Abstract

The management of COVID-19 patients in the ICUs requires several and prolonged life-support systems (mechanical ventilation, continuous infusions of medications and nutrition, renal replacement therapy). Parameters have to be entered continuously into the device user interface by healthcare personnel according to the dynamic clinical condition. This leads to an increased risk of cross-contamination, use of personal protective equipment and the need for stringent and demanding protocols. Cables and tubing extensions have been utilized to make certain devices usable outside the patient's room but at the cost of introducing further hazards. Remote control of these devices decreases the frequency of unnecessary interventions and reduces the risk of exposure for both patients and healthcare personnel.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare-associated infections, HAI, Remote control, Medical devices, Monitoring, Infectious diseases, Renal replacement therapy, RRT, KRT, Ventilators

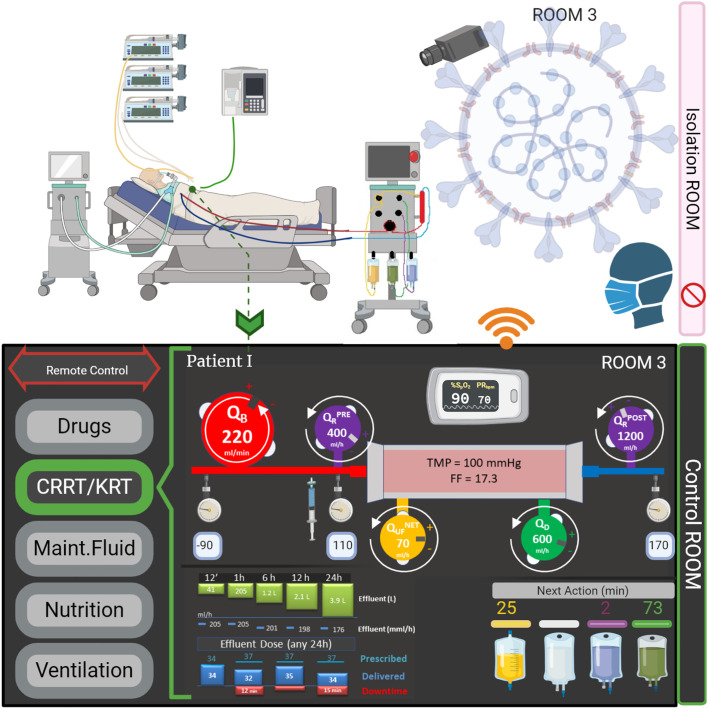

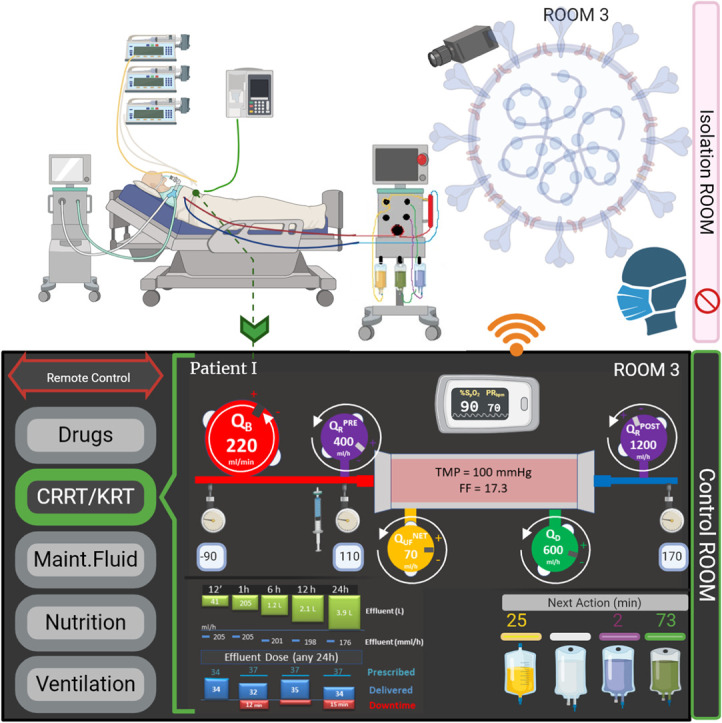

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

healthcare-associated Infections (including respiratory viral and bacterial infections) are increasing especially in high-risk areas such as ICUs

-

•

the management of critically ill patients requires several and prolonged life-support devices (ventilators, extracorporeal circuits, infusion pumps) increasing the risk of cross-contamination by aerosol, infected organic fluids or direct contact

-

•

remote control of these devices, from a separated control-room, reduces unnecessary personnel biohazard exposure and contacts for both patients and healthcare workers

-

•

bidirectional communication with medical equipment has potential to prevent contamination of patients and medical staff by limiting the spread of infections and allows for time and cost saving due to the reduced need of PPE

List of abbreviations

| ARDS | acute respiratory disease syndrome |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019. |

| CRRT | continuous renal replacement therapy |

| EUA | Emergency Use Authorizations |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GUI | graphical user interface |

| HAI | Healthcare-associated Infections |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| PPE | personal protective equipment |

| RRT/KRT | Renal Replacement Therapy/Kidney Replacement Therapy |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

1. Background

At the end of 2019, infection with a novel coronavirus, named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), resulted in an acute respiratory illness termed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO issued preliminary guidelines for prevention and control of infection based on recommendations released for management of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in Saudi Arabia in 2012. Several other viral epidemics such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002–2003, and H1N1 influenza infection in 2009, have been recorded worldwide. SARS-CoV-2 virus quickly spread globally killing more than one million people to date, despite important containment measures taken by the 210 most affected countries [1].

Even though we constantly face infectious diseases, this one seems very contagious, forcing healthcare workers to take strict precautionary measures to prevent hospital cross-contaminations, particularly when looking after critically ill patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 [2]. In an early report [3], 41% of hospitalized COVID-19 cases had additional hospital-acquired infections including patients who were hospitalized for other pathologies and healthcare workers. They represent 3.8% of the 44.672 confirmed cases described by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [4]. During the SARS epidemic this percentage rose to 51.8% [5]. There are several important contributing factors: first, the proximity and duration of contact with infected patients, and second, the high risk of exposure to aerosol-generating procedures, especially endotracheal intubation and ventilation. Furthermore, transmission from an infected (and potentially asymptomatic) healthcare worker to patients can occur through respiratory droplets, aerosol and physical contact. As SARS-CoV-2 seems to be able to spread quickly, the issue of healthcare-associated Infections (HAI) is particularly important. Respiratory viral HAIs are already known to be a serious problem, and viral surveillance screening programs [6] are increasing, especially in high-risk areas such as Intensive Care Units (ICUs), bone marrow transplant and oncology wards [7]. In addition to viruses, bacteria present in the environment can be an important source of infections, typically associated with medical devices, such as vascular catheters or ventilators. This element becomes even more serious and important in the case of Multi-Drug Resistant Organisms (MDRO). It has been reported that, despite protocols to prevent contamination which are shared by the prevention controls units of all the countries, HAIs affect approximately 1.7 million patients annually in the US and 8.3% of patients admitted to ICU for more than 48 h in Europe [8]. Moreover, HAIs are well known to be associated with increased costs, longer length of stay and higher mortality rates [6].

1.1. Cross-contaminations and Medical Devices remote control

The management of Covid-19 patients in the ICU requires the use of several different life-support systems, often for a prolonged period. In severe cases, Covid-19 may be complicated by acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS), sepsis and septic shock, multiorgan failure, including acute kidney injury (AKI) and cardiac failure. Patients are cared for in ICU facilities equipped with ventilators and accessories, vital signs monitoring systems and syringe pumps for nutrition, drugs and fluid administration. In addition, Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT) machines for management of AKI and fluid overload [9] and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be required. The utilisation of these devices can be challenging, especially in a biohazard environment, as regular adjustment of various different parameters by healthcare personnel is often required. This increases the risk of cross-contamination due to aerosol, infected organic fluids or direct contact with the contaminated device panel [10,11]. To mitigate these risks and to reduce the consumption of personal protective equipment (PPE) [12], a group of anaesthesiologists recently connected cable extensions in order to make ventilators' control panel usable outside patients' rooms. Some suppliers have made these cables available as accessories. They have also been approved by regulatory agencies. Site assessments and independent double checks have been agreed according to local procedures (e.g. attaching the patient's barcode in an accessible location for scanning). Moreover, extension tubing sets have been integrated into infusion pumps and RRT machine lines, at the cost of introducing further hazards as described by a UK Government alert [13]. In the current crisis, the risks and benefits [14] need to be re-assessed and actions aimed to increase patient safety [15] should be taken immediately. A step forward in managing medical devices in an emergency setting (but not only then), where patients and medical equipment are exposed to viral and bacterial cross-contamination [16], is the use of remote-control systems to avoid bio-hazardous interactions. For the same reason, the FDA reconsidered the benefits/risks of remote control systems and allowed expanded use of devices to monitor patients' vital signs remotely [17]. Nowadays, the data from several medical devices are steadily collected, displayed remotely, analysed and stored using real-time monitoring software. Advantages of remote control use and monitoring have already been reported in home peritoneal dialysis, including updating the prescription of personalized therapies [18]. Furthermore, an improvement in health-related quality of life has been shown in patients with remote control of pacemaker settings [19].

Although there was some initial resistance to the introduction in clinical practice, all these systems are currently viewed as essential, both in hospital and in-home settings. At this point in time, communication between a remote station and the devices placed in the patient's room is not only technologically possible but essential in many areas (Fig. 1 ). It also reduces unnecessary and frequent biohazard exposure of personnel and limits physical contacts between patients and healthcare workers. Furthermore, the need for PPE is reduced which saves time and costs.

Fig. 1.

Remote Control of Medical Devices in ICUs.

Example of implementation of remote control and monitoring in an ICU setting. The control panel, located in a separate control room, is connected to the devices (RRT in the current image). Modification of parameters can be undertaken by medical personnel, without the need to enter the patient's room.

Here, we propose a minimum set of parameters needed for a basic remote-control device. Focusing on a CRRT device, we suggest that blood flow rate (QB), net ultrafiltration flowrate (QNET UF), dialysate (QD) and replacement flow rates (QR PRE, QR POST) and anticoagulant infusion can be remotely controlled (Figure 1 and Table 1 ). In case of regional anticoagulation, the citrate dose and calcium compensation variation shall be allowed in order to maintain systemic and post-filter ionized calcium in the correct range, according to local protocols [20]. Importantly, monitoring of continuous circuit pressures (Table 2 .) [21], such as the inflow and outflow, pre- and post- filter and effluent pressure, has potential to prevent premature filter clotting and catheter-related interruptions resulting in less downtime and better provision of the prescribed dose. Other data than those related to the administered dose and the schedule of maintenance for technical reason, for instance, bag changes or blood sampling, are important in order to minimize device interventions and improve and optimize the CRRT prescription. It is important to note that currently available RRT devices have a different number of scales and pumps, requiring specific prescriptions and management. The Nomenclature Standardization Initiative alliance [22] raised awareness among manufacturers and highlighted the need for a common language to facilitate the development of a generic remote platform. A special effort should be undertaken to allow interface customization according to the patient / caregivers needs. With regards to mechanical ventilation, certain parameters need to be set and adjusted, such as the ventilation mode (volume, pressure or dual) and the modality (controlled, assisted, support ventilation). In addition, several respiratory parameters are collected: tidal volume, minute volume in volume modalities, peak pressure, respiratory frequency, positive end expiratory pressure, inspiratory time, inspiratory flow, inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio, time of pause, trigger sensitivity, support pressure, and expiratory trigger sensitivity. A minimum set of parameters for both volume and pressure control are reported in Table 3 . Alarms and monitoring for tidal and minute volume, peak pressure, plateau pressure, respiratory rate, FiO2, and apnea must be adjustable [23,24].

Table 1.

Renal Replacement Therapies (RRT) remote control. Example of main parameter to control by a RRT remote unit.

| Symbol | Unit of measure | Color | Allowed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood flow rate | QB | ml/min | red | ≤ + 20%* |

| Net ultrafiltration flow rate | QUFNET | ml/h | yellow | |

| Replacement flow rate | QRPRE – QRPOST QRPRE – POST |

ml/h | Purple | |

| Dialysate flow rate | QD | ml/h | green | |

| Anticoagulant heparin |

QEFF |

ml/h |

white |

|

| Calcium Citrate |

ml/h or compensation(%) mmol/L |

orange/ black |

A visual inspection of circuit and vascular access are mandatory for >20% in blood flow.

Table 2.

Renal Replacement Therapies monitoring. Example of main parameter to monitor from a remote unit.

| Symbol | Unit of measure | Color | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-flow pressure/ Pre-filter pressure | QB | mmHg | red |

| Post-filter/Out-flow pressure | QRPRE/POST | mmHg | dark blue |

| Effluent pressure | QD | mmHg | yellow |

| Transmembrane TMP pressure | TMP | mmHg | |

| Actual dose | Dose | ml/kg/h | |

| Next action | Next | minutes |

Table 3.

Ventilator remote control, main parameters:

| Parameter | Symbol (Unit of Measure) | Volume control | Pressure Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction of inspired oxygen | FiO2 (%) | X | X |

| Tidal Volume | VT (mL/Kg) | X | |

| Inspiratory Pressure | Pinsp | X | |

| Inspiratory Time OR Inspired to Expired |

Ti (s) I:E |

X | X |

| Respiratory Rate | RR (bpm) | X | X |

| Positive End-Expiratory Pressure | PEEP (cmH2O) | X | X |

| Inspiratory Flow | Flow (L/min) | X | |

| Trigger | O | O | |

| Support Pressure | PSUPP(cmH2O) | O | O |

| Inspiratory pause | TIpause | O | O |

Abbreviations: X: Mandatory, O: Optionals.

Regarding drug and fluid administration, infusion pumps require the flow rate to be set. Although most infusion pumps administer fluids in millilitres per hour (ml/h), a volumetric flow, some can be programmed to administer in milligrams per kg per hour (mcg/kg/min), a mass flow. Techniques exist to assess and monitor the pressures generated within the pump.

1.2. Technological issues

The care of ICU patients can be complex, involving different multidisciplinary teams and many therapies. In addition, decisions often need to be made quickly. To ensure patient safety in this complex clinical setting, a wide range of actions is necessary to deliver care, facilitate appropriate use of devices, prevent infections, ensure safe drug prescribing and promote a safe working environment [15,25].

It is extremely useful for healthcare workers to have all clinical information available in one place when making a decision. The implementation of a unique scalable platform [26] to support several devices and IT services simultaneously would be an optimal solution. At present, there are several potential options in the ICU, from simple data exchange to bidirectional communication with monitors. In general, these solutions require customization that also involves support from hospital IT services, especially when devices of different brands need to be connected.

The lack of interoperability between medical devices can lead to preventable medical errors and potentially serious inefficiencies [25]. Looking at future implementations, a feasibility study in healthy pigs has already been conducted utilizing a fully automated life support system [26].

Existing frameworks focus predominantly on reducing workload but other aspects may improve, too, including patient safety and prevention of infections. To facilitate the successful interoperability of devices and IT systems, it is necessary to agree how to define connectivity and synchronization, end-to-end encryption, integrity and confidentiality of information. Safety, general requirements and conceptual model have already been defined by the American Society for Testing and Materials International [27]. Communication standards and remote control, including a bidirectional communication platform, have been defined by the ISO/IEEE [28] for medical point of care devices. This will also facilitate the communication between the vast number of devices and different suppliers. Future communication protocols should involve multidisciplinary teams of different medical disciplines with the aim to evaluate and mitigate clinical risks [14]. If standards are essential for effective technology interoperability, human communication is equally relevant and highly considered in the emerging field of human factors analyses [29]. To define common terminology and color-coding, thus reducing user errors, the nomenclature related to RRT [30,31] has been agreed as mentioned above.

We recently raised several points for consideration related to Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) and relevant therapies beyond 2027 [32]. In the light of the recent COVID-19 crisis, communication with devices should be anticipated and prioritized even if currently available systems with network capability typically only connect to their own proprietary platforms. While prioritizing the development of a generic platform, suppliers should enable a temporary solution to control the device in the same clinical unit where the patient is treated. With the introduction of 5G, the short time required for a set of data to travel between two points (latency) will allow for safer remote control. In the immediate future, a local connection can be chosen, thus avoiding the need to open to a “public” and less secure (for both stability and cybersecurity) public network. Remote desktop applications, often utilized for remote assistance, are widely available and may represent an easier and more effective way to allow remote control of devices during the COVID-19 emergency. In this case, the graphical user interface (GUI) of the device can allow full control. This can be viewed as a software alternative to the user interface extension cable. In this way, a human intervention can be actioned immediately. Thus, mitigating both the probability of failure and the harm from a bio-hazard, the overall risk related to caring for a COVID-19 patient is reduced.

To ensure an appropriate level of safety and to prevent accidental changes, a “remote modality” should be set at the beginning of any new treatment while the user interface should always be password protected. Lastly, in order to preserve and improve patient safety, medical prescriptions and all devices should be linked to one patient only (e.g. through radio-frequency identification wristbands), thus avoiding drug errors.

1.3. Regulatory issues

From a regulatory point of view, devices “shall be safe and effective and shall not compromise the clinical condition or the safety of patients, or the safety and health of users…” and”…any risks which may be associated with their use constitute acceptable risks when weighed against the benefits to the patient…” [33]. Thus, it is necessary to take into account the associated risks and biohazards of multiple extension lines when placing devices outside the patient's room, as highlighted by several suppliers of infusion pumps and RRT devices in specific field safety notices [34,35] and a recent UK Government Alert [13]. Flow rate may also be impacted by a higher resistance to flow due to longer tubing. Its internal diameter, the length and the materials are within the fluid viscosity variables that impact on the phenomena magnitude. Furthermore, pressure monitoring, disconnections or catheter related problems may not be revealed which contributes further to the risks for the patients.

The implementation of such a system capable of modifying the settings of a device during treatment requires an analysis of all risks, further validation, submission to a regulatory agency (notified bodies in Europe) and, once approved, an official launch. This process which is mandatory for all medical software, is usually long; however, approval may be accelerated in exceptional circumstances, for instance in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [36]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already issued Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA) for various diagnostic, therapeutic, and protective medical devices including ventilators, infusion pumps and extracorporeal blood purification systems. Furthermore the FDA has allowed medical device suppliers to make changes to existing products, such as changes to devices or materials, in an easier way [37].

2. Conclusions

In a critical care setting, direct patient monitoring and patient interaction are key elements of clinical practice. However, the frequency of these interactions should be re-evaluated in particular circumstances, such as in high biological risk situations. Device-associated HAIs pose a severe threat to patients, although many advances have been made in the field of prevention that have led to a significant risk reduction.

Similar to other pandemics, we have learnt from Covid-19 outbreaks that the virus can spread quickly among patients and medical personnel. In these critical settings, preventing transmission of infections and protecting healthcare workers should be priority in order to preserve medical personnel resources and achieve patient safety.

The advantage of bi-directional communication with medical equipment is the prevention of contamination of patients and medical staff. A personalized therapy prescription and administration with strict monitoring of vital signs are further advantages. Interoperability of devices and IT systems will also facilitate decision making and timely interventions. In the coming years, preventing infectious diseases to hospitalized patients and protecting healthcare workers should be a daily priority; especially (but not exclusively) during recurring viral epidemics [38].

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Autors' contributions

FG paper conception, manuscript draft, literature search, provide intellectual content.

RIC manuscript draft, literature search, figure preparation.

MO manuscript revision, final revision.

FN manuscript draft, contribute to field improvements, final approval.

DG manuscript revision, provide risk analysis content and final approval.

GM manuscript revision, final revision, provide intellectual content.

MGB paper conception, paper content, final review.

GZ manuscript revision, final revision, provide intellectual content.

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of supporting data

Not applicable

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report– 105 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200504-covid-19-sitrep-105.pdf?sfvrsn=4cdda8af_2

- 2.Alhazzani W., Møller M.H., Arabi Y.M., Loeb M., Gong M.N., Fan E. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng V.C.C., Chan J.F.W., To KKW, Yuen K.Y. Clinical management and infection control of SARS: lessons learned. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godoy P., Torner N., Soldevila N., Rius C., Jane M., Martínez A. Hospital-acquired influenza infections detected by a surveillance system over six seasons, from 2010/2011 to 2015/2016. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:80. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spaeder M.C., Fackler J.C. Hospital-acquired viral infection increases mortality in children with severe viral respiratory infection. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e317–e321. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182230f6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healthcare-associated infections | HAI | CDC 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/index.html (accessed May 5, 2020).

- 9.for the DoReMIFA study group, Garzotto F, Ostermann M, Martín-Langerwerf D, Sánchez-Sánchez M, Teng J, et al The dose response multicentre investigation on fluid assessment (DoReMIFA) in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:196. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1355-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y., He L., Asiamah T.K., Otto M. Colonization of medical devices by staphylococci. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:3141–3153. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Percival S.L., Suleman L., Vuotto C., Donelli G. Healthcare-associated infections, medical devices and biofilms: risk, tolerance and control. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:323–334. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC Strategies to Optimize the Supply of PPE and Equipment. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html accessed May 12, 2020.

- 13.COVID-19 All haemofiltration systems including machines and accessories – serious risks if users don't follow manufacturer instructions for set-up (MDA/2020/013) 2020. https://www.gov.uk/drug-device-alerts/covid-19-all-haemofiltration-systems-including-machines-and-accessories-serious-risks-if-users-don-t-follow-manufacturer-instructions-for-set-up-mda-2020-013

- 14.Lodi C.A., Vasta A., Hegbrant M.A., Bosch J.P., Paolini F., Garzotto F. Multidisciplinary evaluation for severity of hazards applied to Hemodialysis Devices: an original risk analysis method. CJASN. 2010;5:2004–2017. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01740210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nalesso F., Garzotto F., Rossi B., Cattarin L., Simioni F., Carretta G. Proactive approach for the patient safety in the extracorporeal blood purification treatments in nephrology. G Ital Nefrol. 2018;35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iordanou S., Middleton N., Papathanassoglou E., Raftopoulos V. Surveillance of device associated infections and mortality in a major intensive care unit in the Republic of Cyprus. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:607. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2704-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enforcement Policy for Non-Invasive Remote Monitoring Devices Used to Support Patient Monitoring During the Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/enforcement-policy-non-invasive-remote-monitoring-devices-used-support-patient-monitoring-during

- 18.Milan Manani S., Crepaldi C., Giuliani A., Virzì G.M., Garzotto F., Riello C. Remote monitoring of automated peritoneal Dialysis improves personalization of Dialytic prescription and Patient’s Independence. Blood Purif. 2018;46:111–117. doi: 10.1159/000487703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comoretto R.I., Facchin D., Ghidina M., Proclemer A., Gregori D. Remote control improves quality of life in elderly pacemaker patients versus standard ambulatory-based follow-up. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23:681–689. doi: 10.1111/jep.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oudemans-van Straaten H.M., Ostermann M. Bench-to-bedside review: citrate for continuous renal replacement therapy, from science to practice. Crit Care. 2012;16:249. doi: 10.1186/cc11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.on behalf of the Nomenclature Standardization Initiative (NSI) Alliance, Villa G, Neri M, Bellomo R, Cerda J, De Gaudio AR, et al Nomenclature for renal replacement therapy and blood purification techniques in critically ill patients: practical applications. Crit Care. 2016;20:283. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronco C. The Charta of Vicenza. Blood Purif. 2015;40:I–V. doi: 10.1159/000437399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrillo Alvares A., López-Herce Cid J. Parameters of mechanical ventilation. An Pediatr (Barc) 2003;59:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva P.L., Rocco P.R.M. The basics of respiratory mechanics: ventilator-derived parameters. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:376. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.06.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nauman J., Soteriades E.S., Hashim M.J., Govender R., Al Darmaki R.S., Al Falasi R.J. Global incidence and mortality trends due to adverse effects of Medical treatment, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis from the global burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors study. Cureus. 2020 doi: 10.7759/cureus.7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moustafa H., Schooler E.M., Shen G., Kamath S. 2016 IEEE 12th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob) IEEE; New York, NY: 2016. Remote monitoring and medical devices control in eHealth; pp. 1–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ASTM . 2013. Medical Devices and Medical Systems - Essential safety requirements for equipment comprising the patient-centric integrated clinical environment (ICE) - Part 1: General requirements and conceptual model. [Google Scholar]

- 28.IEEE . 2018. 11073–10207-2017 - IEEE Health informatics--Point-of-care medical device communication Part 10207: Domain Information and Service Model for Service-Oriented Point-of-Care Medical Device Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner U. Risks in the application of Medical Devices: human factors in the Medical environment. Qual Manag Health Care. 2010;19:304–311. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181f9ee66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.on behalf of the Nomenclature Standardization Initiative (NSI) alliance, Neri M, Villa G, Garzotto F, Bagshaw S, Bellomo R, et al Nomenclature for renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: basic principles. Crit Care. 2016;20:318. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1489-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nalesso F., Garzotto F. Nomenclature for renal replacement therapies in chronic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark W.R., Neri M., Garzotto F., Ricci Z., Goldstein S.L., Ding X. The future of critical care: renal support in 2027. Crit Care. 2017;21:92. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1665-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC (Text with EEA relevance.). Vol. 117. 2017.

- 34.Factors to consider when using additional tubing with B. Braun Space™ and Outlook® large volume infusion pumps to increase the distance between the pump and the patient. BBraun COVID-19 Information n.d. https://www.bbraunusa.com/content/dam/b-braun/us/website/company/covid-files/clinical-resources/B%20Braun%20Long%20IV%20Pump%20Sets%20-%20Points%20of%20Consideration.pdf (accessed May 12, 2020).

- 35.Prismaflex Control Unit FA-2020-006 Safety Alert n.d. https://mhra-gov.filecamp.com/s/CJHbAucFi1MoWagc/d (accessed May 12, 2020).

- 36.Garzotto F., Ceresola E., Panagiotakopoulou S., Spina G., Menotto F., Benozzi M. COVID-19: ensuring our medical equipment can meet the challenge. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2020.1772757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Ventilator Supply Mitigation Strategies: Letter to Health Care Providers, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/letters-health-care-providers/ventilator-supply-mitigation-strategies-letter-health-care-providers (accessed May 5, 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable