed for 15 min at room temperature with CMV‐(A*0201/NLVPMVATV)‐APC (Immudex, Fairfax, VA, USA) after which extracellular staining was performed for 20 min at 4°C with Fixable Viability Staining‐780 (APC‐Cy7) (Thermo Fisher), CD3 APC‐R700(SK7)‐AF700(BD) CCR7(150503)‐BrilliantViolet(BV)395 (BD Biosciences), CD8+(RPA‐T8)‐BV510, CD45RO+(UCHL1)‐BV711, CD27(O323)‐BV786, PD‐1(EH12.2H7)‐PerCP‐Cy5.5 (BioLegend) and KLRG‐1(13F12F2)‐PE‐Cy7 (Thermo Fisher). Cells were measured by flow cytometry (Fortessa X20, BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Statistics on CMV‐specific antibody levels were performed by parametric testing on log‐transformed data. Comparison within individuals between two time points was done by paired testing and comparison among different groups by non‐paired testing (the paired t‐test and independent Student’s t‐test or the Mann–Whitney U‐test for non‐normally distributed data). Associations between continuous variables were tested by Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation depending on the distribution of the data. Seroconversion rate was calculated by dividing the number of seroconversion cases by the sum of the total time span until seroconversion or until end of follow‐up of all seronegative persons at baseline. Sex differences in seroconversion rate were tested using a chi‐square test. To estimate the change in CMV‐specific antibody levels over a longer period of time within individuals, we used a median‐based linear model, the Theil–Sen estimator, 65 , 66 , 67 with the R package ‘mblm’. 68 The slopes of the log‐transformed antibody levels with age between all repeated measurements (at least 3 CMV+ time points) were calculated per individual, and the median of the slopes was taken (representing the Theil–Sen estimator). This model is less affected by outliers or by skewed distributions than ordinary least‐squares linear regression. To estimate which variables are important predictors for CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint, we performed a random forest prediction analysis with these levels at study endpoint as dependent variable, using the randomForest R package. 69 The proportion of explained variance was calculated to estimate the prediction accuracy. The importance of the variables to predict CMV‐specific antibody levels at study endpoint was shown in a variable importance plot. Differences in T‐cell subsets between the groups (CMV–, ST CMV+ and LT CMV+) were tested by one‐way ANOVA, and two groups’ comparisons were made using Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Frailty index differences were compared by non‐parametric testing, the Spearman correlation for comparing continuous variables, a Kruskal–Wallis test for comparison between groups, and post hoc analysis for comparison between multiple groups by the Tukey correction. Data were analysed using SPSS statistics 22 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R version 3.6.0 70 with several packages for analysis and visualisation. 71 , 72 , 73

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Leonard Daniël Samson: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing‐original draft; Writing‐review & editing. Sara PH van den Berg: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Validation; Visualization; Writing‐original draft; Writing‐review & editing. Peter Engelfriet: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing. Annemieke MH Boots: Conceptualization; Project administration; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing. Marion Hendriks: Data curation; Investigation; Validation. Lia de Rond: Data curation; Investigation; Validation. Mary‐lène de Zeeuw‐Brouwer: Data curation; Investigation; Validation. WM Monique Verschuren: Resources; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing. José AM Borghans: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing. Anne‐Marie Buisman: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing. Debbie van Baarle: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The Doetinchem Cohort Study is funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Additional funding for the current study was also provided by the Ministry. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The graphical abstract image was created with BioRender.com. We thank Irina Tcherniaeva, Marjan Bogaard‐van Maurik, Ronald Jacobi and Gerco den Hartog for help with the CMV serology and Petra Vissink for the help with the longitudinal samples of the DCS.

References

- 1. Dupont L, Reeves MB. Cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation: recent insights into an age old problem. Rev Med Virol 2016; 26: 75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stowe RP, Kozlova EV, Yetman DL, Walling DM, Goodwin JS, Glaser R. Chronic herpesvirus reactivation occurs in aging. Exp Gerontol 2007; 42: 563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Boven M, van de Kassteele J, Korndewal MJ et al Infectious reactivation of cytomegalovirus explaining age‐ and sex‐specific patterns of seroprevalence. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13: e1005719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wertheimer AM, Bennett MS, Park B et al Aging and cytomegalovirus infection differentially and jointly affect distinct circulating T cell subsets in humans. J Immunol 2014; 192: 2143–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Korndewal MJ, Mollema L, Tcherniaeva I et al Cytomegalovirus infection in the Netherlands: seroprevalence, risk factors, and implications. J Clin Virol 2015; 63: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stowe RP, Peek MK, Cutchin MP, Goodwin JS. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 is associated with cytomegalovirus and age. J Med Virol 2012; 84: 1797–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parry HM, Zuo J, Frumento G et al Cytomegalovirus viral load within blood increases markedly in healthy people over the age of 70 years. Immunity & Ageing: I & A 2016; 13: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Furui Y, Satake M, Hoshi Y, Uchida S, Suzuki K, Tadokoro K. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) seroprevalence in Japanese blood donors and high detection frequency of CMV DNA in elderly donors. Transfusion 2013; 53: 2190–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alonso Arias R, Moro‐Garcia MA, Echeverria A, Solano‐Jaurrieta JJ, Suarez‐Garcia FM, Lopez‐Larrea C. Intensity of the humoral response to cytomegalovirus is associated with the phenotypic and functional status of the immune system. J Virol 2013; 87: 4486–4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turner JE, Campbell JP, Edwards KM et al Rudimentary signs of immunosenescence in Cytomegalovirus‐seropositive healthy young adults. Age 2014; 36: 287–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang GC, Kao WH, Murakami P et al Cytomegalovirus infection and the risk of mortality and frailty in older women: a prospective observational cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171: 1144–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Araujo Carvalho AC, Tavares Mendes ML, Santos VS, Tanajura DM, Prado Nunes MA, Martins‐Filho PRS. Association between human herpes virus seropositivity and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2018; 48: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vescovini R, Biasini C, Telera AR et al Intense antiextracellular adaptive immune response to human cytomegalovirus in very old subjects with impaired health and cognitive and functional status. J Immunol 2010; 184: 3242–3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gkrania‐Klotsas E, Langenberg C, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ. Higher immunoglobulin G antibody levels against cytomegalovirus are associated with incident ischemic heart disease in the population‐based EPIC‐Norfolk cohort. J Infect Dis 2012; 206: 1897–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roberts ET, Haan MN, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Cytomegalovirus antibody levels, inflammation, and mortality among elderly Latinos over 9 years of follow‐up. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172: 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaczorowski KJ, Shekhar K, Nkulikiyimfura D et al Continuous immunotypes describe human immune variation and predict diverse responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114: E6097–E6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weltevrede M, Eilers R, de Melker HE, van Baarle D. Cytomegalovirus persistence and T‐cell immunosenescence in people aged fifty and older: a systematic review. Exp Gerontol 2016; 77: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB et al Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus‐specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 673–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van de Berg PJ, van Stijn A, Ten Berge IJ, van Lier RA. A fingerprint left by cytomegalovirus infection in the human T cell compartment. J Clin Virol 2008; 41: 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klenerman P, Oxenius A. T cell responses to cytomegalovirus. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16: 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pourgheysari B, Khan N, Best D, Bruton R, Nayak L, Moss PA. The cytomegalovirus‐specific CD4+ T‐cell response expands with age and markedly alters the CD4+ T‐cell repertoire. J Virol 2007; 81: 7759–7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klenerman P. The (gradual) rise of memory inflation. Immunol Rev 2018; 283: 99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Redeker A, Welten SP, Arens R. Viral inoculum dose impacts memory T‐cell inflation. Eur J Immunol 2014; 44: 1046–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aiello AE, Chiu Y‐L, Frasca D. How does cytomegalovirus factor into diseases of aging and vaccine responses, and by what mechanisms? Geroscience 2017; 39: 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savva GM, Pachnio A, Kaul B et al Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with increased mortality in the older population. Aging Cell 2013; 12: 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gkrania‐Klotsas E, Langenberg C, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ. Seropositivity and higher immunoglobulin g antibody levels against cytomegalovirus are associated with mortality in the population‐based european prospective investigation of cancer‐norfolk cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 1421–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomasini RL, Pereira DS, Pereira FSM et al Aged‐associated cytomegalovirus and Epstein‐Barr virus reactivation and cytomegalovirus relationship with the frailty syndrome in older women. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0180841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmaltz HN, Fried LP, Xue Q‐L, Walston J, Leng SX, Semba RD. Chronic cytomegalovirus infection and inflammation are associated with prevalent frailty in community‐dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Collerton J, Martin‐Ruiz C, Davies K et al Frailty and the role of inflammation, immunosenescence and cellular ageing in the very old: cross‐sectional findings from the Newcastle 85+ Study. Mech Ageing Dev 2012; 133: 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matheï C, Vaes B, Wallemacq P, Degryse J. Associations between cytomegalovirus infection and functional impairment and frailty in the BELFRAIL cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 2201–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Picavet HSJ, Blokstra A, Spijkerman AMW, Verschuren WMM. Cohort Profile update: the doetinchem Cohort Study 1987–2017: lifestyle, health and chronic diseases in a life course and ageing perspective. Int J Epidemiol 2017; 46: 1751–1751g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verschuren WM, Blokstra A, Picavet HS, Smit HA. Cohort profile: the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2008; 37: 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hecker M, Qiu D, Marquardt K, Bein G, Hackstein H. Continuous cytomegalovirus seroconversion in a large group of healthy blood donors. Vox Sang 2004; 86: 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hyde TB, Schmid DS, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroconversion rates and risk factors: implications for congenital CMV. Rev Med Virol 2010; 20: 311–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2011; 21: 240–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van der Heiden M, van Zelm MC, Bartol SJ et al Differential effects of Cytomegalovirus carriage on the immune phenotype of middle‐aged males and females. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 26892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16: 626–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ortona E, Pierdominici M, Editorial Rider V. Sex Hormones and Gender Differences in Immune Responses. Front Immunol (Editorial) 2019; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gubbels Bupp MR. Sex, the aging immune system, and chronic disease. Cell Immunol 2015; 294: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vescovini R, Telera AR, Pedrazzoni M et al Impact of Persistent Cytomegalovirus Infection on Dynamic Changes in Human Immune System Profile. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0151965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lustig A, Liu HB, Metter EJ et al Telomere Shortening, Inflammatory Cytokines, and Anti‐Cytomegalovirus Antibody Follow Distinct Age‐Associated Trajectories in Humans. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 1903–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wrammert J, Ahmed R. Maintenance of serological memory. Biol Chem 2008; 389: 537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Siegrist CA, Aspinall R. B‐cell responses to vaccination at the extremes of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reddehase MJ. 'Checks and balances' in cytomegalovirus‐host cohabitation. Med Microbiol Immunol 2019; 208: 259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cicin‐Sain L. Cytomegalovirus memory inflation and immune protection. Med Microbiol Immunol 2019; 208: 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jackson SE, Sedikides GX, Okecha G, Wills MR. Generation, maintenance and tissue distribution of T cell responses to human cytomegalovirus in lytic and latent infection. Med Microbiol Immunol 2019; 208: 375–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hosie L, Pachnio A, Zuo J, Pearce H, Riddell S, Moss P. Cytomegalovirus‐specific T Cells restricted by HLA‐Cw*0702 increase markedly with age and dominate the CD8+ T‐Cell repertoire in older people. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jackson SE, Mason GM, Okecha G, Sissons JG, Wills MR. Diverse specificities, phenotypes, and antiviral activities of cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8+ T cells. J Virol 2014; 88: 10894–10908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Abana CO, Pilkinton MA, Gaudieri S et al Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Epitope‐Specific CD4+ T Cells Are Inflated in HIV+ CMV+ Subjects. Journal of immunology 2017; 199: 3187–3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Samson LD, Boots AMH, Verschuren WMM, Picavet HSJ, Engelfriet P, Buisman A‐M. Frailty is associated with elevated CRP trajectories and higher numbers of neutrophils and monocytes. Exp Gerontol 2019; 125: 110674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang H, Peng G, Bai J et al Cytomegalovirus infection and relative risk of cardiovascular disease (Ischemic Heart Disease, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Death): a meta‐analysis of prospective studies up to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6: e005025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lebedeva AM, Shpektor AV, Vasilieva EY, Margolis LB. Cytomegalovirus infection in cardiovascular diseases. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2018; 83: 1437–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van de Berg PJ, Yong SL, Remmerswaal EB, van Lier RA, ten Berge IJ. Cytomegalovirus‐induced effector T cells cause endothelial cell damage. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012; 19: 772–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pachnio A, Ciaurriz M, Begum J et al Cytomegalovirus infection leads to development of high frequencies of cytotoxic virus‐specific CD4+ T Cells targeted to vascular endothelium. PLoS Pathog 2016; 12: e1005832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yaiw K‐C, Ovchinnikova O, Taher C et al High prevalence of human cytomegalovirus in carotid atherosclerotic plaques obtained from Russian patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Herpesviridae 2013; 4: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Farrell HE, Lawler C, Tan CS et al Murine Cytomegalovirus Exploits Olfaction To Enter New Hosts. MBio 2016; 7: e00251–e00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Adler SP, Reddehase MJ. Pediatric roots of cytomegalovirus recurrence and memory inflation in the elderly. Med Microbiol Immunol 2019; 208: 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rockwood K, Song X, Mitnitski A. Changes in relative fitness and frailty across the adult lifespan: evidence from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. CMAJ 2011; 183: e487–e494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schoufour JD, Erler NS, Jaspers L et al Design of a frailty index among community living middle‐aged and older people: The Rotterdam study. Maturitas 2017; 97: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008; 8: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tcherniaeva I, den Hartog G, Berbers G, van der Klis F. The development of a bead‐based multiplex immunoassay for the detection of IgG antibodies to CMV and EBV. J Immunol Methods 2018; 462: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Samson LD, Boots AMH, Ferreira JA et al In‐depth immune cellular profiling reveals sex‐specific associations with frailty. Immunity Ageing 2020; 17: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M et al Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med 2002; 8: 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Theil H. A rank‐invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. Indigationes Mathematicae 1950; 12: 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sen PK. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall's Tau. J Am Stat Assoc 1968; 63: 1379–1389. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wilcox R. A Note on the theil‐sen regression estimator when the regressor is random and the error term is heteroscedastic. Biom J 1998; 40: 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Komsta L. mblm: Median‐based Linear Models, version 0.12.1 ed2019.

- 69. Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002; 2: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 70. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wickham HA, Averick Mara, Bryan Jennifer et al Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 2019; 4: 1686. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wilke CO. cowplot: Streamlined Plot Theme and Plot Annotations for 'ggplot2', version 1.0.0 ed2019.

- 73. Pedersen TL. patchwork: The Composer of Plots, version 1.0.0 ed2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials