Abstract

Objective

Examine the effectiveness of specific modes of exercise training in non-specific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP).

Design

Network meta-analysis (NMA).

Data sources

MEDLINE, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, EMBASE, CENTRAL.

Eligibility criteria

Exercise training randomised controlled/clinical trials in adults with NSCLBP.

Results

Among 9543 records, 89 studies (patients=5578) were eligible for qualitative synthesis and 70 (pain), 63 (physical function), 16 (mental health) and 4 (trunk muscle strength) for NMA. The NMA consistency model revealed that the following exercise training modalities had the highest probability (surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA)) of being best when compared with true control: Pilates for pain (SUCRA=100%; pooled standardised mean difference (95% CI): −1.86 (–2.54 to –1.19)), resistance (SUCRA=80%; −1.14 (–1.71 to –0.56)) and stabilisation/motor control (SUCRA=80%; −1.13 (–1.53 to –0.74)) for physical function and resistance (SUCRA=80%; −1.26 (–2.10 to –0.41)) and aerobic (SUCRA=80%; −1.18 (–2.20 to –0.15)) for mental health. True control was most likely (SUCRA≤10%) to be the worst treatment for all outcomes, followed by therapist hands-off control for pain (SUCRA=10%; 0.09 (–0.71 to 0.89)) and physical function (SUCRA=20%; −0.31 (–0.94 to 0.32)) and therapist hands-on control for mental health (SUCRA=20%; −0.31 (–1.31 to 0.70)). Stretching and McKenzie exercise effect sizes did not differ to true control for pain or function (p>0.095; SUCRA<40%). NMA was not possible for trunk muscle endurance or analgesic medication. The quality of the synthesised evidence was low according to Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria.

Summary/conclusion

There is low quality evidence that Pilates, stabilisation/motor control, resistance training and aerobic exercise training are the most effective treatments, pending outcome of interest, for adults with NSCLBP. Exercise training may also be more effective than therapist hands-on treatment. Heterogeneity among studies and the fact that there are few studies with low risk of bias are both limitations.

Keywords: physical activity, spine, rehabilitation, physical therapy modalities, behavioural symptoms, analgesics, catastrophization

Introduction

Low back pain is the leading cause of disability1 and the most common of all non-communicable diseases.2 Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is pain lasting 12 weeks or longer,3 localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain.4 While CLBP makes up approximately 20%5 of all low back pain cases, it generates approximately 80% of the direct costs of low back pain.6 In up to 90% of patients with CLBP, clinicians cannot make a specific diagnosis and therefore patients are classified as having ‘non-specific’ CLBP.7 There is a need to identify and evaluate the efficacy of interventions capable of treating non-specific CLBP.

Previous pairwise meta-analyses have shown that passive treatments such as ultrasound,8 hot and cold therapy9 and massage without exercise training10 failed to reduce pain in adults with non-specific CLBP. In contrast, exercise training has collectively been shown to be effective in reducing pain when compared with non-exercise training-based treatments in adults.11–13 Similarly, pairwise meta-analyses examining specific kinds of exercise have shown that Pilates,14 15 stabilisation/motor control15 16 and yoga17 may reduce pain better than non-exercise training comparators. However, whether specific types of exercise training are more effective in non-specific CLBP has received limited attention. One prior pairwise meta-analysis explored this question and concluded that resistance and stabilisation/motor control exercise training were effective, compared with true control (ie, no intervention), whereas aerobic and combined modalities (ie, programmes including multiple types of exercise such as aerobic, resistance and stretching) were not.12

Pairwise meta-analyses rely on the included randomised controlled/clinical trials (RCTs) having similar intervention and control groups. This approach excludes RCTs that do not have a similar comparator. Meta-analysis implemented the pragmatic, yet problematic, approach of including RCTs where the intervention was a mix of specific modes of exercise training and another intervention type, such as manual therapy.15 A limitation of this approach is that researchers are unable to determine the degree in which each component of the included interventions influenced the overall treatment effect. Network meta-analyses can overcome these limitations by incorporating data from RCTs that do not necessarily have the same kind of comparator groups in a ‘network’ of studies.18 In a network meta-analysis (NMA), we can include studies that tested two or more kinds of treatment, without a control group.19 This enables direct comparisons of treatments (similar to pairwise meta-analyses) and also permits indirect comparisons of treatments via the network of treatments.18 19 This enables researchers to rank interventions as comparably more or less effective.

We aimed to conduct a systematic review and NMA on the effectiveness of specific kinds of exercise training in adults with non-specific CLBP. In addition to studying the efficacy of various treatments for pain, we also examined treatment effects on subjective physical function, mental health, analgesic pharmacotherapy use as well as objective trunk muscle strength and endurance. We aimed to compare exercise training with non-exercise treatments such as treatment where the therapist uses ‘hands-on’ treatment (eg, manual therapy) and ‘hands-off’ treatment (eg, education, general practitioner management).

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Network Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-NMA),20 and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017068668).21

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed, piloted and refined based on the method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group,22 and previously published systematic reviews.11–13 An electronic search of MEDLINE, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, EMBASE and CENTRAL was conducted for research published between journal inception to May 2019 using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for ‘pain’ and ‘exercise’ search terms in online supplementary tables 1 and 2. ‘Pain’ and ‘Exercise’ search terms were combined with ‘AND’ and search in ‘All Fields’ with the following limits: MEDLINE (All Adult: 19+ years; RCT; Human), CINAHL (Exclude MEDLINE records; Human, RCTs; Journal Article; All Adult), SPORTDiscus (Academic Journal), EMBASE (RCT; Not MEDLINE; Adult; Article) and CENTRAL (Trials). Additional searches included reviewing the reference lists of previously published systematic reviews identified via the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (search terms: chronic back pain exercise; limits: none) and GoogleScholar (search terms: systematic review chronic back pain exercise; limits: previous 10 years). All results of the search were screened by PJO to exclude duplicates. The titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were independently screened by PJO and SJJMV against inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of those that met these criteria were further independently screened by PJO and SJJMV. All disagreements were adjudicated by NLM.

bjsports-2019-100886supp001.pdf (438.8KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For inclusion, studies were required to be published in a peer-reviewed journal (ie, grey literature excluded) in any language. All other inclusion criteria followed the Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes and Study design framework.20 The population group of interest were adults (≥18 years) with non-specific (no known specific pathology)3 chronic (≥12 weeks)3 low back pain (localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain).4 Therefore, studies were excluded if they examined pain due to or associated with pregnancy, infection, tumour, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformity (eg, scoliosis), inflammatory disorder, radicular syndrome or cauda equine syndrome. Studies that solely recruited patients presurgery or postsurgery were also excluded, as were those that included patients with recurrent (pain-free periods of at least 6 months)4 low back pain. Relevant interventions included the prescription of exercise training alone, without the addition of other treatments (eg, massage, ultrasound or hot and cold therapy) for at least 4 weeks of duration. Specific types of exercise training were determined based on group names chosen by authors and definitions presented in table 1. Non-exercise training treatment comparator groups included true control, therapist hands-on control and therapist hands-off control (table 1). Studies were required to include at least one of the outcome measures of interest: subjective pain intensity (eg, visual analogue scale), subjective physical function (eg, Oswestry Disability Index), objective trunk muscle strength (eg, lumbar extension one-repetition maximum), objective trunk muscle endurance (eg, static lumbar extension hold time), subjective analgesic pharmacotherapy use (eg, prescription medication use) or subjective mental health (eg, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey). In terms of study design, those included were parallel arm (individual-designed or cluster-designed) RCTs that compared an exercise training intervention with either a non-exercise training intervention (including true control) for pairwise comparison or another exercise training intervention for NMA with a total sample size of ≥20 patients (to reduce the risk of publication bias affecting the results).

Table 1.

Definitions of exercise training interventions and non-exercise training controls

| Type | Definition |

| Intervention | |

| Resistance | Exercise training designed to improve the strength, power, endurance and size of skeletal muscles151 |

| Stabilisation/motor control | Exercise training targeting specific trunk muscles in order to improve control and coordination of the spine and pelvis66 |

| Pilates | Exercise training following traditional Pilates principles such as centring, concentration, control, precision, flow and breathing152 |

| Yoga | Exercise training following traditional yoga principles with a physical component153 |

| McKenzie | Exercise training following traditional McKenzie principles such as repeated passive spine movements and sustained positions performed in specific directions154 |

| Flexion | Exercise training consisting of controlled movements in flexion only155 |

| Aerobic | Exercises training such as walking, cycling and jogging in any land-based mode that is designed to improve the efficiency and capacity of the cardiorespiratory system151 |

| Water-based | Exercise training performed in deep or shallow water156 |

| Stretching | Exercise training including muscle lengthening using any of the following methods: passive, static, isometric, ballistic or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation157 |

| Other | Exercise training that does not meet any of the specific types of exercise training mentioned above |

| Multimodal | Two or more of the specific types of exercise training mentioned above (not deemed multimodal if only part of warm up or cool down) |

| Control | |

| True | No intervention provided |

| Therapist hands-on | Treatment including manual therapy, chiropractic, passive physiotherapy, osteopathic, massage or acupuncture |

| Therapist hands-off | Treatment including general practitioner management, education or psychological interventions |

Data extraction

Relevant publication information (ie, author, title, year, journal), study design (eg, two-arm or multi-arm parallel trial, number of assessment time points), number of patients, patient characteristics (eg, age and sex), interventions considered (table 1) and outcome measures (ie, any measure of pain, physical function, muscle strength, muscle endurance, analgesic pharmacotherapy use or mental health) were extracted by two independent assessors (PJO and ST). Extracted outcome data were preintervention and postintervention mean and SD. Data presented as medians or alternate measures of spread were converted to mean and SD.23–25 When only figures were presented (rather than numerical data within text), data were extracted using ImageJ (V.1.50i, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) to measure the length (in pixels) of the axes to calibrate and then the length in pixels from the relevant axis to the data points of interest.26 This method was used for seven studies.27–32When it was not possible to extract the required data, this information was requested from the authors a minimum of three times over a 4-week period. The authors of 24 studies were contacted27 28 30 32–52 and 928 33 35 37 39 41 42 48 49 were able to supply the requested information. Similarity between extracted data from the two independent assessors (PJO and ST) was assessed via an automated code written by DB (written in the ‘R’ statistical environment V.3.4.2, www.r-project.org). Any discrepancies were discussed by PJO and ST with disagreements adjudicated by NLM. Prior to commencing data extraction, this method was piloted on 10 studies chosen at random.

Risk of bias assessment and GRADE

Risk of bias for each individual study was assessed independently by PJO and ST using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool,53 which examined potential selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of patients and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective outcome reporting) and other bias. For each source of bias, studies were classified as having a low, high or unclear (if reporting was not sufficient to assess a particular domain) risk. For example, studies that used a random approach to treatment allocation (eg, random number generator) were classified as low risk for this component of selection bias assessment, while those that did not use a random approach (eg, date of birth assignment) were classified as high risk. As this study involved exercise training interventions, it was not possible to blind patients to treatment allocation; thus, patient blinding was deemed as a high risk of bias for all studies and was not included in the overall risk of bias assessment of each study. All risk of bias disagreements were adjudicated by NLM. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the quality of the evidence behind the ranking of treatments from NMA.54

Statistical analysis

NMA was performed in accordance with current PRISMA NMA guidelines.18 The following steps were applied to all network meta-analyses. Step 1: A network geometry was created to explore comparative relationships among exercises and non-exercise interventions. Step 2: Consistency, whereby the treatment effects estimated from direct comparisons are consistent with those estimated from indirect comparisons, was assessed for the NMA by fitting both a consistency and inconsistency NMA and considering the results from the Wald test for inconsistency. As this test has low power, side-splitting was also conducted to further assess inconsistency. It was anticipated that there would be heterogeneity between studies; therefore, random effects meta-analysis was used. Step 3: If studies investigated multiple groups which we defined as being the same specific type of exercise training or non-exercise training intervention (eg, when exercise training load was examined), the data from the intervention groups were pooled. A minimum of three studies needed to assess an intervention type for it to be included in meta-analysis. When studies were reverse scaled (ie, higher values indicated better outcomes rather than lower values), the mean in each group was multiplied by −1 as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook.53 As all of the outcomes of interest were continuous or ordinal, but could be measured on different scales, standardised mean difference (SMD) was used as the effect estimate. Step 4: Once comparative effectiveness of the interventions was evaluated, interventions were ranked to identify superiority of the interventions. Two approaches to determine the rank order of interventions are surface under cumulative ranking (SUCRA) and the probability of being the best intervention. Superiority was considered as exercise interventions were more effective than no-intervention. Stata reports both the probabilities (ordered from best to worse) and SUCRA; however, SUCRA is considered the more precise estimation of cumulative ranking probabilities.18 55 SUCRA reports the overall probability, based on the ranking of all interventions that a given intervention is among the best treatments.55 Step 5: The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the quality of evidence from NMA.54 To further assess the transitivity assumption, preintervention pain and disability were considered as potential effect modifiers: the degree of baseline pain and disability have been identified56–59 as predictors of prognosis and treatment outcome in non-specific CLBP, whereas fear of movement,60 demographic and physical variables59 61 62 are not consistently associated with treatment outcomes or prognosis. As it is to be expected that not one individual exercise mode will be the best treatment for non-specific CLBP, for the imprecision criterion we did not require that only one exercise approach be clearly the sole best treatment. To check for the presence of bias due to small scale studies, which may lead to publication bias in NMA, a network funnel plot was generated and visually inspected using the criterion of symmetry. Network meta-analyses were conducted in Stata 15.0 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA.).

Pairwise random-effects meta-analysis was also conducted to compare exercise training-based and non-exercise training-based treatments. Heterogeneity was assessed for all pairwise comparisons using the I2 statistic and publication bias using the p-value of Egger’s test. Pairwise meta-analyses were implemented in the ‘R’ statistical environment (V.3.4.0, www.r-project.org).

Results

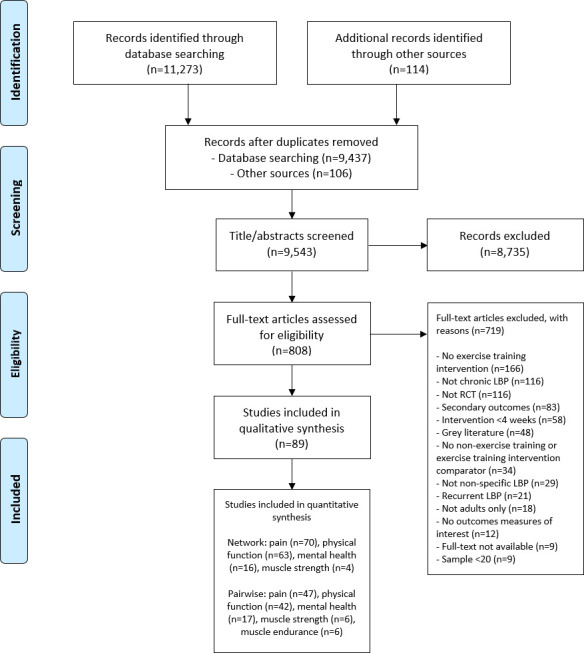

The flow of the systematic review is presented in figure 1. The electronic database search yielded 9437 records after duplicates were removed. Additionally, 106 records were located via the reference lists of 18 previously published systematic reviews.11 12 14–17 63–74 The examination of titles and abstracts resulted in the retrieval of 808 full-text records. Following full-text review, 89 studies were included in qualitative analysis.23–25 27–35 37 38 40 41 43 45–47 49–51 75–140 Of these studies, 55 (62%)24 25 27–29 31 32 35 37 41 49 77 78 80 83–87 92–95 98–108 110–113 115–117 119–121 123 125 126 128 130 132 133 135 138–140 were deemed eligible for the pairwise meta-analyses and 82 (92%)23–25 27–33 35 37 38 41 47 49 75–140 were, in total, suitable for the network meta-analyses.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the search process for studies examining the efficacy of exercise training in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain. LBP, low back pain; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Study characteristics

A detailed summary of each included study (n=89)23–25 27–35 37 38 40 41 43 45–47 49–51 75–140 is presented in online supplementary table 3. Sample size ranged from 20 to 240 patients (mean age range, 20–70 years; one study38 did not report age) and study duration ranged from 4 to 24 weeks. Eleven studies (12%)27 28 30 50 95 105 106 110 120 121 123 and 16 studies (18%)29 31 38 43 47 49 80 93 94 116 118 119 122 124 135 139 only included females and males, respectively, whereas the remainder included both sexes. Twelve studies (13%) did not report sex.40 75 76 82 89 96 97 103 104 111 115 136 The average duration of pain reported at baseline ranged from 12 to 725 weeks (0.2–14.0 years) and average pain intensity was 21–79 points when normalised on a 100-point scale. Notably, 13 studies (15%)29 34 45 50 93 95 98 120 122 124 126 127 139 did not report a measure of baseline pain intensity.

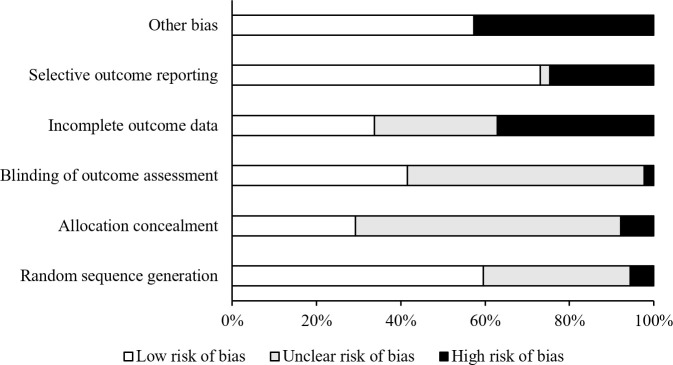

Among the 89 studies included (patients: n=5578), there were 131 exercise training interventions (patients: n=3924) and 59 non-exercise training comparators (patients: n=1654; online supplementary table 3). Exercise training interventions included: aerobic (studies: n=5, patients: n=127),33 83 100 113 127 other (studies: n=12, patients: n=290),77 87 96 103 108 112 116 119 120 122 135 140 McKenzie (studies: n=7, patients: n=114),40 47 76 94 97 111 120 multimodal (studies: n=23, patients: n=756),23–25 32 38 40 45 50 75 82 88 91 99 102 109 114 118 124 129 131 134 137 138 Pilates (studies: n=13, patients: n=350),23 27 29 30 33 34 51 86 94 105 111 131 139 resistance (studies: n=12, patients: n=472),43 78 79 81 90 92 93 100 101 127 130 134 stabilisation/motor control (studies: n=39, patients: n=1062),25 28 38 43 49 50 75 76 79–82 84 85 89–91 95–98 103–106 108–110 115 118 122–125 128 129 134 136 140 stretching (studies: n=8, patients: n=222),31 37 89 107 117 121 126 136 water-based (studies: n=6, patients: n=144)37 41 45 88 120 137 and yoga (studies: n=6, patients: n=387).35 46 114 126 132 133 Non-exercise training interventions included: true control (studies: n=33, patients: n=733),27 28 31 34 35 37 41 49 77 78 80 86 87 93–95 100 104 105 108 110–112 115–117 120 121 125 135 138–140 therapist hands-on control (studies: n=14, patients: n=506)25 30 47 83 85 92 98 99 101 106 113 123 128 130 and therapist hands-off control (studies: n=12, patients: n=415).24 29 32 46 51 84 102 107 119 126 132 133 The frequency of exercise training per week ranged from 1 to 7 days, whereas therapist hands-on controls were performed on 0.3–5 days per week. The risk of bias assessment for each individual study is presented in online supplementary table 4 and summary data in figure 2. Overall, studies tended to exhibit a low risk of selective outcome reporting (60%), random sequence generation (60%), other bias (57%), but not allocation concealment (29%), blinding of patients and personnel (0%), blinding of outcome assessment (42%) and incomplete outcome data (34%).

Figure 2.

Percentage of studies examining the efficacy of exercise training in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain with low, unclear and high risk of bias for each feature of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. It is not possible to truly blind patients to treatment allocation in exercise training trials; thus, this was not included in the overall risk of bias assessment of each study.

Pain

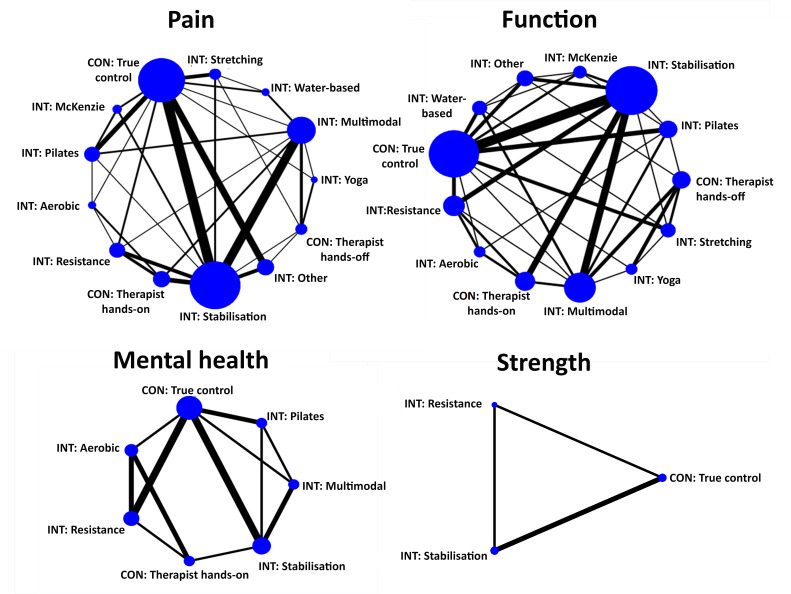

Seventy studies23–25 27 28 31–33 35 37 38 41 49 75–92 94 96 97 99–119 121 123 125 128–138 140 assessed pain and were eligible for NMA of pain (figure 3). The results from the consistency NMA provided evidence that when compared with true control, Pilates (p<0.001), aerobic (p=0.006), stabilisation/motor control (p<0.001), multimodal (p<0.001), resistance (p=0.002) and ‘other’ (p<0.001) exercise training all result in lower pain following intervention (table 2). The results of the consistency model indicated that Pilates (SUCRA: 100%), aerobic (SUCRA: 80%) and stabilisation/motor control (80%) exercise training were among the best interventions for pain. True control (SUCRA: 10%) and therapist hands-off control (SUCRA: 10%) were most likely to be the least effective. The Wald test for inconsistency in the network was not significant (χ²=40.7, p=0.057; see also online supplementary table 5). The comparison-adjusted funnel plot did not provide evidence for apparent publication bias (online supplementary figure 1). Data from pairwise meta-analysis gave evidence for considerable heterogeneity (min I2=29%, median I2=90%, max I2=95%; online supplementary table 6). The quality of the evidence for the ranks of the treatment was low (table 3). Pairwise meta-analysis provided evidence that exercise training (all) was more effective than therapist hands-off control (SMD (95% CI): −1.06 (–1.62 to –0.51), p<0.001, I2=87%, studies: n=8) and therapist hands-on control (SMD (95% CI): −0.57 (–1.05 to –0.08), p=0.023, I2=93%, studies: n=11; online supplementary table 6).

Figure 3.

Network meta-analysis maps of studies examining the efficacy of exercise training in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain on pain, physical function, mental health and muscle strength. CON: non-exercise control, INT: exercise training intervention. The size of the nodes relates to the number of participants in that intervention type and the thickness of lines between interventions relates to the number of studies for that comparison.

Table 2.

Network meta-analysis consistency models for pain, physical function, mental health and muscle strength in studies examining the efficacy of exercise training in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain

| Treatment type | Comparison to ‘no treatment’ | Likelihood (%) of being… | SUCRA (%) | ||

| Pooled SMD (95% CI) | P value | Best | Worst | ||

| Pain | |||||

| CON: True control | – | – | 0.0 | 37.0 | 10 |

| INT: Aerobic | −1.41 (−2.43 to −0.40) | 0.006 | 16.6 | 0.2 | 80 |

| INT: Other | −1.07 (−1.67 to −0.47) | <0.001 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 60 |

| CON: Hands-off | 0.09 (−0.71 to 0.89) | 0.827 | 0.0 | 56.6 | 10 |

| CON: Hands-on | −0.69 (−1.39 to 0.01) | 0.054 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 30 |

| INT: Water-based | −0.91 (−1.85 to 0.03) | 0.057 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 50 |

| INT: McKenzie | −0.81 (−1.74 to 0.11) | 0.083 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 40 |

| INT: Multimodal | −0.99 (−1.55 to −0.44) | <0.001 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 50 |

| INT: Pilates | −1.86 (−2.54 to −1.19) | <0.001 | 68.9 | 0.0 | 100 |

| INT: Resistance | −1.14 (−1.86 to −0.42) | 0.002 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 60 |

| INT: Stabilisation | −1.31 (−1.75 to −0.87) | <0.001 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 80 |

| INT: Stretching | −0.62 (−1.38 to 0.13) | 0.107 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 30 |

| INT: Yoga | −0.99 (−2.00 to 0.03) | 0.056 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 50 |

| Physical function | |||||

| CON: True control | – | – | 0.0 | 59.4 | 0 |

| INT: Aerobic | −0.85 (−1.62 to −0.09) | 0.029 | 9.3 | 1.0 | 60 |

| INT: Other | −0.72 (−1.32 to −0.13) | 0.017 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 50 |

| CON: Hands-off | −0.31 (−0.94 to 0.32) | 0.340 | 0.0 | 12.7 | 20 |

| CON: Hands-on | −0.49 (−1.08 to 0.10) | 0.102 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 30 |

| INT: Water-based | −1.00 (−1.67 to −0.32) | 0.004 | 18.1 | 0.1 | 70 |

| INT: McKenzie | −0.27 (−1.02 to 0.47) | 0.471 | 0.4 | 20.0 | 20 |

| INT: Multimodal | −0.75 (−1.23 to −0.27) | 0.002 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 50 |

| INT: Pilates | −0.92 (−1.48 to −0.36) | 0.001 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 70 |

| INT: Resistance | −1.14 (−1.71 to −0.56) | <0.001 | 27.5 | 0.0 | 80 |

| INT: Stabilisation | −1.13 (−1.53 to −0.74) | <0.001 | 18.7 | 0.0 | 80 |

| INT: Stretching | −0.55 (−1.20 to 0.10) | 0.095 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 40 |

| INT: Yoga | −0.92 (−1.66 to −0.18) | 0.015 | 13.9 | 0.1 | 70 |

| Mental health | |||||

| CON: True control | – | – | 0.0 | 68.1 | 10 |

| INT: Aerobic | −1.18 (−2.20 to −0.15) | 0.024 | 32.9 | 0.2 | 80 |

| CON: Hands-on | −0.31 (−1.31 to 0.70) | 0.552 | 0.2 | 26.6 | 20 |

| INT: Multimodal | −0.75 (−1.61 to 0.11) | 0.086 | 8.3 | 2.8 | 50 |

| INT: Pilates | −0.84 (−1.71 to 0.02) | 0.056 | 13.4 | 1.7 | 60 |

| INT: Resistance | −1.26 (−2.10 to −0.41) | 0.003 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 80 |

| INT: Stabilisation | −0.78 (−1.49 to −0.07) | 0.031 | 5.2 | 0.5 | 50 |

| Muscle strength | |||||

| CON: True control | – | – | 8.0 | 65.6 | 20 |

| INT: Resistance | 0.18 (−0.27 to 0.64) | 0.427 | 42.9 | 17.0 | 60 |

| INT: Stabilisation | 0.21 (−0.28 to 0.69) | 0.399 | 49.1 | 17.4 | 70 |

The significance of the difference of the effect estimate (SMD) compared with ‘no treatment’ control is indicated by the p value. The likelihood of being the best or worst treatment is indicated as a percentage and this is best summarised by the SUCRA which ranges from 0% to 100%. The SUCRA measure assesses the likely ranks of all treatments and the higher the SUCRA percentage, the more likely that therapy is one of the most effective.

CON, control; INT, exercise training intervention; SMD, standardised mean difference; SUCRA, surface under the cumulative ranking curves.

Table 3.

Summary of confidence in ranking of treatments for outcomes (GRADE approach) in studies examining the efficacy of exercise training in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain

| Outcome | Confidence | Reason for downgrade |

| Pain | Low | Study limitations,* Inconsistency† |

| Physical function | Low | Study limitations,‡ Inconsistency† |

| Mental health | Low | Study limitations,§ Inconsistency† |

| Muscle strength | Low | Study limitations,¶ Imprecision** |

*Evidence came from 91% unclear to high risk of bias studies. See online supplementary figure 2 for additional data on the assessment of transitivity.

†High heterogeneity or inconsistency present.

‡Evidence came from 89% unclear to high risk of bias studies.

§Evidence came from 88% unclear to high risk of bias studies.

¶All evidence from unclear to high risk of bias studies.

**Imprecision of clear most or least favoured treatments.

Physical function

Sixty-three studies23–25 28–30 32 33 35 37 41 47 49 76 78 80 81 83 85 87–90 92 93 95–103 105–107 109–115 117–122 124–129 131–134 137–139 were eligible for the NMA of subjective physical function (figure 3). The results from the consistency NMA provide evidence that when compared with true control, stabilisation/motor control (p<0.001), resistance (p<0.001), water-based (p=0.004), Pilates (p=0.001), yoga (p=0.015), multimodal (p=0.002), aerobic (p=0.029) and ‘other’ (p=0.017) exercise training resulted in improved physical function following intervention (table 2). The results showed that stabilisation/motor control (SUCRA: 80%) and resistance (SUCRA: 80%) exercise training had the highest probability of being the best treatments, followed by water-based (SUCRA: 70%), Pilates (SUCRA: 70%) and yoga (SUCRA: 70%) exercise training. True control (SUCRA: 0%) and therapist hands-off control (SUCRA: 20%) were most likely to be the least effective. There was evidence of inconsistency in the network (χ²=46.3, p=0.049; online supplementary table 5). The comparison-adjusted funnel plot did not provide evidence for apparent publication bias (online supplementary figure 1). Data from pairwise meta-analysis gave evidence for considerable heterogeneity (min I2=0%, median I2=84%, max I2=97%; online supplementary table 7). The quality of the evidence for the ranks of the treatment was low (table 3). Pairwise meta-analysis showed that exercise training (all) was more effective than therapist hands-off control (SMD (95% CI): −0.46 (–0.78 to –0.14), p=0.010, I2=73%, studies: n=9) and therapist hands-on control (SMD (95% CI): −0.55 (–0.94 to –0.15), p=0.010, I2=88%, studies: n=10; online supplementary table 7).

Mental health

Twenty-four studies32 37 78 83 86 88 93 100 101 103 105 107 109 112–115 125 127–129 131 132 138 assessed mental health outcomes and 16 studies78 83 86 93 100 101 105 109 113 115 125 127–129 131 138 were eligible for the NMA of mental health (figure 3). The results from the consistency NMA showed that resistance (p=0.003), aerobic (p=0.024) and stabilisation/motor control (p=0.031) exercise training resulted in improved mental health following intervention compared with true control (table 2). The results indicated that resistance (SUCRA: 80%) and aerobic (SUCRA: 80%) exercise training had the highest probability of being the best interventions for mental health. True control (SUCRA: 10%) and therapist hands-on control (SUCRA: 20%) were most likely to be the least effective. There was evidence of inconsistency in the network (χ²=54.8, p<0.001; online supplementary table 5). The comparison-adjusted funnel plot did not provide evidence for apparent publication bias (online supplementary figure 1). The quality of the evidence for the ranks of the treatment was low (table 3). Data from pairwise meta-analysis presented evidence that exercise training (all) improved mental health in comparison to therapist hands-off control (SMD (95% CI): −0.53 (–0.88 to –0.18), p=0.003, I2=26%, studies: n=3) and therapist hands-on control (SMD (95% CI): −0.79 (–1.56 to –0.03), p=0.042, I2=92%, studies: n=4; online supplementary table 8).

Muscle strength

Eight studies49 80 93 116 130 134–136 assessed trunk muscle strength as an outcome measure and four studies49 80 93 134 were eligible for the NMA of objectively measured trunk muscle strength (figure 3). The results from the consistency NMA did not give evidence for a significant impact of resistance or stabilisation/motor control exercise training on muscle strength (table 2). Stabilisation/motor control (SUCRA: 70%) and resistance (SUCRA: 80%) exercise training were most likely to be the best interventions for increasing muscle strength. There was no evidence of inconsistency in the network (χ²=0.1, p=0.750; online supplementary table 5). The comparison-adjusted funnel plot did not provide evidence for apparent publication bias (online supplementary figure 1). The quality of the evidence for the ranks of the treatment was low (table 3). Pairwise meta-analysis presented evidence that exercise training (all) improved muscle strength compared with control (all) only (SMD (95% CI): 0.29 (0.00 to 0.58), p=0.050, I2=14%, studies: n=6; online supplementary table 9).

Muscle endurance

Eight studies23 27 28 100 106 127 137 139 assessed trunk muscle endurance as an outcome measure, but NMA was not possible for objectively measured trunk muscle endurance as there were only two intervention types (true control and Pilates exercise training) with more than two studies for this outcome. Pairwise meta-analysis presented evidence that exercise training (seven exercise training types (aerobic (n=1), other (n=1), McKenzie (n=1), Pilates (n=2), resistance (n=1), stretching (n=1), water-based (n=1)) in five studies) improved muscle endurance compared with true control (SMD (95% CI): 1.57 (0.69 to 2.45), p<0.001, I2=87%, studies: n=5; online supplementary table 10).

Analgesic pharmacotherapy use

Only four studies45 107 132 133 reported analgesic pharmacotherapy use as an outcome and these data were not reported in a format that permitted further analysis (ie, measured at follow-up only, variance not reported and examined as a categorical variable).

Discussion

In this first NMA of exercise training in CLBP, we found that, depending on outcome of interest, Pilates (for pain), resistance and aerobic (for mental health) and resistance and stabilisation/motor control (for physical function) exercise training were the most effective interventions. The effect of stretching and McKenzie exercise on pain and self-report physical function did not significantly differ to no-intervention control. Limitations on these findings was that the quality of the evidence was low according to GRADE criteria. True control was the least effective treatment for all outcomes, followed by therapist hands-off for pain and physical function and therapist hands-on treatment for mental health.

Reducing pain

It is unlikely that one kind of exercise training is the single best approach to treating non-specific CLBP. Our study provides evidence that ‘active therapies’, such as Pilates, resistance, stabilisation/motor control and aerobic exercise training, where the patient is guided, actively encouraged to move and exercise in a progressive fashion are the most effective. This notion is further supported by our findings that true control, as well as therapist hands-on and -off, were most likely to be the least effective treatments. The evidence for the therapeutic use of exercise training for the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain (eg, non-specific CLBP) continues to grow as the field of pain science moves towards the biopsychosocial approach.141 This approach considers both patient needs and clinician competencies and contends that exercise training interventions should be individualised based on patient presentation, goals and modality preferences.141 The results of this NMA can be used by clinicians to help guide their selection of exercise interventions to patients with non-specific CLBP.

As mentioned above, our NMA for reducing pain identified Pilates, stabilisation/motor control and aerobic exercise training as the three treatments most likely to be the best. If the pooled SMD of these comparisons are considered as effect sizes, all three of these findings are large (ie, >0.8).142 These interpretations limit the comparisons between these interventions in terms predictive efficacy in the therapeutic setting, as well as determination of whether or not these findings reflect clinically meaningful changes. Considering transformation to more commonly used clinical outcomes in an alternative suggestion in the Cochrane Handbook53 and was previously considered for the visual analogue scale for pain intensity using a SD of 20.7 Using this approach suggests that Pilates (−37 points), stabilisation/motor control (−26 points) and aerobic exercise training (−28 points) can all reduce pain intensity by a clinically meaningful amount (ie, −20 points).143 These three treatments differed to therapist hands-on treatment (+2 points) and therapist hands-off treatment (−14 points) by a clinically significant extent. While the differences among these three likely best exercise treatments fell below this threshold, Pilates and stabilisation/motor control differed by 20 points or more to stretching (−12 points) and McKenzie (−16 points) exercise. Overall, there is low-quality evidence that there may be a differential effect between specific modes of exercise for impacting pain intensity in non-specific CLBP.

Improving physical function

If we focus our attention beyond the outcome of pain, our study suggested that resistance and stabilisation/motor control exercise training forms had the highest probably of improving physical function (ie, disability as measured by questionnaire). In addition to these modalities, large effect sizes (ie, >0.8)142 in favour of reductions in disability were also observed for yoga, Pilates, water-based and aerobic exercise training. These suggest that a range of distinctively different exercise training modalities may reduce disability in patients with non-specific CLBP; clinicians who prescribe exercise training should work with patients to identify a modality suitable for their capabilities and interests to increase the likelihood of efficacy. An 11-point reduction on the Oswestry Disability Index is considered clinically significant.144 On the basis of the preintervention data from the included studies the typical SD of the Oswestry Disability Index is 12 (online supplementary table 11). Converting the estimated effect sizes in table 2 to Oswestry Disability Index units, yoga (−11 percentage points), Pilates (−11 percentage points), water-based (−12 percentage points), resistance (−14 percentage points) and stabilisation (−14 percentage points) exercise training showed a clinically significant change in self-report physical function compared with true control. This was not observed for McKenzie exercise (−3 percentage points) and stretching exercise (−7 percentage points).

Improving mental health

Aerobic and resistance exercise training emerged from our NMA as the most likely to improve mental health based on large effect sizes (ie, >0.8).142 These analyses were limited by the lower number of studies when compared with other measures, such as pain and physical function. Only 16 studies, including 5 exercise treatments and 2 control interventions, were eligible for NMA. Mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety, are seen in 36% and 29% of people with CLBP, respectively.145 Given these comorbidities are associated with pain intensity,146 we suggest that future exercise training studies report these measures. We also suggest that standardised assessment tools are considered, as the majority of studies included in the current study assessed mental health via different tools.

What is the role for trunk muscles in treatment?

Trunk muscle strength and endurance are known risk factors for future back pain.147 Despite the clinical relevance of this outcome, only four studies,49 80 93 134 all of which examined trunk muscle strength, were eligible for the NMA. While the analysis provided low-quality evidence that resistance and stabilisation exercise training could improve trunk muscle strength, the effect sizes of these interventions versus no intervention control were not significant. NMA was not possible for trunk muscle endurance. Trunk muscle strength and endurance have the potential to be objective outcome measures to differentiate treatment approaches and future trials should include these measures to elucidate the potential efficacy of exercise training.

Use of analgesics as an outcome of clinical trials

Analgesic pharmacotherapy use is of clinical relevance and directly relevant to the affected individual, yet only four studies45 107 132 133 reported analgesic pharmacotherapy use and none were eligible for meta-analysis. We recommend that the use of analgesic pharmacotherapy be considered as an outcome in future RCTs.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included that searches were not limited by publication date or language, and studies included were not restricted to a specific type of intervention or comparator. Considering numerous outcome measures of clinical relevance in those with non-specific CLBP also strengthened this study; in particular, those measures that pertain to pharmacotherapy use and mental health are often omitted despite the high prevalence of mental health issues and analgesic use in this susceptible population group.148

We report several limitations. We did not consider variations in safety between exercise modalities. Underreporting of adverse events is a known149 issue associated with the reporting of exercise training studies. Nonetheless, there is low-quality evidence150 that exercise does not cause serious harms and that when adverse events are reported, they are limited to muscle soreness and increased pain.

A high proportion (78%) of studies had a high risk of bias for at least one type of bias, even after excluding performance bias, which was high for all studies due to the inability to blind patients to exercise training. Most included studies (76%) provided insufficient information to appropriately determine risk of bias, leaving only seven studies (8%) at low risk of bias. In an attempt to overcome this limitation, we applied the GRADE approach, which suggests that with higher quality evidence, one can be more confident that the effect estimates are the true effects and additional evidence is less likely to result in a change in the estimate. Given that the levels of evidence were low, it is possible that the effect sizes and rankings of the treatments will change as more evidence is obtained.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provided evidence that various exercise training approaches are effective and should be incorporated into usual care for adults with non-specific CLBP due to its potential for improving pain, physical function, muscle strength and mental health. Importantly, exercise training was more effective than hands-on therapist treatment for reducing pain and improving physical function and mental health. However, despite our identifying numerous studies that examined exercise training, we were unable to determine whether exercise training improved trunk muscle strength, trunk muscle endurance and reducing analgesic pharmacotherapy use; these outcomes were not often reported.

Examination of specific kinds of exercise training was limited by the number of studies available and variability in reporting. There was low-quality evidence that true control (ie, no intervention), therapist hands-off treatment (eg, general practitioner management, education or psychological interventions) and therapist hands-on (eg, manual therapy, chiropractic or passive physiotherapy) are most likely to be ineffective interventions for non-specific CLBP. There was low-quality evidence that stretching and McKenzie exercise training were not effective for pain or physical function in people with non-specific CLBP. Finally, there was low-quality evidence that Pilates, stabilisation/motor control, resistance and aerobic exercise training were able to improve pain, physical function and mental health in people with non-specific CLBP. Collectively, our findings provide evidence that active exercise therapies may be an effective treatment of non-specific CLBP in adults.

What is already known.

Worldwide, low back pain is the leading cause of disability and most common non-communicable disease.

Exercise training is an effect treatment for non-specific chronic low back pain, but the best mode of exercise training is unknown.

What are the new findings.

Pilates, stabilisation/motor control, aerobic and resistance exercise training are possibly the most effective treatments, pending outcome of interest, for adults with non-specific chronic low back pain.

Exercise training may also be more effective than hand-on therapist treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Deakin University’s Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition Statistics for advice during study conception.

Footnotes

Twitter: @PatrickOwenPhD, @_clintmiller, @NiamhMundell, @S1_Verswijveren, @ScottTags, @BelavySpine

Contributors: Secured funding: CM, DB. Study conception: PO, CM, HB, DB. Screening: PO, NM, SV. Extraction: PO, NM, ST. Statistical analyses: SB, DB. Drafted manuscript: PO, DB. Approved final manuscript: All.

Funding: This project was funded by Musculoskeletal Australia (formerly MOVE muscle, bone and joint health; CONTR2017/00399).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. . The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. . Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin C-WC, et al. . An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 2010;19:2075–94. 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al. . Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 2006;1:S169–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. . The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:769–81. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA, et al. . Length of disability and cost of work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity. J Occup Environ Med 1998;40:261–9. 10.1097/00043764-199803000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-Specific low back pain. The Lancet 2017;389:736–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ebadi S, Henschke N, Nakhostin Ansari N, et al. . Therapeutic ultrasound for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;46 10.1002/14651858.CD009169.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, et al. . Superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;47 10.1002/14651858.CD004750.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Furlan AD, Brosseau L, Imamura M, et al. . Massage for low-back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine 2002;27:1896–910. 10.1097/00007632-200209010-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:776–85. 10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Searle A, Spink M, Ho A, et al. . Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:1155–67. 10.1177/0269215515570379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, et al. . Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:193–204. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lim ECW, Poh RLC, Low AY, et al. . Effects of Pilates-based exercises on pain and disability in individuals with persistent nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011;41:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saragiotto BT, Maher CG, Yamato TP, et al. . Motor control exercise for nonspecific low back pain: a cochrane review. Spine 2016;41:1284–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rackwitz B, de Bie R, Limm H, et al. . Segmental stabilizing exercises and low back pain. What is the evidence? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil 2006;20:553–67. 10.1191/0269215506cr977oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, et al. . Yoga treatment for chronic non‐specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shim S, Yoon B-H, Shin I-S, et al. . Network meta-analysis: application and practice using Stata. Epidemiol Health 2017;39:e2017047 10.4178/epih.e2017047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JPA. Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f2914 10.1136/bmj.f2914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. . The prisma extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Owen PJ, Miller CT, Mundell NL, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic back pain: prospero [CRD42017068668], 2017. Available: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017068668

- 22. Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, et al. . 2015 updated method guideline for systematic reviews in the Cochrane back and neck group. Spine 2015;40:1660–73. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mostagi FQRC, Dias JM, Pereira LM, et al. . Pilates versus general exercise effectiveness on pain and functionality in non-specific chronic low back pain subjects. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2015;19:636–45. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shirado O, Doi T, Akai M, et al. . Multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of home-based exercise on patients with chronic low back pain: the Japan low back pain exercise therapy study. Spine 2010;35:E811–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Latimer J, et al. . Comparison of general exercise, motor control exercise and spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. Pain 2007;131:31–7. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vucic K, Jelicic Kadic A, Puljak L. Survey of Cochrane protocols found methods for data extraction from figures not mentioned or unclear. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:1161–4. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kliziene I, Sipaviciene S, Vilkiene J, et al. . Effects of a 16-week Pilates exercises training program for isometric trunk extension and flexion strength. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2017;21:124–32. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kofotolis N, Kellis E. Effects of two 4-week proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation programs on muscle endurance, flexibility, and functional performance in women with chronic low back pain. Phys Ther 2006;86:1001–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patti A, Bianco A, Paoli A, et al. . Pain perception and Stabilometric parameters in people with chronic low back pain after a Pilates exercise program. Medicine 2016;95:e2414 10.1097/MD.0000000000002414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shahrjerdi S, Golpayegani M, Daghaghzadeh A, et al. . The effect of Pilates-based exercises on pain, functioning and lumbar lordosis in women with non-specific chronic low back pain and hyperlordosis. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci Health Serv 2014;22:120–31. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soares P, Cabral V, Mendes M, et al. . Effects of school-based exercise program of posture and global postural reeducation on the range of motion and pain levels in patients with chronic low back pain. Rev Andaluza Med Dep 2016;9:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Machado LAC, Azevedo DC, Capanema MB, et al. . Client-centered therapy vs exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: a pilot randomized controlled trial in Brazil. Pain Med 2007;8:251–8. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brooks C, Kennedy S, Marshall PWM. Specific trunk and general exercise elicit similar changes in anticipatory postural adjustments in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine 2012;37:E1543–50. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31826feac0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cruz-Díaz D, Romeu M, Velasco-González C, et al. . The effectiveness of 12 weeks of Pilates intervention on disability, pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:1249–57. 10.1177/0269215518768393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Groessl EJ, Liu L, Chang DG, et al. . Yoga for military veterans with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:599–608. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gudavalli MR, Cambron JA, McGregor M, et al. . A randomized clinical trial and subgroup analysis to compare flexion–distraction with active exercise for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2006;15:1070–82. 10.1007/s00586-005-0021-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keane LG. Comparing AquaStretch with supervised land based stretching for chronic lower back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2017;21:297–305. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Young KJ, Je CW, Hwa ST. Effect of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation integration pattern and Swiss ball training on pain and balance in elderly patients with chronic back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:3237–40. 10.1589/jpts.27.3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mannion A, Dvorak J, Taimela S M. Chronic low back pain: a comparison of three active therapies. Man Med Osteo Med 2001;4:170–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mbada CE, Ayanniyi O, Ogunlade SO, et al. . Influence of Mckenzie protocol and two modes of endurance exercises on health-related quality of life of patients with long-term mechanical low-back pain. Pan Afr Med J 2014;17 10.11604/pamjs.supp.2014.17.1.2950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McIlveen B, Robertson VJ. A randomised controlled study of the outcome of hydrotherapy for subjects with low back or back and leg pain. Physiotherapy 1998;84:17–26. 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)65898-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moon HJ, Choi KH, Kim DH, et al. . Effect of lumbar stabilization and dynamic lumbar strengthening exercises in patients with chronic low back pain. Ann Rehabil Med 2013;37:110–7. 10.5535/arm.2013.37.1.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palekar T, Das A, Pagare V. A comparative study between core stabilization and superficial strengthening exercises for the treatment of low back pain in two wheeler riders. Int J Pharm Bio Sci 2015;6:B168–76. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Petersen T, Christensen R, Juhl C. Predicting a clinically important outcome in patients with low back pain following McKenzie therapy or spinal manipulation: a stratified analysis in a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:74 10.1186/s12891-015-0526-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saggini R, Cancelli F, Bonaventura D, et al. . Efficacy of two micro-gravitational protocols to treat chronic low back pain associated with discal lesions: a randomized controlled trial 2004;40:311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Saper RB, Lemaster C, Delitto A, et al. . Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: a randomized noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shen YC, Shen YX. Effect of eperisone hydrochloride on the paraspinal muscle blood flow in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled observation. J Clin Rehabil Tis Eng Res 2009;13:1293–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, et al. . Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Steele J, Bruce-Low S, Smith D, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of limited range of motion lumbar extension exercise in chronic low back pain. Spine 2013;38:1245–52. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318291b526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ui-Cheol J, Jae-Heon SIM, Cheol-Yong KIM, et al. . The effects of gluteus muscle strengthening exercise and lumbar stabilization exercise on lumbar muscle strength and balance in chronic low back pain patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:3813–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Valenza MC, Rodríguez-Torres J, Cabrera-Martos I, et al. . Results of a Pilates exercise program in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2017;31:753–60. 10.1177/0269215516651978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yongho CHO. Effects of tai chi on pain and muscle activity in young males with acute low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2014;26:679–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0: the Cochrane collaboration, 2011. Available: http://handbook.cochrane.org

- 54. Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, et al. . Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e99682 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mbuagbaw L, Rochwerg B, Jaeschke R, et al. . Approaches to interpreting and choosing the best treatments in network meta-analyses. Syst Rev 2017;6:79 10.1186/s13643-017-0473-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boonstra AM, Reneman MF, Waaksma BR, et al. . Predictors of multidisciplinary treatment outcome in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:1242–50. 10.3109/09638288.2014.961657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cecchi F, Pasquini G, Paperini A, et al. . Predictors of response to exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: result of a prospective study with one year follow-up. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2014;50:143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Steffens D, Hancock MJ, Maher CG, et al. . Prognosis of chronic low back pain in patients presenting to a private community-based group exercise program. Eur Spine J 2014;23:113–9. 10.1007/s00586-013-2846-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. van der Hulst M, Vollenbroek-Hutten MMR, IJzerman MJ. A systematic review of sociodemographic, physical, and psychological predictors of multidisciplinary Rehabilitation—or, back school treatment outcome in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine 2005;30:813–25. 10.1097/01.brs.0000157414.47713.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, et al. . Fear-avoidance beliefs-a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2658–78. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borge JA, Leboeuf-Yde C, Lothe J. Prognostic values of physical examination findings in patients with chronic low back pain treated conservatively: a systematic literature review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001;24:292–5. 10.1067/mmt.2001.114361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Michaelson P, Sjölander P, Johansson H. Factors predicting pain reduction in chronic back and neck pain after multimodal treatment. Clin J Pain 2004;20:447–54. 10.1097/00002508-200411000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Brox JI, Storheim K, Grotle M, et al. . Systematic review of back schools, brief education, and fear-avoidance training for chronic low back pain. Spine J 2008;8:948–58. 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.07.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, et al. . Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother 2006;52:79–88. 10.1016/S0004-9514(06)70043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, et al. . Back schools for acute and subacute non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Macedo LG, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. . Motor control exercise for persistent, nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2009;89:9–25. 10.2522/ptj.20080103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. May S, Johnson R. Stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2008;94:179–89. 10.1016/j.physio.2007.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Poquet N, Lin C-WC, Heymans MW, et al. . Back schools for acute and subacute non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;170 10.1002/14651858.CD008325.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJ, et al. . Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, et al. . Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology 2008;47:670–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schaafsma FG, Whelan K, van der Beek AJ, et al. . Physical conditioning as part of a return to work strategy to reduce sickness absence for workers with back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;49 10.1002/14651858.CD001822.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Slade SC, Keating JL. Trunk-strengthening exercises for chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006;29:163–73. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Walker BF, French SD, Grant W, et al. . Combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;29 10.1002/14651858.CD005427.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Waller B, Lambeck J, Daly D. Therapeutic aquatic exercise in the treatment of low back pain: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:3–14. 10.1177/0269215508097856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Akbari A, Khorashadizadeh S, Abdi G. The effect of motor control exercise versus general exercise on lumbar local stabilizing muscles thickness: randomized controlled trial of patients with chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2008;21:105–12. 10.3233/BMR-2008-21206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ali S, Ali S, Memon K. Effectiveness of core stabilization exercises versus McKenzie's exercises in chronic lower back pain. Med Forum Month 2013;24:82–5. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Arampatzis A, Schroll A, Catalá MM, et al. . A random-perturbation therapy in chronic non-specific low-back pain patients: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol 2017;117:2547–60. 10.1007/s00421-017-3742-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Areeudomwong P, Wongrat W, Neammesri N, et al. . A randomized controlled trial on the long-term effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation training, on pain-related outcomes and back muscle activity, in patients with chronic low back pain. Musculoskeletal Care 2017;15:218–29. 10.1002/msc.1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bae C-R, Jin Y, Yoon B-C, et al. . Effects of assisted sit-up exercise compared to core stabilization exercise on patients with non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2018;31:871–80. 10.3233/BMR-170997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Byoung-Hwan OH, Hong-Hyun KIM, Cheol-Yong KIM, et al. . Comparison of physical function according to the lumbar movement method of stabilizing a patient with chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:3655–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Cai C, Yang Y, Kong PW. Comparison of lower limb and back exercises for runners with chronic low back pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017;49:2374–84. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chae-Woo LEE, Kak H, In-Sil LEE. The effects of combination patterns of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and ball exercise on pain and muscle activity of chronic low back pain patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2014;26:93–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chatzitheodorou D, Kabitsis C, Malliou P, et al. . A pilot study of the effects of high-intensity aerobic exercise versus passive interventions on pain, disability, psychological strain, and serum cortisol concentrations in people with chronic low back pain. Phys Ther 2007;87:304–12. 10.2522/ptj.20060080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cho H-young, Kim E-hye, Kim J. Effects of the core exercise program on pain and active range of motion in patients with chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2014;26:1237–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Costa LOP, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. . Motor control exercise for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phys Ther 2009;89:1275–86. 10.2522/ptj.20090218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Cruz-Díaz D, Bergamin M, Gobbo S, et al. . Comparative effects of 12 weeks of equipment based and MAT Pilates in patients with chronic low back pain on pain, function and transversus abdominis activation. A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 2017;33:72–7. 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. del Pozo-Cruz B, Hernandez Mocholi MA, Adsuar JC, et al. . Effects of whole body vibration therapy on main outcome measures for chronic non-specific low back pain: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:689–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Dundar U, Solak O, Yigit I, et al. . Clinical effectiveness of aquatic exercise to treat chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine 2009;34:1436–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. França FR, Burke TN, Caffaro RR, et al. . Effects of muscular stretching and segmental stabilization on functional disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012;35:279–85. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. França FR, Burke TN, Hanada ES, et al. . Segmental stabilization and muscular strengthening in chronic low back pain: a comparative study. Clinics 2010;65:1013–7. 10.1590/S1807-59322010001000015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gak H, Chae-Woo LEE, Seong-Gil KIM, et al. . The effects of trunk stability exercise and a combined exercise program on pain, flexibility, and static balance in chronic low back pain patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:1153–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gur A, Karakoc M, Cevik R, et al. . Efficacy of low power laser therapy and exercise on pain and functions in chronic low back pain. Lasers Surg Med 2003;32:233–8. 10.1002/lsm.10134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Harts C, Helmhout P, de Bie R. Staal J. A high-intensity lumbar extensor strengthening program is little better than a low-intensity program or a waiting-list group for chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. Aust J Physiother 2009;54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Dehghani A, Solati K. A comparison of the effects of Pilates and McKenzie training on pain and general health in men with chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. Indian J Palliat Care 2017;23:36–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Heidari RS, Sahebozamani M, Karimi Afshar F. Comparison of the effects of 8 weeks of core stability exercise on ball and sling exercise on the quality of life and pain in the female with non-specific chronic low back pain (nslbp). J Adv Biomed Res 2018;26:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hosseinifar M, Akbari A, Mahdavi M, et al. . Comparison of balance and stabilizing trainings on balance indices in patients suffering from nonspecific chronic low back pain. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2018;9:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hosseinifar M, Akbari M, Behtash H, et al. . The effects of stabilization and McKenzie exercises on transverse abdominis and multifidus muscle thickness, pain, and disability: a randomized controlled trial in nonspecific chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2013;25:1541–5. 10.1589/jpts.25.1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Igsoo CHO, Chunbae J, Sangyong LEE, et al. . Effects of lumbar stabilization exercise on functional disability and lumbar lordosis angle in patients with chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:1983–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kankaanpaa M, Taimela S, Airaksinen O, et al. . The efficacy of active rehabilitation in chronic low back pain - Effect on pain intensity, self-experienced disability, and lumbar fatigability. Spine 1999;24:1034–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kell RT, Asmundson GJG. A comparison of two forms of periodized exercise rehabilitation programs in the management of chronic nonspecific low-back pain. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:513–23. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181918a6e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kell RT, Risi AD, Barden JM. The response of persons with chronic nonspecific low back pain to three different volumes of periodized musculoskeletal rehabilitation. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:1052–64. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d09df7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kim B-R, Lee H-J. Effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation-based abdominal muscle strengthening training on pulmonary function, pain, and functional disability index in chronic low back pain patients. J Exerc Rehabil 2017;13:486–90. 10.12965/jer.1735030.515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kim T, Lee J, Oh S, et al. . Effectiveness of simulated horseback riding for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Sport Rehabil 2019:1–7. 10.1123/jsr.2018-0252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. KJ K, GC H, Yook YS, et al. . Effects of 12-week lumbar stabilization exercise and sling exercise on lumbosacral region angle, lumbar muscle strength, and pain scale of patients with chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2018;30:18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kofotolis N, Kellis E, Vlachopoulos SP, et al. . Effects of Pilates and trunk strengthening exercises on health-related quality of life in women with chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2016;29:649–59. 10.3233/BMR-160665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kofotolis ND, Vlachopoulos SP, Kellis E. Sequentially allocated clinical trial of rhythmic stabilization exercises and TENS in women with chronic low back pain. Clin Rehabil 2008;22:99–111. 10.1177/0269215507080122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Lawand P, Lombardi Júnior I, Jones A, et al. . Effect of a muscle stretching program using the global postural reeducation method for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Joint Bone Spine 2015;82:272–7. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Liu J, Yeung A, Xiao T, et al. . Chen-style tai chi for individuals (aged 50 years old or above) with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:517 10.3390/ijerph16030517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Macedo LG, Latimer J, Maher CG, et al. . Effect of motor control exercises versus graded activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2012;92:363–77. 10.2522/ptj.20110290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Masharawi Y, Nadaf N. The effect of non-weight bearing group-exercising on females with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized single blind controlled pilot study. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2013;26:353–9. 10.3233/BMR-130391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Mazloum V, Sahebozamani M, Barati A, et al. . The effects of selective Pilates versus extension-based exercises on rehabilitation of low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2018;22:999–1003. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Muharram A, Liu WG, Wang ZY, et al. . Shadowboxing for relief of chronic low back pain. Int J Athl Ther Trai 2011;16:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Murtezani A, Hundozi H, Orovcanec N, et al. . A comparison of high intensity aerobic exercise and passive modalities for the treatment of workers with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2011;47:359–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Nambi GS, Inbasekaran D, Khuman R, et al. . Changes in pain intensity and health related quality of life with Iyengar yoga in nonspecific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Int J Yoga 2014;7:48–53. 10.4103/0973-6131.123481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Noormohammadpour P, Kordi M, Mansournia MA, et al. . The role of a multi-step core stability exercise program in the treatment of nurses with chronic low back pain: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Asian Spine J 2018;12:490–502. 10.4184/asj.2018.12.3.490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. HW O, Lee MG, Jang JY, et al. . Time-effects of horse simulator exercise on psychophysiological responses in men with chronic low back pain. Isokinet Exerc Sci 2014;22:153–63. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Puppin M, Marques A, Silva A, et al. . Stretching in nonspecific chronic low back pain: a strategy of the GDS method. Fisioter Pes 2011;18:116–21. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sang Wk LEE, Suhn Yeop KIM. Effects of hip exercises for chronic low-back pain patients with lumbar instability. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:345–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Schinhan M, Neubauer B, Pieber K, et al. . Climbing has a positive impact on low back pain: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med 2016;26:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sedaghati P, Arjmand A, Sedaghati N. Comparison of the effects of different training approaches on dynamic balance and pain intensity in the patients with chronic back pain. Sci J Kurd Univ Med Sci 2017;22:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 121. Segal-Snir Y, Lubetzky VA, Masharawi Y. Rotation exercise classes did not improve function in women with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized single blind controlled study. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2016;29:467–75. 10.3233/BMR-150642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Se-Hun KIM, Dong-Yel SEO. Effects of a therapeutic climbing program on muscle activation and SF-36 scores of patients with lower back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:743–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Seong Hun YU, Yong Hyeon SIM, Myung Hoon KIM, et al. . The effect of abdominal drawing-in exercise and myofascial release on pain, flexibility, and balance of elderly females. J Phys Ther Sci 2016;28:2812–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Seong-Dae WOO, Tae-Ho KIM. The effects of lumbar stabilization exercise with thoracic extension exercise on lumbosacral alignment and the low back pain disability index in patients with chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci 2016;28:680–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Shaughnessy M, Caulfield B. A pilot study to investigate the effect of lumbar stabilisation exercise training on functional ability and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. Int J Rehabil Res 2004;27:297–301. 10.1097/00004356-200412000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Sherman KJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:2019–26. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Shnayderman I, Katz-Leurer M. An aerobic walking programme versus muscle strengthening programme for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:207–14. 10.1177/0269215512453353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]