Abstract

The reactivities of phosphanylphosphinidene complexes [(DippN)2W(Cl)(η2-P–PtBu2)]− (1), [(pTol3P)2Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (2), and [(dppe)Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (3) toward dihaloalkanes and methyl iodide were investigated. The reactions of the anionic tungsten complex (1) with stochiometric Br(CH2)nBr (n = 3, 4, 6) led to the formation of neutral complexes with a tBu2PP(CH2)3Br ligand or neutral dinuclear complexes with unusual tetradentate tBu2PP(CH2)nPPtBu2 ligands (n = 4, 6). The methylation of platinum complexes 2 and 3 with MeI yielded neutral or cationic complexes bearing side-on coordinated tBu2P–P-Me moieties. The reaction of 2 with I(CH2)2I gave a platinum complex with a tBu2P—P—I ligand. When the same dihaloalkane was reacted with 3, the P—P bond in the phosphanylphosphinidene ligand was cleaved to yield tBu2PI, phosphorus polymers, [(dppe)PtI2] and C2H4. Furthermore, the reaction of 3 with Br(CH2)2Br yielded dinuclear complex bearing a tetraphosphorus tBu2PPPPtBu2 ligand in the coordination sphere of the platinum. The molecular structures of the isolated products were established in the solid state and in solution by single-crystal X-ray diffraction and NMR spectroscopy. DFT studies indicated that the polyphosphorus ligands in the obtained complexes possess structures similar to free phosphenium cations tBu2P+=P−R (R = Me, I) or (tBu2P+=P)2.

Short abstract

The phosphanylphosphinidene complexes of tungsten and platinum as building blocks for syntheses of polydentate phosphorus ligands.

1. Introduction

The properties of phosphido and phosphinidene complexes of transition metals (TM) as synthetic tools in organic and inorganic chemistry have recently been intensely studied.1 Formally, phosphinidene complexes can be divided into two classes: electrophilic, which are often very reactive transient species2−6 except for the stable phosphinidene complexes of cobalt and vanadium described by Carty group,7,8 and nucleophilic, which are generally isolable.5,6,9 It is commonly accepted that the electrophilicity versus nucleophilicity of a phosphinidene complex is primarily determined by the electronic properties of the spectator ligands10–acceptor ligands (especially CO) that result in electrophilic complexes, whereas donor spectator ligands, such as NR and PR3, result in nucleophilic complexes. From this point of view, phosphanylphosphinidene complexes, which we discuss in this paper ([(DippN)2W(Cl)(η2-P–PtBu2)]− (1),11 [(pTol3P)2Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (2),12 and [(dppe)Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (3)13) must be considered nucleophilic species (Scheme 1). Similar nucleophilic phosphanylphosphinidene complexes [(η2-R2PP)Nb{N(Np)(3,5-Me2-C6H3)}3] and [(η2-R2PP)W{N(iPr)(3,5-Me2-C6H3)}3]+ were studied by Cummins group.14,15

Scheme 1. Phosphanylphosphinidene Complexes of W and Pt Used for Reactivity Studies.

The nucleophilicity of these species can also be enhanced by a donor phosphanyl group (PtBu2) in the phosphinidene ligand. It should be stressed that stable phosphanylphosphinidene R2P=P (R = nitrogen-based very bulky group) is singlet and electrophilic.16 Reactivity studies on tBu2P–P=PtBu2(Me)17 and DFT-calculations18 revealed that transient tBu2P–P is also electrophilic. The nucleophilic phosphinidene complexes of early TM have been intensely studied and explored as P–R transfer vehicles to organic or inorganic molecules (phospha-Wittig reactivity). The first report concerned reactions of [(N3N)TaV=PR], N3N = (Me3SiNCH2CH2)3N (κ3-N-chelating ligand) with aldehydes yielding the corresponding phosphenes.19 Phosphinidene ate complex [(PNP)ScIII(=PDmp)·LiBr] can transfer its P-Dmp moiety even to a Cp2Zr-center, resulting in [Cp2ZrIV(=PDmp)(PMe3)]. However, the analogous phosphinidene transfer was not observed for the reaction involving a Cp2Ti-center.20 Similarly, zirconium complexes [Cp*2Zr(PPh)2] and [Cp*2Zr(PPh)3] do not display phospha-Wittig reactivity.21 Otherwise, [Cp2ZrIV(=PDmp)(PMe3)] itself displayed high reactivity toward electrophilic reagents.22 Similarly, [Cp2ZrIV(=PMes*)(PMe3)] showed high phospha-Wittig reactivity and converted aldehydes and ketones into phosphenes. It reacted with CH2Cl2 and CHCl3 yielding the related phosphenes as well.23 Recently, the high reactivity of the phosphido complex [MeNacNacTiIII(Cl)(η2-(Me3Si)P–PR2)] R2 = tBu2 or tBu(Ph) toward acetone, yielding Wittig products R2P–P=C(CH3)2 was established.24 The reactivity of nucleophilic phosphinidene complexes of iron, iridium, and platinum toward electrophilic reagents was briefly studied. Dinuclear complexes [Fe2(η-PR)(η-CO)(CO)2] (R = cHex or Ph) reacted with MeI, yielding related [Fe2{η-P(Me)R}(η-CO)(CO)2]I25,26 and forming new P–C bonds. The reaction of iridium complex [Cp*(PPh3)(=PMes*)] with CH2I2 or CHI3 yielded the related phosphenes.27 The reaction of dinuclear Pt0 complex [Pt(dppe)(μ-PMes)]2 with MeI afforded [Pt(dppe){μ-P(Me)Mes}]22+, which is classically nucleophilic and undergoes protonation, oxidation, and Lewis acid complexation.28 In comparison to phosphinidene TM complexes, the phosphinidene complexes of main group elements are significantly less explored. Since the introduction of stable carbenes, they found a wide application to stabilize low valent compounds of main group elements including phosphinidene group.29−32

The syntheses and properties of phosphanylphosphinidene complexes of TM are one of the main research interests of our group. We have elaborated practical methods for accessing a variety of complexes with R2P–P ligands using R2P–P(SiMe3)Li11,12,33−36 or using tBu2P–P=PtBu2(X) (X = Me or Br)17 as transport vehicles for the tBu2P–P moiety. The reactivity of anionic WVI complex [(DippN)2(Cl)W(η2-tBu2P–P)]− was studied in more detail.11 It was nucleophilic and reacted with electrophilic reagents, such as Ph2PBr, PhPCl2, or MeI, forming new P—P or P—C bonds.34,35 However, the nucleophilicity of this complex is rather low. It yields adducts with Lewis acids such as MCl3 (M = Al or Ga) or Cr(CO)5·THF, but these reactions are clearly reversible.18 Chronologically, the first complexes reported with phosphanylphosphinidene ligands were [(R3P)Pt0(η2-tBu2P=P)].37 They are strongly nucleophilic and differ significantly from phosphanylphosphinidene early TM complexes but their properties remain almost unexplored.25 Herein, we report the reactions of [(DippN)2W(Cl)(η2-P–PtBu2)]− (1), [(pTol3P)2Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (2), and [(dppe)Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (3) with electrophilic dihaloalkanes X(CH2)nX (n = 2–6, X = Br, I) to investigate the effect of carbon chain length on the products as well as advance the field of phosphanylphosphinidene chemistry.

2. Results and Discussion

The reactivity of phosphanylphosphinidene complex 1 toward dihaloalkanes was investigated (Scheme 2). The reaction of 1 with Br(CH2)3Br in a 1:1 molar ratio in DME is very clean and gave only tungsten complexes with tBu2P–P(CH2)3Br (1b) as the ligand and LiX (X = Cl, Br) as main products (Scheme 2A). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture consists of only two pairs of doublets at 40.0/–125.3 ppm and at 36.9/–132.2 ppm, which can be attributed to complexes 1b-Cl and 1b-Br, respectively. These complexes differ only in the presence of chlorido (1b-Cl) or bromido ligands (1b-Br) directly bound to the tungsten atom. Moreover, the 1JPP coupling constants, with values of 375 Hz (1b-Cl) and 381 Hz (1b-Br), indicate that the P—P bond is retained in the newly formed ligand. Furthermore, the signals of 1b-Cl and 1b-Br in 31P{1H} NMR spectra are accompanied by 1JPW satellites (1JP1W = 80 Hz), which confirm that the phosphorus ligand did not leave the coordination sphere of tungsten.

Scheme 2. Reactions of 1 with Dihaloalkanes.

A comparison of the 31P{1H} NMR data of 1b-Cl/Br with the NMR data of parent compound 1 reveals that the doublets attributed to the P(CH2)3Br group in 1b-Cl/Br are strongly upfield shifted compared to those in 1 (−125.3/–132.2 ppm vs 17.7 ppm). Moreover, in the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of 1b-Cl/Br these doublets split into doublets of triplets (2JPH = 12 Hz). On the other hand, the 31P{1H} NMR data of 1b-Cl/Br are similar to those observed for [(DippN)2W(X)(1,2-η-tBu2P–PCH3)] (X= Cl, I) (1a) (44.1/–142.3 ppm and 33.7/–161.2 ppm, for the chloro- and iodo-derivatives, respectively), which were obtained previously by us.35 Crystallization from a pentane solution gave yellow crystals in 48% yield, and the crystals contained 1b-Cl and 1b-Br in a 0.4:0.6 molar ratio according to the integrals of the 31P NMR signals. According to X-ray analysis the crystals were a solid solution of 1b-Cl and 1b-Br occupying the same positions (a kind of static disorder). Furthermore, we reacted 1 with 1,2-dibromoethane in a 1:1 molar ratio in DME, which led to a mixture of polyphosphorus compounds according to 31P{1H} NMR analysis of the reaction solution. The only isolated product was [(ArN)2WX2(dme)] (X = Cl, Br),38 and its structure was confirmed both by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray analysis. Therefore, we assume that the tBu2P–P ligand leaves the coordination sphere of tungsten during this reaction.

The reactivity of 1 toward dihaloalkanes with longer aliphatic chains was also investigated. The progress of the reactions of 1 with Br(CH2)nBr (n = 4, 6) in a 1:1 molar ratio was monitored spectroscopically and revealed the formation of products with 31P{1H} NMR spectra very similar to those of 1b-Cl/Br (see Table 1).

Table 1. 31P{1H} NMR Data of Complexes 1b, 1c, and 1e.

| chemical

shift [ppm] |

coupling constant [Hz] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | (R-)P1 | tBu2P2 | 1JP1P2 | 1JP1W | 1JP2W |

| 1b-Cl | –125.3 | 40.0 | 375 | 80 | 17 |

| 1b-Br | –132.2 | 36.9 | 381 | 80 | 17 |

| 1c-Cl | –122.2 | 40.3 | 378 | 76 | 17 |

| 1c-Br | –129.1 | 37.2 | 383 | 80 | 17 |

| 1e-Cl | –122.1 | 40.5 | 378 | 80 | 18 |

| 1e-Br | –129.0 | 37.4 | 382 | 80 | 18 |

A cursory analysis of the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of the reaction mixtures would suggest the formation of a series of complexes analogous to 1b-Cl/Br. However, isolation of the products of these reactions in the crystalline form and X-ray structural analysis revealed the formation of dinuclear complexes (1c-Cl/Br, 1e-Cl/Br) with unusual tetradentate tBu2P–P(CH2)nP–PtBu2 ligands (Scheme 2B). As a result of halide exchange, these compounds were isolated as mixtures of isostructural chlorido and bromido complexes at a molar ratio of 1.3:0.7 according to the integrals of the 31P NMR signals. The bromido complexes can be easily converted into the corresponding chlorido complexes by the addition of three-fold excess of anhydrous LiCl in DME (Figure S17). In the case of the reaction involving 1,4-dibromobutane, the composition of the reaction mixture changes over time. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture after 0.5 h consists of only two sets of doublets, which can be attributed to 1c-Cl and 1c-Br. After prolonged stirring at room temperature, new resonances for 1d appeared (δ 42.3 ppm (d, tBu2P); −37.3 (d, P (CH2)4); 1JPP = 203 Hz), and this was accompanied by a decrease in the intensities of the signals of 1c-Cl/Br. After 3 days, a high conversion of 1c-Cl/Br into 1d was observed. Furthermore, from this reaction mixture a significant amount of crystals of [(ArN)2WX2(dme)] (X = Cl, Br) was isolated. In the first stage of this reaction, dinuclear complexes 1c-Cl/Br are likely formed (Scheme 2C, n = 4). Next, 1c-Cl/Br reacts with the remaining Br(CH2)4Br, yielding diphosphane 1d consisting of a phospholane group and [(ArN)2WX2(dme)] (X = Cl, Br) (Scheme 2C). This type of reactivity is reminiscent of the reaction of nucleophilic phosphinidene zirconium complex [Cp2Zr=PMes*(PMe3)] with 1,2-dichloroxylene, which led to the formation of phospholane C6H4(CH2)2PMes*.23 We did not observe the formation of the analogous diphosphanes with cyclic substituents from the reaction of equimolar amounts of 1 with Br(CH2)nBr (n = 3, 6). We suspect that the formation of 1d, containing a five-member phospholane ring, is thermodynamically favored. To verify this hypothesis, we calculated the ΔG° value for simplified ring-closing reactions: tBu2P–P(H)(CH2)nBr → tBu2P–P(CH2)n + HBr (n = 3–6) (see the SI for details). Indeed, the lowest and only negative value of ΔG° was found for reaction yielding 1d. Notably, reactions with a 2-fold excess of 1 relative to Br(CH2)nBr (n = 4, 6) gave the same dinuclear tungsten complexes as reactions with equimolar amounts of the substrates. Interestingly, the reaction of 1,3-dibromopropane even with excess 1 did not lead to a complex with tBu2P–P(CH2)3P–PtBu2 ligand. The space-filling model of 1c-Cl/Br, which contains four carbon atoms in the aliphatic chain linking the two P–PtBu2 groups (Figure S2), reveals that this complex is very crowded. Therefore, the formation of analogous complexes with less than four carbon atoms in the aliphatic chain is not favored because of the steric effects of the bulky imido ligands.

The isolation of complexes 1b, 1c, and 1e in the crystalline form allowed us to discuss their solid-state structures in detail. The X-ray structures of 1b and 1c are presented in Figures 1 and 2, whereas the molecular structure of 1e is depicted in Figure S1. Complex 1b differs from complexes 1c and 1e in the number of metal centers and in the structure of the phosphorus ligands. In the solid-state structure of 1b, both phosphorus atoms of the tBu2P–P(CH2)3Br ligand coordinate to the tungsten atom. Unlike 1b, where the propane chain is terminated by a bromine atom, in compounds 1c and 1e the aliphatic chain is terminated by a second tBu2P–P group. The tetradentate tBu2P–P(CH2)nP–PtBu2 (n = 4, 6) ligands in 1c and 1e are side-on coordinated to two tungsten centers. Despite these differences, complexes 1b, 1c, and 1e exhibit many structural similarities. All the mentioned complexes feature pentacoordinated tungsten atoms. Furthermore, the P1—P2, P1—W1, and P2—W1 distances are very similar with values in ranges of 2.150(4)–2.168(2) Å, 2.506(1)–2.516(2) Å, and 2.540(2)–2.583(2) Å, respectively. The P1—P2 bonds in 1b, 1c, and 1e are longer than the corresponding distance in parent compound 1 (2.106(2) Å); however, they are still shorter than the sum of the single-bond covalent radii for P atoms (2.22 Å).39 Furthermore, the P1—W1 bond distances in 1b, 1c, and 1e are significantly longer than that in 1 (2.406(1) Å), whereas the P2—W2 bond lengths are comparable to that observed in phosphanylphosphinidene complex 1 (2.571(1) Å). In comparison to 1b, 1c, and 1e, tungsten complexes possessing RP–PR′R″ ligand and PPW metallocycle such as [Cp(CO)2W{P(tBu)−P(H)tBu}], and [Cp(CO)2W{P(Cl)−P(Ph)N(SiMe3)2}] exhibit slightly longer P1—W1 distances (2.572(2)–2.576(3) Å) and significantly shorter P2—W1 bond lengths (2.335(2)–2.4209(9) Å).40,41 Interestingly, all the P1 atoms show pyramidal geometries (sum of angles ΣP1 284.1–291.9°), and the P2 atoms are all tetrahedral; however, neglecting the P2—W1 bond, the tBu2P phosphanyl groups exhibit a high degree of planarity (ΣP2 338.5°–341.7°). The torsion angles of (CH2)C1—P1—P2—C4(tBu) are in the range from −17.0(6)° to 12.8(3)° and indicate the syn-periplanar orientation of the tBu group and the CH2 moiety directly bound to the P1 atom; moreover, it points to the presence of a lone pair of electrons on the P1 atom. The analogous ligand geometry was previously observed by us for the methylated phosphanylphosphinidene group in [(DippN)2W(X)(1,2-η-tBu2P–PCH3)] (X = Cl, I) (1a).35

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of complex 1b. Displacement ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—W1 2.508(2), P2—W1 2.583(2), P1—P2 2.155(2), C1—P1 1.869(4), ΣP1 291.9, ΣP2 338.5 (neglecting the P2—W1 bond), C1—P1—P2 113.4(2), C1—P1—P2—C4 7.8(3).

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of complex 1c. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—W1 2.506(1), P2—W1 2.580(2), P1—P2 2.168(2), C1—P1 1.874(5), ΣP1 284.6, ΣP2 340.4 (neglecting the P2—W1 bond), C1—P1—P2 110.3(2), C1—P1—P2—C7 12.8(3). Atoms labeled with primes are related by symmetry code (1-x, 1-y, 1-z), i.e., symmetry center.

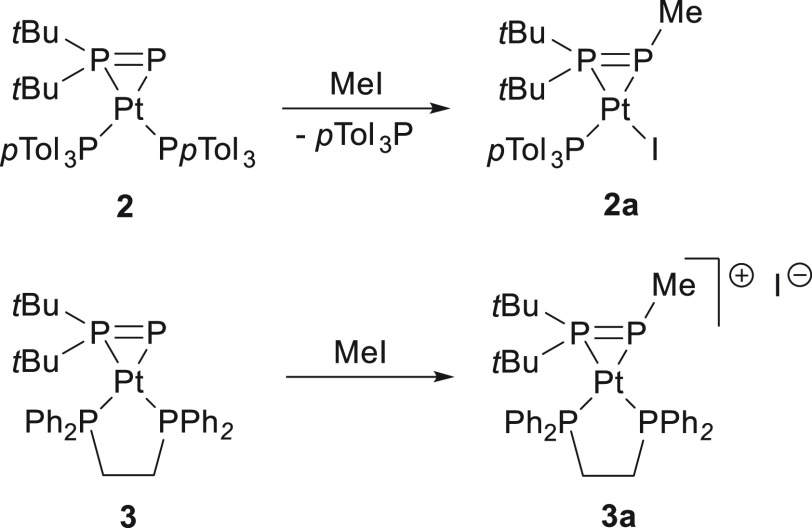

In the second part of our study, we investigated the reactivity of platinum phosphanylphosphinidene complexes 2 and 3 toward haloalkanes. The methylation of 2 and 3 by MeI afforded complexes 2a and 3a, respectively, bearing tBu2P–PMe ligands (Scheme 3). In the case of the reaction of 2 with MeI, strong signals of free pTol3P and resonances of 2a were observed in the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of the reaction mixture. This suggests a replacement of pTol3P with an iodido ligand in the coordination sphere of platinum. Because of the chelating nature of dppe, such ligand exchange was not observed in the reaction involving 3, and only cationic complex 3a was formed. Complex 2a was isolated in its crystalline form from a toluene solution at low temperature in 49% yield. Because of its ionic character, 3a exhibits lower solubility in hydrocarbons and was obtained from a THF solution at low temperature in 60% yield.

Scheme 3. Reactions of 2 and 3 with MeI.

The reactivities of 2 and 3 toward I(CH2)2I differ significantly. According to the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of the reaction mixtures, the reaction of 2 with I(CH2)2I gave solely new platinum complex 2b bearing a tBu2P–P–I ligand together with pTol3P (Scheme 4A). Moreover, in the 1H NMR spectrum of this reaction mixture, a resonance at 5.25 ppm attributed to ethylene is present. Complex 2b was isolated from a toluene solution at low temperature as brownish crystals in 50% yield. Otherwise, the reaction of 3 with I(CH2)2I did not yield the analogous platinum complex. The tBu2P–P group was lost from the Pt center, and the P—P bond within this ligand was cleaved, resulting in the formation of tBu2PI, insoluble orange phosphorus polymers, [(dppe)PtI2] (3b)42 and C2H4 (Scheme 4B).

Scheme 4. Reactions of 2 and 3 with X(CH2)2X (X = Br or I).

Surprisingly, the reaction of 3 with Br(CH2)2Br led to the formation of dimeric platinum complex 3c (Scheme 4C). This complex features a high-order 31P{1H} NMR spectrum with four multiplets at 67.9 ppm (t-Bu2P), 50.1 ppm (dppe), 47.1 ppm (dppe), and 120.1 ppm (P) (spin system AA′LL′MM′XX′). This suggests the formation of a tBu2PPPPtBu2 ligand in the coordination sphere of platinum. Complex 3c exhibits very low solubility in hydrocarbons, but it is highly soluble in dichloromethane (DCM). Crystallization from this solvent layered with toluene at room temperature gave large light-green crystals of 3c in 27% yield. The reaction of 2 with Br(CH2)2Br also gave products with high-order spectra (66.0 ppm (t-Bu2P), 23.3 ppm (pTol3P), −71.5 ppm (P); AA′MM′XX′ spin system) together with a strong resonance from free pTol3P and other minor unidentified products. This suggests the formation of the same tBu2PPPPtBu2 ligand, which coordinates to two Pt(pTol3P)Br fragments. However, unlike 3b, this platinum complex is highly soluble in hydrocarbons, and we were not able to obtain X-ray-quality crystals of this product.

In contrast to reactions of 1 with Br(CH2)nBr (n = 3, 4, 6), the analogous reactions involving 2 and 3 gave mostly oily products that were difficult to isolate and characterize. Despite this fact, we were able to obtain crystals of complex 2c from the reaction of 2 with an equimolar amount of Br(CH2)6Br (Scheme 5). The structure of 2c was unambiguously characterized by both NMR spectroscopy and single-crystal X-ray diffraction. 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy showed that the aforementioned reaction is very clean, where 2c and free pTol3P are the only products.

Scheme 5. Reactions of 2 with Br(CH2)6Br.

The 31P{1H} NMR data of complexes 2a–c, 3a, and 3c, together with corresponding data of parent compounds 2 and 3, are collected in Table 2.

Table 2. 31P{1H} NMR Data of 2, 3, 2a–c, 3a, and 3c.

| chemical

shifts [ppm] |

coupling constants [Hz] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | (R-)P1 | tBu2P2 | R′3P3 | R′3P4 | 1JP1P22JP1P32JP1P4 | 2JP2P32JP2P42JP3P4 | 1JP1Pt1JP2Pt1JP3Pt1JP4Pt |

| 2 | –38.8 | 77.5 | 30.5 | 22.5 | 615 | 206 | 52 |

| 2 | 34 | 1906 | |||||

| 21 | 4 | 3452 | |||||

| 3397 | |||||||

| 3 | –48.2 | 71.5 | 58.3 | 42.6 | 622 | 214 | 116 |

| 12 | 31 | 1894 | |||||

| 26 | 11 | 3358 | |||||

| 2915 | |||||||

| 2a | –97.7 | 61.2 | 22.3 | 483 | 295 | 349 | |

| 8 | 1653 | ||||||

| 3623 | |||||||

| 2b | –30.6 | 64.2 | 21.5 | 520 | 299 | 170 | |

| 6 | 1598 | ||||||

| 3523 | |||||||

| 2c | –68.0 | 54.8 | 23.4 | 483 | 299 | 432 | |

| 8 | 1694 | ||||||

| 3606 | |||||||

| 3a | –130.8 | 54.5 | 51.2 | 49.9 | 455 | 230 | 290 |

| 36 | 24 | 1710 | |||||

| 71 | 2990 | ||||||

| 2774 | |||||||

| 3c | –120.1 | 67.9 | 50.1 | 47.1 | 416 | ||

| 1696 | |||||||

| 3052 | |||||||

| 2854 | |||||||

The comparison of the 31P{1H} NMR data of platinum complexes with tBu2P2–P1–R (R = Me, I, (CH2)6Br, P–PtBu2) ligands with those of parent compounds 2 and 3 leads to several interesting observations. The 31P{1H} spectra of 2a, 2b, and 2c show only three resonances each, which suggests that one phosphine ligand left the coordination sphere of the metal center. On the other hand, the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of 3a and 3c each contain four resonances, indicating the presence of four inequivalent P atoms in these compounds. In comparison to parent species 2 and 3, the resonances of P1–R in the aforementioned complexes, except 2b, which contains a P—I moiety, are strongly upfield shifted, indicating the formation of new P—C (in 2a, 2c, and 3a) or P—P bonds (3c). In contrast, the resonances of tBu2P2 groups in the newly formed Pt complexes are comparable to those observed in parent species 2 and 3. A strong correlation between 1JP1P2 and P—P bond length is observed for phosphanylphosphinidene transition metal complexes.18 Two extreme examples are side-on platinum complex 2 (large 1JP1P2 = 615 Hz and very short P—P bond distance with value of 2.062(2) Å)12 and terminal zirconium complex [Cp2Zr(PPhMe2)(η1-P–PtBu2)] (small 1JP1P2 = 284 Hz and very long P—P bond distance with a value of 2.20(4) Å).33 The absolute values of 1JP1P2 in 2a–c and 3a are significantly decreased in comparison to those of 2 and 3, which suggests elongation of the P—P bond within the ligand. Notably, all resonances for P atoms in 2a–c, 3a, and 3c showed platinum satellites.

The small absolute values of 1JP1Pt, which are very characteristic of phosphanylphosphinidene complexes 2 and 3, are significantly increased in the newly formed compounds. Furthermore, the 1JP2Pt, 1JP3Pt, or 1JP4Pt coupling constants are similar to the corresponding values observed for 2, 3, [trans-(R3P)2PtCl2],43 and Pt(0) complexes with phosphine ligands.44 The relatively large absolute value of the 2JP2P3 couplings (295–299 Hz) in 2a–c suggests the trans orientation of the tBu2P1 moiety and the pTol3P3 ligand.

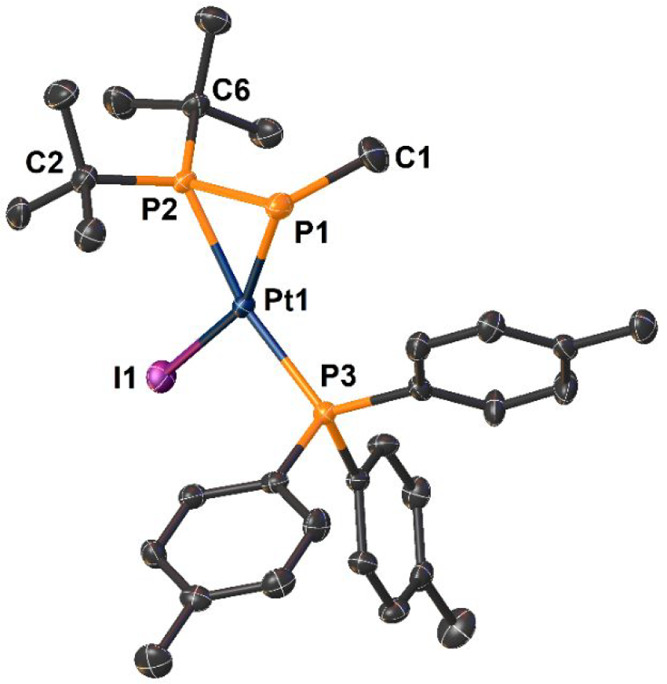

The solid-state structures of platinum complexes 2a, 2b, 2c, 3a, and 3c were studied by X-ray diffraction. The molecular structures of these compounds are shown in Figures 3–7. The X-ray studies of 2a, 2b, 2c, 3a, and 3c in solution are fully consistent with the NMR data of these complexes. In 2a, 2b, 2c, and 3a, the tBu2P–P–R moiety (R = Me (2a, 3a), I (2b), (CH2)6Br (2c)) is side-on coordinated to the Pt center (Figures 3–6), and the metal atom is tetracoordinated with a planar geometry. In 2a–c, in accordance with the 31P NMR data, the pTol3P ligand and tBu2P are in a trans orientation. Surprisingly, the geometries of the tBu2P–P–R ligands in 2a–c and 3a resemble those observed for tungsten complexes 1a–e: (i) the tBu2P group displays a high degree of planarity (ΣP2: 345.4° to 347.2°); (ii) the P—P bonds have lengths in between the lengths typical of single and double bonds (2.149(3) Å to 2.173(1) Å) and are significantly longer than P—P bonds in precursor complexes 2 (2.062(2) Å)12 and 3 (2.072(3) Å);13 (iii) the angles P2—P1—R have values in a narrow range of 108.6(2)° to 110.1(3)°; (iv) one of the tBu groups is syn-periplanar with respect to the R group with torsion angles for C(tBu)–P2—P1—R from −12.5(5)° to 8.3(4)°.

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of complex 2a. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—Pt1 2.350(2), P2—Pt1 2.285(1), P3—Pt1 2.292(1), I1—Pt1 2.6658(5), P1—P2 2.156(2), C1—P1 1.863(6), ΣP1 278.2, ΣP2 347.1 (neglecting the P2—Pt1 bond), C1—P1—P2 108.6(2), C1—P1—P2—C6 −10.3(3).

Figure 7.

Molecular structure of complex dication 3c. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms and bromide anions are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—Pt1 2.415(1), P2—Pt1 2.287(1), P3—Pt1 2.304(1), P4—Pt1 2.275(1), P1—P2 2.165(1), P1—P1′ 2.235(1), ΣP1 277.8, ΣP2 346.8 (neglecting the P2—Pt1 bond), P2—P1—P1′ 106.34(5), P2—P1—P1′—P2′ 180 (centrosymmetric structure).

Figure 6.

Molecular structure of complex cation 3a. One molecule out of the three present in the asymmetric unit was selected. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms, solvent molecules, and iodide anion are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—Pt1 2.406(2), P2—Pt1 2.285(2), P3—Pt1 2.274(2), P4—Pt1 2.274(2), P1—P2 2.157(3), C100—P1 1.862(8), ΣP1 278.5, ΣP2 345.4 (neglecting the P2—Pt1 bond), C100—P1—P2 108.6(2), C100—P1—P2–C62 8.3(4).

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of complex 2b. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—Pt1 2.310(1), P2—Pt1 2.282(1), P3—Pt1 2.3004(9), I1—Pt1 2.6551(5), P1—P2 2.173(1), I2—P1 2.491(1), ΣP1 280.4, ΣP2 347.2 (neglecting the P2—Pt1 bond), I2—P1—P2 109.57(5), I2—P1—P2—C1 −7.9(2).

Figure 5.

Molecular structure of complex 2c. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability. H atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1—Pt1 2.322(3), P2—Pt1 2.282(2), P3—Pt1 2.283(2), Br1—Pt1 2.519(1), P1—P2 2.149(3), C9—P1 1.87(1), ΣP1 278.0, ΣP2 347.2 (neglecting the P2—Pt1 bond), C9—P1—P2 109.6(3), C9—P1—P2—C5 −12.5(5).

Unlike tungsten complexes 1a–c and 1e, in the aforementioned platinum complexes significant elongation of the P1—M1 bond resulting from the attachment of the R group to the P1 atom was not observed. The P1—Pt1 distances in 2a–c (2.310(1) Å to 2.350(2) Å) are even shorter than that in parent species 2 (2.409(2) Å), whereas in 3a, the P1—Pt1 bond length (2.406(2) Å) is very similar to the corresponding distance in 3 (2.387(2) Å). The P2—Pt1, P3—Pt1, and P4—Pt1 distances are comparable to those observed in platinum complexes with phosphine ligands.45

The molecular structure of complex dication 3c is presented in Figure 7. It consists of tetraphosphorus ligand tBu2P2—P1—P1′—P2′tBu2 and two dppe ligands that coordinate to two platinum centers. Additionally, two bromide counterions are present in the second coordination sphere (not shown in Figure 7).

The metal centers show square planar geometries and the whole molecule is centrosymmetric (point group Ci). As a consequence, the P2—P1—P1′—P2′ bonds lie in the same plane with a corresponding torsion angle of 180° and the two (dppe)Pt moieties are located on opposite sides of this plane. The P1—P1′ bond (2.235(1) Å) has a length typical of a single covalent P—P bond, whereas the P2—P1 and P2′—P1′ bonds are 0.07 Å shorter. The platinum—phosphorus bonds in 3c and in parent complex 3 have very similar lengths. Dimeric molybdenum and tungsten complexes with analogous tBu2PPPPtBu2 ligands were previously synthesized by our group from the reaction of Li[Cp*(CO)3] with tBu2P–PCl2.46 The tetraphosphorus ligands in these complexes displayed geometries very similar to the corresponding ligand in 3c.

We performed DFT calculations (see SI for details) to further elucidate the electronic structures of the obtained tungsten and platinum complexes. As presented in the previous paragraphs, W or Pt complexes with tBu2P–P–R exhibit many common structural features. Therefore, for this study we selected representative complexes 1a, 2a (tBu2P–P–Me ligand), and 2b (tBu2P–P–I ligand). Moreover, we studied the electronic properties of complex 3c′ (tBu2P–P–P–PtBu2 ligand) with a skeleton similar to that of 3c in which the dppe ligands were replaced by dmpe (Me2PCH2CH2PMe2) groups to simplify the calculations. Our previous theoretical studies on tungsten complex 1 revealed that the P1—P2 bond within the tBu2P2–P1 ligand is polarized toward the phosphinidene P1-atom. Furthermore, the P1—P2 and P2—W1 bonds are essentially single bonds, whereas the P1—W1 bond has double bond character. Moreover, a lone electron pair is present on the P1 atom. In the case of Pt complex 2, similar to 1, the phosphanylphosphinidene ligand displays a positively charged P2 atom and a negatively charged P1 atom. In contrast to 1, Pt complex 2 exhibits a P1=P2 double bond and has two lone pairs on the P1 atom.18 NBO analysis of complexes 1a, 2a, and 2b indicates that the P1—P2 bond within the tBu2P–P–R ligand as well as the P1—M1 and P2—M1 bonds have single-bond character. The mentioned complexes display one lone pair of electrons on the P1 atom. The shortening of the P1—P2 bonds in 1a, 2a, and 2b can be explained by the interactions of the antibonding σ*(P2–C) orbitals with the orbital attributed to the lone pair on the P1 atom (negative hyperconjugation). The analysis of the Hirshfeld charges of complexes 1a, 2a, and 2b revealed that the positive charge is located on the P2 atom of the phosphanyl group, whereas the charge on the P1 atom is close to zero (Table 3). Moreover, the W1 atom in 1a is positively charged, whereas the charges on the Pt1 atoms in 2a and 2b are close to zero. As it can be expected, in the case of 1a significant negative charges are located on imido and chlorido ligands, as well as methyl group bound to P1 atom (Figure S72). In complexes 2a and 2b, negative charge is located primarily on iodido ligands and on the methyl group (2a) or iodine atom (2b) directly bound to P1 atom (Figures S73 and S74). These results indicate that the phosphorus ligands in 1a, 2a, and 2b can be seen as coordinated diphosphenium cations tBu2P+=P–R resulting formally from the reaction of the tBu2P–P group with the R+ cation. A similar bonding mode is observed in complex 3c, where dicationic tBu2P+=P–P=P+tBu2 ligand coordinates to two platinum metal centers. Notably, based on our previous calculations, the phosphorus ligands in dimeric complexes [Cp*M(CO)3(η2-tBu2PP)]2 (M = Mo, W) possess analogous Lewis structures.46

Table 3. Calculated Hirshfeld Charges (q) and Wiberg Bond Indexes for Complexes 1a, 2a, 2b, and 3c.

| Hirshfeld

charges |

Wiberg bond indexes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | q(P2) | q(P1) | q(M1) | P1—P2 | P1—P1′ | P1—M | P2—M |

| 1a | 0.194 | 0.057 | 0.431 | 1.002 | 0.727 | 0.511 | |

| 2a | 0.208 | 0.033 | 0.030 | 1.116 | 0.510 | 0.490 | |

| 2b | 0.205 | 0.004 | 0.043 | 1.093 | 0.556 | 0.479 | |

| 3c′ | 0.193 | –0.023 | 0.035 | 1.089 | 0.983 | 0.412 | 0.461 |

Consequently, we performed analogous calculations for free phosphenium cations tBu2P+=P–Me (I),tBu2P+=P–I (II) and (tBu2P+=P)2 (III). On the basis of our calculations, these species have a singlet ground state. The optimized structures of I–III are presented in Figures S66, S70, and S71, and their selected optimized parameters together with Hirshfeld charges are collected in Table 4.

Table 4. Calculated Hirshfeld Charges (q) and Optimized Parameters for Free Phosphenium Cations I–IIIa.

| cation | q(P2) | q(P1) | P1—P2 (Å) | P1—P1′ (Å) | ΣP2 (°) | P2—P1—R (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tBu2P+=P-Me(I) | 0.304 | 0.220 | 2.036 | 359.3 | 107.4 | |

| (1a: 2.160) (2a: 2.156) | (1a: 341.7) (2a: 347.1) | (1a: 109.9) (2a: 108.6) | ||||

| tBu2P+=P—I(II) | 0.294 | 0.168 | 2.055 | 359.3 | 109.0 | |

| (2b: 2.173) | (2b: 347.2) | (2b: 109.6) | ||||

| (tBu2P+=P)2(III) | 0.345 | 0.140 | 2.057 | 2.224 | 359.9 | 102.4 |

| (3c: 2.165) | (3c: 2.235) | (3c: 346.8) | (3c: 106.3) |

Values in parentheses are experimental parameters for the corresponding ligands in 1a, 2a, 2b, and 3c.

As expected, the P atoms in I-III are positively charged with a large charge on the P2 atom and a smaller positive charge on the P1 atom. A comparison of the geometries of I-III with the geometries of the corresponding ligands in 1a, 2a, 2b, and 2c reveals several similarities, such as the planar geometric alignment of the tBu2P2 phosphanyl group, the very close values of the P2—P1—R angles, and the same syn-periplanar conformation (Table 4). Similar structural features also include the isolated, noncoordinated diphosphenium cation Mes*(Me)P+=PMes*.47 However, in comparison to the corresponding ligands in the W and Pt complexes, the P1—P2 bonds in I–III are significantly shorter and have double bond character. This important structural difference can be explained by considering the complexation of these cationic ligands to the metal center. In free ligands I–III, the lone pair on the P2 atom (tBu2P group) is mainly involved in P—P π-bonding, whereas in the corresponding complexes, this lone pair interacts with the metal center.

3. Conclusions

Our studies showed that phosphanylphosphinidene complexes of tungsten and platinum are valuable substrates in the synthesis of not only new diphosphorus ligand species but also new polydentate phosphorus ligands. The reactions of complexes [(DippN)2W(Cl)(η2-P–PtBu2)]− (1), [(pTol3P)2Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (2), and [(dppe)Pt(η2-P=PtBu2)] (3) with MeI and haloalkanes gave a wide range of transition metal complexes bearing ligands with two or four P-donor atoms. Nucleophilic 1 is very reactive toward Br(CH2)nBr (n = 3, 4, 6), forming unprecedented dinuclear complexes bearing tetradentate ligands where two tBu2P–P groups are linked by an aliphatic chain (n = 4, 6) or monometallic complexes with a tBu2P–P(CH2)3Br ligand. The reactions of platinum complexes with MeI and dihaloalkanes gave even more diverse compounds. We showed that the tBu2P–P ligand in the starting platinum complexes can be easily functionalized by introducing a wide range of substituents on terminal P-phosphinidene atoms, such as halogen atoms, Me, (CH2)nBr or P–PtBu2 groups. Despite the diversity of functionalized phosphanylphosphinidene ligands, they exhibit many structural similarities and can be described as phosphenium cations tBu2P+=P − R or (tBu2P+=P)2. In summary, the presented results may be of importance in the synthesis of polydentate phosphorus ligands coordinated to TM with possible catalytic activity.

4. Experimental Section

General Information

All experiments were carried out under an argon atmosphere using Schlenk techniques. All manipulations were performed using standard vacuum, Schlenk, and glovebox techniques. All solvents were purified and dried using common methods. Solvents for NMR spectroscopy (C6D6 and CDCl3) were purified from metallic sodium or P2O5. The phosphanylphosphinidene tungsten complex [(2,6-iPr2C6H3N)2(Cl)W(η2-tBu2P–P)]Li·3DME (1)11 and phosphanylphosphinidene platinum complex [(pTol3P)2Pt(η2-tBu2P=P)] (2)12 were synthesized following literature methods. Methyl iodide, 1,2-diiodoethane, 1,2-dibromoethane, 1,3-dibromopropane, 1,4-dibromobutane and 1,6-dibromohexane were purchased from commercial sources. All of the solutions of dibromoalkanes, methyl iodide, and 1,2-diiodoethane used in this work were freshly prepared prior to use. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III HD 400 MHz spectrometer at ambient temperature (external standards: TMS for 1H and 13C; 85% H3PO4 for 31P). The chemical shifts of Ci and CH2 in some cases were not determined due to the absence of these signals in the 13C{1H} NMR spectra. The Cl/Br ratio in the case of tungsten complexes was determined on the basis of the 31P NMR spectra. Crystallographic analyses were performed on an STOE IPDS II diffractometer using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Elemental analyses were performed at the University of Gdańsk using a Vario El Cube CHNS apparatus.

Synthesis of 1b

To a solution of 1 (0.512 g, 0.500 mmol) in 4 mL of DME was dropwise added 0.873 mL of a solution of 1,3-dibromopropane (0.500 mmol, CM = 0.573 M) at −30 °C. After warming to room temperature, NMR spectra were collected every 5 min for 30 min. The reaction was complete after this time. The solvent was evaporated, the solid residue was redissolved in pentane, and the LiBr precipitate was removed by filtration. Yellow crystals of 1b-Cl/1b-Br (0.213 g, 0.240 mmol, yield 48%, molar ratio 1b-Cl/1b-Br equals 0.6:0.4 on the basis of the 31P NMR spectrum) were obtained from the pentane filtrate at −30 °C. Mixing in C6D6 or DME and heating overnight at 50 °C did not result in the formation of a compound analogous to 1d.

NMR data for 1b:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 1.22 (broad s, 12H, HC(CH3)2), 1.27 (d, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 6H, HC(CH3)2), 1.28 (d, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 6H, HC(CH3)2), 1.35 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 18H, C(CH3)3), 1.82 (m, 2H, PCH2), 2.44 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.89 (m, 2H, CH2Br), 4.09 (m, 4H, HC(CH3)2), 6.97 (m, 2H, CAr–Hp), 7.07 (m, overlapped, 4H, CAr–Hm).

1b-Cl: 31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 40.0 (d, 1JPP = 375 Hz, 1JPW = 17 Hz, tBu2P), −125.3 (d, 1JPP = 375 Hz, 1JPW = 80 Hz, P(CH2)3Br).

1b-Br: 31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 36.9 (d, 1JPP = 381 Hz, 1JPW = 17 Hz, tBu2P), −132.2 (d, 1JPP = 381 Hz, 1JPW = 80 Hz, P(CH2)3Br).

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 22.8 (dd, 1JCP= 44 Hz, 2JCP= 4 Hz, PCH2), 23.7 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 23.8 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 24.1 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 27.9 (m, HC(CH3)2), 31.6 (broad s, C(CH3)3), 32.8 (m, CH2), 35.1 (m, BrCH2), 37.6 (very broad s, C(CH3)3), 122.4 (s, Cm), 122.5 (s, Cm), 125.8 (broad s, Cp), 144.3 (m, overlapped, Co), 152.3 (m, overlapped, Ci).

Elemental analysis calculated for C35H58Br1.4Cl0.6N2P2W (M = 885.77 g/mol): % C = 47.46%, % H = 6.60%, % N = 3.16%; found % C = 47.55%, % H = 6.70%, % N = 3.15%.

Synthesis of 1c

To a solution of 1 (0.506 g, 0.494 mmol) in 4 mL of DME was dropwise added 1.29 mL of a solution of 1,4-dibromobutane (0.494 mmol, CM = 0.383 M) at −30 °C. After warming to room temperature, NMR spectra were collected every 5 min for 30 min. The solvent was evaporated, the solid residue was redissolved in pentane, and the LiBr precipitate was removed by filtration. Yellow crystals of 1c-Cl/1c-Br (0.133 g, 0.084 mmol, yield 34.1%, molar ratio 1c-Cl/1c-Br equals 1.3:0.7 on the basis of the 31P NMR spectrum) were obtained from the pentane filtrate at −30 °C. Crystals for NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis were obtained from a toluene solution at −30 °C, and the crystals contain two molecules of toluene in the structure.

NMR data for 1c:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 1.23 (very broad s, overlapped, 24H, HC(CH3)2), 1.28 (d, overlapped, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 24H, HC(CH3)2), 1.38 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 36H, C(CH3)3), 1.55 (broad m, 4H, PCH2), 2.32 (m, 4H, CH2), 4.11 (very broad s, 8H, HC(CH3)2), 6.98 (m, 4H, CAr–Hp), 7.07 (m, overlapped, 8H, CAr–Hm).

1c-Cl: 31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 40.3 (d, 1JPP = 378 Hz, 1JPW = 17 Hz, tBu2P), −122.2 (d, 1JPP = 378 Hz, 1JPW = 76 Hz, P(CH2)4).

1c-Br: 31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 37.2 (d, 1JPP = 383 Hz, 1JPW = 17 Hz, tBu2P), −129.1 (d, 1JPP = 383 Hz, 1JPW = 80 Hz, P(CH2)4).

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 23.7 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 23.8 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 24.2 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 27.8 (m, overlapped, HC(CH3)2), 31.6 (broad s, (C(CH3)3), 37.4 (broad s, C(CH3)3), 122.4 (s, Cm), 122.5 (s, Cm), 125.7 (broad s, Cp), 144.2 (m, overlapped, Co), 152.3 (m, overlapped, Ci), CH2– are not visible due to the broadness.

Elemental analysis calculated for C82H128Br0.5Cl1.5N4P4W2 (M = 1754.63 g/mol): % C = 56.13%, % H = 7.35%, % N = 3.19%; found % C = 56.03%, % H = 7.26%, % N = 3.18%.

Synthesis of 1d

The reaction was conducted using the same amounts of reactants as were used to synthesize 1c-Cl/1c-Br at room temperature, and after 3 days almost all 1c-Cl/1c-Br was gone and 1d was formed along with [(2,6-iPr2C6H3N)2WX2·DME (X = Cl, Br). The molar ratio of the products (1d/1c) was 2.3:1 based on the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum (70% 1d and 30% 1c-Cl/1c-Br, not taking into account other products of this reaction).

NMR data for 1d:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 1.24 (d, 3JPH = 7 Hz, 18H, C(CH3)3), 1.54 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.77 (m, 4H, CH2).

31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): δ 42.3 (d, 1JPP = 203 Hz, tBu2P), −37.3 (d, 1JPP = 203 Hz, P(CH2)4).

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 26.2 (dd, 1JCP = 18 Hz, 2JCP = 13 Hz, PCH2), 28.6 (broad s, CH2), 31.6 (broad s, (C(CH3)3), 32.8 (dd, 1JCP = 30 Hz, 2JCP = 7 Hz, C(CH3)3).

Synthesis of 1e

To a solution of 1 (0.493 g, 0.480 mmol) in DME was dropwise added 1.68 mL of a solution of 1,6-dibromohexane (0.480 mmol, CM = 0.286 M) at −30 °C. After warming to room temperature, NMR spectra were collected every 5 min for 30 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the solid residue was redissolved in pentane. Colorless crystals of 1e-Cl/1e-Br (0.162 g, 0.101 mmol, yield 42%, molar ratio 1e-Cl/1e-Br equals 1.3:0.7 on the basis of the 31P NMR spectrum) were grown at −30 °C. Adding the reactants in the reverse manner results in the same NMR spectra and crystalline product. No formation of a compound analogous to 1d was observed at RT.

NMR data for 1e:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 0.99 (broad m, overlapped, 4H, PCH2), 1.25 (broad s, overlapped, 4H, CH2), 1.25 (very broad s, 18H, HC(CH3)2), 1.30 (d, overlapped, 30H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, HC(CH3)2), 1.40 (d, 36H, 3JPH = 16 Hz, C(CH3)3), 2.38 (m, 4H, CH2), 4.14 (m, 8H, HC(CH3)2), 6.97 (m, 4H, CAr–Hp), 7.08 (m, overlapped, 8H, CAr–Hm).

1e-Cl: 31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 40.5 (d, 1JPP = 378 Hz, 1JPW = 18 Hz, tBu2P), −122.1 (d, 1JPP = 378 Hz, 1JPW = 80 Hz, P(CH2)6).

1e-Br: 31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 37.4 (d, 1JPP = 382 Hz, 1JPW = 18 Hz, tBu2P), −129.0 (d, 1JPP = 382 Hz, 1JPW = 80 Hz, P(CH2)6).

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 23.8 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 23.9 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 24.2 (broad s, HC(CH3)2), 24.2 (dd, 1JCP = 44 Hz, 2JCP = 6 Hz, PCH2), 27.8 (s, overlapped, HC(CH3)2), 27.9 (s, overlapped, HC(CH3)2), 30.4 (m, CH2), 31.7 (broad s, C(CH3)3), 32.7 (m, CH2), 37.5 (broad s, C(CH3)3), 122.4 (s, Cm), 122.5 (s, Cm), 125.7 (broad s, Cp), 144.4 (m, overlapped, Co), 152.5 (m, overlapped, Ci).

Additionally, the signals attributable to pentane are visible in the 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra.

Elemental analysis calculated for (1e·pentane): C75H128Br0.7Cl1.3N4P4W2 (M = 1679.44 g/mol): % C = 53.64%, % H = 7.68%, % N = 3.34%; found % C = 53.41%, % H = 7.80%, % N = 3.13%.

Synthesis of 2a

To a suspension of 2 (0.379 g, 0.383 mmol) in toluene was dropwise added 0.586 mL of a solution of methyl iodide (0.383 mmol, CM = 0.653 M) at −30 °C. The reaction was complete after 1 h, which was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. The solvent was evaporated, and the solid residue was dissolved partially in pentane and the rest in toluene. Colorless crystals of 2a were obtained from both fractions at −30 °C but they were contaminated with pTol3P (the crystals obtained from toluene were much less contaminated than those from pentane). The yield of crystals from the toluene fraction was 49.2% (0.154 g, 0.188 mmol).

NMR data for 2a:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 0.73 (m, 3H, H3C–P), 1.35 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 9H, C(CH3)3), 1.37 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 9H, C(CH3)3), 1.93 (s, 9H, p-CH3-C6H4), 6.90 (d, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 6H, CAr–Hm), 7.80 (m, 6H, CAr–Ho).

31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 61.2 (dd, 1JPP = 483 Hz, 2JPP = 295 Hz, 1JPPt = 1653 Hz, tBu2P), 22.3 (dd, 2JPP = 295 Hz, 2JPP = 8 Hz, 1JPPt = 3623, pTol3P), −97.7 (dd, 1JPP = 483 Hz, 2JPP = 8 Hz, 1JPPt = 349 Hz, PMe), weak signal of pTol3P (s, −7.9 ppm) was visible.

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 3.7 (dd, 1JCP = 55 Hz, 2JCP = 7 Hz, H3C-P), 20.8 (s, p-CH3–C6H4), 31.8 (d, 2JCP = 8 Hz, C(CH3)3), 32.2 (m, C(CH3)3), 36.1 (m, C(CH3)3), 37.2 (m, C(CH3)3), 128.9 (d, 3JCP = 10 Hz, Cm), 130.8 (dd, 1JCP = 51 Hz, 3JCP = 2 Hz, Ci), 134.5 (d, 2JCP = 12 Hz, Co), 139.9 (d, 4JCP = 2 Hz, Cp).

Elemental analysis calculated for C30H42IP3Pt (M = 817.5642 g/mol): % C = 44.07%, % H = 5.18%, found % C= 44.84%, % H = 5.23%

Synthesis of 2b

To a suspension of 2 (0.418 g, 0.422 mmol) in toluene was dropwise added a solution of 1,2-diiodoethane (0.119 g, 0.422 mmol) in 1 mL of toluene at −30 °C. The reaction was complete after 2 h, which was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. Light-brown crystals of 2b (0.198 g, 0.213 mmol, yield 50.5%) were obtained from a toluene solution at −30 °C.

NMR data for 2b:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 1.24 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 9H, (CH3)3C), 1.68 (d, 3JPH = 17 Hz, 9H, (CH3)3C), 1.99 (s, 9H, p-CH3–C6H4), 6.97 (d, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 6H, CAr–Hm), 7.87 (m, 6H, CAr–Ho).

31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 64.2 (dd, 1JPP = 520 Hz, 2JPP = 299 Hz, 1JPPt = 1598 Hz, tBu2P), 21.5 (dd, 2JPP = 299 Hz, 2JPP = 6 Hz, 1JPPt = 3523, pTol3P), −30.6 (dd, 1JPP = 520 Hz, 2JPP = 6 Hz, 1JPPt = 170 Hz, PI).

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 20.8 (s, p-CH3–C6H4), 31.6 (m, overlapped, (CH3)3C), 37.8 (m, (CH3)3C), 39.2 (m, (CH3)3C), 129.1 (d, 3JCP = 11 Hz, Cm), 134.6 (d, 2JCP = 11 Hz, Co), 140.3 (d, 4JCP = 2 Hz, Cp), Ci not visible in the spectrum.

Elemental analysis calculated for C29H39I2P3Pt (M = 929.4342 g/mol): % C = 37.47%, % H = 4.23%, found % C = 38.01%, % H = 4.29%.

Synthesis of 2c

To a suspension of 2 (0.373 g, 0.376 mmol) in 4 mL of DME was dropwise added 1.32 mL of a solution of 1,6-dibromohexane (0.376 mmol, CM = 0.284 M) at −30 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature, and NMR spectra were acquired. The reaction was complete (no signals of the starting complex) after 30 min. The solvent was evaporated, and the oily residue was partially dissolved in pentane. A small amount of yellow crystals of 2c suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained upon dilution of the pentane solution at room temperature.

NMR data for 2c:

1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 0.94 (m, overlapped, 6H, PCH2 and CH2), 1.33 (m, overlapped, 4H, CH2), 1.42 (d, 3JPH = 15 Hz, 9H, C(CH3)3), 1.51 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 9H, C(CH3)3), 1.78 (broad m, 2H, BrCH2), 1.90 (s, 9H, p-CH3–C6H4), 6.94 (m, 6H, CAr–Hm), 7.86 (m, 6H, CAr–Ho).

31P{1H} NMR (C6D6, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 54.8 (dd, 1JPP = 483 Hz, 2JPP = 299 Hz, 1JPPt = 1694 Hz, tBu2P), 23.4 (dd, 2JPP = 299 Hz, 2JPP = 8 Hz, 1JPPt = 3606 Hz, pTol3P), −68.0 (dd, 1JPP = 483 Hz 2JPP = 8 Hz, 1JPPt = 432 Hz, P(CH2)6Br).

13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 20.0 (dd, 1JCP = 50 Hz, 2JCP = 7 Hz, PCH2), 20.8 (s, p-CH3–C6H4), 27.6 (s, CH2), 30.0 (m, CH2), 30.8 (m, CH2), 31.6 (broad d, 2JCP = 8 Hz, C(CH3)3), 32.2 (broad m, C(CH3)3), 32.4 (s, CH2)), 33.2 (s, CH2), 36.1 (m, C(CH3)3), 37.6 (m, C(CH3)3), 128.9 (d, 3JCP = 11 Hz, Cm), 130.7 (d, 1JCP = 50 Hz, Ci), 134.6 (d, 2JCP = 12 Hz, Co), 139.9 (broad s, Cp).

Synthesis of 3

A slightly modified version of the synthesis of [(dppe)Pt(η2-tBu2P=P)] previously described in the literature was used.13 A solution of dppe in toluene was added to a suspension of 2 in toluene at room temperature, and the mixture was stirred for 2–3 days. The volume of the solution was decreased to a quarter of the original volume and it was stirred for another day. Then, the solution was layered with two volumes of petroleum ether, and the resulting precipitate was washed with a 1:2 toluene/ether mixture, resulting in pure [(dppe)Pt(η2-tBu2P=P)] as a solid (∼60% yield).

NMR data for 3: see ref (13).

Synthesis of 3a

To a suspension of 3 (0.385 g, 0.5 mmol) in toluene was dropwise added 0.577 mL of a solution of methyl iodide (0.5 mmol, CM = 0.653 M) at −30 °C. The reaction mixture was then warmed to room temperature, and a large amount of white solid formed. The solvent was evaporated, and the solid residue was dissolved in THF. Colorless crystals of 3a (290 mg, 0.295 mmol, 60% yield) were obtained from the THF solution at −20 °C.

NMR data for 3a:

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 0.99 (m, 3H, PCH3), 1.11 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 9H, C(CH3)3), 1.16 (d, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 9H, C(CH3)3), 1.18 (m, 4H, THF), 2.50 (broad m, 2H, CH2, dppe), 2.87 (broad m, 2H, CH2, dppe), 3.67 (m, 4H, THF), 7.31–7.56 (m, overlapped, 16 H, CAr-H), 7.66 (m, overlapped, 2H, CAr-H), 7.82 (m, overlapped, 2H, CAr-H).

31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 54.5 (ddd, 1JPP = 455 Hz, 2JPP = 230 Hz, 2JPP = 24 Hz, 1JPPt = 1710 Hz, tBu2P), 51.2 (dd, 2JPP = 230 Hz, 2JPP = 36 Hz, 1JPPt = 2990 Hz, dppe), 49.9 (dd, 2JPP = 71 Hz, 2JPP = 24 Hz, 1JPPt = 2774 Hz, dppe), −130.8 (ddd, 1JPP = 455 Hz, 2JPP = 71 Hz, 2JPP = 36 Hz, 1JPPt 290 Hz, PMe).

13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 5.13 (dd, 1JCP = 52 Hz, 2JCP = 8 Hz, 3JCP = 4 Hz, PCH3), 25.6 (s, THF), 28.3 (dd, 2JCP = 37 Hz, 2JCP = 13 Hz, CH2, dppe), 30.6 (ddd, 2JCP = 37 Hz, 2JCP = 11 Hz, 3JCP = 4 Hz CH2, dppe), 31.7 (d, 2JCP = 9 Hz, C(CH3)3), 31.8 (m, overlapped, C(CH3)3), 36.3 (broad m, C(CH3)3), 38.2 (broad m, C(CH3)3), 68.0 (s, THF), 129.2–134.2 (m, overlapped, CAr, dppe).

Elemental analysis calculated for C39H53IOP4Pt (M = 983.7210g/mol): % C = 47.62%, % H = 5.43%, found % C = 47.60%, % H = 5.54%.

Synthesis of 3b

To a suspension of 3 (0.385 g, 0.5 mmol) in 4 mL toluene was dropwise added a solution of 1,2-diiodoethane (0.141 g, 0.500 mmol) in 1 mL of toluene at −30 °C. The solvent was evaporated, and the solid residue was partially dissolved in toluene and the rest was dissolved in DCM. A small amount of orange solid (polyphosphorus compounds) was not soluble in any accessible solvent. After evaporation of the toluene, the oily residue of tBu2PI48 remained, which was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. Large yellow crystals of 3b(42) were obtained from a DCM solution at −30 °C.

Synthesis of 3c

To a suspension of 3 (0.308 g, 0.400 mmol) in 4 mL of DME was dropwise added 0.847 mL of a solution of 1,2-dibromoethane (0.400 mmol, CM = 0.472 M) at −30 °C. Then, the mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature, and a substantial amount of yellow residue formed during heating. The residue was washed with toluene and dissolved in DCM. The DCM solution was further layered with toluene, and large, light-green crystals of 3c (0.111 g, 0.108 mmol, yield 27%) suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained at room temperature.

NMR data for 3c:

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, 298 K δ): 0.82 (broad d, overlapped, 3JPH = 16 Hz, 36H, C(CH3)3), 1.54 (broad s, 2H, CH2, dppe), 2.12 (broad s, 2H, CH2, dppe), 2.77 (broad s, 2H, CH2, dppe), 3.16 (broad s, 2H, CH2, dppe), 5.31 (s, 4H, CH2Cl2), 7.36 (broad, s, 4H, CAr–H), 7.52 (broad, s, 18H, CAr–H), 7.71 (broad, s, 14H, CAr–H), 8.14 (broad, s, 4H, CAr–H).

31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 162 MHz, 298 K, δ): 67.9 (m, tBu2P), 50.1 (d, 2JPP = 120 Hz, dppe), 47.1 (m, dppe), −120.1 (m, P).

13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz, 298 K δ): 30.2 (m, CH2, dppe), 30.6 (m, CH2, dppe), 31.4 (broad s, C(CH3)3), 37.2 (very broad m, C(CH3)3), 40.4 (very broad m, C(CH3)3), 53.4 (s, CH2Cl2), 129.7 (broad s, CAr, dppe), 130.5 (broad m, overlapped, CAr, dppe), 131.5 (broad m, overlapped, CAr, dppe), 132.6 (broad m, overlapped, CAr, dppe), 133.4 (broad m, overlapped, CAr, dppe), 134.7 (broad m, overlapped, CAr, dppe).

Elemental analysis calculated for C36H46BrCl4P4Pt (M = 1019.44 g/mol): % C = 42.41%, % H = 4.55%, found % C = 42.66%, % H = 4.60%.

Acknowledgments

A.O. and J.P. thank the National Science Centre, Poland (Grant 2017/25/N/ST5/00766) for financial support. The authors thank the TASK Computational Center for access to computational resources.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c00091.

Crystallographic details, spectroscopic details, and computational details (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 1963412–1963419 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Waterman R. Metal-Phosphido and -Phosphinidene Complexes in P-E Bond-Forming Reactions. Dalton Trans. 2009, 9226 (1), 18–26. 10.1039/B813332H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathey F. The Development of a Carbene-like Chemistry with Terminal Phosphinidene Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1987, 26 (4), 275–286. 10.1002/anie.198702753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathey F.; Huy N. H. T.; Marinetti A. Electrophilic Terminal-Phosphinidene Complexes: Versatile Phosphorus Analogues of Singlet Carbenes. Helv. Chim. Acta 2001, 84 (10), 2938–2957. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma K. Phosphinidenes. Top. Curr. Chem. 2003, 229, 95–119. 10.1007/b11152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathey F. Developing the Chemistry of Monovalent Phosphorus. Dalton Trans. 2007, 2007 (19), 1861–1868. 10.1039/b702063p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley A. H. Terminal Phosphinidene and Heavier Congeneric Complexes. The Quest Is Over. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30 (11), 445–451. 10.1021/ar970055e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Nieves J.; Sterenberg B. T.; Udachin K. A.; Carty A. J. A Thermally Stable and Sterically Unprotected Terminal Electrophilic Phosphinidene Complex of Cobalt and Its Conversion to an H1-Phosphirene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (9), 2404–2405. 10.1021/ja028303b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham T. W.; Udachin K. A.; Zgierski M. Z.; Carty A. J. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of the First Thermally Stable, Neutral, and Electrophilic Phosphinidene Complexes of Vanadium. Organometallics 2011, 30 (6), 1382–1388. 10.1021/om100915v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas H.; Slootweg J. C.; Lammertsma K. Nucleophilic Phosphinidene Complexes: Access and Applicability. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49 (12), 2102–2113. 10.1002/anie.200905689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A. W.; Baerends E. J.; Lammertsma K. Nucleophilic or Electrophilic Phosphinidene Complexes MLn=PH; What Makes the Difference?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124 (11), 2831–2838. 10.1021/ja017445n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubba R.; Baranowska K.; Chojnacki J.; Pikies J. Access to Side-On Bonded Tungsten Phosphanylphosphinidene Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012 (20), 3263–3265. 10.1002/ejic.201200456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domańska-Babul W.; Chojnacki J.; Matern E.; Pikies J. Reactions of R2P-P(SiMe3)Li with [(R’3P)2PtCl2]. A general and efficient entry to phosphanylphosphinidene complexes of platinum. Syntheses and structures of [(η2-P=PiPr2)Pt(p-Tol3P)2], [(η2-P=PtBu2)Pt(p-Tol3P)2], [{η2-P=P(NiPr2)2}Pt(p-Tol3P)2] and [{(Et2PhP)2Pt}2P2]. Dalton Trans. 2009, 668504 (1), 146–151. 10.1039/B807811D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautscheid H.; Matern E.; Fritz G.; Pikies J. Komplexchemie P-reicher Phosphane und Silylphosphane. XIV. Einfluß der Chelatbildner dppe und dppp auf die Bildung und die Eigenschaften der Pt-Komplexe des tBu2P-P. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1998, 624, 501–505. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa J. S.; Cummins C. C. Diorganophosphanylphosphinidenes as Complexed Ligands: Synthesis via an Anionic Terminal Phosphide of Niobium. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43 (8), 984–988. 10.1002/anie.200352779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. R.; Clough C. R.; Piro N. A.; Cummins C. C. A Terminal Nitride-to-Phosphide Conversion Sequence Followed by Tungsten Phosphide Functionalization Using a Diphenylphosphenium Synthon. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46 (6), 973–976. 10.1002/anie.200604736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann M. M.; Jazzar R.; Bertrand G. Singlet (Phosphino)Phosphinidenes Are Electrophilic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (27), 8356–8359. 10.1021/jacs.6b04232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olkowska-Oetzel J.; Pikies J. Chemistry of the Phosphinophosphinidene tBu2P-P, a Novel π-Electron Ligand. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2003, 17 (1), 28–35. 10.1002/aoc.387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zauliczny M.; Ordyszewska A.; Pikies J.; Grubba R. Bonding in Phosphanylphosphinidene Complexes of Transition Metals and Their Correlation with Structures, 31P NMR Spectra, and Reactivities. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 3131. 10.1002/ejic.201800270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins C. C.; Schrock R. R.; Davis W. M. Phosphinidenetantalum(V) Complexes of the Type [(N3N)Ta = PR] as Phospha-Wittig Reagents (R = Ph, Cy, tBu, N3N = Me3SiNCCH2CH2)3N). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32 (5), 756–759. 10.1002/anie.199307561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker B. F.; Scott J.; Andino J. G.; Gao X.; Park H.; Pink M.; Mindiola D. J. Phosphinidene Complexes of Scandium: Powerful PAr Group-Transfer Vehicles to Organic and Inorganic Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (11), 3691–3693. 10.1021/ja100214e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z.; Breen T. L.; Stephan D. W. Formation and Reactivity of the Early Metal Phosphides and Phosphinidenes Cp*2Zr:PR, Cp*2Zr(PR)2, and Cp*2Zr(PR)3. Organometallics 1993, 12 (8), 3158–3167. 10.1021/om00032a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urnezius E.; Lam K. C.; Rheingold A. L.; Protasiewicz J. D. Triphosphane Formation from the Terminal Zirconium Phosphinidene Complex [Cp2Zr = PDmp(PMe3)] (Dmp = 2,6-Mes2C6H3) and Crystal Structure of DmpP(PPh2)2. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 630 (2), 193–197. 10.1016/S0022-328X(01)00863-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breen T. L.; Stephan D. W. Phosphinidene Transfer Reactions of the Terminal Phosphinidene Complex Cp2Zr(:PC6H2-2,4,6-t-Bu3)(PMe3). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117 (48), 11914–11921. 10.1021/ja00153a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziółkowska A.; Szynkiewicz N.; Ponikiewski Ł. Molecular Structures of the Phospha-Wittig Reaction Intermediate: Initial Step in the Synthesis of Compounds with a C = P-P Bond as Products in the Phospha-Wittig Reaction. Organometallics 2019, 38, 2873–2877. 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez C. M.; Alvarez M. A.; García M. E.; González R.; Ruiz M. A.; Hamidov H.; Jeffery J. C. High-Yield Synthesis and Reactivity of Stable Diiron Complexes with Bent-Phosphinidene Bridges. Organometallics 2005, 24 (23), 5503–5505. 10.1021/om050617v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez M. A.; García M. E.; González R.; Ruiz M. a. Reactions of the Phosphinidene-Bridged Complexes [Fe2(η5-C5H5)2(μ-PR)(μ-CO)(CO)2] (R = Cy, Ph) with Electrophiles Based on p-Block Elements. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41 (48), 14498. 10.1039/c2dt31506h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Termaten A. T.; Nijbacker T.; Schakel M.; Lutz M.; Spek A. L.; Lammertsma K. Synthesis of Novel Terminal Iridium Phosphinidene Complexes. Organometallics 2002, 21 (15), 3196–3202. 10.1021/om020062t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kourkine I.; Glueck D. Synthesis and Reactivity of a Dimeric Platinum Phosphinidene Complex. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36 (9), 5160–5164. 10.1021/ic970730g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo A. J.; Calabrese J. C.; Cowley A. H.; Dias H. V. R.; Goerlich J. R.; Marshall W. J.; Riegel B. Carbene-Pnictinidene Adducts. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36 (10), 2151–2158. 10.1021/ic970174q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back O.; Henry-Ellinger M.; Martin C. D.; Martin D.; Bertrand G. 31P NMR Chemical Shifts of Carbene-Phosphinidene Adducts as an Indicator of the π-Accepting Properties of Carbenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (10), 2939–2943. 10.1002/anie.201209109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Mondal K. C.; Kundu S.; Li B.; Schürmann C. J.; Dutta S.; Koley D.; Herbst-Irmer R.; Stalke D.; Roesky H. W. Two Structurally Characterized Conformational Isomers with Different C-P Bonds. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (50), 12153–12157. 10.1002/chem.201702870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S.; Sinhababu S.; Siddiqui M. M.; Luebben A. V.; Dittrich B.; Yang T.; Frenking G.; Roesky H. W. Comparison of Two Phosphinidenes Binding to Silicon(IV)Dichloride as Well as to Silylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (30), 9409–9412. 10.1021/jacs.8b06230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikies J.; Baum E.; Matern E.; Chojnacki J.; Grubba R.; Robaszkiewicz A. A New Synthetic Entry to Phosphinophosphinidene Complexes. Synthesis and Structural Characterisation of the First Side-on Bonded and the First Terminally Bonded Phosphinophosphinidene Zirconium Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2004, 98 (21), 2478–2479. 10.1039/B409673H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubba R.; Ordyszewska A.; Kaniewska K.; Ponikiewski Ł.; Chojnacki J.; Gudat D.; Pikies J. Reactivity of Phosphanylphosphinidene Complex of Tungsten(VI) toward Phosphines: A New Method of Synthesis of Catena-Polyphosphorus Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54 (17), 8380–8387. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubba R.; Ordyszewska A.; Ponikiewski Ł.; Gudat D.; Pikies J. An Investigation on the Chemistry of the R2P = P Ligand: Reactions of a Phosphanylphosphinidene Complex of Tungsten(VI) with Electrophilic Reagents. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (5), 2172–2179. 10.1039/C5DT03085D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikiewski Ł.; Ziółkowska A.; Pikies J. Reactions of Lithiated Diphosphanes R2P-P(SiMe3)Li (R = tBu and iPr) with [MeNacnacTiCl2·THF] and [MeNacnacTiCl3]. Formation and Structure of TitaniumIII and TitaniumIV β-Diketiminato Complexes Bearing the Side-on Phosphanylphosphido and Phosphanylphosphinidene Functionalities. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56 (3), 1094–1103. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautscheid H.; Matern E.; Kovacs I.; Fritz G.; Pikies J. Komplexchemie P-reicher Phosphane und Silylphosphane. XIV. Phosphinophosphiniden tBu2P-P als Ligand in den Pt-Komplexen [{η2-tBu2P-P}Pt(PPh3)2] und [{η2-tBu2P-P}Pt(PEtPh2)2]. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1997, 623, 1917–1924. 10.1002/zaac.19976231216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright W. R. H.; Batsanov A. S.; Howard J. A. K.; Tooze R. P.; Hanton M. J.; Dyer P. W. Exploring the Reactivity of Tungsten Bis(Imido) Dimethyl Complexes with Methyl Aluminium Reagents: Implications for Ethylene Dimerization. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39 (30), 7038–7045. 10.1039/c0dt00110d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P.; Atsumi M. Molecular Single-Bond Covalent Radii for Elements 1–118. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15 (1), 186–197. 10.1002/chem.200800987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedeskamp B. K.; Reising J. G.; Malisch W.; Hindahl K.; Schemm R.; Sheldrick W. S. Phosphenium Transition Metal Complexes. Part 34. P-Functionalized Cyclic Phosphinidenemetallophosphoranes [Cyclic] Cp(CO)2W-P(X)(t-Bu)-P(t-Bu) (X = Cl, H): Direct Formation from Metallophosphines and Transformation Reactions. Organometallics 1995, 14 (10), 4446–4448. 10.1021/om00010a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber L.; Noveski G.; Stammler H.-G.; Neumann B. Über Den Phosphandiyl-Transfer von Invers-Polarisierten Phosphaalkenen R1P = C(NMe2)2 (R1 = tBu, Cy, Ph, H) Auf Phospheniumkomplexe [(η5-C5H5)(CO)2M = P(R2)R3] (R2 = R3 = Ph; R2 = tBu, R3 = H; R2 = Ph, R3 = N(SiMe3)2). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2007, 633 (7), 994–999. 10.1002/zaac.200700034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishna A.; Su H.; Moss J. R. [1,2-Bis(Diphenylphosphino)Ethane]Diiodidoplatinum(II) Dichloromethane Disolvate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2007, 63 (11), m2648 10.1107/S1600536807046636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matern E.; Pikies J.; Fritz G. Zum Einfluß Der PR3-Liganden Auf Bildung Und Eigenschaften Der Phosphinophosphiniden-Komplexe [{η2-tBu2P-P}Pt(PR3)2] Und [{η2-tBu2P1-P2}Pt(P3R3)(P4R′3)]. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2000, 626 (10), 2136–2142. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatt J.; Mason R.; Meek D. W. Unusually Large Platinum-Phosphorus Coupling Constants in Platinum(0) Tetraphosphine Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97 (13), 3826–3827. 10.1021/ja00846a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melník M.; Mikuš P. Organophosphines in Organoplatinum Complexes - Structural Aspects of Trans-PtP2CCl Derivatives. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 819, 46–52. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2016.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grubba R.; Zauliczny M.; Ponikiewski Ł.; Pikies J. The Reactivity of 1,1-Dichloro-2,2-Di-Tert-Butyldiphosphane towards Lithiated Metal Carbonyls: A New Entry to Phosphanylphosphinidene Dimers. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (12), 4961. 10.1039/C5DT04983K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loss S.; Widauer C.; Grützmacher H. Strong P = P π Bonds: The First Synthesis of a Stable Phosphanyl Phosphenium Ion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38 (22), 3329–3331. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs I.; Fritz G. tBu2P-P = P(X)tBu2-Ylide (X = C1, Br, I) Durch Halogenierung von [tBu2P]2P-SiMe3. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1994, 620, 1364–1366. 10.1002/zaac.19946200806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.