Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of low inclusion levels of organic trace minerals (iron, copper, manganese, and zinc) on performance, eggshell quality, serum hormone levels, and enzyme activities of laying hens during the late laying period. A total of 405 healthy hens (HY-Line White, 50-week-old) were randomly divided into 3 treatments, with 9 replications per treatment and 15 birds per replication. The dietary treatments included a basal diet supplemented with inorganic trace minerals at commercial levels (CON), a basal diet supplemented with inorganic trace minerals at 1/3 commercial levels (ITM), and a basal diet supplemented with proteinated trace minerals at 1/3 commercial levels (TRT). The trial lasted 56 D (8 wk). Compared with the CON group, the ITM group showed decrease in (P < 0.05) egg production, eggshell strength, eggshell palisade layer, palisade layer ratio, serum estrogen, luteinizing hormone, glycosaminoglycan concentration, and carbonic anhydrase activity and increase in (P < 0.05) egg loss and mammillary layer ratio. However, the TRT group almost kept all the indices close to the CON group (P > 0.05). Furthermore, hens fed with low inclusion levels of organic trace minerals had smaller mammillary knobs (P < 0.05) than those in the CON and ITM groups. In conclusion, hens fed with low inclusion levels of proteinated trace minerals had better performance and eggshell strength than those fed with identical levels of inorganic compounds; organic trace minerals improved eggshell quality by improving the eggshell ultrastructure of laying hens during the late laying period.

Key words: organic trace mineral, performance, eggshell quality, serum index, laying hen

Introduction

About 10 to 15% of eggs are lost owing to eggshell quality problems before or during egg collection, causing great economic losses (Stefanello et al., 2014). Hence, eggshell quality is a major concern for production of the highest quality eggs, and it has a significant impact on the commercial egg industry. Commercial processing and marketing of eggs often results in a higher proportion of eggshells rupturing or breaking (Xiao et al., 2014). Furthermore, as laying age increases, the size of the eggshell increases, but the weight of the eggshell does not concomitantly increase, resulting in the reduction of eggshell strength (Washburn, 1982). Endometrium morphology will change as the hen ages, causing abnormal eggshell formation and thus degradation of eggshell quality (Park and Sohn, 2018). Previous studies have explored many nutritional strategies to improve the quality of eggshells. A large amount of research has focused on the effects of calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D3 on eggshell quality (Bar and Hurwitz, 1984, Goodsonwilliams et al., 1987, Neijat et al., 2011). However, how trace minerals affect eggshell quality remains to be further studied.

The eggshell is formed as a highly ordered and mineralized structure through the stages of mammillary layer formation, linear calcification, and termination (Zhang et al., 2017b). The composition of the eggshell includes organic and inorganic components. Among them, the organic components include the matrix, eggshell membrane, mammillary knob, and cuticle (Solomon, 2010). The inorganic component is mainly calcium carbonate crystals, which accounts for 94 to 97% of the weight of the whole eggshell (Stefanello et al., 2014, Xiao et al., 2014). Factors influencing the strength of eggshells are very complex and may reflect the interaction between the organic and inorganic components. Therefore, the evaluation of the ultrastructure of eggshells provides us a better understanding of the eggshell structure and further recognizes that the simple measurement of eggshell thickness does not do enough to evaluate the mechanical properties of eggshells when exploring trace minerals (Nys et al., 2004, Stefanello et al., 2014). The eggshell is divided into eggshell membrane, mammillary layer, palisade layer, crystal layer, and cuticle from the inside to the outside (Nys et al., 1999, Hincke et al., 2012). Relevant studies show that the total thickness of the eggshell, the palisade layer and mammillary layer ratio, and the density and width of mammillary knobs affect the strength of the eggshell. (Ahmed et al., 2005, Dunn et al., 2012). Eggshell membrane, a kind of fibrous membrane, is composed of the inner membrane and outer membrane, which is important for embryonic development (Berwanger et al., 2018, Park and Sohn, 2018). The mammillary layer is calcified from the nucleation sites on the outside of the outer membrane and finally forms basal parts of calcified columns and knobs (Parsons, 1982, Zhang et al., 2017b, Athanasiadou et al., 2018). Low-quality eggshells tend to have larger mammillary knobs and have higher porosity or irregular arrangement (Li et al., 2018a; Park and Sohn, 2018). The palisade layer consists of calcium carbonate calcite crystals, accounting for two-thirds of the total thickness of the eggshell (Ruiz and Lunam, 2000, Fathi et al., 2007). Previous studies have reported that the reduction in the average size of calcite crystals contributes to high strength against breakage to the eggshell and shell thickness (Ahmed et al., 2005, Fathi et al., 2016). The eggshell calcification ends with cuticle secretion. The cuticle is the outermost biological barrier that protects the eggs.

Trace minerals, which participate in growth and development of animals, including the formation of the eggshell and bone, are essential for laying hens (Richards et al., 2010). Trace minerals may act as activators or components of enzymes involved in eggshell synthesis or directly interact with calcium crystals during eggshell formation, which affects the quality of the eggshell (Fernandes et al., 2008, Xiao et al., 2014). Most mineral additives currently used in livestock production come from inorganic compounds such as oxides, sulfates, carbonates, and phosphates (Stefanello et al., 2014). Antagonisms of dietary inorganic minerals can result in decreased absorption, leading to inorganic mineral salts being excessively supplied in commercial feeds to prevent deficiencies, which causes concern for environmental pollution (Aksu et al., 2011). Organic trace minerals have been shown to be more bioavailable than inorganic mineral salts and could be used at a lower inclusion level (Mabe et al., 2003, Liu et al., 2014). Some previous studies have reported that organic trace minerals have better effect than inorganic trace minerals at the same or higher level in improving eggshell quality and ultrastructure (Stefanello et al., 2014, Xiao et al., 2015, Bai et al., 2017). However, most of them only focused on the effects of a single trace mineral or at a single aspect. The use of multiple organic trace minerals, including iron (Fe), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), and zinc (Zn), replacing inorganic trace minerals synchronously, and what kind of influence they will have on the egg quality of commercial laying hens during the late laying period need further systematic research.

The objective of the present study was, therefore, to evaluate the effects of organic trace minerals, at low inclusion levels completely replacing inorganic trace minerals, on performance, eggshell quality, serum hormone levels, and enzyme activities of laying hens during the late laying period.

Materials and methods

Birds and Management

A total of 405 healthy hens (HY-Line White, 50-week-old) with similar body weight and egg-laying rates were used in the 8-week feeding trial. There were 3 dietary treatments, and each treatment had 9 replications with 15 birds per replication. The dietary treatments included a basal diet supplemented with inorganic trace minerals at commercial levels (CON; Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn at 36, 12, 90, and 90 mg/kg, respectively, which were designed on the basis of the average survey data from major feed enterprises in China), a basal diet supplemented with inorganic trace minerals at 1/3 commercial levels (ITM; Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn at 12, 4, 30, and 30 mg/kg, respectively), and a basal diet supplemented with proteinated trace minerals at 1/3 commercial levels (TRT; Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn at 12, 4, 30, and 30 mg/kg, respectively). The experimental diets were formulated according to NRC (1994) recommendation to meet daily nutrient requirement of the hens for the late laying period and modified as per Chinese standards (NY/T 33-2004; The Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China, 2004.). The composition and nutrient levels of the basal diet are presented in Table 1. The contents of Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn in the experimental diets were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (model ELAN DRC-e, PerkinElmer Scientific Inc., Billerica, Massachusetts) and are listed in Table 2. Hens were raised in the Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition and Feed in East China of Ministry of Agriculture. In the same chicken house, the experimental hens were raised in a three-tiered three-dimensional cage (each replicate unit consisting of 5 cages of 3 birds each, with each cage measuring 45 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm) with feed and water provided ad libitum. The birds were standardized by weight and egg production, and subjected to 14-D adjustment to the experimental diets before starting the experiment. Lighting, temperature, and humidity were set according to the conventional standards of commercial egg farms.

Table 1.

Ingredient and nutrient composition of the basal diet.

| Ingredients | Content (%) | Nutrient levels2 | Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 57.00 | ME/(Mcal/kg) | 2.63 |

| Soybean meal | 24.00 | CP | 16.45 |

| Calcium carbonate | 8.50 | Lys | 0.89 |

| Wheat middling | 5.00 | Met | 0.45 |

| Emulsified fat powder | 1.50 | Cys + Met | 0.73 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate | 1.00 | Ca | 3.66 |

| Sodium chloride | 0.30 | P | 0.56 |

| DL-Methionine | 0.12 | AP | 0.35 |

| Lysine-HCl | 0.08 | ||

| Premix1 | 2.50 | ||

| Total | 100.00 |

Abbreviation: AP, available phosphorus.

The premix without trace minerals provided the following per kg of the diet: vitamin A, 12,500 IU; vitamin D3, 4,125 IU; vitamin E, 15 IU; vitamin K, 2 mg; thiamine, 1 mg; riboflavin, 8.5 mg; calcium pantothenate, 50 mg; niacin acid, 32.5 mg; pyridoxine, 8 mg; folic acid, 5 mg; vitamin B12, 5 mg; choline chloride, 500 mg; selenium, 0.25 mg; iodine, 3 mg.

The analyzed Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn contents in basal diet were 71.9, 7.2, 32.7, and 26.8 mg/kg, respectively. Except for crude protein and calcium levels, all other values were calculated.

Table 2.

Assayed iron, copper, manganese, and zinc content in the experimental diets (mg/kg).

| Ingredients | CON | ITM1 | TRT2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | 109.2 ± 7.8 (36) | 82.8 ± 6.6 (12) | 80.6 ± 3.3 (12) |

| Copper | 18.6 ± 2.0 (12) | 11.2 ± 1.4 (4) | 11.1 ± 1.4 (4) |

| Manganese | 123.3 ± 5.5 (90) | 64.7 ± 5.9 (30) | 66.4 ± 3.4 (30) |

| Zinc | 113.2 ± 5.4 (90) | 58.7 ± 2.9 (30) | 57.8 ± 3.5 (30) |

The values in brackets indicate the supplementation of trace minerals added to each group.

Abbreviations: CON, basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at commercial levels; ITM, a basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at 1/3 commercial levels; TRT, a basal diet + proteinated trace minerals at 1/3 commercial levels.

Inorganic trace minerals provided by Zhejiang Weimeng Feed Technology Co., Ltd.

Organic source, proteinated trace minerals (Bioplex Poultry Pack, Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, KY).

Performance and Eggshell Quality

During the experiment, eggs were collected at 16:00 p.m. every day. The number of eggs produced per day on a repeating basis (including eggs with a soft shell, broken shell, and different shape, which were being treated as unqualified eggs) were recorded to calculate egg loss (the number of unqualified eggs per replication divided by the total number of eggs per replication) and egg production (the total number of eggs per replication divided by the number of experimental days [56] and divided by the number of hens per replication [15]).

Per replication, 2 eggs were collected randomly at the end of the 8th wk. The eggshell strength was assessed by using a digital egg tester (DET-6000, Nabel Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), and eggshell thickness was measured using an eggshell thickness gauge (ESTG-1, Orka Food Technology Ltd., Ramat Hasharon, Israel) at 3 points (sharp end, blunt end, and the equator) after removing the eggshell membrane and estimated by the average of 3 points from each egg (Li et al., 2018a).

Eggshell Ultrastructure

Per replication, one egg was collected randomly at the end of the 8th wk. The eggs were broken, and the eggshell was washed with distilled water and then dried at room temperature for 48 h (Stefanello et al., 2014). Two samples of the eggshell of each egg (0.5–1.0 cm2) were prepared for scanning electron microscope analysis (model TM 1000, HITACHI Corp., Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan). One sample was used for analysis of the cross section of the eggshell, and the other sample was used for assessment of the external surface. Before scanning, the eggshell samples were immobilized to the aluminum support and sprayed with gold powder (Li et al., 2018a). For the cross-sectional analysis, scanned images were obtained for each sample using 300× magnification. The palisade layer thickness (μm), mammillary button thickness, and total thickness (palisade + mammillary) were measured according to the method of Stefanello et al. (2014), and the percentage of palisade layer thickness and mammillary button thickness were obtained by calculating the ratio of the thickness of each layer to the total thickness measured (Stefanello et al., 2014). The width of the mammillary cones in the cross section of the eggshell was measured using the scanning electron microscope ruler according to the model of Dunn et al., 2012. The scanned images of the eggshell external surface were obtained for each sample using 200× magnification.

Hormone Levels and Enzyme Activities in Serum

At the end of the 8th wk, 2 birds from each replication were randomly selected for collecting blood samples. Blood samples (approximately 5 mL) were collected from the wing vein of the bird in individual vacuum blood collection tubes. Serum was obtained by centrifuging the clotted blood at 2500× g at 4°C for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C for later determination of metabolites and enzyme activities. Serum samples were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent antibody assay kits (Jiangsu Mei Biao in Technology Co., Ltd., Yancheng, Jiangsu, China).

Statistical Analyses

The replication unit served as the experimental unit for performance variables, the individual hens (2 hens per replication) served as the experimental unit for hormone levels and enzyme activities in serum, and the individual eggs (2 eggs per replication) served as the experimental unit for eggshell quality. The data obtained on performance, eggshell quality, hormone levels, and enzyme activities in serum were analyzed using IBM-SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS. Inc., Chicago). Normally, distributed data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and nonnormally distributed data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The level of significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Compared with the CON group, the low inclusion levels of trace minerals, regardless of inorganic or organic sources, did not alter eggshell thickness (P > 0.05). Compared with the CON group, the TRT group did not compromise egg production and eggshell strength (P > 0.05) and even reduce egg loss (P < 0.05). On the contrary, hens fed with ITM showed lower (P < 0.05) egg production and eggshell strength and increased (P < 0.05) egg loss compared with those fed with CON (Table 3). The results of eggshell thickness are supported by several studies (Swiatkiewicz and Koreleski, 2008, Stefanello et al., 2014; Li et al., 2018a), which did not observe an effect of different sources of dietary trace mineral supplementation on eggshell thickness. Swiatkiewicz and Koreleski (2008) also reported that substitution of organic amino acid complexes of Zn and Mn for inorganic oxides increased eggshell breaking strength in the late phase of the laying cycle. In another study, the eggshell strength of laying hens aged 68 wk also improved when chelated Zn-Cu-Mn was used to replace inorganic sulfates completely(Manangi et al., 2015).

Table 3.

Effect of experimental diets on productive performance and eggshell quality of laying hens during the late laying period (52- to 60-week-old).

| Items | Treatments1 |

SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ITM | TRT | |||

| Egg production (%)2 | 78.91a | 76.08b | 78.68a | 0.01 | <0.05 |

| Egg loss (%)2 | 2.07b | 2.51a | 1.91c | 0.01 | <0.05 |

| Shell strength (N)3 | 35.89a | 24.87b | 35.34a | 1.50 | <0.05 |

| Eggshell thickness (mm)3 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.532 |

a,bValues with different superscripts in the same row are different (P < 0.05).

CON (control), basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at commercial level; ITM, basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at 1/3 commercial level; TRT, basal diet + proteinated trace minerals at 1/3 commercial level.

Results are the mean and SEM of 9 replications per treatment.

Results are the mean and SEM of 18 eggs per treatment.

Organic trace minerals are stable and not ionized before absorption; after entering the digestive tract, they can avoid the precipitation or adsorption by precipitants (such as phytic acid, phosphoric acid, and oxalic acid) in the intestinal tract (Bagley et al., 1971, Liu et al., 2014). What is more, proteinated minerals are transported and absorbed as amino acids; therefore, the main benefit of using organic minerals is attributed to higher absorption as they use the same absorption pathways of the amino acids to which they are bound, decreasing the competition for inorganic trace mineral–binding sites and thus reducing the excretion of the same minerals through bile and feces (Bagley et al., 1971, Stefanello et al., 2014, Singh et al., 2015). In this study, the increased absorption of low inclusion levels of organic trace minerals had a positive effect on performance and eggshell quality. On the contrary, a decrease in eggshell strength was observed when using low inclusion levels of inorganic trace minerals, which may also be related to the increase in egg loss. Interestingly, in this study, hens fed with organic trace minerals showed remarkable increase in eggshell strength but not eggshell thickness when compared with those fed with the same level of inorganic minerals. Traditionally, the evaluation of eggshell strength has focused on the measurement of eggshell thickness. As thickness did not correlate to strength in this study, it was important to examine the mineral source effects on the eggshell ultrastructure.

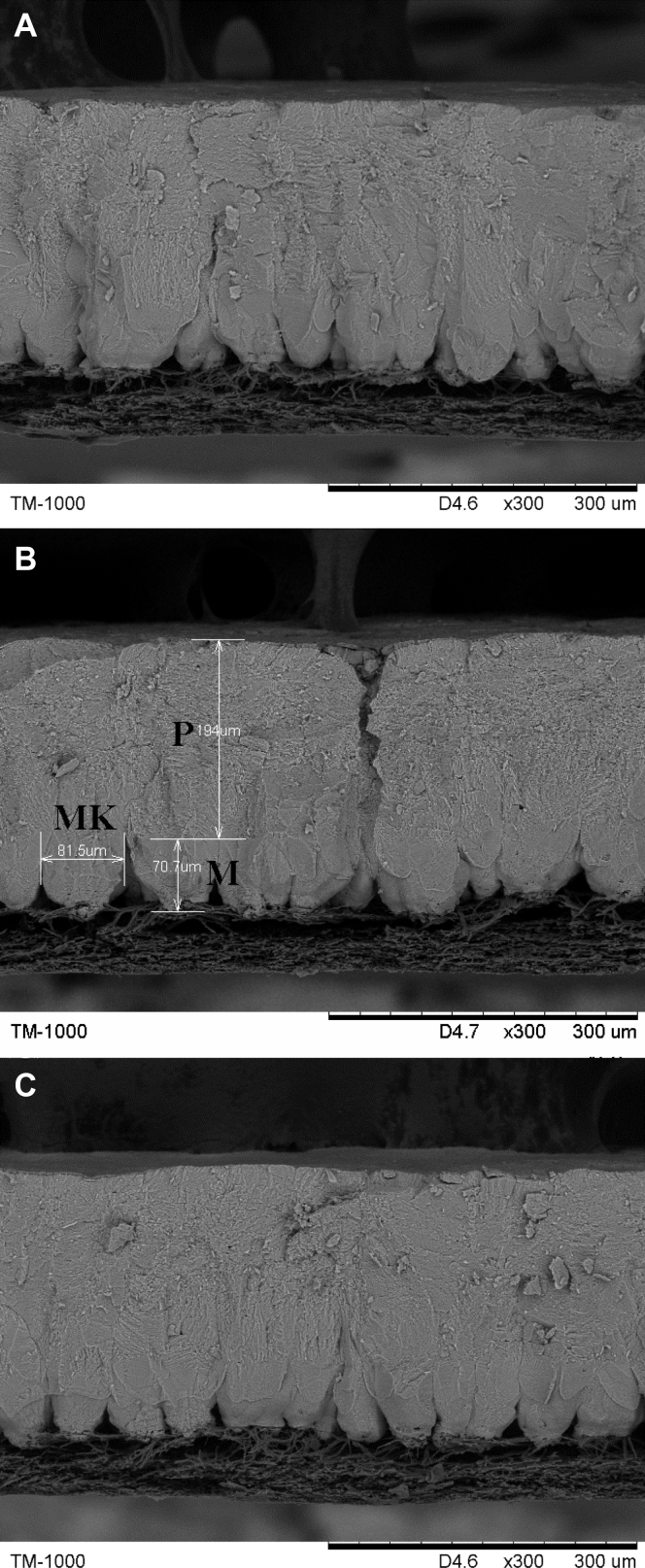

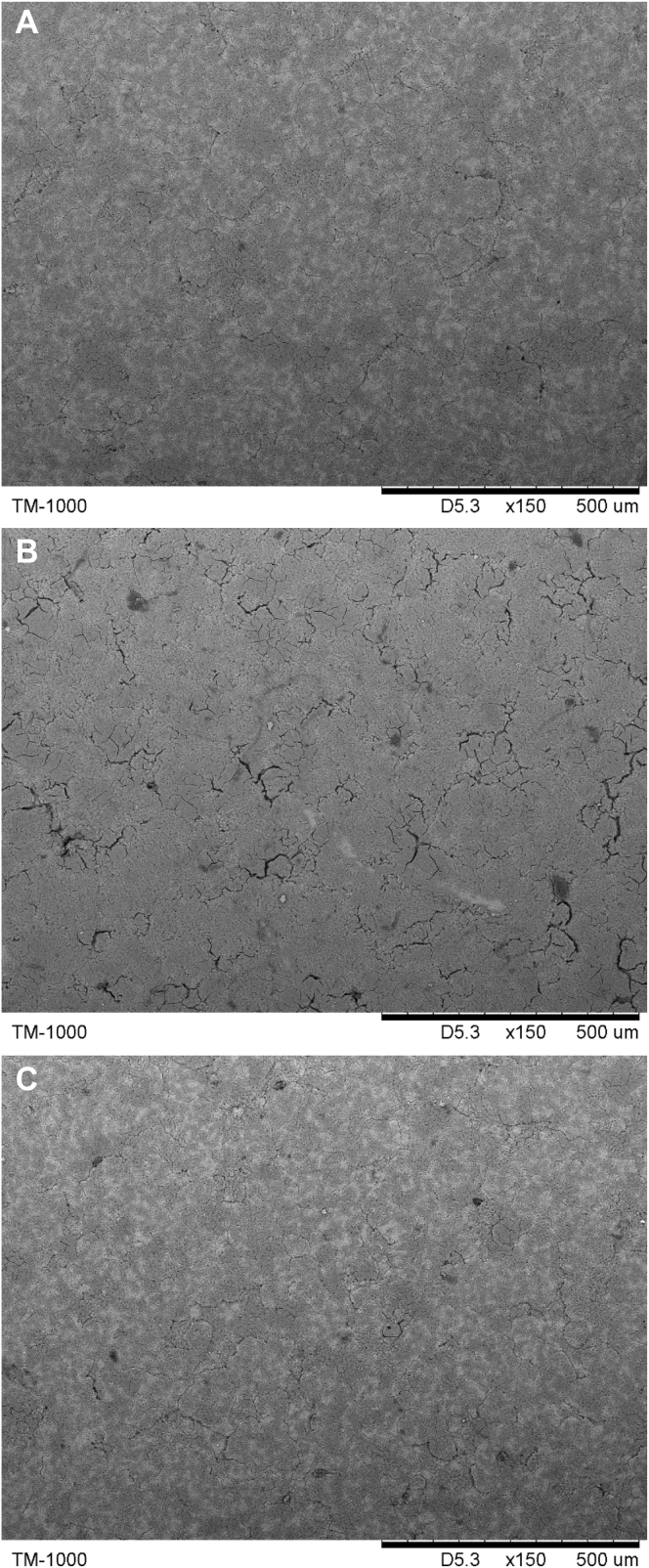

Measurements of the eggshell ultrastructure of laying hens at 60 wk of age by scanning electron microscopy are depicted in Table 4, Figure 1, and Figure 2. Supplementation of Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn in commercial diets of laying hens, regardless of the inorganic or organic source or different levels of addition, did not affect (P > 0.05) the thickness of the mammillary layer of the eggshell, which is consistent with the study of Stefanello et al (2014). Compared with the CON group, the TRT group showed no adverse effects on the eggshell ultrastructure (P > 0.05), but the ITM group showed remarkable decrease in (P < 0.05) palisade layer thickness, total thickness, and the percentage of palisade layer thickness and increase in (P < 0.05) the percentage of mammillary layer thickness. What is more, the TRT group showed smaller mammillary knobs (P < 0.05) than the CON and ITM groups. The results were consistent with previous research results (Stefanello et al., 2014, Li et al., 2018a), which have observed that the ultrastructure of eggshells can be improved by supplementation with organic trace minerals below commercial levels. The thickness of the palisade layer and the organization of the calcite crystals in the layer are the main factors affecting eggshell breaking strength (Stefanello et al., 2014). Thus, the increased palisade layer, decreased mammillary buttons, and the regular arrangement of calcified columns are important for eggshell strength. In addition, the ITM group showed obvious cracks on the outer surface of the eggshell, as illustrated in Figure 2B. The adequate supplementation of Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn can improve eggshell quality by improving the ultrastructure of the eggshell, especially when protein chelates are supplied. Improving the eggshell quality can reduce egg loss and improve economic efficiency, which is very important in the commercial egg industry. The use of low inclusion levels of organic trace minerals can achieve better results in this respect.

Table 4.

Effect of experimental diets on the eggshell ultrastructure of laying hens during the late laying period (52- to 60-week-old).

| Items2 | Treatments1 |

SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ITM | TRT | |||

| Palisade layer (μm) | 241.42a | 217.58b | 241.10a | 4.75 | <0.05 |

| Mammillary layer (μm) | 52.66 | 58.25 | 52.73 | 2.30 | 0.108 |

| Total thickness (μm) | 294.08a | 275.83b | 293.83a | 4.80 | <0.05 |

| Palisade layer (%) | 82.02a | 78.97b | 82.22a | 0.80 | <0.05 |

| Mammillary layer (%) | 17.98b | 21.03a | 17.78b | 0.80 | <0.05 |

| Mammillary knob width (μm) | 89.89a | 88.91a | 61.53b | 4.57 | <0.05 |

a,bValues with different superscripts in the same row are different (P < 0.05).

CON (control), basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at commercial level; ITM, basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at 1/3 commercial level; TRT, basal diet + proteinated trace minerals at 1/3 commercial level.

Data are mean and SEM, calculated for 18 scanning electron microscope photographs of 9 eggs per treatment.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy of the eggshell cross section of laying hens at 60 wk of age. Palisade layer (P), mammillary layer (M), and vertical view of the mammillary knobs (MK). (A) The cross section with dietary inorganic trace mineral supplementation at commercial levels. (B) The cross section with dietary inorganic trace mineral supplementation at 1/3 commercial levels. (C) The cross section with dietary organic trace mineral supplementation at 1/3 commercial levels. Scale bar: 300 μm.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy of the eggshell external surface of laying hens at 60 wk of age. (A) The external surface with dietary inorganic trace mineral supplementation at commercial levels. (B) The external surface with dietary inorganic trace mineral supplementation at 1/3 commercial levels. (C) The external surface with dietary organic trace mineral supplementation at 1/3 commercial levels. Scale bar: 500 μm.

Trace minerals are essential for the growth of bone and reproduction within the animal (Park et al., 2004, Aschner and Aschner, 2005, Kim et al., 2008, Han, 2011). Estrogen (E) is a steroid hormone that is mainly produced by the ovaries, exerts its biological effects by binding to receptors (estrogen receptor-α and estrogen receptor-β), and affects the body's metabolism (Yang, et al., 2016). Maintaining normal E levels is essential for laying hens because it is involved in maintaining normal function of the reproductive organs and is essential for bone and egg formation (Yang et al., 2016, Li et al., 2018b). Estrogen levels are associated with Fe homeostasis, and too much or too little Fe in animals can have adverse effects (Yang et al., 2016). Diets supplemented with ITM reduced (P < 0.05) the E level and the luteinizing hormone level of laying hens, possibly due to the low trace mineral content deposited in the body (Table 5). The reduction in these 2 levels of hormones may be the main reason for the decline in egg production of laying hens in the ITM group. However, more detailed mechanism remains to be explored. The TRT group did not show change in levels of (P > 0.05) E, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, or progesterone in serum, compared with the CON group.

Table 5.

Effect of experimental diets on hormone levels and enzyme activities in serum of laying hens during the late laying period (52- to 60-week-old).

| Items2 | Treatments1 |

SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ITM | TRT | |||

| E (pmol/L) | 16.68a | 12.31b | 15.8a | 0.67 | <0.05 |

| LH (ng/L) | 53.86a | 41.29b | 50.57a | 2.07 | <0.05 |

| FSH (U/L) | 8.83 | 8.98 | 8.64 | 0.31 | 0.587 |

| PROG (nmol/L) | 2.76 | 2.69 | 2.82 | 0.11 | 0.685 |

| LOX (IU/L) | 45.59 | 49.32 | 45.94 | 1.97 | 0.342 |

| GAG (ng/L) | 330.31a | 308.91b | 328.55a | 5.19 | <0.05 |

| CA (U/L) | 402.98a | 380.13b | 404.15a | 6.95 | <0.05 |

a,bValues with different superscripts in the same row are different (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: CA, carbonic anhydrase; E, estrogen; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; LH, luteinizing hormone; LOX, lysyl oxidase; PROG, progesterone.

CON (control), basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at commercial level; ITM, basal diet + inorganic trace minerals at 1/3 commercial level; TRT, basal diet + proteinated trace minerals at 1/3 commercial level.

Data are mean and SEM, calculated for 18 replications per treatment.

During the entire process after ovulation, eggs are immersed in uterine fluid and pass through various parts of the fallopian tube. The uterine fluid is a cell-free environment containing all the organic and inorganic precursors needed to form the eggshell. Among them, organic components are secreted at specific times and locations of the fallopian tubes and are incorporated into specific substructure regions of the eggshell. The inorganic component of eggshell mineralization requires the continuous supply of high amounts of calcium and carbonate ions in uterine fluid, which are obtained from the bloodstream by transepithelial transport of uterine gland cells (Jonchère et al., 2012, Stefanello et al., 2014). Cu, Mn, and Zn act as promoters and components of important enzymes in the formation of eggshells such as lysyl oxidase, glycosyltransferase, and carbonic anhydrase (CA) and participate in the formation of eggshells (Akagawa et al., 1999, Nys et al., 2004, Xiao et al., 2014). Lysyl oxidase is a Cu-containing amine oxidase, which is crucial in the formation of the eggshell membrane as it is involved in conversion of lysine to 2 components of the eggshell membrane, cross-linked desmosine and isodesmosine (Akagawa et al., 1999, Bai et al., 2017). Its activity decreases with the deficiency of Cu, which can lead to abnormal eggshell membrane formation (Baumgartner et al., 1978, Akagawa et al., 1999). In our study, low inclusion of trace minerals, regardless of the inorganic or organic source, did not alter (P > 0.05) the activity of lysyl oxidase; it may be due to the fact that the addition of Cu has already met the needs of laying hens, and the microreduction is not enough to cause a deficiency of Cu in the laying hens during the late laying period. Glycosyltransferase contributes to formation of nucleation sites and regulates the growth and orientation of the calcite crystal during eggshell formation, which is activated by Mn (Xiao et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2017b). Glycosyltransferase plays an important role in the synthesis of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) (Venkatesan et al., 2004), and higher GAG concentration contributes to improving eggshell breaking strength (Xiao et al., 2014). The result of GAG in the TRT group was similar to that in the CON group (P > 0.05), whereas the ITM group showed reduced (P < 0.05) GAG concentration in serum compared with the CON group. Carbonic anhydrase is a Zn-containing enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of CO2 to form the precursor substance HCO3 of eggshell calcium carbonate during the formation of eggshell crystals and causes calcium carbonate to deposit on the outer membrane (Brionne et al., 2014, Rodríguez-navarro et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2017a). Previous studies have reported that the inhibition of CA activity results in a severe decrease in shell quality, resulting in thin-shell or shell-less eggs (Lundholm, 1990, Zhang et al., 2017a). Our study found that there was no obvious difference (P > 0.05) in CA activity in serum between the TRT and CON groups, but the ITM group showed decrease (P < 0.05) in CA activity in serum when compared with the CON and TRT groups. It was consistent with the study of Zhang et al (2017a), which showed the organic Zn was more effective than the inorganic source in enhancing the CA activity in plasma. Furthermore, almost all the hormone levels and enzyme activities in serum in the TRT group were similar to those in the CON group, whereas the ITM group showed decrease in most of them. This may be the main reason for the decrease of egg production rate and the deterioration of eggshell quality in the ITM group.

In conclusion, hens fed with low inclusion levels of organic trace minerals had higher hormone levels, enzyme activities, and a better eggshell ultrastructure, which likely allowed better performance and eggshell strength than those fed with identical levels of inorganic minerals, probably due to higher bioavailability of organic trace minerals.

Acknowledgments

The experimentation conformed to the ethical norms. The use of experimental animals, the procedures for animal management, and the collection of animal blood and tissues in this research were carried out according to the Institutional Animal Care and the Chinese Guidelines for Animal Welfare and approved by Animal Research Ethics Board of Zhejiang University.

References

- Ahmed A.M.H., Rodriguez-navarro A.B., Vidal M.L., Gautron J., Garcia-ruiz J.M., Nys Y. Changes in eggshell mechanical properties, crystallographic texture and in matrix proteins induced by moult in hens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2005;46:268–279. doi: 10.1080/00071660500065425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagawa M., Wako Y., Suyama K. Lysyl oxidase coupled with catalase in egg shell membrane. Biochim. Biophys. ACTA. 1999;1434:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksu T., Ozsoy B., Aksu D.S., Yoruk M.A., Gul M. The effects of lower levels of organically complexed zinc, copper and manganese in broiler diets on performance, mineral concentration of tibia and mineral excretion. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. 2011;17:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Aschner J.L., Aschner M. Nutritional aspects of manganese homeostasis. Mol. Aspects Med. 2005;26:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadou D., Jiang W., Goldbaum D., Saleem A., Basu K., Pacella M.S., Böhm C.F., Chromik R.R., Hincke M.T., Rodríguez-navarro A.B., Vali H., Wolf S.E., Gray J.J., Bui K.H., Mckee M.D. Nanostructure, osteopontin, and mechanical properties of calcitic avian eggshell. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaar3219. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley D.H., Zapolski E.J., Rubin M., Princiotto J.V. Metabolism and placental transfer of oral and parenteral iron chelates. Clin. Chim. ACTA. 1971;35:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(71)90199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S., Jin G., Li D., Ding X., Wang J., Zhang K., Zeng Q., Ji F., Zhao J. Dietary organic trace minerals level influences eggshell quality and minerals retention in hens. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2017;17:503–515. [Google Scholar]

- Bar A., Hurwitz S. Eggshell quality, medullary bone ash, intestinal calcium and phosphorus absorption, and calcium-binding protein in phosphorus-deficient hens. Poult. Sci. 1984;63:1975–1979. doi: 10.3382/ps.0631975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S., Brown D.J., Salevsky E., Leach R.M. Copper deficiency in the laying hen. J. Nutr. 1978;108:804–811. doi: 10.1093/jn/108.5.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwanger E., Vieira S.L., Angel C.R., Kindlein L., Mayer A.N., Ebbing M.A., Lopes M. Copper requirements of broiler breeder hens. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:2785–2797. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brionne A., Nys Y., Hennequet-antier C., Gautron J. Hen uterine gene expression profiling during eggshell formation reveals putative proteins involved in the supply of minerals or in the shell mineralization process. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn I.C., Rodriguez-navarro A.B., Mcdade K., Schmutz M., Preisinger R., Waddington D., Wilson P.W., Bain M.M. Genetic variation in eggshell crystal size and orientation is large and these traits are correlated with shell thickness and are associated with eggshell matrix protein markers. Anim. Genet. 2012;43:410–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathi M.M., El-dein A.Z., El-safty S.A., Radwan L.M. Using scanning electron microscopy to detect the ultrastructural variations in eggshell quality of Fayoumi and Dandarawi chicken breeds. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2007;6:236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi M.M., El-dlebshany A.E., El-deen M.B., Radwan L.M., Rayan G.N. Effect of long-term selection for egg production on eggshell quality of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) Poult. Sci. 2016;95:2570–2575. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J.I.M., Murakami A.E., Sakamoto M.I., Souza L.M.G., Malaguido A., Martins E.N. Effects of organic mineral dietary supplementation on production performance and egg quality of white layers. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2008;10:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Goodsonwilliams R., Roland D.A., Mcguire J.A. Eggshell pimpling in young hens as influenced by dietary vitamin-D3. Poult. Sci. 1987;66:1980–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Han O. Molecular mechanism of intestinal iron absorption. Review. 2011;3:103–109. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00043d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hincke M.T., Nys Y., Gautron J., Mann K., Rodriguez-navarro A.B., Mckee M.D. The eggshell: structure, composition and mineralization. Front. Biosci. 2012;17:1266–1280. doi: 10.2741/3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonchère V., Brionne A., Gautron J., Nys Y. Identification of uterine ion transporters for mineralisation precursors of the avian eggshell. BMC Physiol. 2012;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.H., Yoo J.S., Park J.C., Jung H.J., Cho J.H., Chen Y.J., Kim H.J., Kim I.C., Lee S.J., Kim I.H. Effects of copper and zinc sources on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, carcass traits and meat characteristics in finishing pigs. Korean J. Food Sci. 2008;28:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li L.L., Zhang N.N., Gong Y.J., Zhou M.Y., Zhan H.Q., Zou X.T. Effects of dietary Mn-methionine supplementation on the egg quality of laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:247–254. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Zhao X., Wang S., Zhou Z. Letrozole induced low estrogen levels affected the expressions of duodenal and renal calcium-processing gene in laying hens. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 2018;255:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Ma Y.L., Zhao J.M., Vazquez-anon M., Stein H.H. Digestibility and retention of zinc, copper, manganese, iron, calcium, and phosphorus in pigs fed diets containing inorganic or organic minerals. J. Anim. Sci. 2014;92:3407–3415. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundholm C.E. The eggshell thinning action of acetazolamide - relation to the binding of Ca2+ and carbonic-anhydrase activity of the shell gland homogenate. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C. 1990;95:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mabe I., Rapp C., Bain M.M., Nys Y. Supplementation of a corn-soybean meal diet with manganese, copper, and zinc from organic or inorganic sources improves eggshell quality in aged laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2003;82:1903–1913. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.12.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manangi M.K., Vazques-anon M., Richards J.D., Carter S., Knight C.D. The impact of feeding supplemental chelated trace minerals on shell quality, tibia breaking strength, and immune response in laying hens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2015;24:316–326. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . 9th rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Press; Washington, D. C, USA: 1994. Nutrient Requirements of Poultry. [Google Scholar]

- Neijat M., House J.D., Guenter W., Kebreab E. Calcium and phosphorus dynamics in commercial laying hens housed in conventional or enriched cage systems. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:2383–2396. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nys Y., Gautron J., Garcia-ruiz J.M., Hincke M.T. Avian eggshell mineralization: biochemical and functional characterization of matrix proteins. C. R. Palevol. 2004;3:549–562. [Google Scholar]

- Nys Y., Hincke M.T., Arias J.L., Garcia-ruiz J.M., Solomon S.E. Avian eggshell mineralization. Avian. Poult. Biol. Rev. 1999;10:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Birkhold S.G., Kubena L.F., Nisbet D.J., Ricke S.C. Review on the role of dietary zinc in poultry nutrition, immunity, and reproduction. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004;101:147–163. doi: 10.1385/BTER:101:2:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.A., Sohn S.H. The influence of hen aging on eggshell ultrastructure and shell mineral components. Korean J. Food Sci. 2018;38:1080–1091. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2018.e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons A.H. Structure of the eggshell. Poult. Sci. 1982;61:2013–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Richards J.D., Zhao J., Harrell R.J., Atwell C.A., Dibner J.J. Trace mineral nutrition in poultry and Swine. Asian-Austral. J. Anim. Sci. 2010;23:1527–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-navarro A.B., Marie P., Nys Y., Maxwell T.H., Gautron J. Amorphous calcium carbonate controls avian eggshell mineralization: A new paradigm for understanding rapid eggshell calcification. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;190:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J., Lunam C.A. Ultrastructural analysis of the eggshell: contribution of the individual calcified layers and the cuticle to hatchability and egg viability in broiler breeders. Br. Poult. Sci. 2000;41:584–592. doi: 10.1080/713654975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.K., Ghosh T.K., Haldar S. Effects of methionine chelate- or yeast proteinate-based supplement of copper, iron, manganese and zinc on broiler growth performance, their distribution in the tibia and excretion into the environment. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015;164:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S.E. The eggshell: strength, structure and function. Br. Poult. Sci. 2010;51:52–59. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2010.497296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanello C., Santos T.C., Murakami A.E., Martins E.N., Carneiro T.C. Productive performance, eggshell quality, and eggshell ultrastructure of laying hens fed diets supplemented with organic trace minerals. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:104–113. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiatkiewicz S., Koreleski J. The effect of zinc and manganese source in the diet for laying hens on eggshell and bones quality. Vet. Med. 2008;53:555–563. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China . 2004. Feeding standard of chicken. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan N., Barré L., Benani A., Netter P., Magdalou J., Fournel-gigleux S., Ouzzine M. Stimulation of proteoglycan synthesis by glucuronosyltransferase-I gene delivery: a strategy to promote cartilage repair. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:18087–18092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404504102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn K.W. Incidence, cause, and prevention of egg shell breakage in commercial production. Poult. Sci. 1982;61:2005–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J.F., Wu S.G., Zhang H.J., Yue H.Y., Wang J., Ji F., Qi G.H. Bioefficacy comparison of organic manganese with inorganic manganese for eggshell quality in Hy-Line Brown laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2015;94:1871–1878. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J.F., Zhang Y.N., Wu S.G., Zhang H.J., Yue H.Y., Qi G.H. Manganese supplementation enhances the synthesis of glycosaminoglycan in eggshell membrane: A strategy to improve eggshell quality in laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:380–388. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Xu M.M., Wang J., Xie J.X. Effect of estrogen on iron metabolism in mammals. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2016;68:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.N., Zhang H.J., Wang J., Yue H.Y., Qi X.L., Wu S.G., Qi G.H. Effect of dietary supplementation of organic or inorganic zinc on carbonic anhydrase activity in eggshell formation and quality of aged laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:2176–2183. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.N., Zhang H.J., Wu S.G., Wang J., Qi G.H. Dietary manganese supplementation modulated mechanical and ultrastructural changes during eggshell formation in laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:2699–2707. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]