Abstract

Aims:

To outline the study design, outcome measures, protocol and baseline characteristics of enrolled participants of Texas (TX) Sprouts, a one-year school-based gardening, nutrition, and cooking cluster randomized trial.

Methods:

Eight schools were randomly assigned to the TX Sprouts intervention and eight schools to the delayed intervention over three years (2016–2019). The intervention arm received: formation/training of Garden Leadership Committees; a 0.25-acre outdoor teaching garden; 18 student lessons including gardening, nutrition, and cooking activities, taught weekly during school hours by hired educators throughout one school year; and nine parent lessons taught monthly to families. The delayed intervention was implemented the following academic year and received the same protocol as the intervention arm. Primary outcomes included: dietary intake, dietary-related behaviors, obesity, and metabolic parameters. Child measures included: height, weight, waist circumference, body composition, blood pressure, and dietary psychosocial variables. A subsample of children were measured for glucose, hemoglobin-A1C, and 24-hour dietary recalls. Parent measures included: height and weight, dietary intake, and related dietary psychosocial variables.

Results:

Of the 4,239 eligible students, 3,137 students consented and provided baseline clinical measures; 3,132 students completed child surveys, with 92% of their parents completing parent surveys. The subsamples of blood draws and dietary recalls were 34% and 24%, respectively. Intervention arm baseline descriptives, clinical and dietary data for children and parents are reported.

Conclusion:

The TX Sprouts intervention targeted primarily low-income Hispanic children and their parents; utilized an interactive gardening, nutrition, and cooking program; and measured a battery of dietary behaviors, obesity and metabolic outcomes.

Keywords: gardening, nutrition, cooking intervention, Hispanic, low-income, obesity, overweight, school-based

1. Introduction:

In the United States (U.S.), Hispanics are the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority, constituting 18% of the U.S. and almost 40% of the Texas population.1 Hispanics are disproportionately affected by obesity and obesity-related diseases.2–4 In Texas, 66% of adults and 33% of children have overweight or obesity,5 with the highest rates among low-income Hispanics.6 There is a critical need to develop and test interventions to reduce obesity and associated metabolic diseases in low-income Hispanic youth.

Over the past three decades, prices of fresh fruits and vegetables (FV) have increased at a faster rate than foods that are high in added fat and sugar, which are among the least expensive sources of dietary energy.7,8 As a result, financial barriers pose great challenges for low-income Hispanic families to maintain healthy and balanced diets, while high levels of acculturation by Hispanics to the dominant U.S. culture further contribute to decreased FV consumption.9–11 However, by growing FV in school gardens, low-income families can gain access to traditional and nutritionally rich FV that may otherwise not be available to them.12 Recent studies have found that increasing knowledge of where food comes from through a direct experience of growing one’s own FV is an effective way of influencing positive attitudes and preferences for healthy eating.13,14 There is also an increasing need to teach families how to prepare FV in a healthy way. Teaching children and their families how to garden and how to cook healthy meals using traditional Hispanic produce and recipes can provide a sustainable approach to eating healthier and reducing obesity among low-income Hispanic youth.

School gardens have become a common health promotion strategy to enhance dietary behaviors in the U.S. In the past two decades, numerous studies have examined the effects of school gardens on diet-related variables in children;15–18 however, few have reported the effects on childhood obesity and related health measures. We completed a study in 2014 where four schools (~400 3rd-5th grade students) were randomly assigned to either a 12-week after-school gardening, nutrition, and cooking intervention (called LA Sprouts) or to a control group.19 Children who participated in the intervention group experienced significant reductions in BMI z-scores and waist circumference, as well as improvements in dietary intake.19 Among controlled gardening studies to date, only the LA Sprouts program has shown promising effects of a garden and nutrition intervention on reducing obesity and related measures in children.19 However, this program was not designed as a cluster-randomized controlled trial (RCT); it was conducted in an after-school setting, and was only 12 weeks long. Assessing such a program like LA Sprouts using a cluster-RCT where the program is conducted during school hours for an entire school year is warranted.

The overall goal of this project was to test the effects of TX Sprouts: a one-year school-based gardening, nutrition, and cooking cluster randomized trial on dietary intake, dietary-related psychosocial variables, obesity, and related metabolic disorders in low-income Hispanic children. This paper outlines the study design, outcome measures, protocol and baseline characteristics of enrolled participants.

2. Research Design and Methods

2.1. Overview of Study Design

Sixteen elementary schools were randomly assigned to either: (1) TX Sprouts Intervention (n=8 schools) or (2) Control (delayed intervention; n=8 schools). The intervention was implemented in three schools per arm in school years 2016–2017 (n=6 total) and 2017–2018 (n=6 total) and two schools per arm in the 2018–2019 academic year (n=4 total). The intervention consisted of building an edible garden in each intervention school in the form of an outdoor classroom; forming and training Garden Leadership Committees (GLCs), teaching 18 in-school student lessons; and teaching nine parents lessons throughout the academic school year. Therefore, this cluster-randomized trial included both environmental-level intervention components, such as the garden, as well as individual-level intervention components taught through the classroom lessons. The control arm consisted of the same intervention but delivered the academic year following their post-intervention measurements.

2.2. School Sampling, and Eligibility Requirements

All schools had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) high proportion of Hispanic children (>50%); (2) high proportion of children participating in the free and reduced lunch (FRL) program (>50%); (3) location within 60 miles of the University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin) campus; and (4) no existing garden or gardening program. The 2014–2015 Texas Education Agency (TEA) directory of schools in Texas contained 8,653 active public elementary schools in Texas and 582 schools had a distance of less than 60 miles from UT-Austin. Only 79 of these schools had over 50% or more Hispanic students in each of grades 3–5. Seventy-three of the schools had 50% or more students participating in the FRL program in each one of the 3rd-5th grades. All 73 schools were invited to participate: 20 schools from five different independent school districts agreed to participate. Research staff visited all 20 schools to ensure that the school did not have an existing garden or gardening program.

2.3. Random Assignment

The first 16 out of the 20 schools to provide letters of support were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n=8 schools) or control group (delayed intervention; n=8 school). The four remaining schools were placed on a contingency list, in case any of the 16 randomly assigned schools dropped out. Of the 16 randomly assigned schools, two schools declined to participate due to their academic status and were replaced with two of the schools on the contingency list. Table 1 shows summary statistics of the inclusion criteria for the randomly assigned schools. Due to budgetary concerns and the large enrollment in schools, two schools measured only 4th and 5th grade students instead of 3rd-5th grade students. This study was not blinded.

Table 1:

Eligibility requirements of intervention vs. control schools

| Intervention | Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School | # of 3rd-5th grade students | %Hispanic | % FRL | Distance from UT | # of 3rd–5th grade students | %Hispanic | % FRL | Distance from UT |

| 1 | 185 | 88 | 88 | 7.8 | 266 | 82 | 69 | 10.9 |

| 2 | 223 | 80 | 96 | 6.3 | 239 | 70 | 80 | 16.2 |

| 3 | 182 | 77 | 66 | 6.0 | 302 | 82 | 98 | 5.3 |

| 4 | 136 | 68 | 55 | 25.5 | 350 | 72 | 72 | 23.5 |

| 5* | 237 | 50 | 60 | 17.4 | 298 | 73 | 79 | 23.0 |

| 6* | 266 | 60 | 63 | 26.7 | 350 | 76 | 83 | 24.9 |

| 7 | 204 | 92 | 95 | 8.7 | 354 | 61 | 75 | 21.5 |

| 8 | 278 | 71 | 67 | 10.7 | 369 | 73 | 78 | 26.0 |

| Total | 1711 | 2528 | ||||||

| Average | 214 | 73 | 74 | 13.6 | 316 | 74 | 79 | 18.9 |

FRL=free and reduced lunch; UT=University of Texas at Austin. Asterisks (*) denotes the schools where only 4th and 5th grade students were enrolled due to the large enrollment and budgetary concerns.

2.4. Garden Leadership Committees (GLCs)

Garden Leadership Committees (GLC) were formed at each intervention school at least six months before the academic year when the intervention was scheduled to begin. GLCs were comprised of interested stakeholders in the gardening program (such as teachers, parents, community members, school staff, and students). GLCs met with the research staff at least 5–6 times during the planning year to discuss planning for the physical garden design, garden build and workdays, and upcoming TX Sprouts events/lessons. The GLCs were responsible for developing and implementing a plan for long-term garden maintenance and harvests from the garden. One or two Master Gardener volunteers from Texas A&M AgriLife Extension attended GLC meetings and were involved with the garden program at each school. A local non-profit organization in Austin, the Sustainable Food Center (SFC), provided a series of workshops (varying in length from 2–4 hours) to GLC members including a School Garden Leadership Training, a School Garden Classroom Training, and a Food Gardening Class. GLCs were also formed and trained at the control schools after completing pre and post data collection; about four months before the academic year when the intervention was scheduled to begin.

2.5. Garden Construction

Gardens were built in every intervention school in the spring prior to the academic year of baseline measurements. Research staff worked with the principals and GLC members to design each school garden and to come up with a feasible location on the school campus. Stakeholders from the school (i.e., parents, children, teachers, and administration), local communities (i.e., churches, restaurants, small businesses, boy/girl scout troops), and UT staff and students all participated in building the gardens at each school site, which always occurred on Saturday mornings for 5–6 hours. An average of 150 volunteers attended each garden build. While each school garden varied slightly, the outdoor education area included the following at all sites: raised vegetable beds as these are easy to build, make garden access easy for children of all developmental levels, ensure that soils are free of heavy metals/contaminants, and reduce weeds in the garden area; in-ground native and herb beds; a large shed for tools and materials; a whiteboard; and seating for classes. Each site was edged with stones and filled with decomposed granite. The schools were provided with the materials and supplies needed for garden upkeep (e.g. rakes, hoses, etc.) and for teaching the lessons, (e.g., tables, chairs/benches, cooking grill, portable hand-washing sink, pots/pans, etc.). Figure 1 shows an example of the layout of a TX Sprouts outdoor classroom, which includes two large vegetable beds, a native plant bed, herb bed, outdoor seating, whiteboard, and storage shed. Identical gardens were built in the spring in the control schools after post-intervention testing was finished in the intervention schools.

Figure 1.

Layout of a TX Sprouts outdoor classroom.

2.6. Student Curriculum and Lesson Description

During the first year of the project, the TX Sprouts curriculum was adapted from LA Sprouts20 and Junior Master Gardener (JMG), a program developed by the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.21 The social ecological-transactional model was used to develop the curriculum, which suggests that changes in one component of an ecosystem will produce changes in other components, such as (a) changes in the school may change processing in the family and community environment and vice versa, and (b) changes in one domain of student functioning may influence other domains of functioning. These effects are conceptualized on the level of the individual student, family, and school micro-systems, and the interconnections among micro-systems (meso-system).22,23 The curriculum was pilot tested in 2015 with 340 students in a non-TX Sprouts school who accepted to participate in the trial to assess comprehension, cultural appropriateness, difficulty for grade level, and feasibility of cooking recipes. The following are some of the broad nutrition concepts that were included in the final curriculum: (a) healthy cooking/preparation of FV (i.e., low in sugar and fat); (b) making nutritious food choices in different environments; (c) eating locally produced food; (d) low-sugar beverages made with fresh FV; (e) health benefits of FV; f) how to eat healthfully in food desert neighborhoods (neighborhoods lacking easy access to shops selling FV); and (g) food equity and community service. The curriculum also covered a broad range of horticultural and environmental education topics including: (a) science process skills, (b) observation, (c) taking measurements, and (d) problem solving through both group and individual learning experiences. Every lesson included either a garden taste-test (seven lessons) or a cooking activity (11 lessons). Every lesson also included sampling of different “aguas frescas,” which are flavored/infused water with no added sugar. Table 2 displays a list of lesson topics, recipes or taste test activities, and “agua fresca” tastings. The student curriculum was systematically designed to be culturally tailored to Hispanics, including culturally appropriate recipes, content, and activities. Every lesson was also mapped on Texas Essential Knowledge Standards (TEKS) for science, math, language arts, health, and social studies.

Table 2:

Breakdown of TX Sprouts Student and Parent Curriculum

| Student Lesson # | Parent Lesson # | Lesson Topic | Lesson Recipe and Agua Fresca |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Introduction, Kitchen Safety, and Garden Rules | Corn and Black Bean Salad; Cucumber Lemon Agua Fresca |

| 2 | Real versus Processed Food and Food Systems | Tomato/basil/cheese sticks; Watermelon Basil Agua Fresca | |

| 3 | Soil and Planting | Lime Toasted Pepitas; Mint/Lime/Club Soda Agua Fresca | |

| 4 | 2 | Sugar and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages | Multiple Agua Frescas |

| 5 | 3 | Dietary Fiber | Garden Taste Test; Lemon-Lime Agua Fresca |

| 6 | Review of Weeks 1–5 | Whole Grain Pasta with Veggies; Cinnamon Spice Herbal Tea | |

| 7 | 4 | Food Groups and Portions | Vegetable Quesadillas with Salsa; Mint/Lime/Club Soda Agua Fresca |

| 8 | 5 | All About Vegetables | Cucumber/Radish hummus bites; Mint Cucumber Water |

| 9 | Lifecycle of Plants | Garden Taste Test; Cinnamon Spice Herbal Tea | |

| 10 | 6 | Fruits | Fruit Rainbows; Mint Cucumber Water |

| 11 | Eating Healthy at School | Garden Taste Test; Watermelon Basil Agua Fresca | |

| 12 | Review of Weeks 7–11 | Ultimate Sandwich; Agua de Jamaica | |

| 13 | Water | Juicy Jicama Salad; Strawberry-Mint Agua Fresca | |

| 14 | Composting | Garden Taste Test; Watermelon Basil Agua Fresca | |

| 15 | 7 | Eating Healthy on the Go | Cucumber, Radish, and Hummus Bites; Cucumber-Lemon Agua Fresca |

| 16 | 8 | Family Eating | Winter Salad; Mint-Cucumber Agua Fresca |

| 17 | Seasons | Garden Taste Test; Strawberry-Mint Agua Fresca | |

| 18 | 9 | Final Review | Veggie Stir-fry; Watermelon Basil Agua Fresca |

Full-time experienced nutrition and garden educators taught 18 one-hour TX Sprouts lessons separately to each 3rd-5th grade class throughout the school year as part of their normal school day. The school teachers were required by school administrators to attend all of the classes taught by the TX Sprouts educators, providing the initial training for them to continue the program in subsequent years. UT Austin nutrition undergraduate students assisted with teaching the TX Sprouts lessons, many of whom obtained the required research credit hours to graduate. Master Gardeners from Texas AgriLife Extension also assisted with the lessons and received volunteer hour course credits.

2.7. Parent Lessons

The parents’ curriculum was adapted from the LA Sprouts program20 and paralleled the nutrition and gardening topics/activities taught to the children (see Table 2). The parent curriculum was available and taught in both English and Spanish. The curriculum had a strong emphasis on cooking components and focused on growing and cooking foods that are culturally relevant. The garden/nutrition educators taught monthly 60-minute TX Sprouts lessons, for a total of nine lessons, throughout the school year. At the beginning of the year, educators met with parents and school administrators to ask about preferred dates and times to host these parent classes. The dates and times varied widely across school sites, and parent classes were offered in mornings, during school hours, after-school hours, evenings, and even on weekends to account for parent preferences and schedules at the various school sites. Parents were incentivized to attend the lessons with free meals, produce giveaways, groceries, water bottles, t-shirts, garden gloves, and free childcare for children and siblings. Children in the TX Sprouts program were encouraged to attend these lessons with their parents and were often given the opportunity to teach their parents how to cook healthy meals with FV. This model empowered the child to be the champion for healthy changes in the family. The lessons were advertised and promoted by posting flyers, sending home newsletters, and sending out reminder text messages. Nutrition undergraduate students and Texas AgrilLife Extension Master Gardeners also assisted with these lessons.

2.8. Recruitment of Students and Parents

All 3rd-5th grade students and parents at the recruited schools were contacted to participate via information tables at “Back to School” and “Meet the Teacher” evening events, flyers sent home with students, and teachers making class announcements in the fall after the garden had been built at the school. All recruitment materials were available in both English and Spanish. While all 3rd-5th grade students from participating schools received the lessons as part of their in-school curriculum, students/parents did have to provide informed written consent to participate in the measurements or the parent intervention. Students and their parents signed assent and consent forms, respectively, approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at UT Austin, as well as the research departments at each of the participating school districts.

2.9. Measurements

Data were collected on children and parents at baseline (within the first month of the beginning of the academic school year) and post-intervention (within the last month of the academic school year). Approximately 10 trained research staff went to each school for a full week to collect all measures at each school. The list of measures collected is shown in Table 3.

Table 3:

Evaluation Measures Obtained on Child and Parent

| Measure | Child | Parent |

|---|---|---|

| In Person Measures: | ||

| Height, weight, BMI | X | X |

| Waist circumference | X | |

| Body fat via bioelectrical impendence | X | X |

| Blood pressure | X | |

| Fasting blood draw (subsample) | X | |

| Questionnaires: | ||

| Demographics | X | X |

| Reported height and weight | X | |

| Health history form on child | X | |

| Dietary intake via screener | X | X |

| Motivation to eat FV, cook, garden | X | X |

| Preferences for FV | X | X |

| Food security | X | X |

| Cooking and gardening attitudes | X | X |

| Self-efficacy to cook FV and garden | X | X |

| Gardening and nutrition knowledge | X | X |

| Family gardening activities | X | X |

| Family meals | X | X |

| Physical activity questions | X | X |

| Telephone: | ||

| Two 24-hr dietary recalls (subsample) | X |

Anthropometrics, Body Fat, and Blood Pressure:

Height was measured using a free-standing stadiometer mounted against the wall, to the nearest 0.1cm (Seca, Birmingham, UK). Waist circumference was measured using NHANES protocol.24 Weight and bioelectrical impedance were assessed with the Tanita Body Fat Analyzer (model TBF 300). BMI (kg/m2) and BMI percentiles were determined using CDC age- and gender-specific values.25 Blood pressure was measured with an automated monitor with child or adult cuffs (Omron, Schaumberg, IL).

Parental height and weight, body fat, and waist circumference were measured on a subsample of parents during the child’s blood draw (pre-intervention only) or at parent classes. Self-reported height and weight were collected from all parents in the questionnaires at pre- and post-intervention. Objective anthropometrics on the parents were used to validate the self-reported height and weight.

Student Questionnaire:

Development of the child questionnaire was initiated with a review of the literature for measures relevant to nutrition, gardening, and cooking behaviors. Many of the items on the child questionnaire were taken from the child questionnaire used in the LA Sprouts evaluation.20 The final questionnaire included questions on demographics,26 food and meal choice behaviors,27 self-efficacy to cook/prepare fruits and vegetables (FV) and gardening,20,28, preferences for FV and beverage intake,29,30 cooking and gardening attitudes,20, family activities,30, nutrition and gardening knowledge,20, self-reported physical activities,30 and food security.31 Questionnaires were available in both English and Spanish and bilingual interpreters were available to assist students with completing the questionnaire if needed.

Parent Questionnaire:

The parent questionnaire consisted of similar constructs to those in the child questionnaire, but included different wording, number of items, and response options. Additionally, English and Spanish versions of the questionnaire were available, and bilingual interpreters were available to assist parents with completing the questionnaire if needed. The final questionnaire included demographics,26, food and meal choice behaviors,32 child medical history,30 self-reported height and weight, healthy eating habits,33 self-efficacy to cook/prepare FV and garden,20,28 preferences for FV,29 cooking and gardening attitudes,20 cooking and gardening family activity habits,30 nutrition and gardening knowledge,20 and food security.34 Parents who completed and returned the survey received a $15 grocery gift card.

Dietary Recalls:

Dietary intake via two 24-hour dietary recalls was collected in a random subset of children at baseline and follow-up. Sixteen students (eight male and eight female) for a total of 48 students were randomly selected from each grade level at each school to be contacted for recalls. If any of the 16 students were not available or did not want to participant in recalls, then additional students were randomly selected to fill in as back-ups, to ensure that diet recalls were collected on a total of 48 students from each school. The recalls were collected by trained staff and volunteers using Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R, 2016 version), a computer-based software application developed at the University of Minnesota Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC) that facilitates the collection of recalls in a standardized fashion.35 Dietary intake data gathered by phone interview is governed by a multiple-pass interview approach.36 Prior to the recalls being conducted, a Food Amounts Booklet, developed by the NCC, was sent home with all eligible students. The booklets were provided in English and Spanish, and contained pictures of measuring cups, spoons, bowls, and cups, which could be used by students to assist with describing serving sizes of foods and beverages consumed. Parents or guardians were asked to assist with recalling foods eaten or providing serving sizes if children experienced difficulties during the recalls. NDS-R generates nutrient and food/beverage servings, and Healthy Eating Index-2015 was calculated.37 Students received a $10 gift card or $10 check incentive each for completing two recalls at baseline and two recalls at follow-up, totaling $20 in gift card incentives.

Blood Draws:

Optional fasting blood draws at baseline and follow-up were collected for measurement of glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), insulin, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and lipids. Investigators were given permission by the school districts to include blood draws in the project, provided that participation was not required of students. Students who did not participate in the blood draw were still allowed to participate in the other TX Sprouts evaluation measures and in the program.

Eligible students and their families received flyers and text message reminders about the blood draws in the mornings and reminders to fast. Only students who completed the blood draw at baseline were eligible for the follow-up blood draw. Children who elected to participate were asked to not drink or eat anything except water after midnight the prior night. Parental consent and child assent were obtained prior to the blood draw. Blood samples were collected by certified phlebotomists or nurses with experience drawing blood in children with obesity in a private room at the schools. As an incentive for participation, children received $20 for each blood draw at baseline and follow-up.

Samples were collected on site at the schools and transported on ice to the University of Texas at Austin laboratory. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certified glucose using HemoCue Glucose 201 (HemoClue America, Brea, CA) and HbA1c assays using DCA Vantage Analyzer (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) were run on whole blood. Prediabetes was defined as a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 100–125 mg/dl or HbA1c of 5.7–6.4%.40 Parents of children who had a prediabetic result were notified within one to two weeks via a packet addressed to the parents and sent home with the child in a sealed envelope. The envelope contained a blood screening results form that provided height, weight, BMI percentile, blood pressure, FPG, and HbA1c, along with the interpretation of the values. It also included a letter stating that their child may be prediabetic, that failure to fast could have elevated the results, and that follow-up with a physician is recommended. A list of low-cost clinics was included for those who wanted to follow-up with a doctor.

The remaining blood was centrifuged, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. At the end of wave three, further assays will be run on all samples. Insulin will be run using an automated enzyme immunoassay system analyzer (Tosoh Bioscience, Inc. San Francisco, CA). Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) will be calculated as a measure of insulin resistance according to the method described by Matthews et al.38 Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and triglyceride levels will be measured using the Vitros chemistry DT slides (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics Inc., Rochester, NY). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) will be calculated using the Friedewald equation.39

Fidelity and Process Evaluation:

During the TX Sprouts intervention and delayed intervention, research staff recorded GLC member information, leadership structure, meeting times/places, how the garden was designed/built, workshops offered/attended, fundraising and media events, types of produce harvested, produce use and distribution plans, community resources leveraged, and barriers and future action plans. Student and parent class attendance was recorded at the schools to establish exposure and participation in the intervention. Given that the students were exposed to the TX Sprouts program during school hours, class attendance was high. To measure how well educators completed each session, project staff completed brief process logs, adapted from previous school-based interventions, after each student and parent lesson, to assess TX Sprouts class logistics, including the number of deviations from planned class activities, number of behavioral disturbances, classroom teacher involvement, and student perception/feedback of the lesson’s recipe or taste test of aguas frescas. A survey was developed for class observation and educators’ implementation of TX Sprouts to assess fidelity of program delivery among educators. These logs and surveys permitted constructive feedback, additional coaching from key study personnel, and iterative learning if performance fell below the expected level.

2.10. Data Management

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).41 Ten percent of the participant’s data was double entered to evaluate the quality of the data entered. Kappa statistics were used to assess agreement for categorical variables and the Lin Concordance Correlation Coefficient was used to assess concordance and correlation for continuous variables. Kappa statistics varied from 0.57 to 1.0 and the Lin correlation coefficient varied from 0.79 to 1.0; therefore, there was no need to re-enter all the data.

2.11. Sample Size Estimation

We estimated the power of this study for children using pilot data from five primary variables from LA Sprouts: child vegetable intake (serving/day), BMI z-scores, waist circumference, fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL), and parent vegetable intake.19 We assumed that a cluster average size of 127 children per school would have pre- and post-measurements for vegetable intake, BMI z-scores, and waist circumference, but only 60 children per school for blood glucose values. Table 4 presents the parameters used to obtain the minimum number of schools to test the intervention on the outcomes with a power of 80% for the children’s primary outcomes using a type I error of 0.05, a two-sided test, and assuming equal allocation between the two arms.42,43 The variance (σ2) within schools and the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) to estimate the sample size were obtained from LA Sprouts.19 Therefore, six schools each with 127 children for surveys and measurements and 60 children per school with blood draws, was estimated to be needed to detect the effect size of a decrease in 2.13 mg/dL in fasting glucose, an increase in 0.5 in vegetable (serving/day) intake for the child and parent, a decrease of 0.065 in BMI z-scores, and a decrease of at least 0.02 cm in waist circumference. One additional school per arm was planned to serve as attrition in case a school decided to withdraw participation. For these reasons, a total sample size of 16 schools was used for this study.

Table 4:

Minimum number of schools required evaluating the difference in the effect size between the intervention and control.

| Children (cluster avg. size of n=127 for diet, waist, BMI z-scores and 60 for glucose/insulin values per school) | Parents (cluster avg. size of n=64 per school) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetable Intake | Blood Glucose | BMI Z score | Waist circumference | Parents: Vegetable - Intake | ||

| Type I error level | ICC=0.071 | ICC=0.001 | ICC=0.002 | ICC=0.019 | ICC=0.071 | |

| Effect Size | σ2=0.08 | σ2=40.86 | σ2=0.05 | σ2=0.005 | σ2=0.08 | |

| 0.500 | 2.133 | −0.065 | −0.020 | 0.510 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.8 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 12 |

ICC=intracluster correlation coefficient; σ2=variance within schools from pilot data.

2.12. Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics, graphical analyses, and frequency distributions were used to describe the baseline data between the intervention and delayed intervention arm, accounting for the cluster effect of the children nested in the schools and random assignment at the school level. Summary statistics using cluster effect level varied very little in comparison to the individual level accounting for the cluster effect on binary and continuous variables. For the multinomial variables the cluster level effect is reported. For the multinomial variables the cluster level effect is reported. Children were assumed to be random within the school. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for binary outcomes was defined as the ratio of between-cluster variance to total variance using the estimated variance of the random intercept and the within-cluster variance.44 Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) with the identity link were used to estimate the mean and standard deviations with schools as random clusters for continuous variables and the p-value evaluating differences in the intervention arms were reported. GLMM with the logit link under the binomial distribution were used for binary variables. GLMM with logit link under the cumulative logit distribution were used for ordinal variables.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment and Enrollment

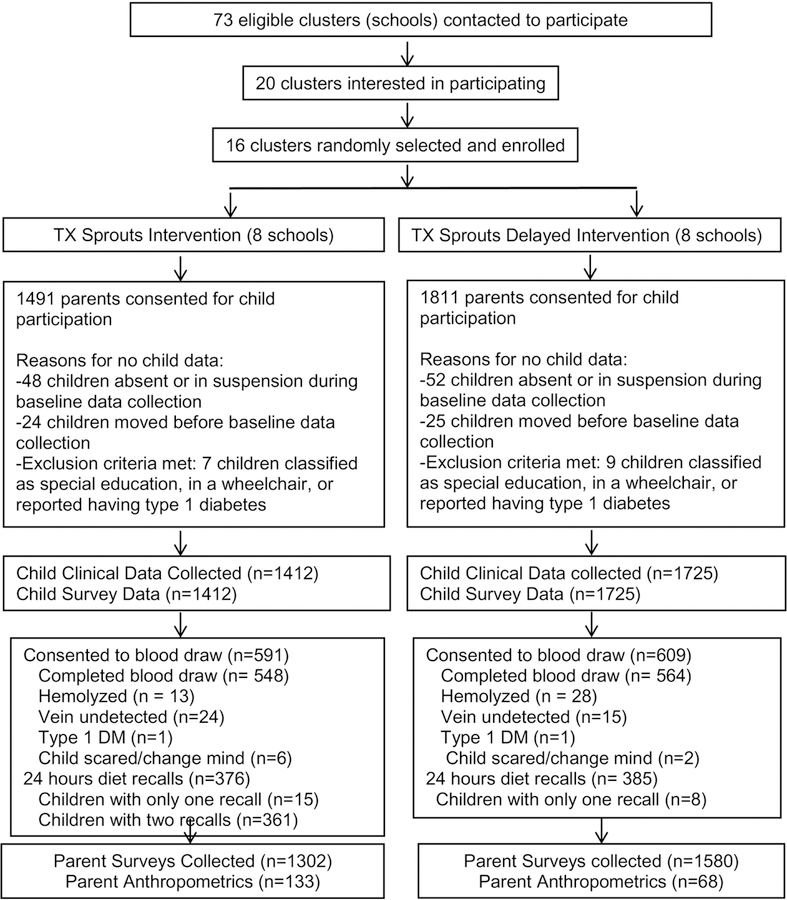

Recruitment is depicted in the CONSORT diagram Figure 2. Of the 4,239 eligible children at the 16 schools, 3,303 children (or 78%) consented to be in the study and the eight randomly assigned intervention schools included 1492 children and the eight randomly assigned control schools included 1811 children. Of those consented, 3,137 children (74% of eligible children or 95% of those consented) completed baseline clinical measures and were in the clinical trial. Of those consented, 3,132 children (or 99.8% of those consented) completed baseline child survey. Approximately 34% (or n=1112) children successfully completed the optional fasting blood draw. Approximately 23% (n=761 children) completed the optional dietary recalls, with 23 children having one recall and 738 children having two dietary recalls at baseline. Approximately 87% (or n=2873) parents completed baseline surveys.

Figure 2.

TX Sprouts Baseline Consort Diagram.

3.2. Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort

Baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups are shown in Table 5. The average age of children was 9.2 years and 47% were female. Approximately 66% were Hispanic, and 69% received free and reduced breakfast/lunch. The average age of the parents/guardians was 37 years, and 87% were female, indicating that the majority of the parents who completed the survey were mothers. The educational attainment levels of the parents differed between groups (p=0.0002), with a higher percentage of parents in the intervention group compared to the control having completed a high school education or some college. There were no other differences in child or parental demographics between the intervention and control groups.

Table 5:

Baseline Child and Parent Demographic Characteristics.

| Total Mean (SE) | Intervention Mean (SE) | Control Mean (SE) | P-value | Cluster correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | n=3,137 | n=1,412 | n=1,725 | ||

| Age (y) | 9.23(0.04) | 9.25(0.08) | 9.20(0.02) | 0.49 | 0.027 |

| Female (%) (SE) | 47.4(0.01) | 47.1(0.01) | 47.7(0.01) | 0.59 | 0.02 |

| Race/ethnicity % (SE) | 0.83 | ||||

| White | 20.8(0.05) | 22.9(0.08) | 18.20(0.04) | 0.05 | |

| Black | 9.7(0.01) | 9.6(0.02) | 9.93(0.01) | 0.17 | |

| Hispanic | 64.4(0.05) | 62.5(0.09) | 66.8(0.04) | 0.03 | |

| Nat.Amer/Asian/Pac.Island/Other | 3.6(0.00) | 3.2(0.01) | 4.1(0.01) | 0.55 | |

| Missing (n) | 302 | 130 | 172 | ||

| Eligible FRL %(SE) | 68.9(0.04) | 66.6(0.07) | 71.6(0.05) | 0.77 | 0.03 |

| Missing (n) | 370 | 148 | 222 | ||

| Parent/Guardian | n=2,873 | n=1,296 | n=1,577 | ||

| Age (y) | 36.92(0.31) | 37.2(0.49) | 36.6(0.36) | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Missing (n) | 279 | 108 | 171 | ||

| Female % (SE) | 87.1(0.01) | 86.6(0.01) | 87.7(0.01) | 0.92 | 0.104 |

| Missing (n) | 65 | 23 | 42 | ||

| Relationship to Child %(SE) | 0.26 | ||||

| Parent | 97.6(0.00) | 97.3(0.00) | 97.9(0.00) | 0.744 | |

| Grandparent/Other | 2.4(0.00) | 2.7(0.00) | 2.1(0.00) | 0.744 | |

| Missing (n) | 42 | 19 | 23 | ||

| Race or ethnicity %(SE) | 0.93 | ||||

| White | 23.9(0.05) | 26.3(0.09) | 20.1(0.04) | 0.044 | |

| Black | 8.6(0.01) | 8.0(0.02) | 9.3(0.01) | 0.197 | |

| Hispanic | 64.3(0.05) | 62.5(0.10) | 66.4(0.05) | 0.027 | |

| Nat. Amer/Asian/Pac.Island/Other | 3.3(0.01) | 3.2(0.01) | 3.4(0.01) | 0.566 | |

| Missing (n) | 66 | 28 | 38 | ||

| Education completed %(SE) | 0.93 | ||||

| Less than 8th grade | 13.1(0.02) | 11.2(0.04) | 15.4(0.03) | 0.098 | |

| Finished 8th grade | 9.9(0.02) | 8.8(0.03) | 11.2(0.02) | 0.153 | |

| Some High School | 13.0(0.02) | 12.3(0.03) | 13.7(0.02) | 0.103 | |

| High school graduate /GED | 20.5(0.01) | 22.5(0.01) | 18.1(0.01) | 0.054 | |

| Some college / vocational school | 23.8(0.02) | 24.7(0.04) | 22.7(0.03) | 0.044 | |

| College graduate | 15.0(0.03) | 15.9(0.05) | 13.9(0.03) | 0.082 | |

| Graduate or professional training | 4.8(0.01) | 4.7(0.01) | 5.0(0.01) | 0.401 | |

| Missing (n) | 110 | 52 | 58 |

FRL=free and reduced lunch; Nat. Amer=Native American; Pac Island=Pacific Islander; GED=General Education Development.

Child and parent baseline clinical and dietary data are displayed in Table 6. Forty-six percent of the children had overweight or obesity, and 75% of parents had overweight or obesity. There are statistically significant differences in weight status categories (p=0.004), with the intervention children compared to control children having a lower prevalence of overweight (16.7 vs. 20.7%). Intervention compared to control children have higher diastolic blood pressure rates (68.7 vs. 66.1 mmHg; p=0.01) and higher fruit intake (1.0 vs. 0.8 serving/day; p=0.02).

Table 6:

School-level Baseline Child and Parent Clinical and Dietary Variables accounting for the size of the school.

| Total Mean (SE) | Intervention Mean (SE) | Control Mean (SE) | P-value | Cluster correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | n=3,137 | n=1,412 | n=1,725 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 71.0 (0.42) | 71.3 (0.61) | 70.7 (0.63) | 0.42 | 0.0126 |

| Missing (n) | 16 | 8 | 8 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.1 (0.13) | 20.0 (0.20) | 20.1 (0.18) | 0.93 | .0061 |

| Missing (n) | 8 | 6 | 3 | ||

| BMI z-score | 0.79 (0.03) | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.81 (0.04) | 0.61 | .007 |

| BMI percentile | 70.6 (0.73) | 70.1 (1.1) | 71.18 (.94) | 0.51 | .0053 |

| Weight Status %(SE) | 0.11 | ||||

| Normal weight/ Underweight | 54.0 (0.01) | 55.7 (0.02) | 52.0 (0.02) | 0.021 | |

| Overweight | 18.4 (0.01) | 16.3 (0.01) | 21.0 (0.01) | 0.053 | |

| Obese | 27.5 (0.01) | 28.0 (0.02) | 27.0 (0.01) | 0.032 | |

| Percentage body fat | 26.0 (0.30) | 25.8 (0.44) | 26.1 (0.42) | 0.73 | 0.012 |

| Missing (n) | 9 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Blood pressure | |||||

| Systolic (mmHg) | 103.4 (0.57) | 104.2 (0.86) | 102.5 (0.62) | 0.16 | 0.0302 |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 67.6 (0.59) | 68.8 (0.82) | 66.1 (0.53) | 0.01 | 0.0495 |

| Missing (n) | 17 | 6 | 11 | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 92.5 (1.4) | 91.3 (2.3) | 94.1 (1.7) | 0.36 | 0.2763 |

| Missing (n) | 6 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Percentage HbA1c | 5.2 (0.03) | 5.3 (0.05) | 5.2 (0.05) | 0.55 | 0.0849 |

| Missing (n) | 37 | 37 | 0 | ||

| Dietary Intake from Screener: | |||||

| Vegetable intake (freq/yest) | 2.9 (0.05) | 2.8 (0.21) | 3.0 (0.21) | 0.51 | 0.0315 |

| Missing (n) | 48 | 27 | 21 | ||

| Fruit intake (freq/yest) | 1.3 (0.02) | 1.3 (0.04) | 1.2 (0.03) | 0.28 | 0.0034 |

| Missing (n) | 17 | 10 | 7 | ||

| SSB intake (freq/yest) | 0.59 (0.01) | 0.57 (0.03) | 0.61 (0.03) | 0.35 | 0.0087 |

| Missing (n) | 20 | 11 | 9 | ||

| Dietary Intake from Recall: | (n=738) | (n=361) | (n=377) | ||

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 1468.35 (20.1) | 1474.08(32.6) | 1461.58(22.8) | 0.85 | 0.0122 |

| Carbohydrate (g/d) | 184.5 (2.6) | 185.4 (4.09) | 183.3 (3.1) | 0.88 | 0.0177 |

| Fat (g/d) | 56.7 (1.0) | 56.8 (1.6) | 56.7 (1.2) | 0.97 | 0.0142 |

| Protein (g/d) | 59.3 (0.86) | 59.7 (1.4) | 58.7 (0.98) | 0.52 | NA |

| Fiber (g/d) | 12.6 (0.22) | 12.7 (0.36) | 12.6 (0.26) | 0.93 | 0.0112 |

| Added sugar (g/d) | 38.2 (0.94) | 38.5 (1.3) | 37.9 (1.4) | 0.88 | 0.0152 |

| Vegetable (serv/d) | 1.6 (0.05) | 1.7 (0.08) | 1.6 (0.05) | 0.31 | 0.0037 |

| Fruit (serv/d) | 0.9 (0.05) | 1.0 (0.08) | 0.8 (0.05) | 0.02 | 0.0092 |

| SSB (serv/d) | 0.49 (0.03) | 0.5 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.04) | 0.71 | 0.0003 |

| Healthy Eating Index Total | 53.6 (0.45) | 53.6 (0.62) | 53.6 (0.65) | 0.92 | 0.0005 |

| Score | |||||

| Parent | n=2,873 | n=1,296 | n=1,577 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.7 (0.22) | 29.8 (0.32) | 29.5 (0.31) | 0.42 | 0.0096 |

| Missing (n) | 751 | 335 | 416 | ||

| Weight Status %(SE) | 0.41 | ||||

| Normal weight/ Underweight | 24.9 (0.01) | 25.7 (0.02) | 23.9 (0.02) | 0.0502 | |

| Overweight | 32.6 (0.01) | 31.6 (0.01) | 33.7 (0.01) | 0.0378 | |

| Obese | 42.5 (0.01) | 42.7 (0.02) | 42.3 (0.02) | 0.0309 | |

| Dietary Intake from Screener: | (%)SE | %(SE) | %(SE) | ||

| Ate green salad yesterday | 15.4 (0.01) | 14.2 (0.02) | 16.6 (0.02) | 0.28 | 0.0805 |

| Missing (n) | 156 | 70 | 86 | ||

| Ate other vegetables yesterday | 23.3 (0.01) | 22.6 (0.11) | 23.9 (0.10) | 0.63 | 0.0441 |

| Missing (n) | 122 | 55 | 67 | ||

| Ate fruit, excluding juice, yesterday | 36.7 (0.01) | 36.9 (0.01) | 37.0 (0.01) | 0.95 | 0.0262 |

| Missing (n) | 109 | 53 | 56 |

NA: not possible to estimate due to convergence issue. Freq/yest=frequency yesterday; SSB=sugar sweetened beverages; g/d=grams per day; serv/d=servings per day.

4. Discussion

TX Sprouts targeted 16 elementary schools in and around Austin, TX serving students from families which are predominately Hispanic, low-income, and have a high prevalence of overweight and obesity. Hispanics are disproportionately impacted by obesity and related metabolic diseases, such as T2D and metabolic syndrome,4,45 and low-income families also have higher rates of obesity and related diseases compared to middle- and high-income families.46 In addition, lack of access and availability of fresh fruits and vegetables (FV) is a likely cause for low consumption in Hispanic youth.47 A gardening intervention provides increased access and availability of FV. Therefore, an intervention teaching gardening can increase access, availability, and intake of FV in a high-risk, low-income, Hispanic population.

This is the first cluster-RCT to test the effects of a gardening, nutrition, and cooking program on obesity and related metabolic disorders. Although numerous other RCTs have shown that a garden-based intervention can result in improvements in dietary intake and related dietary behaviors,13,48–50 few have examined obesity parameters and none have examined metabolic outcomes using a cluster-RCT approach. The seven-week community garden and nutrition intervention called “Growing Healthy Kids,” which included a concentrated cooking component and targeted primarily low-income Hispanic families, resulted in significant increases in child FV intake and FV availability in the home.50 This program also resulted in a significant improvement in BMI, with 17% of the children no longer being classified as having overweight or obesity after the program; however, this was not a controlled study.50 The Texas! Grow! Eat! Go! (TGEG) pilot results found that 3rd grade students exposed to a five-month gardening and exercise intervention had reductions in obesity prevalence; however, this was a within-subject analysis and the pilot study did not include a control group.51 Results for the full TGEG study are still underway. The pilot LA Sprouts trial found that a 12-week after-school gardening, nutrition, and cooking intervention increased vegetable and dietary fiber intake and reduced BMI and waist circumference.19 TX Sprouts expanded on the LA Sprouts program by: (a) using a cluster randomized school design; (b) implementing the program during school hours; (c) increasing sample size; (d) lengthening the intervention period to one school year; e) collecting comprehensive metabolic measurements on the child; (f) conducting more comprehensive blood assays; (g) collecting dietary recalls; (h) enhancing family lessons; (i) collecting more parental data; and (j) developing, implementing, and evaluating sustainability strategies.

The TX Sprouts curriculum is culturally tailored and targets a reduction in added sugar intake (specifically sugar sweetened beverages) and an increase in dietary fiber, by encouraging the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. We have consistently shown that diets high in added sugar and low in dietary fiber are linked to increased type 2 diabetes risk and visceral adiposity in Hispanic children.52,53 Every lesson included either a cooking activity or taste test, which have been shown to be a key component at increasing intake.54 Every lesson also included an agua fresca, which we also feel is key strategy to reducing added sugar intake adiposity in this population. In addition, every lesson is mapped on the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) standardized test, which means the lessons should be seamlessly integrated into the current school curriculum.

This study is a unique partnership with many community groups across Austin, including Seton Healthcare Family, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, Sustainable Food Center, UT Austin and UTHealth School of Public Health (UTHealth SPH), and five independent school districts in and around Austin. Nurses from Seton were involved in the blood collection aspect of the study, doctors from Seton assisted in reporting adverse events back to the parents, over 300 trained undergraduate students from UT Austin and UT School of Public Health volunteered on the project, over 30 Master Gardeners from AgriLife Extension are working on this study, community leaders and local farmers from Sustainable Food Center are assisting with the sustainability trainings at each of the schools, and administrators and teachers from all 16 schools are integrated into various components of the intervention. These partnerships are key to making sure all stakeholders are heavily invested in the program and will help to ensure the sustainability of the program moving forward.

TX Sprouts utilizes paid nutrition and gardening educators to deliver the program to the students and parents. The goal of this study was to assess the effects of the developed and intended program on health outcomes, without all the deviations and modifications that would likely occur if delivered by current school teachers. This approach allows the school teachers to observe and learn from the trained educators how to teach in an outdoor setting, how to garden, and how to implement and integrate garden-based curriculum into their current lessons. In addition, this program provides schoolteachers with trainings to be able to continue to teach the lessons in the garden.

Sustainability and maintenance of school gardens is always challenging. A review of garden-based interventions indicated that several recurring strategies are needed for sustainability.55 A common strategy mentioned is the importance of enlisting stakeholder input (i.e., children, teachers, principals, school staff, parents, and community groups) in the development, implementation, and maintenance of the program.56–59 This study has taken several steps to ensure stakeholders were involved and integrated throughout the whole program. Before each garden was built, Garden Leadership Committees (GLC) were formed at each school, which consisted of interested administrators, teachers, parents, and even students. The GLCs helped design and build the gardens, as well as establish a maintenance plan for the gardens. For example, some GLCs established family adoption plans, where families take turns watering/weeding the garden weekly, and/or scheduled monthly garden workdays with families and/or local community groups. The Sustainable Food Center provided a series of sustainability workshops to the GLCs at each school in both the intervention year and the year following. In addition, TX Sprouts provided “train the teacher” workshops to all interested school teachers and school staff during the intervention year and the year following to teach them how to teach in a garden setting and integrate gardening, nutrition, and cooking activities into existing school lessons. Some of the GLCs also hosted a series of media events or promotional activities (such as fundraising events and meal sharing occasions) in the garden as a way to incorporate the garden and the gardening program into existing school infrastructure and activities.

5. Conclusions

The TX Sprouts study is an ongoing cluster-RCT assessing the impact of a school-based gardening, nutrition and cooking intervention on dietary intake, obesity markers, and related metabolic disease risks in over 3,100 primarily Hispanic, low-income 3rd-5th grade students and their parents. This study expands on current garden literature by including a one-year long cluster-RCT, including comprehensive obesity and metabolic assessments on children, incorporated nutrition, cooking, and gardening lessons into existing school curriculum, addition of an intense parental component and evaluation, and addition of numerous sustainability strategies and assessment of these strategies. Results from this study may help inform future planning of programs targeting prevention of obesity and related chronic diseases in children. Findings may also help promote school-based nutrition, cooking, and gardening education programs in order to improve children’s dietary behaviors and metabolic health status.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank all the children and their families for participating in this study. We would like to thank all of the school stakeholders (i.e., administrators, teachers and staff) for allowing us to teach this program in the schools. We would like to thank the following staff that was instrumental in the implementation of this program: Tatiana Antonio, Bonnie Martin, Shirene Garcia, Michele Hockett Cooper, Hannah Ruisi, Andrea Snow, Liz Metzler, Meg Mattingly, and Cindy Haynie. We would also like to thank Bianca Bidiuc Peterson and Sari Albornoz from the Sustainable Food Center for collaborating with us on this project. We would also like to thank Home Depot for their garden supply donations and attendance at all school garden builds. Finally, we would like to thank all of the University of Texas at Austin undergraduate students for all their hard work helping us collect data, build the gardens, and teach the classes.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [1R01HL123865, 2015–2020), Whole Kids Foundation, Home Depot.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical Trials Number: NCT02668744

References:

- 1.Bureau USC. Quick Facts Texas https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/tx/POP010210. Accessed March 1st, 2019.

- 2.Goran MI, Lane C, Toledo-Corral C, Weigensberg MJ. Persistence of pre-diabetes in overweight and obese Hispanic children: association with progressive insulin resistance, poor beta-cell function, and increasing visceral fat. Diabetes 2008;57(11):3007–3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goran MI, Nagy TR, Treuth MT, et al. Visceral fat in Caucasian and African-American pre-pubertal children. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:1703–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz ML, Weigensberg MJ, Huang T, Ball GDC, Shaibi GQ, Goran MI. The metabolic syndrome in overweight Hispanic youth and the role of insulin sensitivity. JCEM 2004;89:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SPAN 2015–2016, Michael & Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living at theUniversity of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health withfunding from the Texas Department of State Health Services Available at: https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/dell/. Accessed March 1st, 2019.

- 6.Childhood Obesity Action Network (2009). “Texas State Obesity Profile.” National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality, Child Policy Research Center, and Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, Available at: http://nschdata.org/Viewdocument.aspx?item=565. Last accessed September 30, 2013.

- 7.Consumer Price Index-all urban consumers. United States Bureau of Labor Statistics Available at: http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/outside.jsp?survey=cu; last accessed on June 10th, 2010.

- 8.Finkelstein EA, Strombotne KL. The economics of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 91(5):1520S–1524S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhouser ML, Thompson B, Coronado GD, Solomon CC. Higher fat intake and lower fruit and vegetables intakes are associated with greater acculturation among Mexicans living in Washington State. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104(1):51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dave JM, Evans AE, Saunders RP, Watkins KW, Pfeiffer KA. Associations among food insecurity, acculturation, demographic factors, and fruit and vegetable intake at home in Hispanic children. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109(4):697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilmers A, Hilmers DC, Dave J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health 2012;102(9):1644–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherer PM. The benefits of parks: Why American needs more city parks and open space Avaiable at: http://www.tpl.org. Last accessed on 5/10/06.

- 13.McAleese JD, Rankin LL. Garden-based nutrition education affects fruit and vegetable consumption in sixth-grade adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107(4):662–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris JL, Zidenberg-Cherr S. Garden-enhanced nutrition curriculum improves fourth-grade school children’s knowledge of nutrition and preferences for some vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc 2002;102(1):91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berti PR, Krasevec J, FitzGerald S. A review of the effectiveness of agriculture interventions in improving nutrition outcomes. Public Health Nutr 2004;7(5):599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viola A Evaluation of the Outreach School Garden Project: building the capacity of two Indigenous remote school communities to integrate nutrition into the core school curriculum. Health Promot J Austr 2006;17(3):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris J, Neustadter A, Zidenberg-Cherr S. First grade gardeners are more likely to taste vegetables. California Agriculture 2001;55:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang M, Rauzon S, Studer N, et al. Exposure to a comprehensive school intervention increases vegetable consumption. J Adolesc Health 2010;46:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatto NM, Martinez LC, Spruijt-Metz D, Davis JN. LA sprouts randomized controlled nutrition, cooking and gardening programme reduces obesity and metabolic risk in Hispanic/Latino youth. Pediatr Obes 2017;12(1):28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez LC, Gatto NM, Spruijt-Metz D, Davis JN. Design and methodology of the LA Sprouts nutrition, cooking and gardening program for Latino youth: A randomized controlled intervention. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;42:219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Learn, Grow, Eat & Grow! 2014. Available at: http://jmgkids.us/LGEG/. Last accessed March 1st, 2015

- 22.Bronfenbreener U The ecology of human development Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes 1993;56(1):96–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007–2009. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. Accessed July 21, 2012.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: CDC growth Charts Atlanta, GA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2000. (U.S. Publ. no. 314). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wardle J, Robb K, Johnson F. Assessing socioeconomic status in adolescents: the validity of a home affluence scale. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56(8):595–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiagarajah K, Fly AD, Hoelscher DM, et al. Validating the food behavior questions from the elementary school SPAN questionnaire. J Nutr Educ Behav 2008;40(5):305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baranowski T, Davis M, Resnicow K, et al. Gimme 5 fruit, juice, and vegetables for fun and health: outcome evaluation. Health Educ Behav 2000;27(1):96–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domel SB, Baranowski T, Davis H, Leonard SB, Riley P, Baranowski J. Measuring fruit and vegetable preferences among 4th- and 5th-grade students. Prev Med 1993;22(6):866–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans A, Ranjit N, Hoelscher D, et al. Impact of school-based vegetable garden and physical activity coordinated health interventions on weight status and weight-related behaviors of ethnically diverse, low-income students: Study design and baseline data of the Texas, Grow! Eat! Go! (TGEG) cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2016;16:973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fram MS, Ritchie LD, Rosen N, Frongillo EA. Child experience of food insecurity is associated with child diet and physical activity. J Nutr 2015;145(3):499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Block G, Gillespie C, Rosenbaum EH, Jenson C. A rapid food screener to assess fat and fruit and vegetable intake. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(4):284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arble DM, Bass J, Laposky AD, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW. Circadian timing of food intake contributes to weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(11):2100–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service: U.S. household food security survey module: Three-stage design, with screeners Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx. Last accessed January 15th, 2015.

- 35.Feskanich D, Sielaff BH, K C. Computerized Collection and Analysis of Dietary Intake Information. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1989;30:47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson RK, Driscoll P, Goran MI. Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in young children. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96(11):1140–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sciences NCIDoCCP. Devoping the Heathy Eating Index 2015. Available at: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/developing.html. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 38.Mathews D, Hosker J, Rudenski A, Naylor B, Treacher D, Turner R. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentration in man. Diabetologia 1985;28:412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes care 2018;41(Suppl 1):S13–s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.RedCap: Research Electronic Data Capture. Clinical & Translational Science Awards http:project-redcap.org/.

- 42.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray D. Design and analysis of group-randomized trial New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu S, Crespi CM, Wong WK. Comparison of methods for estimating the intraclass correlation coefficient for binary responses in cancer prevention cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33(5):869–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goran MI, Bergman RN, Avilla Q, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance and reduced beta-cell function in overweight Latino children with a positive family history of type 2 diabetes. JCEM 2004;89(1):207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief 2010(50):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubowitz T, Heron M, Bird CE, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and fruit and vegetable intake among whites, blacks, and Mexican Americans in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87(6):1883–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans A, Ranjit N, Rutledge R, et al. Exposure to multiple components of a garden-based intervention for middle school students increases fruit and vegetable consumption. Health Promot Pract 2012;13(5):608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parmer SM, Salisbury-Glennon J, Shannon D, Struempler B. School gardens: an experiential learning approach for a nutrition education program to increase fruit and vegetable knowledge, preference, and consumption among second-grade students. J Nutr Educ Behav 2009;41(3):212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castro DC, Samuels M, Harman AE. Growing healthy kids: a community garden-based obesity prevention program. Am J Prev Med 2013;44(3 Suppl 3):S193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spears-Lanoix EC, McKyer EL, Evans A, et al. Using Family-Focused Garden, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Programs To Reduce Childhood Obesity: The Texas! Go! Eat! Grow! Pilot Study. Child Obes 2015;11(6):707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis J, Ventura E, Weigensberg M, et al. The relation of sugar intake to beta-cell function in overweight Latino children Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:1004–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis JN, Alexander KE, Ventura EE, et al. Associations of dietary sugar and glycemic index with adiposity and insulin dynamics in overweight Latino youth. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86(5):1331–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Landry M, Markowitz A, Asigbee F, Gatto N, Spruijt-Metz D, Davis J. Cooking and gardening behaviors and improvements in dietary intake in Hispanic/Latino youth. Childhood Obesity 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Davis JN, Spaniol MR, Somerset S. Sustenance and sustainability: maximizing the impact of school gardens on health outcomes. Public Health Nutr 2015;18(13):2358–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Somerset S, Markwell K. Impact of a school-based food garden on attitudes and identification skills regarding vegetables and fruit: a 12-month intervention trial. Public Health Nutr 2009;12(2):214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ratcliffe MM, Merrigan KA, Rogers BL, Goldberg JP. The effects of school garden experiences on middle school-aged students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors associated with vegetable consumption. Health Promot Pract 2011;12(1):36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gibbs L, Staiger PK, Johnson B, et al. Expanding children’s food experiences: the impact of a school-based kitchen garden program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2013;45(2):137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morgan PJ, Warren JM, Lubans DR, Saunders KL, Quick GI, Collins CE. The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutr 2010;13(11):1931–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]