Abstract

Background and aims:

Amygdalar 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake represents chronic stress-related neural activity and associates with coronary artery disease by coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA). Allostatic load score is a multidimensional measure related to chronic physiological stress which incorporates cardiovascular, metabolic and inflammatory indices. To better understand the relationship between chronic stress-related neural activity, physiological dysregulation and coronary artery disease, we studied the association between amygdalar FDG uptake, allostatic load score and subclinical non-calcified coronary artery burden (NCB) in psoriasis.

Methods:

Consecutive psoriasis patients (n=275 at baseline and n=205 at one-year follow-up) underwent CCTA for assessment of NCB (QAngio, Medis). Amygdalar FDG uptake and allostatic load score were determined using established methods.

Results:

Psoriasis patients were middle-aged, predominantly male and white, with low cardiovascular risk by Framingham risk score and moderate-severe psoriasis severity. Allostatic load score associated with psoriasis severity (β=0.17, p=0.01), GlycA (a systemic marker of inflammation, β=0.49, p<0.001), amygdalar activity (β=0.30, p<0.001), and non-calcified coronary artery burden (β=0.39; p<0.001). Moreover, NCB associated with amygdalar activity in participants with high allostatic load score (β=0.27; p<0.001) but not in those with low allostatic load score (β=0.07; p=0.34). Finally, in patients with an improvement in allostatic load score at one year, there was an 8% reduction in amygdalar FDG uptake (p<0.001) and a 6% reduction in NCB (p=0.02).

Conclusions:

In psoriasis, allostatic load score represents physiological dysregulation and may capture pathways by which chronic stress-related neural activity associates with coronary artery disease, emphasizing the need to further study stress-induced physiological dysregulation in inflammatory disease states.

Keywords: Stress, amygdalar activity, allostatic load score, coronary artery disease, physiological dysregulation

Introduction

Chronic psychological stress is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including atherosclerosis [1], myocardial infarction [2], stroke [3], and high cardiovascularrelated mortality [4], potentially through physiological dysregulation. Prior attempts to quantify stress, including measures of chronic stress-related neural activity assessed as amygdalar 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake [5] or self-reported depression [6], are either difficult to acquire and non-specific [7] or may not fully capture the downstream physiological effects of stress. Allostatic load score is one comprehensive metric for quantifying chronic physiological dysregulation and maladaptive responses to stress [8–10]. This multidimensional risk score was established to quantify health outcomes by age, race and ethnicity among women through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004 [11]. Allostatic load score incorporates measures such as blood pressure, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and homocysteine, which are all CVD risk factors [12] and elevated in chronic inflammatory disease states [13].

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease associated with high psychological stress [14], increased subclinical atherosclerosis [15] and early cardiovascular events [16, 17] compared to patients without psoriasis. Moreover, patients with psoriasis have higher systemic inflammation-driven non-calcified coronary artery disease burden (NCB) by coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) [15, 18–20] when compared with older hyperlipidemic patients as well as healthy controls. In our previous work, chronic stress-related neural activity as assessed by amygdalar FDG positron emission tomography (PET) uptake was elevated in psoriasis and associated with NCB through increased bone marrow activity [21]. However, mechanisms of physiological dysregulation were not evaluated. In this study, we used psoriasis as a human model of inflammation [22] to better understand whether the association between chronic stress-related neural activity as assessed by amygdalar FDG uptake and subclinical coronary artery disease was related to physiological dysregulation as assessed by allostatic load score. Finally, we examined how amygdalar FDG uptake and subclinical coronary artery disease were modulated by changes in allostatic load score over time.

Materials and methods

Demographic and clinical characteristics of psoriasis and control cohorts

Our study included a cohort of consecutively recruited psoriasis patients (n=275) from January 2013 to November 2019 by the Psoriasis, Atherosclerosis and Cardiometabolic Initiative (PACI) at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (NIH CC) (Supplementary Figure 1). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed for reporting our findings [23]. Study protocols were approved by the institutional review board at the National Institutes of Health. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants included in the study were >18 years of age at the time of recruitment and provided written informed consent after a full explanation of the procedures.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants 18 years of age or older with psoriasis consisting of typical skin findings and associated joint, nail and/or hair findings clinically diagnosed by a physician were included in this study. Participants were excluded if they had severe renal excretory dysfunction, estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min/1.73m2, existing cardiovascular disease, any comorbid condition known to be associated with cardiovascular disease or systemic inflammation, such as uncontrolled hypertension, internal malignancy within 5 years, human immunodeficiency virus, active infection within 72 hours of baseline, major surgery within 3 months, and/or pregnancy or lactation. Physician consent was required for donors to enroll in this program, including that they must be healthy per the physician’s standards.

Covariates

Patients were asked to complete survey-based questionnaires regarding smoking, previous cardiovascular disease (CVD), family history of CVD, and previously established diagnoses of hypertension and diabetes. Patient responses were then confirmed during history and physical examination by the study provider. CVD included acute coronary syndrome (ACS) comprising both myocardial infarction (MI) and unstable angina pectoris, angina pectoris, cerebrovascular event, transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease and revascularization procedures including both coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous interventional procedures. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, glycated hemoglobin >6.5%, or use of diabetic medication. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, or use of anti-hypertensive medication. Hyperlipidemia was defined as total cholesterol >5.18 mmol/L, LDL ≥4.14 mmol/L, or HDL ≤1.04mmol/L. Hypertriglyceridemia was not included in the assessment of hyperlipidemia. 10-year Framingham risk score was assessed for all patients.

Clinical data and laboratory measurements

At the time of recruitment, our health-care provider collected data on patient demographics, clinical history, physical examination and anthropometric measurements. Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast and analyzed for basic chemistry, complete lipid profile, insulin, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Baseline psoriasis treatment was patient-reported and defined by use of any of the following in the three months prior to their baseline visit: systemic therapy (steroids or methotrexate), biologic therapy (adalimumab, etanercept, ustekinumab, secukinumab and ixekizumab), statins, light therapy (psoralen plus ultraviolet or ultraviolet B), or topical treatments. Clinical parameters including blood pressure, height, weight, and waist and hip circumferences were measured. Laboratory parameters including fasting blood glucose, fasting lipid panel, complete blood count, and systemic inflammatory markers such as hs-CRP were evaluated in a clinical laboratory.

Amygdalar 18F-FDG uptake

The amygdalae constitute part of the limbic system and are located bilaterally in the dorsomedial temporal lobe. Furthermore, the amgydalae form the ventral, superior, and medial walls of the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle. We acquired and analyzed amygdalar activity by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT as previously published [21, 24, 25]. First, PET and CT data sets were fused. Then the amygdalae were localized on CT images. The lateral ventricles were used to define the anterior aspect of the amygdalae, and the anterior boundary was drawn when the inferior-most section of the lateral ventricles became flattened by the thalamus. The posterior boundary was defined by the crux of fornix and was always anterior to the basilar artery. The internal capsule was used as a guide for the lateral and inferior boundaries of the amygdalae. Amygdalar uptake of 18F-FDG was determined by dividing maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) in each amygdala by mean SUVs in the ipsilateral temporal lobes to normalize uptake to background 18F-FDG uptake. The higher amygdalar uptake between the two amygdalae was taken as the final measurement of amygdalar uptake (OsiriX MD, Geneva, Switzerland).

Coronary computed tomography angiography

All patients underwent blood draw (plasma collection) and coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) on the same day in the same CT scanner (320-dectector row Aquilion ONE ViSION). Guidelines established by the NIH Radiation Exposure Committee were followed. Scans were performed with retrospective gating at 120 kV, tube current of 750 to 850 mA, with a gantry rotation time of ≤420 ms. Image-acquisition characteristics included slice thickness of 0.75 mm and pitch 0.2 to 0.4. Coronary artery phenotyping was performed using QAngio CT (Medis, The Netherlands) with high (ICC>0.95) intraobserver and interobserver agreement and with readers blinded to patient characteristics as previously published [15]. Manual adjustment of inner lumen and outer vessel wall delineations were performed if needed. Measurements of non-calcified coronary artery burden (mm2) were determined by dividing non-calcified volume (mm3) by vessel length (mm) and were attenuated for luminal intensity measures for accuracy. Consecutive psoriasis patients were then assessed for change in subclinical atherosclerosis by CCTA at one-year follow-up.

Allostatic load score calculation

The indices of allostatic load score were: systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, evidence of hypertensive medication, HDL, evidence of lipid-lowering medication, pulse, total cholesterol, homocysteine, body mass index, glucose, evidence of diabetes medication, albumin and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Using a count-based summation method [11], we assigned one point for each index to participants with values >75th percentile for the index. HDL and albumin levels were the exception, with one point assigned for a value <25th percentile for these indices. Participants taking anti-hypertensive medications were assigned two points to account for normalization of systolic and diastolic blood pressure relative to untreated blood pressure. Consecutive psoriasis patients were then assessed for change in allostatic load score at one-year follow-up.

Statistical analyses

All data were assessed for normality via skewness and kurtosis. Data were reported as mean with standard deviation for parametric variables, median with interquartile range for non-parametric variables and percentages for categorical variables. In baseline analyses, parametric and non-parametric variables were compared between the two groups using Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively. In longitudinal analyses, parametric variables were analyzed using paired-t test and non-parametric variables using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Dichotomous variables were analyzed using McNemar’s test for within-group longitudinal analyses. In multivariable linear regression analyses, potential confounding variables were determined by purposeful selection and added to the base model. Standardized beta values from these analyses were reported, which indicate number of standard deviations change in the outcome variable per standard deviation change in the predicting variable. p-value <0.05 was deemed significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) by National Institutes of Health staff, blinded to clinical demographics and imaging characteristics.

Results

Study population

Psoriasis subjects (n=275) were middle-aged (mean±SD: 49.8±13.0), predominately male (n=163, 59%), with low cardiovascular risk as assessed by 10-year Framingham risk score (median: 1.9, IQR: 0.5–5.4), overweight-obese (median body mass index: 28.6, IQR: 25.1–32.9) and with moderate psoriasis, as assessed by psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score (median: 6.00, IQR: 3.00–10.30).

On stratifying by psoriasis severity, patients with severe psoriasis, defined as a PASI score greater than 10, had greater prevalence of traditional CVD risk factors, higher systemic inflammation as assessed by GlycA, higher amygdalar FDG uptake, greater allostatic load score as well as greater non-calcified coronary artery burden when compared with mild-moderate psoriasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of psoriasis cohort stratified by psoriasis severity.

| Variable |

Mild-moderate psoriasis (n=201) | Severe psoriasis (n=69) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 49.8 ± 13.1 | 50.6 ± 12.6 | 0.64 |

| Males | 115 (57) | 46 (67) | 0.17 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 173 (86) | 41 (59) | |

| Black | 6 (3) | 11 (16) | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Asian | 12 (6) | 8 (12) | |

| Multiple | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Unknown | 7 (4) | 8 (12) | |

| Hypertension | 58 (29) | 22 (32) | 0.60 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 93 (46) | 25 (36) | 0.15 |

| Type-2 diabetes mellitus | 19 (10) | 9 (13) | 0.40 |

| Anti-hypertensive therapy | 44 (22) | 23 (33) | 0.06 |

| Statin therapy | 58 (29) | 20 (29) | 0.98 |

| Diabetes therapy | 16 (8) | 9 (13) | 0.21 |

| Current smoker | 26 (13) | 7 (10) | 0.54 |

| Body mass index | 28.5 (25.1–32.1) | 29.2 (25.6–34.5) | 0.14 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | 0.001 |

| Framingham risk score | 1.7 (0.5–5.4) | 2.3 (0.7–5.3) | 0.41 |

| Clinical and lab values | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 122 (112–129) | 123 (113–134) | 0.32 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 71 (66–77) | 73 (68–80) | 0.10 |

| Pulse, beats per minute | 67 (60–78) | 69 (59–78) | 0.68 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 183 (160–208) | 173 (152–204) | 0.15 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 52 (45–67) | 52 (43–62) | 0.36 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 105 (83–124) | 97 (84–120) | 0.53 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 103 (77–142) | 100 (72–136) | 0.64 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 96 (89–104) | 99 (92–110) | 0.03 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 0.34 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 10 (8–11) | 11 (8–13) | 0.05 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.4 (5.2–5.7) | 5.6 (5.1–6.0) | 0.20 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 1.6 (0.8–4.1) | 2.3 (1.0–5.9) | 0.06 |

| GlycA | 405.7 ± 68.5 | 432.2 ± 93.9 | 0.008 |

| Allostatic load score | 3 (1–4) | 4 (2–6) | 0.01 |

| Psoriasis characterization | |||

| Psoriasis area severity index score | 4.2 (2.5–6.6) | 14.7 (12.5–21.6) | <0.001 |

| Biologic therapy | 69 (34) | 11 (16) | 0.02 |

| Vascular characterization | |||

| Total coronary artery burden, mm2 (x100) | 1.18 ± 0.50 | 1.34 ± 0.67 | 0.001 |

| Non-calcified coronary artery burden, mm2 (x100) | 1.12 ± 0.49 | 1.28 ± 0.65 | <0.001 |

Allostatic load score was determined using a count-based summation method [11]. We assigned one point for each index of allostatic load score: body mass index; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; evidence of anti-hypertensive, lipid-lowering or diabetes medication; pulse; total cholesterol; HDL; homocysteine; albumin; glucose; high sensitivity C-reactive protein. Values reported as mean ± SD or median (IQR) for continuous data and N (%) for categorical data. Continuous data were compared using t-test for parametric and Wilcoxon rank-sum for nonparametric observations. Groups containing categorical data were compared using Pearson’s chisquared test. p-value<0.05 deemed significant. Severe psoriasis defined as a PASI (Psoriasis Area Severity Index) score greater than 10. Five patients did not have information on psoriasis severity and were excluded from this analysis. GlycA: nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) signal originating from mobile glycan residues on plasma glycoproteins.

Allostatic load score, traditional cardiovascular risk factors and systemic markers of inflammation

Allostatic load score directly associated with age (β=0.26, p<0.001) and waist-hip ratio (β=0.25, p<0.001) but not with male gender (β=−0.01, p=0.84) nor smoking status (β=0.05, p=0.36). Allostatic load score positively associated with inflammatory markers, including psoriasis severity by psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score (β=0.17, p=0.01), systemic markers of inflammation such as GlycA (β=0.49, p<0.001) and amygdalar FDG uptake, a chronic stress-related neural activity marker (β=0.30, p<0.001).

Allostatic load score and non-calcified coronary artery burden

On stratifying the patient cohort by the median allostatic load score, we observed a 34% higher total coronary artery burden (mean±SD: 1.39±0.62 vs. 1.03±0.37 for high vs. low allostatic load score, p<0.001) and 35% higher non-calcified coronary artery burden (mean±SD: 1.33±0.61 vs. 0.98±0.36 for high vs. low allostatic load score, p<0.001) among patients with high allostatic load score compared to their counterparts (Table 2). Allostatic load score positively associated with both total coronary artery burden (β=0.39; p<0.001) and non-calcified coronary artery burden (β=0.40; p<0.001) in unadjusted models and when adjusted for age, gender, smoking status, biologic therapy for psoriasis and psoriasis severity (β=0.41; p<0.001; β=0.39; p<0.001 respectively).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics of psoriasis cohort stratified by allostatic load score.

| Variable |

Low allostatic load score (n=124) | High allostatic load score (n=151) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 46.1 ± 13.4 | 52.7 ± 12.0 | <0.001 |

| Males | 72 (58) | 91 (60) | 0.71 |

| Race | 0.28 | ||

| White | 100 (81) | 118 (78) | |

| Black | 4 (3) | 13 (9) | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Asian | 11 (9) | 9 (6) | |

| Multiple | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Unknown | 9 (7) | 7 (5) | |

| Hypertension | 11 (9) | 69 (46) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 29 (23) | 89 (59) | <0.001 |

| Type-2 diabetes mellitus | 2 (2) | 26 (17) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 12 (10) | 21 (14) | 0.28 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.940 (0.879–0.995) | 0.971 (0.915–1.018) | 0.004 |

| Framingham risk score | 0.7 (0.2–3.7) | 3.0 (1.4–7.4) | <0.001 |

| Clinical and lab values | |||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 105 (87–120) | 103 (79–123) | 0.53 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 84 (65–122) | 114 (91–174) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.2 (5.0–5.5) | 5.7 (5.4–6.0) | <0.001 |

| GlycA | 378.7 ± 58.5 | 437.1 ± 78.6 | <0.001 |

| Amygdalar activity | 1.06 ± 0.10 | 1.12 ± 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Allostatic load score measures | |||

| Allostatic load score | 1 (1–2) | 5 (3–6) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 119 (112–126) | 126 (113–136) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70 (65–76) | 74 (67–80) | 0.002 |

| Pulse, beats per minute | 64 (58–71) | 72 (62–82) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 184 (164–206) | 181 (154–211) | 0.44 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 58 (47–72) | 50 (41–60) | <0.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 92 (87–97) | 103 (93–115) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.4 (4.2–4.6) | 4.3 (4.0–4.5) | <0.001 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 10 (8–11) | 10 (8–13) | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 1.3 (0.6–2.2) | 3.0 (1.0–7.2) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | 26.0 (24.0–28.8) | 30.8 (27.2–36.7) | <0.001 |

| Anti-hypertensive therapy | 2 (2) | 65 (43) | <0.001 |

| Statin therapy | 13 (11) | 65 (43) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes therapy | 0 (0) | 25 (17) | <0.001 |

| Psoriasis characterization | |||

| Psoriasis area severity index score | 5.5 (2.7–9.6) | 6.2 (3.2–10.8) | 0.15 |

| Biologic therapy | 38 (31) | 45 (30) | 0.70 |

| Vascular characterization | |||

| Total coronary artery burden, mm2 (x100) | 1.03 ± 0.37 | 1.39 ± 0.62 | <0.001 |

| Non-calcified coronary artery burden, mm2 (x100) | 0.98 ± 0.36 | 1.33 ± 0.61 | <0.001 |

Allostatic load score was determined using a count-based summation method [11], and allostatic load score was stratified by the median. We assigned one point for each index of allostatic load score: body mass index; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; evidence of anti-hypertensive, lipid-lowering or diabetes medication; pulse; total cholesterol; HDL; homocysteine; albumin; glucose; high sensitivity C-reactive protein. For a subset of n=160 patients, we obtained 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) of the amygdala.

Values reported as mean ± SD or median (IQR) for continuous data and N (%) for categorical data. Continuous data were compared using t-test for parametric and Wilcoxon rank-sum for non-parametric observations. Groups containing categorical data were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test.

p-value<0.05 deemed significant.

Relationship between non-calcified coronary artery burden and neural stress in high vs. low allostatic load score

Consistent with our prior published report, amygdalar FDG uptake was associated with non-calcified coronary artery burden (β=0.25; p<0.001). Additionally, we found that this relationship persisted in those with high allostatic load score (β=0.27; p<0.001) but not in those with low allostatic load score (β=0.07; p=0.34) when stratified by median allostatic load score. Moreover, this was consistent in analyses adjusted for smoking status, biologic therapy for psoriasis and psoriasis severity as assessed by psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score.

Amygdalar FDG uptake, allostatic load score and subclinical atherosclerosis at one-year follow-up

Given the association of allostatic load score, amygdalar FDG uptake and sub-clinical coronary artery disease, we hypothesized that patients who had an improvement in their allostatic load score would also have improvement in amygdalar FDG uptake as well as coronary artery burden. At one year, 80 patients (39%) had an improvement in allostatic load score, whereas 125 patients (61%) had no change in or worsening of their allostatic load score (Table 3). In patients with an improvement in allostatic load score, there was a 8% reduction in amygdalar FDG uptake (mean±SD reduced from 1.13±0.12 at baseline to 1.04±0.07 at one-year follow-up, p<0.001), 7% improvement in total coronary artery burden (mean±SD reduced from 1.33±0.56 at baseline to 1.24±0.57 at one-year follow-up, p=0.01) and a 6% reduction in non-calcified coronary artery burden (mean±SD reduced from 1.27±0.56 at baseline to 1.20±0.55 at one-year follow-up, p=0.02) from baseline to one-year follow-up (Table 3). There was no significant change in amygdalar FDG uptake, non-calcified coronary artery burden, or total coronary artery burden among patients with no change in or worsening of allostatic load score (Table 3).

Table 3.

Stratified by improvement and worsening in allostatic load score from baseline to one-year follow-up.

| Parameters | No change in or worsening of allostatic load score (n=125) |

Improvement in allostatic load score (n=80) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | One year | p-value | Baseline | One year | p-value | |

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 50.9 ± 12.5 | 52.0 ± 12.5 | - | 48.7 ± 12.3 | 49.8 ± 12.3 | - |

| Males | 75 (60) | 74 (59) | - | 52 (65) | 52 (65) | - |

| White race | 89 (71) | 89 (71) | 1.00 | 61 (76) | 61 (76) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension | 40 (32) | 35 (28) | 0.10 | 22 (28) | 17 (21) | 0.06 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 54 (43) | 52 (42) | 0.56 | 38 (48) | 42 (53) | 0.29 |

| Type-2 diabetes mellitus | 10 (8) | 13 (10) | 0.08 | 11 (14) | 10 (13) | 1.00 |

| Current smoker | 13 (10) | 11 (9) | 0.32 | 10 (13) | 6 (8) | 0.05 |

| Framingham risk score | 1.7 (0.4–5.3) | 2.3 (1.0–6.0) | 0.002 | 2.5 (0.7–6.1) | 2.3 (1.0–5.6) | 0.44 |

| Clinical and lab values | ||||||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 98 (84–120) | 97 (79–123) | 0.43 | 107 (83–128) | 100 (75–121) | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 93 (73–133) | 101 (77–150) | 0.07 | 109 (80–166) | 113 (81–177) | 0.16 |

| Allostatic load score measures | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 121 (110–128) | 119 (107–129) | 0.17 | 127 (115–138) | 117 (107–125) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 71 (65–77) | 70 (63–78) | 0.18 | 75 (70–82) | 68 (63–72) | <0.001 |

| Pulse, beats per minute | 64 (59–74) | 65 (58–71) | 0.04 | 72 (64–82) | 64 (58–71) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 177 (158–205) | 179 (157–209) | 0.82 | 185 (157–210) | 180 (152–204) | 0.33 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 54 (46–67) | 52 (45–67) | 0.80 | 49 (42–61) | 52 (45–62) | 0.21 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 95 (89–101) | 97 (91–106) | 0.03 | 99 (91–110) | 99 (93–110) | 0.26 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.3 (4.2–4.5) | 4.3 (4.1–4.4) | 0.005 | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 4.3 (4.2–4.5) | 0.02 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 10 (8–11) | 10 (8–12) | 0.001 | 10 (8–13) | 10 (8–12) | 0.58 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 1.8 (0.8–3.2) | 1.7 (0.7–3.7) | 0.95 | 2.1 (0.8–4.7) | 1.1 (0.6–2.4) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | 28.6 (25.1–32.2) | 28.2 (24.9–32.4) | 0.95 | 29.1 (25.8–34.7) | 28.6 (25.6–32.2) | 0.12 |

| Anti-hypertensive therapy | 32 (26) | 40 (32) | 0.01 | 18 (23) | 17 (21) | 0.32 |

| Statin therapy | 33 (26) | 37 (30) | 0.25 | 27 (34) | 29 (36) | 0.41 |

| Diabetes therapy | 9 (7) | 10 (8) | 0.56 | 10 (13) | 9 (11) | 0.56 |

| Psoriasis characterization | ||||||

| Psoriasis area severity index score | 5.55 (3.00–11.75) | 3.20 (1.80–5.70) | <0.001 | 5.70 (3.20–8.90) | 2.80 (1.40–4.80) | <0.001 |

| Biologic therapy | 35 (28) | 68 (54) | <0.001 | 25 (31) | 47 (59) | <0.001 |

| Neural activity | ||||||

| Amygdalar activity | 1.09 ± 0.11 | 1.08 ± 0.12 | 0.58 | 1.13 ± 0.12 | 1.04 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Vascular characterization | ||||||

| Total coronary artery burden, mm2 (x100) | 1.22 ± 0.56 | 1.25 ± 0.58 | 0.17 | 1.33 ± 0.56 | 1.24 ± 0.57 | 0.01 |

| Non-calcified coronary artery burden, mm2 (x100) | 1.15 ± 0.54 | 1.17 ± 0.58 | 0.27 | 1.27 ± 0.56 | 1.20 ± 0.55 | 0.02 |

Values reported as mean ± SD or median (IQR) for continuous data and N (%) for categorical data. Continuous data were compared using t-test for parametric and Wilcoxon rank-sum for non-parametric observations. Groups containing categorical data were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Longitudinal comparisons within groups were made using McNemar’s test.

p-value<0.05 deemed significant.

For a subset of n=160 patients, we obtained 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) of the amygdala.

Discussion

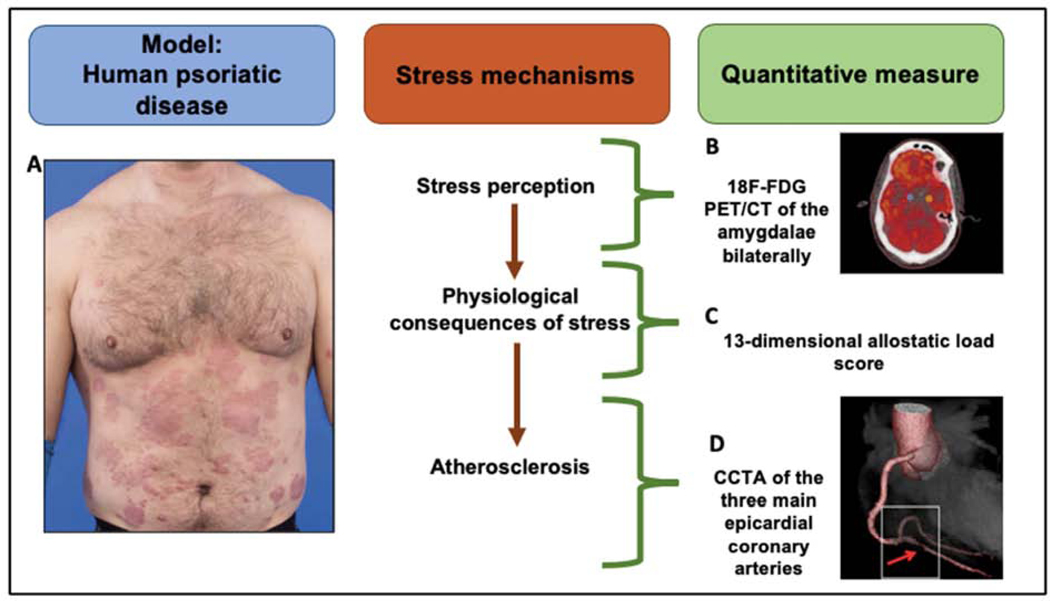

In this longitudinal cohort study of psoriasis patients, we show that (1) allostatic load score positively associates with psoriasis severity as assessed by PASI score and markers of systemic inflammation such as GlycA and amygdalar FDG uptake, (2) allostatic load score associates with non-calcified coronary artery burden independently of psoriasis severity and psoriasis treatment, (3) the relationship between amygdalar FDG uptake and non-calcified coronary artery burden persisted in participants with high allostatic load score but not in participants with low allostatic load score, and (4) in patients whose allostatic load score improved over one year, amygdalar FDG uptake as well as non-calcified coronary artery burden also improved concurrently. Taken together, our findings suggest that neural stress activity in psoriasis patients is associated with coronary artery disease through pathways involving physiological dysregulation as assessed by allostatic load score (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with higher chronic stress perception and cardiometabolic disease.

(A) Patients with psoriasis have characteristic thick, extensive cutaneous plaques. (B) Psoriasis contributes to high stress-related neural activity as assessed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) of the amygdalae bilaterally. The amygdalae are represented by the blue (left) and the orange (right) dots in the coronal brain image. (C) Allostatic load represents physiological stress mechanisms and includes 13 indices of cardiovascular, metabolic, and inflammatory measures. (D) Computed tomography (CT) 3D reconstruction model of a heart showing a rupture prone high-risk coronary plaque (red arrow) in the right posterior descending artery.

Chronic stress both leads to increased CVD events [26] and triggers maladaptive behaviors which modulate CVD risk factors (e.g. adiposity) [27, 28]. Heightened stress can be assessed both through clinical questionnaires and through advanced imaging techniques of the central nervous system. For example, chronic stress-related neural activity as assessed by resting amygdalar activity by FDG PET/CT has been shown to be associated with cardiovascular events [24]. Furthermore, environmental exposures predisposing a person to chronic stress associate with major adverse cardiovascular events in part mediated through amygdalar activity [25, 29]. Moreover, amygdalar activity also associates with non-calcified coronary artery disease which in part is mediated through increased bone marrow activity in inflammatory disease states such as psoriasis [21]. Finally, amygdalar activity has also been shown to predict physiological dysregulation and incident metabolic disease independently of traditional risk factors [30], suggesting a neural mechanism of stress-associated cardiovascular disease.

The subjective perception of chronic psychological stress-related neural activity (e.g. amygdalar FDG uptake) can exceed the body’s adaptive response abilities and can manifest through physiological dysregulation [10]. Allostatic load score, a marker of multisystem physiological dysregulation, captures the effects of stress perception on multiple body systems [9–11]. Allostatic load score has been shown to associate with aging and mortality [8], but has not yet been applied to populations with chronic inflammation such as psoriasis. In this study, we first show that allostatic load score associates with inflammation in the skin as well as systemic markers of inflammation, suggesting that inflammation plays a critical role for development of CVD risk factors in psoriasis. Moreover, we found that physiological dysregulation assessed as allostatic load score associates with chronic stress-related neural activity (amygdalar FDG uptake) as well as subclinical atherosclerosis in psoriasis patients. Interestingly, we found the relationship between amygdalar FDG uptake and subclinical atherosclerosis only in those with high allostatic load score but not in those with low allostatic load score, suggesting the physiological pathways captured in allostatic load score relate to neural stress-associated CVD. Finally, these relationships are preserved longitudinally: amygdalar FDG uptake as well as coronary artery disease modulate with changes in allostatic load score, suggesting allostatic load score may not only capture effects of chronic stress perception at baseline but also over time.

Our study has several limitations. This was an observational study, and as such, is subject to potential for unmeasured confounders and selection bias. Importantly, our observational study only permits associational analyses and does not imply causation. Specifically, it is not clear if heightened amygdalar activity drives stress-associated physiological changes. Therefore our observational study must be followed by detailed experiments, especially in models of chronic inflammatory diseases. Our study is limited in that we do not have markers of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation to quantify neurohormonal contributions to allostatic load score. However, studies of allostatic load score and socioeconomic status found no difference in composite neuroendocrine markers and the primary outcome [31, 32]. More defined measures of stress would have strengthened our findings in addition to the laboratory metrics. Furthermore, assessment of physical metrics of chronic stress such as premature greying of hair or poor sleep efficiency and hygiene would increase specificity of our findings. In the United States, there is a slightly higher prevalence of psoriasis among White/Caucasian patients than among African American patients [33]. Our results should be interpreted in light of the majority White population in our study, and future studies must evaluate the burden of stress-induced cardiovascular disease among other racial and ethnic subgroups. Finally, our assessment of cardiovascular outcomes would be enhanced by the assessment of hard cardiovascular events.

Conclusions

Ours is the first study to characterize physiological dysregulation as assessed by allostatic load score in psoriasis patients. Allostatic load score positively associated with psoriasis severity as assessed by PASI score, systemic inflammation as assessed by GlycA and neural stress as assessed by amygdalar FDG uptake. Moreover, allostatic load score associated with non-calcified coronary artery burden and captured chronic stress-related cardiovascular disease. Finally, in patients whose allostatic load score improved over one year, amygdalar FDG uptake as well as non-calcified coronary artery burden also improved over time, emphasizing the need to further study chronic physiological dysregulation in inflammatory disease states such as psoriasis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Allostatic load score represents physiological stress mechanisms.

Allostatic load associates with psoriasis severity and systemic inflammation increase.

Neural stress activity relates to allostatic load score.

Allostatic load score relates to subclinical atherosclerosis at baseline and over time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants for their generous contribution to research endeavors. We also sincerely thank the clinical care team of the NIH Clinical Center Outpatient Clinic-7 for their care of our participants.

Dr. Mehta is a full-time US government employee and has served as a consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Leo Pharma receiving grants/other payments; as a principal investigator and/or investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and Novartis receiving grants and/or research funding; and as a principal investigator for the National Institute of Health receiving grants and/or research funding. Dr. Gelfand served as a consultant for BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, UCB (DSMB), Pfizer Inc., and Sun Pharma, receiving honoraria; receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis Corp, Celgene, Ortho Dermatologics, and Pfizer Inc.; received payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Lilly, Ortho Dermatologics, and Novartis; is a co-patent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma; and is a Deputy Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, receiving honoraria from the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Intramural Research Program (HL006193–05). This research was made possible through the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Genentech, the American Association for Dental Research, the Colgate-Palmolive Company, and other private donors. Dr. Powell-Wiley is funded by the Division of Intramural Research at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

☐ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Mehta is a full-time US government employee and has served as a consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Leo Pharma receiving grants/other payments; as a principal investigator and/or investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and Novartis receiving grants and/or research funding; and as a principal investigator for the National Institute of Health receiving grants and/or research funding. Dr. Gelfand served as a consultant for BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, UCB (DSMB), Pfizer Inc., and Sun Pharma, receiving honoraria; receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis Corp, Celgene, Ortho Dermatologics, and Pfizer Inc.; received payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Lilly, Ortho Dermatologics, and Novartis; is a co-patent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma; and is a Deputy Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, receiving honoraria from the Society for Investigative Dermatology. All other authors declare no conflicts of interests in relation to the work presented in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Steptoe A, Kivimaki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(6):360–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Arnold SV, Smolderen KG, Buchanan DM, Li Y, Spertus JA. Perceived stress in myocardial infarction: long-term mortality and health status outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(18):1756–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Everson-Rose SA, Roetker NS, Lutsey PL, Kershaw KN, Longstreth WT Jr, Sacco RL, et al. Chronic stress, depressive symptoms, anger, hostility, and risk of stroke and transient ischemic attack in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yao BC, Meng LB, Hao ML, Zhang YM, Gong T, Guo ZG. Chronic stress: a critical risk factor for atherosclerosis. J Int Med Res. 2019;47(4):1429–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Etkin A, Wager TD. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1476–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Aberra TM, Joshi AA, Lerman JB, Rodante JA, Dahiya AK, Teague HL, et al. Self-reported depression in psoriasis is associated with subclinical vascular diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2016;251:219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Drevets WC, Price JL, Bardgett ME, Reich T, Todd RD, Raichle ME. Glucose metabolism in the amygdala in depression: relationship to diagnostic subtype and plasma cortisol levels. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71(3):431–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4770–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(2):108–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chyu L, Upchurch DM. Racial and ethnic patterns of allostatic load among adult women in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(4):575–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ganguly P, Alam SF. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J. 2015;14:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Evers AW, Verhoeven EW, Kraaimaat FW, de Jong EM, de Brouwer SJ, Schalkwijk J, et al. How stress gets under the skin: cortisol and stress reactivity in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(5):986–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, Aberra TM, Dey AK, Rodante JA, et al. Coronary Plaque Characterization in Psoriasis Reveals High-Risk Features That Improve After Treatment in a Prospective Observational Study. Circulation. 2017;136(3):263–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296(14):1735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(8):1000–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Elnabawi YA, Dey AK, Goyal A, Groenendyk JW, Chung JH, Belur AD, et al. Coronary artery plaque characteristics and treatment with biologic therapy in severe psoriasis: results from a prospective observational study. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(4):721–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Teague HL, Varghese NJ, Tsoi LC, Dey AK, Garshick MS, Silverman JI, et al. Neutrophil Subsets, Platelets, and Vascular Disease in Psoriasis. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Naik HB, Natarajan B, Stansky E, Ahlman MA, Teague H, Salahuddin T, et al. Severity of Psoriasis Associates With Aortic Vascular Inflammation Detected by FDG PET/CT and Neutrophil Activation in a Prospective Observational Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(12):2667–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Goyal A, Dey AK, Chaturvedi A, Elnabawi YA, Aberra TM, Chung JH, et al. Chronic Stress-Related Neural Activity Associates With Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in Psoriasis: A Prospective Cohort Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Harrington CL, Dey AK, Yunus R, Joshi AA, Mehta NN. Psoriasis as a human model of disease to study inflammatory atherogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312(5):H867–H73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tawakol A, Ishai A, Takx RA, Figueroa AL, Ali A, Kaiser Y, et al. Relation between resting amygdalar activity and cardiovascular events: a longitudinal and cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):834–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Osborne MT, Radfar A, Hassan MZO, Abohashem S, Oberfeld B, Patrich T, et al. A neurobiological mechanism linking transportation noise to cardiovascular disease in humans. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(6):772–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Sliwa K, Zubaid M, Almahmeed WA, et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):953–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chandola T, Britton A, Brunner E, Hemingway H, Malik M, Kumari M, et al. Work stress and coronary heart disease: what are the mechanisms? Eur Heart J. 2008;29(5):640–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chandola T, Brunner E, Marmot M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: prospective study. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):521–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tawakol A, Osborne MT, Wang Y, Hammed B, Tung B, Patrich T, et al. Stress-Associated Neurobiological Pathway Linking Socioeconomic Disparities to Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(25):3243–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Osborne MT, Ishai A, Hammad B, Tung B, Wang Y, Baruch A, et al. Amygdalar activity predicts future incident diabetes independently of adiposity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;100:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McClain AC, Xiao RS, Gao X, Tucker KL, Falcon LM, Mattei J. Food Insecurity and Odds of High Allostatic Load in Puerto Rican Adults: The Role of Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program During 5 Years of Follow-Up. Psychosom Med. 2018;80(8):733–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].McClain AC, Gallo L, Isasi CR, Kaplan R, Cardel MI, Estrella ML, et al. Association of Subjective Social Status With Allostatic Load in The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Circulation. 2020;141:AP396. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, Thomas J, Kist J, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.