Abstract

Introduction

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic has become increasingly politicized in the United States (US), political party affiliation of state leaders may contribute to policies affecting the spread of the disease. We examined differences in COVID-19 infection and death rates stratified by governor party affiliation across the 50 US states and the District of Columbia (DC).

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal analysis examining daily COVID-19 incidence and death rates from March 1 through September 30, 2020, for each US state and DC. We fit a Bayesian negative binomial model to estimate adjusted daily risk ratios (RRs) and posterior intervals (PIs) comparing infection and death rates by gubernatorial (mayoral for DC) party affiliation. We adjusted for several state-level variables, including population density, age, race, poverty, and health.

Results

From March to early June 2020, Republican-led states had, on average, lower COVID-19 incidence rates compared to Democratic-led states. However, on June 8, the association reversed, and Republican-led states had higher per capita COVID-19 incidence rates (RR=1.15, 95% PI: 1.02, 1.25). This trend persisted until September 30 (RR=1.26, 95% PI: 0.96, 1.51). For death rates, Republican-led states had lower average rates early in the pandemic, but higher rates from July 13 (RR=1.22, 95% PI: 1.03,1.37) through September 30 (RR=1.74, 95% PI: 1.20, 2.24).

Conclusion

Gubernatorial party affiliation may drive policy decisions that impact COVID-19 infections and deaths across the US. As attitudes toward the pandemic become increasingly polarized, policy decisions should be guided by public health considerations rather than political ideology.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in a global public health crisis. As of October 3, 2020, there have been over 7 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and over 2 million related deaths in the US.1 In response to the pandemic, the governors of all 50 states declared states of emergency. Shortly thereafter, states began enacting policies to help stop the spread of the virus. However, these policies vary and are guided, in part, by decisions from state governors.

Under the 10th Amendment to the US Constitution, which gives states all powers not specifically apportioned to the federal government, state governors have the authority to take action in public health emergencies. For example, earlier this year, nearly all state governors issued stay-at-home executive orders that advised or required residents to shelter in place.2 Two recent studies found that Republican governors, however, were slower to adopt stay-at-home orders, if they did so at all.3,4 Moreover, another study found that Democratic governors had longer durations of stay-at-home orders.5 Further, researchers identified governor Democratic political party affiliation as the most important predictor of state mandates to wear face masks.6

Although recent studies have examined individual state policies, such as mandates to socially distance, wear masks, and close schools and parks,3,4,6–8 multiple policies may act in unison to impact the spread of COVID-19. Additionally, the pandemic response has become increasingly politicized.7,9,10 As such, political affiliation of state leaders, and specifically governors, might best capture the omnibus impact of state policies. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine differences in incidence and death rate trends over time, stratified by governors’ political affiliation among the 50 states and DC.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal analysis examining COVID-19 incidence and death rates from March 1 through September 30, 2020 for the 50 states and DC. Based on prior research,3,4,6,7 we hypothesized that states with Republican governors would have lower incidence and death rates early in the pandemic as many Democratic governors preside over international hubs that served as points of entry for the virus in early 2020.11,12 We also hypothesized that Republican-led states would have higher rates in later months, potentially reflecting policy differences that break along party lines. The Institutional Review Boards at the Medical University of South Carolina and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health deemed this research exempt.

We documented governor party affiliation for each US state; for DC, we used mayoral affiliation. We obtained daily COVID-19 incident case and death data from USAFacts,13 a well-validated source of COVID-19 tracking information, for each county in the US.14,15 We aggregated county data to obtain state-level data. We then adjusted for potential confounders chosen a priori from the US Census Bureau and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.16–18 These included state population size to compute population density, the percentage of state residents aged 65 and older, the percentage of Black and Hispanic residents, the percentage below the federal poverty line, the percentage in poor or fair health, and the number of primary care physicians per 100,000 residents.

Statistical analysis

We fit Bayesian negative binomial models with daily incident cases and deaths for each state as the outcomes. The models included penalized cubic Bsplines for both the fixed and random (state-specific) temporal effects. We included state population as an offset on the log scale. We assigned ridging priors to the spline coefficients.19 We standardized adjustment variables and assigned diffuse normal priors to their coefficients. We assigned a gamma prior to the dispersion parameter. For posterior computation, we developed an efficient Gibbs sampler20,21 and ran the algorithm for 50,000 iterations with a burn-in 10,000 to ensure convergence. Sensitivity analyses demonstrated the model’s robustness to prior specification.

We stratified states by governors’ affiliation and graphed the posterior mean incidence and death rates daily for the reference covariate group, as well as the 95% posterior intervals (PIs). We reported adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% PIs comparing states, with RRs > 1.00 indicating higher rates among Republican-led states. We conducted analyses using R software version 3.6 (R Core Team, 2019).

Results

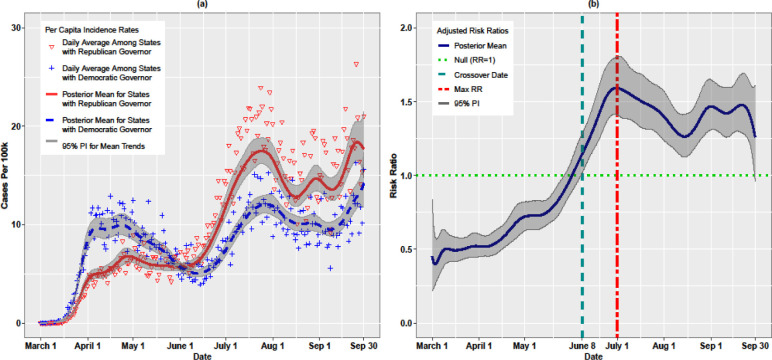

The final sample comprised 10,914 observations (51 states × 214 study days) with 26 Republican-led and 25 Democratic-led states. Figures 1(a) and 1(b) present incidence trends (in cases per 100,000) and adjusted RRs by gubernatorial affiliation. Republican-led states had lower rates from March to early June 2020. However, on June 8, the association reversed (RR=1.15, 95% PI: 1.02, 1.25), indicating that Republican-led states had on average 1.15 times more cases per 100,000 than Democratic-led states. The RRs increased steadily thereafter, achieving a maximum of 1.59 (95% PI: 1.42, 1.73) on July 1. The trends leveled but remained positive through September 29 (RR=1.31, 95% PI: 1.06, 1.52). However, on September 30, risk ratio overlapped the null (RR=1.26, 95% PI: 0.96, 1.51).

Figure 1.

(a) Per capita COVID-19 incidence rates by governor affiliation; (b) adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% posterior intervals (PIs)

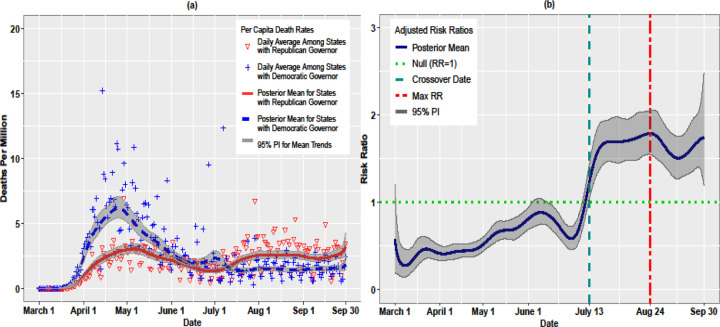

We observed a similar pattern for the death trends shown in Figures 2(a) and 2(b). Republican-led states had lower death rates (per million) early in the pandemic, but the trend reversed on July 13 (RR=1.22, 95% PI: 1.03,1.37). The estimated RRs increased sharply through July 25 (RR=1.69, 95% PI: 1.46, 1.87) and hovered between 1.50 and 2.00 through September 30 (RR=1.74, 95% PI: 1.20, 2.24).

Figure 2.

(a) Per capita COVID-19 death rates by governor affiliation; (b) adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and posterior intervals (PIs)

Discussion

In this longitudinal analysis, we found that Republican-led states had fewer per capita COVID-19 cases and deaths early in the pandemic, but these trends reversed in early June (for cases) and in July (for deaths). These early trends could be explained by high COVID-19 rates among Democratic-led states that are home to initial ports of entry for the virus in early 2020.11,12 However, the subsequent reversal in trends to Republican-led states may reflect policy differences that could have facilitated the spread of the virus.3,4,6–9

For instance, Adolph et al. found that Republican governors were slower to adopt both stay-at-home orders and mandates to wear face masks.3,6 Other studies have shown that Democratic governors were more likely to issue stay-at-home orders with longer durations.4,5 Moreover, decisions by Republican governors in spring 2020 to retract policies, such as the lifting of stay-at-home orders on April 28 in Georgia,22 may have contributed to increased cases and deaths. Thus, governors’ political affiliation might function as an upstream progenitor of multifaceted policies that, in unison, impact the spread of the virus. Although there were notable exceptions among Republican governors in states such as Maryland, Ohio, and Massachusetts, Republican governors were by and large less likely than their Democratic counterparts to enact policies aligned with public health social distancing recommendations.3

There are, however, limitations to this study. We conducted a population-level rather than individual-level analysis. Although we controlled for potential confounders (e.g., population density), the findings could reflect the virus’s spread from urban to rural areas.11,12 Additionally, as with any observational study, we cannot infer causality. Finally, governors are not the only authoritative actor in a state. Future research could explore associations between party affiliation of state or local legislatures, particularly when these differ from governors.

Our findings suggest that governor political party affiliation may differentially impact COVID-19 incidence and death rates. As attitudes toward the pandemic become increasingly polarized,7,9,10 policy decisions should be guided by public health considerations rather than political expedience,23 as the latter may lead to increases in COVID-19 cases and deaths.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Neelon is a part-time employee of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The content of this article does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government. The article represents the views of the authors and not those of the VA or Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Mueller was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01HL141589 (PI: Mueller). The funder had no influence on the study design, implementation, or findings. Dr. Neelon had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Neelon, Dr. Mueller, Dr. Pearce and Dr. Benjamin-Neelon contributed to the concept and design of the study. Dr. Neelon and Mr. Mutiso contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. Dr. Neelon and Benjamin-Neelon drafted the manuscript, and all Dr. Mueller, Dr. Pearce, and Mr. Mutiso provided critical revisions. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:Dr. Mueller was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01HL141589 (PI: Mueller). The funder had no influence on the study’s design, implementation, or findings.

Financial Disclosure: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this manuscript.

References

- 1.CDC COVID Data Tracker: United States Laboratory Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html#testing. Published 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 2.Gostin LO, Wiley LF. Governmental Public Health Powers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stay-at-home Orders, Business Closures, and Travel Restrictions. Jama. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adolph C, Amano K, Bang-Jensen B, Fullman N, Wilkerson J. Pandemic Politics: Timing State-Level Social Distancing Responses to COVID-19. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baccini LB, A. Explaining governors’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. IZA Discussion Paper No 13137. 20202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosnik LR, Bellas A. Drivers of COVID-19 Stay at Home Orders: Epidemiologic, Economic, or Political Concerns? Econ Disaster Clim Chang. 2020:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adolph C, Amano K, Bang-Jensen B, et al. Governor partisanship explains the adoption of statewide mandates to wear face coverings. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2008.2031.20185371. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman G, Kim S, Rexer JM, Thirumurthy H. Political partisanship influences behavioral responses to governors’ recommendations for COVID-19 prevention in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020;117(39):24144–24153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matzinger P, Skinner J. Strong impact of closing schools, closing bars and wearing masks during the Covid-19 pandemic: results from a simple and revealing analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2009.2026.20202457. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen SR, Pilling EB, Eyring JB, Dickerson G, Sloan CD, Magnusson BM. Political and personal reactions to COVID-19 during initial weeks of social distancing in the United States. PloS one. 2020;15(9):e0239693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang J, Chen E, Lerman K, Ferrara E. Political Polarization Drives Online Conversations About COVID-19 in the United States. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul R, Arif AA, Adeyemi O, Ghosh S, Han D. Progression of COVID-19 From Urban to Rural Areas in the United States: A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Prevalence Rates. J Rural Health. 2020;36(4):591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Liu Y, Struthers J, Lian M. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of COVID-19 Epidemic in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.USAFacts. US Coronavirus Cases and Deaths. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/. Published 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 14.Wang G, Gu Z, Li X, et al. Comparing and Integrating US COVID-19 Data from Multiple Sources with Anomaly Detection and Repairing. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JP. Comparison of COVID-19 case and death counts in the United States reported by four online trackers: January 22-May 31, 2020. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2006.2020.20135764. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau USC. County Population Totals: 2010–2019. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-total.html. Published 2019. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 17.Foundation RWJ. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps: Rankings Data & Documentation. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/rankings-data-documentation. Published 2020. Accessed August 8, 2020.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/ Geospatial Research A, and Services Program. Social Vulnerability Index 2018 Database US. https://svi.cdc.gov/data-and-tools-download.html. Published 2018. Accessed September 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kneib T, Konrath S, Fahrmeir L. High dimensional structured additive regression models: Bayesian regularization, smoothing and predictive performance. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics). 2011;60(1): 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pillow JWS, J. Fully Bayesian inference for neural models with negative-binomial spiking. 2012:1898–1906. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dadaneh SZ, Zhou M, Qian X. Bayesian negative binomial regression for differential expression with confounding factors. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(19):3349–3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Each State’s COVID-19 Reopening and Reclosing Plans and Mask Requirements https://www.nashp.org/governors-prioritize-health-for-all/. Published 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020, 2020.

- 23.Guest JL, Del Rio C, Sanchez T. The Three Steps Needed to End the COVID-19 Pandemic: Bold Public Health Leadership, Rapid Innovations, and Courageous Political Will. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]