Abstract

Background

The use of patient-facing health technologies to manage long-term conditions is increasing; however, children and young people may have particular concerns or needs before deciding to use different health technologies.

Aims

To identify children and young people’s reported concerns or needs in relation to using health technologies to self-manage long-term conditions.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted. We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO and CINAHL in February 2019. Searches were limited to papers published between January 2008 and February 2019. We included any health technology used to manage long-term conditions. A thematic synthesis of the data from the included studies was undertaken. We engaged children with long-term conditions (and parents) to support review design, interpretation of findings and development of recommendations.

Results

Thirty-eight journal articles were included, describing concerns or needs expressed by n=970 children and/or young people aged 5–18 years. Most included studies were undertaken in high-income countries with children aged 11 years and older. Studies examined concerns with mobile applications (n=14), internet (n=9), social media (n=3), interactive online treatment programmes (n=3), telehealth (n=1), devices (n=3) or a combination (n=5). Children and young people’s main concerns were labelling and identity; accessibility; privacy and reliability; and trustworthiness of information.

Discussion

This review highlights important concerns that children and young people may have before using technology to self-manage their long-term condition. In future, research should involve children and young people throughout the development of technology, from identifying their unmet needs through to design and evaluation of interventions.

Keywords: technology, adolescent health

What is already known on this topic?

The use of patient-facing technologies for children and young people (CYP) to self-manage long-term conditions (LTCs) is rapidly increasing.

There are many studies exploring the use or development of new health technology but few that explored CYP’s concerns about the use of this technology.

It is important to obtain stakeholders’ views (particularly CYP’s) about their use of technologies or treatments.

What this study adds?

We have identified key concerns of CYP about their use of health technology to self-manage LTCs.

Concerns included labelling and identity; accessibility; privacy and reliability; and trustworthiness.

It is important to understand and address these concerns as they are potential barriers to engagement with health technologies

Background

Patient-facing health technologies (eg, virtual reality, augmented reality, telehealth and medical devices) have the potential to address key healthcare challenges, and their use is rapidly expanding.1 Increasingly, adults with long-term conditions (LTCs) self-manage their health,2 sometimes with remote clinical support and monitoring. This approach could reduce health system burden, while offering convenience for clinician–patient engagement.3 There is growing interest in the use of technologies to support children and young people (CYP) with LTCs.4

Involving CYP with LTCs in developing and using health technologies provides opportunities for enhancing their health and well-being.1 To date, there is limited research into the challenges of using technology and concerns felt by end-users, particularly CYP. Recent systematic reviews highlight privacy and security issues associated with the use of mobile health applications (apps) for CYP4–6 and CYP wanting access to safe, moderated forums to communicate with peers.7 For example, the Brushing RemInder 4 Good Oral HealTh (BRIGHT) trial8 used a short messaging service to encourage CYP to brush their teeth. During the intervention development and trial design, CYP expressed concerns over who could access their mobile phone numbers and how they could stop receiving text messages. Recent studies7 9 suggest that CYP may require specific information and guidance on privacy, security and data confidentiality before participating in research involving healthcare technologies. This scoping review and associated stakeholder consultation aimed to identify empirical research reporting CYP’s concerns and needs relating to the use of health technologies to self-manage LTCs and develop recommendations for technology developers and researchers.

Methods

A scoping review10 was undertaken without quality assessments.11

Search strategy

Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO and CINAHL were searched in February 2019 using a strategy developed with an information specialist and modified for each database (see online supplementary appendix 1). The search was limited to papers published between January 2008 and February 2019 to ensure relevance to current health technologies.

archdischild-2020-319103supp001.pdf (270.2KB, pdf)

Eligibility

table 1 outlines the review inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for studies within this review

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

Population: CYP with physical and/or mental LTCs aged up to and including 18 years (no lower age limit). LTCs were defined as ‘those conditions for which there is currently no cure, and which are managed with drugs and other treatment’.78

Concept: concerns and needs of CYP in relation to health technology including privacy, stigma, security, views about barriers to how they use health technology and any information that CYP suggested they needed to know before using health technology. Context: the focus was on health technologies that CYP engage or interact with to manage LTCs. Health technologies included: mobile apps; virtual and augmented reality; telehealth; digital health; digitised medical devices; gamification/health gaming; receiving health information via SMS (digital health education messages); patient care/monitoring wearables; remote monitoring; consumer products (eg, Fitbit); and social media. All settings (eg, home, hospital and clinic) and countries were included. Studies examining hypothetical (prospective) use, (how CYP may use the technology and what their concerns may be) and those studying retrospectively (after CYP had used the technology, either in real life situation or in a user-testing scenario), were included. Study design: qualitative, surveys/questionnaires, feasibility, acceptability, user-testing/usability and mixed methods (including any of these study designs undertaken within trials), where data from those <18 years or younger could be extracted. |

Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not involve CYP with LTCs; (2) only explored parents’ or clinicians’ views, experiences, use or concerns about a health technology; (3) explored use of health technologies to manage acute conditions, diagnosis or for one-off measurements; (4) included technologies to enhance mobility, senses or provide medications (eg, hearing aids, mobility aids and prostheses); (5) exclusively included CYP aged over 18 years; (6) did not separate CYP’s and adults’ data within the study; and (7) were not published in English. |

CYP, children and young people; LTCs, long-term conditions; SMS, short messaging service.

Study selection

Records were deduplicated in Endnote and managed using Covidence. JM-K screened title and abstracts, with 20% of records double-screened (SB and VS). Agreement rate and Cohen kappa coefficients were calculated to measure inter-rater reliability. Three reviewers (JM-K, SB and CM) undertook screening of full-text records independently. When uncertainty about inclusion arose, articles were discussed (JM-K, CM, SB and AD) until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by JM-K (with AD and CM each independently replicating extraction of 50% of the studies) using a prepiloted template. Data extracted included: lead author; year of publication; country; study participant details (age, number, sex and LTC); study design; setting where technology was used; retrospective or prospective use; concerns or information needed before using the technology; whether CYP were involved in the scoping or design of the technology; and any quotations to support the concerns extracted.

Data synthesis

Bubble plots highlight patterns and gaps in data and identify the number of included studies by country and publication year. Thematic analysis of the findings of each study was undertaken. JM-K and SB read through extracted qualitative (quotations and interpretation from the primary study authors) and quantitative data to identify concerns and needs and assign themes.12

Stakeholder consultation

Throughout the project, we engaged with CYP and parent stakeholders who had used health technologies to manage LTCs. To explore the context for this review from the perspective of CYP (April 2019), JM-K and SS facilitated a discussion with (n=4) stakeholders, two CYP aged 13 and 15 years and their mothers, to determine their views on concerns and informational needs.

Following the review (October 2019), we shared the findings with CYP and parents from the NIHR Generation R Young Persons’ Advisory Group (YPAG). The consultation was a face-to-face meeting with 15 CYP (age 9–18 years) and 4 parents (who have children with LTC). Participants noted and discussed findings that interested or surprised them. Participants were invited to make recommendations for health professionals developing self-management support health technologies (based on the review findings) on Post-it notes and discuss these within the group. The outcomes of this discussion supplemented the review findings and informed the recommendations.

Results

Study selection

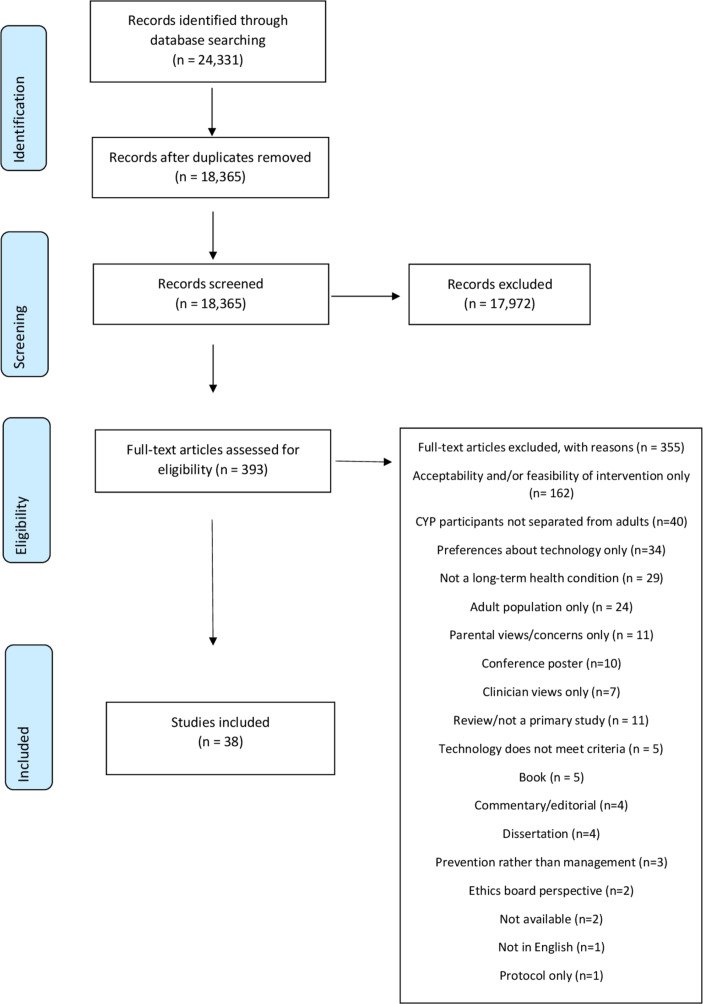

A total of 18 365 unique records were identified through the electronic searches. There was a 95% agreement rate in the 3673 double-screened abstracts(moderate kappa agreements). No potentially eligible studies were missed. Single screening was undertaken for the remaining 14 692 records. Many excluded papers did not include CYP’s concerns or perspectives (eg, only proxy views from parents or clinicians), or reported the technology use outside the scope of this review. Thirty-eight studies were included (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. CYP, children and young people; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

All studies (table 2) were published between 2009 and 2019 and undertaken in Australia13–15 (n=3), Canada16–22 (n=7), England23–31 (n=9), Italy32 (n=1), the Netherlands33 (n=1), New Zealand34 (n=1), Nigeria35 (n=1), Spain36 (n=1), Sweden37 38 (n=2), USA39–49 (n=11) and Wales50 (n=1). Studies included CYP with the following LTCs: asthma (n=7), type 1 diabetes (n=5), chronic kidney disease (n=3), cancer (n=3), obesity (n=3), cerebral palsy/spina bifida (n=2), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (n=2) and HIV, idiopathic scoliosis, colorectal conditions, chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalitis with n=1 study each. Figure 2 shows the distribution of studies by country and publication date.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies (n=38)

| Lead author and year study published | Study design | Country of study | Mean age (years) | Study participants within age range (total sample size) | Study participants' female (%) | Study participants: LTC | CYP involved in the design of the technology? |

| Barnfather (2011) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | Canada | 14.6 | 22* (27) | 12 (44.4)* | Cerebral palsy and spina bifida. | Yes |

| Bevan Jones (2018) |

Qualitative (interviews and focus groups) | Wales | 15.85† | 11 (33) | 7 (64) | Depression. | Yes |

| Boydell (2010) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | Canada | NR | 30 (30) | 13 (43.3) | Variety of mental health conditions and neurodevelopmental disorders. | No |

| Bradford (2015) |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Australia | NR | 17 (129) | 9 (53) | Mental health. | No |

| Brigden (2018) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | England | 14.89 | 9 | 6 (66.6) | Chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis. | Yes |

| Britto (2012) |

Pilot or feasibility study (questionnaires) | USA | 15.2 | 12‡ (19) | 10 (52.6) | Asthma. | No |

| Cafazzo (2012) |

Codesign plus clinical pilot of intervention (interviews and questionnaires) | Canada | 14.9 | 6 involved in design (26 in total within full study) | NR | Type 1 diabetes. | Yes |

| Cai (2017) |

Qualitative (interviews and focus groups) | England | NR | 29 | 19 (65.5) | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. | Yes |

| Carpenter (2016) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | USA | 14.7 | 20 | 9 (45) | Asthma. | No |

| Clark (2018) |

Qualitative (interviews) | Australia | 15.2 | 8 (29) | 0 (0) | Anxiety (with or without depression). | No |

| Dominguez (2017) |

Qualitative (interviews) plus questionnaire | Spain | 18.7 | 9 (20) |

8 (88.9) | Cancer. | No |

| Donzelli (2017) |

Survey/questionnaire | Italy | 14.65 | 336 (364) | 301 (82.7)§ | Idiopathic scoliosis. | Yes |

| Dulli (2018) |

Pilot or feasibility study (qualitative and questionnaire) | Nigeria | NR | 41 | 22 (53) – total | HIV. | No |

| Holmberg (2018) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | Sweden | NR | 20 | 11 (55) | Obesity. | No |

| Howard (2017) |

Usability/user testing (questionnaires and interviews) |

England | 13.4 | 7 | 2 (28.6) | Asthma. | Yes |

| Huby (2017) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | England | NR | 26 | 12 (46.2) | Chronic kidney disease. | Yes |

| Jibb (2018) |

Pilot study (including interviews and questionnaires) | Canada | NR | 20 in qual (40 in larger study) |

9 (45) | Cancer. | Yes |

| Knibbe (2018) |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Canada | 14.4† | 8 | 5 (62.5) | Cerebral palsy. | No |

| Maurice-Stam (2014) |

Pilot study (including questionnaires) | The Netherlands | NR | 12 (12) | NR | Cancer. | No |

| Mulvaney (2013) |

Survey/questionnaire | USA | 15.2 | 53 | 31 (58) | Asthma. | No |

| Nicholas (2009) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | Canada | 15 | 10 (24) | NR | Chronic kidney disease. | Yes |

| Nightingale (2017) |

Qualitative (individual and joint interviews) | England | NR | 17 | 8 (47.1) | Chronic kidney disease. | Yes |

| Nordfeldt (2013) |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Sweden | NR | 24 (24) | 11 (45.8) | Type 1 diabetes. | No |

| Powell (2017) |

Qualitative (interviews) | England | 9.6† | 5 (5) | 2 (40) | ADHD. | No |

| Ramsey (2018) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | USA | 15.4 | 20 | 10 (50) | Asthma. | No |

| Raval (2017) |

Qualitative (joint interviews) | USA | NR | 2 (6) | NR | Colorectal diseases. | No |

| Rivera (2018) |

Qualitative (focus groups) plus questionnaires | Canada | 14.7 | 19 | 13 (68) | Obesity. | Yes |

| Roberts (2016) |

Qualitative (individual and joint interviews) plus questionnaire | USA | 14.7 | 20 | 9 (45) | Asthma. | No |

| Schneider (2019) |

Usability/user testing (including qualitative) | USA | 14.4 | 20 (20) | 11 (55) | Asthma. | Yes |

| Simons (2016) |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) plus questionnaires | England | NR | 8 (8) | 1 (12.5) | ADHD. | Yes |

| Stewart (2018) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | England | 12.86 | 8 | 5 (62.5) | Asthma. | No |

| Thabrew (2016) |

Qualitative (focus group discussions) | New Zealand | 12.55† | 22 | 10¶ (45.5) | Variety of long-term physical conditions. | No |

| Vaala (2018) |

Survey/questionnaire | USA | NR | 134 | 75 (56) | Type 1 diabetes. | No |

| Van Rensburg (2016) |

Qualitative (individual interviews) | USA | 16.1† | 20 (20) | 15 (75) | Variety of mental health conditions and neurodevelopmental disorders. | No |

| Waite-Jones (2018) |

Qualitative (interviews and focus groups) | England | 13.6† | 9 | 9 (81.8) | Juvenile arthritis. | Yes |

| Woolford (2013) |

Qualitative (interviews and focus groups) | USA | 16 | 11 | 8 (73)** | Obesity. | No |

| Wuthrich (2012) |

RCT (including questionnaire) | Australia | 14.6 | 24 (43) | 16 (66.7) | Anxiety. | Yes |

| Yi-Frazier (2015) |

Qualitative (interviews and focus groups) | USA | 16.4 | 20 (20)†† | 13 (65) | Type 1 diabetes. | No |

*27 in total signed up and 22 participated in the qualitative research; subsequent percentages are % of total enrolled.

†Mean age not reported in the original study but calculated from raw data.

‡Only intervention participants (these are the only participants who provided concerns).

§These figures relate to the 364 approached not the 336 who participated in the study.

¶Estimate calculated from proportions provided in the study.

**Percentages reported in the study appear incorrect so have been adjusted in this table.

††20 CYP were enrolled but only 10 had individual interviews and 5 attended a focus group.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CYP, children and young people; LTC, long-term condition; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Figure 2.

Included studies by publication date and country.

Most studies were exclusively qualitative (n=26, 68%),13 14 16 17 20–24 26 27 29–31 34 36–38 40 42–44 47–50 while other study designs such as user testing, pilot or feasibility studies and one randomised controlled trial each included some qualitative data (n=12, 32%).15 18 19 25 32 33 35 39 41 45 46 Only seven studies included participants under 11 years.17 24 26–28 31 34 The age range of CYP represented was 5–18 years.

Technologies were categorised using a previously reported typology51: internet (eg, websites, forums, chat rooms and e-tools) (n=9)13 16 23 26 33–35 37 46; social media (dedicated platforms, eg, YouTube, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram) (n=3)47–49; mHealth (eg, mobile phone apps and text messaging) (n=14)18 19 22 24 28 29 31 39–45; telehealth (eg, video conferencing and telephone consultations) (n=1)17; interactive online treatment programmes (n=3)14 15 50; and devices (eg, wearables and other devices/hardware)25 30 32 (n=3). Five studies involved combinations of technologies.20 21 27 36 38

Concerns and needs expressed by CYP

Regardless of technology type, many concerns reported by CYP were similar across studies (see table 3). There were four overarching themes, summarised below, with quotations illustrating key concerns in the words of CYP themselves (table 4). Full list of quotations per study is provided in online supplementary appendix 2.

Table 3.

Summary of technologies and related concerns raised by CYP

| Lead author and date | Age range (years) | Study participants: long-term health condition | Type of technology and brief description | Setting (where technology was studied) | Use of technology | Concerns |

| Barnfather (2011) | 12–18 | Cerebral palsy and spina bifida. | Internet (online support). |

Home for 25 sessions. | Retrospective. |

|

| Bevan-Jones (2018) |

13–18 | Depression. | Interactive online treatment programme (psychoeducation multimedia programme: MoodHwb). |

Discussed during interviews and focus groups. | Prospective. |

|

| Boydell (2010) | 7–18 | Variety of mental health conditions and neurodevelopmental disorders. | Telehealth (telepsychiatry). |

Clinic (interviewed after teleconsultation). | Retrospective. |

|

| Bradford (2015) |

12–18* | Mental health. | Internet (electronic mental health assessment). |

Hypothetical (e-tool described in interviews). | Prospective. |

|

| Brigden (2018) | 12–17 | Chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis. | Internet (online resources). |

Discussion of past use of online resources during interviews. | Retrospective. |

|

| Britto (2012) | 13–18 | Asthma. | mHealth (text messaging on mobile phone). |

Daily life (home, school and so on) for 3 months. | Retrospective. |

|

| Cafazzo (2012) | 12–16 | Type 1 diabetes. | mHealth (smartphone app). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Cai (2017) | 10–18* | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. | mHealth (smartphone app). |

Clinic. | Retrospective. |

|

| Carpenter (2016) | 12–16 | Asthma. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Retrospective. |

|

|

| Clark (2018) | 12–18 | Anxiety (with or without depression). | Interactive online treatment programme (online anxiety disorder treatment programme). |

Psychology clinics, school or participant’s house. | Prospective. |

|

| Dominguez (2017) | 14–18* | Cancer. | Internet and social media (internet searches about LTC; Facebook, Twitter and Instagram; also blogs). |

Interviews – discussion about technology. | Prospective. |

|

| Donzelli (2017) | NR | Idiopathic scoliosis. | Device (thermobrace plus sensor with reading software). |

Daily life (survey in waiting room). | Retrospective. |

|

| Dulli (2018) | 15–18* | HIV. | Internet (online support group). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Holmberg (2018) | 13–16 | Obesity. | Internet (online weight, food and health information). |

Discussion about past use in interviews. | Retrospective. |

|

| Howard (2017) | 11–16 | Asthma. | Device (electronic monitoring device). |

Home. | Retrospective. |

|

| Huby (2017) | 5–17 | Chronic kidney disease (CKD). | Internet (web-based support for CKD). |

Interviews conducted in hospital. | Prospective. |

|

| Jibb (2018) | 12–17 | Cancer. | mHealth (smartphone app). |

Home use for 28 days. | Retrospective. |

|

| Knibbe (2018) | 12–18 | Cerebral palsy. | Internet, social media, mHealth (Facebook, Youtube, pedometer, fitness app and active video games). | Hospital. | Prospective. |

|

| Maurice-Stam (2014) | 11–17 | Cancer. | Internet (website with secure chat room). |

Not specified but outside of clinic. | Retrospective. |

|

| Mulvaney (2013) | 12–18 | Asthma. | mHealth (using phone to monitor asthma). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Nicholas (2009) | NR | Chronic kidney disease. | Internet (email and online social support network). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Nightingale (2017) | 5–18 | Chronic kidney disease. | Internet and mHealth (apps and websites). |

During interviews. | Prospective. |

|

| Nordfeldt (2013) | 10–17 | Type 1 diabetes. | Internet and social media (broad definition). |

Clinic (focus groups). | Prospective. |

|

| Powell (2017) | 8–13 | ADHD. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Interview location (participant's home). | Retrospective. |

|

| Ramsey (2018) | 13–18 | Asthma. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Some use in real life; some hypothetical use in interviews. | Prospective. |

|

| Raval (2017) | ? NR (3-16) |

Colorectal diseases. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

During interviews (discussion about apps). | Prospective. |

|

| Rivera (2018) | 12–18 | Obesity. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Discussion about apps in focus groups. | Prospective. |

|

| Roberts (2016) | 12–16 | Asthma. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Schneider (2019) | 12–17 | Asthma. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Simons (2016) | 12–13 | ADHD. | mHealth (text message and app for remote monitoring). |

During focus groups - discussion about technology. | Prospective. |

|

| Stewart (2018) | 11–15 | Asthma. | Device (electronic monitoring devices). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Thabrew (2016) | 8–17 | Variety of physical conditions. | Internet and interactive online treatment programmes (online support and e-therapy). |

Discussed in focus groups (hospital). | Prospective. |

|

| Vaala (2018) | 13–17 | Type 1 diabetes. | Internet (online questionnaire to sharing personal data with peers). |

Clinic. | Prospective. |

|

| van Rensburg (2016) | 14–18 | Variety of mental health conditions and neurodevelopmental disorders. | Social media (broad but did specifically include facebook). |

n/a | Prospective. |

|

| Waite-Jones (2018) | 10–18 | Juvenile arthritis. | mHealth (smartphone apps). |

Discussion in focus groups in clinic. | Prospective. |

|

| Woolford (2013) | 13–18 | Obesity. | Social media (Facebook). | Discussion in focus groups. | Prospective. |

|

| Wuthrich (2012) | 14–17 | Anxiety. | Interactive online treatment programme (Cool Teens cCBT). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective. |

|

| Yi-Frazier (2015) | 14–18 | Type 1 diabetes. | Social media (Instagram). |

Daily life (home, school and so on). | Retrospective and prospective. |

|

*Age range of total sample exceeded 18 years, but reviewers were able to isolate data pertaining only to CYP whose age range met our inclusion criteria.

CYP, children and young people.

Table 4.

Quotations to illustrate identified themes

| Themes and example concerns | Illustrative quotes* |

| Labelling and dentity | |

| Stigma | ‘In assembly at school when there’s lots of people there. I’m taking it out, and most people have normal inhalers, and I’m pulling this massive thing out. Even the teachers would be looking at me like “what’s that?” There’d be a lot of questions especially the teachers, because they would want to know what it is and everything’. (Adolescent, exact age unknown)25 |

| Cyberbullying | ‘The problem with an online chatroom is you’re going to get people who don’t actually need help and they don’t need to be on the website at all. They’re like ”Hey guys, you know what would be funny, making fun of these depressed kids”’. (14 years)14 |

| Inclusivity | ‘With some of the apps or even like a blog and stuff, you could have a specific, um, part or like theme for disabled so that people who are like…you'd be talking to people who understand what you're going through in a way’. (12 years)20

‘I personally don’t like being grouped in specifically with people with disabilities, because it makes me think I’m not normal if I’m being stuck with other people who have disabilities too. It makes me focus on the fact that I’m different, and I don’t really like that’. (Adolescent, age not stated)16 |

| Accessibility | |

| Usability | ‘I’ve had a look on the NHS site… it’s quite wordy and that sort of thing I wouldn’t necessarily understand… it’s sort of doctorised… it’s not necessarily aimed at young people’. (Adolescent, exact age unknown)23 |

| Financial cost | ‘… [Y]ou have to like buy them but that’s annoying cos they should be free…I haven’t even got a credit card’. (Adolescent, exact age unknown)28 |

| Access to WiFi | ‘Sometimes, when I don’t have WiFi it is hard for me’. (Exact age unknown)45 |

| School rules | ‘Having it [the app] in class would be helpful, cause they say you’re not allowed to have a phone in class. I can’t have it out in any of my classes … in the middle of the day, if you have trouble breathing you might want to record it so you can tell your pulmonologist’. (Age unknown)45 |

| Privacy | |

| Data sharing and confidentiality | ‘I don’t really like the idea of it being on Facebook… I mean people can hack into you to see what you’ve been writing and people can, without hacking into you; see what you’ve written…’ (Age unknown)26 |

| Being monitored or watched | ‘Hmm err it was a little bit spyee … because they are checking up to see if I’m taking my inhaler by watching me instead of asking me’. (Adolescent, exact age unknown)30 |

| Control | ‘I want to be very certain of exactly what they can see’. (Age not stated)42 |

| Trustworthiness and reliability | Most of the sites regarding stuff like diet are like forums, so anyone can post, so there’s not really that much reliability…t he Kidney Foundation or something, that’s pretty reliable obviously ’cause it’s a government website, so I use that mostly’. (17 years)27 |

| Discomfort or unease | ‘I might not get the same level of attention and you know, kind of therapeutic qualities that I would if I was in a room with a therapist, and it’s not like personal, you know, you know what I mean, because you’re not right there with them, talking about it, you’re on a keyboard talking about it’. (Adolescent, exact age unknown)47 |

| Responsiveness | |

| Fear of misinterpretation | ‘Yeah, I mean, there’s inside jokes between me and my friends, and if he or she didn’t know about it, she [provider] might take that the wrong way… I don’t know how they [providers] would put it – as unsafe, or between me and my friends as a joke. And I wouldn’t know how they would take it’. (Age 14–17 years)47 |

*Age and terminology (eg, adolescent and child) as reported by primary study.

archdischild-2020-319103supp002.pdf (254.5KB, pdf)

Labelling and identity

CYP were concerned that stigma could arise from technology visibility, for example, the potential for social embarrassment prevented them from using devices in public.14 Many technologies were designed to enable CYP to engage with an online community of users, which in some cases included other CYP from the healthy population, which led to CYPs’ concerns about cyberbullying.14 50 Some CYP felt that technologies involving online communities should have separate condition-specific spaces to reduce the risk of discrimination and support inclusivity.20 44 48 Suggestions included private messaging or chat options.20 Conversely, some CYP expressed concerns about technologies that exclusively brought together CYP with the same condition in forums or chatrooms.16

Overall, there was a tension between the need for normalisation and the risk of discrimination. For some CYP, ‘being normal’ meant feeling part of a community of other CYP who shared their condition/s and experience/s; while for others, it was also about feeling included in a community of healthy peers.

Accessibility

This included usability concerns regarding the age and developmental appropriateness of content26 31 34 38 and risks associated with bringing CYP from a broad age range together in forums or chat rooms,28 such as an increase in perceived ‘noise’ that might prevent individual voices being heard and understood.16 CYP also expressed preferences for plain language and the absence of jargon or medical terminology that they would find difficult to understand.23 27 36

CYP identified limited access to Wi-Fi in hospitals, at home and in the community as possible barriers to some technologies.26 29 Rules imposed in schools regarding mobile phone use were also highlighted.41 45

CYP highlighted financial costs28 31 associated with using mobile data45 to access apps as well as the impact on device storage capacity43 and challenged the assumption that all CYP used social media or had access to smartphones.49

Privacy

Some privacy concerns were linked to technology visibility that may draw attention to an undisclosed condition.18 25 CYP highlighted the potential for unwanted attention35 44 and questioning that may arise from using a device.25 Concerns surrounding data sharing and confidentiality of personal information were also evident.14 22 33 39 48 CYP had preferences about whom they would share data with and were concerned about the perceived dangers and negative implications of sharing data widely.25 31 40 For example, the risks of being ‘hacked’13 26 and the importance of privacy settings24 in various social media platforms and apps; privacy related to content that CYP created50 and fears of being monitored or watched by parents and/or clinicians17 24 30 47; and the permanence of data on websites and apps.13

Ultimately, CYP desired control over their data and privacy; they sought a balance between safety, confidentiality, anonymity and the option to foster connection with others by ‘putting a face to the name’21 and sharing personal information if they so choose.

Trustworthiness and reliability

CYP were generally wary of online information (through websites or apps)27 37 unless it was perceived to be from a trusted ‘official source’, for example, from recognisable organisations or endorsed by clinicians with expertise in their condition.23 26 29 36 38 They also raised concerns about images or content that could be perceived as overly negative or alarmist about their condition,36 48 although some CYP were concerned about images that they perceived to be unrealistic or idealised (particularly in relation to body image).37

Some CYP expressed discomfort or unease with the introduction of technologies that reduce face-to-face contact with their clinician. CYP were particularly concerned about the potential for lack of clinician responsiveness19 47 and the impact on their ability to form an open, honest and therapeutic relationship17 as well as the risk of clinicians missing important non-verbal cues.13 30

Linked to this, a general fear of misinterpretation was also identified.47 CYP expressed concerns that information recorded on devices (rather than in conversation) could land them in trouble with limited opportunity to explain their side of the story30

Stakeholder consultation

When discussing the findings with CYP and parents, they expressed surprise at the level of concern for cyberbullying in relation to using health technologies to manage an LTC. However, they concurred with concerns identified in the review relating to security of data and information. They were surprised by studies reporting that language was not age appropriate, as they presumed that mobile apps would at least be ‘word-friendly’ for children if that was the target end user. The group noted that CYP will have different reasons and motivations for using technology and felt it was important to ensure that CYP were involved early in technology development and to not underestimate the input and impact that CYP can have. They also suggested gamification to help young children with technology. The group felt incorporating passcodes, or other forms of security, was important to ensure data security and access.

Discussion

Main findings

This review has highlighted CYP’s specific concerns about the use of technology to self-manage LTCs including labelling and identity; accessibility; privacy; and trustworthiness of information. Most studies were undertaken in high-income countries and mainly sought the views of CYP aged 11 years and older in relation to a wide range of health technologies. The focus on older CYP possibly reflects difficulties that researchers expect to encounter when undertaking research with children52 and indicates a gap in knowledge about the concerns of CYP under 11 years. The most common LTCs studied included type 1 diabetes, asthma and mental health conditions. Included studies generally had small samples. Many studies were excluded because they focused on the views and concerns of parents and/or clinicians only.

Our findings in relation to the literature

The use of health technologies by CYP to manage LTCs is increasing with many studies describing their development, acceptability and use by CYP45 53–61; effectiveness53 62–64; and compliance by CYP.41 57 However, there is limited literature on the concerns that CYP may have when (or before) using a health technology for self-managing their LTC, and no review has specifically explored these concerns.

Our results indicate that the views of CYP with LTC are under-represented in the literature. Many potentially eligible studies reported solely on clinicians’ or parents’ views or failed to separate out concerns expressed by CYP and adults. As previously reported, primary studies exploring CYP’s concerns tend to involve healthy populations63 65 66 (eg, schoolchildren) rather than CYP with LTCs, even when evaluating the use of technologies that are designed for use by CYP with LTCs. Authentic user involvement in technology design and research is important and increasingly required by funders; CYP with LTCs are uniquely placed to explain their concerns about new technologies.

We did not find any studies examining CYP concerns regarding the use of virtual or augmented reality technologies to self-manage LTCs. This may reflect wider-reaching tendencies by researchers to only seek proxy views about how CYP use technology to manage an LTC.

Our findings are consistent with a previous review on the use of digital clinical communication (eg, telehealth) for CYP with long-term mental health conditions reporting that most studies focused only on satisfaction, acceptance or feasibility of the technology.67 While these issues are important, a broader focus on general concerns contributes to our understanding of potential barriers to technology use.

We identified a range of concerns, several clustered around a theme of labelling and identity and highlighting that CYP with LTCs are a diverse group, and those with the same condition may have differing concerns about the use of interactive technologies. CYP varied in whether they wanted their condition to be known, to interact with others with the same condition, or with healthy CYP. These concerns are supported by previous literature that highlights variations in how CYP wish to use online forums.68 69 The potential risk of cyberbullying identified in some studies is supported by a recent review about risks associated with the use of social media by CYP.70 In addition, CYP were particularly cautious about stigma arising from the use of technologies to manage mental health conditions and sexually transmitted infections.71

Accessibility of the technology, through age-appropriate language, style and physical access, was important. This concern is supported by other literature involving CYP without LTCs, for instance the ability of school-aged CYP to identify and access information about sexual health.72 The importance of language was also recognised as important in some studies.69

A not unexpected key theme in this review was privacy.72–75 Our findings complement a recent review calling for research that explores CYP’s privacy and data security issues when using digital health technology to manage LTCs.76

Trust in the technology was another important factor to determine whether CYP would use a particular technology to manage a LTC. A recent review highlighted the importance of clinicians understanding CYP’s needs in relation to their use of health technologies and also to help CYP identify appropriate technology.4 A study examining the concerns of CYP (without LTCs) also highlighted the concern, consistent across all age groups, of trust for health-related social media.77

Based on the concerns raised in the included studies within this review, we have developed a set of recommendations in conjunction with our CYP and parent stakeholders that we feel are important for future development and use of technology by CYP with LTCs (see box 1).

Box 1. Recommendations.

The following recommendations derive from our findings and are supported by the project stakeholders:

Ensure any technology for use by CYP is age and developmentally appropriate (in terms of language and style; if the technology is social media, then carefully consider the appropriate age range of participants).

CYP will want to use technology for different reasons and with different motivations (eg, some will want to use technology that connects them to others with the same condition for support, while others will not want to be segregated by their condition). Give CYP the option of how they use technology. Technology developers should involve CYP in the design and development of health technologies.

CYP may have concerns about using technology to manage an LTC, and these concerns should be considered alongside any potential benefits for CYP.

Trust will be an important factor for CYP using technology for their health; they will want to know how the technology has been developed, curated, tested and used previously in order to make an informed decision about whether they want to use it.

For technology involving images, recognise that CYP may not filter what they see and some may be surprised or concerned by distressing images (eg, on closed Facebook groups). A careful and sensitive approach should be taken to minimise CYP’s concerns.

Consider making the technology (eg, forums or text on websites) not overly negative, particularly consider moderation for peer communication, to avoid causing unnecessary anxiety for end users.

For any technology involving data, explain to CYP who will have access to their information, how their information will be stored and how CYP can change such access. Consider having a passcode or biometric protection for access to mobile apps, or where the operating system allows, prompting the use of these functions. Where messaging occurs, consider end-to-end encryption and self-destructing messages.

Recognise that CYP are taught digital safety in school, including caution around sharing their information, and may feel that doing so for the purposes of health technology contradicts this. They will want to know who will have access to their information and why.

In addition, stakeholders recommended the following:

Do not under-estimate CYP’s capabilities and the important input they can provide to technology development.

Consider gamification within technologies for younger CYP with LTCs.

When developing technology for use by CYP to manage LTCs, involve the appropriate group of CYP early in the process to ensure that the technology will be something they will want to use and will meet their needs. For example, if you plan to develop technology for CYP aged Y years with condition X, then work with CYP that are of this age with this condition.

Consider whether health inequalities may be created or exacerbated if the technology has a financial cost associated with it.

Tell CYP what the actual impact of using the technology will be for them (eg, will it help them, are there any risks).

Strengths and limitations of the review

A strength of this review is its broad focus on technologies and LTCs in order to identify all information about CYPs’ concerns regarding use of technology to manage LTCs. We used recognised processes to ensure methodological rigour and consulted with CYP and parents. Due to the volume of records identified, we only reviewed full texts of articles that mentioned or alluded to concerns within the abstract. We did not include positive preferences such as what CYP liked or preferred (eg, design features and interactivity elements). We note that many studies focus on positive preferences of CYP for technologies, and this may be an avenue for future research. Many of the included studies were conducted in high-income countries and findings may not generalisable to CYP in low-income countries.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Liverpool Generation R Young Persons’ Advisory Group (YPAG) members (children and young people (CYP) and parents) for their insightful comments and contributions to the development of the recommendations within this review. We would like to thank Jennifer Preston and Sammy Ainsworth for facilitating engagement with the YPAG. We would also like to thank our CYP and parents who were involved on April 2019. We would also like to thank David Torgerson, who is a coinvestigator of this project and provided thoughtful input throughout the duration of the review. We would also like to thank Melissa Harden from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at the University of York for developing and running the search strategy and deduplicating the records. We would also like to thank Stephanie Prady for proof-reading and editing the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @sarah_blower, @SwallowVeronica, @CamilaMaturanaP, @SimonRStones, @drbobphillips, @zmarshman, @DrIanKellar, @natwm10, @JMartinKerry

Contributors: JM-K, VS, ZM, PK, SB, BP, PD, NM, PC, SS and SH developed the grant application for this piece of work. JM-K developed the scoping review protocol with input from BP, VS and SB. JM-K, SB and VS undertook title and abstract screening; CM, SB and JM-K undertook full-text screening; CM, AD and JM-K undertook data extraction with input from SB. JM-K and SS undertook the stakeholder engagement activities. All coauthors provided critical input into the data extracted. SB and JM-K drafted the manuscript, and all coauthors critically reviewed this and provided input and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This scoping review was funded by the University of York’s University Research Priming Fund and is supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Children and Young People MedTech Co-operative (NIHR CYP MedTech). SB’s time was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Yorkshire and Humber ARC.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. No additional data available.

References

- 1. Dimitri P. Child health technology: shaping the future of paediatrics and child health and improving NHS productivity. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:184–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chew-Graham C. Self-Management in long-term conditions – where does the health service sit? Health Expect 2015;18:603–4. 10.1111/hex.12399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walker RC, Tong A, Howard K, et al. Patient expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for chronic diseases: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Med Inform 2019;124:78–85. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aldiss S, Baggott C, Gibson F, et al. A critical review of the use of technology to provide psychosocial support for children and young people with long-term conditions. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:87–101. 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dehling T, Gao F, Schneider S, et al. Exploring the far side of mobile health: information security and privacy of mobile health Apps on iOS and android. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e8. 10.2196/mhealth.3672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Majeed-Ariss R, Baildam E, Campbell M, et al. Apps and adolescents: a systematic review of adolescents' use of mobile phone and tablet Apps that support personal management of their chronic or long-term physical conditions. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e287. 10.2196/jmir.5043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waite-Jones J, Swallow V, Smith J, et al. Developing a mobile-app to aid young people’s self-management of chronic rheumatic disease: a qualitative study. Rheumatology 2017;56 10.1093/rheumatology/kex356.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marshman Z, Ainsworth H, Chestnutt IG, et al. Brushing reminder 4 good oral health (bright) trial: does an SMS behaviour change programme with a classroom-based session improve the oral health of young people living in deprived areas? A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2019;20:452. 10.1186/s13063-019-3538-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nightingale R, Wirz L, Cook W, et al. Collaborating with parents of children with chronic conditions and professionals to design, develop and Pre-pilot plant (the parent learning needs and preferences assessment tool). J Pediatr Nurs 2017;35:90–7. 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bradford S, Rickwood D. Young people's views on electronic mental health assessment: prefer to type than talk? J Child Fam Stud 2015;24:1213–21. 10.1007/s10826-014-9929-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark LH, Hudson JL, Dunstan DA, et al. Capturing the Attitudes of Adolescent Males’ Towards Computerised Mental Health Help-Seeking. Aust Psychol 2018;53:416–26. 10.1111/ap.12341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, Cunningham MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the cool teens CD-ROM computerized program for adolescent anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51:261–70. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnfather A, Stewart M, Magill-Evans J, et al. Computer-mediated support for adolescents with cerebral palsy or spina bifida. Comput Inform Nurs 2011;29:24–33. quiz 34-5. 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181f9db63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boydell KM, Volpe T, Pignatiello A. A qualitative study of young people's perspectives on receiving psychiatric services via televideo. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;19:5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cafazzo JA, Casselman M, Hamming N, et al. Design of an mHealth APP for the self-management of adolescent type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e70. 10.2196/jmir.2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jibb LA, Stevens BJ, Nathan PC, et al. Perceptions of adolescents with cancer related to a pain management APP and its evaluation: qualitative study nested within a multicenter pilot feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e80. 10.2196/mhealth.9319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knibbe TJ, McPherson AC, Gladstone B, et al. "It's all about incentive": Social technology as a potential facilitator for self-determined physical activity participation for young people with physical disabilities. Dev Neurorehabil 2018;21:521–30. 10.1080/17518423.2017.1370501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicholas DB, Picone G, Vigneux A, et al. Evaluation of an online peer support network for adolescents with chronic kidney disease. J Technol Hum Serv 2009;27:23–33. 10.1080/15228830802462063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rivera J, McPherson AC, Hamilton J, et al. User-Centered design of a mobile APP for weight and health management in adolescents with complex health needs: qualitative study. JMIR Form Res 2018;2:e7. 10.2196/formative.8248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brigden A, Barnett J, Parslow RM, et al. Using the Internet to cope with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in adolescence: a qualitative study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2018;2:e000299. 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai RA, Beste D, Chaplin H, et al. Developing and evaluating JIApp: acceptability and usability of a smartphone APP system to improve self-management in young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e121. 10.2196/mhealth.7229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Howard S, Lang A, Sharples S, et al. See I told you I was taking it! - Attitudes of adolescents with asthma towards a device monitoring their inhaler use: Implications for future design. Appl Ergon 2017;58:224–37. 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huby K, Swallow V, Smith T, et al. Children and young people's views on access to a web-based application to support personal management of long-term conditions: a qualitative study. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:126–32. 10.1111/cch.12394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nightingale R, Hall A, Gelder C, et al. Desirable components for a customized, home-based, digital care-management APP for children and young people with long-term, chronic conditions: a qualitative exploration. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e235. 10.2196/jmir.7760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Powell L, Parker J, Robertson N, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: is there an APP for that? suitability assessment of Apps for children and young people with ADHD. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e145. 10.2196/mhealth.7371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simons L, Valentine AZ, Falconer CJ, et al. Developing mHealth remote monitoring technology for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a qualitative study eliciting user priorities and needs. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e31. 10.2196/mhealth.5009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart AC, Gannon KN, Beresford F, et al. Adolescent and caregivers' experiences of electronic adherence assessment in paediatric problematic severe asthma. J Child Health Care 2018;22:238–50. 10.1177/1367493517753082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Waite-Jones JM, Majeed-Ariss R, Smith J, et al. Young people's, parents', and professionals' views on required components of mobile Apps to support self-management of juvenile arthritis: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e25. 10.2196/mhealth.9179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Donzelli S, Zaina F, Martinez G, et al. Adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis and their parents have a positive attitude towards the Thermobrace monitor: results from a survey. Scoliosis Spinal Disord 2017;12:12. 10.1186/s13013-017-0119-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maurice-Stam H, Scholten L, de Gee EA, et al. Feasibility of an online cognitive behavioral-based group intervention for adolescents treated for cancer: a pilot study. J Psychosoc Oncol 2014;32:310–21. 10.1080/07347332.2014.897290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thabrew H, Stasiak K, Garcia-Hoyos V, et al. Game for health: how eHealth approaches might address the psychological needs of children and young people with long-term physical conditions. J Paediatr Child Health 2016;52:1012–8. 10.1111/jpc.13271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dulli L, Ridgeway K, Packer C, et al. An online support group intervention for adolescents living with HIV in Nigeria: a pre-post test study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2018;4:e12397. 10.2196/12397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Domínguez M, Sapiña L. "Others Like Me". An Approach to the Use of the Internet and Social Networks in Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer. J Cancer Educ 2017;32:885–91. 10.1007/s13187-016-1055-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holmberg C, Berg C, Dahlgren J, et al. Health literacy in a complex digital media landscape: pediatric obesity patients' experiences with online weight, food, and health information. Health Informatics J 2019;25:1343–57. 10.1177/1460458218759699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nordfeldt S, Angarne-Lindberg T, Nordwall M, et al. As facts and Chats go online, what is important for adolescents with type 1 diabetes? PLoS One 2013;8:e67659. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Britto MT, Munafo JK, Schoettker PJ, et al. Pilot and feasibility test of adolescent-controlled text messaging reminders. Clin Pediatr 2012;51:114–21. 10.1177/0009922811412950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carpenter DM, Geryk LL, Sage A, et al. Exploring the theoretical pathways through which asthma APP features can promote adolescent self-management. Transl Behav Med 2016;6:509–18. 10.1007/s13142-016-0402-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mulvaney SA, Ho Y-X, Cala CM, et al. Assessing adolescent asthma symptoms and adherence using mobile phones. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e141. 10.2196/jmir.2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ramsey RR, Carmody JK, Holbein CE, et al. Examination of the uses, needs, and preferences for health technology use in adolescents with asthma. J Asthma 2019;56:964–72. 10.1080/02770903.2018.1514048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Raval MV, Taylor N, Piper K, et al. Pediatric patient and caregiver preferences in the development of a mobile health application for management of surgical colorectal conditions. J Med Syst 2017;41:105. 10.1007/s10916-017-0750-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roberts CA, Geryk LL, Sage AJ, et al. Adolescent, caregiver, and Friend preferences for integrating social support and communication features into an asthma self-management APP. J Asthma 2016;53:948–54. 10.3109/02770903.2016.1171339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schneider T, Baum L, Amy A, et al. I have most of my asthma under control and I know how my asthma acts: users' perceptions of asthma self-management mobile APP tailored for adolescents. Health Informatics J 1882;201914604582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vaala SE, Lee JM, Hood KK, et al. Sharing and helping: predictors of adolescents' willingness to share diabetes personal health information with Peers. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018;25:135–41. 10.1093/jamia/ocx051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van Rensburg SH, Klingensmith K, McLaughlin P, et al. Patient-Provider communication over social media: perspectives of adolescents with psychiatric illness. Health Expect 2016;19:112–20. 10.1111/hex.12334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Woolford SJ, Esperanza Menchaca ADM, Sami A, et al. Let's face it: patient and parent perspectives on incorporating a Facebook group into a multidisciplinary weight management program. Child Obes 2013;9:305–10. 10.1089/chi.2013.0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yi-Frazier JP, Cochrane K, Mitrovich C, et al. Using Instagram as a modified application of Photovoice for Storytelling and sharing in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1372–82. 10.1177/1049732315583282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bevan Jones R, Thapar A, Rice F, et al. A web-based psychoeducational intervention for adolescent depression: design and development of MoodHwb. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5:e13. 10.2196/mental.8894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Devine KA, Viola AS, Coups EJ, et al. Digital health interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2018;2:1–15. 10.1200/CCI.17.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coyne I. Research with children and young people: the issue of parental (proxy) consent. Children & Society 2010;24:227–37. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Virella Pérez YI, Medlow S, Ho J, et al. Mobile and web-based Apps that support self-management and transition in young people with chronic illness: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e13579. 10.2196/13579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ridgers ND, Timperio A, Brown H, et al. Wearable activity Tracker use among Australian adolescents: usability and acceptability study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e86. 10.2196/mhealth.9199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sonderegger A, Sauer J. The influence of design aesthetics in usability testing: effects on user performance and perceived usability. Appl Ergon 2010;41:403–10. 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sheehan B, Lee Y, Rodriguez M, et al. A comparison of usability factors of four mobile devices for accessing healthcare information by adolescents. Appl Clin Inform 2012;3:356–66. 10.4338/ACI-2012-06-RA-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Britto MT, Rohan JM, Dodds CM, et al. A randomized trial of User-Controlled text messaging to improve asthma outcomes: a pilot study. Clin Pediatr 2017;56:1336–44. 10.1177/0009922816684857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Carmody JK, Denson LA, Hommel KA. Content and usability evaluation of medication adherence mobile applications for use in pediatrics. J Pediatr Psychol 2019;44:333–42. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Farooqui N, Phillips G, Barrett C, et al. Acceptability of an interactive asthma management mobile health application for children and adolescents. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;114:527–9. 10.1016/j.anai.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tran BX, Zhang MW, Le HT, et al. What drives young Vietnamese to use mobile health innovations? implications for health communication and behavioral interventions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e194. 10.2196/mhealth.6490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Balli F. Developing digital games to address airway clearance therapy in children with cystic fibrosis: participatory design process. JMIR Serious Games 2018;6:e18. 10.2196/games.8964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bonini M, Usmani OS. Novel methods for device and adherence monitoring in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2018;24:63–9. 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. O'Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, et al. A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress Anxiety 2009;26:65–72. 10.1002/da.20507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Goyal S, Nunn CA, Rotondi M, et al. A mobile APP for the self-management of type 1 diabetes among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e82. 10.2196/mhealth.7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e86. 10.2196/jmir.2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kenny R, Dooley B, Fitzgerald A. Developing mental health mobile apps: exploring adolescents' perspectives. Health Informatics J 2016;22:265–75. 10.1177/1460458214555041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Armoiry X, Sturt J, Phelps EE, et al. Digital clinical communication for families and caregivers of children or young people with short- or long-term conditions: rapid review. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e5. 10.2196/jmir.7999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Park E, Kwon M. Health-Related Internet use by children and adolescents: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e120. 10.2196/jmir.7731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Garrido S, Cheers D, Boydell K, et al. Young people's response to six smartphone Apps for anxiety and depression: focus group study. JMIR Ment Health 2019;6:e14385. 10.2196/14385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shah J, Das P, Muthiah N, et al. New age technology and social media: adolescent psychosocial implications and the need for protective measures. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019;31:148–56. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E. Sexual health information seeking online among Runaway and homeless youth. J Soc Social Work Res 2011;2:89–103. 10.5243/jsswr.2011.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Selkie EM, Benson M, Moreno M. Adolescents' views regarding uses of social networking websites and text messaging for adolescent sexual health education. Am J Health Educ 2011;42:205–12. 10.1080/19325037.2011.10599189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Huckvale K, Prieto JT, Tilney M, et al. Unaddressed privacy risks in accredited health and wellness apps: a cross-sectional systematic assessment. BMC Med 2015;13:214. 10.1186/s12916-015-0444-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Balbir SB, Ravinder B, Jo-Pei T. Smart phone activity: risk-taking behaviours and perceptions on data security among young people in England. International Journal of Social and Organizational Dynamics in IT 2013;3:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nikolaou CK, Tay Z, Leu J, et al. Young people's attitudes and motivations toward social media and mobile Apps for weight control: mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e11205. 10.2196/11205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, et al. Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems - a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017;58:474–503. 10.1111/jcpp.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fergie G, Hunt K, Hilton S. What young people want from health-related online resources: a focus group study. J Youth Stud 2013;16:579–96. 10.1080/13676261.2012.744811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Roddis JK, Holloway I, Bond C, et al. Living with a long-term condition: understanding well-being for individuals with thrombophilia or asthma. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2016;11:31530. 10.3402/qhw.v11.31530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

archdischild-2020-319103supp001.pdf (270.2KB, pdf)

archdischild-2020-319103supp002.pdf (254.5KB, pdf)