The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in December 2019 and the subsequent COVID-19 pandemic1 could not have been predicted in August of 2019 when we solicited manuscripts for this issue of the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. If 2020 had been a typical year, this editorial would have set the stage for a special journal issue devoted to quality and patient safety by noting that cardiovascular disease remains the number-one killer globally.2 But this is not a typical year, and while cardiovascular disease will almost certainly retain its unfortunate distinction as the top cause of death in 2020, COVID-19 will not only be among the top 10 causes of death but may also end up contributing to the significant increases in mortality from heart disease during the pandemic.3,4

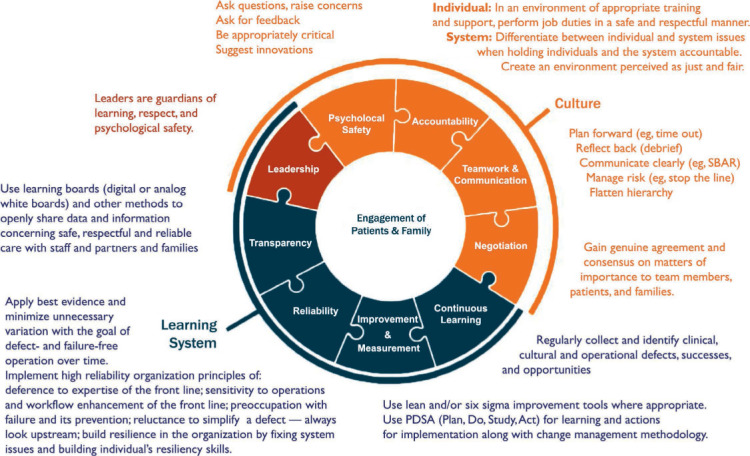

In planning this issue, we did not anticipate that the dominant quality and safety message to the public about life-saving behavior would shift from “Know your numbers” to “Wear a mask, wash your hands, and socially distance.”5,6 Also unanticipated, and gratifying, was the way in which the concepts that we sought to emphasize in this issue on cardiovascular quality and safety would play out in the way that our medical community has successfully responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. At Houston Methodist, our approach to quality and patient safety is grounded in what we term the “Five Rights of High Quality and Safe Care,” which includes the domains of the “right” culture, process, setting, treatment, and value (Table 1). Fundamental to these domains is a commitment to acting as a learning health care system and embracing the principles of a high-reliability organization (Figure 1).7 While Krumholz et al. aptly point out that many health systems were unable to use data in a timely fashion to optimize COVID-19 care, it is remarkable the degree to which many were able to quickly expand ICU capacity, modify surgical and procedural schedules, innovate with personal protective equipment, activate virtual inpatient and ambulatory care to protect staff and keep connections with patients, test new therapies and then rebound to care for the community's non-COVID–related medical needs.8,9

Table 1.

The Houston Methodist Five Rights of High Quality and Safe Care. HM: Houston Methodist; HRO: High Reliability Organization; RCA: Root cause analysis; PDCA: Plan-Do-Check-Act

| RIGHT CULTURE |

|

High Reliability Organization (HRO)

|

| RIGHT PROCESS |

|

|

| RIGHT SETTING | Deliver coordinated care across care continuum | |

| RIGHT TREATMENT | Choose treatments consistent with evidence and with patients’ and their family’s wishes | |

| RIGHT VALUE | Deliver efficient care with no waste to provide the highest quality of care at the appropriate cost |

Figure 1.

Framework for safe, reliable, and effective care. Adapted with permission from Frankel et al. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Safe & Reliable Healthcare. SBAR: Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation

The physicians and staff at Houston Methodist and many other health care systems in our country demonstrated high-reliability principles as they deferred to expertise, incorporated the experience of front-line providers to accelerate innovation, demonstrated resilience, were sensitive to operations and changed workflows based on providers' experiences, and continuously mitigated the risk of failure as they developed innovative approaches to personal protective equipment.

Throughout the pandemic, many health care systems have remained nimble and embraced continuous, iterative, and data-driven clinical knowledge to help manage the COVID-19 crisis. It is in the context of the Five Rights of High Quality and Safe Care—which were ultimately so critical to this agile response—that we solicited the manuscripts for this issue.

We open with an article on culture, the number-one driver of all things related to quality and safety. In “Advancing the Culture of Patient Safety and Quality Improvement,” Dr. Thomas MacGillivray discusses the national imperative to create a culture of safety and develop systems of care to improve health care quality. Yet creating a culture of patient safety and quality requires rigorous assessment of outcomes, and while many data collection and decision support tools are available to assess quality and performance improvement, public reporting of this data can be confusing to patients and physicians alike and result in unintended negative consequences. Using the experience gained from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database as an example, Dr. MacGillivray explores the national efforts to create a culture of quality and safety, the principles of quality improvement, and how these data-driven principles can be applied to improve patient care and medical practice.

From here we shift to a series of articles related to process, with the first focused on the process of ensuring competency. Implementing a culture of safety and quality starts with competent practitioners; however, competence requires knowledge, and according to Drs. John Brush and William Oetgen, most people are not good at assessing their own knowledge and competency level. In their article “Maintenance of Competence in Cardiovascular Training and Practices: Worth the Effort?” the authors explore how myriad professional societies create, regulate, and assure physician competence in cardiovascular training and weigh the value of these efforts against the undue burden it creates for physicians trying to maintain a clinical office practice.

Another aspect of process in the Five Rights relates to its dependence on data-drive care. Capturing and evaluating actionable data is paramount to understanding which treatments are successful and to which populations they apply; it also enables researchers to stratify risk, predict outcomes, benchmark, and improve care. Evidence-based processes are so vital to success that we have two different manuscripts addressing this topic. The first, by Drs. Seth Meltzer and William Weintraub, looks at the expansion and role of cardiovascular registries in the United States. Clinical registries capture data that reflect real-world clinical practice across a large patient landscape and enable measurement of quality metrics across a large cohort of patients. Even so, their limitations in data collection and analysis must be understood to prevent drawing incorrect conclusions and to overcome the inherent treatment selection bias from observational studies. In their article, “The Role of National Registries in Improving Quality of Care and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease,” the authors discuss the growth, benefits, and limitations of national registries, their impact on public reporting, and their role in developing evidence for best clinical practice, measuring outcomes, and improving quality of care.

The second manuscript under the data-driven processes umbrella looks at the learning systems used by Google and Amazon and their ability to glean information from every customer interaction to improve and provide a better user experience. While health systems generate equally voluminous amounts of data that provide ample learning opportunities, these opportunities are largely untapped. In their review titled “The Promise of Big Data and Digital Solutions in Building a Cardiovascular Learning System,” Drs. Harlan Krumholz, Makoto Mori, and colleagues discuss the challenges in realizing the ideal learning health system and the possibility of a data-driven learning health care model that uses real-time data to improve outcomes and generate value.

We then pivot to patient-centered treatment, the fourth domain of the Five Rights and the one tied directly to patient experience. Improving patient experience is one of the key strategies for improving health care quality, delivery, and outcomes. In fact, studies have described the association between improved patient experience and better health outcomes among individuals with cardiovascular disease. The fact that heart disease is the country's leading cause of mortality makes it more pressing for practitioners to develop patient-centered best practices to enhance the patient experience and improve outcomes for this high-risk population. In “Optimizing Patient-Reported Experiences for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease,” Drs. Khurram Nasir and Victor Okunrintemi summarize the findings on patient-reported health care experiences and review measures to optimize patient experience in the context of four domains associated with improved outcomes.

Our last two manuscripts focus on value, the final and perhaps most complex of the Five Rights

First, authors Karen Joynt Maddox and Mustafa Husaini discuss the significant changes in how quality and performance in cardiovascular care have been measured and incentivized over the past two decades. Gaining momentum after passage of the Affordable Care Act, Medicare and other payers have developed value-based payment programs that award or penalize hospitals and clinicians based on the quality and outcomes of care. However, many of the programs have had little benefit in terms of clinical outcomes yet have led to marked administrative burden for participants and discrepancies in public reporting. In their article “Paying for Performance Improvement in Quality and Outcomes of Cardiovascular Care,” the authors describe current efforts and challenges around value-based purchasing programs, point towards new emerging data science methodologies such as machine learning that could risk adjustment models, and offer prospects for the successful implementation of value-based, high-quality cardiovascular care.

We close this issue with a look at value through the lens of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services programs that are designed to emphasize coordination of care (our third right – “Right Setting”) improve quality, and realize cost reduction through programs such as Accountable Care Organizations and Bundled Payments. Value-based payment reform defines “value” as the delivery of high-quality care (measured by patient outcomes) at the lowest achievable cost. But while the concept of incentivizing high-quality coordinated care is simple, the design and implementation of such policies has had mixed effects on quality and spending. In their manuscript “Value Based Payment Reforms in Cardiovascular Care,” Drs. Devraj Sukul and Kim Eagle discuss some of the major nationwide value-based payment reforms related to cardiovascular care and what we may expect in the future.

Devoting an entire issue to the topic of quality and patient safety may seem unusual. After all, the public generally expects quality and safety to be inherent in their health care encounters. However, situations in which that care is compromised are often what spur people to action, especially when they touch us directly or capture our collective attention. Many of us remember the news headlines when the newborn twins of actor Dennis Quaid were twice given 1000-times the intended dose of heparin due to safety lapses and the resulting legislation after he implored congress to hold drug manufacturers responsible for safety violations at the state level. Whether it's a catastrophic medical error or news images of nurses wearing trash bags as PPE, lapses in quality and safety bring systemic flaws into sharp focus, reminding us of our ongoing obligation to ensure the highest quality and safety standards in our profession. For further discussion and CME opportunities, I invite you to visit the journal's website at http://journal.houstonmethodist.org, where you can log in and use the “Dialogue with Authors” link to have an open Q&A with the authors of this issue.

REFERENCES

- 1.JAMA Network [Internet]. Characteristics and Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients During Initial Peak and Resurgence in the Houston Metropolitan Area. In: Vahidy FS, Drews AL, Masud FN, editors. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; c2020. 2020. Aug 13, [cited 2020 Aug 13] Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2769610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019 Mar 5;139(10):e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard J, editor. Covid-19 will end up as a top 10 leading cause of death in 2020, CDC statisticians say. Atlanta, GA: Cable News Network; c2002. 2020 Jul 23 {cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/23/health/covid-rank-leading-cause-of-death-us-bn/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Weinberger DM, Hill L, editors. Excess Deaths From COVID-19 and Other Causes; 2020 Jul [cited 2020 Aug 3] Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; c2020. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2768086. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heart.org [Internet] Know Your Health Numbers. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; c2020. 2015 Aug 31 [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/diabetes/prevention–treatment-of-diabetes/know-your-health-numbers. [Google Scholar]

- 6.medRxiv [Internet]. Doung-ngern P, Suphanchaimat R, Panjagampatthana A et al. Associations between wearing masks, washing hands, and social distancing practices, and risk of COVID-19 infection in public: a cohort-based case-control study in Thailand. c2020 [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.11.20128900v4.

- 7.Frankel A, Haraden C, Federico F, Lenoci-Edwards J. White Paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Safe and Reliable Healthcare; 2017. A Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argenziano M, Fischkoff K, Smith CR. Surgery Scheduling in a Crisis. New Engl J Med. 2020 Jun 4;382:e87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2017424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NEJM Catalyst [Internet]. Waltham MA. Tittle S, Braxton C, Schwartz RL, editors. et al. Massachusetts Medical Society. A Guide for Surgical and Procedural Recovery after the First Surge of Covid-19. c2020 2020 Jul 7 [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/cat.20.0287.