Abstract

X-ray cross complementing protein 1 (XRCC1) is a DNA repair scaffold that supports base excision repair and single strand break repair, and is also a participant in other repair pathways. It also serves as an important co-transporter for several other repair proteins, including aprataxin and PNKP-like factor (APLF), and DNA Ligase 3α (LIG3) This review considers the strategies and structures involved in meeting a set of highly diverse and yet related repair functions.

Graphical abstract

X-ray cross complementing protein 1 (XRCC1) plays a central and yet still incompletely understood role in the repair of DNA containing abasic sites, damaged bases, and single strand breaks [1, 2]. It also forms an important complex with DNA Ligase 3α (LIG3) that supports its nuclear localization and participation in these as well as other repair activities. By combining highly specialized regions that help to organize specific repair functions with recruitment of additional enzymes whose contribution is dependent on the details of the damaged site, XRCC1 is able to handle an expanded range of problems that may arise as the repair progresses or in connection with other repair pathways with which it interfaces. This review discusses the interplay between these functions and considers some possible interactions that underlie its reported repair activities.

XRCC1 involvement in multiple DNA repair pathways

DNA repair scaffolds respond to damage-specific recruitment signals and in turn recruit a set of enzymes optimized to execute the repair. Ideally, the scaffold provides not only the set of enzymes required to implement repair, but may also facilitate transfer of the DNA repair intermediate from enzyme to enzyme reducing the likelihood of releasing cytotoxic intermediates, and promote additional interactions with other cellular components that hasten repair. The XRCC1 scaffold has been found to support two related DNA repair pathways: base excision repair (BER) and single-strand break repair (SSBR), while LIG3 participates in these and other pathways including nucleotide excision repair [3] and alternate non-homologous end joining (alt-NHEJ) [4]. Perhaps as a consequence of its broader involvement in multiple pathways, there remain many enigmatic characteristics of its interactions and behavior.

XRCC1-supported BER is a principle role for this scaffold [1]. The XRCC1 N-terminal domain forms a stable complex with DNA polymerase β (pol β) that is further enhanced under conditions favoring formation of a Cys12-Cys20 disulfide bond [5]. The BRCT1 domain near the center of the scaffold interacts with both poly(ADP-ribose) and dsDNA [6, 7]. However, evidence supporting direct XRCC1 interactions with other upstream BER enzymes including apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease 1 (APE1) and DNA glycosylases has been limited [2, 8]. The XRCC1 C-terminal BRCT2 domain forms a strong complex with LIG3 [9] that is required for LIG3 nuclear localization [10]. A weak interaction between the REV1 interacting region (RIR) in Linker 1 and polynucleotide kinase-phosphatase (PNKP) [11] indicates participation of a cyclic XRCC1 conformation that also brings LIG3 into closer proximity with pol β. However, other recent studies have indicated that, at least for some cell types and conditions, DNA Ligase 1 (LIG1) rather than LIG3 is favored for BER [12], and can be recruited for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-dependent long patch BER [13]. LIG3 is a more adaptable enzyme that includes a DNA-binding ZnF motif that is able to interact with non-canonical structures such as single strand gaps and flaps and double strand breaks (DSBs) [2], supporting a broader functional repertoire. This adaptability probably underlies its additional participation in other repair pathways such as alt-NHEJ [14]. A further issue impacting ligase selection is the inactivation of LIG1 in quiescent cells [15].

At the core of these observations is the involvement of XRCC1 in two major classes of damage repair: BER and SSBR, that have many common characteristics, but also differ in several important respects. Sensing of base damage and abasic sites is an inherently delocalized process relying on DNA glycosylases and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1), while sensing of single strand breaks relies primarily on poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 (PARP1)-dependent auto PARylation [2]. Alternatively, base damage recognition does not generally require the additional involvement of PARP1 and the associated formation of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) [16]. Isolated pol β and LIG3 are also reported to be able to function independent of the XRCC1 scaffold, supporting both damage identification and repair [1, 17, 18]. Alternatively, strand breaks not formed by APE1 or by DNA glycosylases are unprotected and hence will generally elicit a PARP1 response, to which XRCC1 and potentially other proteins with PAR-binding domains respond.

Thus, XRCC1 brings together sets of proteins involved in at least three related types of repair: BER, SSBR, and unusual or challenging ligation problems (Figure 1). While supporting distinct processes in DNA repair, they also overlap to varying extents in a damage-dependent manner. To the extent that BER proceeds as a pairwise transfer of repair intermediates from one enzyme to the next [19], the primary buffer against the failure of the next enzyme in the process to appear in a timely manner is the stability of the product complexes [1, 20] that protects the repair intermediate until further processing becomes available. However, the stability of the damage complex is ultimately limited and premature release of the repair intermediate by APE1 or a DNA glycosylase can lead to an exposed cytotoxic intermediate, followed by PARP1/PAR signaling supporting recruitment of the XRCC1 complex.

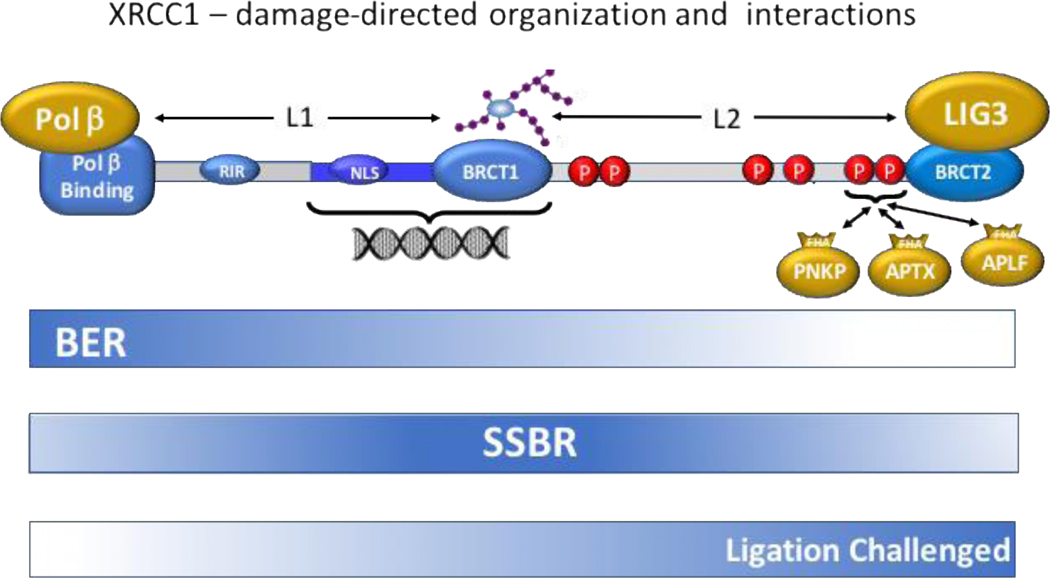

Figure 1. Schematic of XRCC1-supported DNA repair.

XRCC1 brings together enzymes focused on three overlapping but distinct DNA repair processes. The N-terminal, pol β-binding (PBB) domain recruits the primary BER polymerase, which can more generally support short patch repair. The central region responds to the PAR damage signal and supports long and short patch single strand break repair activities. The C-terminal DNA LIG3-binding BRCT2 domain brings together a ligase that is capable of interacting directly with DNA through its ZnF domain with a phosphorylation motif that can interact with the enzymes PNKP and APTX that sanitize the DNA termini at a break in order to create polymerase- or ligation-ready substrates. Linkers 1 and 2 contain important functionality that supports nuclear localization, non-specific dsDNA binding, and phosphorylation-dependent interactions with other repair proteins.

The role of XRCC1 in nuclear localization of repair proteins

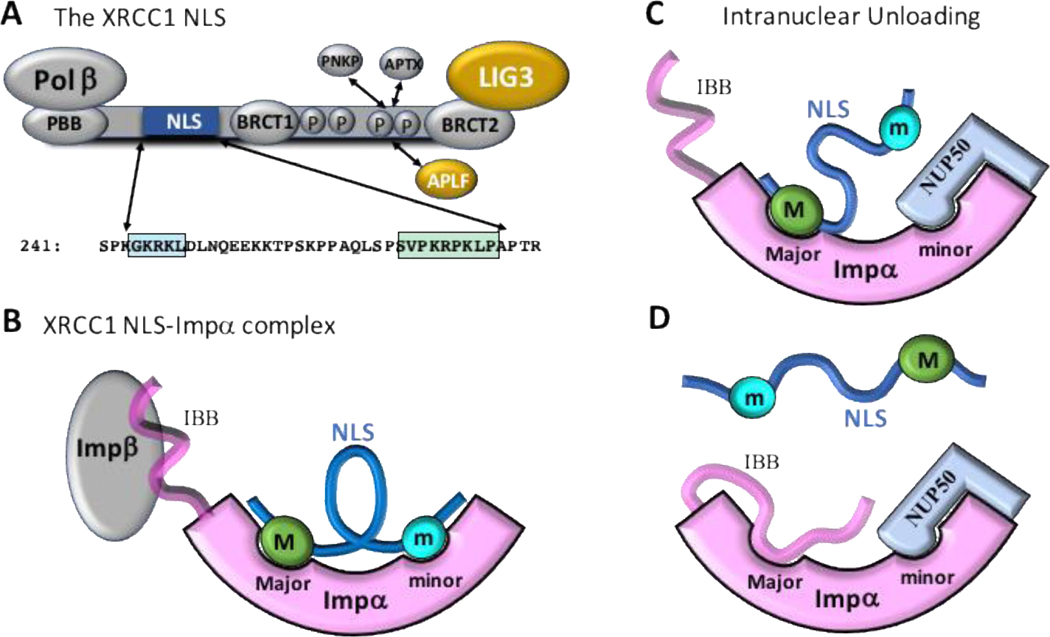

Nuclear localization of XRCC1 is dependent on a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) located in linker 1 [21] (Figure 2A,B). The bipartite structure, in which the major and minor Impα binding motifs are separated by ~20 residues, provides a useful basis for combining high affinity binding with rapid unloading kinetics, satisfying two important constraints required by the nuclear transport machinery (Figure 2C,D). XRCC1 also plays an important role in supporting the cotransport of at least two other repair proteins: LIG3 and the NHEJ scaffold APLF, both of which lack classical NLS signals [10, 22]. Although a requirement for XRCC1 in some of the repair pathways that utilize LIG3 or APLF has been questioned [4], its involvement in the nuclear localization of LIG3 and APLF indicates at least an indirect contribution to repair activities involving these proteins. XRCC1 may also support nuclear localization of pol β, which binds to the N-terminal domain, however the small size (40 kDa) of the enzyme could allow it to leak out through the nuclear pore. Maintenance of a small, 3-fold nuclear/cytosolic gradient is dependent on continuous uptake that utilizes a pol β N-terminal NLS sequence [23].

Figure 2. XRCC1 plays an important role in repair protein nuclear localization.

A) XRCC1 contains a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) in linker 1 that includes both major site binding (M) and minor site binding (m) motifs [21]. In addition to supporting nuclear localization of XRCC1, the NLS supports nuclear localization of at least two other XRCC1-binding repair proteins: LIG3 and APLF. B) The major and minor motifs of XRCC1 bind cooperatively to the cognate sites on Importinα (Impα). Impα also contains an unstructured N-terminal Impβ-binding motif (IBB) that remains bound to Impβ during the loading phase of the nuclear transport cycle. C) The bipartite NLS motif also facilitates intranuclear unloading of the XRCC1 cargo protein from Impα. A small fraction of the NLS exists with only the major site occupied. This allows binding of the nuclear unloading factor NUP50, which interacts with the region of Impα containing the minor site. D) Dissociation of the remaining major site motif allows rapid replacement by the N-terminal IBB domain, which has been freed due to intranuclear separation from Impβ. The unloading process helps to prevent export of incompletely unloaded cargo proteins.

It is unknown whether cotransport involves binary and/or ternary XRCC1-LIG3-APLF species. Transport of these multi-domain complexes with extended unstructured linkers would seem to be challenging, however some studies suggest that large disordered proteins are readily transported. Perhaps the polyphosphorylated Linker 2 can mimic DNA sufficiently to allow formation of a more compact linker 2 complex with LIG3, however this has not been demonstrated.

The BER pathway – considerations and speculations

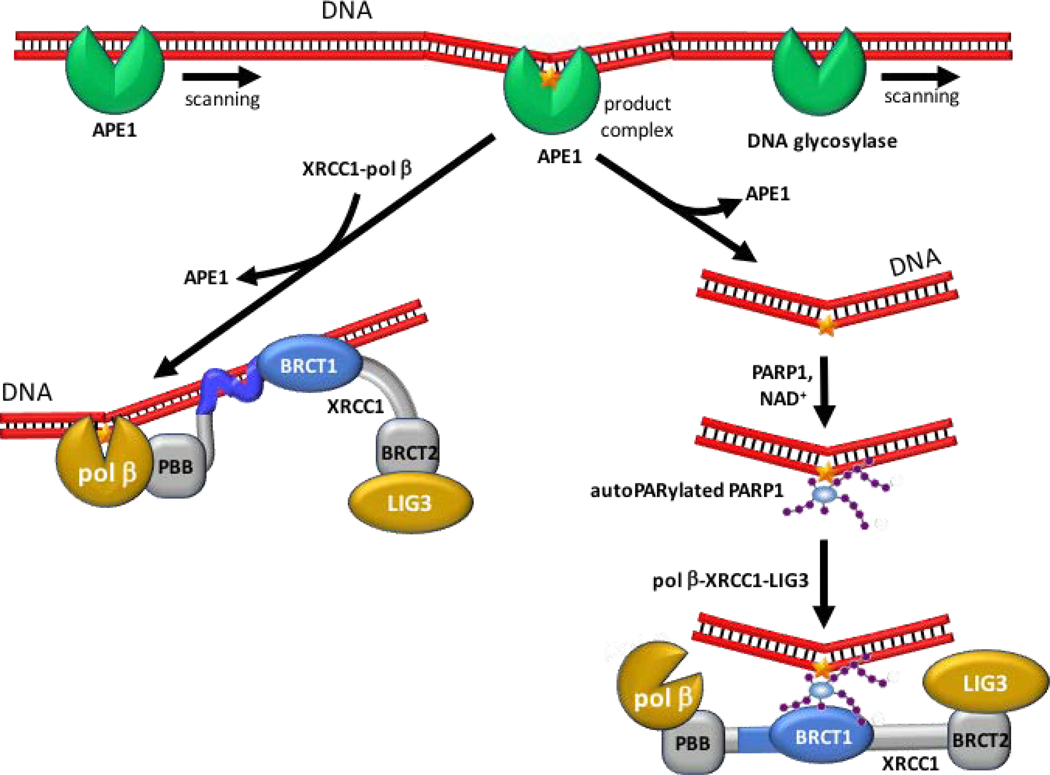

There is an intrinsic tension between the damage sensing, search and repair nature of the BER pathway and the advantages of a multienzyme scaffold-supported complex for optimal efficiency and versatility. The formation rate of abasic and base-damaged sites may exceed the repair capabilities of the cell at any given time, requiring that APE1 and DNA glycosylases fulfill three functions: damage sensing, repair initiation, and stabilization of the resulting repair intermediate - as indicated by slow product release [1, 20]. Small, more agile proteins that are not tethered to a scaffold are generally more suited to the extensive DNA scanning activity required to identify damage. It is therefore not that surprising that evidence for the formation of more tightly bound complexes of XRCC1 or pol β with APE1 and DNA glycosylases that could constrain these scanning activities has proven to be elusive [8]. Further, binding of free APE1 or DNA glycosylases to XRCC1 could occupy pol β/XRCC1 with non-productive complexes that would compete with binding to the product complexes. It therefore would seem extremely beneficial for the XRCC1-pol β scaffold to bind selectively to the APE1- or glycosylase-DNA product complexes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. XRCC1 participates in BER by facilitating transfer of DNA damage.

DNA glycosylases and APE1 (green) scan DNA to detect damaged bases and abasic sites. Subsequent to encountering damage, the repair is initiated, and a metastable complex is formed. Encounter with XRCC1-pol β or free pol β facilitates damage release and transfer of the damaged DNA to pol β or to another more appropriate enzyme in the repair pathway (lower left). Occasional unfacilitated dissociation of the protective APE1 or DNA glycosylase from the damage intermediate complex results in an unprotected strand break, followed by PARP1 activation, and recruitment of XRCC1 via the BRCT1-PAR interaction (lower right). Highly basic regions of XRCC1 involved in DNA binding are indicated in blue. Abbreviations: APE1, apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1; PBB, XRCC1 N-terminal pol β-binding domain.

Several recent observations provide some additional clues relevant to BER. The BRCT1 domain and the C-terminal section of Linker 1 have been shown to support non-specific, dsDNA binding [7] (Figure 1). This capability would appear to be particularly useful to allow the XRCC1 complex to remain associated near the damage site without directly interfering with enzyme-damage site interactions, and without requiring PAR recruitment, which may be absent for most BER [16]. Indeed, non-specific dsDNA binding might be compatible with XRCC1 scanning of undamaged DNA. Interestingly, this interaction appears to depend largely on the same segments of the linker that contain the bipartite NLS motif [7, 21], introducing the more general possibility that a subset of NLS sequences may additionally support non-specific dsDNA binding. Further investigations may clarify the roles of this non-specific DNA binding. The stability of APE1- and DNA glycosylase-DNA product complexes appears to rely strongly on electrostatic interactions, e.g. recent observations of APE1-product complexes reveal the role of arginine clamps as stabilization factors [24]. The reported abilities of XRCC1 and pol β to facilitate dissociation of APE1- and DNA glycosylase product complexes [20] (Figure 3) may utilize competing electrostatic interactions, however the basis for these effects is currently unclear. One recent study indicates that binding and release of DNA damage by Thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) is facilitated by transfer of SUMO from XRCC1 (Figure 4A) to TDG [25].

Figure 4. Additional BER-related motifs.

A) The surface formed by the XRCC1 pol β-binding (PBB) domain (gray) in complex with pol β (green) (PDB: 3K75 [5]) possesses expanded binding capabilities, and has been shown to interact with acylprotein hydrolase (APEH). Post-translational modifications including ubiquitination of Lys168 and SUMOylation of Lys176 may also contribute to the binding interface. B) A truncated XRCC1 histone binding motif positioned immediately following the N-terminal pol β-binding (PBB) domain may support BER repair of histone-associated DNA. C) Modeled interaction of the XRCC1 binding motif (green) with H2A.Z (gray) obtained by mutating the corresponding YL1 residues in a reported YL1-H2A.Z complex (PDB: 5CHL, [29]). D) The structure shown in panel C in which the ribbon representation of H2A.Z is replaced by a surface rendering.

Second, XRCC1 has been reported to interact with the enzyme acylpeptide hydrolase (APEH) in a pol β-dependent manner; mutation of a residue at the XRCC1-pol β interface abrogates the APEH interaction [26]. Therefore, an enhanced recruitment capability is contingent on the formation of an expanded surface that minimally involves the pol β thumb (nucleotide sensing) subdomain complexed with the XRCC1 N-terminal pol β-binding domain [5] (Figure 4A). The specific role of APEH in DNA repair, and the nature of the interaction between APEH with the expanded surface formed by the XRCC1-pol β complex remain to be determined. Nevertheless, this observation indicates that formation of an extended, bimolecular surface is accompanied by expanded interaction capabilities, and implies the possibility of interaction with additional factors to a greater extent than is supported by the separate protein components.

Cellular DNA is wrapped around histone cores to form nucleosomes, and some studies have indicated formation of an XRCC1-nucleosome complex [8, 27]. DNA repair may require prolonged separation of the damaged DNA site from the histone core, and the separated structure can be stabilized by a histone chaperone. The highly phosphorylated XRCC1 linker 2 (L2) might form a histone complex based primarily on electrostatic interactions. Alternatively, the initial section of Linker 1 includes a sequence with modest homology to the nucleosome assembly protein 1 like (Nap1L) motifs that act as histone chaperones in APLF and other proteins [28] (Figure 4B). The XRCC1-APLF sequence homology is low and limited to the central region of APLF acidic domain, but can be modeled into a reported histone complex (PDB: 5CHL, [29]) to provide a plausible complex for further evaluation. In the modeled structure, Phe180 substitutes for a conserved tyrosine in APLF, and although proline and valine are not considered homologous, Val182 is able to form a favorable hydrophobic interaction with histone residue Tyr11 (Figure 4C,4D). The model shown in Figure 4C,D appears to be consistent with acetylation of Lys169 and SUMOylation at Lys176, but not necessarily with ubiquitination of Lys169 (Figure 4A), and further experimental evaluation of the mode of nucleosome association is required. The downstream XRCC1 RIR motif may recruit pol β for some translesion repair activities [30] but appears to support a number of other activities [11].

LIG3 – a ligase of last resort

The C-terminal arm of XRCC1 terminates with a BRCT2 domain that interacts selectively with the LIG3 BRCT domain [9]. A conserved casein kinase 2 (CK2) phosphorylated motif that includes consecutive pSer-pThr residues is positioned immediately prior to BRCT2, and has been demonstrated to support interaction with the forkhead-associated (FHA) domains present in three other proteins [2]. Two of these proteins: PNKP and aprataxin (APTX) can support the activity of the ligase as well as that of other repair enzymes that require unmodified 3’-ribose and 5’-phosphorylated termini. The placement of this binding motif next to the BRCT2 domain [9] suggests that a principle role of the XRCC1 C-terminus is to function as a religation complex that is able to correct earlier unsuccessful ligation attempts that resulted from unsuitable DNA termini or from other structural features that could not readily be handled by LIG1 or LIG4. Such a role is consistent with the enhanced range of LIG3 substrates that includes non-canonical structures such as flaps or gaps [2]. It is thus well suited for repairing breaks resulting from oxidative damage that are more likely to produce atypical termini. However, ligation by LIG3 is characterized by lower fidelity compared with LIG1 [31], and along with enhanced adaptability comes a greater potential for promiscuity, and an increased possibility of ligating mismatched or damaged DNA. The tether to XRCC1 may help to control the involvement of LIG3 in different repair processes. LIG3 also plays a major role in mitochondrial DNA repair [18] and, in the absence of XRCC1, may function as a homodimer [9].

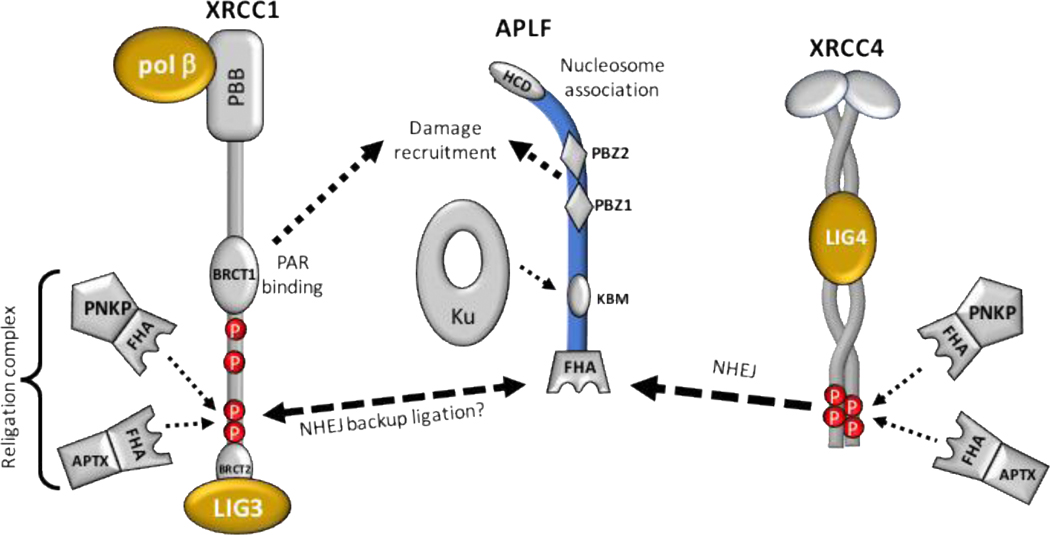

The same XRCC1 phosphorylated motif that supports PNKP and APLF binding also binds to APLF, a largely unstructured protein that has been shown to support non-homologous end joining [32] (Figure 5). The interaction between XRCC1 and APLF has been characterized structurally [33], while its functional role remains unclear. A primary question posed by this interaction is whether XRCC1 is recruiting APLF or vice versa. Viewed from the perspective of SSBR, the additional APLF PBZ domains may respond to a distinct PAR configuration or merely provide greater PAR binding affinity [34] that may be important for targeting XRCC1 to specific although as yet undetermined categories of single strand breaks. Viewed from the perspective of NHEJ, the APLF-XRCC1 interaction may provide an alternate ligation option in the event that LIG4 is unable to complete the repair (Figure 5). In the event that the NHEJ repair fails at an earlier stage, the ability of APLF to remain associated with the damage site due to its PAR-binding zinc finger (PBZ) and histone chaperone domains may support involvement in the alt-NHEJ pathway which relies primarily on LIG3 [14]. At the present time, information about the participants in the alt-NHEJ pathway is limited.

Figure 5. XRCC1-APLF – an interaction between two DNA scaffolds.

The phosphopeptide motif located adjacent to the XRCC1 BRCT2 domain supports interaction with the APLF NHEJ scaffold, but the functional significance of this interaction remains unclear. From the perspective of SSBR, APLF adds additional recruitment capabilities provided by the PAR-binding Zn finger (PBZ) and histone chaperone domains (HCD) that may support additional damage recruitment capabilities beyond those provided by the XRCC1 BRCT1-PAR interaction. Such interactions could support recruitment of XRCC1/LIG3 to specific although as yet undetermined types of SSB. From the perspective of NHEJ, problems encountered at the final ligation step might be resolved by replacement of XRCC4-LIG4 with XRCC1-LIG3, which supports more challenging ligations that might arise. This interaction also may support the lower fidelity alt-NHEJ pathway if APLF is involved in alt-NHEJ, however such involvement has not been demonstrated and information about this pathway is currently limited. Other abbreviations: FHA, forkhead-associated domain; PBB – the XRCC1 N-terminal pol β-binding domain.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my deep gratitude to Sam Wilson for introducing our research group to the field of DNA repair and for the continuing stimulation and insights that he and his staff have provided. I also would like to thank Dr. William Beard and Dr. Geoffrey Mueller for their many thoughtful comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

Funding

The article was written with the support of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health [ZIA-ES050111]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Beard WA, Horton JK, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Eukaryotic Base Excision Repair: New Approaches Shine Light on Mechanism, Annu Rev Biochem, 88 (2019) 137–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Caldecott KW, XRCC1 protein; Form and function, DNA Repair (Amst), 81 (2019) 102664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Paul-Konietzko K, Thomale J, Arakawa H, Iliakis G, DNA Ligases I and III Support Nucleotide Excision Repair in DT40 Cells with Similar Efficiency, Photochem Photobiol, 91 (2015) 1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Soni A, Siemann M, Grabos M, Murmann T, Pantelias GE, Iliakis G, Requirement for Parp1 and DNA ligases 1 or 3 but not of Xrcc1 in chromosomal translocation formation by backup end joining, Nucleic Acids Res, 42 (2014) 6380–6392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cuneo MJ, London RE, Oxidation state of the XRCC1 N-terminal domain regulates DNA polymerase beta binding affinity, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107 (2010) 6805–6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Polo LM, Xu Y, Hornyak P, Garces F, Zeng Z, Hailstone R, Matthews SJ, Caldecott KW, Oliver AW, Pearl LH, Efficient Single-Strand Break Repair Requires Binding to Both Poly(ADP-Ribose) and DNA by the Central BRCT Domain of XRCC1, Cell Rep, 26 (2019) 573–581 e575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mok MCY, Campalans A, Pillon MC, Guarne A, Radicella JP, Junop MS, Identification of an XRCC1 DNA binding activity essential for retention at sites of DNA damage, Sci Rep, 9 (2019) 3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Prasad R, Williams JG, Hou EW, Wilson SH, Pol beta associated complex and base excision repair factors in mouse fibroblasts, Nucleic Acids Res, 40 (2012) 11571–11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cuneo MJ, Gabel SA, Krahn JM, Ricker MA, London RE, The structural basis for partitioning of the XRCC1/DNA ligase III-alpha BRCT-mediated dimer complexes, Nucleic Acids Res, 39 (2011) 7816–7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mortusewicz O, Rothbauer U, Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H, Differential recruitment of DNA Ligase I and III to DNA repair sites, Nucleic Acids Res, 34 (2006) 3523–3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Breslin C, Mani RS, Fanta M, Hoch N, Weinfeld M, Caldecott KW, The Rev1 interacting region (RIR) motif in the scaffold protein XRCC1 mediates a low-affinity interaction with polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase (PNKP) during DNA single-strand break repair, J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 16024–16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Katyal S, McKinnon PJ, Disconnecting XRCC1 and DNA ligase III, Cell Cycle, 10 (2011) 2269–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Woodrick J, Gupta S, Camacho S, Parvathaneni S, Choudhury S, Cheema A, Bai Y, Khatkar P, Erkizan HV, Sami F, Su Y, Scharer OD, Sharma S, Roy R, A new sub-pathway of long-patch base excision repair involving 5’ gap formation, EMBO J, 36 (2017) 1605–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Audebert M, Salles B, Calsou P, Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and XRCC1/DNA ligase III in an alternative route for DNA double-strand breaks rejoining, J Biol Chem, 279 (2004) 55117–55126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ferrari G, Rossi R, Arosio D, Vindigni A, Biamonti G, Montecucco A, Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of human DNA ligase I at the cyclin-dependent kinase sites, J Biol Chem, 278 (2003) 37761–37767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Strom CE, Johansson F, Uhlen M, Szigyarto CA, Erixon K, Helleday T, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is not involved in base excision repair but PARP inhibition traps a single-strand intermediate, Nucleic Acids Res, 39 (2011) 3166–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Howard MJ, Rodriguez Y, Wilson SH, DNA polymerase beta uses its lyase domain in a processive search for DNA damage, Nucleic Acids Res, 45 (2017) 3822–3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Simsek D, Furda A, Gao Y, Artus J, Brunet E, Hadjantonakis AK, Van Houten B, Shuman S, McKinnon PJ, Jasin M, Crucial role for DNA ligase III in mitochondria but not in Xrcc1-dependent repair, Nature, 471 (2011) 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wilson SH, Kunkel TA, Passing the baton in base excision repair, Nat Struct Biol, 7 (2000) 176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Janoshazi AK, Horton JK, Zhao ML, Prasad R, Scappini EL, Tucker CJ, Wilson SH, Shining light on the response to repair intermediates in DNA of living cells, DNA Repair (Amst), 85 (2020) 102749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kirby TW, Gassman NR, Smith CE, Pedersen LC, Gabel SA, Sobhany M, Wilson SH, London RE, Nuclear Localization of the DNA Repair Scaffold XRCC1: Uncovering the Functional Role of a Bipartite NLS, Sci Rep, 5 (2015) 13405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Iles N, Rulten S, El-Khamisy SF, Caldecott KW, APLF (C2orf13) is a novel human protein involved in the cellular response to chromosomal DNA strand breaks, Mol Cell Biol, 27 (2007) 3793–3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kirby TW, Gassman NR, Smith CE, Zhao ML, Horton JK, Wilson SH, London RE, DNA polymerase beta contains a functional nuclear localization signal at its N-terminus, Nucleic Acids Res, 45 (2017) 1958–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Freudenthal BD, Beard WA, Cuneo MJ, Dyrkheeva NS, Wilson SH, Capturing snapshots of APE1 processing DNA damage, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 22 (2015) 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Steinacher R, Barekati Z, Botev P, Kusnierczyk A, Slupphaug G, Schar P, SUMOylation coordinates BERosome assembly in active DNA demethylation during cell differentiation, EMBO J, 38 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zeng Z, Rulten SL, Breslin C, Zlatanou A, Coulthard V, Caldecott KW, Acylpeptide hydrolase is a component of the cellular response to DNA damage, DNA Repair (Amst), 58 (2017) 52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cannan WJ, Rashid I, Tomkinson AE, Wallace SS, Pederson DS, The Human Ligase IIIalpha-XRCC1 Protein Complex Performs DNA Nick Repair after Transient Unwrapping of Nucleosomal DNA, J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 5227–5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Corbeski I, Dolinar K, Wienk H, Boelens R, van Ingen H, DNA repair factor APLF acts as a H2A-H2B histone chaperone through binding its DNA interaction surface, Nucleic Acids Res, 46 (2018) 7138–7152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liang X, Shan S, Pan L, Zhao J, Ranjan A, Wang F, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Feng H, Wei D, Huang L, Liu X, Zhong Q, Lou J, Li G, Wu C, Zhou Z, Structural basis of H2A.Z recognition by SRCAP chromatin-remodeling subunit YL1, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 23 (2016) 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].London RE, The structural basis of XRCC1-mediated DNA repair, DNA Repair (Amst), 30 (2015) 90–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tumbale PP, Jurkiw TJ, Schellenberg MJ, Riccio AA, O’Brien PJ, Williams RS, Two-tiered enforcement of high-fidelity DNA ligation, Nat Commun, 10 (2019) 5431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grundy GJ, Rulten SL, Zeng Z, Arribas-Bosacoma R, Iles N, Manley K, Oliver A, Caldecott KW, APLF promotes the assembly and activity of non-homologous end joining protein complexes, EMBO J, 32 (2013) 112–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim K, Pedersen LC, Kirby TW, DeRose EF, London RE, Characterization of the APLF FHAXRCC1 phosphopeptide interaction and its structural and functional implications, Nucleic Acids Res, 45 (2017) 12374–12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ahel I, Ahel D, Matsusaka T, Clark AJ, Pines J, Boulton SJ, West SC, Poly(ADP-ribose)-binding zinc finger motifs in DNA repair/checkpoint proteins, Nature, 451 (2008) 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]