Abstract

PURPOSE:

The Distress Thermometer (DT) includes a measure of cancer-related distress and a list of self-reported problems. This study evaluated the utility of the DT problem list in identifying concerns most associated with distress and poorer quality of life (QOL) in survivors of gynecologic cancer.

METHODS:

Demographic, clinical, psychosocial functioning, and DT data were described among 355 women participating in a gynecologic cancer cohort. Problems from the DT list were ranked by prevalence, distress, and QOL. Logistic regression models explored factors associated with problems that were common (≥ 25% prevalence) and associated with distress and QOL.

RESULTS:

The average age of participants was 59.9 years (standard deviation [SD], 10.8 years). Most participants were non-Hispanic white (97%) and had ovarian (44%) or uterine (42%) cancer. The mean DT score was 2.7 (SD, 2.7); participants reported a mean of 7.3 problems (SD, 5.9 problems). The most common problems were fatigue (53.6%), worry (49.9%), and tingling (46.3%); least common problems were childcare (2.1%), fevers (2.1%), and substance abuse (1.1%). Report of some common problems, including tingling, sleep, memory, skin issues, and appearance, was not associated with large differences in distress or QOL. In contrast, some rarer problems such as childcare, treatment decisions, eating, housing, nausea, and bathing/dressing were associated with worse distress or QOL. Younger age, lower income, and chemotherapy were risk factors across common problems that were associated with worse distress or QOL (fatigue, nervousness, sadness, fears, and pain).

CONCLUSION:

The DT problem list did not easily identify concerns most associated with distress and low QOL in patients with gynecologic cancer. Adaptations that enable patients to report their most distressing concerns would enhance clinical utility of this commonly used tool.

INTRODUCTION

Distress, a common complication of cancer and its treatment,1,2 represents a broad multifactorial continuum of negative emotions and outcomes, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, fears, and social and functional problems.3 Distress reduces quality of life (QOL) and satisfaction with quality of care and is associated with reduced treatment adherence, which may mediate worse cancer outcomes.2,4,5 Therefore, the psychosocial sequelae of cancer and their management have increasingly been recognized as integral to cancer care.2,6 Since 2012, the Commission on Cancer has mandated to cancer centers that patients with cancer be screened for distress during the first course of treatment at least one time.7

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Thermometer (DT) has been widely adopted to measure distress in patients with cancer. The DT consists of a single-item continuous scale, which is an accurate, efficient, and acceptable short screening tool for patients to self-quantify distress8,9; and an accompanying problem list on which patients identify specific problems they have recently encountered. According to the NCCN distress management guidelines, the intention of the DT problem list is to “identify key issues of concern and … determine the best resources … to address the patient’s concerns.”14

Across studies, the continuous scale component of the DT is far more commonly reported than the problem list.12 The few previous studies that have evaluated the problem list reported the problem list items as predictors, with the DT score or other psychosocial measures as outcomes.13-16 Few studies have considered the problem items as outcomes themselves, so their clinical utility is lesser known than that of the DT distress score.1,17-19 One possible explanation for the underreporting of the DT problem list is that its interpretation and clinical application are less straightforward than those of the DT score. In addition, many cancer programs do not have the staff to address all problems patients may report, and studies have shown that screening positive for elevated distress on the DT does not always lead to referrals to appropriate services.20 This raises the question of whether simply checking problems from a predetermined list fulfills the NCCN’s intended purpose of identifying patients’ key problems. For the purposes of our study, we translated “key” to mean “urgent,” defining urgency as being associated with higher DT scores and lower QOL.

Our goals were to assess self-reported DT problems based on a cohort of individuals with gynecologic cancers along with self-reported DT and QOL scores and to identify factors associated with the most prevalent and potentially urgent problems. Gynecologic cancers include uterine, ovarian, cervical, and vaginal and vulvar cancers. In the United States, currently approximately 1.3 million individuals live with a gynecologic cancer diagnosis, and this number is projected to increase to > 1.5 million by 2026.21 Emotional distress varies significantly by cancer type and sex, with women demonstrating higher rates than men.22 Patients with gynecologic cancers report higher DT scores than patients with many other cancers, and these patients also have a diverse set of concerns, making them an important and ideal population in which to examine the DT problem list.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

The Gynecologic Oncology–Life After Diagnosis (GOLD) study is an ongoing prospective cohort study initiated in March 2017 at the University of Minnesota with planned follow-up surveys every 6 months for up to 5 years. English-speaking individuals age 18 years and older diagnosed with ovarian, cervical, uterine, vaginal, or vulvar cancer and recruited through the University of Minnesota Gynecologic Oncology service line are eligible to participate in the study. Time since diagnosis is not an eligibility criterion, although the majority of patients have been recruited after treatment and/or in surveillance.

The GOLD study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (No. 1612S01581). All participants provided written informed consent before being enrolled on the study and have signed a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act form agreeing to have their medical record data accessed by the GOLD research team for clinical data abstraction.

Recruitment

Participants were identified using the electronic medical record and invited in person to participate at a follow-up clinic visit (March 2017 to present) or via mail (June to October 2018). To date, 408 participants have enrolled in the GOLD study, of whom 156 (95% of patients approached) were recruited in clinic and 252 (42% of patients approached) were recruited by mail. Of these 408 individuals, 381 (93%) completed the baseline survey before this analysis.

Data Collection

At study entry, participants were invited to complete a comprehensive baseline survey. The survey was administered by paper or online via REDCap23 based on participant preference. The survey collected information on demographics; self-reported clinical data; QOL; emotional health measures including depression, anxiety, distress, posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth, hopelessness, resilience, self-efficacy, and coping; and health behaviors. Clinical data were abstracted from the electronic medical record, including cancer type, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage at diagnosis, histology, treatments received (chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation), and outcomes including recurrence and death.

Measures

The main outcome of this study was self-reported sources of distress (problems) endorsed by participants completing the problem list of the DT, version 1.2016.24 The DT is composed of 2 components. First is a single-item visual analog scale on which patients rate their overall distress, phrased as follows: “Please select the number that best describes how much distress you have been experiencing in the past week including today. (0 = No Distress, 10 = Extreme Distress)”; a cutoff score of 4 or higher is deemed as likely reflecting clinically significant distress.8,24 The second component is an accompanying problem list including 39 items in practical, family, emotional, spiritual/religious, and physical domains, phrased as follows: “Please indicate if any of the following has been a problem for you in the past week including today. Be sure to mark YES or NO for each.”25

We measured QOL in this patient population using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G) scale, which measures QOL outcomes in the following 4 domains: physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being.26,27 Totals scores (0-108) across subscales are aggregated from the individual items, with higher scores indicating greater QOL.

Clinical and demographic predictors of self-identified problems were categorized as follows: cancer type (ovarian, cervical, uterine, vaginal, or vulvar cancer); stage at diagnosis (early stage I and II or advanced stage III and IV), time since diagnosis (< 1, 1 to < 2, 2 to < 5, or ≥ 5 years); receipt of chemotherapy including targeted therapies or immunotherapy (yes or no); receipt of radiation (yes or no); age at baseline (continuous); receipt of college degree (yes or no); annual household income (< $50,000, $50,000-$99,999, ≥ $100,000, or prefer not to answer); partner status (married or partnered or single including separated, divorced, widowed, or never married); and residence (urban or rural) based on zip or Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes.28

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were restricted to baseline data. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort were summarized using descriptive statistics; means and standard deviations (SDs) and frequencies and percentages are provided. We visualized full DT and QOL score distributions for different subpopulations as violin plots. To describe how commonly each problem was reported in our population, we ranked the self-reported items on the DT problem list by prevalence. We also compared average distress and QOL (total FACT-G scores) in participants who did and did not endorse a particular problem to describe the potential urgency of each problem. We then explored demographic and clinical factors associated with the presence of selected problems using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. Given restrictions in available degrees of freedom, we excluded residence, time since diagnosis, and receipt of radiation from our final model, which were not statistically significantly associated with any of the outcomes in the univariable or reduced multivariable models. Our final model included age, partner status, having a college degree, annual household income, advanced stage, receipt of chemotherapy, and cancer type. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

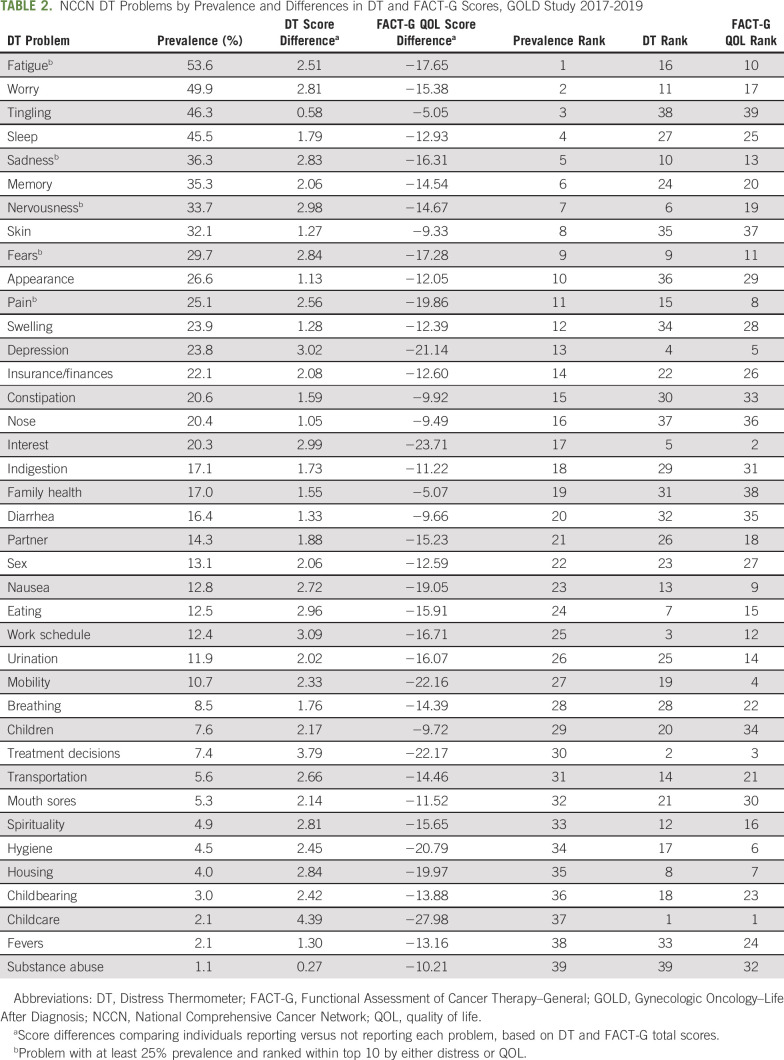

At the time of analysis, 381 individuals completed the baseline survey, of whom 355 completed the DT questionnaire. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The average age at the time of the survey was 59.9 years (SD, 10.8 years), and the majority of participants were non-Hispanic white (97%). Most participants were diagnosed with ovarian cancer (44%) or uterine cancer (42%); the remaining were diagnosed with cervical cancer (10%) or vaginal or vulvar cancer (5%). Less than half of participants (43%) had at least a college degree, and 34% had annual household incomes of < $50,000. Most participants (96%) were diagnosed within 5 years of study enrollment, and 60% were originally diagnosed with early-stage cancer. Among all participants, 93% had surgery, 61% had chemotherapy, and 25% had radiation therapy.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline, GOLD Study 2017-2019

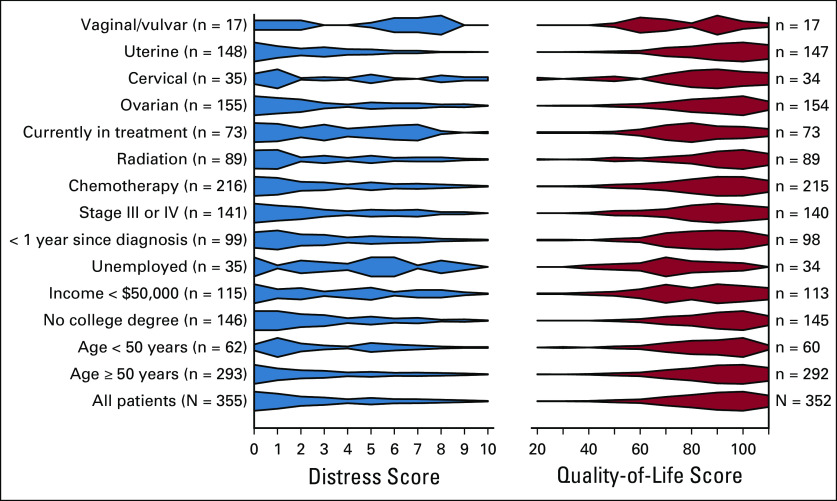

Approximately one third of the participants (30%) reported a DT score of ≥ 4, indicating clinically meaningful distress. The average number of self-identified problems was 7.3 (SD, 5.9 problems), and this increased to 12.6 problems (SD, 5.7 problems) among participants with a DT score ≥ 4. DT scores (higher DT scores indicated greater distress) and QOL scores (higher QOL scores signified greater QOL) were inversely correlated in our study population (r = −0.66, P < .0001), suggesting that distress and QOL are related but distinct concepts. Visualization of the scores by demographic and treatment groups indicated scores were skewed for all groups (right-skewed DT scores and complementary left-skewed QOL scores; Appendix Fig A1, online only). Some subgroups indicated higher than average distress and lower than average QOL, such as individuals currently in treatment, with low incomes, without employment, or with vaginal or vulvar cancers.

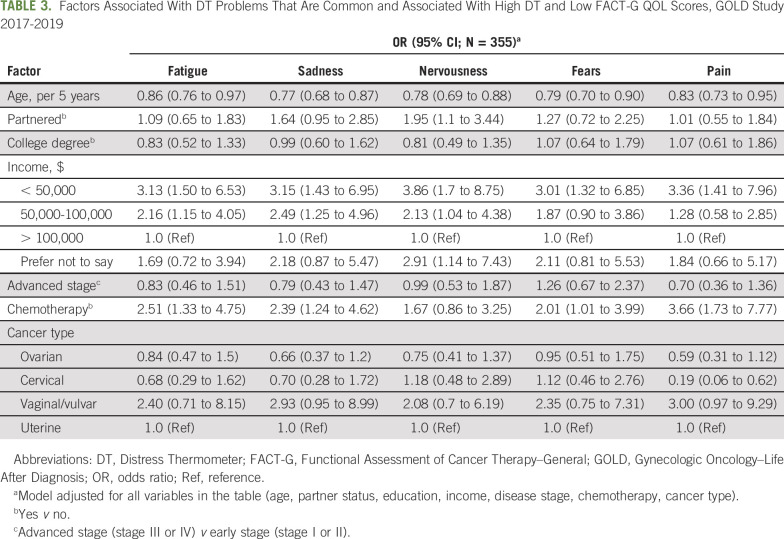

Table 2 lists all problems from the DT ranked by prevalence. We also ranked problems by differences in average distress and QOL scores, comparing those reporting to those not reporting each problem. The most commonly reported problems were fatigue (53.6%), worry (49.9%), and tingling (46.3%); the least common problems were childcare (2.1%), fevers (2.1%), and substance abuse (1.1%). Rankings by prevalence, however, differed substantially from rankings by distress or QOL. Those who reported the most prevalent problems did not have greater distress or lower QOL scores than those who did not report the problem; examples included tingling, sleep, memory, skin issues, and appearance. Some other problems were rare but associated with large distress or QOL differences, such as childcare, treatment decisions, eating, housing, school/work, nausea, bathing/dressing, getting around, and loss of interest in usual activities. Rankings by distress and QOL score differences were generally similar, with the exception of a few problems that ranked high by QOL but not by distress, including getting around and bathing/dressing, or that ranked high by distress but not QOL, such as school/work and nervousness.

TABLE 2.

NCCN DT Problems by Prevalence and Differences in DT and FACT-G Scores, GOLD Study 2017-2019

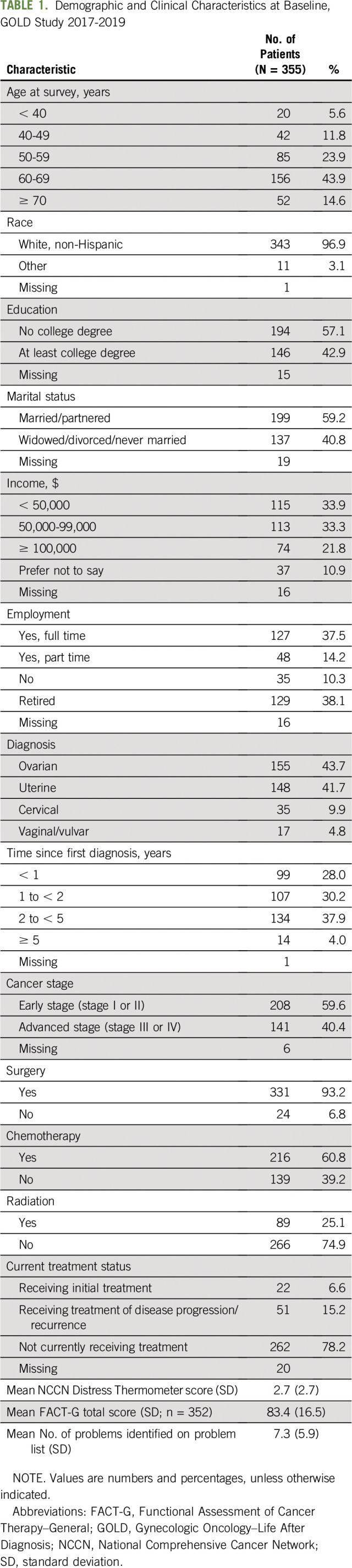

Only 5 problems were both common (at least 25% prevalence) and ranked within the top 10 by either distress or QOL; these were fatigue, sadness, nervousness, fears, and pain. Multivariable associations of potential risk factors for these 5 problems are listed in Table 3. Older age was associated with lower odds of reporting any of these problems (per additional 5 years; odds ratio [OR], range, 0.77-0.86; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.97). Lower annual household incomes were associated with greater odds of reporting all 5 problems (< $50,000 v > $100,000: OR, range, 3.01-3.86; 95% CI, 1.32 to 8.75), and middle incomes were associated with greater odds of reporting fatigue, sadness, and nervousness ($50,000-100,000 v > $100,000: OR, range, 2.13-2.49; 95% CI, 1.04 to 4.96). Receipt of chemotherapy was associated with increased odds of reporting fatigue, sadness, fears, and pain (chemotherapy yes v no: OR, range, 2.01-3.66; 95% CI, 1.01 to 7.77). A vaginal or vulvar cancer diagnosis was associated with greater odds of reporting pain in the univariable but not the multivariable analysis (results not shown; vaginal or vulvar v uterine cancer: unadjusted OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 1.08 to 7.90). Having cervical cancer was associated with increased odds of reporting fears in the univariable but not the multivariable model (results not shown; cervical v uterine cancer: unadjusted OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.04 to 4.79). In addition, having cervical cancer was associated with decreased odds of reporting pain (cervical v uterine cancer: OR, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.06 to 0.62), and having a partner was associated with greater odds of reporting nervousness (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.44)

TABLE 3.

Factors Associated With DT Problems That Are Common and Associated With High DT and Low FACT-G QOL Scores, GOLD Study 2017-2019

DISCUSSION

An abundance of studies support using the continuous DT score to screen for distress in patients with cancer. However, the clinical utility of the DT problem list has been understudied. Our data indicate that some problems that were frequently endorsed were not associated with substantially worse distress or QOL when comparing women with and without these problems. Conversely, some of the less common problems were associated with large differences in distress and QOL scores.

Given the large number of concerns that patients with cancer face, particularly those with gynecologic cancers, health care providers often cannot address all problems indicated on the DT. Although listing all patient concerns may be justified, it is necessary to meaningfully prioritize patients’ most urgent issues during a clinical visit. Rare problems may be at greater risk of being overlooked, which could be detrimental if they are deeply distressing to patients, such as problems related to parenting with cancer,29-33 fertility,34-36 and work37,38 or potential housing, financial, insurance, and transportation issues, which may be more prevalent in lower income populations.39,40 In addition, the problem list may not be complete. For example, a potential problem that has been identified in previous work but is not on the DT problem list is loneliness.41,42 Finances and insurance are aggregated as one item on the problem list, although they may be distinct problems with distinct approaches to mitigate them. Spirituality may be intended as an umbrella term for both religious and existential concerns, but among nonreligious patients who may object to the term spirituality, existential concerns may go unnoticed in the screening process.43,44 In addition, a problem may be highly distressing, but the patient may or may not be looking for additional support.

One simple way to address these limitations could be to start the DT problem list with open-ended questions, such as the following: “In your own words, what has been most distressing to you, including problems that are not directly related to your cancer?” and “Which of these concerns would you like to talk about with your care team?” This could then be complemented by the DT problem list to help patients identify any additional problems that did not immediately come to mind.

Our risk factor analyses for selected problems support prior research and raise additional research questions. First, the association of older age with fewer problems is consistent with previous studies that reported worse psychosocial outcomes among younger populations with cancer.29,30,34,45 Second, the association of lower incomes with fears, sadness, fatigue, and pain requires further research. Cancer-related financial toxicity may exacerbate finance- and cancer-related stress and reduce QOL.46-51 The association between lower incomes and pain also points to the need for future research on potential income disparities in cancer pain management and to possible interaction effects of stressors that might exacerbate the experience of pain. Third, albeit limited by small sample size, patients with vaginal and vulvar cancer emerged as a potentially vulnerable group. Understudied, the rarity of these cancers and social stigma related to having a malignancy in the vulva or vagina may isolate these patients.41,52 Exploratory findings from the limited studies on individuals diagnosed with vaginal and vulvar cancer suggest restrictions in activities of daily living,53 feelings of stigma and embarrassment,52,54,55 relationship disruptions, and frequent sexual dysfunction in this patient group.52,56-58

On the basis of our findings, future work should examine the use of the problem list in clinical settings and whether the processes envisioned in clinical guidelines (identifying and discussing key problems with subsequent appropriate referrals) are being practiced and truly maximize patient QOL. Previous studies have shown that an elevated distress score does not always lead to subsequent referrals.20,59 Clinical studies that reported using the problem list have demonstrated that it is possible to integrate the problem list into clinical services in an effective way, emphasizing that the successfulness of that endeavor relies on carefully designed procedures, including staff education, meaningful integration of social and clerical services into clinical services, and thoughtful timing when the tool is applied to patients.60-62

Given sample size restrictions, we could not run in-depth analyses of rare problems associated with large differences in distress or QOL. Similarly, there were only 17 participants with vaginal or vulvar cancers in our study population; however, our findings suggest that these patients may face disproportionate sources of distress. Further, these data were collected from female individuals diagnosed and treated for gynecologic cancers at a single academic institution in Minnesota and, therefore, are likely not generalizable, particularly among nonwhite survivors of cancer, men, or patients with different cancers. Finally, our cross-sectional analysis did not allow us to establish causality in estimated associations.

The continuous distress score of the DT effectively identified survivors of gynecologic cancer experiencing cancer-related distress. However, our findings indicate that the DT problem list does not easily identify concerns most associated with high distress and low QOL. To achieve patient-centered care while facing time restrictions in the clinic, it is relevant to identify what concerns matter most to patients. We believe that simple enhancements to the DT, such as adding free text questions before the current problem list and explicitly asking patients to identify what has been most distressing to them and what problems they hope to receive support for, could help formalize a clinical process to identify major sources of distress among patients with cancer. Our study also indicates that there is a need to characterize vulnerabilities of different patient subgroups, for example, by cancer type, socioeconomic status, or life stage. Knowing which sources of distress are likely in different patient groups may help clinicians address urgent patient concerns more efficiently.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

R.I.V. is the Masonic Cancer Center Women’s Health Scholar, which is sponsored by the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center (National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health Grant No. P30 CA77598 [Primary Investigator D. Yee]), a comprehensive cancer center designated by the National Cancer Institute, and administrated by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health. Support for the use of REDCap was provided by Grant No. UL1TR002494 from the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

APPENDIX

Fig A1.

Distress and quality-of-life score distributions for different subgroups (N = 355) from the Gynecologic Oncology–Life After Diagnosis (GOLD) study (2017-2019).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Patricia I. Jewett, Sue Petzel, Heewon Lee, Jeffrey Kendall, Dorothy Hatsukami, Susan A. Everson-Rose, Anne H. Blaes, Rachel I. Vogel

Financial support: Rachel I. Vogel

Provision of study materials or patients: Deanna Teoh, Rachel I. Vogel

Collection and assembly of data: Patricia I. Jewett, Audrey Messelt, Anne H. Blaes, Rachel I. Vogel

Data analysis and interpretation: Patricia I. Jewett, Deanna Teoh, Sue Petzel, Dorothy Hatsukami, Susan A. Everson-Rose, Rachel I. Vogel

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Cancer-Related Distress: Revisiting the Utility of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer Problem List in Women With Gynecologic Cancers

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Deanna Teoh

Research Funding: KCI/Acelity, Tesaro

Jeffrey Kendall

Honoraria: Lilly Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Lilly Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Lilly Oncology, Pfizer

Rachel I. Vogel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Voluntis

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: USP14 as a biomarker for endometrial cancer (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mehnert A, Hartung TJ, Friedrich M, et al. One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: Prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncology. 2018;27:75–82. doi: 10.1002/pon.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland JC. American Cancer Society Award lecture: Psychological care of patients: Psycho-oncology’s contribution. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(suppl 23):253s–265s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiegel D. Mind matters in cancer survival. Psychooncology. 2012;21:588–593. doi: 10.1002/pon.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kissane D. Beyond the psychotherapy and survival debate: The challenge of social disparity, depression and treatment adherence in psychosocial cancer care. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1–5. doi: 10.1002/pon.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page AE, Adler NE. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care Manual (2019 Draft Revised Standards). Standard 5.3 - Psychosocial Distress Screening. https://www.facs.org/∼/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/draft_coc_revised_standards_may2019.ashx

- 8.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103:1494–1502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell AJ. Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: A review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:487–494. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland JC, Bultz BD, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0048. Riba MB, Donovan KA, Andersen B, et al: Distress Management, Version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17:1229-1249, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snowden A, White CA, Christie Z, et al. The clinical utility of the distress thermometer: A review. Br J Nurs. 2011;20:220–227. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.4.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.VanHoose L, Black LL, Doty K, et al. An analysis of the distress thermometer problem list and distress in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1225–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clover KA, Oldmeadow C, Nelson L, et al. Which items on the distress thermometer problem list are the most distressing? Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4549–4557. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarland DC, Shaffer KM, Tiersten A, et al. Physical symptom burden and its association with distress, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 2018;59:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, et al. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: Prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergerot CD, Mitchell H-R, Ashing KT, et al. A prospective study of changes in anxiety, depression, and problems in living during chemotherapy treatments: Effects of age and gender. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1897–1904. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3596-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarland DC, Shaffer KM, Tiersten A, et al. Prevalence of physical problems detected by the distress thermometer and problem list in patients with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27:1394–1403. doi: 10.1002/pon.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergerot CD, Bergerot PG, Philip EJ, et al. Assessment of distress and quality of life in rare cancers. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2740–2746. doi: 10.1002/pon.4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thewes B, Butow P, Stuart-Harris R, et al. Does routine psychological screening of newly diagnosed rural cancer patients lead to better patient outcomes? Results of a pilot study. Aust J Rural Health. 2009;17:298–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2009.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Cancer Society: Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures, 2016-2017. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/survivor-facts-figures.html.

- 22.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Distress Management. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx.

- 25.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overcash J, Extermann M, Parr J, et al. Validity and reliability of the FACT-G scale for use in the older person with cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:591–596. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rural Health Research Center, Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington. Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Codes. RUCA Data. Code Definitions: Version 2.0. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-codes.php

- 29.Muriel AC, Moore CW, Baer L, et al. Measuring psychosocial distress and parenting concerns among adults with cancer: The Parenting Concerns Questionnaire. Cancer. 2012;118:5671–5678. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park EM, Check DK, Song MK, et al. Parenting while living with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2017;31:231–238. doi: 10.1177/0269216316661686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park EM, Deal AM, Yopp JM, et al. Understanding health-related quality of life in adult women with metastatic cancer who have dependent children. Cancer. 2018;124:2629–2636. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rauch PK, Muriel AC. The importance of parenting concerns among patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helseth S, Ulfsaet N. Parenting experiences during cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:386–405. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shnorhavorian M, Harlan LC, Smith AW, et al. Fertility preservation knowledge, counseling, and actions among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: A population-based study. Cancer. 2015;121:3499–3506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thewes B, Meiser B, Taylor A, et al. Fertility- and menopause-related information needs of younger women with a diagnosis of early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5155–5165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:109–130. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang JW, Friedman DL, Whitton JA, et al. Employment status among adult survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:104–110. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38:976–993. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Cancer Institute: Risk factors related to financial toxicity (financial distress) in cancer. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-pdq#_247.

- 41.Adams RN, Mosher CE, Winger JG, et al. Cancer-related loneliness mediates the relationships between social constraints and symptoms among cancer patients. J Behav Med. 2018;41:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9892-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosedale M. Survivor loneliness of women following breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:175–183. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salander P. Who needs the concept of “spirituality”? Psychooncology . 2006;15:647–649. doi: 10.1002/pon.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanyi RA. Towards clarification of the meaning of spirituality. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:500–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arès I, Lebel S, Bielajew C. The impact of motherhood on perceived stress, illness intrusiveness and fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors over time. Psychol Health. 2014;29:651–670. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.881998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: It’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108:djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332–338. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, et al. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: Effects on quality of life. Cancer. 2008;112:616–625. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122:283–289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Markman M, Luce R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: An internet-based survey. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:69–73. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jefferies H, Clifford C. Aloneness: The lived experience of women with cancer of the vulva. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:738–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senn B, Eicher M, Mueller MD, et al. A patient-reported outcome measure to identify occurrence and distress of post-surgery symptoms of WOMen with vulvAr Neoplasia (WOMAN-PRO): A cross sectional study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rüegsegger AB, Senn B, Spirig R. Allein mit dem Tabu”: Wie frauen mit vulvären neoplasien die unterstützung durch ihr soziales umfeld beschreiben—Eine qualitative studie. Pflege. 2018;31:191–202. doi: 10.1024/1012-5302/a000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Likes WM, Russell C, Tillmanns T. Women’s experiences with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:640–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Green MS, Naumann RW, Elliot M, et al. Sexual dysfunction following vulvectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77:73–77. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aerts L, Enzlin P, Vergote I, et al. Sexual, psychological, and relational functioning in women after surgical treatment for vulvar malignancy: A literature review. J Sex Med. 2012;9:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janda M, Obermair A, Cella D, et al. Vulvar cancer patients’ quality of life: A qualitative assessment. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:875–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitchell AJ. Screening for cancer-related distress: When is implementation successful and when is it unsuccessful? Acta Oncol. 2013;52:216–224. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.745949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frost GW, Zevon MA, Gruber M, et al. Use of distress thermometers in an outpatient oncology setting. Health Soc Work. 2011;36:293–297. doi: 10.1093/hsw/36.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knobf MT, Major-Campos M, Chagpar A, et al. Promoting quality breast cancer care: Psychosocial distress screening. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12:75–80. doi: 10.1017/S147895151300059X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McCulloch P: Development of a wellbeing clinic for patients after colorectal cancer. Cancer Nurs Pract 13:25-30, 2014. [Google Scholar]