Abstract

PURPOSE:

To determine if a quality improvement (QI) initiative could enhance multidisciplinary management of acute malignant extradural spinal cord compression (ESCC) at our institution.

METHODS:

The medical records of all 40 patients who received palliative radiotherapy for malignant ESCC from 2015 to 2017 were reviewed to determine the time course of key National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline–supported workup and management steps. On the basis of the findings, a multidisciplinary group of physician stakeholders developed a clinical pathway to facilitate expedited care. The efficacy of this clinical pathway and the educational content provided to all relevant departments were then evaluated by comparing outcomes with data from a similarly reviewed follow-up cohort of 25 patients from 2018 to 2019.

RESULTS:

Patients treated for malignant ESCC after our QI intervention were more likely to undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the entire spine (64% v 44%; P = .013) and have a radiation oncology (RO) consultation before surgery (100% v 27%; P = .002). Median time from MRI to RO consultation decreased from 3 to 1 days (P = .03). On subgroup analysis, initial trends toward delays in RO consultation for patients planning for surgery (median, 3 days) or for lack of prior cancer diagnosis (median, 4 days) were reduced to delays of 0 and 1 day, respectively, after the QI intervention. No significant differences were observed in time to surgical consultation or surgery itself.

CONCLUSION:

This QI study was able to stimulate better use of diagnostic imaging and earlier involvement of RO in multidisciplinary decision making, suggesting an effective approach to improving multidisciplinary care in other scenarios as well.

INTRODUCTION

Multidisciplinary care is an essential component of oncology1 and is particularly important in the setting of oncologic emergencies, where ineffective communication or delays in referrals have the potential to greatly affect patient outcomes.2 Acute malignant extradural spinal cord compression (ESCC) is an oncologic emergency that can be particularly challenging to manage effectively, given that it is commonly diagnosed in an inpatient setting, at times by nononcologists in patients without a previous cancer diagnosis, and can be managed in divergent ways depending on a variety of factors.3 For instance, prior studies have reported median delays from onset of symptoms of ESCC to diagnosis and treatment of 2 and 14 days, respectively, with deterioration in neurologic function as a consequence.4,5

Despite consensus guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the United Kingdom, Canada, and other surgical and radiation oncology (RO) specialty societies,2,3,6-9 members of our cancer center anecdotally recognized recurring problems with adherence to NCCN recommendations. The aim of this quality improvement (QI) project was to study the efficacy of an educational campaign geared toward expediting and improving multidisciplinary care for ESCC at our institution.

METHODS

The scope of this study included (1) a retrospective medical record review to establish the baseline time course of key events in the workup and management of ESCC at our institution, (2) development of educational content and an internal clinical pathway that was in line with NCCN guidelines and addressed solutions to particular deficiencies or delays in care exposed by the medical record review, (3) delivery of that educational content to relevant physicians, and (4) retrospective reassessment over the following year to detect improvements in the baseline metrics.

After obtaining institutional review board exemption, the retrospective medical record review was performed, which included all patients diagnosed with malignant ESCC and treated with radiotherapy to the spine at our institution from 2015 to 2017. Patients were excluded if referred for radiotherapy from an outside hospital or for intramedullary metastasis, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, or primary CNS tumor because their management would differ.2 The key NCCN-supported data measurements evaluated included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the entire spine (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar), early steroid use (in most cases), upfront multidisciplinary consultations for both surgery and RO, and initiation of treatment within 24 hours of diagnosis, because there is a lower likelihood of reversing neurologic symptoms beyond this point.10,11

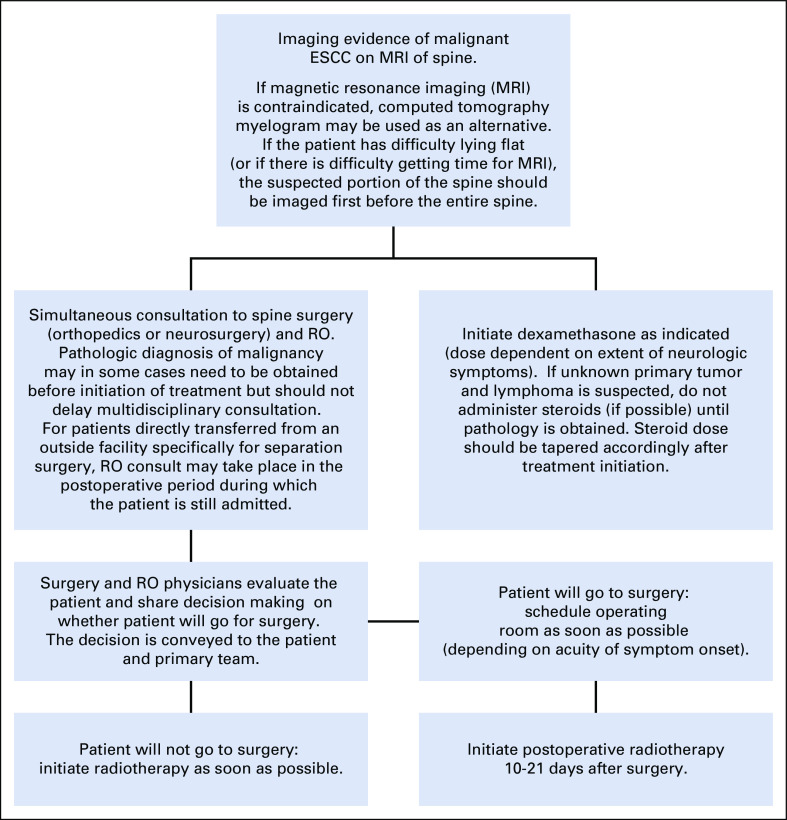

A multidisciplinary group of physician stakeholders from RO, medical oncology, neurosurgery, and orthopedic surgery reviewed the findings and developed an internal clinical pathway supported by NCCN recommendations. This proposed clinical pathway, along with our data and practical information about how to consult relevant physicians and expedite MRI and biopsy studies and their interpretations, was approved by the hospital cancer committee and presented in June to July 2018 to faculty and residents/fellows from medical oncology, internal medicine, emergency medicine, RO, neurosurgery, and orthopedic surgery. Additional feedback was collected from participants, and the finalized clinical pathway (Appendix Fig A1, online only) was e-mailed to each department and published online for all providers at our institution to easily access at any time.

Follow-up evaluation for an improvement in patient care was carried out in a similar cohort of patients with ESCC treated from August 2018 to July 2019. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize our findings, and χ2 and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for univariable comparisons between the initial and follow-up cohorts of patients. Mortality rates are presented as an indicator of effective surgical selection, given that consensus guidelines only support surgical intervention when life expectancy is at least 90 days.2,12,13 Because a planned surgical intervention or a lack of pathologic confirmation of malignancy has been shown to delay RO consultation in the palliative setting,14 these factors were assessed in a subgroup analysis for their impact on time to RO consultation.

RESULTS

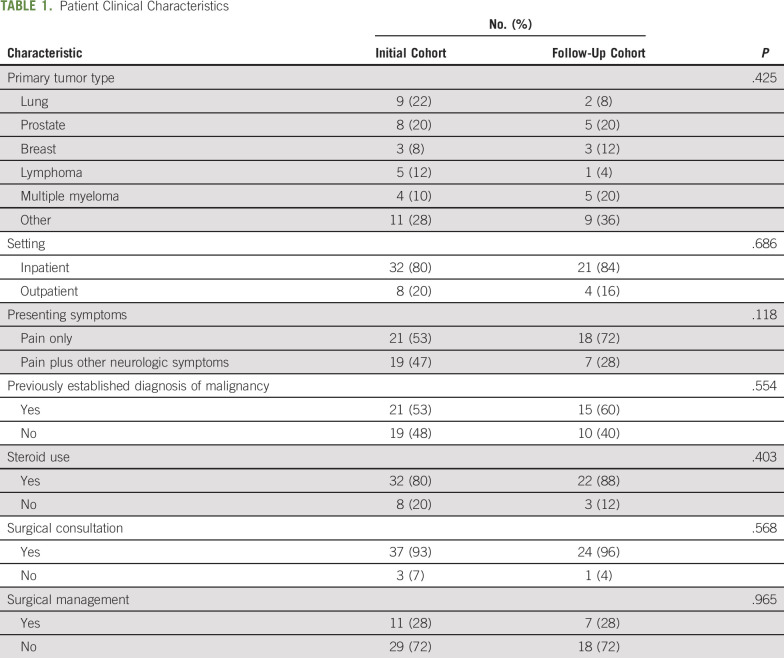

Demographic features of the patients included in both the initial cohort (before the QI project) and follow-up cohort (after the QI project) are listed in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups. Among the patients who underwent surgical management, the 30- and 90-day mortality rates in the initial cohort were 0% and 36%, respectively, as compared with 0% and 29% in the follow-up cohort. The 30- and 90-day mortality rates among patients who receiving radiotherapy alone were 13% and 29%, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Patient Clinical Characteristics

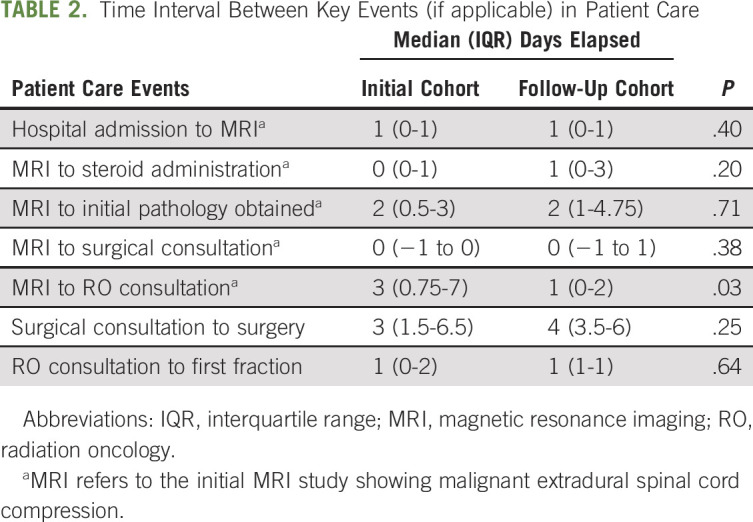

Median elapsed time intervals between key events in the workup and management of patients with malignant ESCC are listed in Table 2. A statistically significant improvement in median time from the initial MRI showing ESCC to RO consultation was observed. The follow-up cohort was significantly more likely to undergo an MRI of the whole spine (44% v 64%; P = .013) and have an RO consultation before any surgical intervention (27% v 100%; P = .002). There was no significant difference in time to surgical consultation or surgery itself.

TABLE 2.

Time Interval Between Key Events (if applicable) in Patient Care

In the initial cohort of patients, median time from MRI to RO consultation was longer among the subgroup of patients who underwent surgical decompression before radiotherapy, as compared with those who received radiotherapy alone without surgery (5 days; interquartile range [IQR], 2.5-12 days v 2 days; IQR, 0-7 days; P = .129). This difference was no longer present in the follow-up cohort (median, 1 day; IQR, 0-2 days for both groups; P = .911). Similarly, in the initial cohort of patients, median time from MRI to RO consultation was longer among the subgroup of patients with no prior pathologic confirmation of malignancy compared with those with previously biopsy-confirmed malignancy (6 days; IQR, 1-9 days v 2 days; IQR, 0-7 days; P = .208). This difference was decreased in the follow-up cohort (median, 2 days; IQR, 0.25-5.75 days v 1 day; IQR, 0-2 days; P = .766).

DISCUSSION

A strategic priority of most health care organizations, hospitals, and cancer centers is to provide high-quality, patient-centered care delivered by a cohesive team of physicians. We have shown in this study that a QI initiative was able to stimulate better use of diagnostic imaging and earlier involvement of radiation oncologists in multidisciplinary decision making, which translated into expedited radiotherapy delivery. We attribute these successes largely to our methodic approach: seeking buy-in from the outset from relevant cancer center committees and key physician stakeholders in multiple departments, developing a formal clinical pathway with their input, and discussing that pathway in a nonjudgmental and collaborative way with members of each department.

There are barriers to any multidisciplinary team functioning well,15 especially for more acute oncologic emergencies like malignant ESCC, but related studies have also demonstrated the value of QI initiatives geared toward improving multidisciplinary care in the context of oncology departments,16 cancer case conferences,17 and specific conditions.18 Important aspects of the management of ESCC that remained unchanged by this QI project were patient selection for surgery and time from surgical consultation to surgery, which may have been improved further by incorporating a surgeon into the didactic sessions themselves (all of which were delivered by a radiation oncologist). It is also possible that the time to surgery was limited less by the physicians than by availability of operating room facilities, which would be an important avenue to pursue in the future. Although there is still room for improvement in surgical selection, with approximately one third of patients dying within 90 days of surgery in this study, it should be noted that our mortality rates were comparable to those reported in other studies for this relatively fragile patient population with ESCC.11-13

There are several important limitations of this study. It took place at a single institution and had a relatively small sample size. The timing of certain events was probably also affected by the degree of extradural compression and severity of symptoms at presentation, leading physicians in some cases to perhaps not consider a given patient a true emergency. Our approach of using the time course between specific events as a surrogate for delays in care or functional outcomes is imperfect, but it is a reasonable compromise for a retrospective study when the general consensus from prior prospective studies and consensus guidelines is that patients with malignant ESCC benefit from treatment of their condition as a time-sensitive oncologic emergency regardless of the setting of care or tumor type.2-13 We also cannot determine which particular components of our grouped interventions for educating physicians had the greatest impact. Finally, we cannot be sure that all relevant physicians read or referenced the clinical pathway generated, but we did try to make it available to them in as many ways as possible (in-person education session, e-mail, and online).

In conclusion, we have shown in this study that a QI initiative can improve guideline-adherent multidisciplinary management of malignant ESCC. Although not addressed in this report, sustainability is an important component of the success of this project, and we plan to continue promoting the clinical pathway through automatic inclusion in MRI radiologist reports diagnosing ESCC in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Crystal Street provided administrative support for this project through the West Virginia University Cancer Committee.

APPENDIX

Workup and management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression

Malignant extradural spinal cord compression is an oncologic emergency that requires coordination of multiple different types of physicians for appropriate management.

-

Clinical suspicion of malignant spinal cord compression should prompt magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the entire spine.

If MRI is contraindicated, computed tomography myelogram may be used as an alternative.

If the patient has difficulty lying flat (or if there is difficulty getting time in MRI), then the suspected portion of the spine should be imaged first before the entire spine.

-

If there is imaging evidence of malignant extradural spinal cord compression, there should be a simultaneous immediate consultation by both the spine surgery and radiation oncology teams. Dexamethasone should also be started as clinically indicated.

If unknown primary tumor and lymphoma are suspected, do not administer steroids (if possible) until biopsy is obtained.

The standard dose of dexamethasone for symptomatic patients is a loading dose of 10 mg followed by 6 mg every 6 hours.

Pathologic diagnosis of malignancy may in some cases need to be obtained prior to initiating treatment, but should not delay multidisciplinary consultation.

-

Surgery and radiation oncology physicians evaluate the patient and engage in shared decision-making on whether the patient will go for surgery. The decision is conveyed to the patient and primary team.

If the patient will go for surgery, schedule operating room as soon as possible (depending on acuity of symptom onset). Post-operative radiation therapy is initiated 10-21 days after surgery.

If patient will not go for surgery, initiate radiation therapy as soon as possible.

Taper the dose of steroids accordingly after initiation of treatment.

Fig A1.

Workup and management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression (ESCC).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Malcolm D. Mattes

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Quality Improvement Initiative to Enhance Multidisciplinary Management of Malignant Extradural Spinal Cord Compression

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elnahal SM, Pronovost PJ, Herman JM. More than the sum of its parts: How multidisciplinary cancer care can benefit patients, providers, and health systems. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:738–742. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Central Nervous System Cancers—Version 3.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Laufer I, Rubin DG, Lis E, et al. The NOMS framework: Approach to the treatment of spinal metastatic tumors. Oncologist. 2013;18:744–751. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husband DJ. Malignant spinal cord compression: Prospective study of delays in referral and treatment. BMJ. 1998;317:18–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levack P, Graham J, Collie D, et al. Don’t wait for a sensory level--Listen to the symptoms: A prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2002;14:472–480. doi: 10.1053/clon.2002.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Collaborating Centre for Cancer: Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression: Diagnosis and Management of Patients at Risk of or With Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression—National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Clinical Guidelines, No. 75. Cardiff, United Kingdom, National Collaborating Centre for Cancer, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loblaw DA, Mitera G, Ford M, et al. A 2011 updated systematic review and clinical practice guideline for the management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lutz S, Balboni T, Jones J, et al. Palliative radiation therapy for bone metastases: Update of an ASTRO Evidence-Based Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutz S, Berk L, Chang E, et al. Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: An ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North RB, LaRocca VR, Schwartz J, et al. Surgical management of spinal metastases: Analysis of prognostic factors during a 10-year experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:564–573. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:643–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66954-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klimo P, Jr, Thompson CJ, Kestle JR, et al. A meta-analysis of surgery versus conventional radiotherapy for the treatment of metastatic spinal epidural disease. Neuro-oncol. 2005;7:64–76. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witham TF, Khavkin YA, Gallia GL, et al. Surgery insight: Current management of epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic spine disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:87–94, quiz 116. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker SM, Wei RL, Jones JA, et al. A targeted needs assessment to improve referral patterns for palliative radiation therapy. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8:516–522. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.08.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, et al. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: Are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:935–943. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catherman KA, Grey C, Mattes MD. Use of multisource feedback to improve interdisciplinary care among oncologists. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:1578–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamb BW, Wong HW, Vincent C, et al. Teamwork and team performance in multidisciplinary cancer teams: Development and evaluation of an observational assessment tool. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:849–856. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halyabar O, Chang MH, Schoettler ML, et al. Calm in the midst of cytokine storm: a collaborative approach to the diagnosis and treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and macrophage activation syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2019;17:7. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]