Abstract

An activated plasma contact system is an abnormality observed in many Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. Since mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients often develop AD, we analyzed the status of contact system activation in MCI patients. We found that kallikrein activity, high molecular weight kininogen cleavage, and bradykinin levels – measures of contact system activation – were significantly elevated in MCI patient plasma compared to plasma from age- and education-matched healthy individuals. Changes were more pronounced in MCI patients with impaired short-term recall memory, indicating the possible role of the contact system in early cognitive changes.

Keywords: Mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, contact activation, bradykinin, plasma kallikrein, high molecular weight kininogen, memory impairment

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder of multifactorial nature [1], and vascular factors are known to play an important role in its pathogenesis [2]. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), or the deposition of the pathogenic beta-amyloid (Aβ) protein in and around blood vessels, is a vascular abnormality present in 80–95% of AD patients [3]. Other cerebrovascular pathologies present in AD patients include cerebral blood flow alteration, blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, brain hypoperfusion, and leakage of blood proteins into the brain parenchyma [4–6]. For example, fibrinogen, a major blood protein required for clot formation, is extravasated in AD patient brains [7]. It has been shown that Aβ interacts with fibrinogen and alters blood clot structure and impairs clot degradation [8, 9]. Accumulated, persistent fibrinogen in the brain parenchyma induces inflammation and memory impairment [10]. Cerebral perfusion, BBB integrity, and cognition were improved in AD mice treated with dabigatran [11], which prevents fibrin clot formation, emphasizing the involvement of blood proteins in AD pathology [12]. Similar to this study, it has been shown that inhibiting the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction prevents AD pathology in mouse models [13]. Therefore, the interaction between Aβ and fibrinogen may exacerbate cerebral pathologies in AD patients.

The intrinsic blood coagulation pathway is triggered upon activation of factor XII (FXII) of the plasma contact system [14]. In addition to thrombosis, this pathway can promote an inflammatory response. When FXII is activated, kallikrein cleaves high molecular weight kininogen (HK) which thereby releases bradykinin [15, 16]. Aβ aggregates can trigger the contact system by activating FXII [17–19], thus enhancing both of these inflammatory and thrombotic pathways [14, 20–22].

Many AD patient plasma samples show increased levels of activated FXII, kallikrein activity, and HK cleavage [21, 22]. An increase in cleaved HK is positively correlated with dementia and neuritic plaque scores of AD patients [21]. Though contact system activation is not specific to AD [15], this finding indicates that a dysregulated contact system could affect AD pathogenesis and cognitive decline. Furthermore, knockdown of the contact system reduces cerebral inflammation, prevents fibrin extravasation, and improves cognition in AD mice [23].

There is increasing evidence that subtle losses in cognitive function may be an early indication of AD development. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) refers to the transitional stage between the cognitive decline associated with normal aging and mild dementia [24, 25]. MCI patients perform reasonably well on indices of general cognitive function and their ability to carry out daily living activities is largely preserved, yet they do present with other acquired cognitive deficits, such as retrieval of episodic and short-term memory [24]. Many MCI patients progress to AD at a rate of 10% to 15% per year, while healthy control subjects are diagnosed with AD at a rate of 1% to 2% per year [24, 26, 27]. MCI patients often show gray matter loss and synaptic alterations [24, 28, 29], and MCI patients who subsequently progress to AD show hypoperfusion in the posterior cingulate cortex [24, 29, 30]. Furthermore, both MCI and AD patients present with cortical hypometabolism with some regional variability [24, 31, 32]. These findings support the belief that MCI is a risk factor for AD, and, as evidenced by imaging techniques, MCI and AD pathologies share many of the same structural and functional abnormalities.

A common biomarker for MCI and AD could be used to quickly diagnose MCI but would also provide an opportunity to identify those patients progressing to early-stage AD, which would allow for preventive care before severe AD onset. It has been reported that there is a significant alteration in the plasma protein profile of MCI patients who later develop AD, suggesting that plasma proteins could serve as a biomarker for MCI and AD [33, 34].

Here, we analyzed plasma samples from MCI patients and age-matched cognitively normal (CN) individuals and compared the status of contact system activation in both groups. We measured plasma bradykinin level, kallikrein activity, and HK cleavage. Our analysis suggests that the contact system is activated in MCI patients and the extent of activation correlates with impaired short-term recall memory. Our data support the early involvement of an impaired peripheral contact system in MCI and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and Methods

Plasma samples

Experiments using human plasma samples were reviewed and approved by The Rockefeller Institutional Review Board. Plasma from MCI patients and age-matched and education-matched CN individuals were obtained from PrecisionMed Inc. (San Diego, CA). Patients were screened for MCI using criteria developed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) [35]. MCI diagnosis was established by clinical examination, including the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and other neuropsychological tests (clinical dementia rating, CDR; logical memory test II, LM II; Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale cognitive subscale, ADAS-Cog) [36]. All MCI patients had Hachinski score ≤4, indicating no multi-infarcts or vascular dementia [37]. None of the patients whose plasma was included in our study had history of stroke, heart attack, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disease, or pernicious anemia. Other neurological conditions, such as chronic nervous system infection, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease were also absent in this patient cohort. Brain MRI/CT images collected within two years of plasma donation were analyzed to exclude other possible causes of cognitive impairment. Subjects were not on anticoagulant therapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicine, or aspirin within a week of their visit for blood donation. The blood was collected in K2EDTA anticoagulant. The characteristics of MCI and CN individuals are presented in Table 1.

Table1.

Characteristics and demographics of MCI and CN individuals.

| Characteristics | Cognitively normal controls (CN) | Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals, n | 19 | 25 | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | Caucasian | |

| Female, n | 10 (53%) | 16 (64%) | |

| Male, n | 9 (47%) | 9 (36%) | |

| Hachinski score | - | ≤4 | |

| Mini mental state examination (MMSE) score, mean (SD) | 29.84 (0.37) | 25.8 (1.95) | p<0.0001 |

| Registration memory score in MMSE, mean (SD) | 3.0 (0) | 2.64 (0.90) | p=0.092 |

| Recall memory score in MMSE, mean (SD) | 2.89 (0.31) | 0.92 (0.95) | p<0.0001 |

| Clinical dementia rating (CDR) score, mean (SD) | - | 0.52 (0.1) | |

| Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) score, mean (SD) | - | 15 (7.6) | |

| Logical memory II (LM II) score, mean (SD) | - | 12.2 (8.7) | |

| Total years of education, mean (SD) | 15.59 (1.62) | 14.68 (1.81) | p=0.10 |

| Age (year) at blood draw, mean (SD) | 65.79 (5.0) | 65.12 (7.0) | p=0.72 |

| Age at diagnosis | - | 62.83 (7.37) | |

| Disease duration (year), mean (SD) | - | 1.95 (2.33) | |

| Stroke, hypertension, and heart attack status | Not present | Not present | |

| Diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and rheumatoid arthritis status | Not present | Not present |

Plasma bradykinin level and kallikrein activity

Plasma bradykinin level was analyzed by ELISA as described previously [20, 38]. Plasma kallikrein activity was measured as described in [22] with some modifications. Briefly, in a 96-well plate, plasma samples diluted (1:20) in HEPES-buffered saline (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl) were mixed with a chromogenic substrate, S-2302 (0.67 mM final concentration). Absorbance at 405 nm was read for 60 min at 37°C using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). Samples were run in duplicate.

Plasma cleaved HK level and C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) level

The level of plasma cleaved HK was determined using a sandwich ELISA [21]. The monoclonal antibody (4B12) used in this ELISA specifically detects cleaved HK [21]. Plasma was diluted (1:50) in blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin in 0.1% tween-20/PBS), and ELISAs were performed in duplicate as described in [21]. Plasma C1INH level was quantified by ELISA (Abcam) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results and Discussion

Plasma contact system is activated in MCI patients

The contact system is activated in AD patient plasma and correlates with the severity of memory impairment [21, 22]. Increased plasma bradykinin level, kallikrein activity, and HK cleavage are indicators of an activated contact system. Here, we analyzed the bradykinin level in plasma samples from MCI patients and age-matched CN individuals. We found that plasma bradykinin level was significantly increased in MCI patients compared to CN individuals (1590 ± 261.6 pg/mL vs. 967.5 ± 109 pg/mL; p < 0.05). Since bradykinin is generated from HK by active kallikrein [15], we measured the plasma kallikrein activity in MCI and CN groups. We found that plasma kallikrein activity was also significantly elevated in MCI patients compared to that of CN (0.11 ± 0.01 vs. 0.05 ± 0.009; p < 0.01). Kallikrein activity was abolished in MCI plasma when aprotinin, a known kallikrein inhibitor [39], was added to samples (Supplementary Fig.1A).

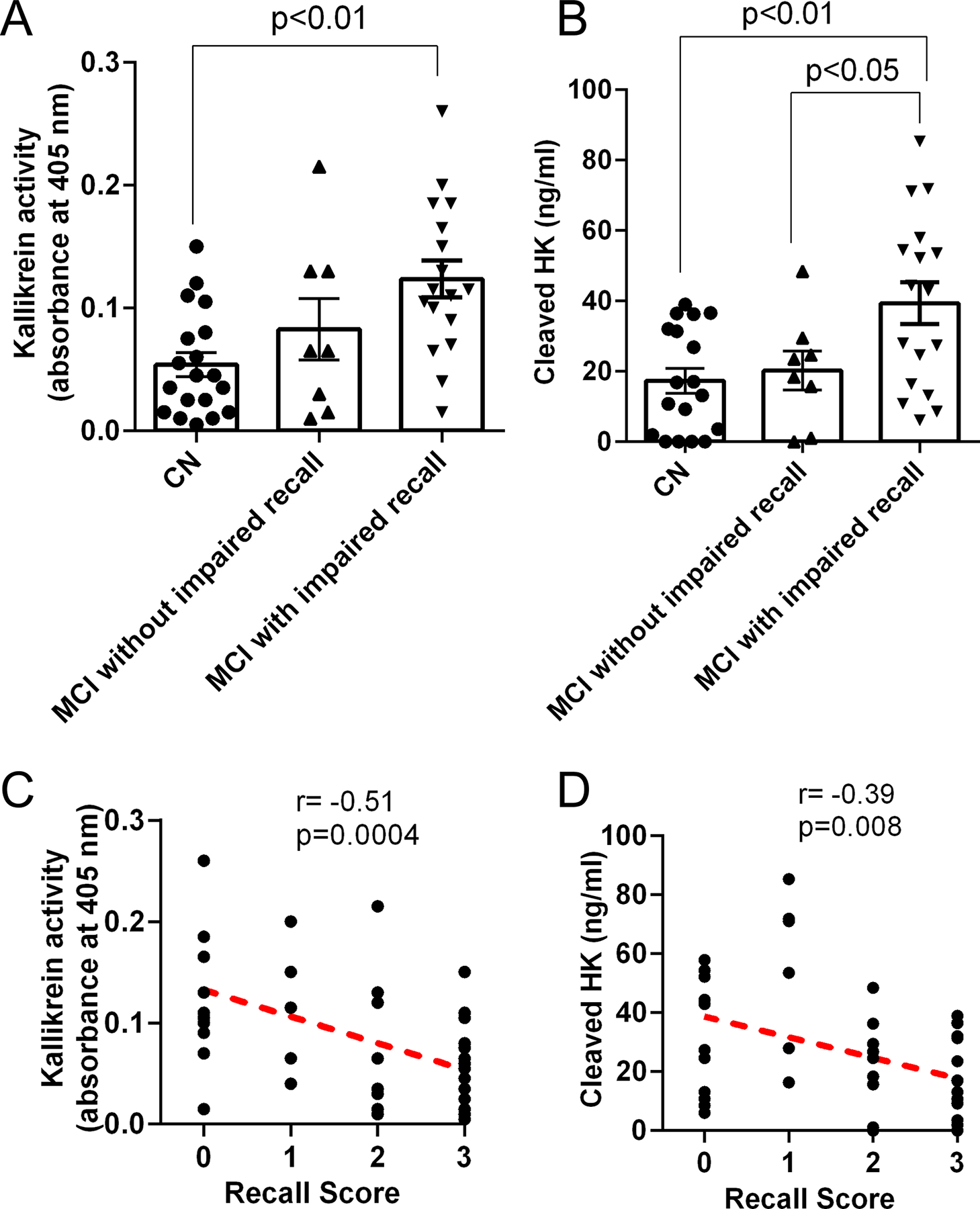

Analysis of MMSE data from MCI patients revealed that many MCI patients performed poorly on recall memory (Table 1). Recall memory is evaluated by giving the test subject a list of three unrelated words, and the subject is asked to recall them after several minutes. The maximum score for recalling three unrelated words in MMSE is 3 [40]. Many MCI patients (11/25) did not recall any of the words (score 0), indicating they had impaired short-term recall memory. Some patients (6/25) recalled one word (score 1). The plasma kallikrein activity of MCI patients with impaired recall (score 0 or 1) was significantly higher than that of CN individuals (0.12 ± 0.01 vs. 0.05 ± 0.009; p < 0.01; Fig. 1A). Plasma kallikrein activity was higher in MCI patients with impaired recall (score 0 or 1) compared to that of MCI patients without impaired recall (8/25; score 2 or 3), though this trend did not reach significance (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Activation of contact system in MCI patient plasma.

Plasma kallikrein activity and cleaved HK levels in plasma from MCI and CN subjects were assessed using chromogenic assay and ELISA, respectively. MCI patients with low recall scores (0 or 1) were grouped as ‘MCI with impaired recall’. MCI patients with higher recall scores (2 or 3) were grouped as ‘MCI without impaired recall’. (A) Plasma kallikrein activity was significantly higher in MCI patients with impaired recall memory compared to that of CN. (B) Plasma cleaved HK levels were significantly higher in MCI patients with impaired recall compared to CN. (C) Plasma kallikrein activity inversely correlates with recall score. (D) Plasma cleaved HK level also inversely correlates with recall score. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Correlation was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Results are presented as mean ± SEM. N= 19 CN, 25 MCI. The difference in cleaved HK level between MCI without impaired recall and MCI with impaired recall was significant by t-test with Welch’s correction.

We also quantified the level of cleaved HK in each patient’s plasma sample, using a sandwich ELISA that differentiates between full-length HK and cleaved HK [21]. Similar to the kallikrein activity results, the ELISA showed that the level of cleaved HK in MCI patients with impaired recall (score 0 or 1) was significantly higher than that of CN individuals (39.31 ± 5.9 ng/mL vs. 20.25 ± 4.4 ng/mL; p < 0.01; Fig. 1B). Cleaved HK levels in plasma from MCI patients with impaired recall were also higher than MCI patients without impaired recall (39.31 ± 5.9 ng/mL vs. 20.15 ± 5.5 ng/mL; p < 0.05 Fig. 1B). This difference was significant when analyzed by an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction but not by one-way ANOVA (Fig. 1B).

The plasma protease, C1INH, negatively regulates contact activation, and a decrease in C1INH levels can trigger kallikrein generation and HK cleavage [15]. It has been reported that the level of plasma C1INH is reduced in MCI patients [41]. However, we did not find any significant difference in plasma C1INH levels between MCI and CN samples (59.9 ± 6.1 μg/mL vs. 49.7 ± 7.1 μg/mL; p=0.28; Supplementary Fig. 1B). Therefore, the increase in contact activation could be due to other mechanisms such as increased plasma Aβ [42], which can activate the contact system [17, 18, 22].

Episodic memory is the ability to recall events that are specific to a time and place [24]. Community-based longitudinal studies have found that the deficits in episodic memory can be found at least five years before the onset of clinical dementia [24, 43]. Episodic memory was also found compromised in MCI patients and linked with hippocampal atrophy [24].

In our patient cohort, no significant differences in memory registration (encoding) were found between MCI and CN groups (Table 1). However, recall memory was significantly impaired in MCI patients compared to CN individuals (Table 1). The recall memory score showed a significant inverse correlation between plasma kallikrein activity and plasma cleaved HK (Fig. 1C and 1D). Recall memory impairment has been also shown to correlate with synaptic alterations and gray matter loss in MCI patients [28, 29]. The posterior cingulate cortex, which contains the neural pathway for recall memory, is metabolically impaired in MCI patients. [24, 29, 44]. Peripheral changes, such as plasma contact system activation, may affect the central nervous system in such ways that ultimately affect recall memory in addition to blood coagulation and inflammatory conditions. For example, it has been shown that cerebral injection of bradykinin in rats affects memory [45]. Since bradykinin has been shown to impair the BBB [46], blood proteins may enter the brain parenchyma and lead to inflammatory processes, cell death, and memory loss. These mechanisms must be explored in more detail.

Peripheral protein and amino acid alterations are associated with cognitive function in MCI patients [33, 34, 41, 47, 48], and peripheral contact activation also correlates well with dementia in AD patients [21, 22]. In this study, we determined that the contact system is also activated in MCI patients and correlates with their recall memory status. A longitudinal study is warranted to evaluate how the contact system fully affects the progression from cognitively normal to stages of MCI and AD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. (A) Aprotinin inhibits kallikrein activity in MCI patient plasma. Kallikrein activity of MCI plasma samples was measured in the presence and absence of aprotinin, a known kallikrein inhibitor. Three representative MCI plasma samples (MMSE recall score-0) were diluted (20-fold) in buffer in the presence and absence of aprotinin (3–7 TIU/mg protein). The kallikrein activity was monitored using the S2302 substrate at 37°C in a spectrophotometer. Aprotinin (from bovine lung) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. (B) Plasma C1INH levels in MCI and CN groups. Plasma samples were diluted in assay buffer (1:300,000), and the ELISA was performed in duplicate. C1INH level was not significantly different between CN and MCI groups (N=19 CN, 25 MCI). Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired t test using GraphPad Prism. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.0001.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr. Sarah Baker and other members of the Strickland laboratory for helpful discussions and valuable suggestions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants NS106668 and NS102721; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 TR001866; Cure Alzheimer’s Fund; Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Rudin Family Foundation; Newhouse Foundation; and Mr. John A. Herrmann, Jr.

References

- [1].Selkoe DJ, Schenk D (2003) Alzheimer’s disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 43, 545–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Strickland S (2018) Blood will out: vascular contributions to Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest 128, 556–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jellinger KA (2002) Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 109, 813–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ryu JK, McLarnon JG (2009) A leaky blood-brain barrier, fibrinogen infiltration and microglial reactivity in inflamed Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Cell Mol Med 13, 2911–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV (2018) Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 14, 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cruz Hernandez JC, Bracko O, Kersbergen CJA-Ohoo, Muse VA-Ohoo, Haft-Javaherian M, Berg M, Park LA-OhooX, Vinarcsik LK, Ivasyk I, Rivera DA, Kang Y, Cortes-Canteli M, Peyrounette M, Doyeux V, Smith AA-Ohoo, Zhou J, Otte G, Beverly JD, Davenport E, Davit Y, Lin CP, Strickland S, Iadecola CA-OhooX, Lorthois SA-Ohoo, Nishimura NA-Ohoo, Schaffer CBA-Ohoo (2019) Neutrophil adhesion in brain capillaries reduces cortical blood flow and impairs memory function in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Neurosci 22, 413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cortes-Canteli M, Mattei L, Richards AT, Norris EH, Strickland S (2015) Fibrin deposited in the Alzheimer’s disease brain promotes neuronal degeneration. Neurobiol Aging 36, 608–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cortes-Canteli M, Paul J, Norris EH, Bronstein R, Ahn HJ, Zamolodchikov D, Bhuvanendran S, Fenz KM, Strickland S (2010) Fibrinogen and beta-amyloid association alters thrombosis and fibrinolysis: a possible contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 66, 695–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zamolodchikov D, Berk-Rauch HE, Oren DA, Stor DS, Singh PK, Kawasaki M, Aso K, Strickland S, Ahn HJ (2016) Biochemical and structural analysis of the interaction between beta-amyloid and fibrinogen. Blood 128, 1144–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Merlini M, Rafalski VA, Rios Coronado PE, Gill TM, Ellisman M, Muthukumar G, Subramanian KS, Ryu JK, Syme CA, Davalos D, Seeley WW, Mucke L, Nelson RB, Akassoglou K (2019) Fibrinogen Induces Microglia-Mediated Spine Elimination and Cognitive Impairment in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Neuron 101, 1099–1108 e1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kopec AK, Joshi N, Towery KL, Kassel KM, Sullivan BP, Flick MJ, Luyendyk JP (2014) Thrombin inhibition with dabigatran protects against high-fat diet-induced fatty liver disease in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 351, 288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cortes-Canteli M, Kruyer A, Fernandez-Nueda I, Marcos-Diaz A, Ceron C, Richards AT, Jno-Charles OC, Rodriguez I, Callejas S, Norris EH, Sanchez-Gonzalez J, Ruiz-Cabello J, Ibanez B, Strickland S, Fuster V (2019) Long-Term Dabigatran Treatment Delays Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis in the TgCRND8 Mouse Model. J Am Coll Cardiol 74, 1910–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ahn HJ, Glickman JF, Poon KL, Zamolodchikov D, Jno-Charles OC, Norris EH, Strickland S (2014) A novel Abeta-fibrinogen interaction inhibitor rescues altered thrombosis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Exp Med 211, 1049–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zamolodchikov D, Renne T, Strickland S (2016) The Alzheimer’s disease peptide beta-amyloid promotes thrombin generation through activation of coagulation factor XII. J Thromb Haemost 14, 995–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hofman Z, de Maat S, Hack CE, Maas C (2016) Bradykinin: Inflammatory Product of the Coagulation System. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 51, 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Long AT, Kenne E, Jung R, Fuchs TA, Renne T (2016) Contact system revisited: an interface between inflammation, coagulation, and innate immunity. J Thromb Haemost 14, 427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shibayama Y, Joseph K, Nakazawa Y, Ghebreihiwet B, Peerschke EI, Kaplan AP (1999) Zinc-dependent activation of the plasma kinin-forming cascade by aggregated beta amyloid protein. Clin Immunol 90, 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Maas C, Govers-Riemslag JW, Bouma B, Schiks B, Hazenberg BP, Lokhorst HM, Hammarstrom P, ten Cate H, de Groot PG, Bouma BN, Gebbink MF (2008) Misfolded proteins activate factor XII in humans, leading to kallikrein formation without initiating coagulation. J Clin Invest 118, 3208–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bergamaschini L, Parnetti L, Pareyson D, Canziani S, Cugno M, Agostoni A (1998) Activation of the contact system in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 12, 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen ZL, Singh P, Wong J, Horn K, Strickland S, Norris EH (2019) An antibody against HK blocks Alzheimer’s disease peptide beta-amyloid-induced bradykinin release in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 22921–22923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yamamoto-Imoto H, Zamolodchikov D, Chen ZL, Bourne SL, Rizvi S, Singh P, Norris EH, Weis-Garcia F, Strickland S (2018) A novel detection method of cleaved plasma high-molecular-weight kininogen reveals its correlation with Alzheimer’s pathology and cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 10, 480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zamolodchikov D, Chen ZL, Conti BA, Renne T, Strickland S (2015) Activation of the factor XII-driven contact system in Alzheimer’s disease patient and mouse model plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 4068–4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen ZL, Revenko AS, Singh P, MacLeod AR, Norris EH, Strickland S (2017) Depletion of coagulation factor XII ameliorates brain pathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease mice. Blood 129, 2547–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nestor PJ, Scheltens P Fau - Hodges JR, Hodges JR (2004) Advances in the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 10 Suppl, S34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Flicker C, Ferris Sh Fau - Reisberg B, Reisberg B (1991) Mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: predictors of dementia. Neurology 41, 1006–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Storandt M, Grant Ea Fau - Miller JP, Miller Jp Fau - Morris JC, Morris JC (2002) Rates of progression in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 59, 1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Celsis P (2000) Age-related cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment or preclinical Alzheimer’s disease? Ann Med 32, 6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Scheff SW, Price Da Fau - Schmitt FA, Schmitt Fa Fau - DeKosky ST, DeKosky St Fau - Mufson EJ, Mufson EJ (2007) Synaptic alterations in CA1 in mild Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 68, 1501–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chetelat G, Desgranges B, de la Sayette V, Viader F, Berkouk K, Landeau B, Lalevee C, Le Doze F, Dupuy B, Hannequin D, Baron JC, Eustache F (2003) Dissociating atrophy and hypometabolism impact on episodic memory in mild cognitive impairment. Brain 126, 1955–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Johnson KA, Jones K, Holman BL, Becker JA, Spiers PA, Satlin A, Albert MS (1998) Preclinical prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using SPECT. Neurology 50, 1563–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].De Santi S, de Leon MJ, Rusinek H, Convit A, Tarshish CY, Roche A, Tsui WH, Kandil E, Boppana M, Daisley K, Wang GJ, Schlyer D, Fowler J (2001) Hippocampal formation glucose metabolism and volume losses in MCI and AD. Neurobiol Aging 22, 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jagust WJ, Eberling JL, Richardson BC, Reed BR, Baker MG, Nordahl TE, Budinger TF (1993) The cortical topography of temporal lobe hypometabolism in early Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 629, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ray S, Britschgi M, Herbert C, Takeda-Uchimura Y, Boxer A, Blennow K, Friedman LF, Galasko DR, Jutel M, Karydas A, Kaye JA, Leszek J, Miller BL, Minthon L, Quinn JF, Rabinovici GD, Robinson WH, Sabbagh MN, So YT, Sparks DL, Tabaton M, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA, Tibshirani R, Wyss-Coray T (2007) Classification and prediction of clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis based on plasma signaling proteins. Nat Med 13, 1359–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Song F, Poljak A, Smythe GA, Sachdev P (2009) Plasma biomarkers for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Rev 61, 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Foster NL, Jack CR Jr., Galasko DR, Doody R, Kaye J, Sano M, Mohs R, Gauthier S, Kim HT, Jin S, Schultz AN, Schafer K, Mulnard R, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Zamrini EY, Cahn-Weiner D, Thal LJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative S (2004) Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol 61, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Moroney JT, Bagiella E, Desmond DW, Hachinski VC, Molsa PK, Gustafson L, Brun A, Fischer P, Erkinjuntti T, Rosen W, Paik MC, Tatemichi TK (1997) Meta-analysis of the Hachinski Ischemic Score in pathologically verified dementias. Neurology 49, 1096–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Singh PK, Chen ZL, Ghosh D, Strickland S, Norris EH (2020) Increased plasma bradykinin level is associated with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s patients. Neurobiol Dis 139, 104833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Scott CF, Wenzel HR, Tschesche HR, Colman RW (1987) Kinetics of inhibition of human plasma kallikrein by a site-specific modified inhibitor Arg15-aprotinin: evaluation using a microplate system and comparison with other proteases. Blood 69, 1431–1436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Small BJ, Viitanen M, Backman L (1997) Mini-Mental State Examination item scores as predictors of Alzheimer’s disease: incidence data from the Kungsholmen Project, Stockholm. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 52, M299–M304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Muenchhoff J, Poljak A, Song F, Raftery M, Brodaty H, Duncan M, McEvoy M, Attia J, Schofield PW, Sachdev PS (2015) Plasma protein profiling of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease across two independent cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis 43, 1355–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Assini A, Cammarata S, Vitali A, Colucci M, Giliberto L, Borghi R, Inglese ML, Volpe S, Ratto S, Dagna-Bricarelli F, Baldo C, Argusti A, Odetti P, Piccini A, Tabaton M (2004) Plasma levels of amyloid beta-protein 42 are increased in women with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 63, 828–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Elias MF, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Au R, White RF, D’Agostino RB (2000) The preclinical phase of alzheimer disease: A 22-year prospective study of the Framingham Cohort. Arch Neurol 57, 808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nestor PJ, Fryer TD, Ikeda M, Hodges JR (2003) Retrosplenial cortex (BA 29/30) hypometabolism in mild cognitive impairment (prodromal Alzheimer’s disease). Eur J Neurosci 18, 2663–2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang Q, Wang J (2002) Injection of bradykinin or cyclosporine A to hippocampus induces Alzheimer-like phosphorylation of Tau and abnormal behavior in rats. Chin Med J (Engl) 115, 884–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Abbott NJ (2000) Inflammatory mediators and modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Cell Mol Neurobiol 20, 131–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mielke MM, Haughey NJ, Bandaru VV, Schech S, Carrick R, Carlson MC, Mori S, Miller MI, Ceritoglu C, Brown T, Albert M, Lyketsos CG (2010) Plasma ceramides are altered in mild cognitive impairment and predict cognitive decline and hippocampal volume loss. Alzheimers Dement 6, 378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lin CH, Yang HT, Chiu CC, Lane HY (2017) Blood levels of D-amino acid oxidase vs. D-amino acids in reflecting cognitive aging. Sci Rep 7, 14849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. (A) Aprotinin inhibits kallikrein activity in MCI patient plasma. Kallikrein activity of MCI plasma samples was measured in the presence and absence of aprotinin, a known kallikrein inhibitor. Three representative MCI plasma samples (MMSE recall score-0) were diluted (20-fold) in buffer in the presence and absence of aprotinin (3–7 TIU/mg protein). The kallikrein activity was monitored using the S2302 substrate at 37°C in a spectrophotometer. Aprotinin (from bovine lung) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. (B) Plasma C1INH levels in MCI and CN groups. Plasma samples were diluted in assay buffer (1:300,000), and the ELISA was performed in duplicate. C1INH level was not significantly different between CN and MCI groups (N=19 CN, 25 MCI). Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired t test using GraphPad Prism. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.0001.