Abstract

Disaster preparedness plans reduce future damages, but may lack testing to assess their effectiveness in operation. This study used the state-designed Local Government Unit Disaster Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors in assessing the readiness to natural hazards of 92 profiled municipalities in central Philippines inhabited by 2.4 million people. Anchored on the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015, it assessed their preparedness in 4 criteria—systems and structures, policies and plans, building competencies, and equipment and supplies. Data were analyzed using statistical package for social sciences, frequency count, percentage, and weighted mean. The local governments were found highly vulnerable to tropical cyclone and flood while vulnerable to earthquake, drought, and landslide. They were partially prepared regardless of profile, but the coastal, middle-earning, most populated, having the least number of villages, and middle-sized had higher levels of preparedness. Those highly vulnerable to earthquake and forest fire were prepared, yet only partially prepared to flood, storm surge, drought, tropical cyclone, tornado, tsunami and landslide. The diverse attitude of stakeholders, insufficient manpower, and poor database management were the major problems encountered in executing countermeasures. Appointing full-time disaster managers, developing a disaster information management system, massive information drive, organizing village-based volunteers, integrating disaster management into formal education, and mandatory trainings for officials, preparing for a possible major volcanic eruption and crafting a comprehensive plan against emerging emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to a 360° preparedness.

Keywords: Countermeasures, Disaster preparedness, Local government, Municipalities, Vulnerability

Introduction

The increasing frequency of disasters has challenged the preparedness of highly vulnerable countries (Yadav and Barve 2019) in Asia Pacific to take actions toward mitigating risks (Merone and Tait 2018). Since communities are first responders to any disaster (Walia 2008), strengthening their capacity to cope with calamities is crucial.

The magnitude 7.2 earthquake that struck the provinces of Bohol and Cebu on October 15, 2013 has challenged the preparedness of the Philippines against natural hazards. After less than a month, tropical cyclone Haiyan (locally named Yolanda) devastated central Philippines.

In light of the more recent disasters in the Philippines, disaster research has become even more urgent (Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters 2014 as cited by Dalisay and De Guzman 2016). An investment in preparedness substantially reduces future disaster damage (Healy and Malhotra 2009). It consists steps to minimize harm and aid in recovery should a disaster occurs (e.g., Dooley et al. 1992 as cited by Scannel et al. 2016).

However, disaster plans may lack testing, such as practice drills, to assess their effectiveness before hazards hit (Muir and Shenton 2002 as cited by Tansey 2015). The Philippines poorly performs in disaster management particularly on financial utilization, information management, leadership, monitoring, collaboration, and coordination with various stakeholders (Commission on Audit [COA] Report 2014). Its rehabilitation and recovery effort in the past has been the weakest (Office of Civil Defense [OCD] 2020).

Panay is a 1,169,247-hectare island (Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), 2018) with a population of around 2.4 million (Philippine Statistics Authority 2016). Iloilo City, the regional center of business and government is the 5th most populated highly urbanized city outside the capital Manila. In 2017, it posted a 6.1% economic growth (National Economic and Development Authority 2017).

This study assessed and compared the level of preparedness of 92 profiled municipalities in Panay Island, central Philippines. The natural hazards that have been threatening these areas were identified along with their implemented countermeasure programs. The preparedness of local governments, when grouped according to province, profile, and vulnerability to natural hazards was evaluated and assimilated. The challenges that local officials faced in executing disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) programs were ranked.

Framework

DRRM can be anchored to the open systems theory of Katz and Kahn (1971) and contingency theory of Bertalanffy (1972). An open system is influenced by and interacts with its environment. The organization takes inputs from its environment and processes these into outputs that are, then, distributed in the environment. The contingency theory claims that there is no best way to organize a corporation, to lead a company, or to make decisions. Instead, the optimal course of action is dependent on internal and external situations. The major variables considered in choosing appropriate management style are organizational size, routineness of task technology, environmental uncertainty and individual differences (Robbins and Coutler 2018).

There is a need to adopt and implement integrated policies and plans toward resilience to disasters, and develop and implement, in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, a holistic disaster risk management at all levels (Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs] 2016). World leaders adopted this framework, which proposes policies and practices for DRRM be based on an understanding of disaster risk in all its dimensions of vulnerability, capacity, exposure of persons and assets, hazard characteristics and the environment. Such knowledge can be leveraged for the purpose of pre-disaster risk assessment, for prevention and mitigation and for the development and implementation of appropriate preparedness and effective response to disasters. Moreover, strengthening disaster risk governance in all levels for prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery, and rehabilitation is therefore necessary and fosters collaboration and partnership across mechanisms and institutions for the implementation of instruments relevant to DRR and sustainable development (Sendai Framework for DRR 2015–2030 2015).

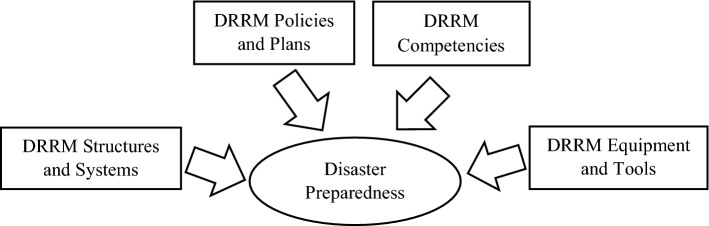

A local law, Republic Act (RA) 10121 was enacted in 2010 to strengthen the country’s DRRM for safer, adaptive, and disaster-resilient Filipino communities toward sustainable development. It has 4 thematic areas—prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response, and rehabilitation and recovery. The Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) is a national government agency (NGA) mandated to oversee and enhance the capability of local governments. Tasked to achieve the second thematic area, i.e., preparedness, it devised in 2014 the LGU Disaster Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors. Anchored on the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015, it proposes the 4 components of disaster preparedness (Fig. 1). Structures and systems refer to committees which shall spearhead DRRM activities. Policies and plans are existing documents stipulating the DRRM actions like local legislation, action plans and comprehensive land use plan that incorporate DRRM. Building competencies refer to trainings attended by responders and disaster managers. Finally, equipment and tools include heavy equipment, rescue boats, ambulances, and early warning devices.

Fig. 1.

The 4 areas of disaster preparedness according to the LGU disaster preparedness journal: checklist of minimum actions for mayors

Literature review

Catastrophic natural disasters affect a country’s economic growth (Achoka and Maiyo 2008; Cavallo et al. 2013; Loayza et al. 2012) and poverty-reduction efforts (Arnold 2006; Bui et al. 2014; Rodriguez-Oreggia et al. 2013), but this could be headed off when there is good management in executing the planned effective measures (Quarantelli 2002). An investment in people and equipment complements efficient planning and execution.

The Philippines ranks second highest in terms of risks associated with natural disasters (UNU-EHS and ADW-2014 as cited by Andriesse 2018). A steady population increase, combined with a geography consisting of islands and poor infrastructure, makes it vulnerable to humanitarian crises (Lum and Margesson 2014). Situated in the north-west Pacific Ocean, it is the most tropical cyclone-affected country in the world with an average of 20 annually, of which 6 are classified destructive. It is also found just below the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone with northeast and southwest monsoons posing threats to its whole territory with flood and storm surge. These result to casualties and billions of pesos in damages to structures and houses (Peñalba et al. 2012; Lee and Vink 2015; Cas 2016; Enteria 2016). Its location along the Pacific Ocean’s Ring of Fire exposes this country to earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions (Pe Symaco 2013).

Haiyan (Yolanda) caused 6–7 m high storm surges in 2013. It was the strongest tropical cyclone and deadliest disaster in Philippine modern history sparking catastrophic damage to coastal communities (Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters 2014 as cited by Dalisay and De Guzman 2016; Nakamura et al. 2016). The country’s National DRRM Council recorded around 6300 deaths, 1061 missing and 28,689 injuries. About 12,000 shelters were destroyed while 47,000 were nearly damaged (Commission on Audit [COA] Report 2014 as cited by Dalisay and De Guzman 2016).

The over 14 million seriously-affected Filipinos were inhabitants of the Visayas zone (Hall and Ashcroft 2014; O’Connell et al. 2017) in central Philippines particularly Eastern, Central and Western Visayas regions. The scourged provinces in Western Visayas were Capiz, northern part of Iloilo, Aklan, and northern portion of Antique all located in Panay Island.

The country is divided into administrative regions that are composed of local governments—province, city, municipality or town, and barangay or village. Barangays form cities and municipalities. A municipality has a lower population, smaller land area, lesser urbanized villages, and lower total revenue collection than a city. A typical province consists of several municipalities and a city. Some may have one or more cities, but others only have municipalities. Except the Bangsamoro Administrative Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in Southern Philippines, regions do not have elected local officials. The local governments, on the other hand, elect leaders performing executive and legislative functions. The governor heads a province while the mayor governs a city or municipality. The punong barangay captains a village, the smallest unit. Figure 2 shows the location of Panay Island. The province of Aklan is in the northwest, Antique in the west, Capiz in the northeast, and Iloilo in the east (Fig. 3). Table 1 lists its 92 municipalities in the mainland.

Fig. 2.

a The Philippines in Asia; b Panay Island in the Philippines; and c Panay Island

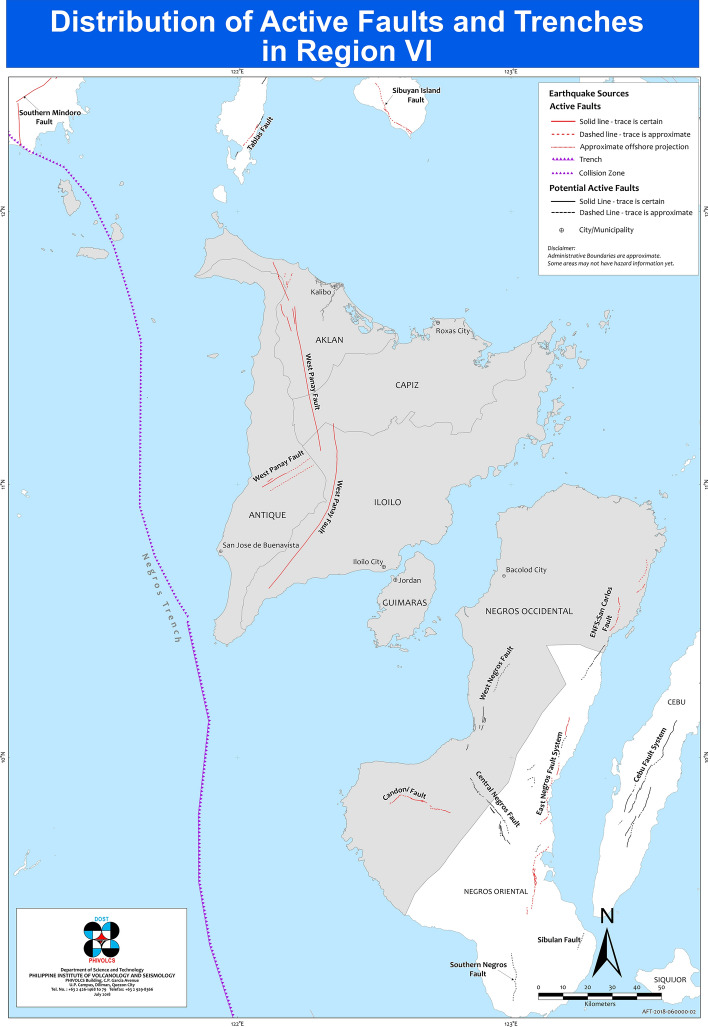

Fig. 3.

The location of West Panay Fault, Collision Zone and Negros Trench that can generate earthquakes in Panay and neighboring islands

Table 1.

The 92 municipalities comprising the four provinces in Panay Island, central Philippines

| Provinces | Municipalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aklan | Altavas | Ibajay | Malay | Numancia |

| Balete | Kalibo | Makato | Tangalan | |

| Batan | Lezo | Malinao | ||

| Banga | Libacao | Nabas | ||

| Buruanga | Madalag | New Washington | ||

| Antique | Anini-y | Hamtic | San Jose de Buenavista | Tobias Fornier |

| Barbaza | Laua-an | San Remegio | Valderrama | |

| Belison | Libertad | Sebaste | ||

| Bugasong | Pandan | Sibalom | ||

| Culasi | Patnongon | Tibiao | ||

| Capiz | Cuartero | Ivisan | Panay | President Roxas |

| Dao | Jamindan | Panit-an | Sapi-an | |

| Dumalag | Maayon | Pilar | Sigma | |

| Dumarao | Mambusao | Pontevedra | Tapaz | |

| Iloilo | Ajuy | Calinog | Leganes | Sara |

| Alimodian | Carles | Lemery | San Enrique | |

| Anilao | Concepcion | Leon | San Joaquin | |

| Badiangan | Dingle | Maasin | San Miguel | |

| Balasan | Dueñas | Miagao | San Rafael | |

| Banate | Dumangas | Mina | Santa Barbara | |

| Barotac Nuevo | Estancia | New Lucena | Tubungan | |

| Barotac Viejo | Guimbal | Oton | Tigbauan | |

| Batad | Igbaras | Pavia | Zarraga | |

| Bingawan | Janiuay | Pototan | ||

RA 10121, the Philippine DRRM Act of 2010, totally reformed governance. It calls each local government to allot 5% of the budget as calamity fund. The 70% are for preparedness measures while the remaining 30% are reserved for response and recovery. La Viña and Tan (2015) revealed that these practices were prohibited prior to 2010. In the past, only 30% could be spent for preparation. When no disaster came, the 70% could be realigned to other projects or fund bonuses for employees.

DRRM Councils handle emergencies from the national down to local levels. The National DRRM Council is a collection of mandated NGAs and representatives from the private sector and civil society organizations. The directors of regional offices and field stations of government agencies at the regional-level comprise the Regional DRRM Council. The Provincial, City and Municipal DRRM Councils consist of local government officials and heads of concerned NGAs at the provincial, city and municipal levels, respectively. The barangay or village officials make up the Barangay DRRM Council (Philippine DRRM Act 2010).

The Local Government Academy of DILG formulated the LGU Disaster Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors with the participation of LGUs, NGAs, civil society organizations, academe, and the private sector. It is a tool for policy decisions, strategic action formulation and assessing the local government’s level of preparedness against natural hazards.

The OCD’s annual Gawad Kalasag Award recognizes best-performing LGUs on DRRM initiatives at the regional and national levels. The DILG also gives the Seal of Good Local Governance (SGLG) distinction to local governments having best performance in disaster preparedness, financial management, among other things.

The Commission on Audit (COA), an independent office that reviews financial transactions in all public offices, assessed in 2014 the country’s DRRM practices. It found that government’s response and recovery efforts in Tropical cyclone Haiyan (Yolanda)-ravaged areas clearly showed that the implementation of R.A. 10121 still left a lot to be desired. The National DRRM Council’s key players and stakeholders had difficulty coordinating, collaborating and making timely decisions signifying unreadiness and ineptitude to respond to host emergencies and crippling crises.

Haiyan exposed the low level of disaster preparedness and response capabilities of many local governments. Although the government has operational DRRM programs, made ample preparations and braced themselves for the worst, they were simply crushed and overwhelmed by the scope and enormity of the destruction. Despite the OCD’s recognition and incentives to local governments’ commendable performance, many of them have yet to integrate DRRM policies into their own development plans (COA 2014).

The report clearly assessed the state of disaster preparedness in the country. This study focused on the disaster preparedness of 92 municipalities in Panay Island, central Philippines. Municipalities make up most of local governments in the country. They have lesser funds than cities, but are first responders to calamities. Fund shortage disabled most of their villages to have functional DRRM offices. The crafted inputs may strengthen their weaknesses and will aid DILG achieve the ideal level of preparedness at the community level.

Methodology

This study employed a descriptive survey research design in assessing the disaster preparedness of 92 local governments that comprise the provinces of Aklan, Antique, Capiz and Iloilo in Panay Island, central Philippines. The state-designed assessment tool, LGU Disaster Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors was used to determine the minimum actions that the central government requires from local governments. It consists of a checklist grouped into 4 parts—profile of local governments; potential natural hazards in which they have been vulnerable; countermeasures that they have undertaken in the areas of systems and structures, policies and plans, building competencies, and DRRM equipment and supplies; and the problems encountered in enforcing countermeasures.

Copies of LGUs’ DRRM plans and programs were requested from the governors of 4 provinces, mayors and managers of DRRM offices in 92 municipalities; regional director and four provincial directors of the DILG in Western Visayas region and in 4 provinces, respectively; and from the regional director of OCD. These documents enabled the researchers to compare the central government-prepared framework with the local governments’ DRRM plans and practices.

This study also identified a match or variation between the state guidelines and community DRRM practices, and the source of variations in the levels of preparedness in 92 municipalities. Table 2 shows the profile of local governments. It similarly details the categories and scoring of all variables and the verbal interpretation for annual generated revenues, vulnerability, and preparedness. Descriptive measures such as frequency count, percentages, and weighted means were used for data analysis. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was also utilized.

Table 2.

a Categories and scoring of all variables; b verbal interpretation for annual generated revenues, vulnerability, and preparedness; and c the profile of local governments in Panay Island, central Philippines

| Category | Score | Frequency | Percentage | Verbal interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of local government | Province | (4) | – | |

| City | 3 | 3.3 | ||

| Municipality | 89 | 96.7 | ||

| Population | ≥ 35,001 | 48 | 52.5 | |

| 25,001–35,000 | 26 | 28.2 | ||

| ≤ 25,000 | 18 | 19.6 | ||

| Geographical location | Coastal | 46 | 50.0 | |

| Upland | 29 | 31.5 | ||

| Plain | 17 | 18.5 | ||

| Number of barangays/villages | ≥ 36 | 31 | 33.7 | |

| 26–35 | 19 | 20.6 | ||

| ≤ 25 | 42 | 45.7 | ||

| Land area (ha) | ≥ 30,001 | 4 | 4.3 | |

| 15,001–30,000 | 18 | 19.6 | ||

| ≤ 15,000 | 70 | 76.1 | ||

| Potential disasters | Flood | |||

| Storm surge | ||||

| Earthquake | ||||

| Drought | ||||

| Hailstorm | ||||

| Forest fire | ||||

| Tropical cyclone | ||||

| Tsunami | ||||

| Landslide | ||||

| Tornado | ||||

| Annual generated revenues (M) | ≥ US$1.089 | 13 | 14.1 | 1st class |

| US$0.891–1.069 | 14 | 15.2 | 2nd class | |

| US$0.693–0.871 | 22 | 23.9 | 3rd class | |

| US$0.495–0.673 | 34 | 37.0 | 4th class | |

| US$0.297–0.475 | 9 | 9.8 | 5th class | |

| Vulnerability | (2.34–3.00) | Highly vulnerable | ||

| (1.67–2.33) | Vulnerable | |||

| (1.00–1.66) | Not vulnerable | |||

| Preparedness | (2.34–3.00) | Prepared | ||

| (1.67–2.33) | Partially prepared | |||

| (1.00–1.66) | Not prepared | |||

| Total in each profile | 92 | 100 | ||

Results and discussion

Profile of local governments

Table 2 reveals that 52.2% of LGUs had a population of ≥ 35,001. Exactly 50% of them were coastal, 31.5% were in upland, and 18.5% were in a plain. The 37% could generate annual revenues of US$0.495–0.673 M, 23.9% at US$0.693–0.871 M; 15.2% at US$0.891–1.069 M, and only 14.1% collected ≥ US$1.089 M. It was surprising to find that the 9.8%, equivalent to nine municipalities, had yearly revenues of only US$0.297–0.475 M. In total land area, the 76% had ≤ 15,000 hectares, 19.6% were 15,001–30,000 hectares wide, and the remaining 4.3% possessed a large area of ≥ 30,001 hectares.

Disasters that have threatened local communities

Ten natural hazards have recurred in Panay Island. The disaster managers can still recall the devastation wrought by these disasters.

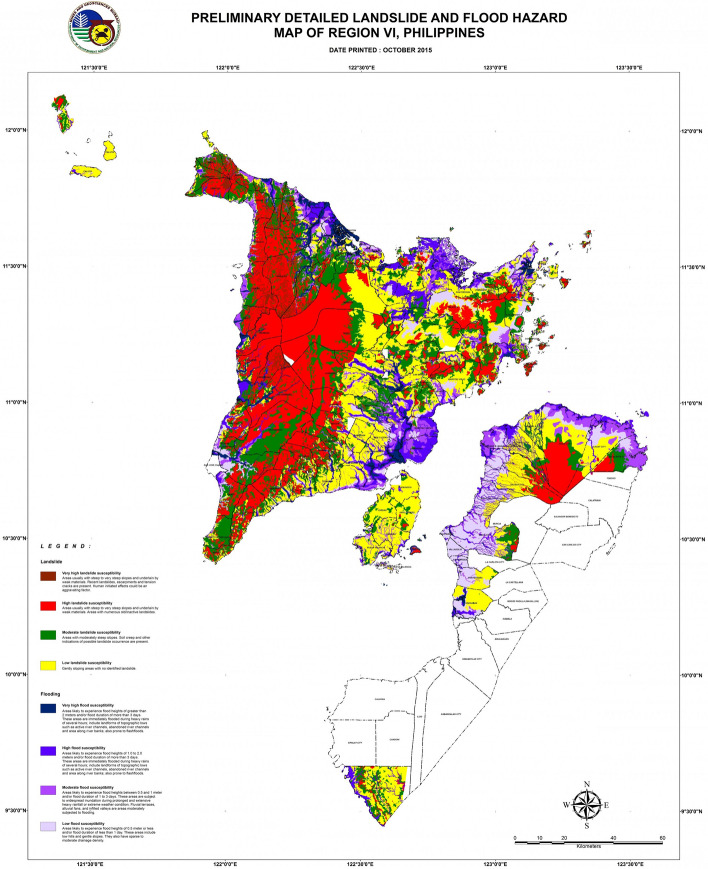

The 65.2% of LGUs were highly vulnerable to flood. As seen in Fig. 4, these were places located along the coast and river banks. These areas overflowed during prolonged heavy rainfall. The western side of Panay was mostly mountainous while the eastern part was in a lowland, making it susceptible to flooding (Fig. 2). Cascading volume of floodwater from upland areas pass the populated plain before reaching the sea.

Fig. 4.

Areas susceptible to flood and landslide. a Landslide: brown-very high, red-high, green-moderate, and yellow-low; b Flood: dark blue-very high, light blue-high, violet-moderate, and gray-low)

Flooding is a condition at which liquid is carried above the point of its entry, i.e., a situation where at least part of the liquid flow is reversed in direction (Vlachos et al. 2001). In residential areas, it is an entry of floodwater to the level of the floor or deeper, of the lowest habitable room. Global warming drives this frequent problem (Reacher et al. 2004).

Around 15.2% of LGUs were highly vulnerable to storm surge while the 30.4% were vulnerable. Danard et al. (2003) define storm surge as an abnormal, sudden rise of sea level associated with a storm event.

Haiyan (Yolanda) brought widespread devastation. Storm surges were primarily responsible for the loss of lives, injuries and damages to properties in spite of early warning. The 4 provinces in Panay Island suffered from heavy damages since these areas were within the tropical cyclone’s 600 km diameter (Lagmay et al. 2015). All municipalities in Panay facing the coastline are prone to storm surge.

In terms of earthquake, 8.7% of local governments were highly vulnerable, 54.3% were vulnerable and 37% were not vulnerable. Overall results classified the entire island as vulnerable to earthquake.

About 81.5% were vulnerable to drought while the 7.6% were highly vulnerable. Van Loon (2013) describes drought as a period of below-normal water availability in precipitation (meteorological drought), soil moisture (soil moisture drought), or groundwater and discharge (hydrological drought), caused by natural variability in climate.

Drought in the Philippines occurs more frequently and its disastrous effects become more serious. It has significant contribution to crop production losses, primarily on rice and corn (Maglinao and Armada 1998). There is drought when the rainy and planting seasons in the month of june are delayed.

Around 3% were susceptible to hailstorm while only 1.1% were highly vulnerable. Formed by severe convective storms, hail stands as a natural risk. It can cause large damage to buildings and crops and sometimes, human life (Chantraket 2015). A hailstorm may cause defoliation before the flowering of rice, which have considerable effect on yield. Flood and tropical cyclone are more damaging than hailstorm, but low production of rice is also a loss of livelihood among rice farmers (Shapiro et al. 1985 as cited by Yaqoob 2017).

The 27.2% of municipalities located in upland areas were prone to forest fire while the 2.2% were highly vulnerable. Zhao et al. (2011) found that forest fire has a periphery of fire region in orange or red color. If the fire burns fully, there are one or more white-yellow color cores. Fire accounts for one-third of the damages done to the Philippines’ critical watershed and forest lands (Codamon-Quitzon 1991). This is also common in Panay during the summer season from March to May.

The 56.5% of areas were vulnerable to tropical cyclone (strong wind), 39.1% of them were highly prone, and only 4.3% were not vulnerable. The overall susceptibility of the island to this hazard was highly vulnerable. A tropical cyclone can sustain a 1 min wind speed of at least 64 knot (Elsner and Liu 2003).

Tropical cyclone (strong wind) strikes the Central and Northern Panay Island every last quarter of each year. The southern part is hit in the second quarter. Tropical cyclones Agnes (Undang) in November 1984, Haiyan (Yolanda) in November 2013, and Phanfone (Ursula) in December 2019 recently devastated Northern Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, and Northern Antique. The OCD (2020) reported that 28 people died, 2 injured and 12 were missing after tropical cyclone Phanfone (Ursula) shattered Regions VI, VII, and VIII. Northern Panay was heavily damaged.

The 18.5% of LGUs were vulnerable to tornadoes and the 4.3% were highly susceptible. A tornado is a violent rotating column of air pendant from a cumulonimbus cloud, and nearly always observable as a funnel cloud or tuba (Huschke 1959 as cited by Fujita and Smith 1993). The Philippines is prone to severe tornadoes (Mainul et al. 2003; Fujita 1973).

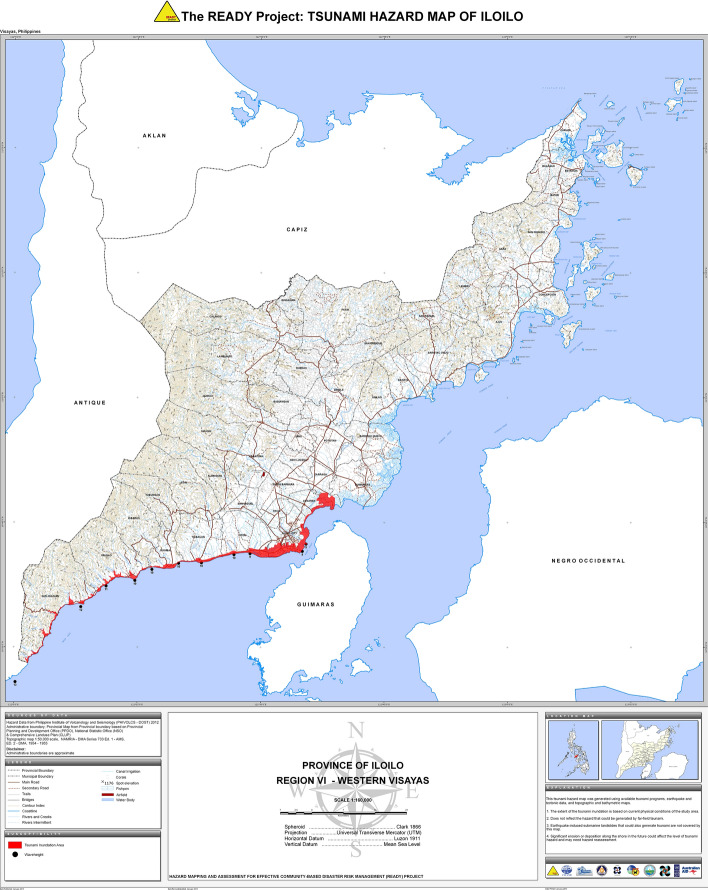

Tsunami waves may likely hit the 21.7% of LGUs in Panay Island while the 6.5% were highly vulnerable. Paine (1999) terms tsunami as waves created by a sudden disturbance in the ocean. It is caused by earthquakes and underwater landslides.

As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, the west, south and east coasts of Panay Island, except the north and the northeast are prone to local tsunami triggered by an earthquake originating from the Negros Trench or Collision Zone. A magnitude 7.1 earthquake hit the island of Mindoro, northwest of Panay, on November 15, 1994 killing 78 people (PHIVOLCS 2019).

Fig. 5.

Tsunami-prone coastal areas in the province of Iloilo, Panay Island, Philippines

Fig. 6.

Tsunami-prone coastal areas in the province of Antique, Panay Island, Philippines

Rain and earthquake-induced landslides pose threats to upland areas and populated communities in valleys near the mountain or hill. In Panay, 37% of areas were vulnerable and 25% were highly vulnerable.

Landslide is a downslope movement of soil and rock affected by gravity (Malamud et al. 2004 as cited by Chen et al. 2017). In February 2006, a disastrous rockslide-debris avalanche killed over 1,100 people in Guinsaugon, Leyte, and central Philippines. It followed a period of very heavy rainfall with a lag time of 4 days (Evans et al. 2007). Figure 4 pinpoints the upland municipalities, west of Panay Island, as very highly and highly vulnerable to landslide. It is where the Madias (Madya-as) mountain range stretches from northwest to the southwest.

Countermeasures of local governments against natural hazards

The Philippine DRRM Act of 2010 cascaded disaster management functions from the national down to local governments through the partnership of mandated public offices. The Department of National Defense (DND) chairs the inter-agency National DRRM Council. The vice chairs are the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for prevention and mitigation, DILG for preparedness, Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) for response, and the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) for rehabilitation and recovery. The OCD, a bureau under the DND, administers a comprehensive national civil defense and DRRM program by providing leadership in the continuous development of strategic and systematic approaches as well as measures to reduce the vulnerabilities and risks to hazards and manage the consequences of disasters. It chairs each of the inter-agency Regional DRRM Council that coordinates, integrates, supervises, and evaluates the activities of the local DRRM Council in every province, city, municipality/town, and barangay/village. As an exemption, the Regional Governor of the BARMM chairs its own Regional DRRRM Council (Ibid p. 4).

The governors of provinces, mayors of cities and municipalities, and the punong barangays of villages head the local DRRM Councils. The central government cannot fully control them since a national legislation, Local Government Code of 1991, granted them more autonomy. They can appoint permanent or temporary disaster managers. Like the National and Regional DRRM Councils, member agencies share resources and tasks in preparing for or responding to calamities (Ibid p. 4) resulting to synergy.

As front liners, local governments face the greatest challenge as they directly respond to natural hazards. A failure at the local-level adversely affects the overall performance of the Regional and National DRRM Councils.

Table 3 shows the preparedness of 92 municipalities in 4 areas of the Philippine government-designed LGU Disaster Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors. The local governments were partially prepared in Systems and Structures, which plan and implement DRRM measures. Meanwhile, COA (2014) found a problem in the collaboration and coordination among the components of these local structures and system. LGUs had designated evacuation centers, but there were no security post, signs leading to evacuation areas, temporary shelter for livestock, and evacuation center for prisoners.

Table 3.

Preparedness of local governments in the 4 areas of Philippine government-designed LGU disaster preparedness journal: checklist of minimum actions for mayors

| Overall weighted mean | Verbal interpretation | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Systems and structures | ||

| Mobilization of DRRM structures and activation of systems and processes | 2.71 | Prepared |

| Evacuation and Relief | 1.74 | Partially prepared |

| Grand mean | 2.22 | Partially prepared |

| 2. Policies and plans | ||

| Early warning | 2.09 | Partially prepared |

| Mobilization of DRRM structures and activation of systems and processes | 1.89 | Partially prepared |

| Evacuation and Relief | 1.50 | Not prepared |

| Search and Rescue | 1.70 | Partially prepared |

| Mobilization of DRRM Structures and Activation of Systems and Processes | 1.82 | Partially prepared |

| Grand mean | 1.88 | Partially prepared |

| 3. Building competencies | ||

| Early warning | 2.24 | Partially prepared |

| Evacuation and relief | 1.96 | Partially prepared |

| Mobilization of DRRM structures and activation of systems and processes | 2.22 | Partially prepared |

| Search and rescue | 2.88 | Prepared |

| Lifelines | 1.65 | Not prepared |

| Grand mean | 2.14 | Partially prepared |

| 4 Equipment and supplies | ||

| Early warning | 2.41 | Prepared |

| Mobilization of DRRM structures and activation of systems and processes | 2.79 | Prepared |

| Evacuation and relief | 2.18 | Partially prepared |

| Search and rescue | 2.85 | Prepared |

| Lifelines | 2.14 | Partially prepared |

| Grand mean | 2.39 | Prepared |

| Overall grand mean | 2.16 | Partially prepared |

Policies and Plans include establishing Memorandum of Agreements with stakeholders; signing a resolution to cancel the authority to travel of critical DRRM responders when they are needed; and preparing Local DRRM Plan, Local Climate Change Action Plan, Annual Investment Plan, and the Business Continuity Plan. Overall results found that the LGUs were partially prepared.

Using innovative and traditional media in massive and timely dissemination of right information across multiple languages are effective during disasters (Backfried et al. 2016). It should be backed up by properly-trained responders (Coule and Horner 2007). The third area of disaster preparedness is Building Competencies. It is comprised of early warning, evacuation and relief, mobilization of DRRM structures and activation of systems and processes, search and rescue, and lifelines. Data bared that local governments were partially prepared.

The provision of Equipment and Supplies is the final area of disaster preparedness. It is categorized into early warning, mobilization of DRRM structures and activation of systems and processes, evacuation and relief, search and rescue, and lifelines. The 92 municipalities were prepared. An overall grand mean of 2.16 revealed that Panay Island was partially prepared against the ten identified natural hazards.

As noticed in the checklist, the levels of preparedness of LGUs in four criteria were lumped into one instead of per hazard. The average preparation of one local government was taken into consideration disregarding each component of their gross initiatives.

In the overall preparedness of four provinces, Aklan and Antique were prepared while Capiz and Iloilo were partially prepared. The OCD previously recognized the DRRM efforts of the municipality of San Jose de Buenavista in Antique and province of Capiz at the national level. Aklan became the regional champion recently. Iloilo has been investing in logistics.

All municipalities were partially prepared regardless of profile, but local governments situated in coastal areas were more partially prepared than those in upland and on plain. It was good because these areas were vulnerable to the identified natural hazards, except landslide. There was a match between their levels of vulnerability and preparedness.

Having more financial resources, first class LGUs were more partially prepared than the other classes except the third class. Most populated local governments were more partially prepared too. These areas intensified their DRRM countermeasures since they have the most number of people at risk. It suggests that there was a fit in the number of vulnerable persons with the level of preparedness.

LGUs with lesser number of barangays or villages had higher levels of preparation compared to those with more. Local governments with a land area of 15,001–30,000 hectares had higher level of preparedness than areas below or above this range.

When grouped as to their level of vulnerability, the local governments both highly vulnerable and vulnerable to flood, storm surge, drought, tropical cyclone, tornado, tsunami, and landslide were partially prepared against these natural hazards. However, the areas considered highly vulnerable to earthquake and forest fire were prepared. The 3 LGUs vulnerable to hailstorm were also prepared. There were local governments not vulnerable to each of the 9 natural hazards—flood, storm surge, earthquake, hailstorm, forest fire, tropical cyclone, tornado, tsunami, and landslide yet partially prepared. Not even one local government rated highly vulnerable and vulnerable was not prepared. It denotes that minimal preparations were done prior to the strike of natural hazards that they knew would likely hit them anytime.

Problems encountered in executing countermeasures against natural hazards

The 6 leading challenges in carrying out countermeasures were the diverse attitudes among stakeholders, insufficient manpower occupying permanent positions, poor database management, insufficient financial appropriations, inadequate guidelines, and support. This finding corroborates the report of COA (2014) which identified the weaknesses of the country’s DRRM lack of capacity, lack of systematic distribution, and inadequately trained and equipped response team. The assessment further unveiled the poor information management on donors, governance aspect and analysis of government spending.

Conclusion

Since 52.2% of local governments in Panay Island were highly populated, they had a great number of people at risk. One half of LGUs with coastal communities were prone to tropical cyclone (strong wind), storm surge, and tsunami.

The level of susceptibility of areas to tropical cyclone (strong wind), storm surge, earthquake, and tsunami was based on available historical data and respondents’ experiences as front liners in past years and not on hazard maps. The 37% of LGUs not vulnerable to a damaging earthquake might not have felt strong ground shaking with a magnitude of ≥ 5.0 in 3 decades. These areas are situated northeast of Panay Island. Unlike other hazards, large earthquakes do not strike a single area every year. Hainzl et al. (2000) observed that a seismic quiescence period is an indicator for a coming large earthquake.

Bautista et al. (2011) bared that a catastrophic earthquake rocked the island 30 years ago on June 14, 1990. Historical earthquakes with magnitude of > 7.0 occurred in 1621, 1778, 1887, and 1948. The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) (2018) reveals that the active West Panay Fault traverses the northern, central and southern parts of the island. Figure 3 unveils that the other earthquake generators are the collision zone, west of Panay Island, and Negros Trench in the south. The Masbate segment of the Philippine Fault triggered a magnitude 6.6 earthquake in the island of Masbate, northeast of Panay, on August 18, 2020. It was also felt in northern Panay, except in the northeast.

The 4.3% of local governments not vulnerable to a tropical cyclone (severe wind) might not have been struck by severe wind having a speed of ≥ 100 km/h in past years. The entire Panay Island is vulnerable to this hazard, but areas in the southwest are less affected.

The level of preparedness in nine municipalities with the lowest annual revenue collection of US$0.297–0.475 M might have been influenced by their minimal fund for DRRM.

All municipalities had functional DRRM offices, yet the unmet requirements on evacuation and relief functions gave them a rating of partially prepared in the first 2 areas of DRRM—Systems and Structures and Policies and Plans. Their failure to build alliances with other organizations and to organize trainings on business continuity plan, infrastructure audit, and media management led to a partially prepared assessment in the third area of Building Competencies. The LGUs were prepared only in the fourth area, i.e., equipment and supplies. It was the outcome of reforms in governance that the Philippine DRRM Act of 2010 has brought. Most of their encountered challenges were related to human resources and stakeholders’ attitudes.

The high turnover rate in most DRRM offices was not viewed as a challenge because it has been a routine, and looking for replacement has been easy. However, government funds allotted to professional development were wasted when the well-trained, yet temporary, staff were laid off when new elected local officials assumed posts. They used to quit when a higher-paying, tenured position is found somewhere else.

Recommendations

The DRRM plans of 4 provinces conform to international and national standards. Introducing few updates and additional inputs may upgrade their partially prepared level in disaster preparedness.

Funding the creation of a functional Barangay (village) DRRM Office will make disaster response more quickly and community-based. Lack of financial resources hampers most villages from activating their rescue and relief teams. Providing insurance coverage and competitive honoraria to responders will attract volunteers. Hashemipour et al. (2017) oppose a preparedness system for disaster response and coordination that is oriented toward a large-scale view of disaster events. They argued that local volunteers can help emergency managers effectively coordinate available community resources to minimize the number of casualties and reduce the operation-response completion time.

As global warming increases the frequency and fury of climate-related hazards (Höppe and Grimm 2008), LGUs need to boost countermeasures against tropical cyclone (strong wind), flood, and storm surge. Earthquake preparedness is likewise crucial since the most recent damaging event happened three decades ago. Stored energy is enough to ruin poorly-built structures in this vulnerable island. Preparedness needs be based on hazard maps from mandated offices and not merely on historical data and past occurrences.

When disasters do not strike in a year, fully utilize 70% of the calamity fund by increasing the number and capacity of evacuation centers at the village level; purchasing additional equipment, tools, and supplies; conducting mandatory drills; and developing human resources. Consider the long-term investments for mobile public address system, satellite phones, mobile water treatment facilities, and generator sets for lifelines. Temporary shelters for livestock and putting up sign boards leading to evacuation areas are helpful to evacuees.

Designating an interim disaster manager handling other full-time administrative functions impairs the DRRM office from making appropriate plans. Training for staff requires to be routine when there is mass lay off of temporary workers. This happens when a new governor or mayor is elected. If creating new permanent positions is hard, a competitive pay for contract workers will decrease the turnover rate and budget for constant training of new staff. Returning to the national treasury an unutilized calamity fund denotes willful apathy of a disaster-prone area to prepare for calamities.

Collaborating with national offices in doing massive information drive can change the negative attitude of stakeholders toward DRRM, which must also be integrated into the school curricula and mandatory trainings for elected youth leaders and government officials. Shaw et al. (2004) found that school education coupled with self, family, and community education can help students develop a “culture of disaster preparedness”, which, in turn, will urge them to take right decisions and actions as an adult.

Demolition of illegally-constructed houses and fish ponds that block waterways, dredging of silted rivers, regulating quarrying activities, relocating residential houses from flood-prone areas, and drainage improvement are vital. The proposed Panay River Basin Integrated Development Project will stop perennial flooding in the rice and cultured fish-producing municipalities in Capiz. It will re-route waterways that overflow. The province of Iloilo has benefitted from its flood control project conceived after Tropical cyclone Fengshen (locally named Frank) submerged low-lying areas in June 2008. Räsänen and Kummu (2013) observed that annual flood period is longer during La Niña phenomenon.

A concerted effort with the National Irrigation Administration will allay the effects of drought to farmers. Additional dams cease water crisis in some highly urbanized areas. Tree growing and relocating residents from landslide-vulnerable areas are useful. There is a need to beef up partnerships with civil society organizations, community volunteers, and local chamber of commerce and industry (Kapuco and Demiroz 2017). The resources of these groups can strengthen the weaknesses of local governments.

Low-earning LGUs can ask the OCD and foreign institutions to fund DRRM projects, but there must be proper tracking of donations from external institutions. The pattern of spending DRRM funds can be analyzed to gain an insight on the proper use of fund.

There should be preparedness for a major eruption of Kanlaon Volcano. Located in the neighboring island of Negros, southeast of Panay, it is one of the large and most active volcanoes (PHIVOLCS 2019). Its ash fall, during a major explosion, may reach Panay Island when the wind moves to the northwest, west, and north directions. The ash of a farther Mt. Pinatubo Volcano in northern Philippines affected Panay when it erupted in June 1991.

Straightening mistakes and learned lessons will strengthen the countermeasures of local governments for an emerging emergency like the COVID-19 pandemic, which made Philippines the worst hit country in Southeast Asia in terms of the number of infected persons. Health experts, the private sector, and local and central governments should agree on ways of stopping the spread of infection. Local legislators can pass ordinances that will end the disease.

There is a need to open the bureaucracy for reforms and flexibility in this period of new normal as long as transparency and accountability are heeded. Make sure operations amid the pandemic are unhampered through technology, e-procurement, electronic signature, and online meetings. Hiring IT staff will enable local governments develop a disaster information management system crucial in sound, timely decision making. Tripling the number of beds and enhancing the capabilities of government hospitals are crucial during emergencies. Providing state subsidy to trained nurses of private hospitals will discourage them from leaving the country. Public hospitals cannot accommodate them all, and private healthcare providers can reinforce government infirmaries. The incidence of dengue fever, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and rabies infection also demand the attention of authorities.

The 2014 LGU Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors may advise local governments to measure their level of vulnerability to disasters based not only on historical data and past occurrences of calamities but also on hazard maps. A magnitude 7.2 earthquake awed the province of Bohol in 2013 since the island had no catastrophic tremor in four decades. Finally, the preparedness of LGUs in the areas of Systems and Structures, Policies and Plans, Building Competencies, and Equipment and Supplies was lumped into one. It is better if the assessment in each of the four areas be hazard specific. It may defeat the evaluation process since one LGU might be prepared for floods but not for earthquake.

Acknowledgements

The researchers extend gratitude to the following organizations and officials that were behind the feat of this study: Dr. Editha Alfon, Dr. Editha Magallanes, Chancellor Ricardo Babaran, Dean Ma. Dorothee Villarruz, Dean Arthur Barrido, Jr., Department of the Interior and Local Government, Office of Civil Defense, Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Mines and Geosciences Bureau Region 6, Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Offices in Panay Island, Local government officials in Panay Island, National and Regional Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Councils, Capiz State University, University of the Philippines Visayas, Civil Service Commission, and Cabugcabug National High School.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JD, JLA and RA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JD and JLA and all authors commented on the previous version of the manuscript. The second draft and final manuscript were written by RA incorporating the minor suggestions by the other two authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors funded this study. Capiz State University provided US$139 to Dr. Johnny Dariagan and Prof. Jay Lord Asis as financial assistance to the researchers. The said amount represented about 3% of the total expenses. The University of the Philippines Visayas deducted the subject load of Prof. Ramil Atando to give him enough time for writing the final manuscript. The de-loading did not affect his salary.

Availability of data and material

The detailed data and materials used as bases in completing the manuscript are available upon request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Johnny D. Dariagan, Email: jddariagan@capsu.edu.ph

Ramil B. Atando, Email: rbatando@up.edu.ph

Jay Lord B. Asis, Email: jlasis1984@gmail.com

References

- Achoka JSK, Maiyo J. Horrifying disasters in western Kenya: impact on education and national development. Educ Res Rev. 2008;3:154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Andriesse E. Primary sector value chains, poverty reduction, and rural development challenges in the Philippines. Geogr Rev. 2018;108:345–366. doi: 10.1111/gere.12287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M. Disaster reconstruction and risk management for poverty reduction. J Int Aff. 2006;59:269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Backfried G, Schmidt C, Aniola D, Meurers C, Mak K, Göllner J, Peer A, Quirchmayr G, Czech G, Glanzer M. A general framework for using social and traditional media during natural disasters: Quoima and the central European floods of 2013. Fusion Methodol Crisis Manag. 2016 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22527-2-22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista M L, Bautista B, Narag I, Atando R, Relota E (2011) The January 25, 1948 (Ms 8.1) Lady Caycay earthquake. In: Proceedings at the 9th Pacific conference on earthquake engineering (PCEE): building an earthquake-resilient society, Auckland, New Zealand. https://www.nzsee.org.nz/db/2011/029.pdf. Accessed 8 February 2017

- Von Bertalanffy L. The history and status of general systems theory. Acad Manag J. 1972;15:407–426. doi: 10.5465/255139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bui AT, Dungey M, Nguyen CV, Pham TP. The impact of natural disasters on household income, expenditure, poverty and inequality: evidence from Vietnam. J Appl Econ. 2014;46:1751–1766. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2014.884706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cas AG. Typhoon aid and development: the effects of typhoon-resistant schools and instructional resources on educational attainment in the Philippines. Asian Dev Rev. 2016;33:183–201. doi: 10.1162/ADEV-a-00065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo E, Galiani S, Noy I, Pantano J. Catastrophic natural disasters and economic growth. Rev Econ Stat. 2013;95:1549–1561. doi: 10.1162/REST-a-00413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chantraket P, Kirtsaeng S, Detyothin C, Nakburee A, Mongkala K. Characteristics of Hailstorm over Northern Thailand during summer season. Environ Asia. 2015;8:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Xie X, Peng J, Wang J, Duan Z, Hong H. GIS-based landslide susceptibility modelling: a comparative assessment of Kernel logistic regression, Naïve-Bayes tree, and alternating decision tree models. Geomat Nat Hazards Risk. 2017;8:950–973. doi: 10.1080/19475705.2017.1289250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codamon-Quitzon S (1991) Fires, forests, and tribes in the Northern Philippines: cultural and ecological perspectives. Fire in the environment: ecological and cultural perspectives, In: Proceedings of an international symposium 414–417. https://books.google.com.ph/books?hl=en&lr=&id=TwVcDLZM1HkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA414&dq=Fires,+forests+and+tribes+in+the+northern+Philippines+by+CodamonQuitzon&ots=RzMmWCS0yg&sig=Uucon49vyzWuRF8L1-K_eMLbbVo&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 2 October 2019

- Commission on Audit (2014) Disaster management practices in the Philippines: an assessment. COA Report.https://www.coa.gov.ph/disaster_audit/doc/National.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2015

- Coule PL, Horner JA. National disaster life support programs: a platform for multi-disciplinary disaster response. Dent Clin N Am. 2007;51:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalisay SN, De Guzman MT. Risk and culture: the case of typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Dis Prev Manag. 2016;25:701–714. doi: 10.1108/DPM-05-2016-0097/full/html. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danard M, Munro A, Murty T. Storm surge hazard in Canada. Nat Hazards. 2003;28:407–434. doi: 10.1023/A:1022990310410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) (2018) Regional Office 6. https://www.r6.denr.gov.ph/index.php/about-us/regional-profile. Accessed 10 May 2018

- Department of the Interior and Local Government. LGU Disaster Preparedness Journal: Checklist of Minimum Actions for Mayors. http://downloads.caraga.dilg.gov.ph/Disaster%20Preparedness/Journal.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2015

- Elsner JB, Liu KB. Examining the ENSO-typhoon hypothesis Clim Res. 2003;25:43–54. doi: 10.3354/cr025043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enteria NA. CFD evaluation of Philippine detached structure with different roofing designs. Infrastructures. 2016;1:3. doi: 10.3390/infrastructures1010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SG, Guthrie RH, Roberts NJ, Bishop NF. The disastrous 17 February 2006 rockslide-debris avalanche on Leyte Island, Philippines: a catastrophic landslide in tropical mountain terrain. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2007;7:89–101. doi: 10.5194/nhess-7-89-2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita TT. Tornadoes around the world. Weatherwise. 1973;26:56–83. doi: 10.1080/00431672.1973.9931633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita TT, Smith BE. Aerial survey and photography of tornado and microburst damage. Geophys Union Geophys Monogr Ser. 1993;79:479–493. doi: 10.1029/GM079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Ashcroft A. Connecting and communicating after typhoon Haiyan. Forced Migr Rev. 2014;45:95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hainzl S, Zöller G, Kurths J, Zschau J. Seismic quiescence as an indicator for large earthquakes in a system of self-organized criticality. Geophys Res Lett. 2000;27(5):597–600. doi: 10.1029/1999GL011000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemipour M, Stuban SME, Dever JR. A community-based disaster coordination framework for effective disaster preparedness and response. Aust J Emerg Manag. 2017;32:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Healy A, Malhotra N. Myopic voters and natural disaster policy. Am Political Sci Rev. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1017/S0003055409990104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Höppe P, Grimm T. Rising natural catastrophe losses: what is the role of climate change? In: Antes R, editor. Hansjürgens B. Springer, New York: Economics and management of climate change; 2008. pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Izodkhah Y, Hosseini M. Towards resilient communities in developing countries through education of children for disaster preparedness. Int J EmergManag. 2005;2:138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kapuco N, Demiroz F (2017). Inter-organizational networks in disaster management. In Social Network Analysis of Disaster Response, Recovery, and Adaptation 2017:25–39. Butterworth-Heinemann. 10.1016/B978-0-12-805196-2.00003-0

- Katz D, Kahn RL (1966) The social psychology of organizations. https://garfield.library.upenn.edu/classics1980/A1980JY55100001.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2018

- La Viña T, Tan M (2015). It’s time to reform our disaster law. rappler.com. https://www.rappler.com/thought leaders/112048-reform-ph-disaster-law. Accessed 10 December 2019

- Lagmay AMF, Agaton RP, Bahala MAC, Briones JBLT, Cabacaba KMC, Caro CVC, Mungcal MTF. Devastating storm surges of Typhoon Haiyan. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015;11:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Vink K. Assessing the vulnerability of different age groups regarding flood fatalities: Case study in the Philippines. Water Policy. 2015;17:1045–1061. doi: 10.2166/wp.2015.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loayza N, Olaberria E, Rigolini J, Christiaensen L. Natural disasters and growth: going beyond the averages. World Dev. 2012;40:1317–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lum T, Margesson R (2014) Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda): U.S. and international response to Philippines disaster. Current politics and economics of south, South-eastern, and central Asia 23:209–246. https://search.proquest.com/openview/4583721e1283e9672756f878840eec7a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2034881. Accessed 20 January 2020

- Maglinao AR, Armada AB (1998) Research and development and other intervention for alleviating the damaging effects of drought in the Philippines. In Symposium/Workshop on protecting and rehabilitating high risk areas, Los Baños, Laguna (Philippines). https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=PH2000100148. Accessed 12 April 2019

- Mainul H, Robson P. Bangladesh and the Philippines: the health reform process. J Comilla Med Coll Teach As. 2003;5:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Merone L, Tait P. Preventing disaster in the pacific islands: the battle against climate disruption. Aust New Zealand J Public Health. 2018;42:419–420. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mines and Geosciences Bureau Region 6. MGB Preliminary Landslide and Flood Hazard Map of Region VI. https://www.mgb6.org/gallery. Accessed 8 July 2017

- Nakamura R, Shibayama T, Esteban M, Iwamoto T. Future typhoon and storm surges under different global warming scenarios: Case study of typhoon Haiyan (2013) Nat Hazards. 2016;82:165–1681. doi: 10.1007/s11069-016-2259-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Economic and Development Authority (2017) Western Visayas economy grows 6.1% in 2016. https://www.nro6.neda.gov.ph/western-visayas-economy-grows-6-1-in-2016/. Accessed 16 July 2017

- O’Connell EP, Abbott RP, White RS. Religious struggles after typhoon Haiyan: a case study from Bantayan Island. Dis Prev Manag. 2017;26:330–347. doi: 10.1108/DPM-02-2017-0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Civil Defense. NDRRMC coordinates sending of relief to areas pummeled by Typhoon Ursula. https://www.ocd.gov.ph/news/589-ndrrmc-coordinates-sending-of-relief-to-areas-pummeled-by-typhoon-ursula.html. Accessed 17 Jan 2020

- Office of Civil Defense. Families affected by Typhoon Ursula continue to receive aid from NDRRMC. https://www.ocd.gov.ph/news/590-families-affected-by-Typhoon-Ursula-continue-to-receive-aid-from. Accessed 17 January 2020

- Office of Civil Defense. NDRRMC approves Philippine disaster rehabilitation and recovery planning guide. https://www.ocd.gov.ph/news/592-nddrmc-approves-Philippine-disaster-rehabilitation-and-recovery-planning-guide.html. Accessed 18 Jan 2020

- Paine MP. Asteroid impacts: The extra hazard due to tsunami. Sci Tsunami Hazards. 1999;17:155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Pe Symaco L. Geographies of social exclusion: Education access in the Philippines. CompaEduc. 2013;49:361. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2013.803784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peñalba LM, Elazegui DD, Pulhin JM, Cruz RVO. Social and institutional dimensions of climate change adaptation. Int J Clim Change StrategManag. 2012;4:308–322. doi: 10.1108/17568691211248748/full/html. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010 (2010) Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2010/05/27/republic-act-no-10121/. Accessed 29 December 2017

- Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. PHIVOLCS hazard maps. https://www.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph. Accessed 3 Feb 2018

- Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Primer on the 18 August 2020 magnitude (Mw) 6.6 Masbate Earthquake. https://www.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/index.php/news/10460-primer-on-the-18-august-2020-magnitude-mw-6-6-masbate-earthquake

- Philippine Statistics Authority (2016) Population of Region VI-Western Visayas (Based on the 2015 census of population). https://www.psa.gov.ph/content/population-region-vi-western-visayas-based-2015-census-population. Accessed 10 Mar 2018

- Quarantelli EL. Ten criteria for evaluating the management of community disasters. Disasters. 2002;21:39–56. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räsänen TA, Kummu M. Spatiotemporal influences of ENSO on precipitation and flood pulse in the Mekong River Basin. J Hydrol. 2013;476:154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reacher M, McKenzie K, Lane C, Nichols T, Kedge I, Iverson A, Hepple P, Walter T, Laxton C, Simpson O. Health impacts of flooding in Lewes: a comparison of reported gastrointestinal and other illness and mental health in flooded and non-flooded households. Commun Dis Public Health. 2004;7:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins R, Coulter M. Management. 14. United Kingdom: Pearson education limited; 2018. pp. 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Oreggia E, De La Fuente A, De La Torre R, Moreno H. Natural disasters, human development and poverty at the municipal level in Mexico. J Dev Stud. 2013;49:442–455. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2012.700398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scannel L, Cox RS, Fletcher S, Heykoop C. That was the last time I saw my house: the importance of place attachment among children and youth in disaster contexts. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58:158–173. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R, Kobayashi KSH, Kobayashi M. Linking experience, education, perception and earthquake preparedness. Disaster Prev Manag. 2004;13:39–49. doi: 10.1108/09653560410521689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tansey E. Archival adaptation to climate change. Sustain Sci Pract Policy. 2015;11:45–56. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2015.11908146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2016) Sustainable development goals. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html. Accessed 4 September 2017

- United Nations office for disaster risk reduction (2015) Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 1:1–37. https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015–2030. Accessed 12 June 2018

- Van Loon AF (2013) On the propagation of drought: how climate and catchment characteristics influence hydrological drought development and recovery. Dissertation, Wageningen University. https://www.research.wur.nl/en/publication/on-the-propagation-of-drought-how-climate-and-catchment-characteristics-influence-hydrological-drought-development-and-recovery. Accessed 3 April 2020

- Vlachos NA, Paras SV, Mouza AA, Karabelas AJ. Visual observations of flooding in narrow rectangular channels. Int J Multiph Flows. 2001;27:1415–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0301-9322(01)00009-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walia A. Community-based disaster preparedness: need for a standardized training module. Aust J Emerg Manag. 2008;23:441–454. [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoob A. Farmers’ perception regarding environmental impacts on livelihood of rice-growing families. Inte J Agric Ext. 2017;5:145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav DK, Barve A. Prioritization of cyclone preparedness activities in humanitarian supply chains using fuzzy analytical network process. Nat Hazards. 2019;97:683–726. doi: 10.1007/s11069-019-03668-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Zhang Z, Han S, Qu C, Yuan Z, Zhang D. SVM based forest fire detection using static and dynamic features. Comput Sci Informa Syst. 2011;8:821–841. doi: 10.2298/CSIS101012030Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The detailed data and materials used as bases in completing the manuscript are available upon request.